England’s World Cup adventure came to an end with a semi-final defeat to Croatia, but their performance at 2018’s finals was worthy of praise. Perhaps their finest team display came in the quarter-finals, where they defeated Sweden 2-0 to reach the last four.

Going into that game, Sweden had hammered Mexico 3-0 to top a group also containing Germany and South Korea before eliminating an intriguing Switzerland side in a fairly consummate 1-0 second round win. In the process, Janne Andersson’s side established themselves as a defensively resolute outfit with an attacking style built around direct play and concise counter-attacking.

Sweden’s approach in attacking transition was expected to be key in their quarter-final with England, where it was generally accepted that they would not dominate possession. However, they were unable to pose a consistent offensive threat on the day.

SWEDEN’S COUNTER-ATTACKING THREAT

While they may not have scored many goals as a direct result of their counter-attacking, this particular sub-section of Sweden’s game was important to their World Cup progress. Their ability to secure the ball in transition and then launch swift, co-ordinated breaks helped them to open up their opposition, get up the pitch and, on occasion, create scoring chances.

Their effectiveness in attacking transition actually began with their compactness in the defensive phase. Andersson’s side lined up in a compact 4-4-2 block with a position-oriented defence that maintained their shape and reduced gaps for the opposition to play through. This structure aided them in attacking transition as they often had numbers around the ball, which they used to exchange quick passes over short distances. These exchanges were difficult for the opposition to cut out, enabling Sweden to orchestrate counter-attacks immediately after regaining possession.

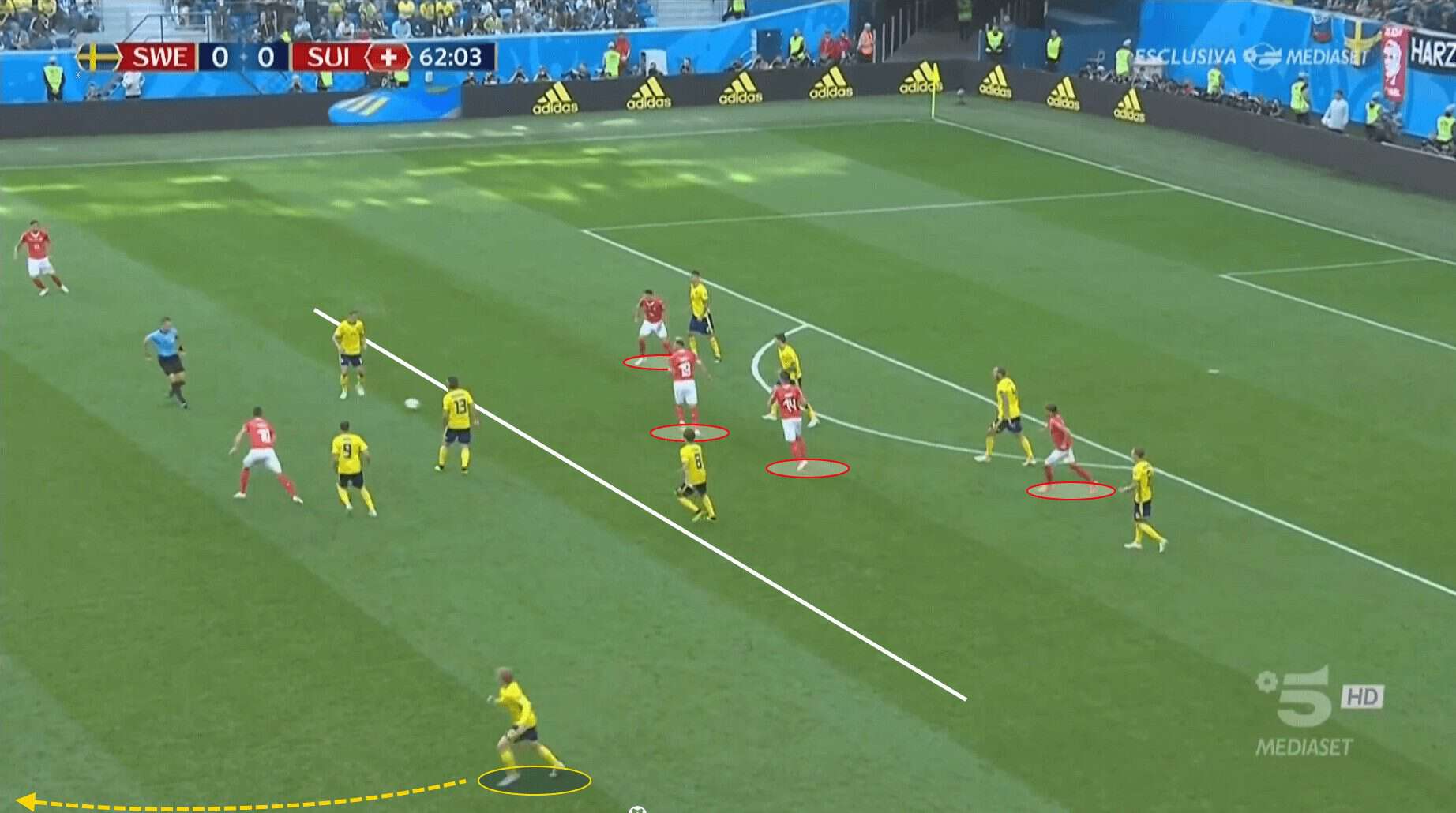

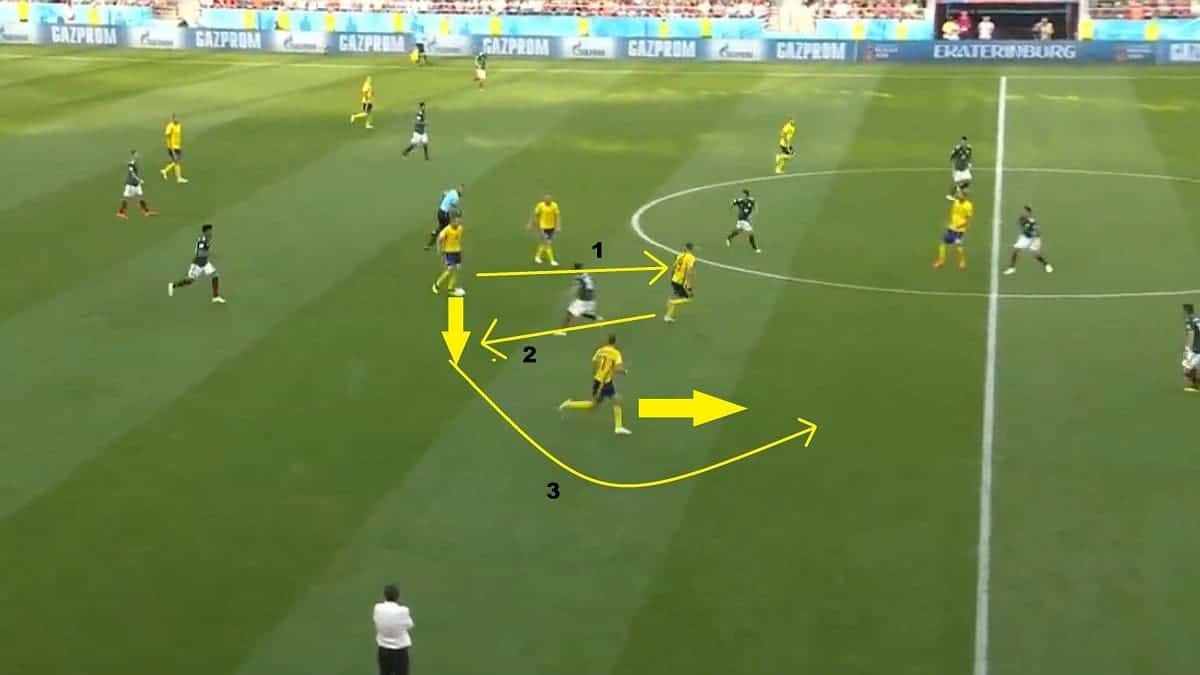

Below are a couple of examples of this approach in attacking transition. In both examples, taken from the wins over Switzerland and Mexico, Sweden use their compactness well. The strikers are used for wall passes by the central midfielders, helping them to play around the presser before playing into a slightly more advanced player in space to carry the counter-attack forward.

In the not-too-distant past England have encountered difficulties against organised defensive sides, but they were able to handle Sweden without too much discomfort. This was primarily because they neutered Sweden’s counter-attacking threat in a number of different ways.

ENGLAND’S TERRITORIAL DOMINANCE

With their back three and lone defensive midfielder, Gareth Southgate’s England had numerical superiority against the Swedish front two and could thus easily play around the first line of pressure. From there the outer centre-backs would pass to the wing-backs or look to exploit the movement between the lines of their attacking quadrant of Dele Alli, Jesse Lingard, Raheem Sterling and Harry Kane.

England adopted a patient approach in possession, generally looking to build gradually through the thirds and prioritising ball retention over risky passes. As Sweden were unable to successfully press the English back three they were forced deep. This, along with a lack of mobility up front, meant any counter-attacks they looked to launch often originated deep in their own half, a long way from goal.

Additionally, England’s centre-backs attentively marked the Swedish strikers. They were able to do this safe in the knowledge that if one centre-back went to mark or challenge one of their opposing frontmen, they had two other centre-backs to provide cover on the other Swedish striker.

While tough to beat in the air, Sweden’s front two of Marcus Berg and Ola Toivonen were highly effective in their combination play throughout the tournament. As a result, sitting off and simply allowing them to win the aerial ball was not an option, as this would give them time to lay off to a teammate and/or combine with one another. With one of Harry Maguire, John Stones and Kyle Walker marking the receiving striker, Sweden’s front two had less time to hold the ball up and continue the counter-attack.

The combination of sustained possession and an aggressive defensive trident meant that England naturally took up a high back line in transition. This often forced Sweden into counter-attacking through long balls over the top which were either: A) Easily swept up by England and used to recycle possession, or B) Led to offside decisions against Berg or Toivonen, who – as discussed – lacked the pace to break the line.

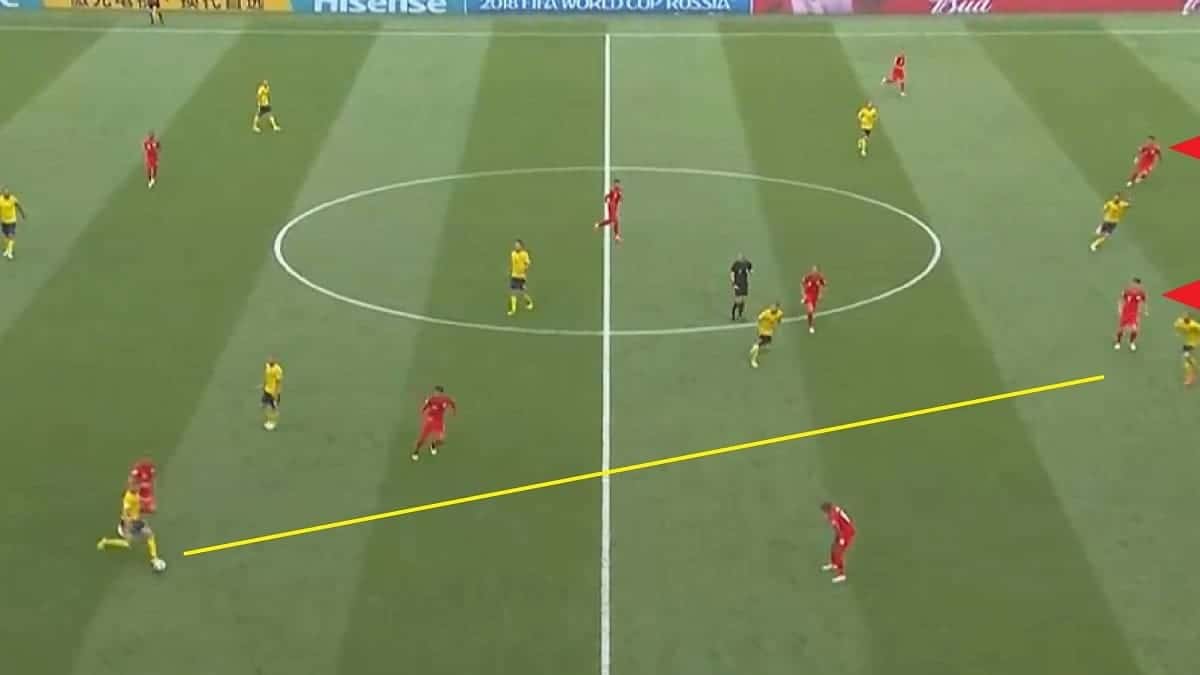

Below is an example of this aspect of England’s approach in defensive transition. Sweden regain possession and look to pass into their front two. Toivonen peels off the frontline to receive, so Maguire follows him closely to take away his time and space. Stones and Walker also push up to squeeze space, meaning Sweden’s only real option is to go in behind or over the top. They do this and aim for Berg, who manages to stay onside. However, he loses the race to the faster Walker, Sweden’s counter-attack peters out, and England take back control of possession.

ENGLAND AVOID CHAOTIC OR OPEN SITUATIONS

A small thing, but an important thing: England generally looked to avoid chaotic or open situations against Sweden. What does this mean? Well, despite having lots of possession in Sweden’s half, they regularly opted out of shooting or crossing unless the chance to do so was clear. This was done to limit the number of counter-attacking opportunities Sweden had and to continue England’s dominance of both possession and territory.

When forced back – which they regularly were – Sweden retreated into a low 4-4-2 block and looked to minimise the space available to England between the lines. This often meant that the dangerous areas – the penalty box and the famous ‘Zone 14’ just outside the box – were congested. Consequently, any shot was likely to be blocked, deflected, or forced wide of the target, and any cross was likely to be cleared away rather simply by one of the many Swedish defenders.

In short, long-range shots and hopeful crosses from wide areas were a pretty easy way for England to give up possession, and over-committing in and around the penalty box in the hope of forcing a goal was almost certain to leave them open in transition. Therefore, fully aware of the threat carried by the Swedes on the counter-attack, England regularly avoided crossing or shooting.

Below, England work a potential crossing opportunity. Walker has the time and space to look up and play the ball into the Swedish penalty area. However, recognising that anything other than an exceptional cross was likely to be caught by Robin Olsen or cleared by one of six defenders circled, Walker instead passed to Jordan Henderson, who in turn went back to Stones. England then looked to draw Sweden out of their low block and create more space behind to attack into whilst retaining control of the ball and taking away the possibility of a Swedish counter-attack.

ENGLAND’S COUNTER-PRESSING

As well as forcing Sweden to counter-attack from deep and limiting the number of counters available to them by prioritising ball retention over hopeful crosses or shots, England utilised intense counter-pressing, particularly in the first half, to cut off Swedish counter-attacks at source.

In defensive transitions, Southgate’s side looked to apply pressure to the ball-player and his nearby options with man-oriented counter-pressing immediately after losing the ball in Sweden’s half. This took away the time Sweden had to orchestrate their counters while also reducing the scope of possibilities open to them in these instances.

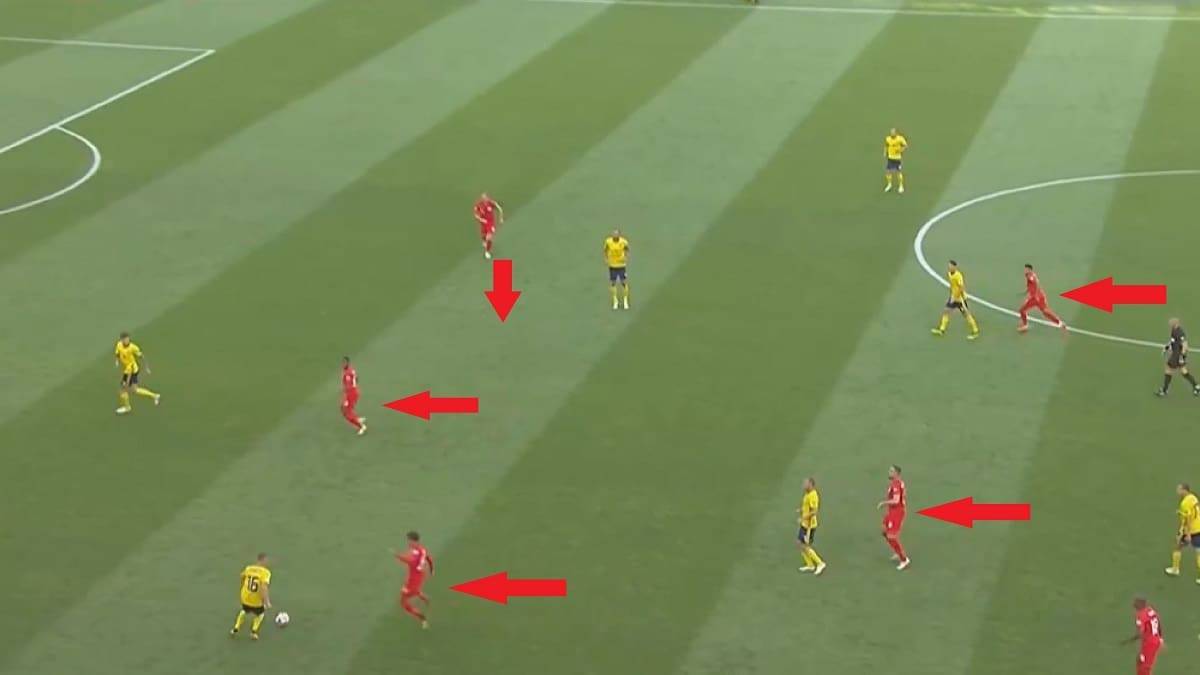

Below is an example of England’s intense man-oriented counter-pressing. Sweden regain possession down the right-hand side in their own half, and instantly Alli moves up and out to press the ball-player. Sterling moves up and Kane moves in to remove the centre-backs as comfortable passing options, while Henderson and Lingard cover the forward central passing options and Ashley Young supports near the touchline. While some passing lanes are open for the Sweden ball-player, each potential receiver is closely marked and has little time and space to control or turn.

CONCLUSION

Thanks to their identification and removal of a key threat in their opposition’s game, England secured an easy passage through to the World Cup semi-finals. For much of the match Sweden were simply unable to counter-attack cohesively, which at once reduced their own offensive opportunities and allowed England to regain possession and control. If you had to pick one summer showing to highlight the improvements made by the team under Southgate’s auspices, this would be it.

Check out our match analysis of the Sweden Vs England match along with analysis of England Vs Colombia and Croatia Vs England.

Comments