On the second matchday of Group E at the FIFA World Cup 2022, Germany fought a high-class duel thanks to a late urge phase to a 1-1 draw. This means that both teams still have a chance of reaching the round of 16. In the aftermath, this game can be considered the best quality game of the young World Cup so far.

Our analysis shows the strengths and weaknesses of Germany‘s pressing against the Spain side with the ball and why a system change is not always necessary to turn a game around. In this tactical analysis, we dive into the tactics of both teams and see how Hansi Flick’s Germany got to keep one point against Spain.

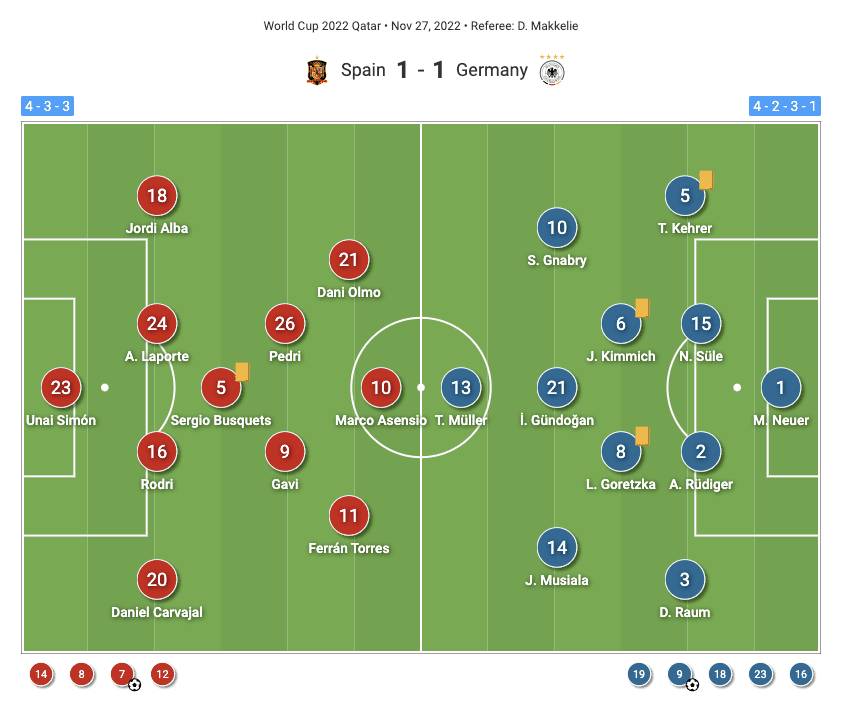

Lineups

As against Japan, national coach Hansi Flick opted for a lineup without a clear number 9 up front. Instead of Chelsea‘s Kai Havertz, this time Thomas Müller took on the central role on the offensive, who in the usual manner as a “Raumdeuter” also moved to other areas of the field, but was most active in pressing against the ball. An aspect with which Germany did not have a unique selling point on the field.

On the contrary, the Spaniards also opted for a false 9 attacker in Real Madrid‘s Marco Asensio, a fact that later turned out to be relevant to the game.

Germany’s pressing with Raum as key player

In their resounding victory against Costa Rica, Spain impressed on the one hand with their possession of the ball and on the other hand with their counter-pressing immediately after losing the ball. As a result, one of the most important tasks of the German team was to put pressure on the Spanish ball possession phases and to find solutions for overplaying the counter-pressing. And that the pressing of Germany should play an important role in the game was already evident in the first half.

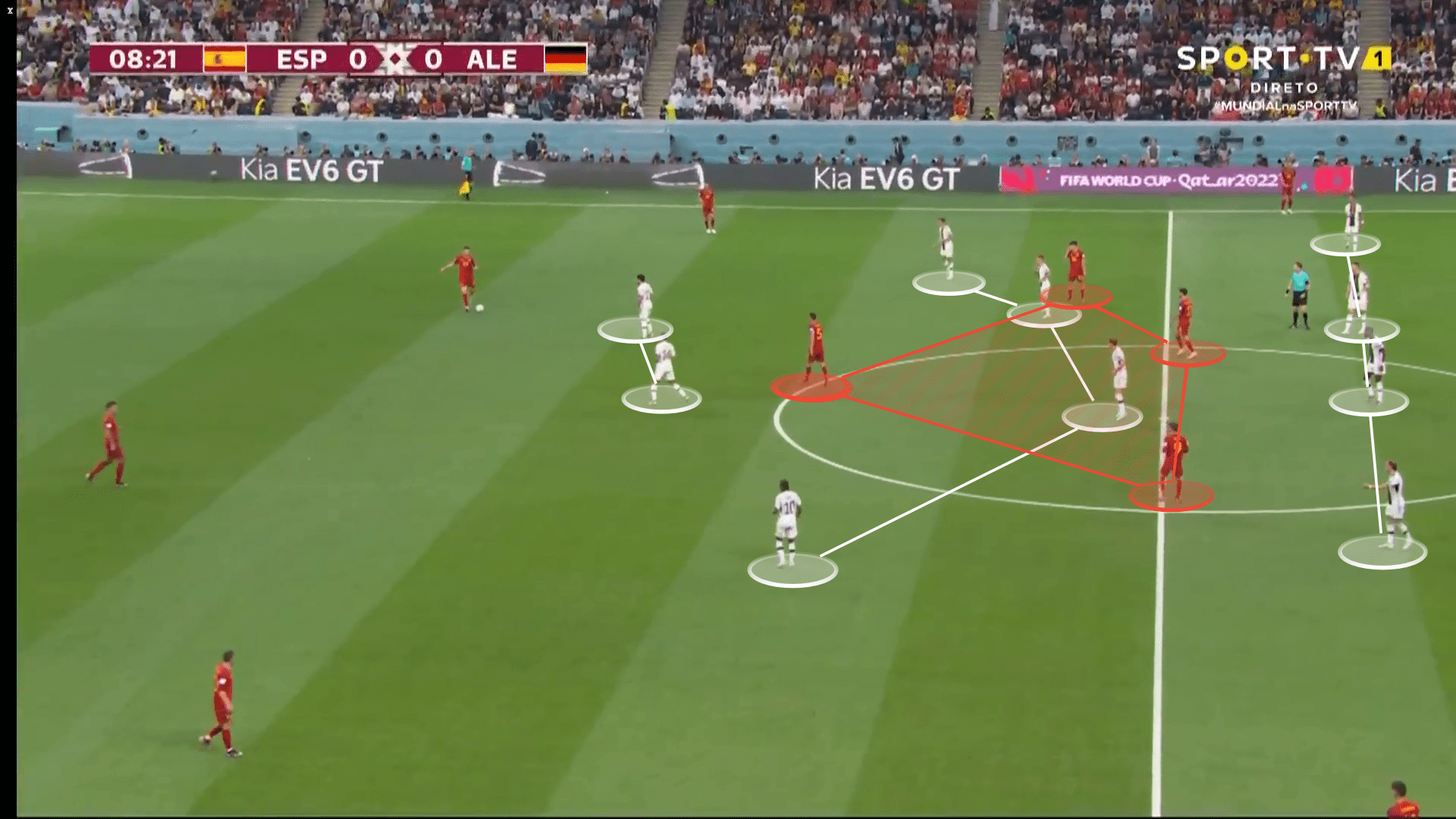

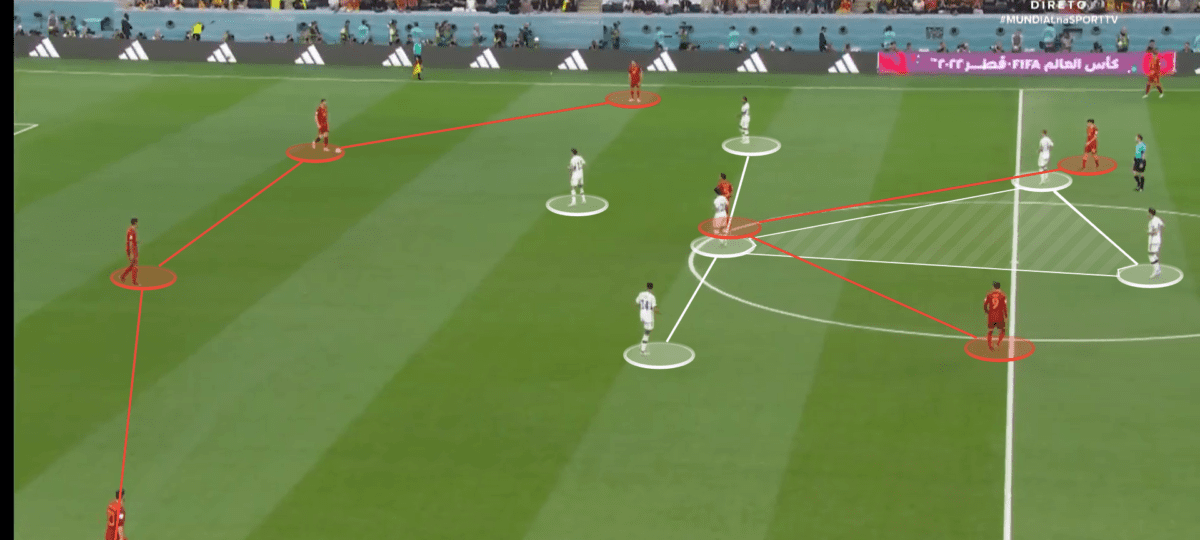

Spain played in their established 4-3-3 system, and Germany’s 4-3-3 was only slightly different in a 4-2-3-1. Bayern Munich‘s Kimmich and Goretzka formed a double six to accommodate the two Spanish attacking midfielders, while İlkay Gündoğan pressed in the number 10 position against Sergio Busquets as number 6 in the Spanish team. Flick implemented a man-marking system against three of the world’s best players under pressure while pressing in a mid-block.

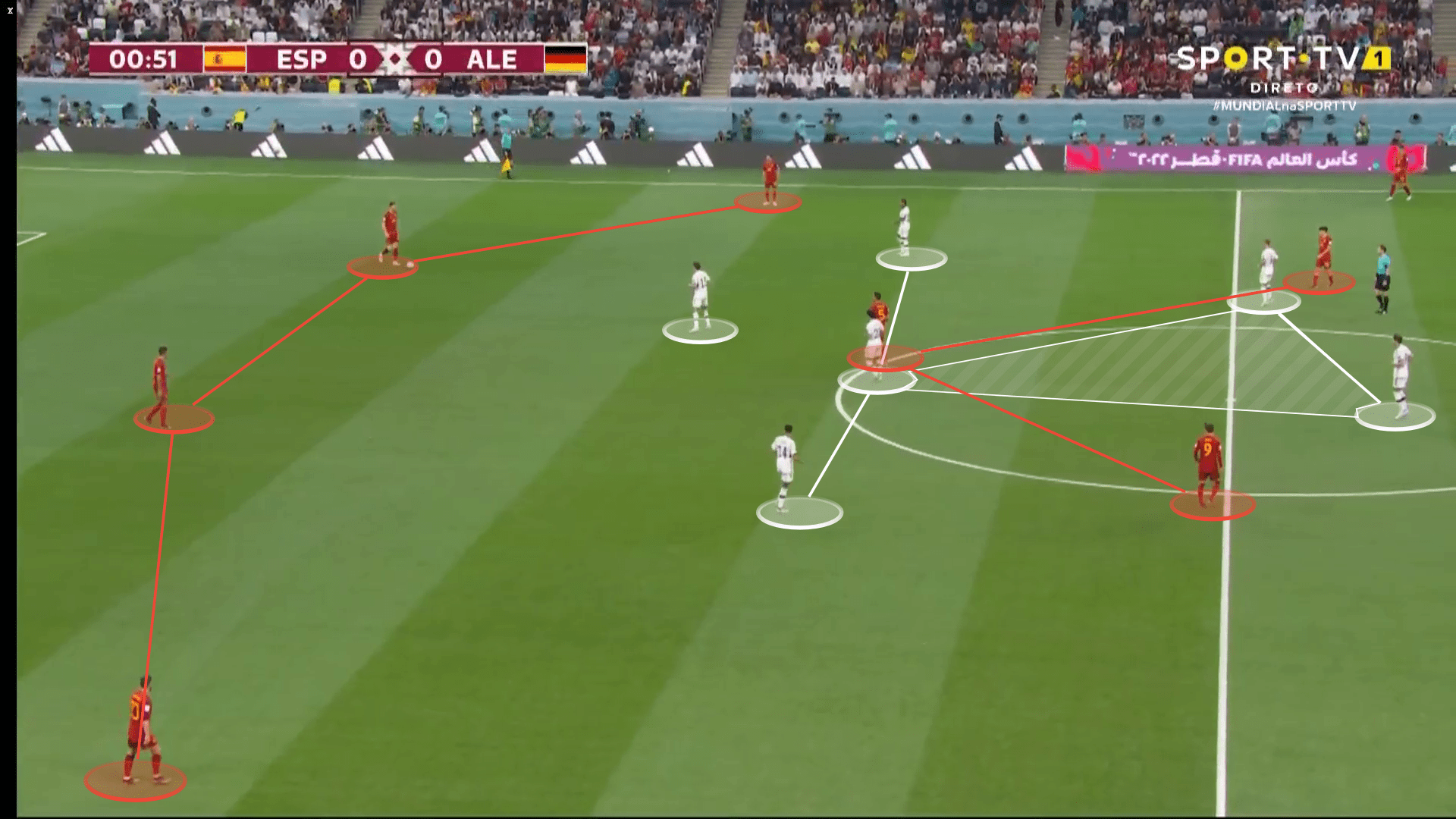

When Spain had possession of the ball, Germany prepared a plan to press the Spanish back four with Müller and the support of both wingers. The Spanish defenders were in a 4v3 situation, even five with Unai Simon as the goalkeeper. Initially, Spain was able to use this clear numerical superiority in the build-up, covered the German pressing by shifting to the full-backs and thus pushed the DFB-Elf into their half.

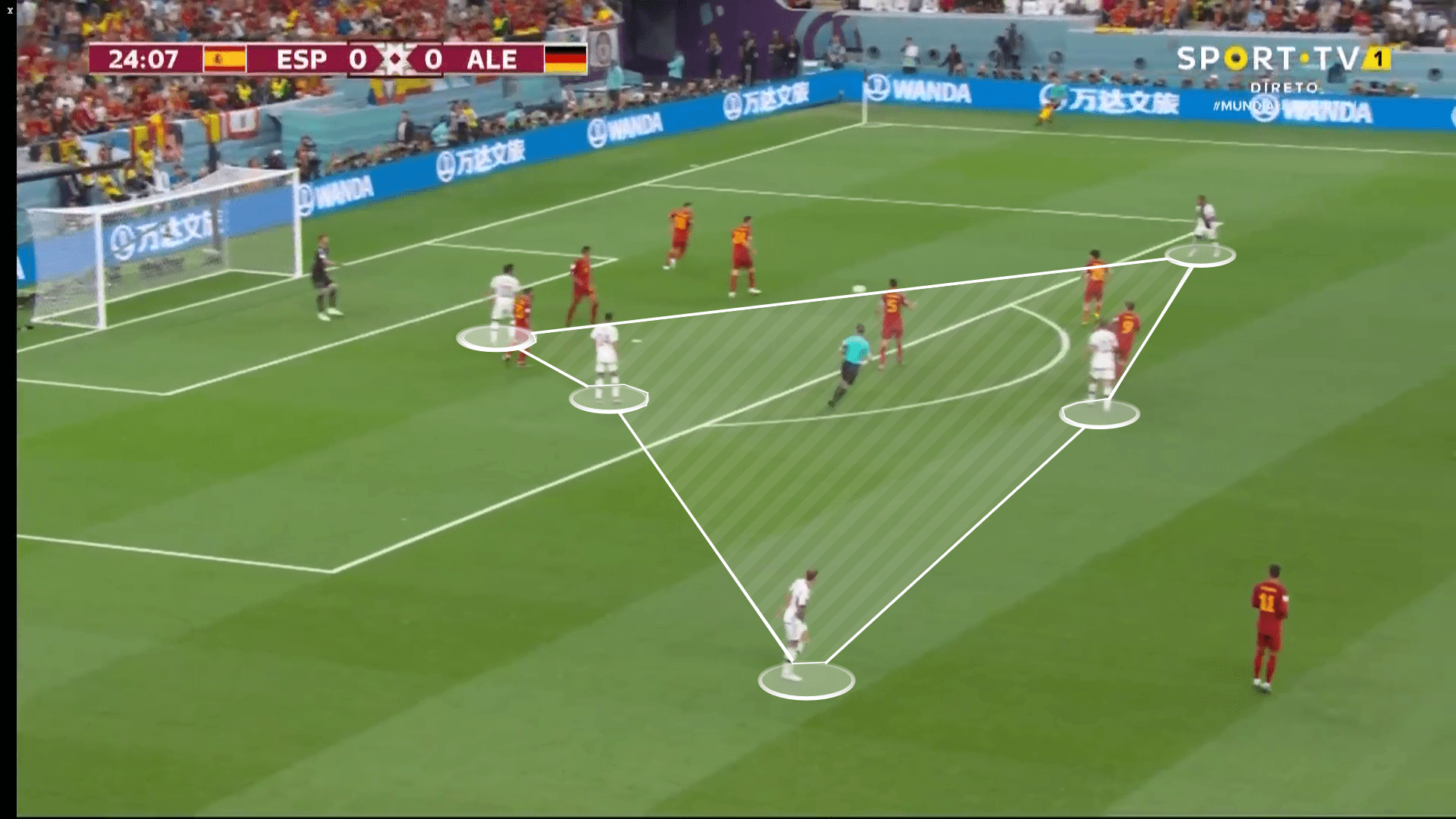

The key to the successful pressing was the support of left-back David Raum. Because he advanced and pressed on Spain’s free right-back when playing a pass, Germany were able to provoke ball wins again and again.

Behind them, the three remaining defenders pushed through to the side of the ball and briefly played evenly against the Spanish attacking trio. Thanks to this active pressing, the Flick-Elf kept getting the ball in promising positions in the Spanish penalty area and were also able to exploit the chances of Gnabry in the 25th minute and Kimmich in the 56th minute for a possible German lead.

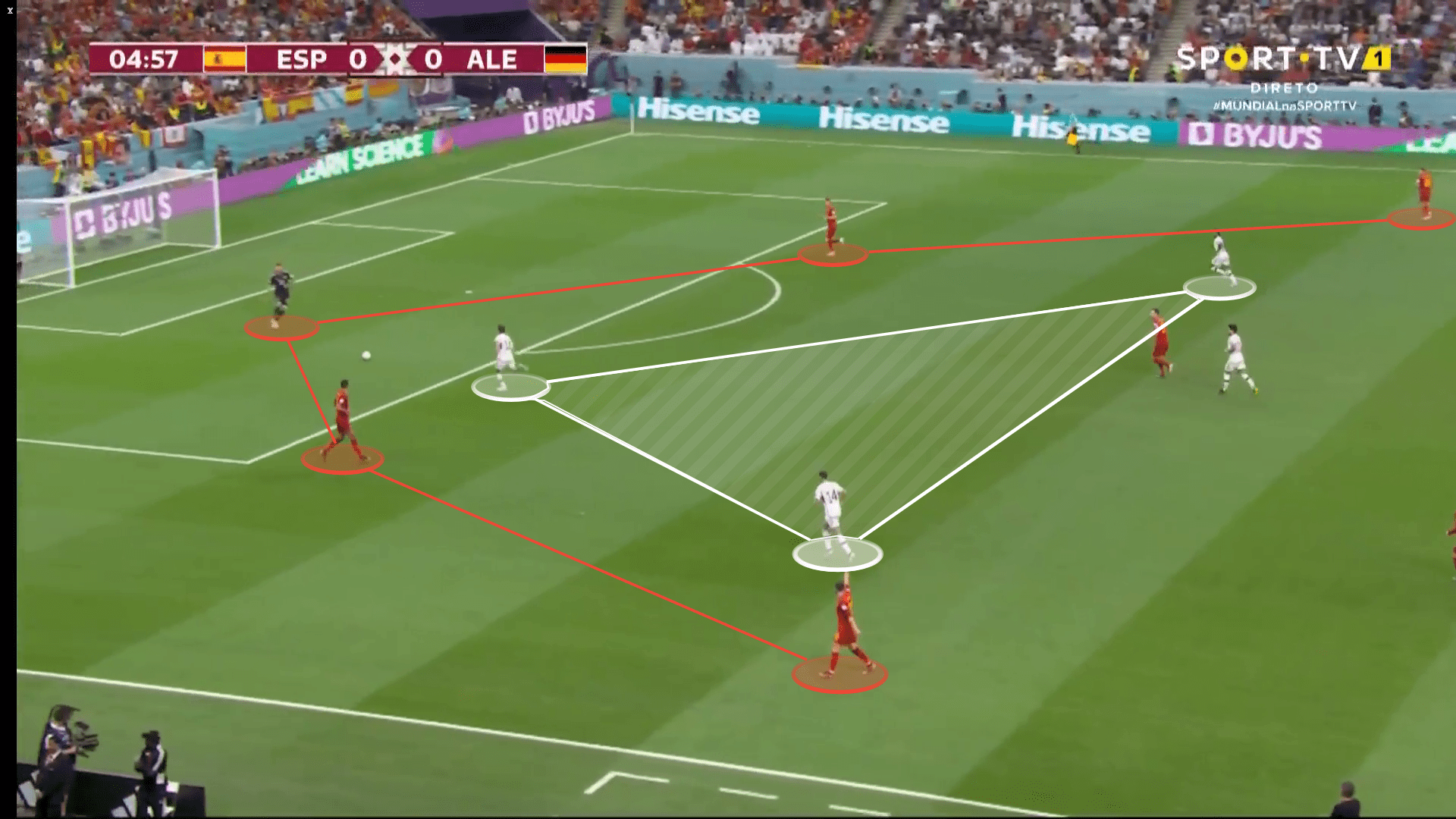

Depending on the situation, Gündogan also advanced to the second central defender of the Spaniards, who were not pressed by Müller, which resulted in a 4-4-2 depending on the situation. To make this possible, one of the two sixes usually pushed to a higher position.

In order to compensate for being outnumbered by the three Spanish midfielders, one of the central defenders from the chain also covered the pass. If this was done with good timing, an attack by the Spaniards could be prevented even after the first pressing line had been played over. However, if one of the two central defenders went to the front of the defence, there was also a gap in the defensive chain.

In a few moments, another Spanish attacker knew how to do this. Spain was able to counterattack from the depth with their own possession and Dani Olmo’s chance could only be prevented by a narrow offside.

Spain’s numerical advantage

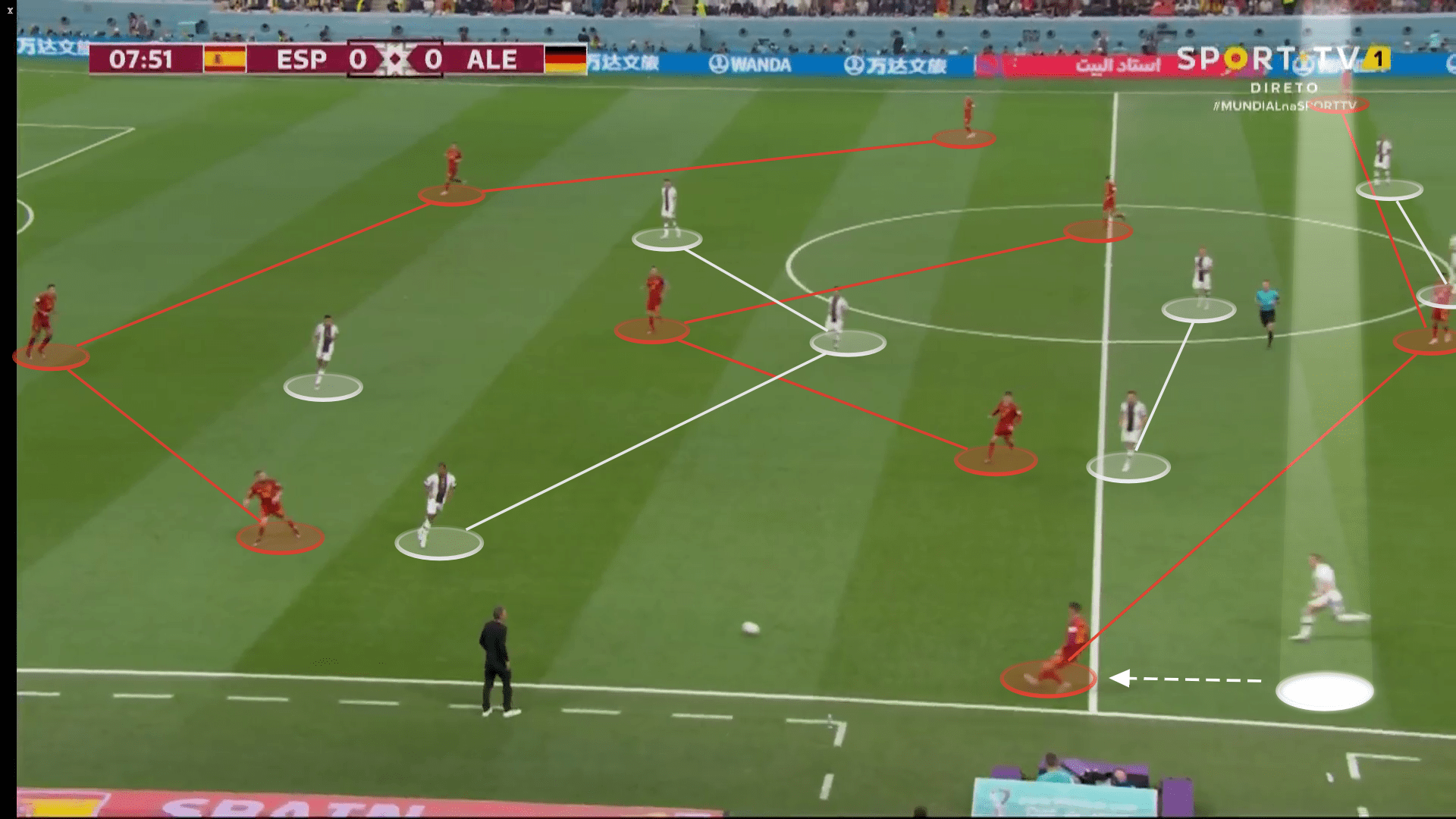

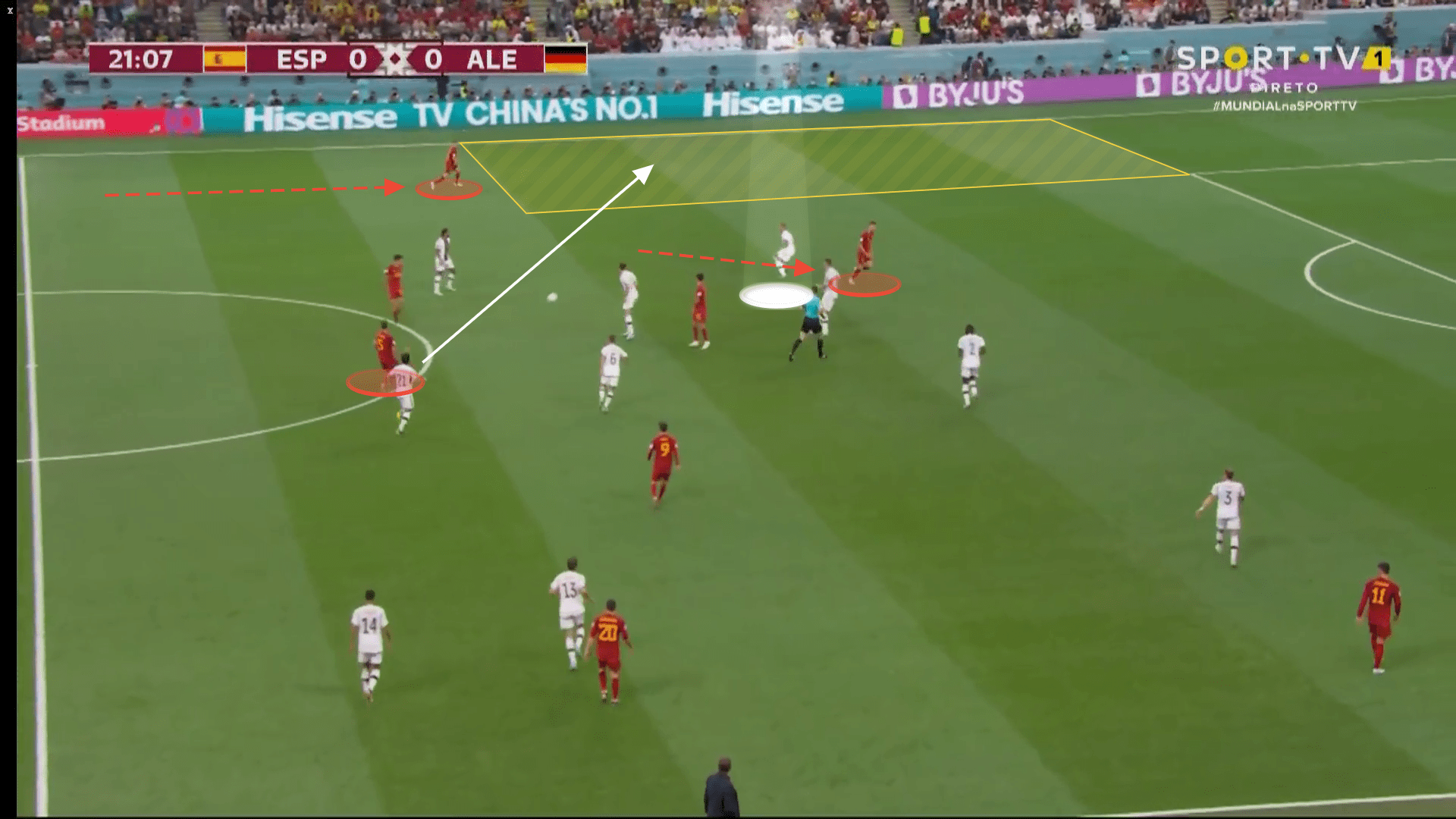

With Spanish possession of the ball in midfield, on the other hand, the biggest German weakness seemed to be on the wing. Through the offensive run of a Spanish full-back on the wing, Spain was able to create a two-on-one majority situation against the German full-back – a classic in 4-3-3 against 4-2-3-1. The reason for this was mostly a late defensive movement by Germany’s winger.

Germany’s full-back was briefly confronted with opposing wingers and full-backs. That’s how Spain got a crossbar in the 7th minute with Dani Olmo after Jordi Alba’s deep run pulled right-back Kehrer out of position, while Serge Gnabry’s attacking position offered little defensive support. The two Spaniards repeated the same process in the 22nd minute, only swapping roles, which put Jordi Alba in the final position.

A similar situation against Kehrer also provided the basis for Spain’s 1-0 goal (62nd minute). Direct access in central midfield could not be established, Gündogan, in a somewhat advanced position, allowed Busquets to open up in the centre, which shifted the game.

From the Spanish 4-3-3, Kehrer was again able to create an access problem on the far side with a winger and high-positioned full-back. This closed the inside-positioned winger Olmo first and came too late for the full-back Alba so that the cross could no longer be prevented. Substitute Spanish striker Álvaro Morata converted the cross into a 1-0 lead, also because central defender Süle lost his duel in the penalty area.

Golden substitutions

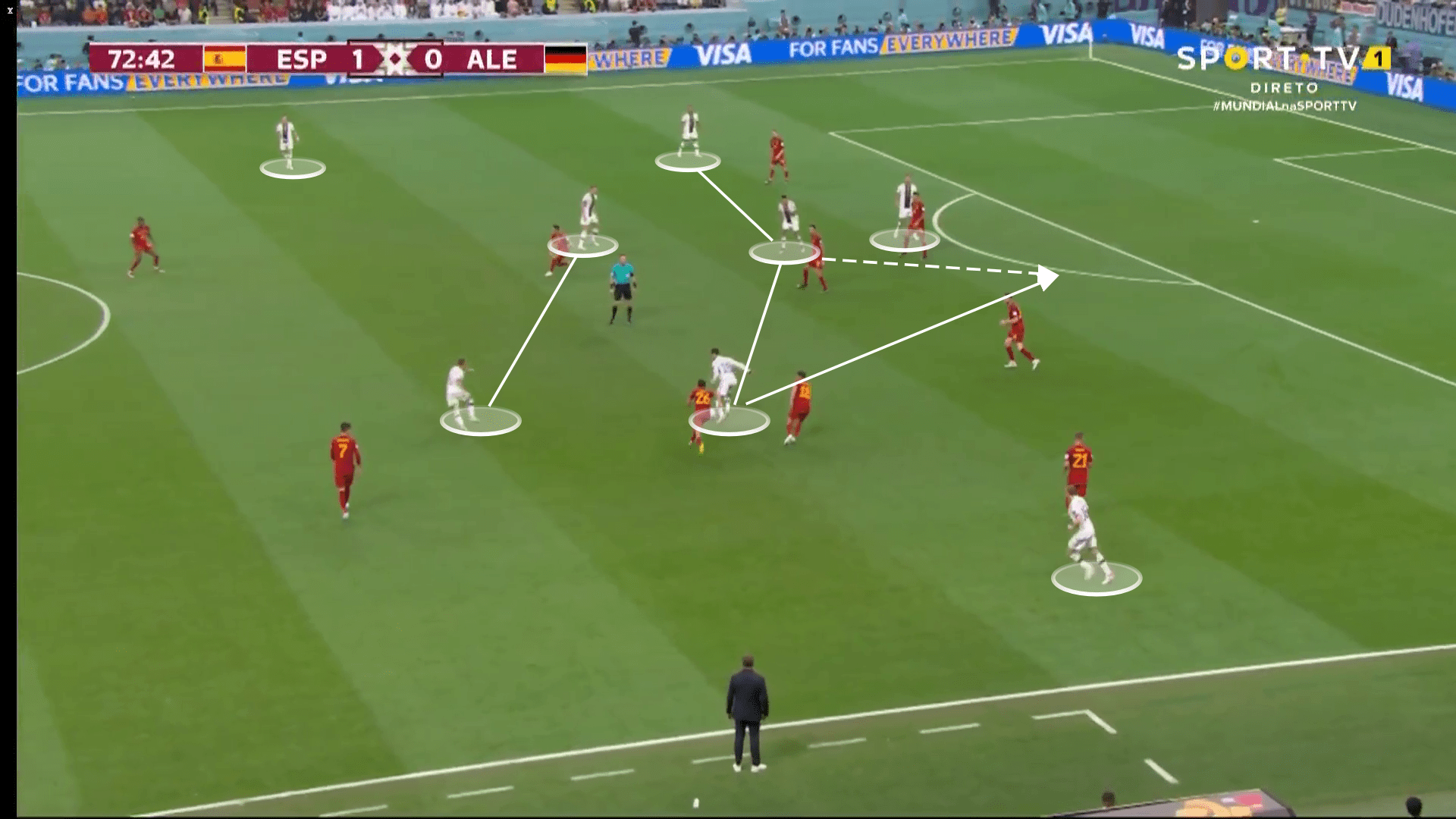

The deficit forced Flick to act. However, there was no need for a change of a tactical nature in the form of a system change since access to the pressing was definitely there. Flick still had to accept the defensive weaknesses that the pressing system brought with it in order to be able to set enough accents offensively. In this respect, the coaching team around Flick decided to make personnel changes rather than a system change. They did the same as Spain and brought in a striker in Niclas Füllkrug, and Flick also filled the positions on the right wing with Leroy Sané and Lukas Klostermann.

Without choosing a different basic formation, Germany was still able to develop more offensive power and at times even pressed Spain in their half. Jamal Musiala also got a new role in the course of the change. He was allowed to play a more central role as a number 10 in behind the striker.

Musiala created his own chances from more central areas and assisted striker Füllkrug, who scored to make it 1-1 in the 83rd minute. It’s ironic that both sides’ substitute strikers scored the goals after the game had previously lacked goals.

Conclusion

An understandable, but not entirely logical consequence of the success with Füllkrug as a striker would be to call this a German saviour. The positive thing is that the attacker gives the German game an element in the penalty area that is otherwise in short supply. The German team lacked his physique and his final strength at some moments before and yet Müller’s long pressing paths were enormously important in the first half and therefore presumably important preparatory work in order to often put pressure on Spain’s build-up play early on.

It remains the case that, similar to what happened against Japan, there is no lack of offensive options. Especially after the offensive changes, there were definitely chances for more goals. The pressing also seemed much better coordinated than against Japan, and Germany should continue to build on this in order to be able to conceal one or the other defensive weakness in the further course of the World Cup.

Comments