It is one of the oddities of football that sometimes you can become a victim of your own success. This was the case for Manchester City and Pep Guardiola as they faced Chelsea in the EFL Cup Final. A matter of weeks ago we saw City comfortably overcome their opponents in this match 6-0 when they met in the Premier League. This demolition saw the narrative in the lead up to this match firmly suggest that City would comfortably ease past Chelsea in order to claim the first piece of silverware this season.

What followed was a match full of incident and controversy, but not full of goals. The final was settled on a penalty shoot-out with England international Raheem Sterling scoring the winning goal.

While the histrionics surrounding the refusal of the Chelsea goalkeeper Kepa Arrizabalaga to accept being substituted and the subsequent behaviour of coach Maurizio Sarri on the sidelines were intriguing, they are not the base of this article. Instead, we will examine the tactical concepts within the match and look closely at the way Manchester City looked to break through the Chelsea block.

Lineups

When the team sheets were announced there was little in the way of initial controversy. You could argue that the decision by Chelsea and Sarri to include Pedro on the right of the attack and Eden Hazard as the central player, at the expense of Gonzalo Higuain, was a surprise.

Manchester City were aligned in their normal 4-3-3 structure with the Ukranian utility player Oleksandr Zinchenko at left-back.

City build-up

So, how did City go from beating Chelsea 6-0 a few weeks ago to struggling to break them down in this final? Before we look closely at the systems and struggles of City we have to acknowledge that Chelsea were hugely improved. Their defensive block was deep and compact throughout the game and although they never impressed in the attacking phase they were difficult to break down.

This led to a few different approaches from City when they were looking to attack and all of these were predicated on trying to break through the deep block put in place by Chelsea. Indeed, this match provided an interesting case study given that we are used to seeing City play incisively through the thirds in order to create chances in and around the opposition penalty area.

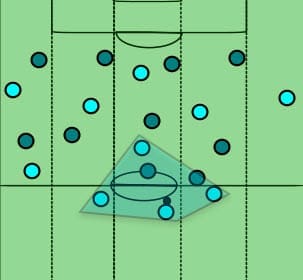

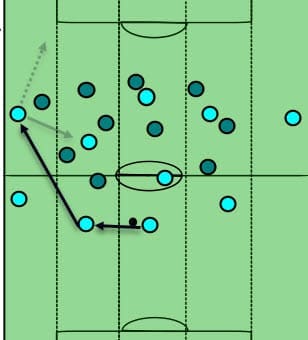

With the shape in build-up during the early stages, we saw City form a diamond of sorts at the base of their attack. Kyle Walker, at right back, would remain narrow and on a low line in order to offer the option. Aymeric Laporte and Nicolas Otamendi also stayed deep while Fernandinho, in his normal six role, was the tip of the diamond.

This allowed City to progress the ball comfortably in the first phase of their attacking model. The issues came further up as they then faced a very resilient defensive block.

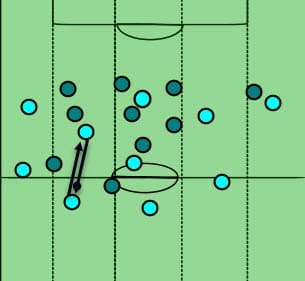

In order to attract the Chelsea defensive player to break from their defensive block, we saw the City defenders look to dribble forward into the Chelsea half of the field. As they pushed forward the hope would be that they would attract a defensive player from Chelsea out to engage with the ball. This would then, in turn, create space in behind the pressing player that would allow City to play passes to a more advanced platform.

As the first half progressed, however, we saw Chelsea content to sit deeper and allow the City defenders to dribble to a point. This saw City turn to another form of passing in order to create space further forward.

When is a pass not a pass?

One of the biggest criticisms levelled at Guardiola teams is that they sometimes appear to pass just for the sake of passing. This is, of course, somewhat missing the point. The short five-yard passes that we see City play, and then play back again, are designed to continually apply stress to the opposing defensive players. Every short pass forces the other side to adjust their position and to concentrate on the possible new threat.

Eventually, these passes will force a lapse in concentration from the opposition and this will, in turn, create an opportunity for a vertical pass to be played through the lines.

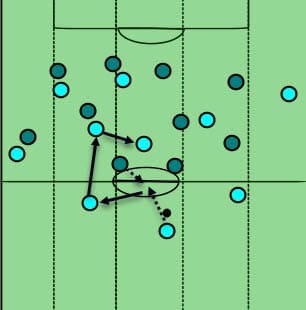

In this example, the pass is initially made out to Zinchenko in the left-back position before being bounced straight back to Laporte. As the first pass is made the Chelsea block has to shift further across to their left. The idea behind this passing combination is that the Chelsea block will try to shift over. As the ball goes back to Laporte, the Chelsea block would then have to readjust. If they do so slowly then vertical passing lanes could become apparent quickly.

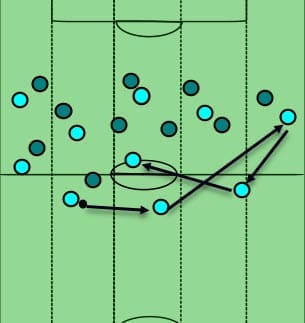

City were able to use the same passing combinations vertically in order to provoke Chelsea to create spaces into the final third. In this example, we see Laporte play the vertical pass into Ilkay Gundogan, who is playing as one of the two eights, before once again receiving the ball back. Again, the aim is for Chelsea to break from their defensive block in order to create space.

It was a clear plan for Chelsea, however, to remain extremely compact and disciplined defensively. They worked tirelessly in order to shift their defensive block either vertically or horizontally to prevent City from playing into their two eights who normally operate in the half-spaces and provide a constant danger. This led to City changing their approach and trying to access the wide areas.

City look to attack in wide areas

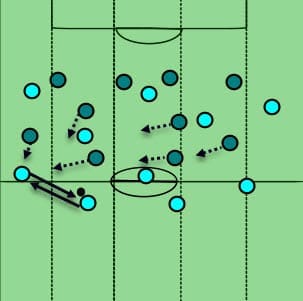

One of the most common approaches we see from City under Guardiola when they approach the ball sees them play into the eights in the half-spaces before bouncing the ball wide. In this match given the defensive organisation of Chelsea we saw City look to find the pass into the wide areas without first accessing the half-spaces.

With Raheem Sterling initially playing on the left and Bernardo Silva operating on the right side we saw City, as normal, hold the flanks with their wide players. Here, we see the ball being played first of all to Laporte before he bypasses the option of the full-back and the central players to play more directly into the wide areas.

In these positions, we tend to see the wide forward use one of two options. Either he will play back inside to combine with the advanced midfielders in the half-space or he will immediately look to engage and attack the defensive player on the outside one-on-one. As we have already seen though, there was no space to play back inside. As such, the Chelsea defenders were prepared for the attack down the wide areas.

The positioning and discipline of the Chelsea defensive block saw a series of passing sequences similar to the one shown above. Even when the pass was played into the wide areas the lack of space or options either centrally or in advanced areas saw the ball simply recycled backwards.

Throughout this match, Chelsea seemed intent on preventing City from finding space in the final third. This was a clear part of the game model from the Chelsea coach Maurizio Sarri as they made a conscious choice that detracted from their ability in the attacking phase.

Conclusion

Football is of course a game of fine margins and losing the match in a penalty shoot out will hurt for Chelsea fans. What was perhaps the most interesting aspect of this match was that for the first time Sarri showed a plan B in a tactical sense. His willingness to adapt in order to negate the threat of the opposition showed a different side to the Italian coach. Whether that will be enough to see him keep the job at Chelsea, however, remains to be seen.

If you love tactical analysis, then you’ll love the digital magazines from totalfootballanalysis.com – a guaranteed 100+ pages of pure tactical analysis covering topics from the Premier League, Serie A, La Liga, Bundesliga and many, many more. Buy your copy of the February issue for just ₤4.99 here, or even better sign up for a ₤50 annual membership (12 monthly issues plus the annual review) right here.

Comments