England were undoubtedly one of the major tournament favourites entering UEFA Euro 2024, with Harry Kane finishing the season as the German Bundesliga’s top scorer after his first season with FC Bayern on 36 league goals, Jude Bellingham finishing the 2023/24 club campaign as a key player for the UEFA Champions League winners and Phil Foden enjoying arguably his best individual campaign for Manchester City as he helped his side win a fourth straight Premier League title to name a few of the stars England fans will have been salivating at seeing play together for their country this summer.

However, those fans will have been left quite underwhelmed after the Three Lions’ first two games of the Euros resulted in performances that were far from convincing in contrast to the likes of Germany and Spain, who have started the tournament in fierce form.

Gareth Southgate has thus far failed to get the best out of any of his key players. In terms of tactics, a lot of questions have been raised as it pertains to his decisions in midfield, and if the selections look dubious on paper, their performances on the pitch have done little to inspire confidence in the manager’s choices; England’s play has looked very disjointed and massively lacked cohesion for the most part.

This tactical analysis piece, a team-focused scout report, aims to pinpoint exactly what England’s main issues are and suggest what they must do to improve. If they could conceivably turn things around and improve their performance levels, they could realistically challenge the likes of Spain and Germany for Euros glory this summer.

Too many players dropping deep

As the title of this section suggests, one of England’s main issues has been the tendency of too many of their players to drop deep, leaving nobody in positions to receive progressive passes ahead.

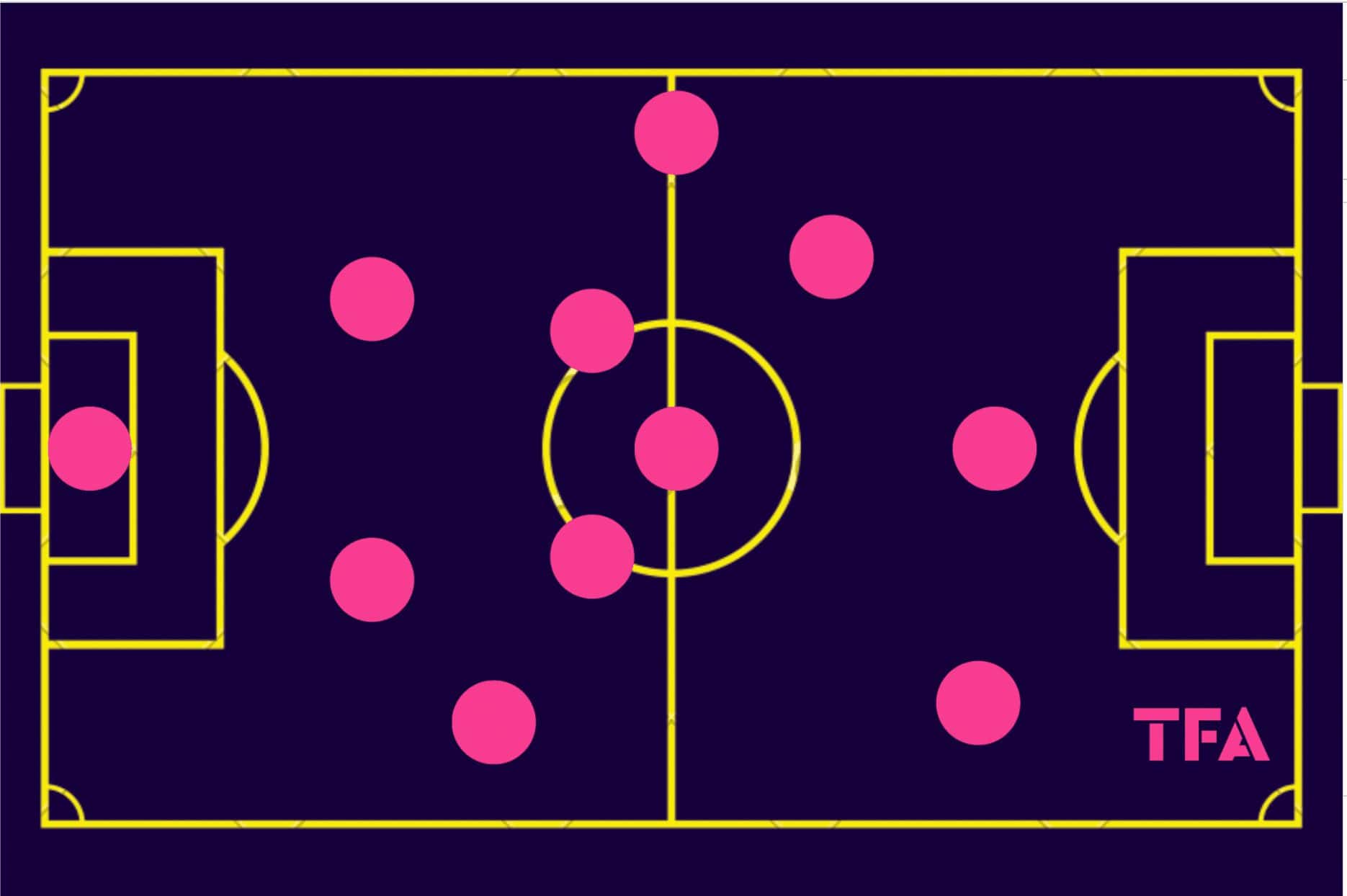

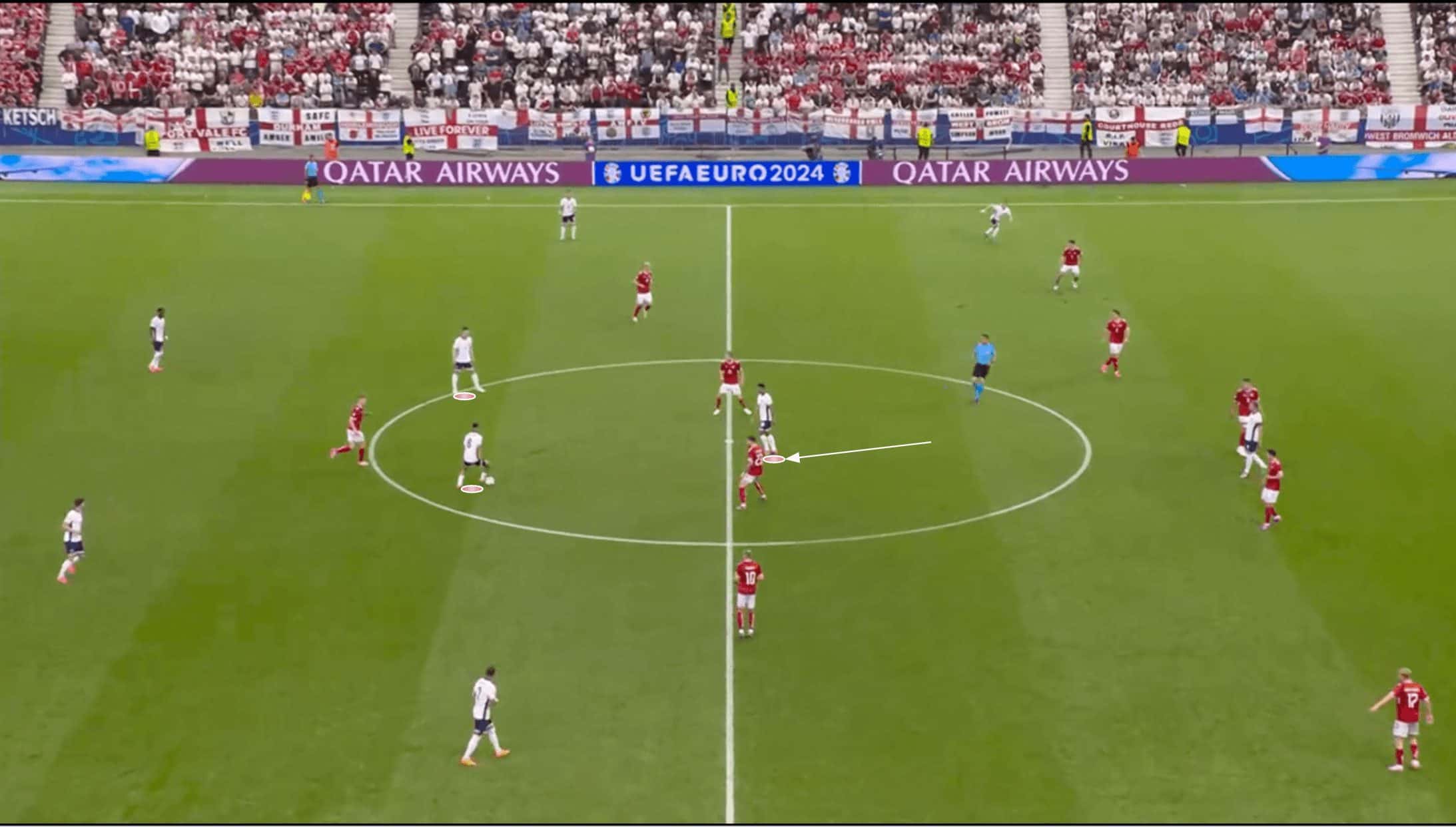

Firstly, a look at figure 1 roughly outlines how England have set up, playing from left to right, in possession thus far in the Euros.

Trent Alexander-Arnold has been deployed to the right of Declan Rice in the double-pivot, with Jude Bellingham as the ‘10’ in between Phil Foden (left), Bukayo Saka (right) and Harry Kane just ahead in the centre-forward position.

The profiles in England’s midfield have not matched up well so far in this tournament, with Alexander-Arnold often wanting to play longer balls while those positioned next to him come short to receive to feet, Bellingham drifting all around the pitch with the other players failing to react and rotate with him leaving chronic gaps in England’s midfield during the attacking phases and Kane becoming isolated in the centre-forward position — not at all playing to his strengths and hamstringing the cohesion in their attack further.

So, let’s get into our analysis of these potentially fatal issues for England’s Euros hopes.

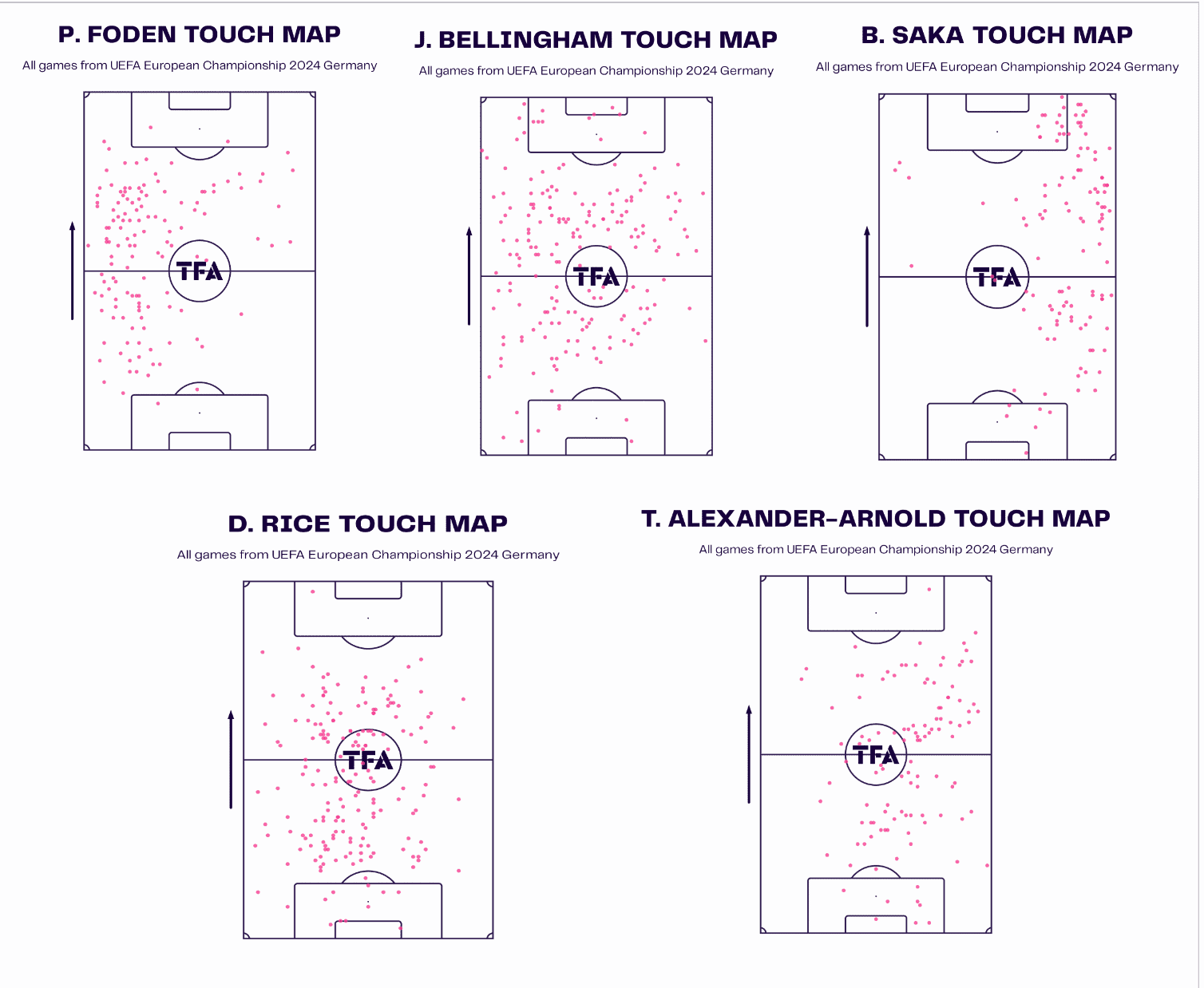

We have the touch maps of each starting member of England’s midfield from their two Euros games of the 2024 campaign so far.

This gives us an even greater idea of their midfield dynamics and how they’ve shaped up, but a key point to note when looking at this map is how there have been very few touches from anyone in zone 14, just behind the ‘D’ of the opposition’s penalty box.

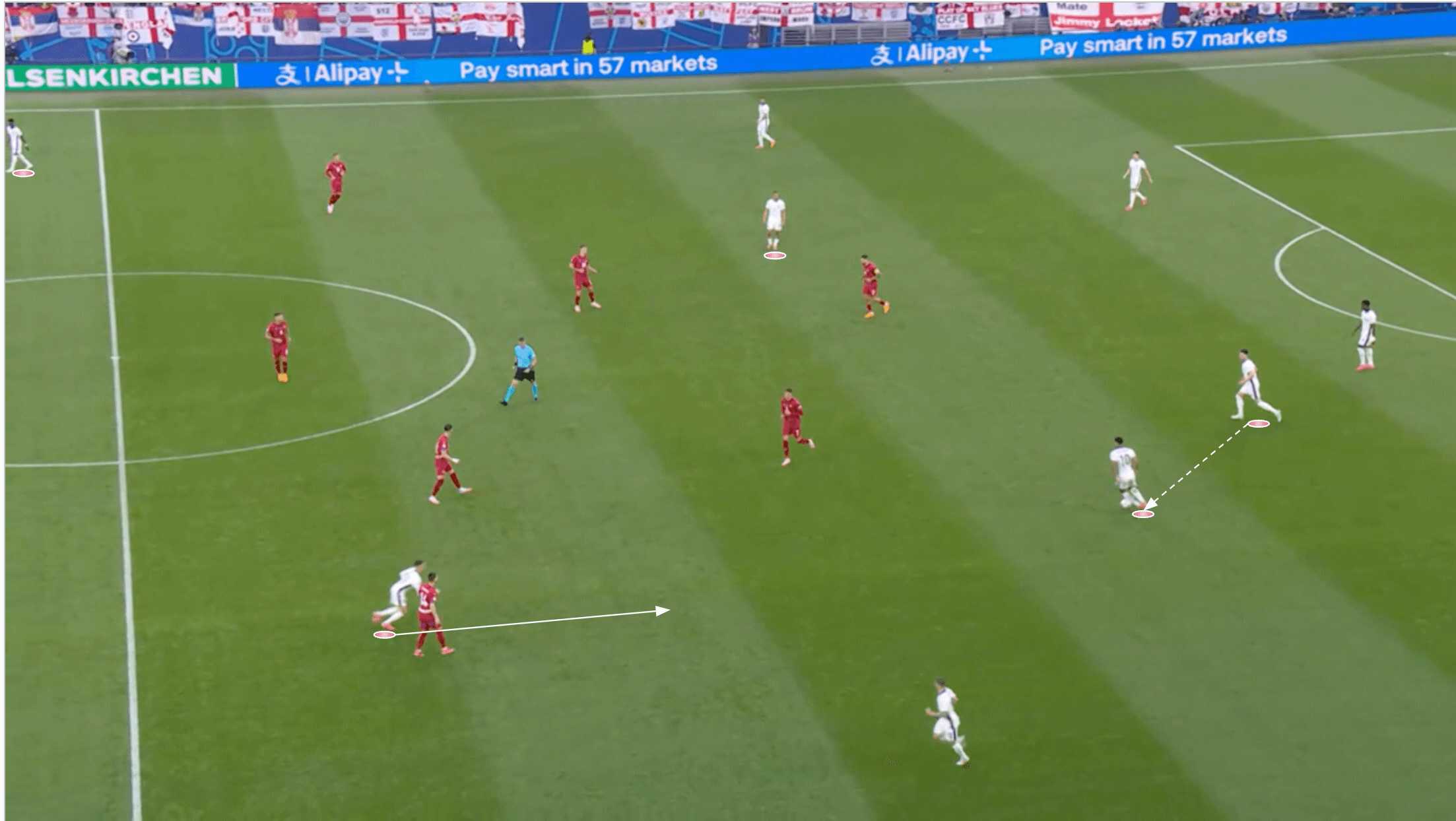

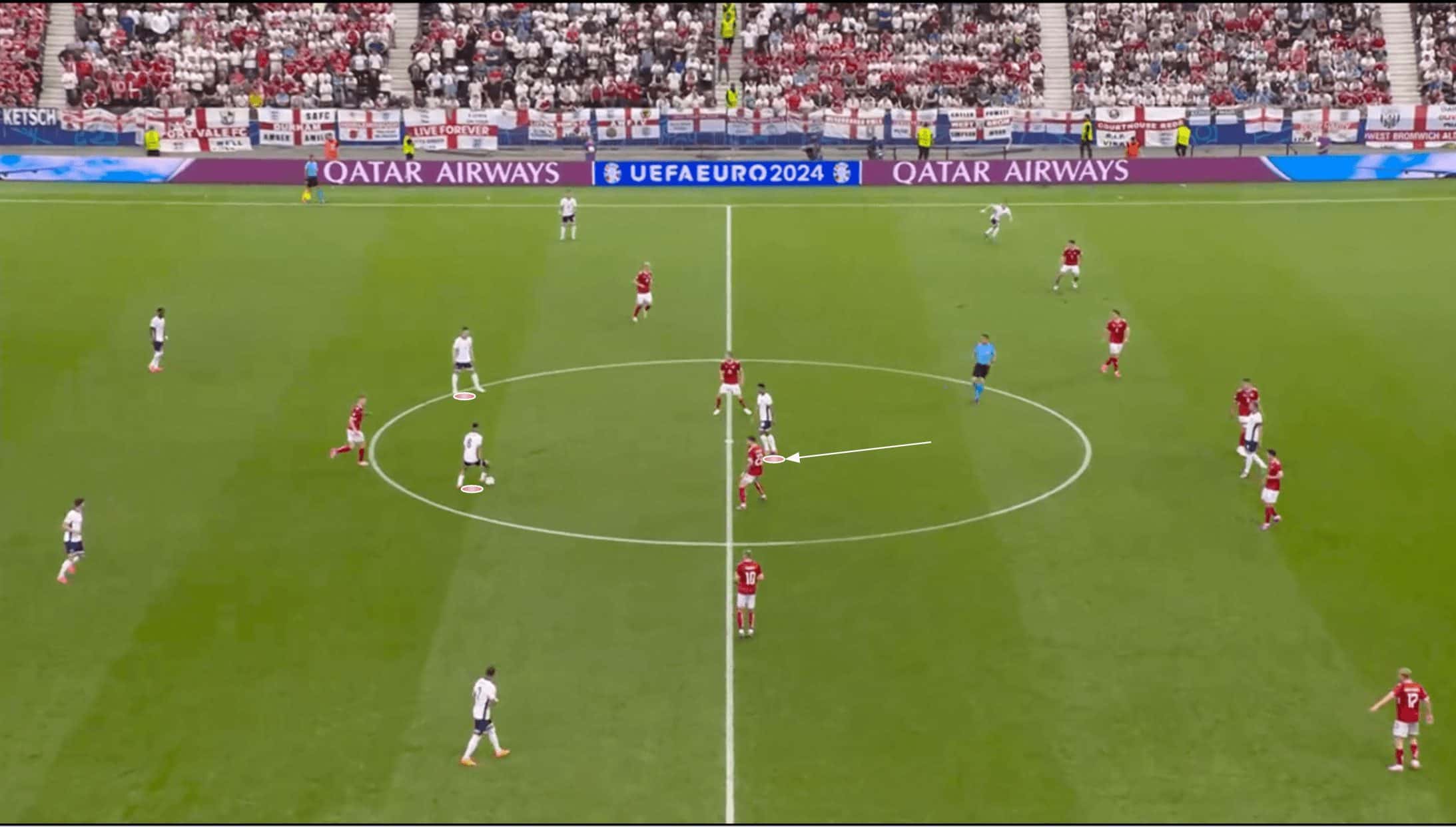

Figures 3 and 4 show one major reason why this has occurred—a couple of passages of play from England’s second game of the group versus Denmark, which exemplify a critical problem in England’s Euros campaign.

Here, we find Bellingham in possession deep on the left, with Foden currently dropping into the same channel. The Real Madrid man has just received the ball short from Rice while Alexander-Arnold remains in his right-sided position, in no area to receive or aid the team’s progression in any way.

Bellingham is given the freedom to drift around in this system, but if that’s the case, others like Foden or Alexander-Arnol must react to him and rotate into the more central ‘10’ position. Otherwise, England ends up in the situation we see here, where they’ve got eight bodies inside their own half arranged in a semi-circle, giving the opposition complete control of the centre.

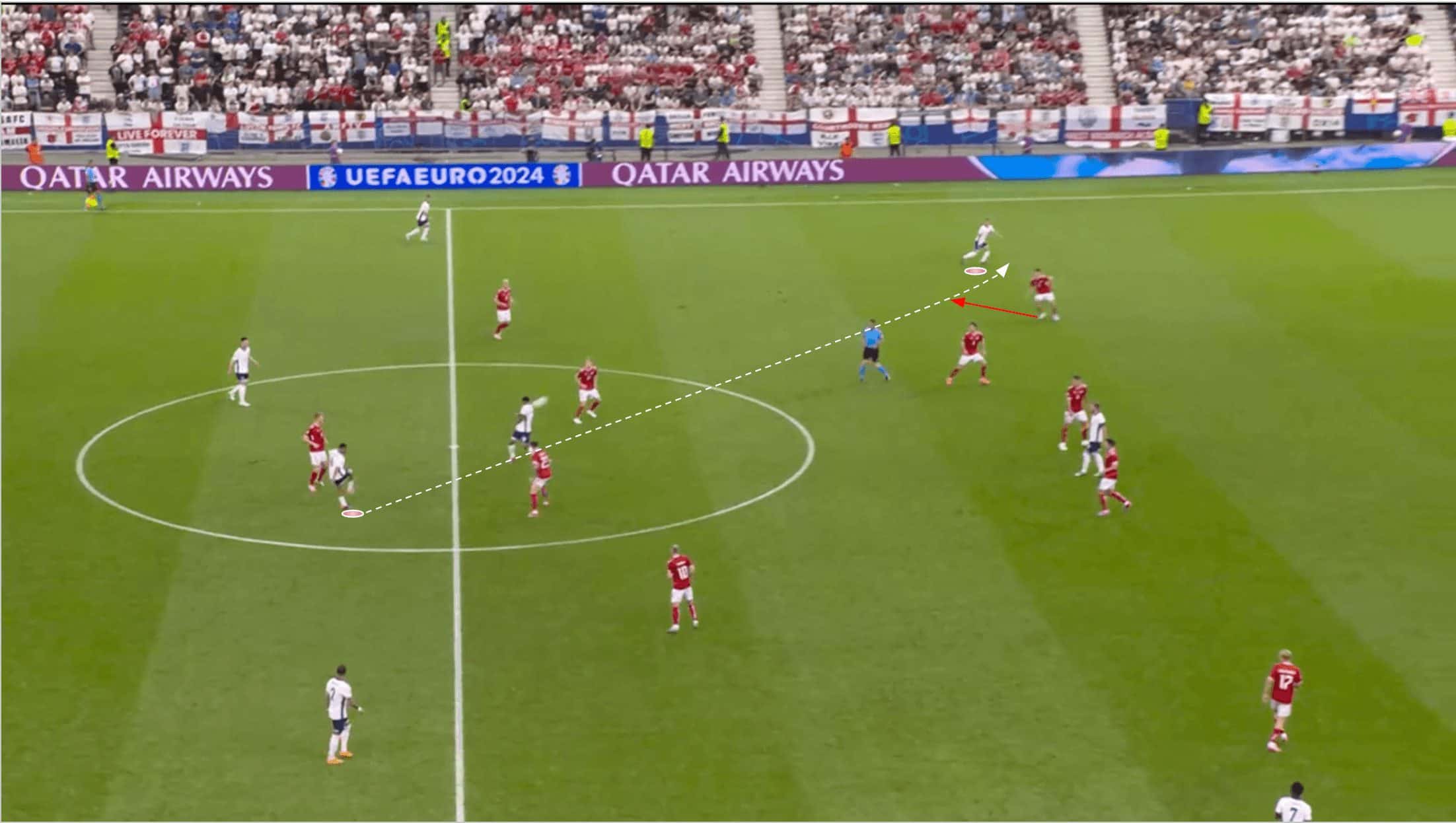

The same occurs again in figure 4, though Alexander-Arnold does start to move into a potentially useful position by the end of the passage of play; still, though, the amount of Danish bodies around him and the slow nature of his movement makes the option of passing to him quite unappealing.

These types of plays have been far too common for England in the Euros thus far. They have resulted in lengthy periods of possession with tonnes of short passes and no penetration, making England seem sluggish and non-threatening on the ball.

If they want to add more threat, they’ll have to up the tempo of their game by keeping more bodies together in more advanced central areas, creating more positional rotations and cohesion in their movement in the middle of the park, occupying the zones that will really threaten the opponent.

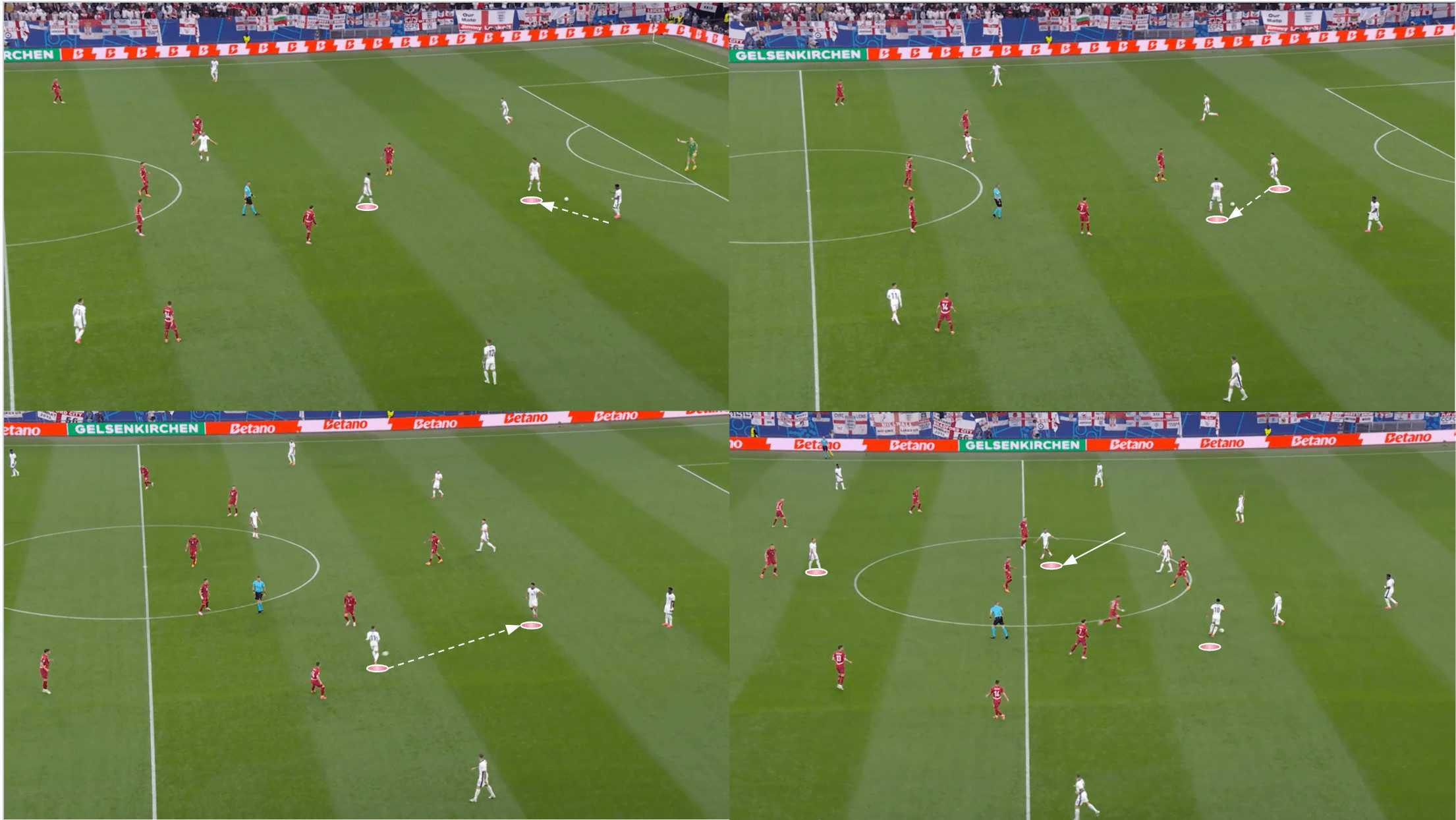

Jude Bellingham is a world class talent, there’s no doubting that. Still, a lot of the time, he’s given his midfield partners poor options at the Euros; look no further than figures 5 and 6 for evidence of that.

Far too often, he’s positioned himself smack bang in front of the double-pivot, leaving the space between the lines unoccupied. This makes him easy for the opponents to mark while also making him an unattractive passing option for the double-pivot.

At times, Rice has still taken the short option to Bellingham, but this leads to lengthy passages of short passes inside their own half that lead nowhere.

Alexander-Arnold has turned down this short ball more often but has also not had much luck with his longer passes, as we see when we move into figure 6.

The ball is played long to Foden, who’s attempting to provide depth and width via a run in behind on the left. The idea here is decent, but Alexander-Arnold’s ball is intercepted by the Danish right-back, who reads the play well.

Note how Bellingham has to flinch and dodge Alexander-Arnold’s pass, highlighting the lack of cohesion in England’s midfield — the ‘10’ wants to drop off and receive the ball to feet while the profile of Alexander-Arnold is one of a player who loves to show off his passing range, connecting with players positioned further away like Foden here.

Bellingham’s movement essentially makes him a training dummy for Alexander-Arnold and more of a hindrance than a help. He would have been far better off dropping back a few yards in figure 5 and attempting to receive from the Liverpool player in between the lines, in a position where he could potentially link up with Kane and find a combination to get in behind.

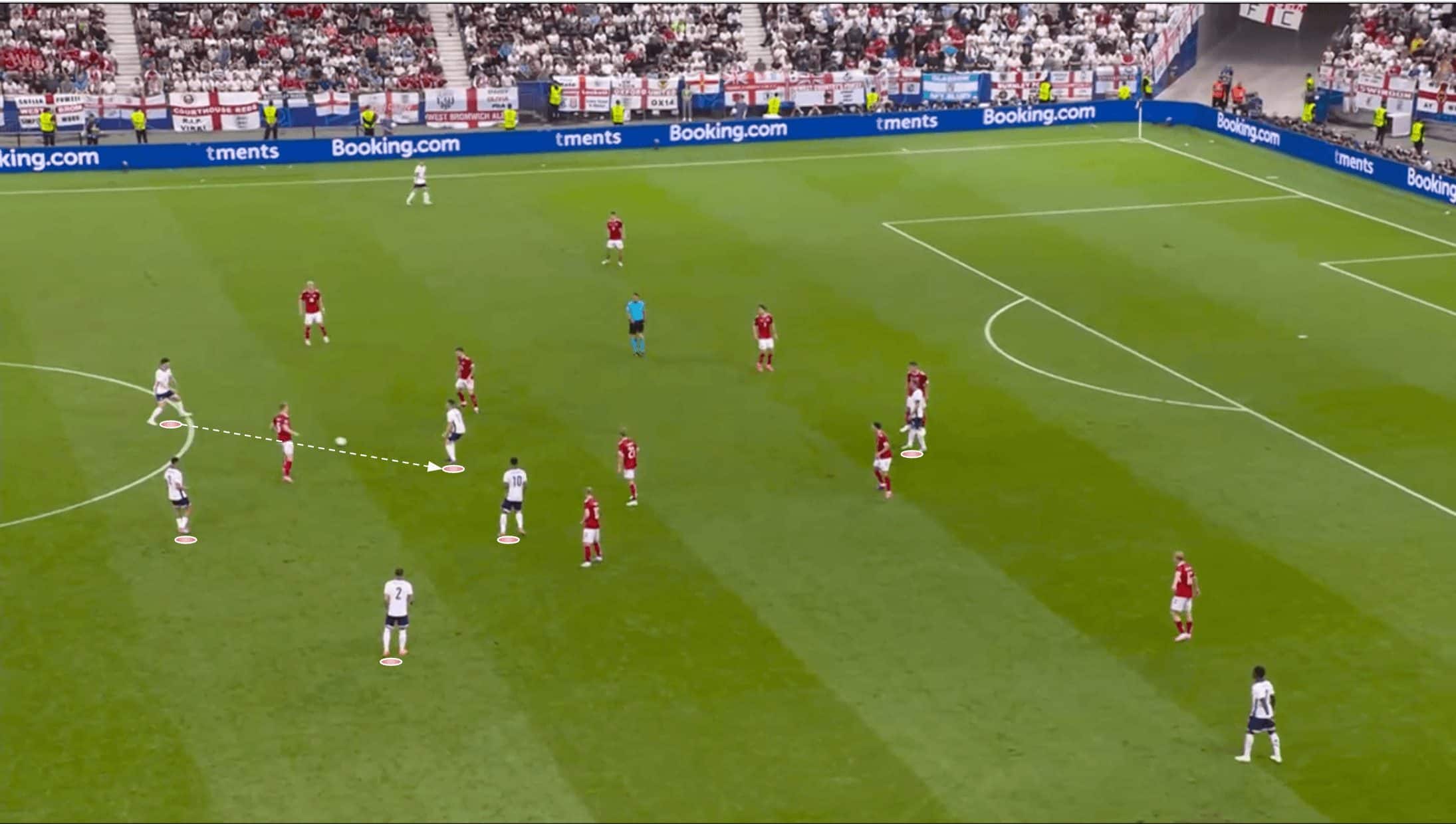

In figure 7, we find Foden, Alexander-Arnold, Bellingham, Rice and even right-back Kyle Walker all on top of each other in midfield. Nobody is making a run off into the space between the lines, and there’s no clear path out of the circle.

Saka, Kane, and Trippier provide either width or depth, but the passing lanes to those players are not open, meaning their static nature is also unhelpful.

This is again exemplary of the profiling issues within England’s midfield. There are a lot of players who want to receive the ball to feet in the middle third, and not many who want to receive a pass into the space ahead of them that they can run onto and carry into the final third/the opposition’s penalty area. This has been a leading cause of England’s failure to penetrate the opponent and something they’ll have to correct moving forward — again, players need to react to those they’re playing with and avoid occupying the same zones.

There either needs to be more sacrifice from England’s players and willingness to make runs into positions they may not generally want to be but need to be at that moment based on the dynamics of the game or more strict direction from the coach as to where each player needs to be at each time — a more restrictive game but one which may be necessary and can be effective if the players don’t find those solutions on their own.

Not enough movement

Connected with the previous section, naturally, is the topic of our second section — the fact England’s players have simply not offered enough off-the-ball movement for one another during the Euros so far.

Turning to the positives briefly, not everything has been bad from England’s attack — there have been occasions when they’ve played well and managed to penetrate the opposition. This has mostly occurred down the right, where Saka and, to a lesser extent, Walker have made good penetrative runs in behind and made themselves attractive passing options.

A run from Saka for a Walker ball in behind led to England’s first goal of the tournament — the only goal of the game in their competition-opening 1-0 win over Serbia — while an overlapping run from Walker down the right flank proved pivotal in creating the Three Lions’ goal in the 1-1 draw with Denmark in game two.

The profile of Saka is extremely necessary for this team because he will make these kinds of runs in behind, while Walker is also very capable of providing that depth and width, which may be important for Southgate’s side moving forward.

England will need more of this from other players, as just Saka may not be enough. They’ll need fewer players coming for the ball to feet and more making runs in behind to provide the necessary balance to stretch the opposition vertically, potentially creating more space centrally as well as giving the passers of the side options in behind.

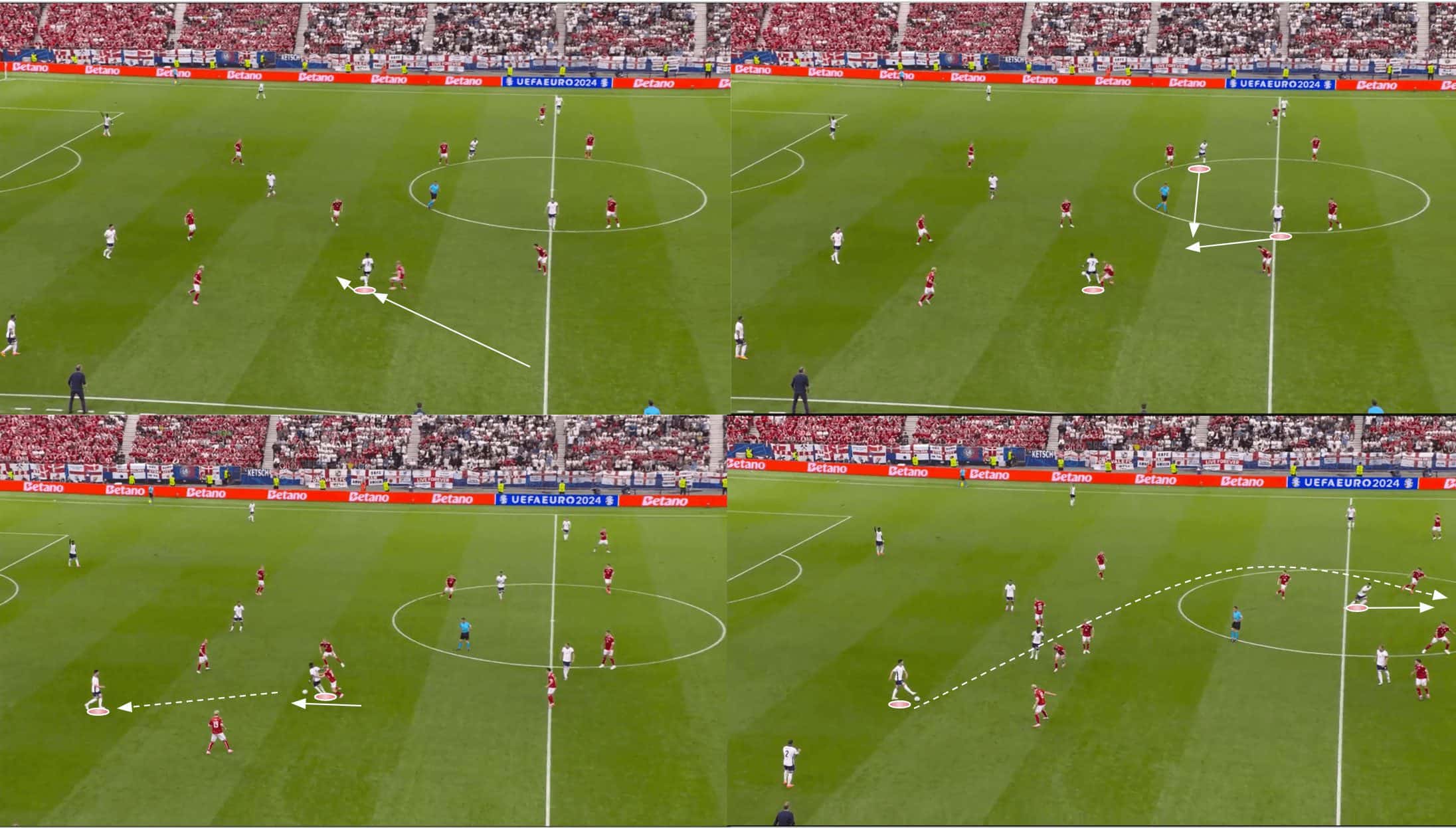

Here in figure 9, Saka dropped to receive to feet, and there was space for either Kane or Bellingham to create a helpful passing angle for the Arsenal winger. Neither made this run highlighted in the top-right image, resulting in Saka having to go backwards.

Eventually, a penetrative run is made as Bellingham attempts to create an option in behind, but the pass is too strong.

Bellingham’s run at the end here was positive and something Southgate may want to see more of with Kane dropping deeper.

As Luis Kircher of Total Football Analysis pointed out in his analysis of FC Bayern’s dynamism in attack with his tactical preview titled: “What to expect as Harry Kane and Serhou Guirassy meet when FC Bayern host Stuttgart” in December, Jamal Musiala of Bayern frequently transitions into the centre-forward role when Kane drops deep — a dynamic which has been successful for Kane throughout his career whether it was with Heung-min Son or Dele Alli at Tottenham Hotspur as well.

The 30-year-old goalscorer thrives when he has a ‘10’ playing just off of him who he can interchange with. Still, at the Euros thus far, as figure 4 and figure 7 of this tactical analysis displayed earlier, he has been left largely isolated in the centre-forward position, and while Saka provides some depth for Kane to potentially link up with when he receives to feet, the Bayern forward does usually prefer someone closer to connect with. Bellingham may be better served playing in this role rather than the one he’s primarily played thus far in the competition, dropping deep and sometimes getting in the way of his deeper midfield partners.

To sum up this issue and solution, England’s players need to be more cognizant of their teammates’ positioning and movement and the options they need to be provided to improve the team’s ability to progress upfield. They need to make more runs to support each other’s next move, or they will continue to struggle with the lack of penetration they’ve been dealing with thus far.

Where they can learn from their competition

Our final section of analysis will aim to provide further solutions for England’s issues by providing examples from their competitors on a far healthier structure in terms of ball progression. The rival we’ve chosen to include here is Germany.

The Germans have qualified for the next round after finishing top of their group with seven points. Julian Nagelsmann’s side have received plenty of praise for not just achieving the victories they have but doing so in style, with Toni Kroos standing out as one of the most effective midfield playmakers of the group stage.

So, what are Germany, Nagelsmann and Kroos doing differently to England?

Turning our attention to figure 11, the top half shows an example of Germany’s typical structure in the ball progression phase. Kroos drops deep and is given plenty of space in front, with Germany’s attackers forming a clear five-man forward line with players not positioned too close nor too far in relation to each other, adequate width on both sides of the pitch and five channels across the width of the pitch all occupied.

In this case, Kane’s club teammate Musiala receives in the right half-space and is able to carry the ball past the defender, who comes out to meet him towards his more central attacking teammates.

In the bottom half of this image, again, we see a stark contrast between the amount of space Kroos is given and the amount of space England gave their deep-lying playmakers. They show far greater respect for Kroos’ passing range and understand exactly where they need to be at the moment the Real Madrid man receives in this position.

Kroos repays their faith by finding a teammate in the kind of central ‘10’ position which England have too often left unoccupied in the Euros so far, setting up an opportunity for that receiver to link up with the runners behind him who react well to his reception between the lines.

In short, there are lessons for England to learn from the off-the-ball movement and teamwork on display by Germany in the ball progression phase if they want to improve in this area.

Conclusion

To conclude our tactical analysis and scout report, England’s issues have been plentiful in this tournament but in no area more than the ball progression phase, where their lack of cohesion and teamwork has been drastically emphasised.

Things aren’t necessarily beyond the point of no return, but lessons need to be learned quickly from their early group stage struggles. Otherwise, it’s very difficult to see them fulfilling the potential many believed they had heading into this tournament.

Comments