After parting ways with AFC Bournemouth, Eddie Howe decided to have one season off regardless of which club made an offer. Although he was linked with jobs at teams such as Celtic, Arsenal, Everton, and Tottenham Hotspur, nothing went on to become realistic until he took charge of Newcastle United. Despite being the successor of Steve Bruce, and with more resources in hands, the Magpies are still in a difficult position as they are fighting for a Premier League place next season.

There were many reports about how Howe educated himself, reflected on his past, and learnt lessons from the likes of Diego Simeone and Andoni Iraola to upgrade his coaching philosophy and management. So, do we see any differences between Howe’s Newcastle and Bournemouth?

This analysis will compare the tactics of these two sides to examine whether any new tactical elements have been added to the Magpies.

Data comparison and analysis

We compared the data of Bournemouth in 2019/20, in which they were relegated from the Premier League and Newcastle under Howe so far, the data are summarized in the table below:

|

|

Howe at Newcastle 2020/21 | Bournemouth 2019/20 |

| xG per 90 | 0.86 | 1.17 |

| Shots per 90 | 9.78 | 9.53 |

| xGA per 90 | 1.88 | 1.81 |

| Shots against per 90 | 14.44 | 13.87 |

| PPDA | 14.86 | 12.54 |

| Average possession | 39.39% |

44.26% |

It was not ideal at all, as Howe’s Newcastle are only better in one department, 9.87 shots against per 90 than Bournemouth 2019/20’s 9.53, while the others are not as good as the Cherries seasons ago. It might be slightly unfair because the Magpies have already encountered Manchester City, Liverpool, Arsenal, and Leicester City in these fixtures, so they might struggle to create and be dominated by the opponents. However, the xG per 90 at 0.86 was something to concern about given that was a huge difference compared to his Bournemouth’s 1.17.

We will apply more data into context with the tactical analysis below.

The clear identity?

Since the early days, Howe had a very clear way of playing football. Intriguingly, his former player did not describe his style as something like “possession-based” or “Barcelona-liked”, but more about the mindset, being forward-thinking, relentless effort, constant improvements, and commitment to the training sessions. The way Howe worked every day and the beliefs he had should also be something the board of management valued, hence, getting him a job at Newcastle.

While reflecting on the last season at Bournemouth, the conclusion was the compromising of identity might be the reason of decline. Howe and his players were more often adjusting their tactics to adapt to the opponents, trying to be more “pragmatic” with a lower block, and create the chances through the offensive transitions. For example, this was how they beat Graham Potter’s Brighton & Hove Albion in 2020 January at the Vitality Stadium.

Particularly, the dynamic occupation of space was not clearly spotted at Howe’s Bournemouth. In the construction phases of the attack, the team played in a 4-1 shape with one holding midfielder only, and the full-backs were staying wider to provide the width, drag the opposition first/second line wider to open spaces in the inside channels.

However, they were also more direct than ever in that season. The long passes proportion of a 2019/20 Bournemouth game was 11.89%, and the figures in this metric was never that high before as we have shown in this table below:

| AFC Bournemouth | Long passes % |

| 2019/20 | 11.89% |

| 2018/19 | 9.99% |

| 2017/18 | 11.33% |

| 2016/17 | 10.58% |

| 2015/16 | 11.64% |

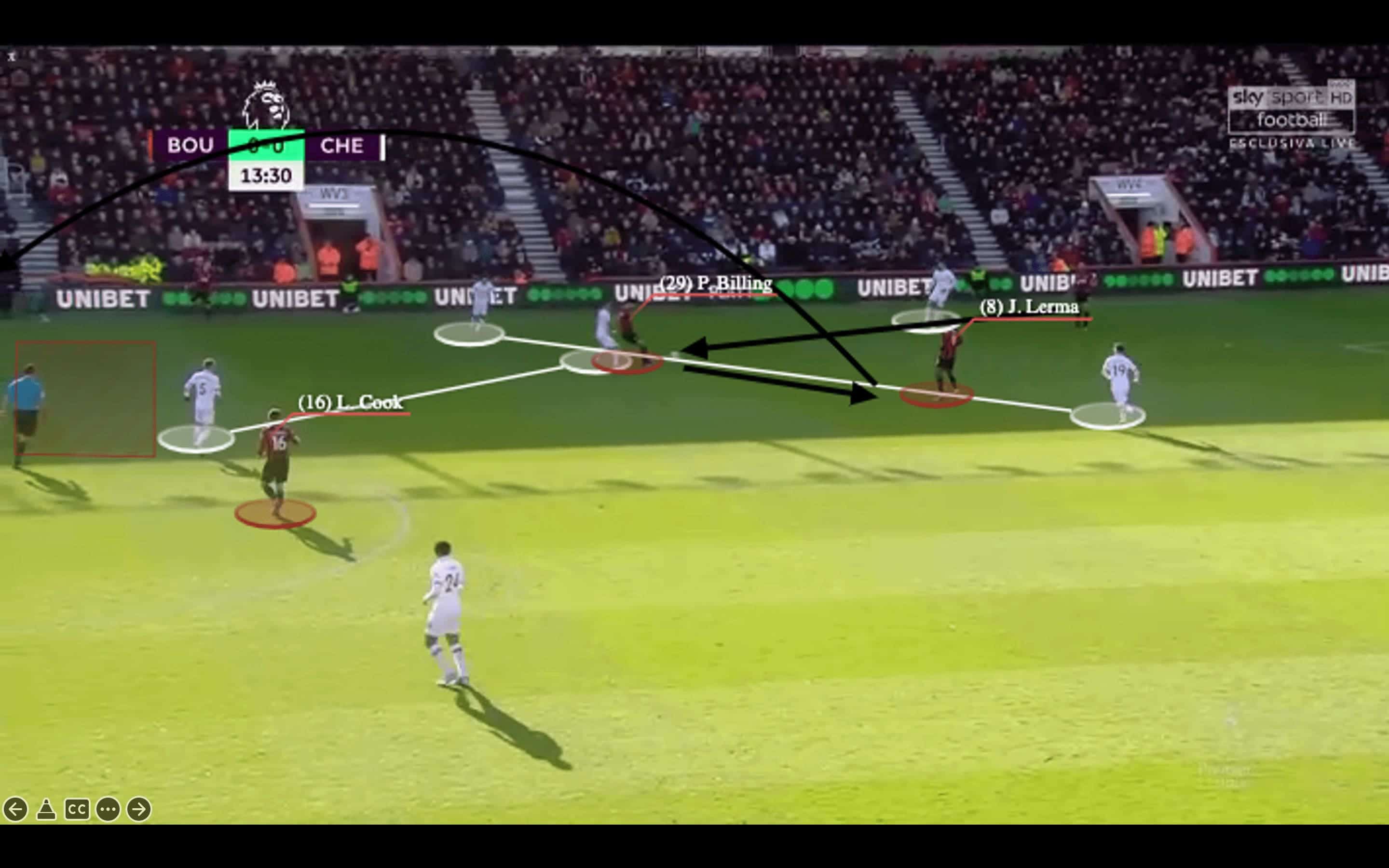

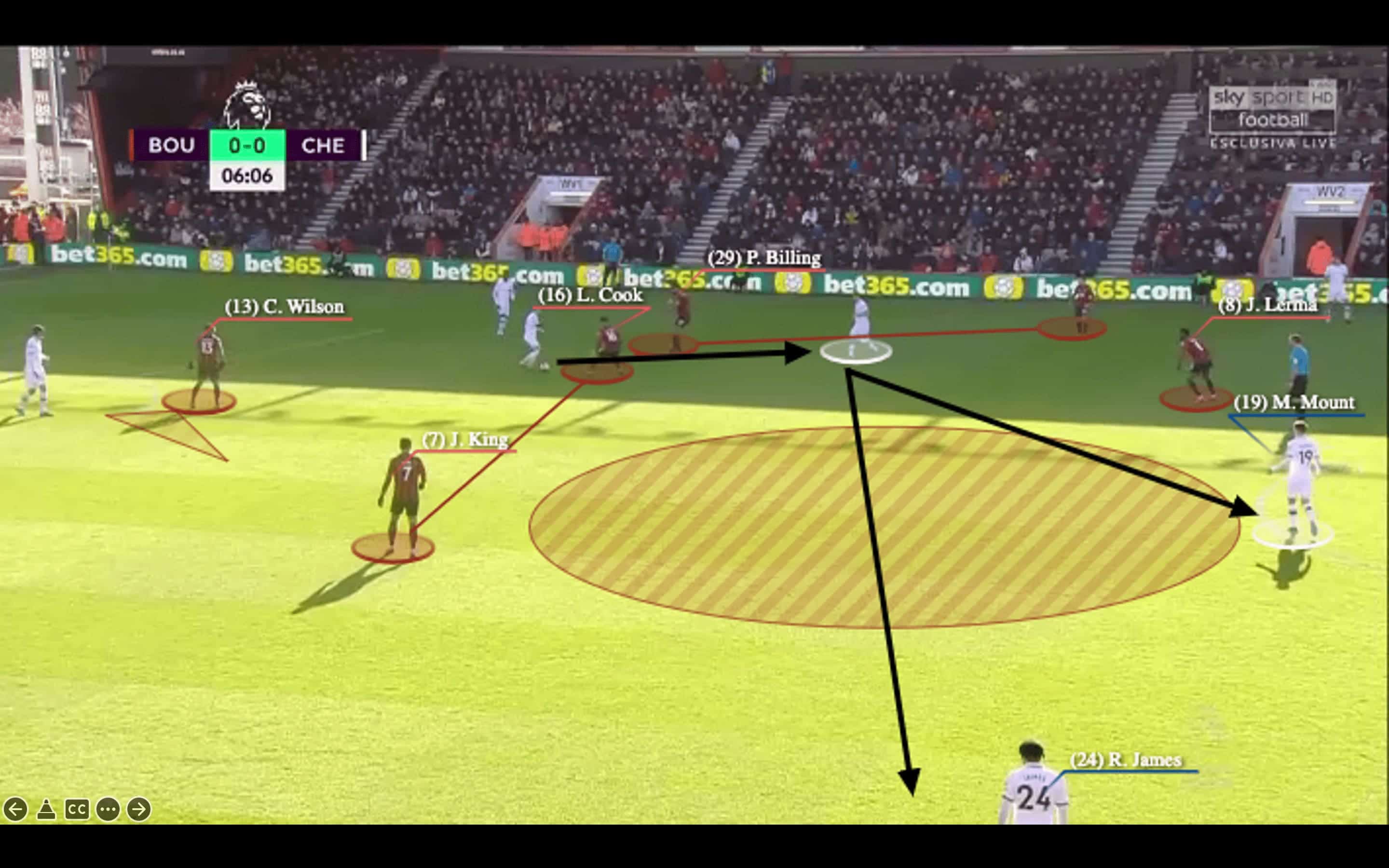

In the above screenshot, Bournemouth’s deep and wide right-back dragged Chelsea’s 5-2-2-1 block into a 5-2-3 shape. They would drop an 8 to present an option in the half-spaces channel, and Phil Billing managed to reach Jefferson Lerma with a vertical third-man play. Also, note how Bournemouth manipulated the Chelsea midfielders, Mateo Kovačić and Jorginho. Spaces were opened behind Jorginho, who also needed to cover Lewis Cook over the course. With Callum Wilson high to pin the last line, the red spaces were favourable to the Cherries attack if they were to play between the lines. But the right-winger was mostly one-minded in to go behind and that long pass from Lerma just gave the back to Chelsea.

How about his Newcastle? The long passes % of Howe’s side is 13.72%, even higher than all Bournemouth seasons. But it was also conceivable given the matches against City and Liverpool pulled the numbers higher. This would be the next development we would expect to see. Against stronger sides, what would Howe do in the future? Frankly, the “pragmatic approach” with more direct, fewer risks in the attacks, did not come with better chance creations, as the xG recorded in these two games were 0.39 and 0.19 only.

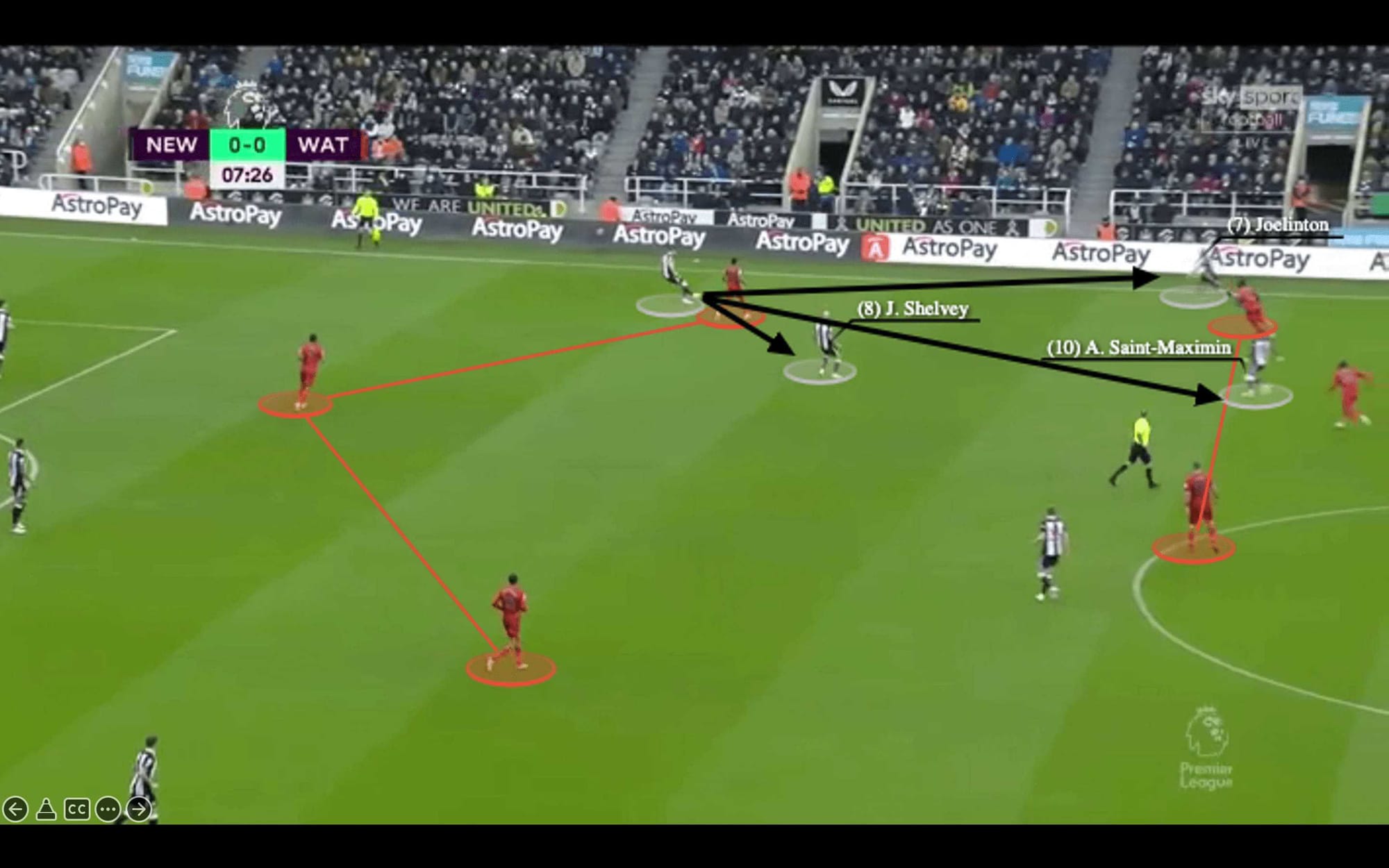

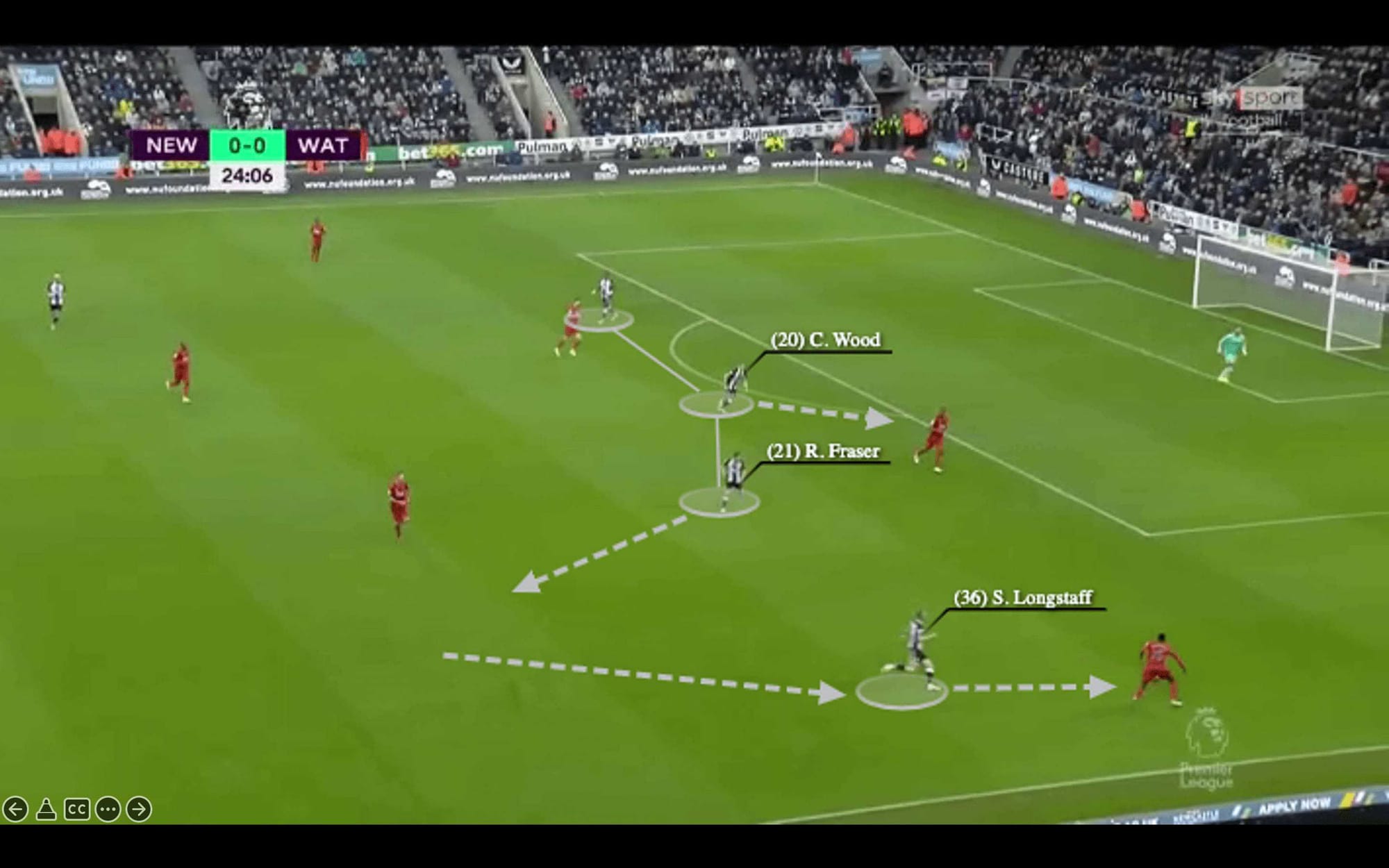

So far, we have spotted a structure to allow the Magpies playing in a more organized manner in the construction phases. They were mostly applying that in games against mid-table teams or the bottom half of the table. In the above situation against Watford, the structure was solid on the left side to generate multiple passing options for the left-back. Joelinton, as the 8, would drift wider to take the marker to the outside channel, so Allan Saint-Maximin could play in the half-spaces. The duo could also move into an alternative but reversed directions to pose questions on the defence – who to follow? The Frenchman winger was the clear strength of Newcastle and the team must give him spaces to play.

Also, the 6, Jonjo Shelvey should present himself as a diagonal passing option in the centre, so he rarely dropped into the first line. This was a position Howe might consider reinforcing because the holding midfielder must be comfortable to receive in spaces. Also, possessing the ability to read the game and handle the complexity of football in all four phases of play. That’s why they are hunting Bruno Guimarães in this window.

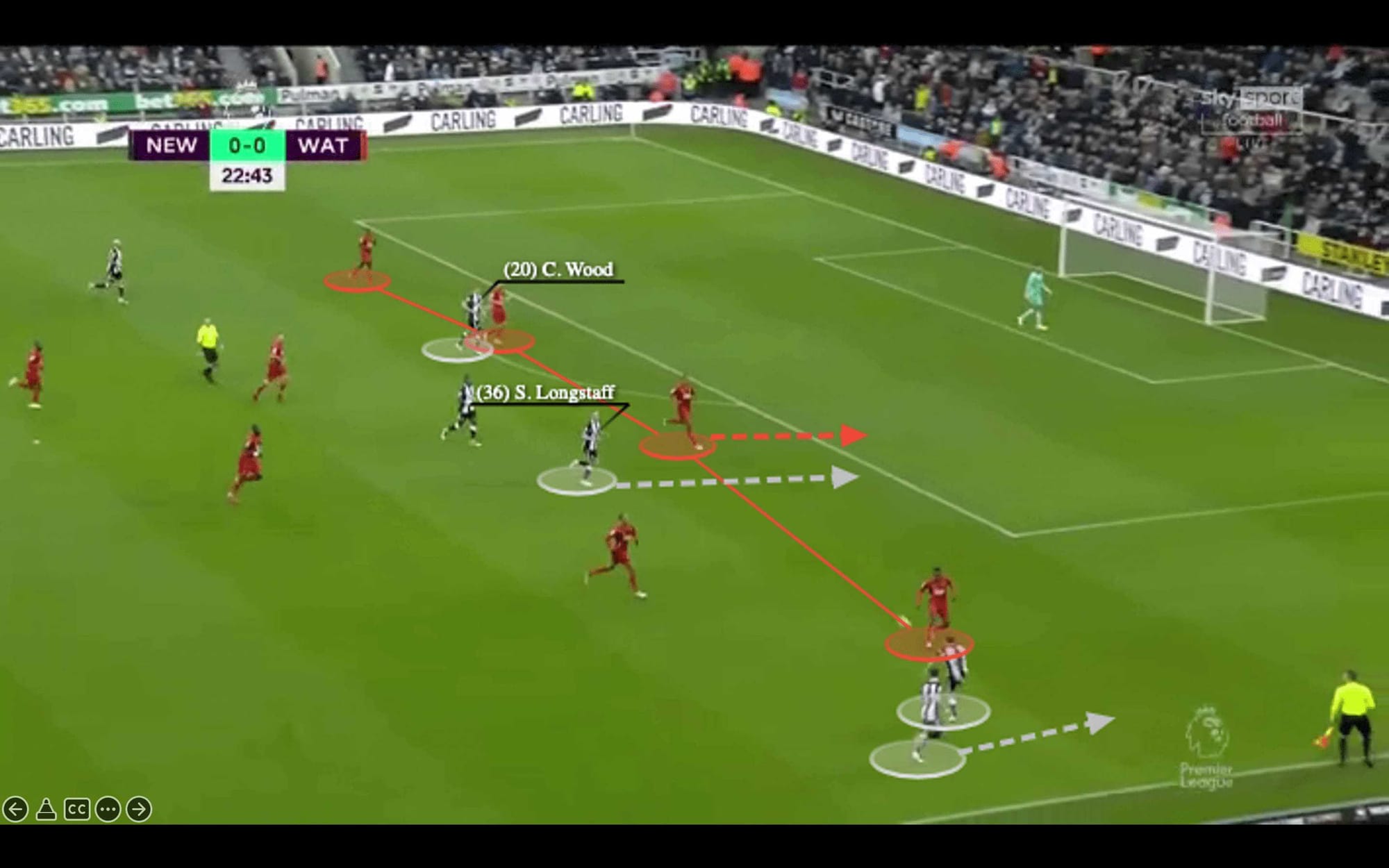

They know the importance of getting Chris Wood, their latest recruitment from Burnley into goal-scoring positions. In terms of an attacking move, Howe improved by involving three, four, or even five players and the way the players interacted were better. For example, in the above move against Watford, there was a structure to create chances in the final third.

When Ryan Fraser had the ball, Kieran Trippier attacked the outside channel to manipulate the body orientation of Watford left-back. So, Fraser had the angle to go inside or release the right-back, the overlapping run was also something Howe carried on since his days at Bournemouth. Meanwhile, Sean Longstaff made a forward run to attack the half-spaces, forcing the centre-back to react, separating Craig Cathcart and Samir. As a result, Wood would have a 1v1 situation against the remaining centre-back, this was where he should show his aerial dominance and chance conversion in the penalty zone.

Pressing and central protection

During Howe’s tenure at Bournemouth, he wanted intensity from his side but the pressing and defensive style of plays were not his trademarks. The xGA per 90 of Bournemouth increased season by season, as we sum up in the below table:

| Bournemouth | xGA per 90 |

| 2015/16 | 1.43 |

| 2016/17 | 1.56 |

| 2017/18 | 1.8 |

| 2018/19 | 1.58 |

| 2019/20 | 1.81 |

There was something going on there and Howe could not solve in long term, which might also be attributed to an injury crisis and struggling to establish a solid partner for Nathan Aké. Three of his last two seasons at the Cherries recorded 1.8 xGA per 90. As a reference, in the same season (2019/20), the xGA per 90 of the other two relegated teams (Watford, Newcastle) were 1.59 and 1.7; last season’s Sheffield United and Fulham’s xGA per 90 were 1.71 and 1.48; only West Bromwich Albion’s 2.1 xG per 90 was higher than those seasons of Bournemouth among the last six relegated Premier League teams. That might be a reason for Howe to review his defensive philosophy by learning from Simeone’s Atlético Madrid.

Particularly, we felt Howe’s Bournemouth had the compactness to defend in a low block, and intensity was also shown in the high press. However, the subject of space was a big issue. They could not stop the oppositions from constructing the attack in the centre, and being dictated by the opponents too often in 2019/20.

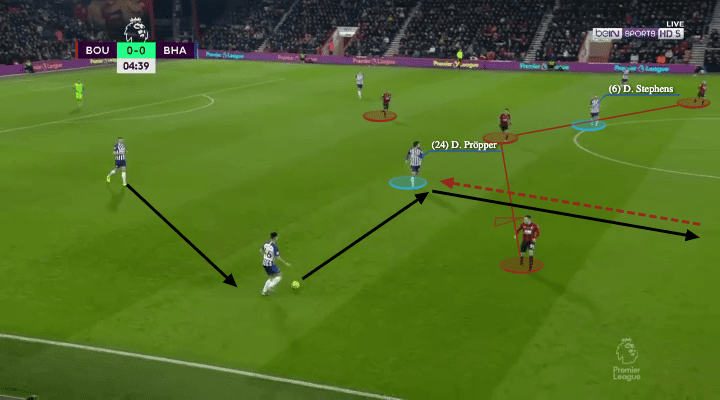

For example, when Howe came with a 4-2-3-1 to handle Brighton’s 4-4-2, they could not cope with the 2-4 build-up shape of Potter’s side because the front players were lacking the awareness to close the centre. Structurally, the 4-2-3-1 only have one 10 (Dominic Solanke) and he could not mark both 6s of the opponents. Here, when Solanke marked Dale Stephens on one side, he could not close Davy Pröpper in the other half-space.

Also, the players were lacking individual defensive behaviours to guide the ball into a designated direction, such as the striker wide did not use his body angle to shadow the 6 behind him, mostly cutting the passing lane between centre-backs; while the winger was not narrowing the space in the centre because he was focusing on the wide defender more often. Here, Fraser had his eyes on the right-back and so he exposed the half-spaces channel for Pröpper to pass the ball forward.

If Bournemouth pressed, the main issue would be the compactness of the shape. Their far side winger rarely tucked inside to protect the midfield spaces, and the 6 (e.g. Lerma) was lacking the intensity to cover the second line, so the opponents could break them easily by using the deep midfielders to draw them out.

Chelsea did that with a 3-2 shape in the build-up. Jorginho and Kovačić were deep to pull L. Cook and Billing out of positions, and Lerma would be struggled to cover the alternative half-spaces because he was usually vertically behind the 8 on the ball side. When the pressing could not close the angle of the passer, the opponents could go into spaces behind the first line and Kovačić was there, the Croatian midfielder could then spread the ball diagonally to Mason Mount or Reece James because Bournemouth’s left-winger (Joshua King) could not close the red spaces.

Hence, the central protection becomes something important for Howe’s Newcastle. They showed some good behaviours and pressed with more attention to close the central spaces. Against the goal-kicks or in the high press, they setup a 4-3-3 defensive structure with a pair of narrow wingers to close the half-spaces channel. This makes sure the centre-backs could not play vertical passes in the centre.

Then, foreseeably the opponents would go wide by playing the ball to full-backs. The follow-up actions were something different from Bournemouth because the 8s would jump out from the centre, the press must carry intensity by sprinting to force the opponents move. The diagonal pressing angle also closed down the passing lane to the centre as well. The above example shows Longstaff pressing Hassane Kamara, while Fraser went back to cover the Watford 8. With Wood also closing the centre-back (Samir), they blocked all access to the centre when Kamara received, this was a successful high press.

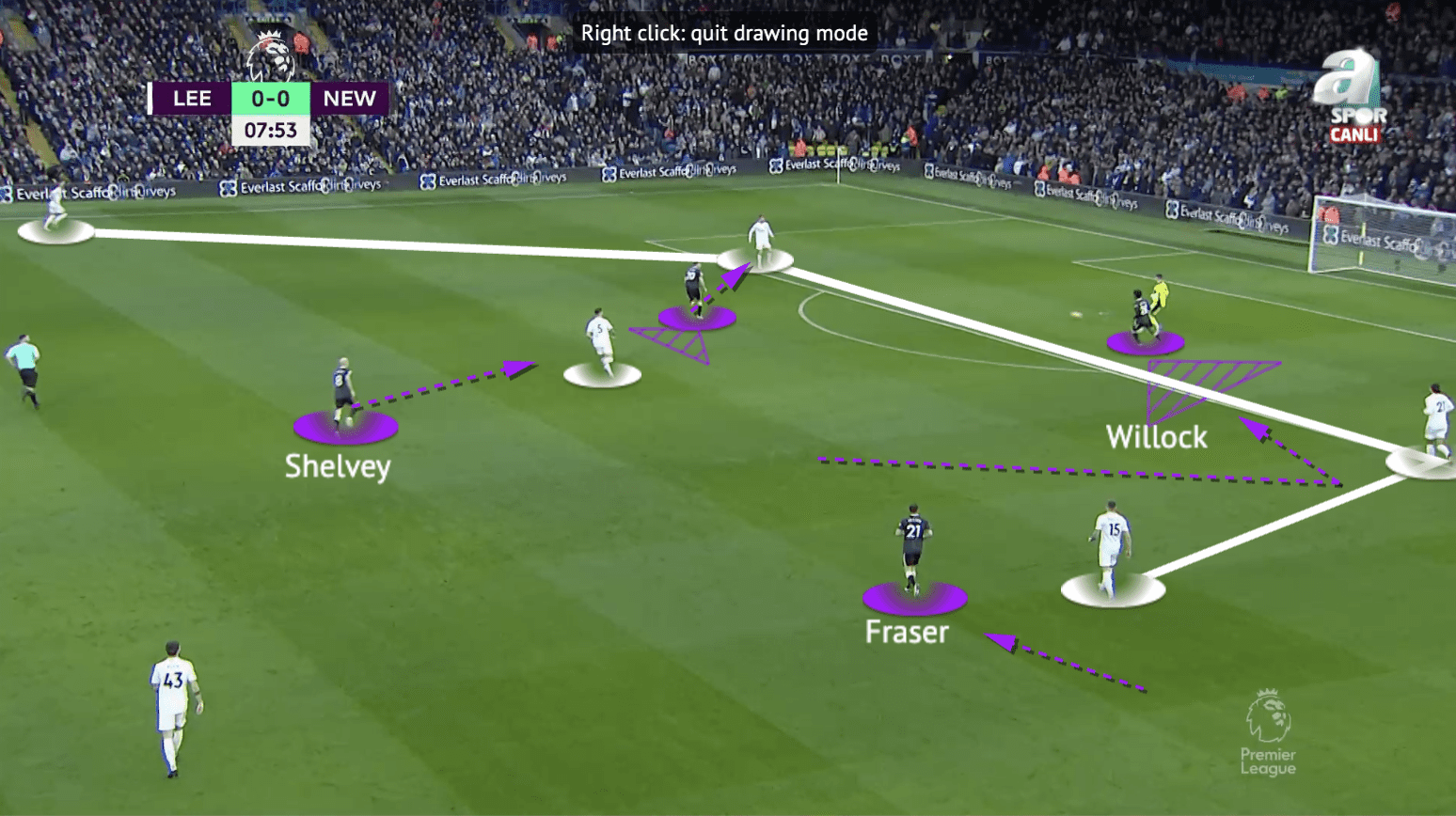

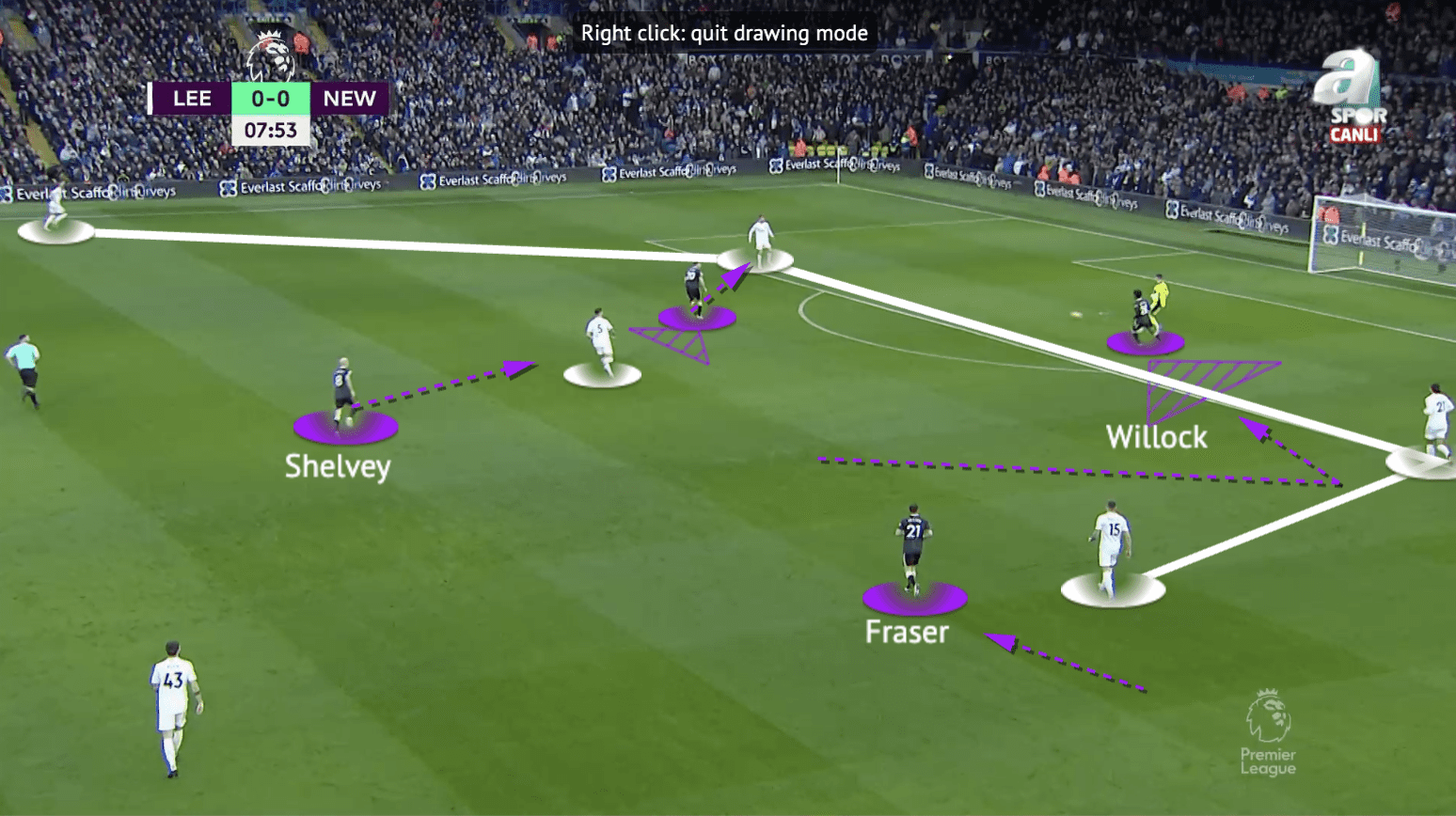

Below was an alternative pressing scene against Leeds United, Newcastle also paid attention to the opposition 6 behind the first line, and the cover of each chain was stronger. When Joe Willock and Wood were pressing the centre-backs, Shelvey came up to close down the Leeds 6, while Fraser went slightly narrower to maintain the compactness of the structure. In the screenshot, four Newcastle players controlled the spaces on the inside and let the opponents play around them, not through or within them.

But the pressing, especially in the midfield, is an aspect the team must improve in the short term. Currently, most of the issues were individual behaviours because the players weren’t trained and instructed to defend that way under the previous manager. Against City, they conceded the João Cancelo goal began from a collapsed press, while the Edinson Cavani equalizer was also attributed to a bad pressing.

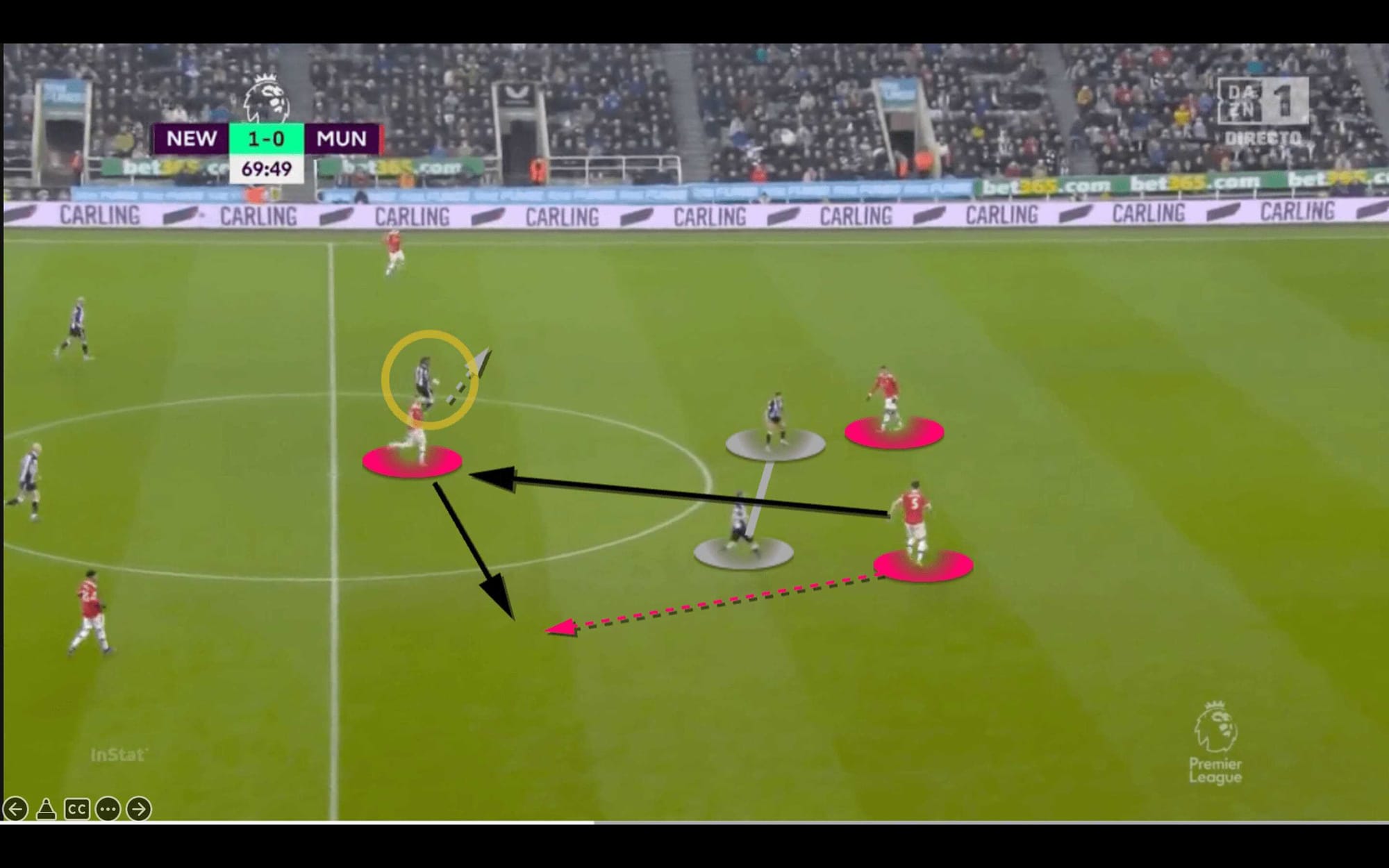

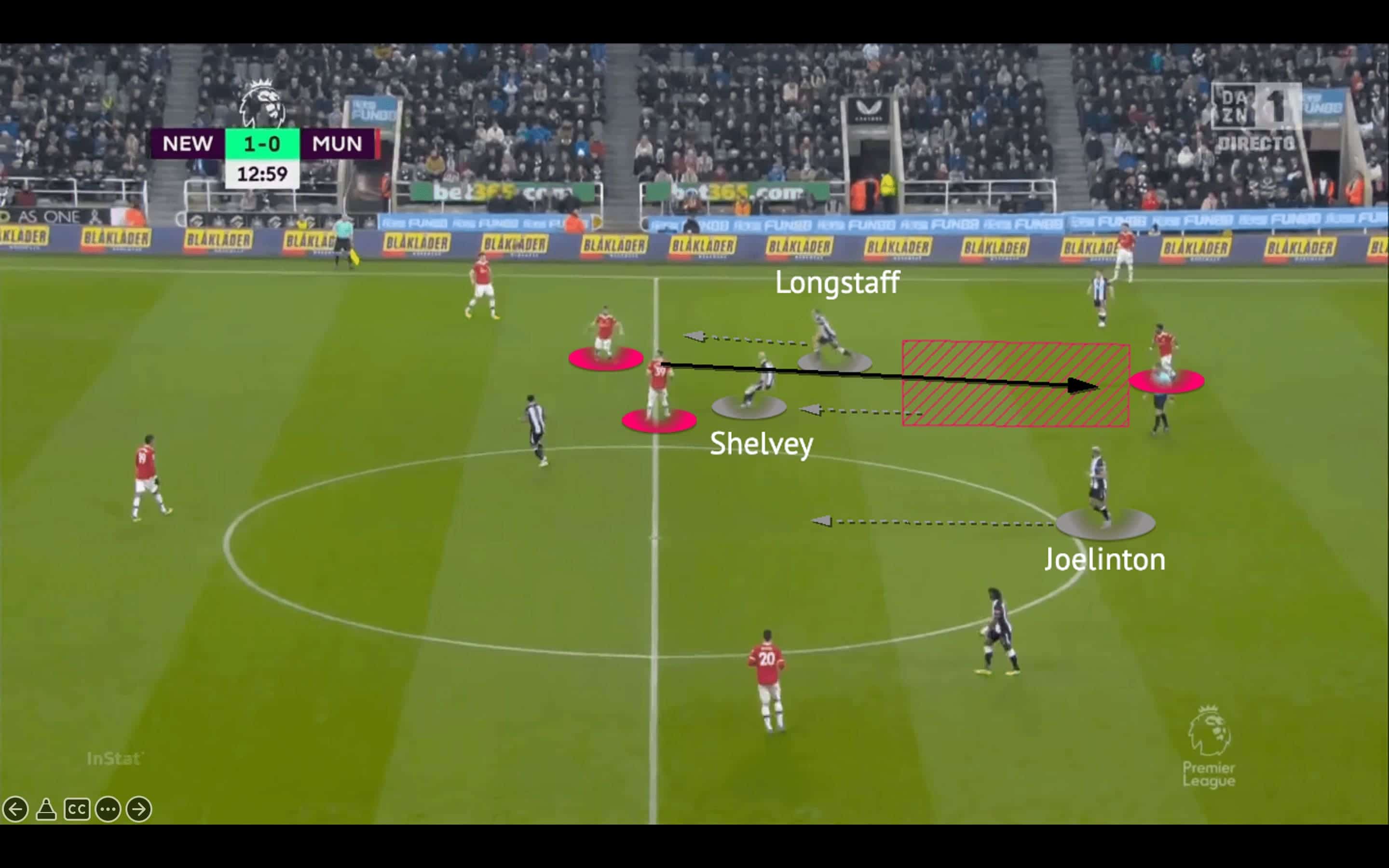

We showed the scenario before Cavani’s goal in the above example. Initially, Newcastle had enough numbers to press because the players went out to match the 2-1 shape of United. The height of the first line was not bad because they tightly shut the passing lane between centre-backs, and the ground diagonal passing lane to the right-back was also blocked.

But the problem was usually about individual decisions. Here, Saint-Maximin guessed Harry Maguire would be finding the right-back, so he moved away from the opposition 6. But the body feint of Maguire was actually a decoy to disguise Saint-Maximin, then United beat the press with a simple one-two because Saint-Maximin gave up on marking Scott McTominay.

In addition, the trigger of Newcastle’s pressing must be clearer, or else they would expose spaces behind the midfield after jumping out because the last line was not good at closing down the opponents in front.

On the above occasion, two of the midfielders went out to press but they were unable to close the angle of the passer because of the huge travelling distance. Then, United played behind the Magpies midfield and found Fred, who had the space to receive and turn. Closing that spaces behind the midfield Howe wanted, because the quality attackers in the Premier League such as Bernardo Silva, Bruno Fernandes, and Diogo Jota could do so much harm if they were given spaces to turn in the centre. As Howe only had less than three months to transmit his idea, we were yet to figure out the exact solution in this case. One of them might be reinforcing the “pressing & cover” awareness, so the midfield trio should stay as a triangle to support and cover each other, not in the same horizontal zone.

On the pitch, Joelinton might need to cover Shelvey on the right side, while Saint-Maximin coming in to balance if he was not the gambling winger. But we will how the club or the coaching staff would solve it, for example, purchasing a more aggressive centre-back such as Diego Carlos could also be an off-pitch solution as well.

Conclusion

We believe the changes of Howe were more about the way he manages the daily process, the responsibility of staff, training drills, and other details. The philosophy of Howe’s football was the same in the core, and some details were upgraded after he took reflections during the sabbatical days. Would that be enough to secure a Premier League place in the 2022-23 season? We don’t know yet because the team also had different departments to improve, such as mentally being tougher and more focused to reduce individual errors, or being more patient and looking for more dominance in a game, so the opponents could not attack them.

Comments