FC Midtjylland are on the mend after a lackluster league campaign in the previous season, which saw them finishing in 7th place and having to take part in the relegation group of the Danish Superliga. This season, they have come first following the initial 22-match league campaign and will be looking to win the league after the final 10 matches in the championship group, although they are currently sat in second.

From a set-piece perspective, Midtjylland have been exciting to watch due to their consistent efforts to come up with creative new ways of creating space in and around the six-yard box, where a single touch on the ball can result in a goal. However, while many routines have been successful in accomplishing that, they have also struggled in allowing a player to arrive in that open space unopposed, meaning that it’s been rare to see goals come directly from the first contact, resulting in the Danish side not standing out this season for their set play efforts.

In this tactical analysis, we will delve into the tactics behind Midtjylland’s corner kicks, with an in-depth analysis of how they have used screens to be dangerous from corners. This set-piece analysis will also explore the various ways in which they have achieved set-play success. More importantly, it will highlight the potential for further steps they can take to increase their set-play efficiency.

Effective Use of Screens

As mentioned at the start, Midtjylland have impressed due to their ability in creating a safe passage for the ball into high-value areas, in and around the six-yard box. One way in which this has been achieved is through their use of screens on zonal defenders. The late execution of the screen has been particularly effective, where defenders are blocked as the ball is crossed in, meaning they don’t have enough time to evade the screen and attack the ball and are, therefore, unable to contribute defensively to the corner kick.

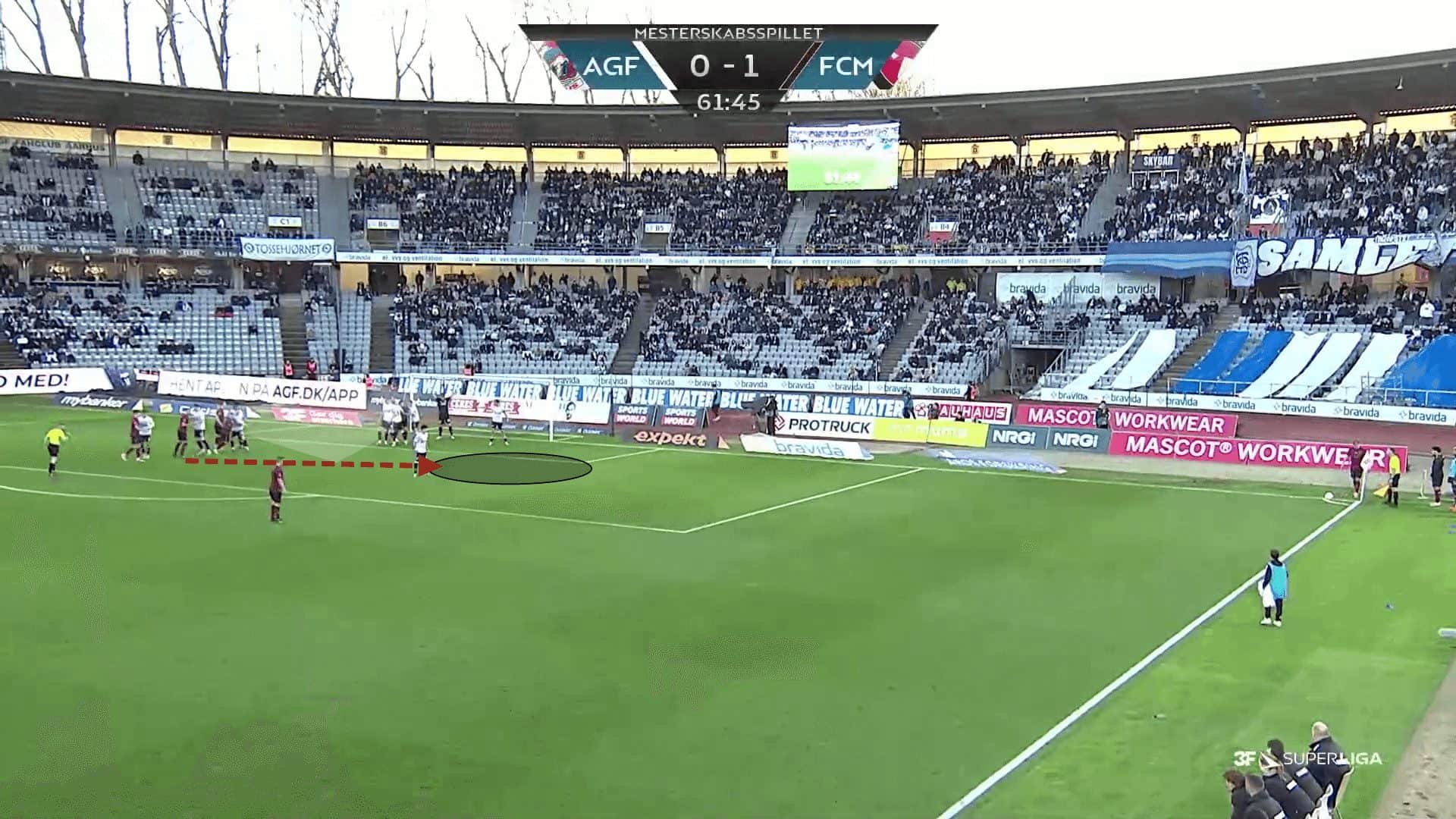

The image below shows the space that Midtjylland is attempting to exploit. In contrast, the white arrow shows how the screen setter is outside of his target’s point of view. This means that the defender won’t be able to see the screen coming, and the surprise element prevents him from evading it.

As the ball is crossed in, the screen is executed. By the time it would take for the defender to distance himself from the screen and attempt to attack the ball, the shot would have already been made by the attacker arriving in the space. This means that the ball is able to safely arrive in the space highlighted. All that is left in order for this routine to result in a goal is for an attacker to arrive and direct the ball goalwards. However, it is in this aspect where Midtjylland’s success has been limited.

Although Midtjylland’s success from the first contact from corners has been limited, their positive intentions and heavy occupancy inside the box, combined with creating open spaces in and around the six-yard box, has led to numerous second phase opportunities and goals from loose balls being collected. The ball is able to consistently arrive in high-value areas, where even if the attacker cannot get a clean first contact on the ball, neither can the defender, meaning that the ball drops around the six-yard box. Attacking in numbers allows Midtjylland to have a higher chance of picking up the loose ball, which has allowed them to score many goals following pinball-like situations in the penalty area, which is no coincidence.

Another method used to create space inside the six-yard box is the use of decoy runs. An inswinging delivery combined with large numbers of attackers around the goalmouth automatically forces the opposition to withdraw into their own goal, giving up space all around the six-yard box. The use of a decoy run, pretending to want to receive the ball from a short pass lures the nearest zonal defender away from goal, which creates a bigger space by the near post for the ball to arrive in.

Inside the pack, the attackers can attack the space created, and the natural positioning of the defenders means that the attackers can execute their move from the defender’s blindside, allowing them to arrive in the target area with more time and space.

Similarly to the screen at the near post, Midtjylland also have used screens at the far side of the six-yard box to create space in the six-yard box. It is important for attacking sides to consistently switch up their corner routines, as defender begin to anticipate the direction of the cross and where their markers are making their runs. The same idea is used as for the first examples. Still, the different placement of the attacking unit means that the defending side doesn’t have the image they had in mind, and are therefore assuming a different corner routine will be utilised.

Even with the likes of Arsenal in the Premier League, as they have consistently used one or two variations of the same method, teams have been able to predict the runs and behaviours of certain players. This has led to their set-piece goals drying up from the first contact that was so effective in the winter months.

Deep Runs to Aid Separation

The first part of this analysis clearly describes how Midtjylland are able to create open spaces inside the six-yard box, through the late setting of screens. In order to achieve a successful corner routine, this first aspect is important, but the second element is essential and is so influential that corner success can be achieved without the first element. The second element is to create separation for an attacker, meaning they can attack the ball without opposition disruption, which allows a player to generate maximum power in both the aerial duel and headed effort.

One way in which Midtjylland have increased the chances of the second element being achieved is through the change to the starting positions of the attacking unit. The distance from the starting position to the target area is greater, which gives attackers more opportunities to lose their marker by having more attempts to dismark through changes in speed and/or direction. Even after an unsuccessful attempt, there is still enough distance to the target area that the attacker can attempt to dismark one or two more times.

Furthermore, the angle of the attacker in relation to his marker is designed so that the defender cannot see the ball and attacker simultaneously. As a result, defenders must either choose to focus on attacking the ball to clear it, where their assigned attacker has the potential to move somewhere else inside the penalty area unmarked for an opportunity to attack the ball in the second phase unopposed. On the other hand, the defender may choose to solely focus on the attacker and prevent them from reaching the target area, but if an attacker manages to gain some space and make a burst towards the ball, the defender is at risk of giving away a potential penalty by having no intention of playing the ball.

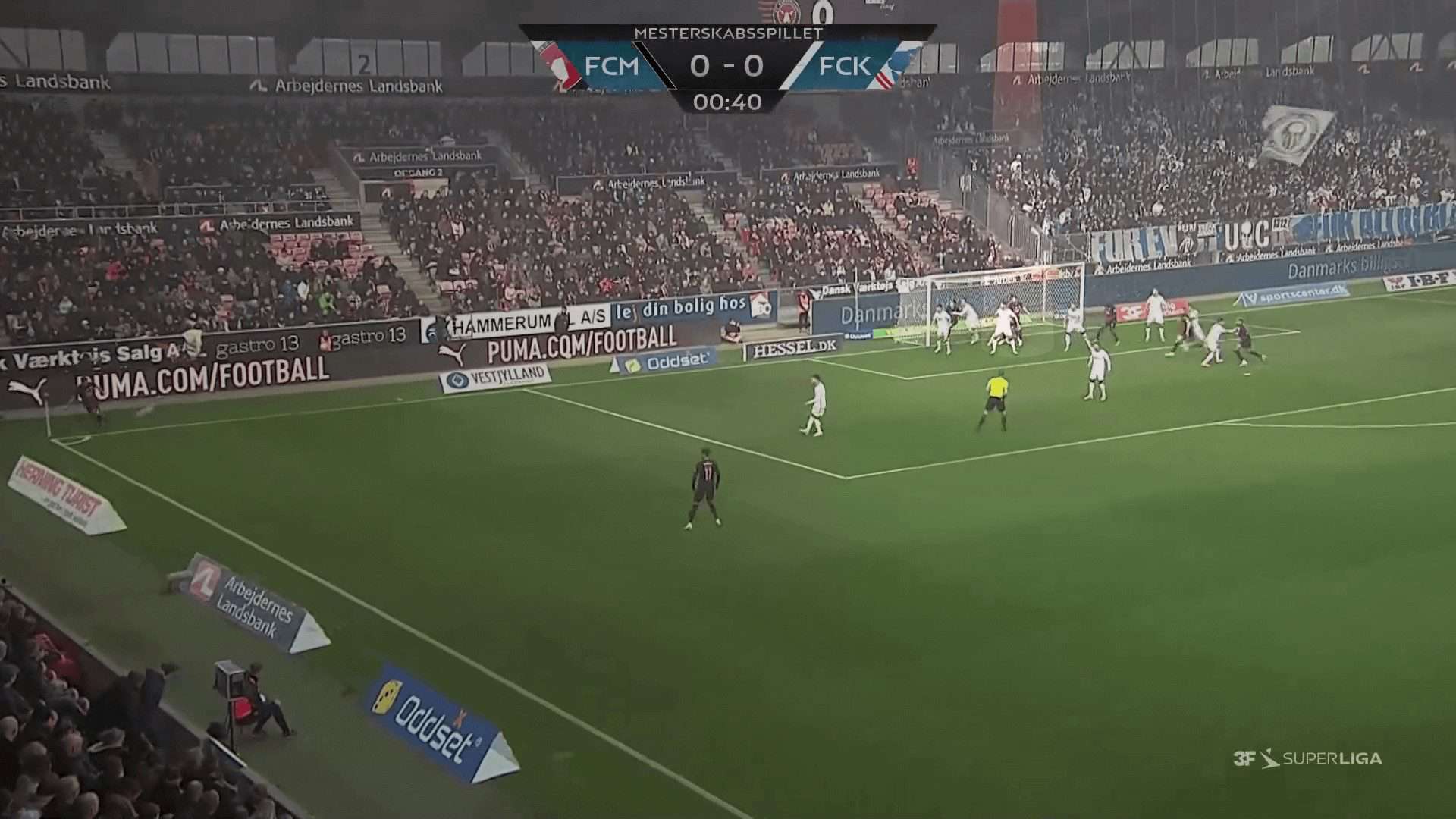

The principle of arriving in space from the defender’s blindside is also continued in other set-play aspects. Midtjylland similarly continues to crowd the penalty area with big numbers during long throws, giving them a strong chance of sustaining pressure and winning second balls.

Like with the corner kicks, the attackers attempt to arrive in space from their marker’s blindside, where they can create separation exclusively through their starting position. It appears like the attacker is focused on preventing the goalkeeper from claiming the ball, but this is designed so that the defenders don’t think of him as a threat to the ball. This allows him to remain unmarked and attack the ball without any disruption.

Another way in which Midtjylland attempt to give their attackers the separation to attack the ball unopposed is in a similar vein, through the different starting position of the target attacker. When a player starts outside the box, they usually remain unmarked as they are not a threat to the first contact of a corner kick; rather, they are there to collect the ball in the second phase. However, teams like Aston Villa have been excellently using the runs from outside the box to find players who already have the separation that is so desperately sought after.

Although potentially effective, the above example was harder to execute due to the zonal defenders standing in close proximity to the target area. To make this more effective, short corners should be utilised. I will be looking to release a piece exclusively on this method in the coming weeks, but for now, the example below shows why short corners coupled with runs from the edge of the box can be extremely effective.

As the short pass is made, zonal defenders slowly look to step up, away from their positions, to reduce the space opponents have in front of them. However, in this transitional phase, attackers can exploit the space they vacate behind whilst the cross isn’t properly closed down.

In addition, defenders start to focus on the position of the ball and must keep their eyes on the ball as it moves into open play. While attackers already have instant separation, the short corner gives attackers the ability to make their runs at full speed, with defenders not having the opportunity to scan the surroundings. The player outside the box isn’t considered threatening before the corner is taken, so after the short corner is played, the attacker from deep is more likely to be forgotten about and allowed to ghost into the back post area.

Causes for Concern

While corner kicks have been optimistic for Midtjylland, there have been a couple of issues which have prevented the Danish side from being an efficient set-piece side.

Setting screens on goalkeepers is extremely important for several reasons. Firstly, there is more space inside the six-yard box for the ball to arrive in rather than the goalkeeper claiming it. In addition, blocking the goalkeeper and preventing him from claiming it helps Midtjylland to be more likely to sustain pressure, with the defending side having no instant method of killing the attack. When Midtjylland have blocked the goalkeeper, many chances have been created, but their inability to do so consistently meant that many corner kick attempts were instantly extinguished by the goalkeeper claiming it.

Firstly, the early attempts to set screens on the goalkeeper have been too predictable, which has consistently made them ineffective. At the start of the analysis, we mentioned how the late setting of the screen on zonal defenders was particularly effective in reducing the chance of a defender evading the screen.

However, when it comes to blocking the goalkeeper, the screen is attempted before the kick is taken. This gives defenders plenty of time to react to the attacker’s intentions and aid the goalkeeper in evading the potential block.

When a defender expects the goalkeeper to be blocked, they can use their strength to shift an attacker out of the goalkeeper’s path as the cross is taken. This allows the goalkeeper to have a clear, direct path to the ball, meaning that they can claim any ball heading towards the six-yard box.

This problem is similar to the problem Sparta Praha faced in my previous analysis, where Arsenal’s Ben White showed the template for fixing the issues for Sparta. Setting the screen in the last moment as the corner is about to be taken prevents defenders from being able to help the goalkeeper evade the screen. If the screen on the goalkeeper can be made late, and if the screen setter can arrive from the goalkeeper’s blindside, he can use the element of surprise to ensure the goalkeeper remains rooted to the goal line and allow his side to consistently deliver the ball into high-value areas without the worry of the goalkeeper claiming it.

One of the other issues mentioned earlier in the analysis is the inability to consistently create separation for the attackers. The image below shows how, on one of the occasions where the goalkeeper is forced to remain on the goal line, and the ball is able to enter the six-yard box, no attacker is capable of taking advantage. The attacker is followed by his man marker, meaning he cannot attack the area with momentum, and when he does arrive, a zonal defender is able to win the aerial duel with relative ease in the 1v2.

Outside of Midtjylland altering the starting positions of attackers, not much effort has been put into creating space for attackers to be able to use to attack the six-yard box. This can be resolved through attacking in clusters, using screens, a train lineup, using deeper positions or other staggered running angles and speeds, but the relatively straight line runs to the six-yard box have meant that it is rare for attackers to arrive at the six-yard box with momentum.

Conclusion

This tactical analysis has described why Midtjylland are an exciting yet unbalanced set play side. The use of screens has created numerous high-value opportunities through the ball arriving in the six-yard box and not being cleared, but their inability and inconsistencies in creating separation for members of the attacking unit has meant that it has been rare for attackers to take advantage of the space that has been created, which has led to Midtjylland relying on winning second balls and creating chances in the second phase to score goals from set plays. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but a strong set play side should show signs of being able to create chances directly from corners, especially when facing sides whose setups are sub-optimal. Relying on winning second balls means that opposition sides can adapt their setups to increase the numbers inside the six-yard box to increase their chances of winning the loose balls.

Comments