After losing against Spain in the quarter-final of UEFA Euro 2024, Germany have won four and drawn one in five matches to top their group in the UEFA Nations League.

Offensively, Julian Nagelsmann‘s side has been superb, scoring 17 goals in five matches at the time of writing.

This is the highest score in the competition, with a four-goal difference over Italy, who scored 13 goals with one more match played.

Defensively, they have achieved reasonable stats, conceding three in five matches, the second-strongest defensive line after Spain, who conceded three goals in six matches.

We have noticed that they are excellent

at set pieces and have the potential to improve evenmore in the future, knowing that Mads Buttgereit is Germany’s assistant coach for set-pieces.

In this tactical analysis, we will discuss their tactics in attacking corners and how they deal with different kinds of defensive systems.

Germany’s Tactics Against Man-Marking Systems

We will begin by discussing how Germany behaves against man-marking defending systems under Julian Nagelsmann’s tactics and then proceed to discuss their corners against Hungary in detail.

Flat Passing Lane

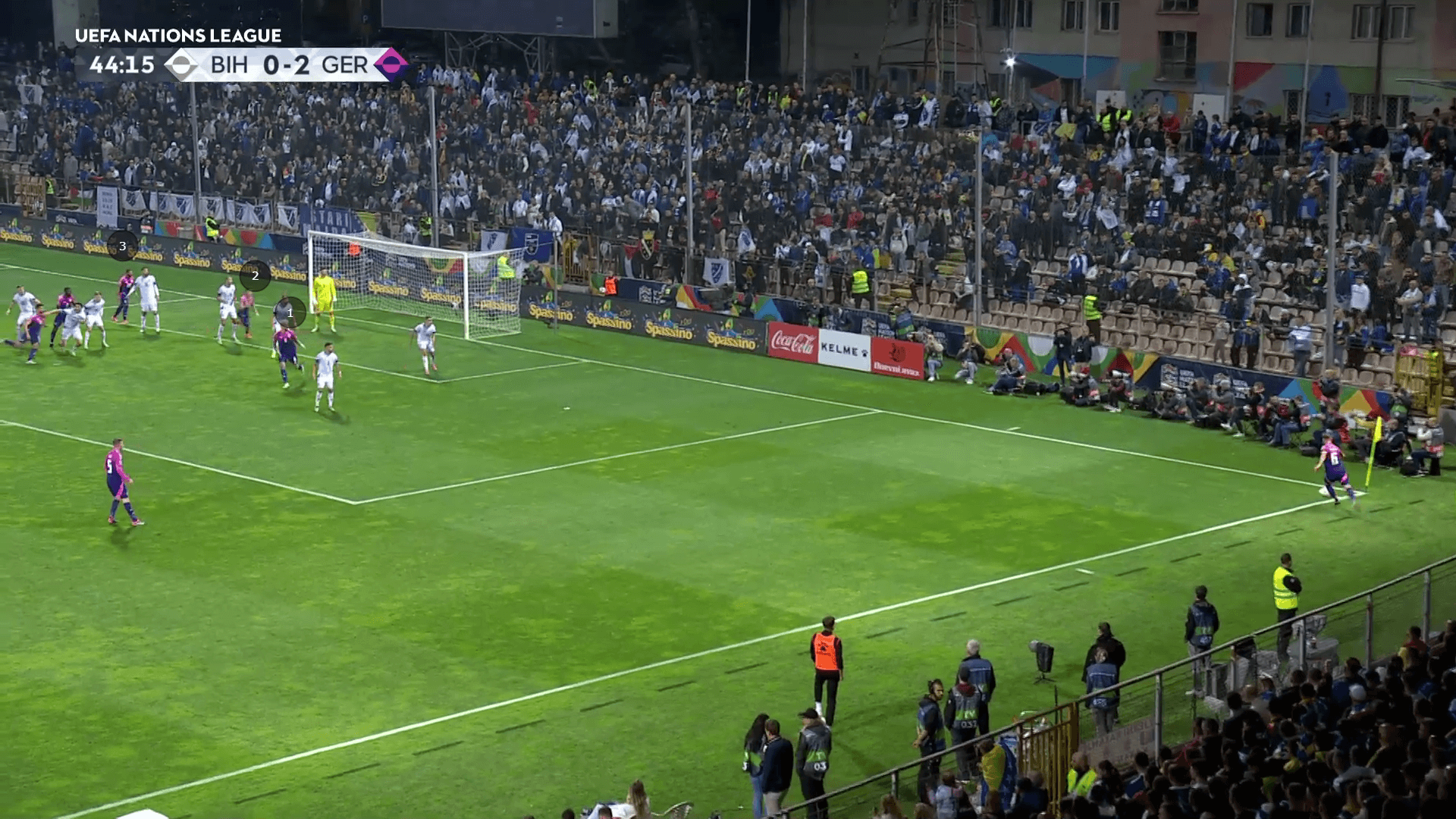

The first idea Julian Nagelsmann implemented is the “Flat Passing Lane,” which sends a direct pass, grounded cross, to the area shown in the photo below.

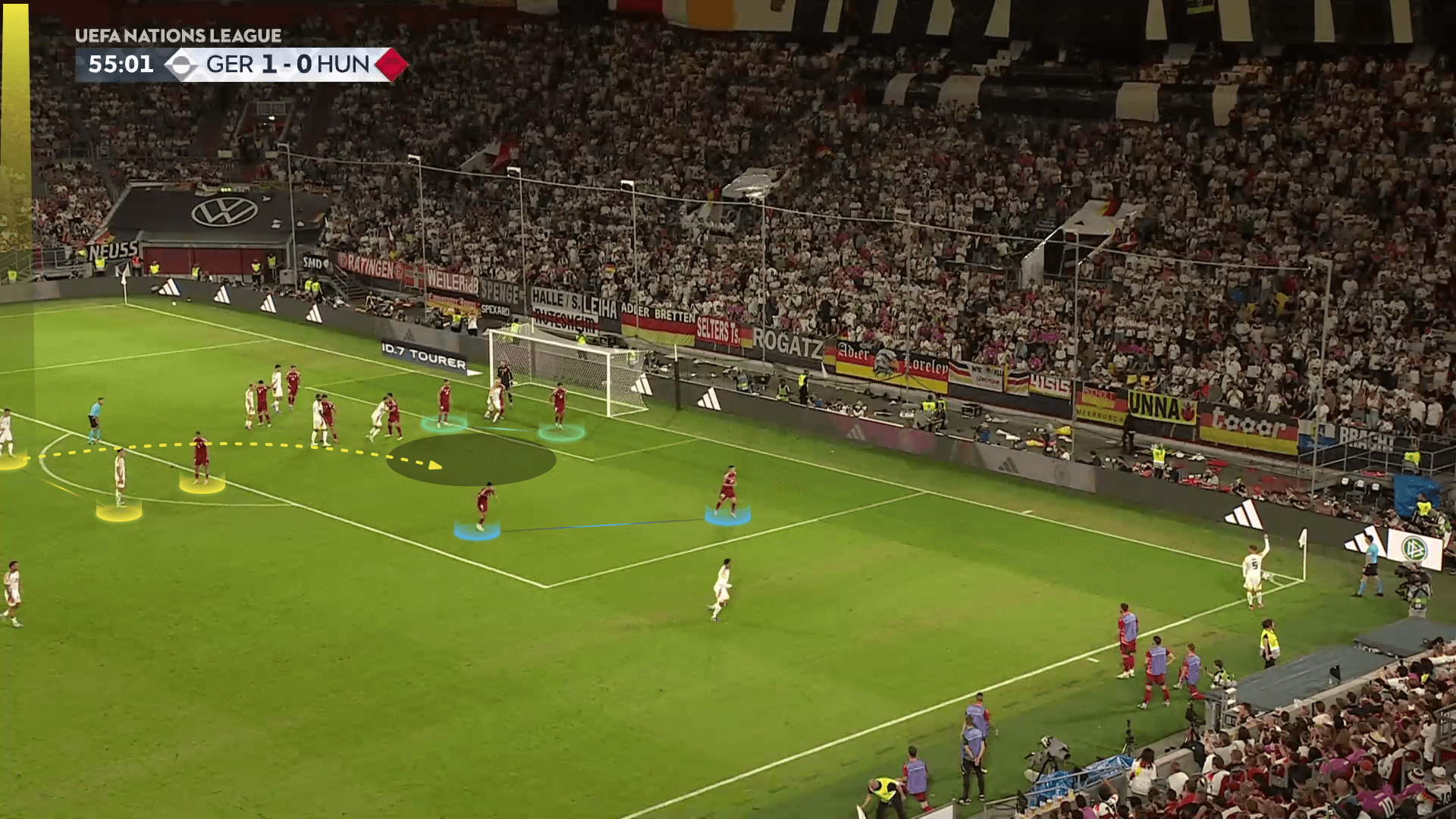

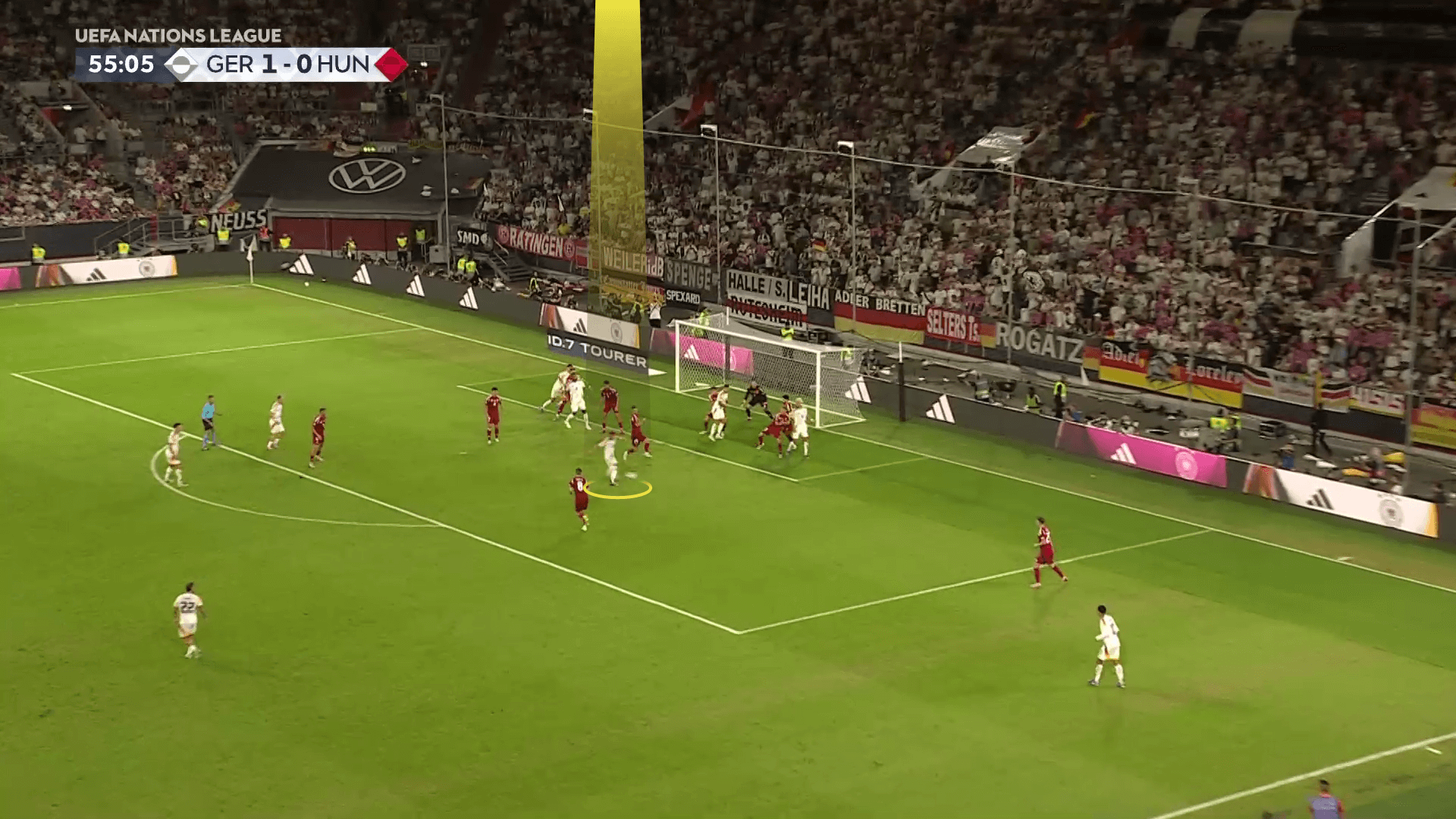

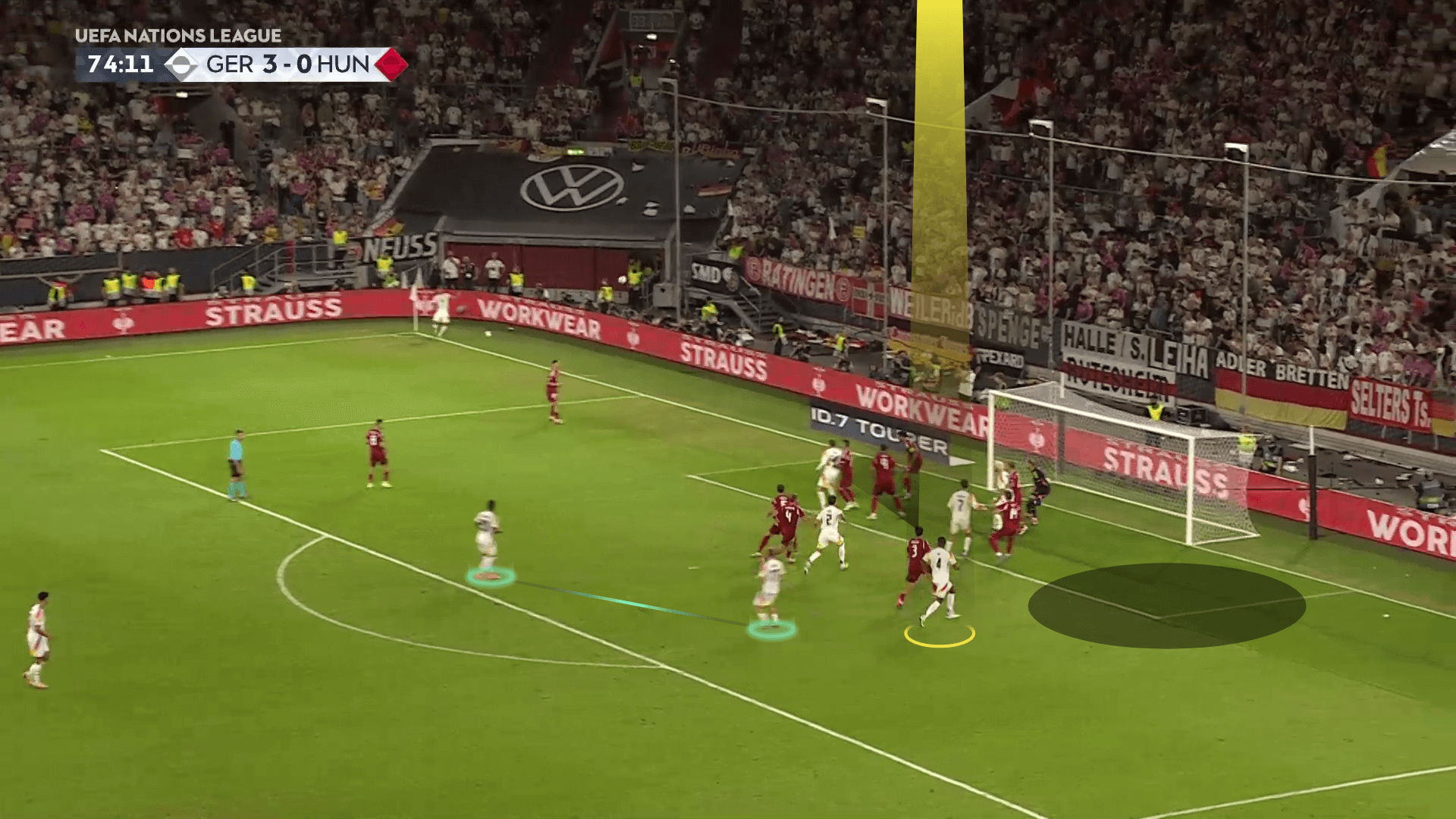

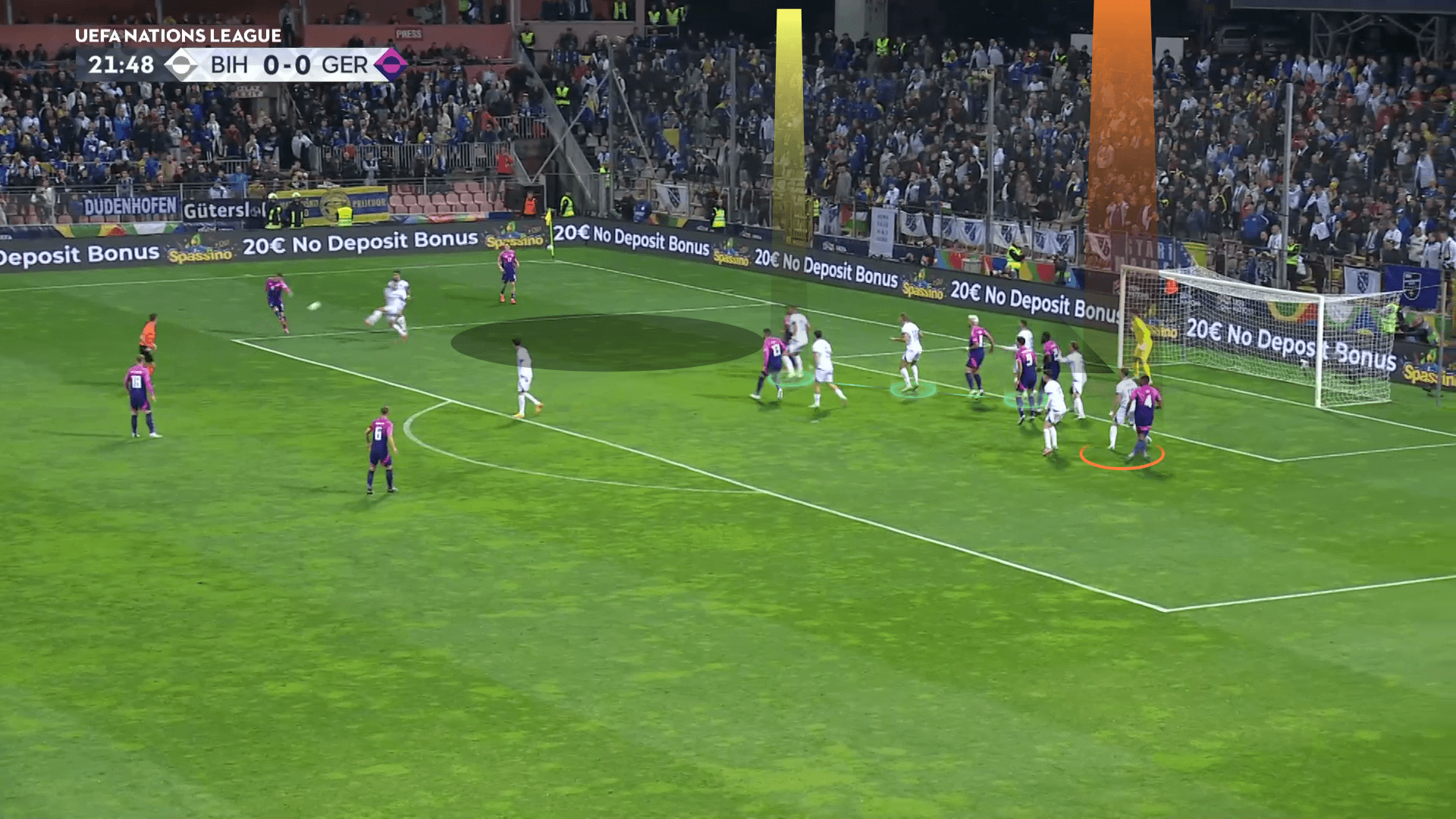

As shown below, Hungary defends with a man-marking system, with only two zonal defenders (green) and two short-option defenders (blue), to prepare for the 2v2 situation for which Germany is famous, as we will discuss later.

To start explaining any routine, it is important to tell you who the targeted player is and where the targeted area is so it is shown that the yellow-highlighted player will attack the black circle with a grounded pass.

To hide their intentions, Germany asks Nico Schlotterbeck (yellow) to start in the rebound zone next to the targeted player.

This drags the marker, who will focus on Schlotterbeck, neglecting the targeted player who pretends to just wait for the second ball.

To implement this plan, we have many obstacles; let’s clarify them step by step.

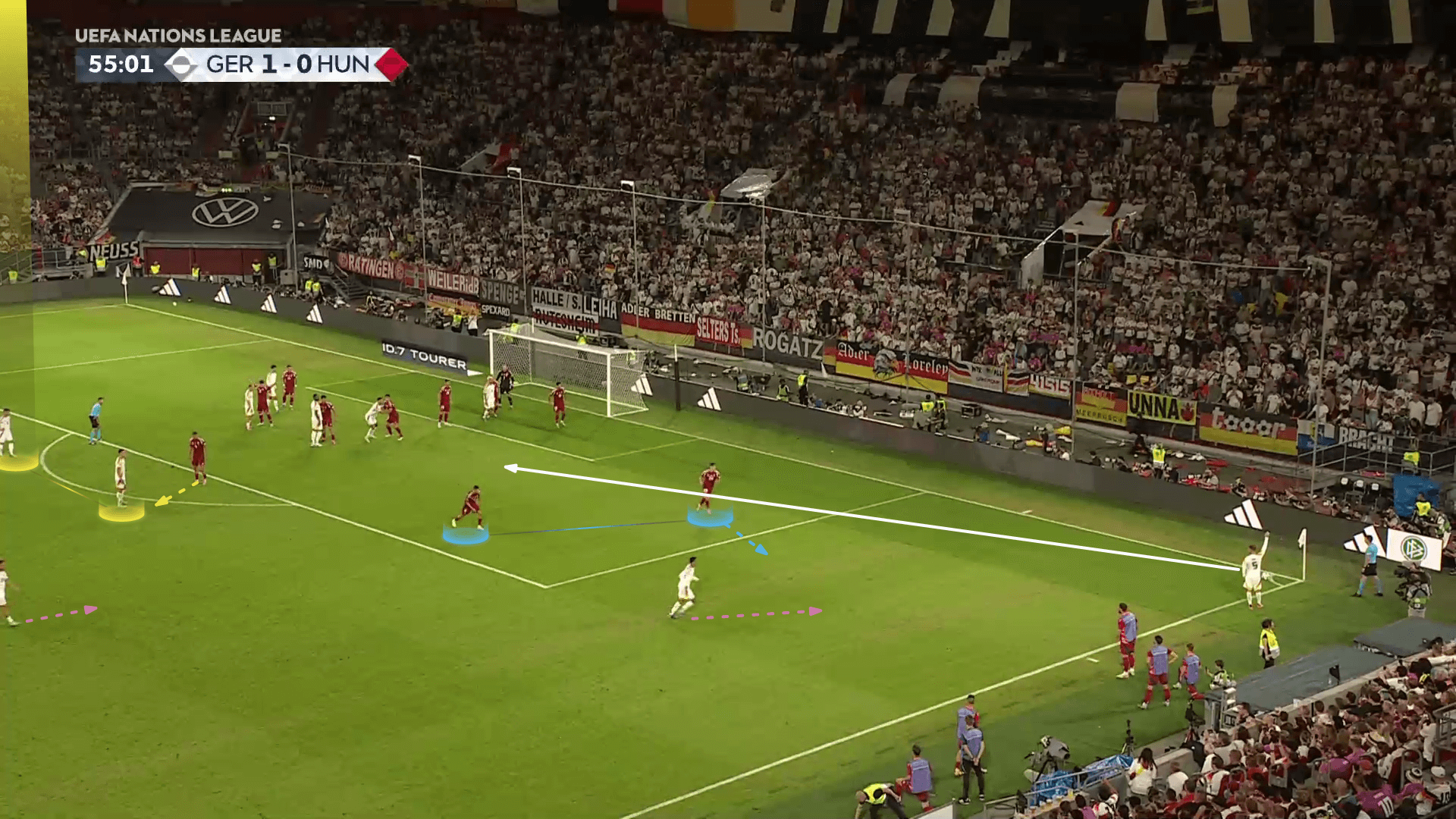

As shown below, the first obstacle naturally is opening the lane for the pass itself, so Jamal Musiala (pink) runs towards the taker, pretending that he will receive a short pass to make the first short-option defender move forward to open this flat passing lane.

This also motivates the second short-option defender to get nearer and not stand in the rebound zone.

These disguising movements open the flat passing lane and distract the targeted player and area.

Now, we come to the second obstacle: the two zonal defenders who can move toward the targeted area when they realise the idea.

As shown below, a player (yellow) moves from the first zonal defender to block him or at least distract his attention, while another one (pink) runs in front of the second zonal defender to take his attention.

Not to leave anything to chance, they asked a player (orange) to step back and replace the targeted player as a rebound defender.

The two blue players push their markers forward, far away from the targeted area.

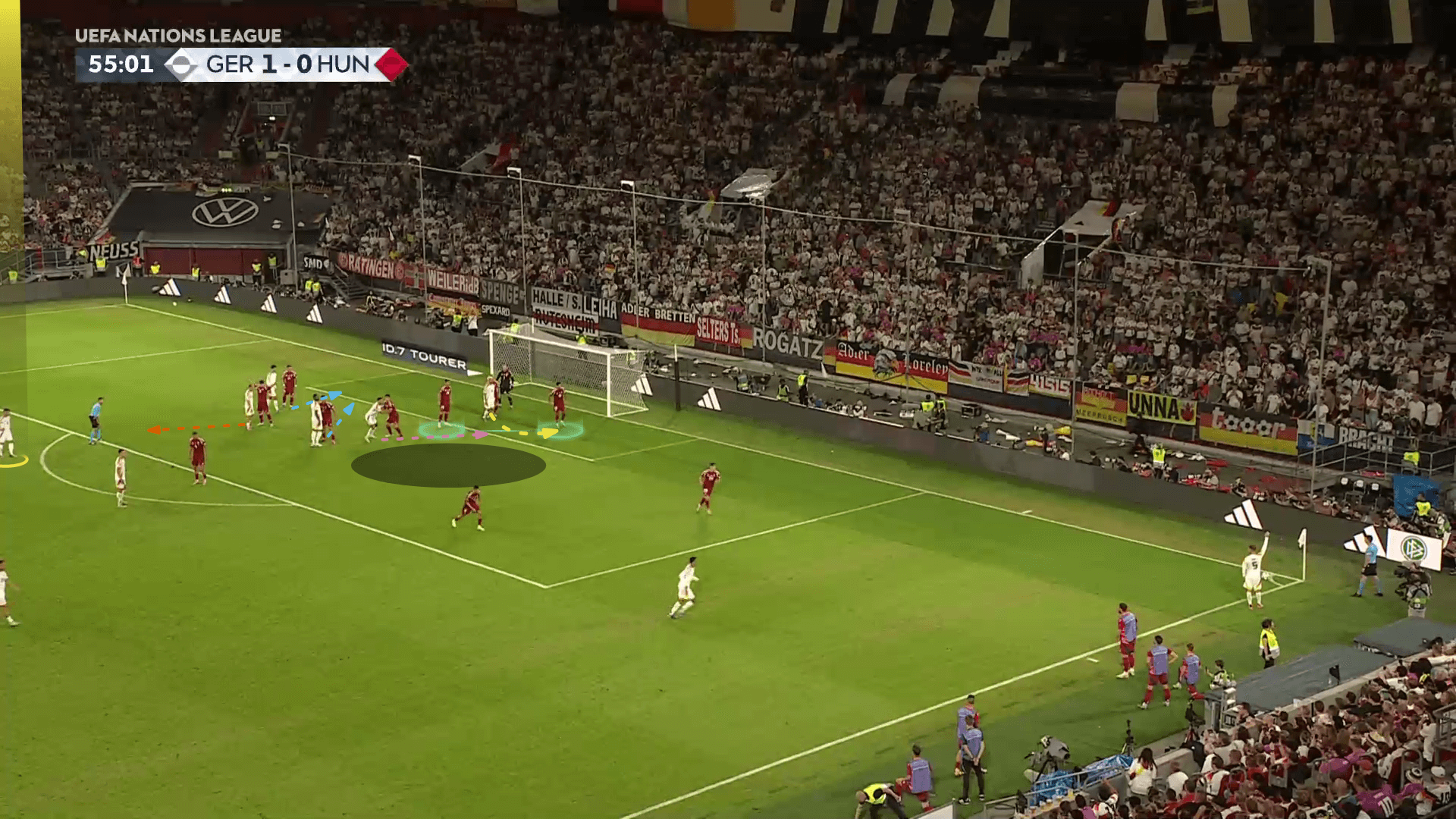

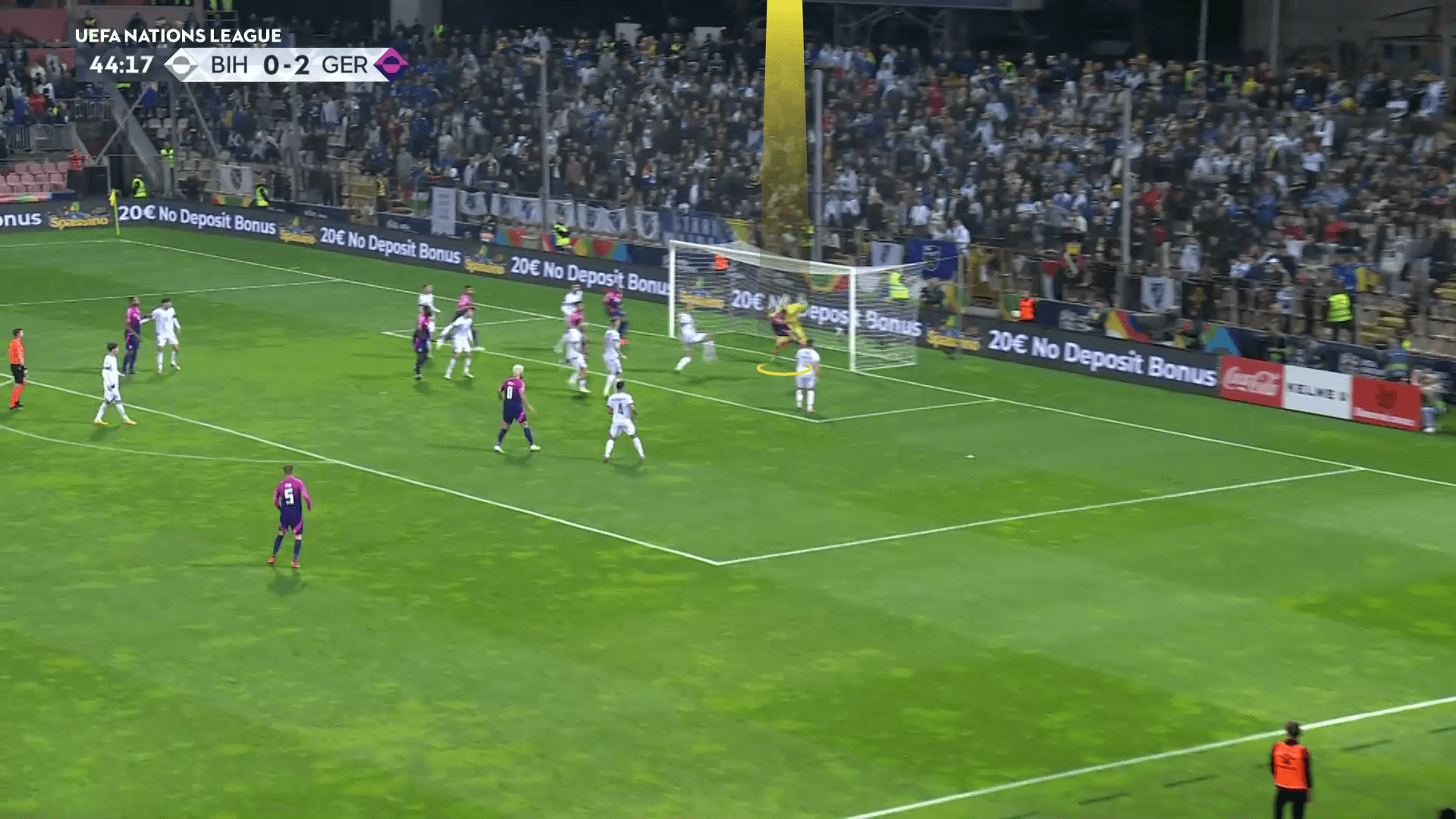

As shown below, everything is okay; we are waiting for the grounded pass.

The plan works, but Joshua Kimmich strangely shoots wide, as shown below.

Far-Post Tactics

The second routine they implemented in the same match was to target the far post with unique ideas.

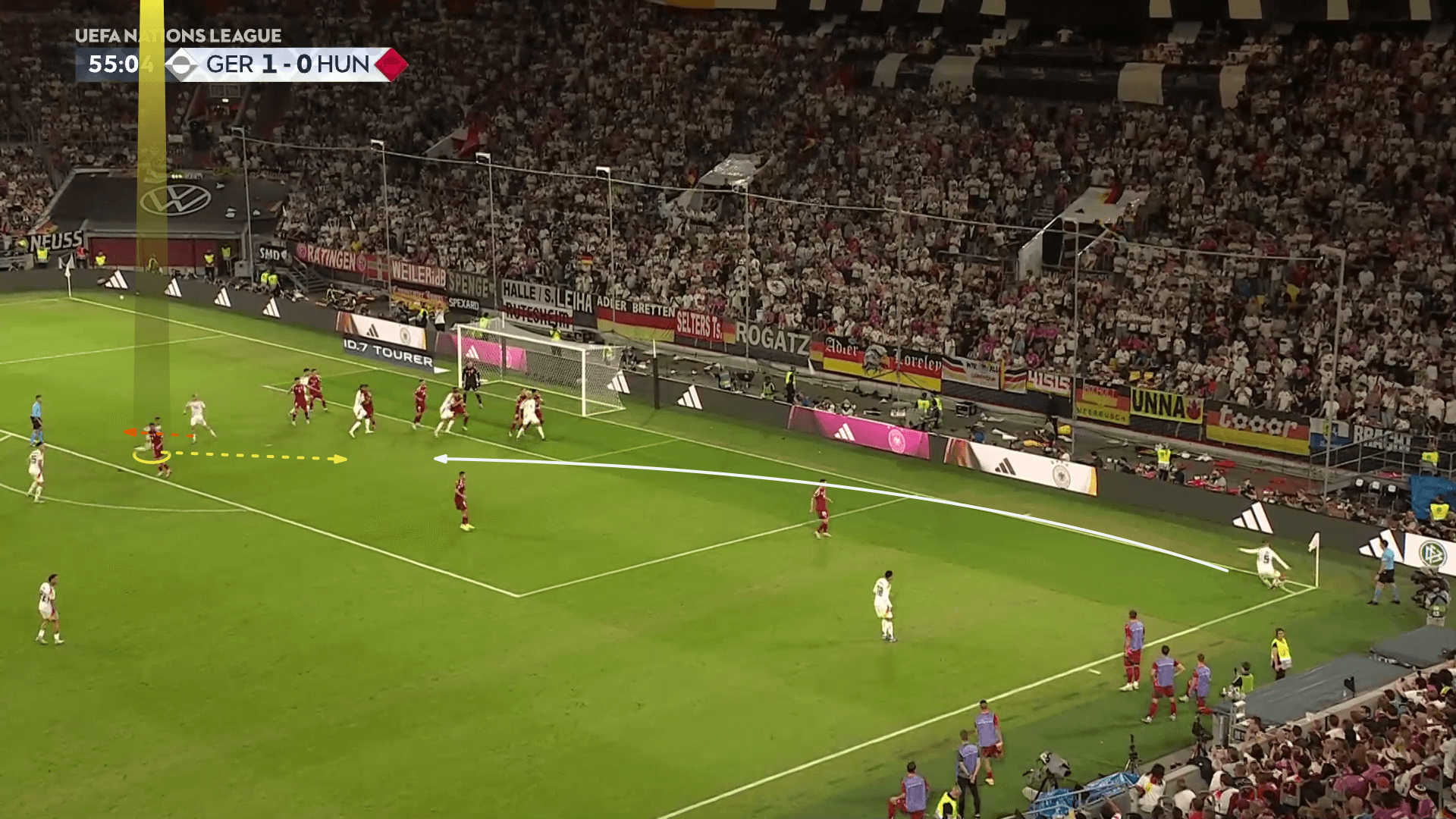

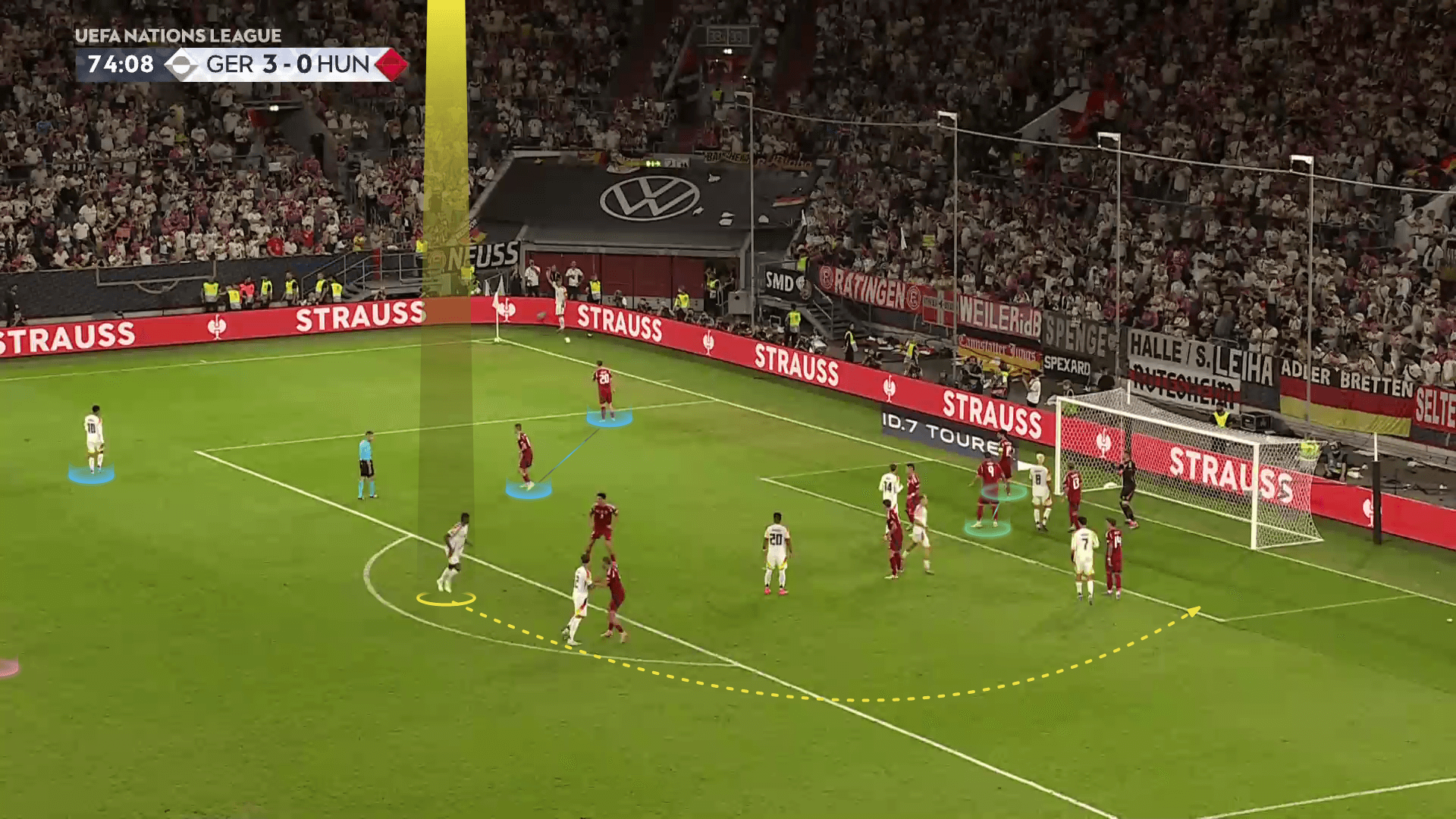

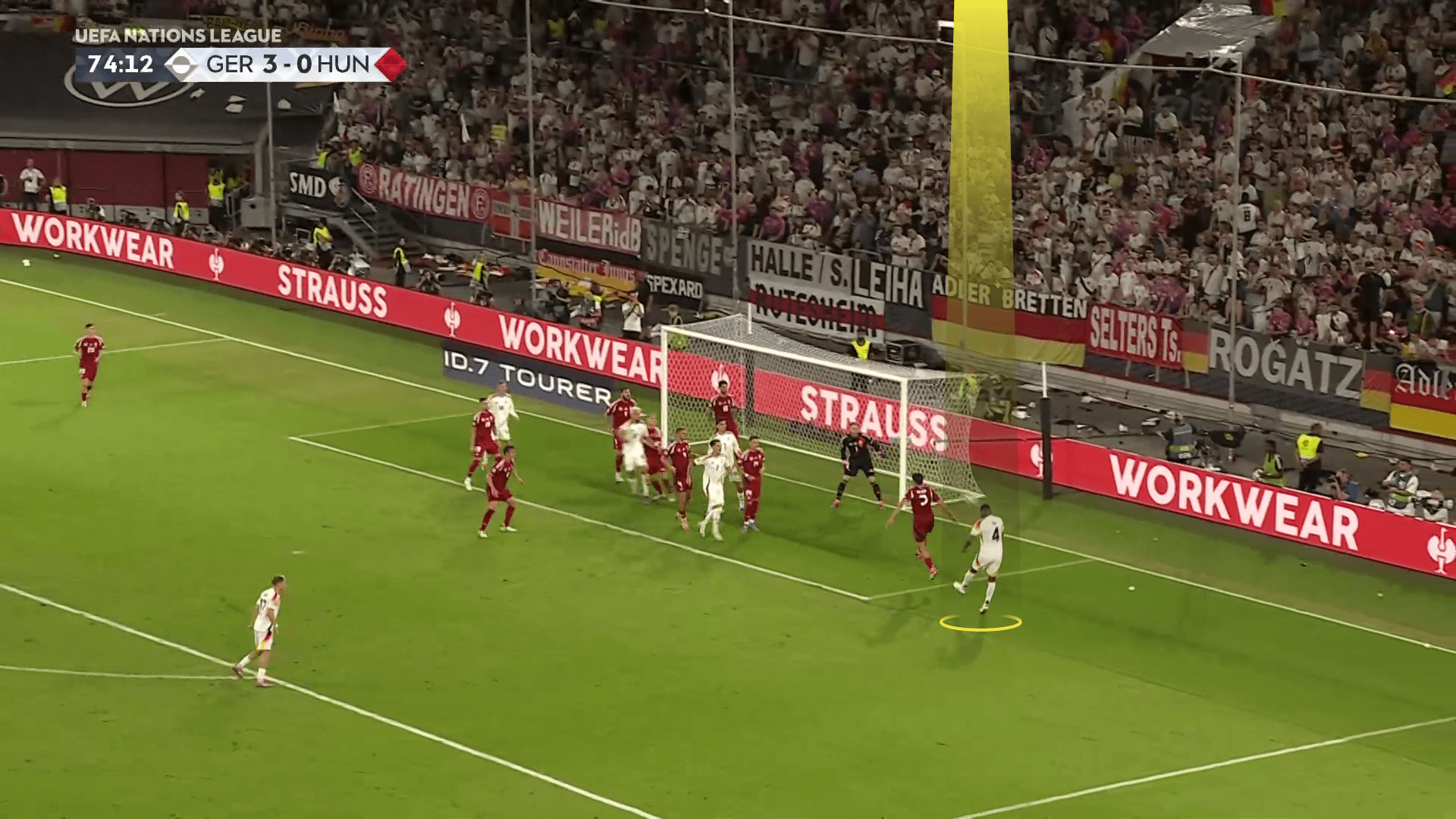

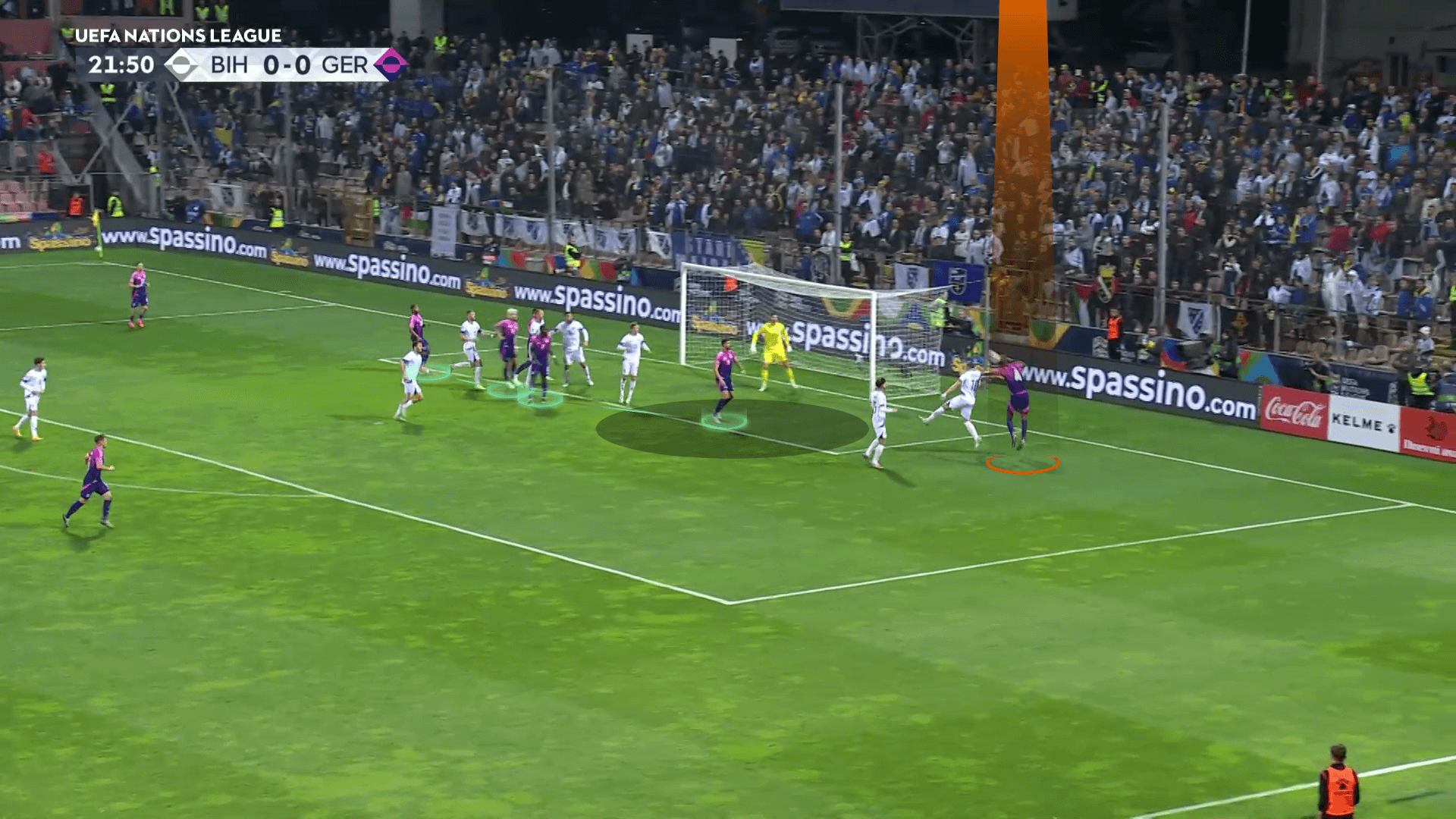

As shown below, Hungary still defends with the same scheme while the targeted player is Jonathan Tah, attacking the far post.

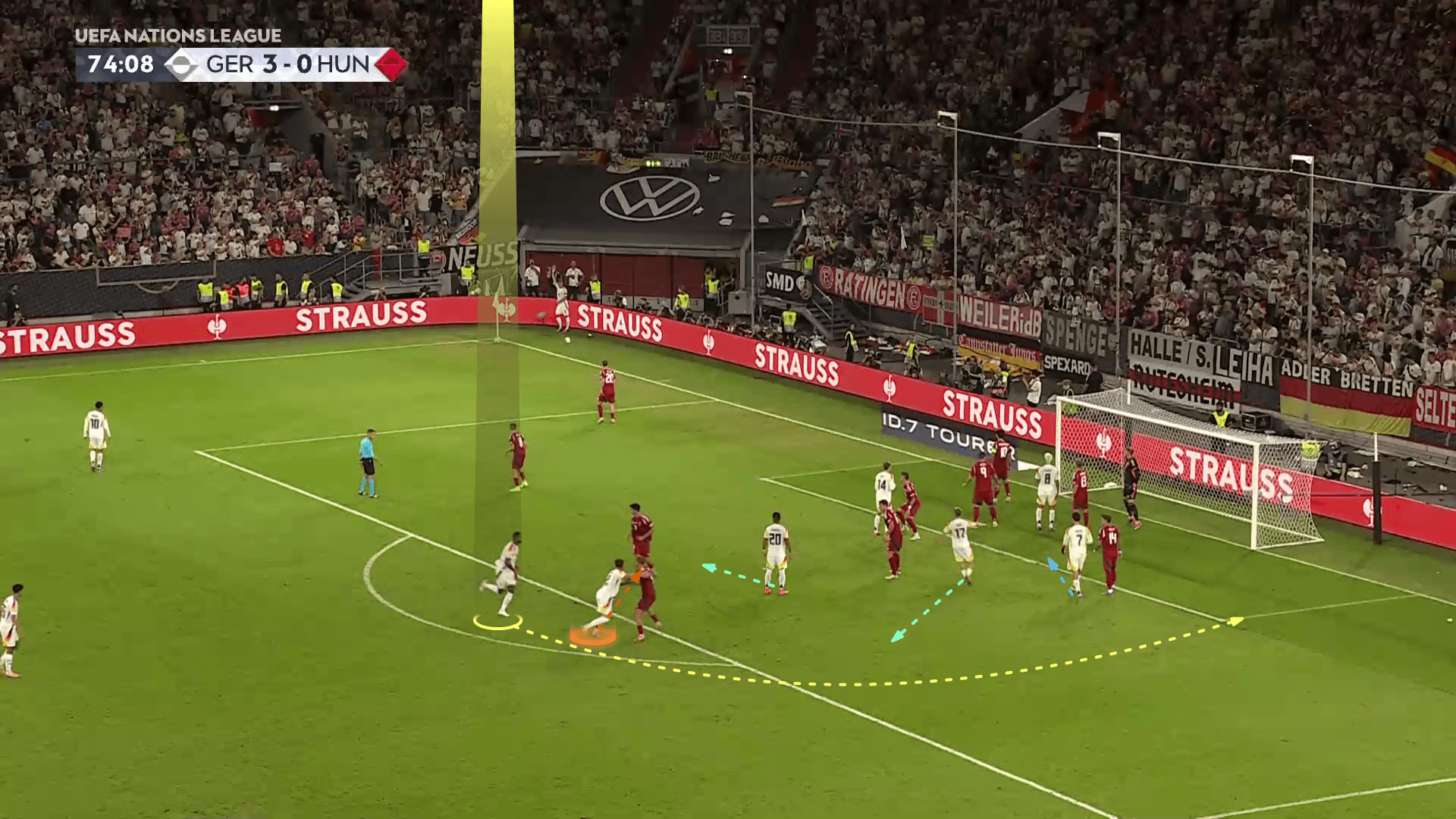

As shown below, Germany put two strong players on the edge of the box in the beginning (Jonathan Tah and Nico Schlotterbeck) — not only one, as in the previous case.

Two green (Florian Wirtz and Benjamin Henrichs) players will go to defend the rebound instead of them, but why?

First, Tah’s long path makes it difficult for his marker to track him all this way while tracking the ball in the air, so he must lose contact with one of them; this is called an orientation problem.

Secondly, Benjamin Henrichs (orange) goes to block Tah’s marker while Tah turns around him, which is called a screen, as in basketball.

The three remaining attackers around the six-yard box wait for Tah’s headed pass, noting that Kai Havertz (blue) starts in the targeted area and then runs inside to empty it as a kind of camouflage.

The screen is shown below.

The marker can easily escape from the screen, but he faces the orientation problem we discussed, so he loses contact with Tah while looking at the ball.

The plan works, so Tah reaches the targeted area, or quite far because of the overhit cross, while his teammates frame the goal, waiting for the headed pass.

The plan works, leading to a dangerous chance.

Germany’s Tactics Against Hybrid Systems

Now, we move to explain what they do against hybrid systems (a mix of zonal and man-marking with many zonal players), showing how and when they utilise in-swinging or out-swinging crosses.

In-Swinging Crosses Tactics

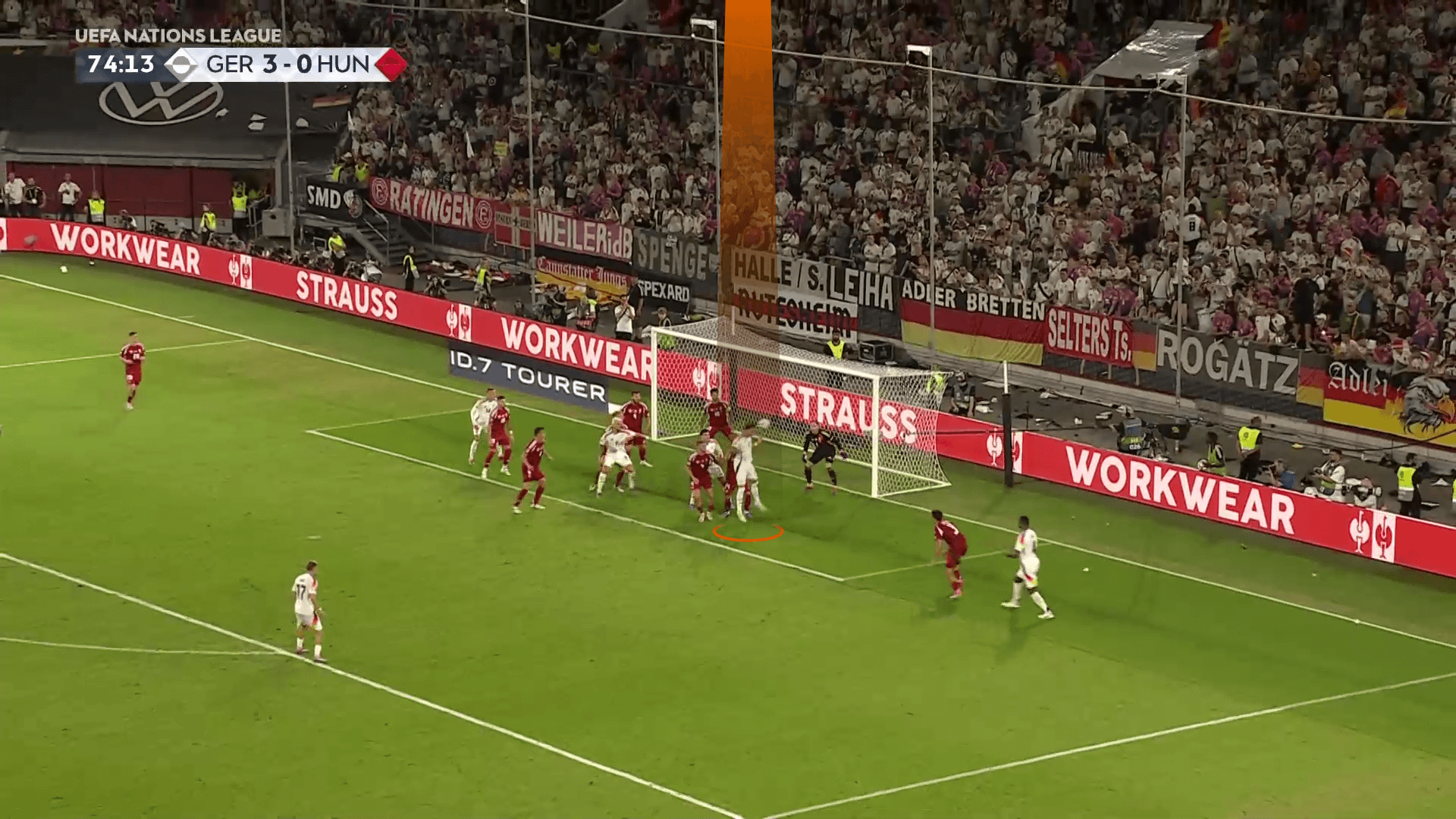

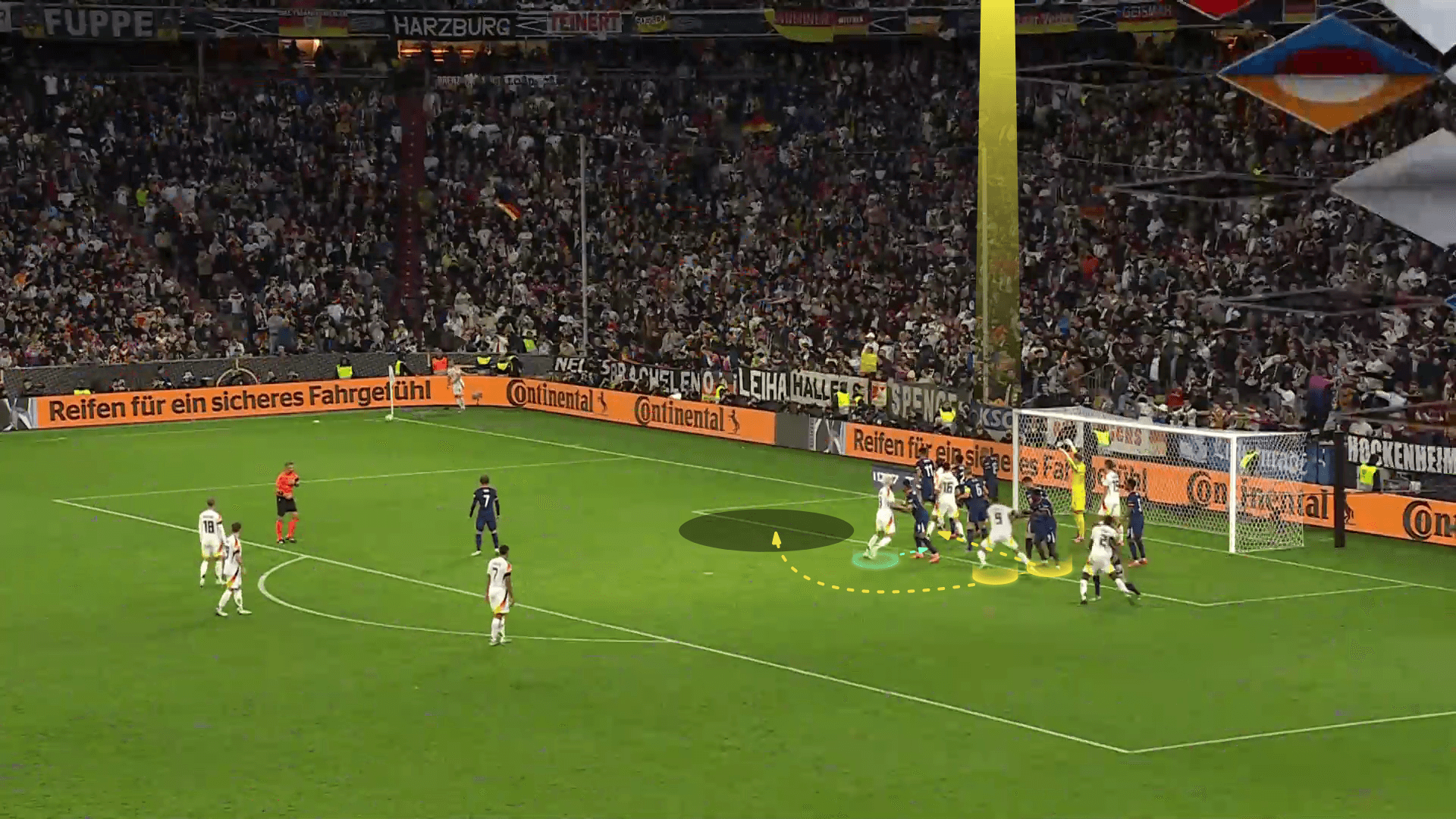

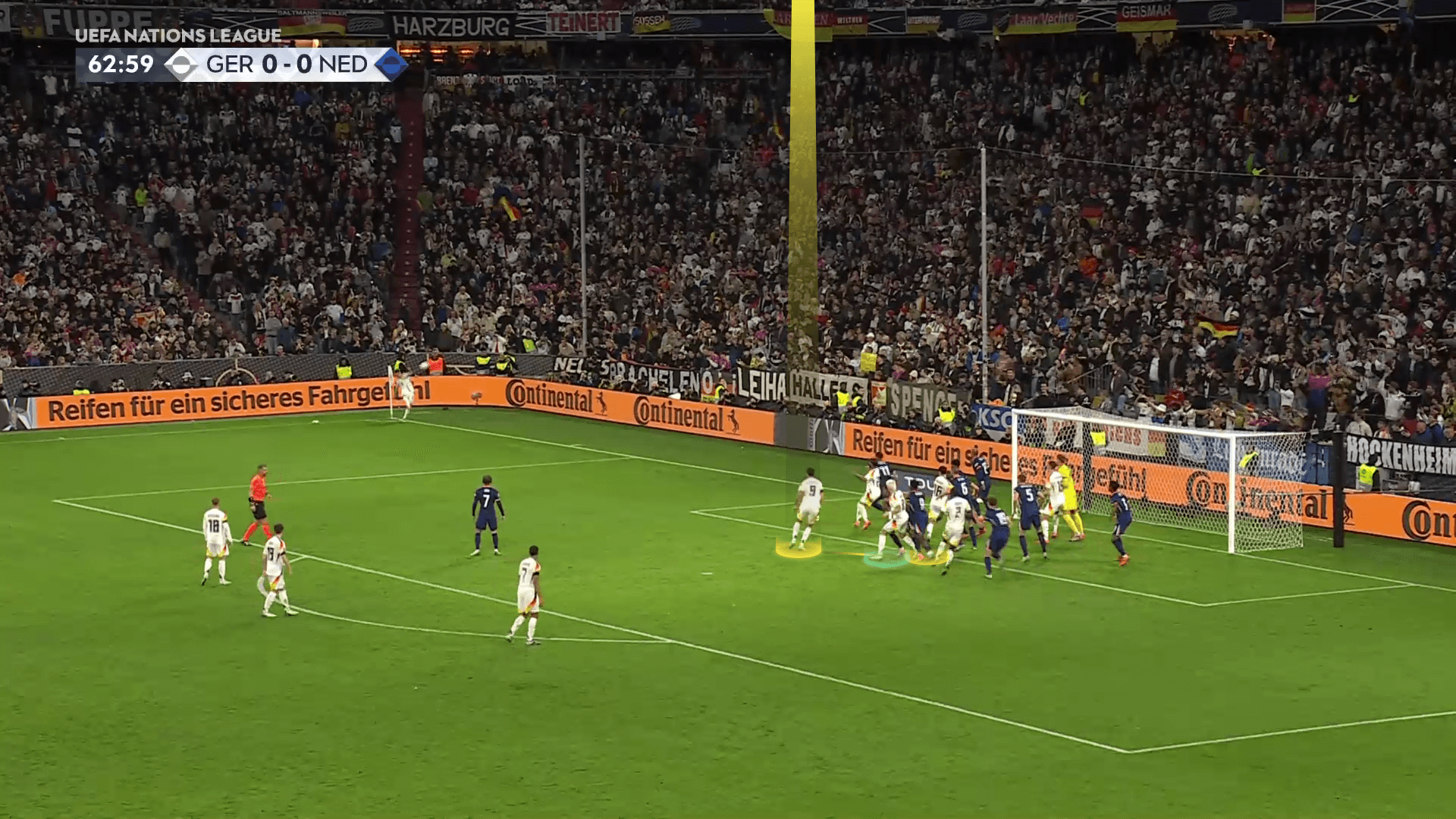

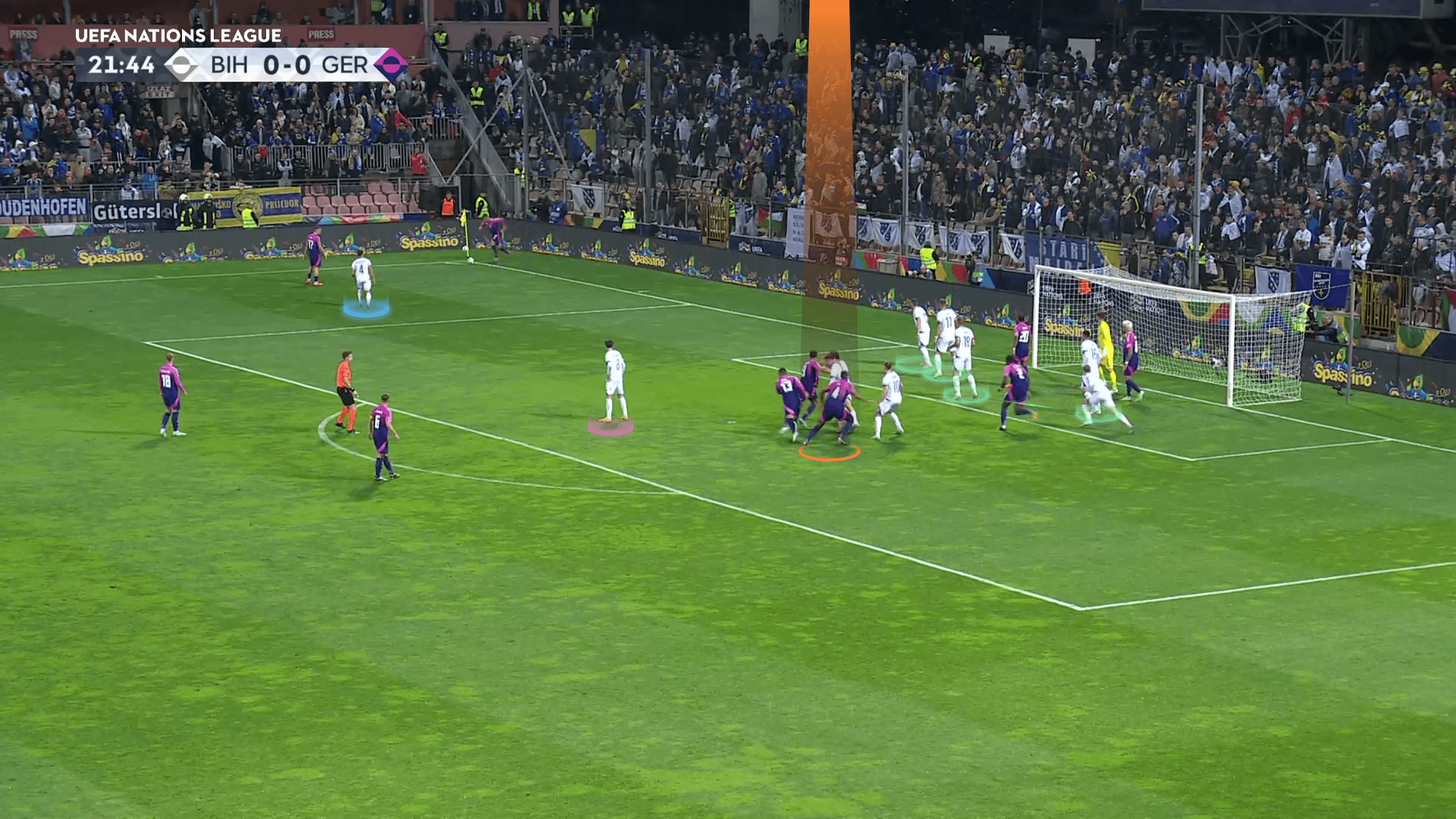

As shown below, Netherlands defend with six zonal defenders (green), three-man markers (yellow) and a rebound defender (pink).

Against this tough scheme, it is hard to target the well-protected six-yard, especially since the Netherlands have so many amazing players in aerial duels.

Therefore, Germany decided to send an in-swinging cross to the edge of the six-yard box in front of the near post by motivating the zonal line to shrink inward using two factors:

1- The expected in-swinging cross gives the impression that the ball will swerve inward, which makes the zonal line inclined toward the inside of the six-yard box.

2- Ask the three free players to start inside the six-yard box behind the zonal line to attract them more inside.

We want to target the yellow-highlighted player in the shown area, so we should free him from his marker and ensure the two zonal defenders near that area won’t enter it.

First, the targeted player (yellow) turns around his teammate (green) to use him as a screen, so he pushes his marker and runs to the targeted area suddenly after the sign.

When his marker decides to follow him, he finds his green teammate in his way.

The screen is done perfectly, as shown below.

In the two photos below, you can see the role of the three players inside the six-yard line: one blocks the goalkeeper, while the other two players block the two zonal defenders near the targeted area.

The plan worked, ending with a goal after a rebound shot.

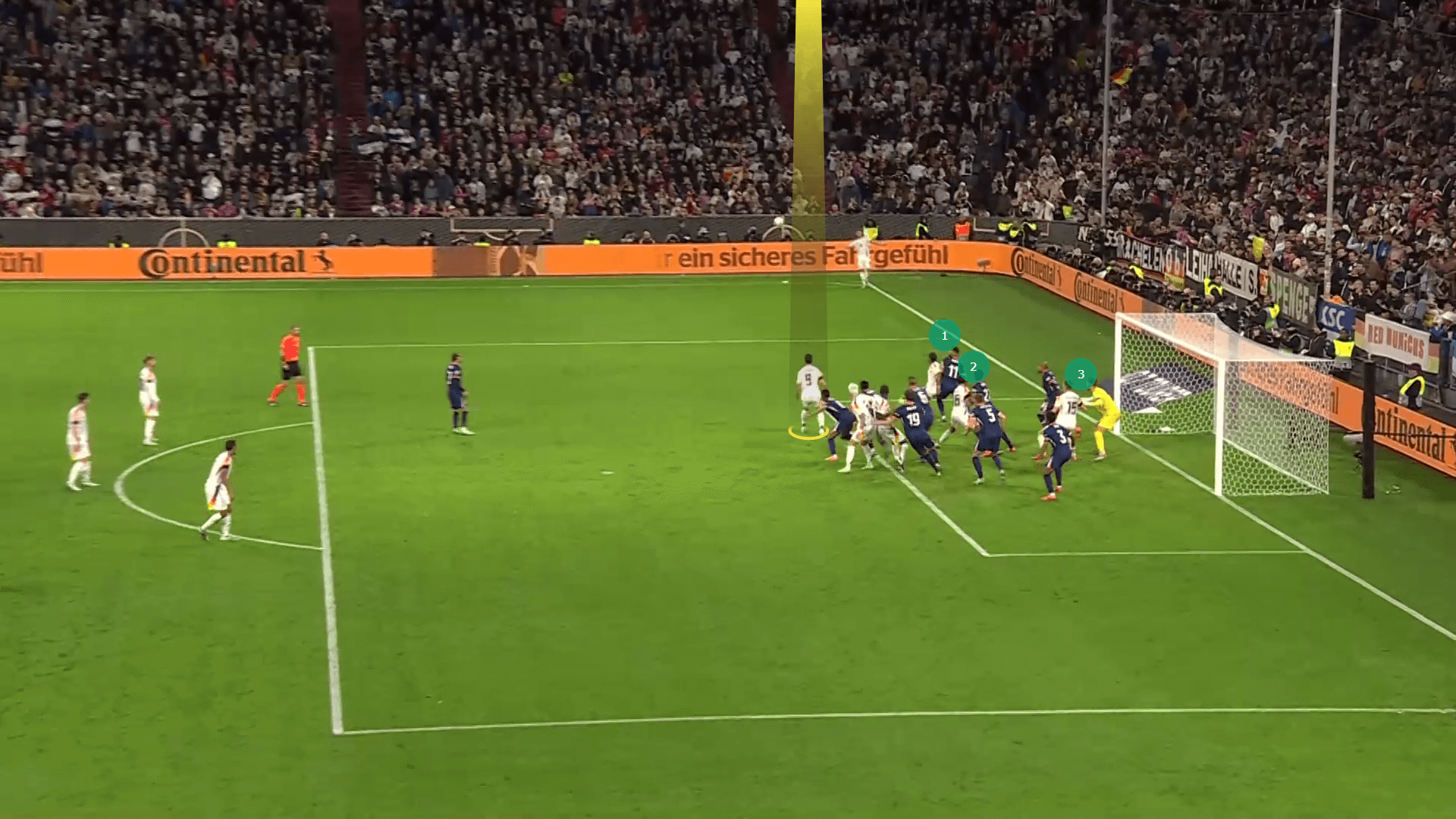

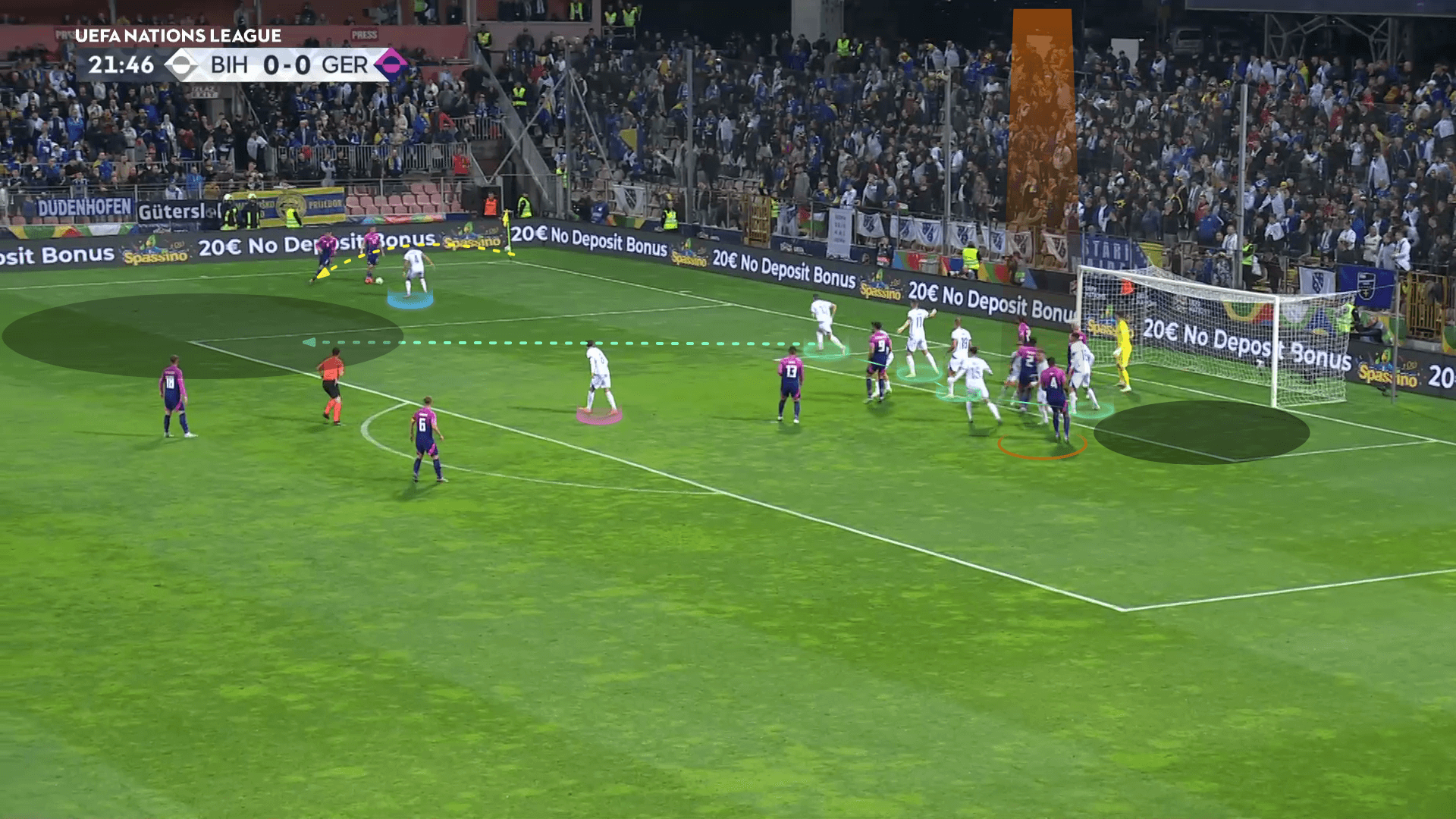

Out-Swinging Crosses Tactics

When they faced a team that exaggerated the outward positions of the zonal line against expected out-swinging crosses, they had an excellent plan to target the area stuck to the near post.

As shown below, the opponent defends with four zonal defenders (green) inclined, leaving a huge space between the line and the goal because of the expected out-swinging cross.

The three free players have other roles in this case:

1- The first one (orange) makes a deceptive run to drag the first zonal player, ensuring he won’t cut the cross.

2- The targeted player (yellow) runs suddenly from the blind side of the third zonal defender.

3- The last one (black) goes to the far post to frame the goal in case the targeted player flicked the ball or to be ready for the rebound if the goalkeeper saved it.

The process is shown below.

The plan works brilliantly, but Wirtz sends the ball over the bar.

Here, we have some advice: Make the cross at a lower level to be played with the leg because the free player is naturally not good at aerial duels, as Manchester City did against Liverpool in this analysis.

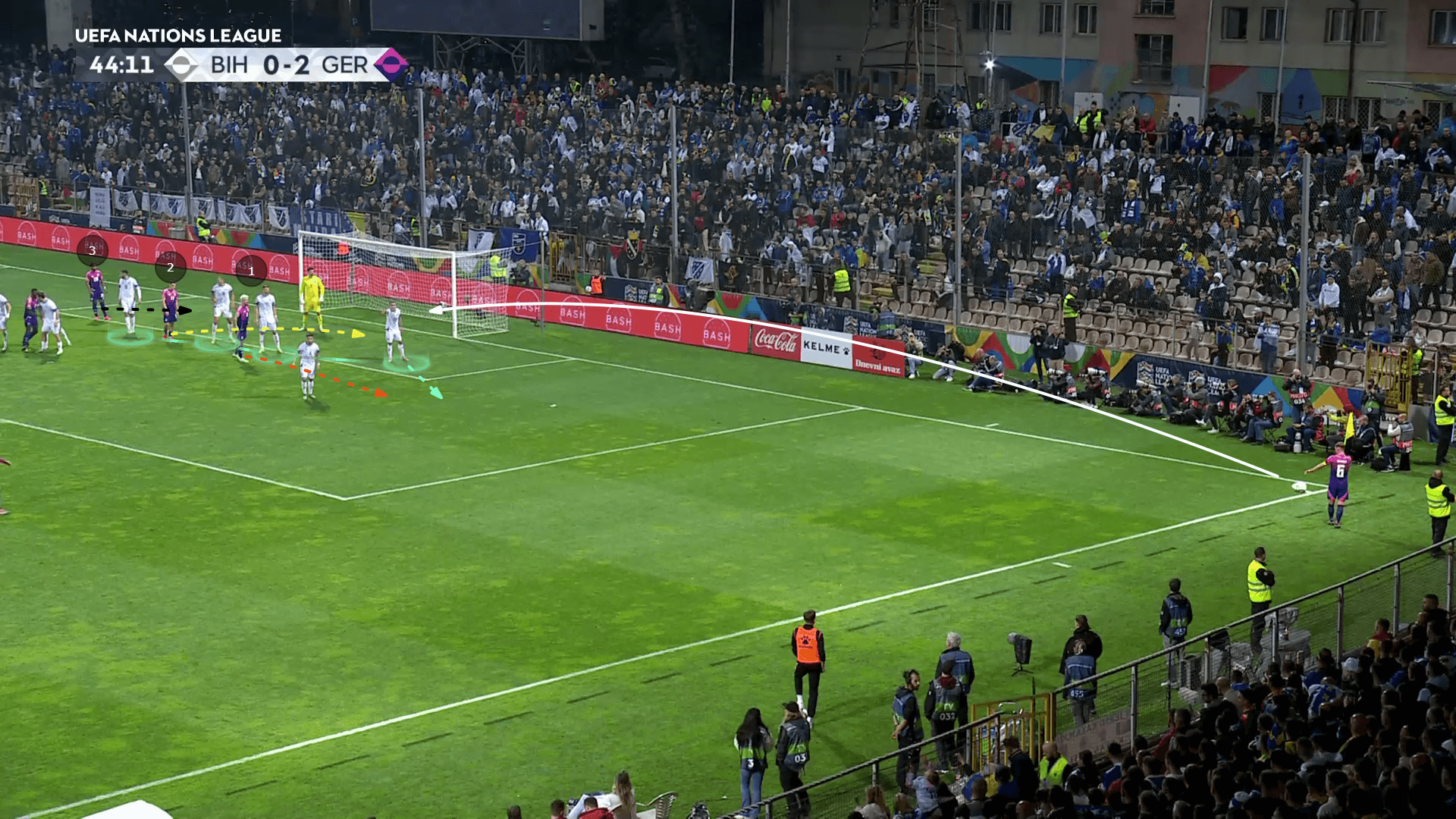

Short Corners

They also have many short-corner variations using the overlap.

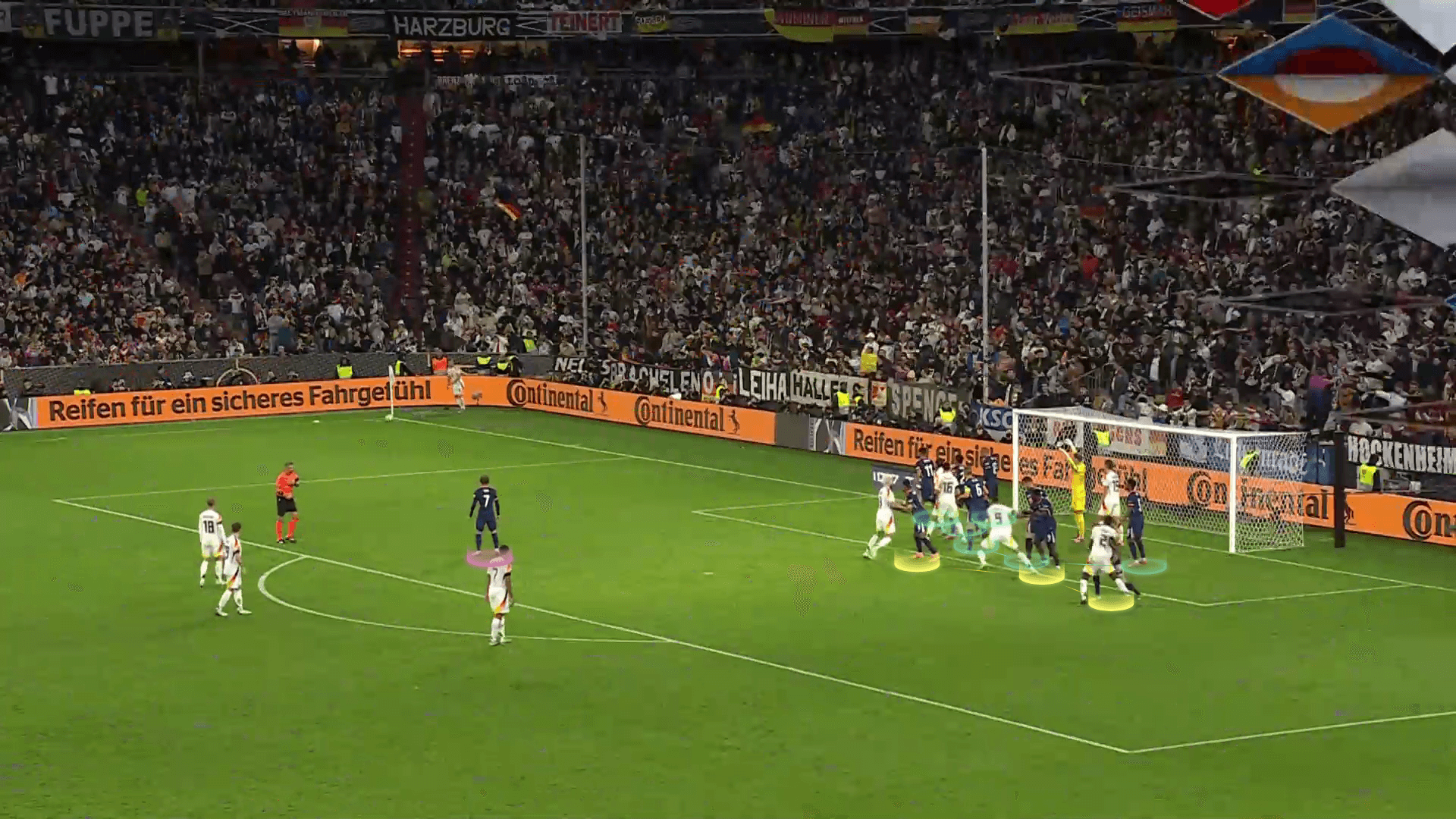

In the photo below, the opponent defends with four zonal defenders (green), a short-option defender (blue), a rebound defender (pink), and four-man markers.

The targeted player (orange) will target the far post.

He utilises the usual disorganised movement up from most of the defensive zonal lines after the short corner is played while exploiting the orientation problem that happens to the marker, focusing on the ball movement.

At the same time, his attacker targets his blind side.

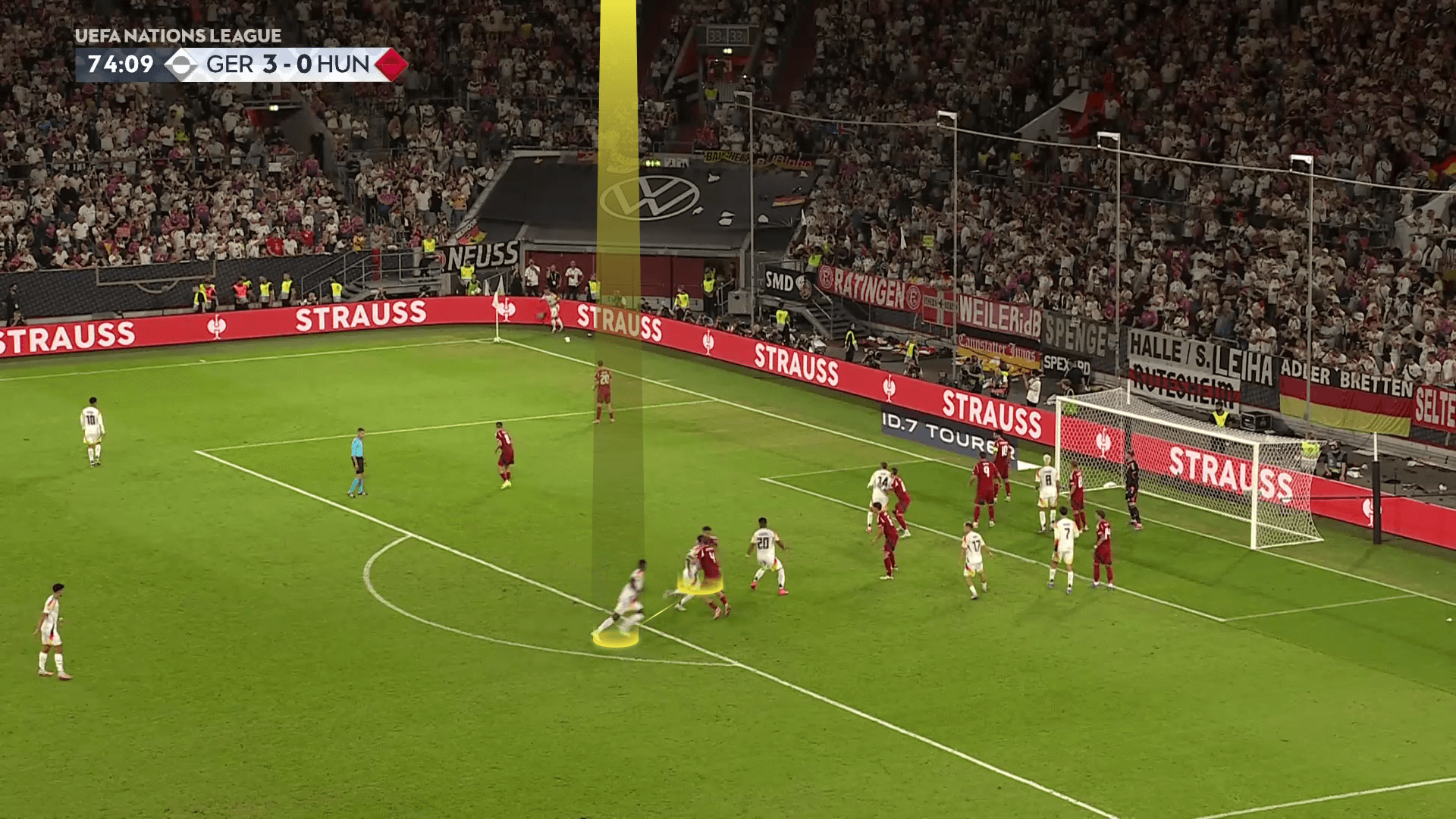

As shown below, the taker passes the ball to the short-option attacker and then overlaps him.

This overlap causes a quick 2v1 situation against the lonely short-option defender, so the first zonal defender goes to help.

Still, the distance is so large that he will take a long time while the rebound player (pink) is fixed by two players standing on the edge of the box.

If this rebound defender decided to help, the ball would played to a player on the edge of the box, especially since they have good shooters like Musiala and Wirtz.

At the same time, chaos begins inside the box with fake movements toward the near post, making the zonal line shift forward while moving up so the targeted player can target their blind side.

Now, his marker sees him, but when he decides to take a look at the ball after that, he will lose him.

As shown below, the cross is sent from a close and dangerous position, while the orientation problem happens to the man marker.

The three zonal defenders focus on the ball, shifting more toward the near post.

As a note, the yellow-highlighted player has a key role.

He doesn’t just motivate the line to shift toward the ball to empty the far post but also takes the attention of this zonal defender not to go to help fill that shown space, which can be exploited as an alternative plan.

The plan works while the other players frame the goal, as shown below.

Conclusion

In this analysis, we have shown how Germany under Julian Nagelsmann’s coaching style have been dangerous in set-pieces, especially corners.

Under Mads Buttgereit’s set-piece tactics, Germany has shown good ideas and potential to improve in the future.

In this set-piece analysis, we have also shown how Germany behaved against different kinds of defending systems they faced, including man-marking and hybrid defending systems, and how they were creative, having many variations to surprise the opponent.

Comments