It has been another season of mediocrity for Birmingham City this year. The West Midlands side ended 2019/20 in 20th place, just two points off the relegation zone. Their poor finish to the season led to Pep Clotet leaving the club earlier than initially agreed, after only joining the summer before. Former Real Madrid assistant manager Aitor Karanka has now been announced as his replacement. The Spaniard has experienced promotion to the Premier League with Middlesbrough in the past.

Nevertheless, set-pieces have been an interesting nuance within Birmingham’s season as a whole; They’ve had contrasting fortunes at either end of the pitch. The Blues scored 19 goals from dead-ball situations, the fourth highest in the league. Conversely, they conceded 25 goals, unsurprisingly the most in the EFL Championship.

In this tactical analysis in the form of a set-piece analysis I will use analysis to look at Birmingham’s tactics from set-pieces.

Defending corners

What is particularly noticeable when looking at their structure when defending corners is how much it can vary between games. Indeed, it is difficult to pinpoint an exact underpinning structure. Perhaps this is a factor in Birmingham’s poor defensive record: in that they cannot become familiarised with a consistent structure. Instead, in part due to Clotet favouring man-marking, Birmingham seem to evolve game-by-game.

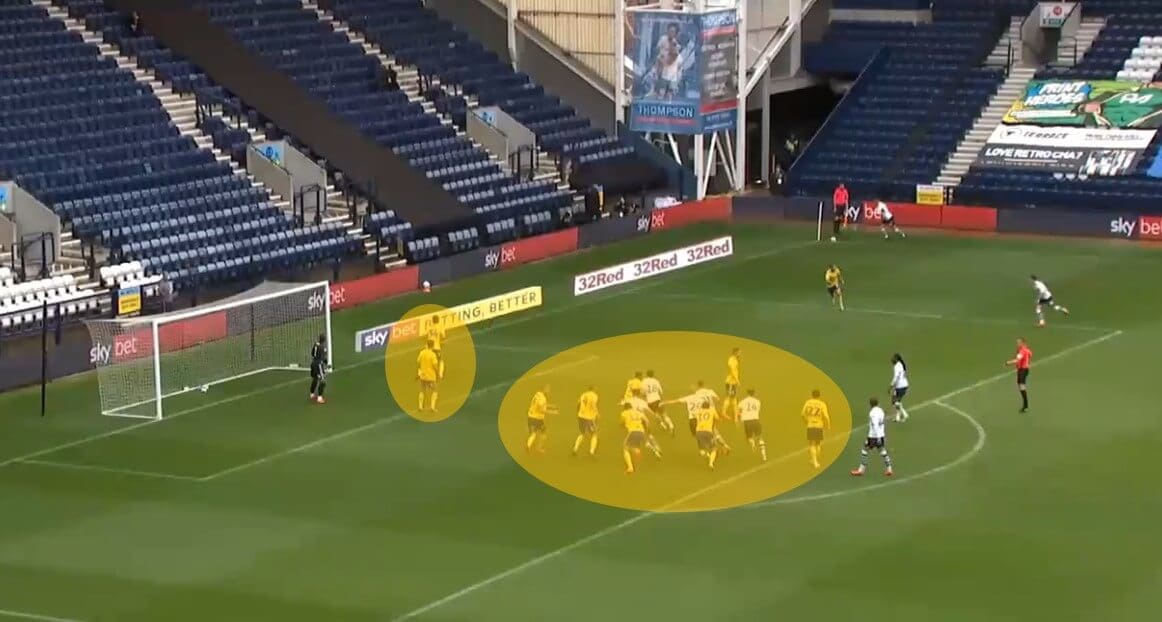

Firstly, here below is a basic view of the defensive structure that Birmingham tend to opt for. As you can see it is heavily focused on man-marking players, thus splitting a corner into individual duels. This, of course, has its downfalls – with it mainly being easier to then create separation and generate clearer chances. We can see a total of seven players in the vicinity of the edge of the box, all seemingly fixated by their own attacker. As a result of this grouping, it becomes simpler to execute blocking movements. The two zonal markers themselves are well-positioned, with them also being on a diagonal, therefore ensuring optimal staggering for an out-swinging delivery.

In this example below, however, the positioning within Birmingham’s defensive is more inefficient. The important thing here is that the corner is an out-swinger, therefore the ball shall be moving away from goal. Consequently, and unlike in-swingers, there is less of a need to protect the immediate near-post – as there is little chance of the ball going through due to its trajectory. The players who are protecting that space effectively has a pretty unproductive task; he would be better deployed elsewhere, such as an additional, central zonal marker. The occupation of the back-post is also arguably sub-optimal. Occupying this space would help maintain maximum coverage of all relevant space.

Here we can see how their structure is now is flat, neglecting the crucial staggering aspect. The point of staggering is to provide coverage at differing heights and depths. This then means that the delivery has to be much more accurate for the ball to find smaller available spaces. Birmingham’s spacing here in terms of actual coverage is good, it’s just the Blues have overlooked the defensive set-pieces principles of height, as well as depth. Also, they are no man-markers or zonal blockers to reduce deeper attackers’ momentum.

This next example illustrates how different the structure can be – though admittedly there are still two zonal markers. Here, against QPR, compared the previous Fulham example, we can see a greater number of man-markers located in and around the penalty spot. This, combined with the positioning of the aforementioned two, has resulted in a rectangular portion of space being created in a dangerous area. Furthermore, this area is accessible because the corner is an in-swinger. QPR also have a decoy short option, thus reducing Birmingham’s presence in the box.

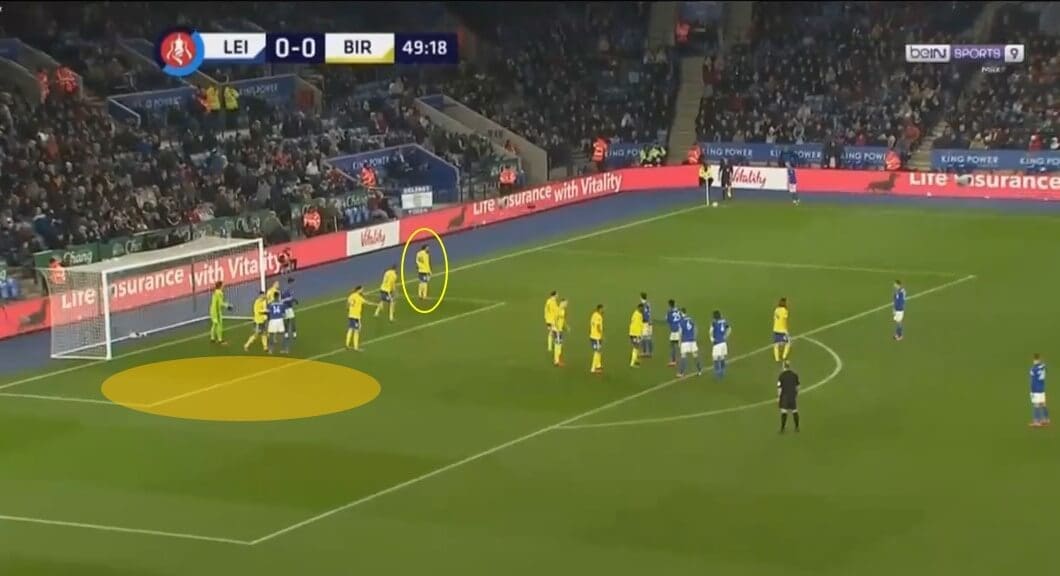

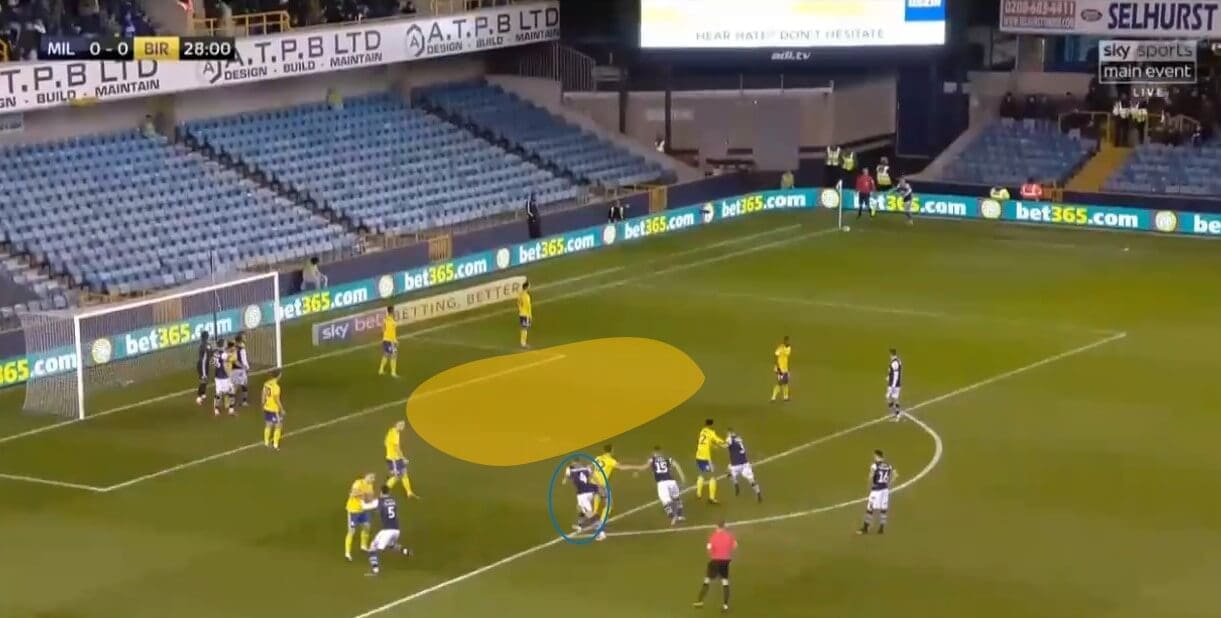

Here is a very good example of where man-marking as a concept can fall down, and how for it be successful its weaknesses need to be minimised. For example, having a continuous, underpinning structure that still provides coverage in necessary areas. Because of the Millwall players initially positioning themselves on the edge of the box – and Birmingham’s man-marking – excessive space is left unoccupied. Similar to the Leicester example, some of Birmingham’s players are in areas that don’t need to be occupied, such as at the corner of the six-yard box. Subsequently, there is now a rather large target area, in which the offensive players can dynamically move into. Moreover, the Millwall No.4 doesn’t have an obvious marker, meaning he can build up greater momentum to attack the delivery than his marked peers.

I’ll now show instances whereby the Birmingham defensive structure is much better organised and coordinated for the type of delivery and opposition positioning. Here below Swansea City are taking an in-swinging delivery. We can see four zonal markers, who have good spacing. The near-post is protected. The three behind him are evenly spaced, parallel to the goal-line, nicely stretching their coverage to the far-post – which can often be excluded. The man-markers are also not too high, reducing the space for Swansea’s attackers.

Here is another example of a better out-swinging defensive structure from the Blues. Firstly, the coverage of the near-post is better balanced – adapting to the ball’s natural trajectory. There are also three zonal markers well-spaced. The man-markers are tight on their respective forwards, which increases the difficulty of aerial duels. The structure as a whole is much more compact and centralised. The volume of players means it becomes significantly harder to achieve proper separation and a clear chance at goal.

Attacking corners

Similar to when they are defending corners Birmingham place great emphasis on sheer physicality in offensive situations. They naturally vary their routines – albeit without much invention such as Bournemouth – but generally rely on being aerially superior to succeed offensively. Perhaps then it is not a surprise that Birmingham prefers in-swinging corners, whereby they can be qualitatively superior.

This example above shows a good overview of their attacking structure. One thing connects all the targeted attackers: they begin their offensive movements from deeper areas. Having more space to work with is especially important when being man-marked. Three Birmingham players are more centrally positioned, however, there are also two Charlton defenders in their probable target area. The back-post though is less occupied and offers better body-orientation.

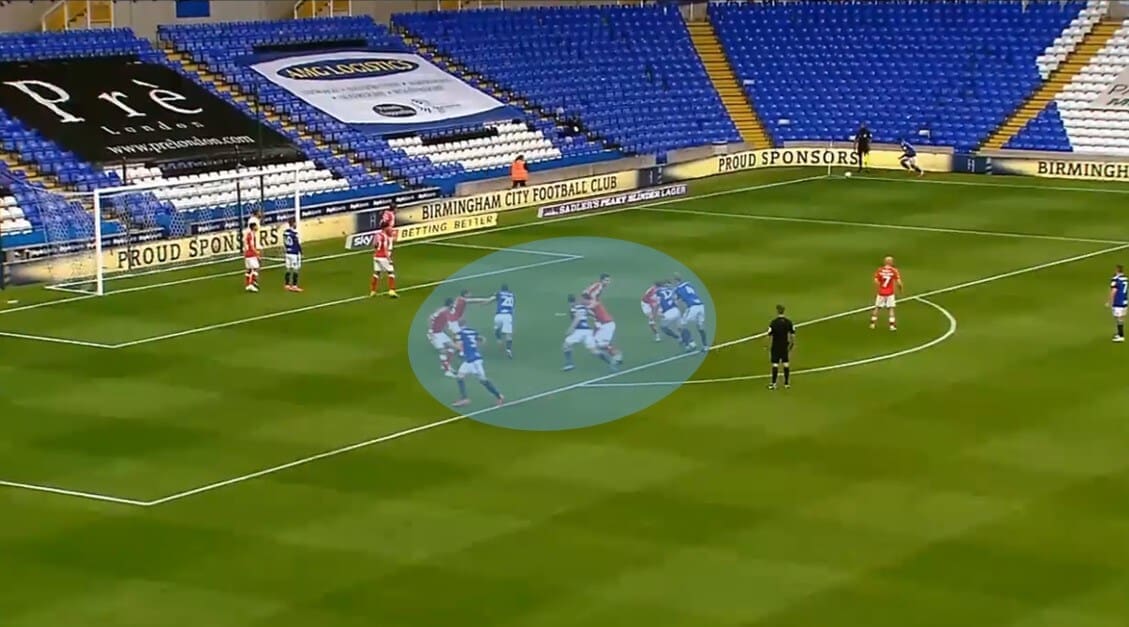

Birmingham also like to utilise the ‘train’ tactic. This consists of the offensive players grouping together before splitting in different directions, with the aim to disorientate the defence, and thus free themselves. In this instance above, five players are involved in the initial ‘train’. As a result, there can be confusion amongst the opposition about who to mark, particularly if dismarking tactics such as blockers are employed. Birmingham could look to do this more regularly with their physical squad profile suited to it well.

This is a similar example; however, it does incorporate some extra complexity. Birmingham have seemingly consciously left the far-post open to be subsequently exploited. Unlike the last example against Charlton, Kristian Pedersen executes a block to allow Lukas Jutkiewicz to move into space without pressure. But, the absence of a blocker on the goalkeeper to impede him means the likelihood of this routine being successful diminishes.

Overloading a specific area because of aerial dominance can be a simple but effective set-piece tool. It also links to the offensive principle of overloading to underload. Therefore, even if the attack isn’t successful in the first phase the space elsewhere means it could be as play progresses. We can see above that Birmingham have opted to heavily occupy the six-yard box. This method is only feasible with an in-swinging delivery. The Blues also have a player subtly blocking the Stoke City goalkeeper, preventing him from freely accessing the delivery. As I spoke about earlier the consequence of this type of positioning is that much of the rest of the penalty box is empty. Second phase attacks now have conditions more optimal for success; although a weaker rest defence is an inevitable by-product.

Again here Birmingham’s overload of the far-post is obvious. However, there is no blocker on the keeper like last time, and, Fulham have two, tall zonal markers in optimum areas. Nevertheless, the lone, unmarked Birmingham player next to the far-post is on their blindside and can be impactful. Additionally, the player at the near-post could be utilised for a cut-back in the second phase.

This final example is something different with an unusual structure. The most apparent change is where No.40 Scott Hogan is. His role is pinning back an additional Hull defender, therefore leaving the Tigers with less presence elsewhere. He can also influence play from the blindside – by moving towards the centre. The other Birmingham player near the goal-line is also horizontally stretching the Hull defensive structure. There is a relatively large amount at the far-post once more – due to it being underloaded. The reliance on players in win individual duels, however, can see these become largely unproductive.

Conclusion

In an unnoteworthy season Birmingham’s set-pieces offered an interesting side-point. It is not normal to see such a different record offensively and defensively. On the defensive side it is evident there is perhaps too much responsibility given to man-markers. Offensively, I think their squad profile is well-suited for set-pieces. We shall see what changes Karanka makes, and whether they’ll be for the better.

Comments