Back in 2013 Beerschot were declared liquidated after financial debts. Consequently, the club was sent down to ‘eerste provinciale’, the fifth tier of Belgian football. Just seven years later Beerschot were promoted back to the first division of Belgian football. The way to the second division was fairly easy as they promoted every season from fifth to second. But the final hurdle to first seemed to be a difficult one. After two failed attempts and a rather tough start to the third campaign, Hernan Losada took over as manager. This turned out to be a successful decision as Beerschot promoted to the first division.

Not only did Losada achieve promotion with Beerschot but the way he did it was impressive. The young head coach was inspired by former Ligue 1 and current Premier League manager Marcelo Bielsa. The ideas of Bielsa, with Loasada’s own turn to it, can be seen back into Beerschot’s playing style. This and the good results are the reasons why Losada’s is seen by many as the next big thing in Belgian football.

In this tactical analysis, we will look at the tactics which have given so much joy this season. Aswell shall this analysis provide insight into Beerschot’s weak points.

Common field occupation

In possession

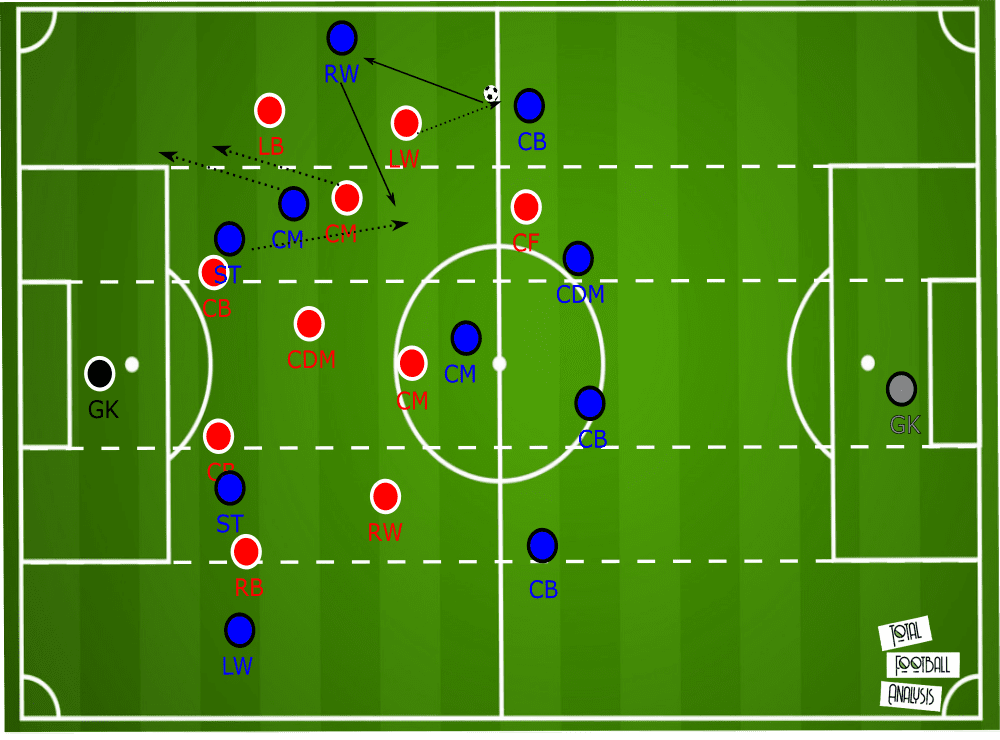

Losada prefers to line his team up in a 3-5-2 formation when in possession. The back three gives Beerschot during the build-up phase more advantages in order to progress the ball through the thirds. Firstly the priority is to build from the back in a numerical superiority hence the extra centre-back. But also when building with three centre-backs, Beerschot attract pressure from the opponents’ second line press when the outside centre-backs in the back three take up higher and staggered positions relative to the central centre-back. Consequently, the connection between the outside centre-backs and wing-backs are more optimal. And lastly, because the back three occupies the width of the field, vertical passes are available to play especially down the half-spaces.

Another advantage Losada uses the system for is the fact that two strikers occupy the opponent’s last line. Especially playing against teams using a four-man defence, Beerschot can control them with just two strikers by positioning the strikers between the centre-back and full-back. When the ball is played in between the opponent’s lines it creates a decisional problem for the defenders. They now have to make the choice to press the ball and leave space in behind or stay in position and let the player receiving the ball between the lines in space. Thus in numerical inferiority, they can control the opponent’s last line.

Another intriguing feature is Beerschot’s five-man midfield with their central midfielders occupying the centre and half-spaces. Whilst the wing-backs position themselves close to the touchline. Because they only have three men centrally in possession, Beerschot often find themselves in numerical equality or even inferiority. Which means playing through the centre becomes more difficult. But through dropping movements of the strikers and outside to inside passing sequences through the wing-backs stretching the opponent’s midfield line, spaces eventually open up for Beershot to play through. More about that later on.

Space occupation and dynamics

As discussed above, the Kielse Ratten operate in a 3-5-2 system as a reference point. In order to respect the rules of Juego de Posición which are used by Manchester City manager Pep Guardiola, through movements of the players, this system is often not recognizable.

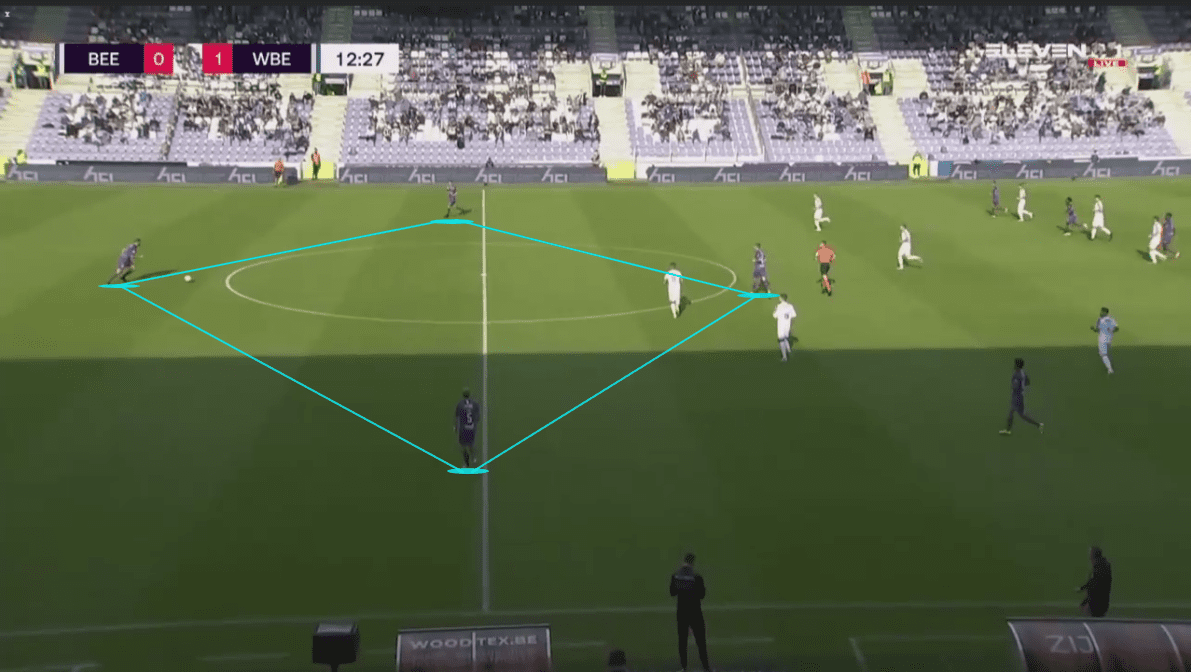

Positional Play/ Juego de Posición is a philosophy that has many principles but one of the fundamental principles is the search for superiority. There are various ways to gain superiority and various types of superiority that can be achieved. Once superiority is found the team can use the situation to dominate the game. In order to create superiority in the simplest form, Losada asks his goalkeeper to play in possession high and outside of his own box to attract an attacker to press and thus create space. Consequently the right centre-back and the central centre-back in the back three split and move wide. This creates a diamond shape with the goalkeeper, centre-backs and pivot which allows clean progress to the middle third. If allowed more space to build until the middle third without pressure the diamond shape still applies in a 3+1 structure. Optimal staggering and distances are crucial in order to manipulate the opponent’s defensive structure.

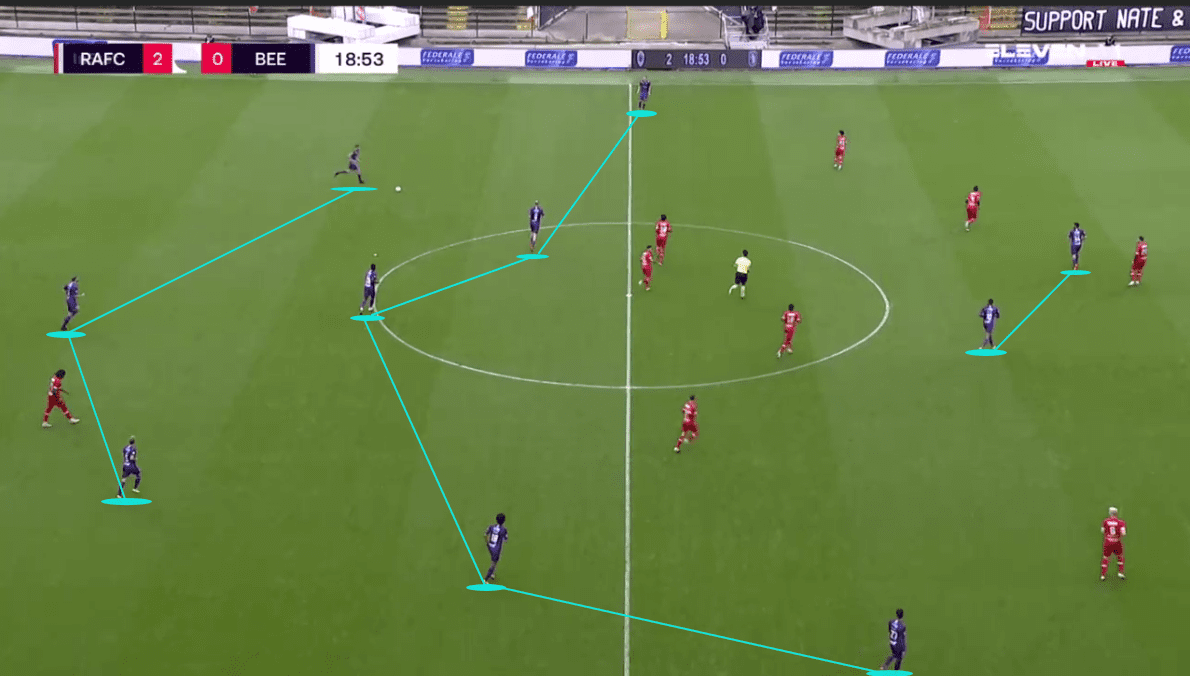

After progressing the ball through the middle the ball is often played out wide. Because of the outside dynamic movements, Beerschot’s play is orientated to the flanks. They try to create wide overloads due to the left-centre-back moving forward when the other centre-backs split. The left-wingback therefor moves inside to create optimal diagonal staggerings. The striker also moves to the side in order to create an overload on the flank. The below image shows us these common movements.

The below image gives us a more detailed and clearer idea of the wide rotations. Note that the structure of the diamond stays intact but the players in each position can vary meaning that for example, the wide centre-back can push up into advanced areas beyond the last line in the half-space.

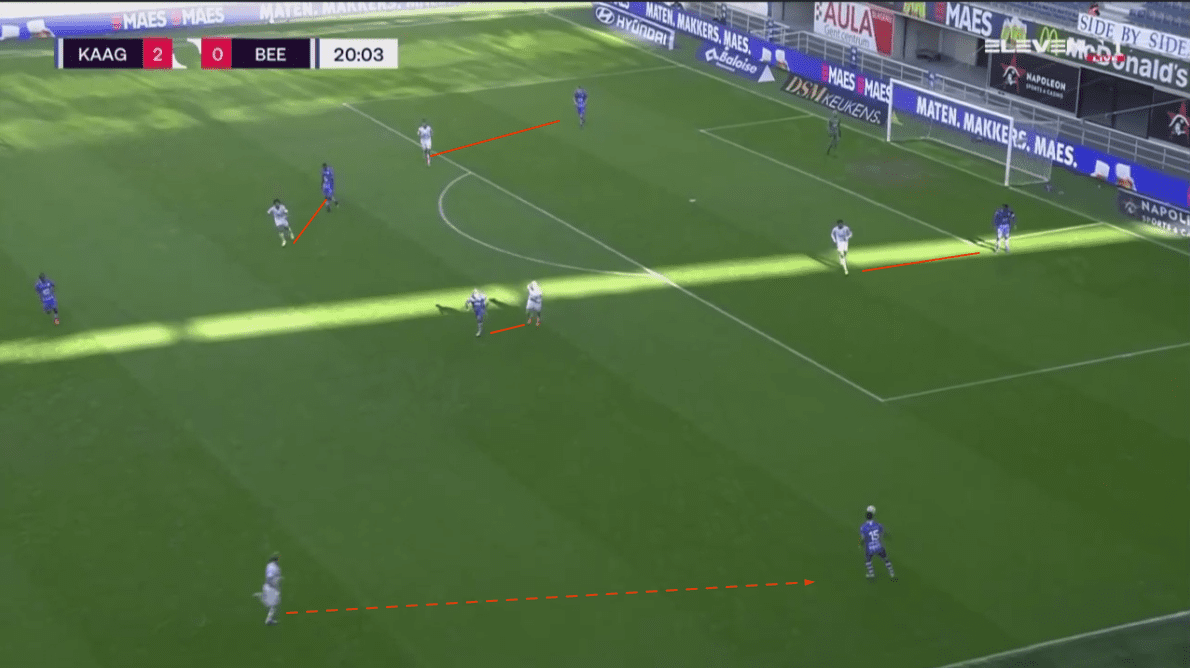

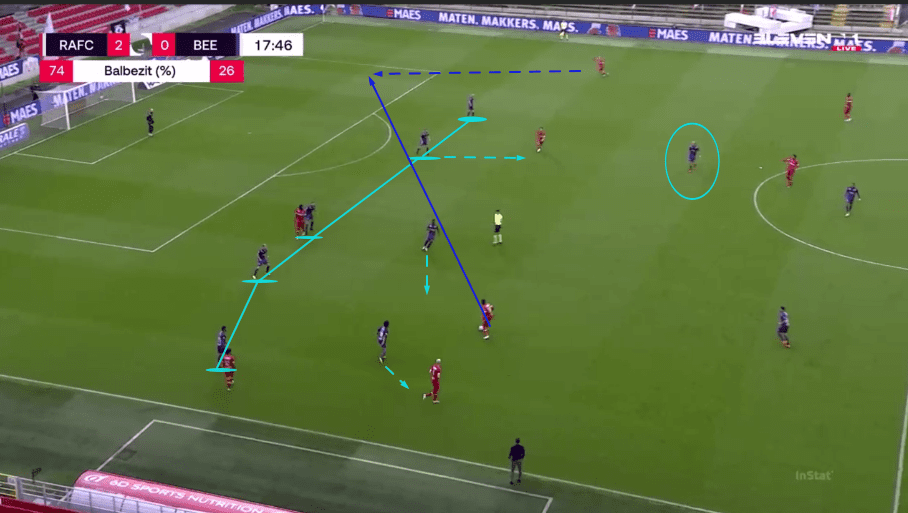

The above image also illustrates the inside to outside passing sequences Beerschot use to find players in the advanced areas of the pitch. Especially against a five-man backline, the direct pass out wide is less accessible, therefore the inside penetration to move the ball out wide occurs in a higher emphasis. By creating the central-overload, it causes orientation issues for the first and second line, which opens the access towards the centre, from where an outside pass can be player reached.

On the other hand against a back four outside to inside dynamics are more effective to use. The oppositions midfield is more packed which allows passes to the outside to be more accessible. A direct pass out to either wide player from the back gives the outside receiving player the option to play inside due to vertical opposite movements of the midfielder and the striker. Since the attacking midfielder in the half-space is covered by the oppositional and the striker by the oppositional centre-back, there is no real ‘free’ man but when the movements are done at high speed, space opens up when for the striker to receive when the striker drops and the attacking midfielder penetrates the full-back/centre-back channel. This also exploits a simple defensive principle: when the ball goes out wide, the 2nd line usually drops deeper to offer cover, which will generally open space to the centre. Due to the oppositional centre-midfielder being pulled out, distances increase in the opponents’ second line. Which again allows more space for the striker to receive a pass from the outside player. The below image clarifies this.

The key role of the pivot

As discussed earlier, Beerschot build in a 3+1 structure. This gives the pivot a huge responsibility to find players between the lines and beyond. Especially because he is on his own in front of the three defenders. The pivot has to create an angle here to receive, and also has to time the movement so he can receive without allowing the opposition to anticipate and press him. If he does this, it creates multiple decisional problems for the opposition as each player in the second line has to shuffle to protect the spaces between themselves, which then opens up wider spaces. The central positioning of the pivot also allows him a greater range of passing. But being available to dictate play from deep due to the opponents pressing systems isn’t always a given.

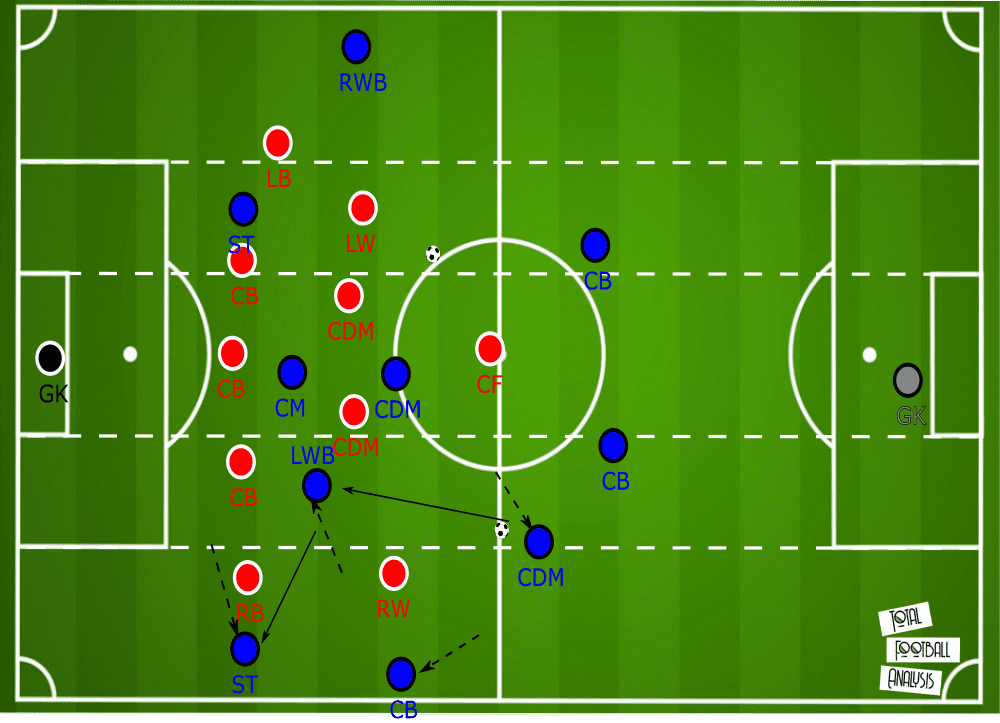

The example below shows this. Ryan Sanussi, the deep midfielder is marked closely. Consequently, he cannot receive the ball from the back three. The solution lies in a bounce pass. A dropping striker comes to receive the ball with someone following him. By playing a one-touch pass into the pivot, the pivot can now receive with his face to the opponent’s goal. Another variant/passing sequence through the movement of the striker could be that the pivot penetrates in the space the dropping striker left due to the opponents centre-back following him. The striker then lays off to a deeper-lying player, who then plays beyond the last line to the running pivot. This is also known as up-back-through. Recognizing game situations is key for the pivot in Losada’s system.

Here another example, Tom Pietermaat was marked by the opponent’s number 10. In this case, Sanussi drops next to the centre-backs to create a back three. As a result, the number 10 steps out to press Sanussi, because it was his job to mark the most deep-lying midfielder. At the same time, he tries to cover shadow the initial pivot in Pietermaat. Here Pietermaat has to be smart and step out of his shadow cover but stays in it, thus progressing the ball forward isn’t possible.

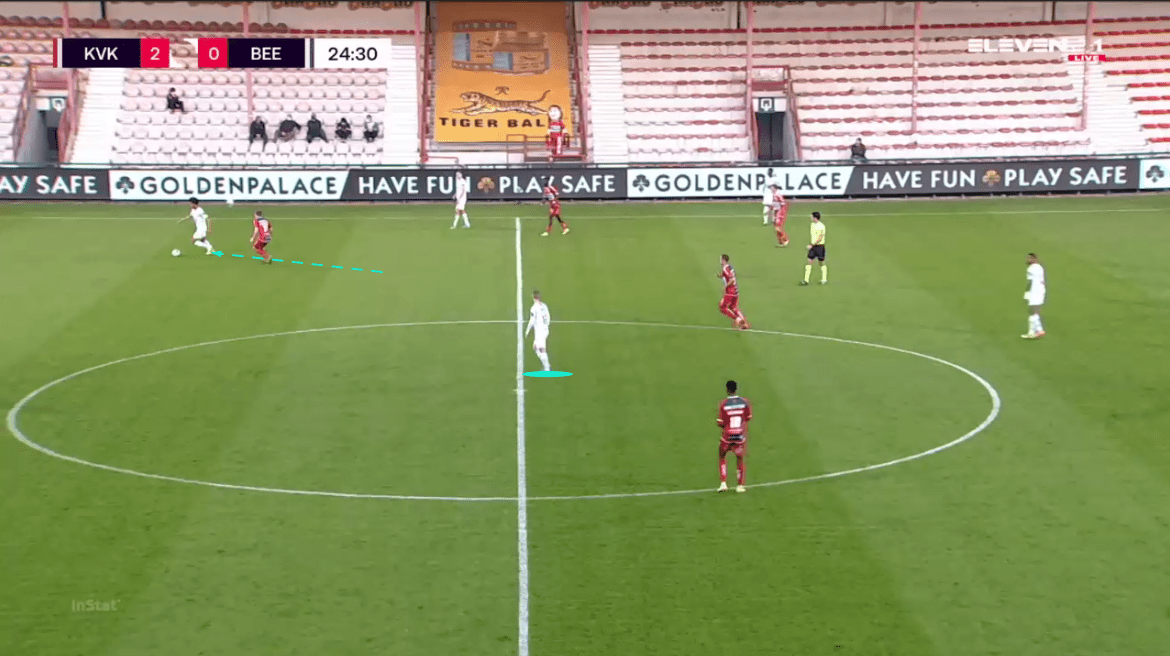

As discussed above, movement is important to counter-pressing opponents closing off passing options. Below nobody is cutting off the passing lane nor marking Beerschot’s pivot. Thus he receives in between the opponents first line of press, opening up vertical passing lanes. This can be effective due to the lack of pressure on the pivot and not being marked of course. But ideally, the pivot would need to receive and position himself behind the first line to manipulate the second line and create space for advanced attacking players between the lines.

Especially below against Waasland Beveren, Beveren operated this game in 5-3-2 system. By placing the pivot behind the first line, at least one player of Beveren’s second line would step out and create huge imbalances in defensive distances between Beveren’s second line.

In this example below the pivot, Dario Van den Buijs does try to manipulate the opponent’s second line by running towards the second line, dropping off and asking for the ball. What follows is a midfielder being dragged out of their defensive shape. And consequently opening up space for Beerschot’s players between the lines. Concluding that simple movements are crucial for the pivot role in order to manipulate the opponents’ structure and progress play.

Out of possession

At the moment of writing this article, Beerschot scored 33 goals thus far this season. Just that stat alone indicates Loasada’s team is a threat in attacking areas, as this is the highest goal tally in the whole Belgian league. But on the other hand, Their goal conceding statistic isn’t that impressive at all. They conceded 30 goals after 12 games. Which is only one less than relegation placed Waasland Beveren. Out of possession Beerschot utilize the same system but with the exception that the wing-backs drop next to the centre-backs forming a back five without the ball. The system focusses primarily on keeping a compact low block. Distances between players are closed to the minimal, looking to close the centre and pushing the opponent to the sideline. The back five and the two defensive-minded midfielders play a huge part in nullifying any danger from the opponent. With Holszhauzer and the two strikers pressing rather passively especially in low block. This cost them a couple of goals this season but in transitional moments from attack to defensive, they are even more vulnerable. We will discuss these aspects out possession in further detail below.

High pressing

Losada prefers to win the ball back as quickly as possible once they lose it. It comes at no surprise that Beerschot’s PPDA is 9.61 and sits in the fifth position in the PPDA rankings of the Belgian first division A. This indicates, of course, their willingness to win the ball back once they lose it. Thus they try to press the opponent high up the pitch when they are building from the back.

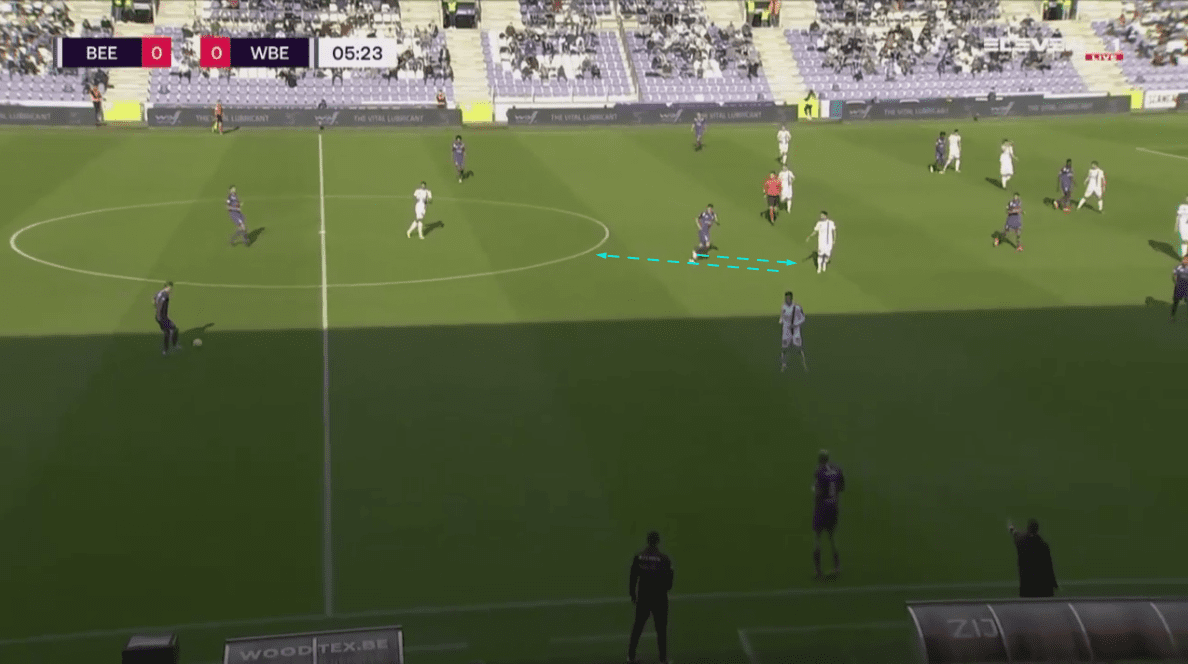

Above the opponent attempt to build from the back while Beerschot try to prevent that. The two strikers Tarik Tissoudali and Marius Noubissi would prevent the opposing centre-backs any time nor space when they build from the back. Raphael Holzhauser would mark the pivot. So the first line of press choose to operate close to the opponent’s goal but the second and third line do not keep the distances between the lines minimal. This to prevent defending with huge spaces in behind the last line. Thus the way to manipulate this pressing system is to play the difficult chipped pass behind the first line of press. Because of the difficulty of this pass, Losada is happy to leave this space unoccupied.

Thus in the above image, the opponent chose to position their full-backs high, which makes it eventually less difficult for Beerschot to run down the opponent when pressing high. Below against Gent, the full-backs of Gent take up a deeper position. Distances increase for the Beerschot’s wing-back to close down a receiving full-back. Which eventually makes it less difficult for Gent to play out from the back. A simple curved run from the ball near striker to cover shadow the pass to the full-back would eliminate Gent’s ease to progress the ball to the middle third and beyond.

The retreated press

One thing is defending high with room for error, another is staying low in a compact block closer to the own goal. When pressing high a mistake can easily be rectified due to the large distance the opponent has to run to reach the opposing goal. But when defending low, a mistake can easily lead to a dangerous chance or even a goal. Thus a player refusing to properly press can lead to danger.

In Beerschot’s case, this is former Bundesliga midfielder Holzhauser. A menace going forward but rather invisible going backwards. Comparing the data to the league as a whole, we see how well Holzhauser ranks in terms of goals and assists throughout the league by topping both of them with nine goals and six assists. Defensively Beerschot struggle and with Holzhauser being one of the three central midfielders, pressing passively does impact their defensive shape and second-line press.

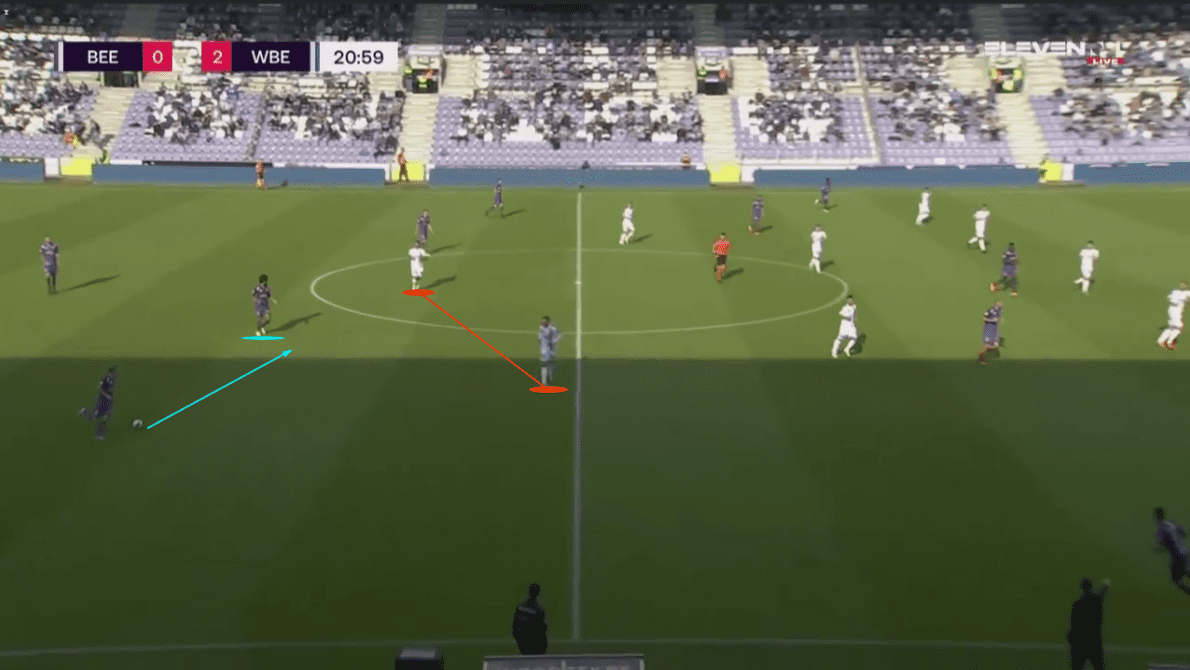

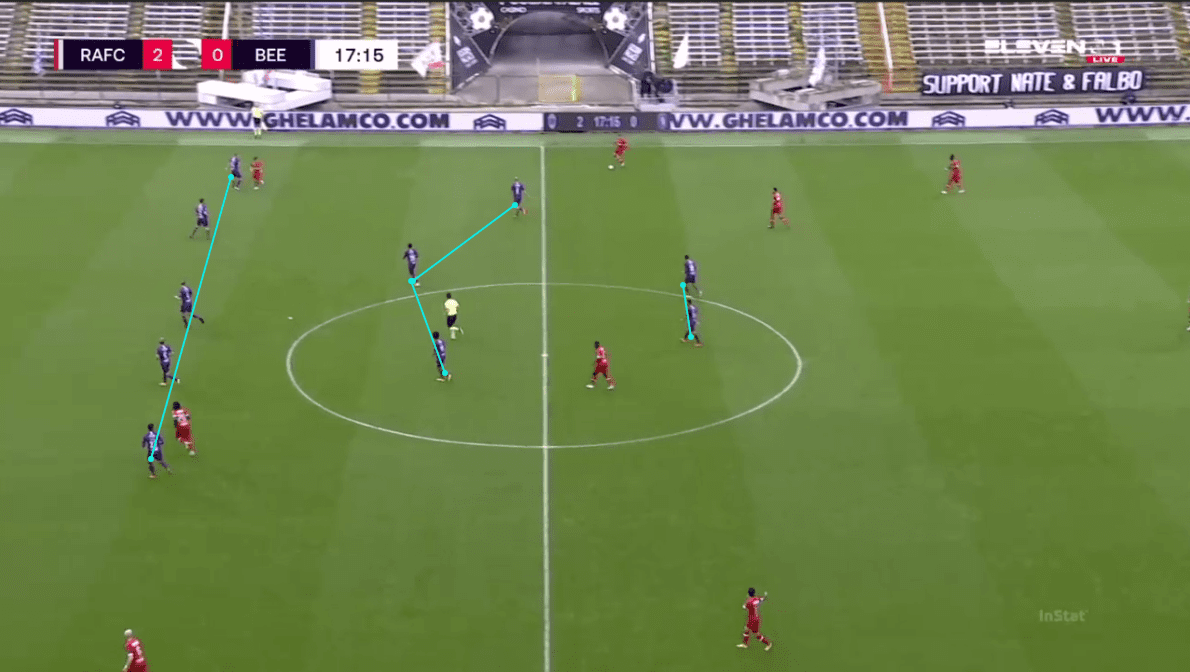

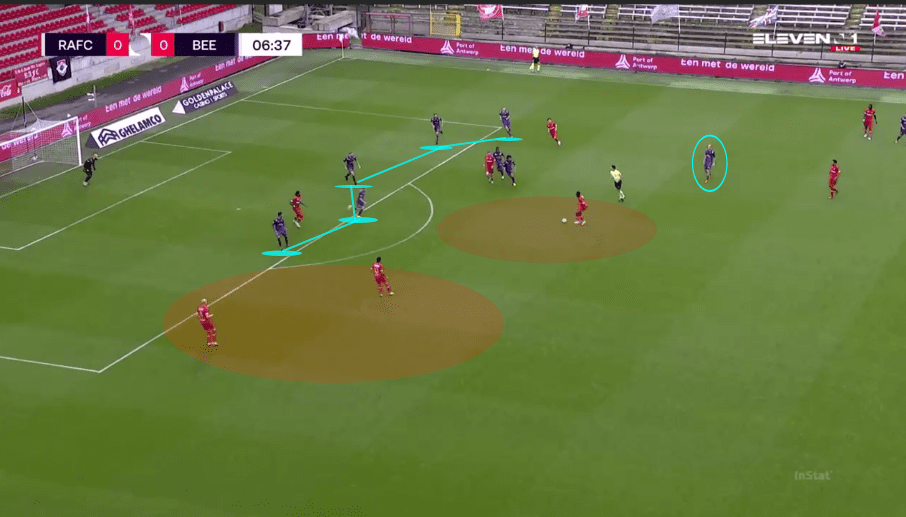

In the below image we can see Beerschot pressing to the sideline in a low defensive block. The last line shift to the ball side and each Beerschot defender picks up a player to cut off all options for the ball carrier. Due to Holzhauser not participating in the low press the Beerschot second line exists of only two players and the ball far Royal Antwerp midfielder finds a free pocket of space. As a result, the left centre-back is caught in two minds. He opts to step out and intercept a possible pass to the ball far Antwerp midfielder but instead the ball is played in behind the left centre-back into the running right wing-back. If Holzhauser would drop a bit deeper, the width of the pitch can be covered effectively in the second line areas.

Another example below shows how the second line struggle with players in front of the last line of defence. Note that the Antwerp players do not need to do any effort to receive nor position their bodies correctly between the lines due to the second line being underloaded. In this case, Lior Refaelov receives in front of the last line to score from outside the box.

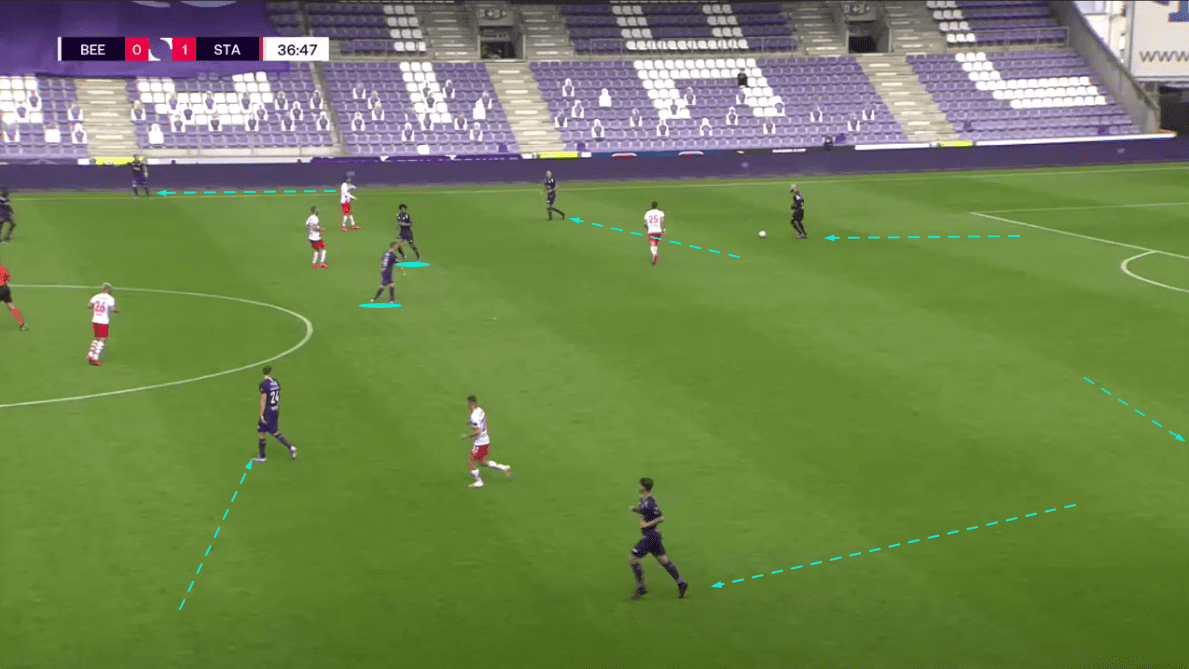

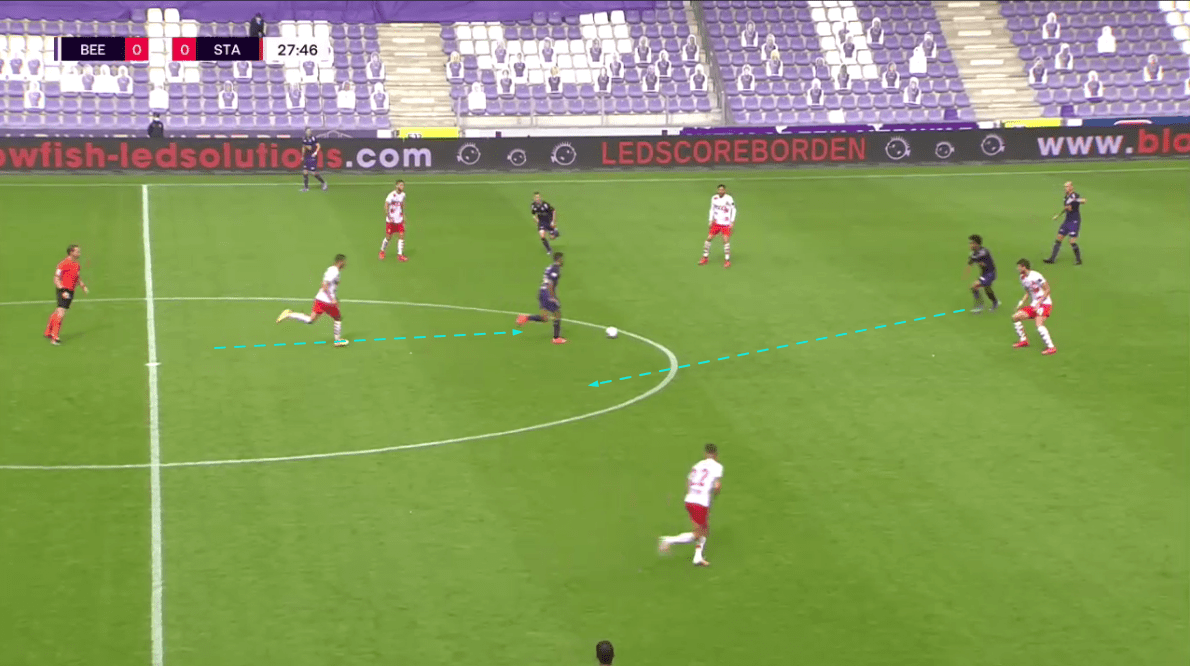

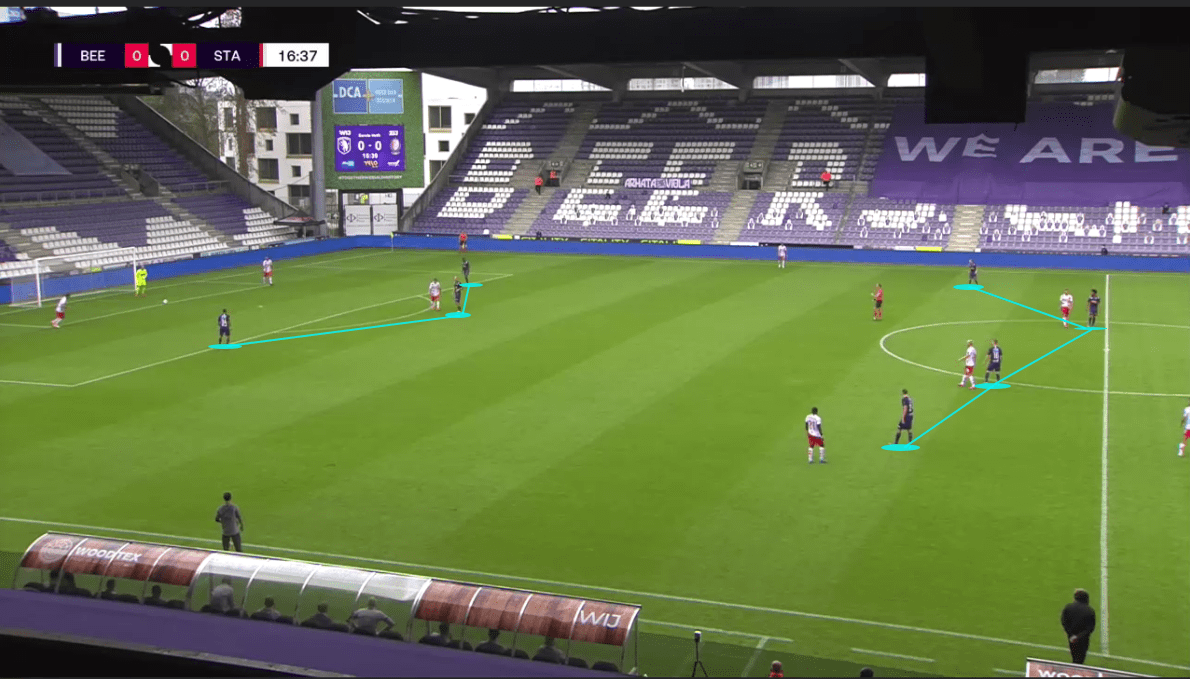

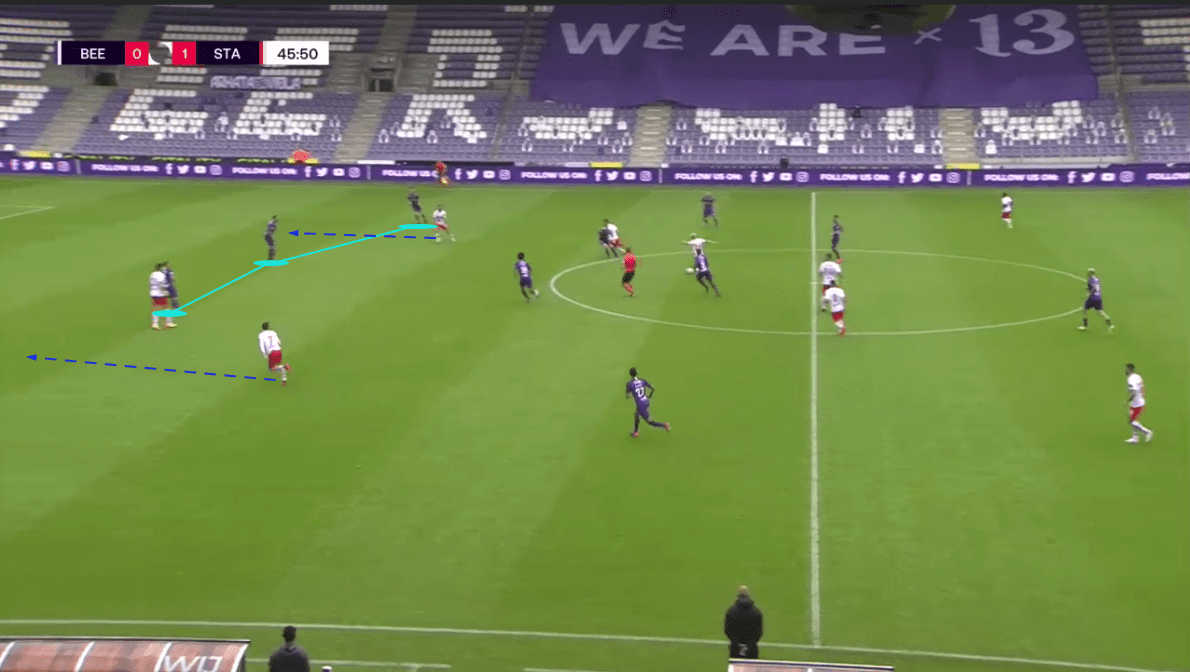

Lastly, Beerschot are also vulnerable in transitional moments van attack to defence. As mentioned in the attacking section, the wide centre-back moves to the side to overload the flank, whilst the other centre-backs split rather wide to the half-spaces. This gives a lot of options in order to progress the ball forward. But once they lose the ball centrally the distances between the centre-backs become very big. Counter-pressing effectively is also difficult due to these large distances. Opponents can easily penetrate the centre-back to centre-back channel and the centre-back to full-back channel. In the image below Losada’s men lose the ball centrally, Pierre Bourdin tries to close the centre by moving inside after his attempt to overload the flank. The distance is too big to do this in time. Thus Standard Liege can exploit the outside channels and take advantage of these spaces.

Conclusion

After promoting last season and taking this season by storm with Beerschot, Losada has already shown to be a promising coach. It is a pleasure to watch Beerschot this season as they scored the most goals this season thus far in the domestic league, showing their attacking intent. On the other hand, their defensive shape has to improve, as they conceded the most goals if they want to be contenders for European football or even the domestic title.

To conclude this analysis we can say that the sky is the limit for Losada. As he has shown to be the next managerial prospect, only Losada himself is able to estimate how far he can go. Why not apply pressure…

Comments