Borussia Dortmund’s season has seemingly been a tale of two separate halves, and not in the traditional sense of the Bundesliga pausing for its winter break. At the beginning of their 19/20 Bundesliga season, Dortmund was primarily lining up in formations that included a back four, typically using a 4-2-3-1. While they saw some initial success in the early part of the season, by the time November came around, the team was sputtering. Lucien Favre, Dortmund’s manager, was under immense pressure, with rumours swirling that he would lose his position if his team failed to get a result against Barcelona on the 27th of November. While Dortmund ended up losing the match 3-1, cooler heads prevailed, and Favre was still in charge for that weekend’s matchup against Hertha BSC, where he unveiled a back three for the first time. Dortmund defeated Hertha by the score of 2-1, keeping Favre in charge. More important, the use of the back three catalysed their season, getting them back to second place, four points off of Bayern before the season was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This tactical analysis will provide a scout report on how Borussia Dortmund’s switch to a back three catapulted the team up the Bundesliga table. The analysis of Lucien Favre’s tactics will provide clarity on their success, specifically winning 31 out of a possible 39 points since their switch to a back three.

Dortmund’s downward trend with a back four

Towards the beginning of their season, Borussia Dortmund primarily began each match in a 4-2-3-1, changing shape throughout matches depending on personnel changes or match-specific demands.

In the month of September, they lined up in a 4-2-3-1 88% of the time, with Roman Bürki in goal. In front of Bürki was the back four, with Raphaël Guerreiro as the left-back, Mats Hummels and Manuel Akanji as the centre-back pairing, with Achraf Hakimi playing as the right-back. Thomas Delaney and Axel Witsel paired together as holding midfielders, with Thorgan Hazard on the left wing, Marco Reus in the centre, and Jadon Sancho on the right wing. In front of those three was Mario Götze.

This lineup was incredibly successful, creating 12.54 xG and allowing 3.21 xG. They ended up scoring 13 goals and allowing four, albeit with a friendly against FC Energie Cottbus of the Regionalliga Nordost, where they scored five and conceded zero. As they progressed into October, Dortmund continued to use a back four, primarily using the same formation as seen above, the only difference being the Hakimi moved to the left wing position for Hazard, with Łukasz Piszczek filling in as the right-back for Hakimi. While using this 4-2-3-1 39% of the time, they also utilised a 4-4-2 and a 4-3-3 with most of the same players, with Julian Brandt and Julian Wiegl getting playing time as well. In October, Dortmund only managed to create 5.86 xG while allowing 6.97 xG. The final two games with the back four saw them allow seven goals and only score three, losing 4-0 to rivals Bayern Munich and drawing 3-3 with bottom-dweller SC Paderborn.

One of the big problems that became apparent against both Bayern and Paderborn was how much Dortmund struggled in their build-up play. Many times, when they tried to progress the ball forward, their midfielders would be on the same horizontal line, offering no depth to their team.

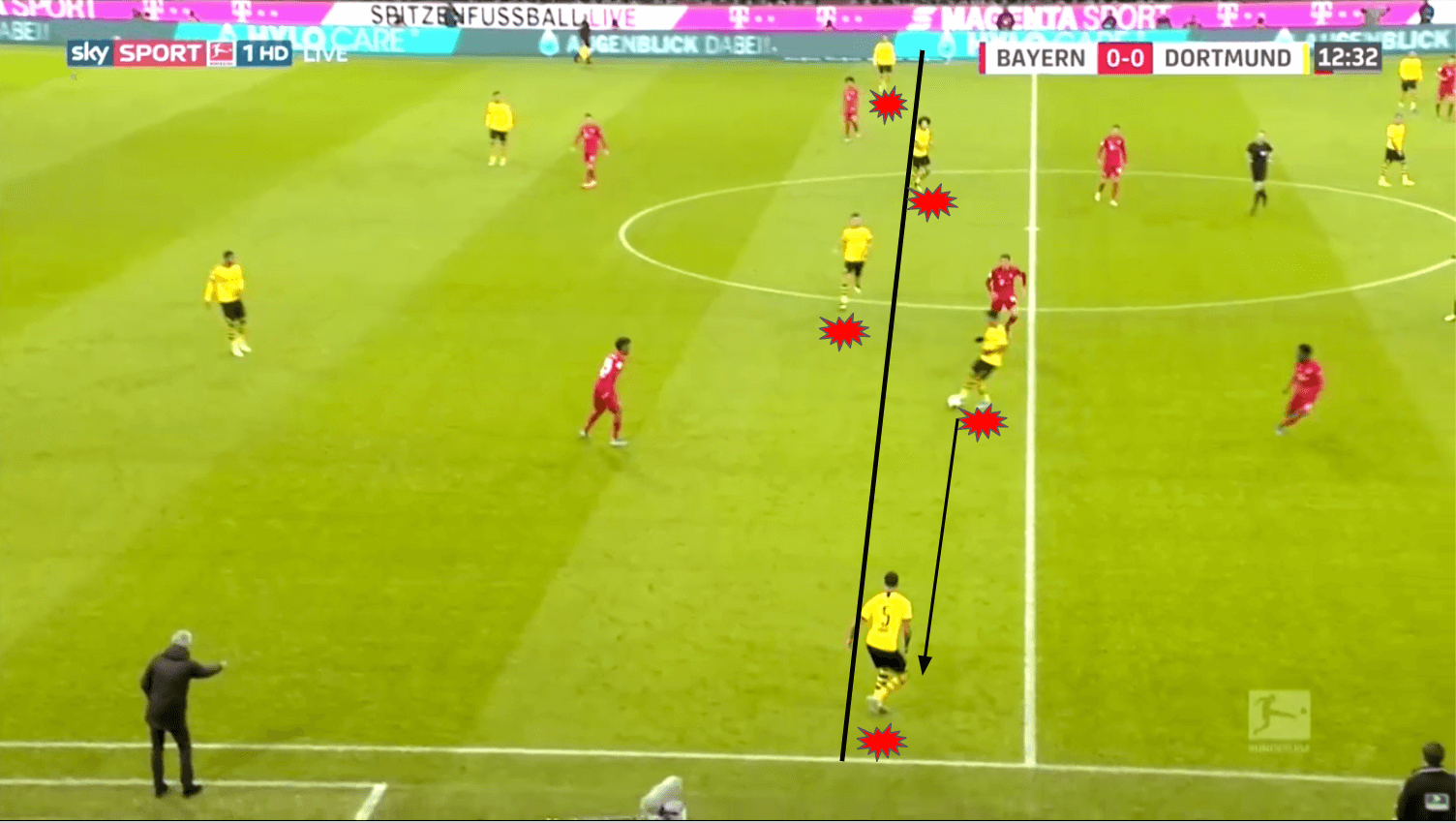

Here, against Bayern Munich, Jadon Sancho dropped down to receive a pass from Manuel Akanji. He played a one-touch pass to Hakimi, who was looking to go forward. Sancho’s movement down has been counterproductive because Dortmund now had five players on the same horizontal line, which became easy to defend and also eliminated options to progress the ball forward. In this very instance, Hakimi attempted to go forward but was unable to because Julian Brandt was late getting over to the space that Sancho should have been occupying. The other problem Sancho created was the fact that he was now operating in Julian Weigl’s space. In the image, Sancho and Weigl are essentially playing the same role, which means that Dortmund have effectively gone down to ten men, putting them at an obvious disadvantage.

This happened consistently with Dortmund, particularly on the wings. One example comes from the match against Bayern Munich.

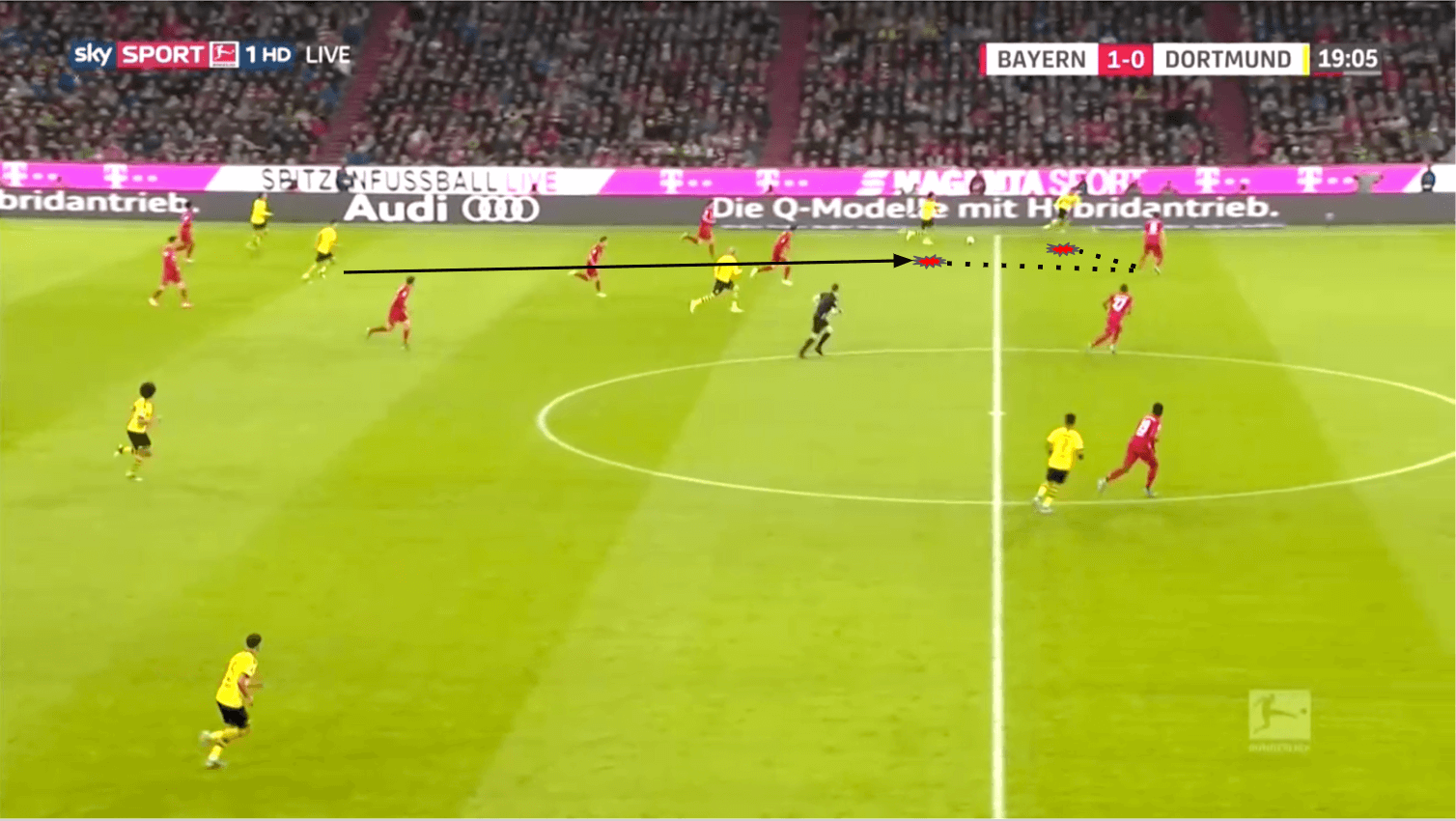

Here, Weigl had just played the ball to Mario Götze’s feet. Götze had just checked into that space from the centre of the pitch; the problem is that Thorgan Hazard was already there. This means that Javi Martínez can effectively mark two men at the same time, as they are too close to one another. If this were a one-off instance, it wouldn’t be a problem; however, Dortmund did this consistently against Bayern and Paderborn, their final two matches with four defenders on the pitch.

Another problem with Dortmund using a back four comes with distribution in the build-up play. When using the back four, teams like Paderborn can set up in a 4-4-2 defensive block, and if their forwards can use their body shape properly, they are able to eliminate four players from the match.

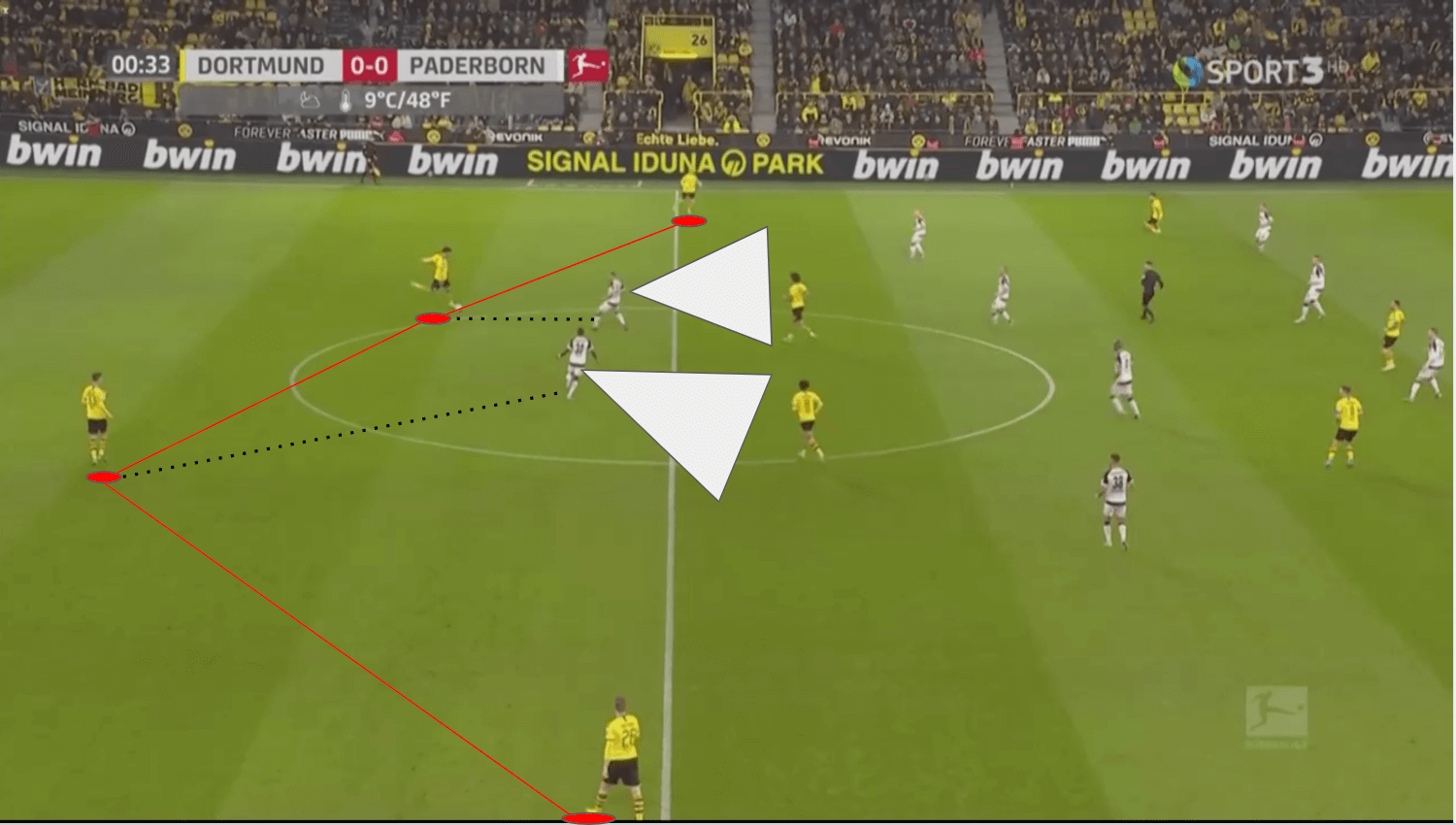

Against Paderborn, the 4-4-2 defensive block was used effectively. As shown in the image, Dortmund were in their back four, with Weigl and Hummels as the centre-backs. When in possession, as Hummels was above, Paderborn’s forwards eliminated Hummels and Weigl as passing options by providing pressure when one of them was in possession. Simultaneously, they used their cover shadow to eliminate Witsel and Mahmoud Dahoud, who were Dortmund’s holding midfielders for this match. This meant that Dortmund would be forced to progress up the pitch with their outside backs playing a larger role. This caused problems because defences can shift over accordingly when the left-back or right-back received a pass. The outside-back also had to deal with the fact that they were closer to the touch line, which essentially eliminated half of their options going forward because of their positioning. While a player like Weigl in the image has 360 degrees of passing options, Łukasz Piszczek, who played as the right-back in the match, had at most 180 degrees of passing options.

A back three’s influence on player positioning

Favre clearly recognised the information above and opted to make a change, as it became clear that his job depended on it. His change to a back three, specifically a 3-4-3, accompanied by what seemed to be stricter expectations around positioning allowed for Dortmund to see more success in their style of play, almost immediately.

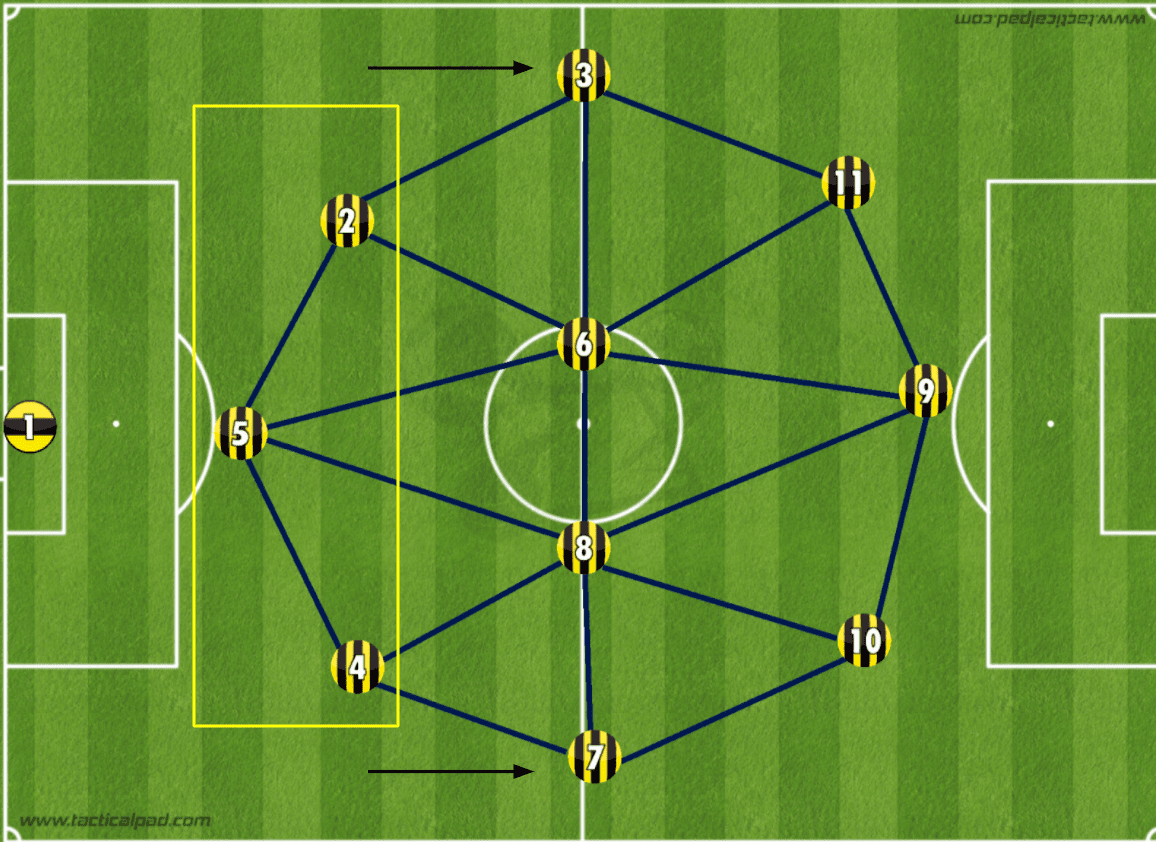

Compared to having four defenders, a back three can help control the midfield and solidify build-up play. One way it does this is with the positioning of the three centre backs. Compared to the left-back or right-back and their limited ability to distribute possession, the left-centre-back (number 2 in the image) or right-centre-back (number 4 in the image) are positioned more centrally. This allows them a greater range of passing, with more angles and opportunity for them to progress the ball forward. Instead of having one or two passing options like an outside-back would when defended, the centre-backs have two or three options. This makes their play less predictable, which is an offensive advantage.

Another advantage that Dortmund looked to take advantage of with the back three is the ability to get their pacier players higher up the pitch, making them more of a threat moving forward. The wingers in the midfield (numbers 3 and 7 in the image) are able to position themselves higher because they have more coverage from their corresponding centre-backs. In Dortmund’s case, Raphaël Guerreiro and Achraf Hakimi are some of their faster players. With a back four, they functioned primarily as outside-backs, which gave them less license to go forward, and if they were attempting to go forward, they would often do so from farther away, as they worked to stay connected with their centre-backs. Both Guerreiro and Hakimi have benefited from this positioning: prior to the change, Guerreiro had two goals and zero assists in the Bundesliga while Hakimi had two goals and three assists. Since then, Guerreiro has registered three goals and three assists, while Hakimi has one goal and seven assists.

How the back three impacted Dortmund

The change made by Favre began paying off almost immediately. Their first match using three in the back saw Dortmund come out in a 3-4-3, with Zagadou, Hummels, and Akanji in the back three, with Zagadou on the left, Hummels in the centre, and Akanji on the right.

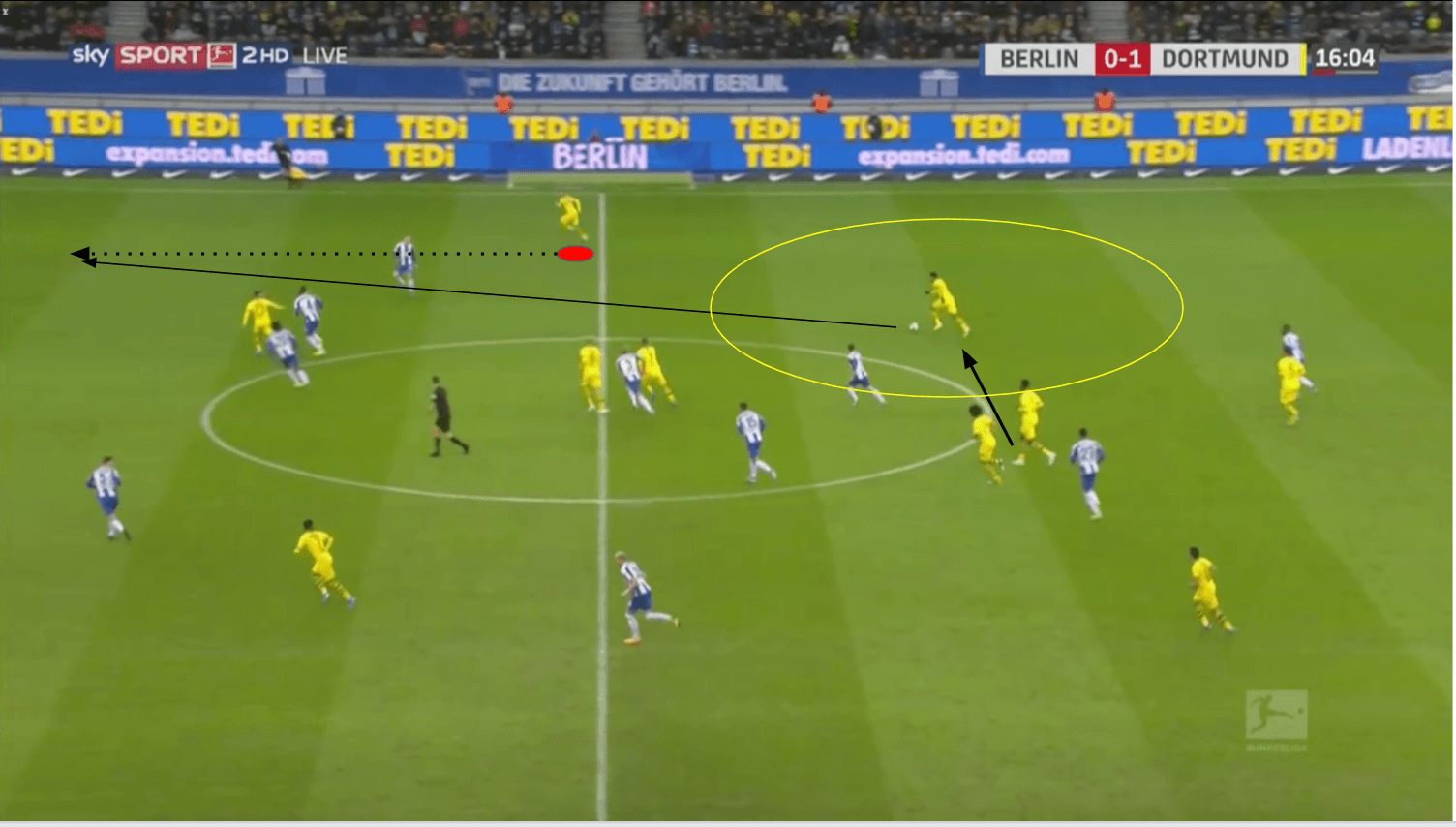

Zagadou was able to progress the ball forward before he played a ball to Akanji, who was wide open because he was playing in a back three. Hertha’s two forwards were outnumbered against Dortmund’s back three, which created a numerical superiority for Dortmund. Hakimi, who is incredibly quick, was higher up the pitch, so his run was shorter, allowing him to create more space between him and his defender. Hakimi took advantage of this qualitative superiority, and before he could be closed down, he crossed the ball to Hazard, who finished coolly.

Another benefit of the use of the back three is how teams respond. Hertha did not seem prepared for a change in formation, which makes sense considering Dortmund had used four defenders since August. Dortmund were able to use their formation and its very basic shape to play through Hertha.

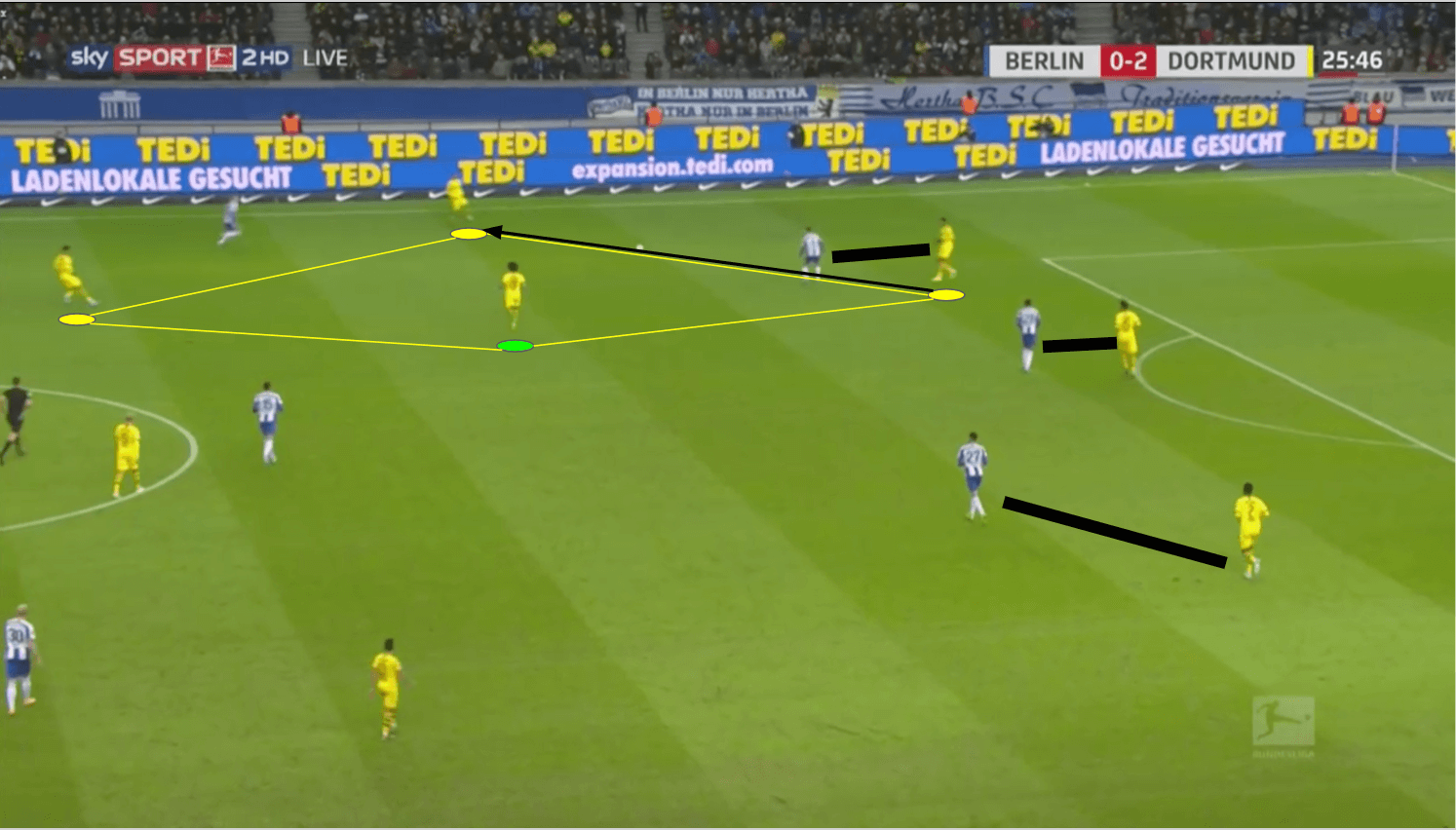

Here, Hertha’s forwards and an additional midfielder opt for a man-to-man press on Dortmund’s back three. The first thing that this created was a lot of space in the centre of the pitch. Witsel, who is the green circle in the diamond, has no one around him because Hertha had sent men forward to press. Hakimi played a one-touch pass to him, and Witsel was able to turn and face the majority of the field because of all the space he had. Similarly, Dortmund also took advantage of the 3-4-3’s shape with the diamonds that can be naturally created if players are positioned properly. In the image, Sancho dropped down to be a potential option for either Hakimi or Witsel. These shapes occur naturally if players are able to maintain discipline in terms of their positioning.

Because Dortmund now have a back three, they are also able to create numerical advantages going forward, as they have freed one player from his defensive duties due to the nature of the formation. One example of the advantage they have created is in the midfield, specifically against RB Leipzig in December.

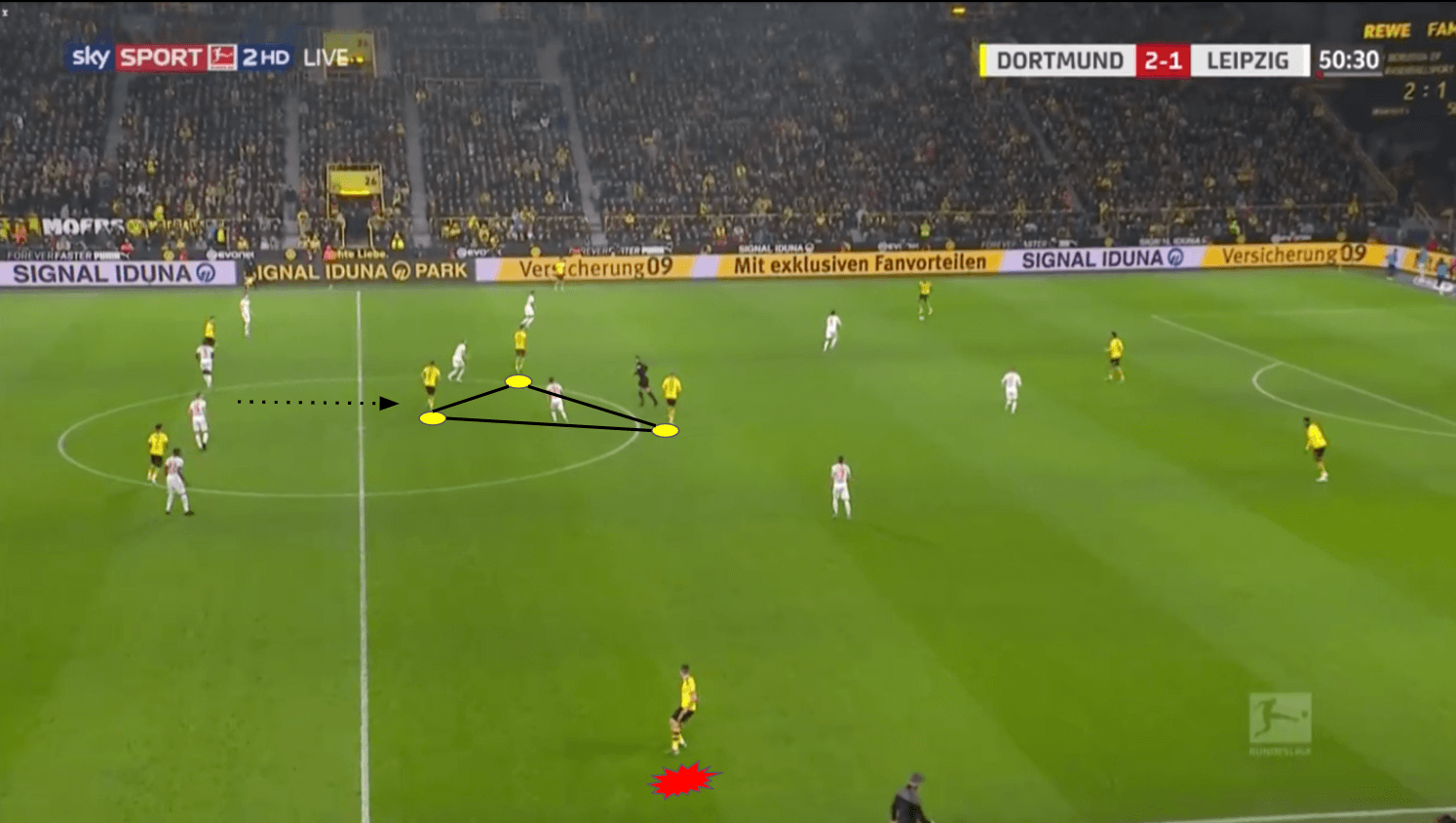

Reus, who was in the centre of the three forwards in the match, dropped into the midfield, where he created a numerical advantage alongside Brandt and Weigl. Dortmund now has three players in that space compared to Leipzig’s two. If they were able to receive the ball and quickly pass between them, they would have the opportunity to switch the field of play to Guerreiro, who is at the bottom of the image, marked with red. That would allow him to receive the ball with plenty of time and space, which would allow him to use his pace to create a dangerous play. Dortmund are able to do this on both sides of the pitch as Hakimi also possesses a lot of speed.

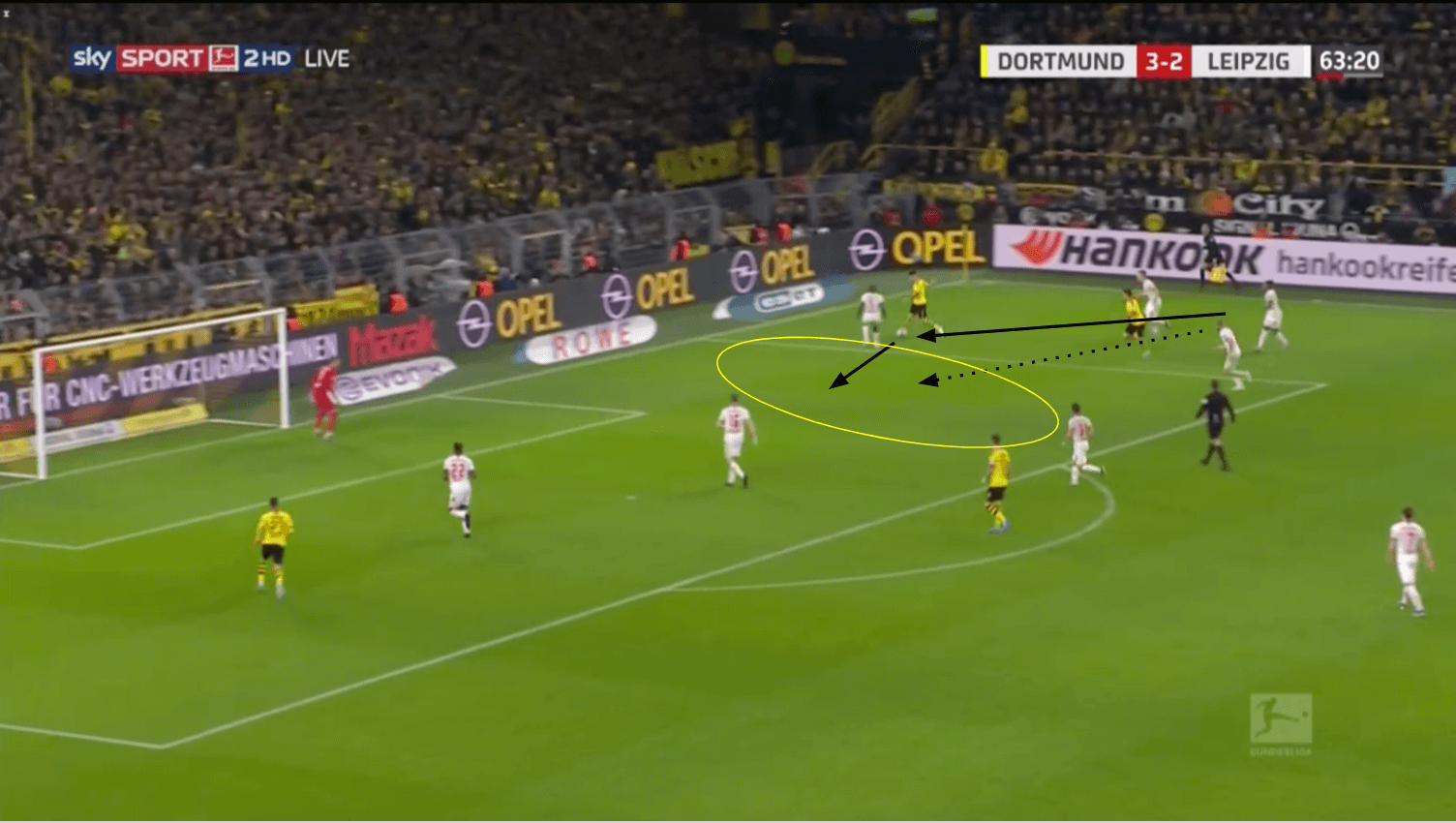

They took advantage of this later in the match when Hakimi received a ball in time and space and played a wall pass with Sancho, getting himself into a dangerous position outside of the penalty box.

Despite there being four defenders, Hakimi and Sancho were able to pass through Leipzig’s defence. As Sancho made a run towards the end-line, Hakimi placed a perfectly weighted ball to him and then made his own run to the space inside the area that Dayot Upamecano had just vacated. Sancho played him in with his first touch, and Hakimi was in on goal just outside the six yard box with a defender behind him. While his shot was deflected wide, Dortmund’s ability to create opportunities from the wing continues to be a problem for teams. Dortmund’s signing or Erling Haaland, a potent finisher, makes their wing play even more dangerous for their opponents. In fact, seven of Haaland’s nine goals have come from Dortmund’s wings. While Haaland earned much of the headlines in the January transfer window, Dortmund’s other addition has made an even larger impact.

Can replaces Brandt in midfield

While the switch to the back three has brought Dortmund more success this season, particularly allowing them to attack more efficiently and increase the amount of games they were winning, they were still struggling to prevent teams from scoring. Prior to Emre Can’s arrival at the end of January, Dortmund had allowed 11 goals in seven games. In the seven games since Can arrived, they’ve only allowed seven goals, with four of those coming in Can’s first game against Bayer Leverkusen — a match in which he was not completely comfortable with his role. Emre Can was essentially brought in to replace Julian Brandt, who had been playing as a central midfielder next to Witsel. Now that Can has replaced Brandt, and their defence has tightened up accordingly.

When looking at the statistics over these sets of seven games, it becomes clear that Brandt was progressing forward up the pitch more consistently; as a result, he logged 1.29 xG and .98 xA (assists). Conversely, in a similar amount of minutes, Can has only recorded .19 goals and .09 xA. This suggests that Can does not advance up the pitch in as much of a playmaking role, which allows him to provide more cover for the back line with his positioning. Additionally, Can (135) and Brandt (123) have engaged in a similar amount of defensive duels; however, Can’s win percentage in those duels is 13% higher, proving him to be more defensively efficient.

What also makes Can stand out are his defensive recoveries, particularly in the opponent’s half. Can has 57 recoveries compared to Brandt’s 34 recoveries. This 67% increase makes Can seem even more valuable to Dortmund’s defensive efforts. What’s more impressive is that 31 of Can’s recoveries have happened in his opponents half as compared to Brandt’s 17. That means Can is an improvement on Brandt on regaining possession in the opponent’s half by 82%. One final statistic to note: Emre Can is 7% more efficient than Brandt with his backwards passes (99% compared to 92%). While back passes aren’t often seen as critical to a football team’s success, it does mean that Can helps Dortmund keep the ball in their possession more frequently than Brandt did.

Conclusion

Favre’s change to a back three allowed Borussia Dortmund to become more efficient with their attack and less fragile in defence. As Dortmund grew into their new 3-4-3, their effective wing play became a large part of their initial success. This wing play continued to thrive when Haaland joined the squad, making them even more offensively potent. The club did well to replace Brandt, a defensive liability in their current structure, with Can. Despite their initial struggles in the Bundesliga season, Favre’s change to a back three moved them up the Bundesliga table from sixth place to second. If the Bundesliga returns to play, Dortmund, with more than half their remaining matches against teams in the bottom half of the table, have a strong chance to close the gap on Bayern Munich.

Comments