Gabriel Heinze was a tough, aggressive defender who played at the highest level for club and country, before now moving into management in his native Argentina. After a short spell at Godoy Cruz, Heinze made the move to Argentinos Juniors, where success led him to his most recent club Velez Sarsfield, who he recently departed. Heinze took the then relegation threatened side and in under one and a half seasons boosted them to third place in the Argentinian Superliga, despite Vélez having the second youngest squad in the league.

Heinze achieved this through a brave, offensive, usually possession based style of football which he attributes to Marcelo Bielsa’s influence on him, and the influence is clear for all to see. In this tactical analysis, we will look at Heinze’s philosophy and explain why following his exit from Vélez Sarsfield, the Argentinian is likely to be an in demand coach across Europe.

Build-up structures

Heinze has employed a range of build-up structures and tactics, with each one being applicable in different circumstances. As a result of these build-up structures, Vélez’s usual offensive structure is a 3-4-3, with multiple variations of it which will be discussed.

One of the most common build-up structures Vélez use is a back three against front two presses. This allows for the first line of the press to be stretched in a 3v2, and allows for centre backs to take up wider positions due to an extra player providing coverage as opposed to a back two. To form this back three a defensive midfielder is often used, which gives more options in how they build.

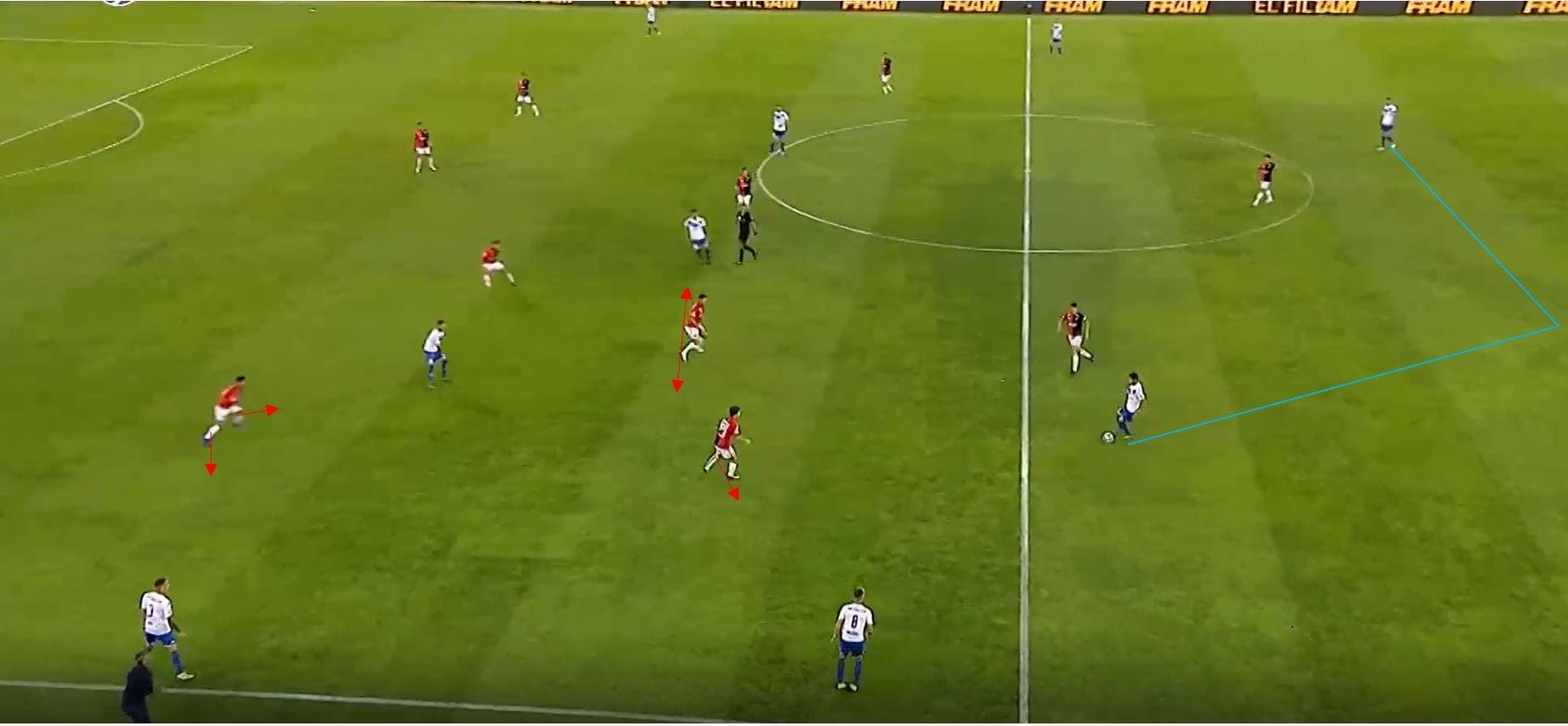

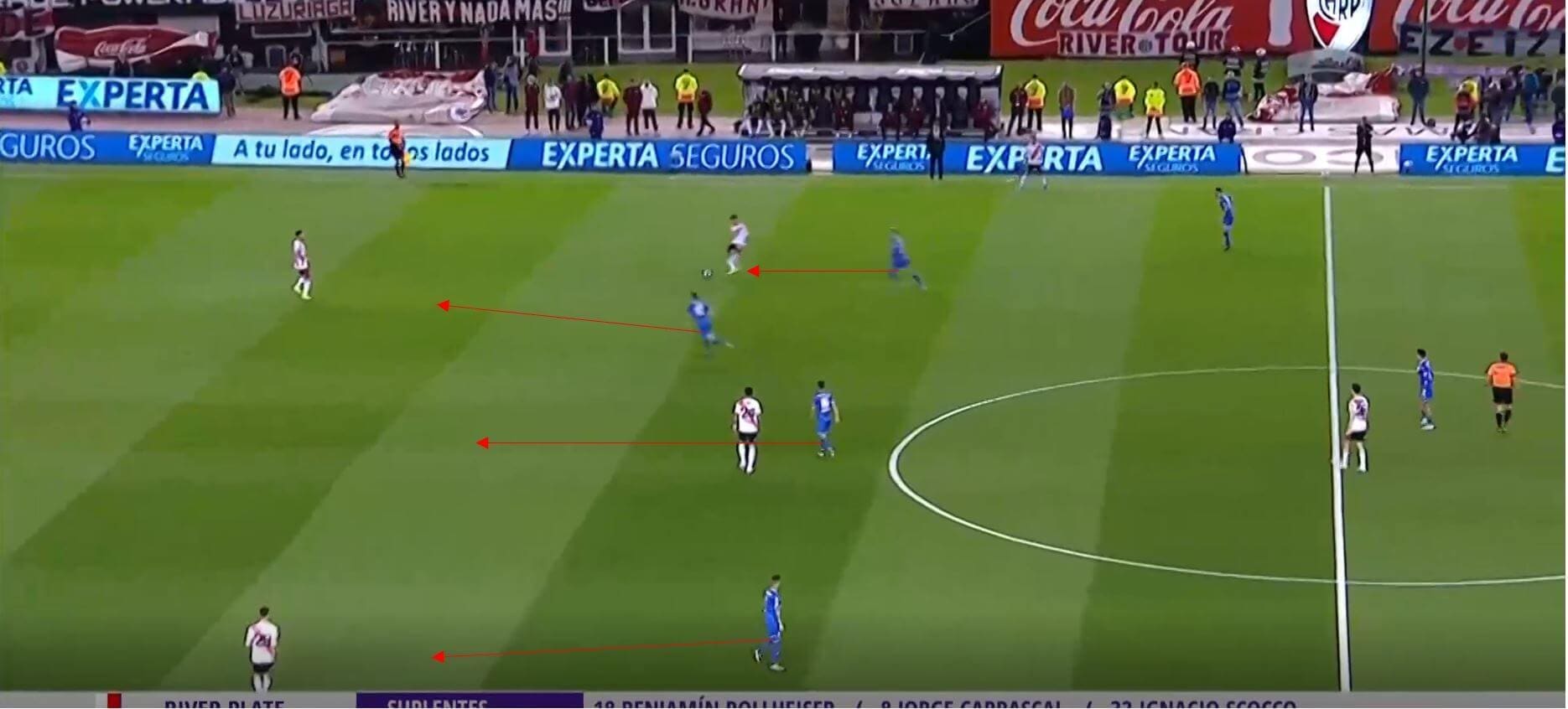

Vélez use their back three for this reason, and as in all of their build-up structures, usually leave players higher up the field and use positional play in order to create and utilise space. We can see a prime example of this below, with the back three stretching a front two press initially. This stretching means the second line can now be occupied by the ball carrier, as the player is free to play passes with no pressure. As a result, the winger is usually triggered to press the ball carrier, or at least has to react in some way. Vélez then use their positional play to create decisional problems for each player, as we can see here. Width is provided both on the winger and opposition full-back, while the ball near the central midfielder also has to monitor the central passing lane. These decisional problems mean defenders can’t occupy one space or the other, and have to take up positions halfway in between each, which is not ideal.

As a result, Vélez are able to progress through the central lane, after the ball is played to the nearest wide player, where again the player nearest to the receiver still has two players to occupy, and the nearest central midfielder looks to protect the lane towards the striker.

We can see another good example of this here, again against a deep sitting team. The two man first line press is stretched and overcome by the back three, and the wide centre back has time to drive forward, occupying a central midfielder in the second line. The central midfielder moves out to press, which opens up the half-space which is well occupied. Again notice how the wide player is occupied by a player off screen, so cannot protect the half space. This space occupation further up the field is something I will discuss later.

Back three with line breaking movement

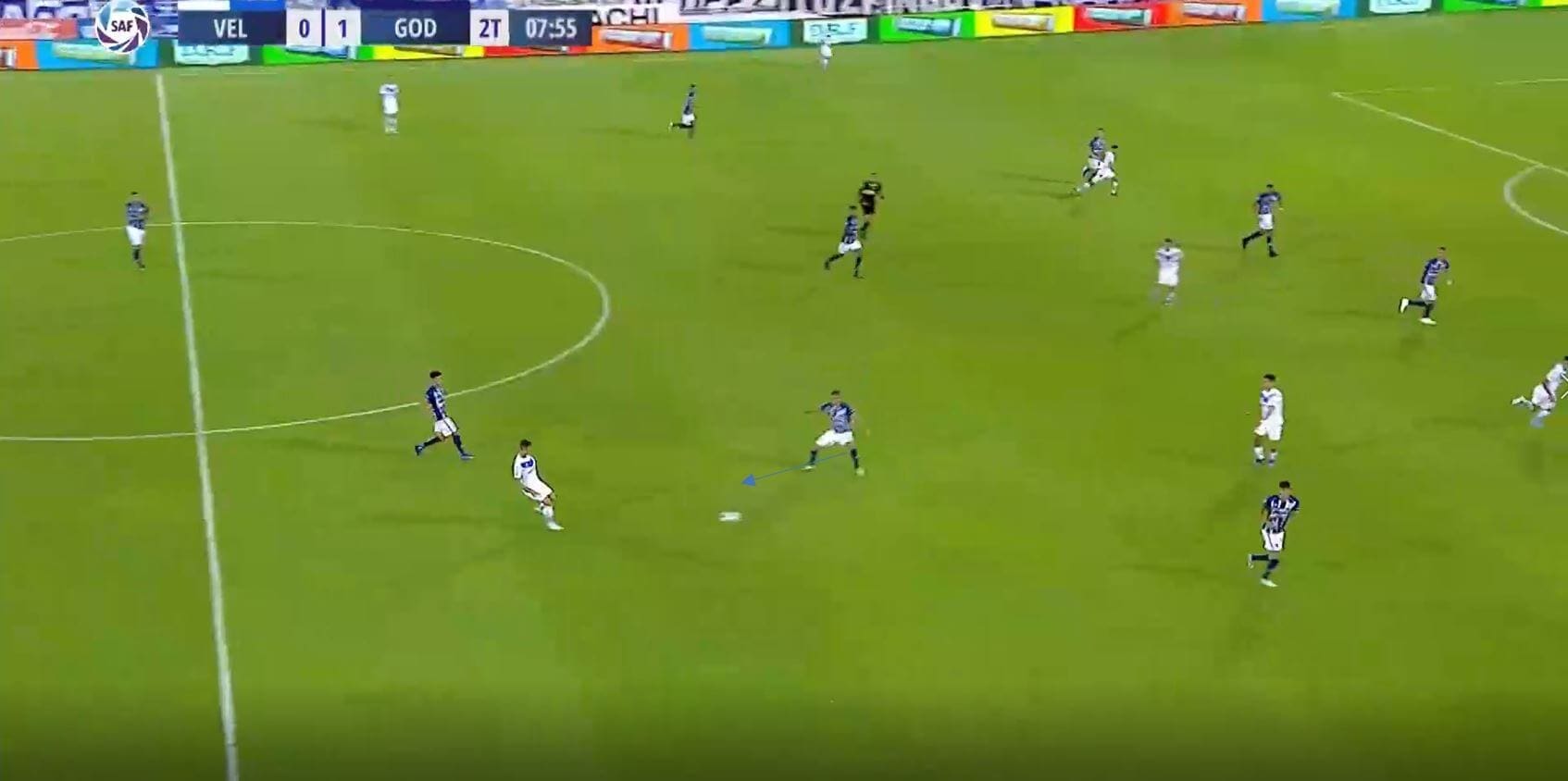

A common scenario in Heinze’s build-up is the ball being worked to the wing-back, where they are then able to be pressed by the opposition winger. Heinze’s side will occasionally deploy a back three with a dropping pivot as we can see below. Under no pressure this is an easy way to break the first line, and they do occasionally use this pivot as a mechanism to switch the play from one wide centre back to the next. However, a constant pivot is much easier to defend against as they always occupy the same space/line. Furthermore, for Vélez it brings a player deeper and therefore not in a higher area.

The solution to this problem is one I have written about extensively on Tim Walter, regarding the movement of centre backs into an empty pivot space. We can see here the wing-back has moved deeper and plays the ball down the line to the winger. The pivot space, or space between the first and second line is unoccupied, and we can notice the positioning of the central midfielders behind their markers, pinning them at this height. A centre back can time their run into this space, and is not tracked or pressable until he has arrived in the space, by which time he has already received the ball.

We can see that the player arrives into the space and receives, and so the pressing distance for the second line is too far. The opposition still press anyway, which then opens up space for the player behind him.

We can see another example here, where Heinze’s side employ one of their basic principles of pass and move, and again space well to allow this to happen. The ball is worked wide to the wing-back, and the nearest central midfielders don’t occupy the half-space, instead allowing a player from deep to arrive into the space, and again gaining access to the second line. By doing this, they allow more players in higher areas, therefore helping them to create overloads.

Using the goalkeeper to stretch the press

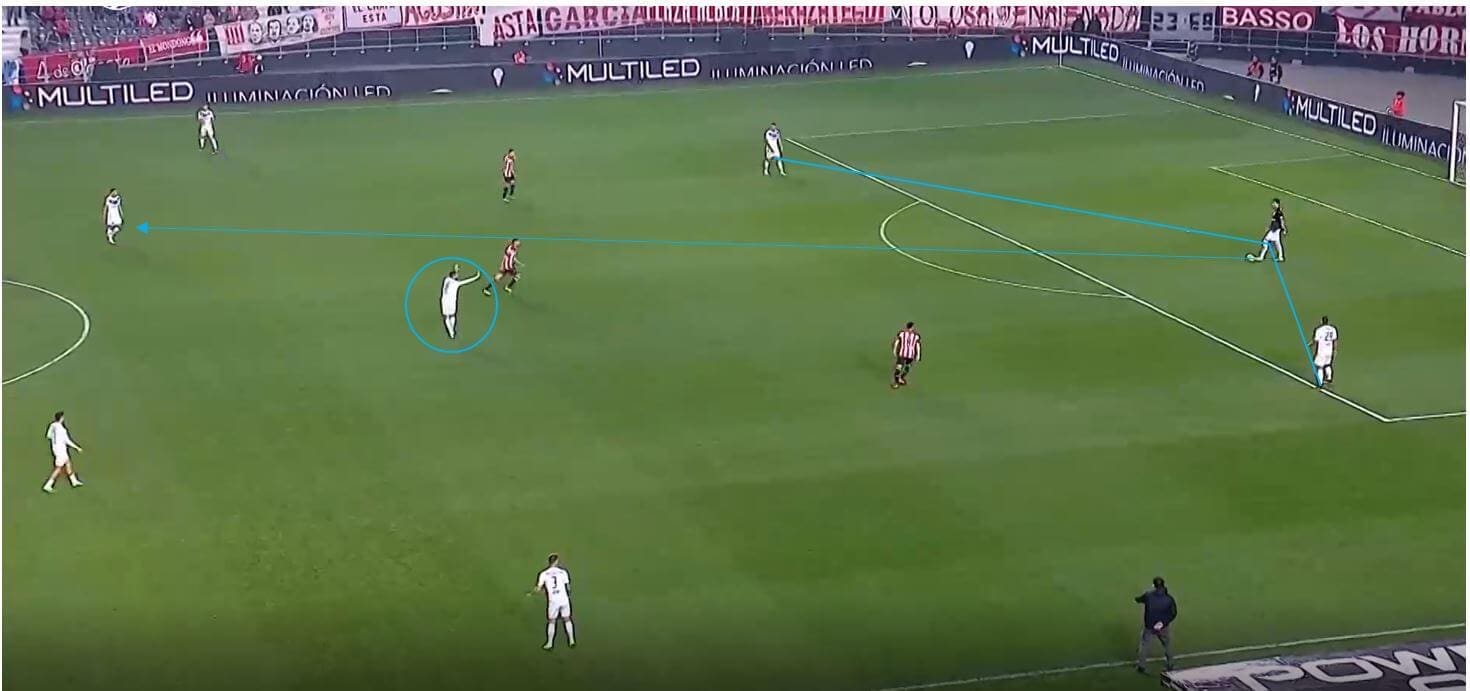

In deeper areas, Vélez can take this idea of building without numerical superiority to the extreme. Where a defensive midfielder usually drops, in deeper areas the goalkeeper can become the central defender in the three, and is happy to dribble out and be patient to trigger the press.

Again it’s important to point out when this strategy might be used, and is something that Heinze himself has discussed and I’ll paraphrase. If they face a one man front press, the goalkeeper is not needed as two defenders can stretch this one press easily. Against presses with two or more players, the goalkeeper is more useful to generate superiority. I agree but would also like to see what happens if they always use the goalkeeper to generate superiority, as you could then almost build with one other centre back initially against a one man press.

We can see the goalkeeper being used here, with the aim to generate superiority against a front three press from Estudiantes. The midfield player clearly instructs the goalkeeper to wait in order to trigger the press from the first line. The wide centre backs open up the central spaces which are occupied, and so a pass is played through into here and the high wing-backs can then be used. As a result, they can build up in a 3-5-3.

We can see here the confidence this takes from the goalkeeper, but if done effectively could lead to large overloads able to be exploited. Vélez do occasionally use this strategy in order to get players higher up the pitch and win second balls.

Offensive structure

In deeper areas, Heinze’s philosophy revolves around these principles:

- Occupation of the half-space

- Extreme width to create space

- Arriving into space

- Pass and move

- Rotate to find space

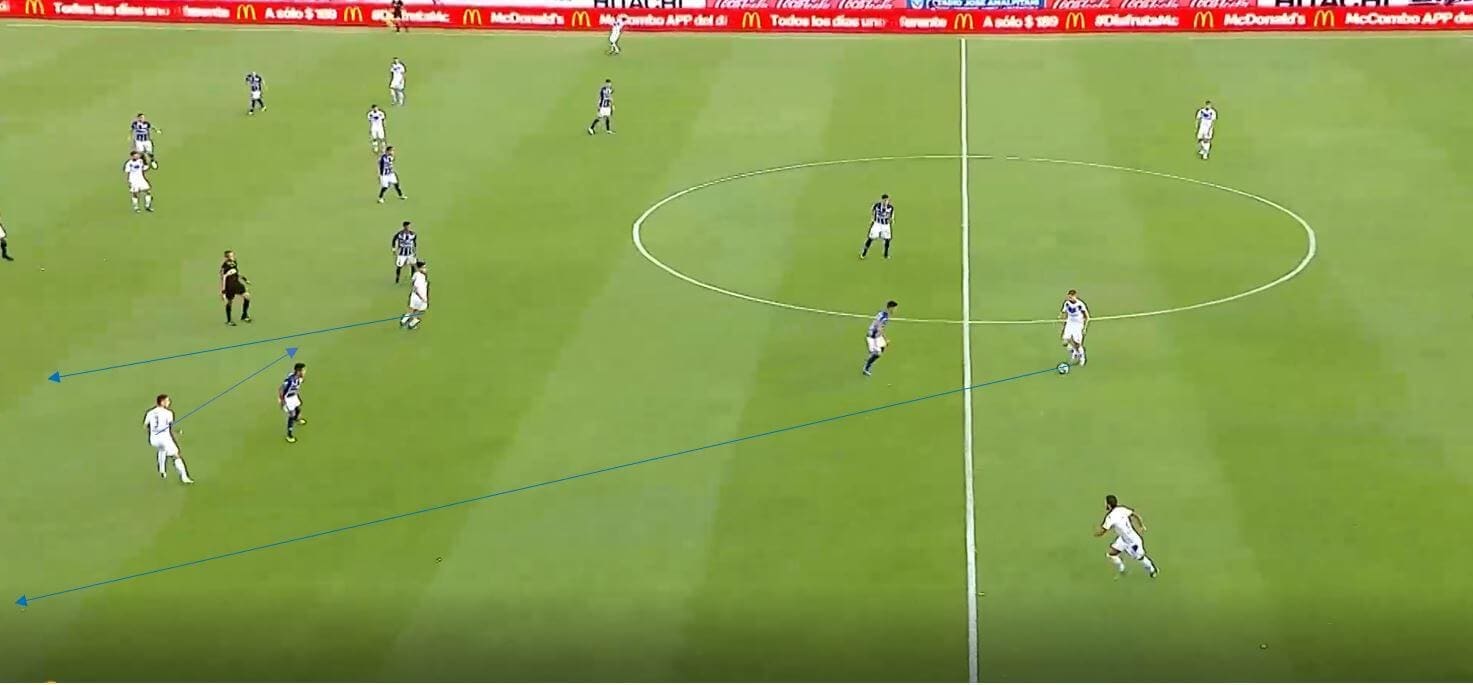

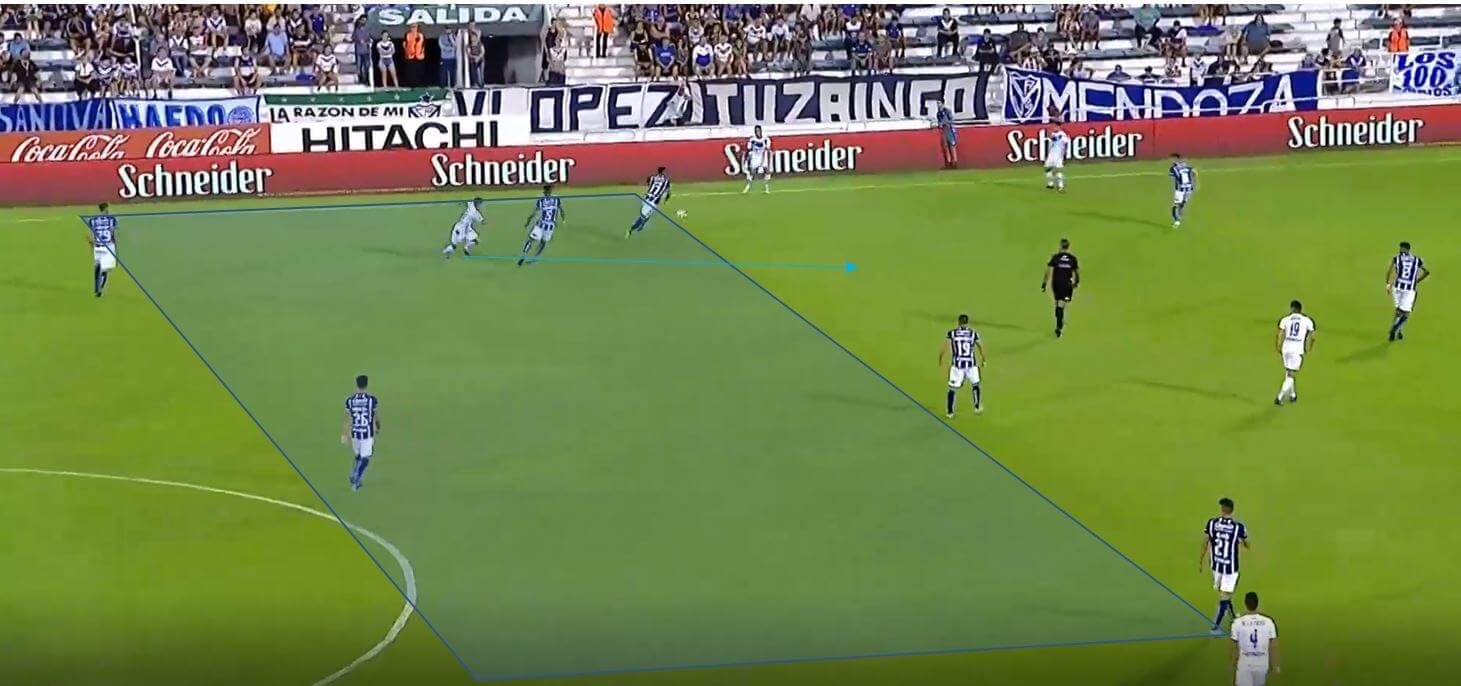

Throughout these examples, we can see each of these principles being put into place. We can see here the extreme width which I mentioned, which here is provided by both the wing-back and the winger in a 3-4-3. Both of the widest players within the second and third lines of the opposition are occupied in wide areas, which creates space in the half-space for central midfielders to move into as seen here. Central occupation by the striker is also key in order to occupy the centre backs.

We can see here that they don’t always rely on the central midfielder to occupy the half space and will sometimes use the winger in this area, and place players around them or use centre backs to find them with passes. We can also see from this that the far wingers remain very wide, in order to create the opportunity for a switch in play, where they can then isolate a full-back one on one and use the dribbling skills of their wingers.

This example here shows the occupation of this area again, and their use of rotations around this area. Here they are able to draw pressure from the second line and open up the half-space, and can also threaten runs down the line. Heinze will often allow players to position themselves high in order to overload the last line, and rely on less players to break through the first line as a result of good movement.

Movements also allow for certain spaces to be created, and Vélez here use decoy movements and rotations to find the wide player off screen. The left winger/wing-back moves narrower, taking his marker with him slightly, which opens up the space for the higher winger.

The central player in the above image rotates to try and occupy the half-space, but the winger is unable to flick the ball round with a first time pass. As a result of this rotation, the space ahead of the ball is unoccupied, which doesn’t allow Vélez to counter-press effectively.

We can see a similarly good but this time more effective rotation, where a central midfielder rotates into the wide area while the winger comes into the centre. This disorganises the man orientated structure of the opponent, and creates space on the wing to receive.

The principle of pass and move applies further up the pitch too in order to break lines.

Man orientated pressing

Vélez have pressed in a variety of shapes and due to the way in which they press, the shape is ever changing. The most common shapes seen have been a 3-4-3 or a 4-1-4-1 structure, but again they change constantly, due to space orientated man coverage. By this, we mean a mix between solely man orientated pressing and zonal pressing, where each player occupies an area and presses relative to an opponent’s proximity to this space. It is not strict man marking, as player’s don’t remain tight all the time to the same player.

We can see here an example of this, where players are pressed by the player in the zone once they receive the ball. The centre back plays the ball to a central midfielder and they are pressed from behind. Once the ball is played back to the centre back, it becomes the responsibility of the striker.

They keep a basic structure of their 3-4-3/4-3-3, but depending on the height of the press the shape changes. Here when the centre back plays it laterally, the central midfielder jumps to press this player, as they appear in their vertical zone. Heinze’s side often look to press high, with an average PPDA of 7.19, however this number is often boosted by their possession heavy games. Once they take the lead, Vélez are happy to sit deeper, still sticking to the same coverage.

One of the major disadvantages to this is if players press too early or intelligent decoy movements are made, space can be created in dangerous areas. We can see here the centre back moves out to press the player occupying his zone in front, and the ball is not played to him, and is instead played into the space created in behind. This has been a big problem for Heinze’s side in terms of conceding goals, and I would suggest if he moves to Europe that this coverage system would be exploited if not adjusted or scrapped. Vélez do a poor job of occupying these holes once they are made, and better quality sides would exploit this.

Transitions

Heinze doesn’t seem to focus too much on defensive transitions, and the climate in Argentina doesn’t seem to allow for constant counter-pressing throughout the game. As I mentioned earlier, the offensive structure of Vélez does not lend itself to counter-pressing too much. With midfielders looking to stay behind the second line and create overloads, if the ball is lost, little vertical counter-pressing occurs and counter attacks can harm them. Their insistence on width also reduces their ability to cover the centre during counter-pressing moments.

We can see a pass and move example here, in which when they do pass and break a line, there is no longer cover behind the ball, therefore if the ball is lost, vertical counter-pressing is difficult. There is a general idea behind this kind of movement that they are moving in the same direction as the pass, and so are already in a position to vertically counter-press, but if the runner receives the ball, there is little cover other than the back three on the halfway line.

In offensive transition, Heinze allows his players to remain fairly high at times, with the front three often remaining in more advanced areas. From there his players have the quality in transition to exploit teams, and often use up, back, through combinations in order to advance. We can see here that combination occurring, with the speed of Vélez’s players allowing them to exploit space in behind well.

Conclusion

Gabriel Heinze is a manager I expect we will see in Europe soon, as a result mainly of his side’s offensive system, which is probably why this analysis on Heinze’s philosophy has been so offensive. The former Man United and Real Madrid player has instilled a brave, fluid, creative style of football that uses concepts and principles from coaches, from Tim Walter to Marcelo Bielsa, and instilled it quickly into a young, lesser quality squad than others in the Superliga. The defensive system is not ideal and may be something he looks to change, but for me the most interesting aspect of any move to Europe will be how he implements counter-pressing into his philosophy, as in South America this seems a much less used tactic.

Comments