After coaching in Barcelona’s youth setup for nearly 16 years, García Pimienta took his first step into senior football with Las Palmas, in La Liga 2. At La Masia, the 48-year-old famously won the 2017/18 UEFA Youth League after progressing through the youth setup. However, Pimienta’s time with Barça is most notable for shaping and defining the Catalan’s tactical style. Obviously, coaching Barcelona’s youth teams required him to stay in line with the club’s philosophy and tactical identity. Now with Las Palmas, it is clear that this style of football stayed with him.

In the last decade, the evolution of Spain’s possession-based football, along with the influence of various other footballing cultures, saw the development and rise of Positional Play, or Juego de Posición (JdP). These tactics are now widely adopted in 2023, almost becoming the norm in European football. Barcelona was a key piece in the development of this style, as an organisation and with the many figures linked to the club. Curiously, the city’s layout significantly resembles some of the core ideas behind this philosophy.

At any rate, García Pimienta was in the eye of the storm. With this style of play at the core of his tactics, the 48-year-old began his work with Las Palmas. A year later, the Spanish club sits second in La Liga 2, with a serious chance of reaching promotion to La Liga for the first time in five years.

While Las Palmas’ success is definitely notable, their tactics under Pimienta have been especially interesting. This tactical analysis will take a detailed look at García Pimienta’s Las Palmas, looking at the ins and outs of their attacking system. This analysis will specifically look at how the 48-year-old has added his own twist to Juego de Posición, and why it can be so significant for the development of this style of play.

Juego de Posición

With Pep Guardiola as its figurehead, Positional Play became an established approach to possession in the late 2000s. This style of play was developed and refined throughout the 2010s, with Guardiola’s time at Bayern Munich playing a significant role. Essentially, Positional Play provides a set of spatial guidelines for possession by dividing the pitch into five vertical lanes and some horizontal ones.

A team’s possession is then carried out through numerous principles and subprinciples, which use these predetermined zones and rules as a guide. It is a complex system, and after becoming extremely popular, it went off in various directions, not all positive. Whether through inappropriate training or ill-suited squads, some teams using this approach drifted from the original idea and created an incorrect representation of Positional Play. As a consequence, the philosophy itself became a scapegoat, not the incorrect implementation of it.

García Pimienta’s time with Las Palmas has demonstrated just how pleasing and effective this approach can be. Positional Play’s criticism often tends to revolve around static possession and individual repression. Pimienta’s Juego de Posición proves the opposite, and it provides a new direction for this style to head into.

With extreme fluidity, Pimienta’s tactics represent Positional Play at its best. Additionally, it curiously contains significant aspects of an approach on the other end of the spectrum, the new Functional Play. Without further talk, let’s break down how Las Palmas play under García Pimienta.

Possession

Although there are variations, García mainly uses a 4-3-3 at Las Palmas. This structure is only a starting point, from which Pimienta’s men begin their fluid occupation of spaces. This free-flowing system does follow the JdP spatial guidelines, and it is done incredibly seamlessly.

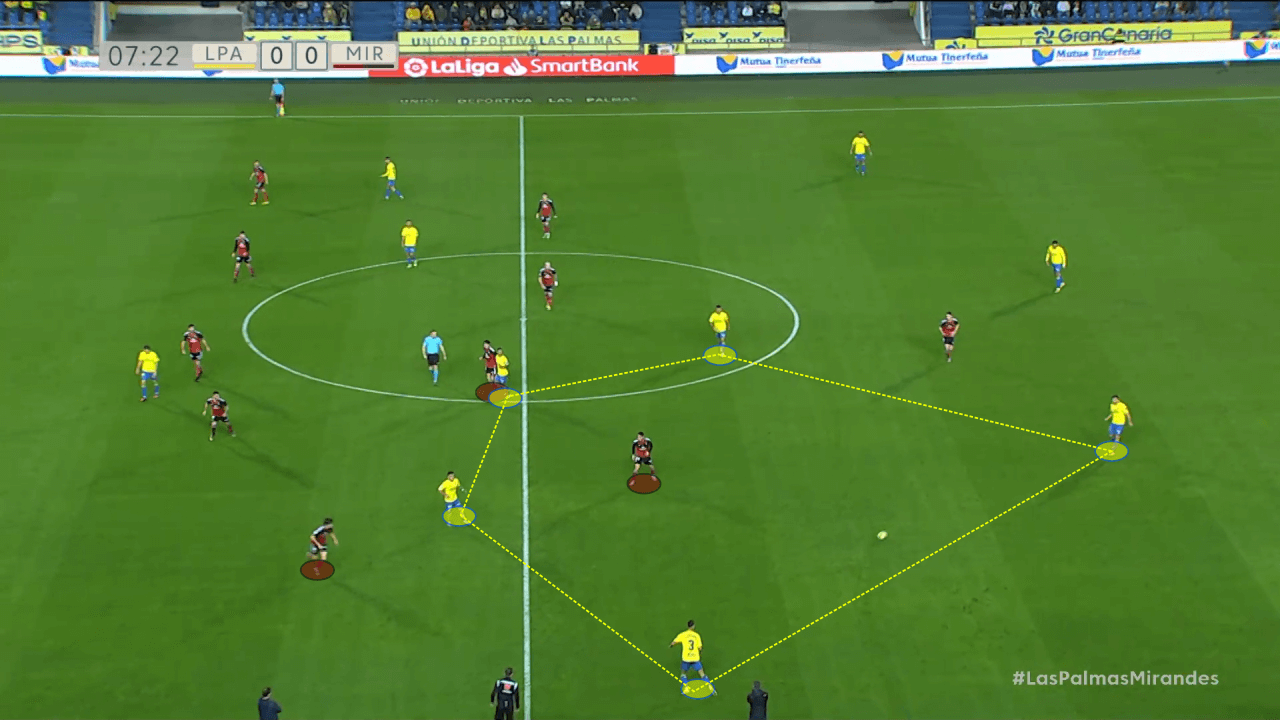

This system can be first seen in the build-up. Consistent with JdP, their structure is expansive, maximising the width on both sides simultaneously. As mentioned, the 4-3-3 distribution is the starting point. However, with the ball as a reference, zonal rotations begin emerging.

In the instance below, as the left back begins to push up in the left wing channel, the left winger drifts inside to the left half-space. As this happens, the left central midfielder pushes higher, so he is not occupying the same zone. Alberto Moleiro, the 19-year-old left winger, is perhaps the creative reference in this squad. From his initial position out wide, he often drifts into the central lanes to create.

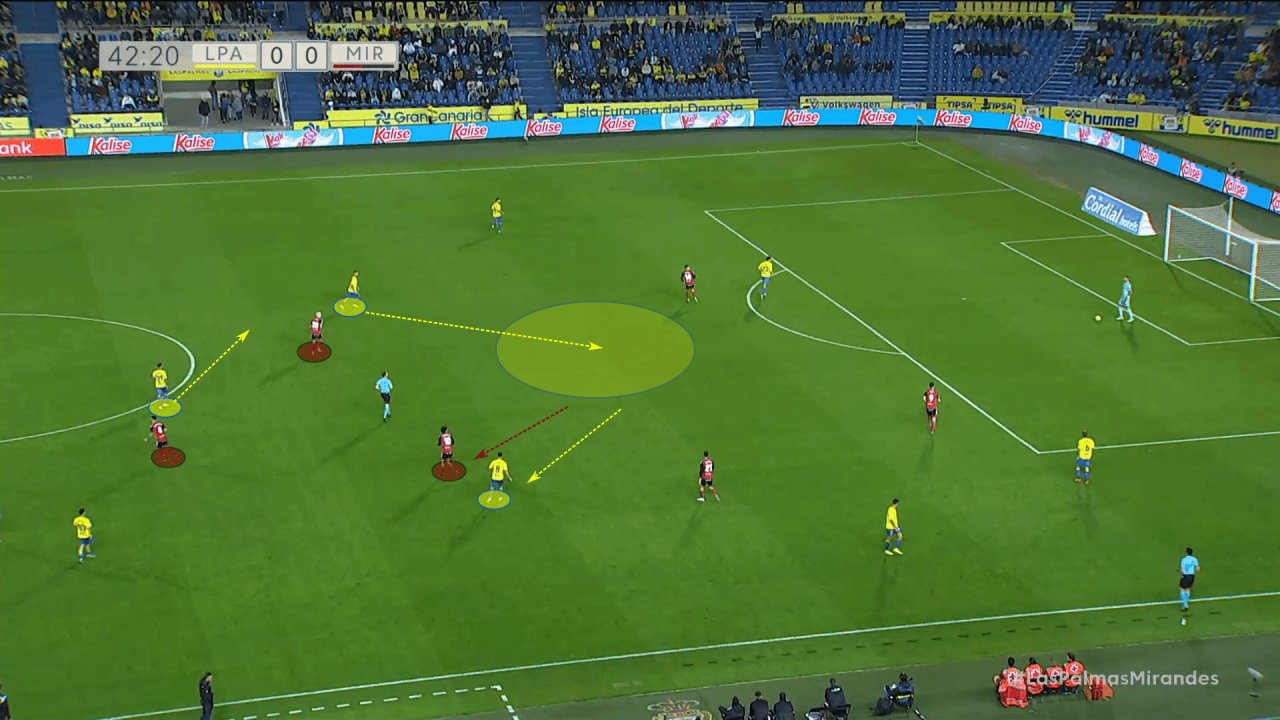

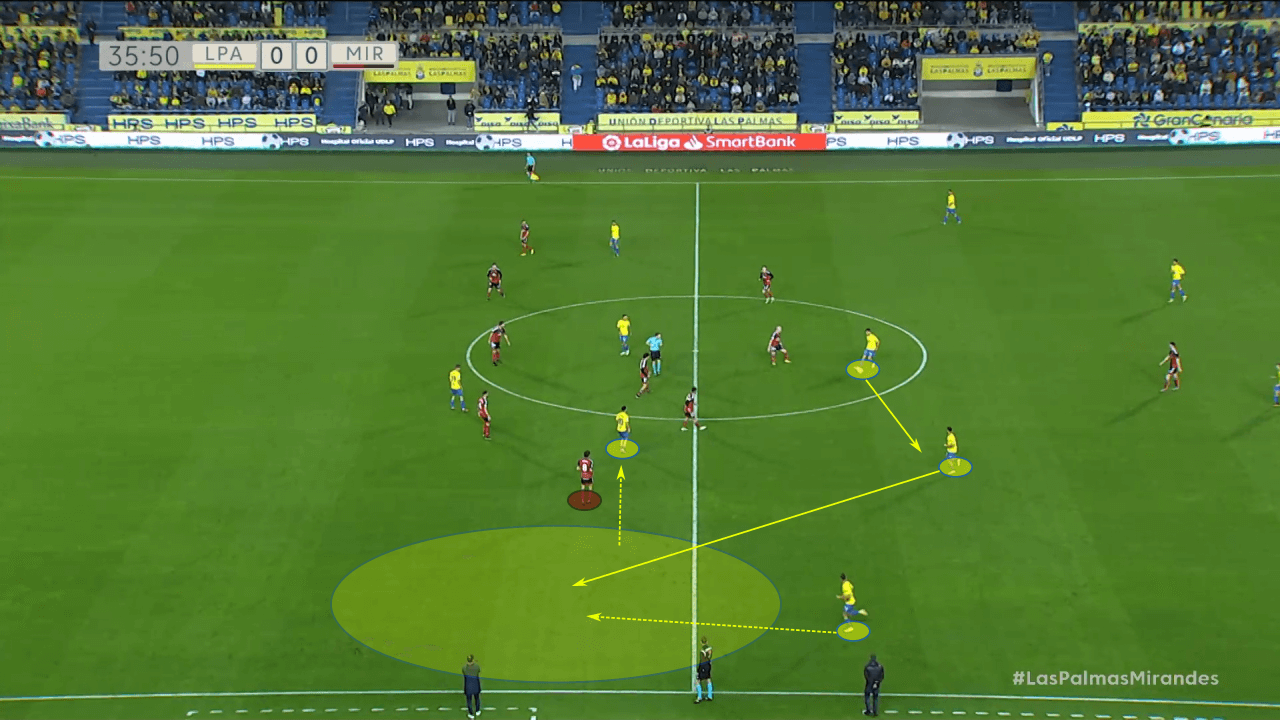

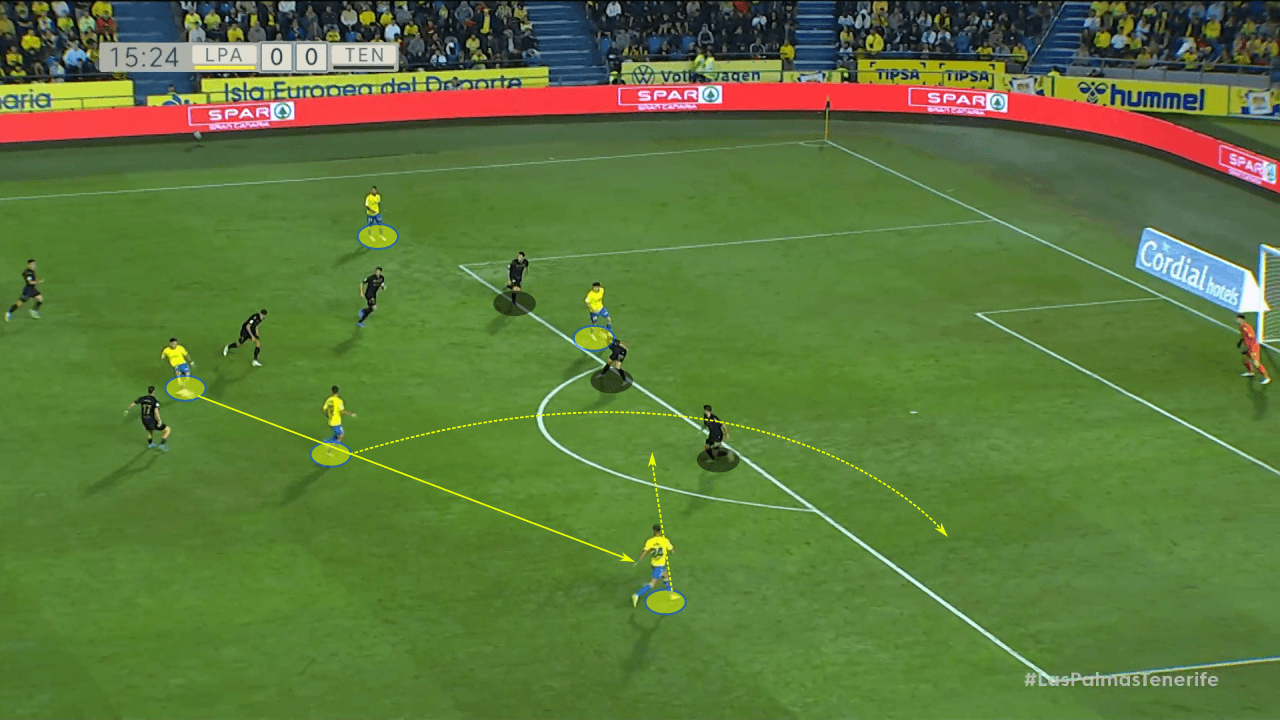

In another example, we can see how these rotations allow them to create space and progress the ball. The single pivot drifts into the left half-space, dragging his marker with him. This frees up the space previously occupied, which the right midfielder checks into.

As he does this, the left midfielder moves over to the opposite side. This constant fluid movement is responsible for creating the free man and opening up key spaces.

These subprinciples tend to create the free man, which the players are then responsible for finding. Below, their structure looks nothing like their initial 4-3-3. Nonetheless, it is still respecting the spatial guidelines of JdP. After numerous rotations, the left-back becomes the free man and essentially the way out.

There is an important hierarchy of principles in this possession model. Obviously, principles like generating the free man and creating vertical passing lanes are at the top of the list. These are carried out by subprinciples, such as positional rotations and diagonal angles. The spatial guidelines of JdP are embedded within this system of principles.

The concept of diagonal angles can be explored further through the image below. As the centre-back has possession in the left half-space, numerous players provide support. This support tends to come in the form of diagonal passing lanes. The defensive midfielder and the left-back provide immediate angles to each vertical lane. The left winger and left midfielder provide further angles up the pitch.

Maintaining maximum width can be seen as another important principle, and it is a tool that often allows them to progress into the final third. In the example below, the left winger once again comes inside and drags the fullback with him. This leaves the left back with a wide open lane on the wing, which is explored after a sequence of passes.

This width tends to be maintained by only one player, often the fullback. However, the occupation of these spaces is free for any player to occupy, as long as a balance is kept.

Statistically, there are a few trends which further characterise this Las Palmas side. They are undeniably a possession-based side, but dominating possession is a tool, not the style itself. Retaining possession and constantly circulating the ball allows them to carry out their Positional Play system much more effectively.

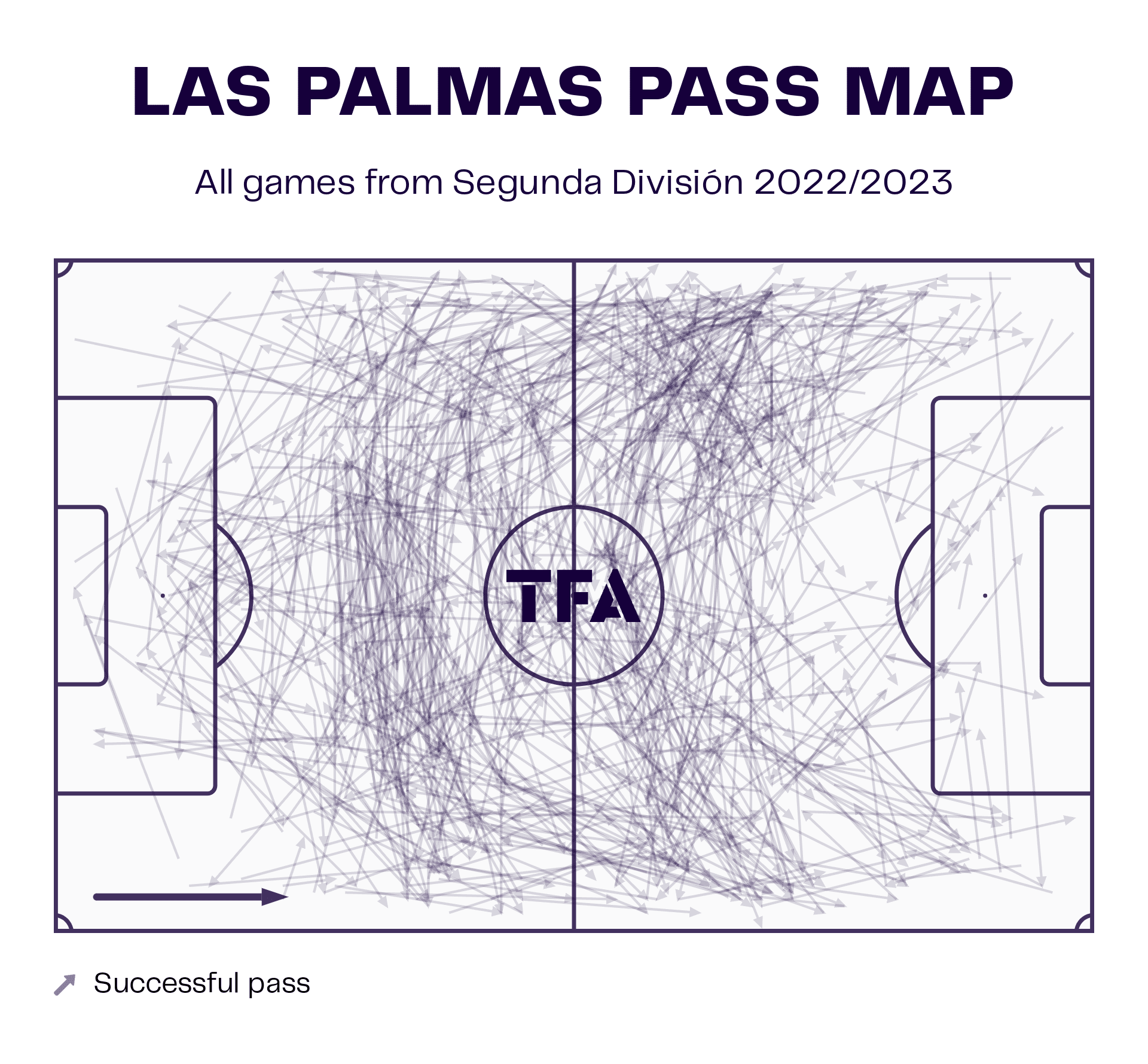

This season, they average 63.7% possession, the second-highest in the league. They also have the highest passing rate in the league, with 15.3 passes per minute of possession. Their 34.74 long passes per 90 are the lowest in the league, further highlighting their controlled approach to possession.

Their pass map this season clearly highlights this. Their 511.59 passes per 90 are the second-highest in the league, and the majority of these come just outside the middle and the final third. It highlights those patient periods of time where they circulate from side to side as they organise and execute their system.

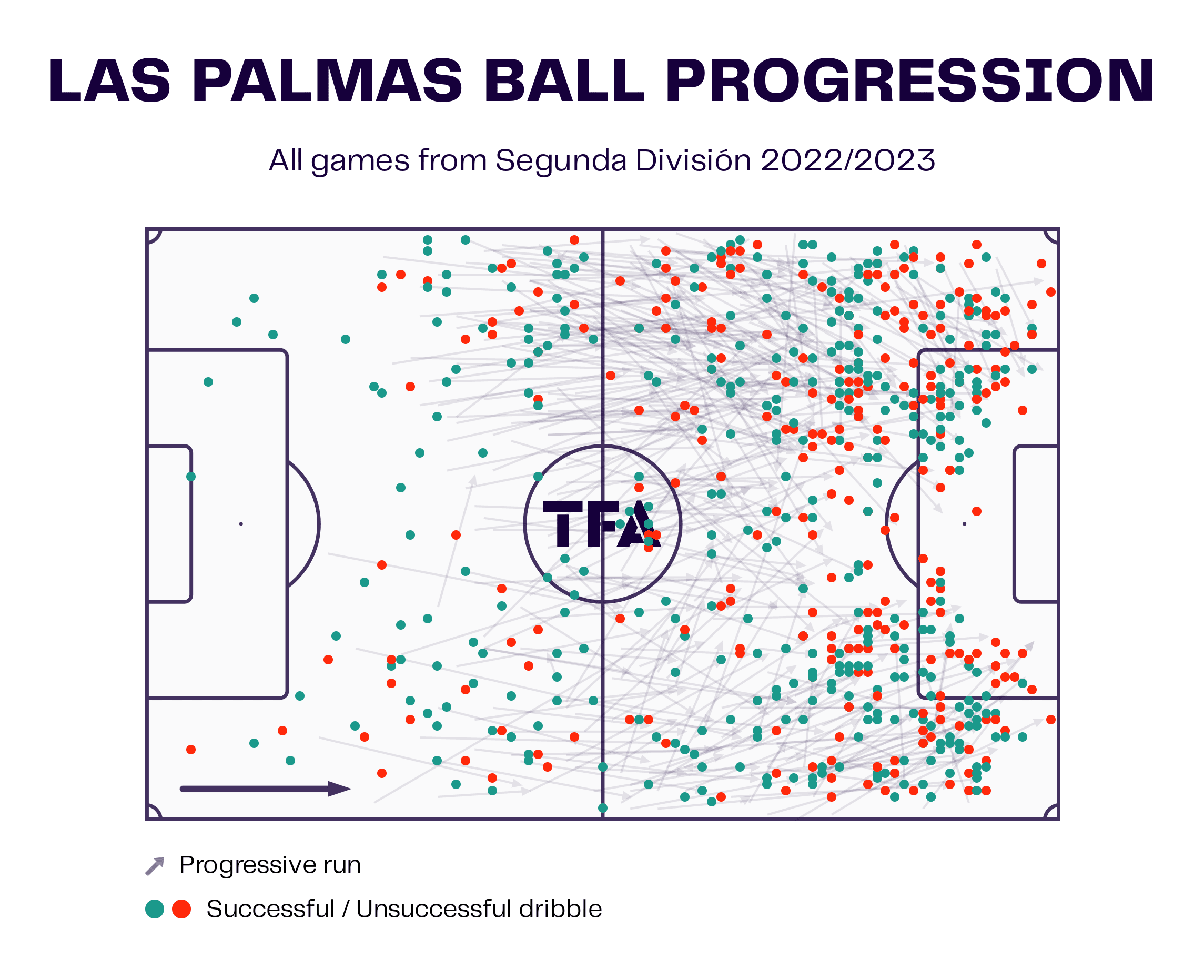

There are a few more metrics worth noting. They are first in shots per 90 (12.77) and touches in the penalty area per 90 (17.41), highlighting their ability to dominate the game and create a lot of chances. Additionally, they rank first for 1v1s and dribbling, with 30.83 per 90. Their ball progression map illustrates this. To occupy the spaces freed up or make an opponent commit and create a free man, players often resort to carries and dribbling.

Chance creation

As they progress into the final third, they resort to similar principles to break down the opposition. It all starts with width, once again. Guardiola’s famous 3-2-5 or 2-3-5 can be seen at times, but it is far from the same.

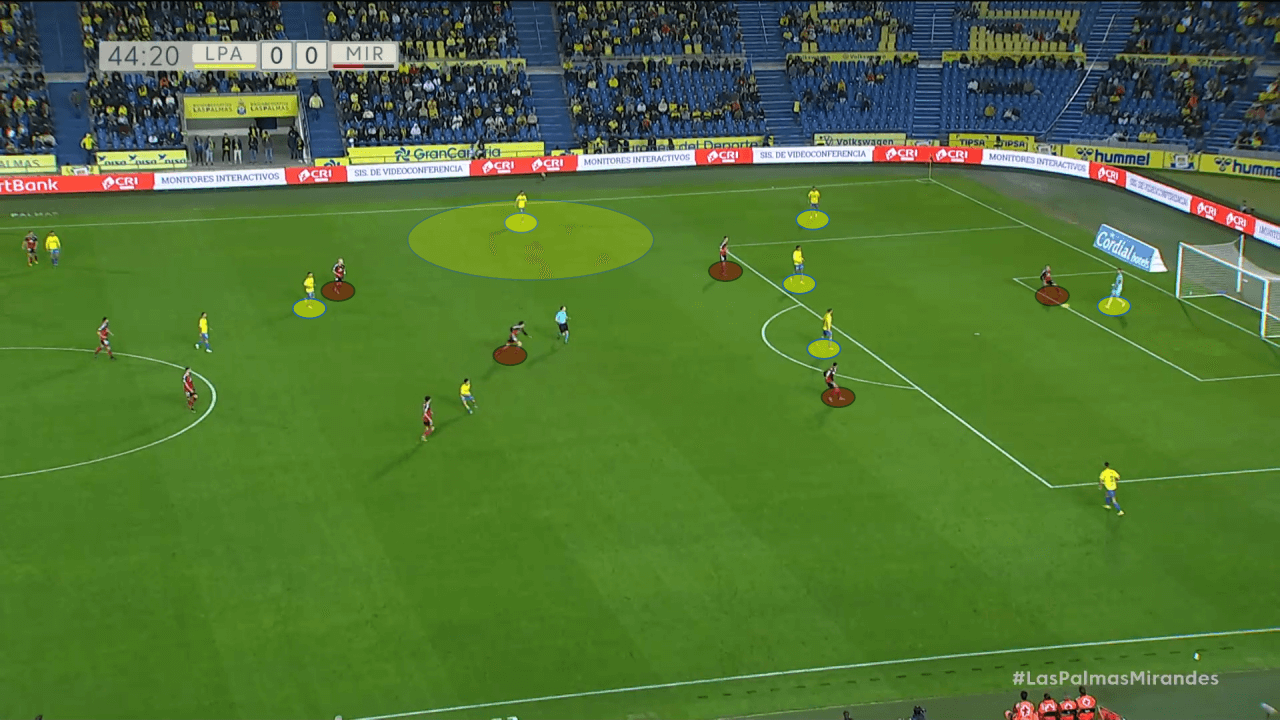

The two wide players can, at times, be rather static with the mere purpose of stretching the opposition. In the central lanes, however, players are flowing in and out of zones. Some will attack the space behind while others will drop into the midfield. As before, zonal rotations are key.

This maximum width stretches the defensive organisation and creates passing lanes for them to play through, and the positional rotations inside create gaps to exploit.

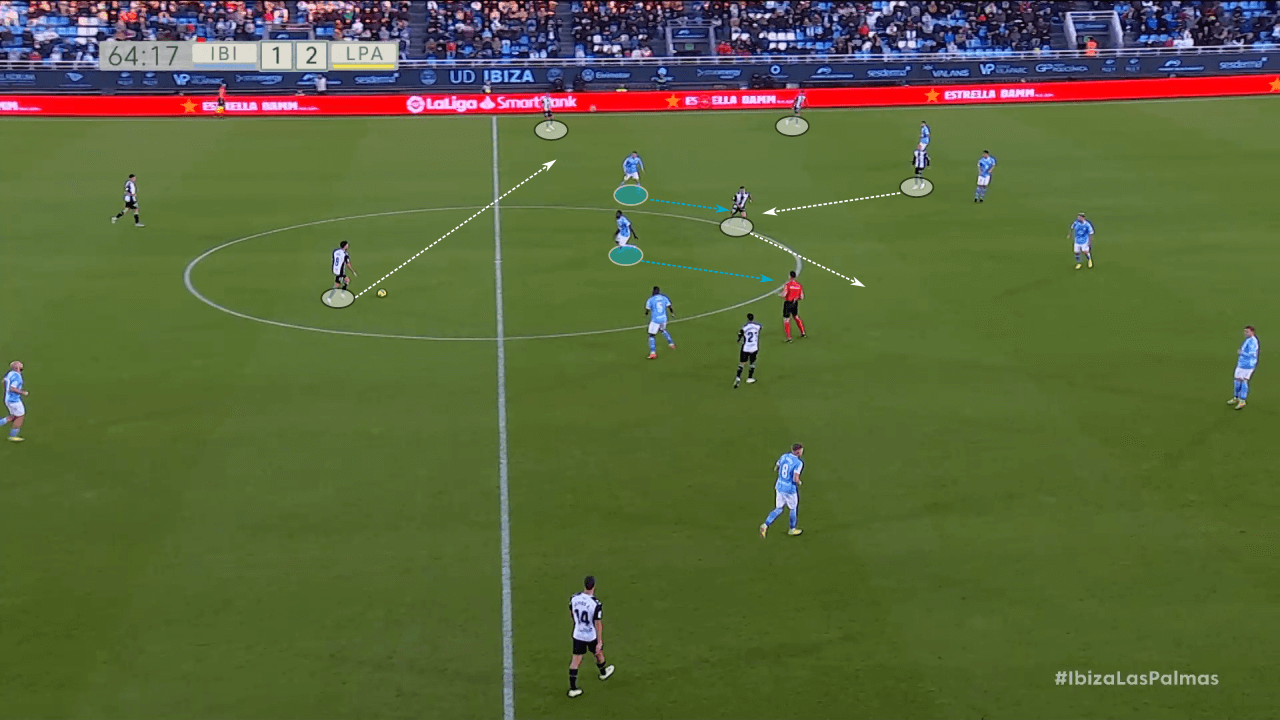

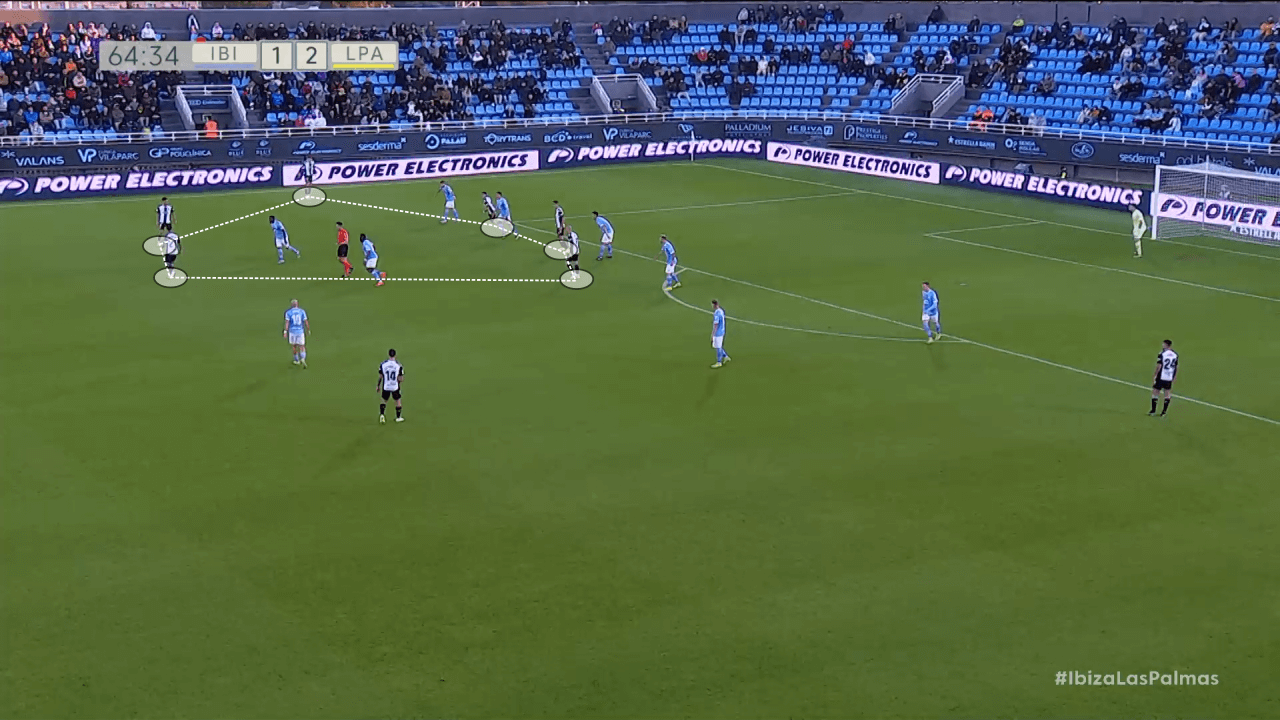

These rotations and their effect can be seen in the example below. The left midfielder makes an inwards diagonal run for the ball carrier, which sets off a chain reaction. The opposition’s right central midfielder follows him, and Las Palmas’ striker checks into the space left behind. The opposition’s right midfielder steps inside to mark him.

These movements create a distraction and drag the defensive block further inside. The ball is played out wide to the left-back, who is in a dangerous 2v1 situation.

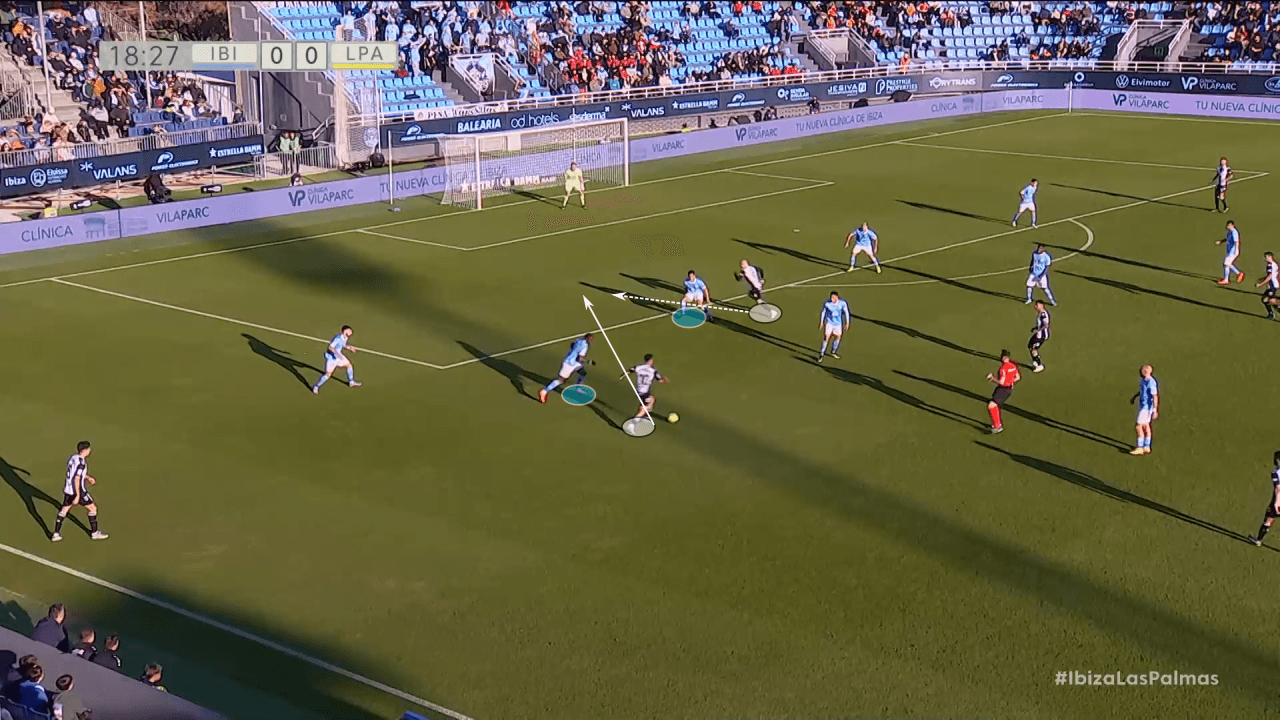

Pimienta’s men rank first for through balls in the league, with 6.79 per 90. With the backline stretched, there is more space for these through balls to be made. In the instance below, the striker makes a diagonal run behind the backline, and the left winger who is cutting inside is able to make that through pass.

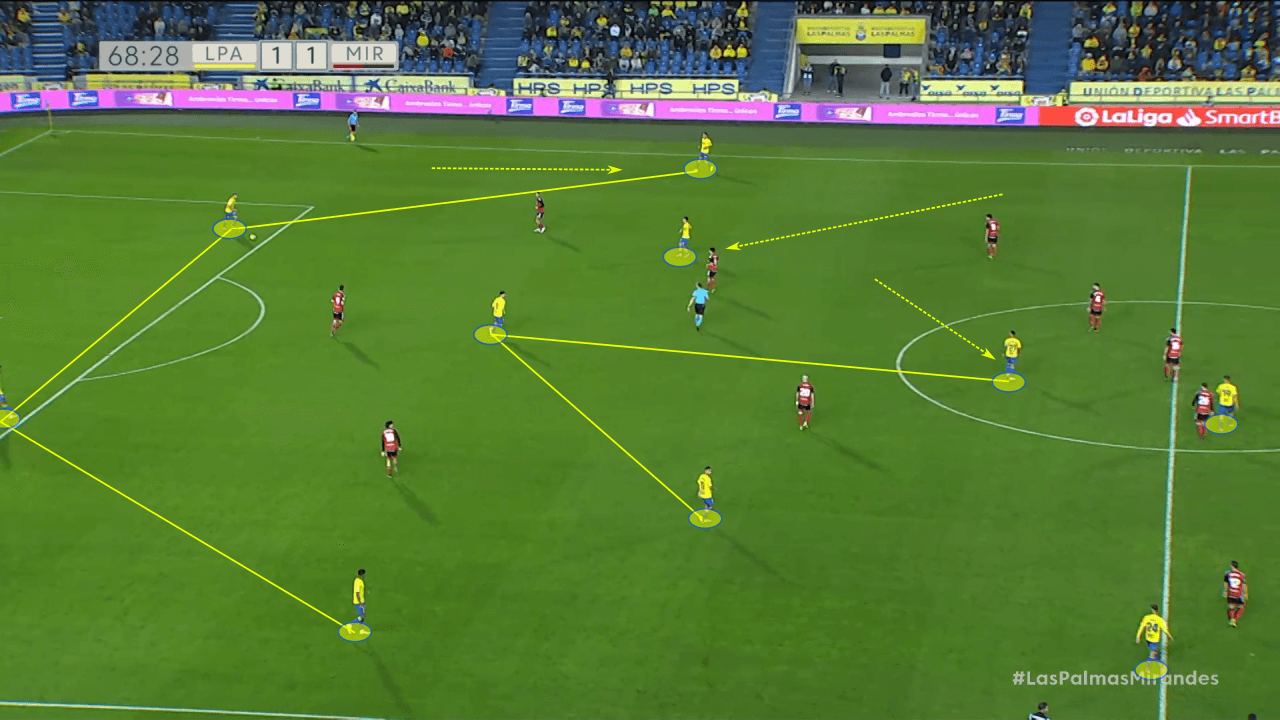

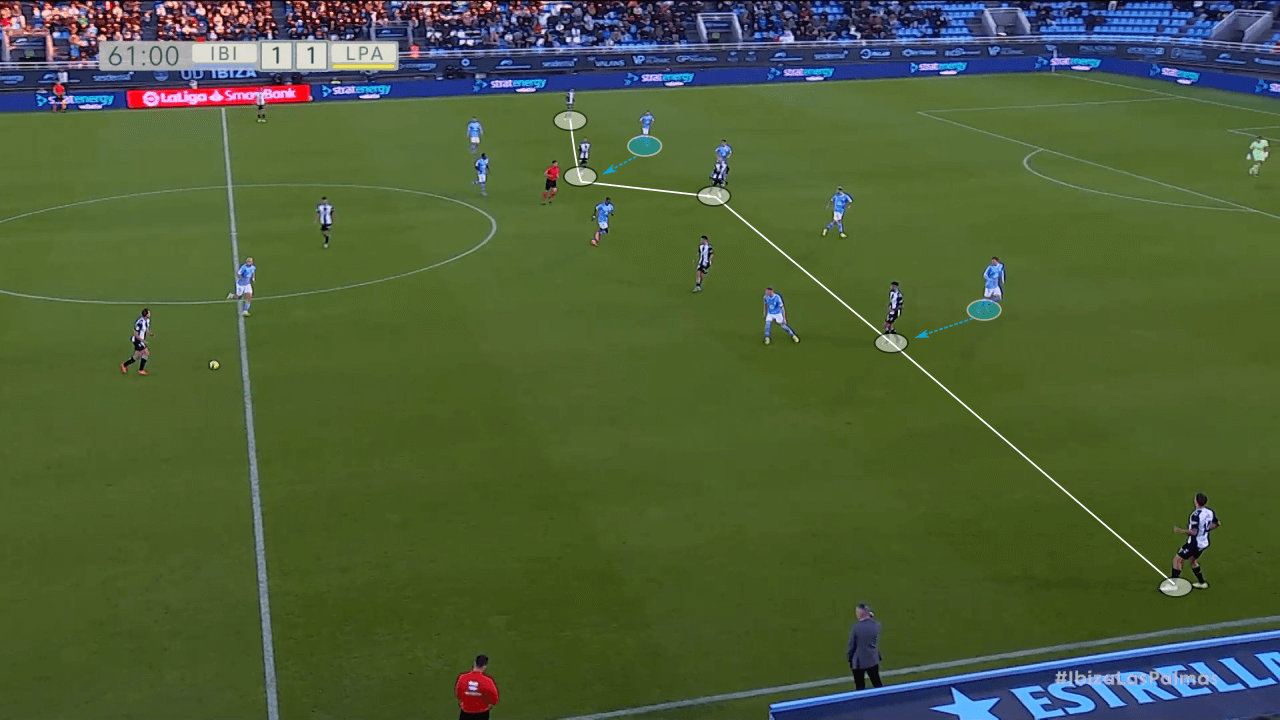

In another final third scenario, we are able to see a few more patterns in their attacking behaviour. As the ball is switched to the opposite side, the right winger arrives late in the final third with space. The right midfielder makes an underlapping run to drag the opposition’s left-back wide while the ball carrier drives inside.

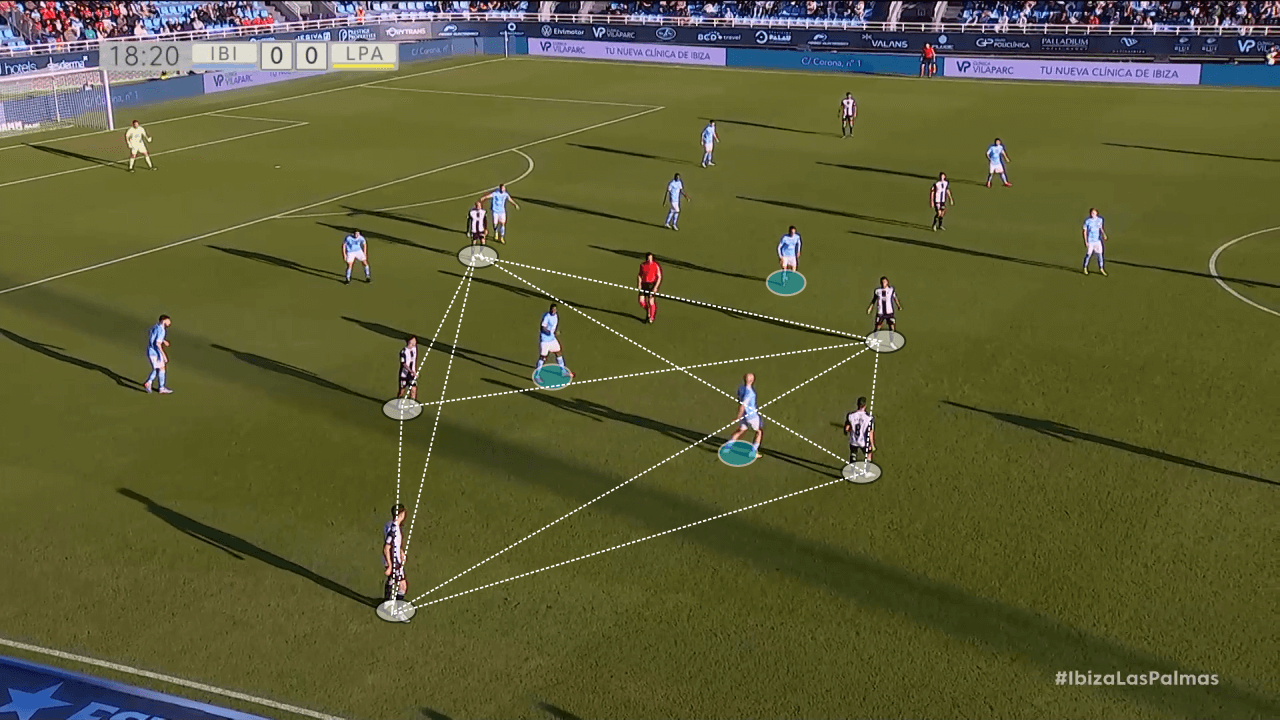

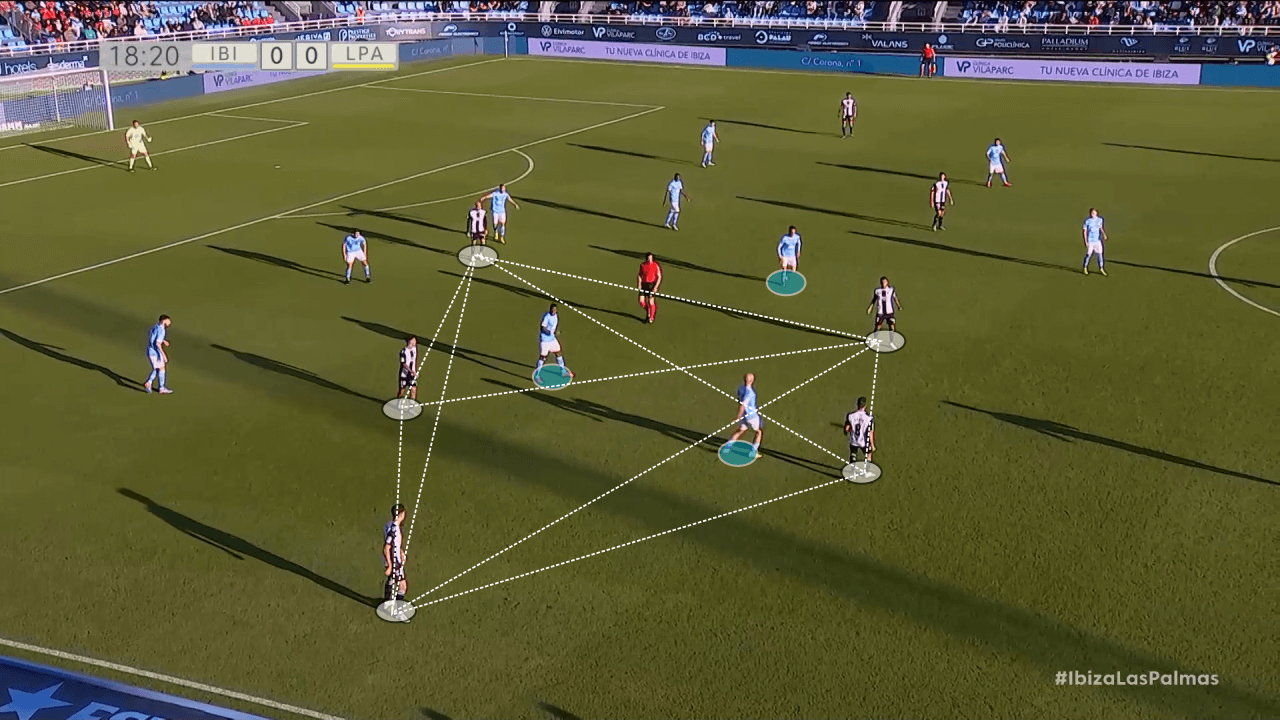

In the example below, we can see their attacking system on full display. As they attempt to break down the opposition’s low block, they create a network of passing angles around the ball. This highlights two significant points.

First, following their spatial guidelines is what allows for such an effective passing network. They create optimal angles which help them play through the opposition’s low block.

Secondly, this demonstrates how, at times, Positional Play can easily turn into its opposite, Functional Play. The recent debate between the two approaches has caused a false dichotomy, where people assume that it must be one or the other, that they are entirely opposite from each other. This is not necessarily true, and they can often take aspects from each other.

This can be further explored in another instance, later in the same match. Pimienta’s men try to create a chance through the right wing, and in trying to do so, they gather six players in that zone alone. García Pimienta’s tactics are clearly guided by Positional Play, but it is conducted with such fluidity that at times, it can turn into a very distinct approach.

Conclusion

Las Palmas have been performing extremely well under 48-year-old manager García Pimienta. Estadio Gran Canaria could play host to La Liga football for the first time in five years, but most importantly, it has seen an important evolution to Positional Play.

At La Masia, Pimienta took a lot from the Catalan school of football and its latest product, Juego de Posición. Now at Las Palmas, the Spaniard is playing a significant role in the development and evolution of this style of play.

Comments