The 2018 World Cup seems a long time ago now. This competition was one of the most enjoyable tournaments ever, with some memorable results and performances from high-profile players. Kylian Mbappé proved he was a truly global superstar and England broke their penalty curse, for example. France and England both had excellent tournaments as well. France obviously winning and England completely exceeding expectations to get to the semi-finals, galvanising a whole nation in the process. However, there was one European side that fell flat on their face, Germany.

Arriving in Russia as defending champions and world number one team in international competitions, the Germans were expected to be successful again. Getting out of the group was arguably seen as a formality, facing: Mexico, Sweden and South Korea. Joachim Löw opted for a combination of the new talents like Timo Werner and Julian Brandt while keeping experience around in the form of Bayern Munich’s Jerome Boateng and Mats Hummels. It didn’t go to plan – at all. The previous winners finished a resounding bottom, signifying that it was the first time ever that they hadn’t advanced from the group stage.

In this tactical analysis in the form of a scout report, I will conduct analysis on why Germany failed at the 2018 World Cup and the tactics that resulted in this underperformance.

Matchday 1 vs Mexico – disorganised defensive transitions and rest defence

Löw’s side was built to attack. The starting 11 in this game contained players of high quality like Mesut Özil, Julian Draxler and Toni Kroos. Wanting to be offensively dominant is perfectly fine, and understandable when you consider their reputation and quality. However, the defensive implications always need to be evaluated and mitigated against.

Rest defence is a team’s structure when in-possession – one that is balanced and compact will help to counter-press effectively, thus likely regaining possession quickly after a turnover, which can aid with sustaining attacks. An optimal rest defence will subsequently reduce the potential chaos of a defensive transition.

If we think simply there are 10 outfield players; therefore, to ensure balance and occupation of all relevant zones, a 5-5 split between attack and defence may be advisory. Naturally, this can alter as you progress through the thirds, as well as if there is a level of technical superiority prevalent, which in Germany’s case is fair. Nevertheless, Mexico’s quality and strengths need to be factored in. This is a side that is set-up to counter-attack, possessing numerous players capable of progressing the ball swiftly and incisively. Mexico had 14 counter-attacks in total, compared to two for Germany, demonstrating the difference in styles and how the game panned out. The reigning champions preference was to ensure possession and look to play line-breaking passes. Meanwhile, Mexico was more direct in their play, but in terms of ball-carrying, not aerial passes.

Because offensive and defensive structures are intrinsically related you need to analyse the nuances of the German offensive structure in order to identify the reasons for it being so simple to bypass their defensive framework.

Whilst Löw picked a 4-2-3-1 on paper, the formation evolved once in-possession. The full-backs advanced high to occupy the wings in a response to the wingers drifting inside to the half-spaces and areas between the lines. This tendency by the likes of Draxler and Thomas Müller led to an increased reliance on Joshua Kimmich and – in this particular game – Marvin Plattenhardt to provide the width and stretch the defensive line, thus allowing for underlapping, depth runs to be more useful. This is a core principle of attacking play and in hindsight omitting Leroy Sané from the squad after a dominant season with Manchester City was a fateful decision considering the directness and pace he offers. Additionally, the full-backs’ role meant that they were often left stranded in these attacking positions during turnover moments, compounded by the midfield not rotating to provide depth in deeper areas.

In the initial phase of build-up, a 3-1 scheme developed. Kroos and Sami Khedira were the double pivot but were located on different lines. Kroos dropped to be alongside centre-backs Boateng and Hummels. This allowed simple ball progression from here, especially when you include goalkeeper Manuel Neuer. But although Khedira is better defensively than offensively, Kroos’ positioning resulted in one less player occupying central midfield. Therefore, during a defensive transition, there is a larger distance to travel before pressure can be applied.

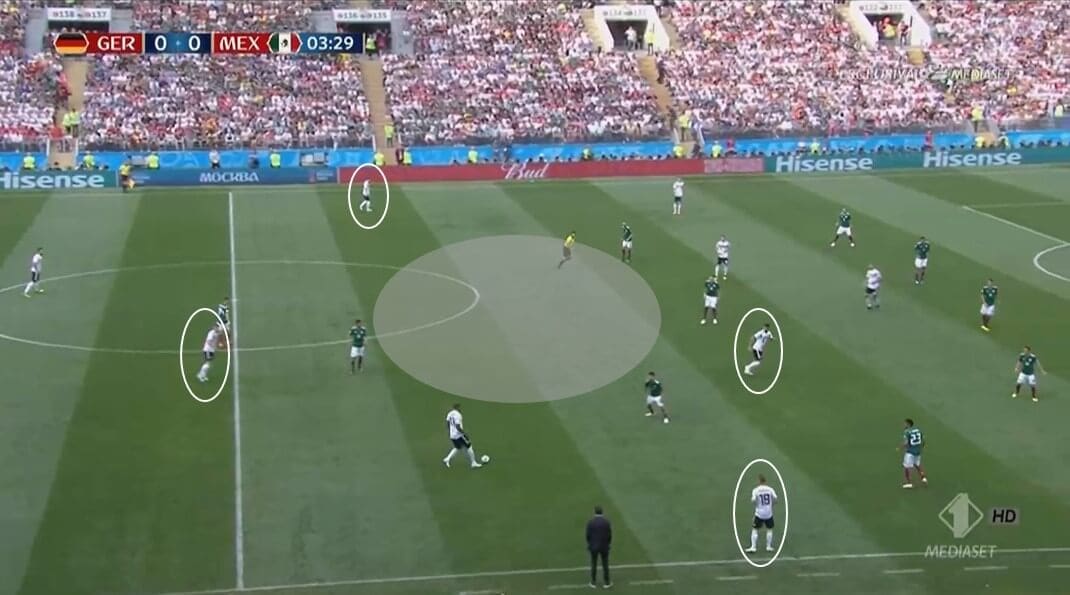

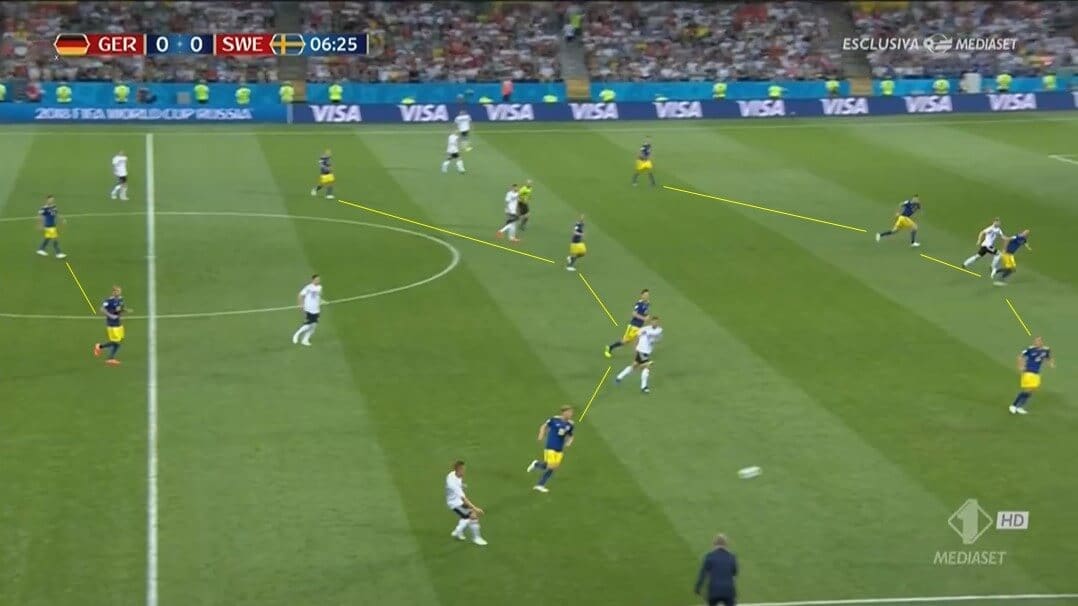

This aforementioned structure is visible above. Kroos is in between the two centre-backs with the full-backs wide. There are a number of German players situated in pockets of space, including Khedira who is higher than you’d ideally like. Subsequently, a large space has opened up centrally. Moreover, Mexico’s midfielders have a body-orientation that is compatible with a possible interception or a supporting run. Although no danger occurred here not constantly occupying such an important area of the pitch is rather risky.

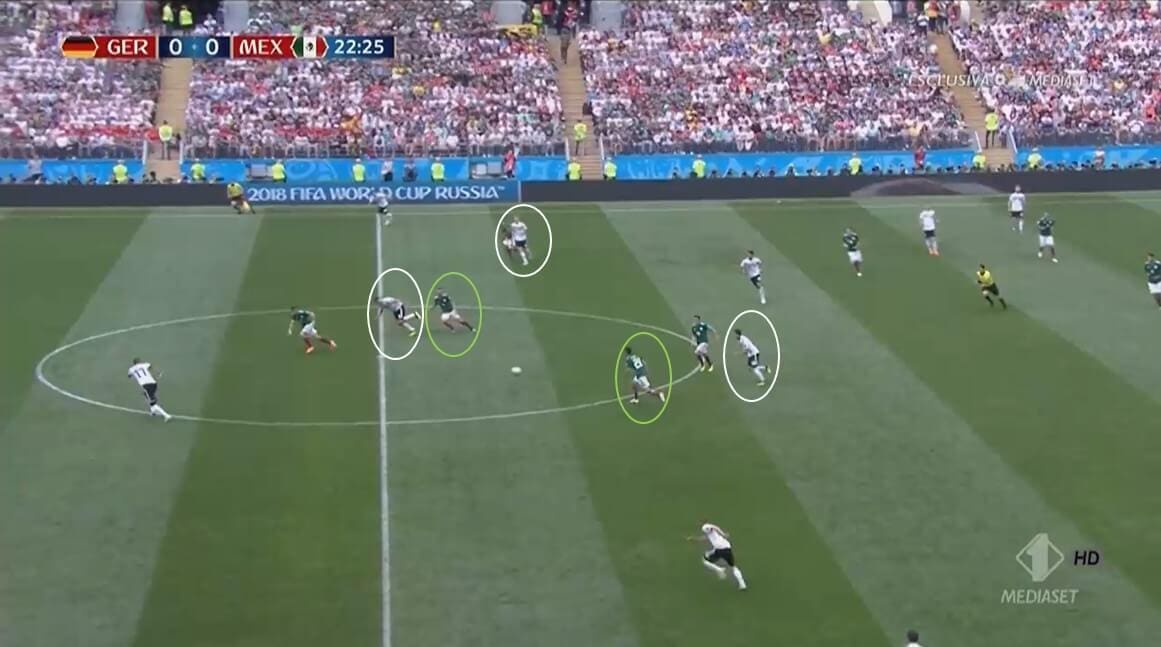

In this example, however, problems arise due to this. Hummels is tackled and loses possession with Khedira too high and Kroos wide-left. Suddenly Hirving Lozano is driving straight at the defence with teammates in support. Hypothetically, if Kroos was more central then he could either have offered an escape for an under-pressure Hummels or been closer to press, thus, perhaps prevent the threat from developing after the turnover.

That was an example whereby the original positioning and structure wasn’t optimal, but sometimes the actual execution of the counter-press was inadequate. Here the full-backs attacking instructions has left them ahead of the ball. The front four are also in no position to apply pressure. Kroos then doesn’t press the passer, cutting off the passing lane, nor does he drop off and be more conservative. Instead, a simple pass is played bypassing him.

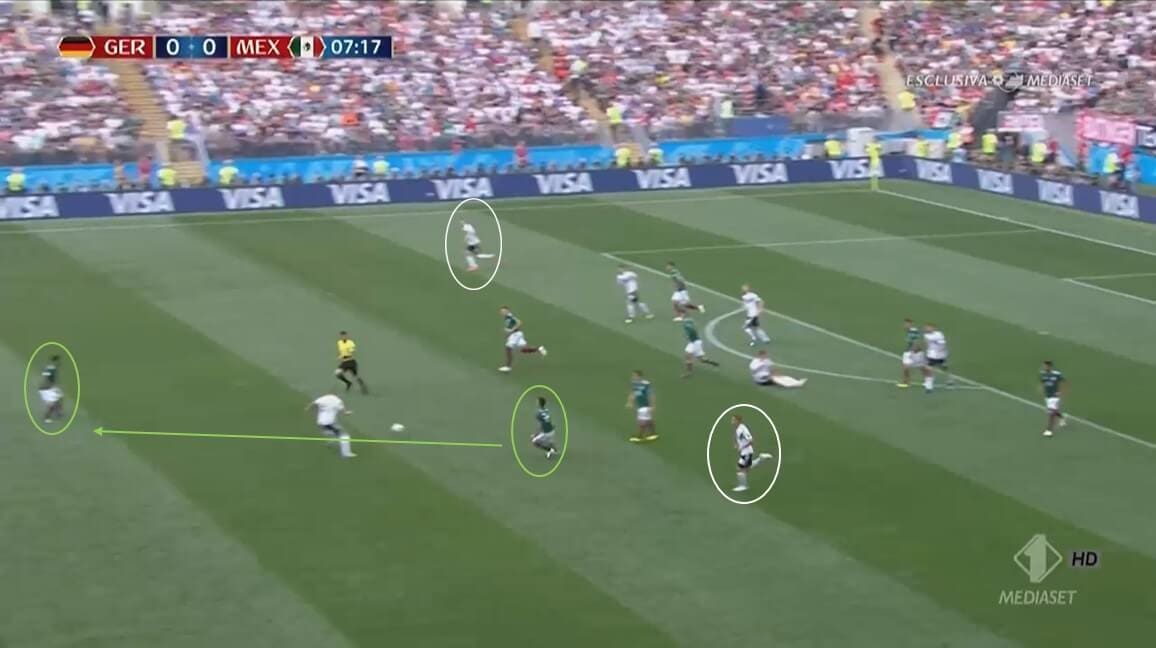

This next image shows the game’s solitary goal and the lead-up to it from an aerial view. Extremely high and wide are the full-backs with three players further forward in central positions. The box, made up of Kroos and in this case, Özil, plus both centre-backs can also be identified. Yet Kroos and Özil are located in their respective half-spaces, thus leaving the central channel free, of which there are three Mexico attackers ready to pounce.

In the next frame moments later, the effects of no direct presence centrally are evident. Hummels is forced to step-out to press Chicharito, but it is too late, allowing the ex-Man United man to enact a one-two with Andrés Guardado. The eventual scorer Lozano is beginning his run at the bottom of the picture, on the blindside of Özil. Below, the benefits of this run are shown, with the Napoli player exploiting the space meant to be covered by right-back Kimmich.

Matchday 2 vs Sweden – Going around the defensive block rather than through it

Versus Sweden, Germany continued with the same structure in-possession that they operated with against Mexico. This meant that the full-backs maintained their offensive mindset, therefore allowing the wingers to adopt central positions between the lines. An undue reliance for width was placed upon Kimmich and replacement left-back Jonas Hector, an offensive principle that was especially needed in this game because of the Swedes deep block.

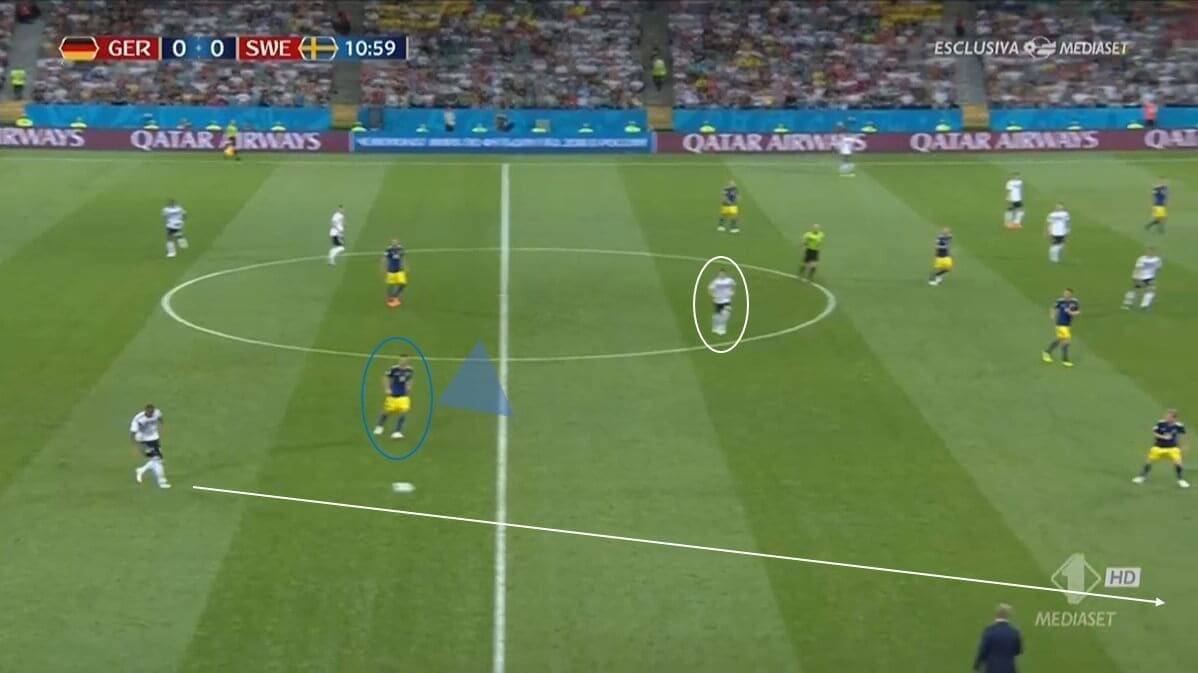

Sweden’s squad profile is quite different from that of the Mexicans. They don’t possess as much flair, pace and dribbling qualities and have a more functional approach. The Swedes long pass share percentage was 17%, 5% greater than the Mexicans. Furthermore, their overall game plan was to be passive in defence, subsequently recording a PPDA of 22.7. As they didn’t tend to leave this structured shape for extended periods of time a burden was placed upon Germany to break the Sweden defence down. This control is reflected by them having a hefty 77% possession. In the image below, the mid-block that Sweden adopted is clear. They applied more pressure in wide areas, where they could collapse on the ball-carrier to shut off passing lanes, which would be reduced anyhow due to the ball location.

The scheme whereby Kroos fell back into the defensive line also remained here. However, with just Sebastian Rudy in central-midfield, combined with two Swedish attackers, meant that play could be directed out into wide areas, which was helpful to the Swedes’ tactics. Additionally, the 3v2 present in this first phase naturally saw the ball levitate to Boateng as the situational right-centre-back or Kroos on the left-hand side of the situational three. These factors contributed to attacks being concentrated down the flanks – 60 of Germany’s 74 attacks came down either the right or left flank.

This example above illustrates this in-action. Marcus Berg’s positioning has closed off the diagonal passing lane to Rudy, forcing Boateng to play a long line pass to Kimmich, defending this space is a simpler task for Sweden defenders. Plus, Werner’s best attribute is not his aerial ability, standing at 5’9”. Crossing becomes more important and prevalent against a deeper-sitting, compact side; Germany attempted 45 crosses throughout the game.

With the prominence of the full-backs in the final third, Germany needed to conduct an increased number of depth runs. If the runner is not tracked, he offers a dangerous ball in-behind for an excellent crossing or shooting opportunity. Conversely, if they are then occupying a defender it can open up the half-space for a teammate to exploit.

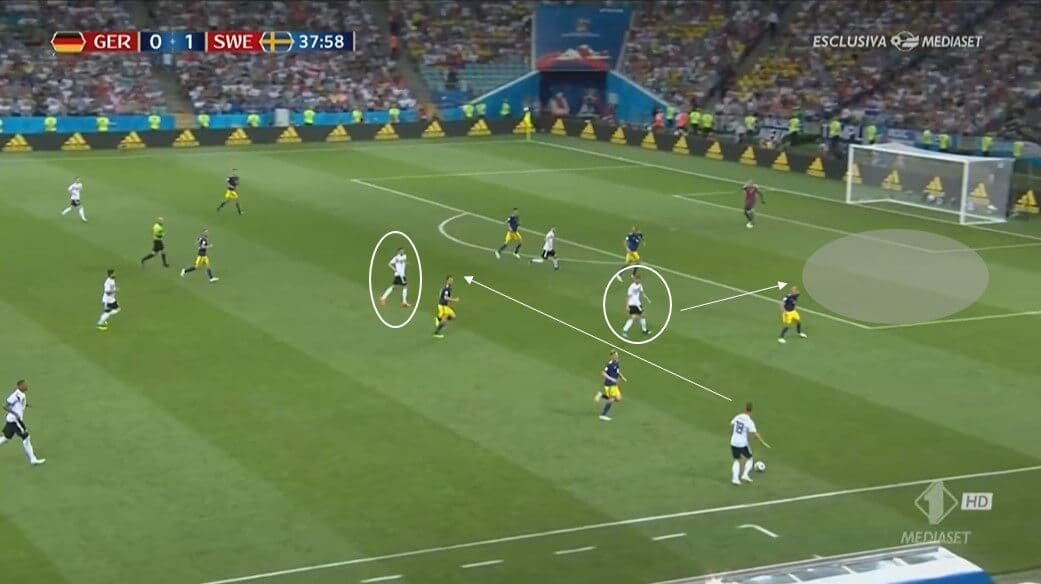

Above is a scenario where this movement is possible and would be effective in the creation of space. Kimmich has possession in an advanced, wide area of the pitch – a common occurrence thanks to his role in the system. Right-winger Müller is located in the half-space, in a nice pocket between the lines. Nonetheless, if the Bayern man looks for an underlap between the Sweden centre-back and left-back he can drag a defender deeper, thus unbalancing their structure. This decoy run would free Draxler centrally with superb body orientation if found, or allow an easier pass to Werner who could lay-off to Draxler himself.

Another similar situation ensues here. Werner is making a run in behind the full-back, thus creating space where he currently is. However, compared to the last example, there is not a teammate located in a position whereby they can capitalise on this space. Added to this, a successful pass to the RB Leipzig man would be difficult to complete.

A 4-4-2 defensive structure has three lines to it. This has the potential to leave large amounts of space between those lines, due to the little staggering apparent within the initial formation. Germany’s attacking scheme in which the wingers come inside and the full-backs push forward can overload the four in either the first or second line. This numerical superiority will nearly always leave a ‘free man’, as long as the right movements are made. Nonetheless, the Germans didn’t utilise this enough, instead of going wide – sometimes forced by the Swedes’ own tactics but other times at their own choice.

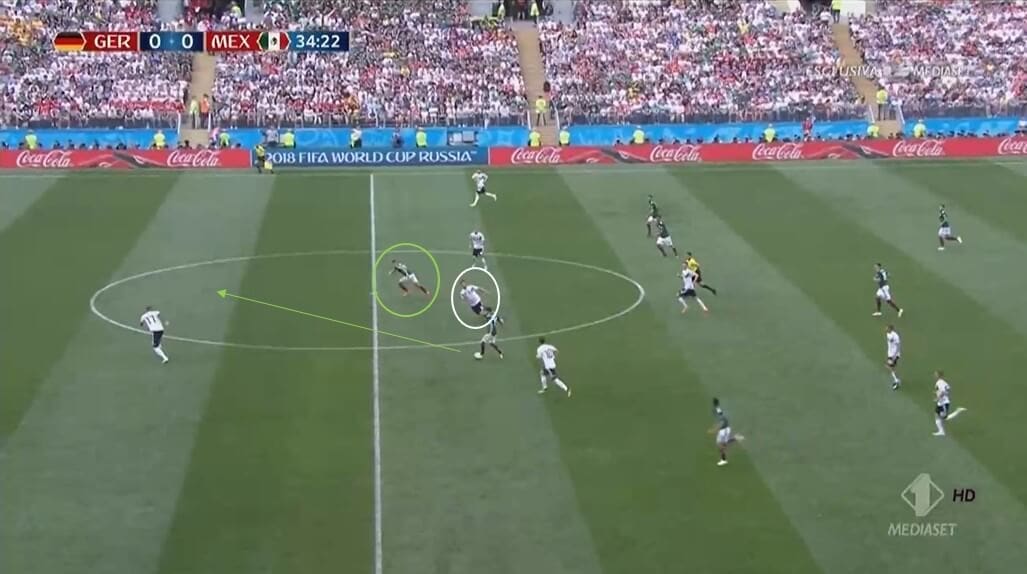

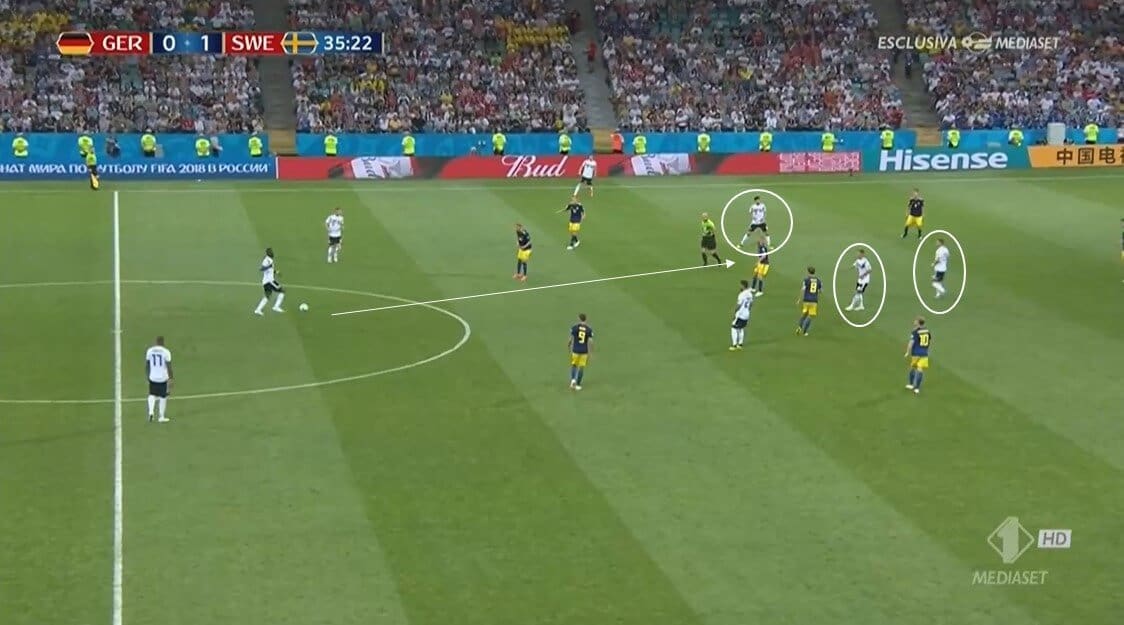

In the image above Antonio Rudiger is forward-facing and central. There are three Germany players situated between the lines and if one receives a defender will be forced to either step out and vacate dangerous space behind him or allow them to receive under little to no pressure. Rudiger, however, opts against such a pass instead circulating the ball to a wide position – showing a lack of penetration and ambition. A win was only managed in the last minute via a direct free-kick from Kroos.

Matchday 3 vs South Korea – Spacing problems

After saving themselves against Sweden, a win here would almost guarantee progression into the knockout rounds. South Korea meanwhile had lost both their previous games; it seemed it could only go one way.

Spacing is a crucial aspect of a team’s offensive play. Players need to occupy the correct channels and areas, but not congest them, which would simplify defending for the opposition. Germany encountered problems with this in their initial ball progression, and in the final third. The essential purpose of spacing is to laterally stretch the defensive line, inevitably opening up gaps to exploit. But, of course, the passing lane through these gaps must have someone who can receive.

The pivot space is arguably the most important area of a football pitch. It is the heart of a team, where much ball progression and circulation stems from. In the image above this area is empty. No.6 Khedira is too deep while Kroos is on the far-side in the left half-space. Further forward the attackers are positioned well, they are therefore effectively pinning the South Korean second line. If Khedira was more advanced he would have time to find and complete the right pass or engage a defender to free a teammate.

This next example portrays how space could be under-used in attacking areas. Firstly, there is an unnecessary amount of people behind the ball relative to the defence of South Korea and time on the clock (76th minute). Furthermore, a significant portion of space has opened up, in an area of the pitch which is desirable for the Germans to have control in. Not having anyone available here to receive in such an advantageous position illustrates extremely well the problems Germany had.

Here, width isn’t being maximised enough. No.9 Werner should ideally be closer to the touchline to give him more space and time or to get the full-back to engage him, thus opening up the half-space. Moreover, there is no presence on the left-flank. This means that the opposition right-back can solely focus on those in front of him, and not have to worry about leaving a left-winger in vast amounts of space. Optimum spacing generates dilemmas for defenders in the coverage of space – too often, however, Germany were muddled and unbalanced when in-possession.

Conclusion

To be truthful, their showing in this tournament was poor, albeit not horrific and there is a rationale behind how Löw kept his job. Throughout all their games though they only led essentially for a single minute – against Sweden. Nevertheless, by analysing their xG totals then perhaps blame can be placed at the attacker’s door for their poor finishing. The Mexico game saw them register 2.70; Sweden, 1.55 and South Korea, 2.59. They only scored twice, however, with one straight from a free-kick.

I believe the lack of a direct winger in the final squad was a major mistake. Sané’s exclusion was baffling after his exceptional season in the Premier League. Undeniably there were times where his dribbling capabilities and pace would have been most helpful. For example, Leon Goretzka started at right-wing versus South Korea. Wingers that tended to hug the touchline would help the other attacking players to employ their skills to a greater extent through opening up space centrally. It will be interesting to see whether Löw and his team can succeed once more next summer at the Euros.

Comments