Few expected 2018 World Cup hosts Russia to make it out of the group stage of their own tournament, so when they were drawn against Group B winners Spain most predicted a Spanish victory. However, Stanislav Cherchesov’s side pulled off one of the greatest upsets in a surprise-filled competition, earning a 1-1 draw before winning on penalties to seal a place in the quarter-finals.

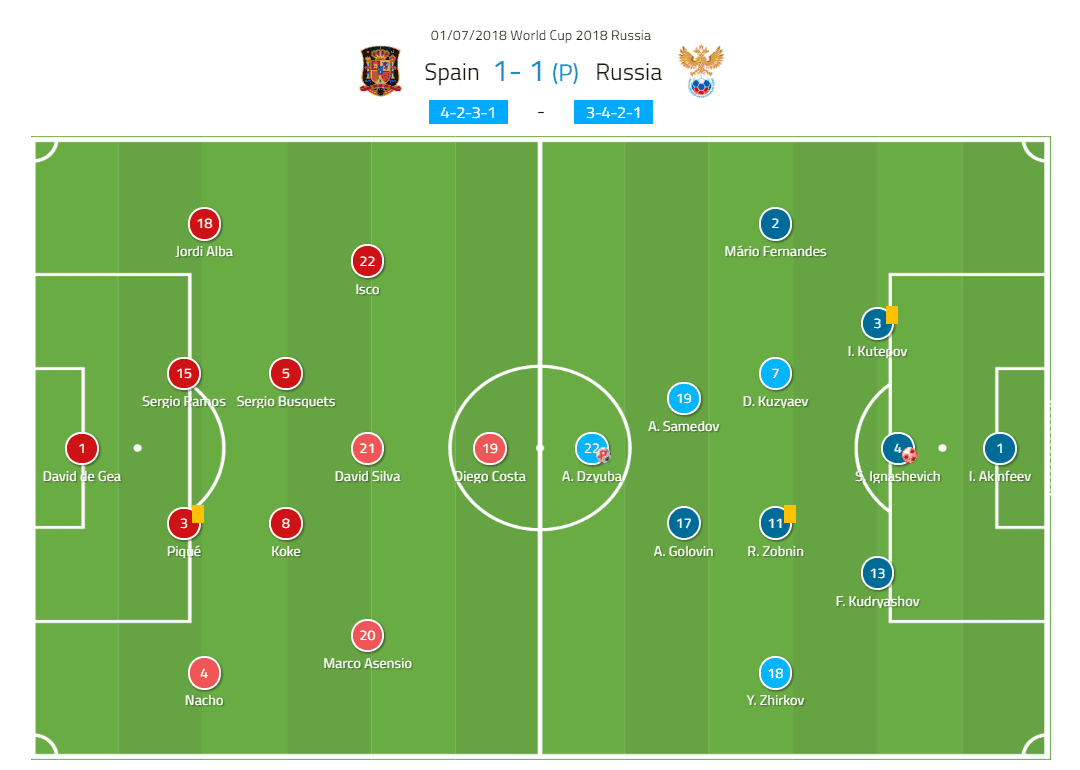

LINE-UPS

Fernando Hierro lined his Spain side up in a 4-2-3-1 system, with Sergio Busquets joined by Koke at the base of midfield. The decision to pick Koke over Thiago Alcantara was one sign of a more conservative approach, the other being Nacho starting at right-back over the more attack-minded Dani Carvajal.

Isco was given his customary free role, though he more often found himself on the left-hand side. Marco Asensio stuck to the right wing, while David Silva acted as the No.10. Diego Costa was once again chosen to lead the line.

Russia decided to change system for this particular match, moving away from the 4-4-1-1 that had served them well in the group stage and deploying a 5-4-1 shape. Artem Dzyuba was the lone striker, while Aleksandr Golovin slotted in on the left wing. Denis Cheryshev, who enjoyed such a positive first round, was dropped to the bench.

Cherchesov went with a back three of Ilya Kutepov, Sergei Ignashevich and Fyodor Kudryashov, while Mario Fernandes and Yuri Zhirkov were the wing-backs. In central midfield, Yury Gazinsky made way for Daler Kuzyayev alongside the indefatigable Roman Zobnin.

RUSSIA’S LOW BLOCK

Aware of the threat associated with leaving space for Spain to attack in, Russia opted to defend in a low 5-4-1 block. Both wing-backs dropped to form a five-man back line, both wingers tucked in to form a four-man midfield line, and Dzyuba dropped back into his own half. All of this meant that Russia often had every single outfielder behind the ball, helping to ensure vertical compactness.

Horizontal compactness was maintained by a position-orientated defensive approach that saw the defence and midfield lines shift from side to side, congesting the centre before providing cover for the ball-near winger and wing-back, who would both move up to press when Spain’s possession went wide. An example of the horizontal compactness in Russia’s midfield line is seen below.

The compactness of Russia’s defensive setup made it difficult for Spain to play through them. Often there were no obvious gaps to exploit, and even if a gap did appear, the aforementioned compactness of Russia’s shape meant it would not take long for them to get men around the ball, suffocating the receiver by pressing from all angles.

Russia didn’t apply pressure to Spain’s first line of build-up, allowing Sergio Ramos and Gerard Pique to have as much time as they wanted on the ball. By effectively blocking the centre they forced their opposition wide, where they would press in a man-orientated fashion with the nearest wing-back, winger, and central midfielder. Another trigger for pressing was the Spanish ball-receiver having his back to goal. In these situations, one of Russia’s central midfielders would step up to pressure his opposing man from behind, looking to force a backwards or sideways pass.

If Spain were forced to pass back, Russia were organised when stepping up collectively, pressing the ball-player as well as his immediate passing options to continue forcing their opposition backwards and, eventually, into a long ball forwards that they could comfortably clear or use to regain possession.

RUSSIA OCCUPY SPAIN’S FAVOURITE SPACES (AND BUSQUETS)

One of the recurring themes of Spain’s attacking play in the group stage was their occupation of the half-spaces. This was particularly evident in their thrilling 3-3 draw with Portugal, where the left half-space was overloaded by Andres Iniesta, Isco and others to combine and progress possession.

Attacking in the half-spaces can cause problems for opponents. Firstly, due to possession not being on the wing or in the centre, the opponent’s wide and central players can both be provoked to create space further forward. This is particularly problematic if the opponent lines up with a back and/or midfield four – should, for instance. Secondly, players occupying the half-spaces have access to both the centre and the wing. With multiple options as to where they can pass or dribble, it can be tougher to shut them down.

Russia, however, denied these spaces to Spain not only through their choice of system, but through their defensive movements. Their 5-4-1 shape meant that when Spain looked to combine through the half-spaces, they were faced with at least three defenders – the nearest Russian wing-back, central midfielder, and winger. An example of this is seen below.

Furthermore, when Spain moved the ball wide with the intention of then passing back into the half-spaces for an attacking midfielder to carry the ball forward, they were denied by Russia’s low block. As discussed earlier, Russia shifted intensely from side to side to deny space at every opportunity and, when the wingers and wing-backs moved out to press, they were supported by a line of cover behind them. This meant the Spanish full-backs and attacking midfielders could not simply play diagonal passes into the centre to bypass the pressure they faced.

While their defensive approach was mostly zonal, Russia did employ some man-marking, with Dzyuba tasked with tracking Sergio Busquets. Spain’s primary deep-lying playmaker rarely found himself in space, which only made it more difficult for his team to play through the centre. Russia’s commitment to man-marking Busquets never wavered – Dzyuba’s replacement, Fyodor Smolov, continued with the task even into extra time.

SPAIN PLAY IN FRONT OF RUSSIA

While much of the credit for Spain’s inability to penetrate Russia for much of this second round clash must go to the hosts’ organised low block, compactness and pressing, there must also be some blame apportioned to Hierro and his players. They were far too cautious for far too long, meaning their almost constant possession of the ball resulted in very little by way of serious scoring chances.

Hierro’s conservative selection was strange, especially considering the lack of pressure they faced when building up. With Busquets man-marked, Koke often dropped deep to receive from Ramos or Pique. This meant Spain had three players to start attacks, none of whom faced any concerted pressure – remember, Russia’s first line of defence was Dzyuba, and he was marking Busquets. Essentially, Spain often had a completely unnecessary 3v0 situation when building possession from the back. A more effective option here would have been to pick another attacking midfielder, instead of Koke, to play between the lines of Russia’s defence.

But the selection of Koke was only one issue – Spain’s attacking midfielders also dropped too deep too often. This led to situations like the one seen below, where just one player – Diego Costa – is actually operating behind Russia’s midfield line. Isco is threatening to move behind, but doesn’t; Asensio is wide on the right; and Silva has, for no apparent reason, dropped back onto the same line as two other Spanish players, both of whom are unmarked. With this attacking structure, it was virtually impossible for Spain to open up Russia’s low block.

Again, Russia made it difficult by congesting the space available between their lines of defence. This perhaps discouraged Isco and Silva, leading to them both moving out of pressure zones to find space where they could get on the ball. In this case, bravery was what Spain lacked, and it led to a lot of sideways and backwards passing.

Generally, they circulated the ball from wing to wing via the full-backs, centre-backs and central midfielders, with one of the attacking midfielders drifting wide to receive possession. Once again, however, they were playing in front of Russia’s defensive block, allowing the hosts to simply shift from side to side as a unit to continue blocking space and forcing Spain wide and back.

Spain’s possession lacked variety and speed, but it was a poor structure that cost them most dearly. One example of this is seen below, where Isco wanders wide to the right to receive the ball from Pique. However, Nacho is in almost the exact same position, so Isco’s movement was totally unnecessary. Instead of blocking the pass to Nacho, Isco could have moved into the highlighted grey area between Russia’s defence and midfield, offering a line-breaking pass. By not doing this, Isco is once again operating in front of Russia’s block, making him easy to spot and defend against.

With sterile possession, Spain’s best hope of creating came in defensive transition, where they used intense man-orientated counter-pressing to try and win the ball back immediately after losing it, in high areas of the pitch, while Russia were not yet organised. An example of this is seen below.

CONCLUSION

Spain obtained a remarkable 79 per cent of possession against Russia, but were unable to break their opponents down from open play – their only goal came from a free kick which deflected in off of Ignashevich. Russia played simply to see the game out before winning on penalties.

This match could be seen as a one-off disaster for a Spain side without the manager that led them to the tournament, Julen Lopetegui. However, it could also be seen as the final nail in the coffin of Tiki-Taka, the possession style that they have generally been wedded to for the last decade. For them, Euro 2020 could well be a watershed tactical event. As for Russia, their dream continues with a quarter-final against Croatia.

Comments