With an eye on the decisive match of the quarterfinals in South Africa 2010, where Luis Suárez conceded a penalty after a handball saved his team from conceding a goal, a missed penalty by Asamoah Gyan and then an agonizing penalty shootout, Uruguay and Ghana met again in a life or death match, where victory could mean qualifying for the Round of 16 for each of them. Something that the South Americans had done from 2010 to 2018, and Ghana hasn’t done it since that World Cup in South Africa.

After two games with a 2-0 defeat and a 0-0 draw, Diego Alonso’s men faced this match with the idea that winning was the only way to qualify, however, they did not count on the surprising victory of South Korea, which for a goal difference knocked them out in the last minutes of the match.

Ghana, for their part, played a rather poor match, which was not reminiscent of their 3-2 victory against South Korea, nor their performance in a 2-3 defeat against Portugal where they deserved much more.

With so much to play for, Uruguay did their best and actually won the match 2-0 with two goals from Giorgian de Arrascaeta, which was a brilliant plus for them, but it wasn’t enough as they had to score one more goal to qualify.

In this tactical analysis, we dive into the tactics of both teams in the form of analysis and see how Uruguay got the better of Ghana despite ultimately being eliminated from the competition.

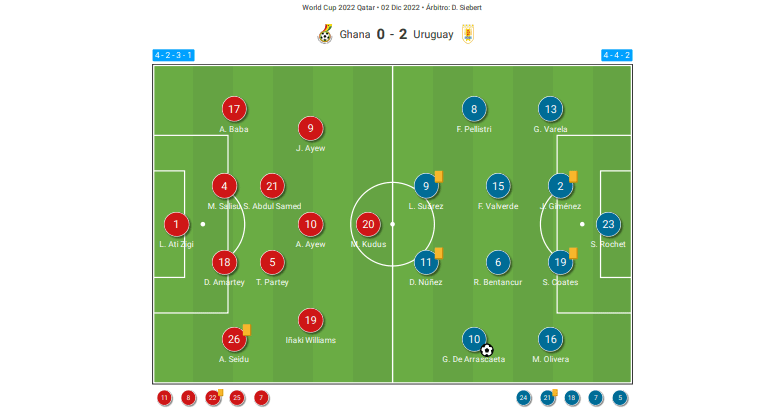

Lineups

Uruguay set up a 4-4-2 with Sergio Rochet on goal, Mathías Olivera as a left-back, José María Giménez and Sebastián Coates through the middle of the defence and Guillermo Varela over the right. The midfield was composed of Real Madrid star Federico Valverde and Rodrigo Bentancur, with Facundo Pellistri and Giorgian de Arrascaeta as inverted wingers. Luis Suárez and Darwin Nuñez concluded the starting XI with the striker-partnership.

Ghana looked to play in a 4-2-3-1 with Lawrence Ati-Zigi on goal, Alidu Seidu as a right-back, Mohammed Salisu and Daniel Amartey the centre-backs, and Baba Rahman on the left. Thomas Partey and Abdul Samed were the midfielders on the double-pivot, with Mohammed Kudus as the #10. The attack was formed by Jordan Ayew, André Ayew and Iñaki Williams.

Giorgian de Arrascaeta’s key role and Uruguay back to their basics

Uruguay seems to have gone back to basics very late in the competition. Diego Alonso had set up extremely thick and tactically flat setups in the first two matches against South Korea and Portugal, both with the ball and also extremely passive defending, something that was not a clear and well-known image of what was the former team, led by Óscar Tábarez, the coach who gave them a stronger identity. That created fear around them for many teams in South America and even Europe when they faced each other in international tournaments.

With a change of formation to 4-4-2, the entry of a player like Giorgian de Arrascaeta, something that many had asked Alonso for, was key for the Uruguayans to be able to offer a great performance in their last group-stage match. against Ghana.

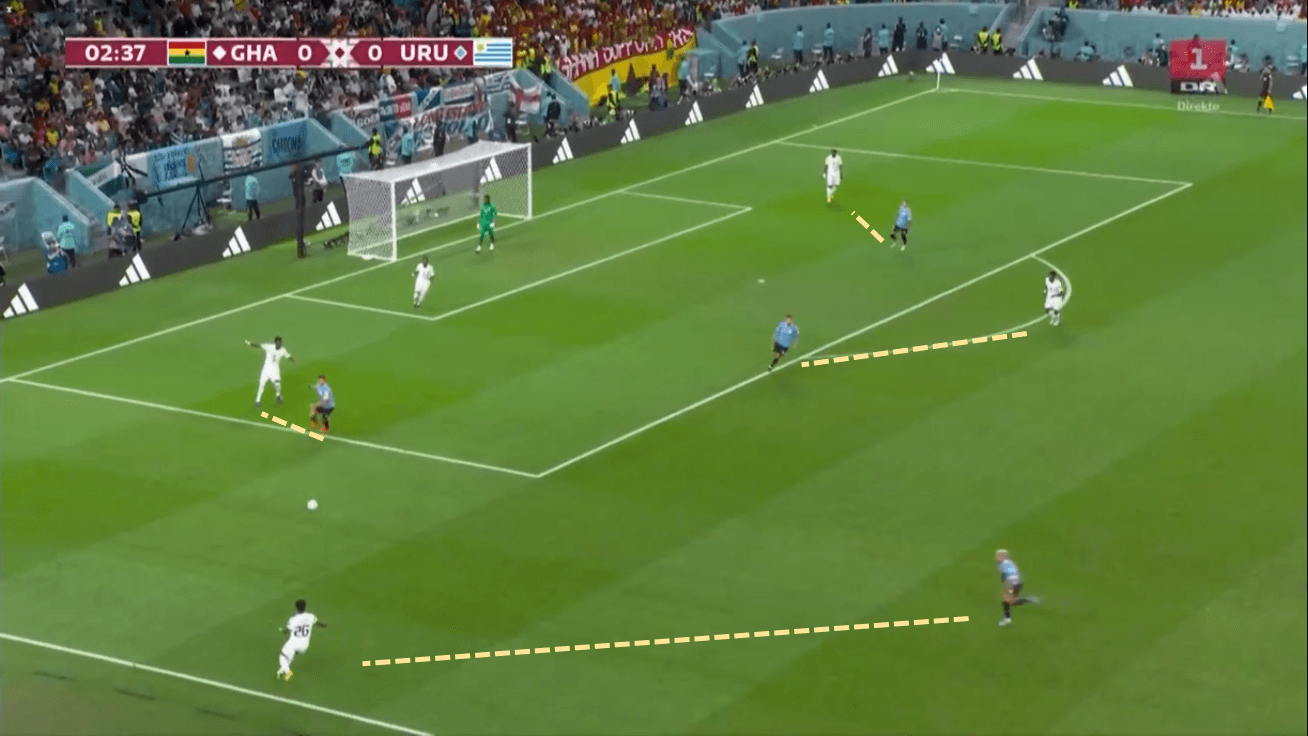

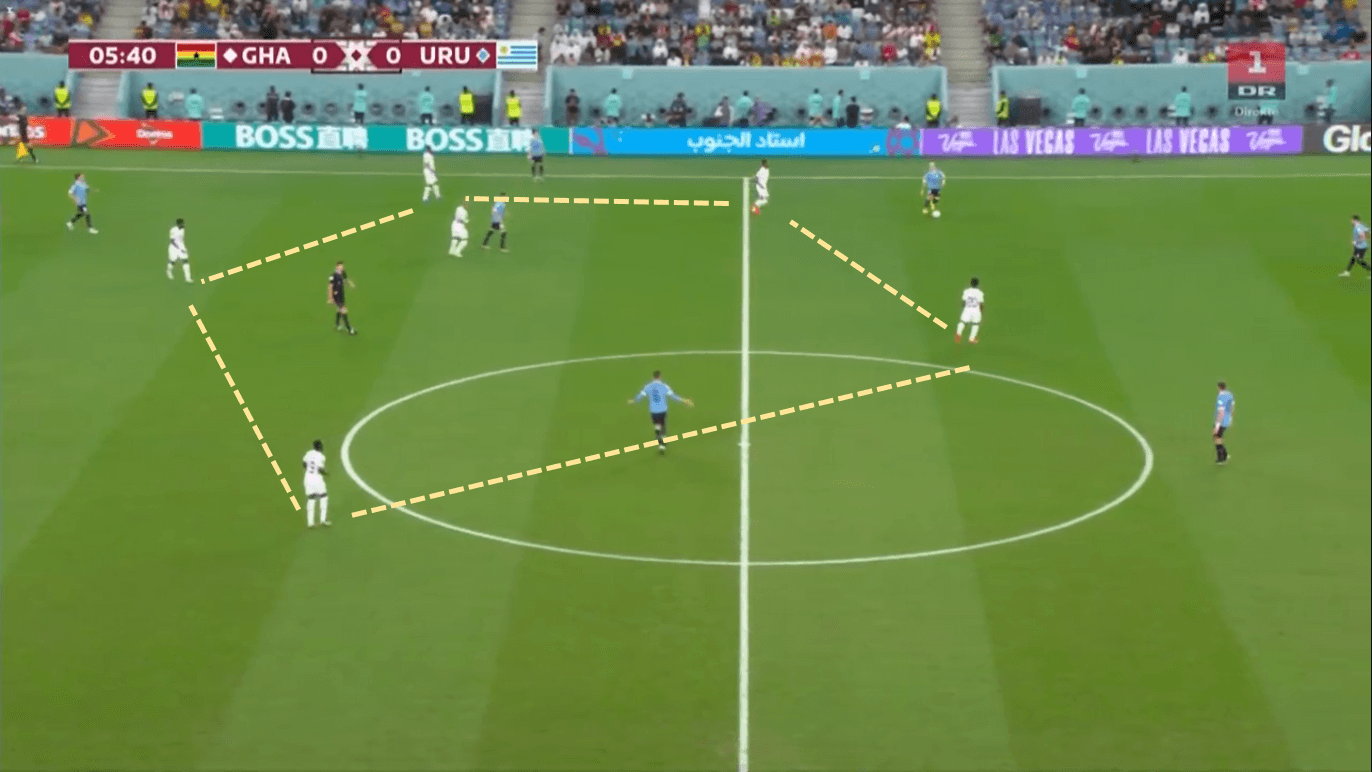

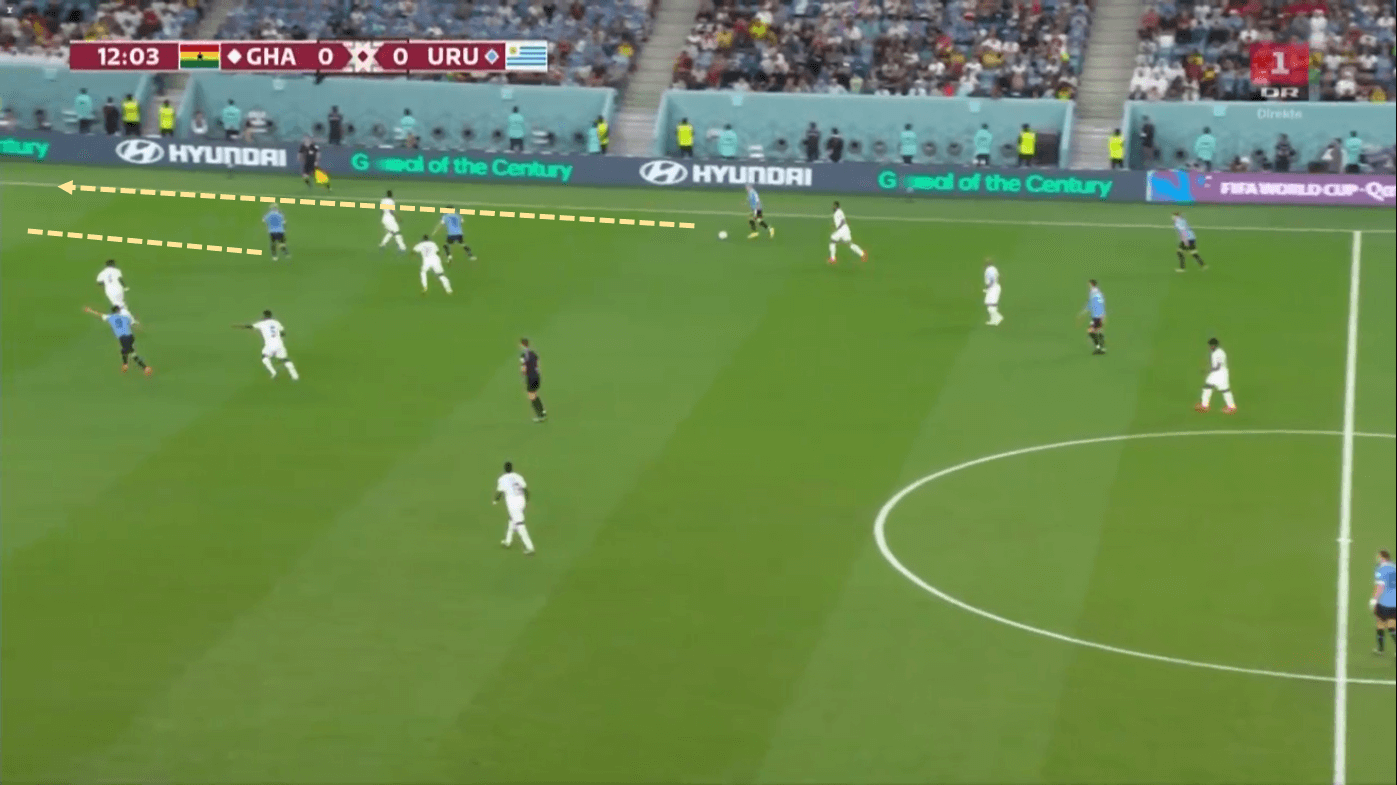

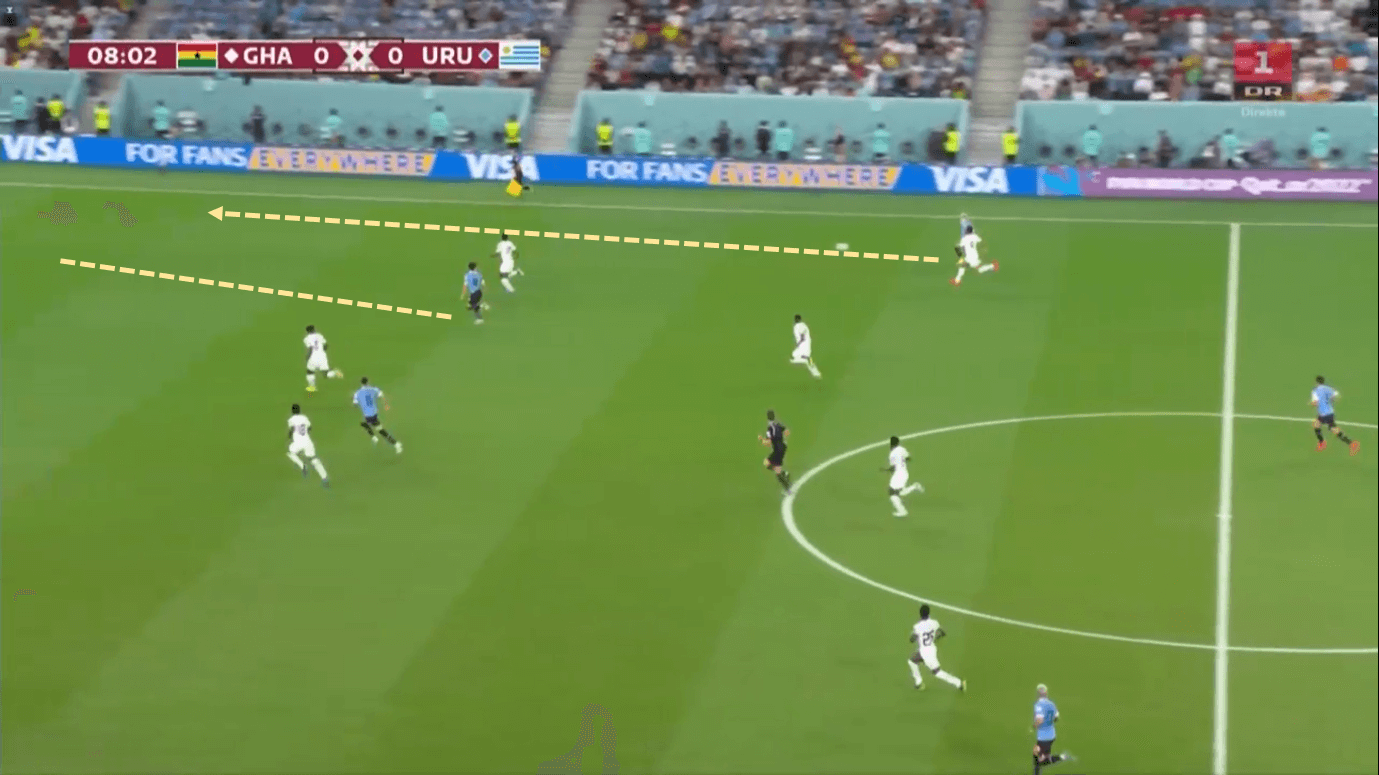

Uruguay first sought to raise their block and position itself in the third of Ghana constantly. The high pressure was clear. Darwin and Suárez pressed the African central defenders close, while Arrascaeta and Pellistri pressed the full-backs, who were far away, exerting the pressure trap there.

Even Federico Valverde and Rodrigo Bentancur raised their position a lot, blocking passes with the midfielders and the double pivot of Otto Addo’s team who did not find many solutions in the first game, much less in the first half of the game.

Uruguay generated a fairly high and risky system that worked for them, as well as a very effective counter-pressure thanks to the attitude of their players who, after each lost ball, performed recovery runs with an absolutely tremendous effort and stamina. Diego Alonso wanted to attack the build-up of Ghana with Rodrigo Bentancur going high enough to cover the pass option with a pivot.

If the ball was played to Ghana’s right side, de Arrascaeta would stay wide pressing the full-back, while Pellistri, the winger on the other side of the pitch, would drop down the middle with Federico Valverde to provide balance and balance there.

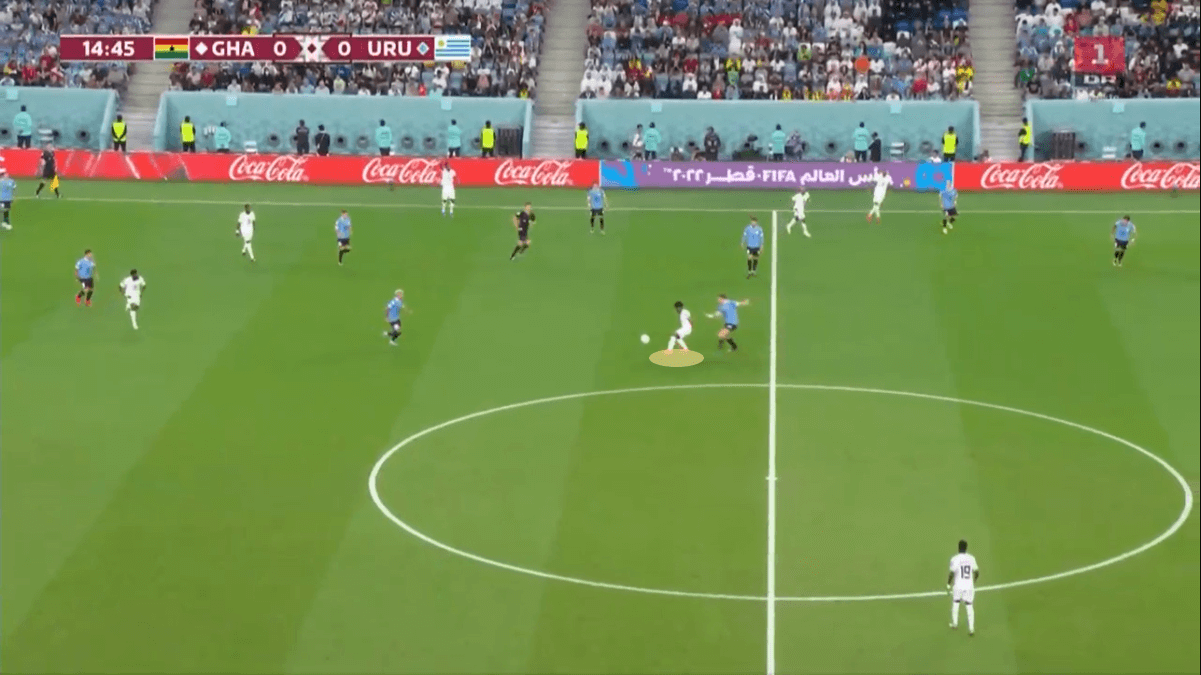

This was a simple but quite successful system for Uruguay that during the whole game did not allow Ghana to connect passes between their front line and the midfielders. In fact, the only way they found to progress, especially in the first half, was from Mohammed Kudus’ receptions and spins. The Ajax player was one of the best players in the group stage, thanks to his scoring contribution but also what he offered in other aspects of the pitch. Neither Iñaki Williams, Jordan nor André Ayew were that active and reading the game that well. The Ayew brothers were even subbed off at half-time because of their poor performance.

He seemed to be the only one who understood the context of Ghana on the pitch, seeking to gather passes to attack quickly behind Uruguay’s back, something he did constantly and even dared to shoot from a long distance many times, which created danger for Alonso’s team.

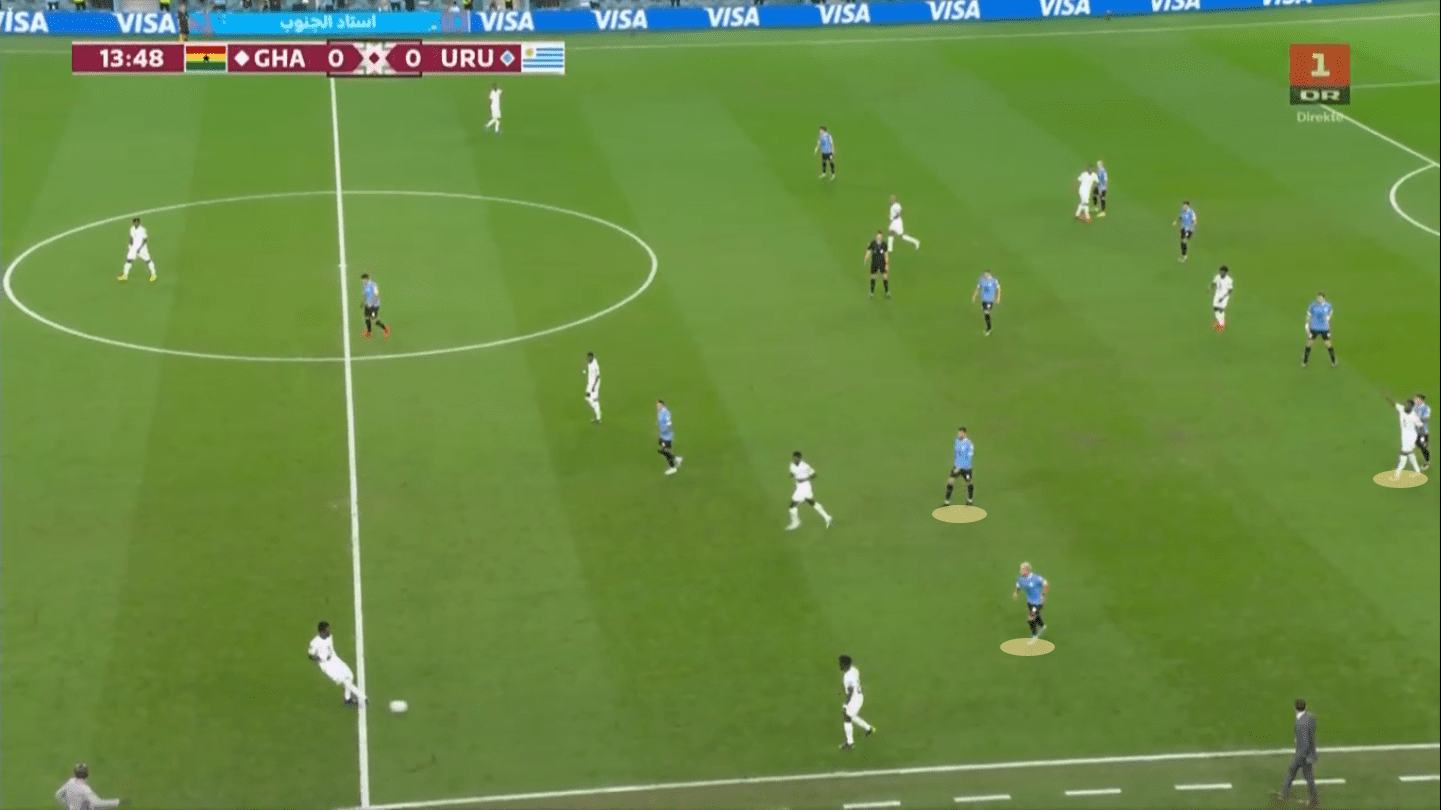

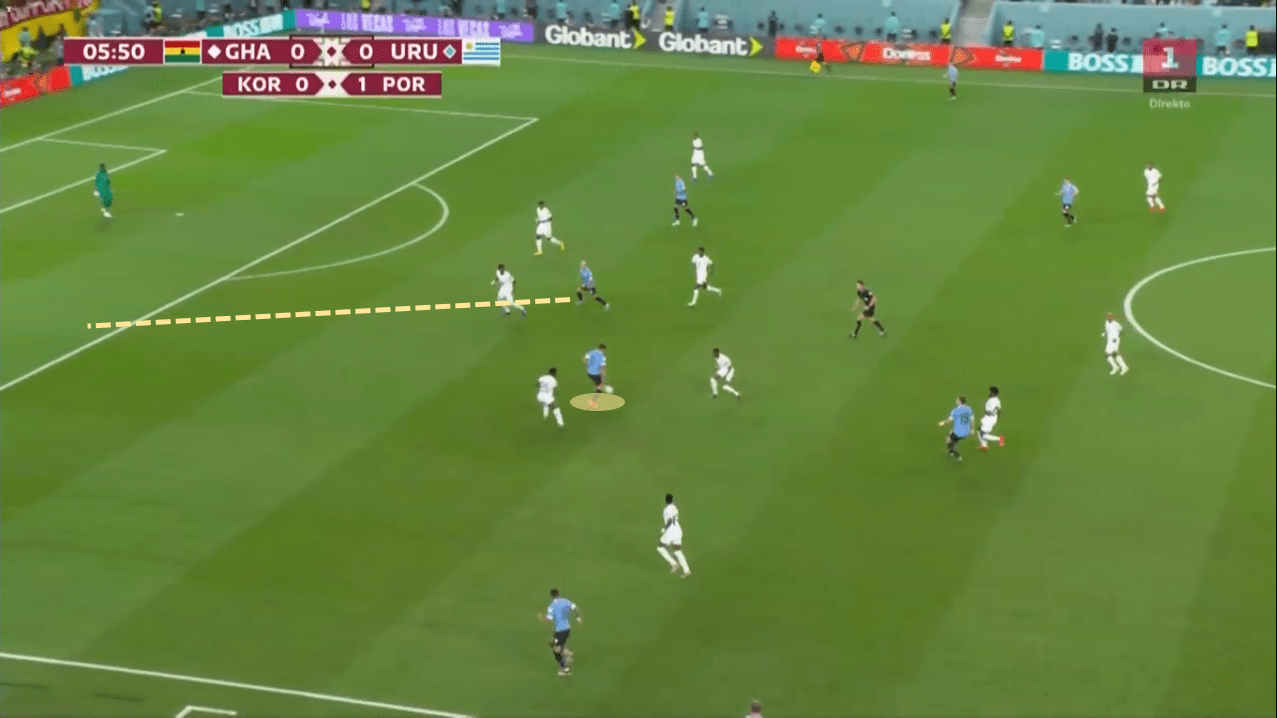

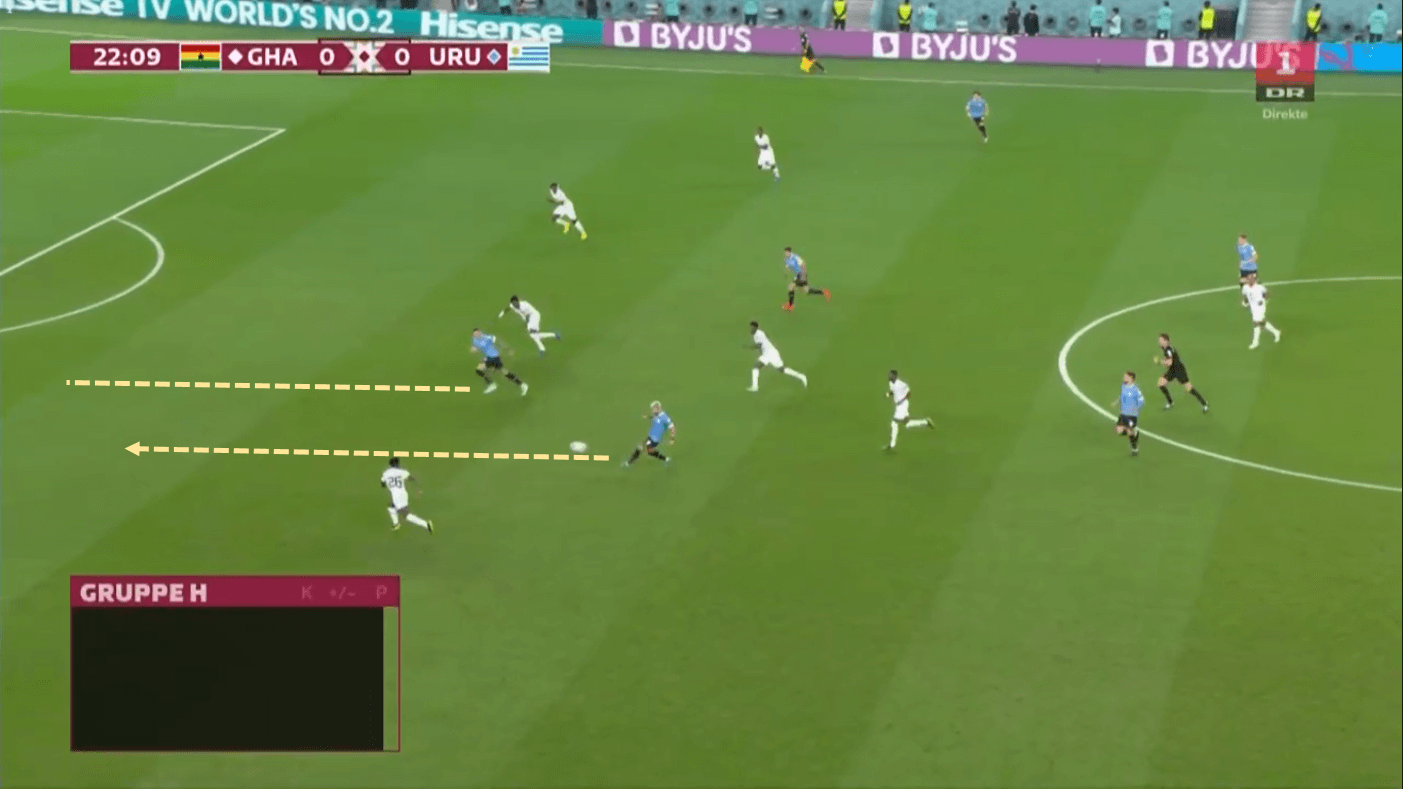

When Ghana at certain times forced Uruguay to drop their positioning to a deeper block, Alonso’s men sought to close the outside lanes, which with the speed and technique of Addo’s players could hurt them. Instead of overloading inside, one of the midfielders left the central zone to rigidly unite the lines with the winger who was marking on the outside. While behind them the Uruguayan full-back marked man-on-man the Ghanaian winger who could neither receive nor outside or in the inner channels.

One of Uruguay’s first tactical moves in the match was to visualize how they sought to accumulate centrally, with players with more inverted roles such as Pellistir or Arrascaeta, plus the presence of Valverde and Bentancur and Suárez’s drops between the lines, to free up the players occupying the wide channels of the field.

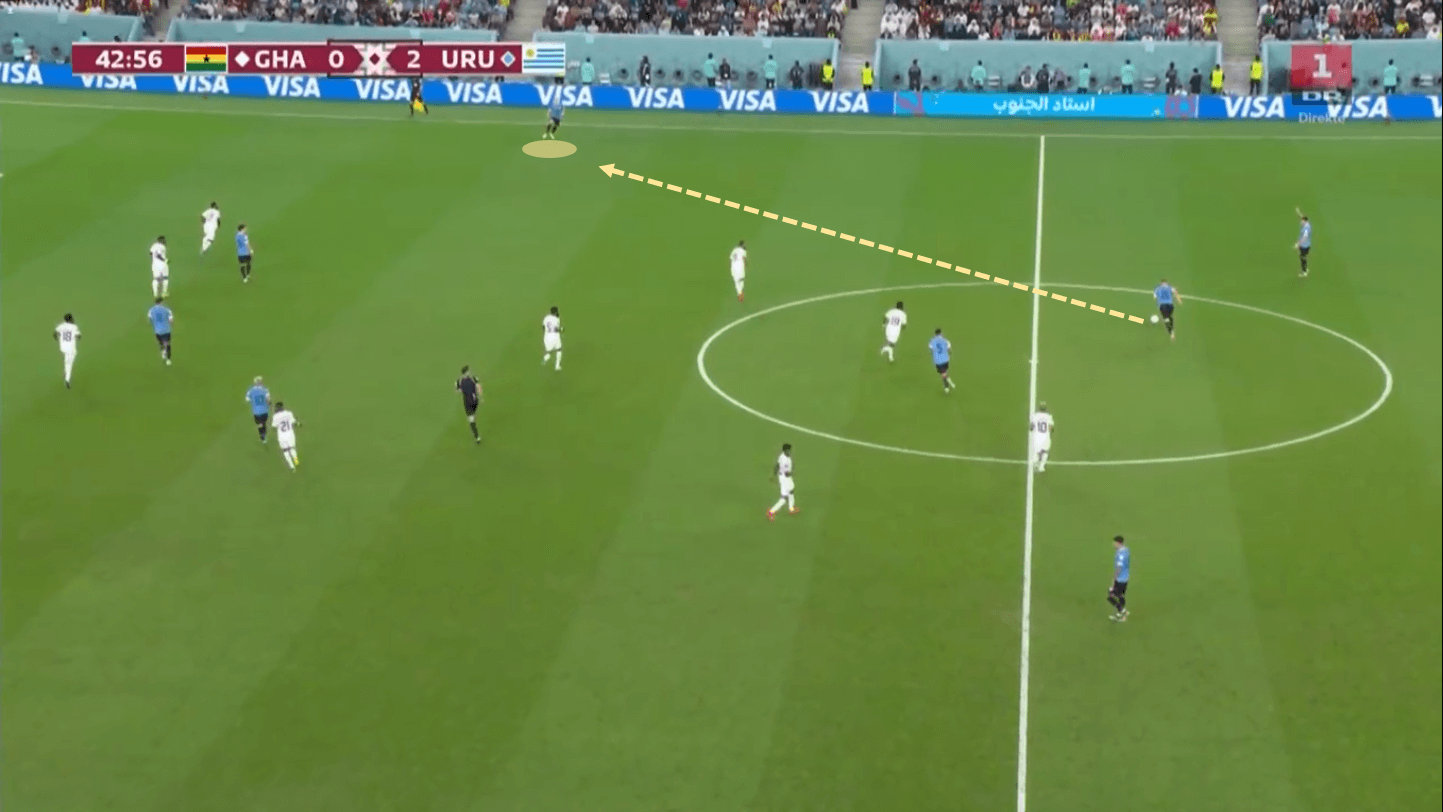

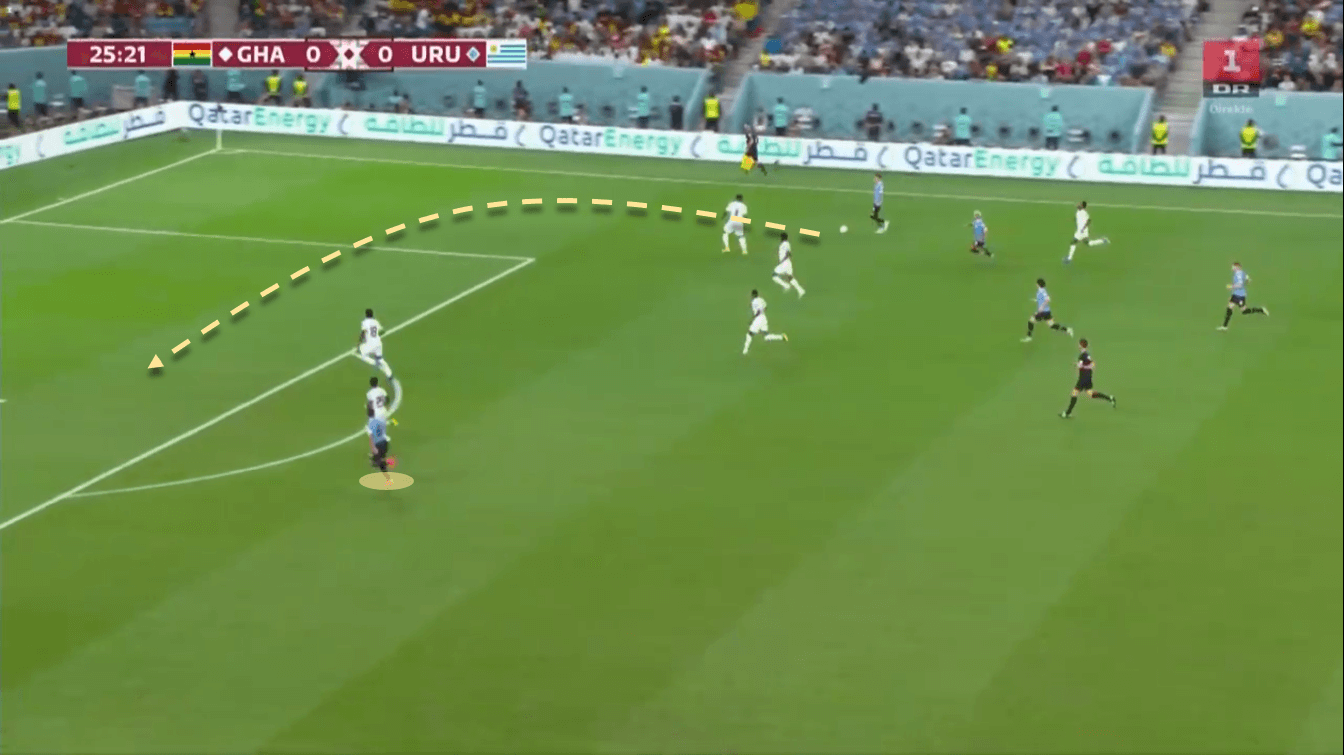

If they couldn’t find spaces on one side, they would quickly switch to the other to activate the weak side of the ball, which they did in a great way to look for their full-backs who, with their aggressiveness, could take the ball and advance quite a few meters over the field in order to help his team generate threat. These changes were normally made by Rodrigo Bentancur or one of the central defenders of the Uruguayan team. When the ball travelled to one side, the full-backs warned if they hated to move the ball or turn the possession around again.

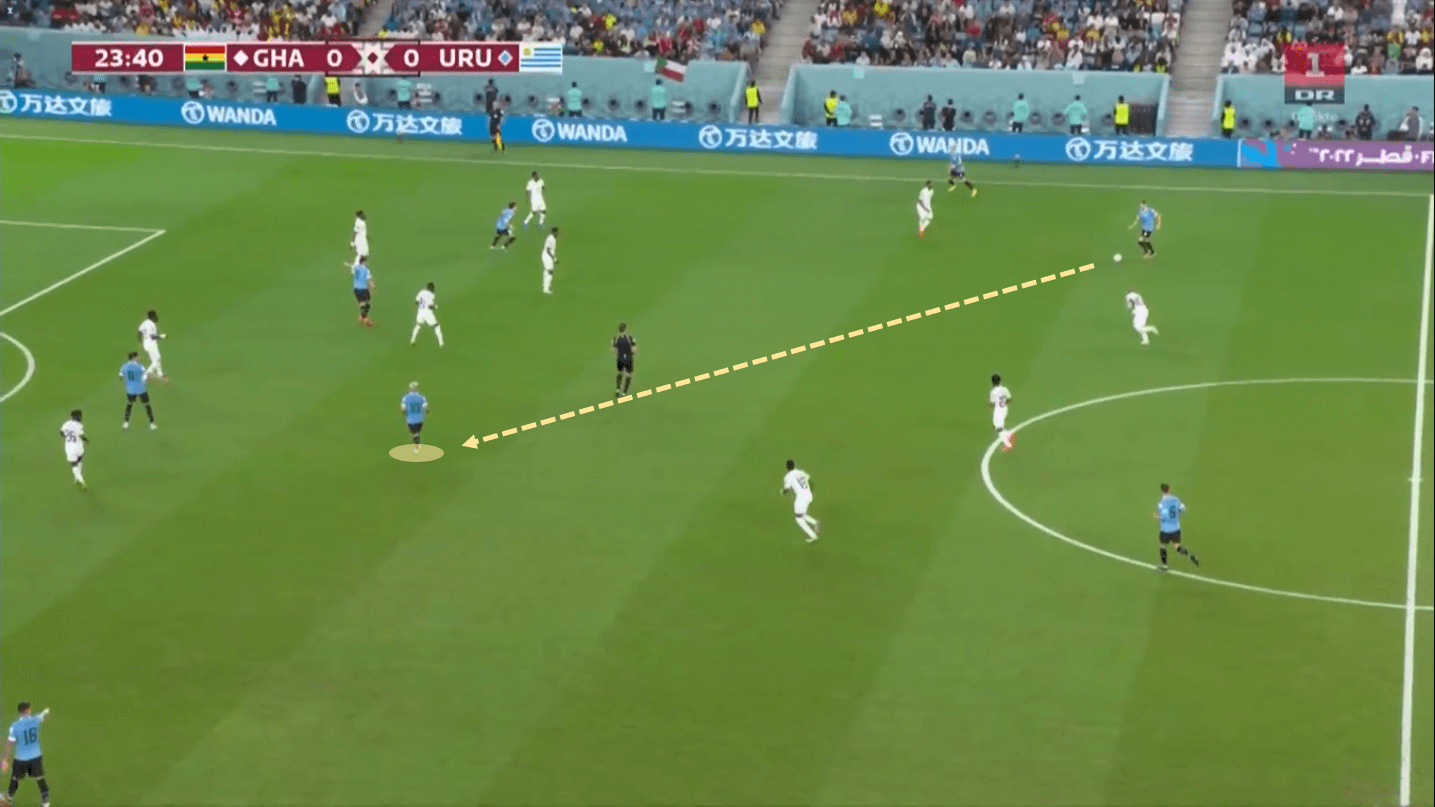

This picture is a clear sight of how Ghana wanted to defend this against Uruguay, however, the lines between the players were so wide and large, and disorderly, making Alonso’s team easier to change the ball to the weak side and keep progressing.

The South Americans overloaded quite well on one side, added to the defensive passivity of Ghana who did not enter the match in the most focused manner and performed at the high level they had shown in their first two matches. Fede Valverde or Rodrigo Bentancur were important in their approaches to taking the ball, playing first-time passes and combining with their full-backs or wingers, but also to turn their vision around and find the player on the other side of the field.

A lot of back-passes were made with a sense for this. They were moving frequently the Ghanaian block back and forth that at one point, this back-pass would attract their lines and then Uruguay would manage to execute the pass to one of their well-positioned players out wide, which was normally the full-back, who took the ball and looked to cross or pass, depending on at which height he received.

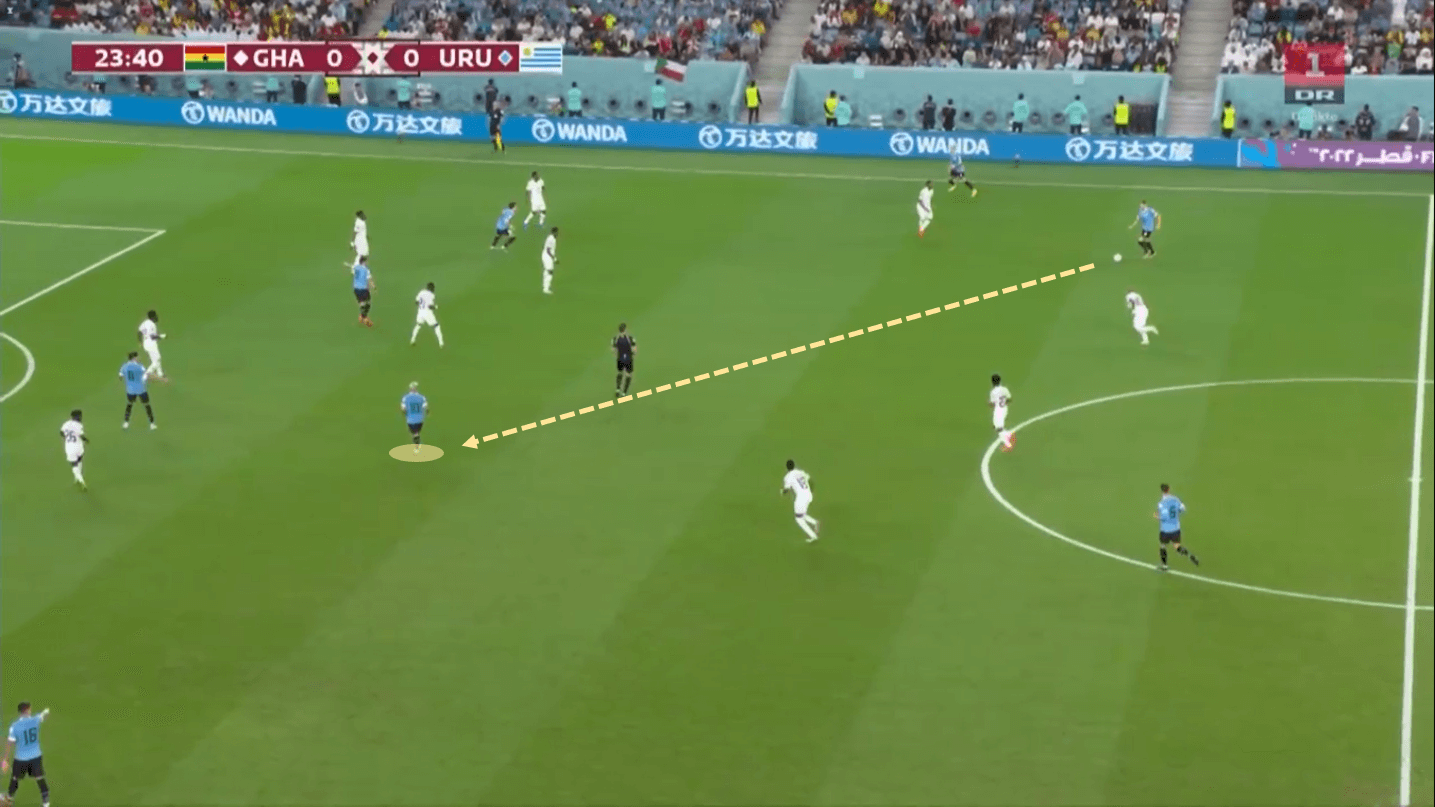

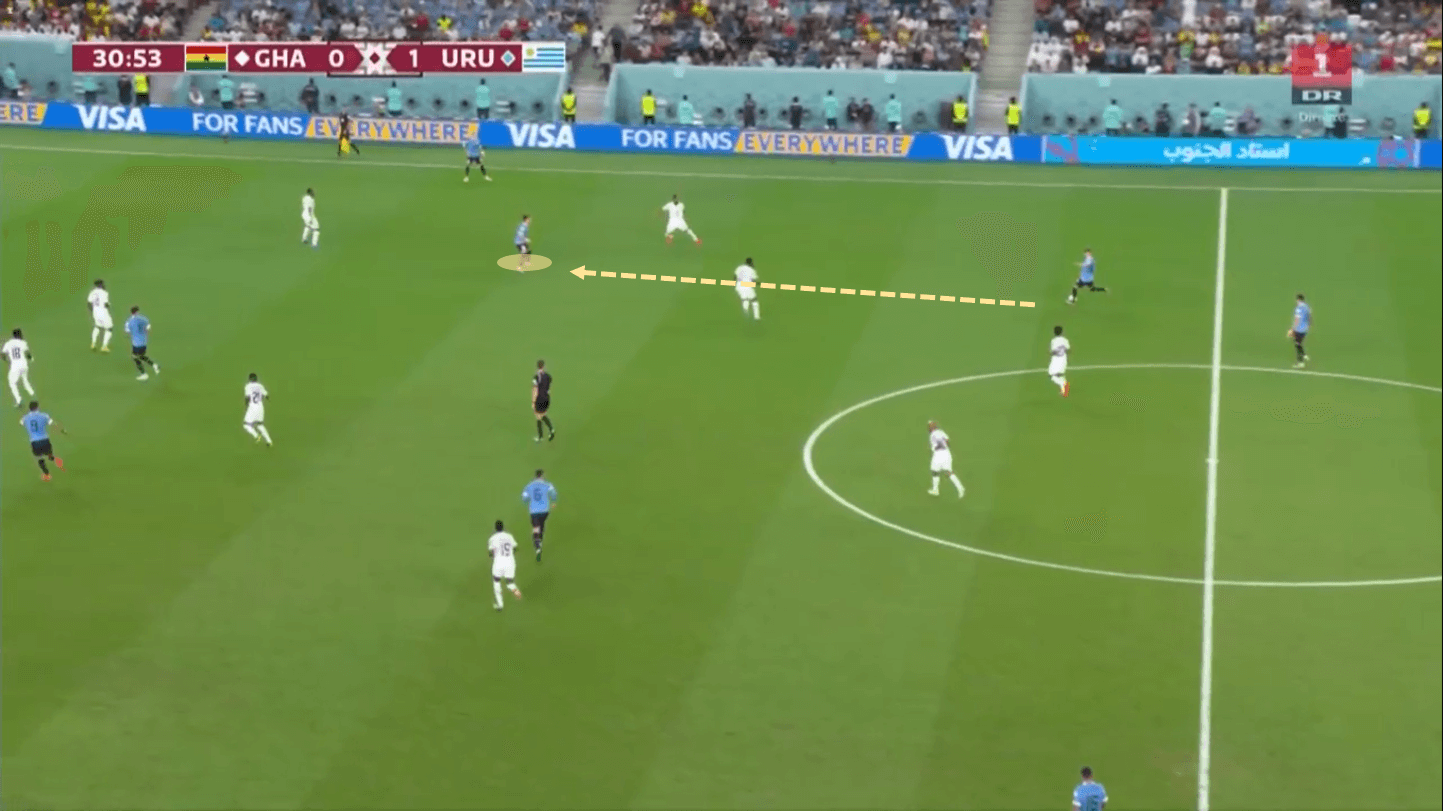

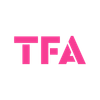

One of the vital things about the match was the synergy between Luis Suárez and Giorgian de Arrascaeta who, playing on the same wing and more centralized, could exchange positions in order to create space between them.

One of the clearest moves between these two that gave Uruguay a lot was Suárez dropping to receive between the lines, only to turn and find de Arrascaeta taking his place and attacking the space between Ghana’s central defenders. As we can see in this picture below, previously the game has been changed from one side to another, where Giménez decide to carry the ball and create a new passing angle with the movement of Suárez who turned brilliantly and found de Arrascaeta running to his space and even dragged markers to make Núñez more freely at the other side.

Giorgian de Arrascaeta was key because, in addition to understanding the movements with a player as important in the Uruguayan system as Suárez, he had a fairly free role on the field, and with him, Uruguay gained something that they had not had in their previous games: Creativity and freedom between the lines, as well as constant offerings to help his team elaborate dangerous plays, as he looked to speed up possessions with one or two touches.

The Flamengo player used to always receive in the half-space or in the central space, where he sought to find players attacking the last line of defenders with his first touch or control the ball and see the goal from the front, to decide whether to shoot or look for a through-pass. Uruguay won with his entry, a player who gave them verticality in the middle and through passes that they didn’t have. A fresh pair of legs and a creative mind to threaten opponents.

Another of the things that were seen when he entered the pitch against Portugal, was this type of movement from inside to out, where he received and looked to automatically cross the ball into the penalty area, surprising the opponent’s markers.

Against Ghana, he did the same thing, and with a more electric Uruguay in the aspect of working passes inside and then receiving outside and throwing into space quickly, he generated a lot with his runs from one side to the other. The role was so dynamic and mobile that he appeared as a winger on the other side of the pitch several times throughout the game.

However, they also gained an attentive and intense player under high pressure as well as committed to counter-pressure. In addition, after an opposition loss, he was the most sought-after on his team to orchestrate quick transitions. The aggressive and ‘chaotic’ movements, as Darwin Núñez’s runs are often called, provided Uruguay more and more with a passer like Arrascaeta, who threw this type of execution between the lines extremely quickly for his teammates and drew diagonals to space.

Another of the important players in Uruguay’s victory was Facundo Pellistri, more like an inverted winger who offered a lot between the lines and was found by his teammates from deep, such as Valverde, Bentancur or José María Giménez, as well as Sebastián Coates. The progression from behind was working quite well for Alonso’s team which also had these receptions in advanced half-spaces that provided a lot.

The build-up prior to the goal was thanks to the precision of a forward pass from Federico Valverde, who found Pellistri thanks to his vision, who was able to turn and connect with Darwin Núñez, the latter with Suárez and carry out the continuous work seen in this match: Overload centrally to then release to the outside, where de Arrascaeta appeared free to score a brilliant volley, doing even more honour to his mobile role on the field.

These types of executions mentioned before by full-backs, after receiving from a player on the inside were becoming more common and the way in which Uruguay was controlling and guiding fast attacking transitions. But Pellistri’s role was also key.

The Manchester United player was constantly exchanging central and outside channels, in order to attract marking and get into 1v1 situations where his dribbling ability is very good, but also with his explosiveness look to gain the position and send cut-back crosses.

As expected, the forward duo also offered a lot of mobility for Uruguay, with typical movements within the game style of each one of them. While Luis Suárez went further down the thrids due to his brilliant skills in link-up play to play inside, Núñez, as usual in Liverpool and did in Benfica, took the flanks to send crosses or run from there to penetrate the penalty area.

Alonso’s team’s first goal was even because of this. Suárez took the place he had been taken and Darwin appeared on the outside, thus creating spaces for Giorgian de Arrascaeta to activate as a striker, and the Liverpool player made crosses from the outside, which fell to the far post at the feet of Suárez, who finished off and the goalkeeper’s remote benefited de Arrascaeta to score.

Conclusion

The interesting movements that we saw in this last meeting of Uruguay in the World Cup in Qatar 2022, were several that were applied in the preview of the tournament in the South American qualifiers. However, Alonso’s decisions were completely different in his first two games, except for the second half with Portugal and this one with Ghana, which, due to goal difference, was left out of the competition.

Comments