The oldest football competition in the world returned last weekend. Last Sunday, the King Power Stadium hosted the arguably most awaited FA Cup quarterfinals match of this season: Leicester City versus Chelsea. Both teams are only separated by one point in the Premier League at the moment. A win would almost definitely boost the much-needed moral for the finishing stage of the season.

Despite playing at home, the home side couldn’t capitalise on the advantage. It means that Leicester have to continue their winless streak in this Project Restart with two draws and one defeat. Oppositely, Chelsea successfully continued their winning habit with an important goal from Ross Barkley. Without further ado, this tactical analysis will inform how the match unfolded with the help of some supported sites.

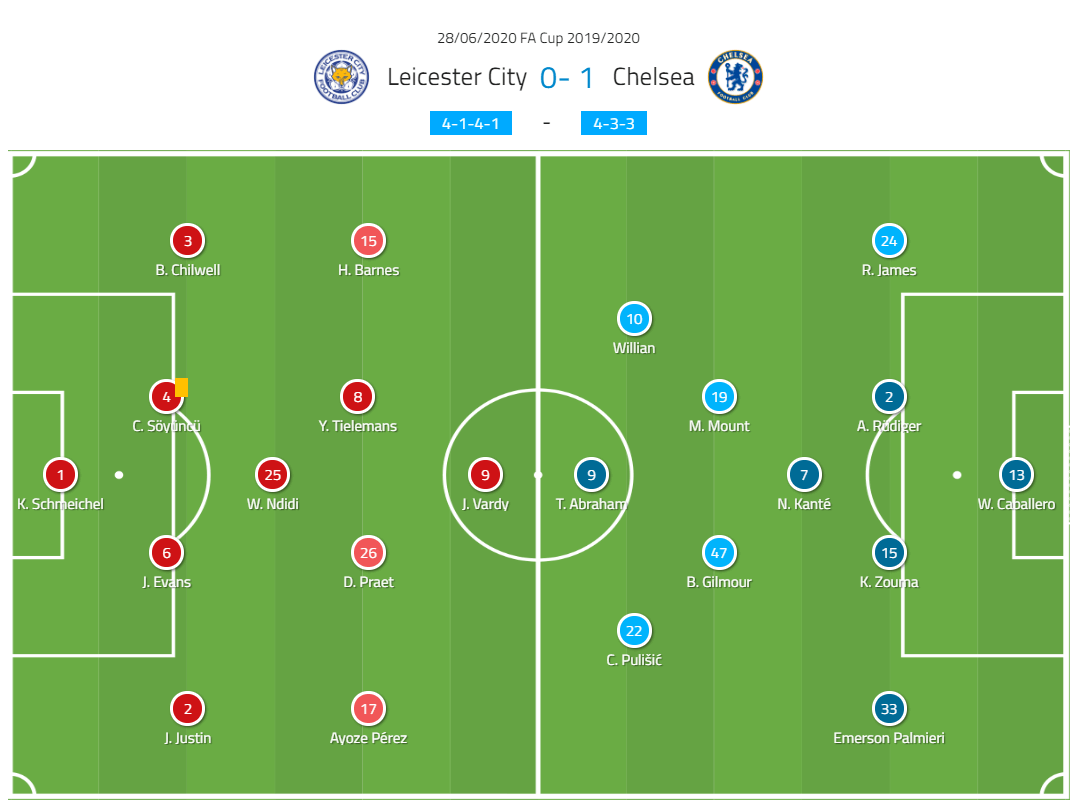

Lineups

Brendan Rodgers opted for the usual 4–1–4–1 for his team. The duo of Jonny Evans and Çağlar Söyüncü started in the heart of Leicester’s defensive department with James Justin and Ben Chilwell flanked them. Upfront, talisman Jamie Vardy was supported by Ayoze Pérez and Harvey Barnes to lead Leicester’s attacking line. Names like Demarai Gray, Marc Albrighton, and Hamza Choudhury had to start the match from the bench.

In the opposite side, Frank Lampard chose 4–3–3 as Chelsea’s main shape. N’Golo Kanté was chosen to be the central defensive midfielder, with youngsters Mason Mount and Billy Gilmour alongside him. The Blues’ frontline for this match consisted of Willian, Tammy Abraham, and former Borussia Dortmund player Christian Pulisic. Their dugout was filled by players like César Azpilicueta, Barkley, Mateo Kovačić, and three-time Champions League winner Pedro Rodríguez.

The Foxes’ aggression

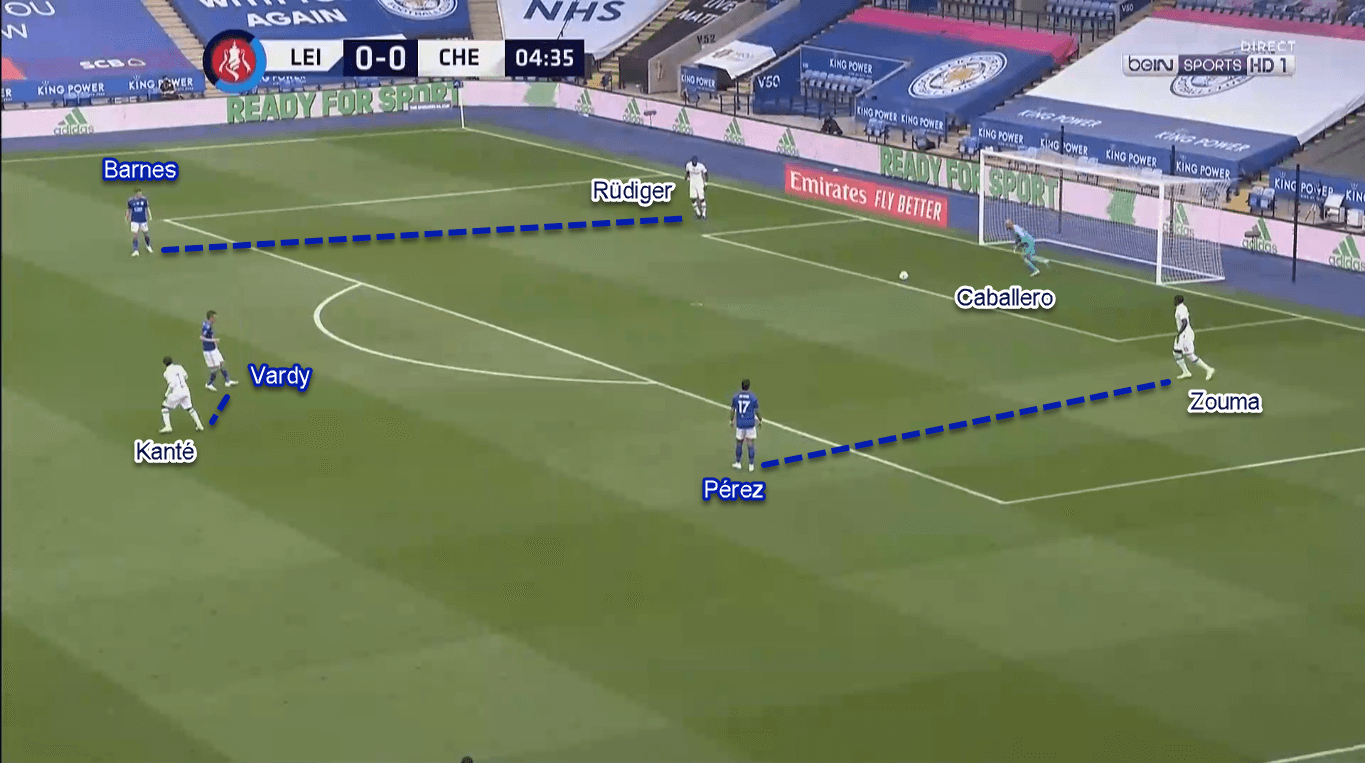

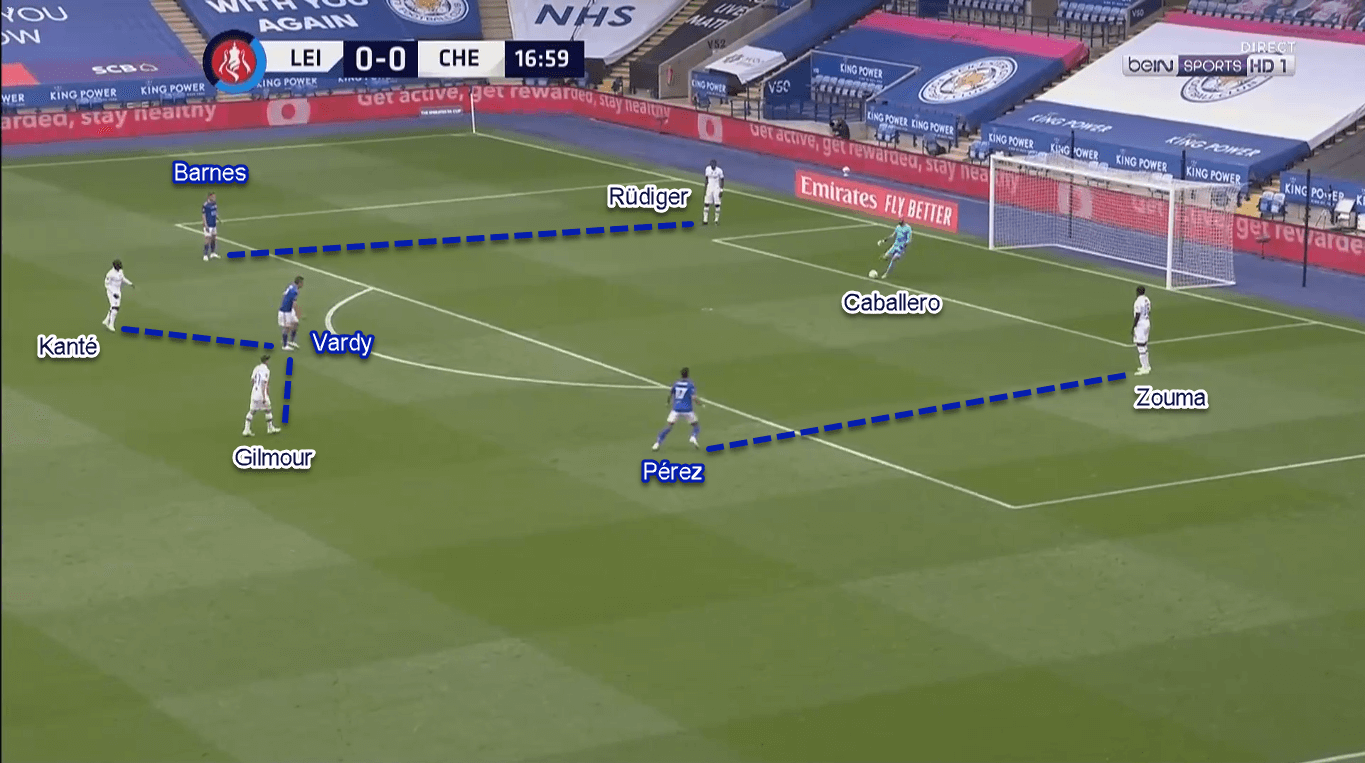

This first part of the analysis will explain of Leicester’s aggressive defending tactics. As expected, Leicester deployed their high-pressing game since the first minute. They used 4–1–2–3/4–3–3 shape as their main pressing shape, with the wingers tucking inside alongside Vardy. In their high-press, The Filberts tried to close all nearby passing options for Willy Caballero. The task distributions were as follow:

Centre-forward Vardy was instructed to close down Kanté in the middle. In the process, he would stand in front of the Frenchman so the passing lane got fully closed. If Lampard asked one of his midfielders to drop alongside Kanté (mostly Gilmour), Vardy then would move in between the two opponents. The objective stayed the same: prevent the midfielder(s) to be accessed in the build-up.

The next important feature of Leicester’s high-pressing game was their wingers. Instead of staying wide, they would come to nearby Vardy and stand just outside of Chelsea’s penalty box. The ball-side winger then was tasked to press The Blues’ centre-back immediately if Caballero tried to play short.

Behind the attacking trident, Leicester’s midfield trio stayed put. They would only move when the ball has played, especially to the wide area. As Leicester were focusing their press centrally, they would leave the flanks open. If Chelsea tried to access their full-backs, then The Foxes’ ball-side midfielder would step wide and press the on-ball defender.

Chelsea’s response

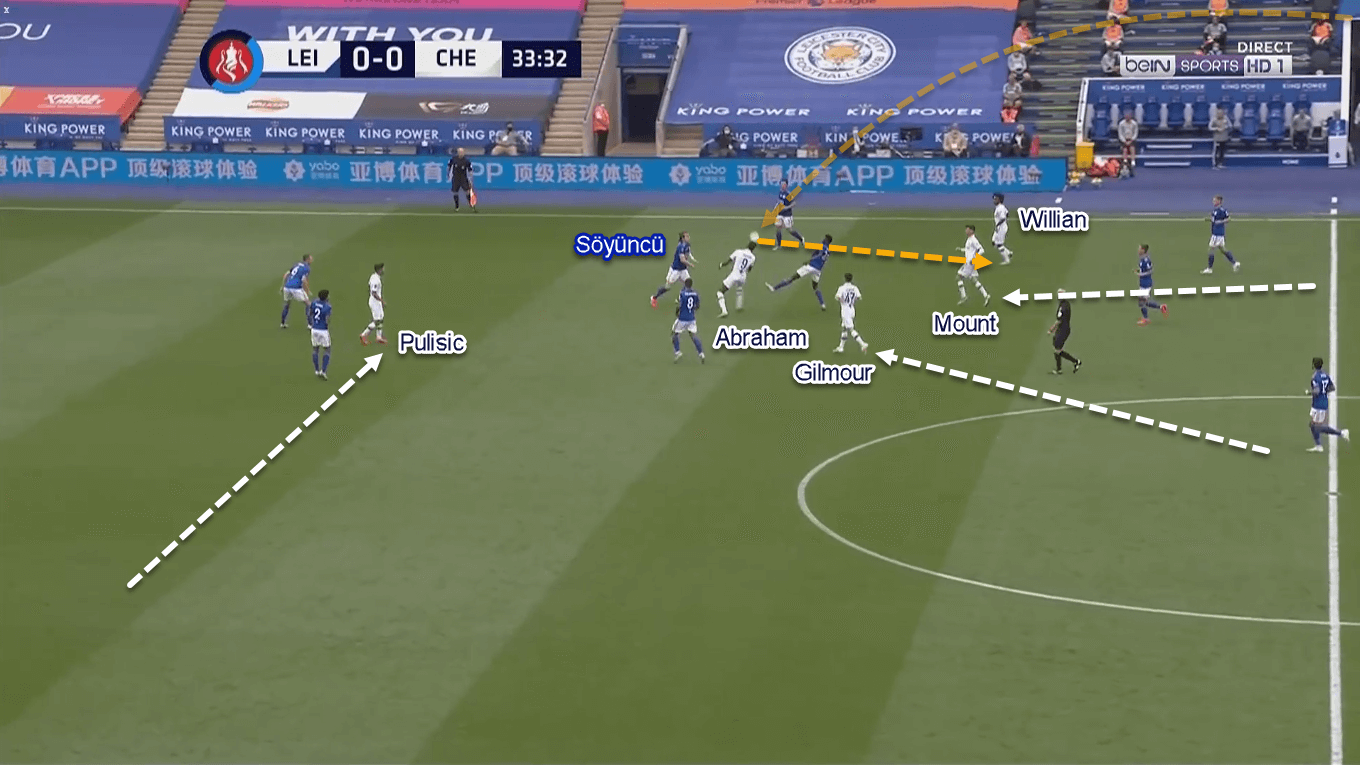

Facing an aggressive defending system, Caballero was forced to play directly at times. The target of his long balls was mainly Abraham, due to his supreme physicality. However, his teammates also had an important role in this direct approach.

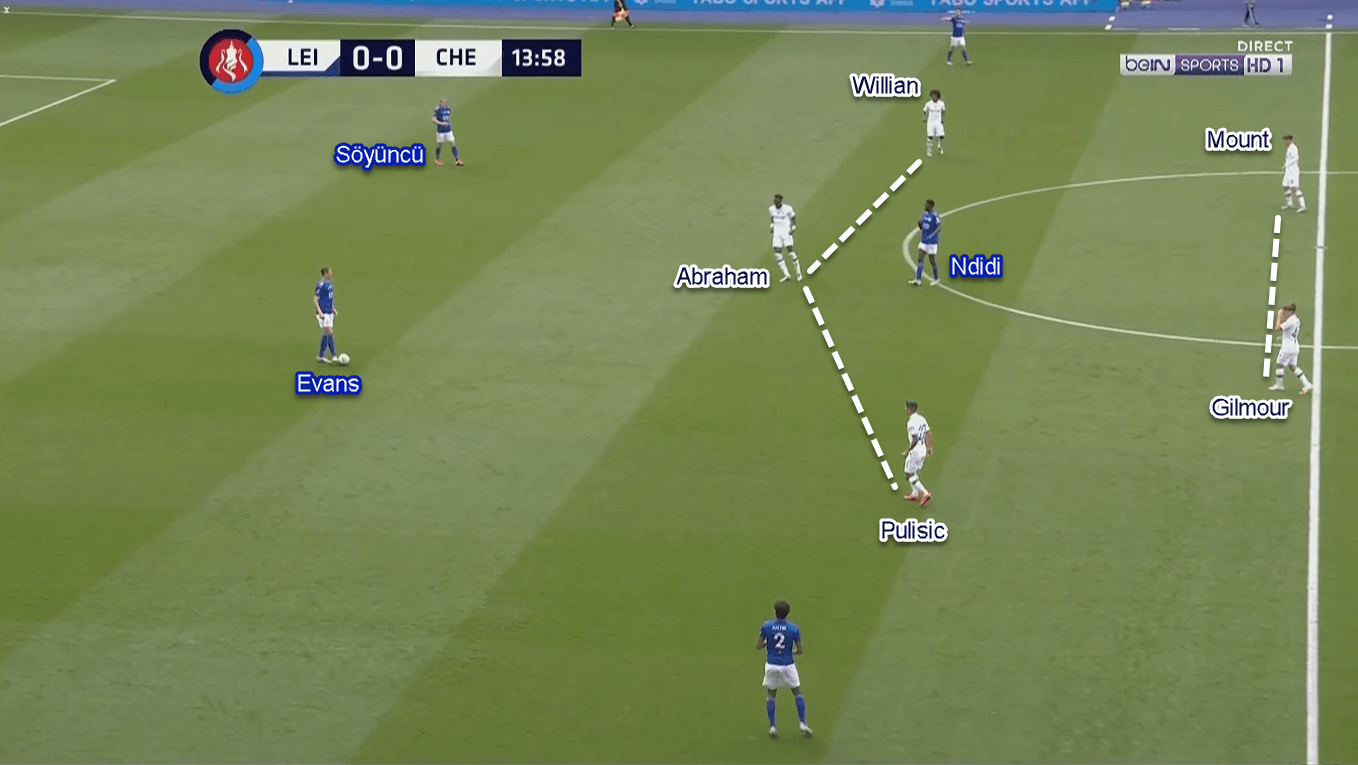

To help Abraham secure the long pass, both Willian and Pulisic would come close to the Englishman. Sometimes, the central midfielder(s) would also come nearby the centre-forward. The objective behind this was to make sure Abraham have lots of lay-off options after the aerial duel.

The same approach was also used when Chelsea were forced to play from wide areas. In this case, the on-ball full-back was given the license to spread (diagonal) long balls for the attackers in the middle. Again, Chelsea would flood the receiving area with their players to make sure they win the second balls.

If Chelsea can build smoothly from the back …

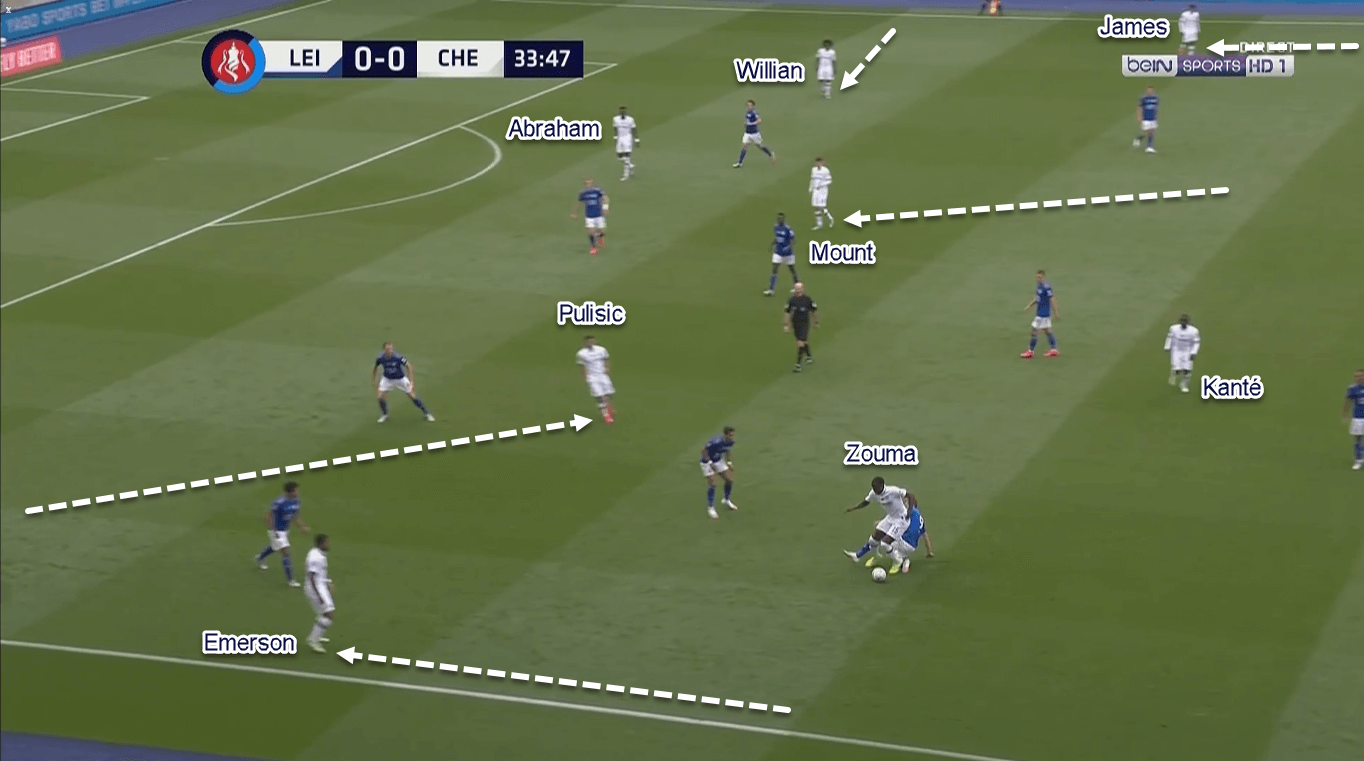

When Chelsea had the ball, they would send their full-backs wide to provide width in advanced areas. The most unique feat of their attacking game was their lopsided shape. It means that the wingers were positioned differently to each other; as well as the midfielders.

In the process, one of Chelsea’s wingers would tuck inside and play in between the lines: mainly Pulisic. Oppositely, Willian stayed wider in front of Reece James, even though he could also move inside whenever possible. One of the midfielders — primarily Mount — then would step up to accompany Pulisic in between the lines. Meanwhile, Gilmour could often be found dropping alongside Kanté when the visitors had the ball. The objective behind this shape was to allow Chelsea to have up to three players to receive vertical passes centrally.

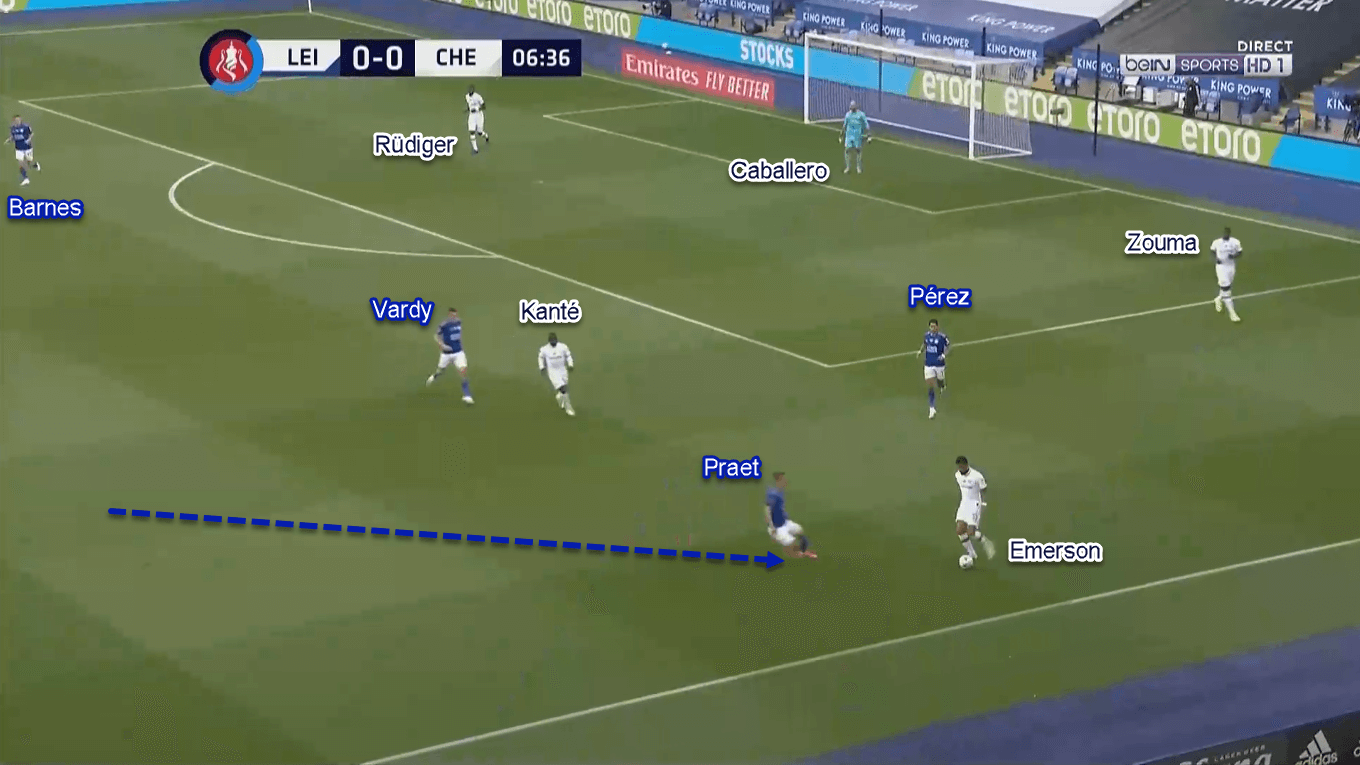

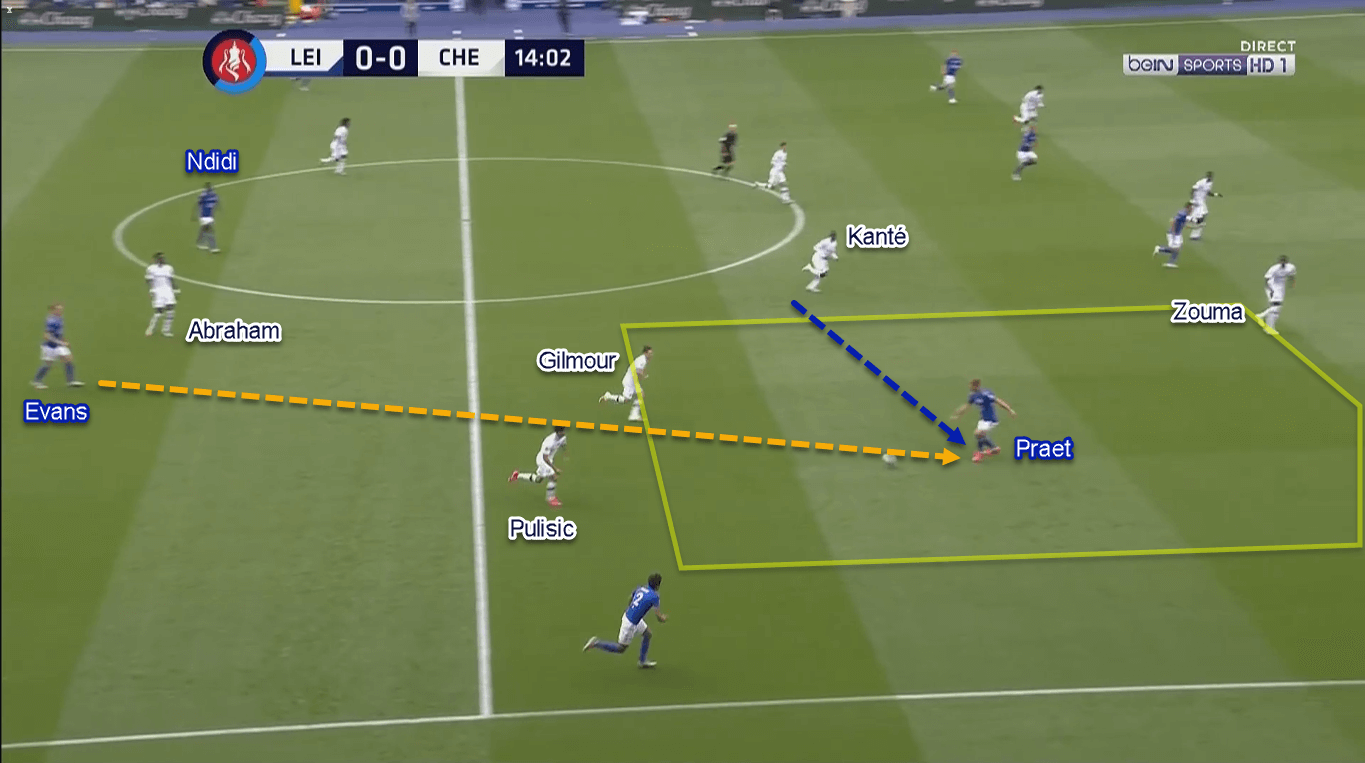

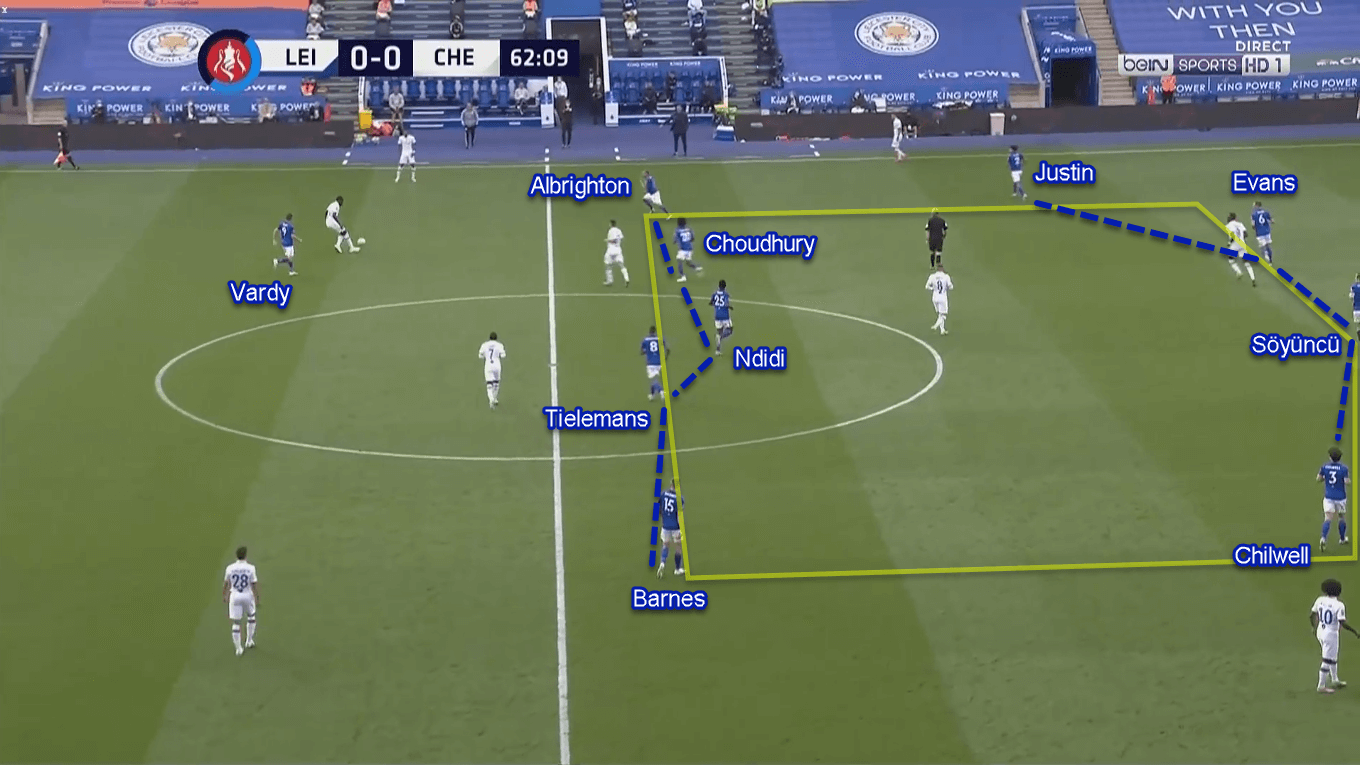

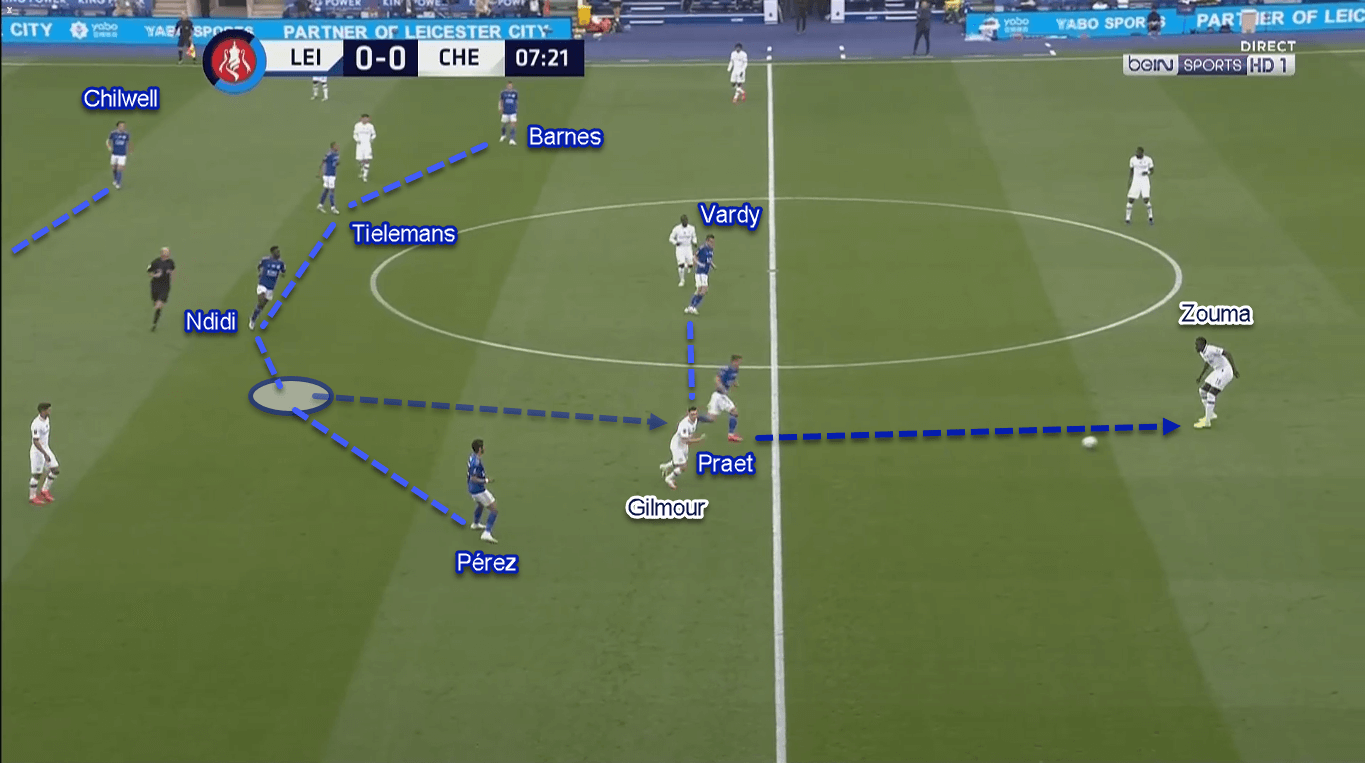

Leicester responded by moving to a mid-block 4–5–1 when Chelsea had the ball. Instead of using the usual 4–1–4–1, Rodgers deployed a flat midfield line with Wilfred Ndidi in between Dennis Praet and Youri Tielemans. Sometimes, the shape could also shift to a temporary 4–4–2. In this case, one of the midfielders would step up alongside Vardy: mainly Praet.

Why the number 26? One probable reason was that Praet played as a right-side central-midfielder. Playing in that position means the Belgian had Gilmour and Kurt Zouma in front of him. The Chelsea aforementioned duo have lesser experience and composure with the ball, which made them a pressing target for Praet. Whenever one of them got the ball, Praet would aggressively step up and press the player.

Chelsea’s defensive system

Different to the home side, Chelsea opted for a more conservative defensive approach. It means that they would drop deeper and sit in a medium-high 4–1–2–3 when they didn’t have the ball. In that shape, Abraham was tasked to close the passing lane to Ndidi. By doing so he would give Leicester’s centre-backs more time on the ball but prevent them from building the attacks centrally.

As mentioned before, Chelsea’s medium-high 4–1–2–3 focused quite heavily to close the central spaces. It showed by the outside central midfielder’s positionings that were slightly more advanced than Kanté; arguably, they were even closer to the wingers. By doing so, Chelsea would have an additional two players to prevent Leicester from building their attacks through Ndidi. Furthermore, The Blues defensive system almost left the flanks almost completely open as Mount and Gilmour were more advanced.

Even though they tried to close the central access, Chelsea didn’t execute this properly. Their lack of horizontal compactness and abandonment of the flanks were exploited by the home side quite often, especially in the first half. The next part of the analysis will examine how Rodgers’ armada did that.

Leicester exploited the defensive flaw

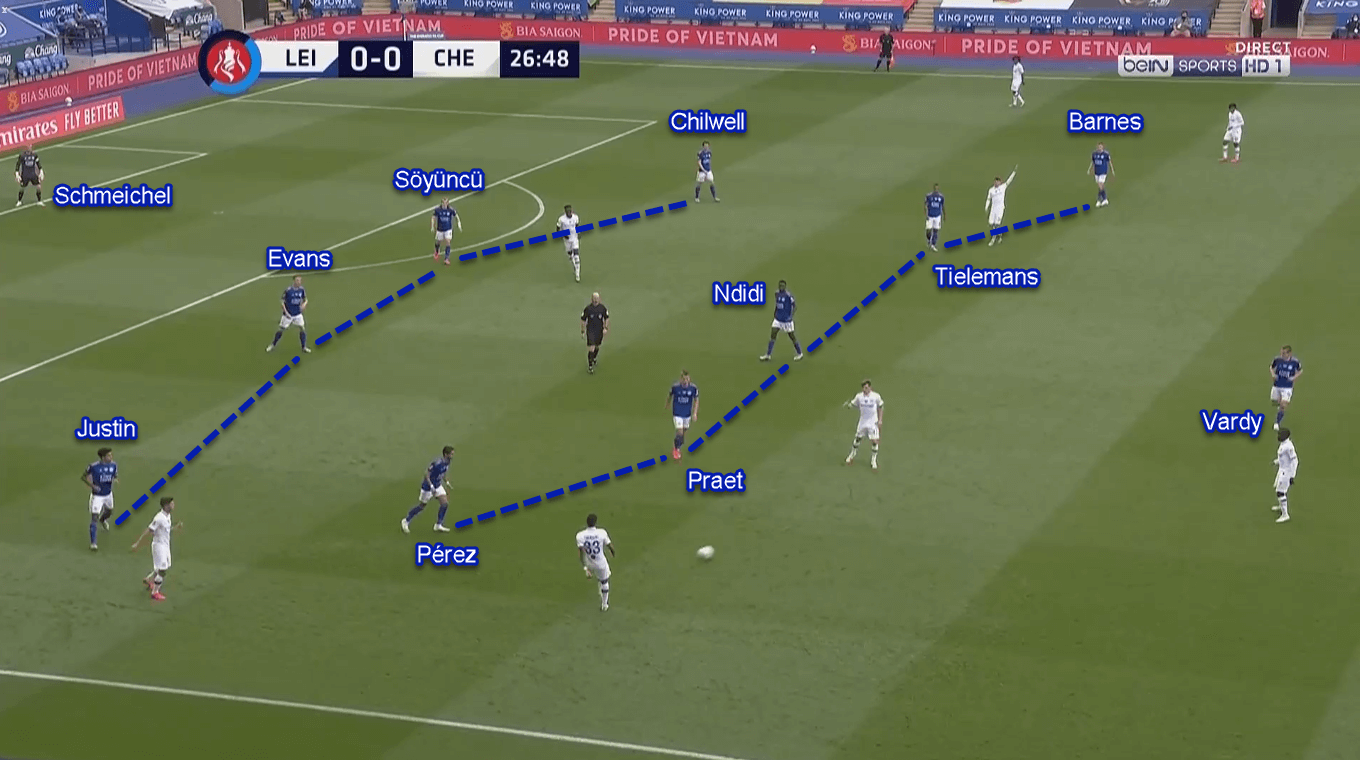

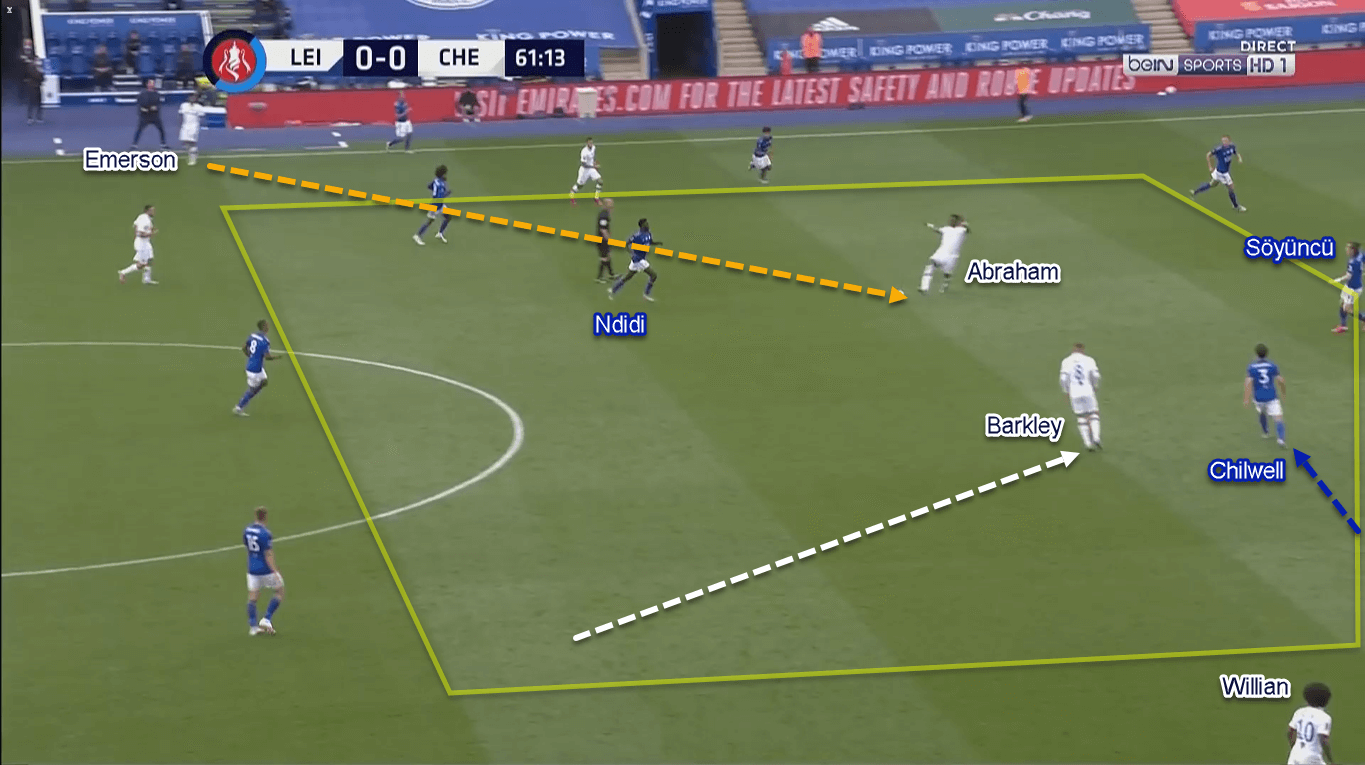

Leicester responded in two ways. First, by using their centre-backs to spray vertical passes to Tielemans and Praet. As mentioned previously, Abraham was instructed to close the passing lane to Ndidi, thus giving Evans and Söyüncü more space and time with the ball. The on-ball centre-back then could carry the ball without much hesitation before making a vertical pass.

The receiver of the vertical pass was one of the midfielders. However, they also needed to adjust their positions a little bit before receiving the ball. In the process, both Tielemans and Praet would often drift a bit wider inside the half-space to get away from Mount and Gilmour. Their drifting movements also allowed them to be far enough for Kanté to cover; thus making them receiving the ball rather comfortably.

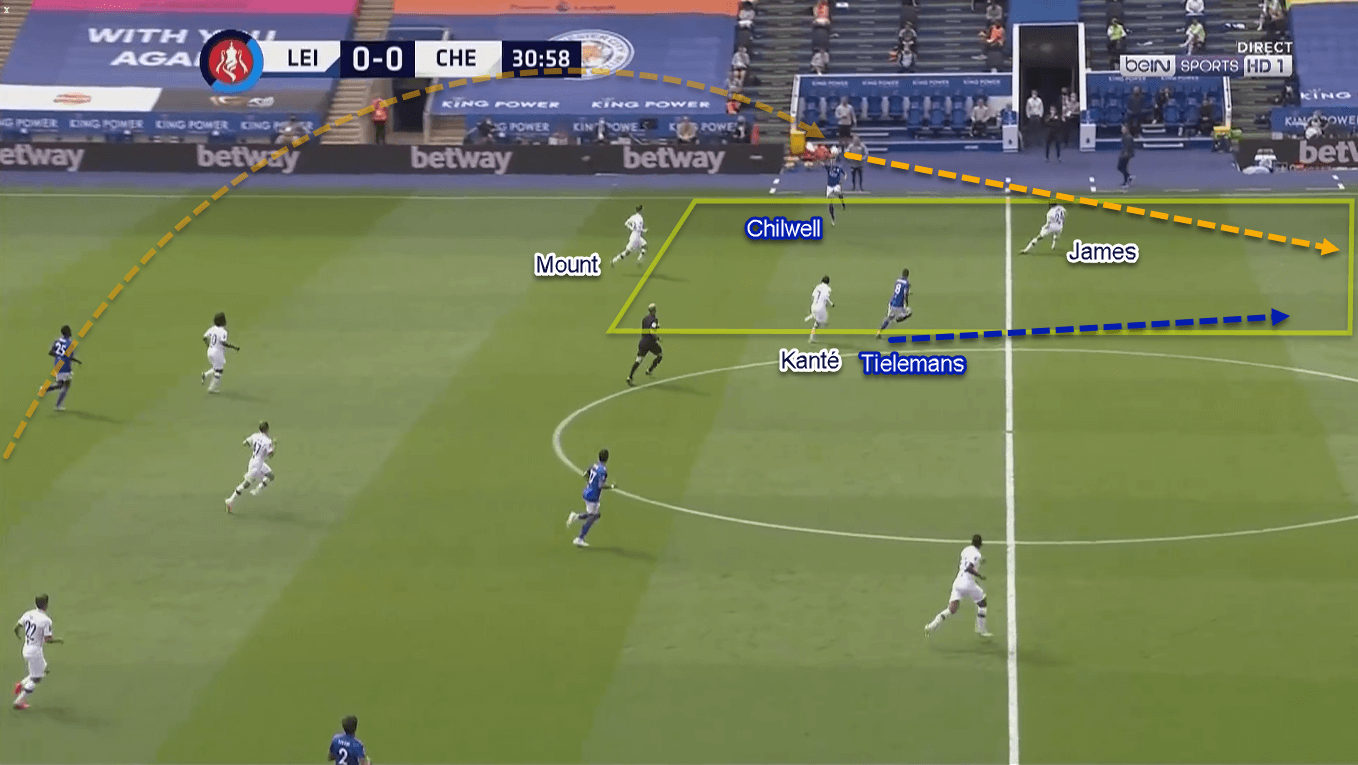

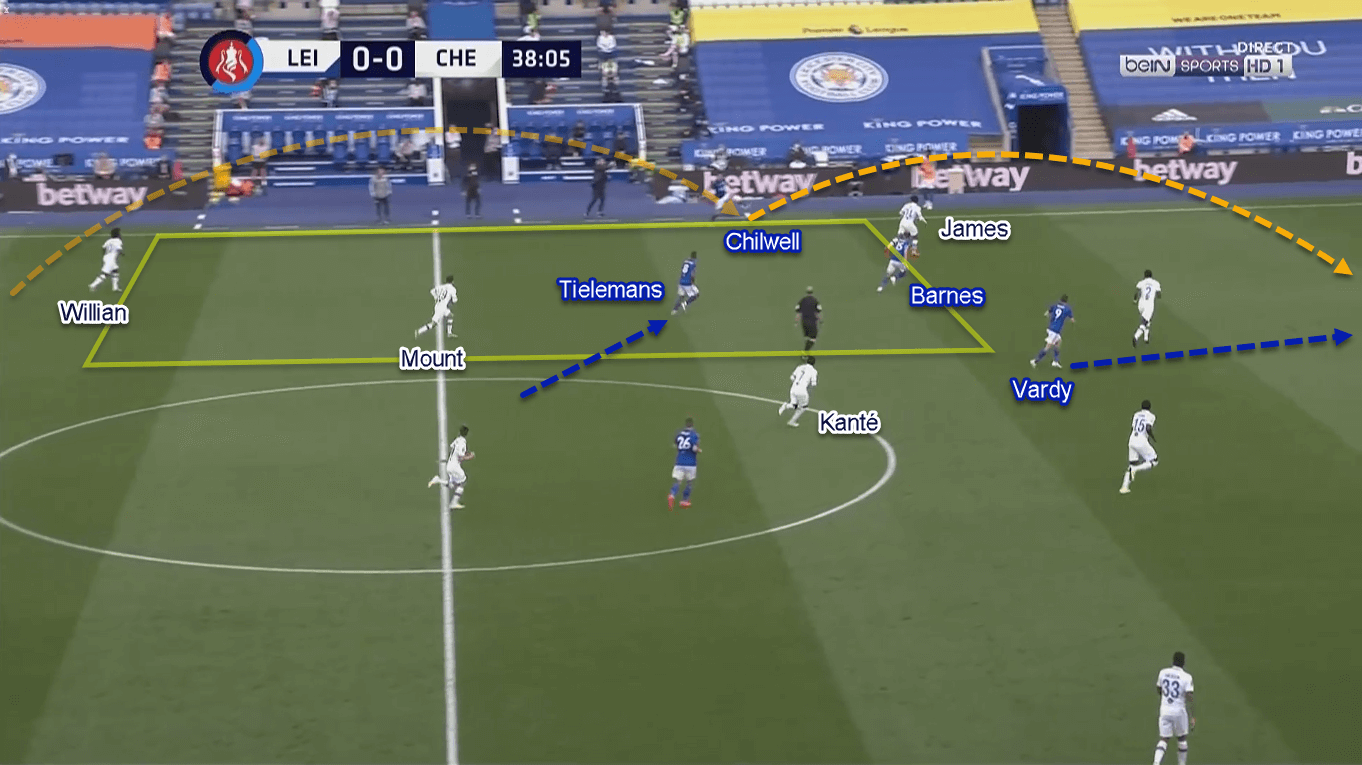

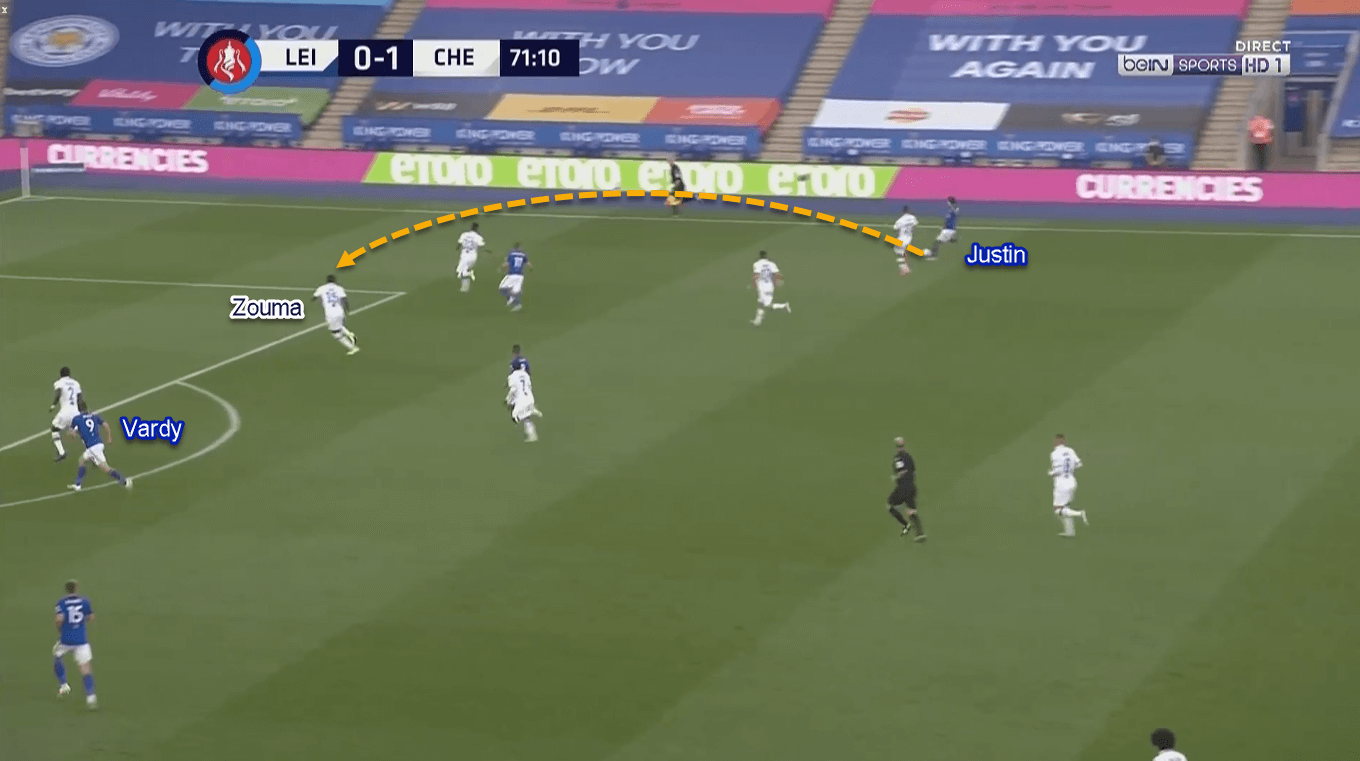

Another way Leicester used was by sending diagonal passes to the far-side full-back. As Chelsea abandoned their flanks (almost) completely, Leicester’s full-backs had more than enough time and space to receive the ball. The aftermath of both approaches was the same: flood the flank, then combine with nearby teammate(s) and/or quickly serving Vardy in behind.

The Foxes also had a big defensive issue

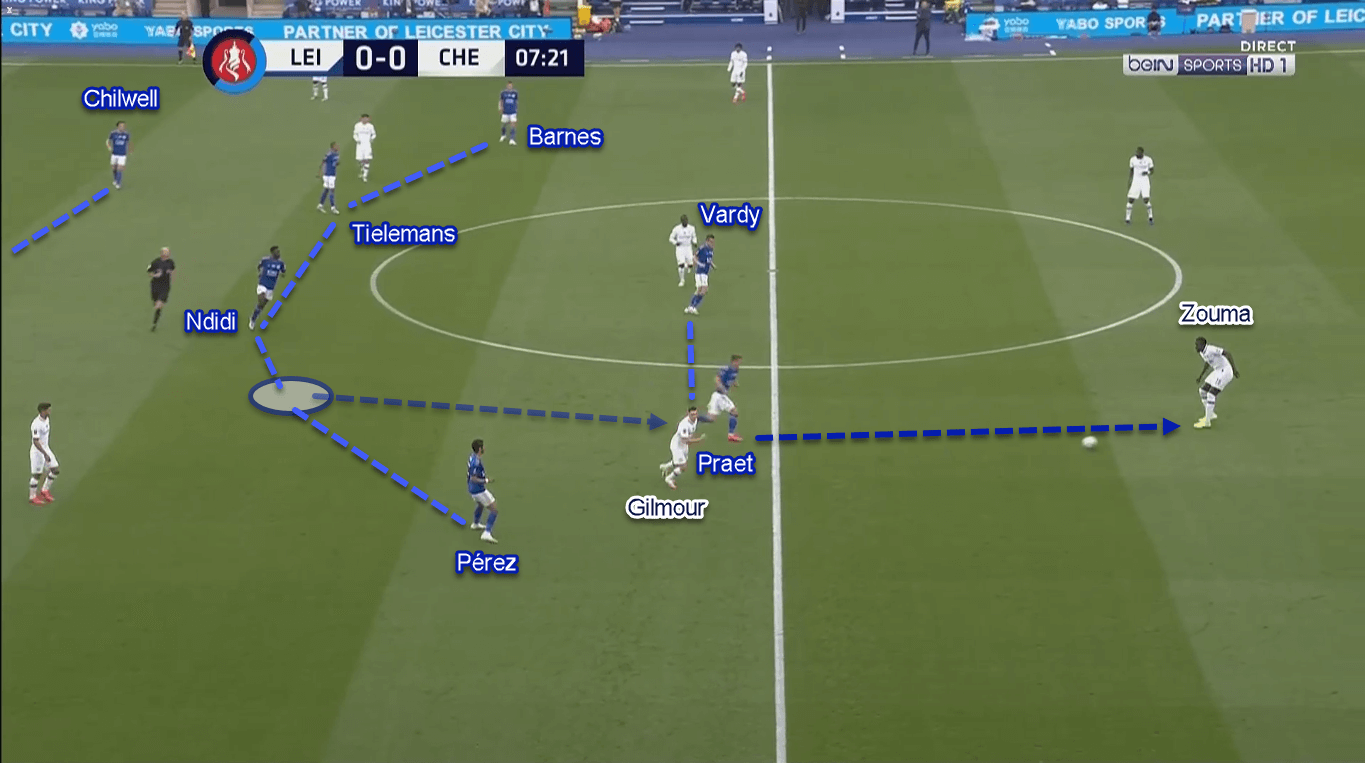

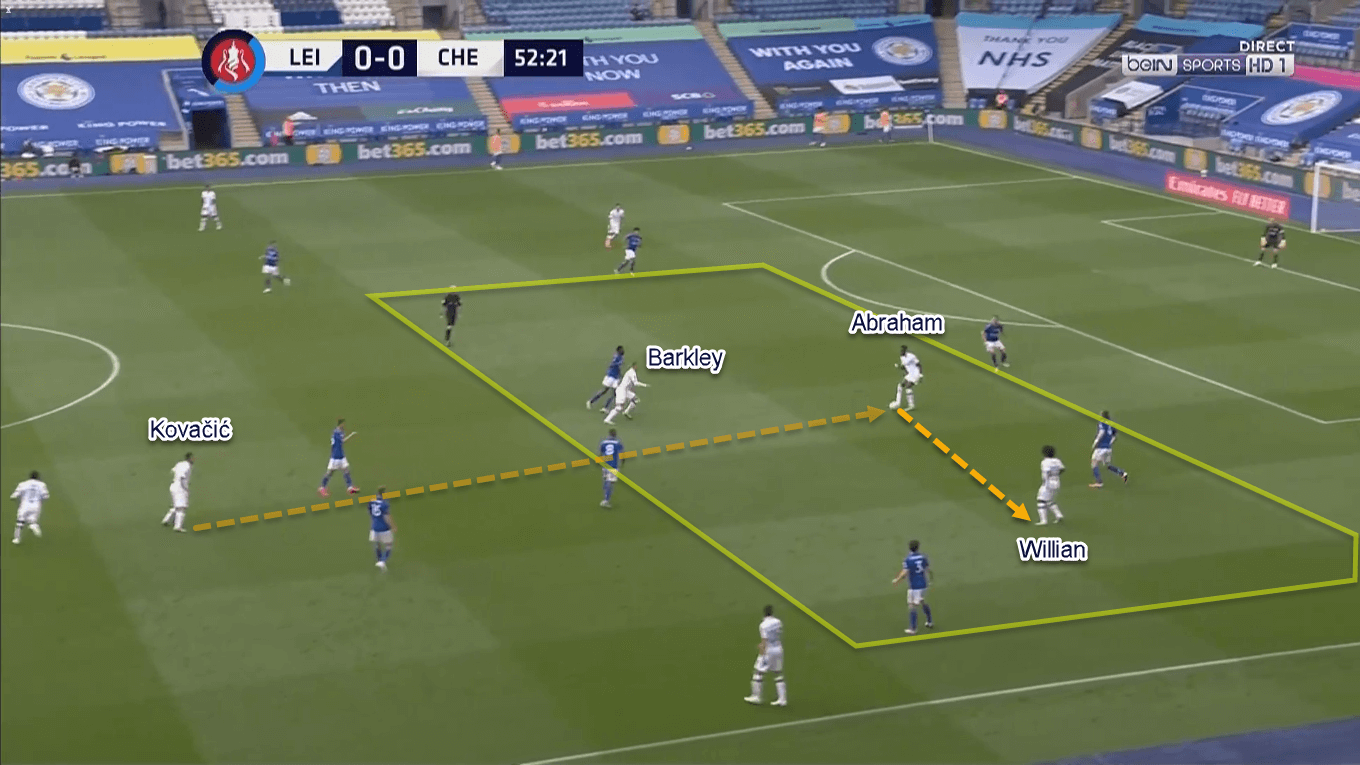

Rodgers’ decision to move away from the primary defensive shape proved to be a backfire. In the 4–5–1, Leicester used a flat midfield line with Ndidi alongside the four midfielders. Some may say that Leicester had a numerical advantage and more horizontal compactness with five midfield players defending in the same line. What happened is the opposite: The Foxes’ vertical compactness was nowhere to be found as they allowed so much gap in between the lines.

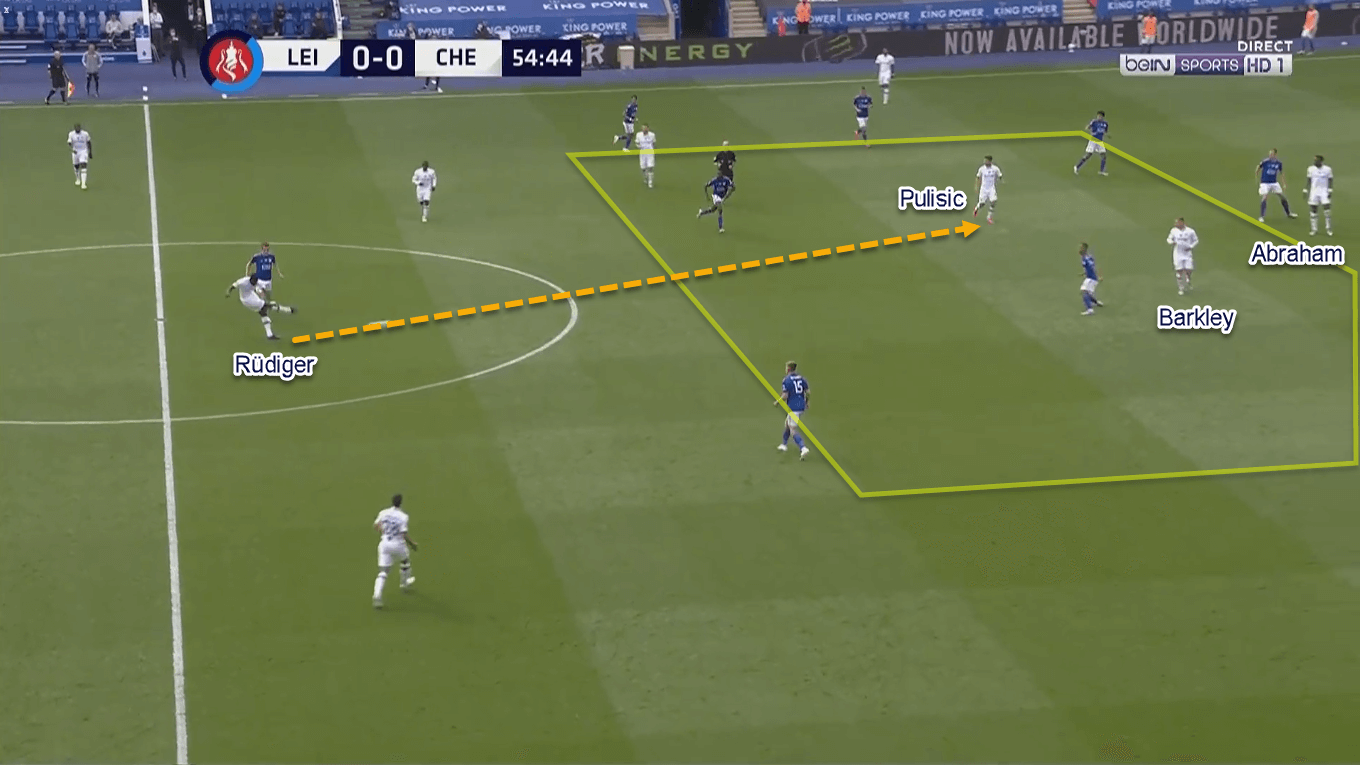

Chelsea exploited this by using at least two players as the vertical options in between the lines. They did take advantage of the issue in the first half — mainly through Pulisic — but not quite often. Lampard then took off Mount and Gilmour for Kovačić and Barkley coming into the second half.

Their introduction gave the much-needed impact. Playing more alongside Kanté, Kovačić was given the license to spray forward passes to his comrades in between the lines. The stats show Kovačić made three (60%) successful progressive passes, much better than Gilmour’s tally of one (25%) accurate progressive pass.

Leicester did try to react. To do that, Rodgers instructed the nearest full-back to come up, and close the Chelsea player in between the lines. However, with only one defender against two or three men in white, Leicester faced a numerical disadvantage to counter this offensive tactic. Furthermore, Chelsea’s distributions were quicker than the first half, underlining their tactical effectiveness.

The final push

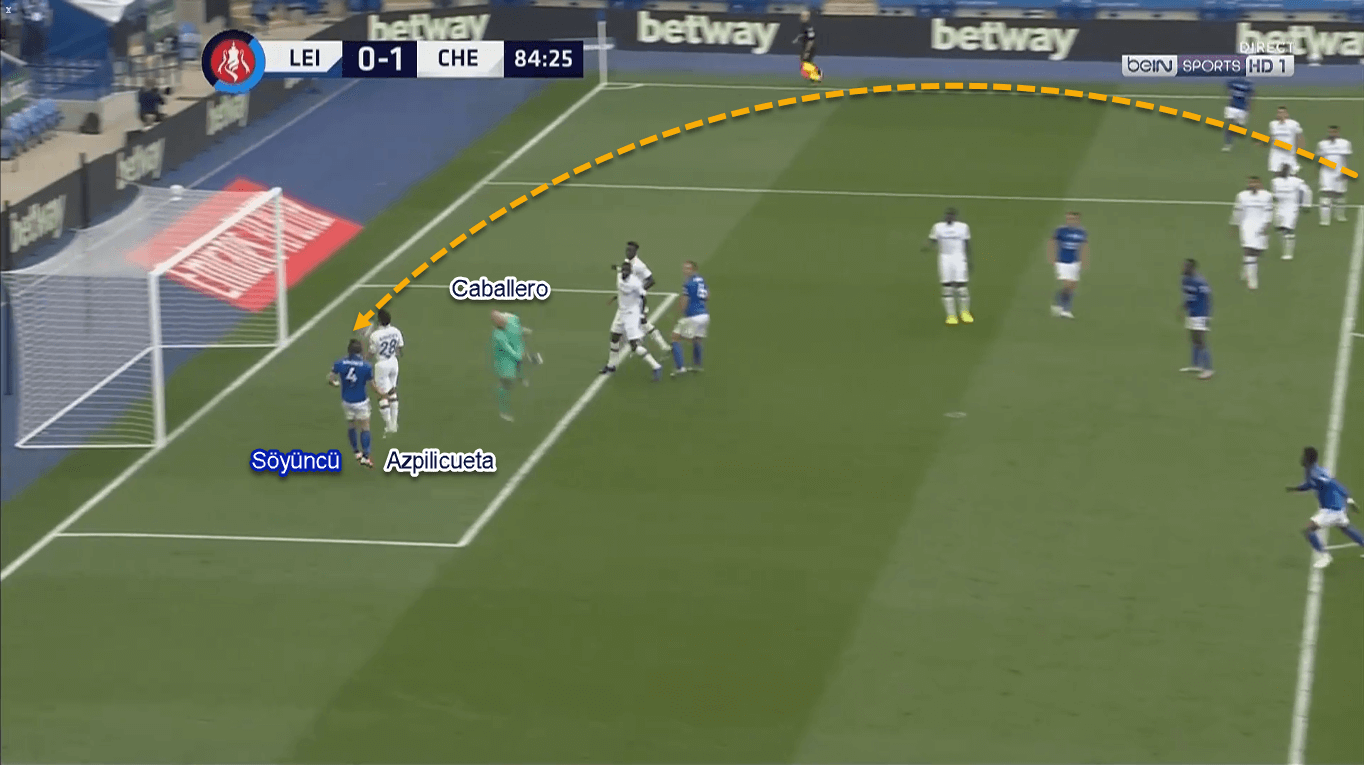

Leicester initially tried to use the diagonal-to-fullbacks approach in the second half. It didn’t work well because Chelsea were more positionally better off the ball, as well as the declining quality of Evans’ long passes. They shifted to another offensive approach later in the game: the crosses.

Instead of trying to neatly unlock Chelsea’s defensive block as before, Leicester played more directly to find the players on the flank. Before Chelsea scored in the 63rd minute, the statistics show that Leicester attempted eight crosses. However, they added seven more in the last 20 minutes. Their biggest chance — by expected goals (xG) — was even coming from a crossing sequence.

Primarily, the full-backs would be tasked to send crosses into the box. Inside the box, Vardy was supported by Tielemans, the far-side winger, and at least one another attacking player as Leicester’s crossing targets. Yet, the full-backs didn’t perform as expected. The statistics show that Justin and Chilwell only combined to make three (27.27%) successful cross throughout the game.

Rodgers’ decision to introduce Albrighton three minutes before the hour mark was to enhance Leicester’s crossing quality. It worked quite well tho, as Albrighton made three (75%) accurate crosses from just 38 minutes of playing time. However, it was never enough for The Foxes.

Conclusion

If we look at the stats, Leicester finished the game with 1.11 xG, compared to Chelsea’s only 0.78. Some may argue that the home side deserved more than this disappointing result. But, we must remember that football is played on the pitch, not on paper.

From a tactical perspective, it’s safe to say that Lampard did learn from his mistakes. He displayed brilliant in-game management by subbing in Kovačić and Barkley for the two youngsters. To be fair, his tactical adjustment was spot on, both offensively and defensively. Nevertheless, the same praise couldn’t be given to Rodgers. The Scotsman was unable to react to Lampard’s tactical adjustments, thus making Leicester out of the FA Cup.

Leicester now have to face Everton this midweek: a team with fresher legs and a much better mood. If Rodgers can’t find a solution for his team, the race for a Champions League ticket could be the next Leicester have to lose.

Comments