Haiti had a long road in qualifying for this year’s World Cup in Australia and New Zealand. Les Grenadières had to come through CONCACAF’s pre-qualification tournament before entering the qualification Championship. In the final group stage, they were drawn with the USA, Mexico and Jamaica. Finishing third in the group, behind the USA and Jamaica, secured them a spot in the Inter-Confederation Play-Offs.

Two impressive play-off wins against Senegal and Chile were fought to send the Women’s national team to their first-ever World Cup Finals. On top of the number of games, Haiti also had the obstacle of playing all of their games away from home due to the political instability in their home country.

The route out of Group D will not get any easier when they travel to Queensland for their opening match against England. After the Lionesses, China and Denmark await. All three are ranked in the top 15 in FIFA’s World Rankings. This World Cup represents a formidable but exciting challenge for the competition debutants.

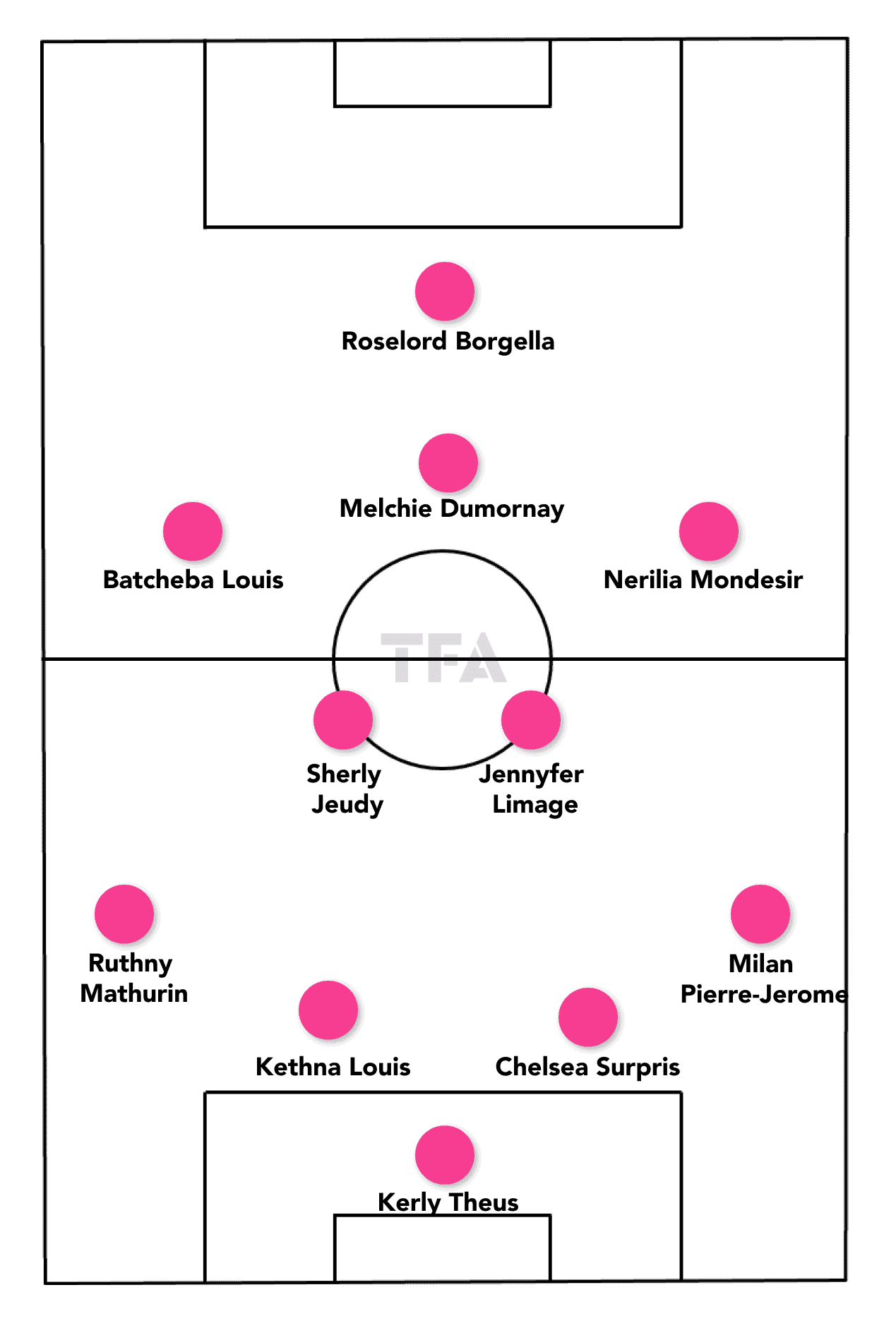

Predicted Starting XI

Head coach Nicolas Delépine’s preferred formation in qualifying was a 4-2-3-1 in possession and a 4-4-2 mid to low block when out of possession. Against the top teams, it has been counterattacking from this 4-4-2 block which has brought them the most joy. Delépine is from and based in France, where he combines his international coaching duties with managing Grenoble Foot 38 in France’s Second Division.

Haiti are, unsurprisingly, made up heavily of players based in France. Delépine has selected over half of his squad with players from his homeland. Jennyfer Limage, Maudeline Moryl and Darlina Joseph are all based in France and have played under Delépine at club level.

Perhaps the biggest selection headache for head coach Delépine comes at centre-back with the injury to key player Claire Constant. The Torrense centre-back misses out on the World Cup having torn her ACL earlier this year. Constant was ever-present in qualifying. Her absence throws into doubt the makeup of the back four.

Kethna Louis, who has played at right-back in qualifying, could partner Chelsea Surpris in the centre of defence. However, Delépine has tried several defensive combinations since his star defender has been sidelined, making it unclear who his preference is. If Surpris does move to centre-back, her preferred position at club level, that would pave the way for someone else at right-back. This could hand a start to George Mason University star Milan Pierre-Jerome.

In attack, Nerilia Mondesir and Batcheba Louis are two exciting wingers. Typically, Louis plays on the left with Mondesir on the right but they have been known to switch flanks. If there is any one player in the Haitian team that could light up the tournament, it is Mondesir. The Montepellier attacker has scored 18 goals for her country in 12 appearances.

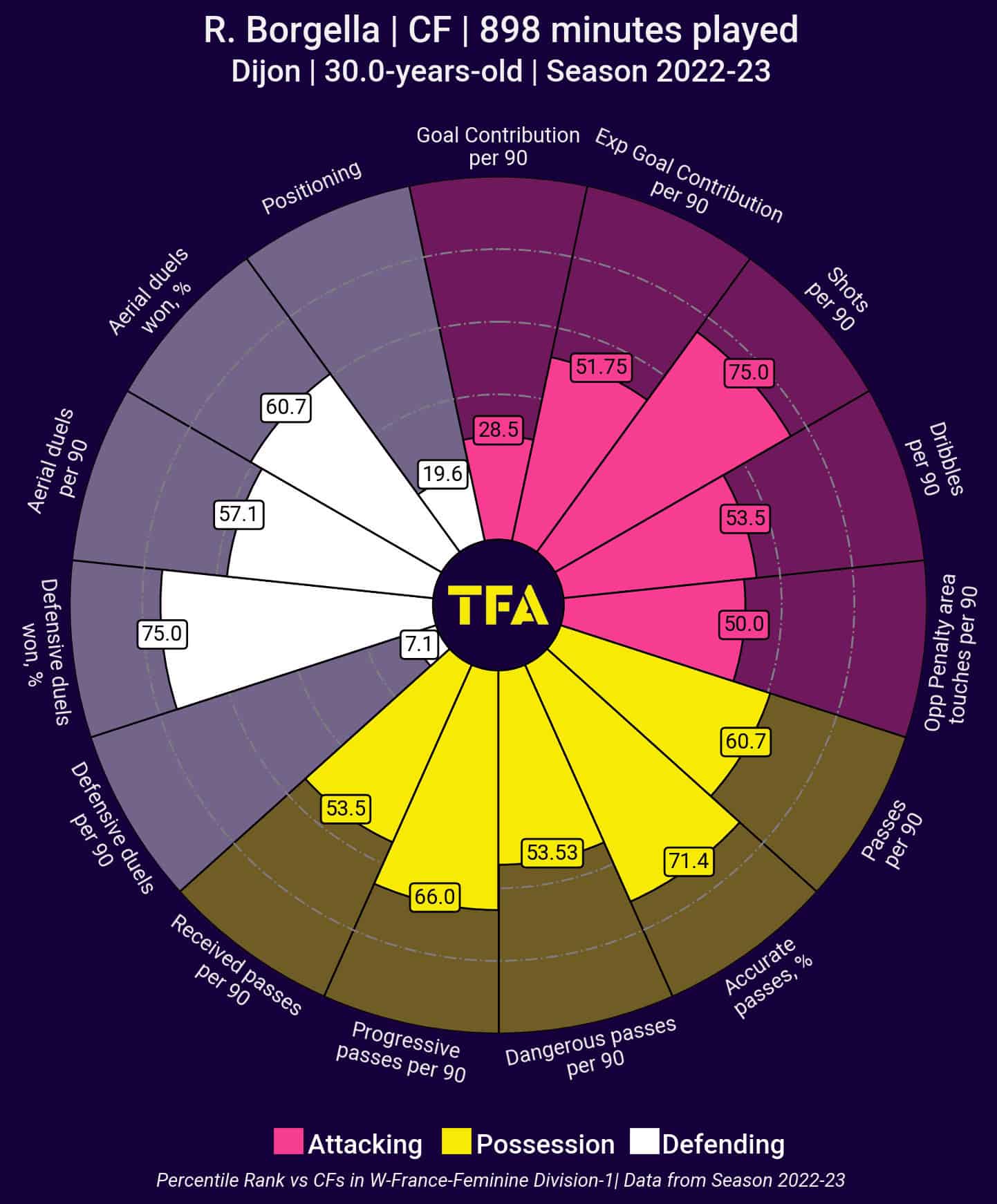

Another threat in attack is Roselord Borgella. The 30-year-old Dijon forward was Haiti’s top scorer in the CONCACAF Championship Qualification Tournament with 11 goals in just four games.

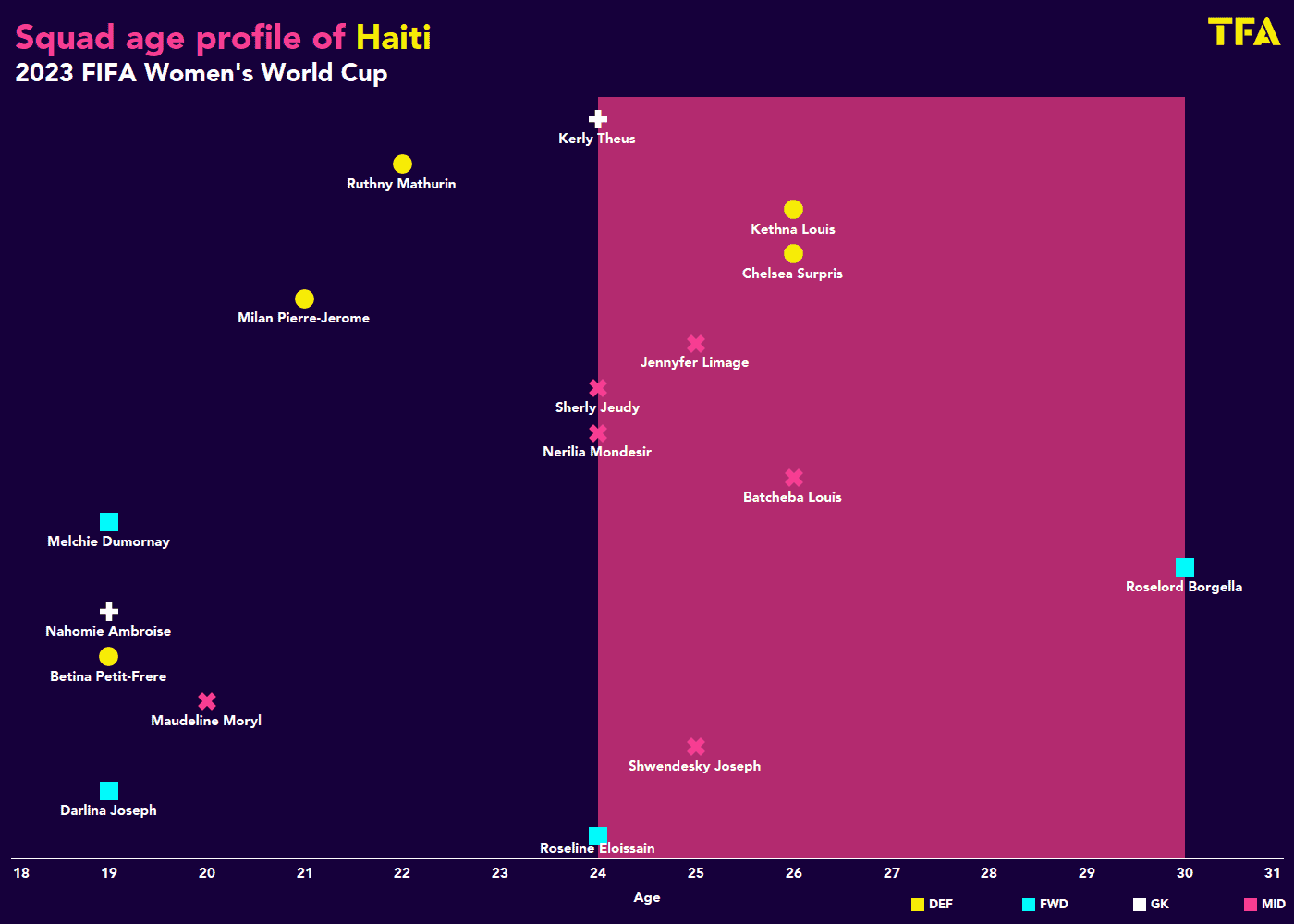

Haiti enter this tournament with no player over the age of 30. Whilst they have a good mix of players that should be in their prime and young players, they severely lack an older, experienced head. Of course, with this being their first-ever World Cup, they go into it with no players having experienced it before.

Whilst this is not ideal for this year’s tournament, it may well aid them in four years’ time. With the oldest player, Borgella, just 30 years old, every player could expect to still be playing the next time the World Cup comes around. Perhaps this experience will spur them on to long-term, sustained success for their national team.

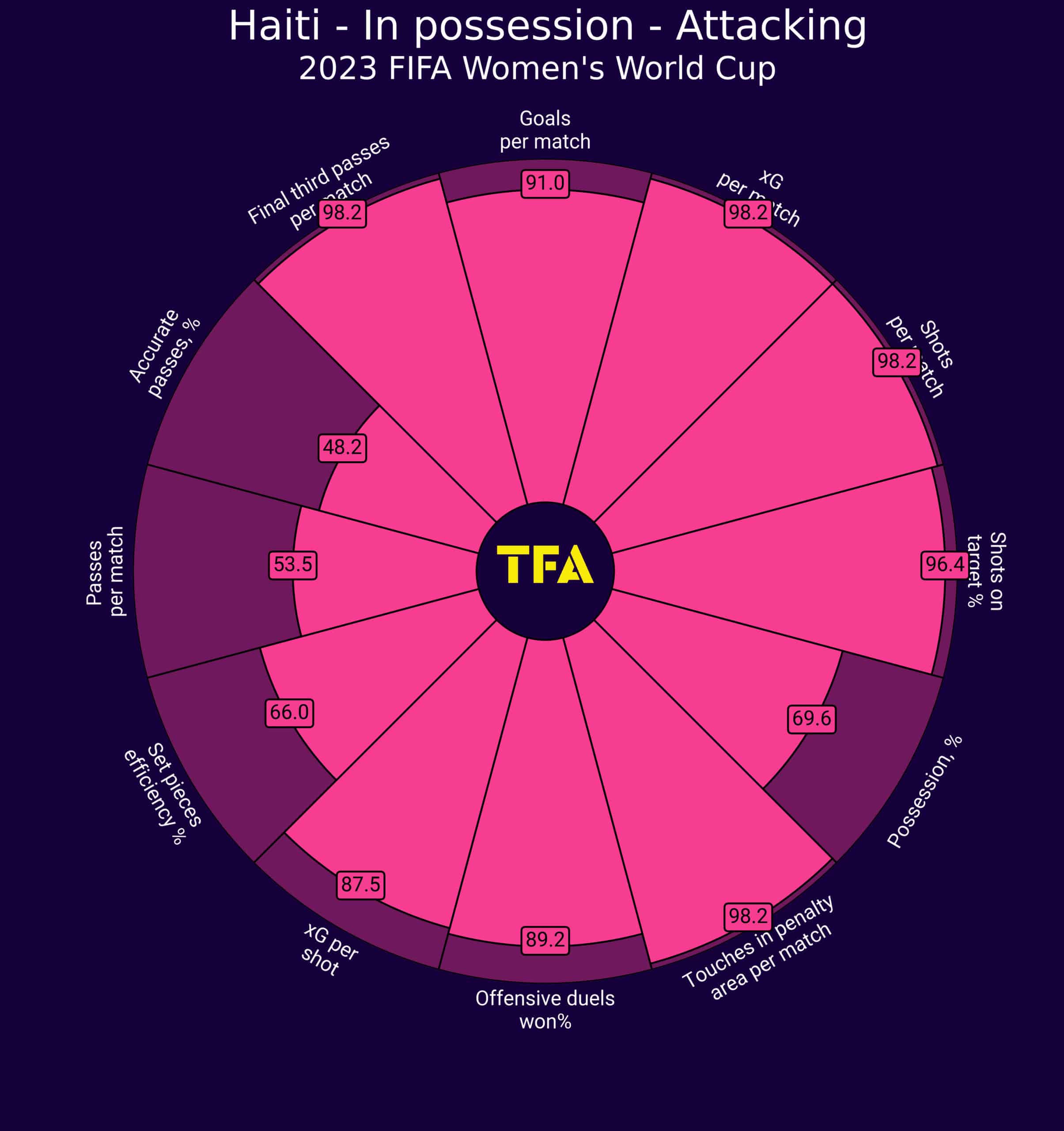

Attacking Phase

When all of Haiti’s qualifying games are taken into consideration, their metrics in attack are very impressive. These statistics include matches in the initial qualifying group stage where Haiti racked up 44 goals in four games. Amongst those games, a 21-0 thrashing of minnows the British Virgin Islands.

A good example of their exaggerated statistics is in possession. Although they rank highly amongst all teams that have qualified, when they have faced the calibre of teams they’ll meet at the finals, their ball possession is far lower.

In Haiti’s matches in the final qualification group and the Inter-Confederation Play-Offs, the games that best represent the level of opposition Haiti will face in the finals, Haiti averaged just 39% possession. They did not have more of the ball than their opposition in any of the games and went as low as 29% in their vital 3-0 win against Mexico.

As will be covered in the transitions section, Haiti’s main form of attacking threat, against the top teams, has come from counterattacks. This section is going to analyse how they position themselves during more sustained positional attacks.

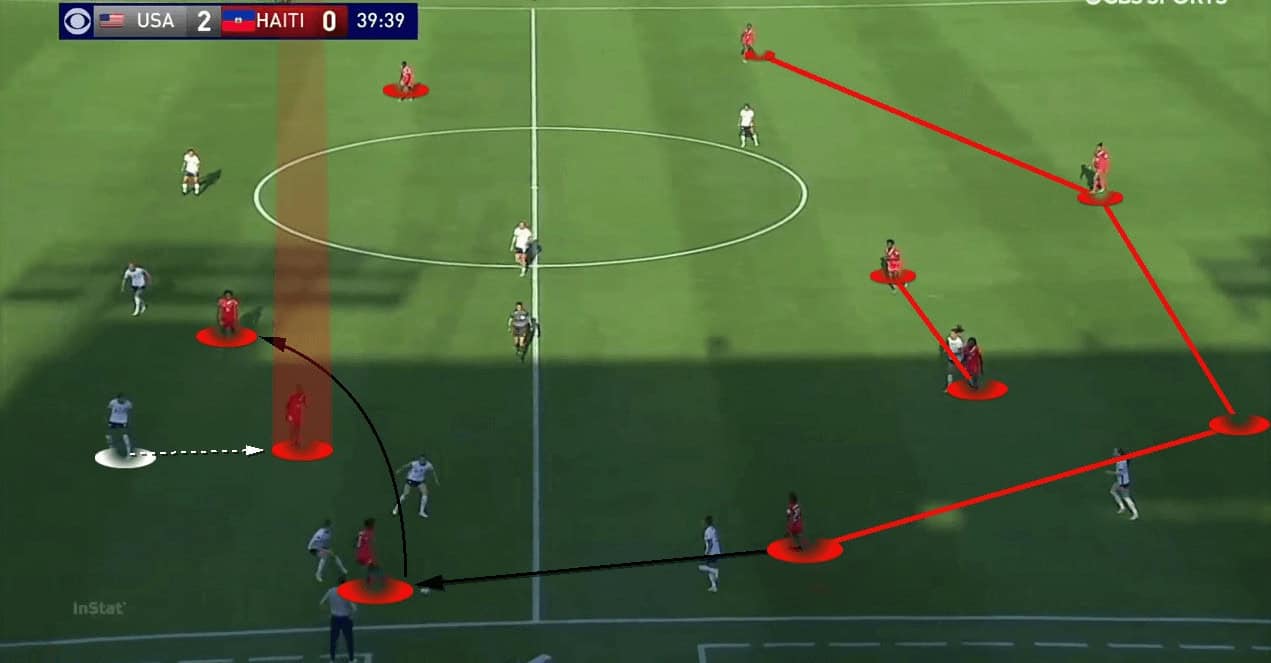

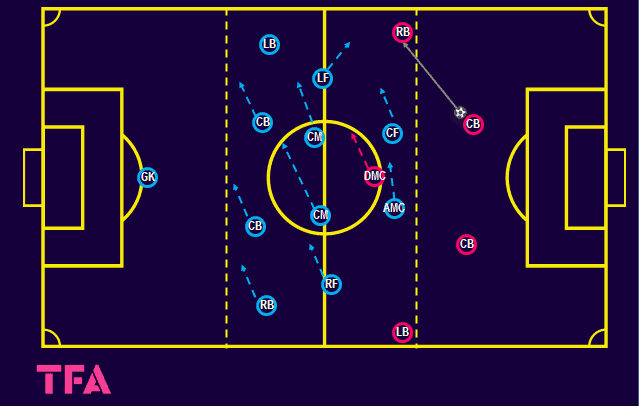

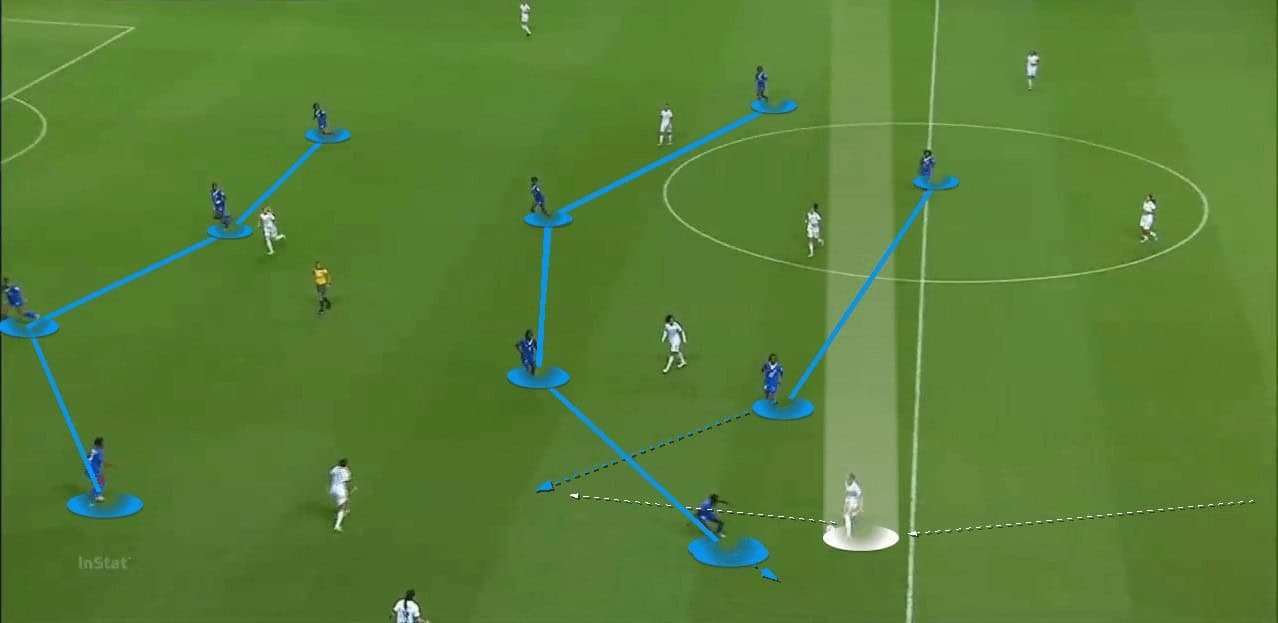

The above image shows Haiti’s structure in attack. In most games, it has been a 4-2-3-1, with a defined attacking midfielder. In other games, it has been a 4-4-2 with the forwards alternating who drops in between the lines. In this instance, against the USA, Haiti were often in a 4-4-2 but implemented the same principles as their usual 4-2-3-1.

A key part of Haiti’s attacking set-up is the positioning of their attacking midfielder, or one of their forwards if they play in a 4-4-2. This player drops into the half-spaces behind the opposition’s midfield line. This movement is facilitated by the two central midfielders playing narrow and dropping deep. As shown in the image above, the two midfielders show for the ball much closer to their backline than their forwards.

As can be seen on the opposite side of the pitch, Haiti’s ball-far wide-midfielders remain high and wide. This helps to pin the opposition’s backline, preventing them from squeezing the space where Haiti want their attacking midfielder to receive.

In the example above, the attacking midfielder did not receive the ball. Instead, she was used as bait to make the ball-near centre-back jump. This left Dumornay one on one with the ball-far centre-back. Due to Dumornay’s pace, the centre-back was left with no option but to backtrack towards goal. This allowed the speedy forward to drive at the opposition’s defensive line with the ball at her feet whilst being supported by her high right midfielder, Mondesir. This play led to Mondesir receiving the ball in the box before being brought down to earn Haiti a penalty kick.

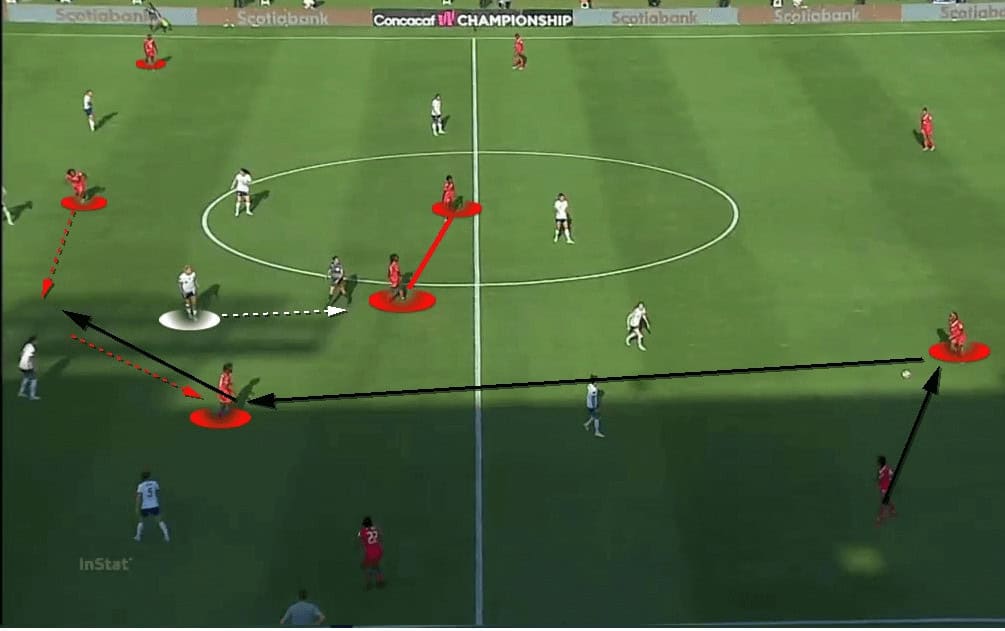

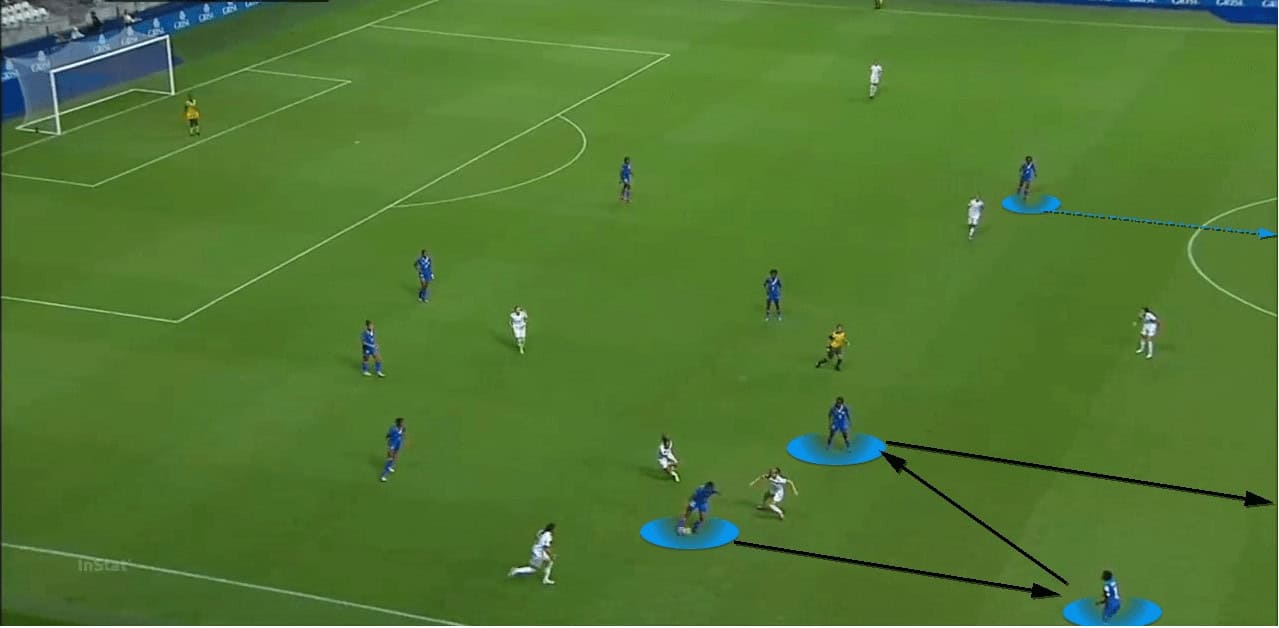

This image, from the same game against the USA, again shows the importance of the positioning of Haiti’s central midfielders, Limage and Jeudy. As the centre-back Louis was about to receive the ball, both midfielders dropped off towards her. This slight movement drew the USA’s ball-near defensive midfielder towards the ball.

As the defensive midfielder was moved, the centre-forward, in this instance Borgella, drifted into the pocket of space created in the half-space. The centre-back who was marking her cannot follow her as this would leave too much space in-behind, especially with the pace of Dumornay.

This allows Borgella to get on the ball and immediately turn towards the goal. If her central midfielder was just five yards higher, the USA midfielder would be able to cover both players and this space would not exist. As Borgella received the ball, she played in her strike partner. The ball near centre-back was slow in deciding to drop off. This left Dumornay one-on-one with her marker and bearing down on the goal. The striker skillfully went past her mark and shot at goal for one of Haiti’s best chances of the match.

Defensive Phase

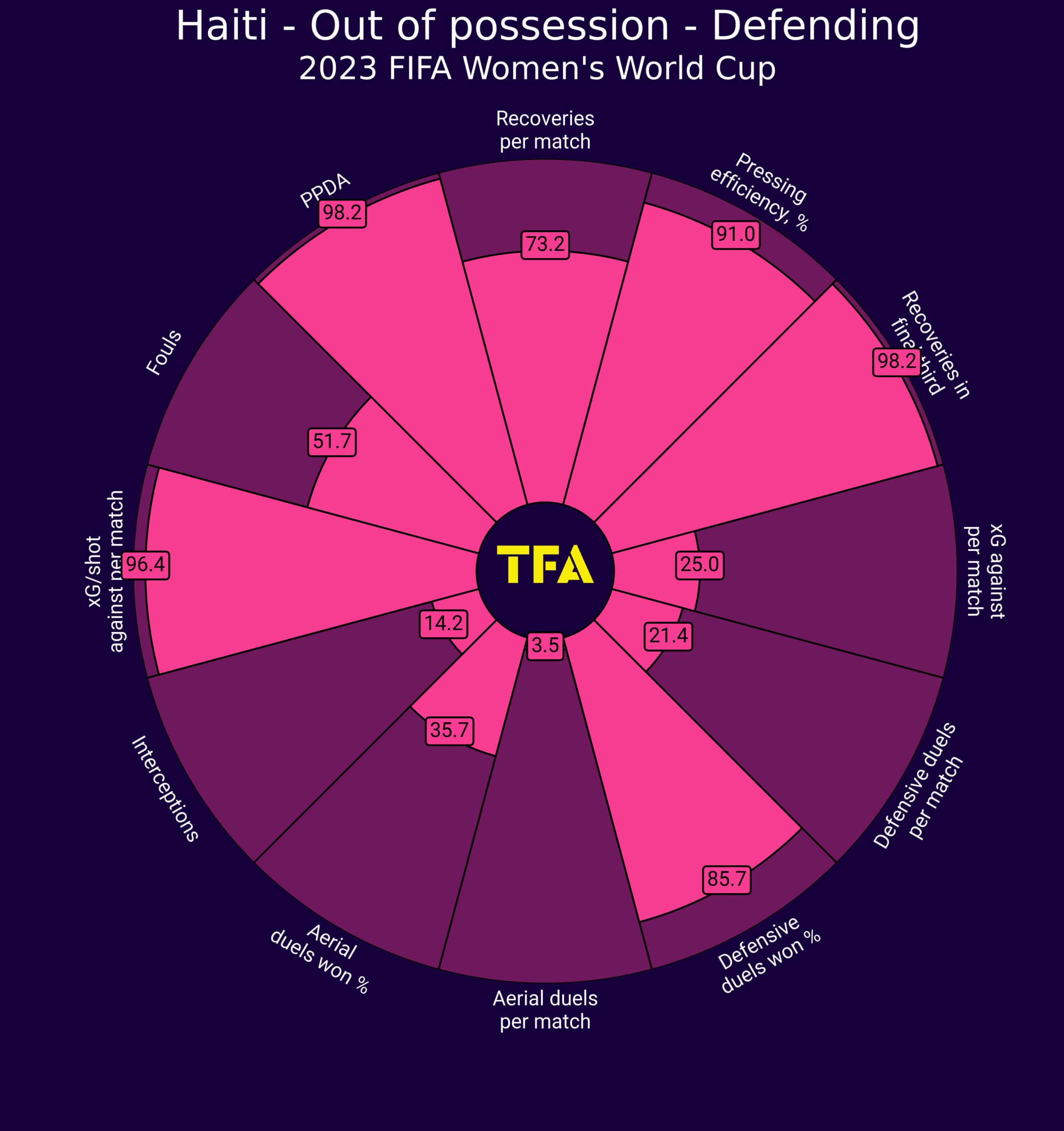

As with Haiti’s attacking metrics, their defensive statistics are slightly skewed from what we can expect to see from them when up against the best in the world. The best example of this is their recoveries in the final third. To highlight this disparity in figures, we can look at their qualifying match against Mexico.

During the defensive phase, Delépine sets his side up in a 4-4-2 block. The aim is to draw the opposition out, whilst remaining compact and regain possession in the middle third. Against Mexico, Haiti regained possession in the middle third 30 times. For comparison, they only won possession back in the attacking third five times. This shows Haiti’s differing approach when facing tougher opposition. Haiti will most likely not be a high-pressing team when they face the world’s fourth-best team.

With Delépine playing a 4-2-3-1 in attack, the positional adaptions from the attacking to the defensive phase are simple. The attacking midfielder just plays slightly higher alongside the central forward. The newly formed front two usually drop off to just inside the edge of their attacking third during the opposition’s build-up phase. The backline are around 10 yards inside their half with the midfield playing across the halfway line.

Although the starting positions are what you would expect of a mid-block, Haiti do not usually engage the ball until it reaches their half. When it does, all 10 outfield players are still behind the ball and in their original structure. The condensed shape, and screening movements of the front two, prevent the ball from being easily passed into the middle of the pitch and prevents them from being too exposed in-behind. It also, as we will see in the next section, draws the opposition out to create space for Haiti to counterattack.

The priority of the two forwards in the build-up phase is to prevent the opposition ‘6’ from getting on the ball. To do this, they narrow to prevent the ball from being played between them. The closer the ball is, the closer together they get.

This prevents their own central midfielders from being dragged out of position and allows them to occupy the centre of the pitch. Even if the front line was to be broken, Haiti would still be comfortable. The receiving player would still have eight bodies, in position, to break down whilst being pressed from behind.

To facilitate this, the forwards allow the ball to be played wide, into the full-backs.

When the ball goes into the wide area, it is the wide midfielder’s responsibility to prevent it from being progressed. The above image shows left-midfielder, Louis, both stopping Mexico’s right-back dribbling forward with the ball and blocking any pass into their right winger.

Haiti’s positioning in this moment is, again, completely zonal, which avoids the opposition’s movements from being able to drag them around. Two diagonal lines are formed. The first, between Louis and the ball-near forward. If they were in a completely straight, horizontal line, they would have to be much closer to one another to prevent the ball from going between them.

The second line connects Louis with her central midfielders. The ball-near midfielder, Limage, is well-positioned to screen a pass into the forwards behind her. She can also step forward and apply quick pressure if Mexico’s ‘6’ gets on the ball.

The ball-far midfielder, Jeudy, deepens off further still. Again, this helps screen any longer balls into the Mexico forwards. This also protects Haiti against a switch of play. If the ball was to be switched, say to Mexico’s left-back, Jeudy would be able to shift across and still be underneath the ball. If her starting point was higher, the left-back receiving and driving forward would take her out of the game.

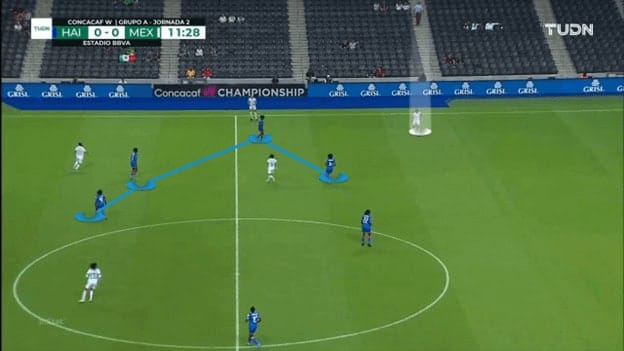

The image above shows Haiti, in their 4-4-2 block, setting a pressing trap against Mexico — a successful trap, from which they eventually went on to score the opening goal. The play started with Mexico’s goalkeeper on the ball and Haiti’s forwards positioned on the edge of their attacking third. Mexico were allowed to progress the ball with little pressure all the way to the halfway line.

With Mexico being frustrated with a lack of passing options into midfield due to Haiti’s organisation, their left centre-back drove forward with the ball at her feet. Haiti’s left midfielder, Mondesir, prioritised cutting off the pass to Mexico’s left-back. This encouraged the centre-back to progress further with the ball.

When the centre-back entered Haiti’s half, and just beyond the first line of pressure, Haiti collapsed on her and regained possession before springing a counterattack.

Transitions

In Haiti’s crucial 3-0 win against Mexico, where they had less than a third of the ball, all three goals came from set plays. The opening two goals, both penalties, were the result of counterattacks. These two statistics give us another clear understanding of what to expect from Haiti in the finals.

As soon as Haiti regain possession from their mid or low block, the central forward player drops into the pocket to show for the ball. As the image above shows, the two closest, and more lowly positioned attacking players, then full-on sprint in behind the opposition. The next action, if the receiving player is facing forward, is to put the ball in behind the opposition’s backline.

In this example, because of the pace of the forward players, this simple tactic creates a two-on-one and a race towards the goal.

This image shows the initial phase of Haiti’s counterattack against Mexico that led to a penalty and their opening goal. It occurred after the pressing trap described in the defensive phase section. Haiti’s Borgella has just dispossessed Mexico’s left centre-back.

Borgella’s next action was to immediately play into her wide-midfielder, who dropped towards the ball as soon as it was won. Unlike in the previous example, Mondesir has pressure from behind. This means she is unable to turn on the ball and play it in behind the opposition’s backline herself. Instead, she drops it off to a supporting midfielder and spins in behind.

The midfielder puts the ball in behind Mexico’s left-back for Mondesir to chase. Dumornay, just out of shot, and Louis, both burst forward to support the attack. The devastating pace of the attack means Mexico are unable to recover their shape and this eventually leads to a Haiti penalty and the opening goal.

Defenders

Haiti have conceded eight goals in their previous five competitive outlines and only kept two clean sheets in their previous 10. With one of their stalwarts at centre-back set to miss out, keeping goals out, or even avoiding a heavy defeat, will be at the forefront of Delépine’s mind. Pierre-Jerome, Louis, Surpris and Ruthny Mathurin are predicted to start, but it could be just about any four of the seven defenders on the field from minute one in Australia.

Midfielders

Limage and Jeudy, who will play as the two central midfielders, are two stalwarts of the side. They protect the backline well and give the team defensive stability. They are good at utilsing their teammates’ speed by playing accurate long balls behind the opposition for their forwards to run onto.

Attackers

Shwendesky Joseph may feature in the tournament after being recalled for recent friendlies. Joseph, who plays for Russian side Zenit Saint Petersburg, missed the Inter-Confederation Play-Offs due to injury. Her speed and coolness in front of goal could be relied upon by her French manager.

With the possible exception of Borgella, who has a real eye for goal, Haiti’s attack has plenty of pace. Several of Haiti’s front players are also very good at dribbling at the opposition. These two attributes have led to several penalties, including against Mexico and the USA, due to the opposition being unable to defend against them. These features of Haiti’s attack make this young team entertaining to watch and such a threat on counterattacks.

Key Player

Based on her goals scoring, Roselord Borgella could be a key player for Delépine and his side. Borgella is expected to be the oldest starting player on the national team. She has three years of experience playing in Europe, including with Dijon in France’s top division. Although she perhaps lacks the same speed and dribbling ability as her teammates, her link-up play and goal-scoring threat make her a player to watch at the tournament.

Mondesir and Dumornay will also be players with the potential to light up the tournament. Their speed and trickery on the ball will unsettle any defence.

Tournament Prediction

Haiti will be looking forward to their first major tournament, having never qualified for either the World Cup or the Olympic Games. This is the first time in 32 years that they have even made it out of CONCACAF’s initial qualifying stage. Ranked #53 in the world, their highest-ever ranking, this is undoubtedly the Caribbean country’s most successful female team in history.

However, with China and two of Europe’s top teams in their group, the challenge ahead of them is daunting. To put Haiti’s task in perspective, China, ranked at #14 in FIFA’s World Rankings, are the lowest-ranked opposition they will face. In November, Haiti were heavily beaten 5-0 by Portugal who, at the time, were ranked #21 in the world.

Haiti’s best hope is that through their tactical organisation, they can frustrate teams. If their opposition starts leaving holes in their backline to throw more players forward, the pace of Haiti’s attacking players can exploit them.

Although they have proved many doubters wrong just to get to where they are today, being competitive against any of their group opponents would be seen as a success for Les Grenadières.

Comments