Marcelo Bielsa’s Leeds United are a fearsome attacking force. They currently sit on the top of the tree in the EFL Championship, in prime position for promotion to the Premier League. 56 goals scored so far is a good return but their lack of a clinical edge has been well-documented, arguably costing them promotion last season. In 37 games the Whites have notched up an xG total of 68.5, a stark difference of 12.5 compared to their actual goal return.

However, the focus of this analysis is their set-piece struggles. Naturally, with how they’re able to relentlessly attack, Bielsa’s side receive a large volume of set-pieces.

In this set-piece analysis, I will look at why they haven’t been very successful from them and the tactics behind this.

Data analysis

I’ll initially look at their statistical figures in context to the rest of the league, then the more advanced stats which imply trends within Leeds’s usage of set-pieces.

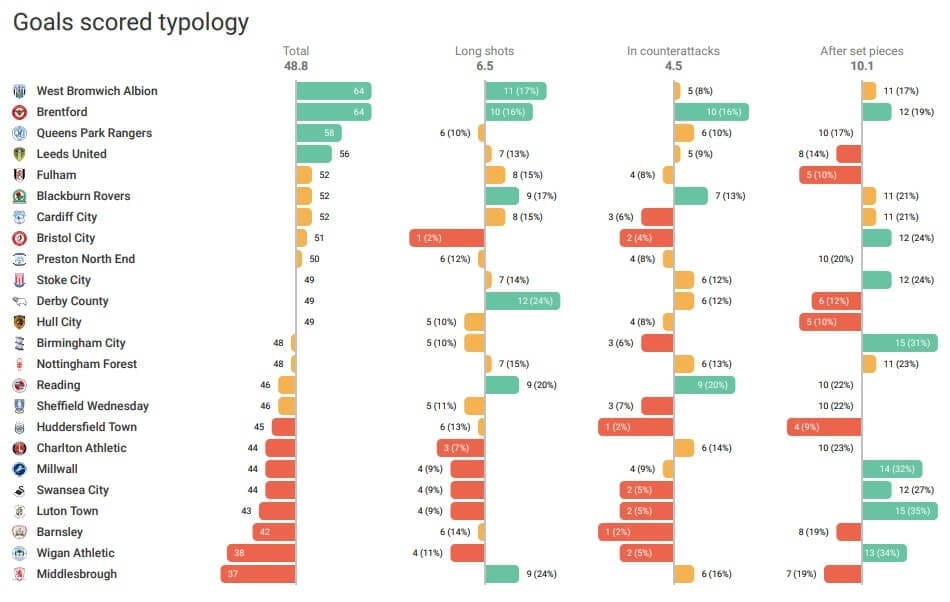

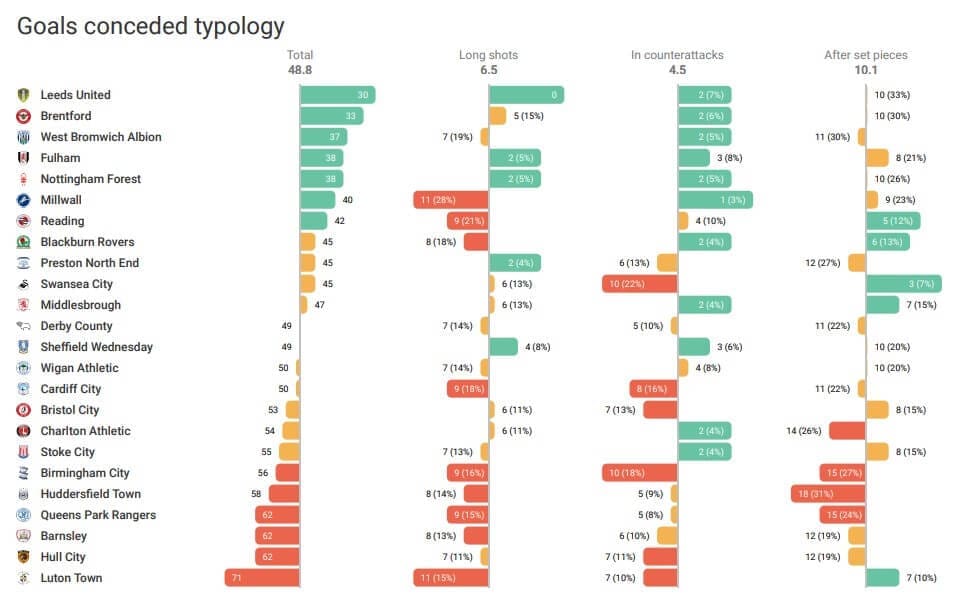

Above is a table that portrays the distribution of goals scored in the EFL Championship. 10.1 is the average of goals from set-pieces for an individual team. Leeds however, despite currently topping the table, have scored eight from such situations, not dreadful but likely not as much as they’d like. In contrast, West Brom – in second place – are superior here with 11 goals, also not outstanding but it adds up, particularly when considering these goals make up 17% of all their goals scored, whereas Leeds’ is 14%.

The next table is the same in essence, just looking at the number of goals conceded this time. Leeds perform better in this category, pretty much aligned with the average, conceding 10 goals in total. Although, because their defence in open-play is excellent, conceding 10 is the highest proportion of all goals conceded league-wide.

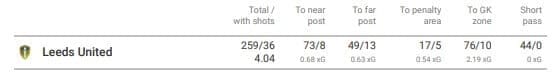

These images illustrate the specific variations in type of delivery from set-piece scenarios. Firstly, throughout the course of the season Leeds have garnered 259 opportunities – a substantial number and unsurprisingly the most in the league. Additionally, this number is 43 more than Brentford who have the second-highest total. Out of the five potential delivery areas decided by Wyscout Leeds concentrate on the near posts and GK zone, with 73 and 76 respectively. Moreover, – and as a though-provoking side-point – Leeds have taken gone short 44 times, but not one of those times has a shot ensued.

As I said there is little difference in the number of times Leeds have either chosen to delivery at the near post or to the GK zone, of course this is dependent on the quality of the delivery, therefore potentially skewing the figures, although we’ll never know. Nevertheless, the offensive effectiveness differs by quite an amount between the two. When delivering to the front-post zone Leeds have a xG per shot of 0.085. Whereas, for the GK zone, the xG per shot is 0.219, a difference of 0.134. There is a conclusion apparent to this significant difference; at the near post there is likely to be many more opposition blockers putting pressure on thus meaning the body-orientation for a shot is poor. As well as this the goalkeeper is expected to be positioned in such a way that minimises space where a goal can be scored, compared to a central location like that of the GK zone. But this also indicates that making Leeds more dangerous at the near-post is something that Bielsa and his staff may need to look at during this enforced break.

I’ll now look at the tactics Leeds currently employ at set-piece situations.

Attacking corners

As you would probably expect from a coach like Bielsa Leeds utilise a variety of complex routines, with the core aim being creating separation from markers for a clear opportunity at goal. This can either be initially emptying an area by their positioning before the corner is taken, therefore dictating where the opponent is marking or, using blockers and decoy runs to create a free man. However, these processes can be inhibited by the opposition opting for zonal marking, though a drawback of this method is that it can result in inferior body-orientation to that of the attacker.

The specific roles within Leeds’ set-pieces is an important factor. Whilst Kalvin Phillips and Jack Harrison are the primary corner-takers, they are not exclusive to either the left or right side. Mixing deliveries between in-swingers and out-swingers gives greater variability and forces the opponents to practise both during pre-match preparation. Liam Cooper (6’2”), Ben White (6’1”), Patrick Bamford (6’1”) and Luke Ayling (6’1”) are usually found centrally seeking aerial or positional superiority for themselves or conducting deliberate movements that their teammates can exploit. Some of the more technical, creative players are found on the edge of the penalty area, looking to capitalise on any disorganisation in the opposition defence upon them moving out.

One of the main objectives for Leeds is freeing up the far-post region. Via overloading the near-post they attract defenders, therefore allowing a movement to the unoccupied far-post. We can see an example like this above against Nottingham Forest. No Leeds players are situated in this deeper area, and neither are Forest players. No.17 Helder Costa is positioned in such a way where he can make a run on the blindside in anticipation of a flick-on or generally cause confusion in the goalmouth. Subsequently, Ayling’s run (No.2) to the near-post has created some separation for No.6 Cooper, who eventually hits the bar. Furthermore, Costa has indeed peeled off in case of a favourable bounce or ricochet.

Again here a large amount of space has developed at the far-post, due to a number of the Wigan players being attracted to the main block of players. This subsequently frees Ezgjan Alioski in the vacant space. Because of Alioski’s blindside movement sound, positional awareness is required from the opposition, otherwise little is needed for a superb goalscoring chance to materialise.

This next routine above is not explicitly the same but has similar principles. Ayling has dragged his marker relatively deep causing a split in the defensive structure of Bristol City. Cooper is following up on this decoy run. At the far-post three Leeds players are tussling with their markers, again in the event of the ball falling to them by whatever means.

Overloading a distinct area is a common tactic in a set-piece environment and for Leeds it is also not exclusive to the near-post zone. Here above is a situation where an unidentifiable Leeds player is in a good position at the far-post – with the necessary body-orientation for the circumstances – to potentially score, or for a cut-back to his more central teammates. What would improve this is if there were Leeds players standing closer to the goal-line, the side on which the initial corner was taken preferably. Then the player heading the ball back across has an obvious target to which the ball only them needs a slight touch to go in.

Short Corners

Leeds also adopt variation in the length of their delivery. Short corners can have several purposes. Firstly, it will naturally attract additional defenders, resulting in more space in the penalty box and thus dangerous areas. Moreover, in this second phase, confusion within the opposition defence structure can develop, allowing gaps to emerge or players to now find themselves free following the defence pushing out. This strategy is still riskier for the offensive team however – compared to the linear method of a direct cross – and necessitates precise passes and more so, movement into alternative space while maintaining good spacing. Leeds have had issues with the execution of this tactic thus far this campaign.

Much of the purpose of short corners is to create a better angle of delivery. Leeds commonly switch up the number allocated to this process, mainly trying to get a 2v1 or 3v2 overload. The image above is an attempt of the two-man version. In this instance it isn’t successful. Firstly, the two Middlesbrough players have got out quickly to apply pressure almost instantaneously once Harrison has received possession back from Costa. To combat this Costa should be closer, reducing the distance the ball needs to travel there and back, whilst providing depth. Moreover, the left-footed Man City loanee initially receives on the weaker right-foot, and therefore needs to adjust for a dribble and potential cross. This routine has parallels with what Pep Guardiola at Manchester City, but the deliverer there is nearly always right-footed, allowing for an in-swinger. This is preferential because the cross can be first-time instead of having to wait for it to come across a left-footer’s body like in this case.

The next exemplar is executed much better, this time involving three Leeds players. Harrison first passes to Matheusz Klich, thus encouraging Boro players to engage. Them doing this allows greater space for Costa – who is in a deeper position in the half-space – after receiving off Klich. There is a corridor prominent for Costa to delivery into but his cross is poor. Sometimes Leeds may get the movements part right but their actual technical ability lets them down. And because the Leeds players will anticipate and understand this routine it is likely they would have superior body-orientation to attack the cross if it had been a better delivery.

That drill is simple and potentially very effective but perhaps predictable. Here above more complexity is introduced rather than essentially just two sideways passes. The first action comprises of Klich arriving from deep – beginning close to the centre-circle – to offer a safe, short pass. Klich then proceeds to set the ball back for Harrison, and compared to the earlier example shown, it is on his stronger left-foot, allowing for a in-swinger which can cause havoc for a back-tracking Bristol City defence.

Defending corners

Like many teams, Leeds and Bielsa employ both zonal and man-marking, albeit with Leeds utilising man slightly more. There are mainly four aerially proficient defenders tight on the dangermen for the opposition, usually positioned close to the penalty spot. Bamford is located in the near-post region, responsible for clearing poor deliveries and preventing the ball progressing into a central area. Pablo Hernández can be commonly found attempting to disturb or block the original corner on the edge of the area. I’m not sure this is entirely productive as it just deprives Leeds of another player in the box. For their structure to work much hinges on the trio or quartet man-marking whose roles are to be dominant aerially and disrupt attacking moves. Man-marking as a style is prone to manipulation via actions such as blocking which can release a ‘free man’ for example.

Above is the general formation when defending corners. The cluster of players around the penalty spot is visible, as is Bamford and Hernández. Additionally, there is a group around the goalkeeper, providing coverage in this dangerous, central zone. It is worth noting that this is an in-swinging delivery, therefore occupation here is necessary. Although, Bamford has a duty in stopping the ball’s path, plus you’d expect the keeper to make an impact defensively if Bamford hasn’t already removed the danger.

This portrays the potential problems with a man-marking approach. Wigan have situated themselves in a variety of positions, but have emptied the area around the penalty area. Due to their positioning dictating where Leeds’ markers are an underload has developed. With zonal marking this doesn’t happen; you can have optimal coverage everywhere. In addition to this the Latics have brought someone short, resulting in another Leeds player having to follow him in order to prevent an overload situation in light of Hernández being there already. A well-executed cross combined with an attacker getting goal-side can present an easy and simple opportunity here.

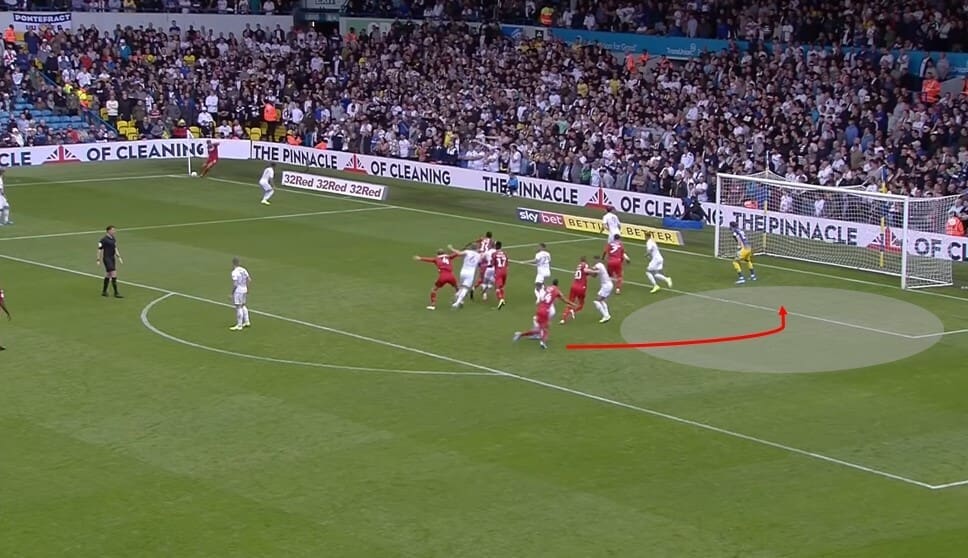

I talked earlier about Leeds’ preference to underload and then exploit the far-post; leaving the far-post open can be an issue for them defensively as well. In the above image we can how that space is unoccupied. A run is made around the back of the block into this aforementioned space and along with a kind ricochet, they eventually bundle the ball into the net.

Conclusion

This tactical analysis has identified some trends in Leeds United’s corners and analysed some of their strengths and weaknesses, which I’m sure Bielsa will be doing himself. The Whites have good ideas, particularly offensively, but sometimes their individual technical skill means they are unsuccessful. However, I believe the defensive structure does have some mild flaws that can be exploited by a clever team through some intricate routines.

Comments