After losing 1-0 to Costa Rica in their second game of Group E, Japan went into Thursday’s clash with Spain needing a win to guarantee their place in the round of 16 in Qatar. They achieved their 2-1 victory via two early second-half goals — the first coming from Ritsu Doan in the 48th minute and then the second coming from Ao Tanaka in the 51st minute. This ended up being enough to overturn the 1-0 lead Spain took in the 11th minute via Alvaro Morata.

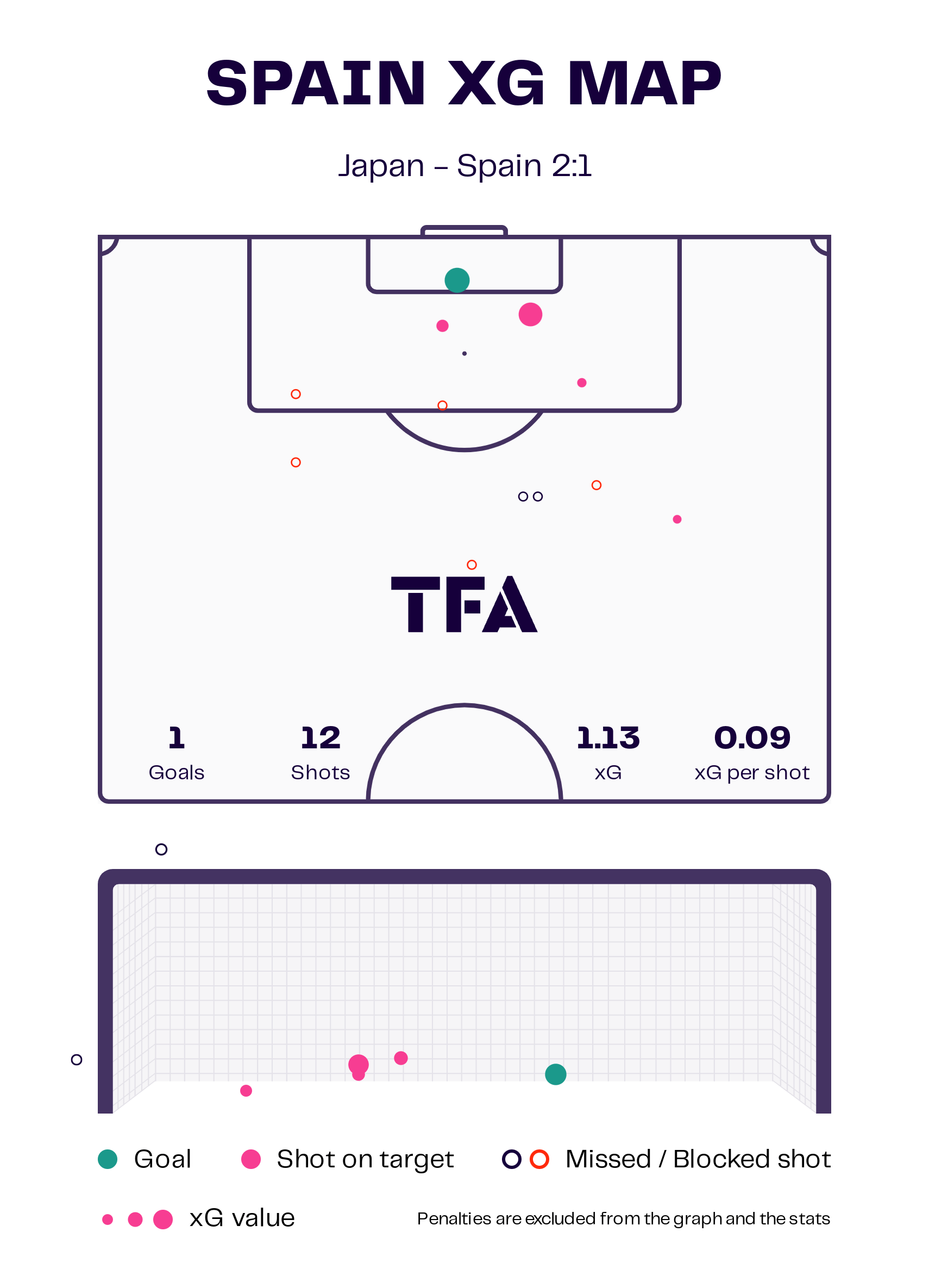

Spain dominated the game in terms of possession (83.31%) but things were relatively equal in terms of chance creation, with both sides generating 1.13 xG. Japan’s solid defence and ability to take their chances when they came on the counterattack were pivotal to their 2-1 victory. These two aspects of Japan’s performance will be analysed in detail, along with Spain’s performance in possession, to tell the tactical tale of this contest.

Our tactical analysis of this match will be divided into three distinct sections, along with our first section laying out the lineups and formations that both teams went with for this one. We hope that our tactical analysis provides some helpful insight into the key elements of both teams’ tactics from this World Cup fixture.

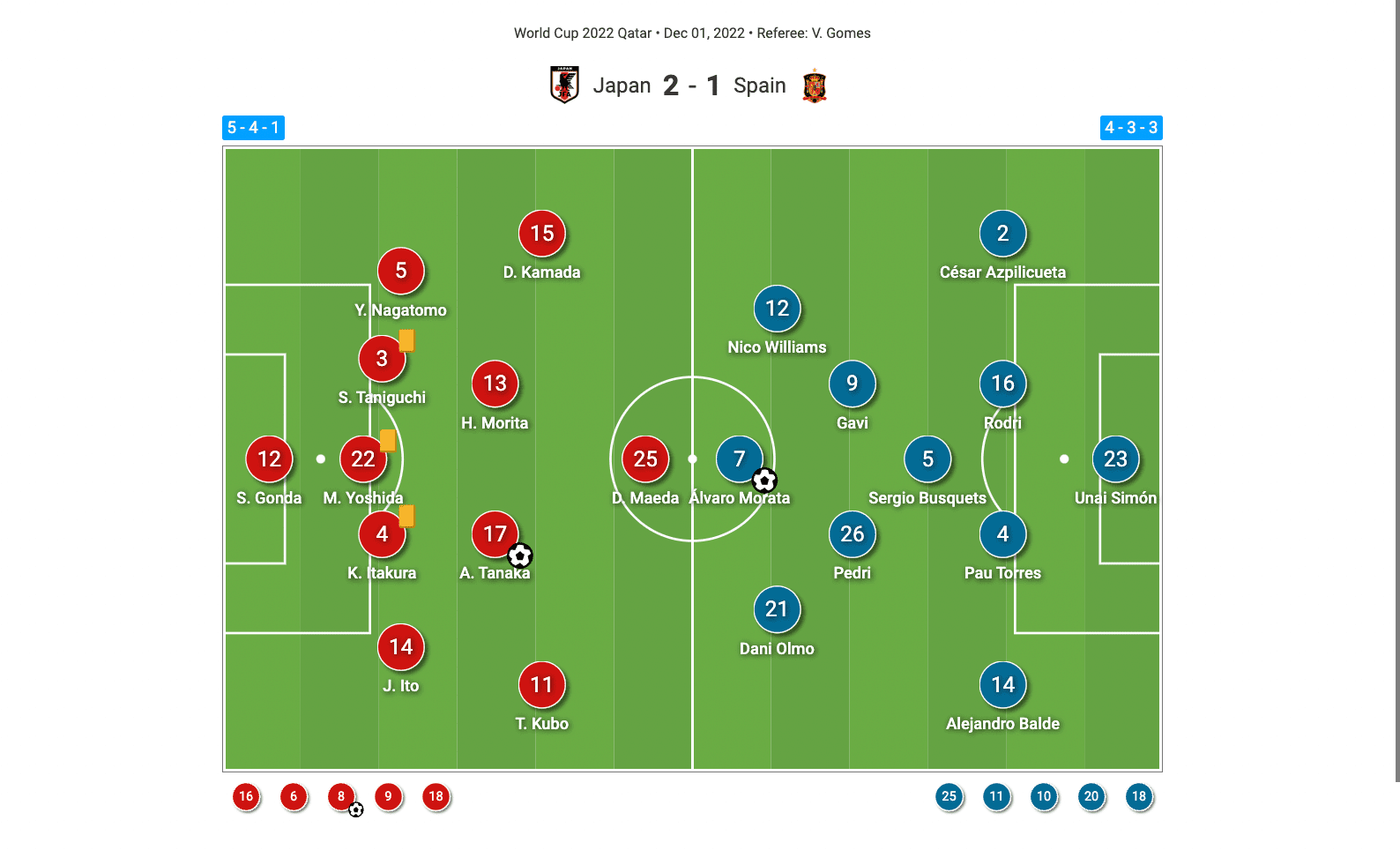

Lineups

Firstly, let’s look at how the teams lined up for this game. Starting with Japan, Hajime Moriyasu went with a 5-4-1 shape for the majority of this game, with his side spending a lot of time in a mid-low block. At the beginning of the second half, in particular, Japan played much more on the front foot and as a result, appeared in more of a 3-4-3 for that spell but throughout this game, for the most part, they lined up in a 5-4-1 shape.

Shūichi Gonda started in goal for Moriyasu, behind right wing-back Junya Ito, right centre-back Kou Itakura, centre-back Maya Yoshida, left centre-back Shogo Taniguchi and left wing-back Yuto Nagatomo.

At right midfield, we found Takefusa Kubo, with right central midfielder Ao Tanaka and left central midfielder Hidemasa Morita playing between him and left midfielder Daichi Kamada. Lastly, up front, Japan started with Celtic forward Daizen Maeda.

The Samurai Blue made five substitutions over the course of this match, The first two substitutions came at half-time when goalscorer Doan replaced Kubo and Kaoru Mitoma took over from Nagatomo. In the 62nd minute, Maeda made way for Takuma Asano, Arsenal‘s Takehiro Tomiyasu took over from Kamada in the 69th minute to add some extra defensive solidity for the closing stages of the match and for Japan’s final substitution, Wataru Endo replaced Tanaka in the 87th minute to help his side see out the game.

As for Spain, Luis Enrique set his side up in their typical 4-3-3 shape. Unai Simón started in goal for La Furia Roja, behind a back four consisting of César Azpilicueta at right-back, Manchester City midfielder Rodri at right centre-back, Villarreal’s highly admired Pau Torres at left centre-back and Alejandro Balde at left-back.

Legendary Sergio Busquets started at the base of the all-Barcelona midfield three, with Pedri and Gavi playing ahead of him. Nico Williams started at right wing, with Dani Olmo at left wing and Morata up top.

Like his Japanese counterpart, Enrique made all five of his substitutions in this fixture and the first also came at half-time, when Dani Carvajal replaced Azpilicueta. Spain freshened things up again after the two Japan goals, with Ferran Torres coming on for Williams on the right and Marco Asensio taking over from Morata up front.

The Spanish made their final two changes fairly early — the 68th minute — when Ansu Fati took over from Gavi and veteran left-back Jordi Alba came on for Balde. However, these substitutions proved inadequate for breaking down the solid Japanese defence once more and the game ended 2-1 following Japan’s early second-half goalscoring frenzy.

Spain’s possession dominance

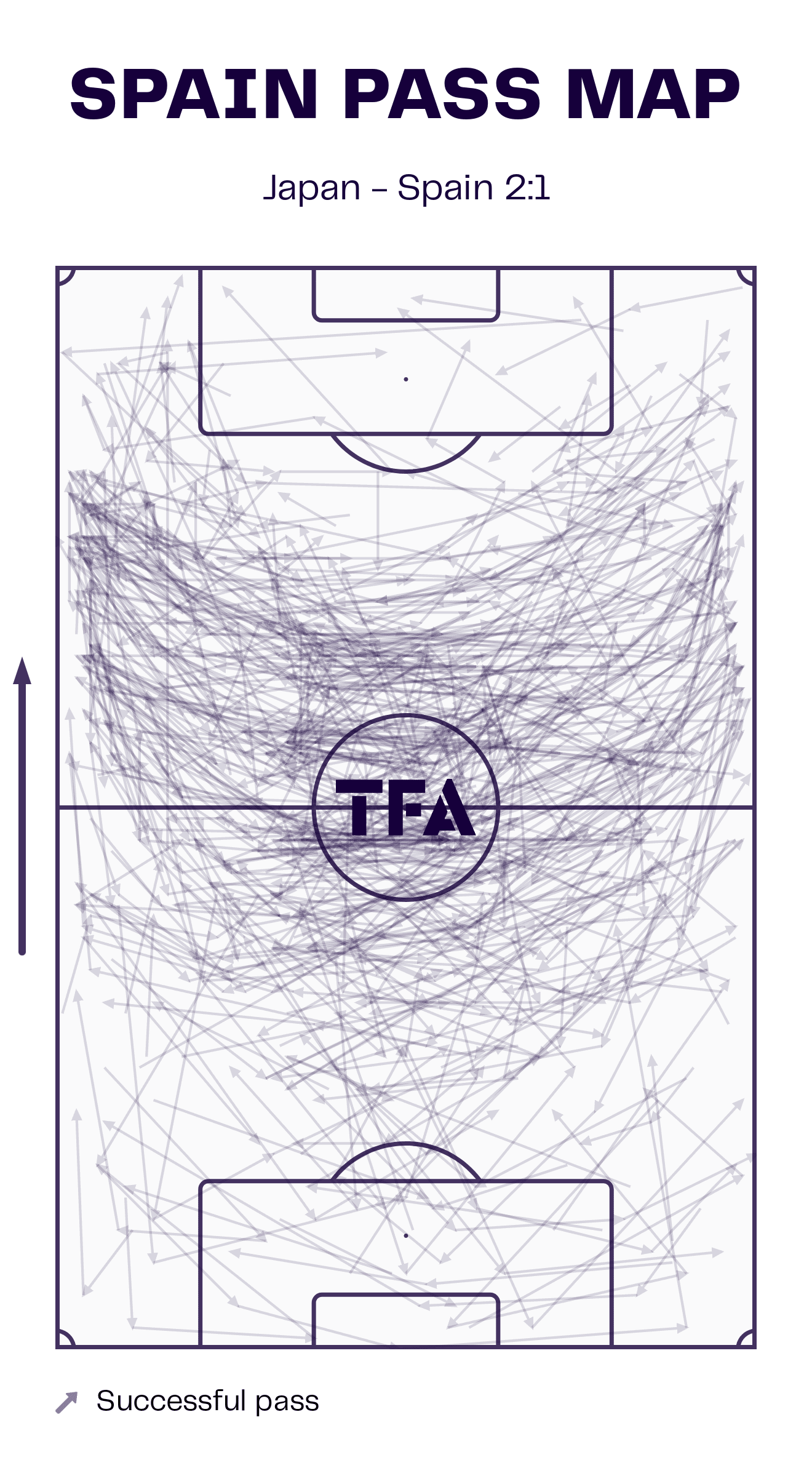

You read that correctly at the beginning of the article — 83.31% of the possession went the losing side’s way in this fixture. Spain played a whopping 1040 passes during the 90-minute contest and finished with 91.25% pass accuracy. Just 18.9% of Spain’s passes were played forward. We saw a lot of patient lateral and backward passing from La Furia Roja in this contest, designed to move Japan’s defensive shape about and create the perfect angles to carve through their opponents and set up good goalscoring opportunities.

Spain’s pass map from this contest is visible in figure 2 and it illustrates how Spain typically settled into long periods of possession around the halfway line, with their centre-backs typically positioned just inside their own half and the full-backs slightly higher, looking to provide positive passing angles along with the midfielders.

You could aptly describe Spain’s approach as quality over quantity in terms of progressive passes and progressive pass receptions. Despite their 83.31% of the ball possession, they managed just 19 touches inside the penalty box, per Wyscout — only seven more than Japan managed.

Spain’s xG, then, was ultimately equal to that of Japan, managing to generate just 1.13 expected goals, a fairly poor return given their quality — but this is a testament to how well Moriyasu’s side executed their game plan; they frustrated Enrique’s men and starved them of clear-cut opportunities for the majority of the contest, limiting them to low-value shots from distance arguably for all but three of their attempts, as figure 3 demonstrates.

Spain’s full-backs sometimes provided a route into midfield or the final third via their positioning and the angles they could create which differed from the angles that the centre-backs enjoyed but first and foremost, Spain wanted their forward passes to move through the centre of the pitch, directly progressing into the most valuable areas they possibly could.

Japan’s well-organised, position-oriented 5-4-1 mid-low block made this difficult as they primarily focused on blocking those passes through the centre and keeping the space between their midfield and defensive lines as compact as possible, which we’ll discuss in greater detail later in this article.

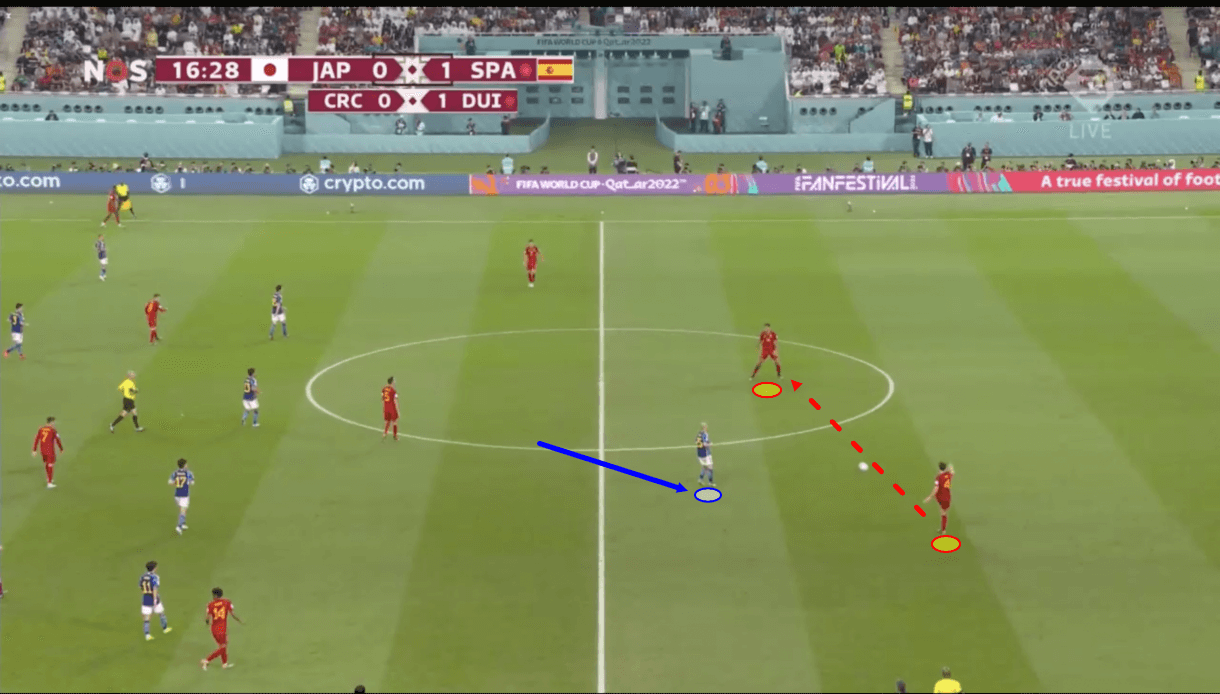

Japan’s centre-forward was tasked with constantly moving from side to side to keep Busquets in his cover shadow as the Spanish moved the ball around the backline to try and create a good forward passing angle. Generally, this required a lot of lateral passing as each part of the Japanese defence knew its role and purpose, so limited their high-quality forward passing opportunities.

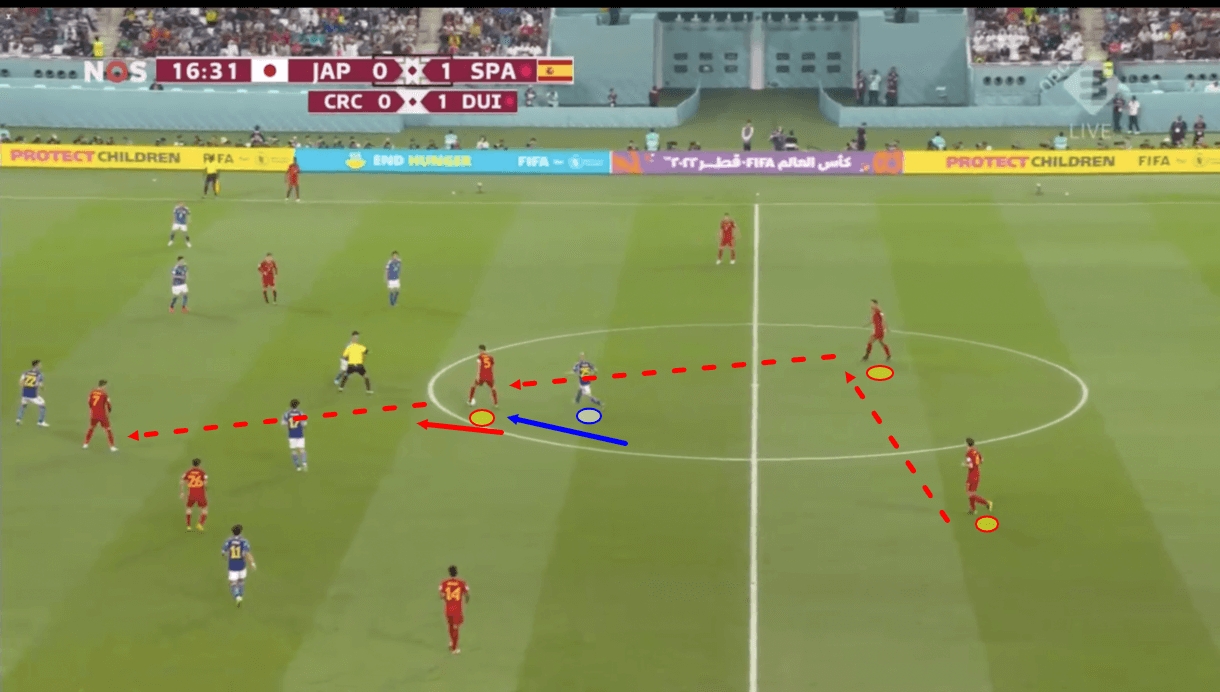

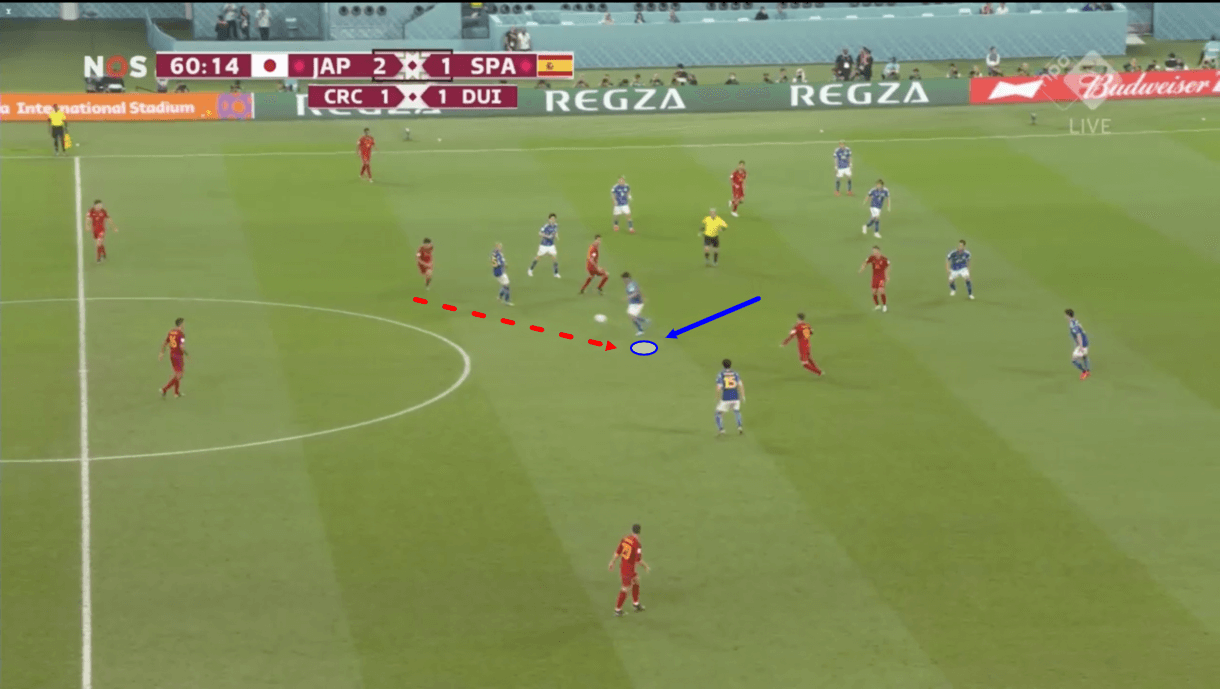

Figures 4-5 show an example of one occasion when Spain managed to get past the Japan forward and into the dangerous outlet at the base of midfield, Busquets. Firstly, they circulated the ball among the backline for some time before the opportunity in figure 5 presented itself.

When Busquets was finally targeted, the midfielder had to be alert and ready to react quickly. He had to have been aware of his surroundings, the positions of Japan’s defenders and the positions of his teammates in order to make the best possible decision when receiving the ball on the half-turn and then playing it forward. Then Spain would finally reach the next level of breaking down this solid defence — finding and exploiting the minimal space available in front of the Asian team’s backline.

However, even reaching that point in the first place was an arduous task which explains why Spain made so many lateral/backward passes; it was a combination of Spain’s desire to find just the best possible forward passing opportunities to exploit the opposition and Japan’s effective defensive tactics that made doing this difficult for Spain, but largely left them with the ball to try and forge the opportunities.

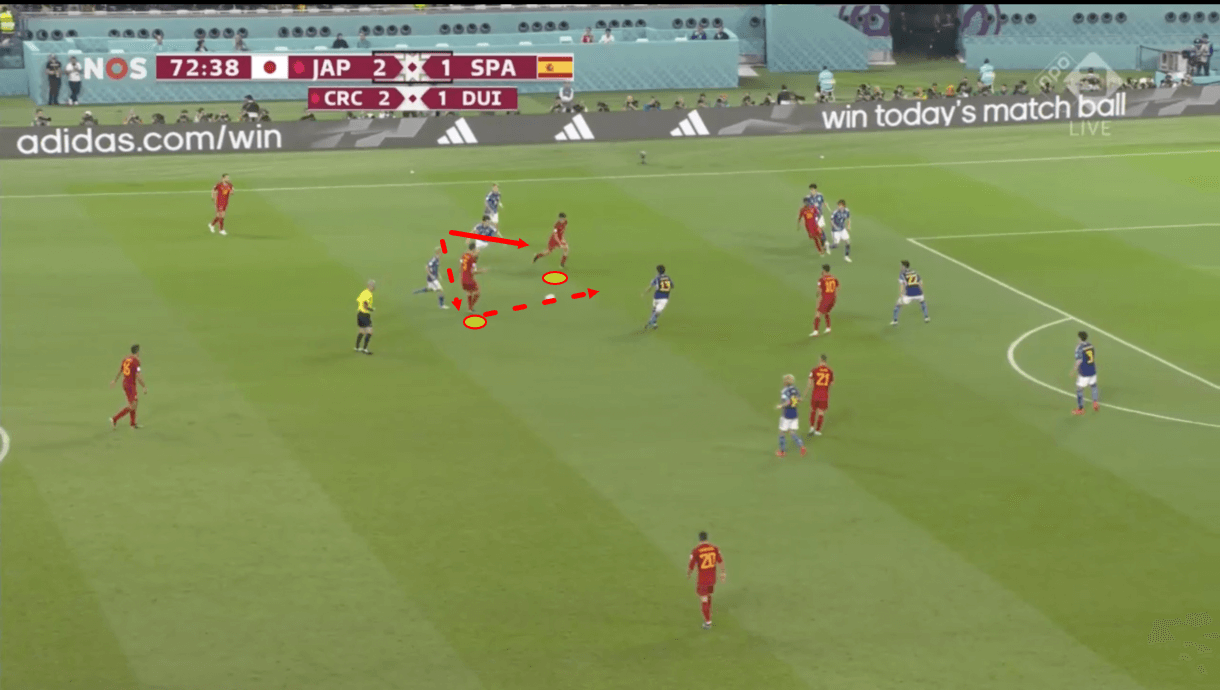

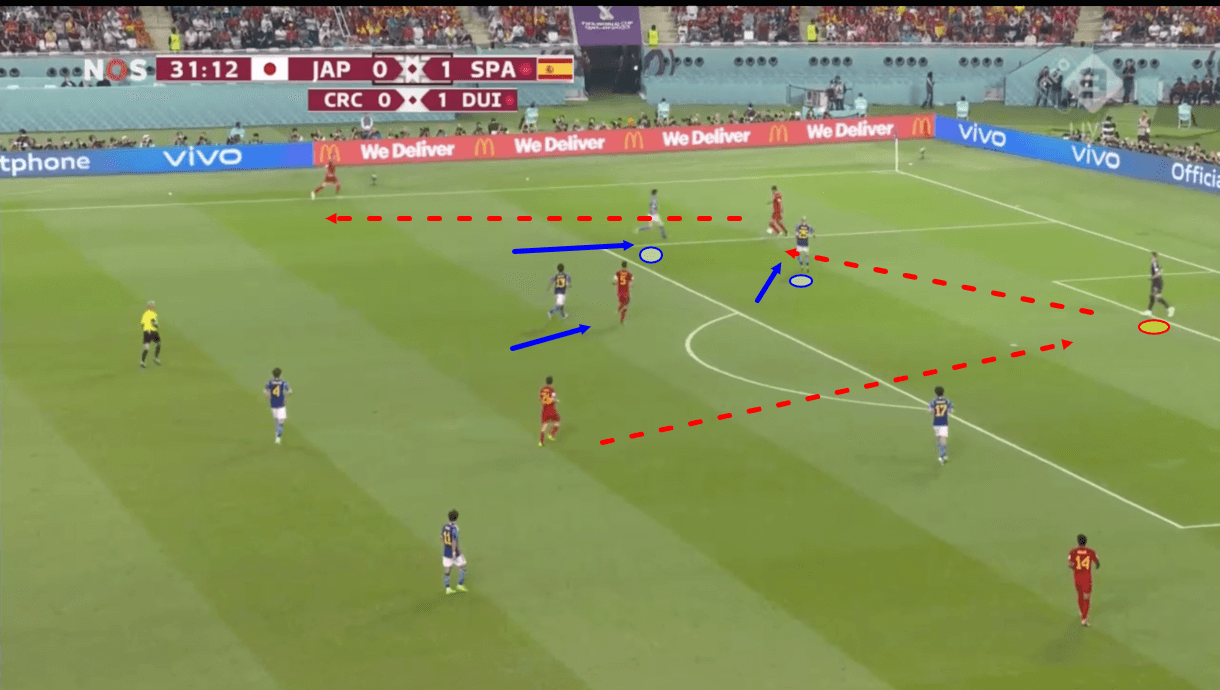

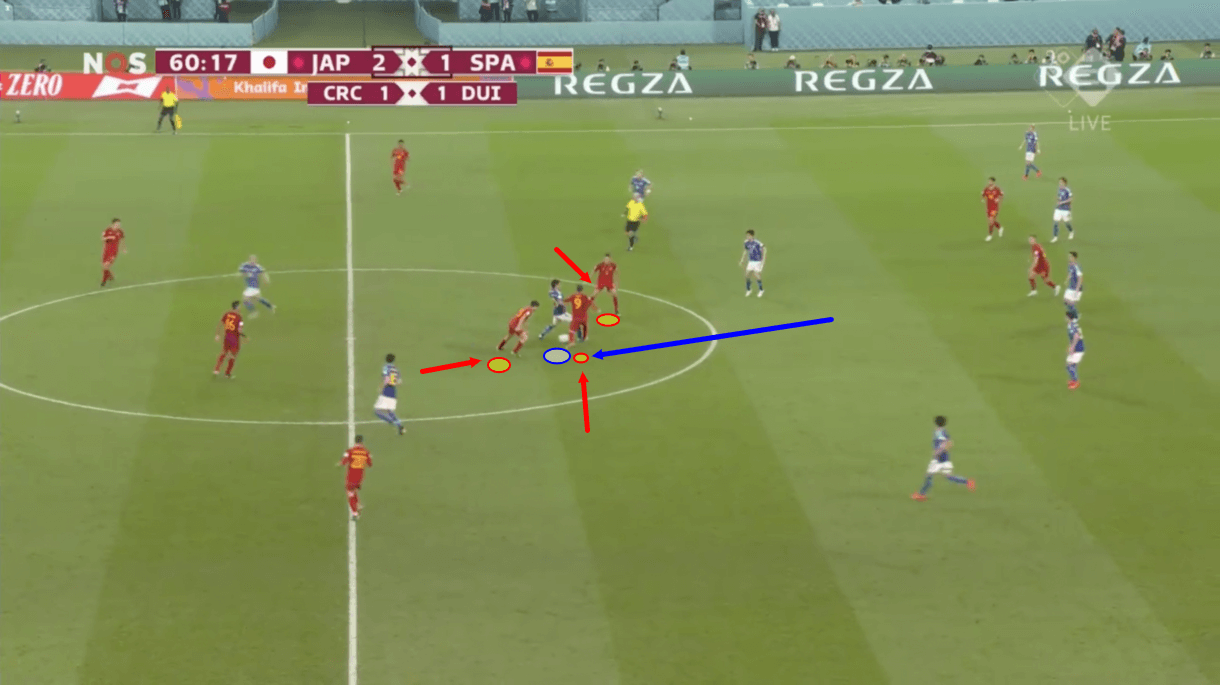

We see an example of one occasion when Spain managed to get in between Japan’s midfield and defensive lines in figures 6-7, as the player receiving the ball here aimed to get onto the end of a one-two, linking up with a more central teammate. They got around the Japanese midfielder excellently via the one-two in figure 6.

However, their well-worked move was compromised when the receiver was then tasked with finding space to get through Japan’s backline, which was just not there. It was like trying to run through a brick wall at times, with Japan’s players positioning themselves so closely together and in such a disciplined fashion that Spain found it very difficult to get through.

Perhaps, more effective movement to pull the Japan defenders about would’ve helped Spain but the movement wasn’t there and on this occasion, in figure 7, we see that Japan ultimately closed in on the ball carrier and regained possession on the edge of their box, preventing a potentially dangerous Spanish penalty area entry.

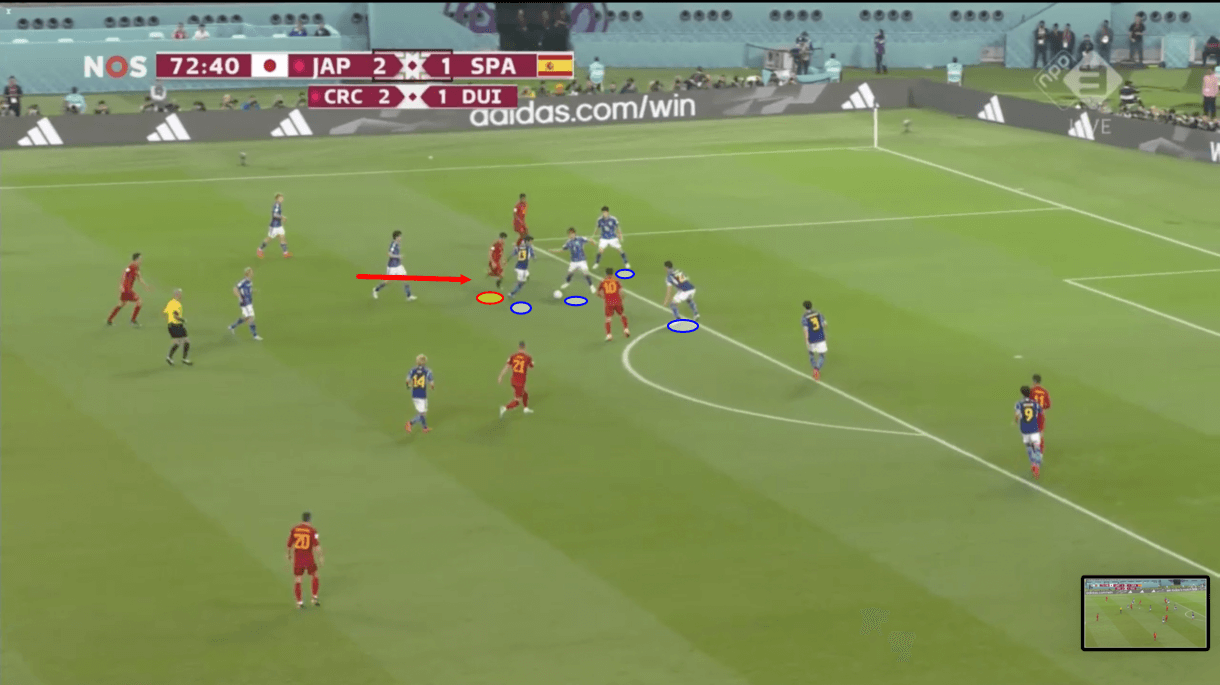

After going one goal up early on, Spain found some joy at times by playing backward passes from midfield to draw the Japanese press out, stretch Moriyasu’s side vertically and thus create some space between the lines. We see an example of Spain effectively employing this strategy in figures 8-9. Firstly, the pass moves backwards from Rodri to Torres and by doing this, Enrique’s ball-dominant side triggered Japan’s pressing to pick up.

Then, when they reached their own box, Spain were able to play around the press, through the full-back who had space out wide and could then target the new space that’s been created in Japan’s vertically stretched shape. This was a very smart and effective strategy from the European side but they failed to capitalise on it when they had the opportunity and after Japan got two quickfire goals in the second half, this strategy was no longer as effective as Japan’s press had far less reason to be so aggressive in this situation.

Japan’s defending

At this point, we can move on to discussing Japan’s defence more specifically and the intricacies of why it was so effective at keeping Spain quiet in terms of good goalscoring chances — some of which we’ve already discussed in the previous section of our analysis.

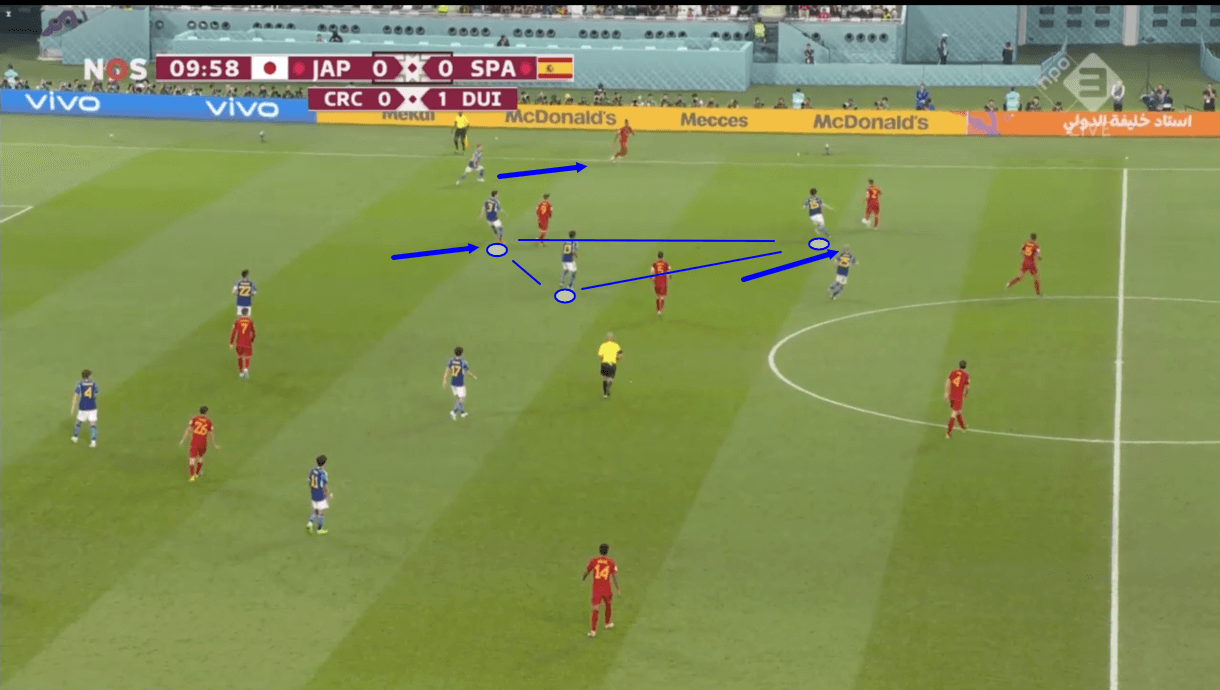

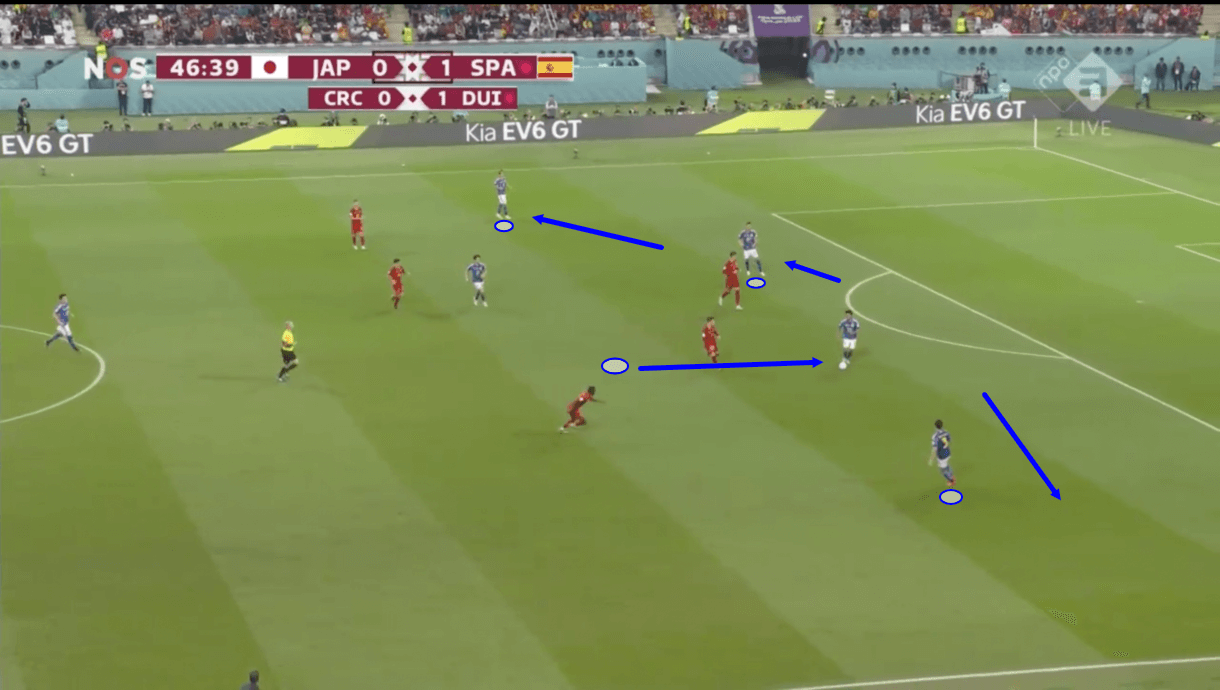

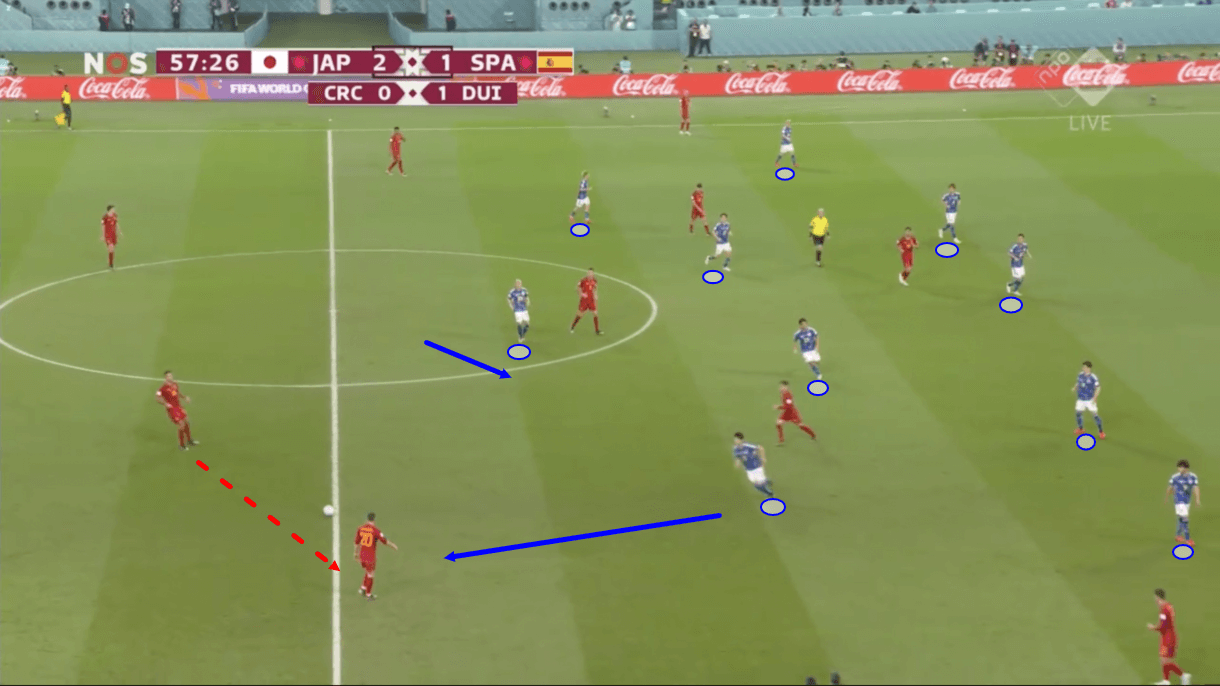

We see a clear example of Japan’s 5-4-1 shape for reference in figure 10. This sight is one that was very common in Thursday’s game, with Spain’s backline parked around the halfway line on the ball, as described previously, and Japan defending in a 5-4-1 mid-low block.

Japan were happy for Spain’s centre-backs to have the ball and generally only picked up their pressing intensity when the ball crossed the halfway line. We see an example of the left midfielder jumping into action as the ball is being played into Japan’s half from Torres to Carvajal, here.

Again, the pressing intensity picked up a bit more when Japan were trailing, especially towards the end of the first half and the very start of the second half, but other than that, Japan were rather passive until play entered their half throughout this game and this discipline, organisation and compactness were what frustrated Spain as they looked to progress through the tight central areas.

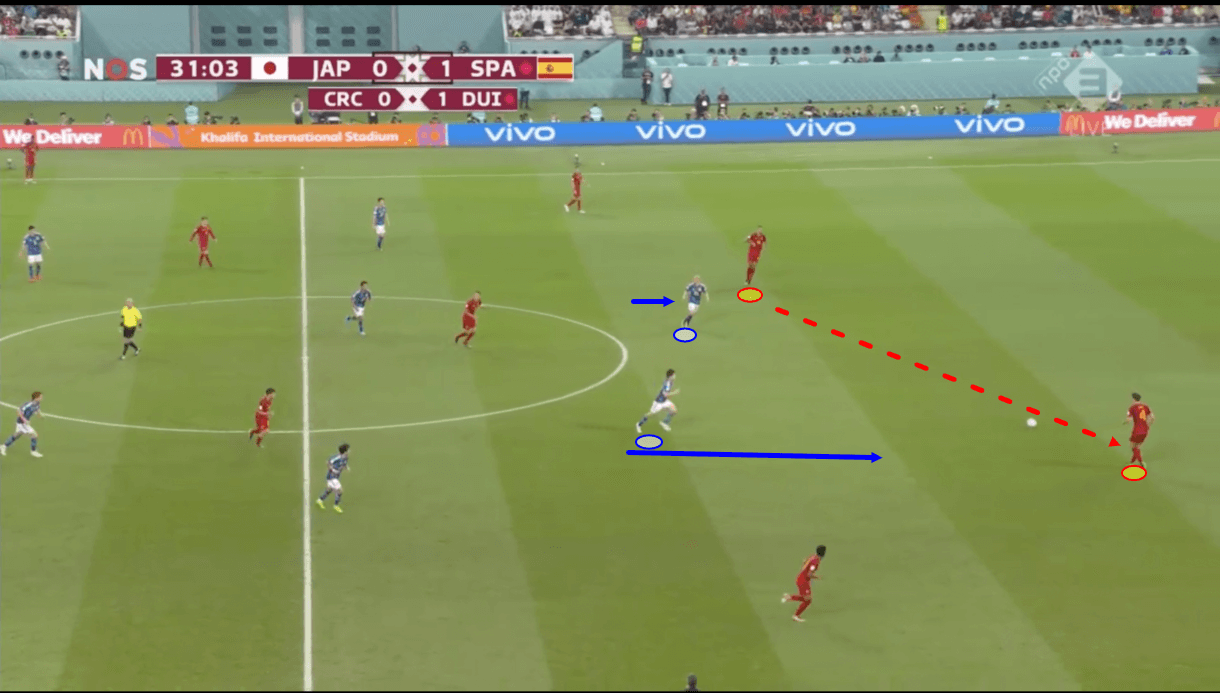

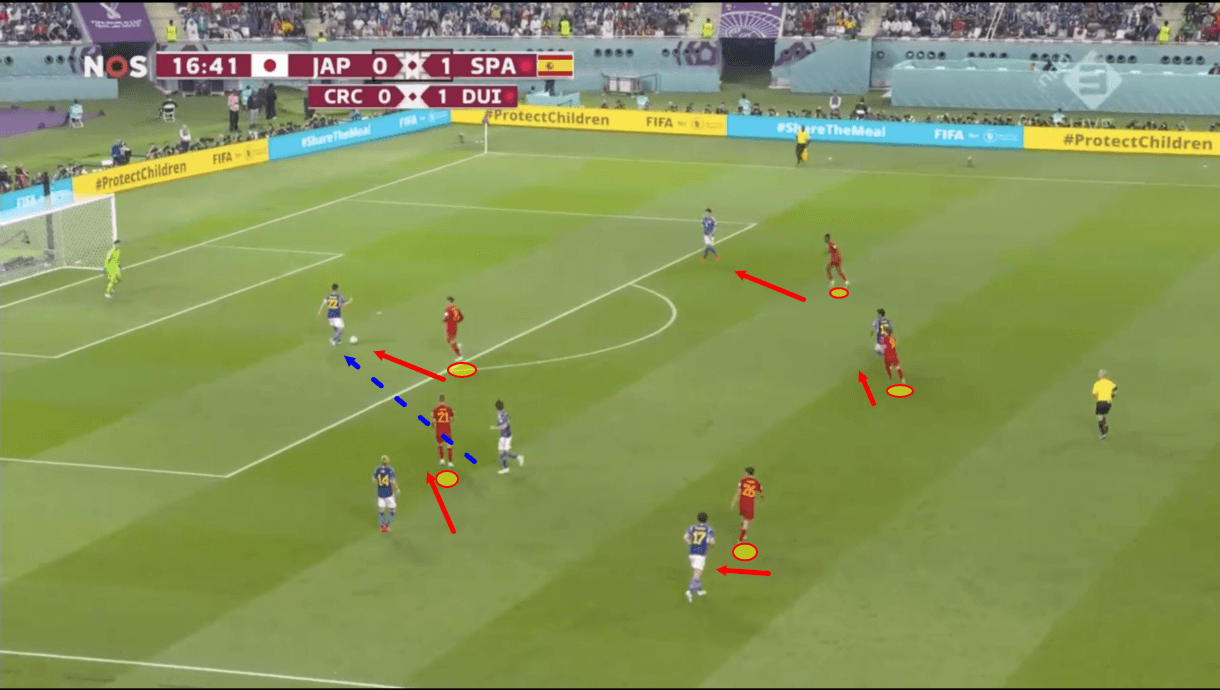

Japan’s wide midfielder, central midfielder and wide centre-back would form something of a triangular cage around the Spanish half-spaces, trapping the Spanish players hoping to exploit these dangerous areas inside and making them unattractive or just impossible-to-reach passing options.

Figure 11 shows an example of this. As the Spanish right-back gets on the ball, Japan’s near-wide midfielder steps out to him. This could create some space for the player in the half-space but the wide midfielder’s step is coordinated well with the wide centre-back stepping up simultaneously to keep the Spanish player in the half-space a bit more under control and difficult to play to for La Furia Roja.

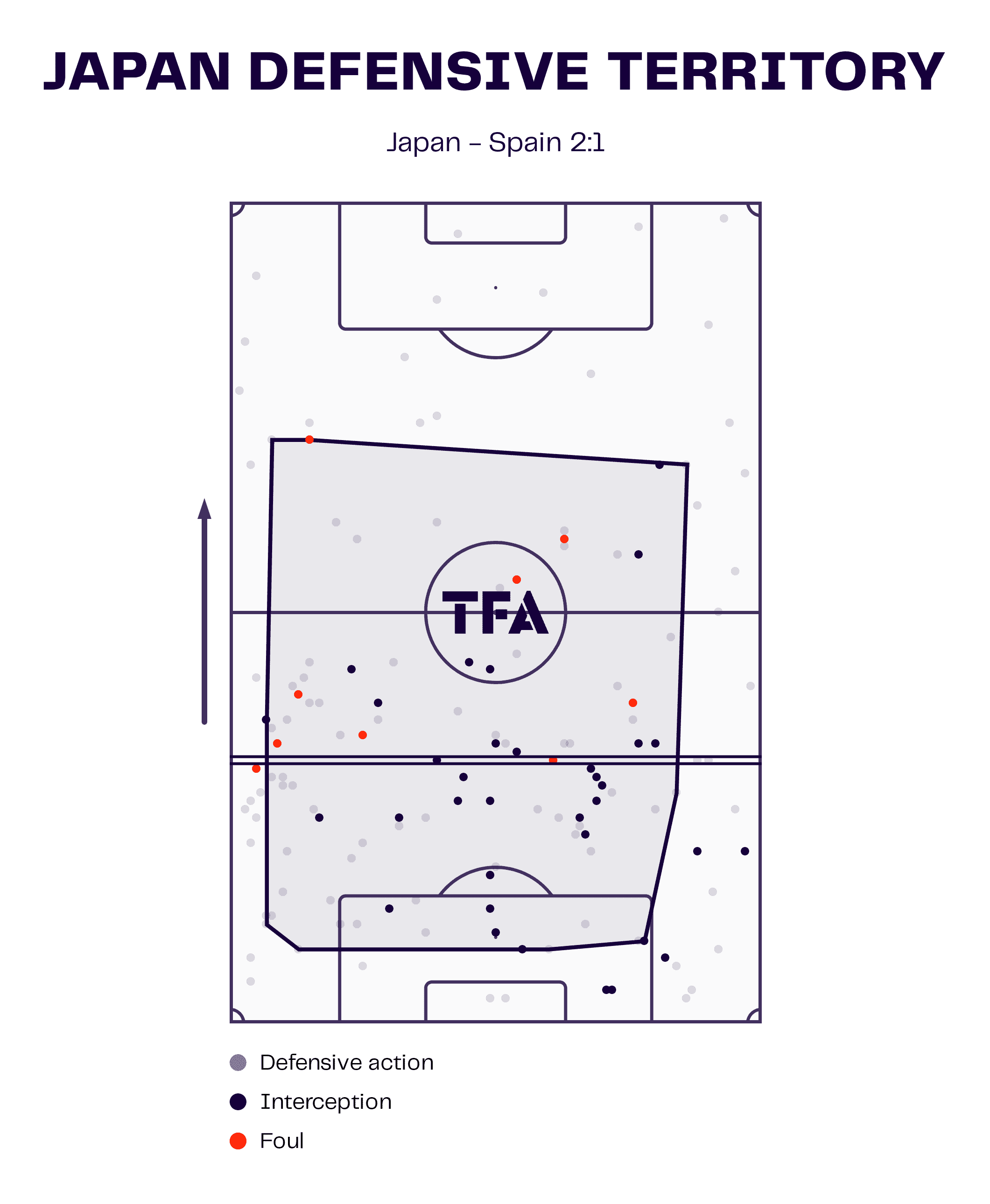

Japan controlled these areas — and all of the central areas just in front of their box and the final third — very well, making many of their successful defensive actions, interceptions in particular, in these positions, as figure 12 also highlights. This can largely be attributed to Japan’s organisation and coordination; again, each part of their defensive system knew its role and performed it as part of a well-prepared unit on Thursday which limited Spain’s penalty box touches significantly despite their quality and ball dominance.

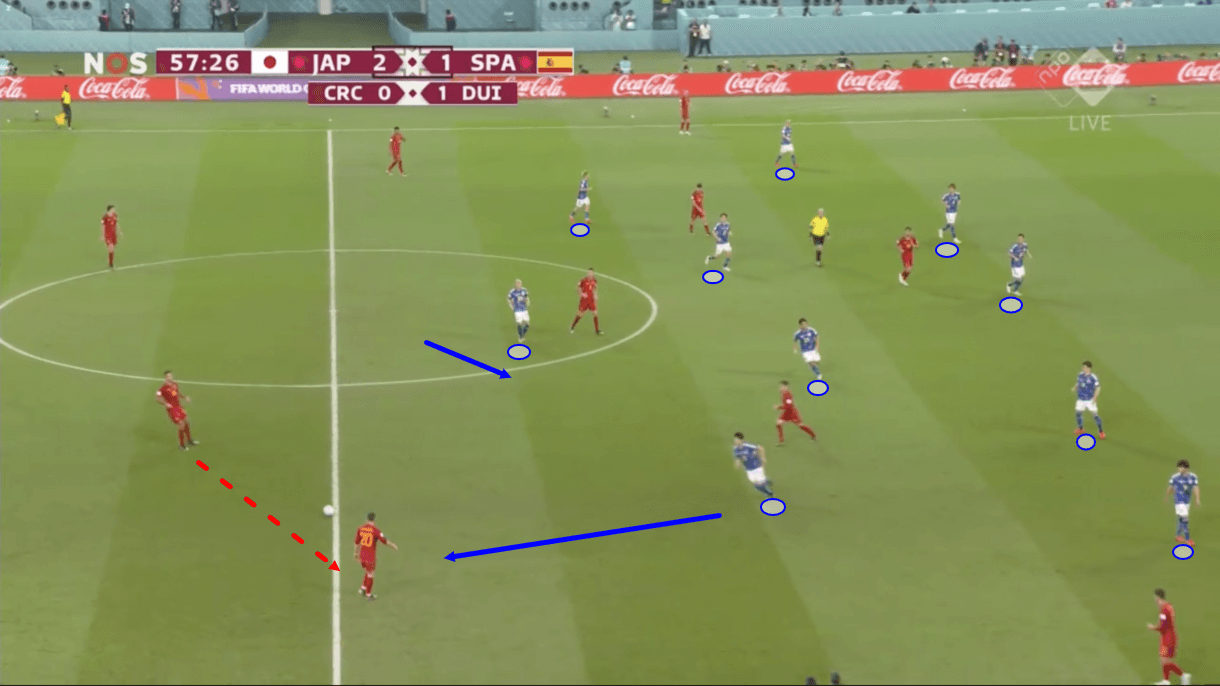

As we mentioned, Japan operated in a far more intense and on-the-front-foot fashion for periods of Thursday’s game, in particular towards the end of the first half and the very start of the second half. This period saw Japan look like more of a 3-4-3 than a 5-4-1, as the wide midfielders spent more time higher alongside the centre-forward and the wing-backs thus advanced to operate as the new wide midfielders.

Japan are an extremely effective side in transitions and they love to play without the ball but inside the final third, which we see an example of in figure 13, which is actually the build-up to Japan’s first goal which came directly as a result of their high press.

The Samurai Blue forced a dangerous high turnover as Spain tried to play out from the back and capitalised on the resulting opportunity. The strike itself was very well hit and one for the goalscorer to be proud of, but the press that created the opportunity is what the team and Moriyasu can cherish the most. Japan had plenty of opportunities to press high when they wanted to as a result of Spain’s playing style and in the end, it was a stylistic match that suited them well, as a highly effective transitional side.

Japan’s attacking

This helps us to transition nicely into Japan’s attack ourselves. Indeed, The Samurai Blue enjoyed just 16.69% of the ball in this one.

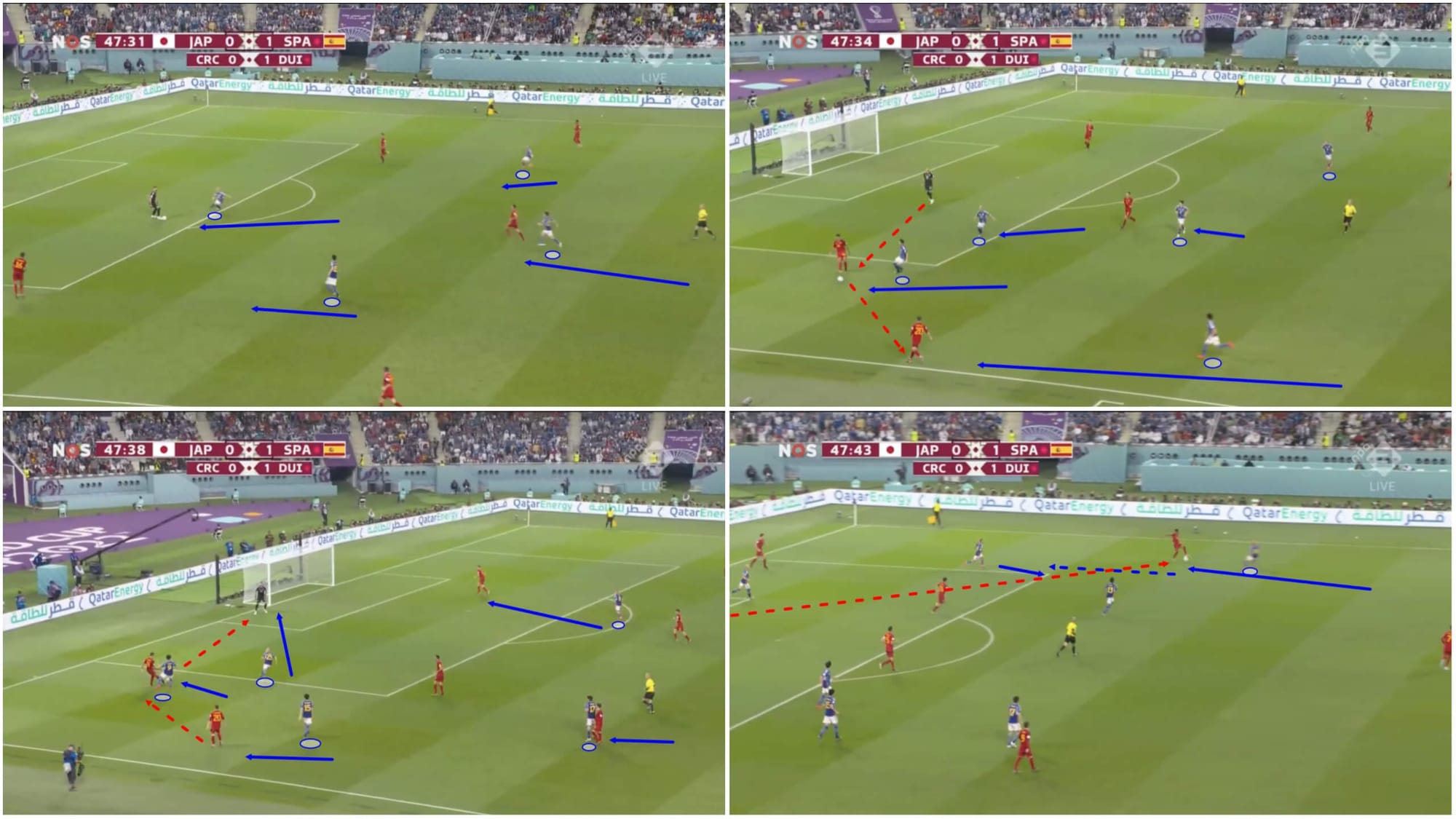

However, again, Japan played more on the front foot at parts and they did enjoy a couple of impressive possessions at the beginning of the second half when they demonstrated lots of bravery and willingness to take the game to La Furia Roja in order to get back into it.

Again, Japan operated in more of a 3-4-3 for this portion of the game, and they built up with a 3-2 base structure, though that base structure quickly turned into a 4-1, as the backline stretched allowing Morita to drop, slot into one of the centre-back positions and use the extra space here, away from Spain’s aggressive press, to pull the strings in the build-up from a deeper position than you’d typically find the midfielder.

Meanwhile, Japan’s wing-backs sat very high alongside the midfielders, offering long passing options to the deeper players out wide where they could link up with the wingers and quickly progress via the wide areas.

Japan’s pass map is a stark contrast to Spain’s from figure 2. While Spain played just 18.9% of their passes forward, 36.8% of Japan’s 212 passes were forward passes, highlighting the very different approaches that these two sides took into this game.

We see that many of Japan’s passes moved outward towards the wings, especially inside the final third — this was deliberate as Moriyasu brought his side into this game looking to exploit their pace in wide areas, get in behind Spain’s defence, progress to the byline and cut the ball back into good goalscoring positions from there. Japan’s second goal came very soon after the first from an attack like this.

Spain themselves took a very aggressive and well-organised press into this game. Another big reason for their possession dominance was the fact that they were so good at shutting down Japan’s attacks/counterattacks quickly via their pressing/counterpressing which Enrique can take some positives from. Spain were generally very good at regaining the ball quickly and shutting down Japan’s attacks before they progressed to a very threatening point.

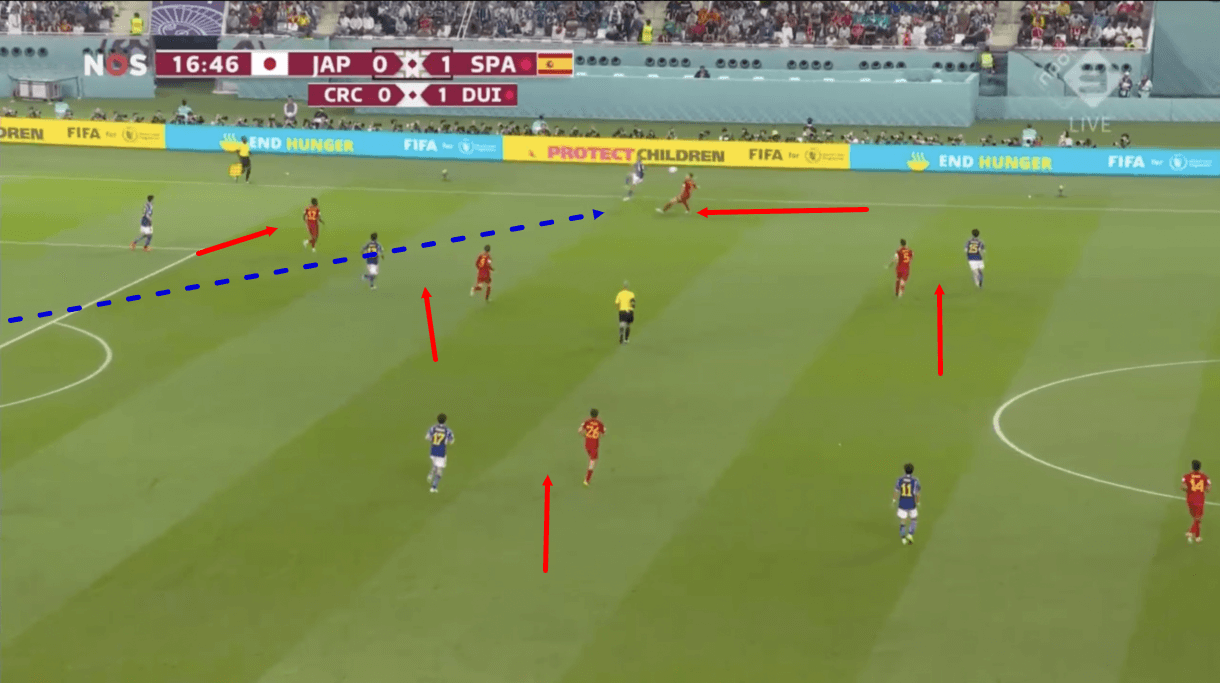

We see an example of one such attack in figures 16-17. Firstly, Spain got tight to all the short passing options as they forced their opponents to move backwards.

This forced Japan to play a riskier long ball out to the wing to try and find a free man, which ended up getting intercepted by Spain’s right-back, allowing La Furia Roja to end this attack before it got started and regain possession in a nice position for their own subsequent counterattack.

Spain’s marking and pressing energy was typically on point versus Japan, as this example shows. Just as Japan made Spain’s offensive gameplan difficult to pull off with their defensive tactics, so too did Spain make Japan’s offensive gameplan difficult to execute thanks to their defensive tactics.

Figures 18-19 show an example of Spain’s counterpress quickly shutting down Japan’s attempted counterattack; the Spaniards’ quick reactions and organisation were key to pulling off their effective counterpress. Firstly, we see Japan’s midfielder intercepting an attempted Spanish pass through the centre of the pitch in figure 18, again demonstrating how Japan’s block shut down Spain’s attempts to cut through the centre of their defensive shape.

The ball winner attempted to carry the ball forward, into a good position from where he could potentially play a through ball for a Japanese runner ahead of him. However, the space he had to roam into was quickly cut down by Spain’s midfielders as they snapped back into a compact defensive triangle very quickly, closing in around the ball carrier and shutting the Japanese counterattack down within seconds — a great example of how Enrique prepared his team to defend in this competition — aggressively, with the aim of getting back on the ball as quickly as possible and as far forward as possible.

These defensive tactics and their largely successful execution made it difficult for Japan to enjoy many effective counterattacks but thankfully, for Moriyasu’s men, they managed to pull off just enough successful counterattacks to get the job done on Thursday and finish as winners of Group E.

Conclusion

To conclude our tactical analysis of Spain versus Japan, it’s clear that both teams did well enough defensively to stifle the other team’s offensive attempts and counteract their offensive styles.

There was a lot to observe in this contest from a tactical perspective, with both teams matching up well stylistically for an interesting encounter that ultimately fell Japan’s way. We hope our tactical analysis has highlighted the key tactical aspects of this clash and both teams’ respective performances.

Comments