Landing the top spot in the Group B of FIFA World Cup 2018, Spain seemed to be one of the favourites to fall in the semi-final set of the tournament, something which is now just a fantasy for many. Four years back, Spain’s terrible performance against the Netherlands in the opening fixture of Brazil 2014 saw many expect their early exit from the group stage. But fast forward to Russia 2018 when we have a much more resilient team playing again with its ever-dominating tiki-taka and pulling it off in the opening match against Portugal, the result remained almost the same against even a weak Russian side. So what pushed La Roja down in the knockouts against the host team? Or broadly speaking, how did Spain fail under Fernando Hierro, who has played every card smartly despite being hired in emergency after the sacking of Spain’s former coach Julen Lopetegui?The new man in charge carried on the same 4-3-3 setup used by Lopetegui, with Diego Costa leading as the real nine contrary to Spain’s traditional reliance on false nine. From tiki-taka in deep regions to free flank runs down the right wing, Hierro was stuck with the already established Spanish style of play, which was decent enough indeed. But despite their revival after Brazil 2014 exit, Spain still lacked something that due to which their long stay in Russia 2018 couldn’t be foreseen. These missing elements were from both defensive as well as offensive points of view.

Defensive elements: The goalkeeper

When it came to saving the goals, Spain was clearly vulnerable. Dea Gea conceded 6 goals, excluding the penalty-shoot-outs, in the four matches. His performance in the shootouts against Russia set his new lows in the defensive records. The goalkeeper clearly lacks confidence and tends to lose concentration as the games progress. The opponents have had noticed that as they exploited him well. It could be possible that De Gea must have lost his concentration as he didn’t get to see much of the ball in his half as Spain was dominating possession against all of its opponents. But that’s not an excuse behind conceding 10 goals in the 4 games including shootouts, especially when one is competing in the biggest international football tournament.This also restrained Spain to attack freely without having to worry about the defence. De Gea’s poor goal-saving records in the group stage of Russia 2018 wasn’t even coinciding with Spain’s strategy to drag the game against the host to the shootouts in the knockouts. Hierro should have dealt with this weakness in Spain’s squad. Ideally, he should have restrained the central defenders to their defensive zone right in front of De Gea. Since the goalkeeper restrains himself to the goal line, Ramos and Pique could have watched out the gap in front of him which he doesn’t cover even when the ball is in Spain’s half. This might also cause Spain to pull their build-up back in their half and face pressing in the more dangerous region. But this is something they were not used to do. Least, Hierro could have replaced the goalkeeper with Reina at least for the decisive fixture against Russia.

Defensive elements: Lack of organisation

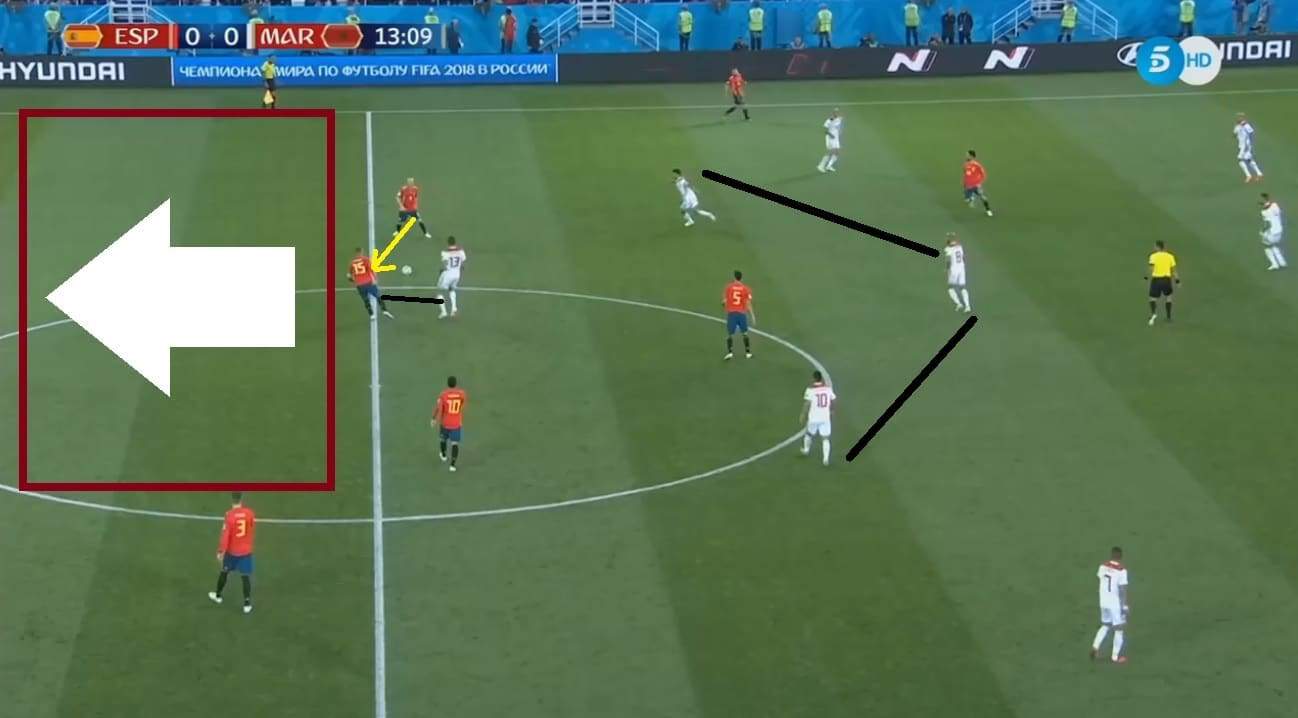

Other than the individual defensive issues of De Gea, Hierro couldn’t work on the issue of lack of Spain’s defensive organisation which becomes exploitable when the play restarts in Spain’s defensive half or Spain loses possession in its half.Almost all the goals conceded by Spain in FIFA World Cup 2018 were either from the set pieces or from Spain’s losing ball in their half. The first goal conceded from Morocco when Iniesta passed to Ramos while they were facing the press in such a dangerous area. Ramos got tackled and with such a large gap behind the Spanish defenders, the goal was expected.

The second goal conceded from Morocco’s corner is to be blamed on Morocco’s unmarked striker En-Nesyri having a minor gap in front of him to take a step and adjust his jump accordingly for the header.

On the other hand, against Portugal, Ronaldo’s goal was from the long ball played directly to Spain’s box. This could be also due to De Gea restraining to his region while the defenders not covering for the gap leaving a large exploitable gap behind them.Although Spain was able to defend the counters initiated from the opponents half during transitions, this was because in that case, the Spanish defence would also have to cover the same distance as of the opponents while chasing them up to their goal area. This gives them at least enough time to organise until one of them gets to the opponent with the ball to slow him down. Contrary to that, when the counters are initiated from Spain’s half, the defence is mostly unable to organise. Again this must be because Spain’s central defenders are used to rely on the goalkeeper to cover the large part of the outfield behind them. But with De Gea, this wasn’t going to be the case. And since Spanish defenders were clearly having organisation issues on shorter distance when chasing the opponents who recovered the ball in Spain’s half, it cost them many goals.What else could Hierro do to deal with this defensive weakness other than restraining the central defenders closer to the goalkeeper? He could have the respective fullback to come deeper forming a Back 3, or have the nearer CM drop back when the ball reaches to Spain’s first line of defence being pressed from the front. At the least, the ball could be passed forward as quickly as possible instead of playing slow backward or sideways passes in the build-ups. Hierro did deploy these changes in the knockouts fixture against Russia with Busquets dropping deep but it was of no use there as Russia hardly forepress Spain’s back-line. Instead, if Busquets had gone in an advanced region, this could have ensured the availability of more Spanish in the attacking third.Spain’s defensive organisation is not just linked to the defensive imbalance between De Gea and the central defenders but also to the situations when the play stops and is restarted by the opposition in Spain’s half. Against Morocco in the group stage of FIFA World Cup 2018, when Spain conceded a throw-in in their half in the last quarter, the opponent was not pressed from the front by Busquets which allowed him to dribble up into the pocket of space before throwing a pass to the open width to his teammate who found the width free from his throw-in spot. This is one of the many examples of Spain’s incoherent pressing structure to defend throw-ins and free kicks.

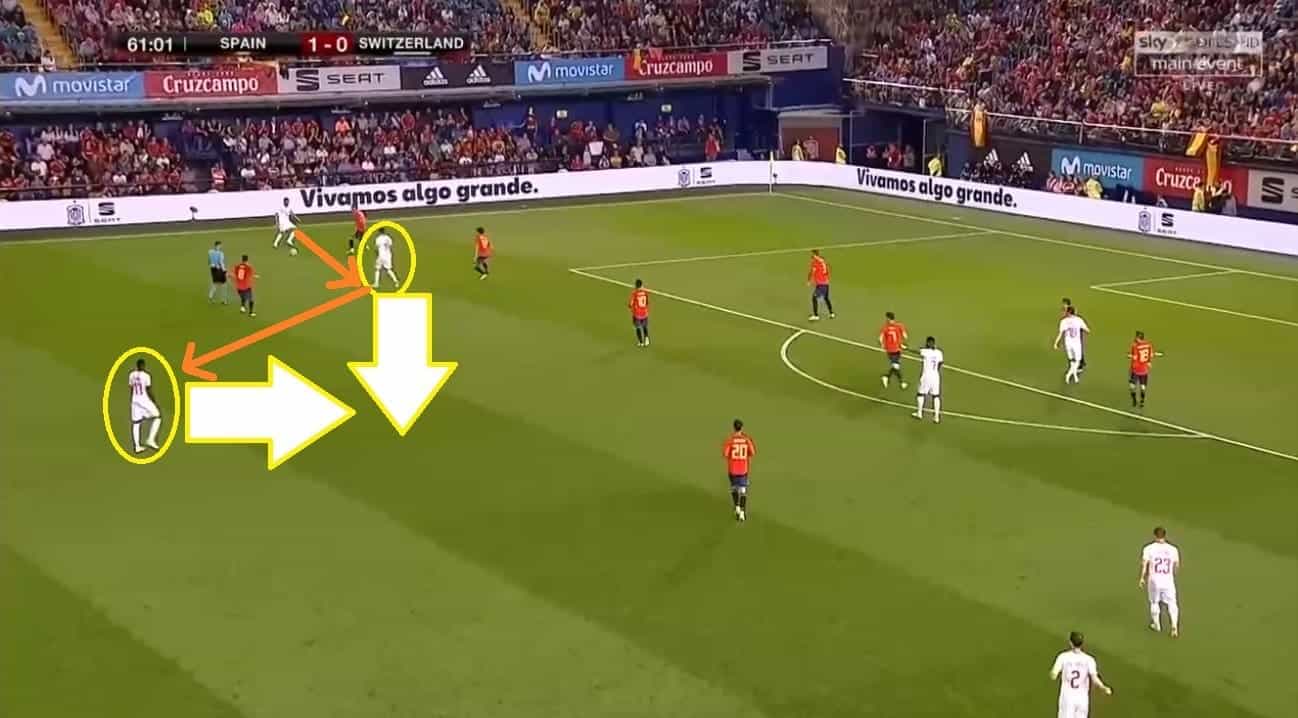

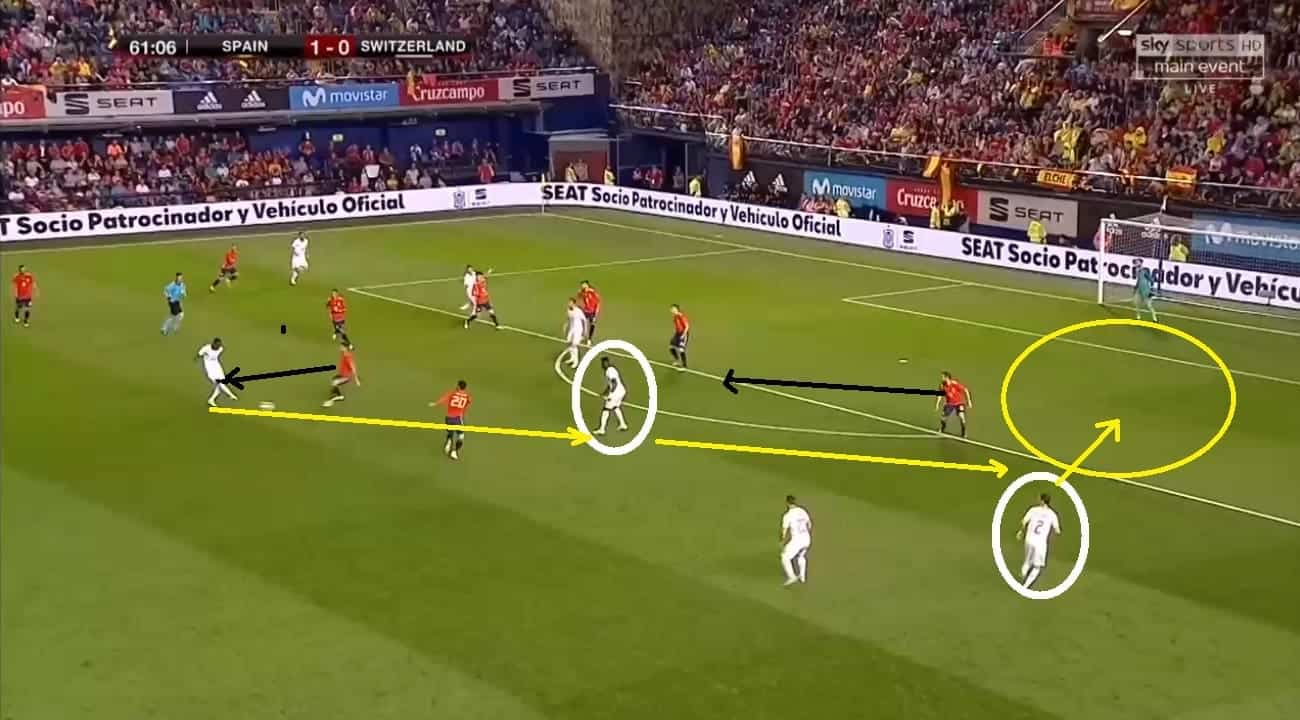

Even under Lopetegui, Spain conceded goals due to lack of defensive organisation. This all comes down to a single fact: Spain is the most vulnerable when the ball reaches their half and is not cleared or played forward at the earliest, either they are in defensive phase or the attacking phase. For instance, in Spain’s 1-1 draw against Switzerland in the International Friendlies, as the play restarted with Swiss in possession in Spain’s half, the later was not organised in their defence as the opponent receiving the pass had space to cut inside with another opponent unmarked (first picture below). Then to press this opponent, Saul came forward to attempt for a late and thus a failed tackle which unmarked his opponent behind him at a dangerous spot (second picture below). This made Alba leave his opponent to stop the potential attack but then the Swiss he left unmarked eventually scored.

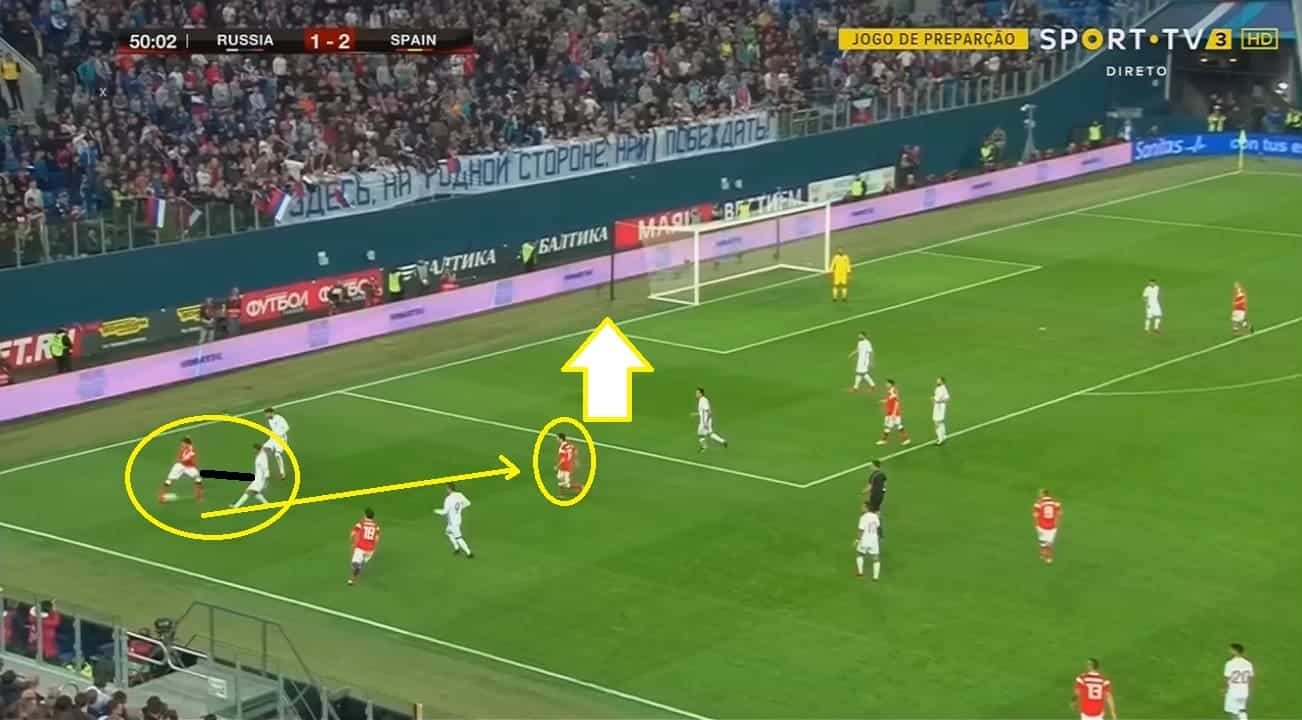

In another Friendly 3-3 draw against Russia, as the opponent won a throw-in in Spain’s defensive zone the later showed poor defensive organisation to cover the opponents’ route from the inside. Ramos attempted a late but failed tackle attempt which opened the space behind him for the opponent. This led to the opponents cutting into the box freely and creating a goal from the goal-line width.

These examples show how incoherent is Spain’s pressing structure in deeper areas of their defensive zone. They got exploited a number of times when they conceded throw-ins or fouls in their half because the opponents were able to thread-pass the defence to the inside. Given the likelihood of Spanish defenders to make errors at both individual and collective fronts, the only way for them to be organised was to just further close down their press structure from the inside and the front – the dangerous areas. There is no point of pressing when the opponent is not being closed down from the dangerous sides.

Offensive elements: Ignoring open players outside tiki-taka structure

Spain was one of the best-attacking powers among the qualified Russia 2018 teams. Their tiki-taka defines their passing play and attacks in the deep areas of the final third. However, their play often gets too directed towards their tiki-taka structure, that the players at the open area outside the structure remain underutilised. While the low block defences provide enough compactness to block the final of their tiki-taka, concluding their attack via an open player, outside the ongoing passing flow, works in such situations. In the group stage fixture against Portugal, Nacho’s goal is an example who scored just outside the box, not being part of the ongoing passing play, as the ball deflected off the opponent to the empty space there.

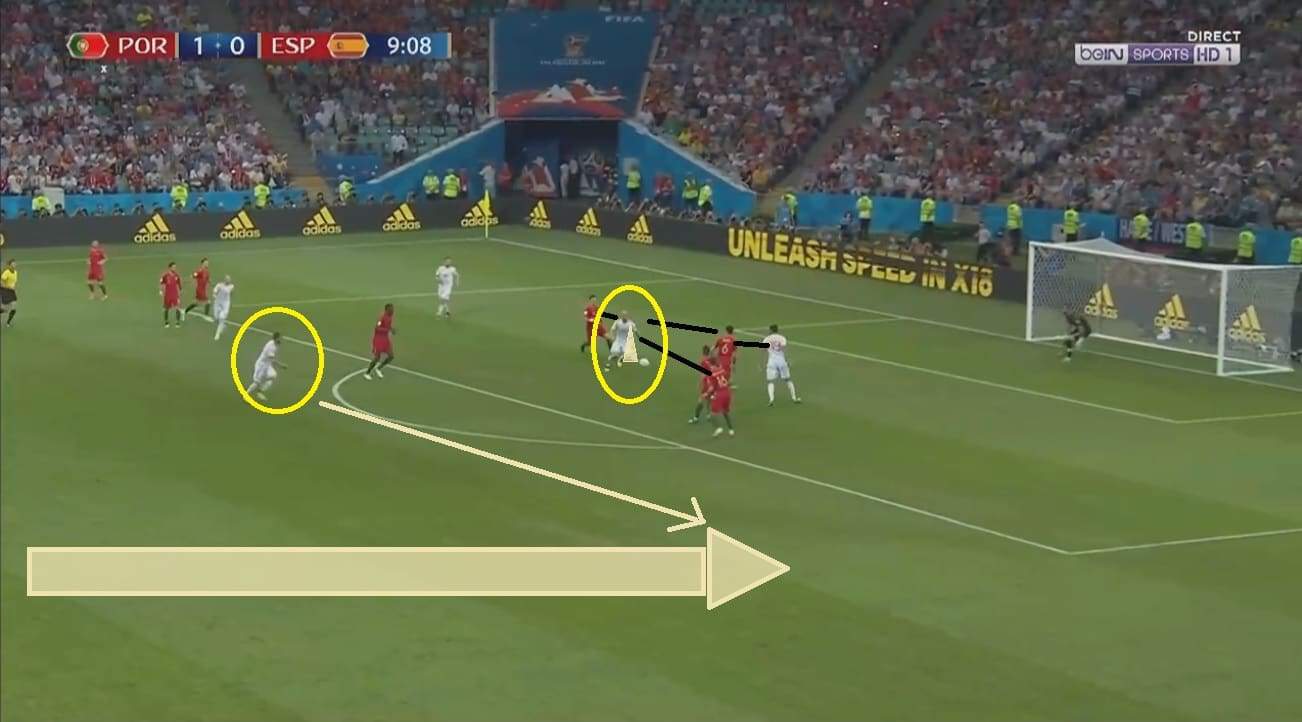

In another example against Portugal before Nacho’s goal, however, the attack which was supposed to conclude to Costa couldn’t as he was isolated. The ball should have been passed to Koke open outside the box by Silva from inside the box who instead shot way off the target being in a non-optimal body position. The ball could also be shot back by Nacho as the fullback would run up to the free space. But both Nacho and Koke remained underutilised due to not being part of the passing play at that point in time. Besides, Nacho should also have been a little more advanced but he is more into defence than attack.

Then against Morocco, Iniesta remained underutilised at one point of time when the passing play was being executed at the left width. Thiago’s pass to Alba intercepted by the opponent. Instead, it could have been played high to Iniesta open near the box at either side (he wasn’t offside) or in a quick Thiago-Busquet-Iniesta tri-passing.

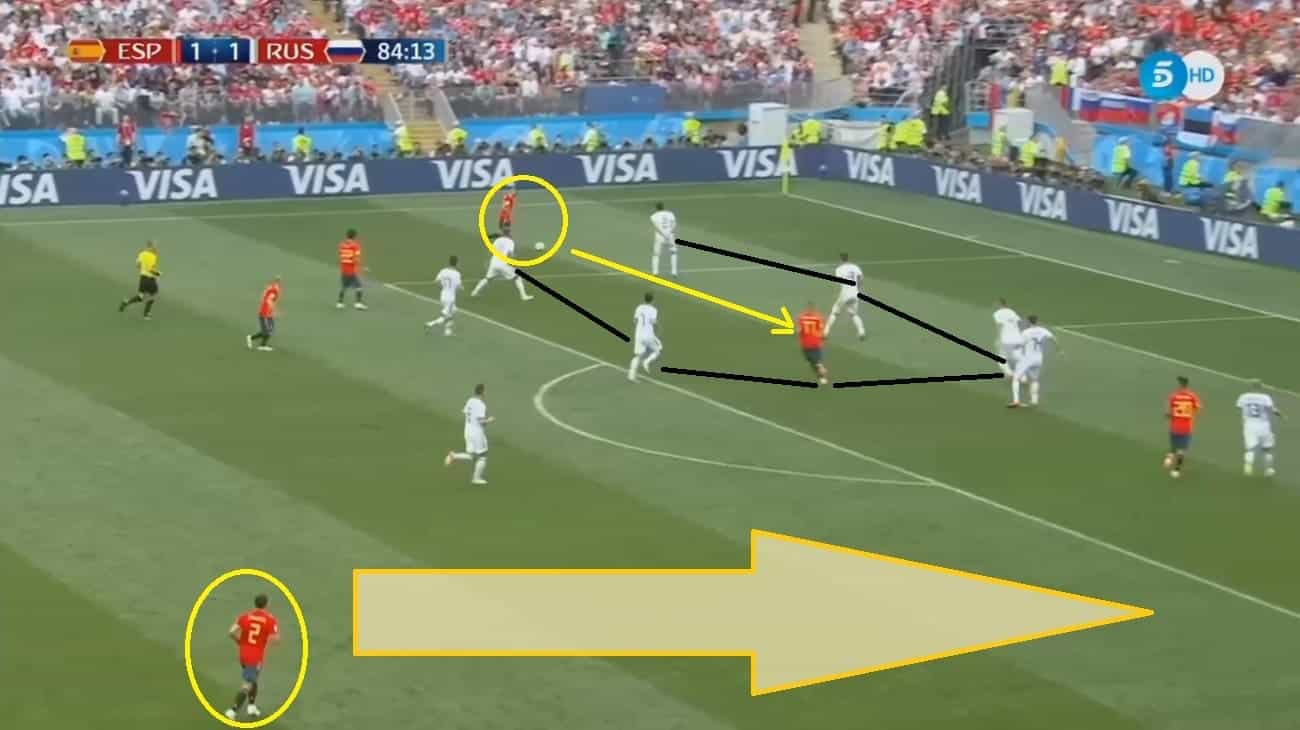

Against Russia, Carvajal remained unused at one stage being outside the passing play at that point of time. The ball was instead played to Silva to conclude the attack but he couldn’t, given the deep pressing by the Russians. So he passed to Iniesta whom he was facing but the later shot was slow enough to be saved. If Carvajal had got the ball (picture below), he would have attacked down his open plane and would have shifted the tactical dynamics of the passing play.

Thus, Spain’s tiki-taka has the tendency to often ignore the potentially dangerous players in open space outside the passing structure at that point in time. Sometimes this allows opponents to break the structure as it can be easy to read and breach a focused passing play at a single vertical plane. By utilising those open players Spain could be more threatening in attack than it was. It was all a matter of long passing outside the passing structure which could be deployed tactically had these open players been utilised.

Offensive elements: Formation changes against Russia

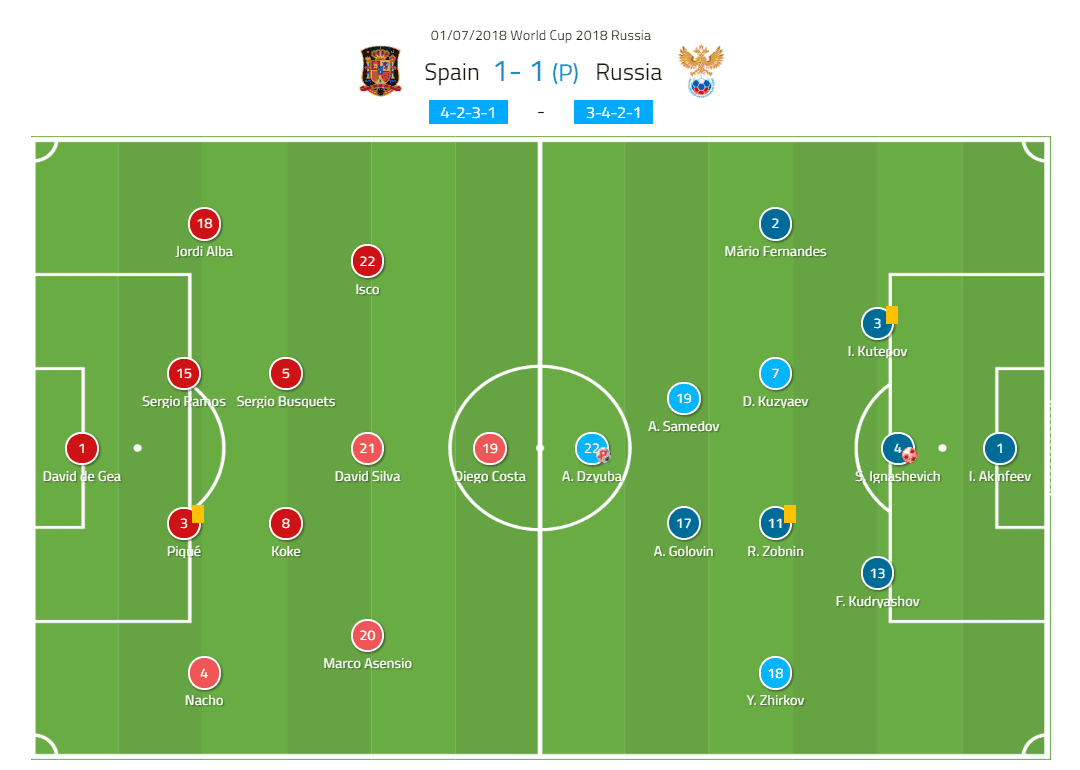

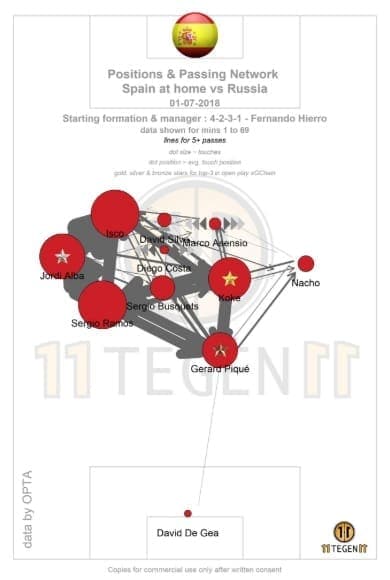

One major element which led to Spain’s knockout from FIFA World Cup 2018, is their unusual placement of players against Russia comparing to the one in group stages. Hierro had Spain play with 4-2-3-1 set up which wasn’t bad in itself but what’s disturbing was not placing Iniesta in the central position and then placing Silva in the centre, right before Costa.

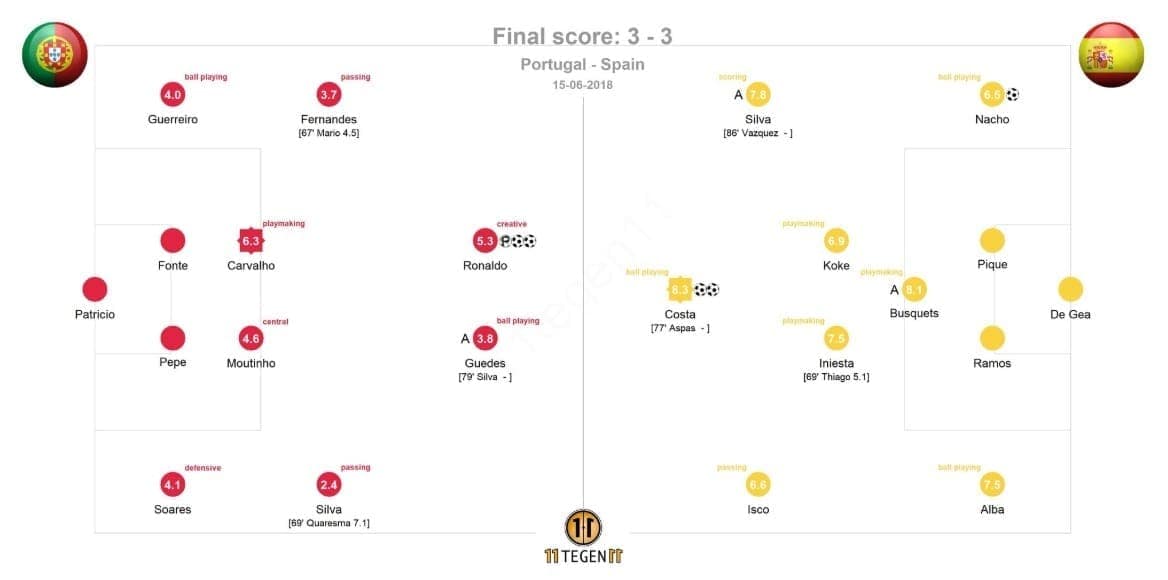

As discussed above, placing Busquets just in front of the central defence led the midfielder to drop back thus contributing further to Spain’s conservative game. On top of that, with no Iniesta, there was no one to keep the game flowing and threading behind the defence. Iniesta’s dribbles to the deeper and central regions while looking for pockets of spaces can open up the press structure. Besides, Isco was only usable attacking element – as Silva and Costa were often isolated – who dropped into spaces but he needed Iniesta to cut across the flank and spaces to make way into the box.Third, Silva, who could have cut into the box from his current favourite position in the half-space, was instead placed in the centre behind Costa with often no space to cut dribble or run into the box. This loosened Spain’s tiki-taka structure. Next, placing Koke instead of Thiago in the midfield cost Spain unable to deliver the kind of attacking game they were in need to. The passing map of Spain below (developed by @11tegen11) also shows that its play was mostly restrained to conservative passing with lack of coherence at a particular plane. Costa and Silva are lying at the same vertical plane uncoordinated while the high density of passes around Ramos says a lot about Spain’s conservative approach.

Finally, all these inconsistencies in the formation kept Costa disconnected who already had to be isolated and overmanned given Russia’s switch to low block defence in that fixture. Anyway, the Real 9s are almost always get isolated in such a defence except if the defence can be deep breached as happened against Iran but to do that Iniesta was missing for a good part of the game. Hence Costa being unable to connect to Spain’s passing plays remained good for nothing behind the defence. The passing map of Spain above displays the same and that the attacks are mostly not concluding anywhere as Costa and Silva remain disconnected from the passing play.There were very few long balls played by Spain due to the fear of ceding possession as there weren’t any Spanish behind the Russian defence except Costa. Although Costa is more of a natural carrier of a long and direct play than of tiki-taka, his presence was required to deal with the multiple pressing which Spain was very likely to face in Russia 2018, which they did. However, his inability to drop into the passing structures, or into the regions opening due to tiki-taka, was something inconsistent with Spanish style. By the time Spain reached to the knockouts, the opponents had already planned on how to close the striker down. Hence against Russia, Costa should be used tactically rather than the target man who would conclude the attack. Placing of Aspas or Silva at the right attacking wing could get the better out of Costa.

Conclusion

Spain couldn’t harness their best aspects against Russia, which they did against Portugal thus allowing them to cover up their vulnerabilities. Despite having around five clear opportunities in their last fixture of FIFA World Cup 2018, they couldn’t conclude their attacks except for that own goal. Their inability to shift the tactical dynamics of the game outside the tiki-taka is one weakness at the offensive front. Then the wrong placement of Silva and Busquets and the absence of Iniesta in the starting lineup further restrained the team’s forward game causing them to get stuck in front of the Russian defence. La Roja’s defensive organisation is another alarming element which made them vulnerable at times in Russia 2018. In fact, had Spain dealt with their defensive insecurities, they would be able to make it to the quarterfinals. Poor defence ultimately overpowers good offence and vice versa.

Comments