On April 24th Luton Town announced that after just a year in charge Graeme Jones had been relinquished of his duties. It was an entirely rational decision with the Hatters six points off safety before football was suspended. Much of their problems have owed to a weak defence. 71 goals conceded – a league high – is a very lofty amount for 37 games played. Jones’ inability to make Luton more resolute is one of the primary reasons for his departure.

But for set-pieces, oddly, their record has been one of the best in the EFL Championship. Both offensively and defensively I must add as well. While my previous set-piece analysis looked at Leeds United and their under-performance from set-pieces here I shall see why, despite their lowly position in the table, Luton are effectively the role-reversal of Leeds.

This tactical analysis will look at the reasons for Luton’s success from set-pieces and the tactics behind them.

Data Analysis

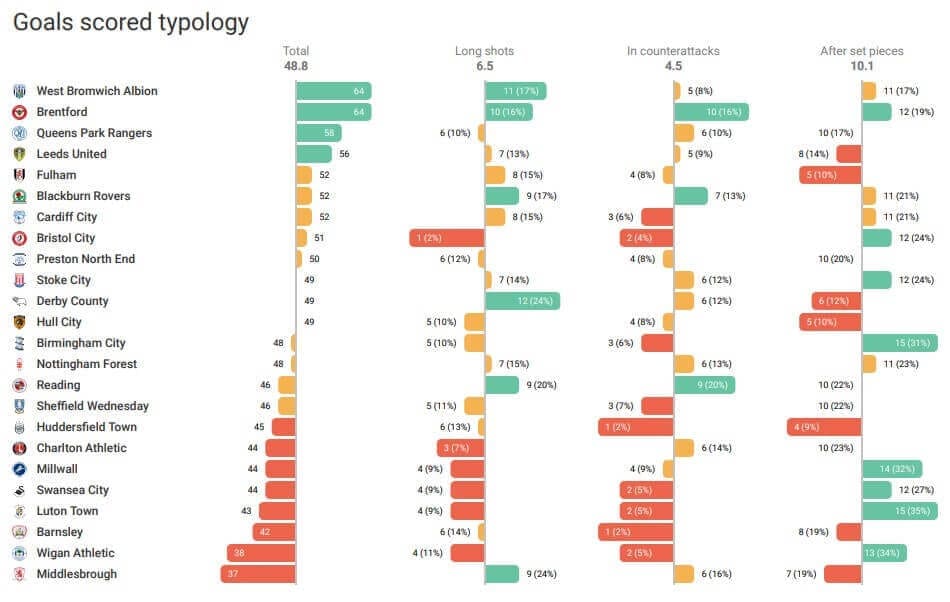

This table above indicates the variety of types of goals scored and can portray a team’s dependency on one method. In an attacking sense, Luton have scored the joint-most in the league with 15 – tied with Birmingham. These 15 goals make up 35% of all goals they’ve scored, which is also the highest proportion in the league.

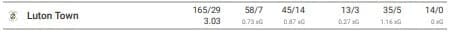

Luton have had 165 offensive corner situations this campaign. Therefore, they have had a success rate of 9.09% in these scenarios – rather excellent. However, the xG implies this success may not be sustainable in the long run at all. Out of these 165 attempts, 3.03 xG has been generated, an over-performance of 11.97 compared to their actual goals scored. For context, the highest xG total in the Championship is from Millwall, who have registered 7.08 and scored 14.

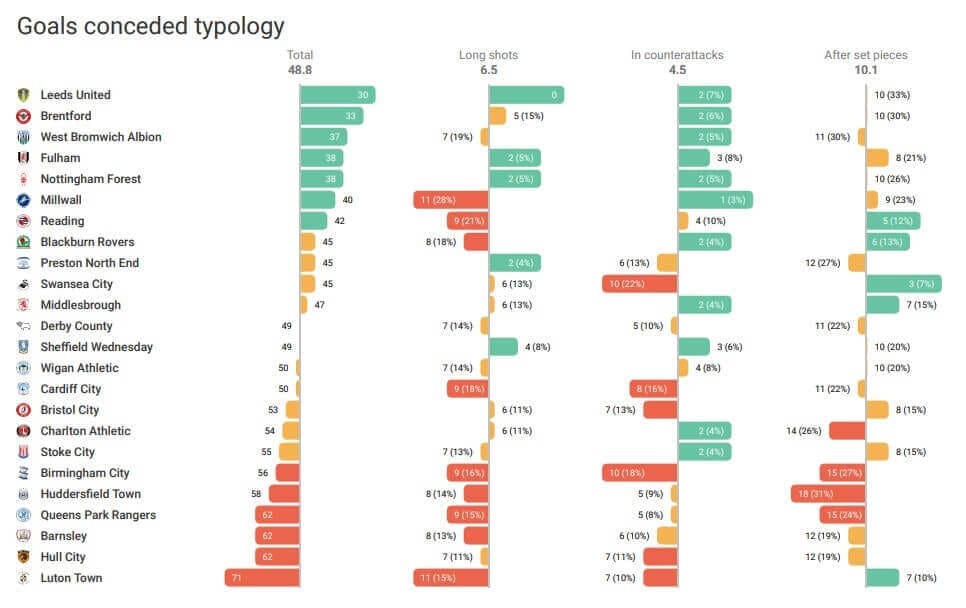

Compared to their defence in open-play, their defending from corners is much improved. Pretty significantly, they’ve conceded less than the league average, a welcome statistic considering the major defensive issues they have contended with. The seven goals ceded from set-pieces also makes up 10% of all their goals conceded, though that is because of the vast concessions that have occurred in open-play.

The near-post and far-post are the locations where their deliveries are focused the most. Specifically, the near-post has experienced 13 more. Nonetheless, there have been differences in how worthwhile the variations in delivery point have been. Despite having the highest proportion of deliveries at the near-post Luton have only registered 0.73 xG, this figure arises from seven shots, meaning an xG per shot of 0.104. In contrast, at the far-post, the delivery to shot ratio is superior, with it being 45:14. Having more shooting chances from at the far-post compared to near-post is likely to be due to under-hit corners skewing the near-post numbers, In addition to better body-orientation that is usually included with a far-post delivery.

Offensive Corners

The downfall of a defensive set-up that incorporates zonal-marking is its association with ceding dominant body-orientation. Whilst it allows for optimal coverage of all necessary space, plus not being dictated by what the attackers positioning is, the defenders can be put at a disadvantage. This is because by initially beginning their offensive movements in deeper areas the attacking players can gain greater momentum, thus potentially giving them qualitative and/or positional superiority. This search for superiority is a key aim of Luton’s tactics at offensive corners.

In Luton’s case, this occurs by congesting an initial space, with the purpose to unsettle the opposition defensive structure, and to ensure there is a sense of unpredictability in the runs made by the players in this attacking block.

Here below we can see that there are four Luton players in a cluster, such a scenario provides conditions possible for the usage of techniques that can create separation from markers. Subsequently, two of them act as blockers, disrupting the Birmingham defenders from accessing the free man. Additionally, James Collins and James Bree (No. 26 and 19) have pulled Birmingham markers deep around the near-post. Therefore, space has developed in a central area where there would be a high probability of scoring if there had been an accurate delivery.

In this instance below a group has once more formed around the penalty spot. The use of blockers can again be utilised to release more aerially dominant players, such as centre-back Matthew Pearson. Furthermore, in this example, Fulham are indeed partly structured zonally. Because this is an in-swinging cross by taker Luke Berry the trajectory will be better suited to the attackers, as the ball will begin away from the defenders, making a defensive, cleared header more complicated.

This next example portrays how there is a gap in the Stoke defensive structure at the near-post region, due to them opting to man-mark the deeper Luton players. Although there is a defender situated close to this area, the corner-taker Alan Sheehan is left-footed therefore making it more difficult for the zonal marker here to interrupt of the delivery. Also, as the attackers will have prior knowledge of this tactic they will be able to anticipate it and hopefully achieve positional superiority by starting their run earlier.

On occasions, short corners have be utilised so far this season. Because this enforces opposition defenders to leave the penalty area to prevent a simple overload, additional space is created in the area. For weaker teams, this may be preferential as it would result in deliveries not having to be so specific to a certain area to be successful. In the majority of cases, short corners will be executed as to move the ball away from goal to then cross with a better relative overview of the pitch. In the illustration below however Luton exploit a lack of awareness from Stoke City to get to the by-line. The original corner-taker Harry Cornick plays a 1-2 with Izzy Brown to bypass an unaware Tom Ince and free himself. Consequently, Cornick can cross closer to the goal than he would from a more regular method. This subsequently provides a greater threat as the ball has less distance to travel.

Even so, Luton do sometimes opt to go into deeper areas – to get an improved angle of delivery, whereby they can access an increased amount of space. We can see this play out below. Brown plays a short pass to Cornick – this has drawn out two Wigan players. Cornick continues the sequence by moving possession onto Pelly Ruddock Mpanzu who is positioned much deeper, thus increasing the crossing distance. This is a relatively inventive routine but does have some flaws. Those present in the box should ideally be making runs to find space or disturb Wigan’s structure. For example, peeling off at the far-post, so a cut-back would be feasible. Also, Mpanzu being right-footed means there is a delay before he can cross the ball to the best of his ability. This delay has allowed Gavin Massey to put pressure upon Mpanzu, thus reducing the cross’s accuracy and effectiveness.

Defending Corners

Luton employ zonal marking in the immediate area around the goalmouth, a common strategy. This ensures there is coverage in the place where there is the highest probability of scoring in. Elsewhere, the players who are of greatest aerial threat are man-marked to prevent them from attacking the ball without disruption.

The general structure is visible above. The player at the near-post is to clear the delivery if executed poorly, therefore stopping it entering the central portion of the goal where little would be needed for a goal to occur. We can also see another defender positioned well at an alternate height. Of course, you need to factor in the goalkeeper’s capabilities to avoid danger ensuing. In this incidence three players are marking attackers directly; with this approach, they need to be awake to offensive routines that seek to free an attacker. This may then require a zonal marker to step in, hence needing effective communication and understanding. There is also a player situated (No.4) so he is blocking a pass to the edge of the box.

Here is a similar structure, adapted for an out-swinging delivery however. This alteration is entirely necessary because the ball trajectory will be directed towards different areas, so the defence then needs to respond appropriately, which Luton have done here. There is less concentration upon the goalmouth, with players instead positioned in a diagonal line moving away from goal. This again maintains optimum coverage relevant to the expected type of delivery. The six-yard box should be marshalled by Simon Sluga, the Luton keeper. The trio man-marking are evident once more, their tasks will be made easier by the four zonally marking who can directly attack the ball to remove the danger.

This next example above depicts the structure during a short-corner. One player has been forced to go out, and there is another ready to press if required. The rest of the structure is rather alike with little differentiation though. However, these players being removed from the central region does result in reduced occupation and optimal coverage becoming more difficult. Indeed, there is a gap apparent that is accessible, particularly prevalent because the corner-taker is right-footed. This highlights how spacing is so imperative for a compact set-up whatever the circumstances.

Conclusion

This analysis has looked at Luton’s corners in particular under the now unemployed Jones. On Thursday 28th May 2020 the Hatters announced the return of Nathan Jones as manager after he failed to get Stoke City anywhere near Premier League promotion contention. He has an extremely tough job to prevent Luton getting relegated upon the resumption of football. Although set-pieces was a key strength of Luton previously there is still a need to shift the offensive dependency away from them whilst maintaining their defensive solidity, such as Liverpool.

Comments