A floated cross is a cross that has a higher path than the normal one. This means that the cross takes a long time across the air, starts to lose its speed at a high point, and then, the ball starts its journey to fall. You may remember many teams that use this kind of corners, and you usually feel afraid when your favourite local team faces a team using this strategy because the ball drops from a high point to the best header of the opponent who can push, jump and shoot or tries to pass the ball by his head into the crowded six-yard and the chaos begins.

At first glance, you think that this strategy is no longer a high-level one because, this time, it gives the defending teams the time to react, which means that it isn’t allowable to use the modern tactics of set pieces with runs, fake runs, blocks and screens to form gaps in the defending scheme. You may be right, especially after elite teams find many ways to deal with this strategy, but there are still some effective tactics used in elite leagues, as we will explain.

In this tactical analysis, we will explain how using floated crosses is a useful and effective way to dominate the attacking corners if you have an excellent player at aerial duels in not-high-level competitions while being less effective in high-level ones because elite teams have counter ideas to use against them.

General benefits against the marker

Floated crosses can give a huge advantage to a team that has an excellent player, or more, at aerial duels because of two main reasons:

1- An isolation situation, a clear 1-v-1 conflict.

2- Orientation problems.

Starting with the first point, floated crosses give the excellent attacker a way to show his abilities of winning the aerial duel against the man marker far away from the zonal defenders or in a nearer position if the opponent defends with a man-marking defending system. But how does this isolation situation show the ability difference?!

When the ball reaches the highest point and starts to fall away from the zonal markers, the two competitors start to measure when and where the ball lands, and this measurement is an ability that can make a difference, so it is the first conflict.

The second conflict is that the attacker has also time during this long journey of falling to push the defender using the power mismatch or by measuring the highest point he can jump to from a steady estate. In contrast, the defender can’t, because of the ability difference at jumping or at power, as we have mentioned, by using his hands to fix the defender down.

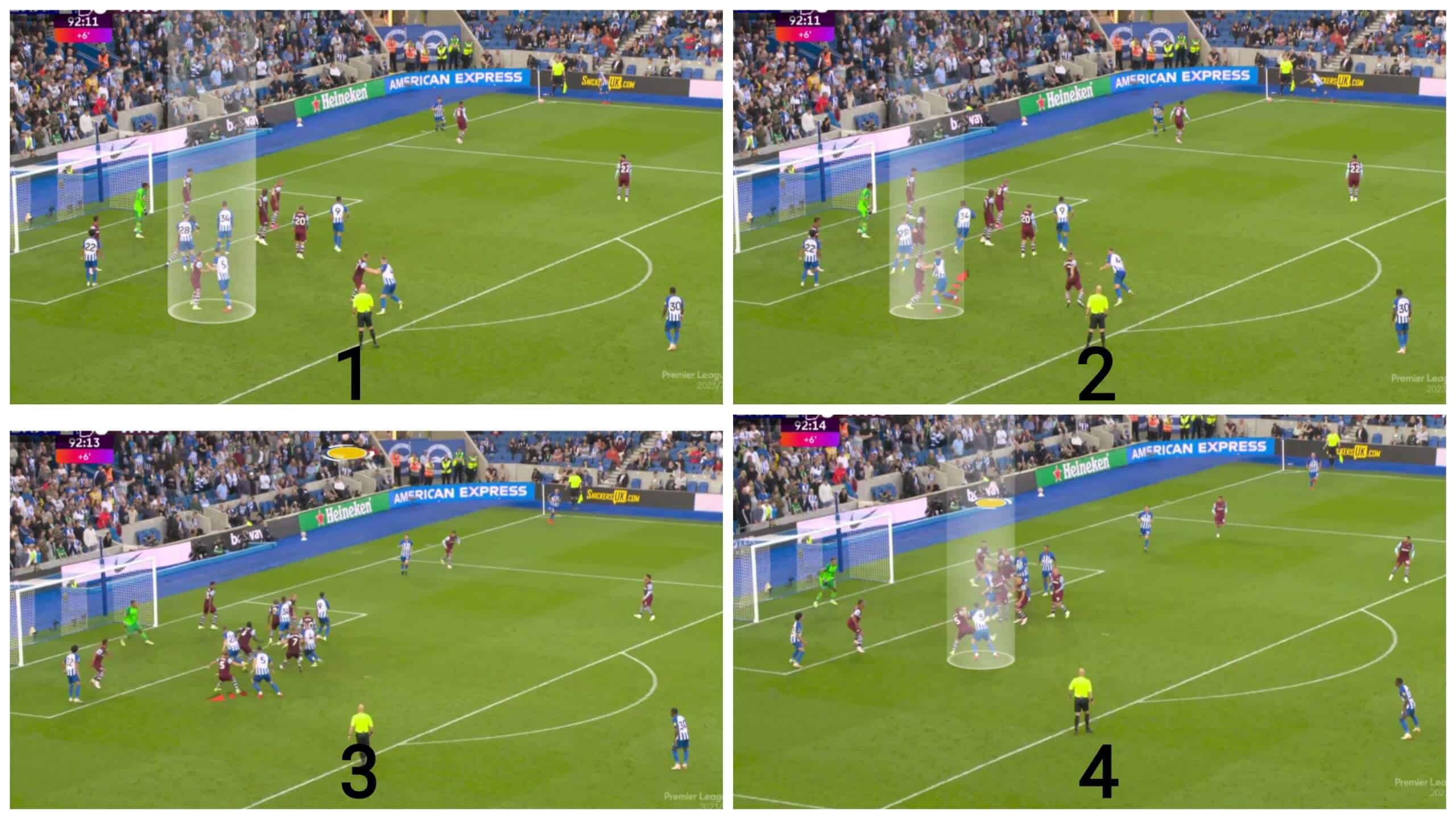

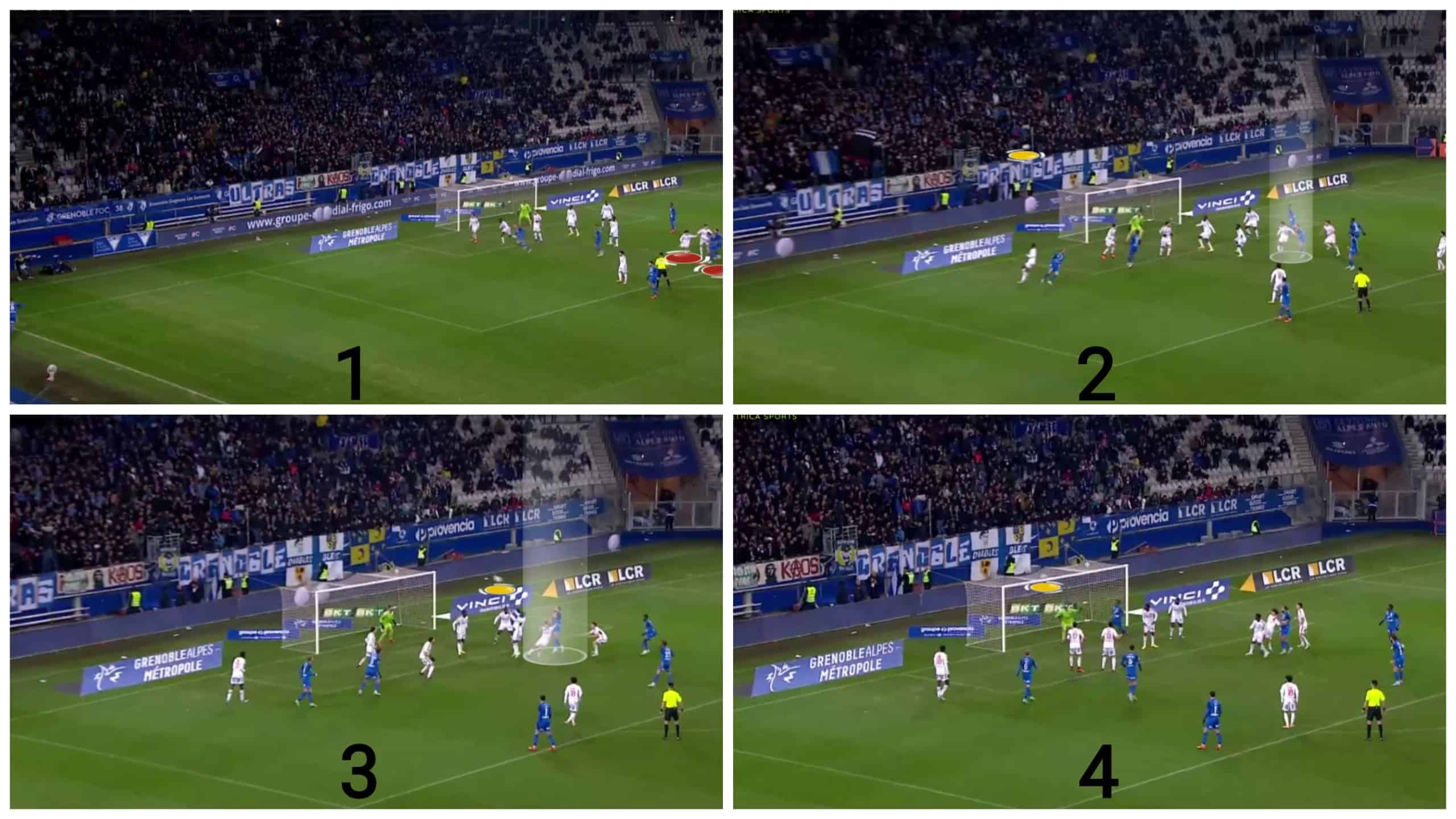

As an example, you can find Lewis Dunk, highlighted in the first photo below. He pushes the marker and moves a bit to the right when the taker moves and then moves to the left when his marker is busy with the ball in the air, in yellow, as shown in the second and third photos.

In the fourth photo, when Dunk measures that the ball becomes nearer, he pushes the market away, then jumps putting his hand on the marker to fix him down.

He wins the duel, but a zonal defender comes back to the near post to save the ball, as shown in the two following photos below.

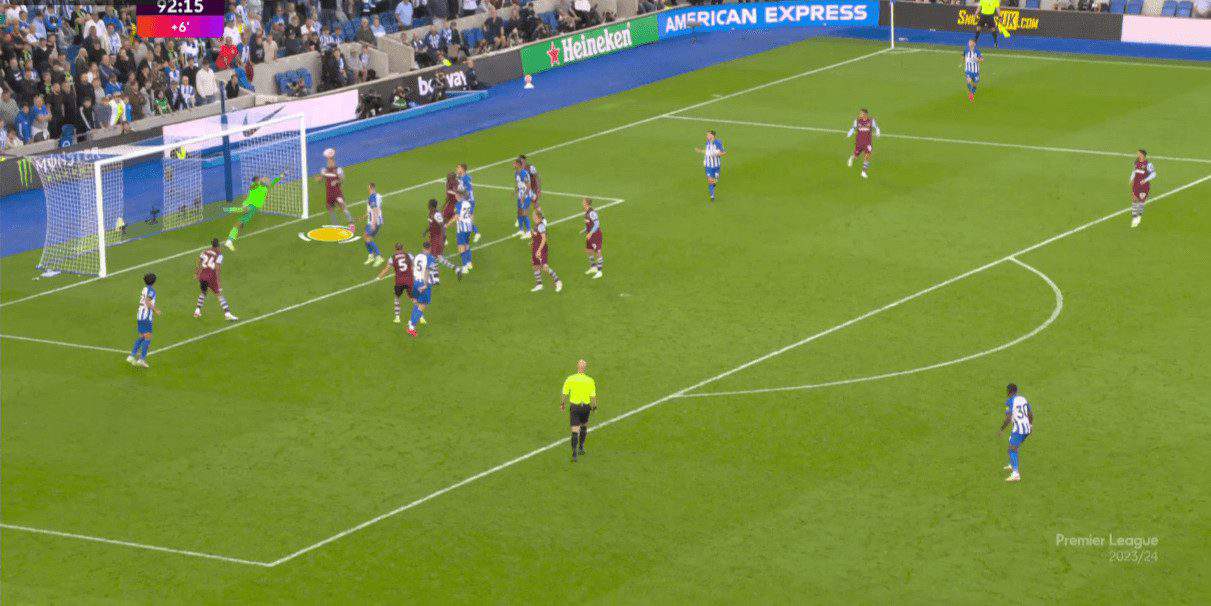

The case below is an example of how floated crosses give the attacker the time to measure the ball in the air and then move to it even if the cross isn’t optimum.

In the first photo, the attacker starts in the middle and then, goes to the targeted area, in yellow, which already happens in the second and third photo, where he and the marker still wait for the cross.

In the fourth photo, another benefit of the floated cross appears: the attacker has the time to measure the ball in the air, adjust his position, and step back if the cross is inaccurate.

As shown below, he wins the first touch while four attackers wait for the headed pass in the six-yard.

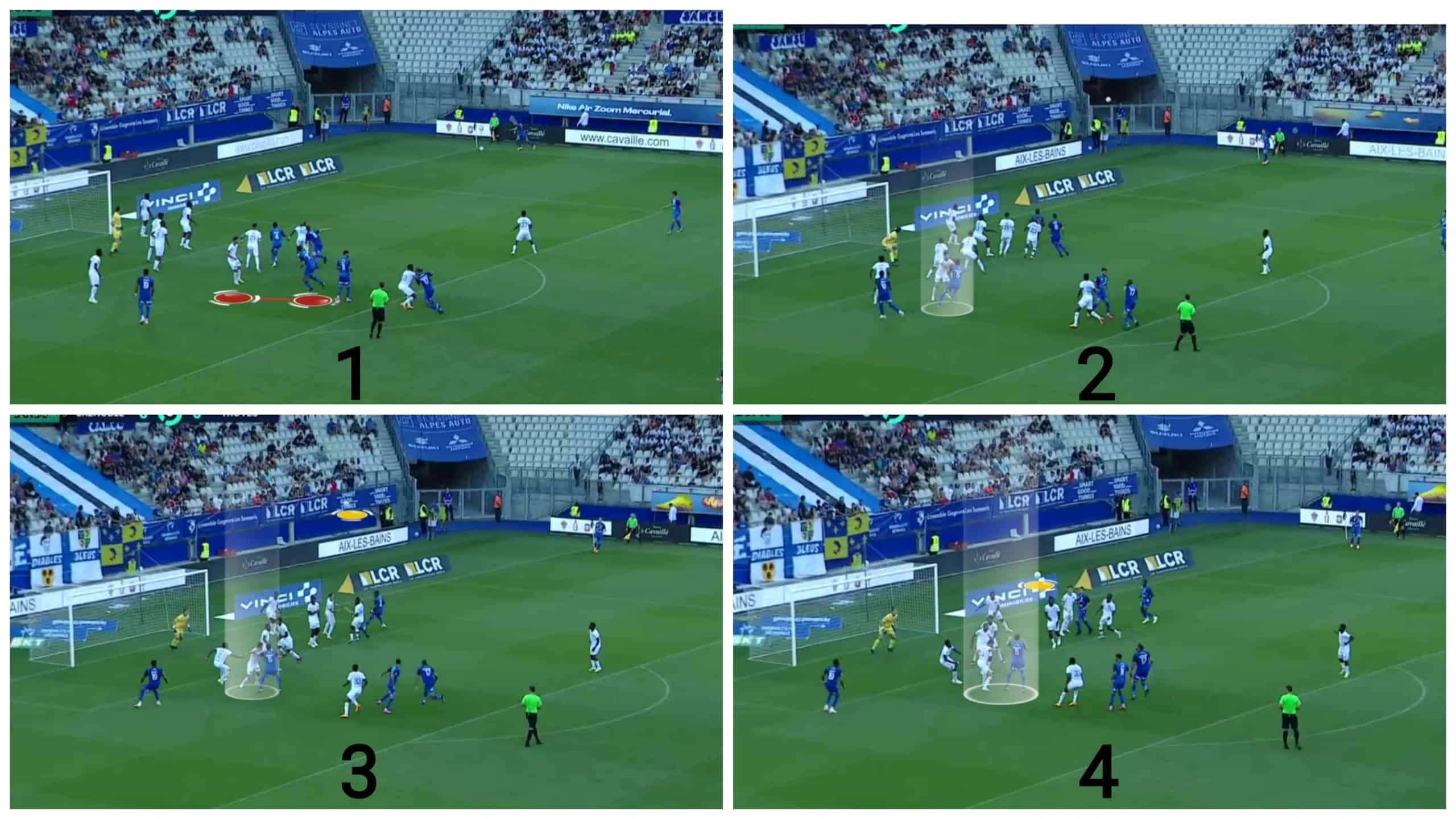

Coming to the second point, it is too difficult for a man marker to keep tracking the ball and the attacker all of this time and area. He is asked to raise his neck up to track the ball while trying to be in touch with the attacker who moves all of this time and spaces, especially when a good attacker exploits this situation to make himself behind the defender, in his blind side, making the defender between him and the ball. This problem is called an orientation problem.

As an example, you find below the defender keeps tracking the attacker in the first and the second photo, but when the ball becomes high, as shown in yellow in the third photo, he starts to raise his neck to track the ball, and here he loses the communication with the attacker who moves to the ball and jumps freely at the fourth photo below.

Combined with other ideas

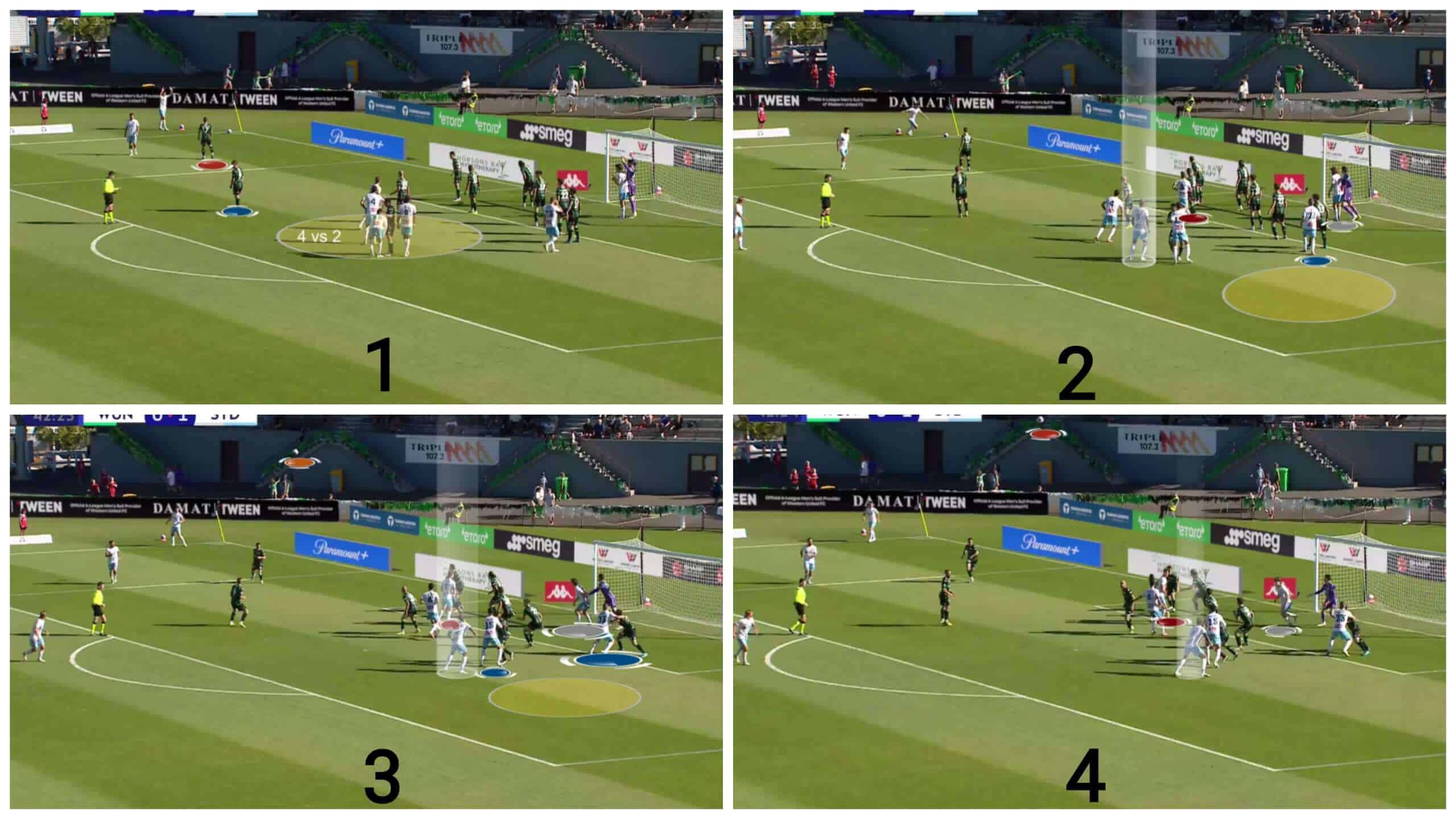

Now, we have known the two general benefits of floated crosses. Let’s discuss some of the ideas that can be used with floated crosses and cause more problems for the opponent at the previous two points. The first idea is starting in far positions, which simply increases the orientation problem due to the larger distance the marker is supposed to track the attacker across.

When you track the four photos below, you will find how difficult the defender finds it to track the attacker from the edge of the box to the position in the third photo, in which it is clear that he loses communication with the attacker who finds it easy to shoot the ball to the crossbar, as shown in the fourth photo.

This idea is also valid against hybrid systems but with a small extra help, which is using a teammate to do a screen, as explained in the case below.

In the first photo below, they start in a pack, overloading the man, marking in a 6-v-4 situation, so two attackers become free, highlighted in the second photo. As shown in the third photo, one of them is used as a screen to free the targeted player.

The targeted player achieves a dynamic mismatch over the zonal line because he runs all this way without physical annoyance, which gives us an indicator that if the marker did the opposite of the previous case and exaggerated in waiting for the attacker near the six-yard, he may don’t suffer from orientation problems, but the attacker may have a dynamic superiority over him; we will know how elite teams deal with that later.

But the cross wasn’t optimum, so the ball passed him, as shown below.

The second idea is using numerical superiority over man markers in hybrid systems to free a player in a far area away from the zonal defenders.

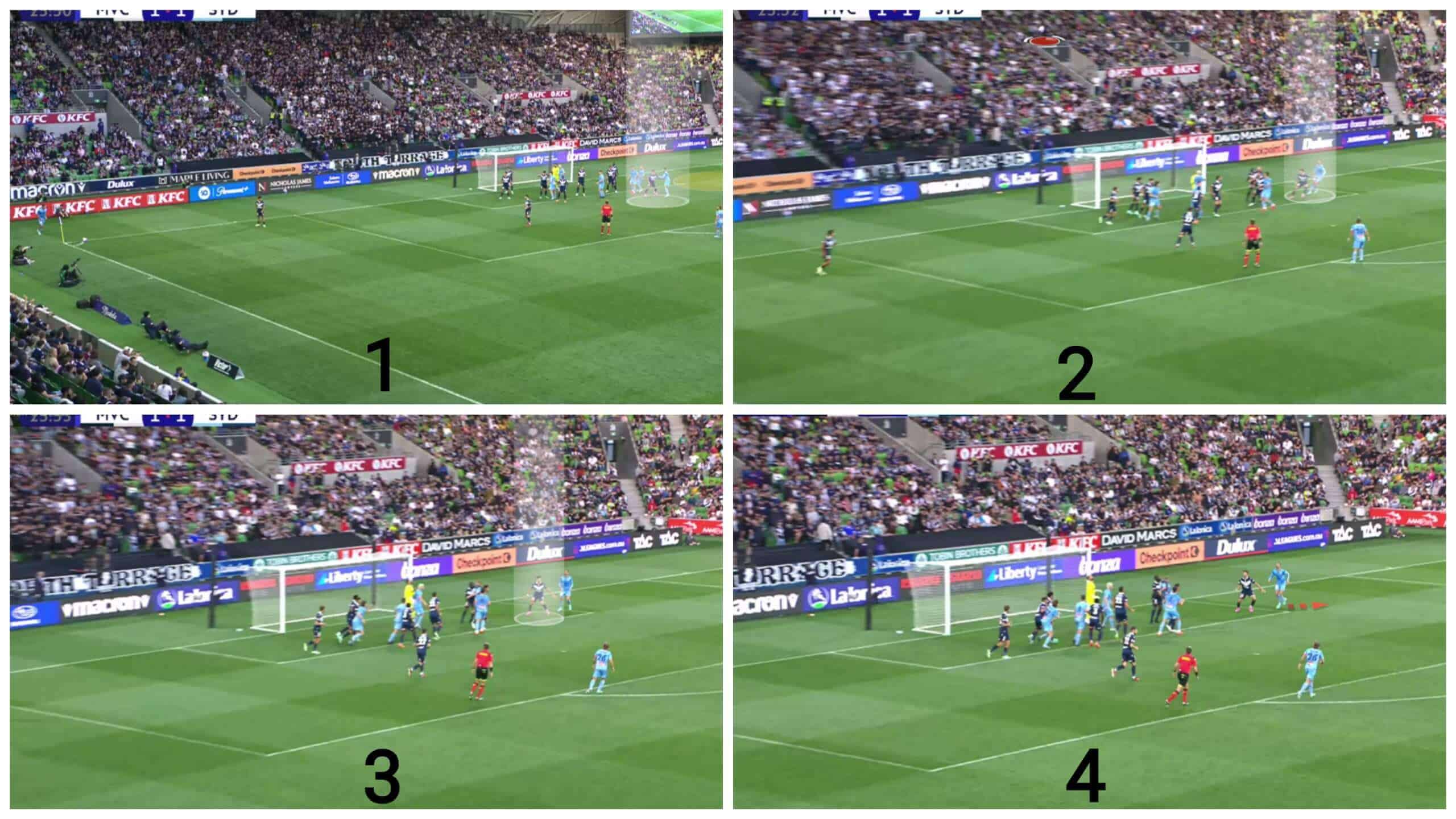

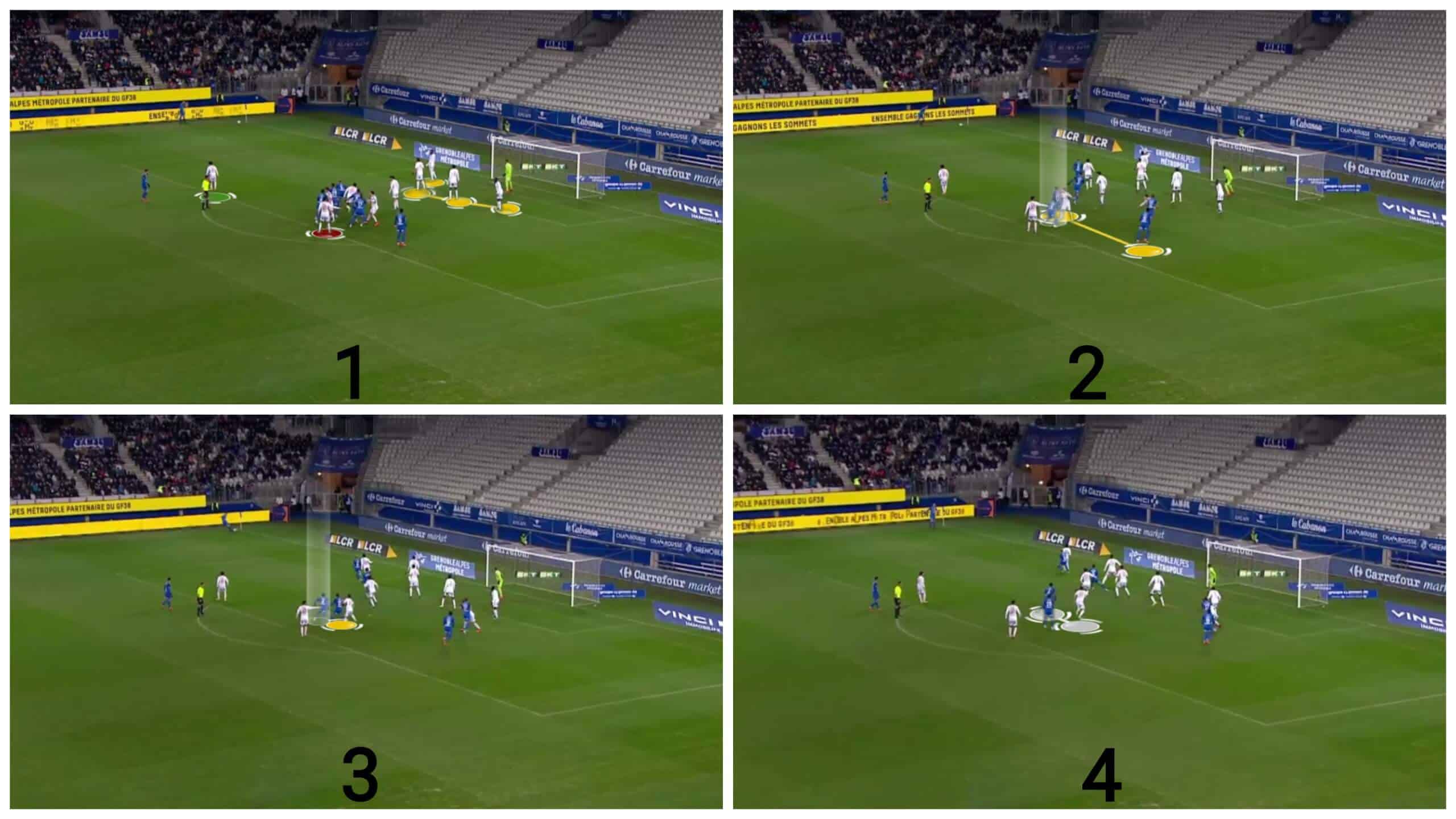

In the first photo below, the opponent defends with a hybrid system involving six zonal defenders around the six-yard line, two man markers, a short-option defender, and a rebound defender. We see the second idea they use this system: overloading the area around the penalty spot, making it a 4-v-2 situation against man markers there. This leaves the other two attackers, one with the goalkeeper while the other stands with the last zonal defender.

In the second photo below, the targeted player starts a bit late away from the two man markers, who go with two attackers, targeting a far area, shown by a circle. The fourth attacker, in red, goes to the near post to receive the headed pass, as we will explain below. The other two attackers’ job is to block the goalkeeper and the last zonal defender because the goalkeeper may decide to go out to claim the ball, and the last zonal defender may go out to the targeted area.

In the third photo, everything is done with the help of the height of the ball, in orange, which forces the defenders to raise their necks to track the ball, allowing the targeted player to escape to the targeted area, exploiting the time that the ball takes on the air. In the fourth photo, the attacker who blocked the goalkeeper leaves him when the ball gets nearer to join his red mate, waiting for the headed pass going a bit back, away from offside.

The other thing that helps in that situation is the unorganised going up from the defence line. You see below the first three zonal defenders go up to implement the off-side trap, but they leave a gap between them and the other zonal defenders, as shown below. Here, we should mention that only high-level teams can reorganise themselves with an organised line without leaving gaps or a player covering the offside, as we will show, so it is a good thing to be exploited when you face a defence like that who rushes to go up without organising. It is also an excellent job from the attacker on the right who blocks the last zonal defender, and this, maybe luckily, helps them more with their essential plan.

The plan works, and the result is a goal, as shown in the two photos below.

We have noticed that winning the ball against hybrid or zonal systems is usually in far areas, so passing, nodding the ball back to the six-yard where many attackers frame the goal is a great method, especially against teams that leave gaps between the line as in the previous case or against teams that don’t implement the off-side trap, as the coming case.

In this idea, attacking teams may also target a player without marking because he isn’t a good player at aerial duels, so opponents neglect him, using him only to nod the ball to an excellent player at aerial duels in a better and nearer area. At the same time, the defenders give their attention to the first headed touch, forgetting the second targeted player at their back. Let’s explain in detail.

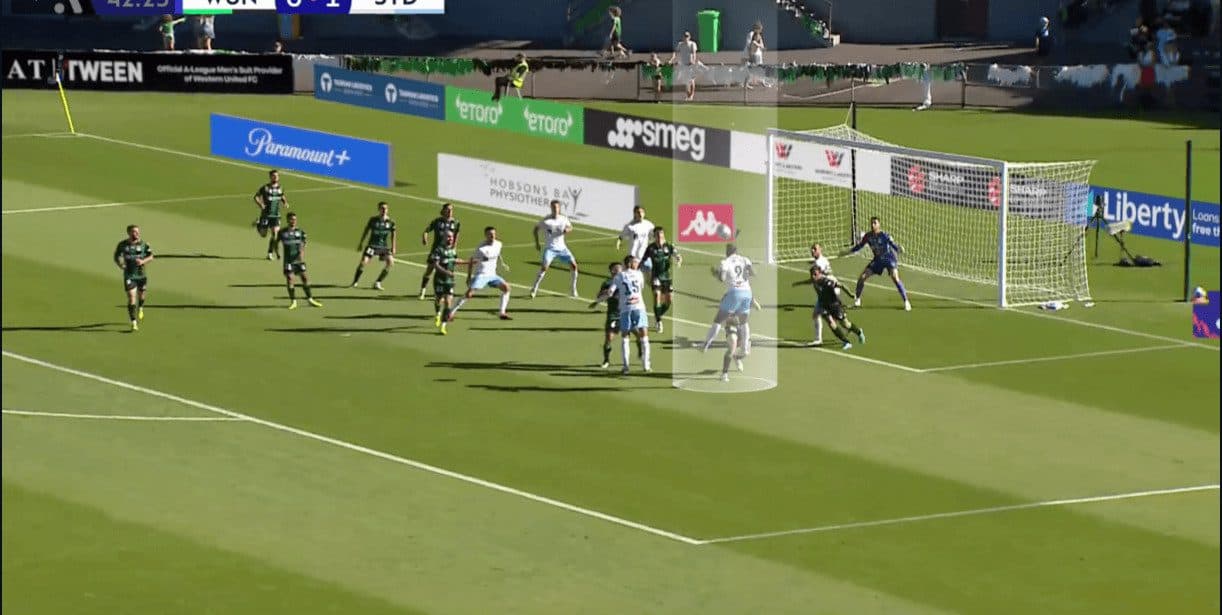

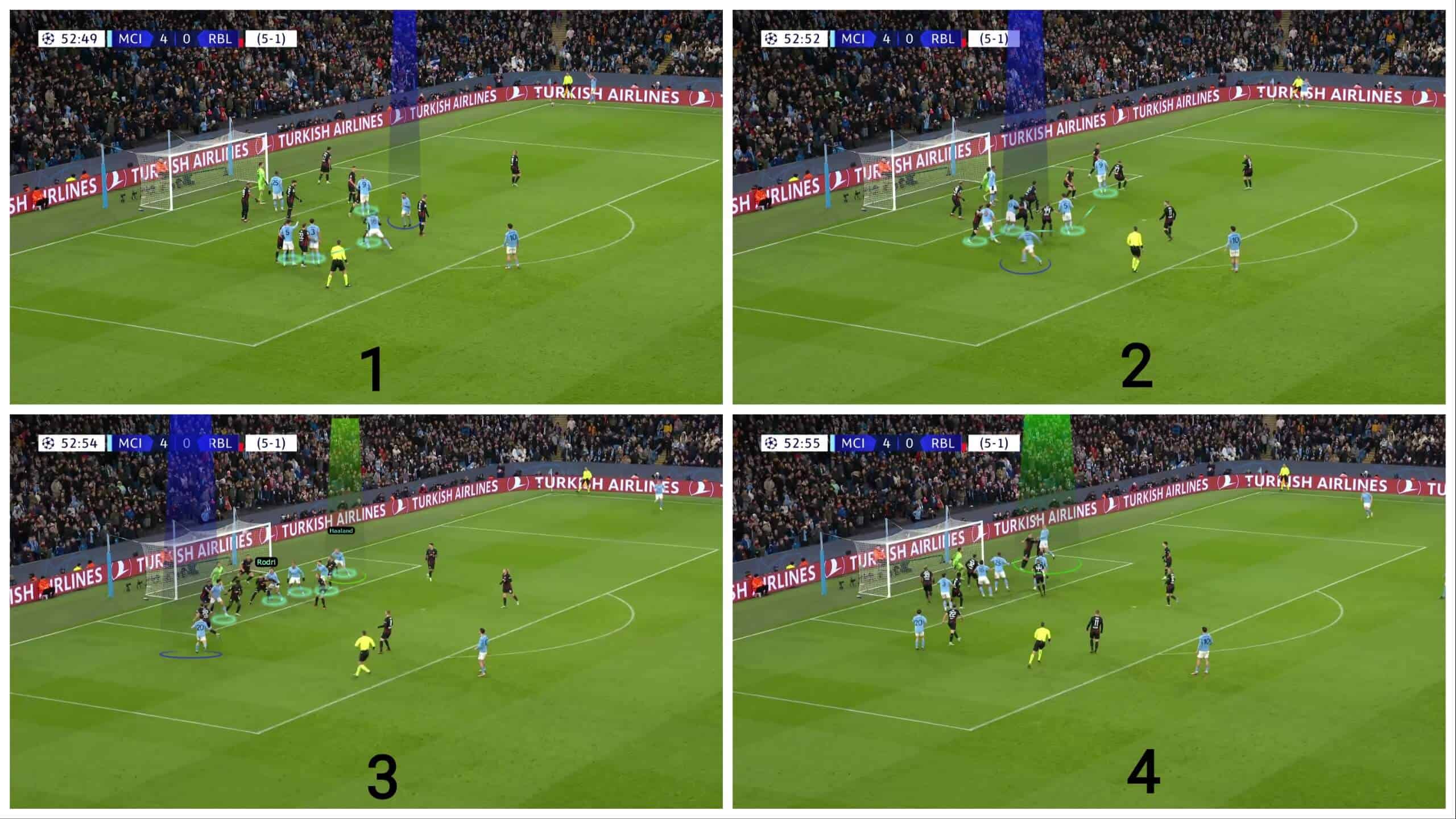

In the first photo, Man City use this idea by the principle of underloading against RB Leipzig’s four man-markers by targeting Bernardo Silva, who is free coming from the near post because he isn’t a dangerous player at aerial duels, so no one focuses on him while the other four attackers are unloading the targeted area for him dragging the man-markers with them, as in the second photo.

In the third photo, five attackers are framing the goal. Rodri blocks the zonal player in the middle to isolate the three attackers behind him against only the last zonal defender. At the same time, another drops back, standing on the line beside the goalkeeper, covering the off-side. Two attackers take the attention to free Erling Haaland behind him, who gets the headed pass, and the result is a goal, as in the fourth photo.

Counter ideas by elite teams

There are two kinds of teams who dealt with that strategy well. The first kind is teams that use a balance between man markers and zonal markers, and they have a way to deal with that, while the other kind is teams that give more importance to zonal markers using only nearly two man markers.

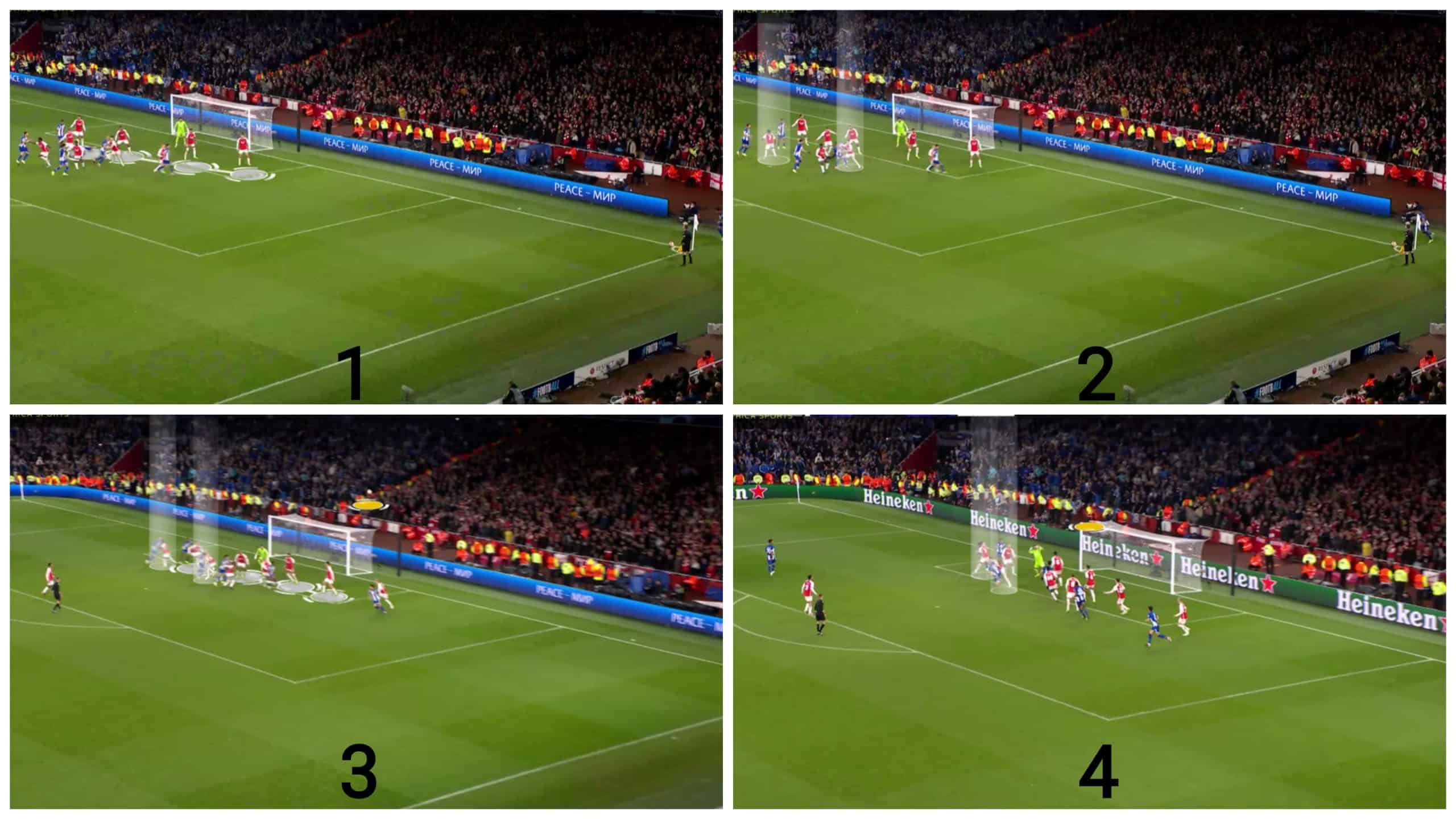

As an example for the first kind, you can see Arsenal defend with four zonal players, highlighted in the first photo, and five man markers against Porto. In the second photo, you will find the man markers, so clear on Declan Rice and Bukayo Saka, with a different man-marking role, which is keeping tracking the attacker only without even seeing the ball, as shown in the rest of the photos in which they gave their back to the ball.

What they do is to avoid the orientation problem by trying to block the dangerous attackers, preventing them from going to dangerous areas or at least slowing down them when they go near the six-yard where excellent zonal defenders deal with that or the goalkeeper goes to claim the ball inside the six-yard before the problem happens and this is an important role, as shown in the fourth photo.

The plan works, and the goalkeeper claims the ball easily.

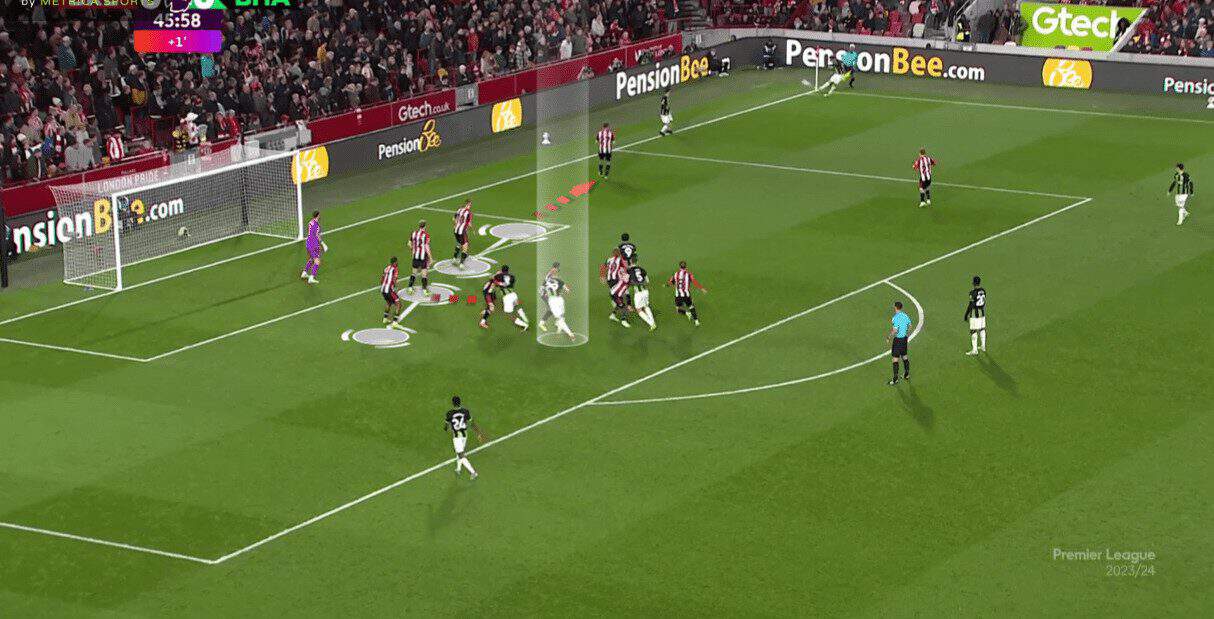

Brentford uses a somewhat similar scheme, and this is an example of giving the zonal defender the responsibility of going out and dealing with the ball with his dynamic movement from the zonal line while the man marker tries to slow down the attacker, as shown in the two following photos.

The plan works and the zonal defenders go out to deal with that while the marker’s job was to slowdown the attacker not to achieve a dynamic mismatch over the zonal defender.

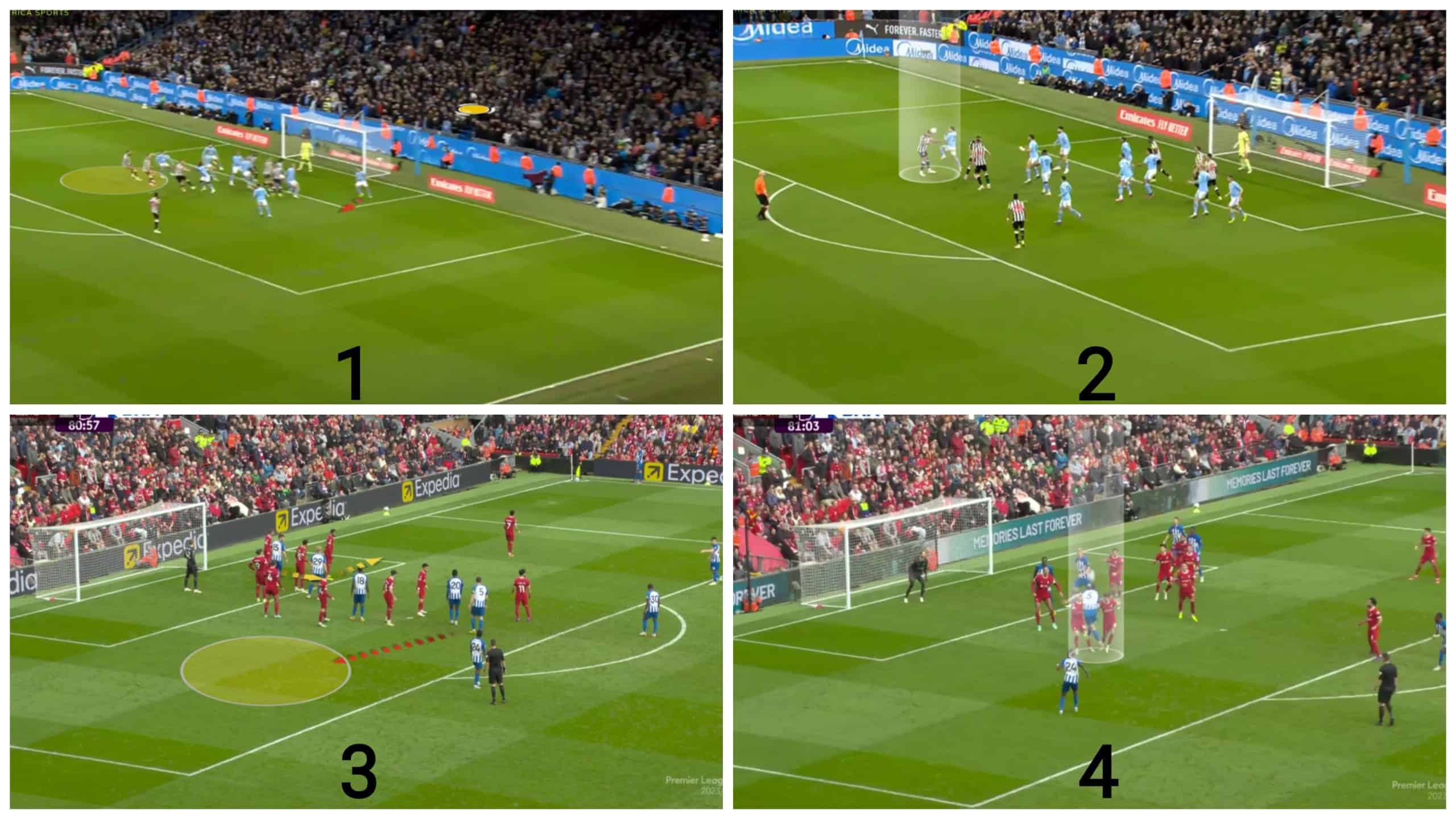

Coming to the second kind, you find Liverpool below, with only two players in front of the zonal line.

They have a role to act as a curtain near the penalty spot to block attackers that try to penetrate toward the zonal line to slow down them to reach the zonal line with no speed to avoid the dynamic mismatch over the zonal line, but if the attackers pass them or start between them and the zonal line, they don’t deal with them leaving them to the strong zonal line considering that they don’t have the space to run before jumping, no chance of dynamic mismatch.

In this case, the first scenario happens, and you find below Dominik Szoboszlai manages to slow down Dunk while Darwin Núñez, the zonal defender, comes out to clear the ball, as shown in the two photos below.

In the corner below, the second scenario happens in the same match, so you can find these two defenders leave the two attackers behind them while Szoboszlai refers to the zonal line that these players are their responsibility, as shown in the two following photos.

The plan works, and a zonal defender clears the ball.

Now, we should mention how elite teams deal with far crosses and nods after that. In the first photo, Newcastle United targets this shown far area. While the ball is in the air, in yellow, the first zonal defender realises that the ball won’t land on the near post, so he quickly runs to form a line with his mates without gaps, as shown in the second photo in which all Newcastle players behind the line are offside while the line os perfect without gaps.

With a different dynamic, Liverpool apply the same strategy, in the third and fourth photos.

These high-level teams find no problems in implementing such a perfect off-side trap, but we may predict a problem at this point for Arsenal because the way of their man markers, as we have mentioned above. Let’s track Saka below.

The ball is in the air, in yellow, while the zonal line pushes up to deal with this floated cross, as we have mentioned. Saka keeps tracking the attacker to the six-yard, which could cover the off-side trap, but luckily, the cross passes everyone, as shown in the second photo below.

Conclusions

In this analysis, we have discussed the benefits that floated crosses give the attacking teams who can use them to dominate the attacking corners when you have an excellent player in aerial duels, especially in not-high-level leagues.

In this set-piece analysis, we have also explained that this strategy has been developed through being combined with other ideas to present effective routines. We have also discussed how elite teams found counter ideas against the usual kinds of floated crosses, so it hasn’t been considered a high-level strategy. However, there is still a method that elite teams are still suffering from, which is used by Everton in the Premier League, which we will discuss in part two next week!

Comments