Gerhard Struber’s senior management career is still in its infancy.

He took his first senior job only two years ago after leaving Red Bull Salzburg U19 stint to take on the full-time Head Coach position at Liefering, having previously worked as a coach alongside his Salzburg role too.

Struber stepped down just over six months later to focus on obtaining his UEFA pro license, and at the beginning of the 2019/20 season, he took over Wolfsberger.

Yet in November of that season, he moved on once more, with Barnsley appointing him as Manager, and tasked with keeping them up in the Championship.

Struber succeeded before continuing in his whirlwind few seasons as a senior football Head Coach, being appointed in this role at New York Red Bulls of the MLS in October of this year.

However, due to work visa restrictions, Struber only took charge of one game before the end of the season for Red Bulls.

This tactical analysis will look to give an analysis of some of Struber’s key principles and tactics, highlighting how the 43-year-old Austrian has already sought to instate them throughout Red Bulls’ play in the four moments of the game.

In brief, Gerhard Struber tactics looks to employ a direct, high-intensity style of football, with an emphasis on regaining possession quickly, preferably as the opposition are out of balance. He likes to use quick passing combinations to manipulate the opposition’s defensive shape, create overloads, and in general have plenty of players around the ball to secure possession and create counter-pressing opportunities. He also looks to use an intelligent pressing system that will force the opponent to play into areas where Red Bulls can regain possession with an attacking opportunity, by setting traps as part of a patient and compact mid block.

Shape basics

Struber has some tendencies in terms of formations he favours. At Barnsley, he showed a penchant for the 3-4-1-2 and 4-3-1-2. The obvious similarities between these two shapes are the presence of a number 10, and two centre-forwards.

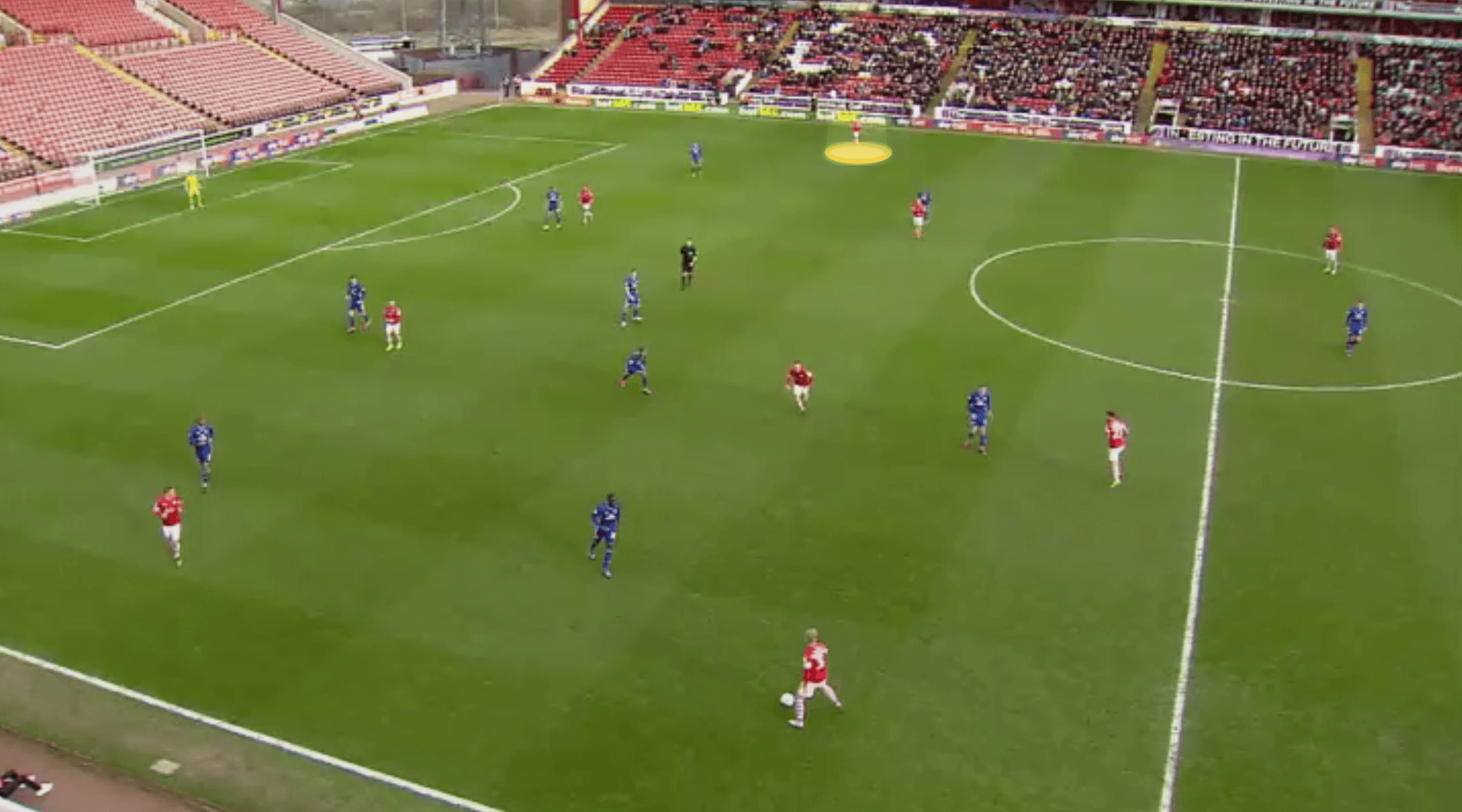

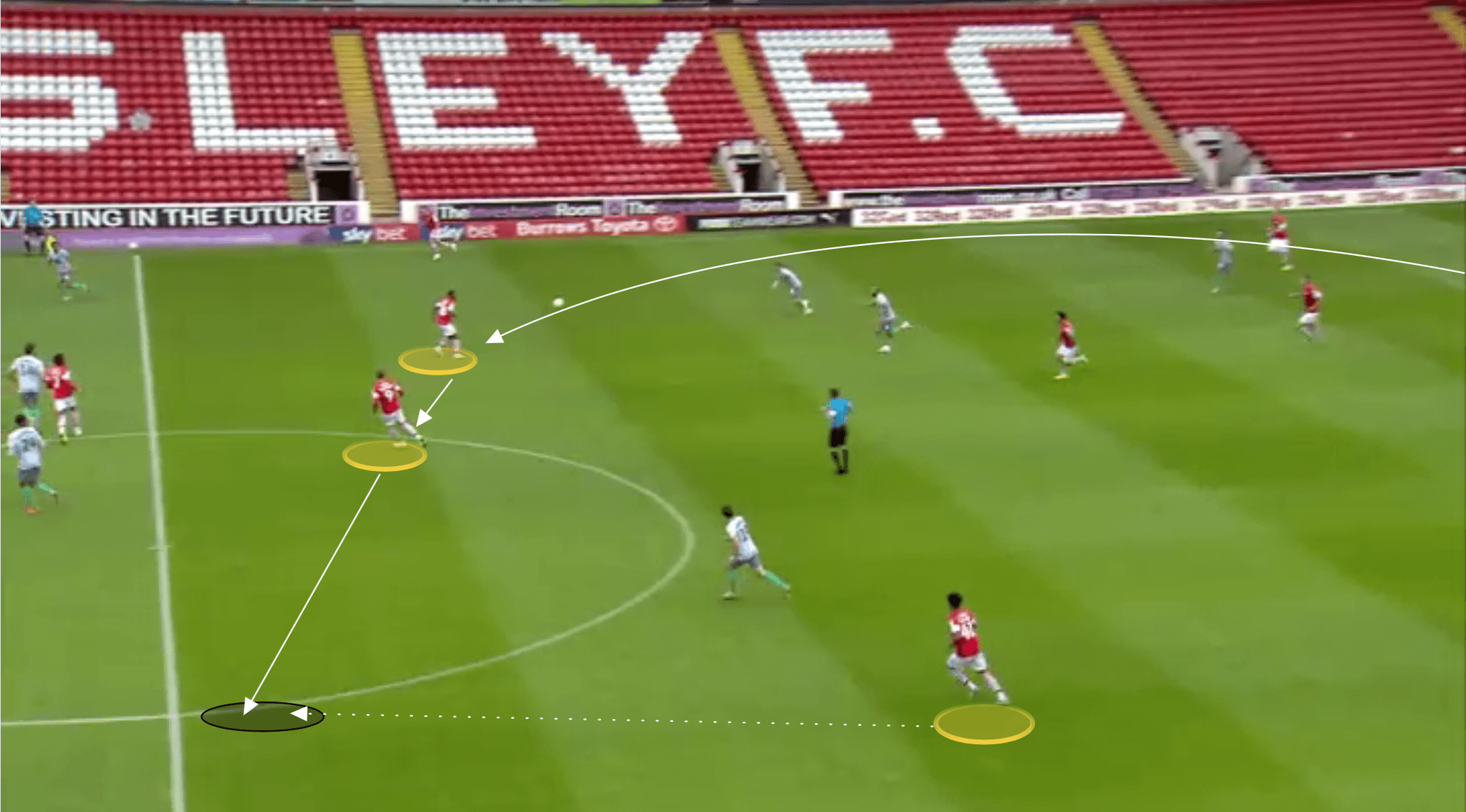

Both formations also lack traditional wingers, and regardless of whether Struber uses wing-backs or standard full-backs in a back four, he expects these players to provide the width in attack as we can see in the image below with the high positioning of the Barnsley right-back.

On top of these players providing width, the lack of a winger also gives freedom to the centre-forwards to drift into wide areas and engage in quick passing sequences to help advance the ball in these areas whilst also potentially leaving space centrally.

The number 10 is expected to operate closely to his front two and when this occurs he can simply push into the centre-forward space himself.

It’s not a hard task for the number 10 to do this.

Throughout this analysis, it will be obvious that Struber likes his side to play with compactness at all times. Not only does it facilitate these snappy passing sequences, but it aids ball retention by providing a structure for effective counter-pressing – something which Struber is particularly fond of.

When Struber uses the back three, it allows for one less central midfielder than when he uses his midfield diamond.

However, generally speaking, his back three is more orthodox out of possession than in possession.

When Barnsley would have the ball he was happy for his left-sided centre-back to push forward more, often taking a narrower position in the half-space alongside the pivot.

This provided a lateral passing option, allowed the left wing-back to push into a more advanced position, and provided more security against the counter-attack. Interestingly, we can see the right-wing back has taken a similar position to the left centre-back, essentially giving Barnsley the same shape they would have if using a back four, and so their build-up shape here is near-identical to that of their 4-3-1-2.

In the defensive phase, the back three are pretty aggressive with their decisions to come out of their compact shape either horizontally or vertically, and the proximity of the pivot allows them to do this, whilst still maintaining a solid central three, as we can see in the image below.

Playing between the lines

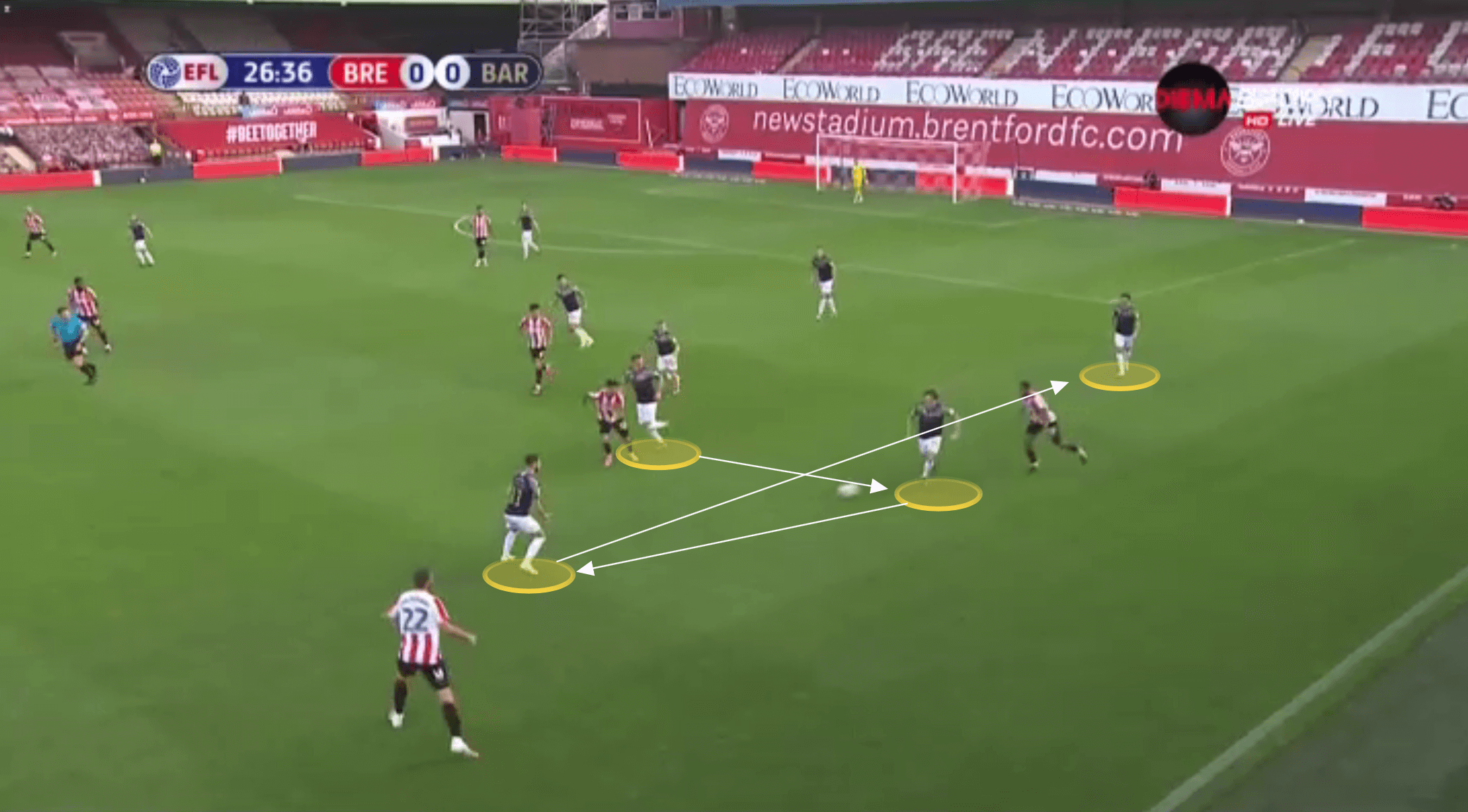

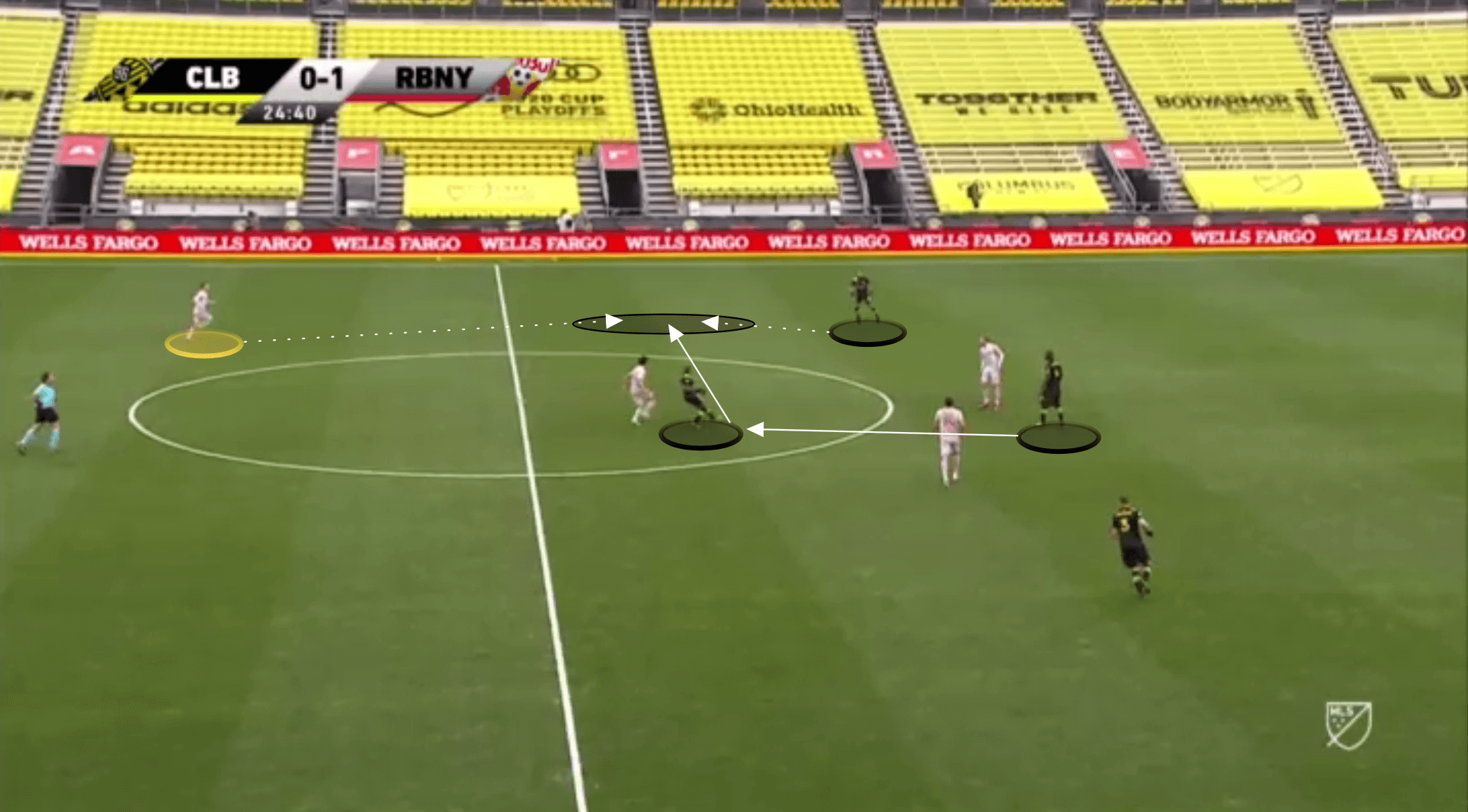

Struber’s sides are prolific at creating and finding space to play between the opposition’s lines, and they engage in swift up, back, and through passing patterns to achieve this.

By using this pattern they are able to structure forward passing, but also draw individual opponents out of their own compact defensive shape and this creates opportunities for Struber’s sides to exploit these gaps in attack.

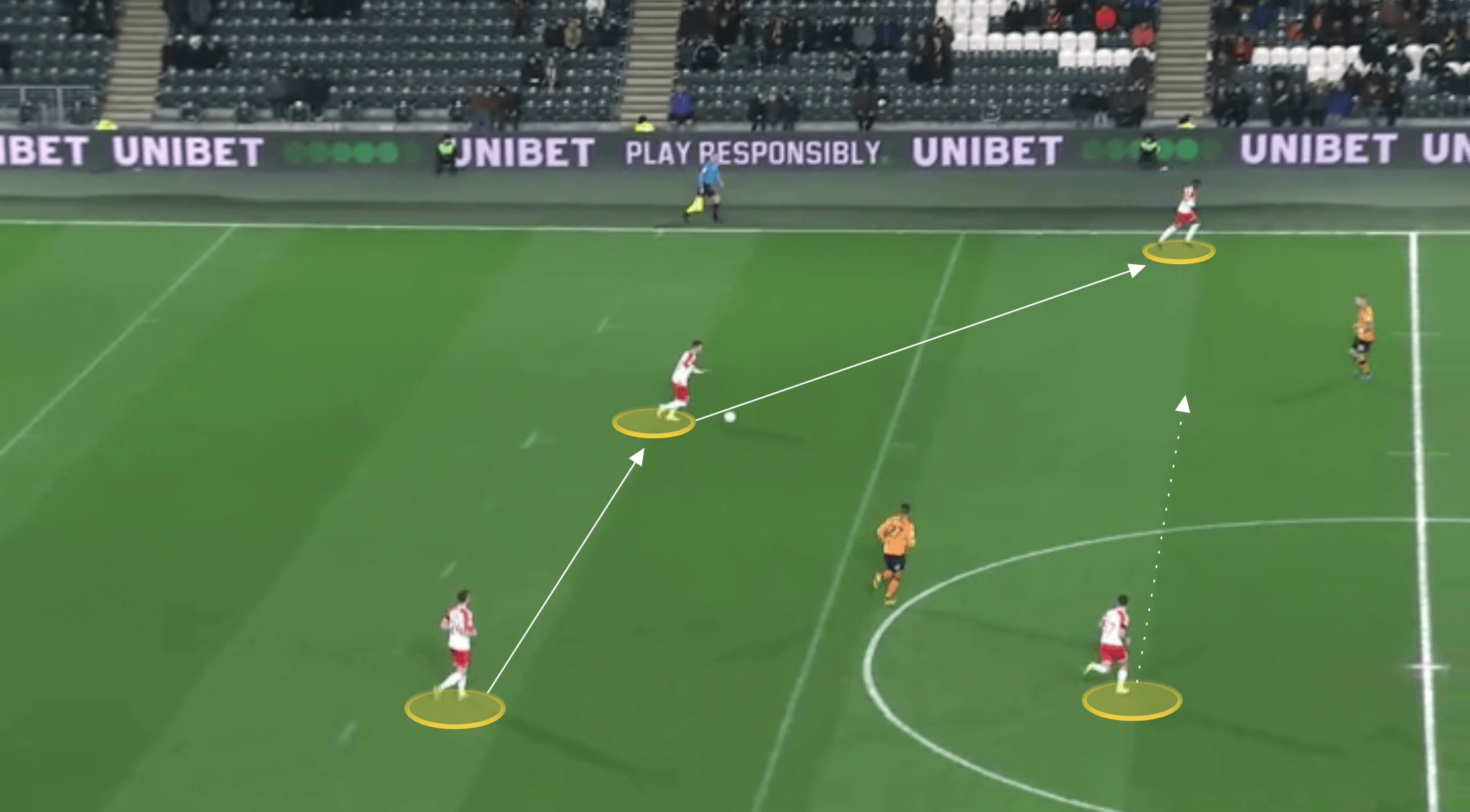

Struber uses his pivot to orchestrate plenty of these passing patterns in the build-up phase. Generally speaking, Struber’s pivot plays a very orthodox role, always providing an option beyond the first line of the press, and shifting from side to side to help circulate the ball, and provide immediate lateral passing options for wide players.

But as much as they are that first option beyond the first line of the press, they are also the first option should Struber’s centre-backs kick the ball even farther forward. Struber expects his pivot, who will often be marked either specifically or through the centre-forward’s cover shadow, to facilitate forward passes by initially dragging his marker out of position enough to create the passing line. As soon as this has been found he is able to swoop around to receive the short pass, and whereas his teammate received with his back to goal, the pivot is able to see the entire pitch.

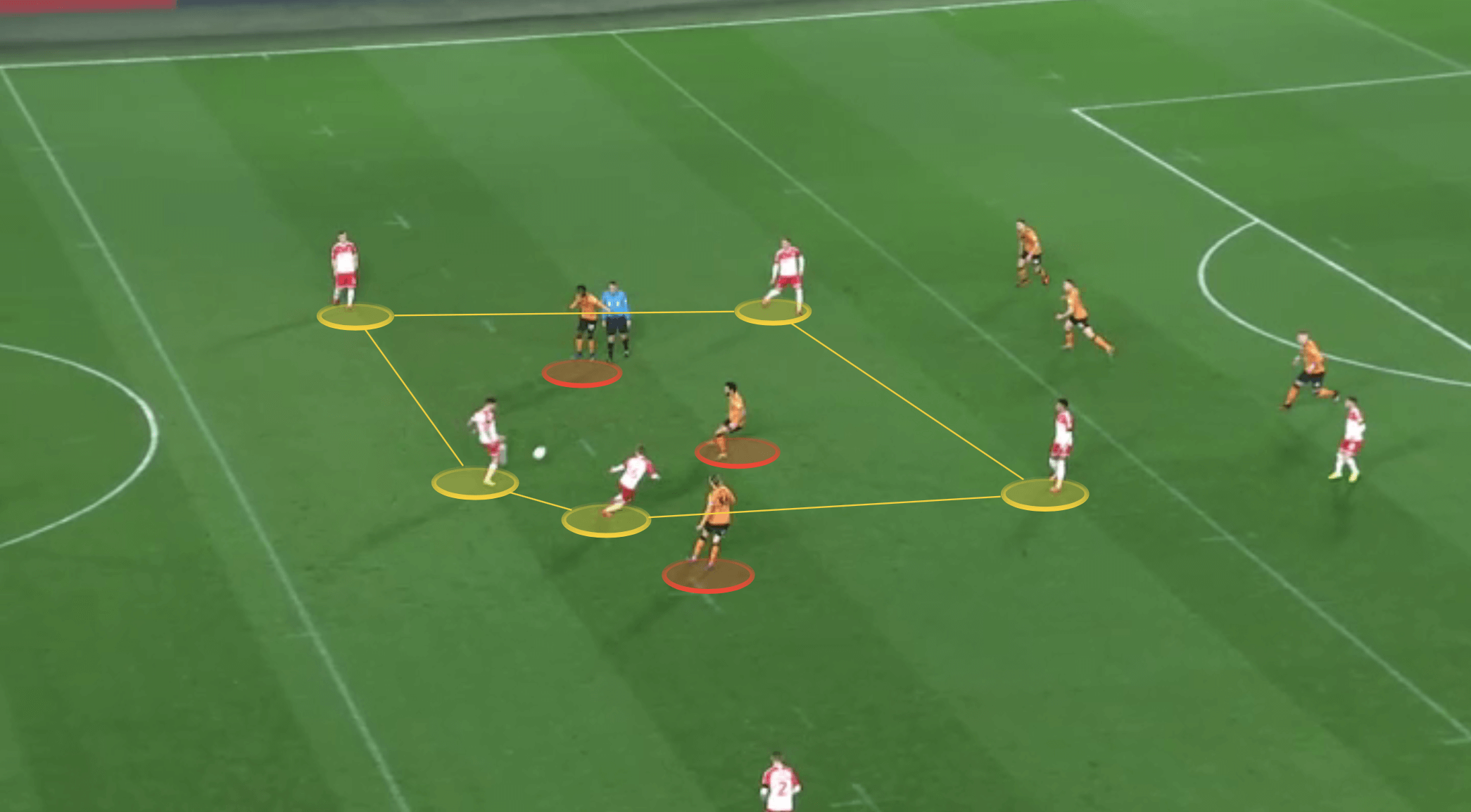

We can see this occurring in the image below, and we can also see how the left sided midfielder of Struber’s diamond reacts to this pattern by making a run in between the lines of Hull’s midfield and defence himself.

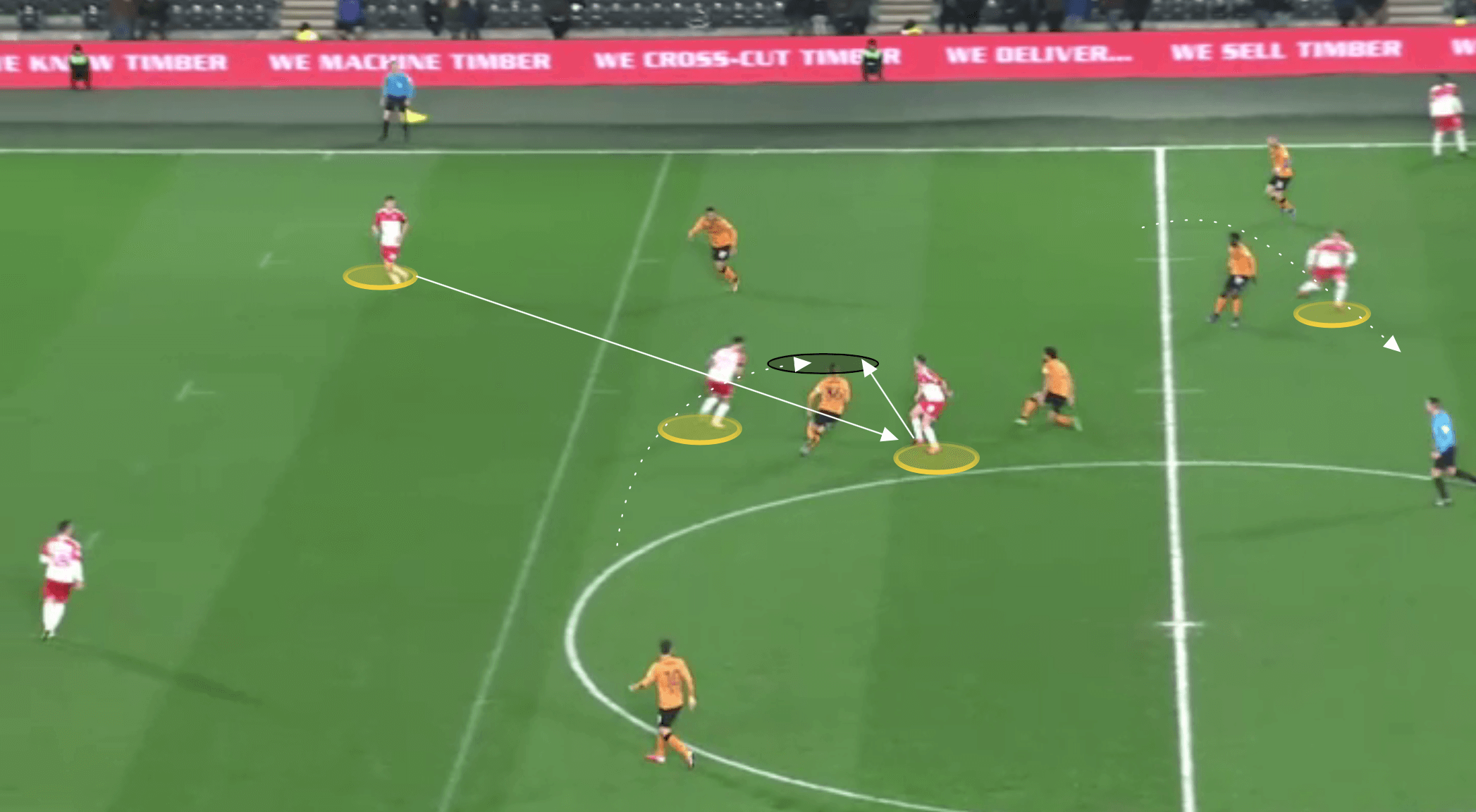

We don’t just see these pass patterns in the build-up phase either, with Struber’s teams using them to great effect to break the lines by getting the ball into the centre-forward early and providing him with immediate options to secure the ball and continue the attack.

Struber’s likes his sides to crowd the central channel of the pitch. In doing so they can play quick passes to narrow the opposition and help teammates find pockets of space in the half-spaces, or plenty of space on the flanks. The midfield diamond is perfect for achieving this, and its natural structure lends itself perfectly to the up, back and through pass pattern.

His forwards have the freedom to drop into midfield and further overload the central channel too. We can see an example of this below, as Struber’s Barnsley can be seen with a plethora of options around the centre-forward that can help them advance the ball, or seek to regain it very quickly should they lose the ball.

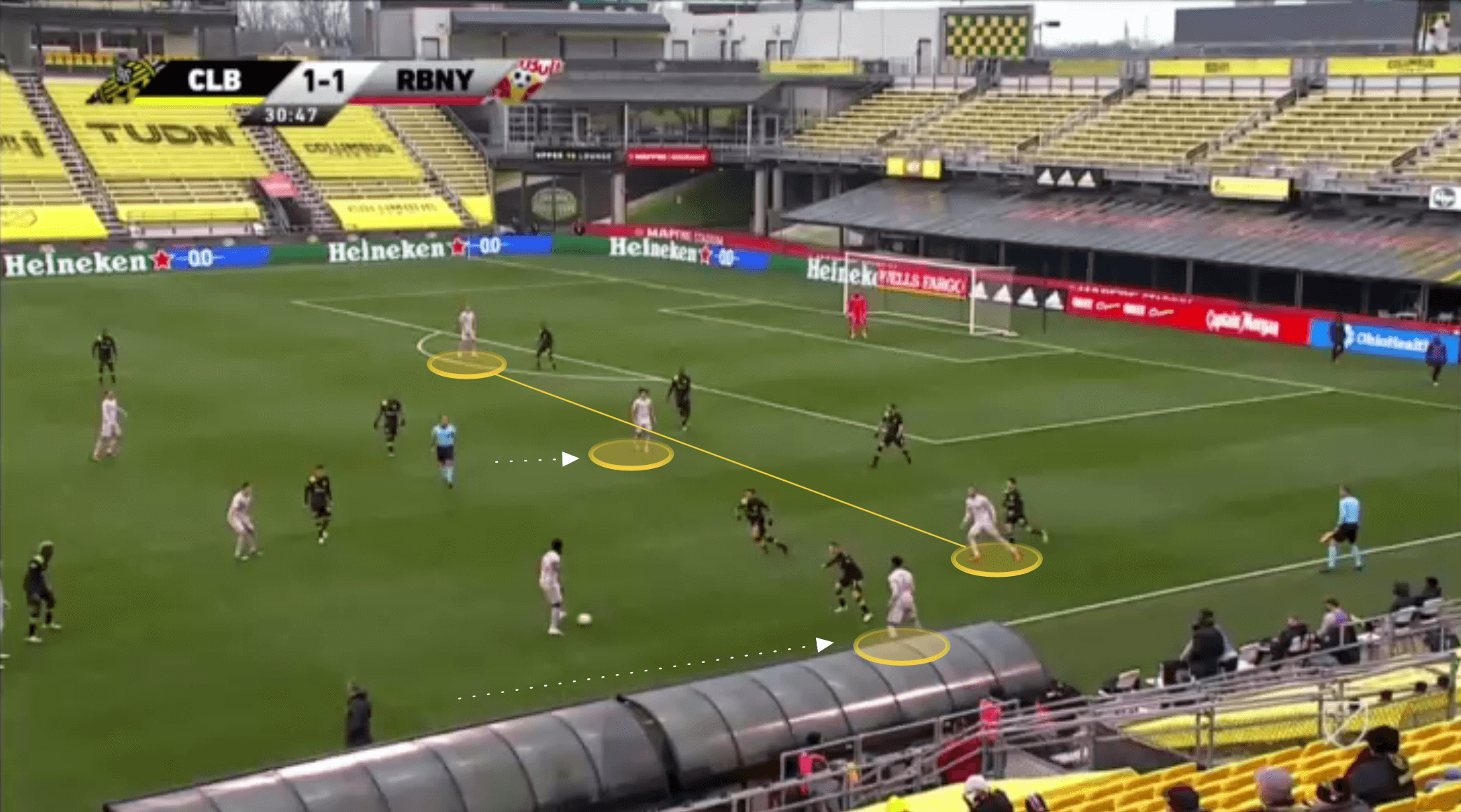

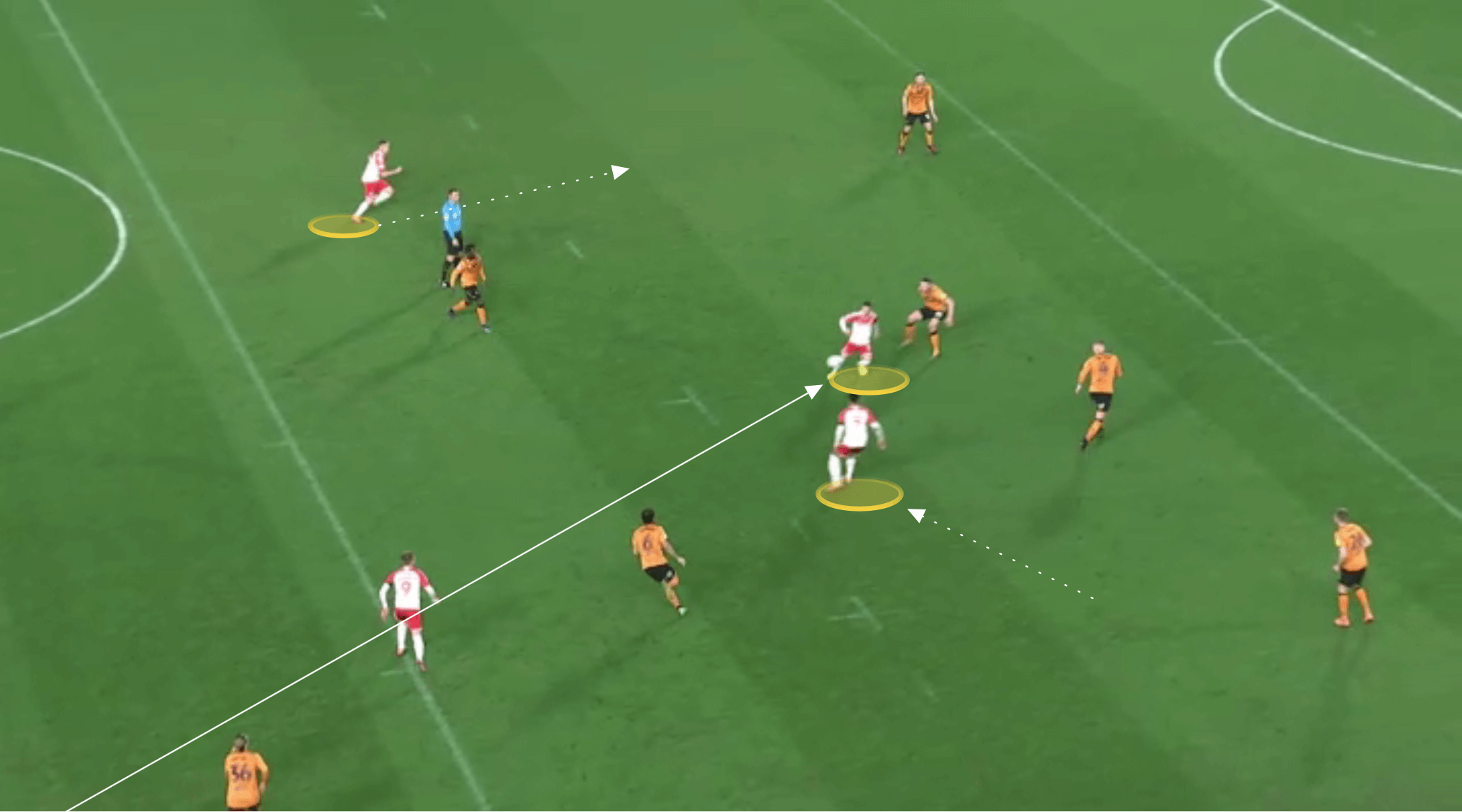

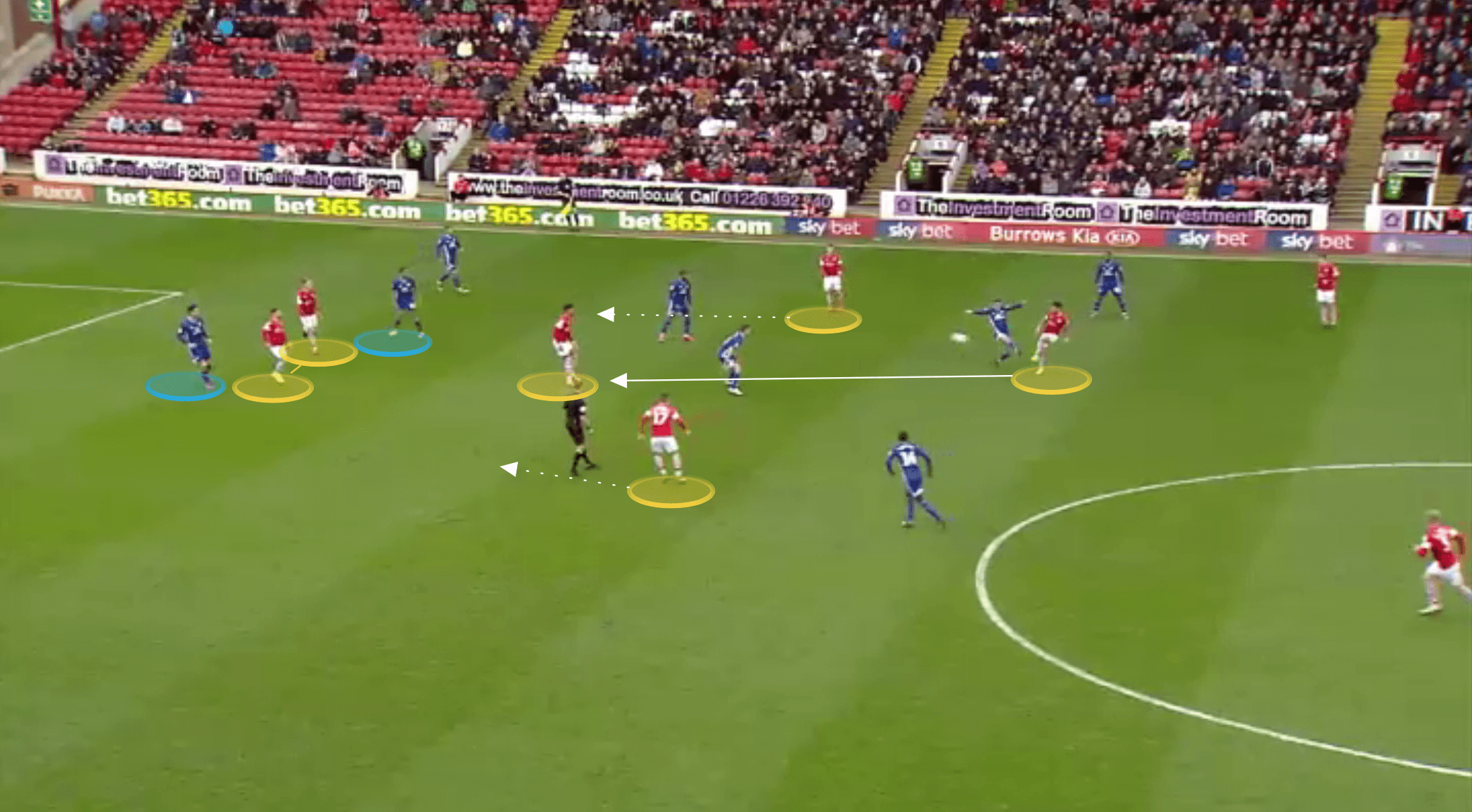

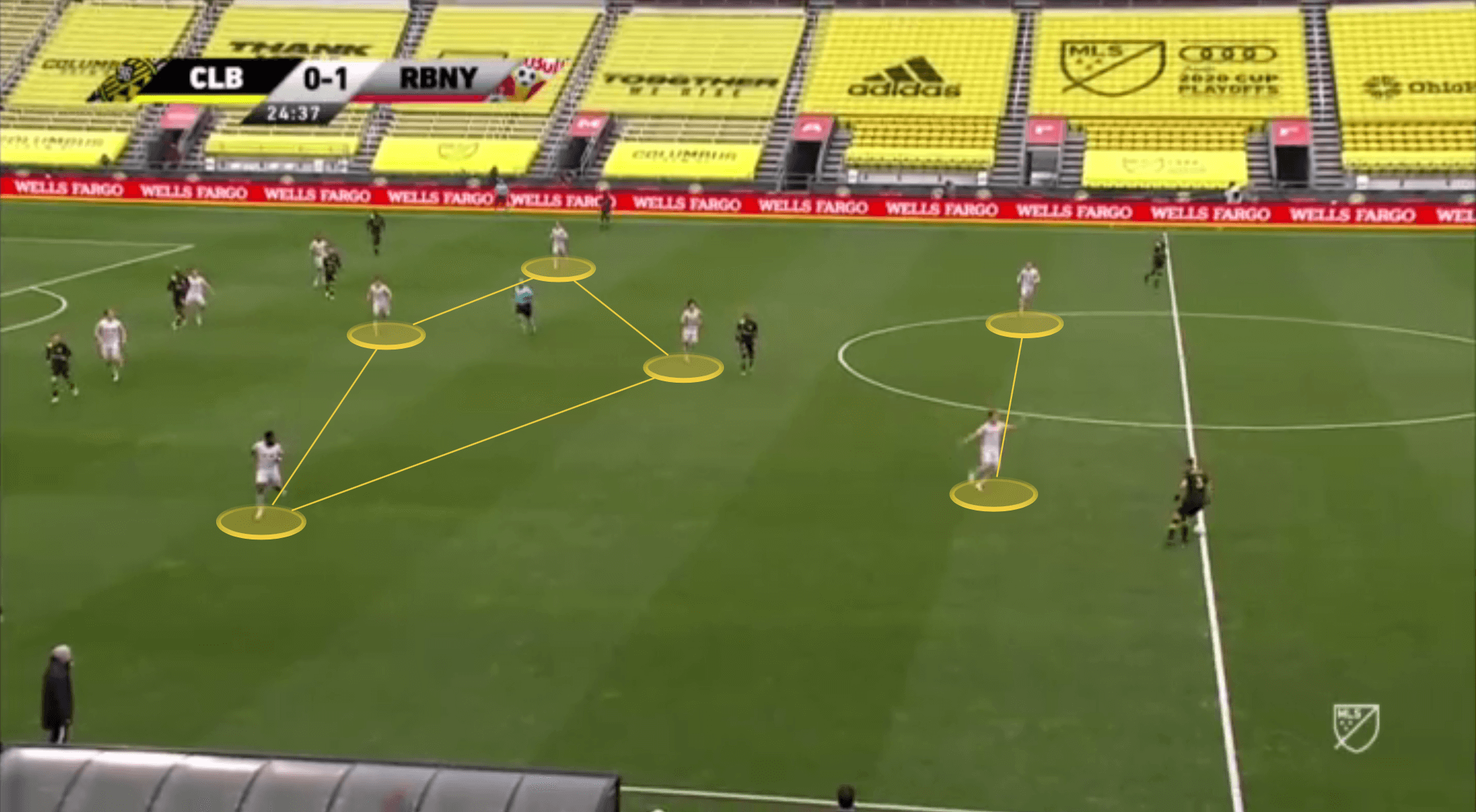

Struber’s side’s structure and this passing pattern provide phenomenal tools for them in orchestrating attacking transitions too. With so many players around the ball, as soon as possession is won, his teams can quickly move the ball out of the danger area, with the players instinctively knowing where to move to, and where their teammates will be, allowing them to play swift, one-touch passing football to break out of the area where they have just won the ball, and secure possession, like in the image below.

This example shows Barnsley achieving this inside their own half, but it’s the same result well inside the opposition half too. The image below shows Barnsley regaining possession. Immediately there is an option for the ball-winner in between the lines, and on either side of that player there is a third-man option. The reason the player in between the lines has that space is due to the compactness of Barnsley’s two forwards too, which prevents the Cardiff centre-backs from getting too close to the player in the 10 space.

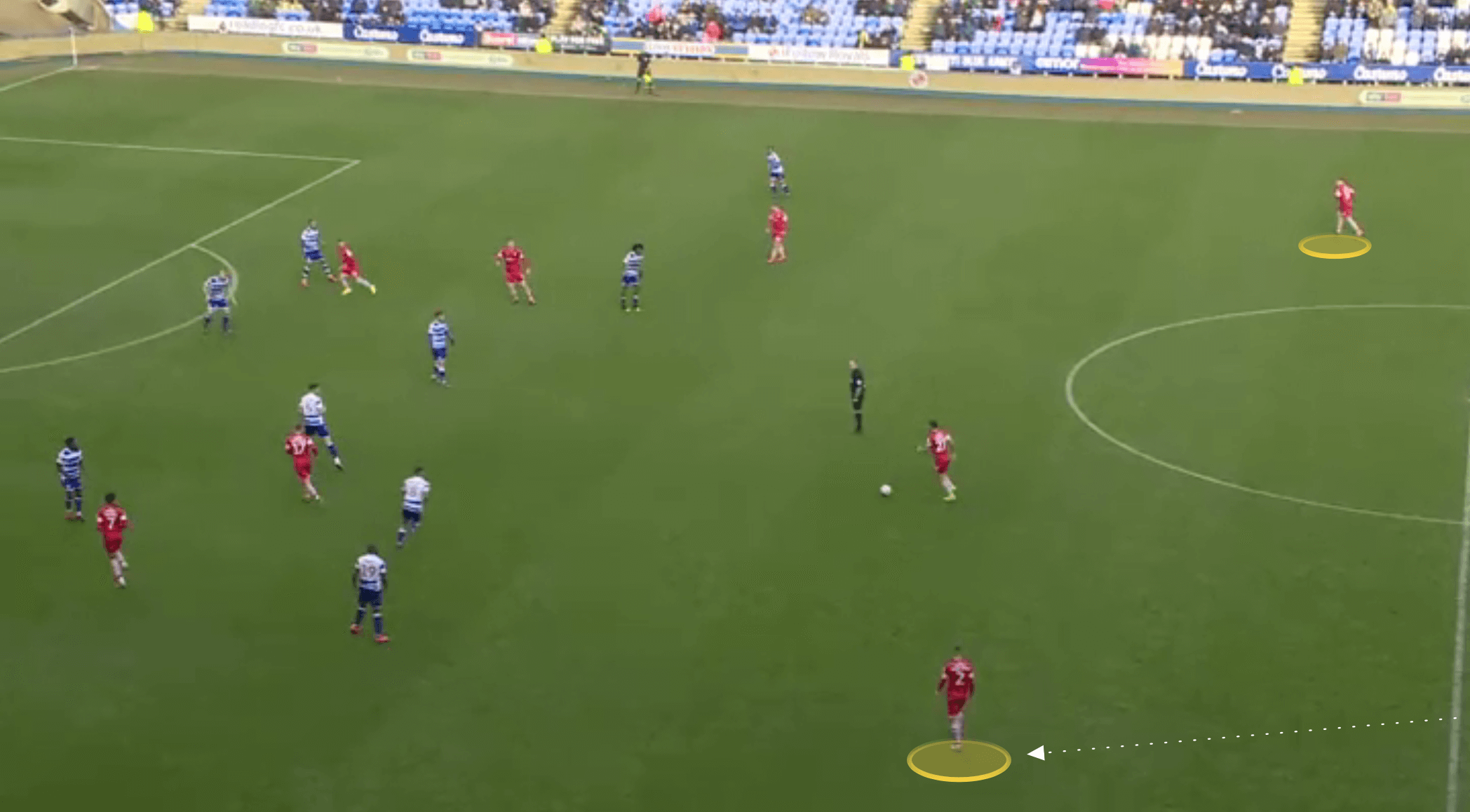

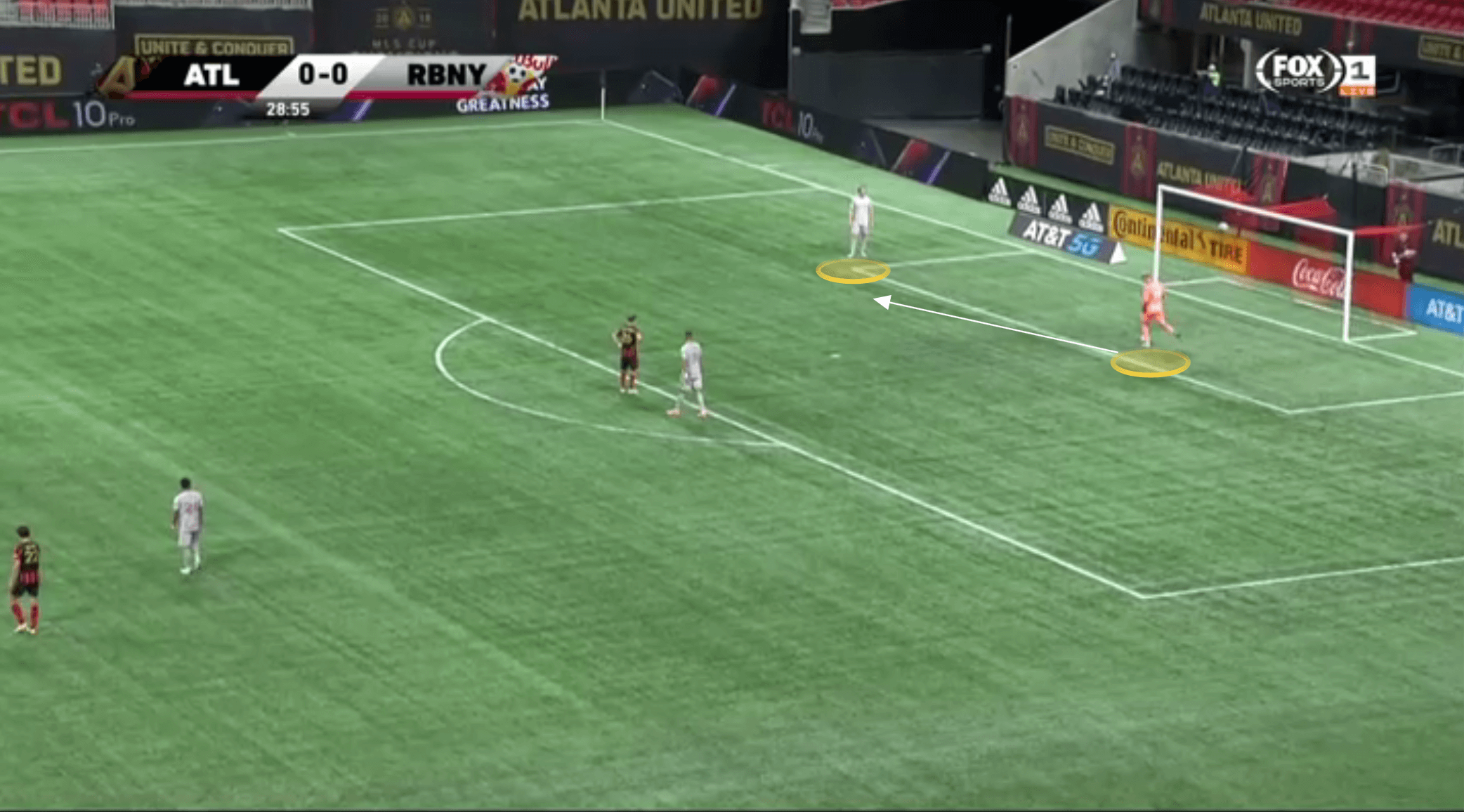

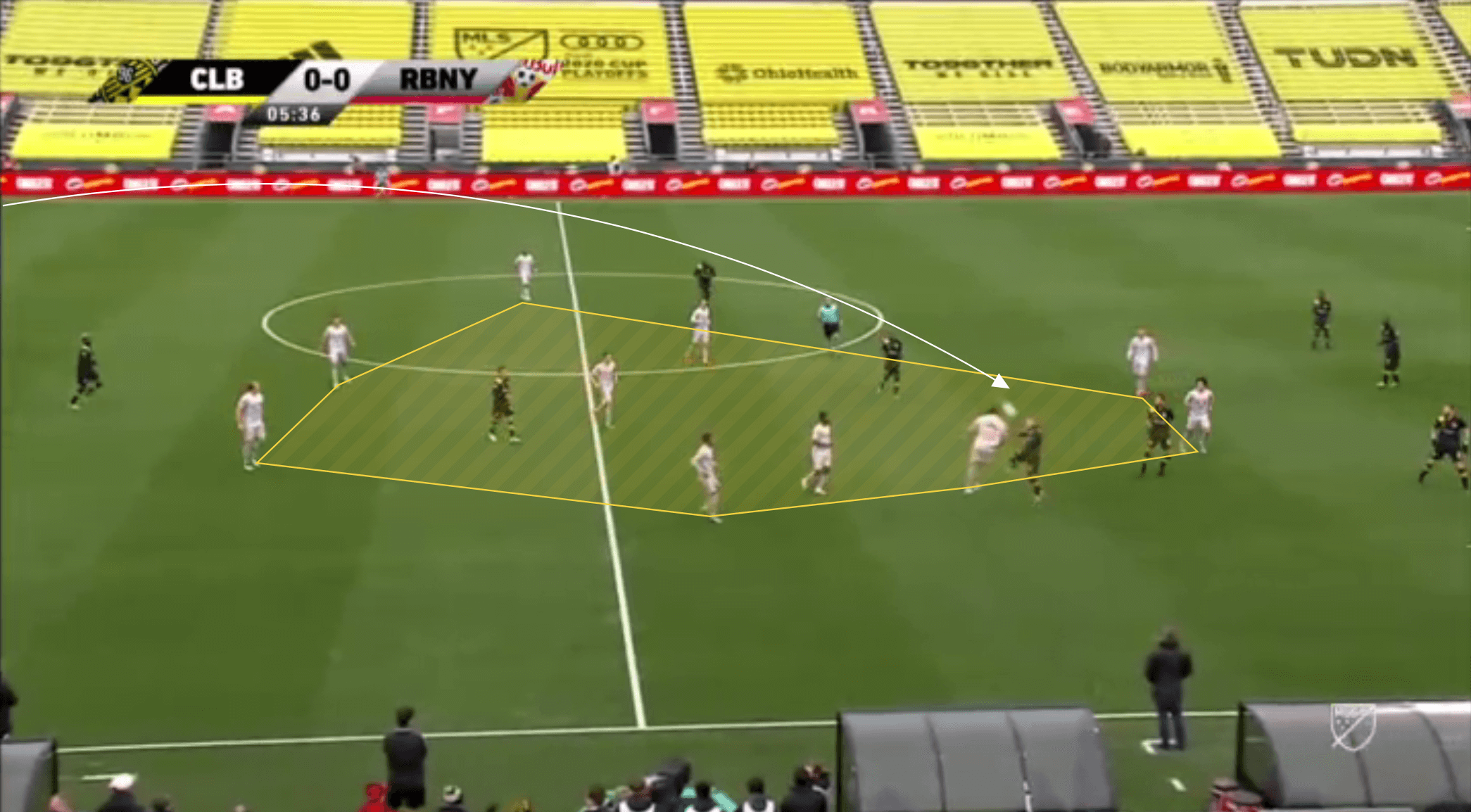

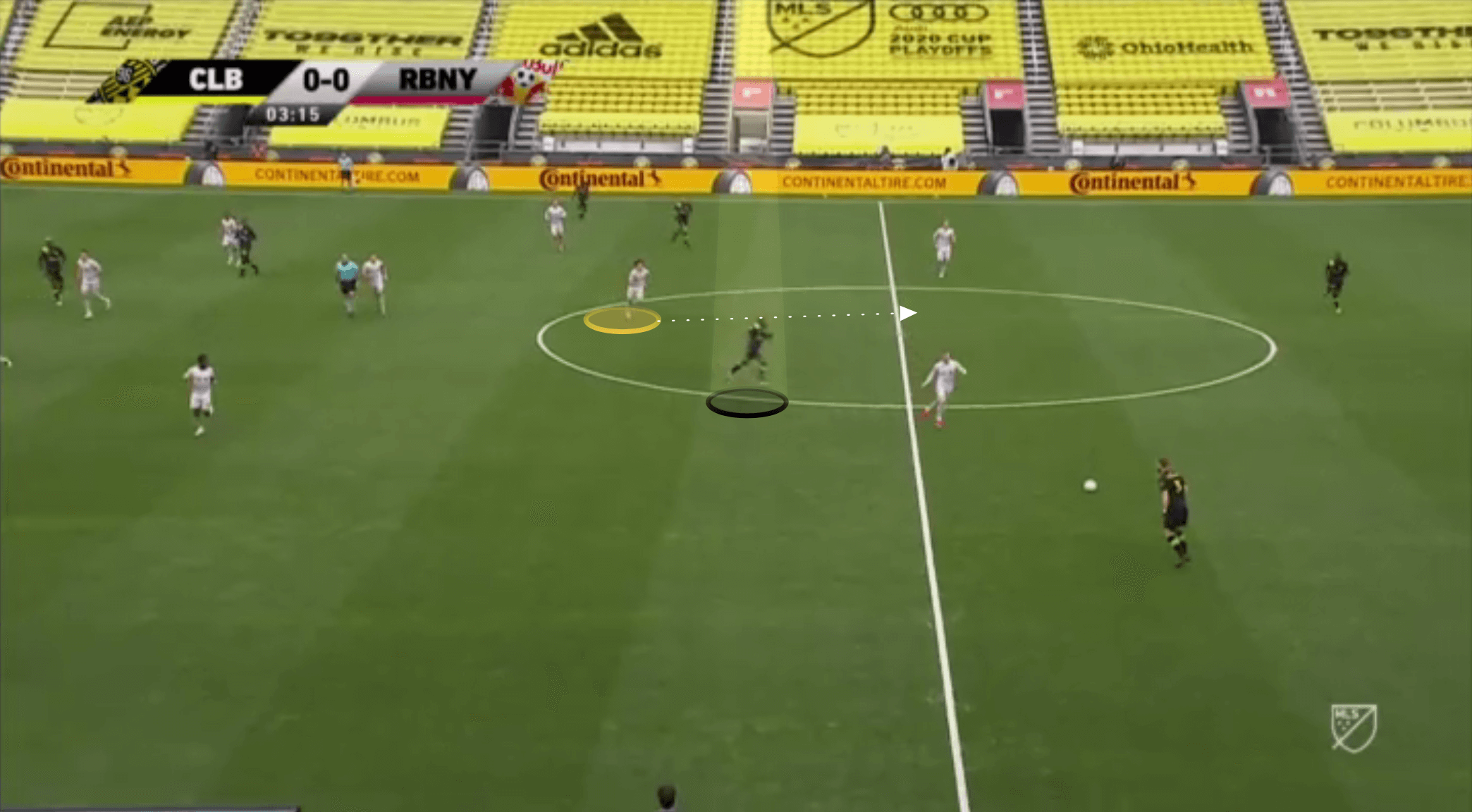

Although Struber’s official takeover at Red Bulls was delayed, it has been obvious since his appointment that Red Bulls were already looking to instill his style of football, and even specific tactical tendencies, since the deal was announced. One particularly interesting pattern presents itself in the form of one centre-back receiving the ball a matter of yards away from the goalkeeper, but with no other defenders providing an immediate option.

When Struber’s teams do something to this effect, it appears to be in an effort to engage the opposition’s press forward and over to one side of the pitch. When he did this with Barnsley, the reaction would be for all of the players to instantly shift across, moving their apparent focus to one side of the pitch.

Yet the centre-back, or keeper, will then play a direct pass forward, once the press has been engaged in the desired way, and in doing so they look to find a midfielder or attacker in between the opponent’s midfield and defensive lines, immediately bypassing the first and second lines of the press.

Struber’s side then looks to quickly switch the play to the flank where the opponent has little coverage on and attempt a quick break down this side of the pitch.

It’s another example of utilising the man in between the lines, and shows Struber’s intention to have a direct, quick-flowing vertical brand of football.

Effective counter-pressing

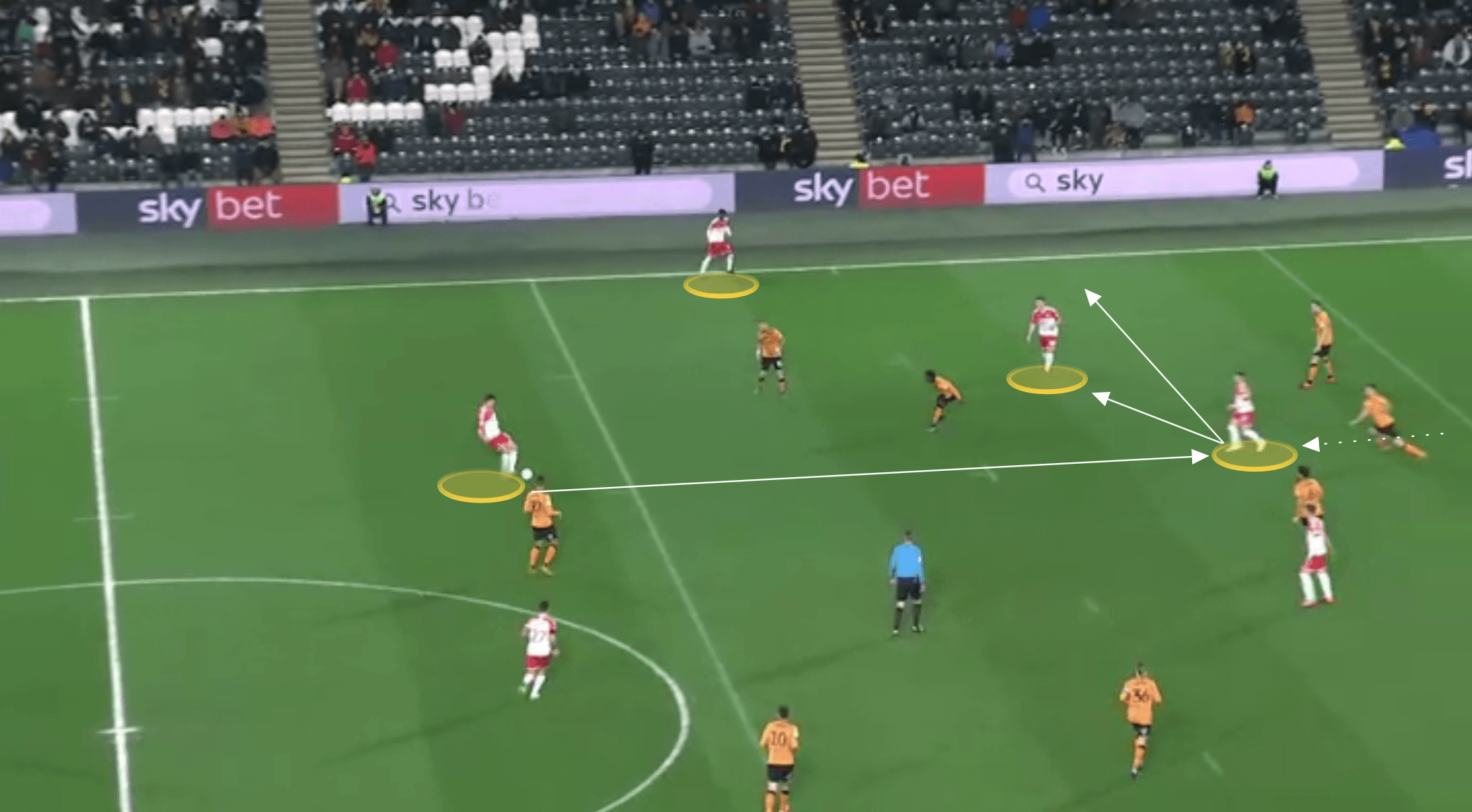

The compactness of Struber’s sides in and out of possession has already been alluded to, and Struber uses the proximity of his players to one another to ensure that the ball can be moved quickly and safely, but also to allow his players to quickly regain the ball should possession be lost. When the ball has been regained, Struber’s side then have players around the ball to quickly bounce it too, not allowing any one player to remain in possession too long and potentially turn over the ball again. The ball is worked quickly out of the danger zone, as highlighted in the previous section, and his side can resume the possession phase.

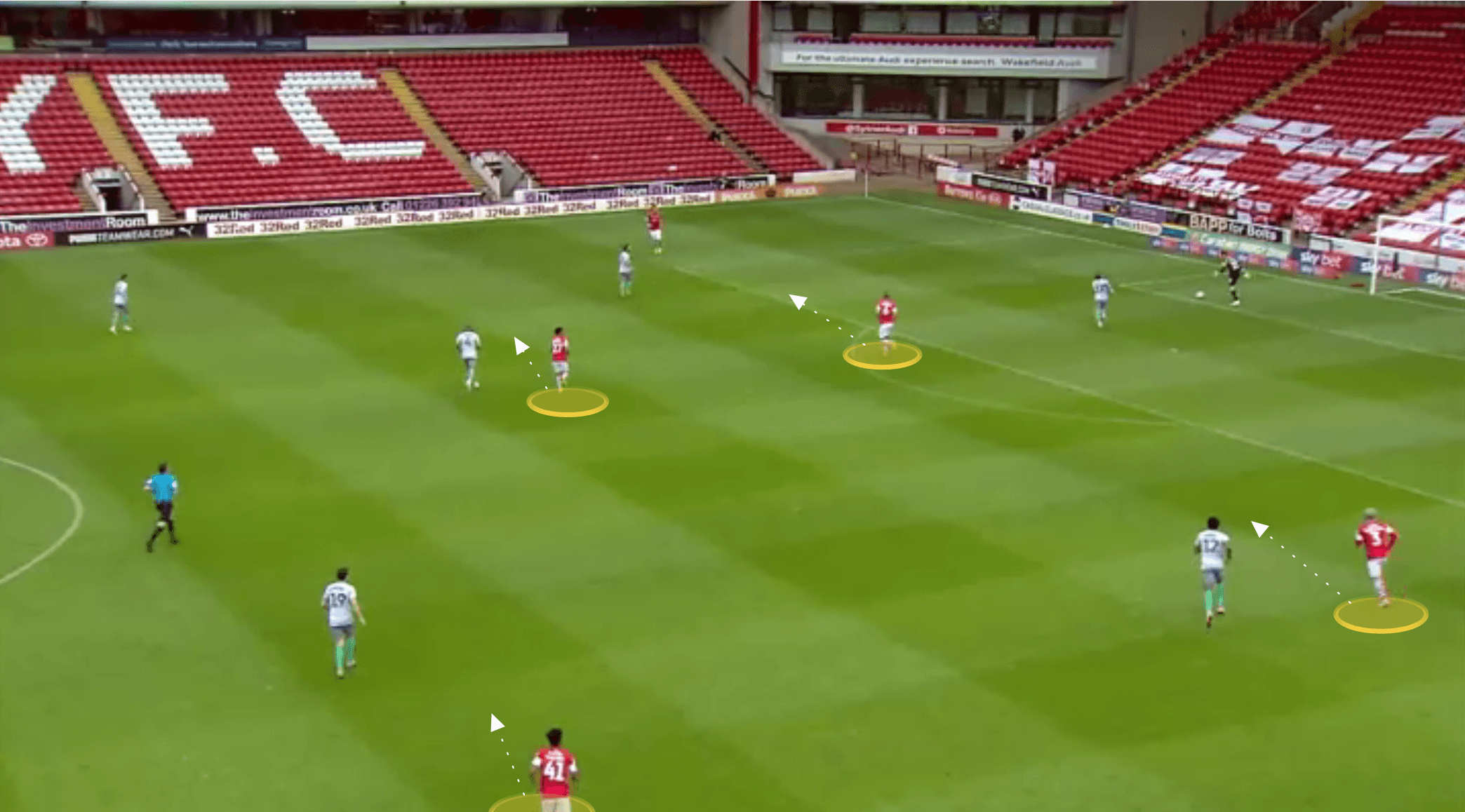

We can see an example of the number of players Struber places around the ball at any one time with one of his centre-forwards dropping deep to create a 5v3 for Struber’s Barnsley against Hull.

If his side look to play long from the keeper, he is sure to have his side remain as a compact unit. They will always compete for the first ball, and ensure they have plenty of players surrounding the contest to sweep up the second ball and continue their possession phase inside the opposition’s half. Below we can see how in the space of Struber’s 10 outfield men, the opponent has only four players. Regardless of how well the opposition defender does in the aerial duel, the likelihood of one of these four players beating one of the other nine of Struber’s players to the ball is incredibly unlikely. Even if they do latch onto the second ball, they would be instantly swarmed by Struber’s players.

Intense and intelligent pressing

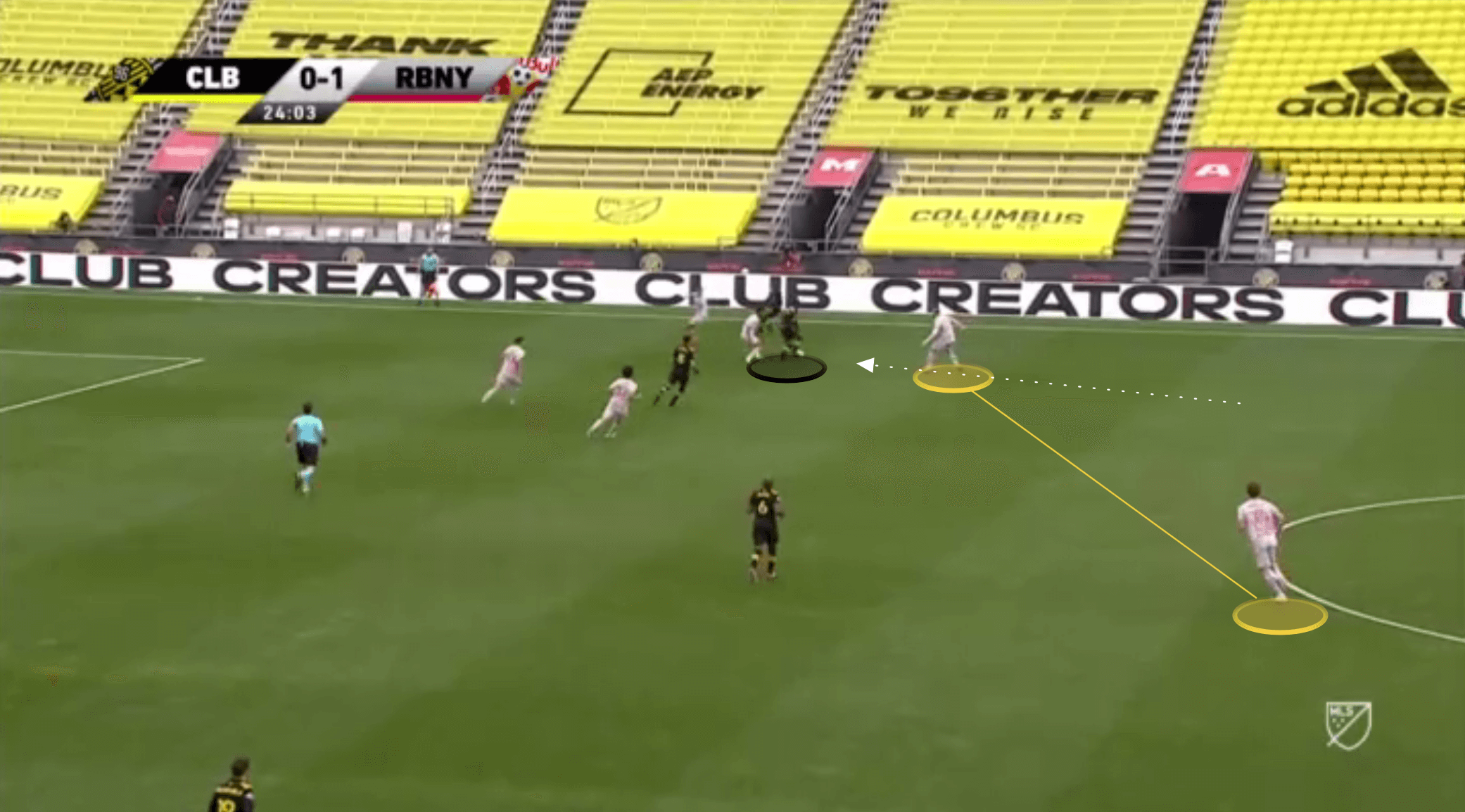

Struber’s teams initially press with a front two, where the number 10 has the freedom to join them should he be required to.

A non-negotiable for the Austrian’s sides is to ensure the opposition pivot is unable to receive the ball and this responsibility generally falls to the number 10. The two forwards will angle their pressing runs to show the two centre-backs inside where, with the opposition pivot man-marked, they must seek to break the line of press and play further afield to their more advanced midfield teammates, which is a much higher risk.

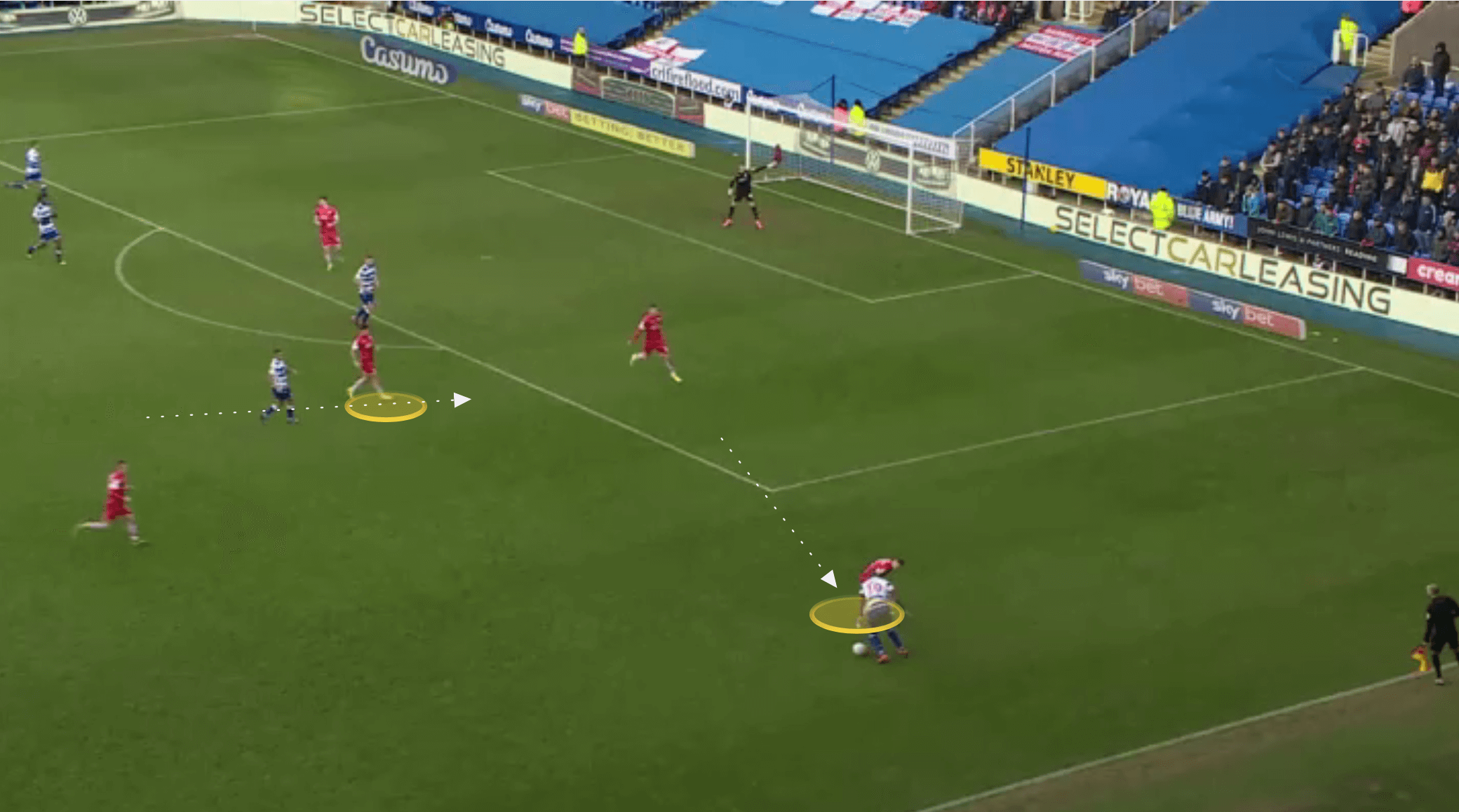

We can see how this shape is maintained even when Struber’s sides defend deeper, like in the image below, where the front two will work the two centre-backs, and the number 10 sits at the top of the diamond, still marking the opposition pivot.

Should the pivot seek to drop in between the opposition centre-backs to seek possession, the number 10 has the freedom to push forward to continue marking this player (within reason), even if it means they bypass the two centre-forwards.

With such pressure put on the opposition’s centre-backs and pivot, and with the press looking to force them to play inside into traffic, opportunities will often present themselves with sloppy passes. The kind of blind passes made below by the pivot are exactly the opportunities Struber wants to make, and his wide midfielders are alert to this. Any flat, lateral passes under pressure, like the one below, are a trigger for Struber’s teams to press, and he looks to test his opponent’s commitment to playing out from the back with situations like this.

He has high expectations for his two centre-forwards when it comes to the out-of-possession phase, too, and even if they are beaten when pressing, they are expected to immediately come back on themselves and provide pressure from behind the opponent.

In doing so, they are providing pressure on the ball and allowing their midfield and defence to keep their compact shape, at least to an extent, and this makes it more difficult for the opposition to properly lure Struber’s teams out of their shape and create space between the lines.

Conclusion

Taking charge of New York Red Bulls is a very different task to the one Struber inherited at Barnsley. He is arguably moving to a slightly slower-paced, yet perhaps more technical league than the Championship, and it’s unlikely we’ll see the exact same tactics he used with Barnsley at this level.

However, it is then quite possible that we will at least see him seek to achieve the same principles of play that he used at Barnsley, some of which have been highlighted in this analysis – the quick, high tempo passing game, the emphasis on playing forward, the compact shape and aggressive counter-pressing, and using the press to force opponents inside into the congested central channel, where his side can regain possession.

We will have to wait a number of months, however, until we see just what his New York Red Bulls side looks like, but with the success Jesse Marsch has enjoyed since taking this job and later moving to Salzburg, Struber is certainly a name worth keeping an eye on over the next 12 months.

Comments