Serie A has become somewhat of an old boys club — not that it ever wasn’t. Italy’s top-flight division has been highly closed off compared to the rest of the top-five leagues when it comes to appointing talented coaches from abroad.

While financial disparities have played a massive part, the Premier League is a prime example of the fruits that can grow when new ideas are brought to a division. The English top tier has become the paragon of tactical excellence and the breeding ground for innovation.

But despite Serie A being at its most exciting, there seems to be a merry-go-round when it comes to appointing new managers, with clubs more hesitant to appoint younger or more inexperienced coaches as opposed to a steady Eddie.

Thankfully, in recent years, there has been a slight change in the opposite direction. Even now, coaches such as Thiago Motta, Paolo Zanetti, Alessio Dionisi and Raffaele Palladino have all been trusted in Serie A to lead teams with their exciting tactical philosophies.

However, these appointments are often few and far between, particularly with top clubs. In fact, every single team in the top seven right now have appointed men in charge who have been with another top-seven club.

For instance, José Mourinho famously coached Internazionale more than a decade before taking the job with AS Roma. Napoli boss Luciano Spalletti managed Roma on two separate occasions as well as Inter for a season. Maurizio Sarri is on his third top club in five years while Stefano Pioli has been with half the division at this point.

Nevertheless, there is an interesting movement happening in the division below. Serie B has become a hotbed for appointing inexperienced managers but there is one particular similarity between a lot of these coaches – they have World Cup winner’s medals.

Pippo Inzaghi, Daniele De Rossi, Fabio Cannavaro, Alberto Gilardino and Fabio Grosso are all learning their trade in Serie B, having all been part of Marcelo Lippi’s World Cup-winning side of 2006.

The World Cup euphoria doesn’t end there though. Cesc Fàbregas and Gigi Buffon are also still playing in Italy’s second tier, bringing the medal total to seven for the league, which is more than Serie A!

Regardless, we’re here to talk about coaches, and of the five managers with World Cup winner’s medals, one leads the pack, and it’s the man that Lippi’s ‘06 side would never have been crowned champions of the world without — Fabio Grosso.

Grosso’s Frosinone are top of the league right now by six points and currently boast the best defensive record in the league with the third-highest number of goals scored too.

His side play some extremely interesting football in and out of possession, so this tactical analysis piece, in the form of a team scout report, will take a look at the tactics Grosso has been using with Frosinone in the team’s quest to return to the top-flight.

Formation choice

Grosso has been in charge of the Canaries since March 2021 when games were still being played solely behind closed doors.

The 2021/22 campaign was the former full-back’s first full season with Frosinone as he guided the club to a respectable ninth-place finish, with Grosso’s men being seven points off the playoffs which was their ultimate aim.

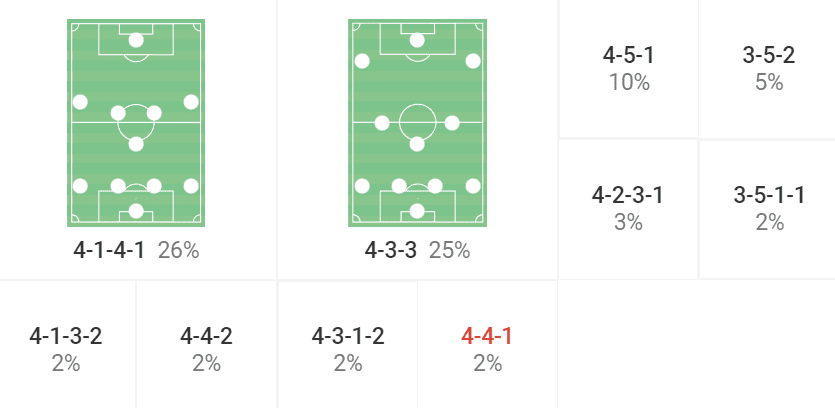

In the previous season, Grosso insisted on deploying a 4-1-4-1 formation, particularly out of possession but the Canaries were no strangers to using a 4-4-2 as well, although this was primarily in the defensive phase.

Nonetheless, this season, the 45-year-old changed things up slightly, looking for more balance in the middle of the park and so began using a 4-2-3-1 for the most part while the 4-4-2 has also seen heavy usage by Frosinone.

Grosso’s team can be quite unpredictable in an attacking sense. Sometimes, opponents will be facing a lone centre-forward with a creative number ‘10’ sitting in between the lines. Meanwhile, on other occasions, the Serie B league leaders utilise a strike partnership up top.

What is interesting is that in more recent games, Grosso has switched back to a 4-1-4-1 and has even begun experimenting with shapes a little more.

For instance, in Frosinone’s recent victory over Modena, the manager lined his players out in a 5-3-2 for the entirety of the first half. However, the side struggled to create meaningful chances and looked a little open in transition, so Grosso switched to a 4-1-4-1. It was goalless at half-time, but by the final whistle, Frosinone had come away with a 2-1 home win. Decisions like these are where coaches truly earn their coin.

But shapes are only a manner to quantify a player’s position on the field and to offer the team a framework within which to execute the manager’s tactical instructions. The system itself is what matters more than a mere formation.

So, without further ado, let’s deep-dive into an analysis of Frosinone’s tactics under the World Cup winner, starting with the team’s build-up from deep.

Build-up and vertical play

Many principles of positional play are implemented into every modern side. However, being called a side that adheres to the Juego de Posicion principles has become far too overused in football nowadays when a team wants to play out from the back or keep possession more than their opponents.

Frosinone fall into this category. Grosso wants his players to keep the ball, but possession isn’t the be-all and end-all of the team’s tactics, hence why the side have only registered an average of 50.01% possession this season.

There are elements of positional play in Frosinone’s tactics such as building with an extra man at the back or overloading one side to switch to the other, but Grosso is someone who encourages positional freedom during games, rather than insisting on stagnant positioning on the pitch.

Firstly, let’s take a look at how the Canaries build from the back under Grosso this season.

It’s important to note that Frosinone maintain a similar shape regardless of whether Grosso deploys a back four or five. This is primarily due to having Monza loanee Mario Sampirisi within the team’s ranks.

Sampirisi is a right-back but is highly adept at playing a more central role as a centre-back in a three-man defensive line. This gives the manager a lot of flexibility to change structures mid-game, as the 30-year-old can play as a full-back and central defender.

As such, Sampirisi will always tuck inside and become a third centre-back. If he starts the game on the right of a back three, this is his natural positioning anyway. But if Grosso lines his players out in a back-four, Sampirisi moves centrally while the left-back pushes higher up the pitch.

This is how Frosinone structure themselves when playing out from deep, while a pivot player operates behind the opposition’s first line of pressure, screening the backline to receive to feet.

As the setup is quite fluid, sometimes the left-back will drop deeper to try and help offer the backline with another passing option to keep the ball circulated. In these instances, the shape reverts to a regular 4-1 during the build-up phase.

Frosinone’s aim is to try and find the player in an optimal position to turn and play forward. Normally, this is one of the central midfielders, hence why the Canaries’ pivot players try to receive the ball on the half-turn so that they can quickly look for progressive passes into higher areas of the pitch.

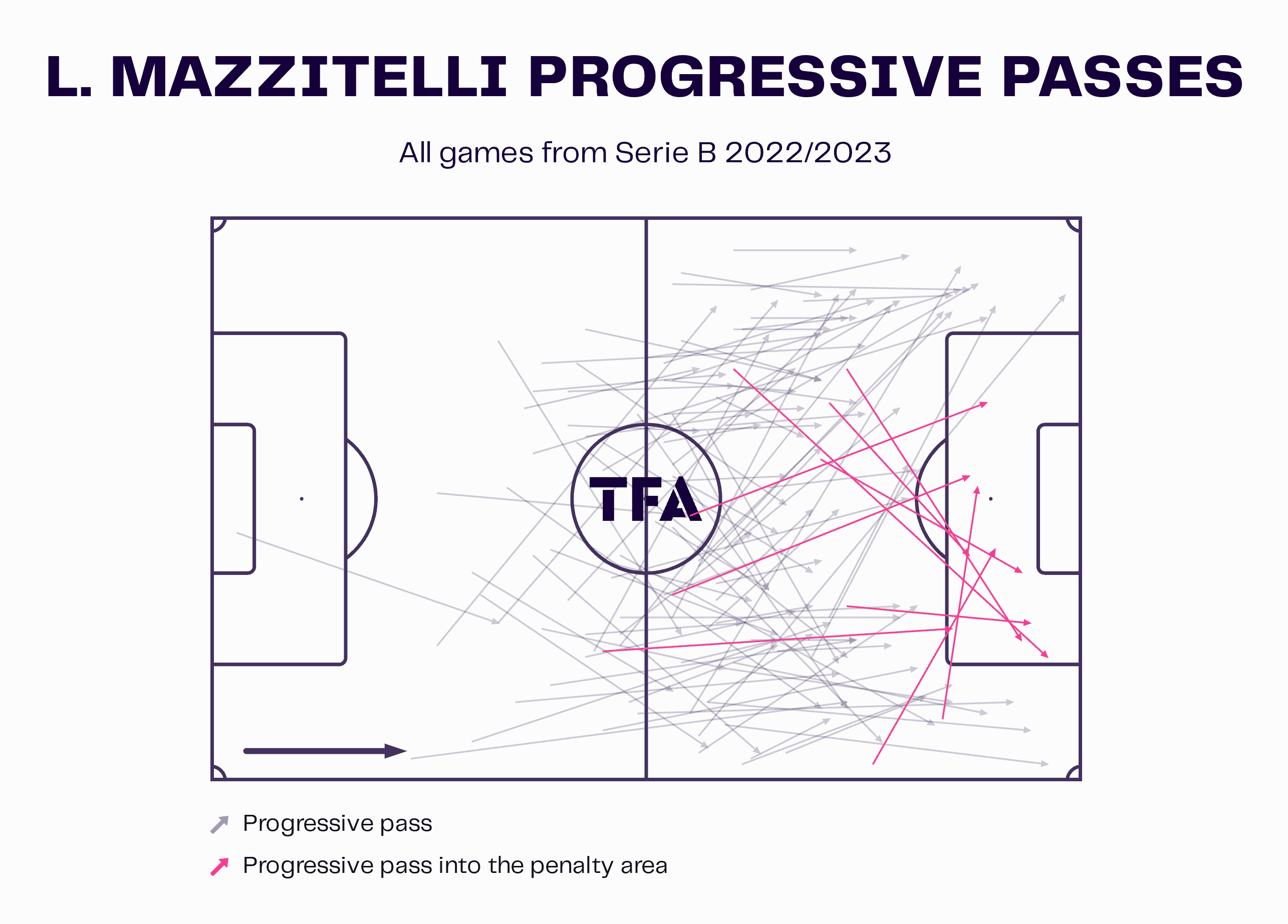

We can see this from Luca Mazzitelli’s progressive passing map from this season in Serie B. Another loanee from Monza, Mazzitelli is really adept at threading balls from deeper central areas into the final third and even into the penalty area.

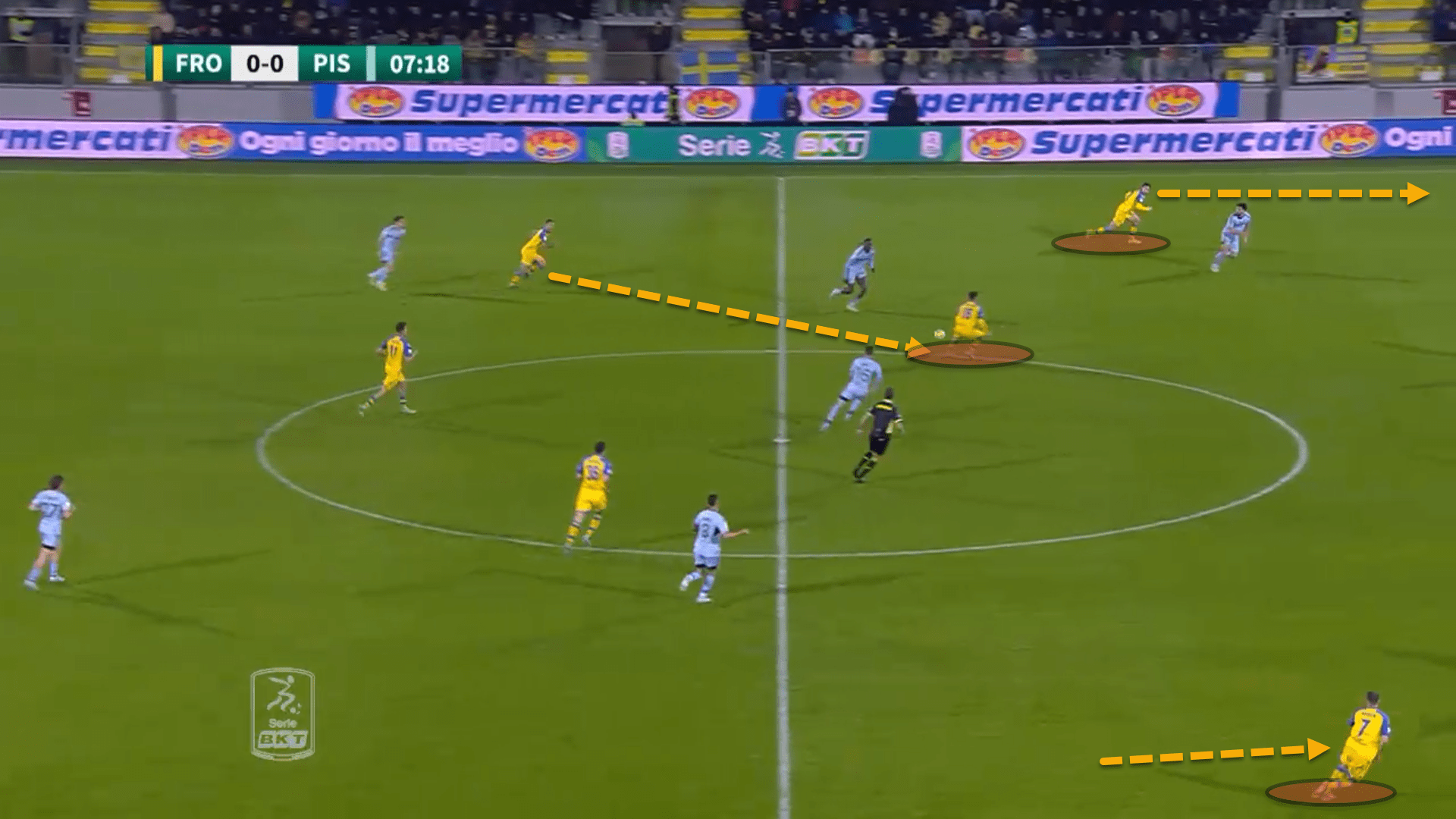

If the passing lanes into the central midfielders or the deepest pivot player are not accessible, Frosinone will look to bait the opposition to one side of the pitch before quickly switching the ball out to the ball-far flank.

This very tactic will rear its beautiful head later in the article too as Grosso, a full-back himself, has mastered the use of width during his time with the Serie B league leaders.

Quite often, when the Canaries play out wide during the build-up phase, the opponent will drop their defensive block across to try and make up the numbers, leaving space on the opposing flank. From there, it is the role of the ball-far full-back to push slightly further forward and get themselves ready to receive a switch of the play before driving forward into the free wide space.

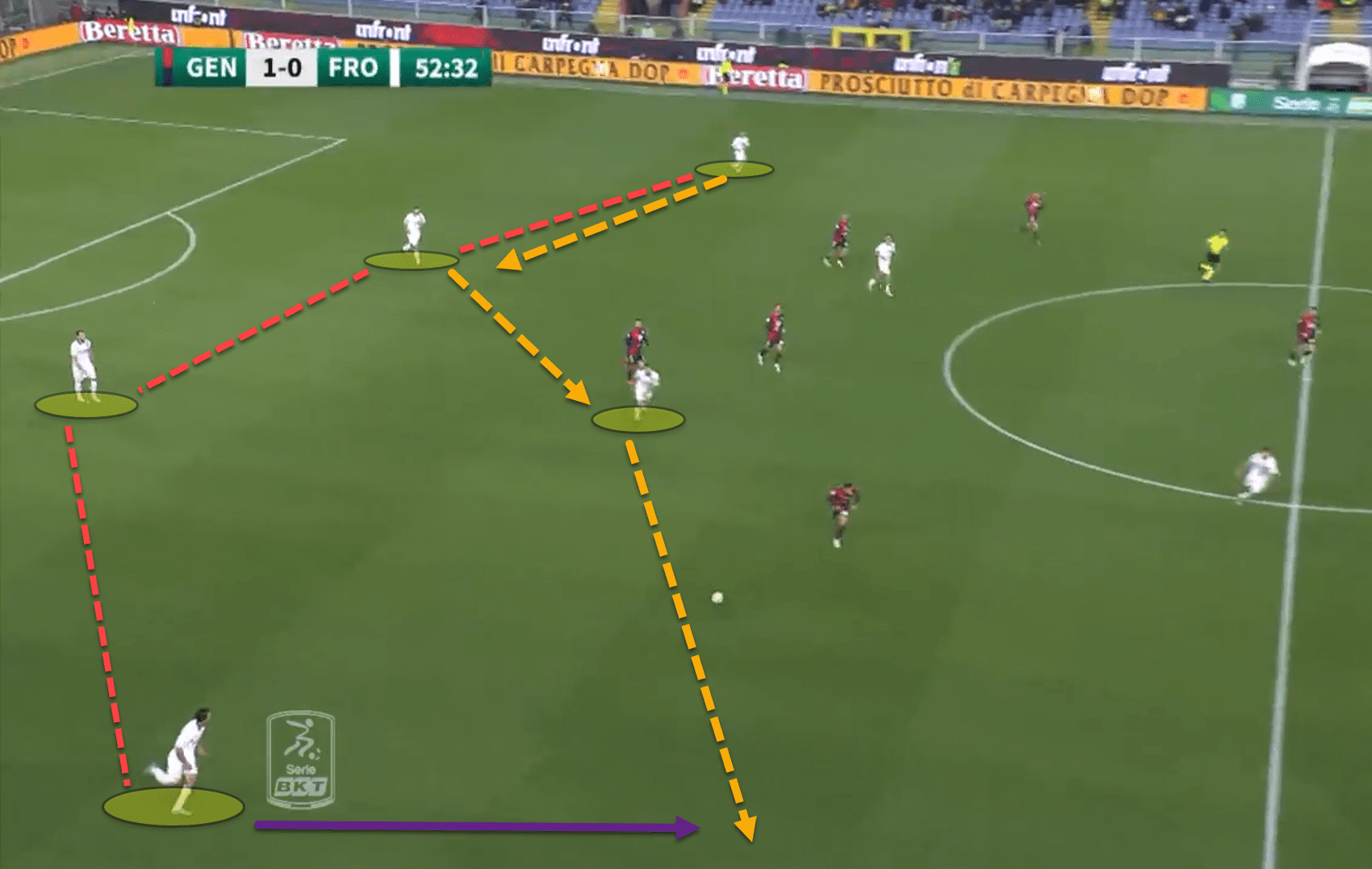

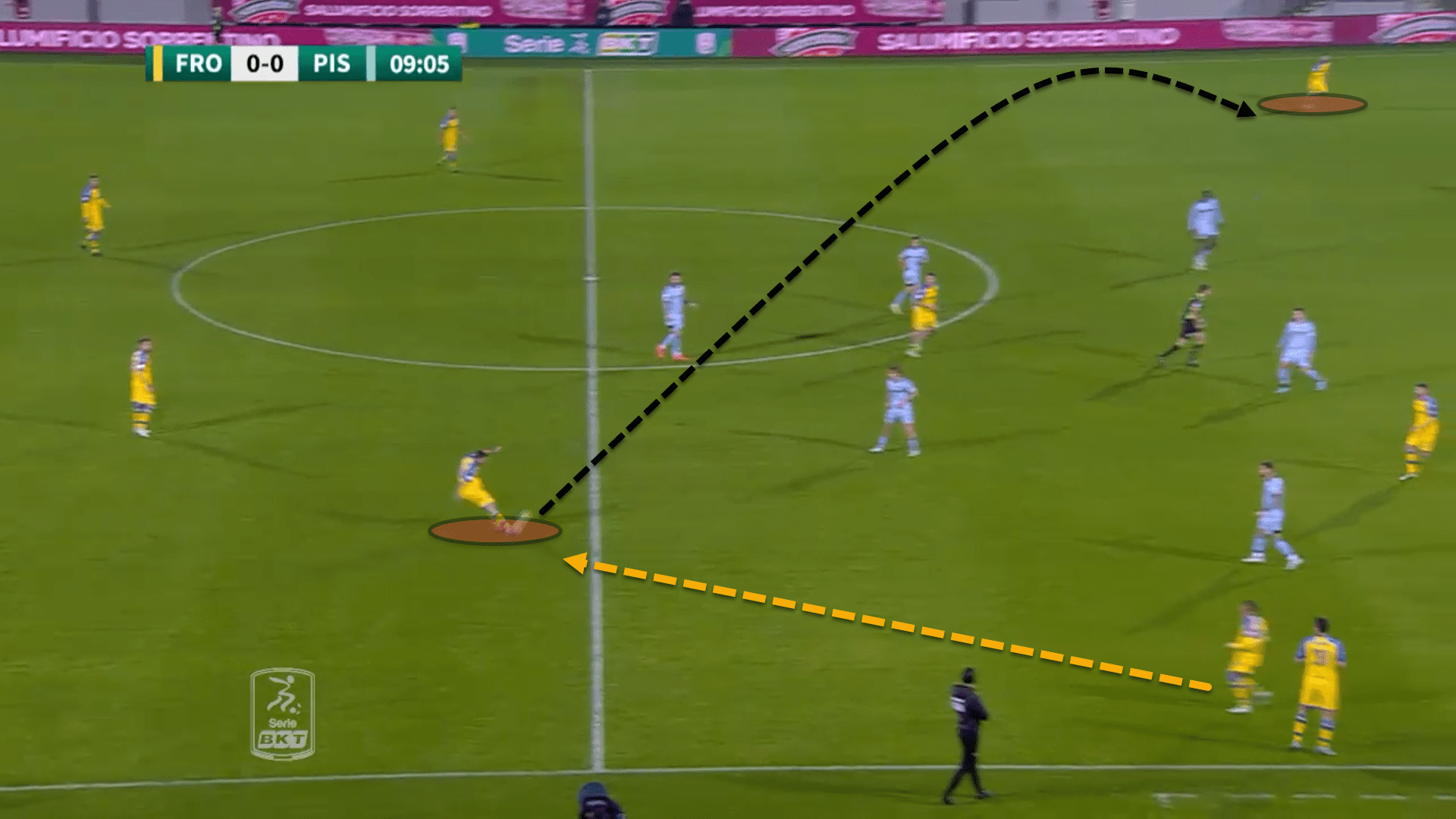

In this scenario against Genoa, the Frosinone central midfielders are marked, so Grosso’s side are forced to use the width of the pitch to progress from deep.

Holding the ball over on the left, the first line quickly move it back inside before switching out to the right to Sampirisi who was already moving up the pitch to receive the ball as Genoa scrambled to shift across their defensive block to halt his ball progression.

These methods of progressing out from the first third of the pitch are not fixed. Sometimes, Frosinone are quite happy with an old-fashioned long ball up the pitch, squeezing their shape together to win the second ball to start the attack in a higher area of the field. This makes Frosinone unpredictable as the side won’t always try to play out from deep.

This season, exactly 12.77% of the Italian minnows’ passes this season are long passes — approximately 50 long balls per game.

Width and depth

There are many parts of Grosso’s tactical setup with Frosinone that resemble that of Massimiliano Allegri’s Juventus who were sitting in the top four of Serie A before a recent scandal knocked the side down to 10th.

Both managers can be flexible with their approaches, but neither are too hell-bent on fixed positioning on the football pitch. Furthermore, both coaches want their teams to constantly attack the depth and width of the field with runs in behind.

Being a left-back in his day, Grosso knows very well how to create space out wide for his full-backs and wingers and it’s extremely evident from Frosinone’s tactics in the final third.

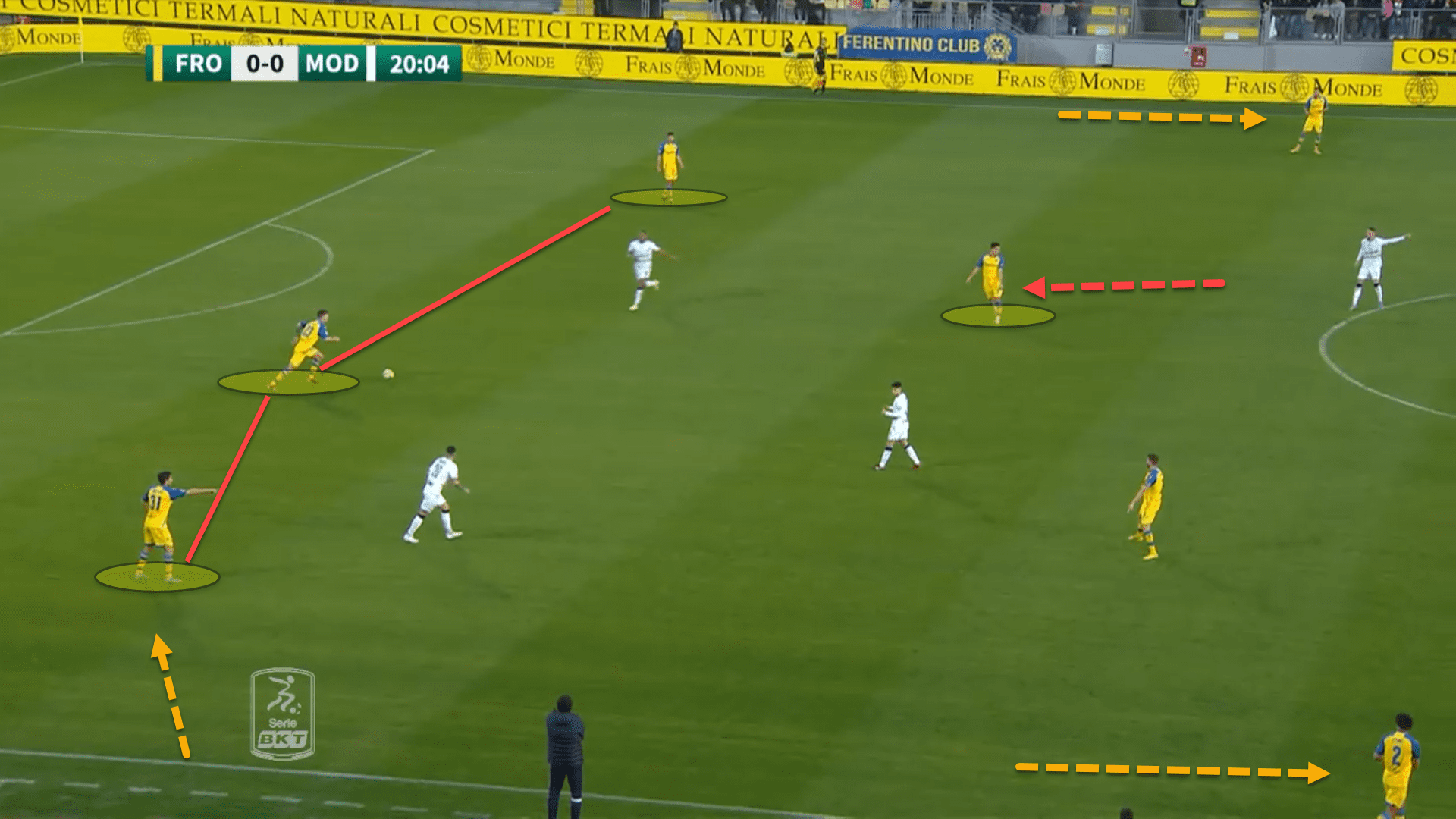

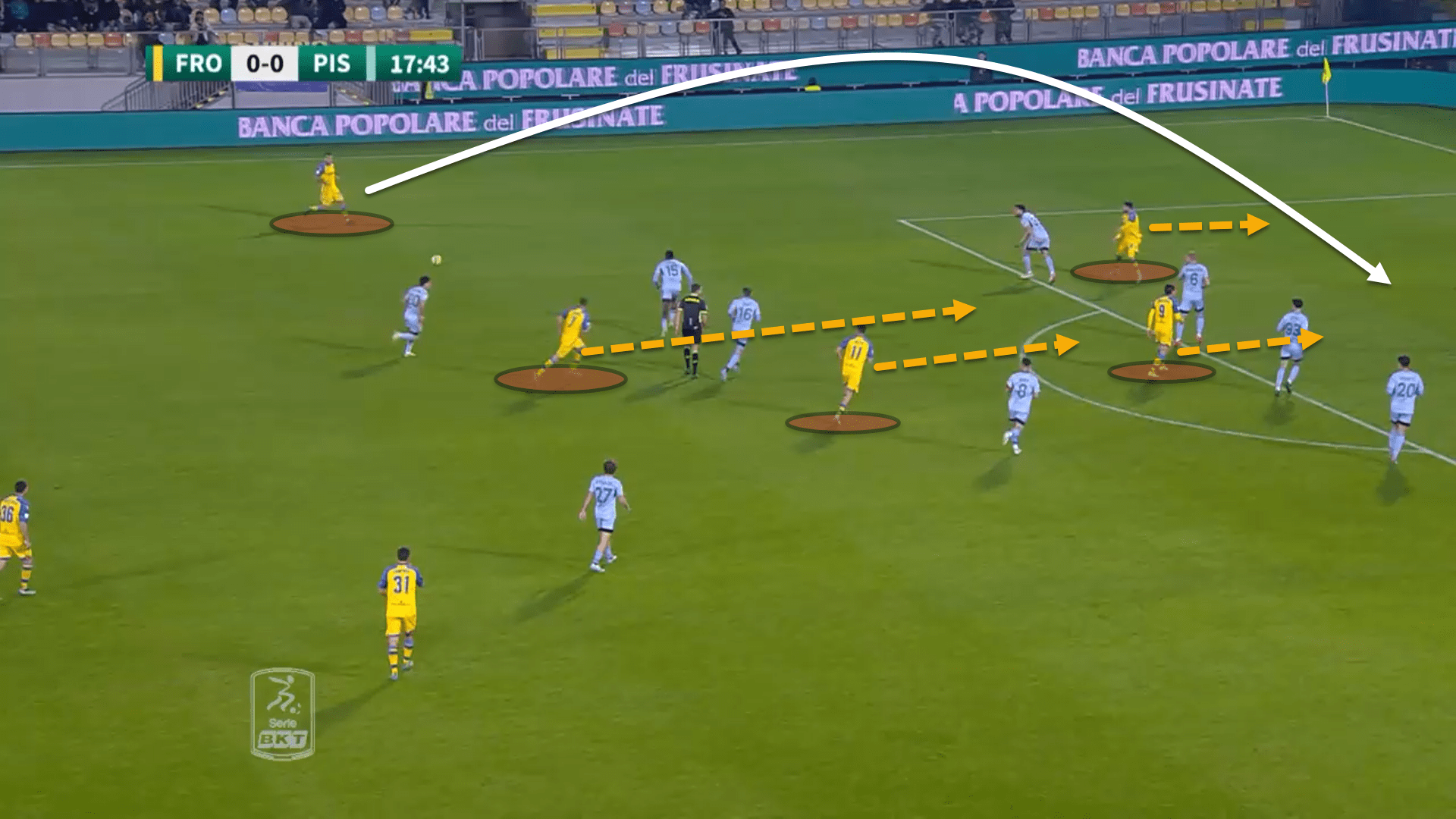

First and foremost, the Canaries overload one side of the pitch. This is for the very same reason as mentioned in the previous section. The opposition will shift across to make up the numbers, leaving a player on the far side in acres of space.

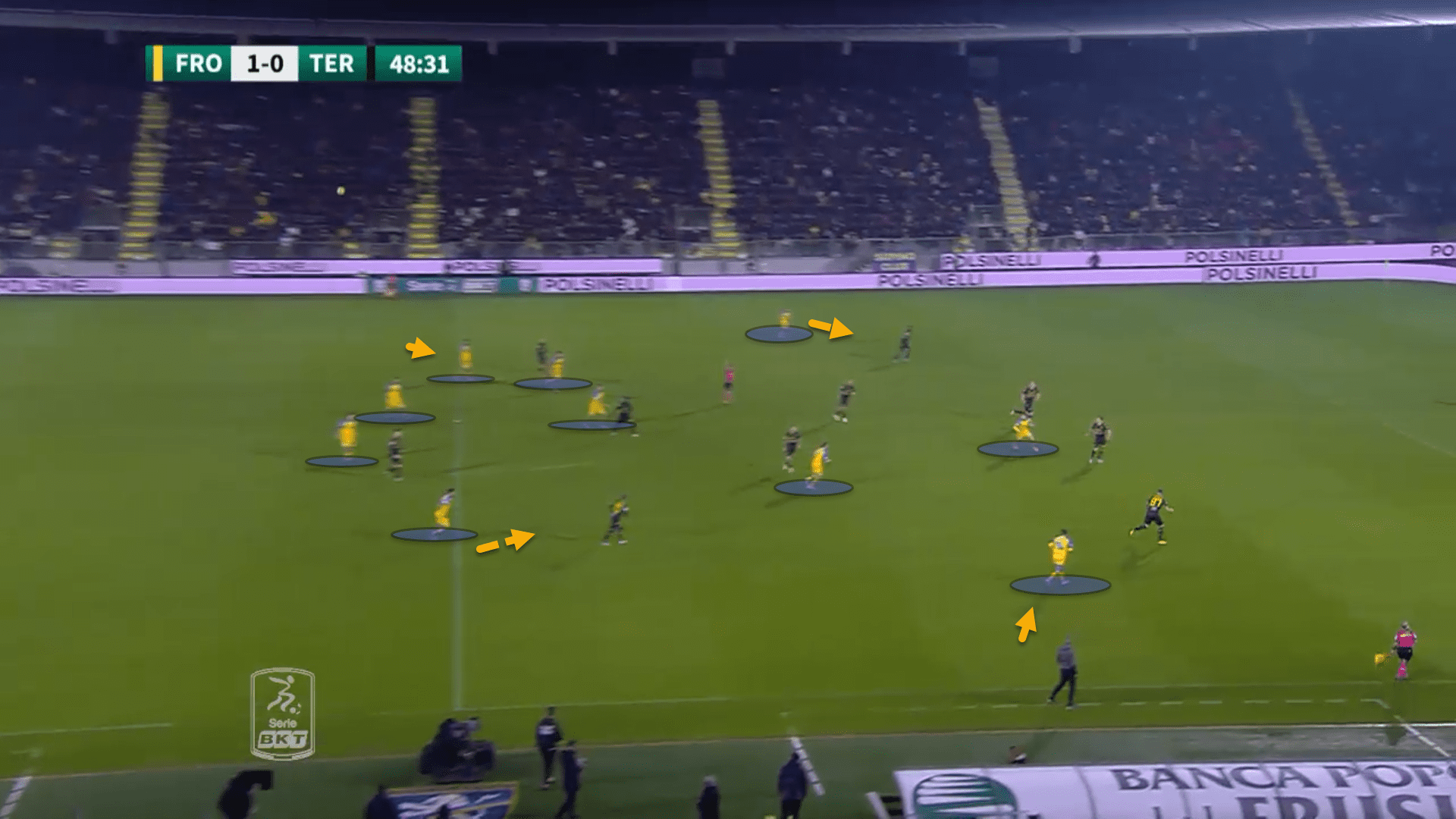

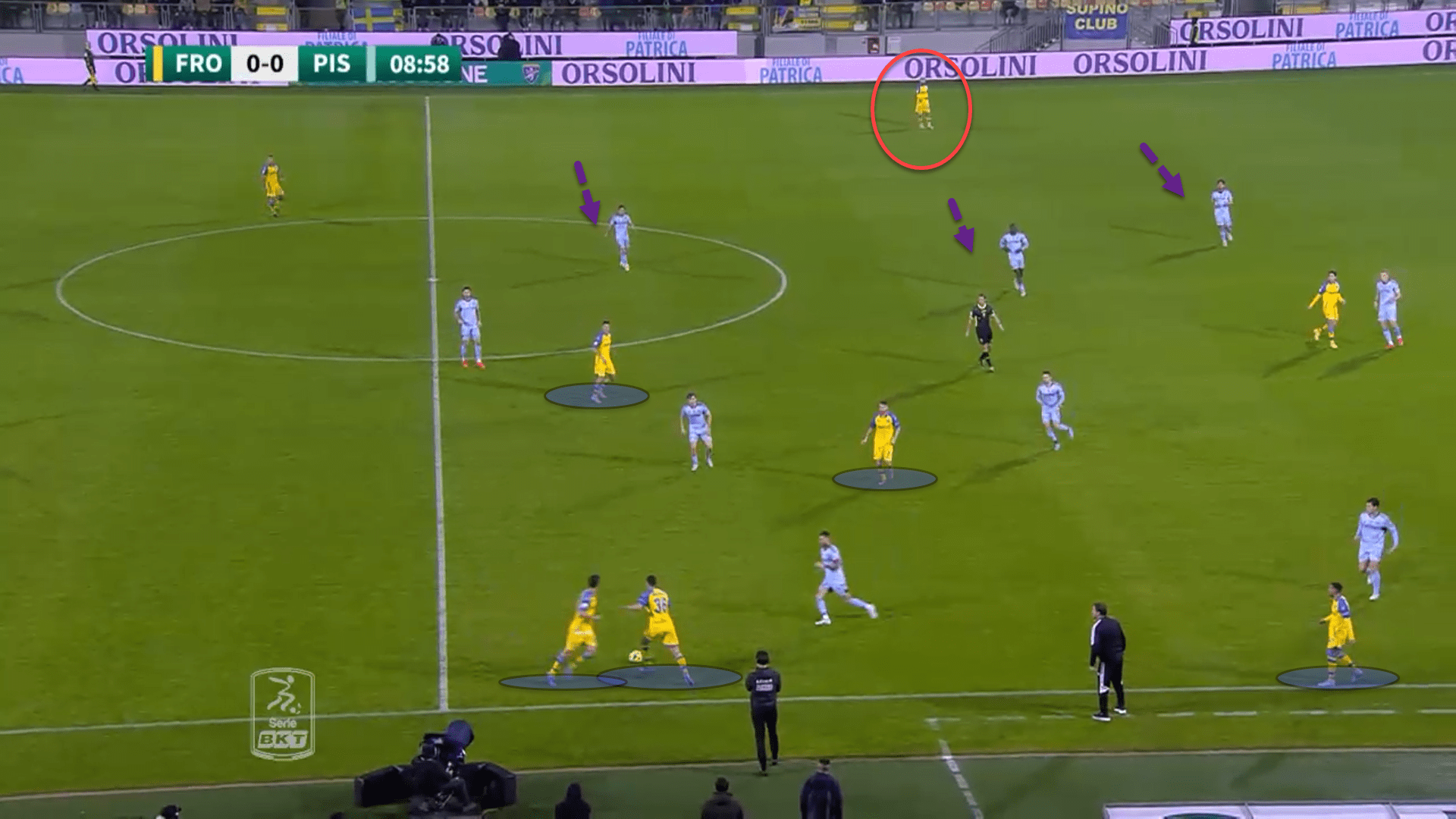

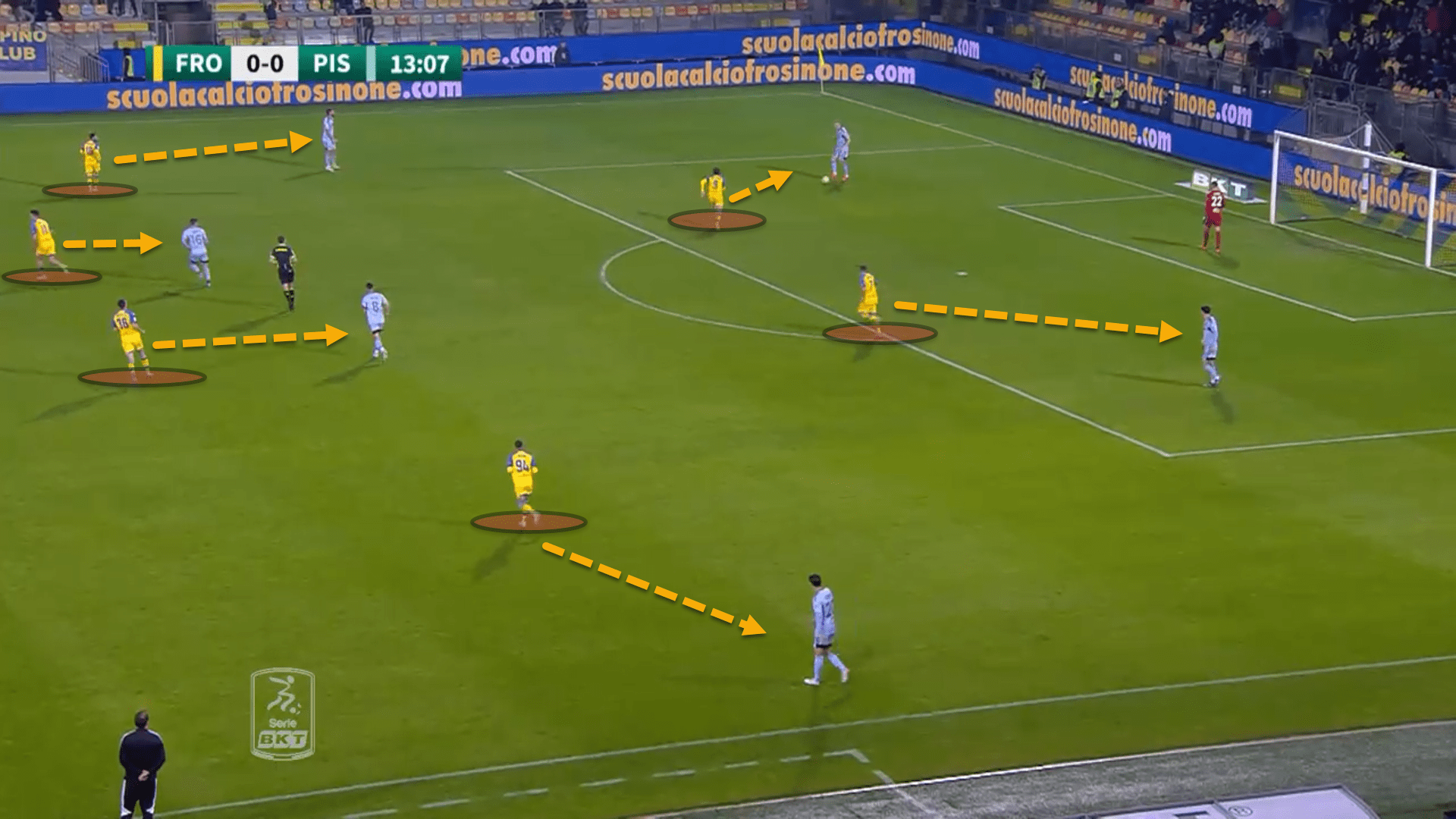

Here, we can see an example of this method in fruition. Frosinone have overloaded the right side of the pitch, causing Pisa to push their defensive block across in unison to try and ensure that they are not penetrated down this flank.

However, in doing so, there is a plethora of space over the far side for a ball to be switched to the wide player who can receive and put a cross into the penalty area against a defensive structure desperately trying to recover their shape.

Normally, from these positions, coaches will instruct the wide player, who has received from the switch, to run at the opposition’s full-back in a 1v1 situation before delivering a ball into the box.

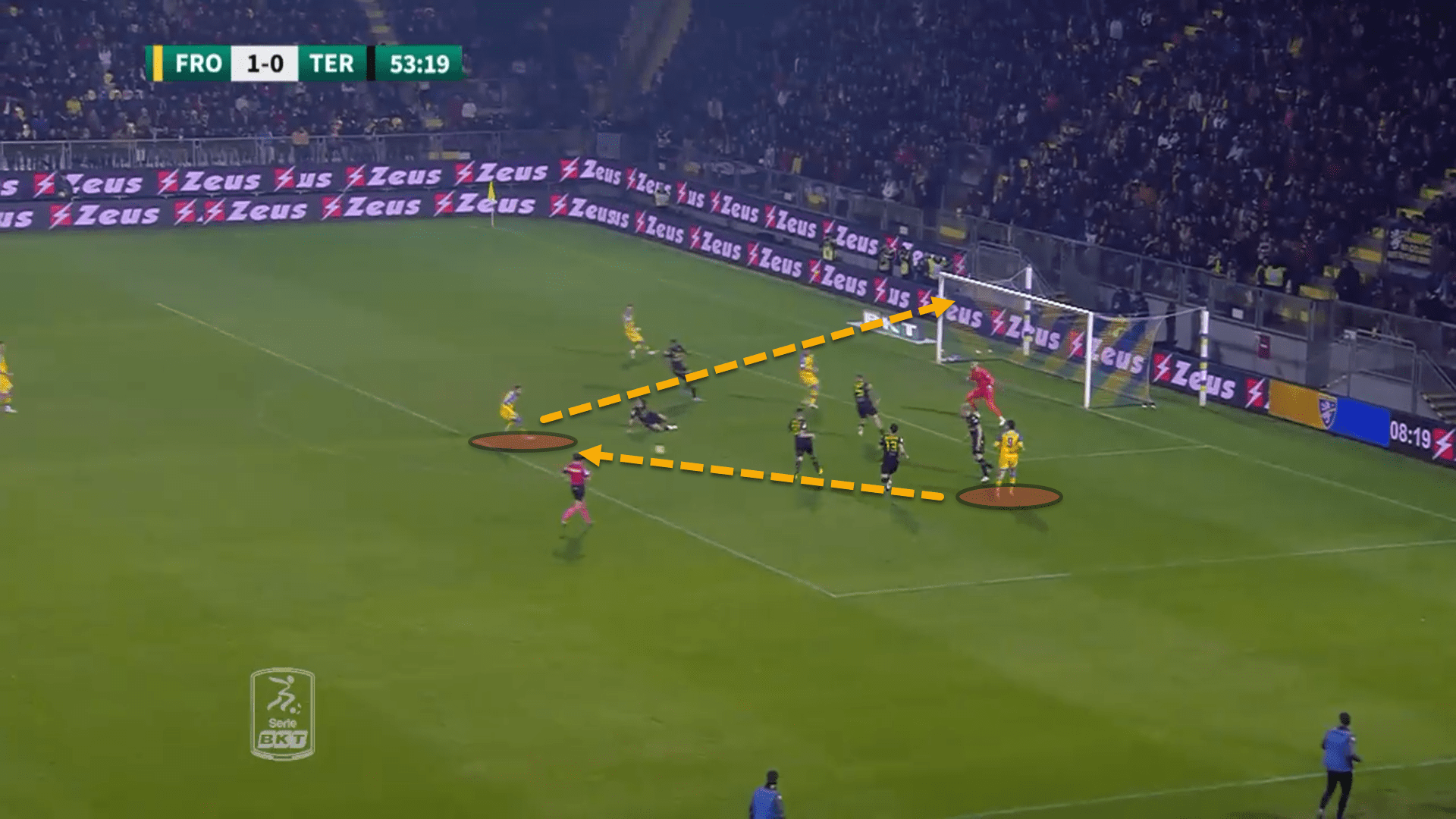

Grosso’s approach is a little different. The Frosinone head coach prefers his players to play outswinging balls into the mixer from lower positions, with plenty of players attacking the 18-yard box to get onto the end of these crosses.

Outswinging crosses make it more difficult for the goalkeeper to judge the trajectory of the ball as the ball moves away from the shot-stopper and so Grosso feels as though they are the best method to creating goalscoring chances from the wide areas rather than getting to the byline or cutting inside and whipping it in.

This season, Frosinone have played 17.23 crosses per game in total in all competitions, boasting a decent accuracy of 34%.

Nevertheless, overloading one side of the pitch to play to another before crossing is not the only way that the Canaries have tried to create goalscoring opportunities this season.

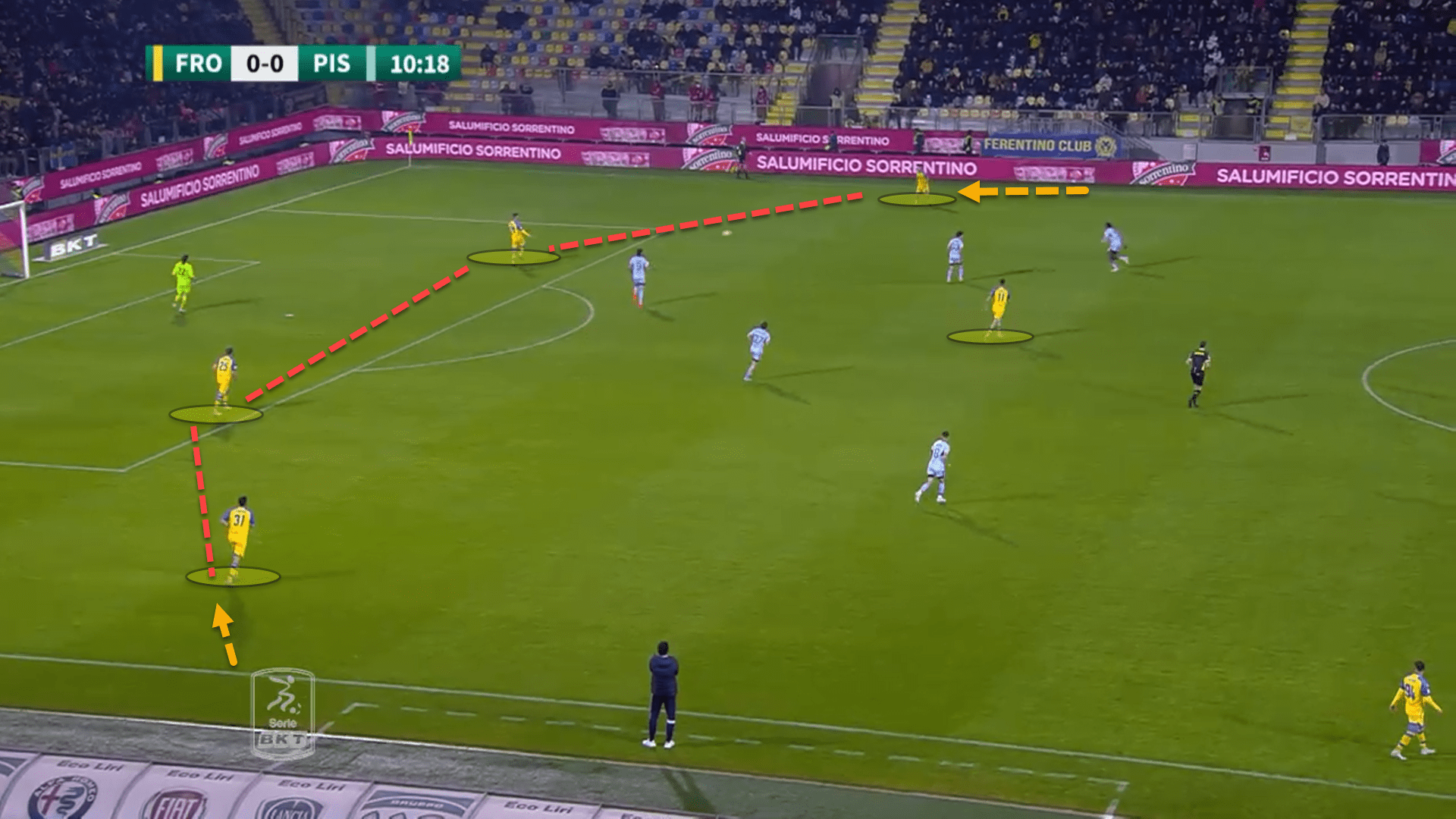

Like Allegri, Grosso emphasises runs in behind, attacking the depth of the pitch whenever possible to stretch the opposition’s lines and create space, or to take advantage of space beyond the defensive line.

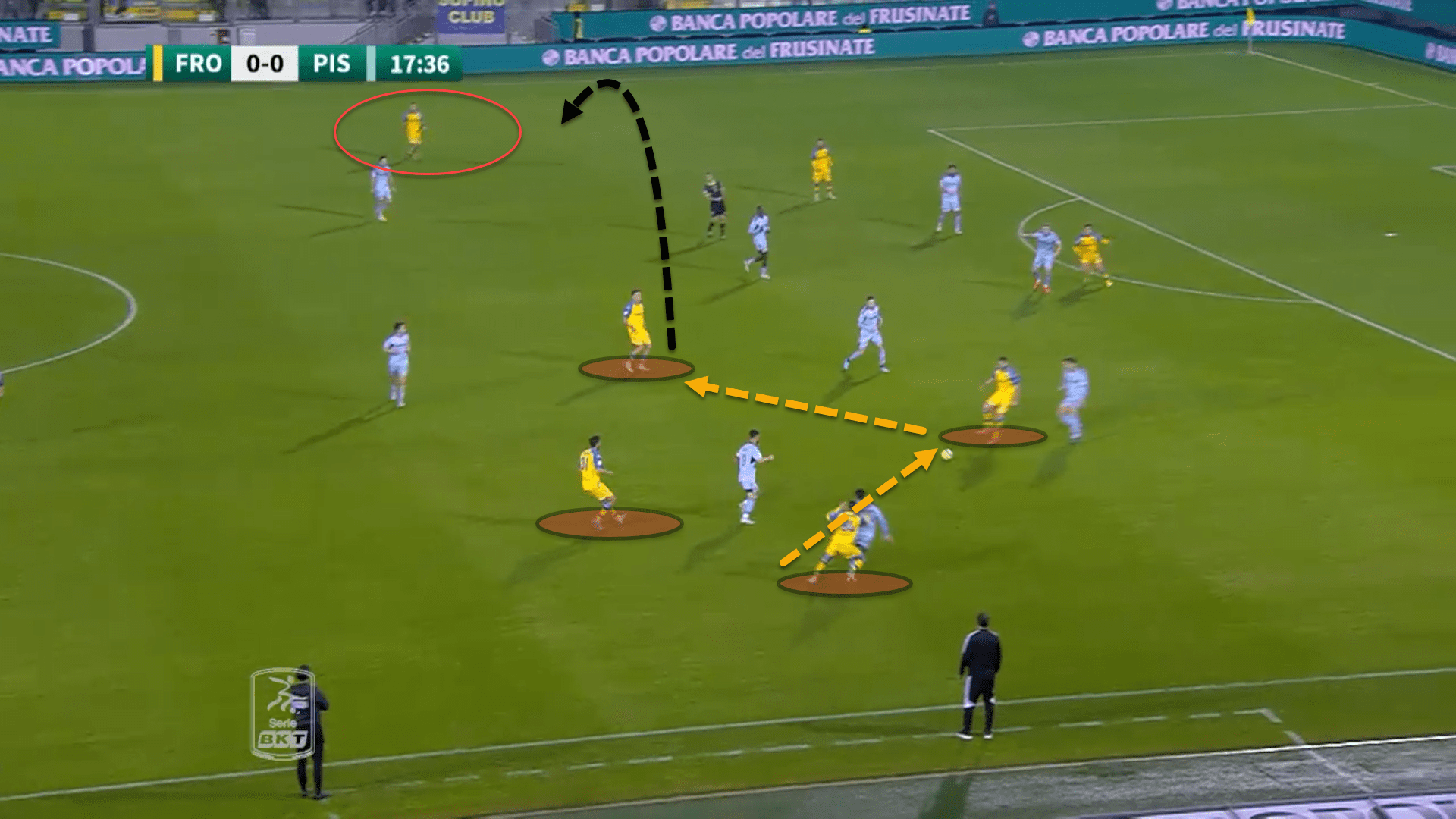

Here, the forward line have made runs in behind, dragging Pisa’s backline deeper towards their own goal. This has caused the lines between Pisa’s midfield and backline to stretch and widen, allowing Frosinone’s advanced midfielders to receive between the lines on the half-turn to play forward.

While the idea is the same, Allegri prefers his central midfielders to also attack the depth, adding an extra player to the forward line to defend against. However, Grosso tends to restrict attacking runs to merely the forwards.

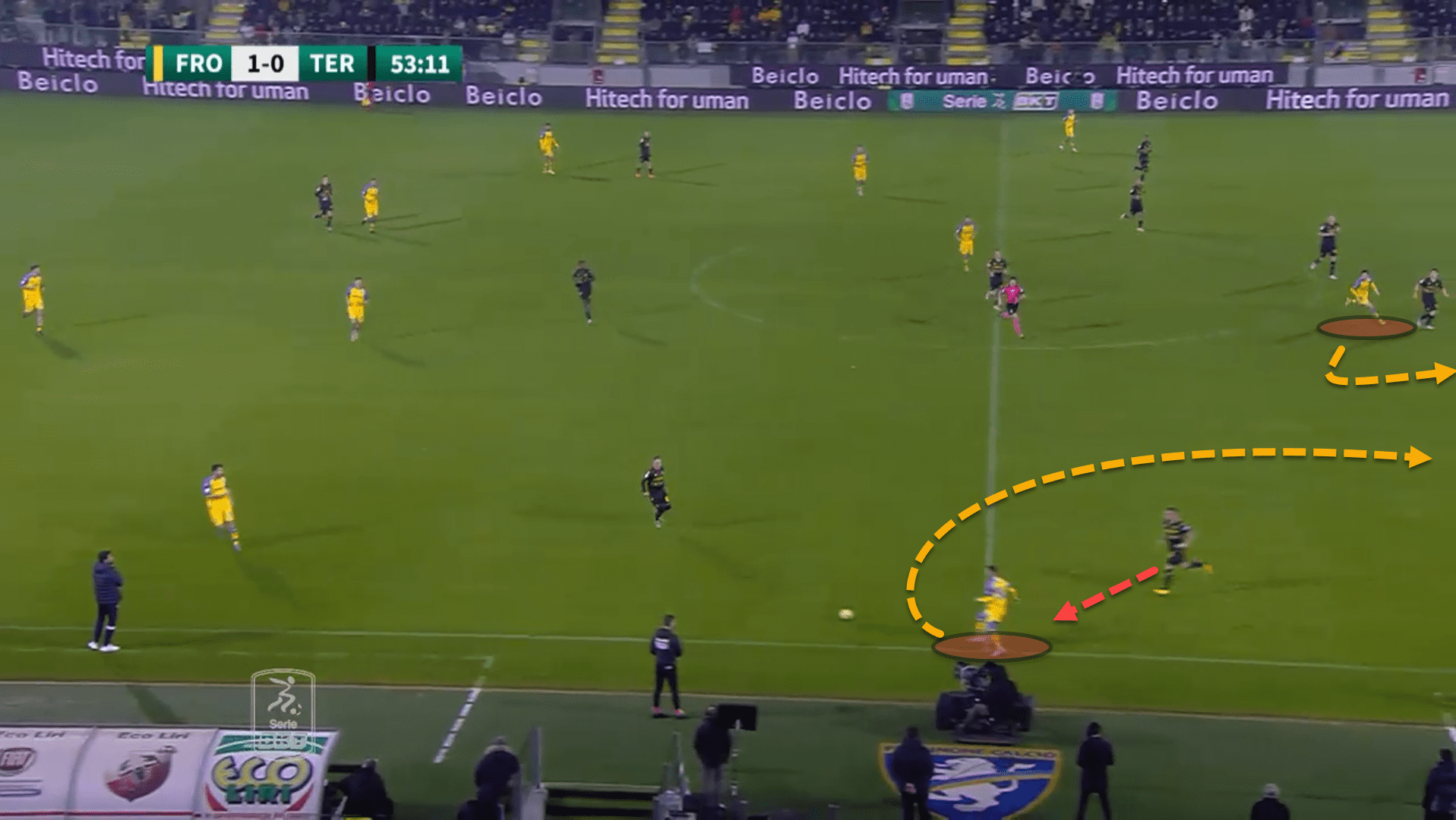

Samuele Mulattieri has often been the player tasked with leading the line. The centre-forwards need to be adept at noticing when to make the right runs to either receive in space or to aid in the creation of space which the Internazionale loanee certainly can do.

Seeing the channel open up between the opposition’s left-back and centre-back, Mulattieri quickly darted into the exploitable space to receive immediately from the winger who dropped short to receive from the backline.

Frosinone scored from this situation as Mulattieri reached the penalty area after latching onto the pass into the channel, before crossing for his teammate to place the ball home.

This attacking variety in the final third has made Frosinone one of the most exciting sides in Serie B this season and the third-highest goalscorers as of writing. This is certainly impressive, but Frosinone’s defensive record is even more awe-inspiring.

Defensive phase

As of right now, Frosinone have conceded 12 goals in Serie B in 20 matches, conceding 0.8 goals per game which is the best in Italy’s second tier.

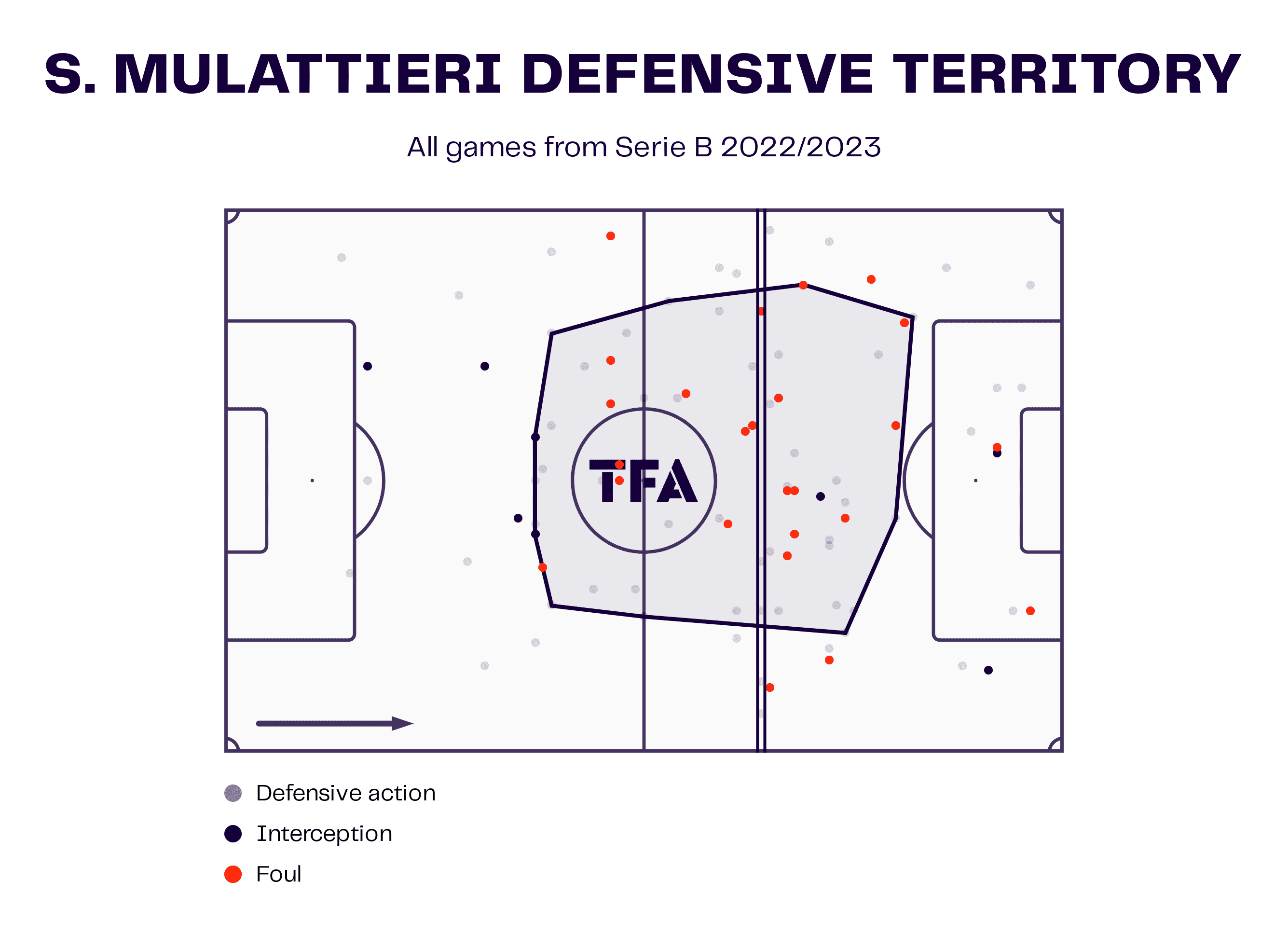

What’s even more interesting with regard to this excellent record is that the Canaries don’t actually press that high up the pitch. This can be seen from Mulattieri’s average defensive line height throughout the Serie B campaign.

The centre-forward is the first defender in a team and is given the responsibility to lead the press for his side. Nonetheless, Mulattieri hasn’t really had this issue as Frosinone’s line of engagement is very low down the pitch, closer to the halfway line than their own penalty area on average.

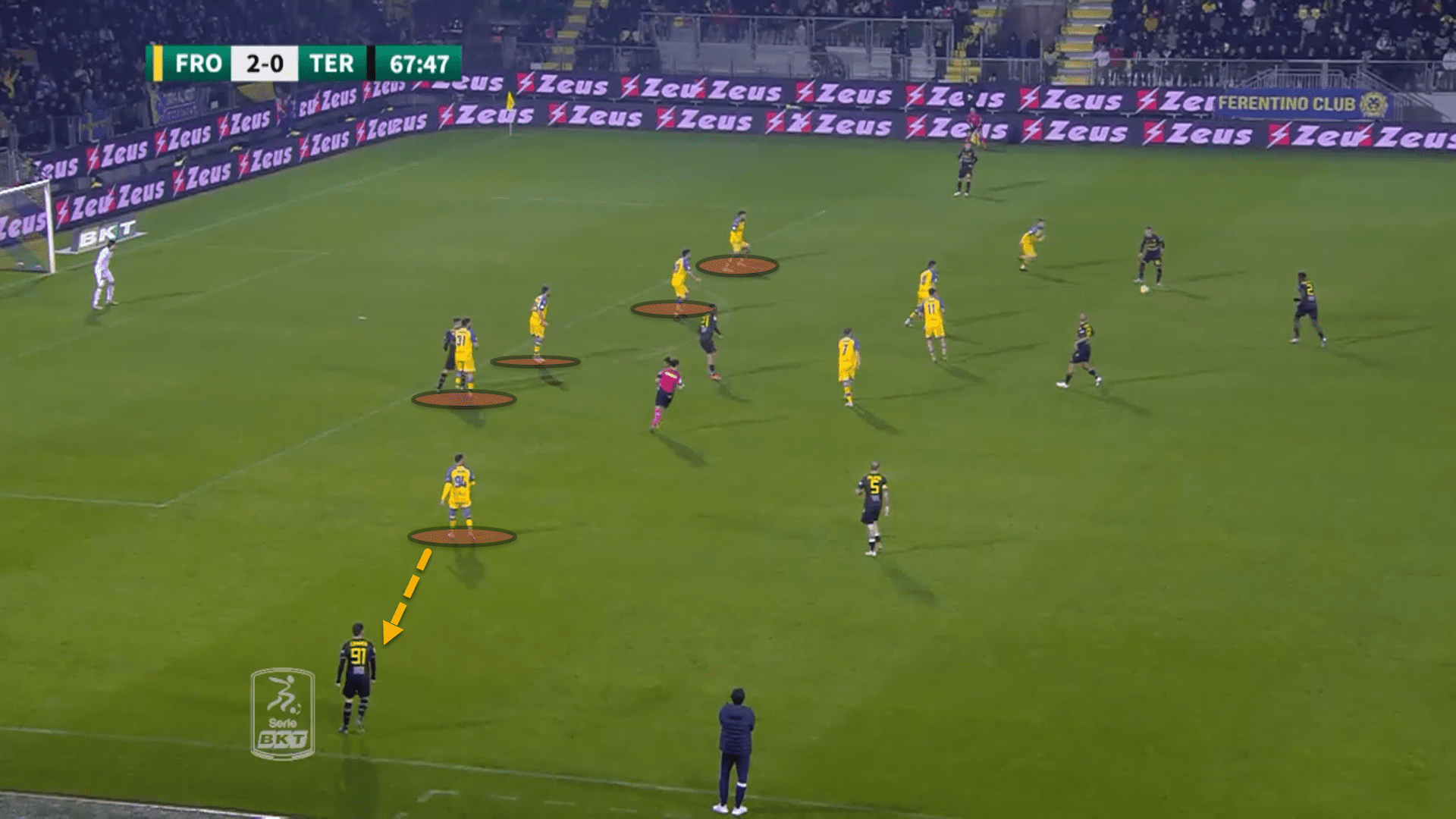

Grosso doesn’t want to risk his backline being exposed if Frosinone’s high-pressing scheme is broken as many players will be out of position. Instead, the team drop lower into a compact block and allow the opposition to progress from their own third completely unscathed.

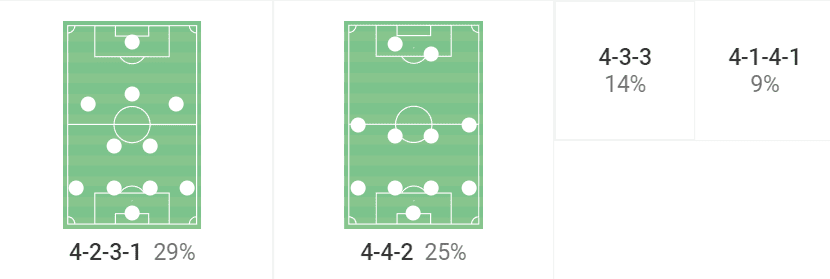

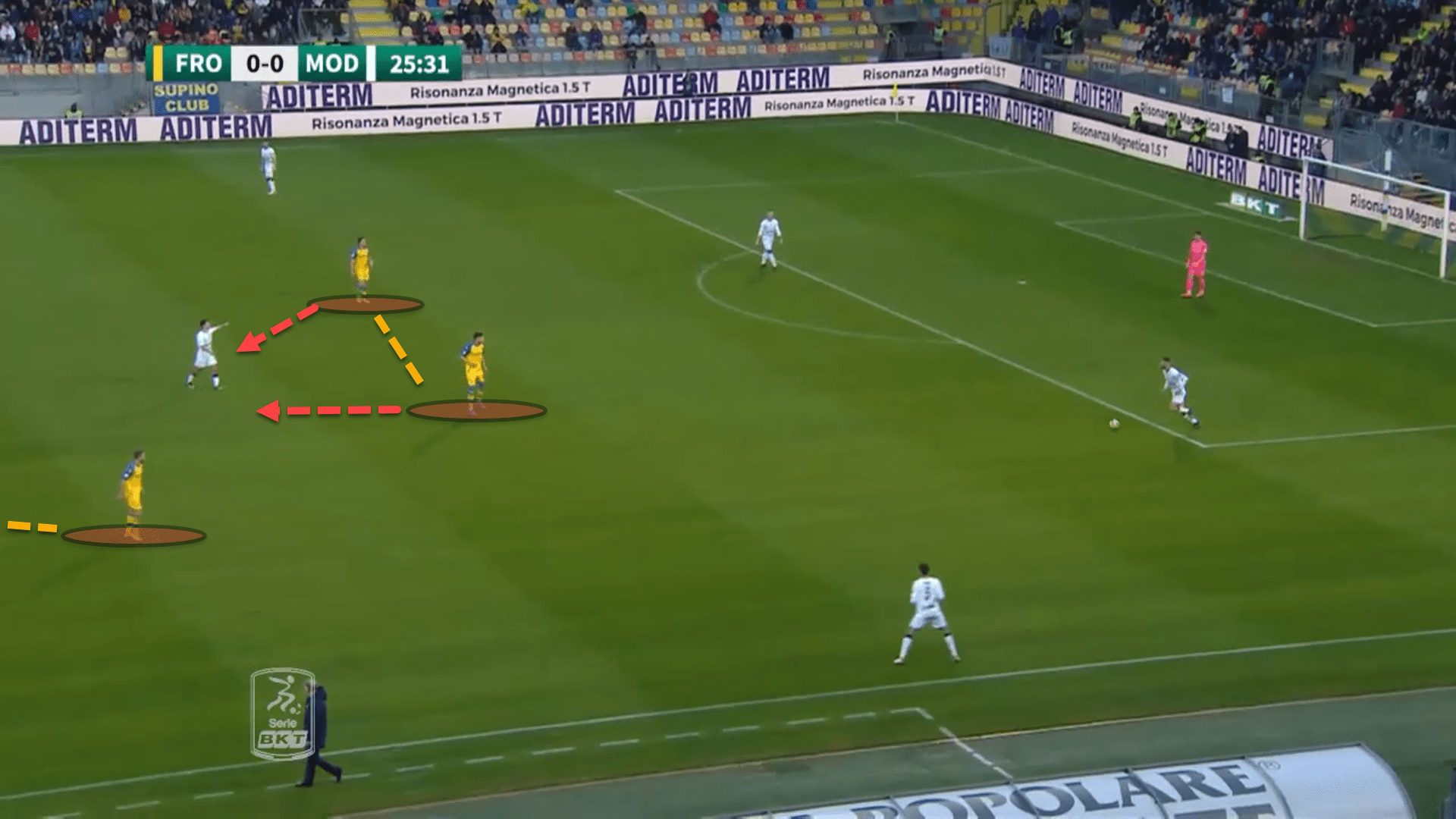

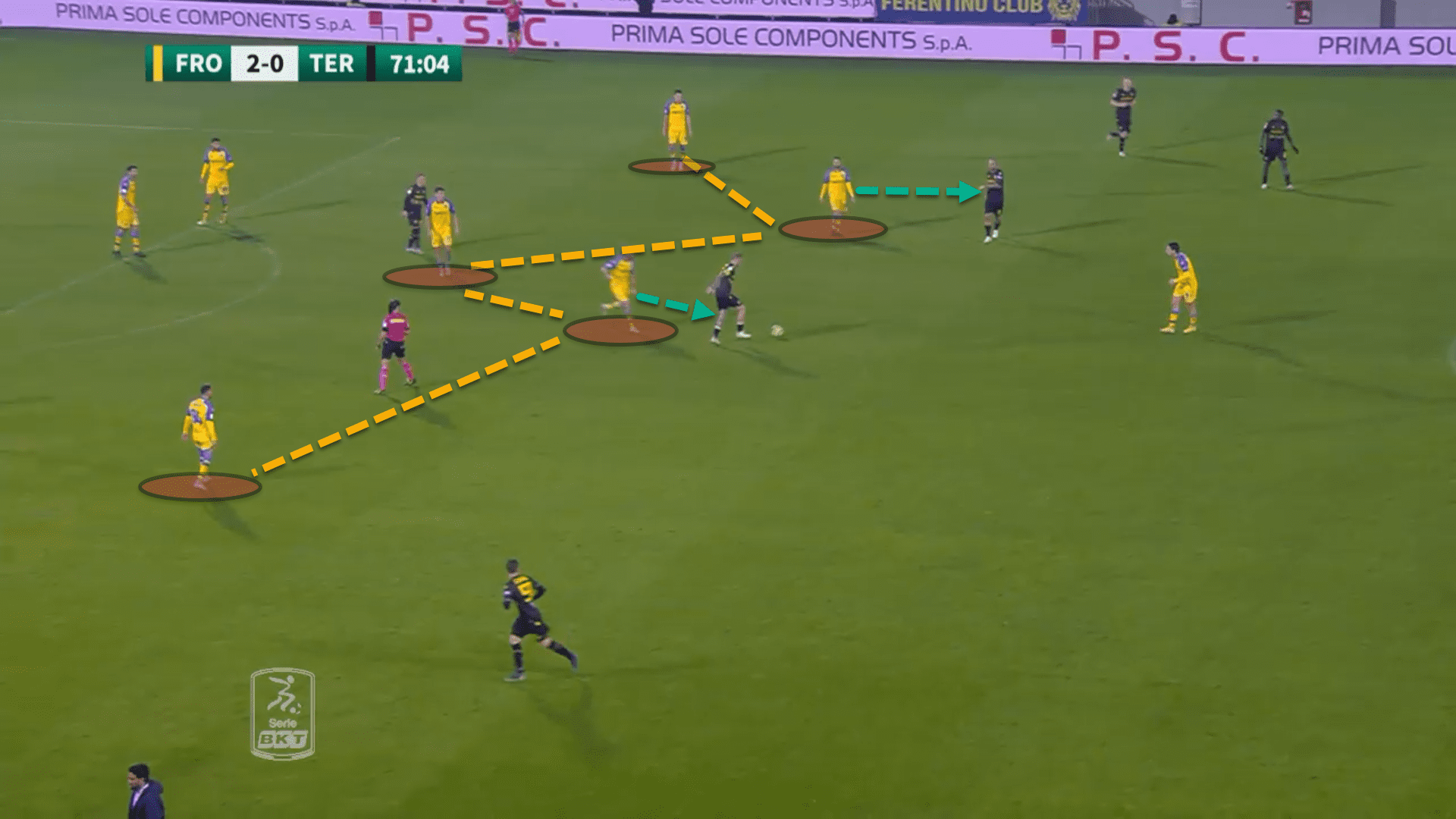

In this example, Modena are building out from the back, but the four defenders are unchallenged when circulating the ball around. Frosinone have opted to drop off into a 5-3-2 mid-block in the middle third of the pitch.

Grosso doesn’t want his players to engage too high up the pitch and so, generally, Frosinone don’t. However, there are times when pressing as a unit in a high block is allowed by the coach. When these situations occur, the Canaries press in a man-oriented fashion.

For the most part, though, Frosinone defend deeper down the pitch and the approach is anything but passive.

Quite often, teams defending in deep blocks in their own third apply very little pressure to the ball carrier and instead, focus their efforts on trying to force the player on the ball to pass to a secured area of the pitch by cutting off central or progressive passing options.

Grosso isn’t keen for his team to be passive. Frosinone are incredibly intense out of possession and constantly harass the player on the ball to try and force them to make a mistimed pass or to cede possession in its entirety.

Given that Grosso’s preferred formation in recent matches has been the 4-1-4-1 once more, the shape reverts into a 4-5-1 out of possession in the low block phase. The central midfielders in particular are extremely aggressive and always look to step forward to press any opposition players in their zones, causing the team to search for wider options.

Usually, if the attacking side have outnumbered Frosinone in the wide areas or if the nearest full-back is already occupied, Grosso instructs the closest winger to drop back into the defensive line.

This can create a temporary five-at-the-back shape and is excellent for allowing the Canaries to defend against switches of play by having a man over.

Frosinone have been excellent out of possession, conceding an xG of just 0.94 per game in all competitions as well as 9.05 shots, with merely 28.2 hitting the target.

Conclusion

To be champions, a team needs to be extremely potent at one end of the pitch and efficiently secured at the other. Frosinone have the perfect blend of these two qualities, which is a massive credit to Fabio Grosso and his coaching staff as well as the players themselves.

Frosinone have not been in Serie A since the 2018/19 campaign when Juventus won the league under Allegri. The Canaries finished second from bottom and were swiftly relegated back down to the second division where they have unsuccessfully slugged it out year after year, hoping to reach the promised land once more.

Grosso seems to finally have found the perfect formula to do so, as this analysis has shown, with the Lazio-based club sitting six points clear at the top with half the season still to go.

Comments