After being relegated from the German Bundesliga in the 2017/18 campaign for the first time in their history, Hamburger SV appointed four managers in four seasons trying to win the promotion to get back where they belong: The top tier.

The fifth and most recent, Tim Walter, is probably the definitive and the most promising one, not only because of the results but also for the innovative and attacking game plan that his team deploys week by week.

Season by season, they have been always too close to the third spot of the 2.

Bundesliga.

Last year under Walter, they finally got to third place in the table which allowed them to play the promotion-play-off with the 16th placed team in the Bundesliga.

On that occasion, it was Hertha Berlin that were defeated in the first leg at home by Walter’s players by 0-1, but they were capable of making the comeback and winning 1-2 on the aggregate in the second leg.

After a new setback, Walter stayed with the club, the first one to do it for more than one season after the relegation to the German second division.

They sit top of the league with an interesting-attacking style and a more solid defence.

Let’s take a look at the tactics deployed by Tim Walter.

This tactical analysis piece will be a team scout report of 2.

Bundesliga side Hamburger SV early into the 2022/23 campaign.

Rotating back-four and use of the goalkeeper in-possession

Tim Walter has set up his team to be as mobile as possible when they start the build-up.

Daniel Heuer Fernandes, the 29-year-old goalkeeper is a vital part of the team thanks to his tactical intelligence and short-term distribution.

The full-backs play another vital role as well as the centre-backs because the four of them are making often moves through the midfield and wide-central areas.

When you think of a goalkeeper being utilised in possession of the ball, you think of players like Pep Guardiola‘s goalkeeper Ederson, or Liverpool‘s Alisson.

Those like to get on the ball close to his goal, trying to attract the first line of pressure, but Heuer Fernandes’ role goes beyond.

Normally in almost every football match played in this moment around the world, we see a 10vs10 with goalkeepers not being that present in various phases of the game.

That makes it easier for teams to press two ball-playing centre-backs with three players or two-against-two, so Walter creates a risky but interesting plan: The goalkeeper has to play almost as another centre-back in the build-up phase of the game.

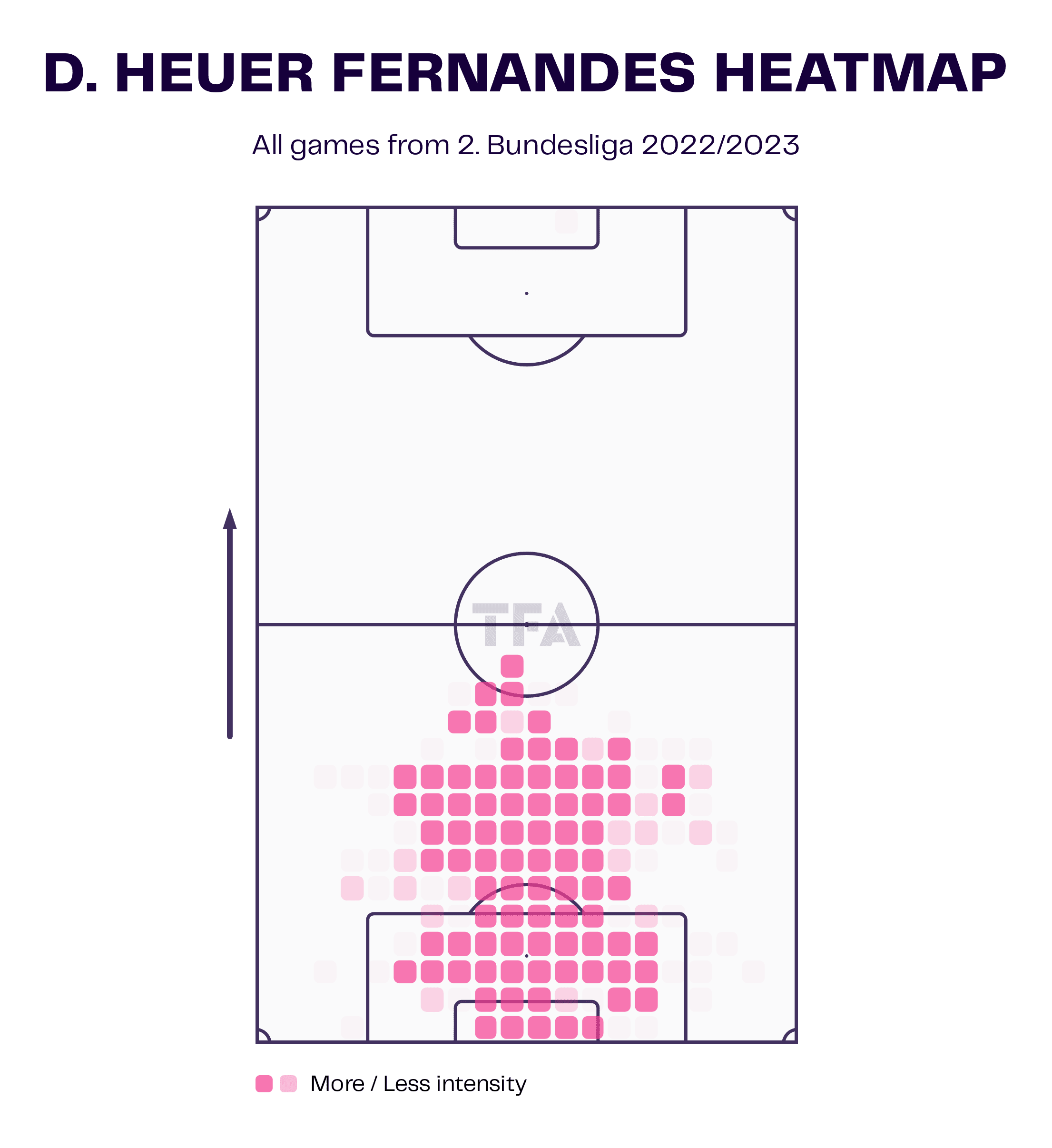

Let’s take a look into which areas of the pitch, the German-Portuguese goalkeeper uses to develop his game in Hamburger SV.

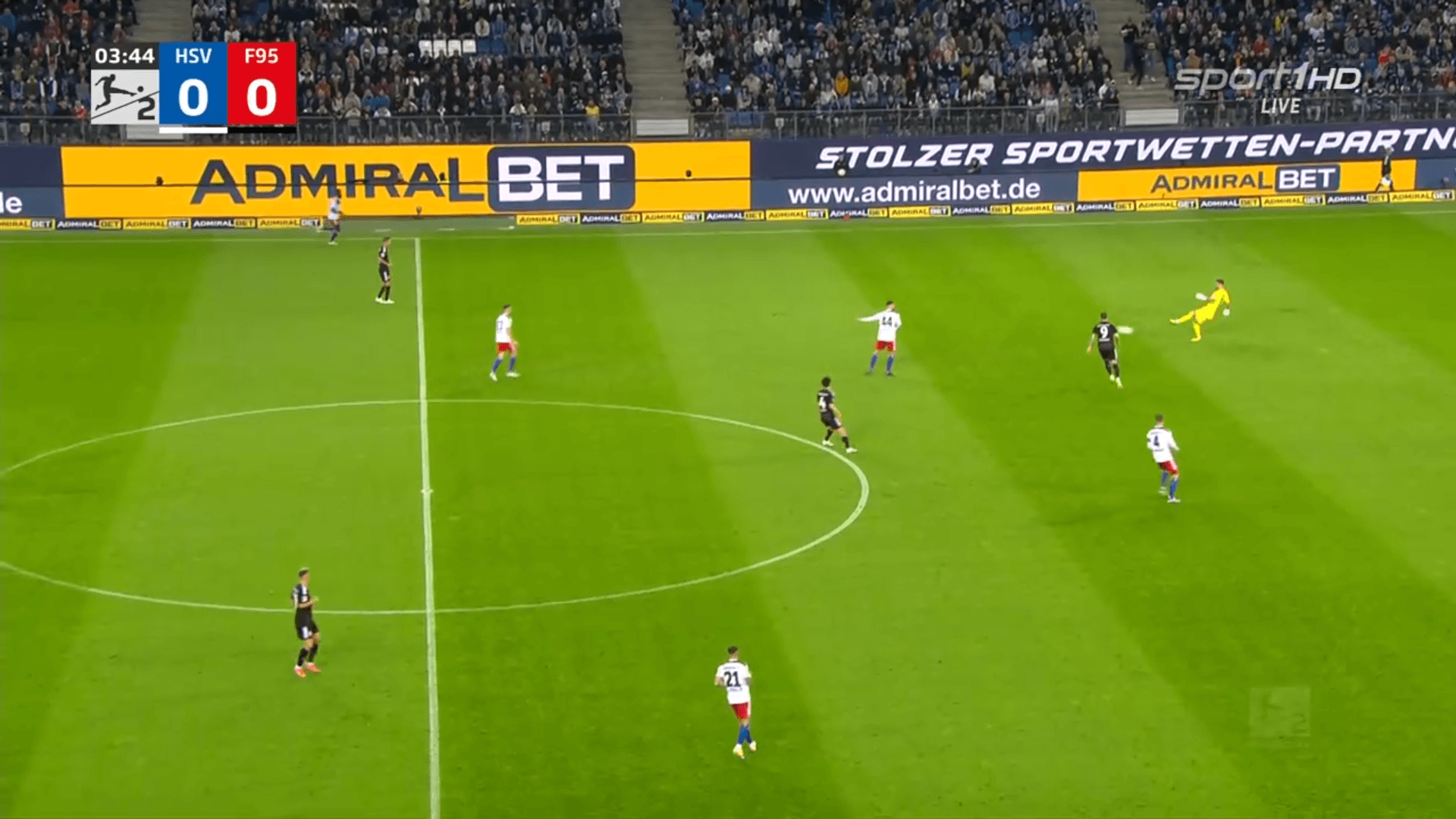

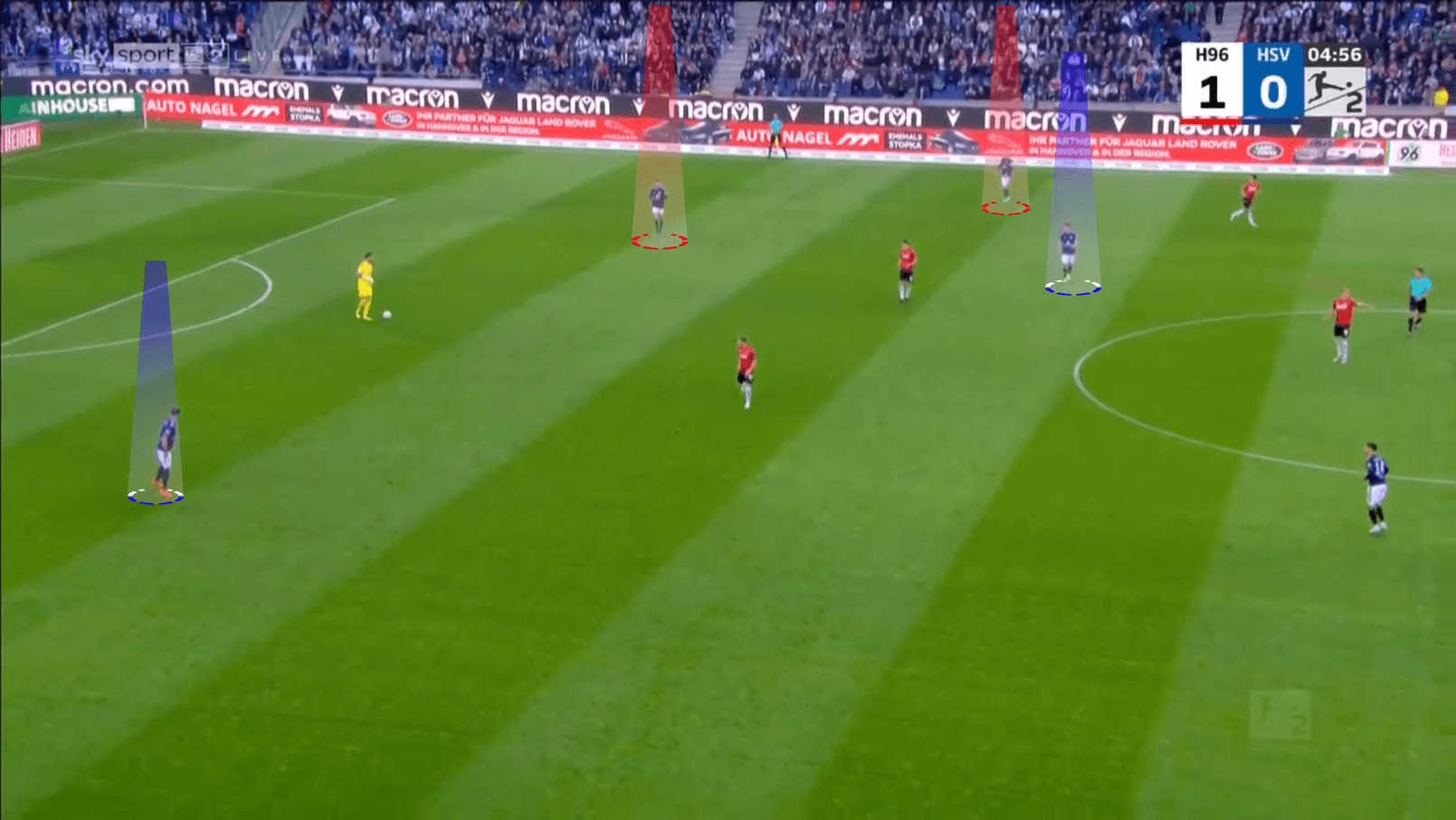

As we can see in the example below, Heuer Fernandes is commanded to play in a high block, next to his centre-backs where he can create numerical overloads against the first line of pressure and execute through passes to make his team progress in two-three passes.

The back-four commonly is composed of left-back Miro Muheim, left-centre-back Sebastian Schonlau, right-centre-back Mario Vuskovic and right-back Moritz Heyer.

The idea of playing very high and actively in touch with the ball is clear: they can make every build-up easy because they are always playing 11v10 in this phase of the game.

But Walter adds more interesting features to his game style, and this is when it enters the full-rotating back-four, including Heuer Fernandes who joins several times the first line as a centre-back.

Hamburger’s system is a very complex one, but they have repeated movements that help them to create spaces and accelerate possession.

So let’s take a look at one of the most usual rotating moves.

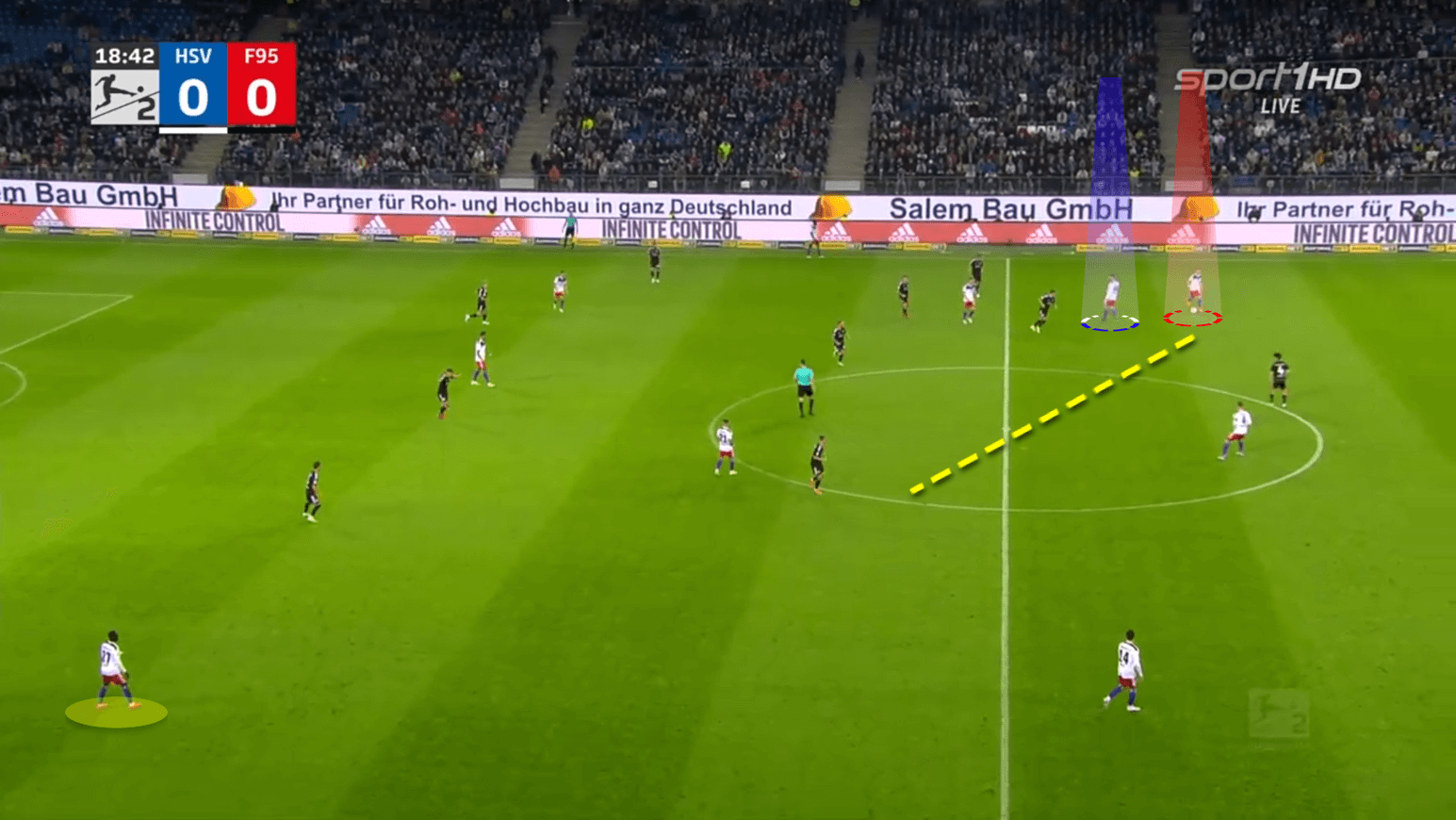

This time, the goalkeeper is not that close, but the back-four does great to understand where they have to stay or go.

The red one is the left-back, who has recognised the rotating situation after the blue one (right-centre-back) has dragged his marker up the pitch.

That liberates space in front of the full-back to drive the ball (yellow line) and take a long pass to the winger.

This movement is one of the blueprints of Hamburger, from both full-backs.

They receive the ball and drive into the middle to find a player in wide areas or in half-spaces.

This kind of overload happens every time the defenders are on the ball.

Heuer Fernandes gets close to them, and they start to rotate all over the pitch.

Almost every time the centre-back from the strong side of the ball starts them, then one of the full-backs moves to play as a midfielder, the other one goes to the centre-back spot and the other centre-back congests the central areas.

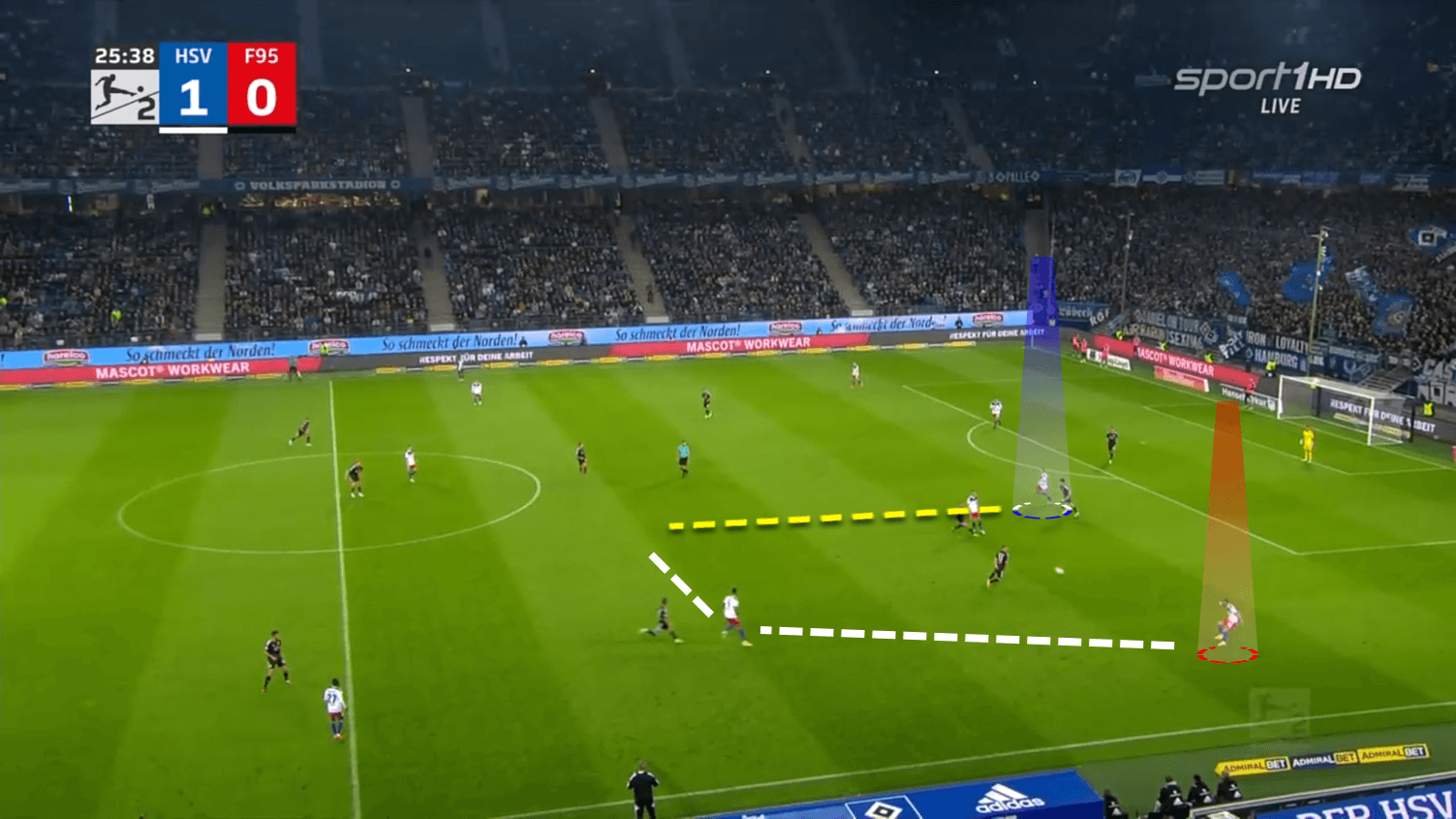

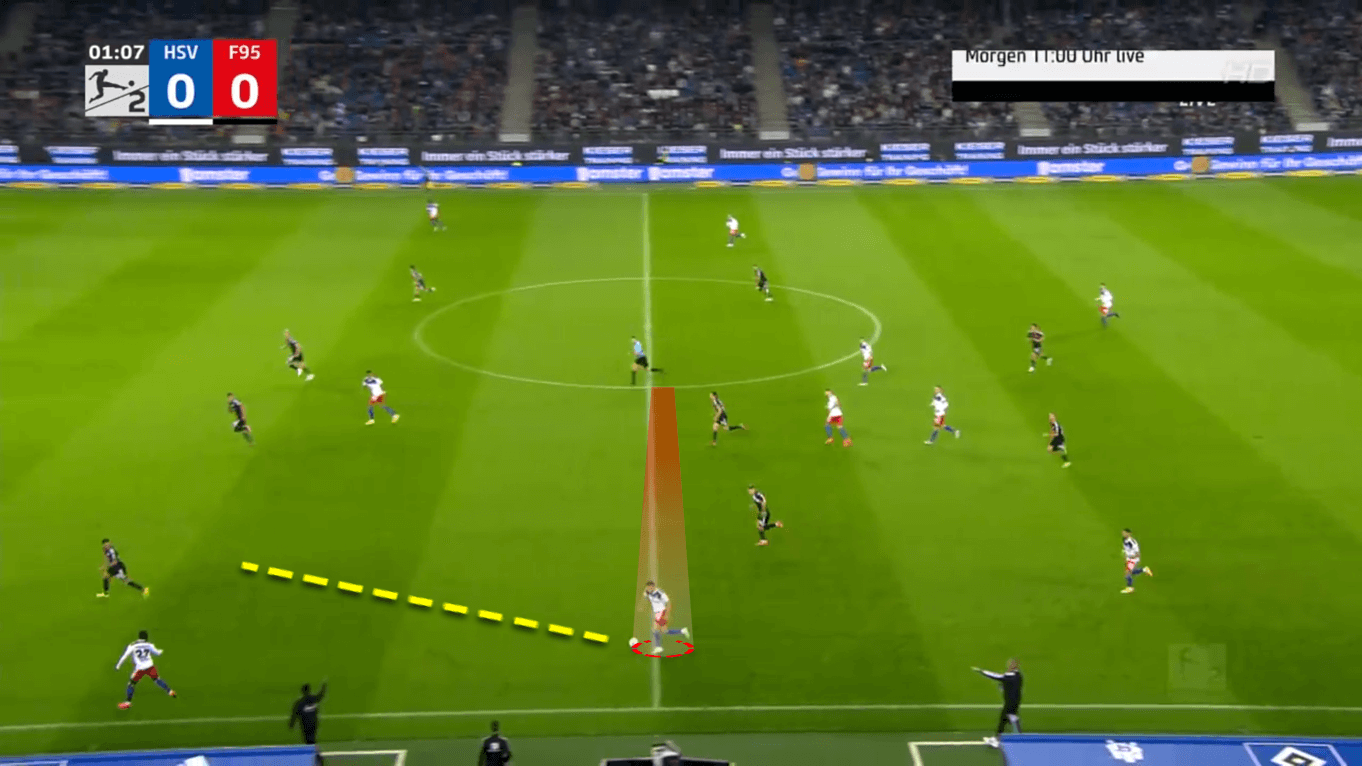

As we can see in the example below, this is another display of why they do these and how they escape a high-pressing situation.

The right-centre-back (blue) plays the ball to his right-back (red) and instantly makes the run to the middle (yellow line).

The midfielder gets back to cover him and a ball progression situation is created.

He can pass it to Robert Glatzel (centre-forward), who has dropped, and then he could play it on the half-turn to the centre-back making the run, but instead, the full-back decides to play out wide.

Nevertheless, this is replicated in every build-up so they are constantly finding the best options to progress.

Another example was here against Hannover, where they have to play against a more compact team in defence.

The blue ones are the full-backs and the red ones are the centre-backs.

Schonlau had the task of dragging their forward to open space, and he did it quite well, but in this situation, he goes very wide and his left-back is playing as a central midfielder.

Heuer Fernandes on the ball has the time and space to execute a pass to the right-midfielder, who is free in the half-space thanks to the numerical overload.

Obviously, questions are asked: What they can do with this? Is it a risky idea? How do teams defend against this? And more questions that a complex and confusing but working system is generating in fans’ heads.

First of all, the rotations are made for two things: overloading the central areas to find quick and direct players out in the wings to turn calm and slow possessions into chaotic attacks within 3-5 seconds.

If you put more players in those zones, the opponents are going to be attracted there and leave free space wide, where Bakery Jatta, Jean-Luc Dompé and Sonny Kittel are having fun this season.

The other thing is confusion.

This rotation gets players into several questions: should I go with the right-back? But what about the centre-back? And the goalkeeper? This last is an interesting one.

Why can’t players simply go and press the keeper, tackling him and scoring? The answer is: you are going to stretch your team and leave space behind, that Laszlo Bénes (playing more as a 10 travelling through half-spaces) or Ludovit Reis could find and carry the ball forward.

Also, Heuer Fernandes is a top player under pressure, so trying to beat him in a 1v1 is very tough.

So how can teams defend this and how not? Hannover made a good example of how they closed down some passing options that weren’t enabled, beyond the mobility of the Hamburger players.

They were very compact, not pressing that high, narrowing the field and avoiding these movements playing in a solid mid-block that had coordinated triggers for the players to go and get back.

Although, Hamburger were able to beat that block several times.

High-presses are always beaten by Walter’s side.

Rivals try to get closer to them, pushing it closer to their own penalty box, but they end up getting confused with which player they have to mark, and in 4-6 seconds Hamburger are able to break the pressure with rotations.

Is it risky? Of course, it is, but football wouldn’t be what is if managers didn’t have risky ideas and plans.

We can see against Hannover, the first goal was scored after a turnover of the centre-back, that leaves the ball to the opponent’s striker and he’s quick to strike the ball and celebrate his goal because the goalkeeper was out of his line and the other players were in different zones of the pitch.

Direct build-ups and attacking from the wings

After Tim Walter’s players break the first line of pressure, the roles of László Bénes and Ludovit Reis enter the match.

The first one, in a more attacking midfielder role, and Reis as an ‘8’, but both of them with clear idea of what to do when in possession: one or two touches of the ball to then release it quickly to the winger or the overlapping full-back.

Bénes with a more aggressive style looks to penetrate into the box and shot from outside.

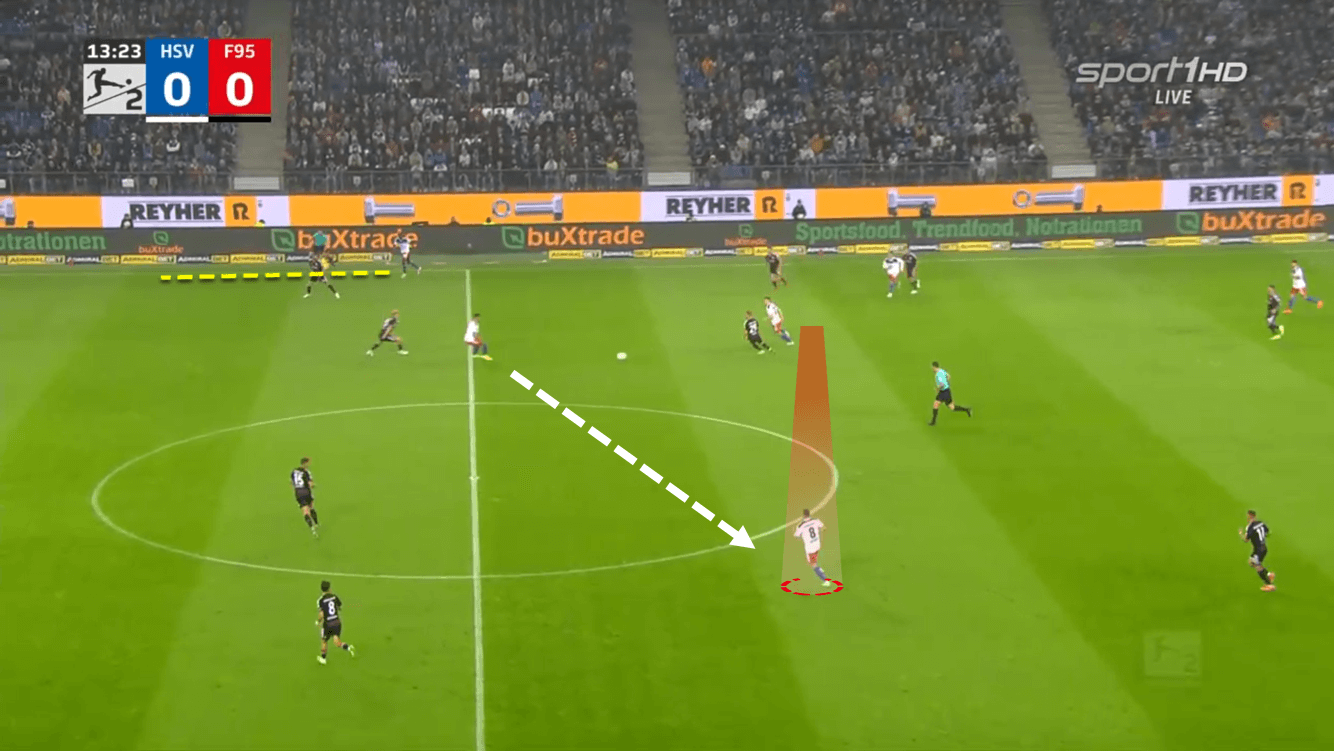

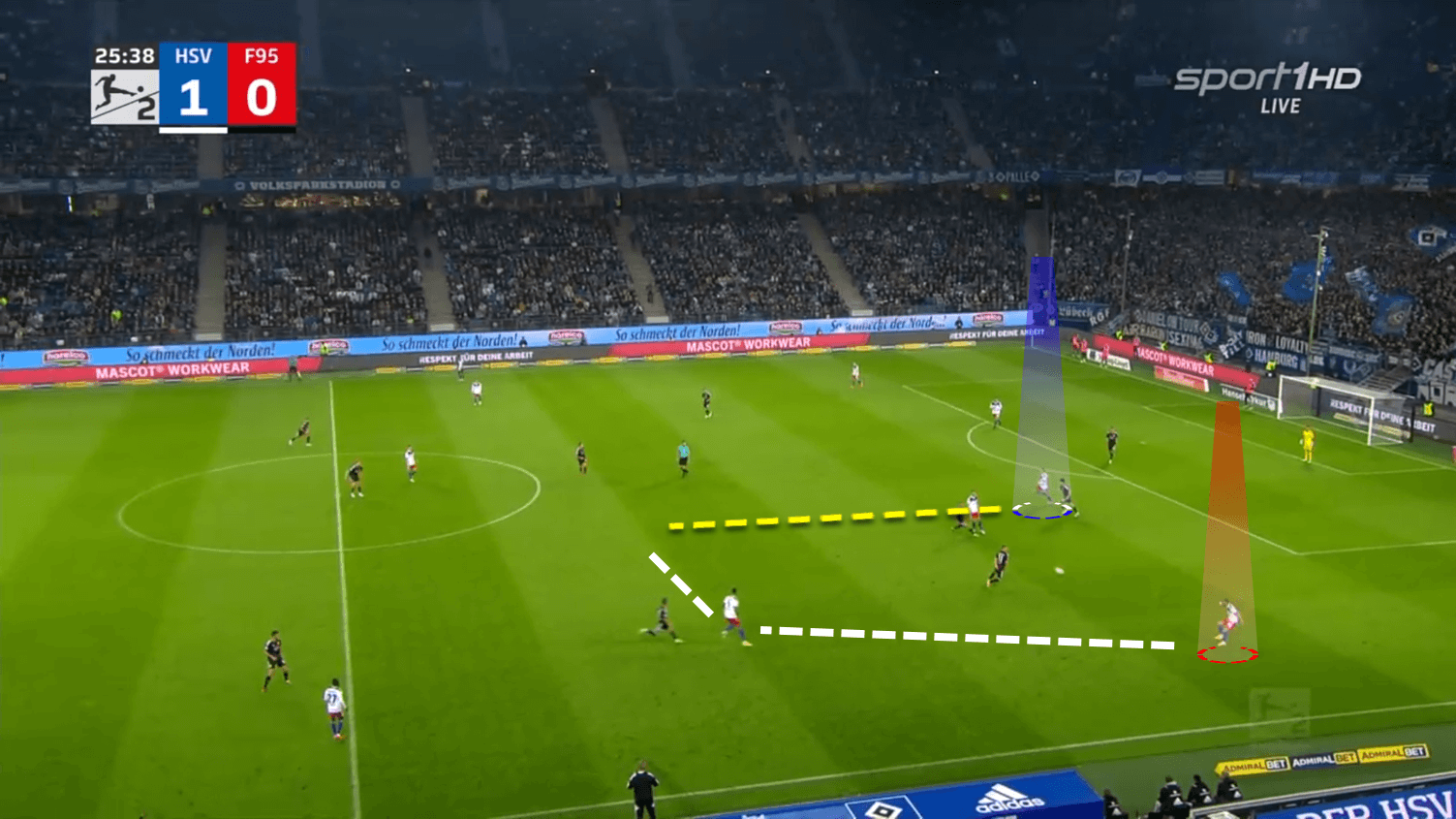

The picture below shows us a common direct attack from Hamburger.

They have broken the pressure and they’re now into an attacking moment.

Robert Glatzel drops and plays a pass to Bénes, who then finds Bakery Jatta on the wing with space to run.

As a direct team, players have the freedom to run with the ball, to carry the ball forward with speed and aggressiveness to get into the box and find someone in a goal-scoring position or find the net themselves.

On this occasion, we see again Bénes receiving the ball after the centre-backs rotate and created overloads to progress.

He then makes a run to the penalty box and strikes a great shot that crashes at the woodwork.

One of the most common attacking phase systems was the overlapping full-backs and midfielders making runs into the box to then execute cut-back crosses.

As well, wingers were able to run through their wing to then cross to the weak side and find Glatzel or the other winger.

As we can see, Sonny Kittel, who has recently subbed in for Bénes, makes the run perfectly through the full-back and centre-back to then make a cut-back cross to Bakery Jatta who heads it and celebrates the win.

They also skip sometimes some steps of the build-up and find wingers through long-balls of their centre-backs, or making an attacking transition after a corner.

The principles of the attack are very simple but the ones that work the most are runs in behind, carries, wingers that can dribble and strikers that score tap-ins or headers.

Pressing

Getting into the final part of this analysis, we’re going to see the defensive phase of Hamburger SV, a department where they were having troubles last season but they have been very solid with a counterpressing and high-pressing ideas.

Usually, they set up a 4-4-2 to press higher on the pitch, but they can shift to a 4-3-3 to sum up more attackers to try and steal the ball closer to the rival goal.

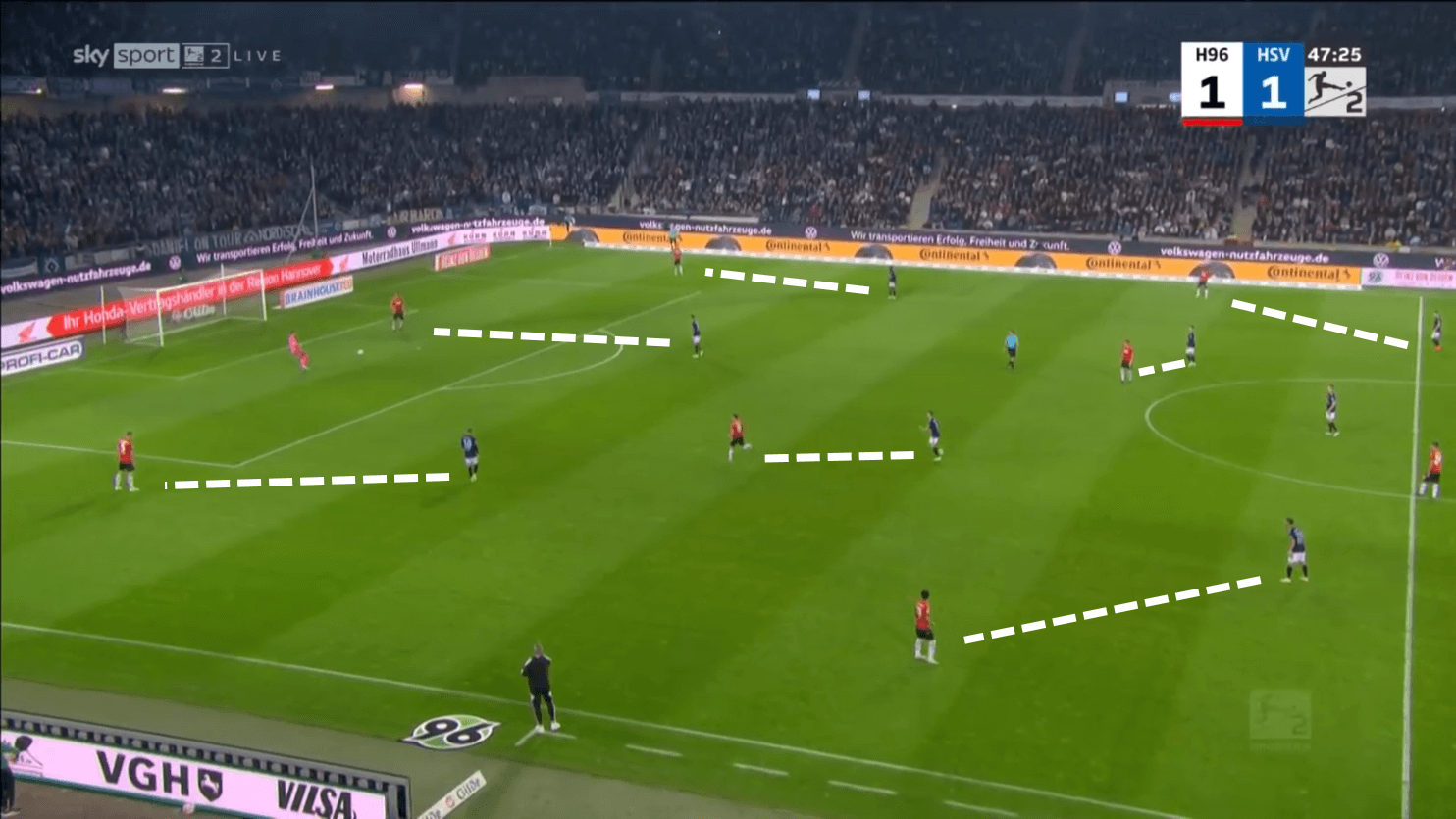

This example against Hannover shows their shape in a 4-3-3 when defending where the left-winger marks zonal the position of the right-centre-back, the striker marks the centre-back, and the right-winger marks the left-centre-back of the back-three.

Then, the midfielders go a bit closer to rival midfielders, deleting them as a passing option, and finally, full-backs are high and close to wing-backs.

In the next picture, we see how Hamburger SV sets a high-block and their shape in a 4-4-2.

László Bénes is the one who joins Robert Glatzel to form a strike pairing, where the Slovakian suffocates the man on the ball and shadows his option behind.

Glatzel is aware of the other centre-back, the wingers go with high full-backs and again, the midfielders (in this occasion Reis and the ‘6’ Jonas Meffert) stay very close to the rival midfielders.

This can either force the rivals to play long balls or be robbed in high zones of the pitch.

Even Hamburger SV win the ball more in the middle third, where they narrow the field and can intercept passes or tackle opponents in tight spaces.

Conclusion

Hamburger SV is an interesting side that could be on their way to finally getting back to the Bundesliga, thanks to the great job Tim Walter is doing down there.

With only 10 games played this season, they will have to maintain their consistency, energy, tactical intelligence and defensive coordination to keep fighting for the mostly desired comeback to the top tier.

It should be interesting to see if this risky idea would continue in the first division, but it has shown us recently that goalkeepers can be used in a different way, and centre-backs can play with their back to rivals’ goals.

Comments