FC Andorra have seen an astronomic rise in the last couple of years. In 2018, they were just a fifth-division side in Spain playing their football in front of crowds of no more than 30 people. Fast forward to 2023, however, and this is well and truly a completely rejuvenated club. Not only are they playing competitive football in the Segunda Division, just a tier under LaLiga, but are also owned by the Barcelona legend Gerard Piqué and coached by Eder Sarabia, the man who was once Quique Setién’s assistant at both Real Betis and Barcelona themselves.

At the moment of writing, they are a mid-table Segunda club but according to Piqué’s words, they have Champions League aspirations. While they may still be far from that level, their change in fortune did coincide with a transformation in the philosophy and tactics of the club. But what is the secret behind their meteoric rise?

This tactical analysis will aim to answer that question and dig deeper into their newfound success.

Age profile & team playstyle

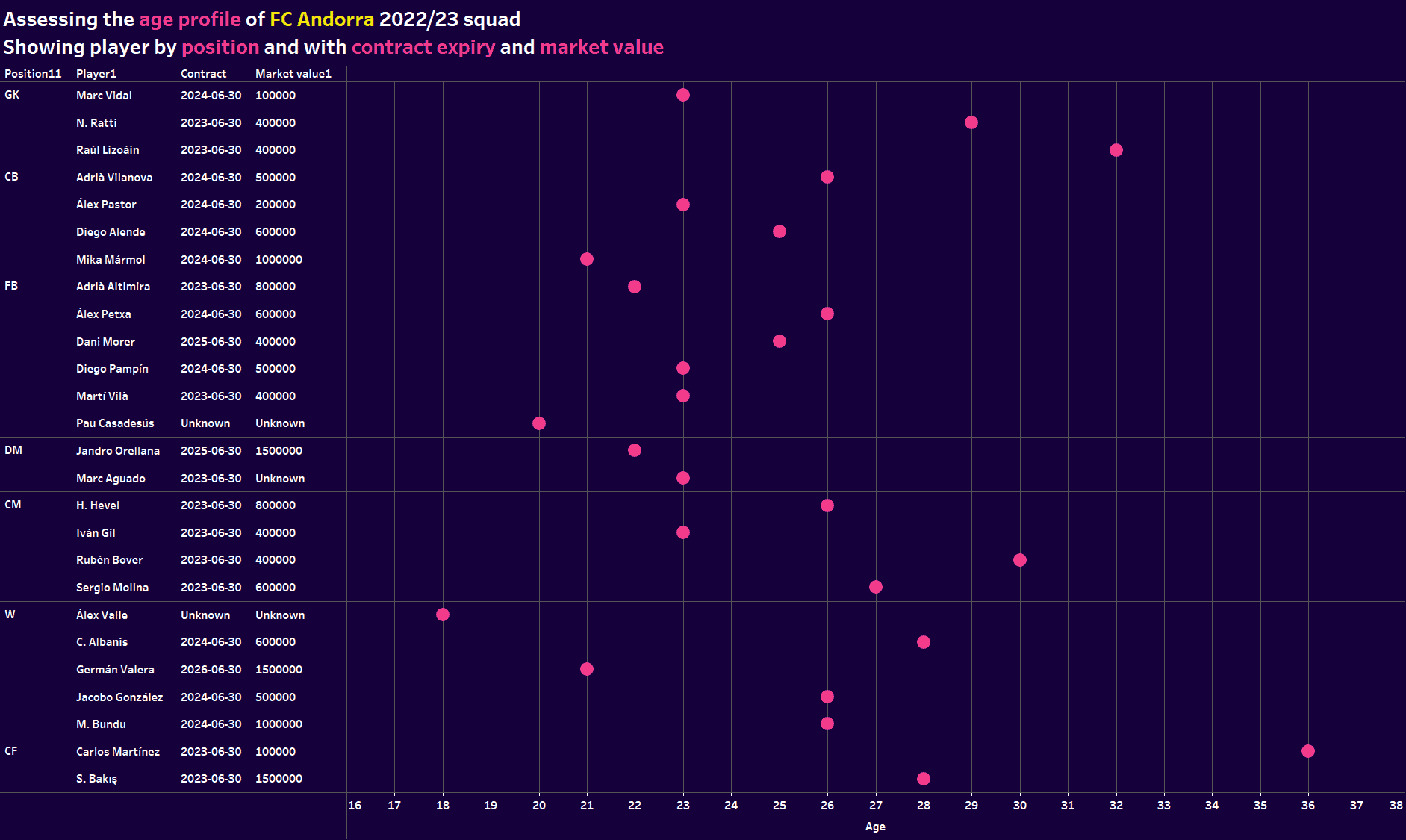

Part of what makes Andorra so exciting is the fact they’re playing with an extremely young team. With an average age of 25.1, they are the third-youngest team in the Segunda Division, which is impressive considering this is where most teams’ B sides play and those teams are largely comprised of youth players. Looking at the graph here, we can see the age profile of the team we like to divide into three main categories: youth prospects (up to 23 years of age), players in their prime years (24-29) and experienced players (30+).

A well-balanced team will have players evenly distributed into all three categories but every long-term project needs high-quality prime players with high-potential youth prospects. At Andorra, this seems to be the case.

The majority of their players are just entering their prime years or are exciting young talents. There are also some interesting names from clubs like Barcelona, Espanyol and Real Sociedad, which means their recruitment has been solid and their pull is already at an impressive level. When it comes to the more experienced players, there aren’t many but they are sprinkled across the squad strategically. The 28-year-old Sinan Bakış, for example, is the team’s lead goal-scorer and brings experience and maturity to the forward line. The same goes for Hector Hevel and Sergio Molina, both 26, in midfield and Kevin Nicolás Ratti (29) between the sticks.

Another thing that makes Andorra so exciting is the philosophy behind their play. Sarabia is practising a clear game model that’s founded on positional play, finding superiorities and establishing control over games through meaningful possession. While they are yet to translate these principles into clear advantages and domination on the pitch, having a game model ingrained in the squad with a clear return on investment on their talent ID is an excellent start.

Speaking of the game model, the following graph will tell us more about their team playstyle.

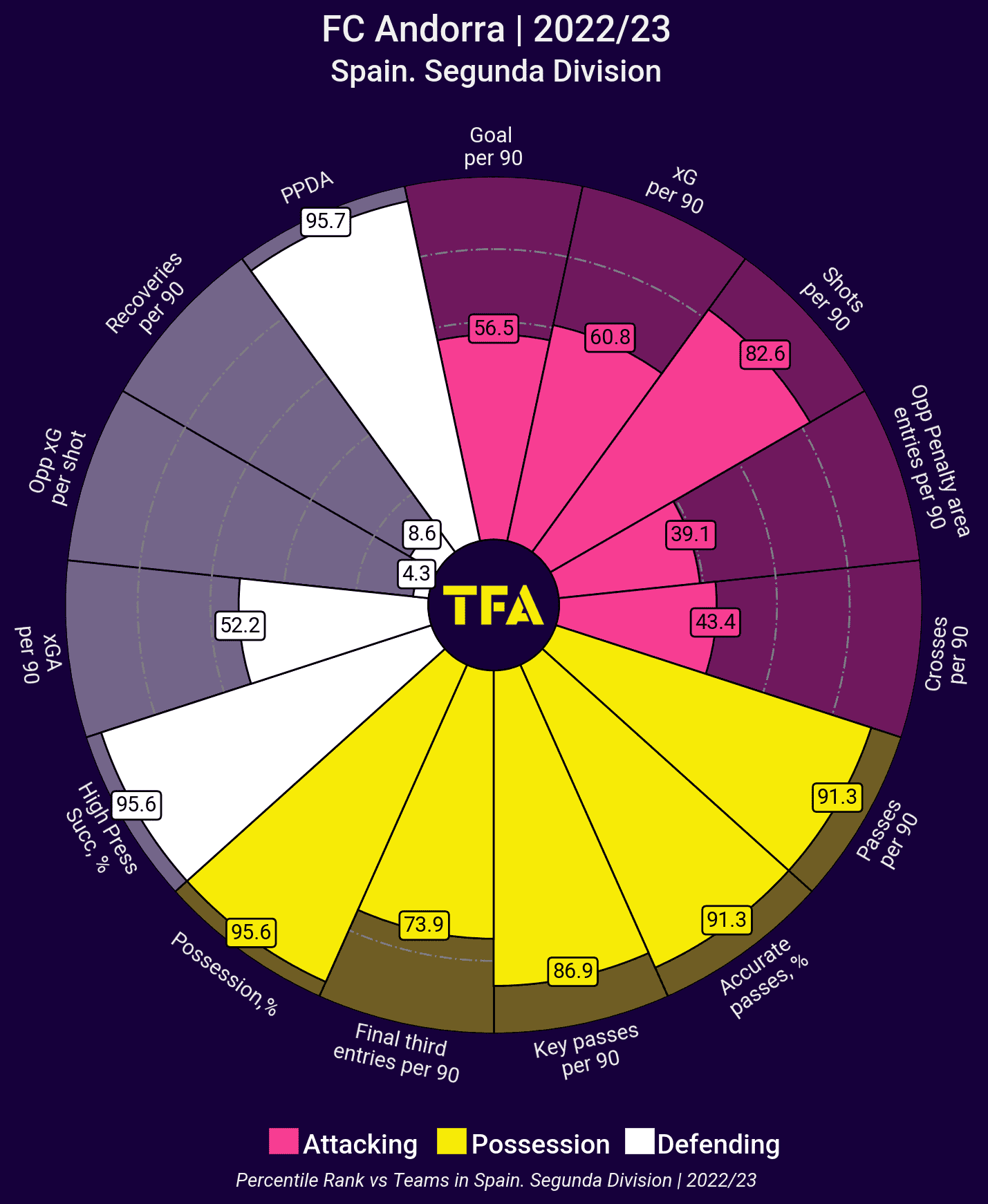

The graph divides Andorra’s style into three categories: attacking, defending and possession. And according to our data analysis, all three can give us a clear(er) picture of their game model: Andorra are a high-pressing, high-possession and high-volume attacking side. There aren’t many teams in Segunda who are more aggressive off the ball or many who control the ball better than Sarabia’s side. All of that, however, is yet to yield enough in the final third and this is where some issues can already be identified. More on that later on in our tactical analysis.

But what do we know about their key principles in every phase of the game? Let’s start at the beginning.

Build-up mechanisms

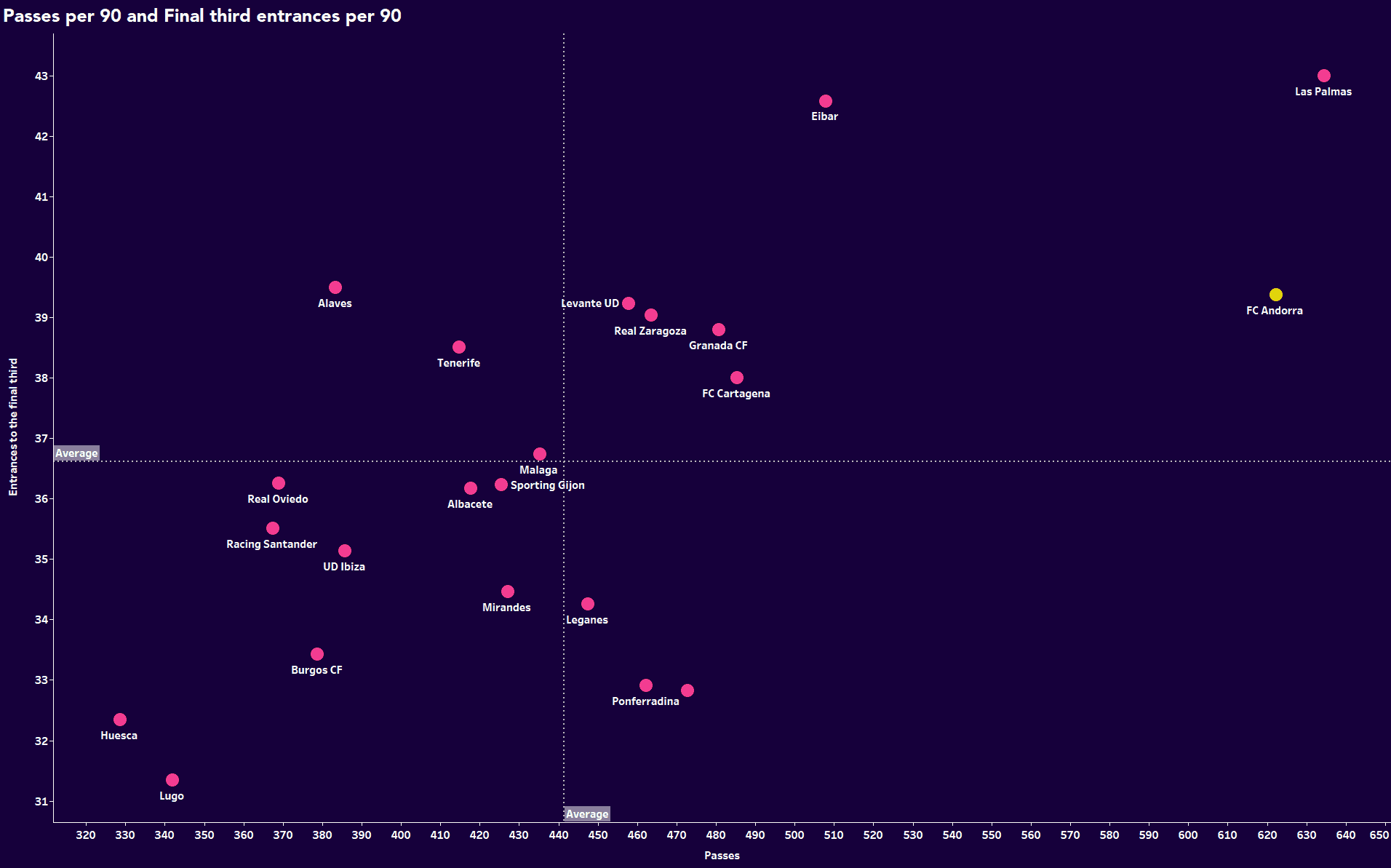

By far the most interesting (and successful) aspect of Andorra’s philosophy is their build-up play. Being a heavy possession side, they are often reliant on the first phase to establish control and dominate the ball. Looking at the pure data once more, we can see that this is indeed what they do better than most other teams in the Segunda Division. In fact, when it comes to total passes deployed, they are the team with the second-highest total and per 90 volume while also being the team with the highest average possession (66%).

This is already moulding the picture of what kind of a team we’re talking about. Andorra are also the most accurate team in the league with 81.08% accuracy and tend to be safe and patient in possession, registering the least losses overall and per 90. When you factor in they don’t rely on through balls and long balls while also having the fourth-most passes into the final third and the second-highest passing rate at 14.9, we can conclude they are indeed safe but not too safe.

Once the opportunity arises, Andorra are quick to execute on their superiorities, finding the free man through incisive and accurate passing. After all, they have the second-most progressive passes and the most progressive runs in the league, which are the direct result of their style of play and the profile of players in and around the backline. So let’s explore some of those mechanisms that make them such build-up machines.

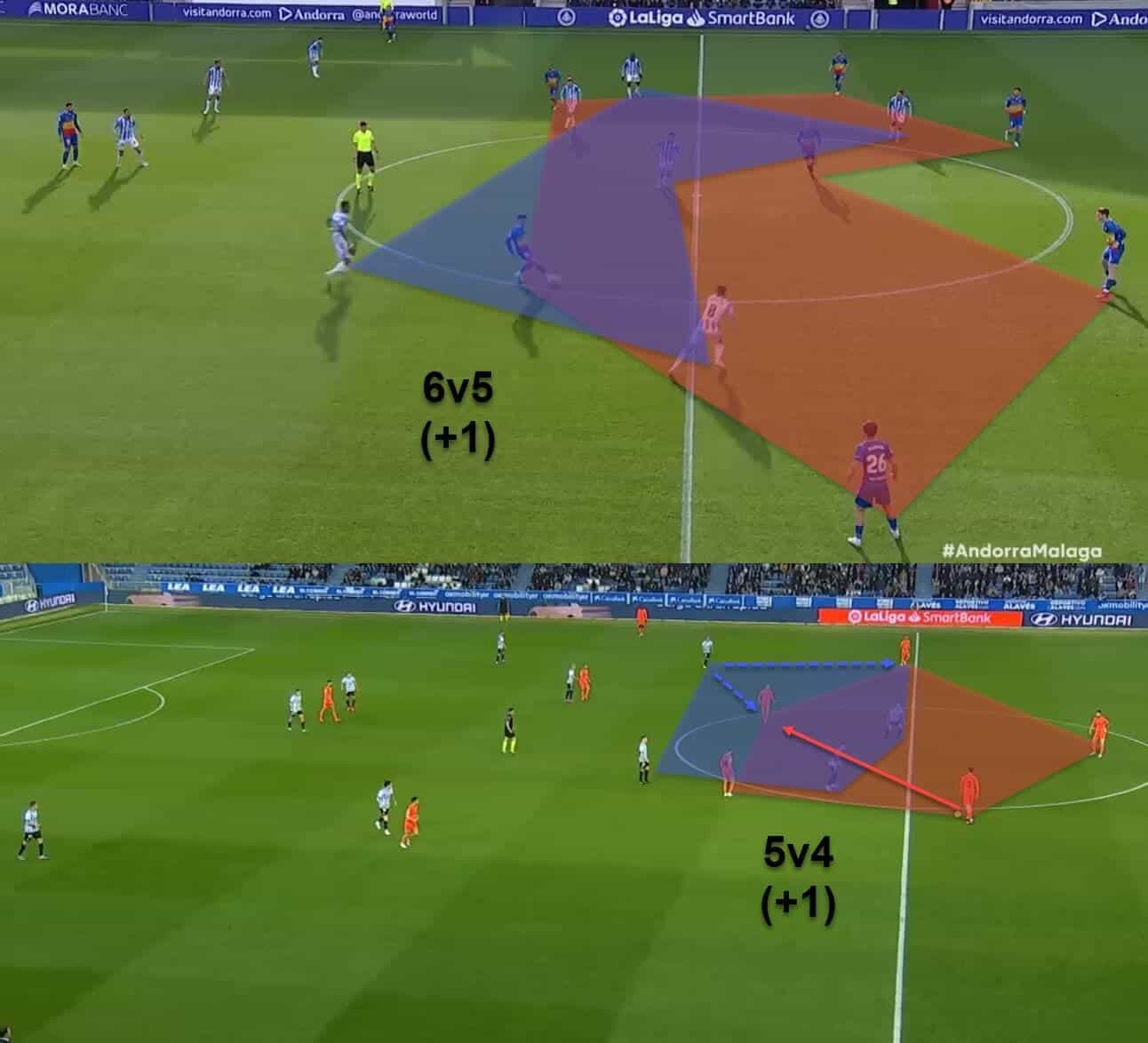

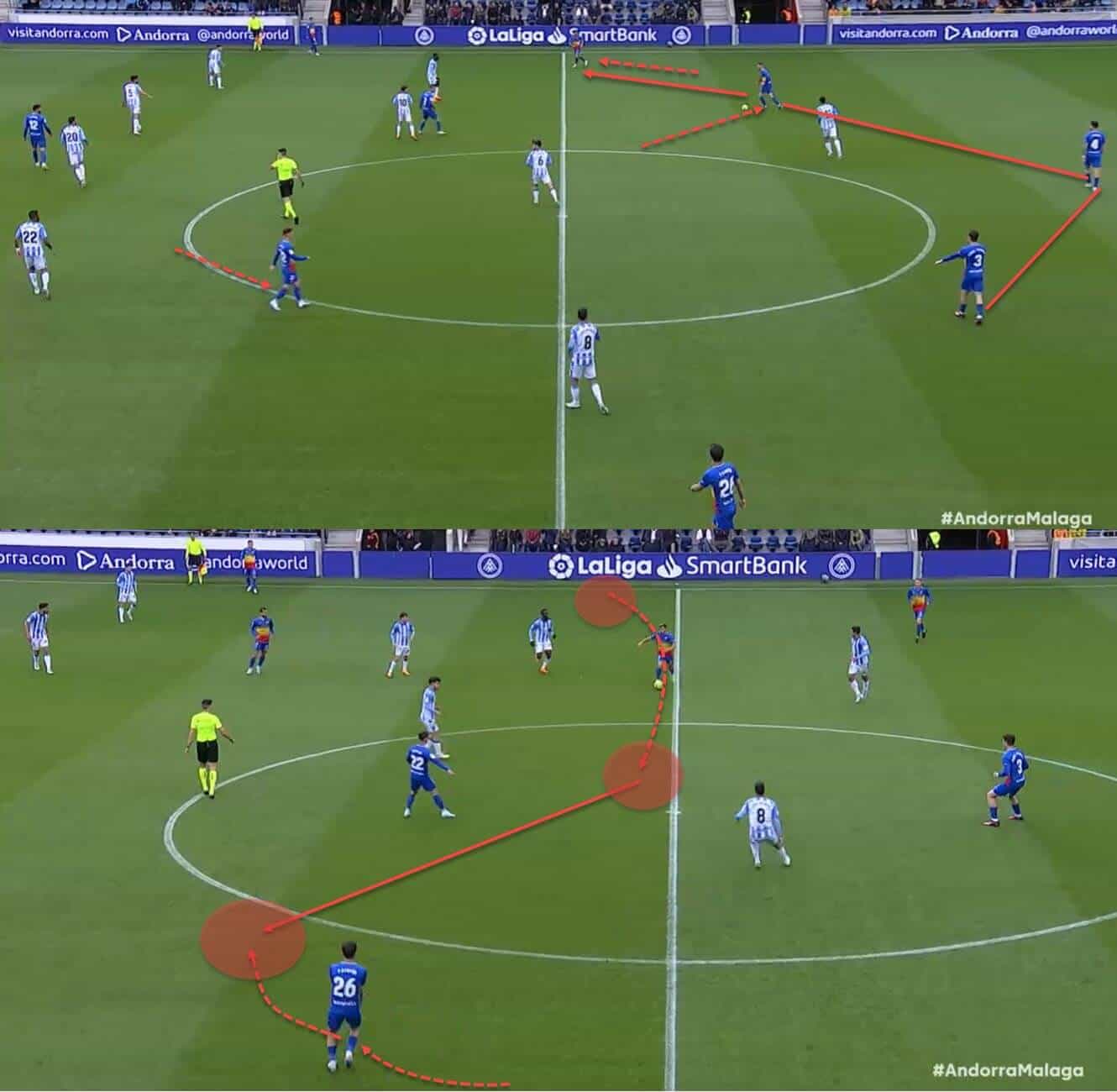

One thing we have to note about Andorra is that they are quite adaptable in their approach. Generally, they’ve been set up in a 4-3-3 in the 58% of their games in the league and that seems to be Sarabia’s go-to lineup in most games. However, this is largely only true on paper. Andorra will morph their structure according to the opponent and their defensive block. Since establishing superiorities is a must, we’ll often see them apply the ‘+1 rule’.

The examples here show us this well. If the opposition sends five players into a high press, Andorra will use at least six to bypass it. If the opposition has only four players in Andorra’s half, Sarabia will instruct five of his players to drop deeper to assist the build-up. This is a fairly basic principle of most possession-heavy sides but it suits Andorra’s tactics perfectly. This way, they rely on the high technical quality of their players to play out of the press and through the opposition’s defensive block. In such scenarios, their build-up phase becomes one big game of rondo.

As noted previously in our tactical analysis, a flexible approach is preferred in the first phase. This means the four-in-the-back structure will transform accordingly. Often, however, Sarabia will prefer the three-at-the-back system which gives his team an inherent numerical superiority against most defensive setups in the Segunda and forces the opposition to invest more players into their first line of press.

How they create the three-man backline differs from game to game and opponent to opponent. There are two main ways Andorra aim to accomplish this: dropping one full-back or the pivot into the backline. Let’s explore the former scenario first.

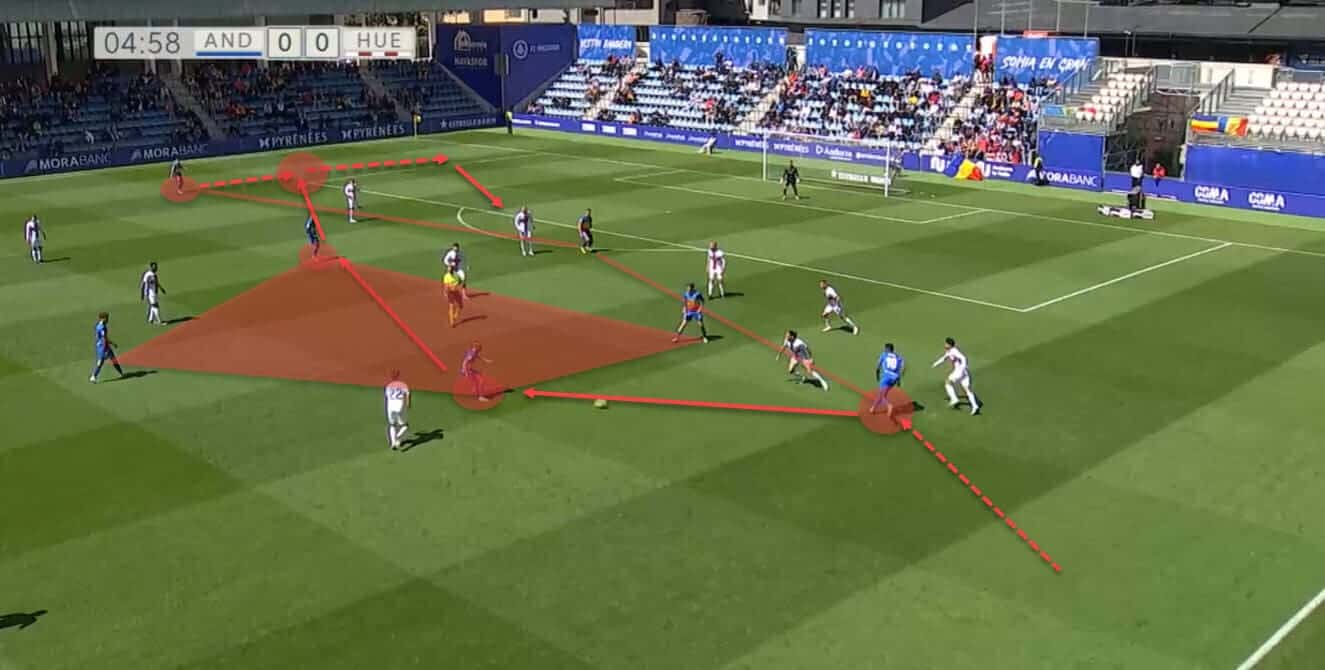

We can see in this sequence the positioning of the full-backs is often asymmetrical; if one of them drops, the other will rise and vice versa. Both players are comfortable being the wide defender in a back three and both will assume similar roles in possession once that has been established. In this particular sequence, we can see the left-back drop to bait the press and create more space for the pivot, who is the key man to access in the build-up phase. But note the initial positioning of the full-backs; they are both extremely narrow and will drift wide only as and if necessary. In fact, generally, it will be the wide centre-midfielder who will drift to open new passing lanes and manipulate the second line of the opposition’s defensive block.

Andorra value central domination highly and through it, they maintain compactness across the thirds. The sequence we’re discussing, however, is showing us several more aspects of their build-up too: from angle support and manipulation to progressive running and the third-man principle, it’s an action that paints an almost perfect picture of what Andorra are all about in the first phase. But let’s stick to the compactness aspect for now.

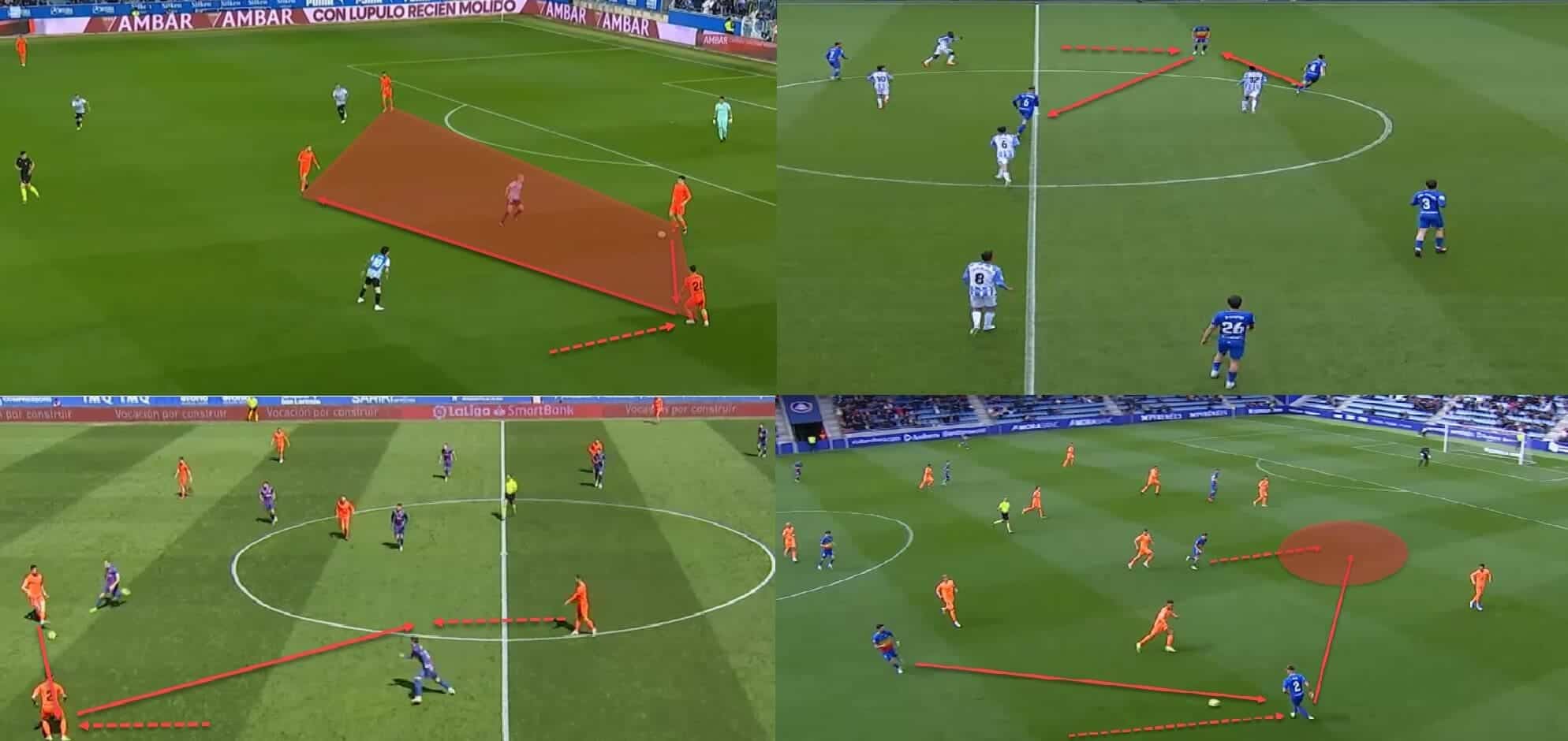

Here, the full-backs don’t form the back three but rather, they have wider initial positioning and then they invert into midfield. This ensures compactness and gives the ball carrier another passing option once the opposition’s centre of the pitch has been overloaded. Again, it seems like a simple premise but it requires compatible profiles who are comfortable with such roles in possession. Nowadays, inverted full-backs are what some elite teams in Europe like Manchester City and Arsenal do and Andorra seem to be following the trend and executing it quite well.

But it’s not only the full-backs who do it. In some cases, we’ll also see the centre-backs push up into higher positions to open passing lanes and aid progression. This is most notable with the left centre-back, the former Barcelona youth product Mika Mármol. His ability on the ball and athleticism enable him to progress play both via running and passing and often, we’ll see him advance with or without the ball. It’s in those instances that Andorra become slightly more direct and vertical than they normally are.

Mármol’s runs are triggers for the wingers and centre-midfielders to attack space and this is especially true for the right centre-midfielder and the right-winger. But we’ll discuss that more in the next section of our tactical analysis. One final aspect of Andorra’s build-up we have to mention is the angle support. There is something very Brighton-esque about Andorra’s first phase of play. Their backline will regularly stop on the ball, roll it with the sole of the foot and bait the press that way or by going backwards to activate the chase.

Once that happens, they will exploit different angles to access the pivot behind the first line of the opposition’s press or will use that mechanism to create higher up the pitch.

The full-backs will drop into the backline to force the opposition to engage more players and then the ball will be recycled until a good angle to access the free man is found. These rotations include but are not limited to full-backs dropping into the backline, wide centre-midfielders drifting behind their respective wingers and even the striker joining the midfield to both overload the centre and create space behind him.

All of this leads to excellent third-man sequences and access of the free man, both of which are powerful progression and creation tools for Sarabia’s men. But how do they fare in the final third and what’s stopping them from soaring even higher in the Segunda Division?

Final third principles

While the build-up phase remains the most sophisticated and most successful aspect of Andorra’s philosophy, the final third principles are much simpler and offer less in comparison. Similarly, while Andorra as a team are methodical and patient in the build-up, their attack is fast and direct. This isn’t to say they rely on high verticality for chance creation but it does seem to be a tool in their arsenal.

Generally, however, the key is to access central space and then distribute the ball out wide. Andorra are excellent at creating and exploiting superiorities and this is where most of their final third creation comes into play too. The pivot, in particular, is a point of interest. While he’s used as a primary tool to escape the press or break the first line of the opposition’s defensive line, the no.6 is also the foundation of their chance creation.

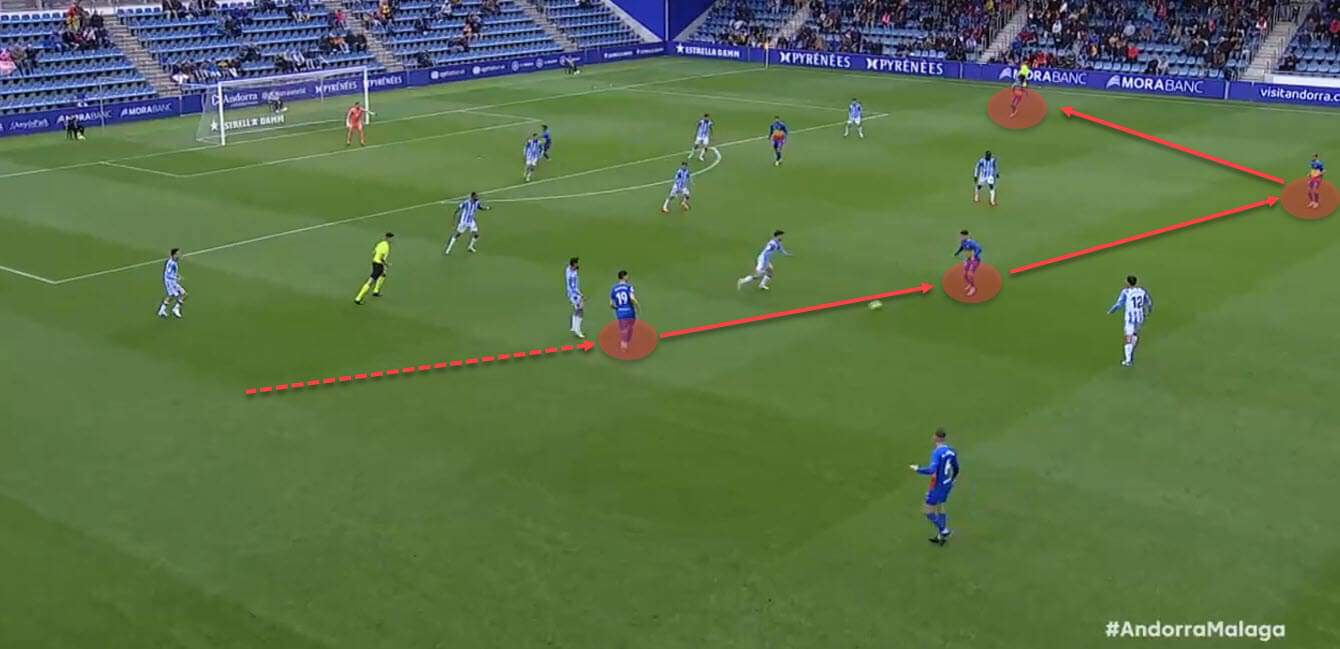

Take these two images as an example. In both scenarios, Andorra worked hard to first create enough space for the pivot to receive the ball, then accessed him and finally, gave him options to aim for further up the pitch. Usually, these options will present themselves in the form of runners. For a highly positional team, Andorra do have verticality triggers that turn them into a much more direct team once they approach the final third. In both of the examples we just discussed, the pivot was a platform to access those runners who attack space. In that sense, Andorra are all about exploiting the space in the final third, not necessarily dominating it.

There are two main things we have to talk about when it comes to their chance creation: isolations and cutbacks. Andorra are a team that dribbles a lot and this is directly linked to their isolation tactics. Having wide wingers and utilising maximum width seems to be a part of Sarabia’s blueprint; we can often find their wingers in wide starting positions and preferably isolated with their markers. Andorra will then use different mechanisms to access those wingers and then look for cutback or deep completions near the box.

The following sequence shows us a fairly standard procedure in the final third.

The winger receives a long ball in an isolated scenario on the right flank. Immediately, he looks to close in on the box and follow up with a cutback (or a deep completion) to one of the advanced interiors. In that particular instance, the winger doesn’t directly take on his man but more often than not, they will do exactly that. At 1037 1v1s in total and 27.37 per 90, Andorra are bettered in the league on pure volume of their dribbling by only one other side. Quite clearly, isolated wingers and take-ons are a big part of their tactics.

But let’s look at another very similar example next. Again, we find the winger in an initially wide position who had been accessed isolated out wide. As soon as that happens, he will look to cut inside (or beat his man) and then aim for deep completions (or cutbacks) around the box. This also answers the question of how are Andorra so flank-focused while still not being a cross-heavy team at all. It’s simple – their actions and main final third principles of attack do focus on the isolated wingers a lot but they won’t distribute that many high crosses but will rather look for different types of passes.

Here, once again, it’s not the winger looking to gain access to the outside of the defender but rather inverting and then combining on the ground and across shorter distances within or near the penalty area. And considering there aren’t any real aerial threats in this Andorra side, this tactic does not come as a big surprise. They are, after all, the team with the fewest aerial duels in the league and also the team with the lowest success rate in aerial battles as well. In that same regard, the fact they register very few headed shots seems fairly obvious and completely understandable.

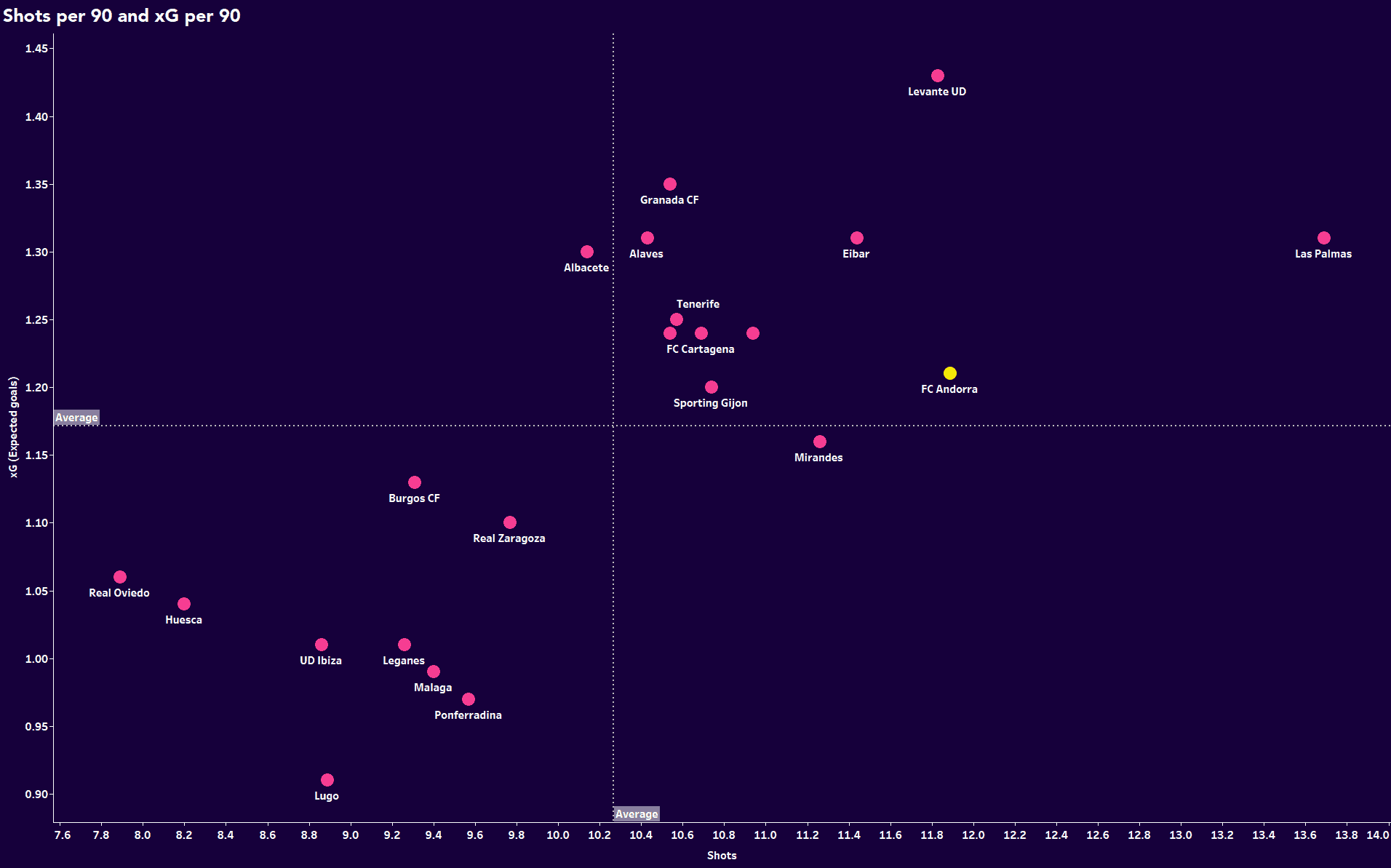

But it is also a clear weakness in their game model or the squad as a whole. Andorra aren’t a team who takes enough advantage of their set-piece play and despite being the team with the fourth most corners in the league, that is rarely translated into a palpable final product. This isn’t the only weakness they have though. As a whole, finishing seems to be a problem, as is the lack of goalscorers apart from Bakış, their lead striker. Looking at the data, they’ve managed to score 34 goals at the time of writing from 38.14 xG, underperforming their expected goals so far. Similarly, with 0.094 xG per shot, they still lag behind the league average of 0.11 xG per shot. Yes, when it comes to xG per 90, they are still above average, as seen in the following graph but for all their in-possession prowess, Andorra are still underperforming in the final third.

But there is more. They are the team with the second-most total shots outside the box this season in the Segunda and this does explain the below-average xG per shot tally as shots from outside the box usually generate lower xG figures. But when you pair that up with the aforementioned weaknesses and add the fact they rank around the middle of the table for touches in the box, a clearer picture of their struggles starts to form.

All of this, however, isn’t that much of a structural problem but rather a problem of quality, or lack thereof. Take the following image as an example.

Andorra’s final third in-possession structure is more than solid. It’s quite intriguing that they’re regularly inverting their full-backs for compactness and counter-pressing purposes or positioning them just behind their wide isolated wingers. This forms a box in the middle of the pitch with the two interiors often pushing up either side of the striker. The structure is well designed for circulation and sustained pressure, which Andorra do decently well.

Often, however, it’s the final pass or the impatience that causes issues. With so many attempts being taken from outside the box, it could signal the lack of automatisms in certain areas of the final third where such a thing would be more than welcome. Of course, many coaches give their players a lot of freedom in the final third but certain mechanisms need to be in place to make chance creation easier, faster and smoother.

But speaking of good structure for pinning the opposition back, the following example will show us more.

Notice how this is fairly similar to the previous sequence and that’s a good indicator of something regular rather than an isolated case. Andorra’s wingers will often invert, in which case the full-backs can still overlap to maintain width, but the goal is always to access the underloaded side where the isolation would ideally be achieved for the far-side winger. That was the case in the previous example and is now present again in this one.

In this particular sequence, however, it should be noted the space occupation isn’t quite optimal. The left half-space has been abandoned so Andorra have to commit to switching sides even if they don’t necessarily want to. But the half-spaces are still a big point of interest in their chance-creation, especially with the interiors often pushing up or penetrating that channel with runs from the deep. Generally, they will get triggered by the backline.

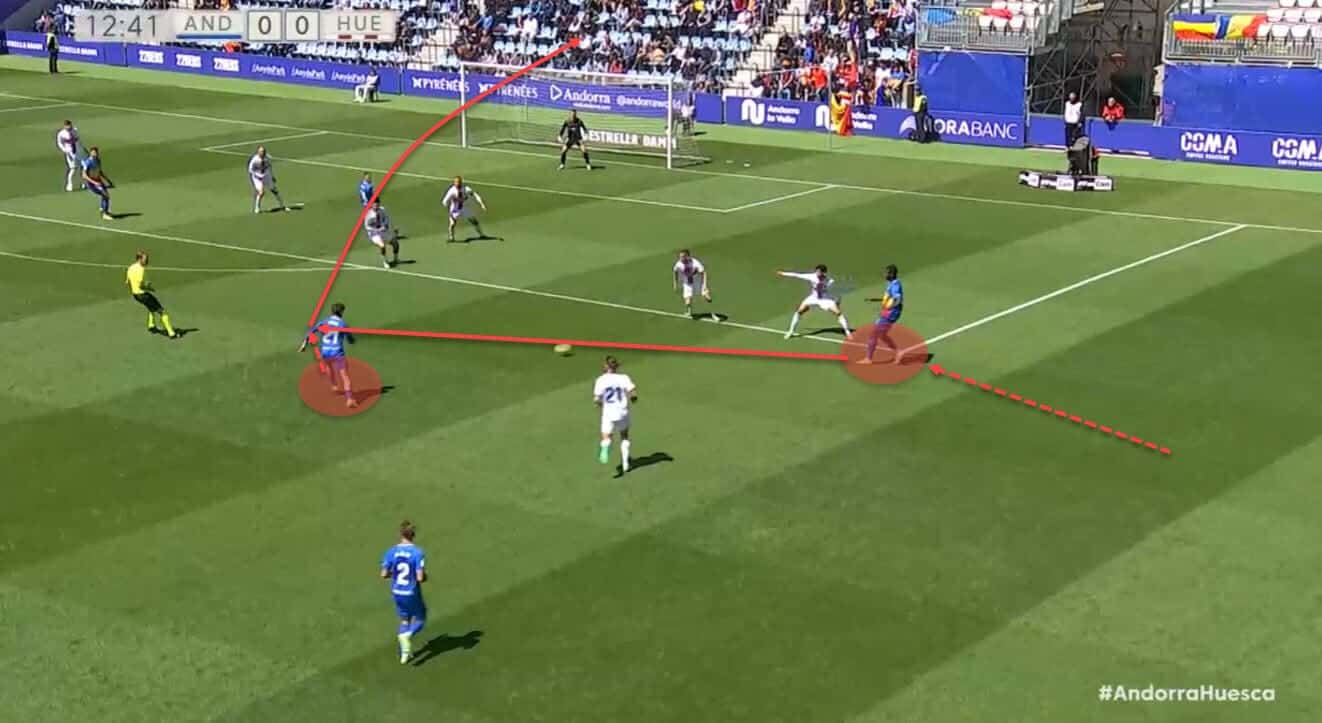

In the following example, we’ll see when that’s the case.

This is a verticality trigger following a movement manipulation of some sort. Andorra are quite good at moving the opposition to open pockets of space or create and access the free man. This is best utilised in the first phase, of course, but can be a chance creation tool as well. In that case, it’s most apparent in long and direct distribution towards the opposition’s goal and into open space.

The aim is to attract markers centrally, move them into a narrow position and then eject their runners from the deep. Interestingly, the aforementioned Mármol, the left centre-back, is a big verticality trigger for their runners too. We already talked about his tendency to run with the ball as well as his technical quality in possession but he is also a big part of not only their progression but also chance creation.

Mármol will make runs from the deep, engage in one-twos with teammates and often send diagonals to the isolated far-side winger or into a half-space penetrator, as seen below.

This confirms our initial thesis of Andorra being more patient in the build-up but then switching to a more direct approach once they’re ready to attack. However, despite the good structure and movement, the issues we mentioned earlier in the analysis are keeping them from transferring their first-phase excellence into much more.

Defensive phase

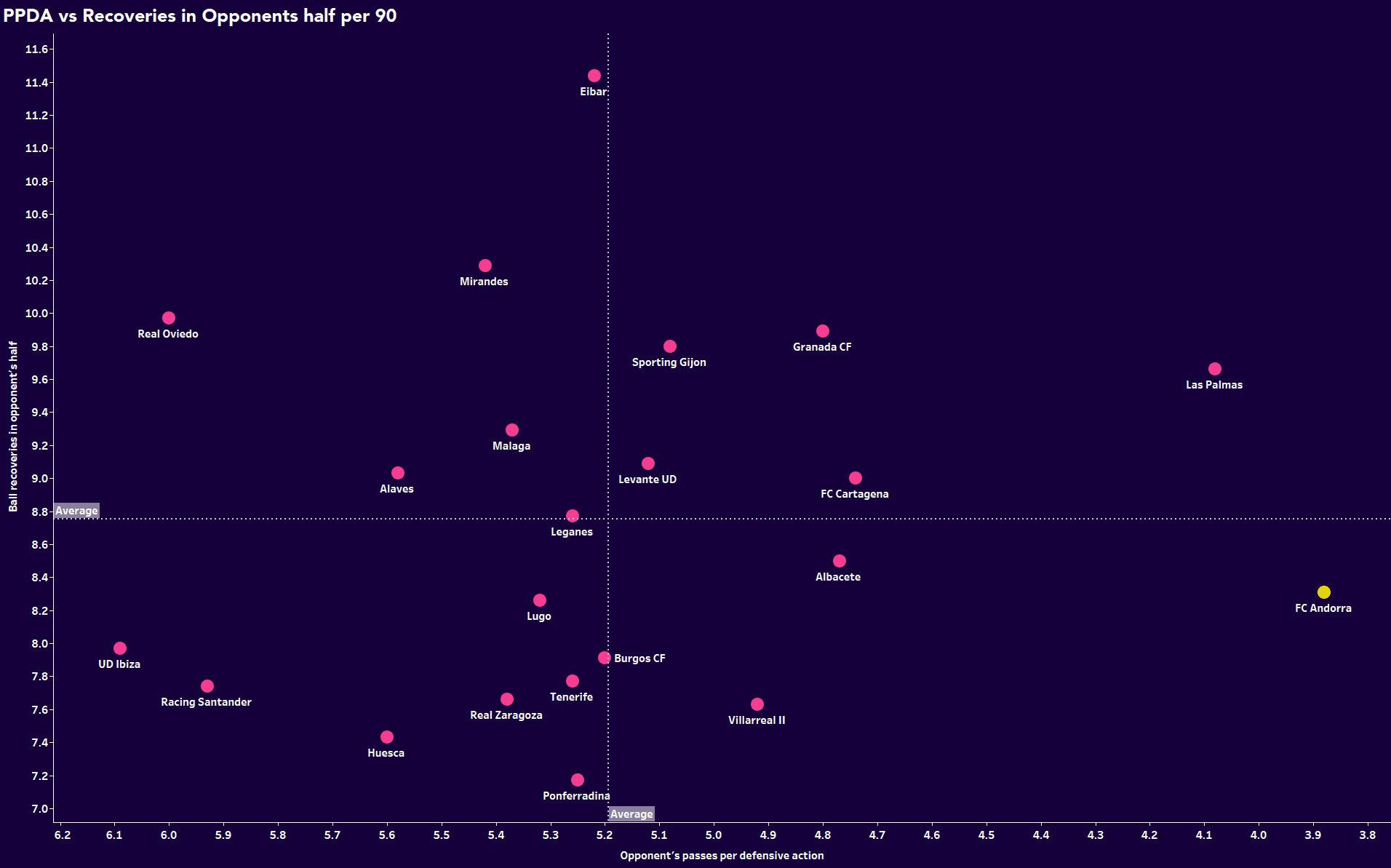

When it comes to the off-the-ball defensive phase, Andorra are best described as a high-pressing, high-intensity team. Considering Sarabia is their coach and they take great inspiration from some of Europe’s best teams, this hardly comes as a surprise. When we look at the numbers in the following graph, we can see that distinct style firsthand.

When measuring PPDA (passes per defensive action ) numbers and recoveries in the opposition’s half, Andorra comfortably top the former metric but intriguingly, don’t cross the average line in the latter. In other words, they press high often but don’t necessarily recover the ball high as well. This is also backed up by the fact they are the team with the fewest interceptions in the league.

On top of very low PPDA values (lower means more high pressing in general), they also rank second in challenge intensity which measures the rate of certain defensive actions a team makes. This means they don’t allow the opposition to string too many passes together without being interrupted and they are very aggressive in doing so. This is important because even though we’ve divided this tactical analysis into three distinct game phases, all three are connected and a part of one whole. As such, the defensive phase is directly correlated to the offensive phase as high pressing can and is a tool for chance creation and pitch control too.

But considering the low recoveries rate they register in the opposition’s half, we can conclude this isn’t as polished at Andorra as of yet. That said, the sheer defensive numbers this season have been decent: at the moment of writing, they conceded 29 goals (0.77 per 90), four from headers, five from penalties and two outside the penalty area. But their xGA value is currently at 38.07 (0.118 xG per shot), signalling the opposition should be scoring more against them than they are.

As expected from a possession-heavy side, they don’t engage in too many defensive duels (second fewest defensive duels overall and per 90) but are quite good at winning them (fourth-best success rate in the league). Interestingly, this is also evident in how they block shots – they don’t block many overall compared to other teams but they do block 28.6% of all of them, which is again the fourth-best success rate in Segunda. We also can’t exactly talk about a general defensive or pressing shape as that depends on the opposition a lot.

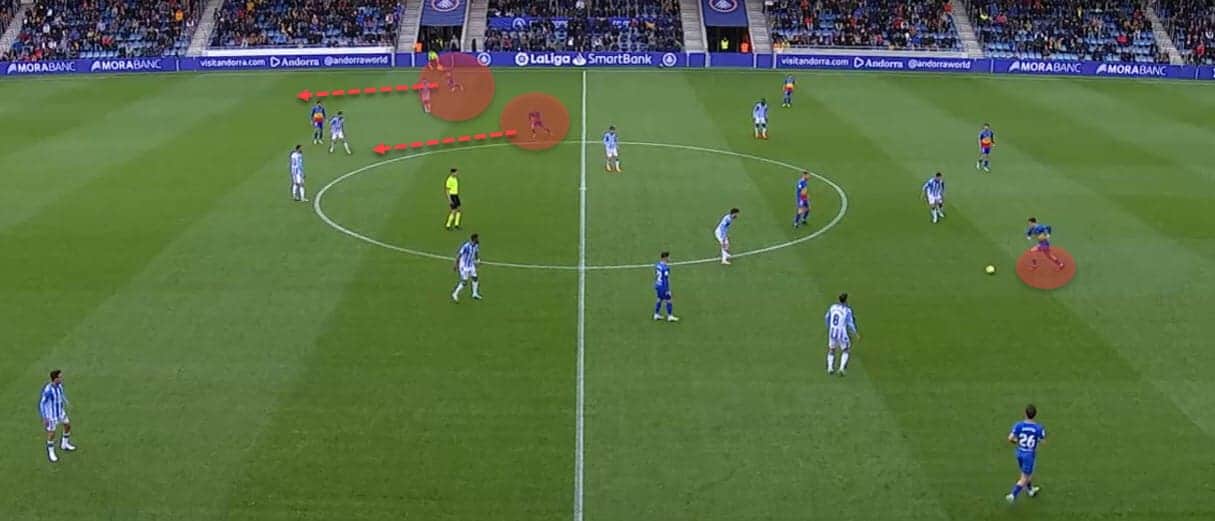

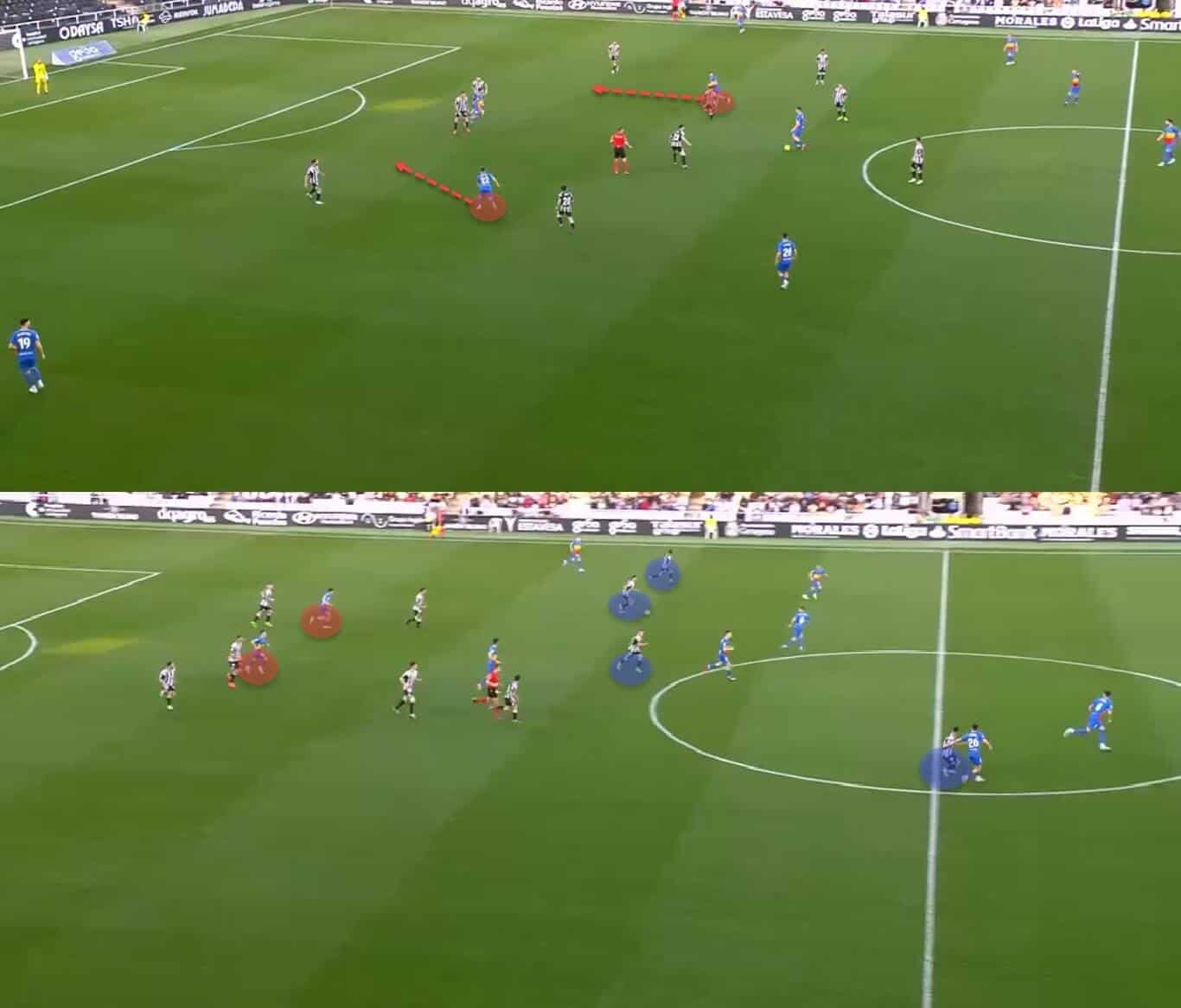

This image does a good job of giving us a fairly usual structure off the ball but again, it’s the direct result of the way the opponent wants to build up. That tells us Andorra are very man-oriented when pushing higher up and will try and mimic the opposition’s structure as much as they can. There are, however, some tweaks and interesting rotations they often do. In general, the striker will always follow the ball and press the goalkeeper and one of the centre-backs.

The midfielders are tasked with tracking their counterparts and will do so quite rigidly – if the opposition’s midfielders drift wide, so will Andorra’s. If they drop deep, so will Andorra’s. And if they stay central, so will Andorra’s. It is a fairly simple mechanic that gets them results but can also be a weakness, which we’ll explore further down the line of this tactical analysis. The wide players follow a similar route.

Generally, we will see them track their men but this is also where Andorra deploy an asymmetrical pressing system.

In this image, we’ve highlighted both wingers and full-backs to show their current positioning and movement. Notice how the RW is high pressing alongside the striker while the other tracks back and effectively drops into the backline. A very similar thing happens with the LB who is a part of the defensive line while the RB pushes up to press. Again, this is because of the man orientation – if the opponent attacks with their wide players forming an asymmetrical structure, Andorra will try and mimic that by instructing their own wide players to do the same.

Another very important aspect of their defending is compactness. Being compact in every phase leads to better recycling and link-up in attack and easier space blocking and counter-pressing in defence. Andorra will try and make the pitch small when defending, funnelling the opposition into the central and narrow corridors where they can close in on them more easily. This is directly connected to their rest defence structure.

Generally, they will compose it with the centre-backs, one midfielder (often the pivot but can be one of the interiors) and two inverted full-backs.

And it has to be said that this is largely effective. Andorra are quick to snuff out attacks and do so efficiently too, registering the second-fewest fouls overall and per 90 (only 10.4 per 90) and having the fewest number of yellow cards in the league at the moment of writing (57). On top of that, while they do concede the fifth-most shots against at 324, their 8.55 shots against per 90 are still below the league average of 9.48. Interestingly, despite the low number of fouls and yellow cards, they’ve received seven red cards in 2022/23, which is the third-highest tally in Segunda.

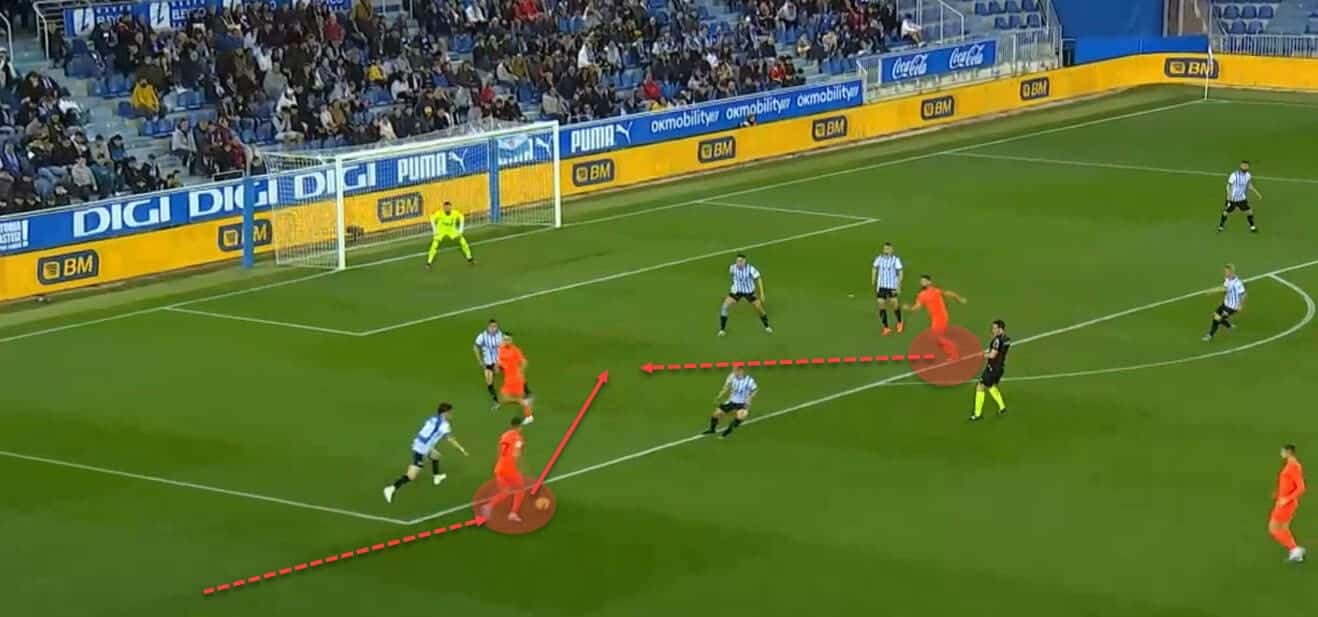

But despite being good at controlling space and snuffing out attacks, Andorra are still vulnerable in certain aspects of their game. For instance, good technical teams who can manipulate their man-marking and use the +1 can and do cause them a lot of trouble. Andorra often commit players high up the pitch and as is generally the case with heavy possession sides, they often suffer in transitional situations. The same is true for Sarabia’s men when their first line of pressure is broken and the opposition can attack space well.

Teams that have transitional player profiles and thrive in verticality or breaking forward quickly can take advantage of some of Andorra’s tendencies in possession. This is especially true when we consider their interiors often penetrate the half-space with their runs in behind and the centre-backs are sometimes instructed to carry the ball upfield and combine higher up the pitch.

This can leave Andorra vulnerable as the opposition can outnumber their rest defence or just attack with dynamic superiority in open space, as can be seen in this example.

Conclusion

Piqué’s ‘pet project’ is gaining more and more momentum as time passes. Andorra went from being a footnote of Spain’s football to one of the most exciting and intriguing projects in the country. But their meteoric rise also meant the management has had issues keeping up with the sudden improvement in opposition, expectations and financial requirements of being in the upper tiers of Spanish football.

So while they’ve been quick to jump from the fifth division to as high as the second, new and bigger challenges are bound to arise from it. All of that said, however, Andorra are still an exciting positional team who follows the trends of Europe’s best and has a distinct game model they believe in. On top of that, their squad has a healthy balance of youth prospects, players in their prime and experienced veterans, which is an excellent foundation for a long-term project.

It will be exciting to see where they go from here as Piqué seems to think the Champions League is not too far away. Is that just a dream or do Andorra really have that much excellence in them? The early signs are positive, albeit with certain caveats, but only time will tell.

Comments