There is no doubt that the Eredivisie is a two-faced league in which the traditional ‘Big Three’ has an enormous advantage in silverware, power, and financial possibilities, compared to the rest of the league. The hegemony of Ajax Amsterdam, PSV Eindhoven, and Feyenoord Rotterdam is represented by 73 Dutch championship titles (from the 130 available), 57 of which since 1956, from when the domestic league is called Eredivisie – this latter means an overwhelming 92% winning rate from the Big Three. This is why AZ Alkmaar’s great performance from the previous season was a breath of fresh air and possibly a sign that the task of outperforming the giants is incredibly difficult but by no means impossible.

Many of the smaller (or less privileged) Dutch clubs follow the same philosophy as AZ Alkmaar but FC Utrecht seems to be in the most advanced position. Since the 2015/16 season, they are a constant top-6 side and this year, they even reached the Dutch cup final which was sadly voided because of the known reasons. No question that Utrecht’s progress is the outcome of a well-thought and consistent strategy which is still far from concluded. In this tactical analysis, we will investigate the club’s performance both from a statistical and tactical point of view, while paying extra attention to the quality of the squad and the status of the youth development in general.

1) Statistical performance

First, let’s put the Utrecht players’ performance into context by comparing their figures to the Eredivisie average. For this, we will take a look at the figures of those with at least 600 minutes played in the 2019/20 Eredivisie season, and we compare all squad members to their opponents in the same positions.

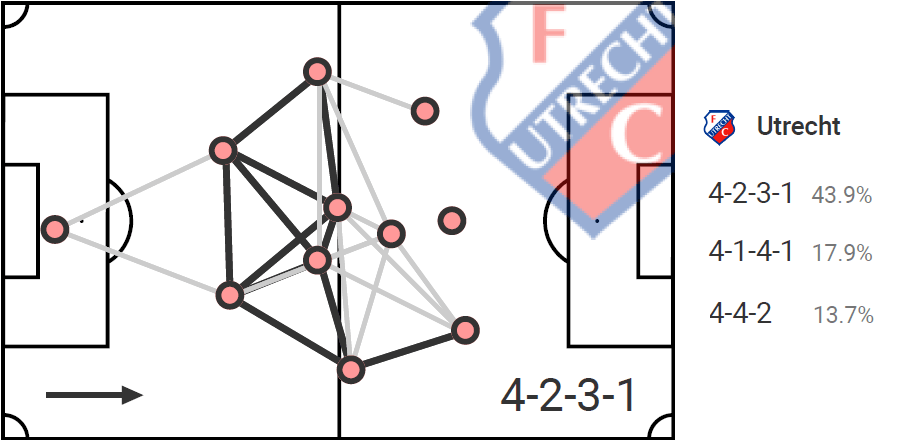

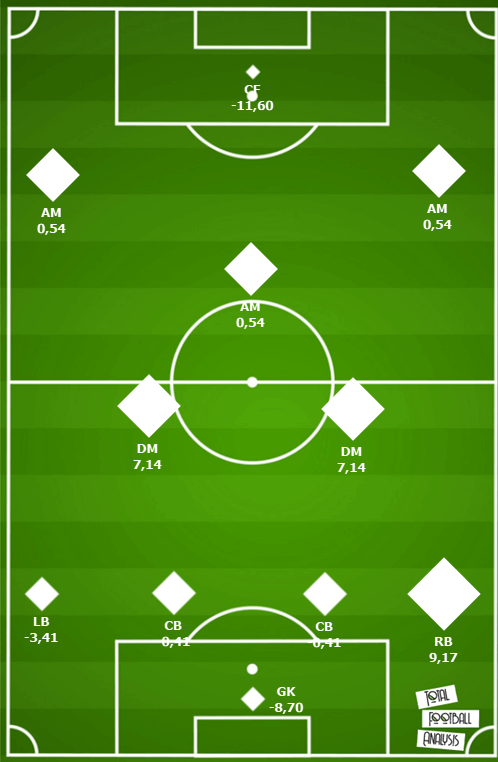

As Utrecht used a 4-2-3-1 formation in 43.9% of the domestic league games (frequently forming into a 4-1-4-1 or a 4-4-2, or even a 4-3-3 in the last few matches), we calculated with three attacking and two more defensive-minded midfielders when doing the comparison. In all cases, we used the ten most significant statistics that determine the overall performance of the given position the most. Obviously, as we have already mentioned in the very beginning of this analysis, the Eredivisie is a ‘top-heavy’ league in which the averages are therefore heavily distorted by the best performing teams – nevertheless, this is a good indicator of Utrecht’s general strengths and weaknesses throughout a whole season.

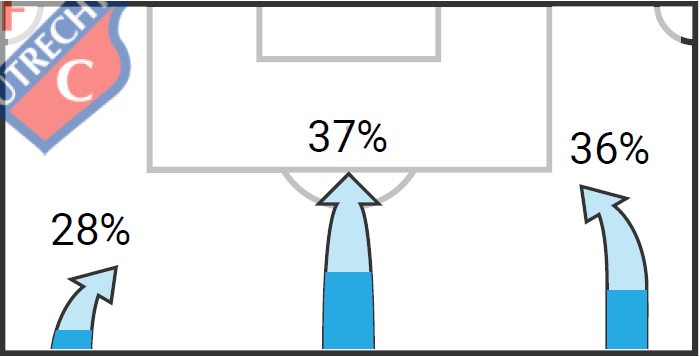

From the size of the diamonds, we can easily detect in which areas of the pitch were the Utrecht players more effective and which were the rather weaker links of the collective. The team seems the strongest in the right-back position where they performed 9.17% above the average, while the defending midfielders were also comfortably above the line with 7.14%. The centre-backs and the attacking midfielders faired just well, very close to the overall league performance, with 0.41% and 0.54% above the line respectively. The main issues were in the remaining areas: an 8.70% worse result between the sticks and 11.60% worse in front of the goal would mean a significant problem for any team, not to mention a smaller club with great ambitions but moderate possibilities. The -3.41% performance of the left-back does not help either – no wonder that throughout the season there were 8% more attacking actions run on the right side and 9% more in the middle of the pitch.

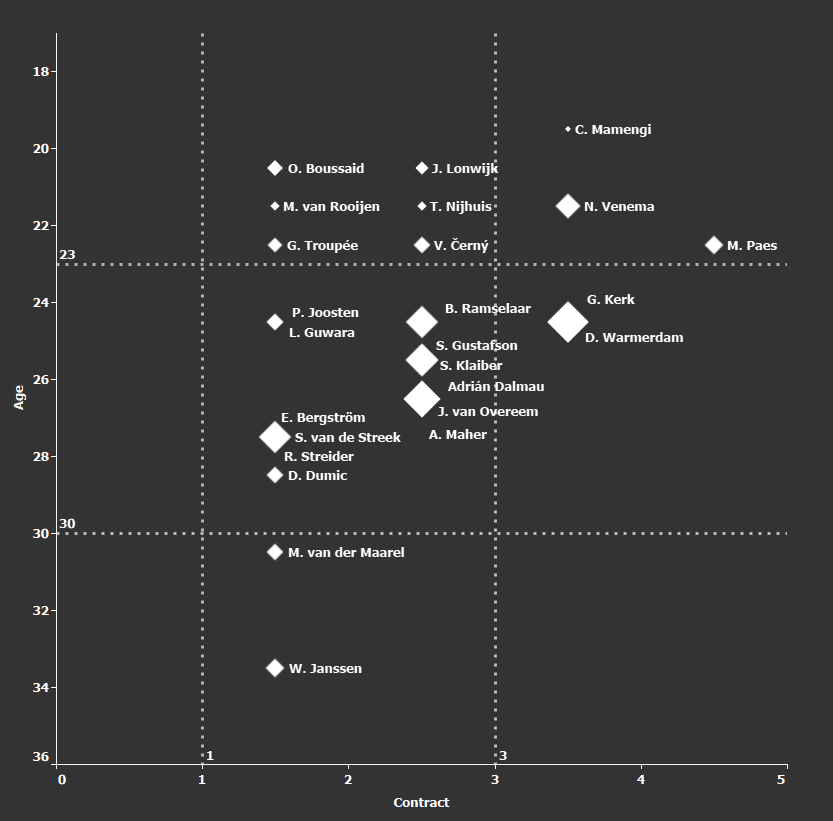

Taking a look at the club’s current, provisional 2020/21 squad, it turns out that many of the players are on the verge of an expiring contract which will either be prolonged or the player will need to be sold still this summer, driven by the financial aspects of the game. The most promising and comforting section for Utrecht is the upper-right corner of the matrix, in which we can find the squad members under 23 and with more than 3 years remaining from their contracts. The players with the highest market values, indicated by the size of the diamonds, understandably fall into the middle cluster, being in their peak years and having long-enough contracts, suggesting that the club can either build upon (and around) them in the next few seasons or realize a profitable transfer on them.

2) Tactical performance

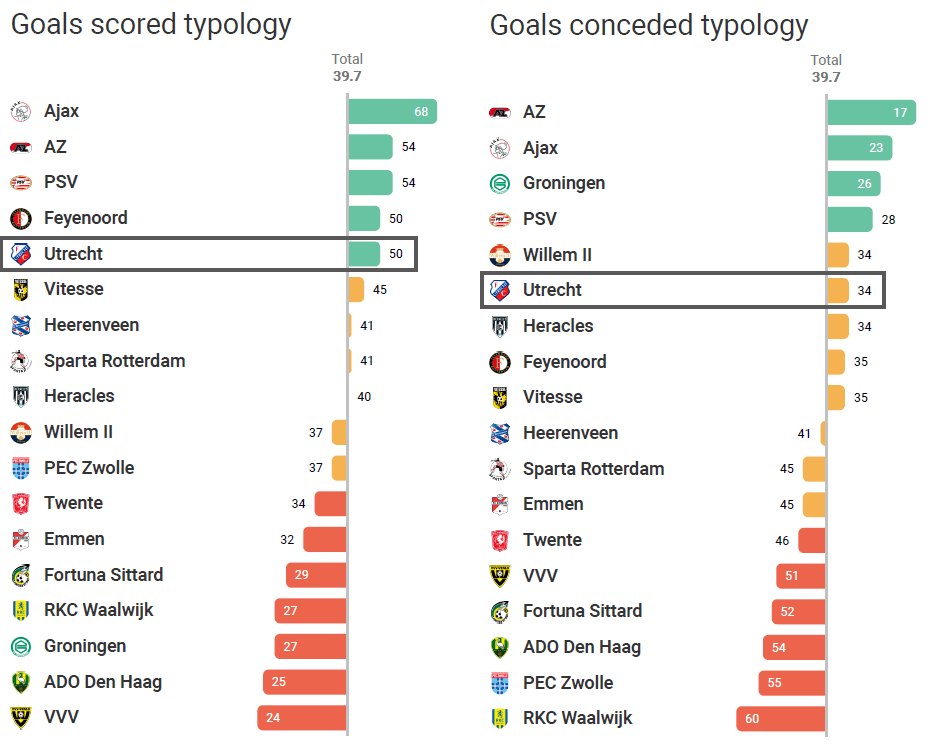

As we will see in the next graph, Utrecht managed to score the same amount of goals as third-placed Feyenoord (50) and, even more fascinatingly, conceded one fewer (34) than the Rotterdam giant, with both playing 25 games in the season. Although these figures alone would have not been enough to finish in the top four, the eventually earned sixth place does not show the reality either: Utrecht’s goal difference was +13 compared to fifth Willem II who were ahead with only 3 points and with one game more played when the league was terminated. Moreover, they collected 4 points from the 6 available against each other, meaning that should Willem II not have had the one-game advantage, Utrecht would have finished in the fifth place of the Eredivisie.

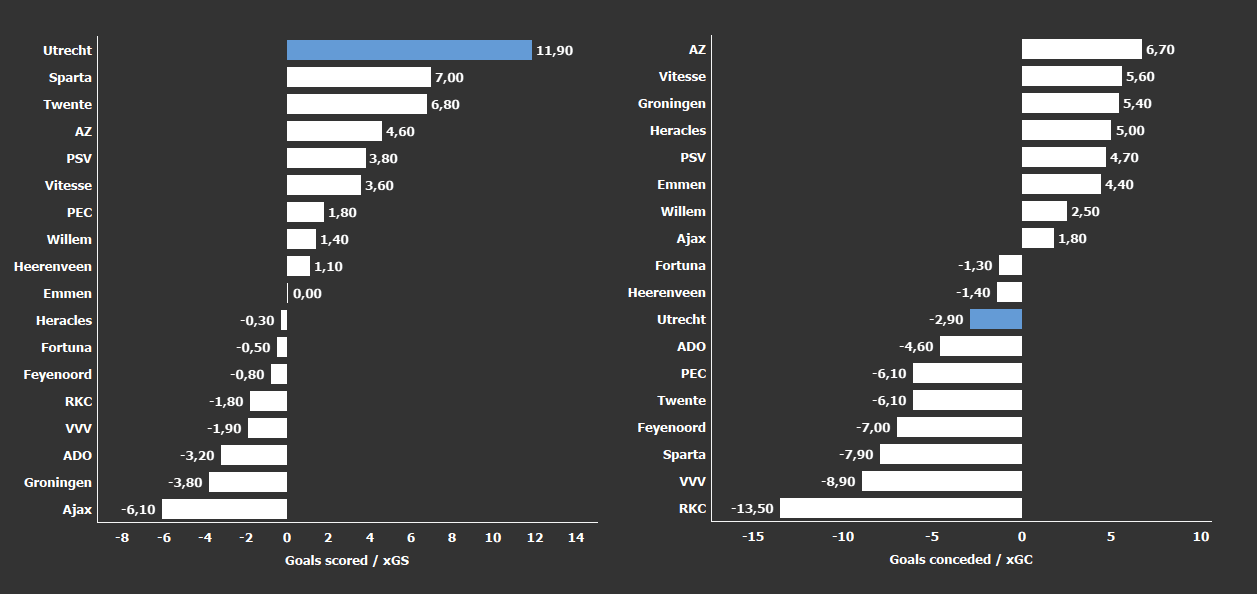

But the next illustration sheds light on a different aspect of Utrecht’s performance. The graph shows how each team’s goals scored and conceded relate to the expected figures which describe the quality of all attacking and defensive actions, regardless of the actual outcome of those. In this respect, it turns out that Utrecht scored 11.90 goals more than what their actions would have suggested, indicating that the team’s finishing performance was outstanding in the season behind us – and, of course, that they had a bit of luck too.

Now that we saw the main statistics of the team, let’s concentrate on the tactical performance.

Defending

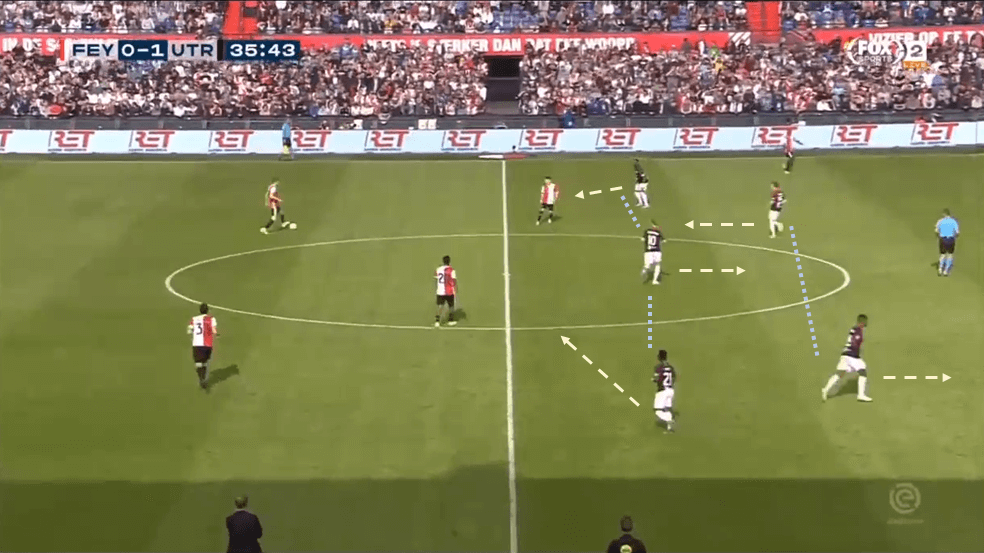

One of the core elements of Utrecht’s strategy is letting the opponent approach the half-line and start an intensive pressing in the middle third. The team’s 12.78 PPDA (passes allowed per defensive action) figure is only the 16th best in the league, only Fortuna Sittard and VVV Venlo let the opponents keep the ball for more time on average. This is a good indicator for that high pressing is not Utrecht’s first intention when defending: they do not tend to rush out on the attackers or overload the opposite half of the pitch with many players, instead, they allow them to come forward so that they leave some empty areas behind which the Utrecht attackers can then occupy. We can witness an example in the next snapshot from the game against Feyenoord in 2019 August: all the Utrecht attackers drop back to their half of the pitch and the two wingers only start to press intensively when the ball crosses the line.

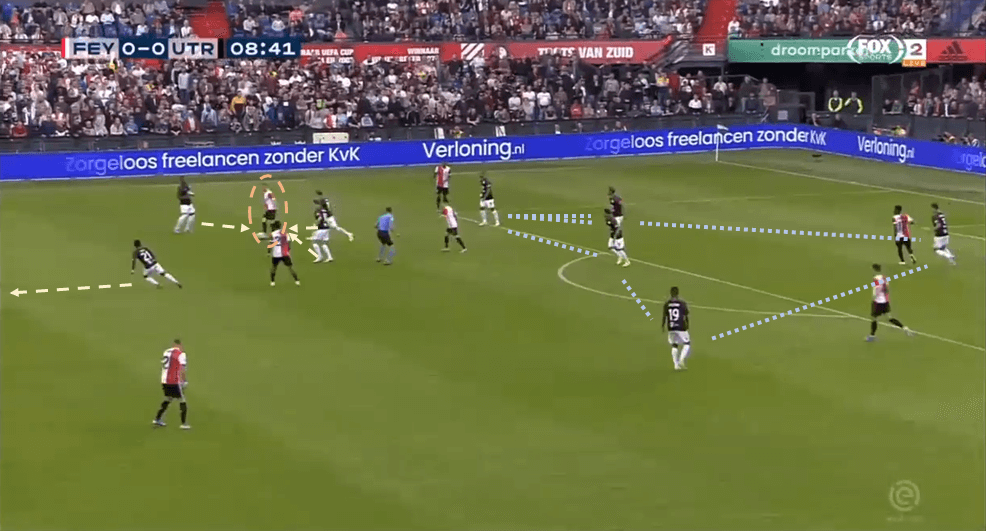

We can also take another situation from the same match, in which the ball-carrying opponent is already near to the Utrecht penalty box when three attackers rush on him and together they manage to recover the ball. It is fascinating to see that the striker Issah Abass already initiates a sprint towards the goal even when the ball is still on the feet of the opponent – this shows perfectly that the timing of the pressing is intentional and fundamental in Utrecht’s strategy.

Another telling fact is that Utrecht finished at the bottom of the league regarding the number of interceptions. Their 35.83 per 90 figure was 18.95% worse than the most effective team (Heerenveen) and was 12.82% below the league average. They were also rather poor in the number of duels, both from a defensive (-4.92% compared to the average) and an offensive (-1.44%) aspect and in the air also (-19.20%). All of these figures suggest that Utrecht aims to keep the ball for as long as possible and when they do lose it, they are not effective enough in gathering it back or at least stopping the opponent as soon as possible.

Transition

Based on their defensive approach – allowing the opponent to progress until the middle third and try to gain back the ball there , Utrecht puts a great emphasis on counter-attacking actions. The team’s 5 goals scored from such situations is 10% above the league average and is exactly 10% of their total goals. Thanks to the creative and agile midfielders and the quick forwards up front (mainly Gyrano Kerk), counter-attacking is definitely one of the core elements of Utrecht’s tactics, but not something that the team can always count on. In the previous season, they had the fewest ball losses per 90 minutes (93.01) in the whole league, and, consequently, they registered only 72.63 recoveries on average. This means that although the team is very dangerous from quick transitions, they just do not have the opportunity to operate with it too often. In all other cases, when the opposing defence is more organised, Utrecht’s transition from defending to attacking is realised in a much slower, patient build-up, looking for the most desirable opportunity.

Attacking

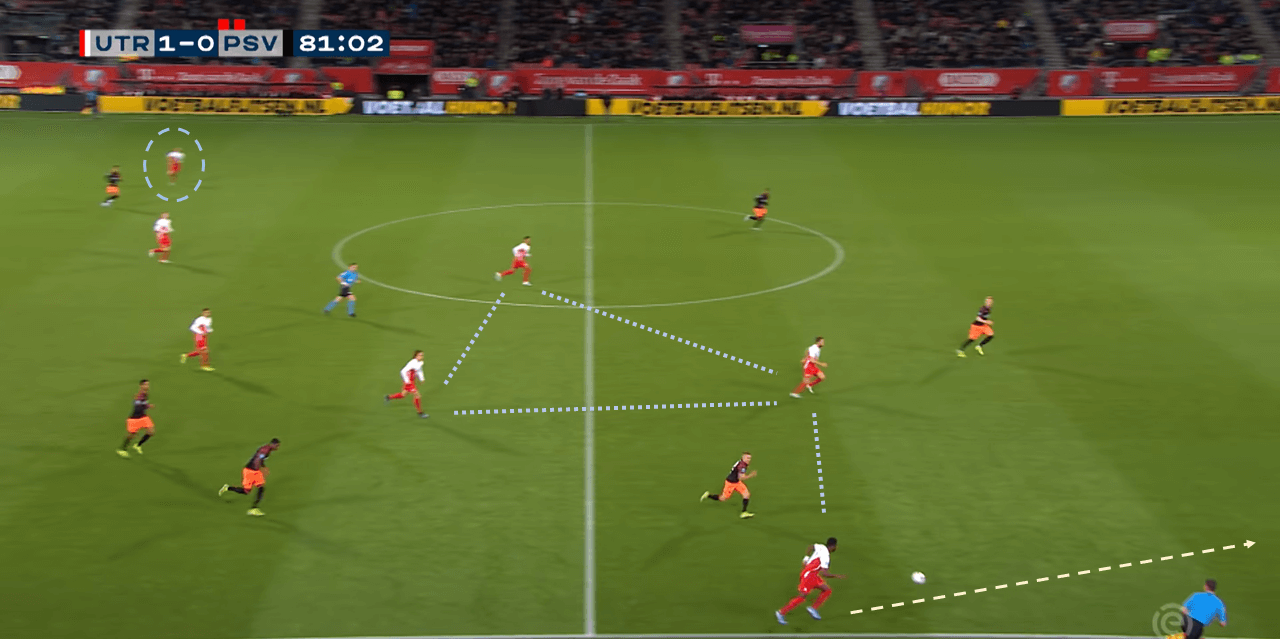

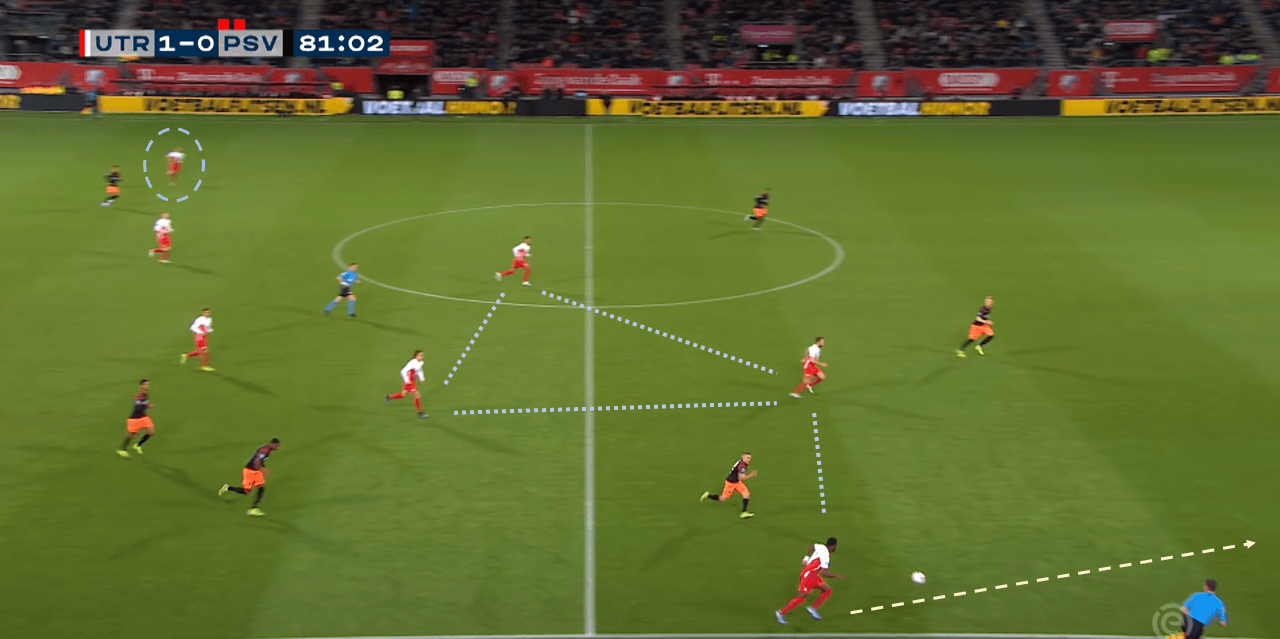

As already mentioned and illustrated in an earlier section of the analysis, the majority of the attacking actions run in the middle and the right-wide areas of the pitch. In the first half of the season, the team tried various offensive formations in which Gyrano Kirk was the only fixpoint, playing in all of the first 20 matches in the Eredivisie. Even though the shape of the team was changing frequently and they played without classic wingers in many cases, Kirk was always giving width to the team on the right flank. As we can see in the below situation from Utrecht’s game against PSV in 2019 October, the team often used an asymmetrical formation, with the quick Dutchman bursting into the wide areas supported by three midfielders but no one on the left side of the pitch. This way, the team was able to stay more organized when going back to defending, without giving up both flanks for the sake of attacking.

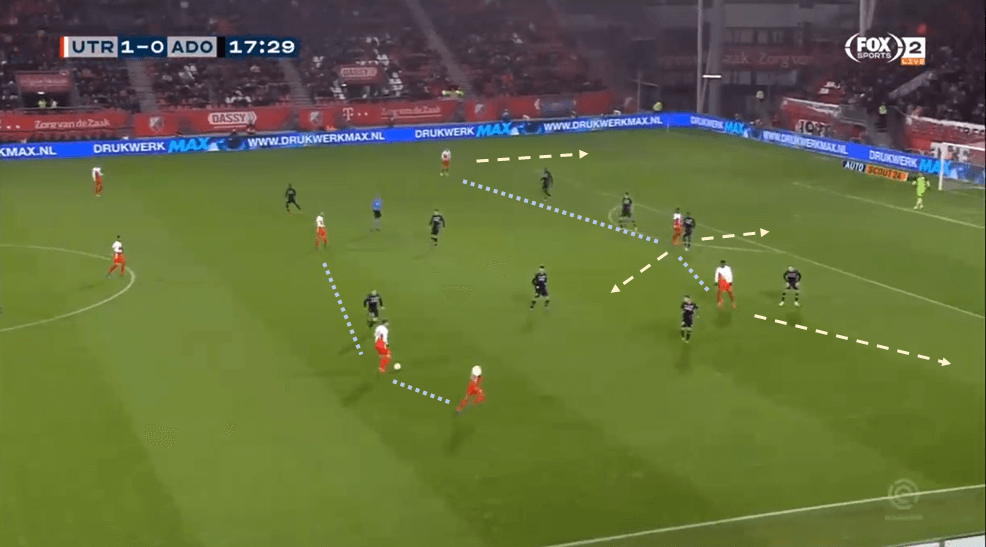

In the second half of the season, with the arrival of Kristoffer Peterson to the left-winger position and the absence of Bert Ramselaar from the midfield due to injury, Utrecht started to apply a more balanced 4-3-3 – illustrated in the below snapshot from Utrecht’s home game against ADO Den Haag in 2020 January –, inherited from Erik ten Hag after his departure to Ajax in 2018. This shape let Utrecht open up even bigger spaces in the pitch which was beneficial for their possession-based, rather slow and well-thought attacking style.

3) Youth development

As already declared, it is not a coincidence that the recent upsurge of the club started in the 2015/16 campaign: with Erik ten Hag, Utrecht appointed one of the brightest young minds of the Netherlands. At the same time, investing in the youth academy became an even higher priority than before, with significant developments in the areas of scouting, training grounds, and other youth facilities. In 2015, the FC Utrecht Academie received a four-star rating from the Dutch Football Association (KNVB), the highest achievable classification for any academies which brought an additional recognition for the club both on the domestic and international level. Jong Utrecht plays in the second tier of Dutch football (Eerste Divisie) and finished in the decent 12. place in the 20-team league, overcoming the reserve teams of both AZ Alkmaar (14.) and PSV Eindhoven (18.).

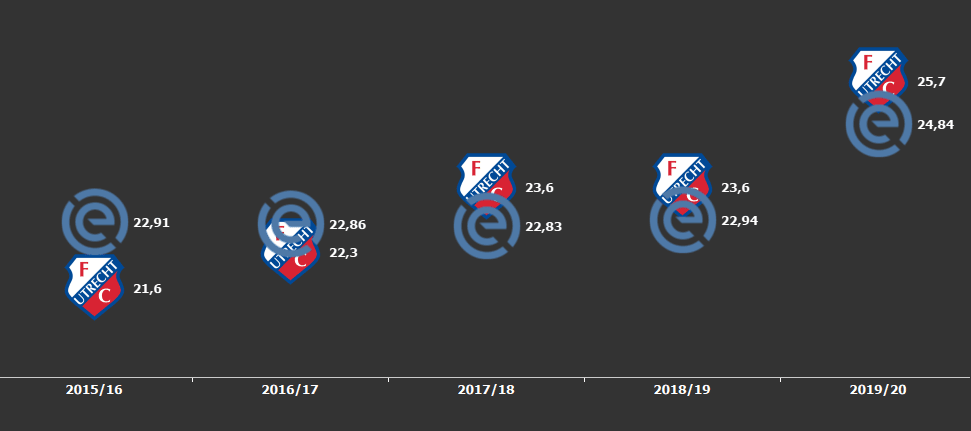

After taking a look at the academy, let’s investigate how the youth players fare on the highest level as well. In the above chart, it is transparent that the Utrecht squad’s average age has changed a lot throughout the last five seasons. In 2015/16, Utrecht was one of the youngest teams of the league with 21.6 years which, as we will see later, was basically down to the fact that plenty of reserve players got the chance to join the senior squad. In the following years, the average age went through a significant increase, driven by two reasons: from one side, fewer academy talents were integrated into the first team, and from the other, many of those youngsters who joined the team in 2015 (or before) were neither sold nor replaced by a new player. As a result, for the 2019/20 campaign, the average age went up to 25.7 years, with this having the third oldest squad in the league, only topped by bottom-two ADO Den Haag and RKC Waalwijk.

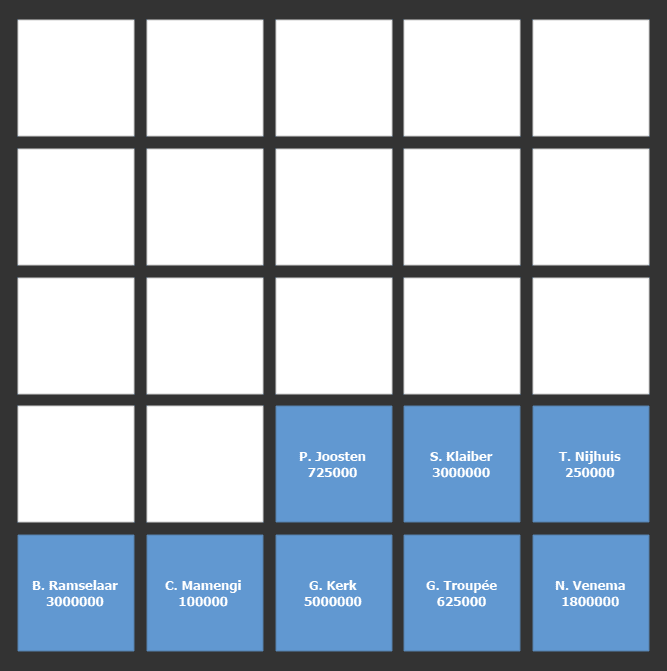

If we go deeper into measuring the youngsters’ involvement and performance in the first team, in the above matrix, we can see that former academy players gave 32% of the 2019/20 Utrecht squad. The situation is a bit less rosy if we consider that from these 8 players only 3 were regular starters (Sean Klaiber, Bart Ramselaar and Gyrano Kerk) playing a total of 5525 minutes in the Eredivisie.

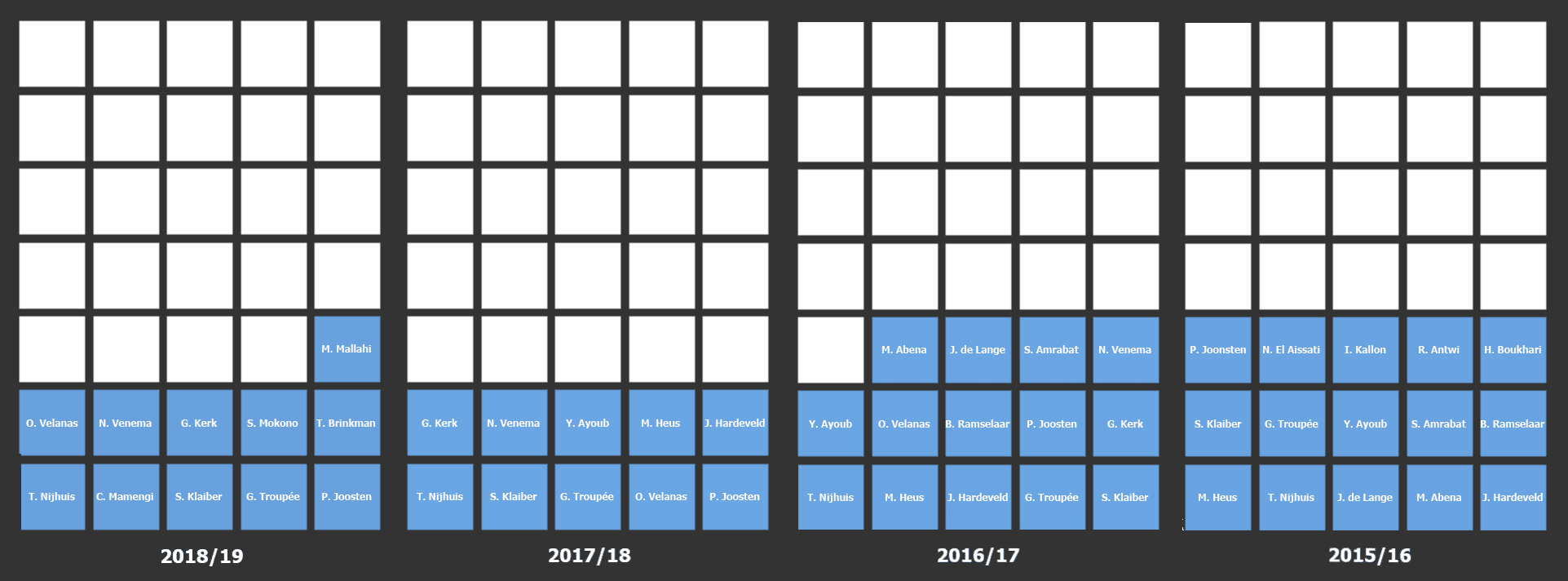

In line with what we have seen earlier regarding the changes in the average age of the team, the number of academy players in the squad also seems to be on the decline, as visualized in the next charts. In 2015/16, 42.86% of the personnel were coming from the U21 (or U19) team, with a slight drop next year (40%) and a considerable decrease in the following campaigns (28.57% in 2017/18 and 31.43% in 2018/19). However, having a squad with every third member coming from the academy is still a respectable achievement from a club outside the big three and, besides the professional point of view, this strategy has a lot of financial reasons behind as well.

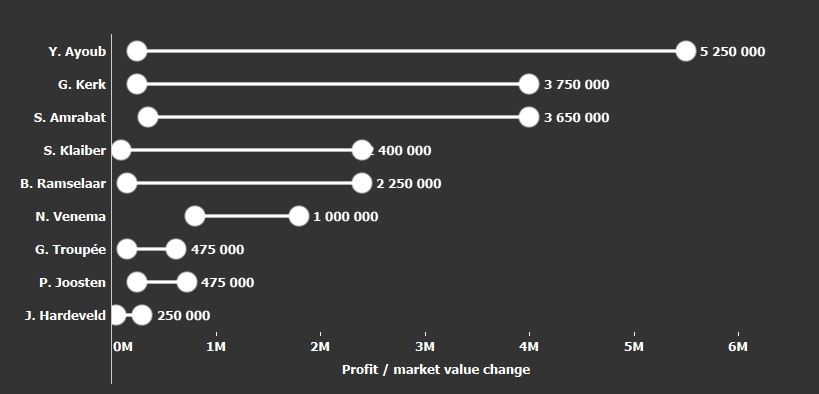

Although many academy youngsters were granted the trust to become a part of the senior squad, not all of them managed to earn their places in the starting eleven in the long run: only 9 of them played more than 600 minutes in the first team in the last five years. However, building a team upon homegrown youngsters, thereby getting closer to the fans and strengthening the cohesion inside the team, is not the only reason behind the academy approach in general: profitability and sustainable growth are just as important if not more. The below graph illustrates how the market value of youngsters with 600+ minutes changed over the years.

It is crystal clear that all the young prospects had a significant increase in value since 2015, adding up to a total of 19,500,000 EUR for the 9 players. 6 of them are still members of the current squad but it will be no surprise if a few of them were also on the move, with Gyrano Kerk receiving the most interest from European clubs, most recently Celtic Glasgow. Should the Scottish giants or any other team aim to buy the talented winger, they will most probably have to pay more than his current 4,000,000 EUR market value which suggests that Utrecht is ahead of a great deal once again.

Conclusion

Growing up to the level of the ‘Traditional Three’ of the Netherlands is not something that can be achieved overnight. Recently, AZ Alkmaar has been the most progressing team from outside the top three, and their success is merely down to their stable background both from the professional and the financial aspects. FC Utrecht has a similar approach, as they also put extra effort into youth development, have a long-term strategy and a transparent vision.

In this analysis, we investigated the club’s statistical, tactical, and developmental performance, paying special attention to the 2019/20 season but also giving a glimpse on the previous campaigns. We saw that the team has a few weak areas in their squad which will definitely be in focus when the next transfer window opens. Based on the statistics, Utrecht is very effective in finishing their offensive actions but can be rather vulnerable in the back which is visible in their low number of duels, interceptions, and recoveries. In the season behind us, head coach John van den Brom used several different formations, in some cases with an asymmetrical setup (with more emphasis on the right side of the pitch) but he seemed to settle with the traditional 4-3-3 by the end of the campaign.

The main advantage is still in youth development. We saw that in the last five years, Utrecht was successful in integrating their academy players into the first squad, and this approach, besides the professional and moral success, resulted in a significant amount of profit as well. No wonder that FC Barcelona have already initiated setting up a collaboration with FC Utrecht, in which the Catalan giants would loan out some of their youngsters to the Dutch club so that they can get playing minutes on the top level and taking their first steps in their way of fulfilling their potential. From what we have seen so far from the club, Utrecht is just the ideal place for the Barcelona alumni.

Tired of commentary which tells you nothing new about the action in front of you? Well, we’ve got a solution. We’ve partnered with HotMic to provide live commentary and analysis of the best football action from around the world, and we’re covering some of the best matches in the Bundesliga this weekend! Download the HotMic app and sign up using the code ‘TFA2020’ to keep up-to-date with all our coverage – we’ll be covering the Premier League, La Liga and Serie A as well when they resume, so make sure to follow us on the app, and get in-depth analysis and tactical knowledge from the best analysts in the business!

Comments