Argentina dominated, from the physical and mental sphere, an absolutely tough game that allowed them, after extra-time and a penalty shootout where again, Emiliano ‘Dibu’ Martínez was the hero, to be among the four best in the 2022 World Cup. With a hard and aggressive block that neutralised the creative options of the Netherlands and Lionel Messi at the highest level that he has shown in the national team, Lionel Scaloni said Martínez and Messi themselves, showed the necessary passion and mental intelligence to play in this instance of this tournament.

For their part, the Netherlands, after a rather bizarre week in terms of Louis Van Gaal’s quotes and the responses from the Argentine side, with a more pragmatic idea that changed during the 2022 World Cup matches, have been eliminated from the competition. after being one of the candidates to take the trophy. The quality of talents like Virgil Van Dijk, Jurrien Timber, Frenkie de Jong or Cody Gakpo, was not enough in a match where they were greatly outmatched, especially on the physical aspect of the game.

In this tactical analysis, we’re going to review the tactics of the game, in form of an analysis, of how Lionel Scaloni’s Argentina beat the Netherlands on penalties to get through the semi-finals.

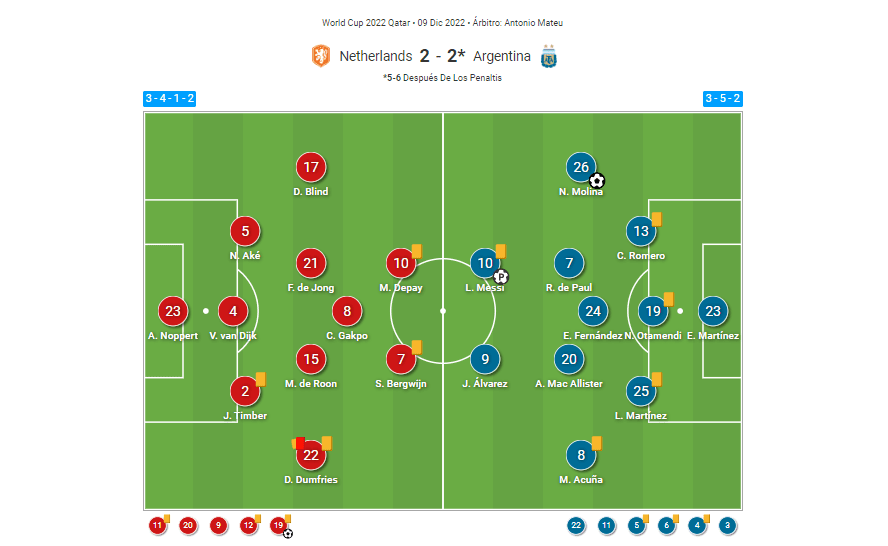

Lineups

Argentina changed their shape to a 3-5-2 with Emiliano Martínez on goal, Cristián Romero, Nicolás Otamendi and Lisandro Martínez as centre-backs, with Nahuel Molina over the right and Marcos Acuña on the left as their wing-backs. Through the middle, once again the presence of Enzo Fernández, Rodrigo de Paul and Alexis MacAllister, concluding the starting eleven with Lionel Messi and Julián Álvarez.

The Netherlands as well went with a back-five, which they have been using since the start of the tournament. Andries Noppert was again the goalkeeper. Jurrien Timber, Virgil Van Dijk, Nathan Aké, Daley Blind and Denzel Dumfries remained untouchable. The midfield was composed of Marten de Roon, Frenkie de Jong and Cody Gakpo, with an attack made of Steven Bergwjin and Memphis Depay.

The width from Acuña/Molina and the intensity of their defensive approach

Argentina, despite changing their ideas and principles with the ball a bit since the start of the World Cup against Saudi Arabia, is a more positional team, than approaching all the players to the ball, in a game much more based on the function of the ball, instead of occupying spaces, has generated criticism and multiple comments from all over the world, many asking for it to be played in another way, the first one showed in the qualifiers, but the reality is that seeking width has worked for Lionel Scaloni’s men.

And that was exactly what he was looking for in the quarterfinals against the Netherlands, a team that was more than solid defensively as they had shown with their back-five that switched between back-three and back-four many times during the match. But with the long runs of the wing-backs, Scaloni detected weaknesses in these channels so that he could also deploy a back-three, which would not only allow him to offer more width with wing-backs but also generate a 3v2 against the first line of pressure from Van Gaal’s team. Subsequently, the positioning and role of Nahuel Molina on the right and Marcos Acuña on the left were extremely important, beyond the fact that the former scored 1-0.

But what is also expected is that it was an extremely physical game, as it was in the first stages of the game, until the last of extra time. The historical context of the match, the previous comments from both sides, and the aggressiveness with which many are going to play an instance like this, in a tournament as privileged as this one.

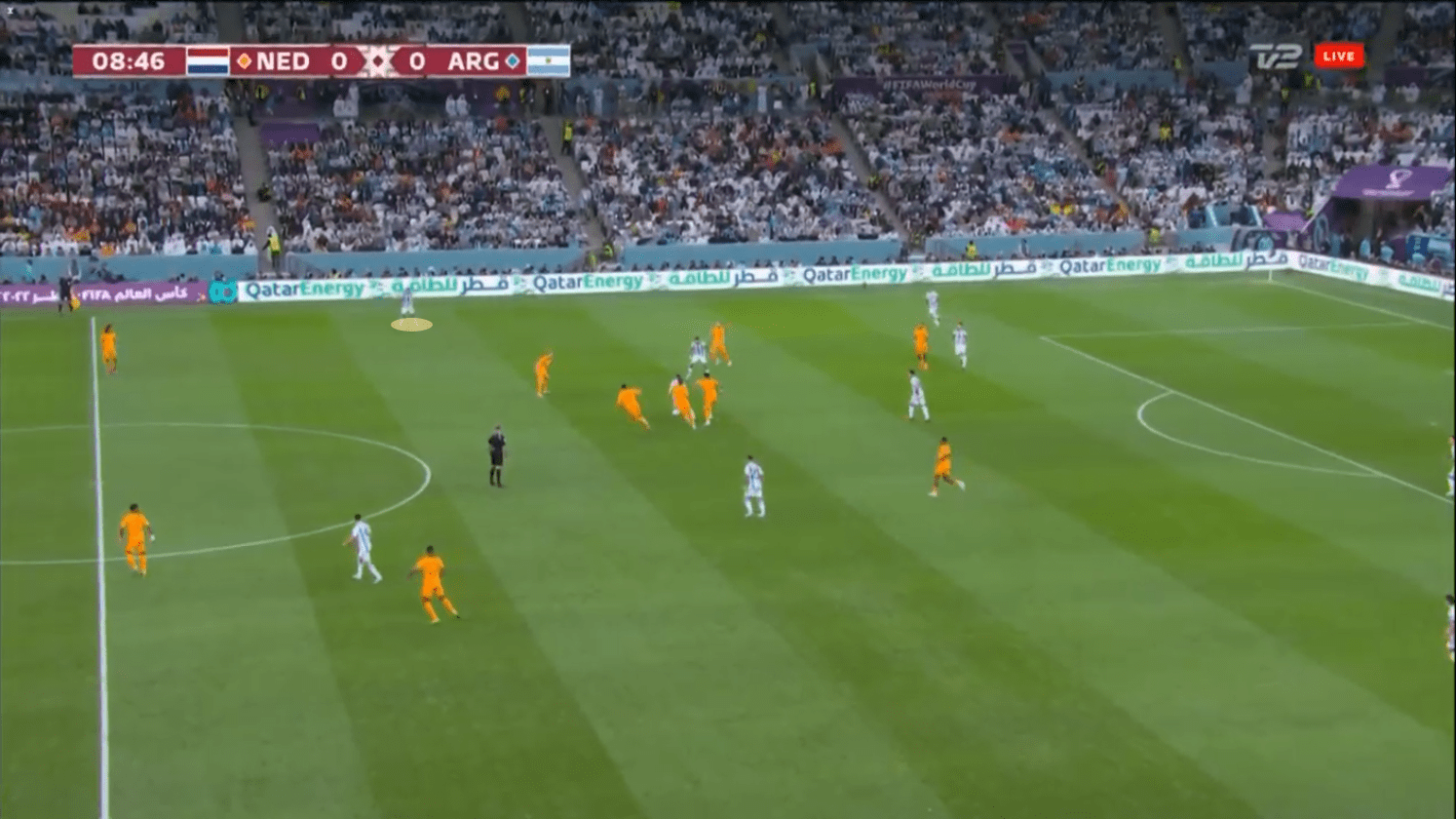

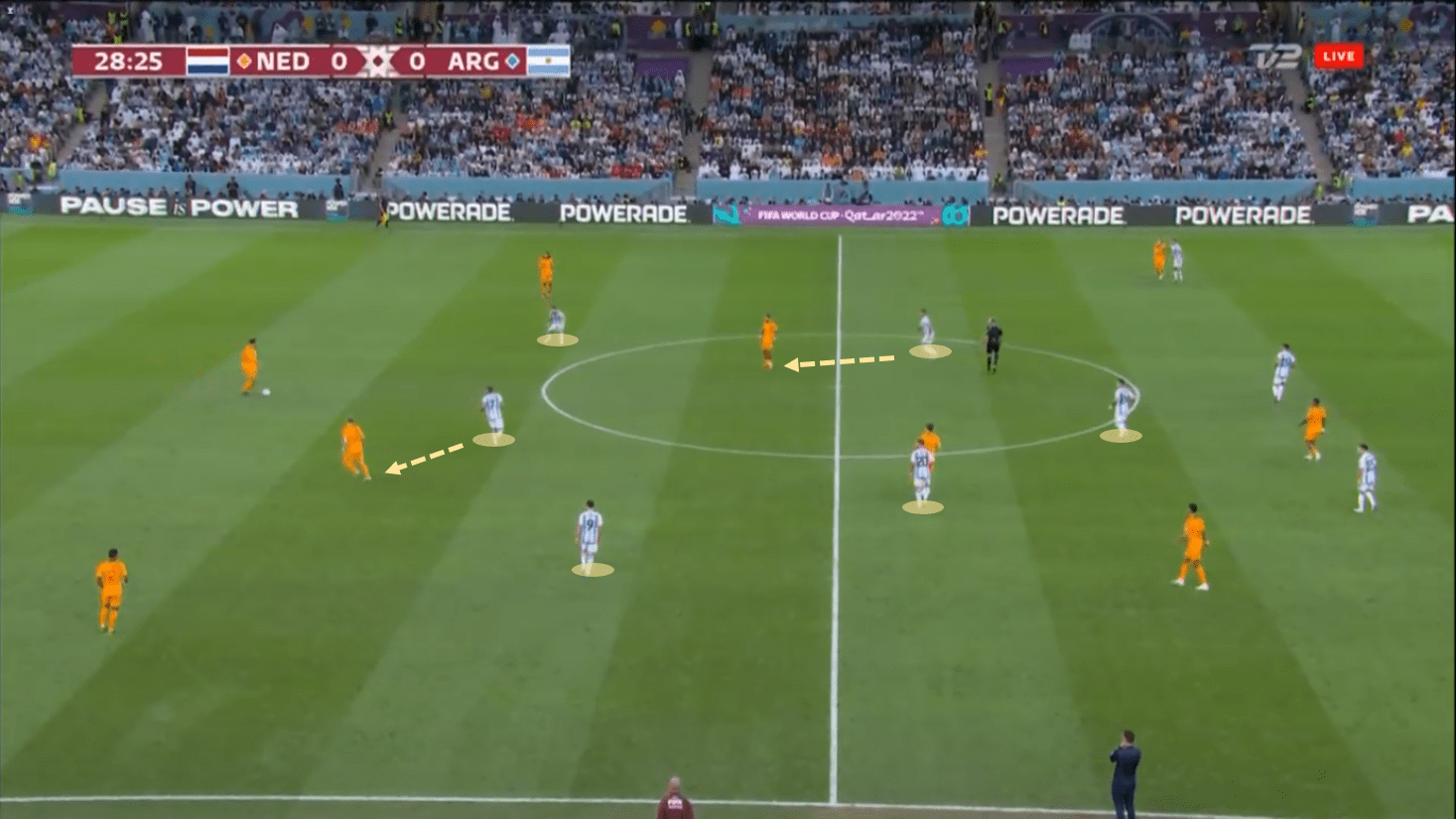

With the ball, Argentina sought to create plays in a very mobile 3-5-2 formation that accumulated too many people through the middle, with Rodrigo De Paul, Enzo Fernández, Alexis MacAllister and Lionel Messi’s relegations that were constant in many stages of the match, not only to avoid the pressure but also so that with his attraction of so many players, his teammates would be quite free with space and time to control and run.

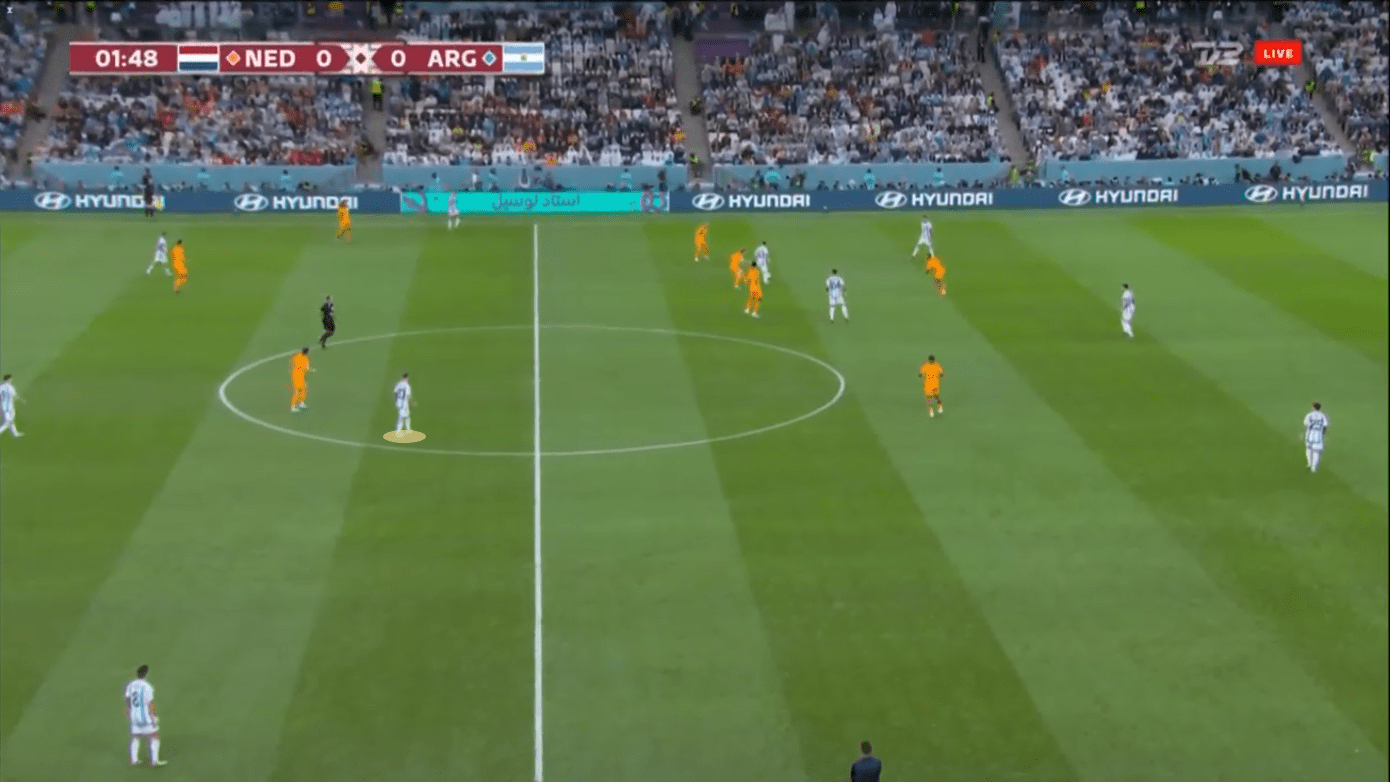

Just reaching the second minute of the game, this seriousness of Lionel Messi began to take effect. Argentina seeks to generate a lot of play in the half-spaces and central channels, because they have players with great ball control and passing ability, and decisive in small spaces to play there, attract and then fully open the ball to the band with a winger or in this chaos, they were wing-backs. The first sign was seen. Messi attracts up to three players behind him, and one in front. He has moved the entire Dutch block to one side with Alexis MacAlister behind.

But if there is something that characterizes Messi, it is that he will never do things in a hurry. Despite being one of the most agile and fastest players when he has the ball, which offers frenzy with his changes of pace and direction, his intelligence to know when to release and thus move the opponent better so that his teammate later appears free at the right moment, it’s fascinating and it is one of the reasons why he is the best player of this era.

He decided to wait and put up with the marking, thus releasing the pass to Tottenham Hotspur‘s Cristián Romero, who waited for Messi to move forward further, moving the lines more and this opened up more spaces for the first receptions of his teammates on the inside, with plenty of room to think.

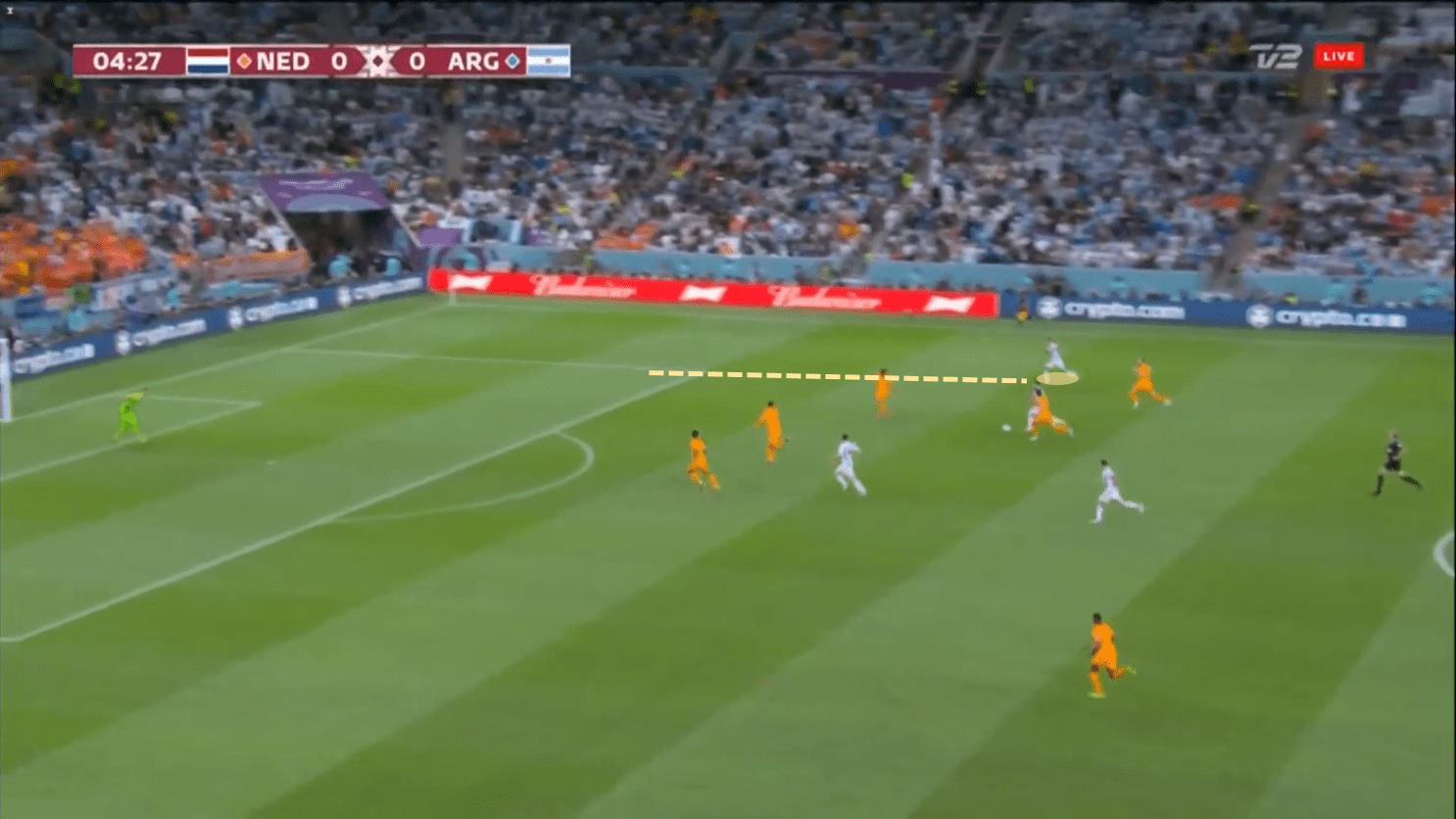

When we talk about Argentina’s first goal, we know that the talk focuses on the incredible and non-existent pass that Lionel Messi invented, after cutting in and moving the ball a little before making the pass between the lines for Nahuel Molina. However, little is said about how important the right wing-back’s movements were, both in transition and in a more organised attack.

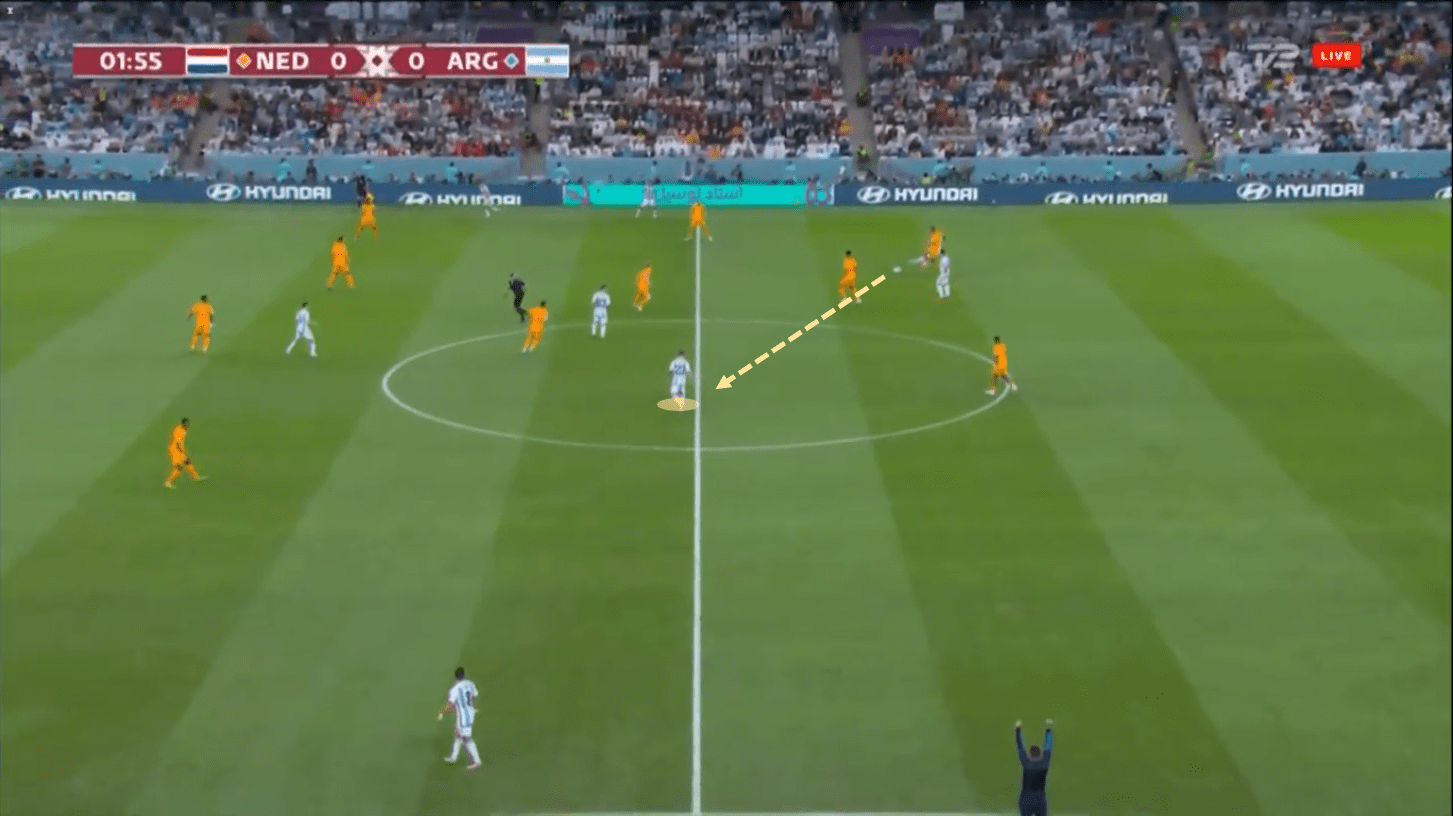

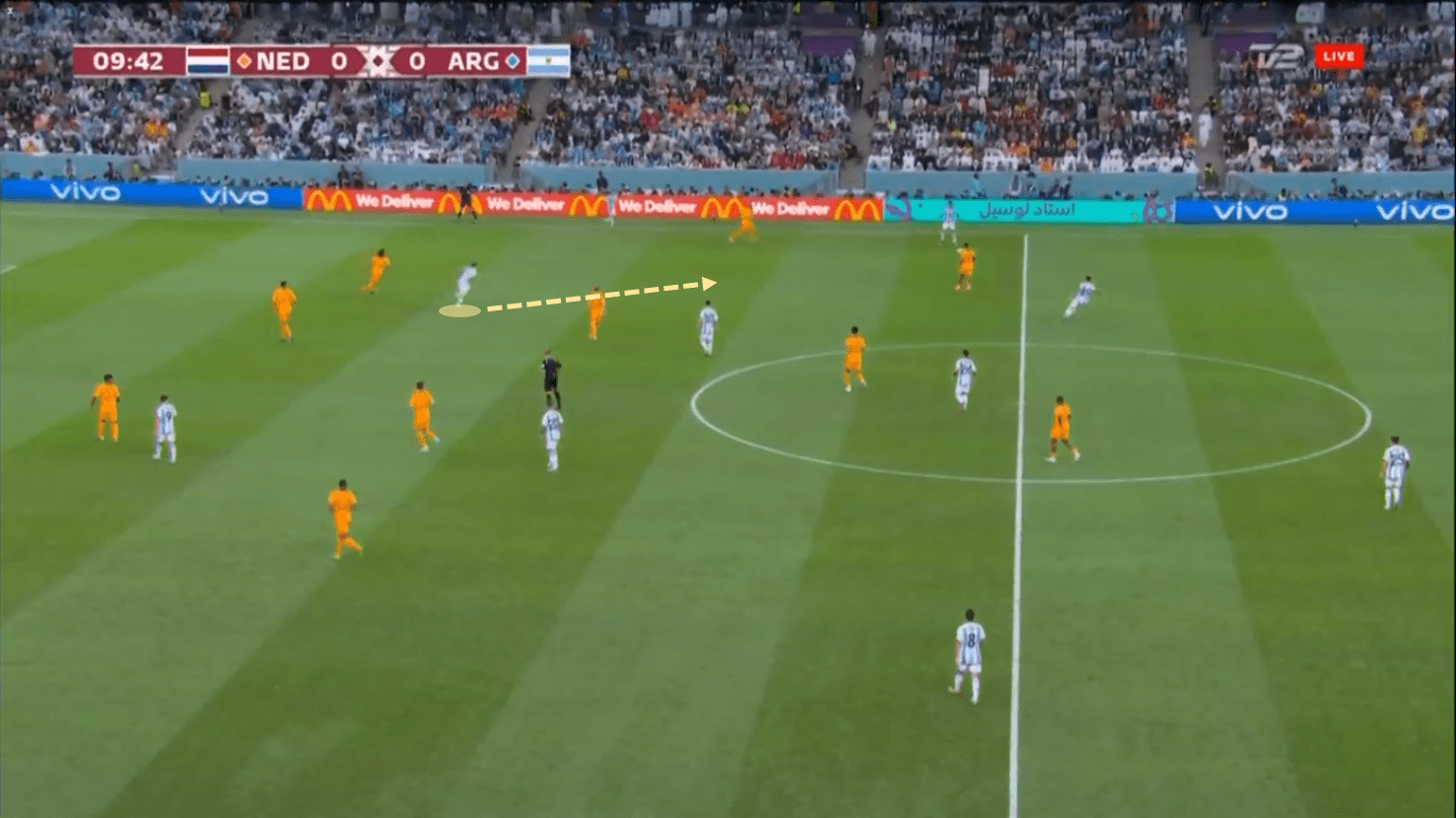

It was not the first time that a play like this was seen in the match. Even in the early stages of the game, almost reaching five minutes, Nahuel Molina stole possession, with his aggressive jumps if the ball was played to the wing, one of the most key things defensively for Argentina in the match. After that, he found the transition commander: Messi. Later, he would make the exact same movement, without going open in this case and attacking the rival box more. Something that surprised the Dutch since it was expected that in this type of situation the ball would be played from the outside, something that happened more to the left with Acuña.

This amplitude of which we spoke that was important for Argentina, was seen a lot in the last third of the pitch, where Messi’s typical passes to that side, after cutting inward, as he did in Barcelona for Jordi Alba, occurred in Constantly towards Marcos Acuña who provided a lot of threat through that party channel, appearing quite free since Argentina’s central overloads were recurring and a lot of usable space was left outside.

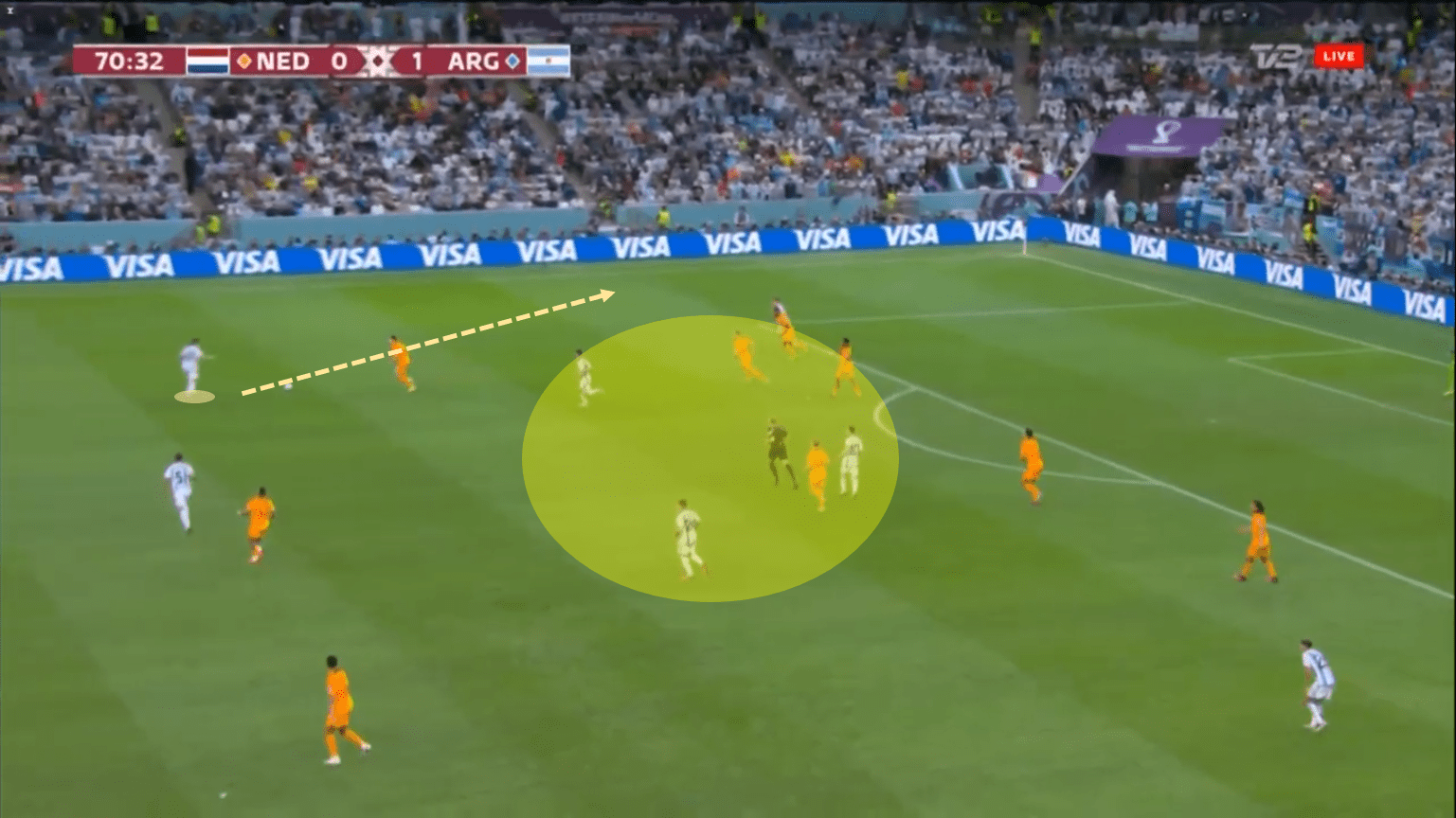

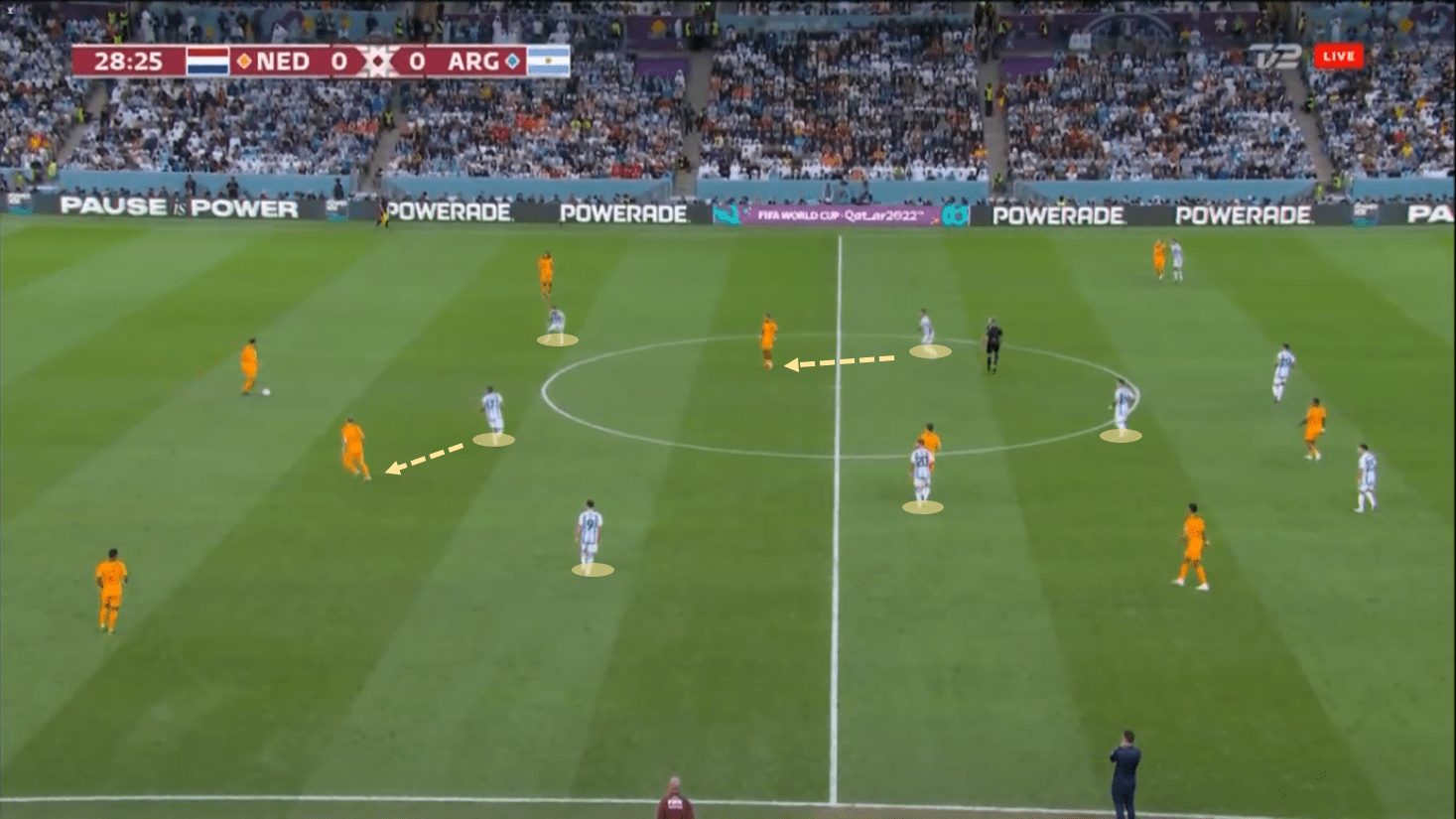

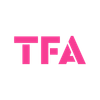

Talking and analysing Messi is already almost useless, everyone who has seen him knows what he can do, but what he offers collectively, precisely for the breadth of his team, is one of the most important things in Argentina. Scaloni’s team sought to take advantage of Lionel Messi’s player gravity as much as possible, who descended even close to the central defenders at times to then release the next pass to his wing-back, wide and alone.

In this image, we can see how Lionel attracts up to 4 rival players, three from behind and again, one from the front. The problem is that they could not profile him for a back-pass, and he offered his team progression in this way.

In the play prior to the penalty that the Netherlands conceded against Argentina, it was thanks to a penetrating carry by Marcos Acuña, of course, but the conversation started again, the central overloads to go out with the wl wing-back, in this case, the Sevilla player who, as we mentioned, went wider in attack than Molina at times.

Despite the fact that the pass was not progressive, due to poor control by MacAllister that he managed to resolve by passing the ball to Acuña, it is once again a sample of how Argentina generated both positional and numerical superiorities in different areas of the pitch.

However, one of Argentina’s weaknesses continues to be seen in sections of the match, which is its distance to finding players. With this change of principles and ideas, it becomes quite difficult for those of Scaloni to get used to the occupation of spaces. Rodrigo de Paul is one of those who have suffered the most from this, who has had to be making constant movements up and down.

Similarly, he is also part of a rotation, so he takes Messi’s place as forward, and he comes down more centralised to receive near the first stages of the build-up, and thus turn the game around with his receptions between the lines. It becomes difficult on some occasions, which is why rotations happen, but the weakness of their distance between the lines is not hidden when they have the ball and seek to create opportunities.

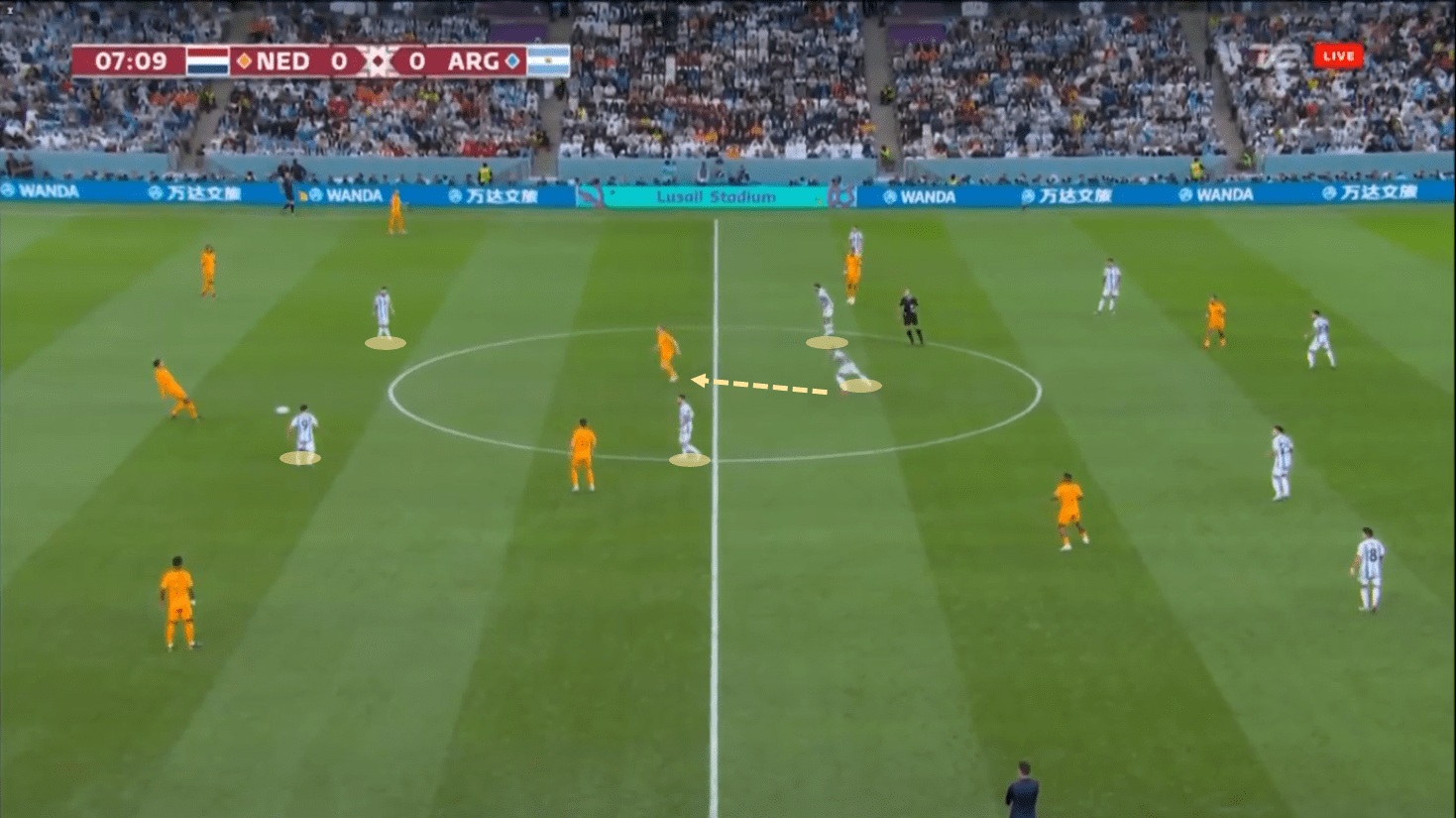

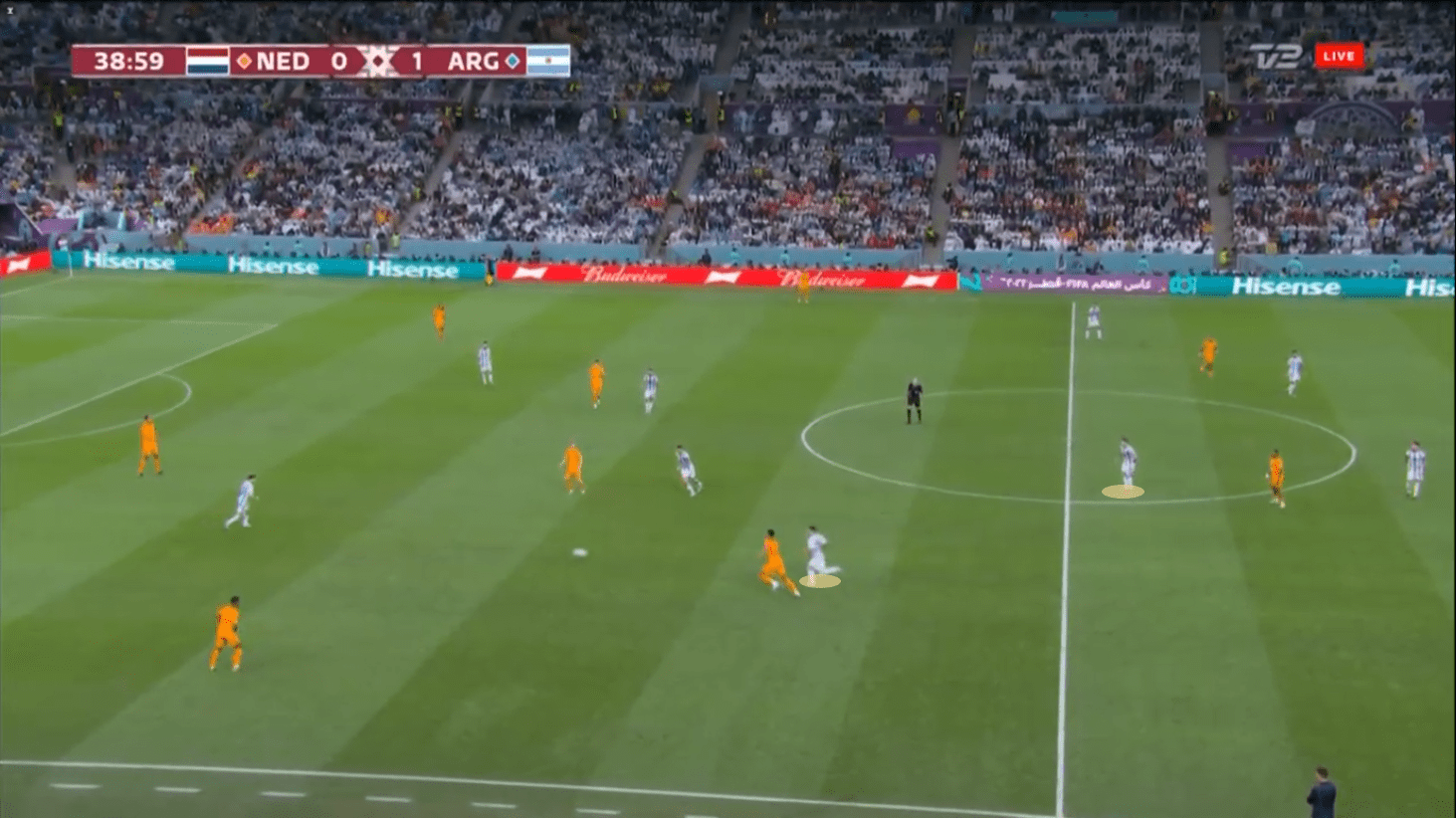

Defensively, the search was too aggressive by the Argentine team. With a 5-3-2 where their wing-backs barely played the ball outside, they jumped to score very hard and intense, Scaloni’s men sought, as with the ball, to fill the midfield with roles that they exchanged between man-marking and zonal. Netherlands is a team that with their #10 and his midfielders, made constant rotational movements between them, which could do damage before the first pressure from Argentina if it was ineffective.

Scaloni decided to delay his lines a bit, but not completely, thus managing to accumulate a lot of people in the middle, who even rotated with Julián Álvarez in front. If a player was looking to go down for the ball, a midfielder would chase him. If another decided to go to the side, the same. It was an extremely tough and aggressive pursuit by the Argentine midfield, which had a great tactical performance from all three, especially from the Atlético de Madrid player, Rodrigo de Paul.

When one of the rival midfielders sought to generate superiority by entering the line of defence or close to them to see the field more in front, Rodrigo de Paul was usually the one who chased them so as not to let them turn their body completely as they might offer passes between the lines. One of the midfielders always joined the line of Julián Álvarez and Messi, leaving behind his teammates going man-marking and Enzo Fernández, as a much more zonal #6.

The interesting thing about the aggressiveness was that, without fear of risks, when one of the midfielders went that far, with the possibility of a defensive back-five, Cristián Romero could put into practice or Lisandro Martínez, his skills that best fit within his game, the proactivity to jump and cut passes or tackle players far from his zone, in order to win dangerous balls for his team and keep the threat away from Emiliano Martínez’s goal.

On the other side, the same thing happened, since the profiles of both central defenders were suitable for this: The proactivity was so clear and the choice of players for this type of jump from their line to the outside to anticipate and intercept players or passes was so great. that Marcos Acuña was left as a centre-back on the left, something that has been seen on occasions, and Lisandro was the one who was going to cut the ball that was played through half-space. The aggressiveness and the timing to stretch the leg and hold players from the Manchester United defender made him tactically one of the best of the match.

Conclusion

With two great goals from the Netherlands by Wout Weghorst, the changes proved Louis Van Gaal right, who tried to be superior from above in the last minutes. However, despite conceding a goal in minute 90+11, in a set-piece quite prepared by the Dutch, and even by the striker who had already done it in Wolfsburg, the Argentines were mentally and physically superior to dominating the next 30 minutes, which with the entry of Di María in the second half of extra-time, was valuable with his speed and technique.

Comments