The German national team started the World Cup in Qatar with a defeat. The team of national coach Hansi Flick lost their opening game against Japan despite many chances and a deserved lead of 1-2 (1:0) and they already have to worry about reaching the round of 16.

Germany had the game under control for a long time, but then made serious mistakes defensively. Ilkay Gündogan scored from the spot for the DFB team, and then Ritsu Doan from Freiburg and Takuma Asano from Bochum turned the game around. Germany has thus given up a victory that was believed to be certain.

In this tactical analysis, we dive into the tactics of both teams and see how Hansi Flick’s Germany lost the first game of the group stage.

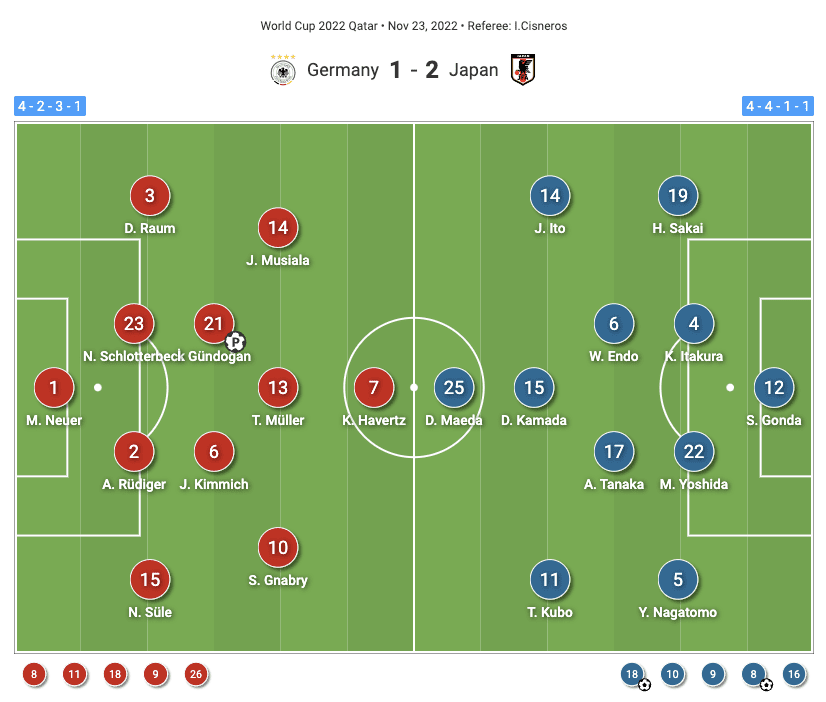

Lineups

Coach Flick had sent his team onto the field in the proven and now well-established 4-2-3-1 system. At the front, Kai Havertz should convert the attacks of Germany into goals, at the back Manuel Neuer should fend off the attacks of the Japanese without a “One Love” bandage on his arm. In between, the national coach relied on a back four with David Raum, Nico Schlotterbeck, Antonio Rüdiger and Niklas Süle as well as a lot of playful quality with Joshua Kimmich, Ilkay Gündogan, Jamal Musiala, Thomas Müller and Serge Gnabry. The goal was clear: make a game and win the game.

Japan lined up with Gonda as the goalkeeper and with Sakai, Itakura, Yoshida and Nagatomo in the defensive line. Endo and Tanaka were the double-pivot, while Ito, Kamada and Kubo played in offensive midfield. Maeda started as striker in the 4-2-3-1 formation on paper.

Pure Domination

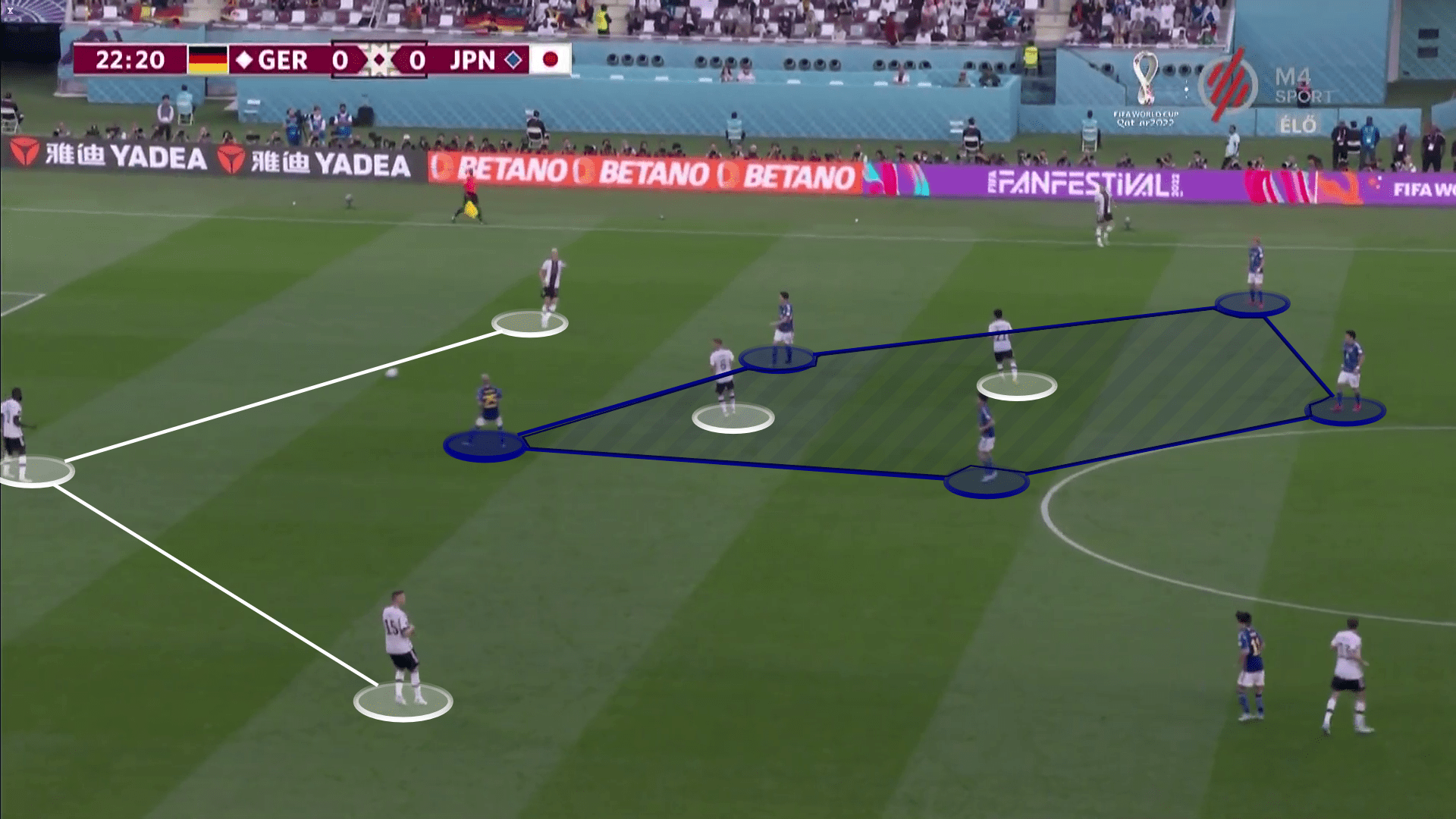

Hansi Flick’s instructions were then put into practice, at least in the first 45 minutes. The German players, who covered their mouths during the mandatory team picture and thus sent their silent protest to FIFA, gained more than 75 percent possession in the first half and often acted according to the same pattern. In possession of the ball, left-back Raum moved into the offensive and gave Musiala more freedom.

The back four became a back three, and youngster Musiala acted as a second playmaker and boosted the offence mainly through the middle. Süle was lined-up as a conservative right-back while Raum positioned himself high and wide on the left wing. It is a shape that Pep Guardiola at Manchester City and Mikel Arteta at Arsenal implement with Cancelo or Tierney holding the width on the left with a technical number 10 tucked inside (Grealish or Smith-Rowe).

But the three-man structure in particular seemed hesitant and not particularly sovereign at the beginning of the game. Within the back three, the half-backs Süle and Schlotterbeck were particularly cautious and played the ball across rather than forward without much pressure. As a result, Joshua Kimmich and İlkay Gündoğan had to keep dropping themselves to carry the ball forward.

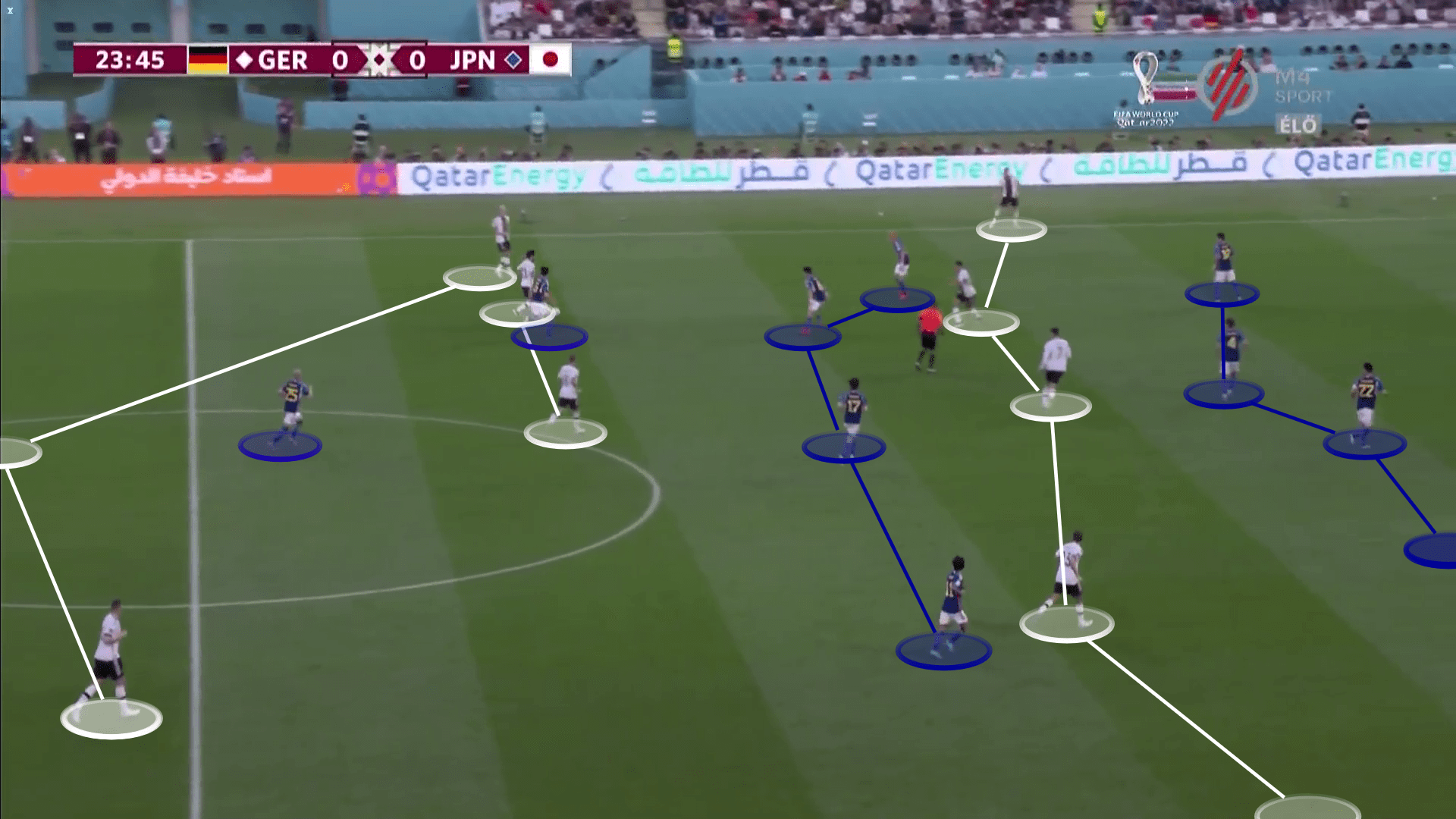

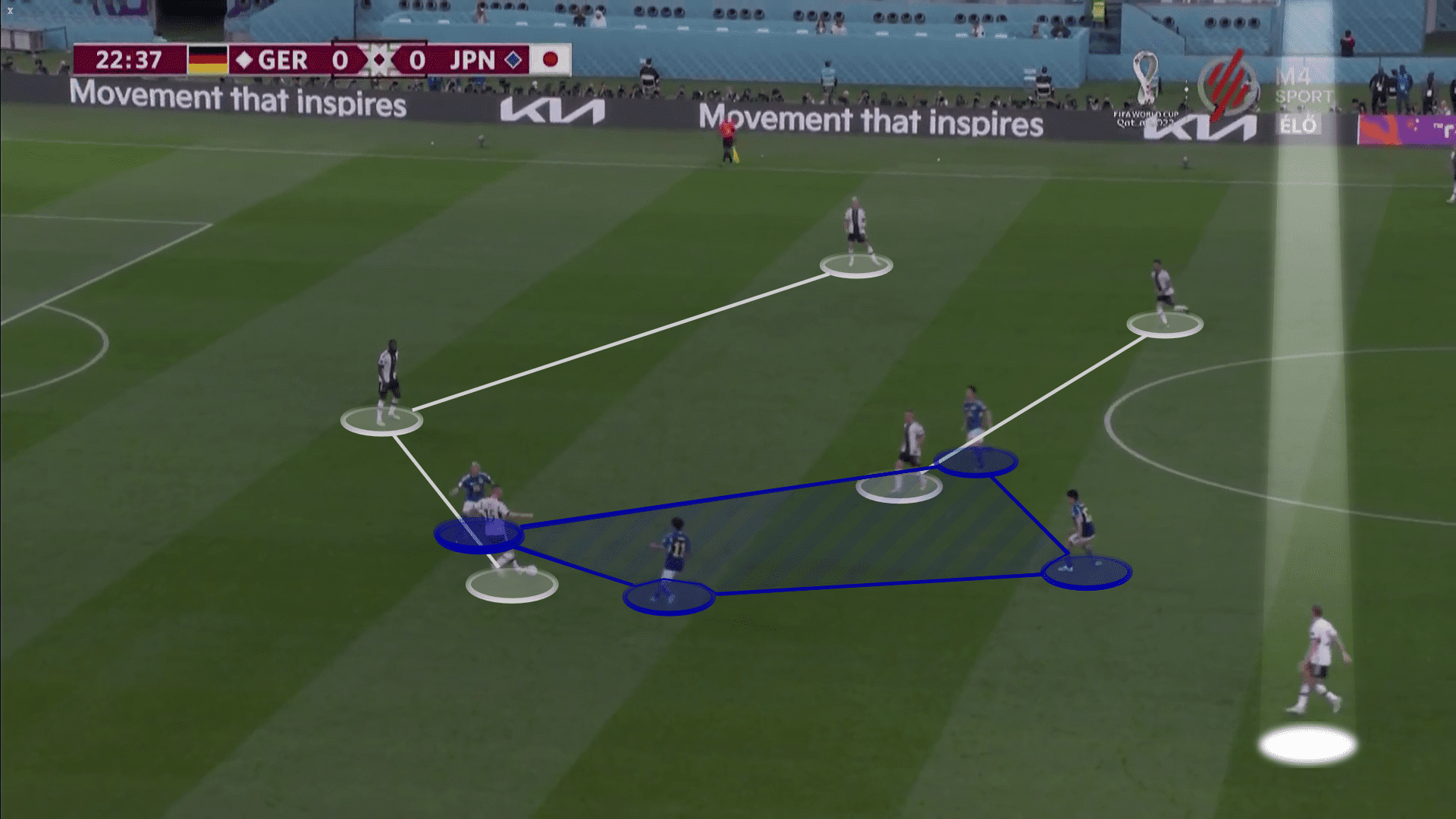

Especially the compact centre of the Japanese initially presented Germany with problems in the game structure. Japan aimed to close the centre with two chains of four, a tip and a hanging tip, and provoke ball wins there. This was also done several times in the first few minutes of the game, giving them opportunities to counterattack. However, since the greatest chance to counterattack only ended in an offside goal (8th minute), Germany got away without conceding a goal in the first round.

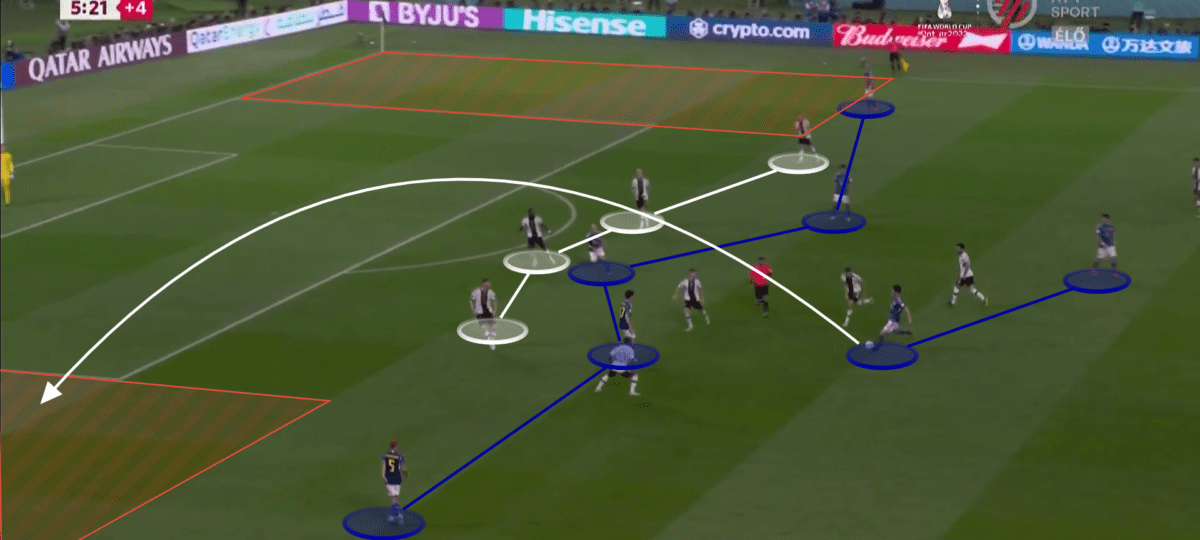

But, this 3-2-4-1 system with a midfield box led to a numerical advantage against the Japanese defensive midfielders. Additionally, Germany gained a numerical advantage in the first line (5v4) against four defenders. This overload saw David Raum free with lots of space in several situations. So with patience, Germany were able to break down Japan’s 4-4-1-1.

Lack of goalscoring

The only catch: Germany didn’t create any real chances at first. The German game looked quite respectable up to the penalty area of the deep Japanese, but in the last third, there was a lack of penetrating power and accuracy against the multi-legged defence. Even if Germany have players like Kimmich and Gündogan, they need more creative passes in the last line. This would have led to more interchanges in Japan’s low block. Thomas Müller struggled to play progressive passes behind the defensive line but rather played to a close teammate. The short passing of him did not work out in terms of goal-threatening chances.

Germany played 422 passes in the first half – a record for any team of a match in a World Cup since the beginning of detailed data collection in 1966. However, this passing killed the attack. A player like Mario Götze would have been a good choice as he has the ability to break the lines of deep-lying opponents.

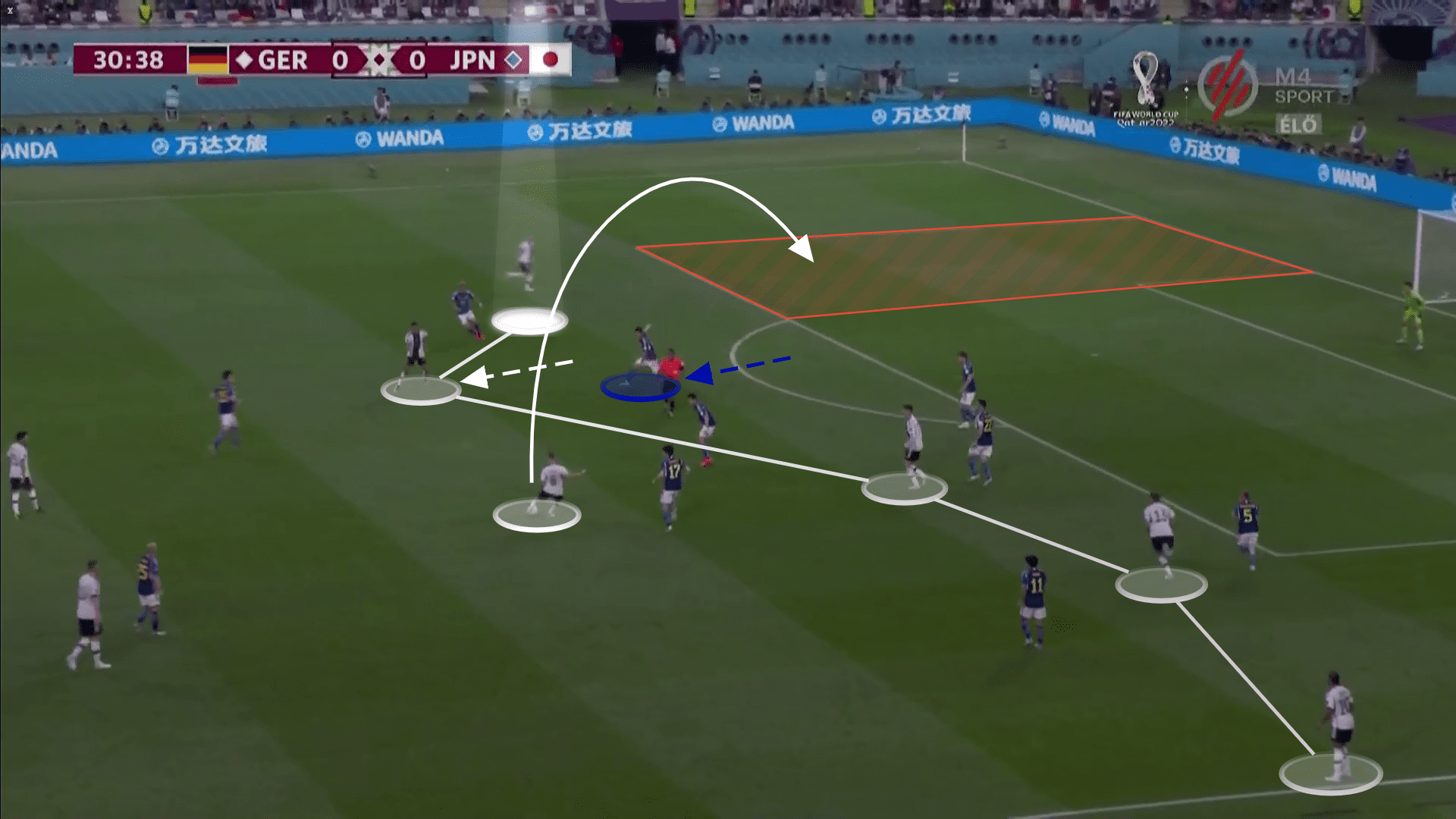

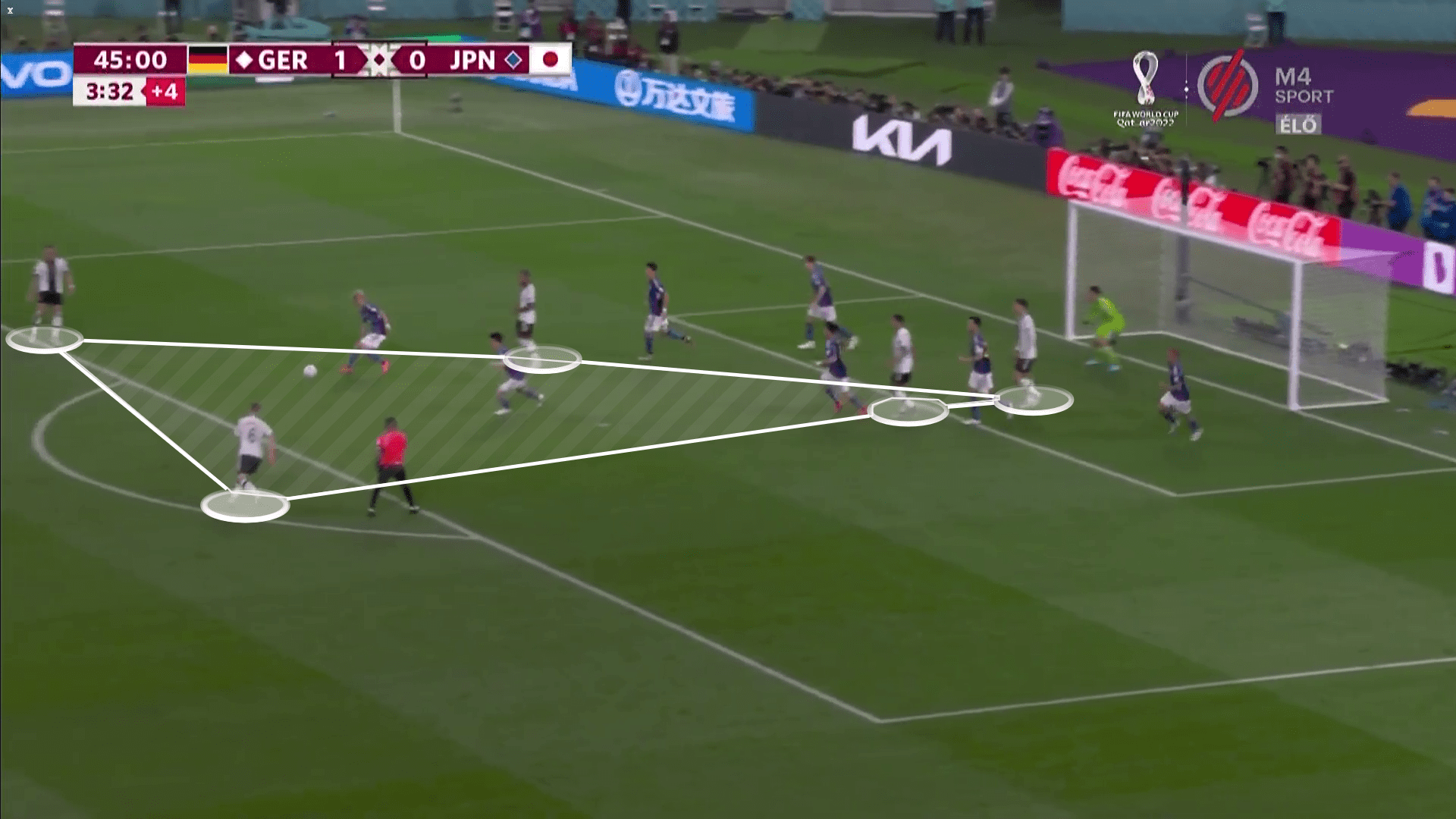

Significant: The most dangerous German scenes before the break were a header from Rüdiger after a corner kick (17th), two long-range shots from Kimmich (42nd minute) and Musiala (44th minute) and Gündogan’s successful penalty, that Raum, after a nice side move by Kimmich, had taken out. The latter was a prime example of how Germany tried to come in behind the defence. They relied on long, high and diagonal passes from their central midfielders Kimmich or Gündogan.

A goal from offside by Havertz in stoppage time also correctly did not count. This situation is still a very good example of how Germany tries to counterattack. They crowded the opponent’s box with players in order to leave no free space. So, Japan were not able to play out from the back and Germany gained back possession very early in a dangerous zone.

Since Japan showed nothing forward except for two actions by Daizen Maeda, who scored from offside very early after Gündogan lost the ball (8th) and very late headed next to the goal (45th + 6 minutes), the halftime lead of the German national team was well deserved.

Tactical changes were key

After the restart, the “Samurai Blue”, who had started with five Bundesliga legionnaires in the starting XI, dared to take a little more cover and made the game more open with a different tactical approach.

The result was initially more space for the German national team and several good chances. Germany was and remained the better team. Since there was a lack of efficiency in attack and substitutes Jonas Hofmann (70th) and Gnabry again (71st) missed the best opportunities, the Japanese stayed in the game. Coach Hajime Moriyasu’s side grew bolder as the game went on and created their own chances.

In the first half, Thomas Müller and Jamal Musiala have been key to Germany’s build-up. Depending on which site of play, one of both created an extra men against Japan’s 4-4-1-1 press. Germany built up in a 3 + 2 with Kimmich and Gündogan in slightly different lines. Müller was responsible to read Kubo’s movements. If he stepped out, Müller moved out wide and Gnabry kept wide and high.

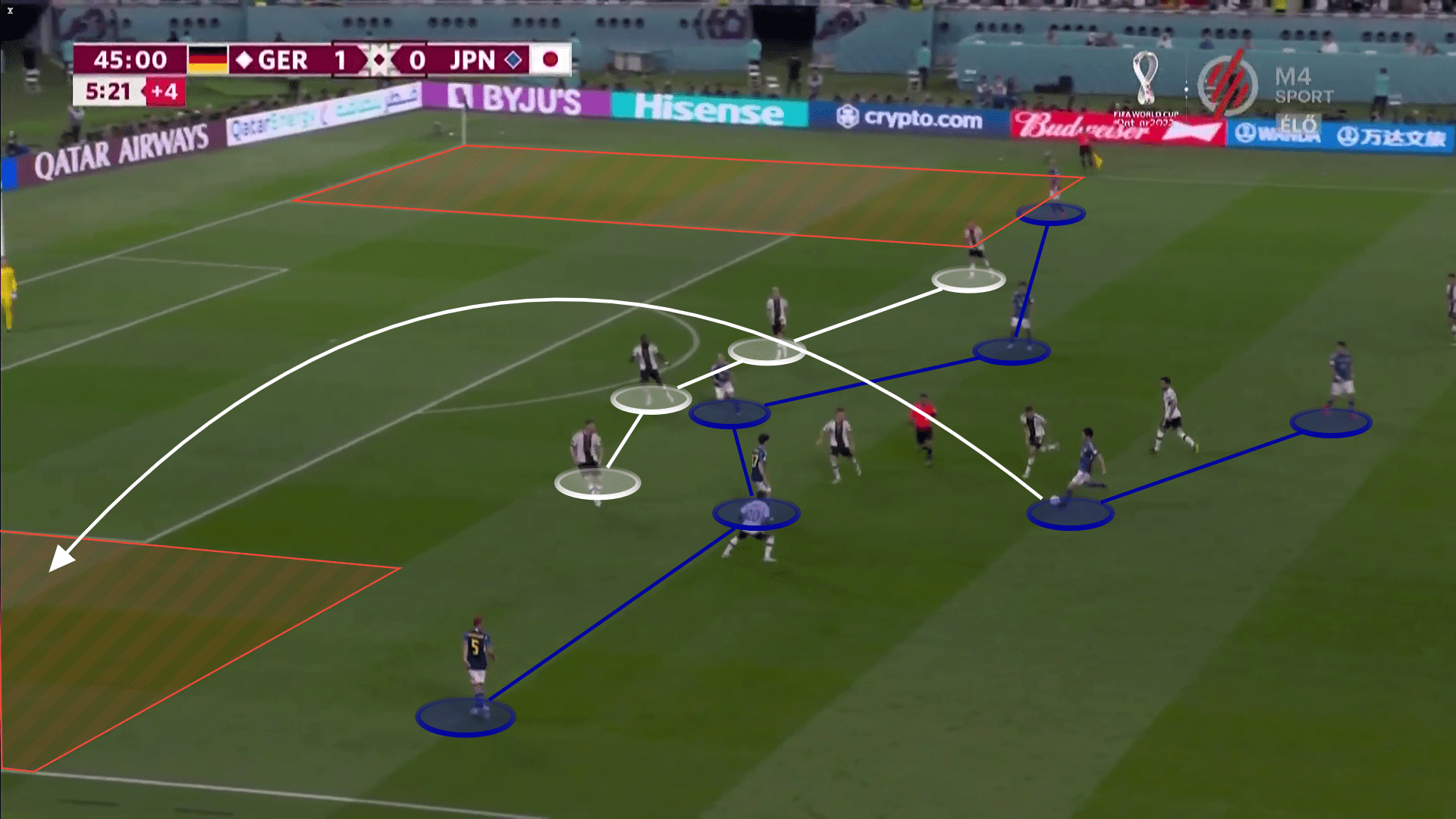

This, however, changed with Japan’s half-time substitution. Kubo left the pitch and Japan’s new shape with a back three allowed them to follow Müller and Musiala in between the lines. This was a very good half-time adjustment and a game-changer.

The Japanese full-backs in the back five were able to pick up Germany’s wingers, particularly David Raum, while the three central defenders defended the German attackers Thomas Müller, Jamal Musiala and Kai Havertz. In principle, a situation that allowed Japan to create 1vs1 across the board. Japan accepted a short-term deficit in the centre when one of the German attacking players dropped into midfield.

This approach required courage, as the 1v1 situations naturally also posed a defensive risk. If a German attacker was able to solve the 1v1, the remaining Japanese faced the problem of defending their own opponent or moving out to the ball carrier. Jamal Musiala therefore repeatedly proved his quality in dribbling and created some of the greatest German chances of the game (50th and 60th minute). It was the German exploitation of chances that kept the Japanese in the game.

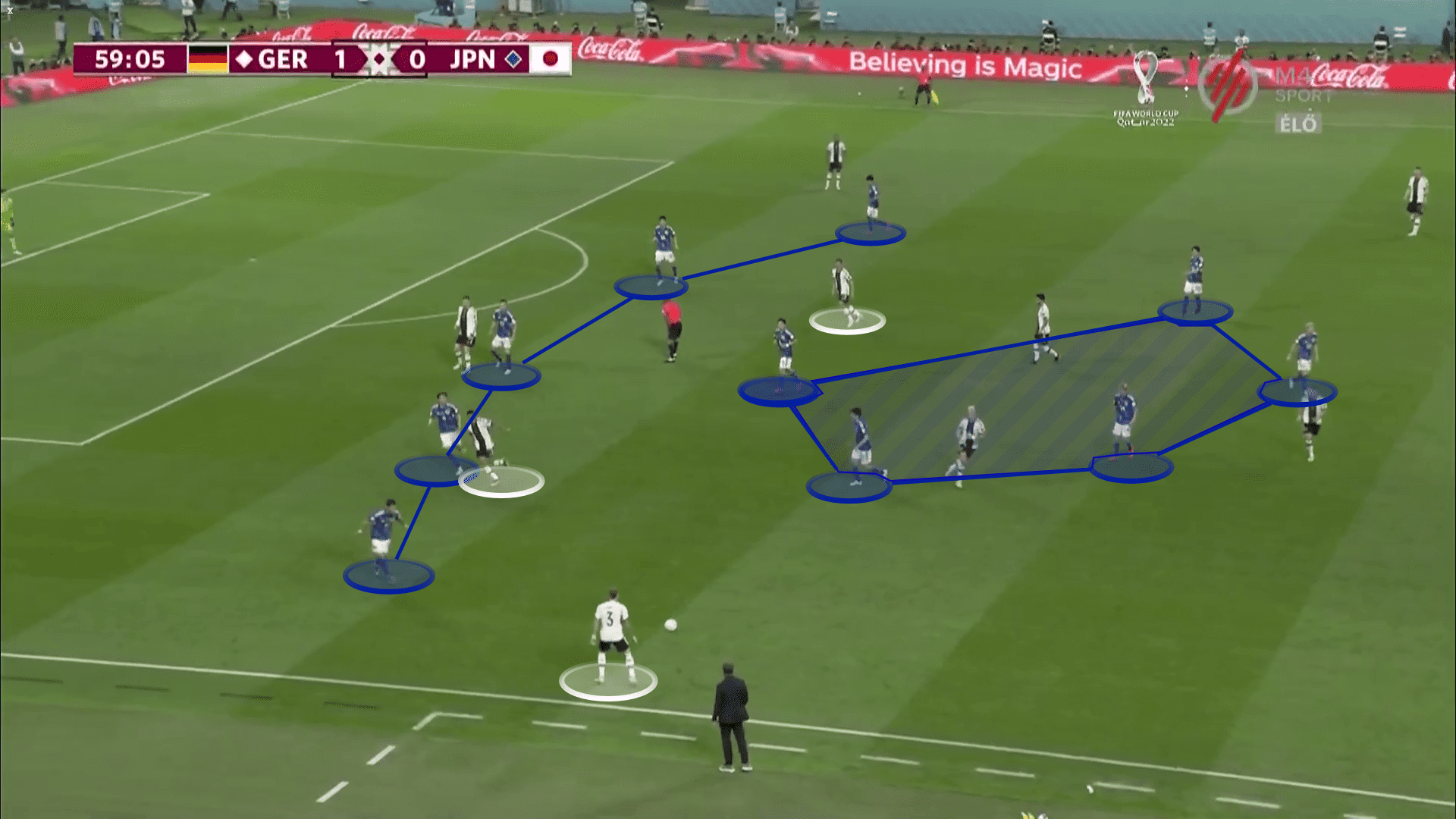

However, the new tactics of the Japanese also included a bolder attacking game, with a back three and high wingers. The Germans didn’t know how to take advantage of a nominal superiority in the centre with three central midfielders against the Japanese double six. In their own half, Germany increasingly had access problems. Japan followed a similar tactical plan to Germany in the first half and literally beat Flick’s team with their own weapons.

Like Germany in the first half, the Japanese wingers in the new basic formation were able to create a superior number against the German back four. With sometimes five players in the last line, Germany’s back four was overwhelmed to defend all attackers. Japan was able to free an attacker in the centre of the penalty area with sometimes simple, high chip balls, and Germany were lucky not to concede the equalizer in the 72nd minute.

After Neuer initially defused a shot from Junya Ito with a world-class save (74th), the German captain was powerless shortly afterwards. After a nice attack by the Japanese, Freiburg’s Doan was free to finish a few minutes after being substituted and punished the German usury with the equaliser. Certainly, luckily at this point, but the goal didn’t come out of the blue. And it got even better from the Japanese point of view: Just a few minutes later, Bochum’s Asano, who was also a substitute, escaped from Dortmund’s Schlotterbeck and turned the game around completely with a shot from a tight angle.

As a result, the German defensive network did not always appear solid. A supposedly easy long ball behind the defence reached Takuma Asano, who scored the 2-1 winner. Regardless of any number ratios on the pitch, Germany’s defensive line had lost its uniform height and Niklas Süle, as a full-back away from the ball, cancelled the offside. Individual and group tactical mistakes cost Germany the win against Japan.

Conclusion

The strong German attacking game not only put them in front but also enabled them to score more goals, as shown by this analysis. Despite Japan’s conversion, the offensive game seemed very variable, with moves down the wings and through the centre. However, opportunities for another goal remained unused, which was severely punished in the final stages of the game.

But the match also leaves doubts about Germany’s defensive stability. The changeover of Japan, similar to the German team to create a superior number with high wings against the back four, required courage.

Germany’s head coach Flick left no stone unturned and brought on comeback Mario Götze and debutant Youssafa Moukoko in the closing stages. The result did not change, despite a very good chance from Leon Goretzka (90+3). The changes came, but in the end, they came too late.

Everything is at stake for Germany in the next game against Spain on Sunday. As in 2018, the early end of the World Cup threatens.

Comments