SV Elversberg fans are living the dream. The small club is located in the municipality of Spiesen-Elversberg, with a population of just around 15,000. They have never been a traditional club in Germany, and in fact, only have two appearances in 3. Liga, Germany’s third division. However, this second appearance is proving to be a historic one.

After a fantastic 2021/2022 campaign in the Regionalliga Südwest, the German club secured promotion to the third division for the second time in its history. Given they were immediately relegated in their last 3. Liga appearance, survival would have probably been an ideal scenario for Horst Steffen’s men.

But 24 matches into the season, Elversberg are sitting at the top of the league, six points clear of Freiburg II at the time of writing. Steffen’s side comfortably has the best attack and the best defence in the league. This balance has been fundamental to their success, and a lot of credit must be given to the 54-year-old manager.

The tactics at the Waldstadion an der Kaiserlinde have principles and ideas that transcend phases of the game, an idea recently popularised by EFL Championship manager Carlos Corberán. There is a traditional German identity in their playing style, with a few very interesting tweaks, especially in possession. With such an intentional approach, Steffen has guided Elversberg to unimaginable heights and the chance of a historic promotion to the 2. Bundesliga.

This tactical analysis will take a deep dive into Horst Steffen’s tactics at Elversberg, looking to identify how the German manager is making history with the small club from Spiesen-Elversberg. Going beyond what they do in each phase of the game, this analysis aims to break down the key principles and ideas that guide their tactics.

Structural tendencies

Steffen has consistently deployed a traditional 4-4-2 throughout the 2022/23 season. There have been occasional variations, of course, depending on the situation in the game, opposition, availability, and other numerous factors. However, these serve more to highlight the flexibility of their structure than an intention to constantly adapt to the situation. In fact, the flexibility, or perhaps fluidity of Steffen’s 4-4-2 is its trademark feature.

Beginning from the first phase of possession, Elversberg initially structure themselves in an expansive 4-4-2. The centre-backs split the box while the fullbacks push wide and high. The double-pivot remains rather close and compact. So far, nothing out of the ordinary.

However, in this first instance, we can see a slight indication of their fluid nature. The right midfielder, usually number 7 Manuel Feil, is highlighted dropping inside as more of an advanced midfielder. His natural position is actually as an attacking midfielder, despite being wide on the right in their 4-4-2. So what is his role in Steffen’s system?

Perhaps looking at a player’s role through the lens of traditional positions and their corresponding spaces is not the best way to go about it. In the image below, as Elversberg attack on the left wing, Feil, the right midfielder, moves all the way across to provide support. This movement, which is a consistent pattern in their behaviour, naturally loses common structural features such as balance, maximum width, and symmetry.

On the contrary, Steffen’s structure relies on constant approximation with players roaming in and out of spaces nearby the ball. However, they don’t have a traditional short-passing style, which would normally be associated with such a structure. Although they can progress by finding these more immediate passing lines, these movements tend to manipulate space and create more vertical passing lanes.

The centre-forward duo plays a key role in this, supporting and providing depth. If one drops deeper, which tends often tends to be the 198 cm tall Nick Woltemade, the other tends to stay high.

In this other instance, we can see a specific example of players roaming to find passing lanes. There is no predetermined or systematic method for the players to find spaces and connect, it is more natural. The left midfielder, number 8 Jannik Rochelt, is further inside while the centre-forward is wider. While this is minimal, it highlights the constant fluidity in the players’ movements.

While the previous instances provide a more developed example, the one below highlights the initial structure more clearly. We can see numerous pairings, with the centre-backs in the first line, the double pivot in the second, the two wide players out wide, and the two centre-forwards up top. The initial 4-4-2 is clear, but the proximity of the players begins to highlight some structural tendencies.

As the play develops, the structure often becomes minimal, with much proximity between players. As highlighted by the arrows, both wide midfielders have a tendency to shift into the central lanes. With the double pivot and the two centre-forwards, this creates a much tighter and minimal structure. This is not to highlight an ideal structure, but to highlight some structural tendencies instead.

Finally, this last instance provides an additional illustration of some of the tendencies in Steffen’s tactics. Elversberg have nearly eight players concentrated in the wide area, with the ball as a reference. The left midfielder has shifted inside, and the right midfielder is all the way over and up in a centre-forward position. Again, the double pivot and the centre-forwards provide collective support.

Identified through numerous examples, it is clear Steffen’s 4-4-2 has some consistent tendencies. There is significant approximation through minimal structures, players are constantly working in near proximity. In these minimal structures, the occupations and roaming of space become natural and interpretive, and traditional positions lose meaning.

This system has some natural consequences. First, the proximity of players incentivises more spontaneous interactions. Consequently, the number of possibilities that can develop significantly increase, and the outcome becomes more random and unpredictable.

Additionally, Steffen’s side still has a traditional German verticality. The possibility of such verticality is mostly enabled as a result of their structure and its many effects. In the example below, one of the central midfielders finds a vertical pass to the centre-forward, who immediately links with the left midfielder making an inverted run.

Before exploring this verticality more in-depth, we can look at a final aspect of their structure. Steffen’s tactics have a very effective rest defence system, where Elversberg apply immediate pressure after losing the ball. By having such a minimal structure, their counter-press naturally becomes much easier.

This can help us highlight the holistic approach of Steffen’s tactics. Obviously, it is possible to break down their tactics by each phase and subphase. However, there are constant themes throughout all of these. The principles are consistent, the ideas flow from one phase into another.

Verticality

After identifying the key aspects of their structure in possession, we can observe a trademark verticality in their actions. In this sense, verticality is not simply direct passes, but a constant theme in their collective behaviour. Some examples include attacking the depth without the ball, carrying the ball into space, accelerating play, and obviously, more direct passes.

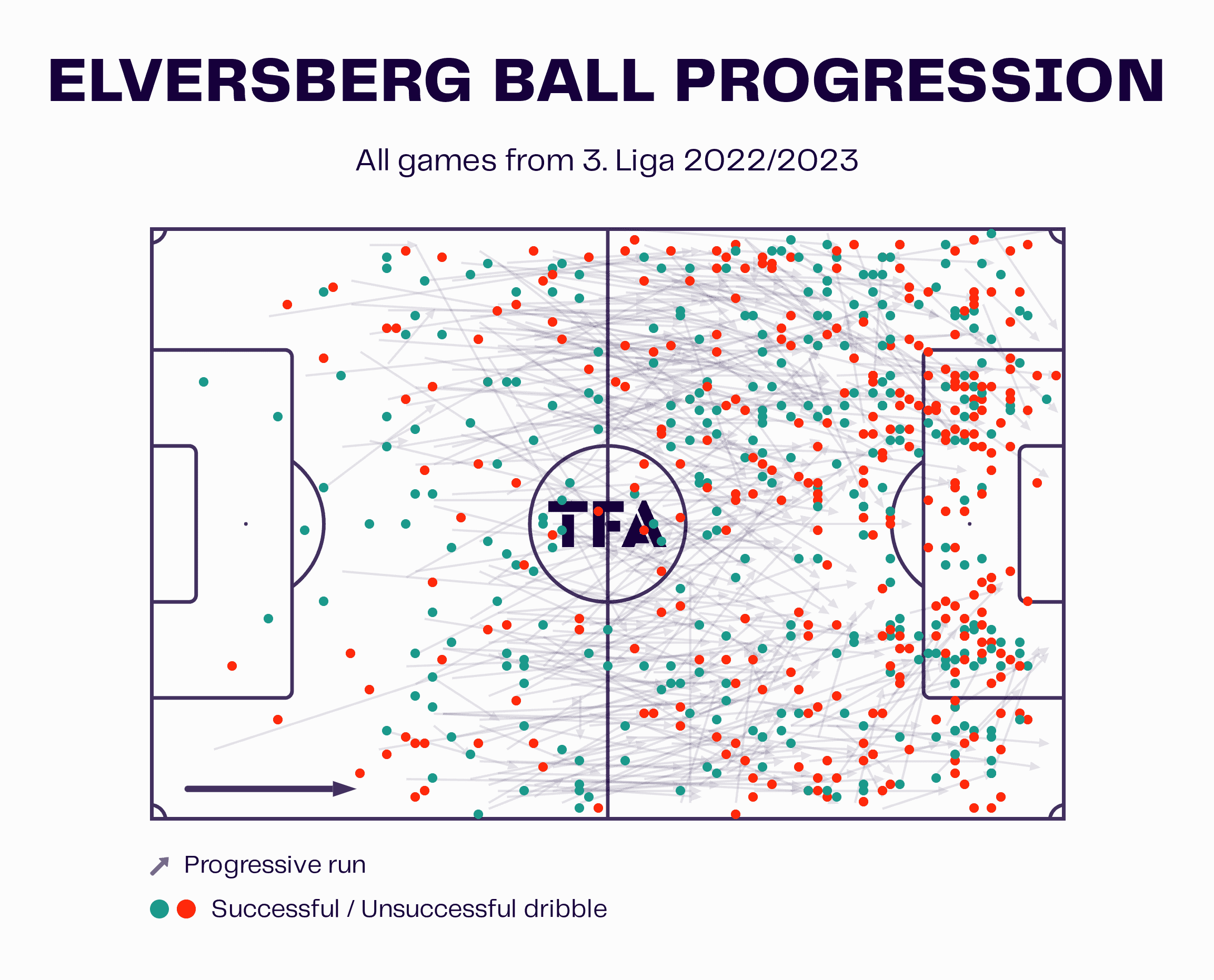

First, their ball progression map this season illustrates this. The dots highlight dribbles, which are abundantly spread across the pitch. More significantly, the arrows illustrate progressive runs. In the middle third, there is an incredible volume of runs, initially highlighting this verticality. By attacking and driving into space, players are engaging the opposition and creating space. They create disorder with their carries.

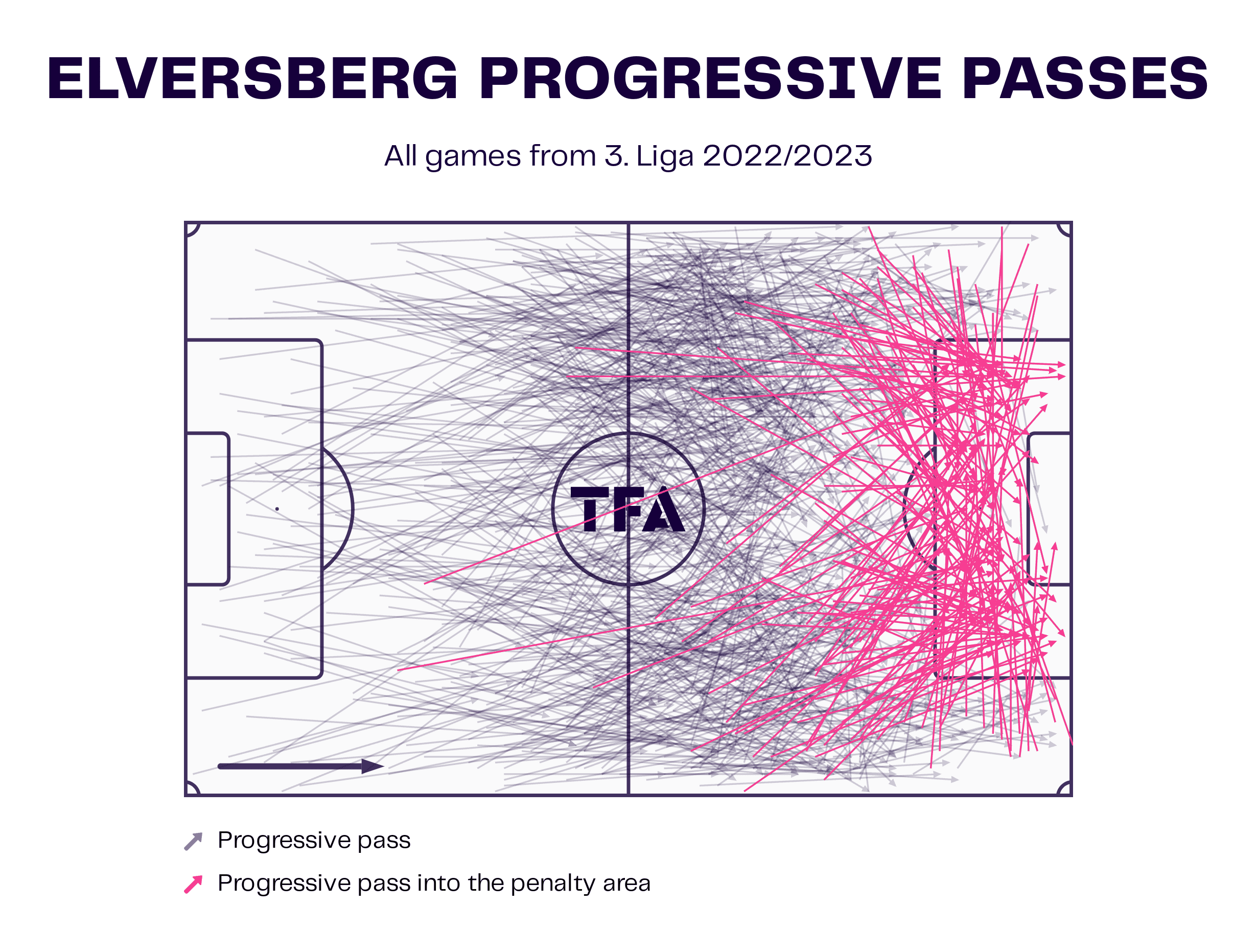

With progressive passes, there is a very similar trend. The volume is simply unbelievable, and it shows they are constantly looking to break defensive lines through more direct passes. There is an undeniable verticality in their actions, but how does this look on the pitch? Let’s take a look.

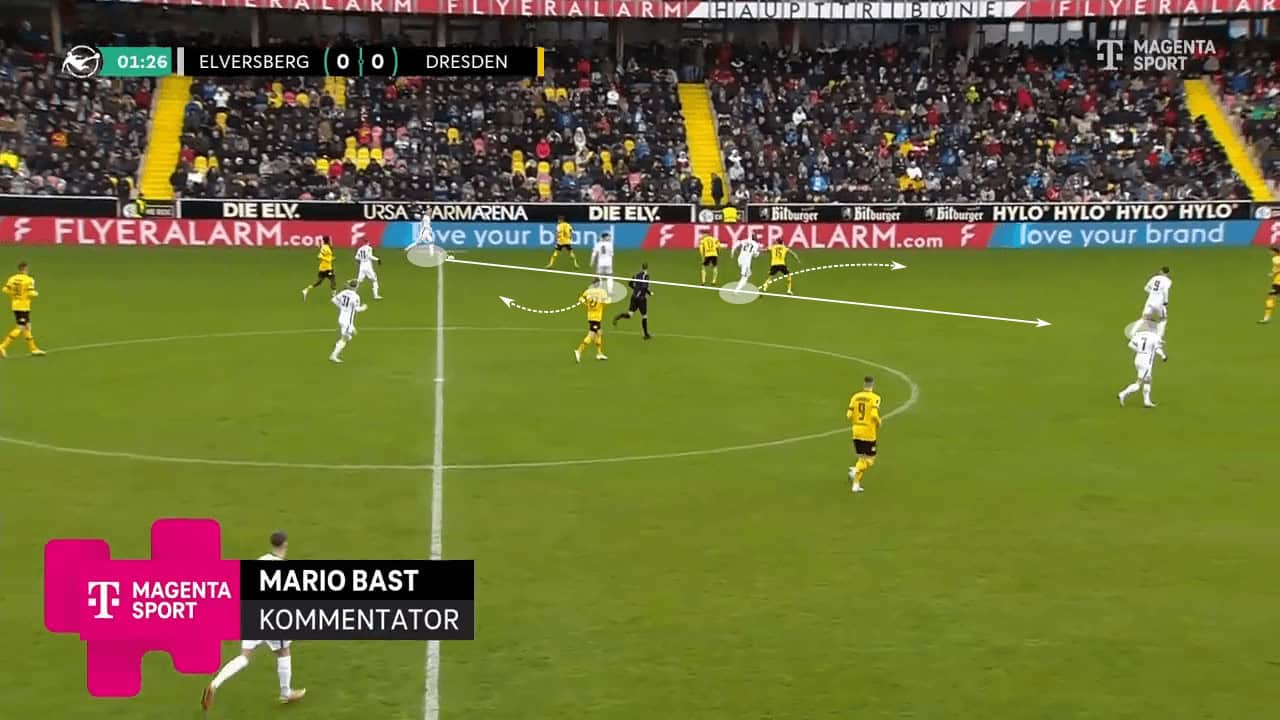

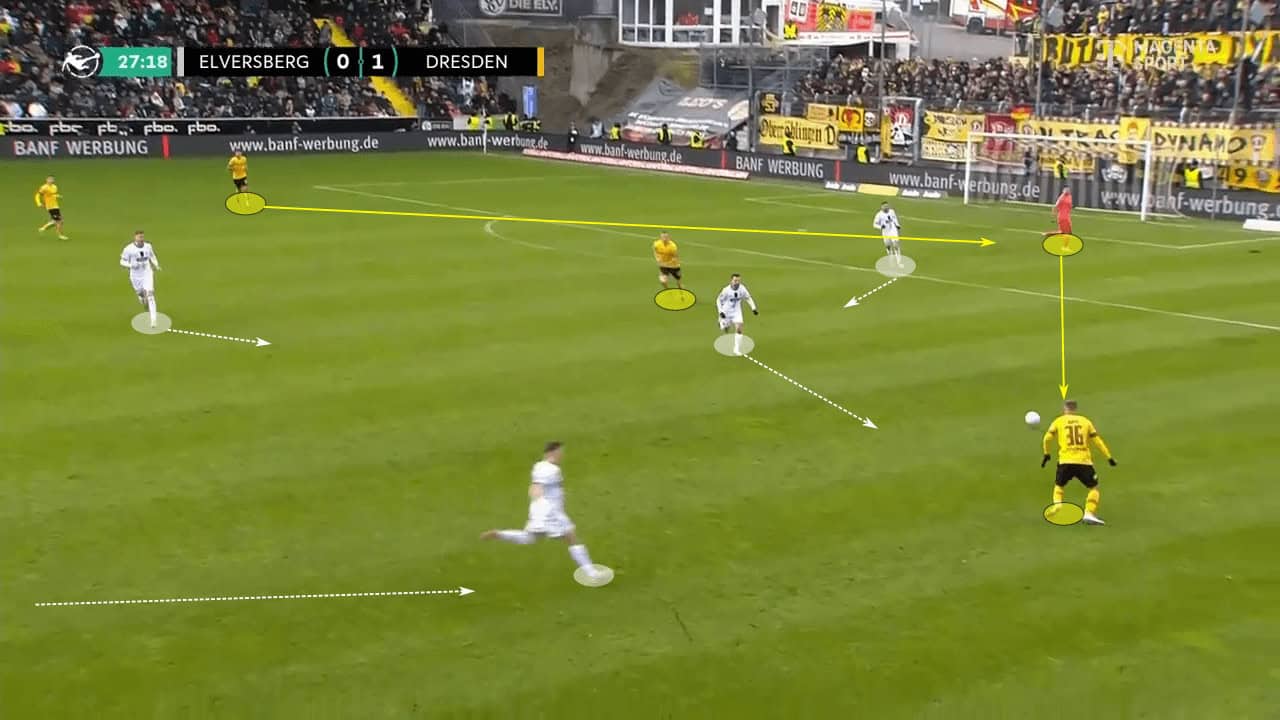

Briefly mentioned in the first section, their fluid roaming of spaces often looks to manipulate the opposition to create vertical options. The instance below clearly illustrates this. After dropping deep into the midfield, the centre-forward makes an outward run to the touchline. At the same time, the left midfielder, who has drifted slightly inside, moves further inside.

These movements have two purposes. The first is obviously to provide a passing option. After having provided initial support and not receiving the ball, they move again. Constant movement is essential to disrupting the defence and finding options to progress.

Additionally, the opposite nature of these simultaneous runs indicates the intention of clearing up a vertical passing lane to the other centre-forward, who is providing depth.

In the build-up, a different behaviour has a similar purpose. As they direct their build-up on the left side, numerous players provide support. By attracting the opposition’s high press, they create that space in the midfield for the centre-forward to drop into. With a few taller centre-forwards in their squad, they are able to utilise this target forward role effectively.

In these next two examples, we can also observe some of the wide dynamics and how they influence their verticality. In Steffen’s tactics, exploring the wide areas is not limited to the wide players. In fact, if there is space, anyone is free to attack it.

In this first instance, their possession is in a more initial stage of development and the fullback is much deeper. The right midfielder and nearest centre-forward are positioned on the border of the half-space with the wide channel. This inside positioning initially creates minimal width and frees up the wide channel for the runs and vertical passes made below.

However, their width can be very dynamic. Contrary to the instance above, the example below begins with maximal width. The right midfielder is hugging the touchline, dragging the defender with him. With this positioning, he is able to create the vertical passing lane to the centre-forward explored below.

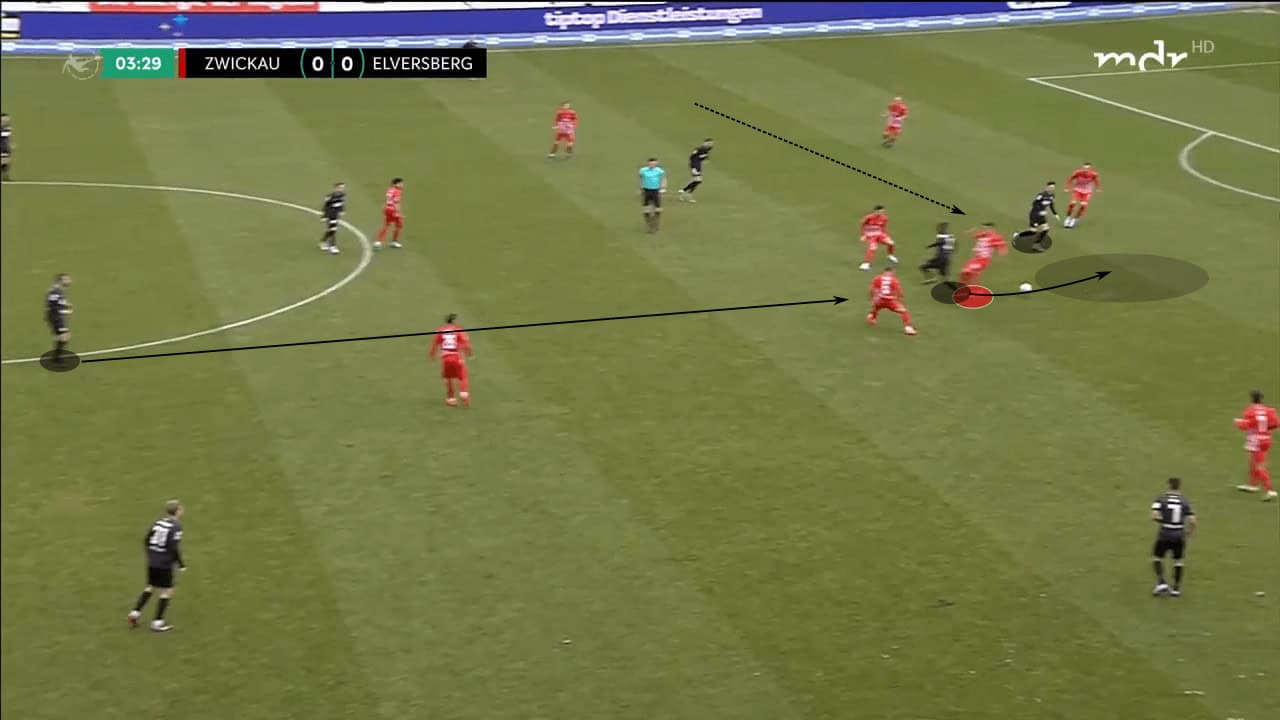

After recovering the ball, they also have a tendency to immediately be vertical. In the example below, after recovering the ball in their own third, two players immediately begin to make runs forward. The ball carrier is able to play the furthest pass into space for the centre-forward, initiating a counterattack scenario.

Verticality is a reoccurring theme in Elversberg’s tactics, especially in possession and transition. This is not only through direct passes but through broader behaviour, as explored above. The consistent theme of verticality throughout multiple phases once again highlights how Horst Steffen’s tactics unite phases through principles.

High intensity

As expected, Elversberg have an extremely high and aggressive pressing system. They are constantly applying pressure to the opponent’s possession, especially in high blocks. This intense defensive system primarily serves to recover the ball as early as possible, however, it also functions to create transitions and chaotic scenarios for them to exploit.

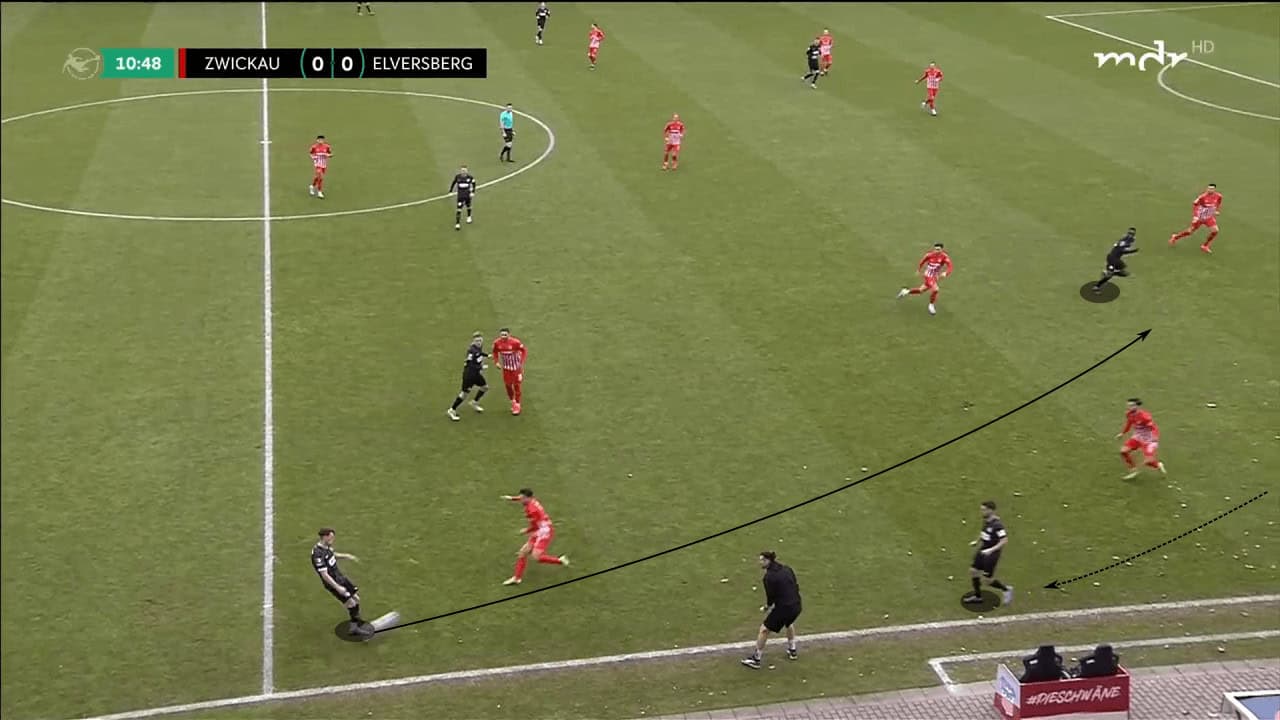

In this first image, we can identify the structure through which they often press. One of the centre-forwards, usually Nick Woltemade, drops to man-mark the opposition’s first midfielder. The other centre-forward applies pressure to the centre-backs. Once a side is chosen, the nearest winger applies pressure while the opposite significantly shifts inside. The two central midfielders support the four attackers.

Below, we can identify how significant this movement inside from the opposite wide player can be. After the opposition plays to one side, Elversberg’s far midfielder shifts all the way inside to box the opposition in, while the centre-forward keeps man-marking the first midfielder.

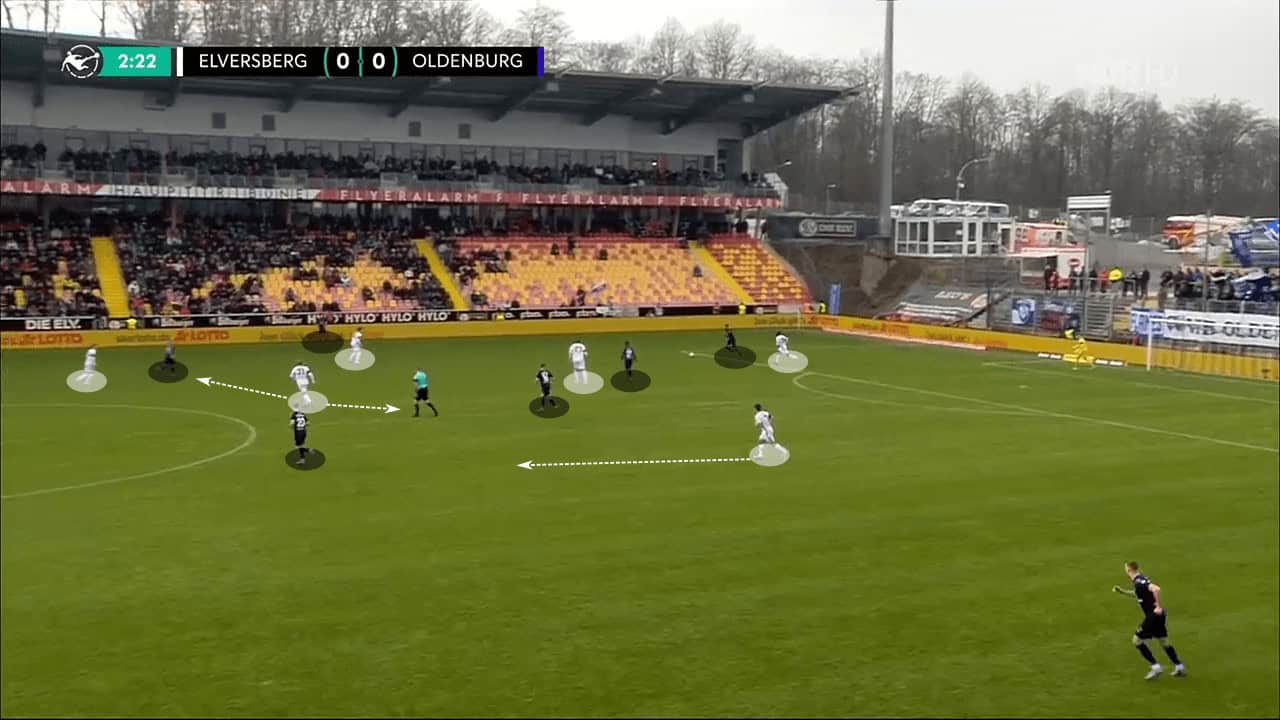

The two central midfielders provide immediate cover behind the four attackers. Depending on the opposition’s midfield structure, they may step up to help the centre-forward mark the options inside. If the opposition tries to find players dropping in from deep, the midfielders will follow these runners and keep them from turning, as highlighted below.

Depending on the scenario, the fullback can also be responsible for jumping forward to apply pressure. In the example below, the opposition recycles their build-up to explore the opposite side. To keep them from getting out wide, the opposite fullback immediately jumps to apply pressure.

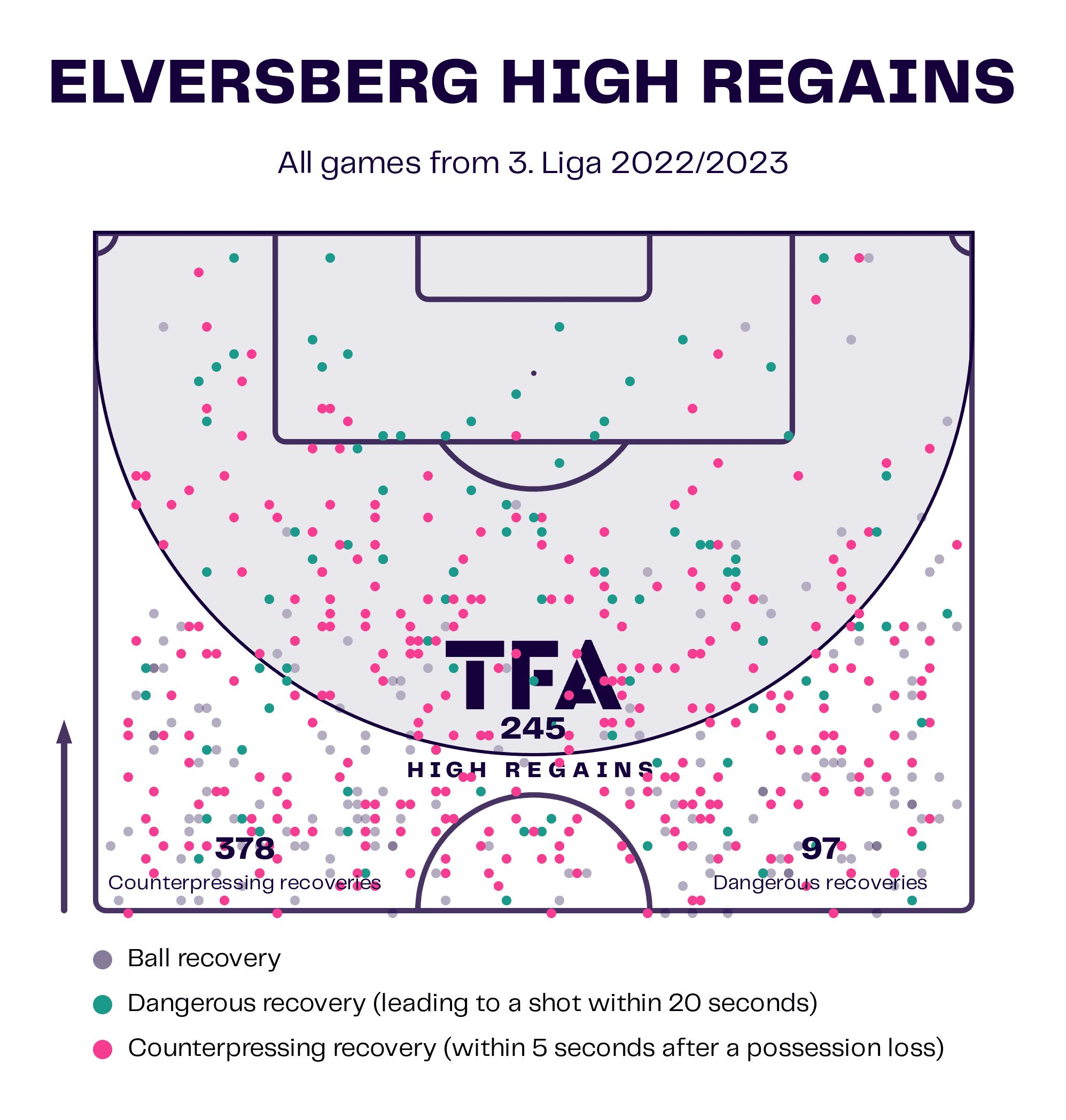

This season, Elversberg have made 245 high regains and 376 counter-pressing recoveries so far. These high figures highlight their aggressive and intense approach to defending. They have a very structured manner to do so, as identified below, and so far, it has proven very successful with Steffen’s side having the best defence in the league.

Conclusion

Horst Steffen is guiding Elversberg to a historic promotion battle into the 2. Bundesliga. Not only would this be the club’s first appearance in Germany’s second division, but it would significantly exceed every single expectation coming into the season.

The 54-year-old is doing so with a clear and organised tactical idea. The consistency in principles throughout phases allows us to identify patterns and ideas from a broader perspective, without needing to break the game into phases. Additionally, the structure blends concepts found in the likes of Napoli or Real Madrid with ideas often found in the top Bundesliga sides.

Comments