Saturday’s early EURO 2020 kickoff sees the Czech Republic take on Denmark in Baku Olympic Stadium. Denmark will go into this game off the back of a hot streak, scoring eight and conceding just one in their last two games. Meanwhile, although the Czechs haven’t been as prolific in front of goal as their upcoming opponents of late, scoring five in their four EURO 2020 games so far, they’ve only conceded two goals in this summer’s European Championships.

Evidently, Denmark have been one of the best teams going forward in the last two gameweeks of this competition. They are bested by only Spain in that regard. Both Denmark and the Czech Republic have earned the right to name themselves amongst those with the best defensive records in the last two gameweeks, however, with just England and Belgium conceding fewer in that time (0).

In this tactical analysis piece, in the form of a tactical preview, we’ll provide tactical analysis of some key elements of both Denmark and the Czech Republic’s tactics. We’ll preview how we believe both sides are likely to set up on Saturday and we’ll highlight some potential keys to victory, including how Denmark’s 3-4-3 – which they’ve utilised for the majority of EURO 2020 – and the versatile options in their squad could hold Czech Republic’s kryptonite and forge a way into the semi-final, where the winner of this game is set to take on the winner of England vs Ukraine.

Predicted lineups and formations

Firstly, we predict that Jaroslav Šilhavý will set his team up in the 4-2-3-1 shape that they’ve used in the majority of their games in this tournament in their quarter-final clash with Denmark. We expect Tomáš Vaclík, who most recently played for Sevilla at club level and has been linked with clubs like Sevillistas Rojiblancos’ La Liga rivals Barcelona and Serie A side Napoli of late, to retain his place in goal, where he’ll play behind the Czechs’ regular back four comprising of right-back Vladimír Coufal, right centre-back Ondřej Čelůstka, left centre-back Tomáš Kalas, and left-back Jan Bořil – the latter of whom will be available again following his suspension for Czech Republic’s win Round of 16 clash with the Netherlands.

Coufal’s West Ham United teammate Tomáš Souček and Tomáš Holeš will likely start in the holding midfield positions, behind right-winger Lukáš Masopust, left-winger Jakub Jankto, Vladimír Darida in the ‘10’ position, and Patrik Schick at centre-forward. Holding midfielder Alex Král, centre-forward Adam Hložek and central midfielder Petr Ševčík are other potential starting XI options who are likely to at least make a substitute appearance at some point on Saturday, as each of them have gotten onto the pitch at some point in all four of their nations EURO 2020 games so far this summer.

As for the Danes, we anticipate that Kasper Hjulmand will set his side up in the 3-4-3 shape they’ve utilised for the majority of this tournament, reverting from the 4-3-3 that they switched to during their Round of 16 clash with Wales – a tactical decision that proved vital in the Danish win and which highlighted the tactical and positional versatility within Hjulmand’s squad. Should they need to, they can make a switch like this again in Saturday’s game, however, as we’ll go on to discuss later in this tactical preview, the 3-4-3 may actually be a perfect solution to Czech Republic’s tactics.

Denmark have one of Europe’s best goalkeepers at their disposal in the form of Kasper Schmeichel. We expect him to start in goal on Saturday behind a back three which will ideally be comprised of right centre-back Andreas Christensen, centre-back Simon Kjær, and left centre-back Jannik Vestergaard. However, Kjær remains a doubt for this game having come off injured versus Wales and Joachim Andersen may be drafted in to replace him. However, Kjær has played a key role for Denmark in this tournament and if there’s a chance he can play, that may be a risk worth taking for Hjulmand with a semi-final place at stake, though Andersen is a capable replacement.

We expect Daniel Wass to start at right wing-back across from Joakim Mæhle at left wing-back, while Pierre-Emile Hojbjerg and Thomas Delaney will likely continue their partnership in central midfield. Lastly, we predict that Denmark’s front three will consist of Martin Braithwaite on the right, Mikkel Damsgaard on the left, and Kasper Dolberg in the centre-forward position, with Yussuf Poulsen potentially lacking match fitness. Right-back Jens Stryger Larsen, centre-forward Andreas Cornelius, and central midfielder Mathias Jensen have all also featured in each of Denmark’s four games so far in this competition, so could be Hjulmand’s most likely substitutes for this one too.

The Czech Republic in possession

One notable aspect of the Czech Republic’s tactics in possession is that they’ve made fewer dribbles on average (13.32 per 90) than any other side to have competed at EURO 2020. They utilise 1v1s and take-ons less than most inside the final third, while they don’t tend to progress the ball via runs a lot, instead preferring to try and pass their way into crossing positions high up the pitch and progress through the thirds, bit by bit, via intricate short passing sequences. They also direct long-balls from the back towards attackers quite often, as 187cm (6’2”) Schick and even 192cm (6’4”) Souček – who advances from his base holding midfield position – often enjoy a physical advantage over an opposition defender who they’ll deliberately stand on, at times, during the ball progression phase to target.

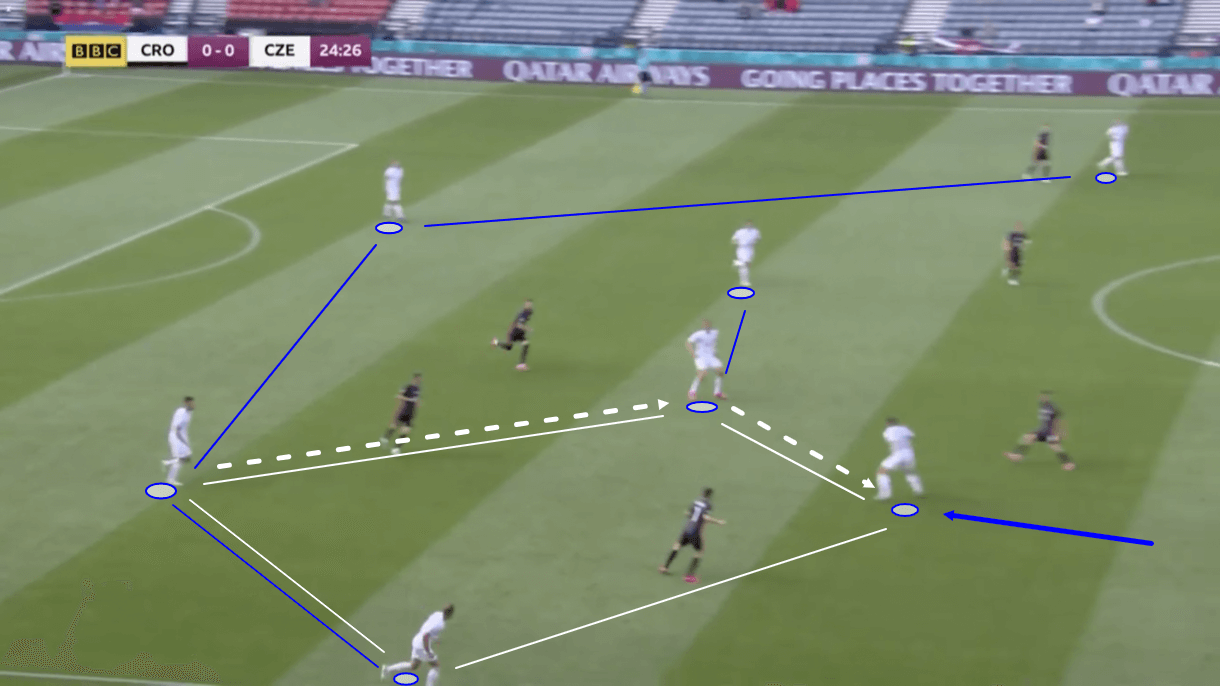

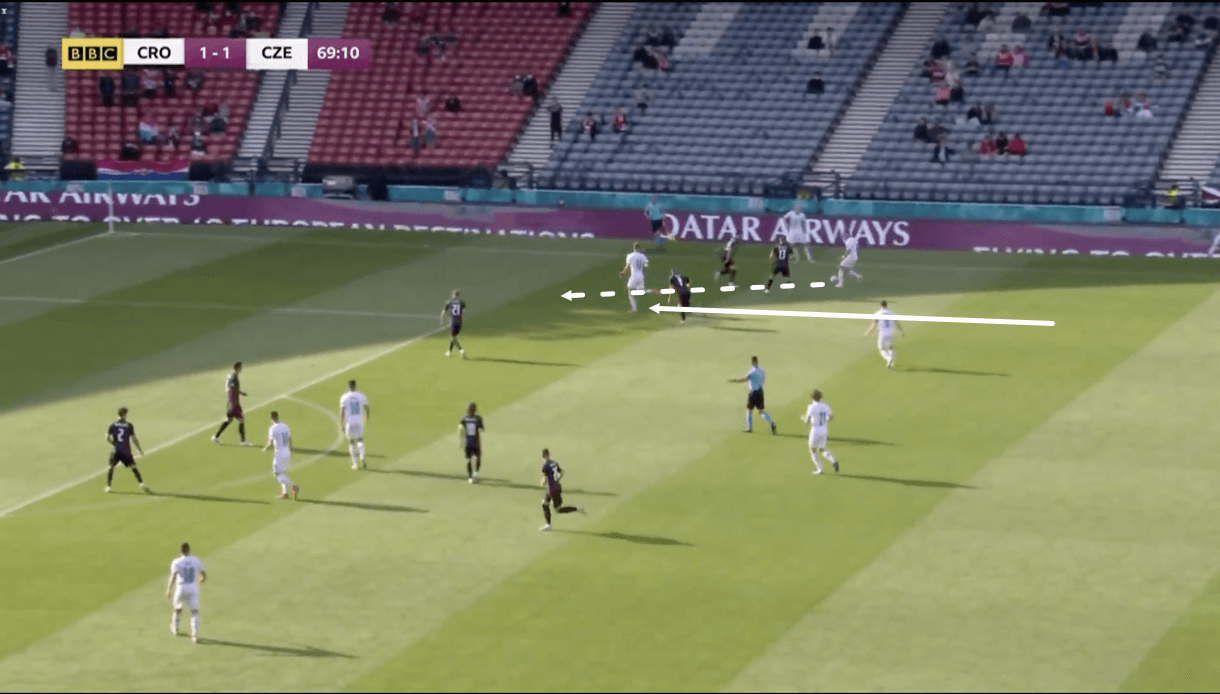

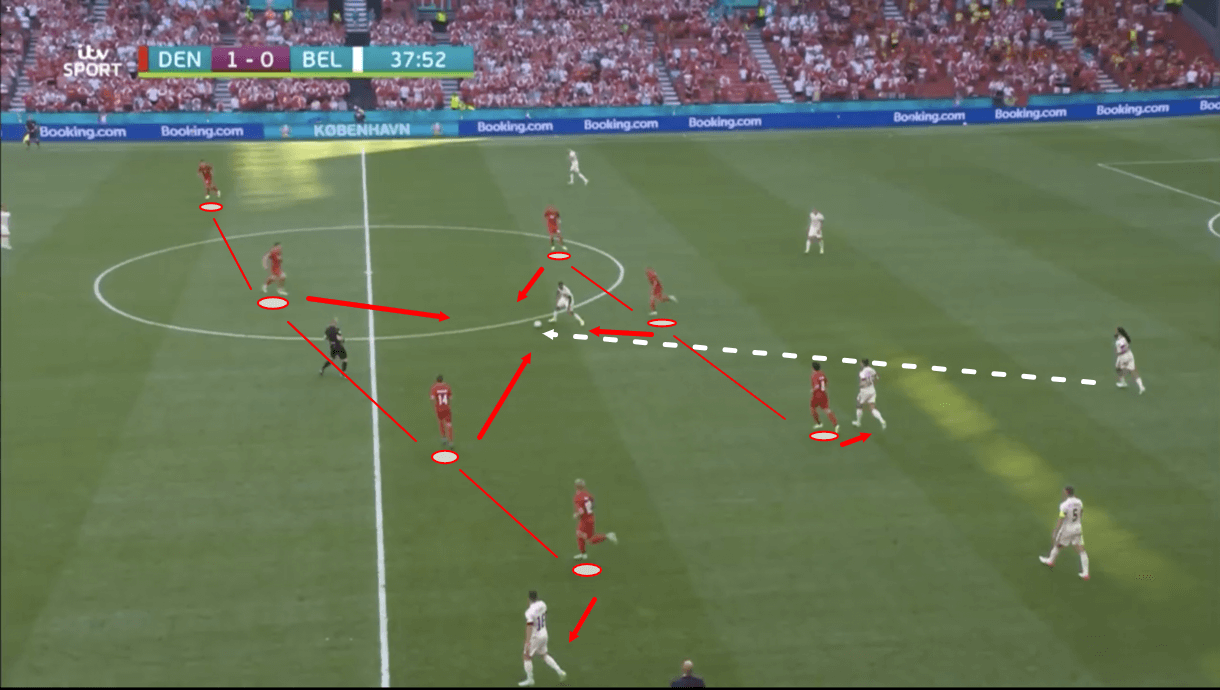

Figure 1 shows a typical example of how the Czech Republic look while building an attack via short passing. Firstly, their centre-backs tend to shift very wide, allowing a lot of space to form between them which can allow the opposition to cut them off from one another relatively easily. However, they take this risk to form the wide diamond that we see on the right here. This shape creates lots of natural passing angles for the Czech centre-backs, holding midfielders and full-backs, making ball progression via short passes easier.

In this example, The ball moved from the right centre-back to the right holding midfielder to the right-winger, who’s dropped from his advanced attacking position to a slightly deeper one, supporting his deeper teammates to form the tip of this diamond. The wingers play a key role in Czech Republic’s build-up because of this movement. From here, they can potentially carry the ball forward, however, more often, they continue to progress via short passing. As the winger turns here, he’ll have the right-back – who we see advancing in figure 1 – as a short passing option to his right, the ‘10’ to his left, and the centre-forward as the furthest forward passing option.

Centre-forward Schick is often required to make runs into wider channels to support teammates during this phase, while his physicality can also make him a viable option for a long-ball in this phase, as he can back into opposition players, hold up play and help his team gain some territory.

The Czech Republic can be vulnerable to high pressure, which Denmark are accustomed to applying, in this phase. Firstly, the passing lane between the Czech centre-backs can easily be cut off quite early and if the options in the wide diamond are marked or cut off, then the Czech centre-backs can be caught in possession or forced to play rushed, inaccurate long-balls. Additionally, while the wide diamond allows for lots of natural passing angles to be formed, creating lots of passing options, the opposition can prepare for the passes into the holding midfielders and wingers, setting up pressing traps around them which could lead to high turnovers. This kind of pressure is something that the Czech holding midfielders, particularly Souček, could be vulnerable to, so it may be an area that Denmark prepare to target.

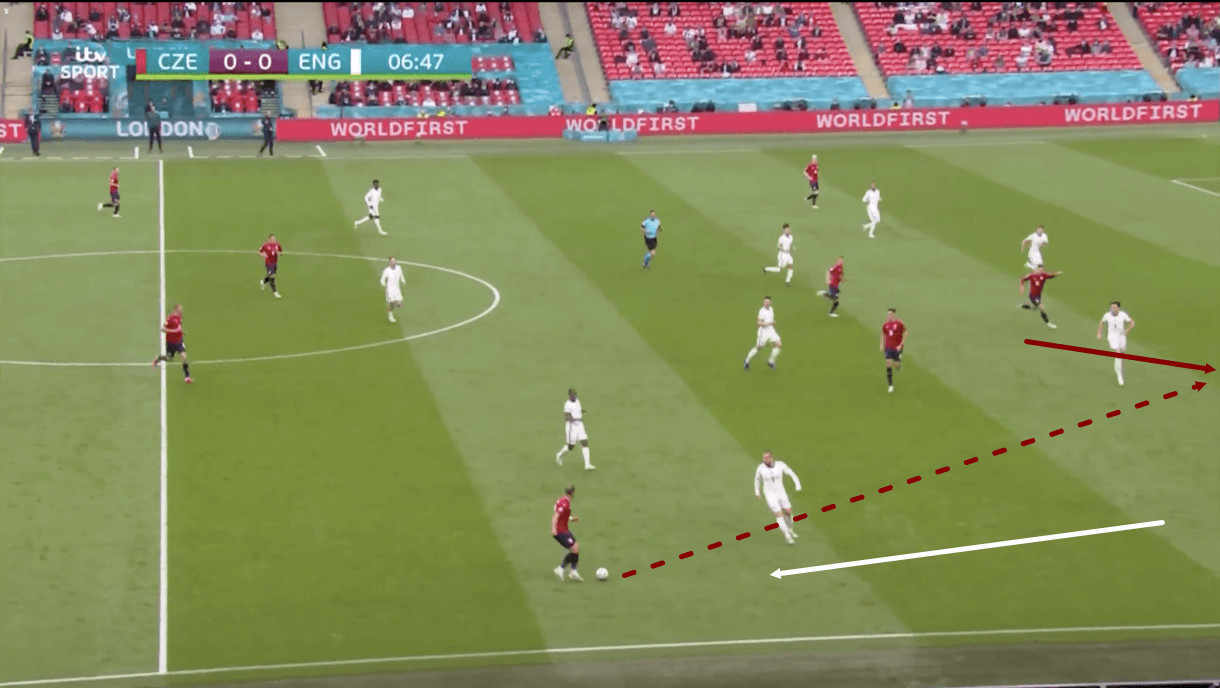

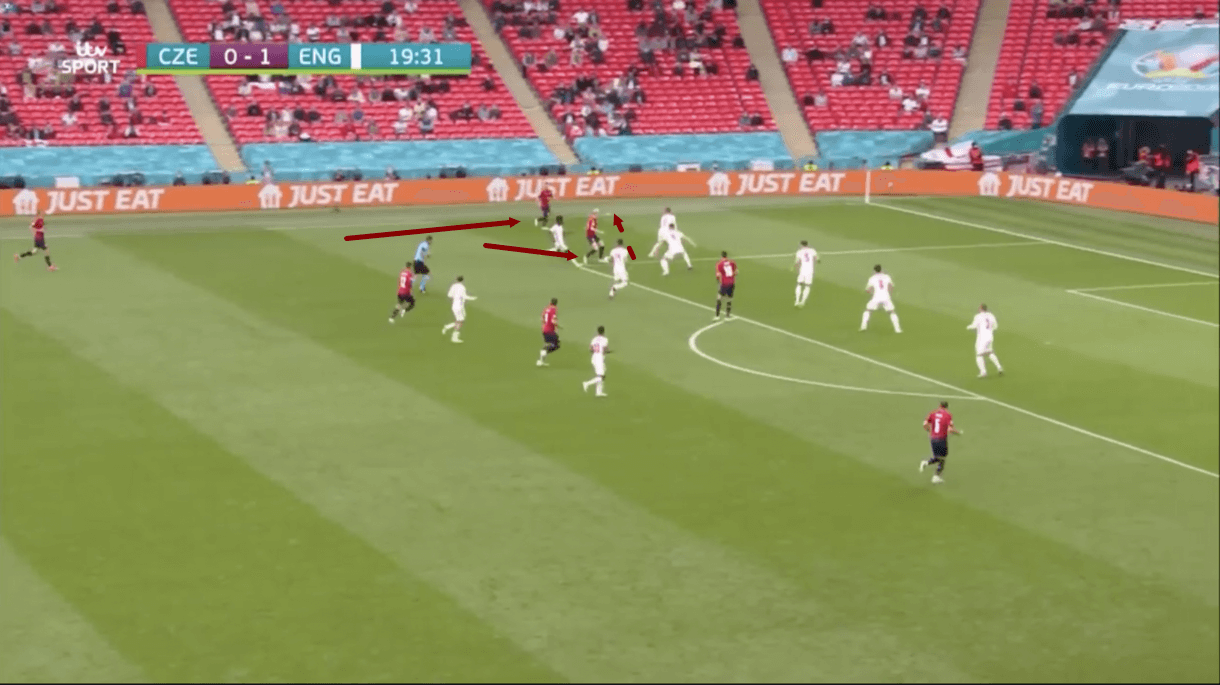

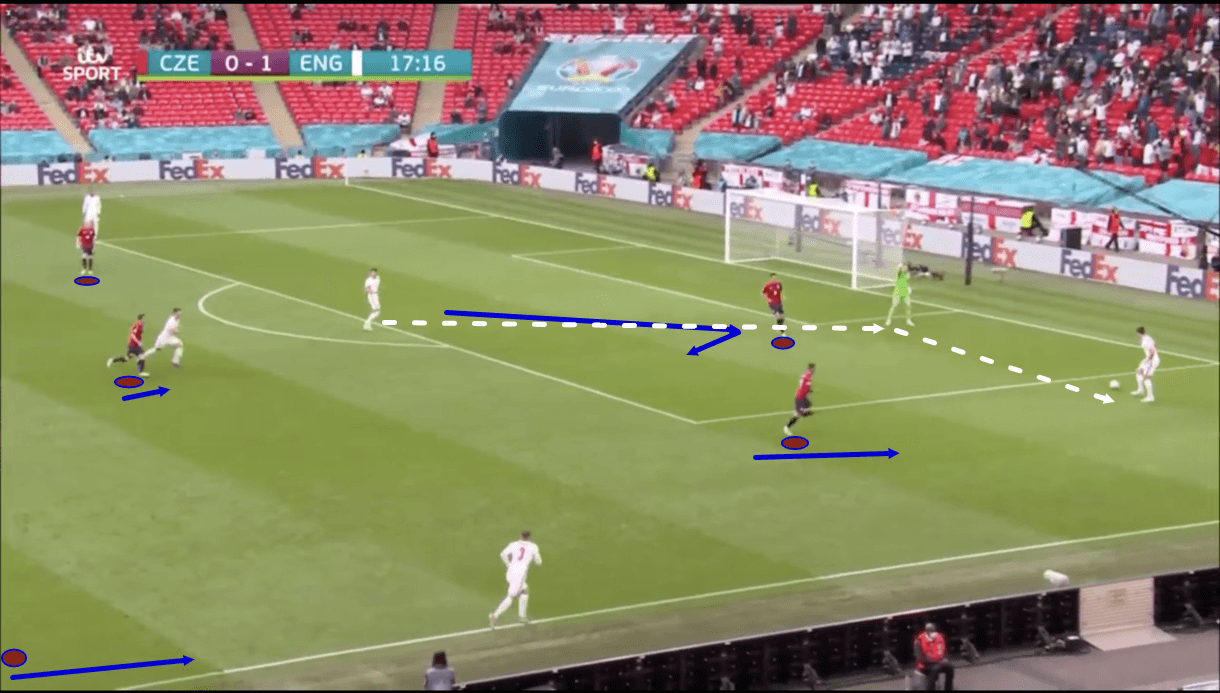

Further up the pitch, when playing into the final third and penalty area, Czech Republic have frequently relied on through passes into the channels between the opposition’s full-back and centre-back, meeting runs from the ‘10’, centre-forward, and wingers. We see an example of this in figure 2, where Coufal is lining up – and ultimately goes on to play – a through pass into the channel between left-back Luke Shaw and left centre-back Harry Maguire in Czech Republic’s group clash with England.

As was the case on this occasion, Czech Republic generally endeavour to open up this channel through the full-backs. Coufal attracts the full-back towards him, drawing him away from the near centre-back, creating space for his pass to travel through and the runner to target.

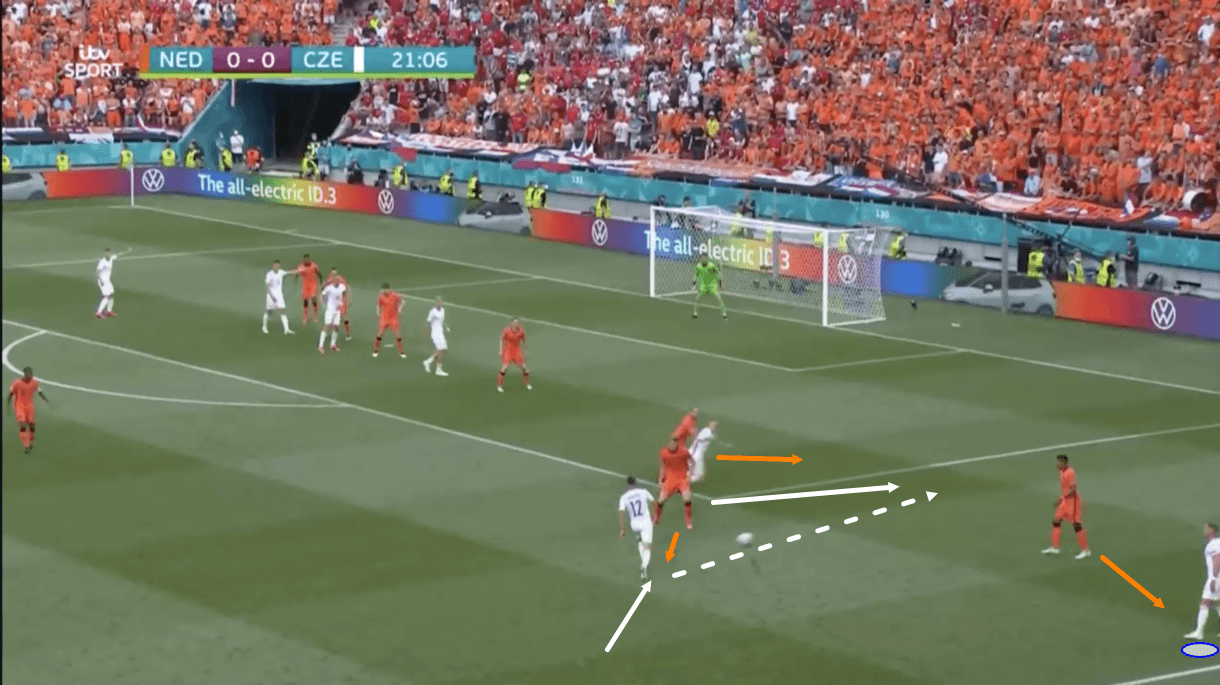

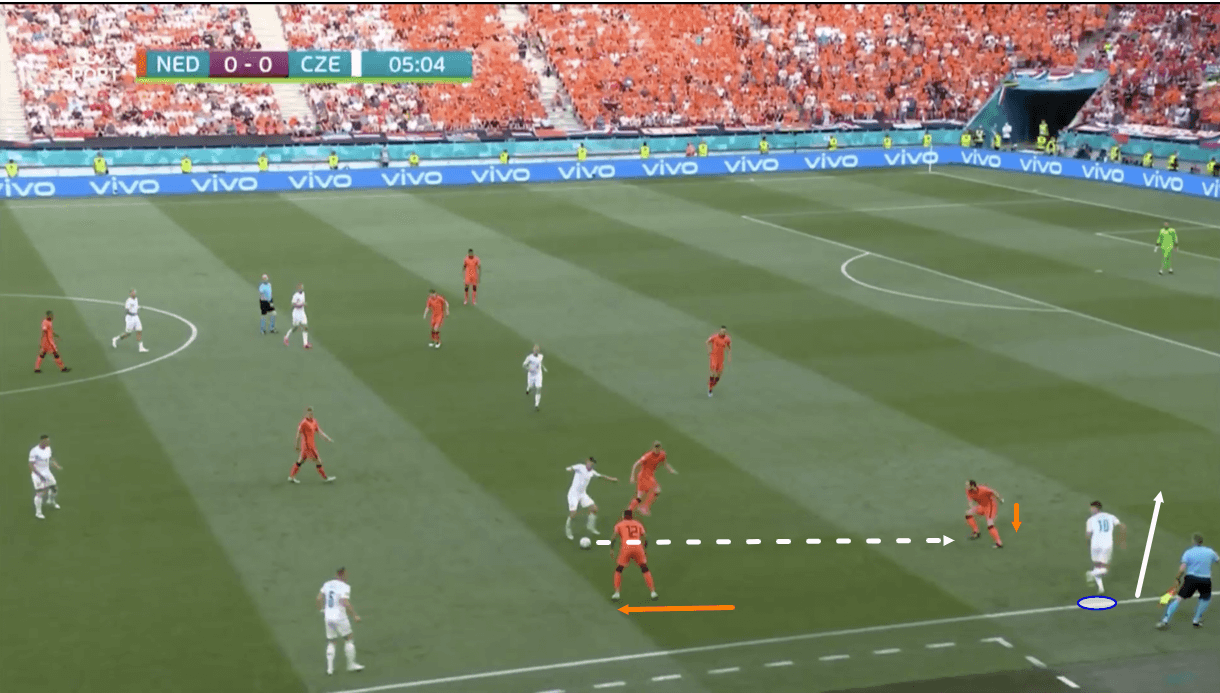

In figure 3, we see another example of this space being targeted, this time versus the Netherlands. On this occasion, right-winger Masopust is on the ball, and while his dribbling threat plays an important role in drawing the near central midfielder towards him and away from covering the space in the backline, the full-back arguably plays the most important role once again, as his wide positioning pins the wing-back out wide, allowing some space to form for the runner and passer to target.

The position that the runner ends up in here – right at the byline – is one that the Czech Republic love to target. They play the majority of their balls into the penalty area from this advanced position which they tend to progress into via these through pass between the wide centre-back and the wing-back/full-back.

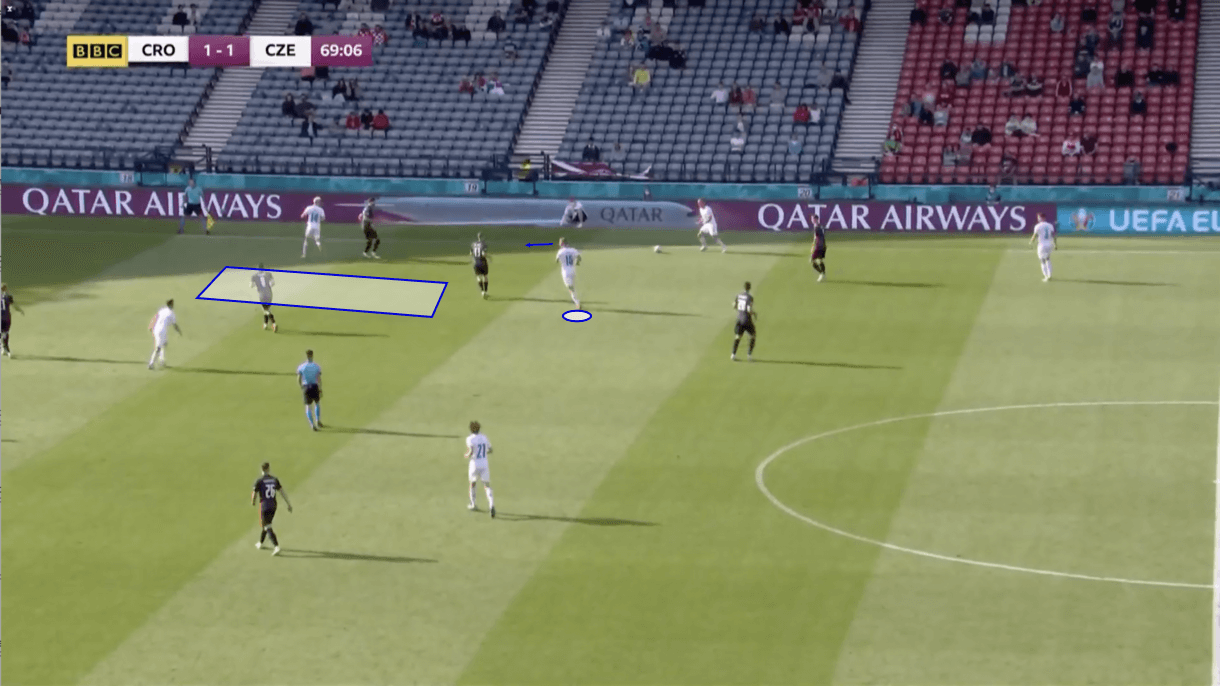

Figure 4 shows another example of the Czech Republic targeting this space, this time via a run from one of the two holding midfielders. These players, particularly Souček, like to probe forward into this channel to offer an option where possible. In this case, we see the right-back in their deep, playmaking position just outside of the final third once again. The opposition full-back was patient and disciplined here, refusing to get drawn out towards the right-back and doing well to cover the passing lane to the winger. However, by covering the winger’s run out wide, they still allowed the Czech Republic to open the lane between the full-back and centre-back and we see that the holding midfielder noticed this in figure 4, as he began lasering in on this zone for a forward run.

After scanning a few more times, the holding midfielder burst forward into this channel, as we see in figure 5, and ended up on the receiving end of Coufal’s through ball. So, again, we see the important role of the full-back and how they, the winger, and the holding midfielder link up to attack this channel via through balls to progress into their team’s favourite crossing position.

Czech Republic’s wingers tend to position themselves quite narrow to create space for the full-backs to venture into. While the Czech Republic primarily enter the final third via these through passes into these channels, the wingers sometimes carry the ball in there themselves, though as we mentioned, Czech Republic are the least dribble-heavy side in the competition, so this isn’t very frequent. When they do, however, they attack the half-space and can force the opposition full-back inside, creating space for the full-back on the wing. We see an example of this in figure 6 and as this passage of play moved on, the full-back received the ball with plenty of room to cross.

We see how important the advancing full-backs’ roles are in the Czech Republic’s offensive tactics, as well as the importance of exposing space in the backline and progressing into the final third through that area. However, we believe that Denmark’s 3-4-3 can go some way to neutralising these offensive tactics.

For example, before Matthijs de Ligt’s sending off, Czech Republic faced a three/five-at-the-back formation versus the Netherlands and we saw how this could be effective at preventing Czech Republic’s progression into the final third. In figure 7, we see a typical example where Netherlands’ wing-back has been drawn upfield and space would normally be created between him and the near centre-back. However, with an additional centre-back in the squad, left centre-back Daley Blind was able to effectively enter the full-back position, occupying this space and intercepting the through ball.

At other points in this game, the wide centre-backs were drawn out of position by the narrowly-positioned wingers and then it was up to the wing-backs to control the space in the backline, preventing the Czech Republic from easily playing through them. Preparation for Czech Republic’s plans and communication between the players will be key for Denmark in their attempts to stop Czech Republic from exploiting this area as they have done successfully during EURO 2020.

However, with their back-three/five, Denmark’s wing-backs may enjoy more freedom to engage with Czech Republic’s full-backs higher, knowing that the wide centre-backs are preventing space in the backline from being exposed. If they can do that, then Denmark may be able to stifle Czech Republic’s chance creation significantly, thus enjoying more time on the ball and being able to put them under more pressure.

Denmark’s defence

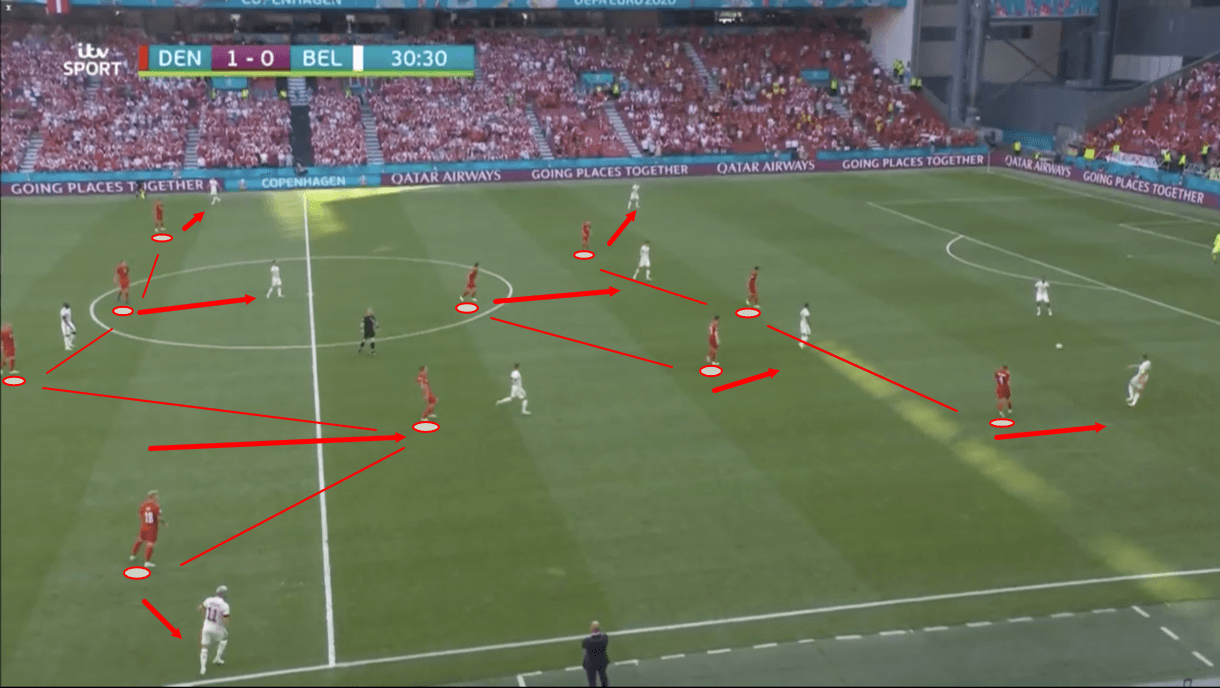

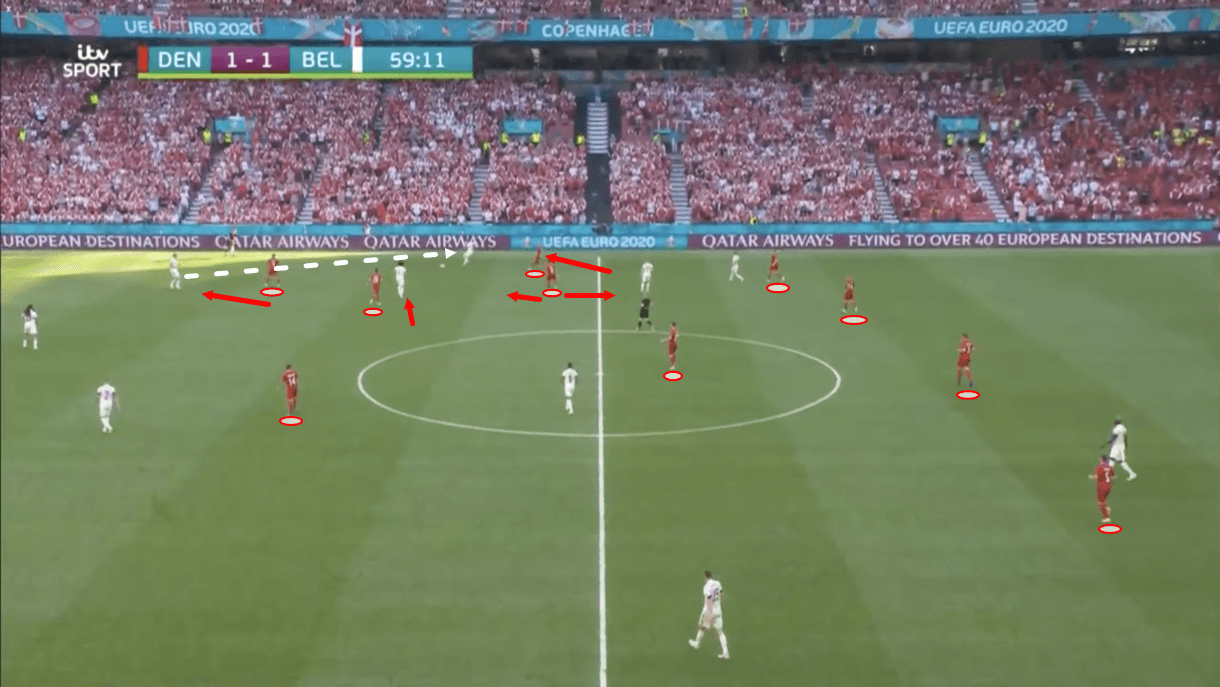

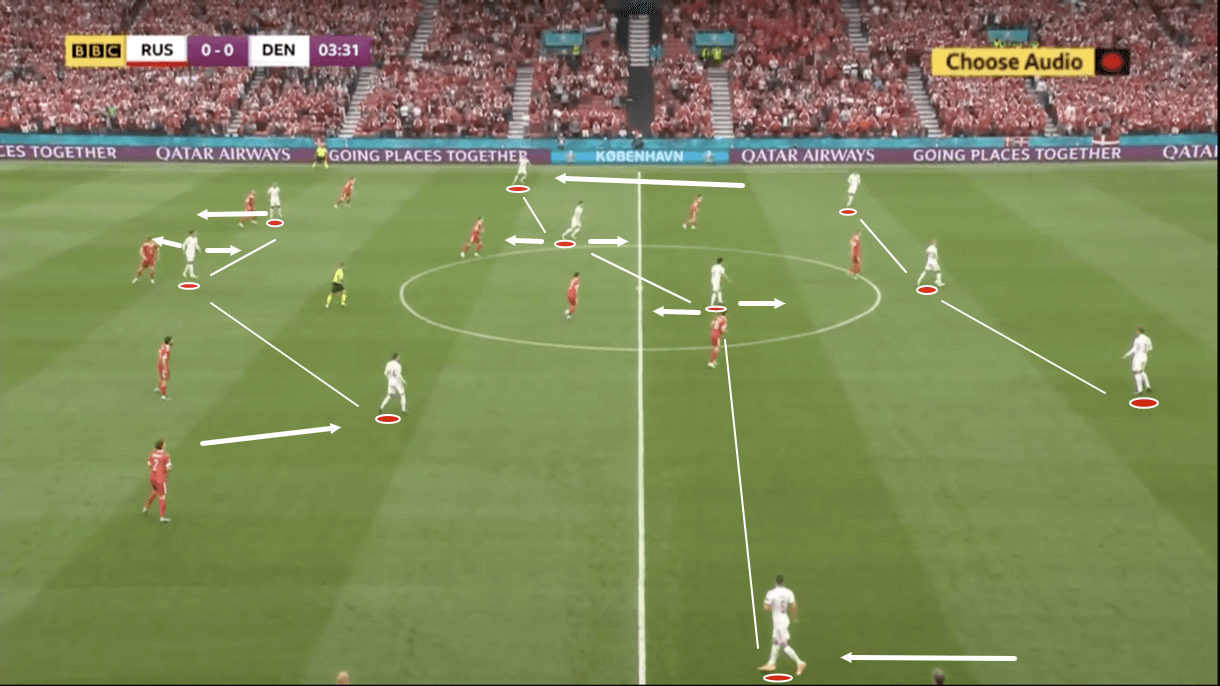

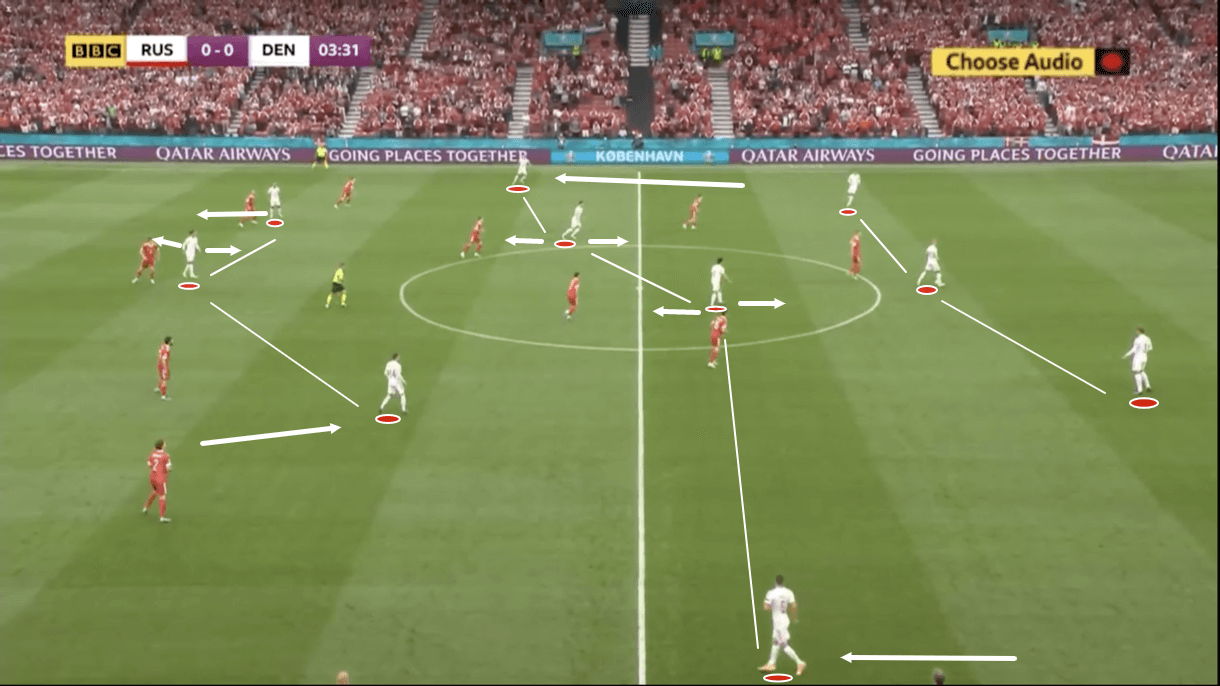

Figure 8 shows an example of Denmark’s 5-2-3 base defensive shape. The Danes utilise a heavily man-oriented press and during the opposition’s build-up, when the ball is central, they tend to maintain a good balance around the pitch, with access effectively retained to all opposition players. During this phase, when the ball is central, they just try to ensure that the opposition don’t create numerical superiority in any one area. This can lead to unfavourable 1v1s being created or potentially dangerous space opening up but it is effective at preventing the opposition from creating an imbalance and exploiting space.

In figure 8, we see how the opposition’s wingers are sitting behind Denmark’s central midfielders, attempting to exploit the large amount of space opening between the lines. Denmark are one of the most aggressive pressing sides in EURO 2020, with the sixth-lowest PPDA (10.0) in the competition. Their central midfield duo play an important role in this press and as a result, space can open up between them and the backline for the opposition to exploit. However, Denmark’s man-oriented press gives their centre-backs license to push out of the backline and pick up players between the lines, preventing them from exploiting the space.

We see Christensen doing this in figure 8, while Vestergaard does so too, at times. With the wing-backs focusing on the opposition wing-backs, who are positioned high, this can leave Denmark looking like a 4-3-3 or 3-2-2-3 shape at times, but the shape isn’t so important or even really worth noting on this point because of how man-oriented their press is.

In general, when pressing, Denmark’s centre-forward first looks to prevent passes from being played into midfield through his body positioning, while the wingers retain access to the wide centre-backs/full-backs, depending on the opposition’s shape. As the ball moves to one of the wide centre-backs/full-backs, Denmark’s pressure picks up and often the play will be forced back to the previous centre-back, who will face increased pressure from the centre-forward while receiving the backwards/lateral pass. Denmark’s goal is to force the opposition into an area where they trigger increased pressure. Generally, this is either the wing or central midfield.

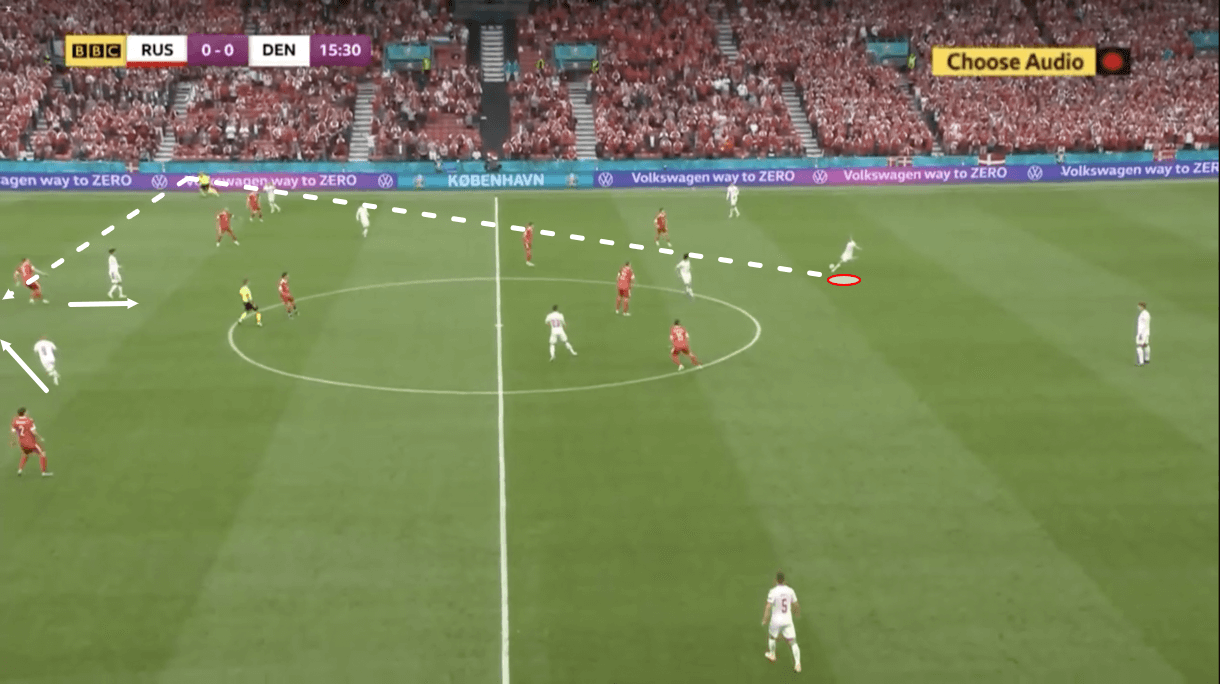

In figure 9, we see Denmark pressing as the opposition try to build via the wing. Denmark will first look to cut off the area between the centre-backs, and when the ball is forced out to the full-back, they’ll look to cut off the passing lane between him and the near centre-back. The centre-forward may drop onto the ball-side holding midfielder while the wingers press the centre-backs and the wing-backs press the full-backs. When they manage to force the ball out wide and their pressure increases, Denmark essentially start to ignore the opposite side of the pitch now, as the likelihood of an accurate, dangerous ball being quickly played across the pitch is far lower than when the ball is central, and they can focus more on ensuring all near passing options are covered and space in the backline is covered.

Now, Denmark enjoy a numerical advantage at the back and an advantageous pressing scenario further up the pitch. If they can replicate the scenario we see in figure 9 versus the Czech Republic, it will be very difficult for the Czech full-backs to have as much influence on the game and it will be very difficult for the Czech Republic to exploit space between the defenders.

In figure 10, we see an example of the ball being played into the centre during the opposition’s build-up. Generally, Denmark’s centre-forward will be preventing these passes via his body positioning but, of course, it’s possible for the opposition to get through at times. This is why Denmark’s central midfielders position themselves so high and have such an important role while pressing high. As the ball is played into the central midfielder, he will find himself between four Denmark players who immediately close in on him to deny him space and will try to prevent him from progressing further. Due to the numerical advantage, Denmark will usually fancy their chances in this situation and this is the kind of pressing scenario they may try to target the Czech Republic’s holding midfielders with on Saturday.

The Czech Republic’s defence

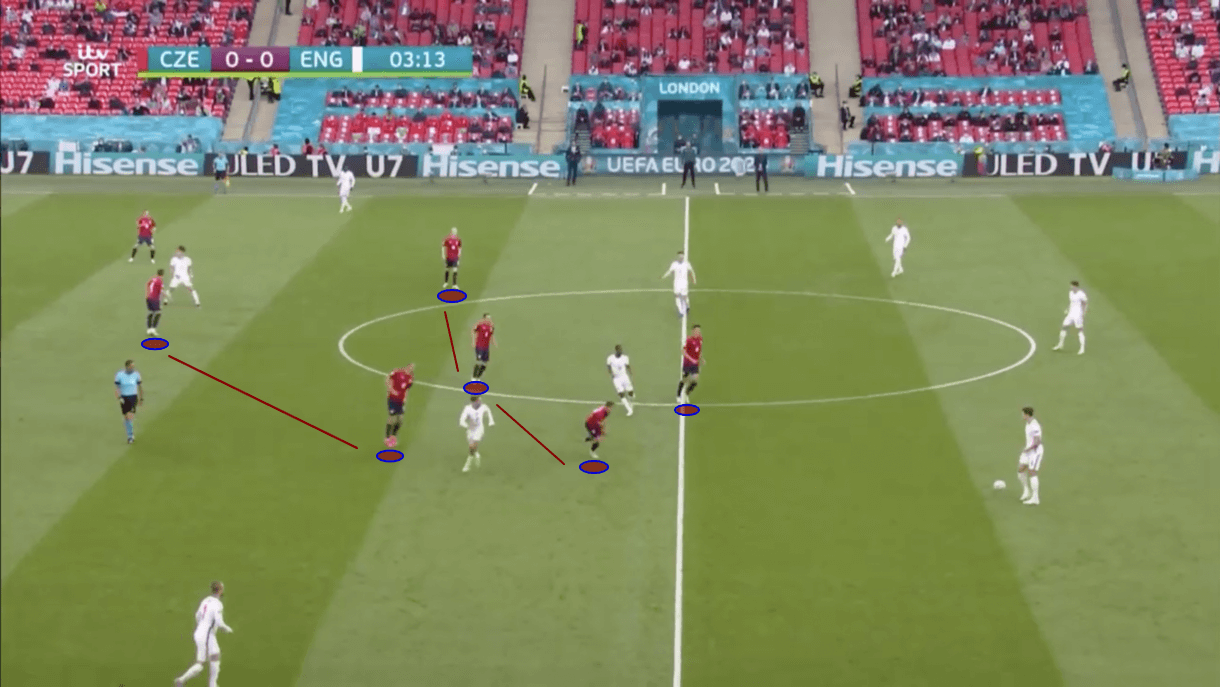

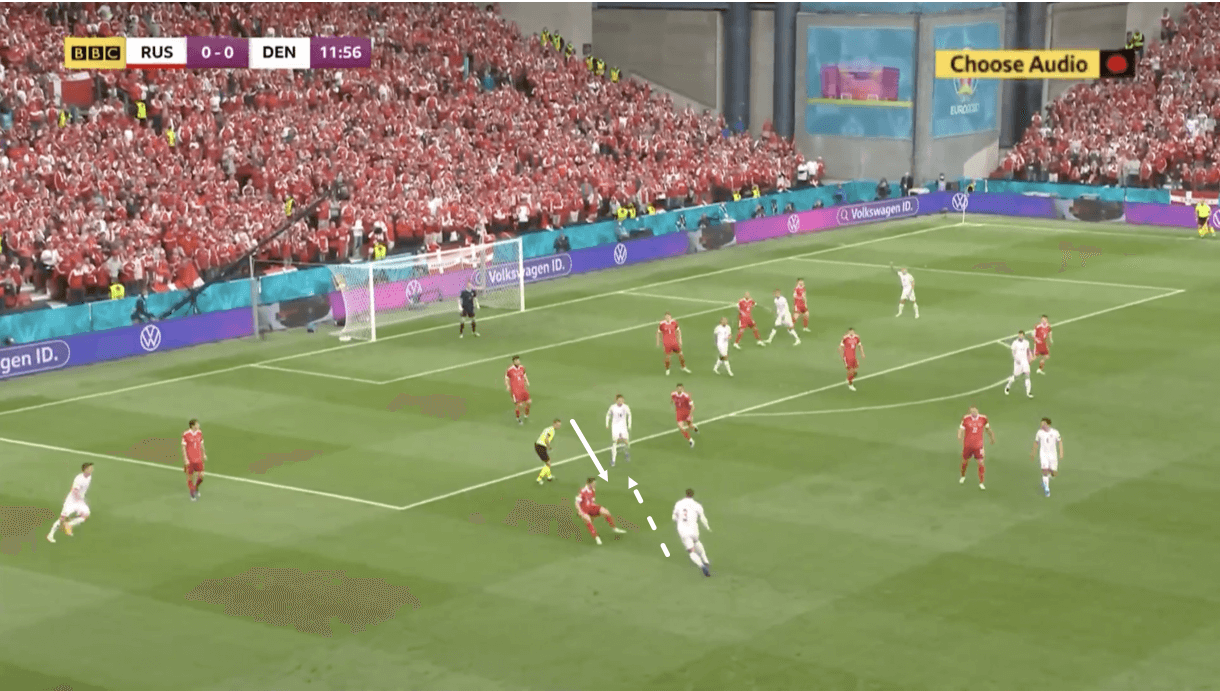

Much of the time in defence, Czech Republic will shape up as we see them in figure 11. During the mid-block phase, their 4-2-3-1 gets very narrow and compact. Similar to Denmark, their centre-forward will look to block off passes into central midfield, while the proximity of his teammates behind him offering support means that even if the opposition do manage to play past him, further progression is a challenge as they are in position to press. At this point, Czech Republic’s primary goal is enjoying central numerical superiority and thus controlling this area of the pitch.

As figure 11 also shows, however, this defensive shape allows the opposition plenty of space out wide which can be exposed and in the ball progression phase, Denmark may look to exploit this through the wing-backs. While Czech Republic have made fewer dribbles than any other team at EURO 2020, Denmark have made the fourth-most dribbles (29.0 per 90) of any team at the competition. This is an area where they and the Czech Republic differ significantly and Denmark will be far more comfortable with progressing via runs from the wing-backs, as well as entering the final third via dribbles.

During ball progression, when Czech Republic’s opponents have passed the ball out to the free wing-backs, Czech Republic’s defensive shape has generally shifted out towards that player to congest space around them and close off near passing options. However, if the opposition are quick enough to circulate possession across to the other wing, where the player on the opposite side is now enjoying even more space, then ball progression may be even easier for them and players in the deep half-space may even enjoy enough space to progress via a more central position.

England did a good job of exploiting the Czech Republic by quickly playing the ball across the backline to manipulate the Czechs’ defensive shape and create space for the likes of Raheem Sterling, Jack Grealish and Bukayo Saka to drop into and carry the ball upfield from the deep half-spaces in their group game, and Denmark may look to do something similar, with Damsgaard potentially playing a key role in this area. So, while Czech Republic look to control the centre, their opponents can manipulate their defensive shape and open up central possibilities for ball progression.

While the Czech Republic generally keep far less possession than Denmark, they are generally quite aggressive, like the Danes, during the high-block phase. Their centre-forward will look to split the opposition centre-backs, while the ‘10’ tends to man-mark one opposition holding midfielder. Denmark’s central midfielders tend to stagger in possession, so the Czech ‘10’ will generally be sitting on either Hojbjerg or Delaney in this phase. Meanwhile, the Czech wingers will mark the full-backs but press the opposition centre-backs while keeping the full-backs in their cover shadow at times too, as was the case in figure 12, while the full-back advances to press the opposition full-back and the Czech Republic aim to control all the near passing options while closing down the ball-carrier.

Czech Republic have experienced some joy and forced high turnovers thanks to these defensive tactics during EURO 2020. They are well organised and good at hounding down the opposition while keeping the nearest passing options marked out of the game or cut off from the ball-carrier. However, due to Denmark’s offensive tactics, which we’ll analyse in the next section, we feel that a more passive approach could work to the Czechs’ benefit on Saturday.

Denmark in possession

Figure 13 shows us a typical example of Denmark’s offensive 3-4-3 shape during the ball progression phase. Their wing-backs push high, providing the width either side of Hojbjerg and Delaney. The central midfielders stagger, leaving one sitting slightly higher and one sitting slightly deeper than the other. Meanwhile, one of the front three attackers – Damsgaard – will drop slightly deeper, looking to occupy space in between the lines where he could receive the ball to feet and create something via a dribble, while Braithwaite on the opposite wing will be making the opposite movement, looking to make runs in behind the opposition backline. Centre-forward Dolberg/Poulsen will make moves in either direction, either in behind the backline or dropping deep, though Dolberg will generally just drop deeper and Poulsen has been doing that far more often than running in behind in this setup too.

This shape is very balanced and the Danish players’ movements within it complement each other very well. The alternating movements of the central midfielders and the front three attackers help to disrupt the opposition defensive shape, as well as creating lots of useful passing angles and helping Denmark to exploit space.

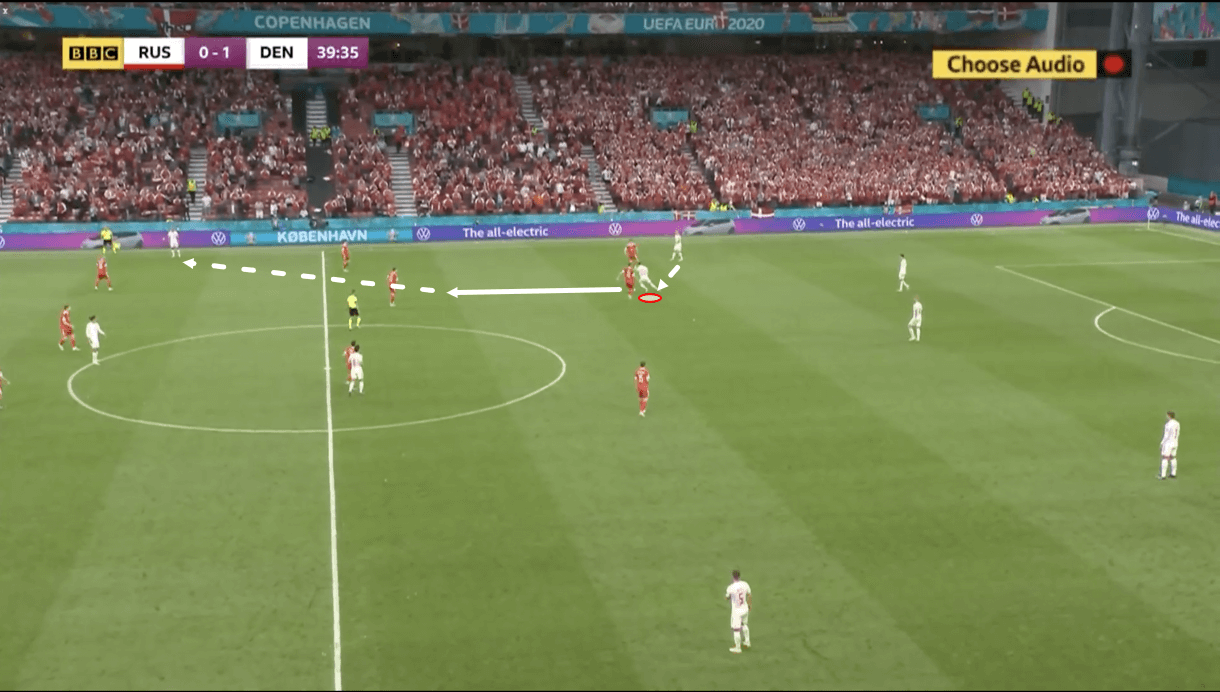

As well as making the fourth-most dribbles at this tournament, Denmark have played more long balls (45.58 per 90) than any other side at EURO 2020. Kjær, who is a doubt for Saturday’s game, and his long passing quality plays an important part in Denmark’s long ball-playing quality, as he’s often tasked with getting his head up and watching out for the front three’s movement during the ball progression phase, effectively becoming a deep-lying playmaker. We see an example of this in figure 14.

Despite Kjær and the forward line being situated about as far from each other as they could be within this system, Denmark’s long balls and the front three’s movement are very closely linked. Braithwaite is frequently threatening with runs in behind but a lot of the time, his runs in behind come when the centre-forward – Poulsen or Dolberg drop to make themselves a long ground passing option. This can drag an opposition centre-back out of position and Braithwaite then targets that space via his run. This is exactly what we see in figure 14.

Kjær watches out for the forwards’ movement and when he sees this movement from the centre-forward and Braithwaite, he’ll play the long ball in search of the Barcelona forward. This is a useful play that Denmark could especially look to execute versus the Czech Republic if the Czechs opt to press aggressively in the high-block. By doing so, Denmark could essentially bypass Czech Republic’s compact mid-block, so the Czechs must be aware of this.

Another threat that Denmark pose to the Czech Republic in attack, especially should the Czechs stick to their guns and engage with Denmark high up the pitch, is Denmark’s dribbling threat. As mentioned previously, Denmark dribble far more than most teams in this competition, especially the Czechs, and for good reason – they have quality dribblers in their side. The wing-backs will threaten via progressive runs, while Denmark’s wingers – especially Damsgaard – pose a serious creative threat via their dribbling.

If the Czech Republic engage Denmark high often and the Danes beat their press, it will result in Denmark creating 1v1s versus the Czech Republic’s deeper players more frequently. Damsgaard will be very difficult to stop in 1v1s, as might Braithwaite and Dolberg, and this is a scenario that the Czech Republic should endeavour to avoid. If they defend deeper, they could guard against these scenarios occurring and reduce the threat of Denmark’s dribbling by congesting space with their numerical advantage.

Even versus deep defences, however, as we see in figure 15, Damsgaard will drop into little pockets of space in central positions just outside the penalty area and look to receive the ball to feet, backing his ability to create an opening via his dribble. On this particular occasion above, the playmaker carried the ball from the half-space out to the wing before he played a line-breaking pass to a teammate in a more threatening position, so it will be difficult for the Czech Republic to completely reduce the dribbling threat of Denmark, and especially Damsgaard. However, 1v1 scenarios would undoubtedly be far more concerning.

Hojbjerg’s press resistance could also play an important role in Denmark’s ball progression versus the Czech Republic. The Tottenham Hotspur midfielder is capable of receiving the ball in deep areas and turning in an instant with a burst of pace while exhibiting excellent ball control. He is a fantastic passing option for Denmark in deeper areas and while the Czech Republic will congest the centre and be prepared to press aggressively if the central midfielders receive the ball, Hojbjerg is good enough to help break through the lines on occasion and put his side in advantageous positions, as was the case in figure 16. So, controlling Hojbjerg and denying him space to progress into should be a priority for the Czech Republic if they want to stifle Denmark’s ball progression.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis piece, in the form of a tactical preview, we feel that Denmark’s 3-4-3 and the personnel within it offers enough balance and versatility to trouble the Czech Republic in various phases of play. Their backline and aggressive pressing tactics could be just the solution to Czech Republic’s offensive tactics, while we believe that what Denmark offer going forward could pose a significant enough threat to make them the first side to really open up Czech Republic’s defence.

The Czechs have been very difficult to break down in this tournament while they’ve played some fantastic football throughout EURO 2020 as well, so this isn’t an attempt to knock them or their own qualities at all, however, we feel that Denmark may tactically get the better of them in this one.

Comments