Lyon’s academy is a hotbed of footballing talent. One of the most exciting talents to have emerged from Les Gones’ youth ranks over the past decade or so is 24-year-old attacking midfielder Houssem Aouar (175cm/5’9”, 70kg/154lbs), who debuted for Lyon’s senior side in 2016/17 but really cemented himself in the first team the following campaign, in 2017/18.

It was early in the 2018/19 season after the French giants drew 2-2 with EPL champions Manchester City in the UEFA Champions League group stages when Aouar received a major rub as Pep Guardiola labelled the Lyon playmaker “incredible”.

Almost two years later, Guardiola’s former assistant at Man City, Mikel Arteta, had taken the reins at City’s EPL rivals Arsenal, and The Gunners were reported to have been chasing Aouar’s signature, with Lyon said to have been demanding no less than €60m to part ways with the young Frenchman.

Aouar ultimately remained at the Groupama Stadium beyond that summer and the next. However, with less than 12 months now remaining on his contract and coming off the back of a slightly lower-profile campaign than he’d enjoyed in the 2020/21 campaign, the Lyon talent is one of five players who Peter Bosz wants to be rid of this summer, per L’Équipe, with Les Gones said to now be open to receiving just €15m for Aouar — a significant drop from their 2020 asking price.

After a bad campaign by their standards in their first season under former Ajax, Borussia Dortmund and Bayer Leverkusen boss Peter Bosz, it’s no surprise that Lyon are initiating a fire sale. But why is Pep-approved, one-time €60m-rated Aouar part of that fire sale? And why has his stock dropped so much of late, as clubs (with all due respect) from a tier lower in stature than the likes of Man City and Arsenal — Real Sociedad, Real Betis and Nice — are said to be leading the chase for the Lyon star?

In this tactical analysis and scout report, we aim to provide some answers to these questions, as well as an insight into who and what exactly Aouar is as a player through analysis of his time at Lyon, the different systems he’s played in and different roles he’s been utilised within those tactics and systems to highlight the key strengths and weaknesses of the exciting playmaker’s game.

Unless otherwise stated, all stats and data used in this scout report have come from Wyscout.

Under Bruno Génésio

The Lyon manager who handed Aouar his debut in 2016/17 — and the one he played under for his first two full seasons as a first-team squad member — was Bruno Génésio, currently the boss at Lyon’s Ligue 1 rivals Rennes, who finished four places above Les Gones in the French top-flight last term.

So, how did Génésio utilise Aouar in those first couple of seasons? Quite effectively, anyway, though in a slightly different role to the one we’ve become accustomed to seeing Aouar playing over the last few seasons.

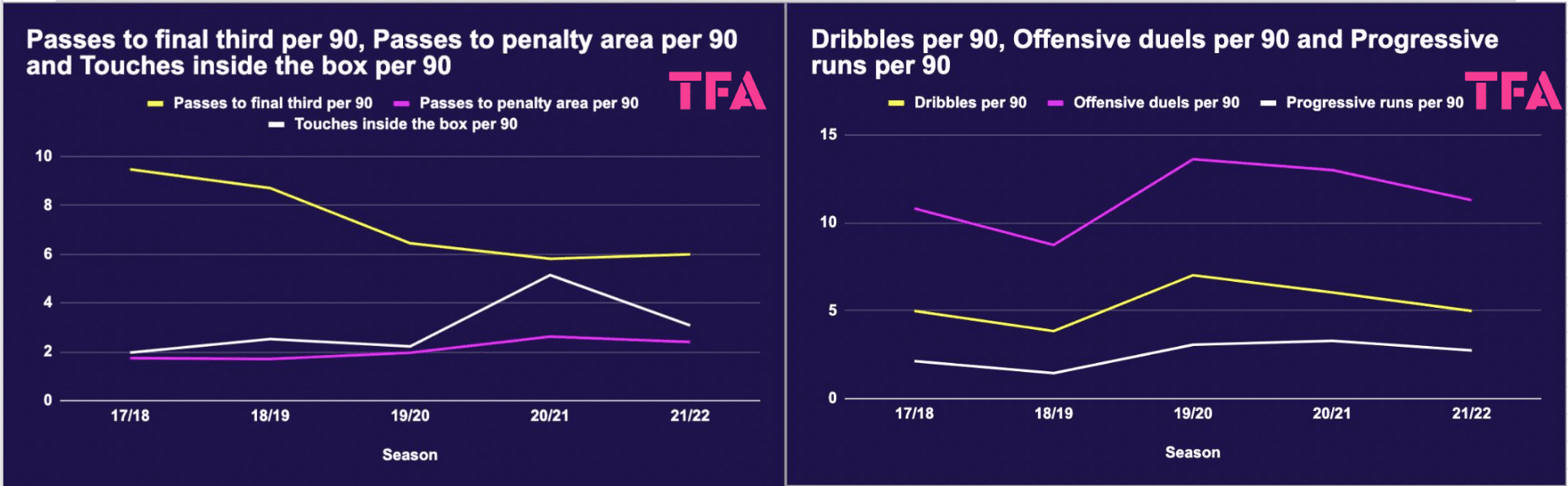

Figure 1 tells us a lot about how Aouar’s role has evolved over his five seasons in senior football thus far. The chart on the left shows us how the Frenchman generally made significantly more passes to the final third in his first and second Ligue 1 campaigns than he did in any following seasons, while his number of passes to the penalty area has slightly increased over the last two seasons and his number of touches inside the box has also increased in that time.

Meanwhile, aligning with his increased number of touches inside the box per 90 and lower number of passes to the final third per 90 are his higher number of dribbles, progressive runs and offensive duels per 90, as indicated by the chart on the right.

A pass to the final third is defined by Wyscout as: “Any pass that originates outside of the final third and the next ball touch occurs within the final third” while passes to the penalty area are defined as: “Any Pass that originates outside of the opposition’s penalty area and the next ball touch occurs inside the opposition’s penalty area.”

So, from the graph on the left, we can see that Aouar has been playing fewer passes into the final third but more passes into the box in recent seasons than was the case in his first couple of seasons under Génésio. At the same time, he’s been carrying the ball forward far more in recent seasons than he did in his first couple of seasons.

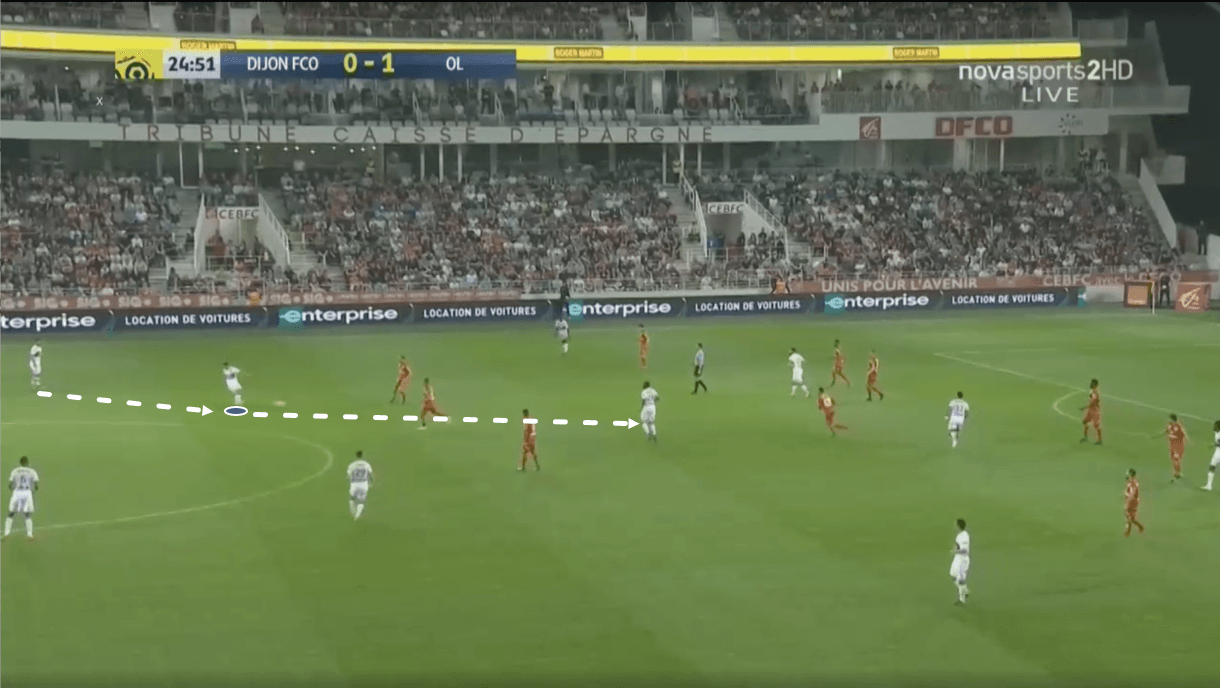

This makes a lot of sense, as it would line up with the requirements of the role he played under Génésio; this role saw Aouar playing a little bit deeper in possession phases than we’ve seen him playing in recent seasons, frequently receiving the ball from the centre-backs in settled possession, as figure 2 below shows an example of.

Here, Aouar has just received the ball from the left centre-back after dropping to form the left side of a double-pivot in Les Gones’ 2-2-3-3 attacking shape at this moment. After receiving, he can turn, pick out a teammate in some space in the final third and progress the ball to them via a line-breaking pass, such as the one in figure 2.

This was a regular sight for Aouar under Génésio, who clearly valued what the academy-produced talent could offer his side as a passer in the ball progression phase. This role also allowed Aouar to act as a deep-lying playmaker, with licence to exploit an opponent’s high line if the opportunity arose or split the backline with a through ball from deep.

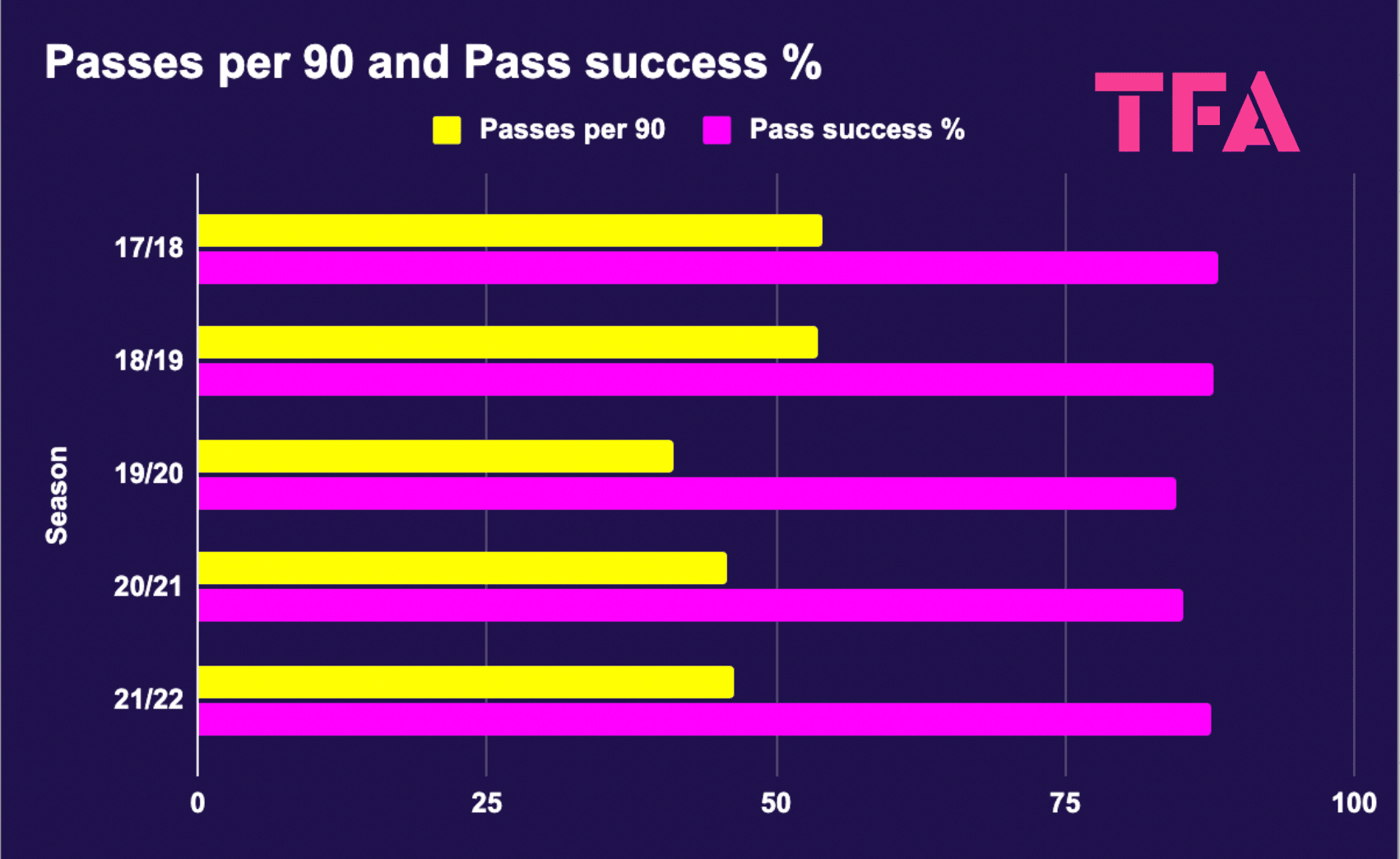

Aouar was far more involved in play as a result of this role and naturally made more passes, which we can see in figure 3. Despite his changing roles throughout his time at Lyon, his pass success rate has largely remained around the same level, though it did dip slightly under Génésio’s successor at Groupama Stadium — Rudi Garcia.

Under Rudi Garcia

Garcia was maligned by Lyon fans towards the end of his tenure at the club — somewhat unfairly, from a nonpartisan perspective, but fans had their reasons, with many citing style of play and lack of trust in youth as reasons for their anti-Garcia stance.

The 58-year-old did manage to guide Lyon to the 2019/20 UEFA Champions League semi-finals though, a feat that should surely be commended by a fan of any French club not named Paris Saint-Germain, at present.

Aouar played a starring role in that Champions League semi-final run, making six assists and scoring one goal in Les Gones’ run to that stage. He ended the competition with the second-most assists of any player, trailing only PSG’s Ángel Di María.

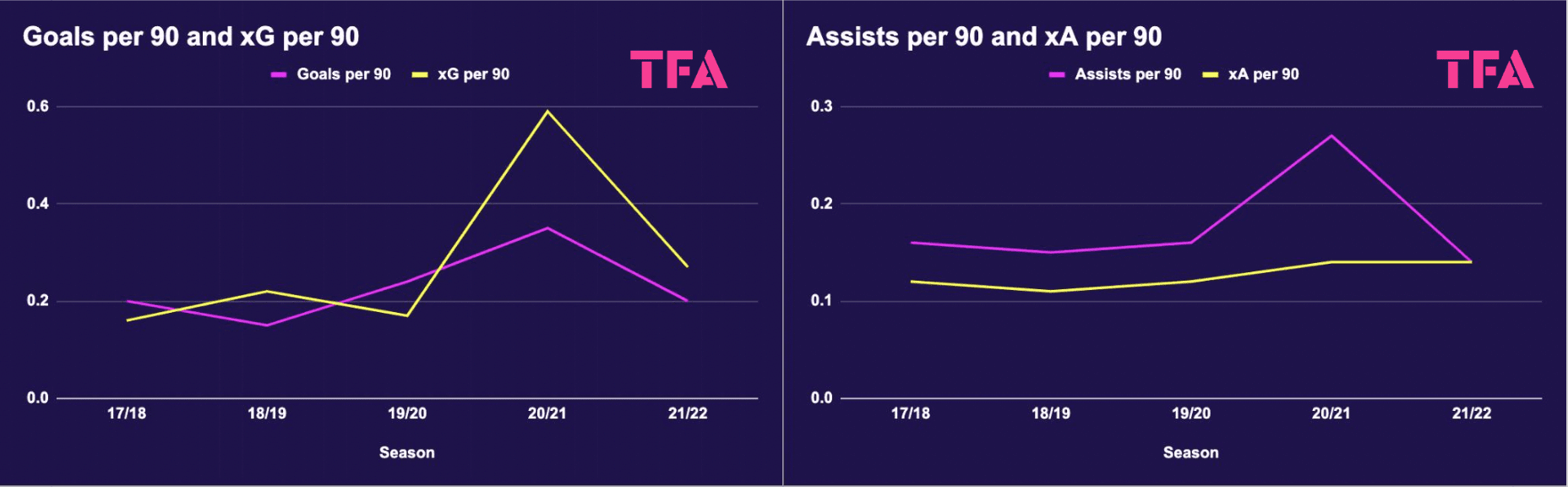

The playmaker produced his best goal contribution per 90 rate of his career thus far while playing under Garcia, along with his best expected goal contribution per 90 rate. We can see this visualised in figure 4, below.

It’s noteworthy that while he played in a slightly deeper role under Génésio, his expected goal contributions per 90 were only marginally lower during that early portion of his career than they have been over the last few campaigns, perhaps indicating how effectively Aouar managed to perform the deep-lying playmaker role.

However, there was a very clear uptick in his expected goal contribution rate and actual goal contribution rate, overall, once Garcia took the reins at Lyon. It should be mentioned that the first part of the 2019/20 season wasn’t spent playing under Garcia, but rather Sylvinho. However, Sylvinho managed Les Gones for just 11 games (Aouar for nine) before he was sacked, so it’s not really a period worth examining in too much detail.

Aouar has played more games under Génésio than he has played under any other coach, with Garcia coming up in second place — but the version of Aouar we witnessed under Garcia may be the most exciting version of the one-cap France international that we’ve had the pleasure of watching so far.

Redirecting our attention to figure 1, we can see that it was under Garcia that Aouar began occupying more advanced positions, receiving the ball in the final third more often and playing fewer of the passes into the final third.

Aouar played the third-most passes into the final third of any Lyon player in 2017/18 under Génésio — he dropped to playing the 14th-most passes into the final third for Lyon in 2020/21.

In this role, Aouar then began playing more passes into the penalty area, as this is the natural next step in the attack after receiving in the final third from a deeper player (this is also reflected in figure 1).

This may partially explain why Aouar became much more of a direct threat to goal under Garcia than he had been under Génésio — and it made him a far greater threat, in a role that he clearly enjoyed. With Lyon playing the second-most key passes of any Ligue 1 side in 2020/21, Aouar ended that campaign having played the third-most key passes of any Lyon player.

Also visualised in figure 1 is the fact that Garcia handed Aouar more freedom to exercise his dribbling quality. This was, again, connected with the change in role. Now occupying more advanced positions, Aouar enjoyed more opportunities to engage defenders in 1v1 duels, naturally resulting in more dribbles. The attacking midfielder was able to throw caution to the wind and be brave with his ball carrying more frequently now that he was receiving the ball in a more advanced, less vulnerable-to-transitions area.

This change in role and responsibilities, along with Aouar naturally growing in ability and confidence can also go some way to explaining his increased touches in the opposition box — another factor that likely impacted his increased goal contributions rate.

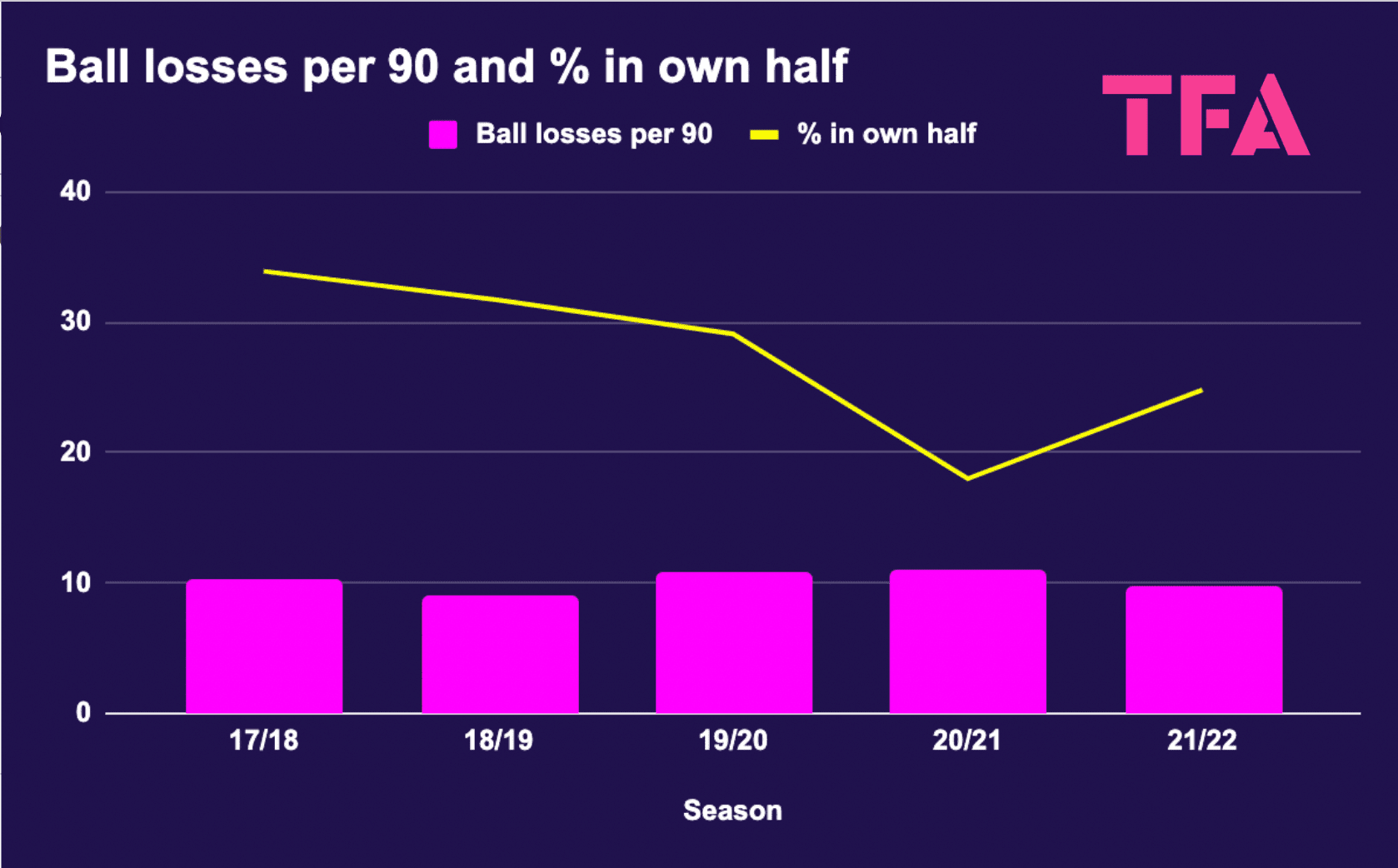

Playing in more advanced, congested areas of the pitch in a role that allowed more risk-taking naturally led to an increase in ball losses, though not a major increase, for Aouar. However, the portion of those ball losses that occurred in Lyon’s own half of the pitch has significantly reduced since Aouar’s time playing under Génésio, which we can see in figure 5 — another symptom of the playmaker’s change in role.

When given the freedom to take more risks and occupy more advanced positions, Aouar rewarded his team with excellent performances that led to Lyon’s joint-best ever Champions League showing in 2019/20, and Aouar becoming one of Europe’s most sought-after playmakers.

Under Peter Bosz

Last season, Aouar played under a new manager once more — Peter Bosz. The Rinus Michels-inspired Dutchman himself has emphasised the importance of quickly regaining possession via counter-pressing and applying pressure high up the pitch, pressing from the front, when discussing his playing philosophy in the past, and this much has been evident from watching Lyon evolve from Garcia to Bosz over the last year.

Lyon’s PPDA sat at 12.12 in Ligue 1’s 2020/21 campaign but it dropped all the way to 9.53 in 2021/22, highlighting Bosz’s increased emphasis on quickly regaining possession — and doing so as closely as possible to the opposition’s goal, ideally.

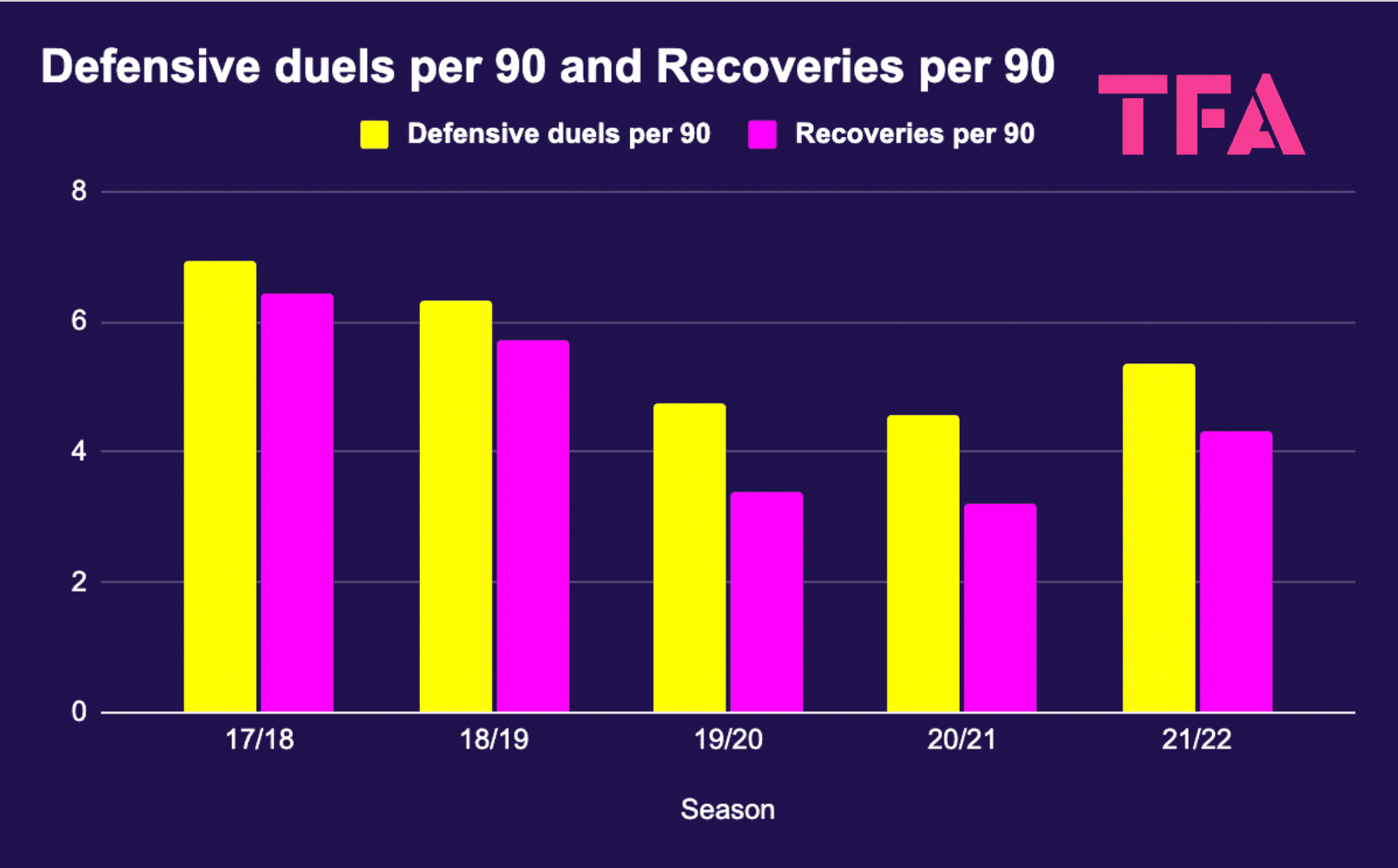

This shift in style can also be observed partially through some brief analysis of Aouar’s average number of defensive duels and recoveries per 90, visualised in figure 6. While Aouar was at his most defensively active during the early part of his career under Génésio (perhaps one of the traits that Guardiola will have most admired in the young Frenchman), that part of his game became more inconspicuous during Garcia’s tenure at the club.

Garcia put far less emphasis on the need to quickly regain the ball close to the opposition goal than either Génésio or Bosz. That’s not to say he felt it was entirely unimportant, of course. But for some coaches, like Bosz, ensuring an intense high press is paramount.

Bosz had Aouar engaging in more defensive duels and making more recoveries per 90 than he did in any season since Génésio was in the Groupama Stadium hot seat. Additionally, the majority of Aouar’s recoveries last season came in the opposition’s half; this was never the case under Génésio, when his percentage of recoveries in the opposition’s half was 42.3% for 2017/18 and 43.5% for 2018/19, again, with Aouar typically playing a deeper role in that part of his career.

Still, while Bosz arguably dragged more pressing out of Aouar than we’d ever seen in his career, he failed to perform as the pressing monster that a coach like Bosz requires in his first/second line of pressure — and that thrives within a system like Bosz’s.

Aouar’s Lyon teammate, Lucas Paquetá, on the other hand, was a major pressing monster who Bosz undoubtedly loved working with last season.

Per Statsbomb via FBRef, when compared with other attacking midfielders/wingers from Europe’s top-five leagues, Paquetá ranked in the 99th percentile for tackles, 99th percentile for tackles in the attacking third, 99th percentile for successful pressures, 91st percentile for pressures in the attacking third and 98th percentile for defensive actions leading to a shot attempt — just to name a few of the most relevant defensive metrics in which the Brazilian performed impeccably.

In comparison, Aouar ranked in the 82nd percentile for tackles, 72nd percentile for tackles in the attacking third, 52nd percentile for successful pressures, 66th percentile for pressures in the attacking third and 63rd percentile for defensive actions leading to a shot attempt — not terrible but not outstanding and metrics that pale in comparison to teammate Paquetá.

Playing in a system that requires the attacking midfielders to be defenders from the front and use their skills without the ball for their playmaking as much if not even more than they use their skills with the ball for this purpose has played a big part in Aouar’s stock falling so much, as he is nowhere near as good as Paquetá when evaluated by these standards.

This does not mean that Aouar is a far worse player than Paquetá, but they are different players — and while they could conceivably play in a system that got the best out of both, in their current roles in Bosz’s system with Aouar playing largely from the left side of attacking midfield next to Paquetá as either a ‘10’ or occasionally on the right side of attacking midfield — Aouar has been shown up as less suited while Paquetá has been put in a position to thrive.

It’s like watching two Formula 1 drivers on the same team with the same car, but the car is built perfectly for just one of those two drivers’ respective styles, leaving that one automatically as the team’s number one, and the other being little more than a support act.

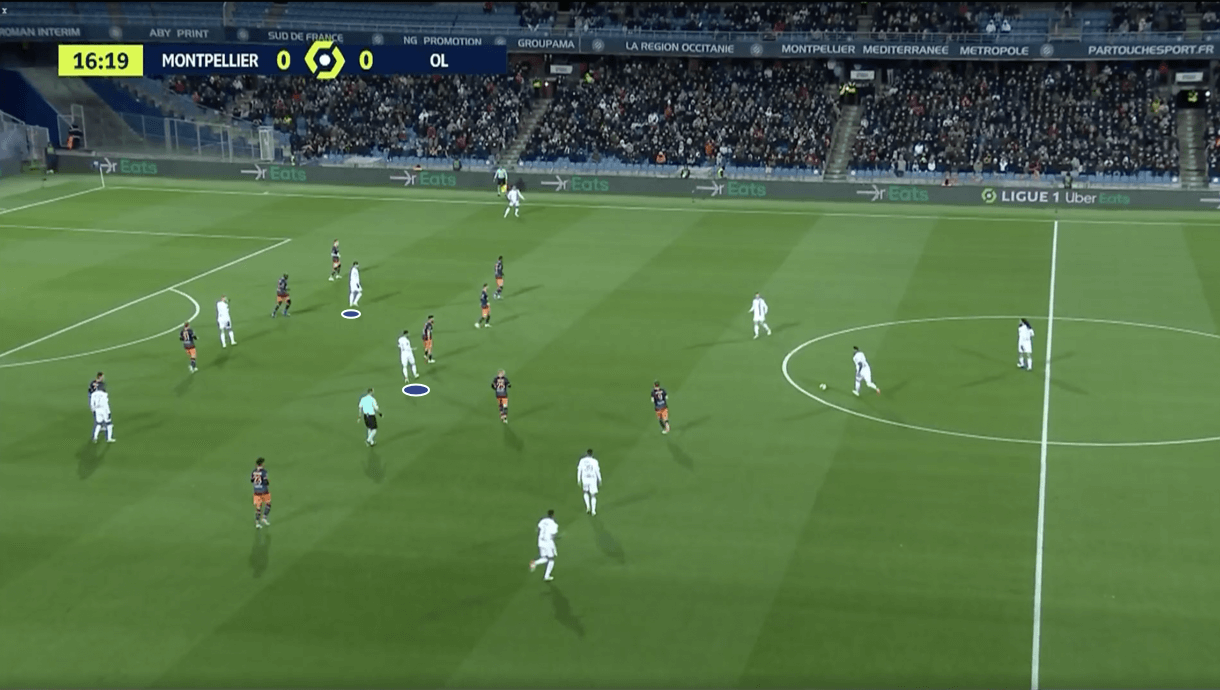

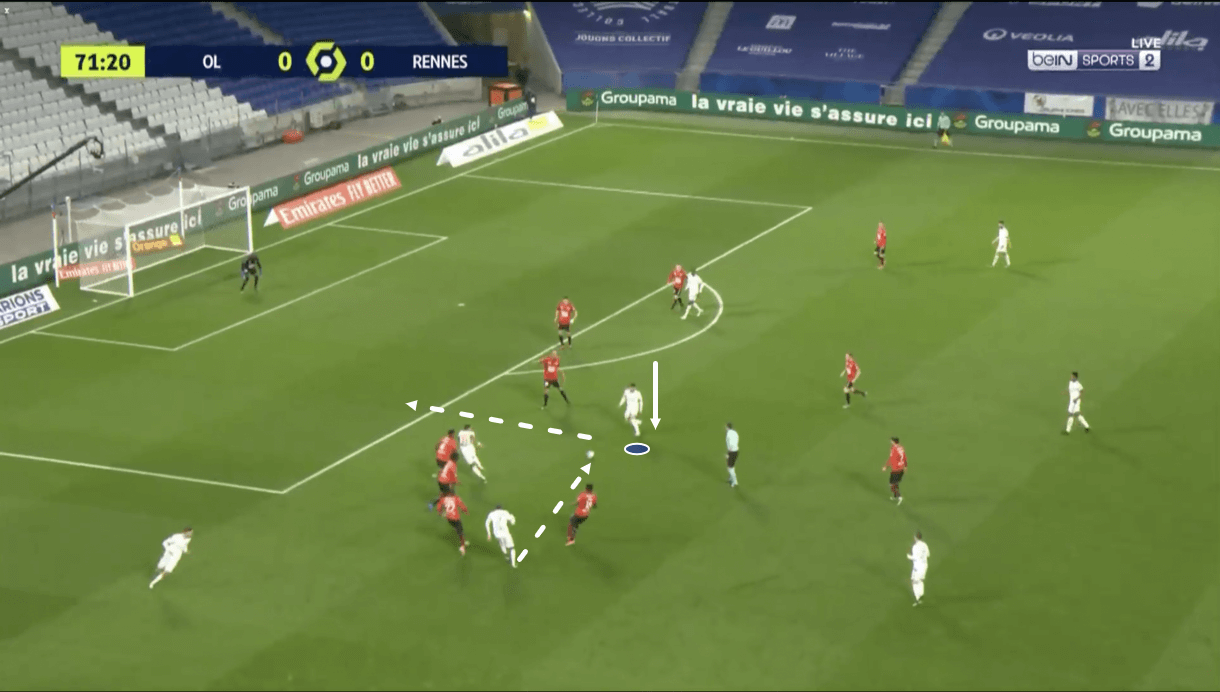

If deployed together in a midfield three, it’s been common to see Aouar and Paquetá line up similar to how we see them in figure 7, with Paquetá positioned very high and Aouar playing slightly deeper — though not as deep as he played during Génésio’s tenure. Aouar occupies the ‘8’ role on the edge of the final third, while Paquetá plays the ‘10’ role, sitting just off the shoulder of the striker.

One of the common plays in Bosz’s Lyon playbook has been for the centre-forward to drop deep, making himself available for a ball to feet from deep and hopefully, for Lyon, dragging an opposition defender out with him — thus creating space for Paquetá to dart in behind, giving his team a higher, more direct option.

Paquetá has enjoyed making runs such as the one we see in figure 8 this term, and he has succeeded in this role heavily reliant on quick movement to disrupt the opposition’s shape, somewhat reminiscent of movement you’d have seen Dele Alli making during his prime years at Tottenham Hotspur.

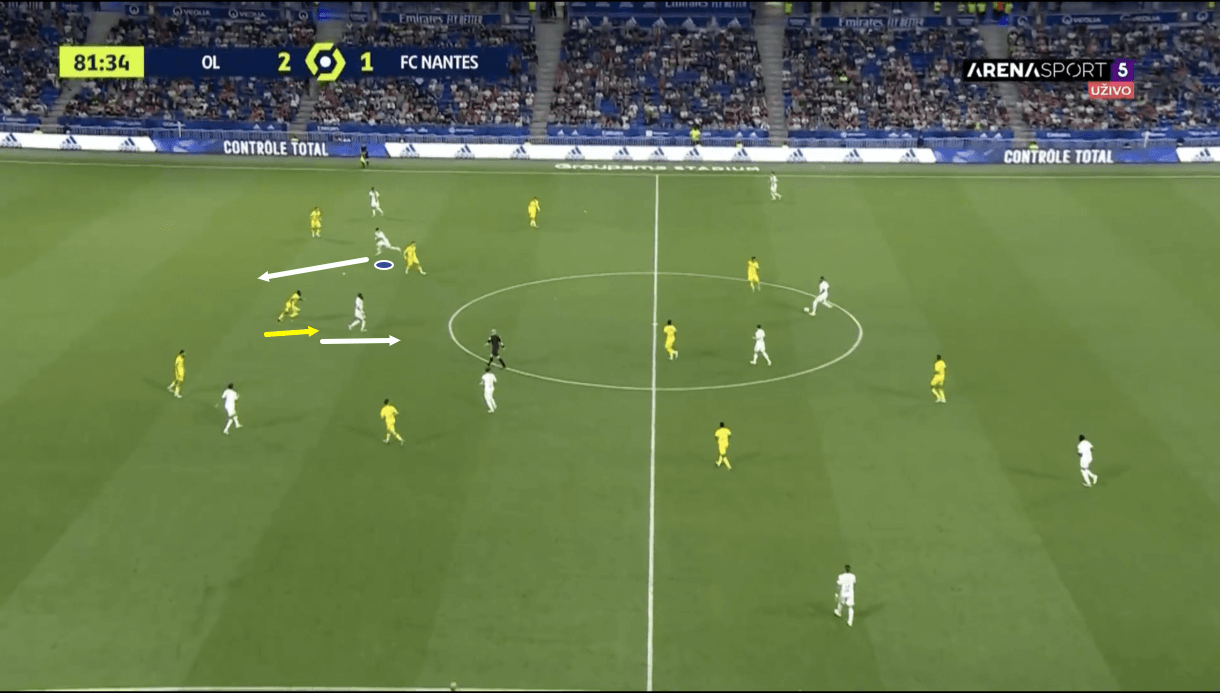

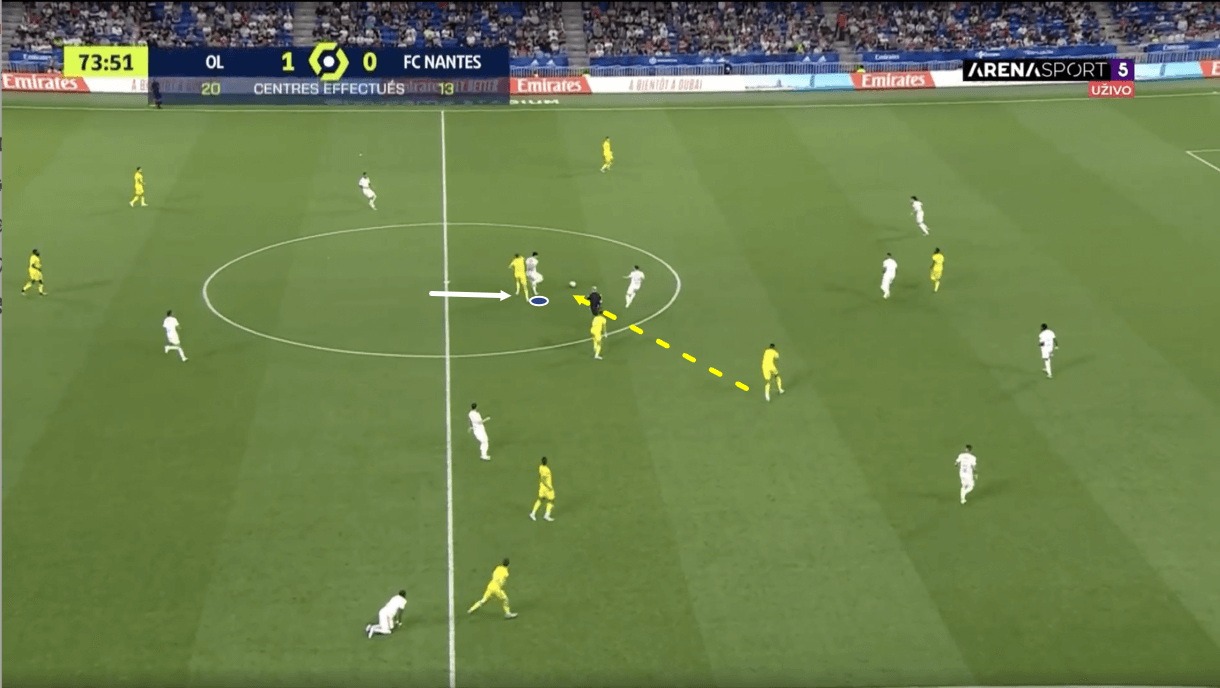

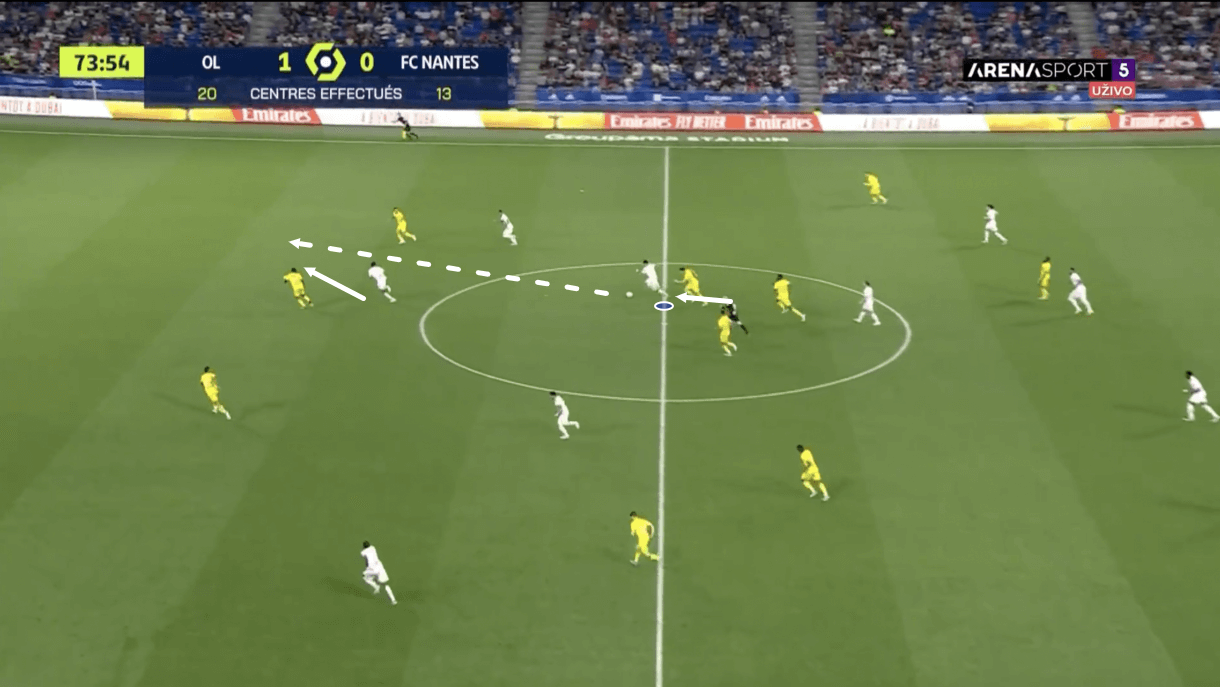

Again, however, where Paquetá truly thrives is in his defensive work rate and ability to think and play quickly under pressure in transitional moments. We see an example of Paquetá performing this role in figures 9-10. Just before figure 9, the opposition sent the ball into midfield but Paquetá reacted quickly to pounce on the loose ball and regain possession for his side in a sensitive area for the opposition to be turning it over.

After getting on the ball and smoothly turning in the centre to pull away from the opposition player, Paquetá drove forward for a couple of steps before driving the ball through, in behind the opposition’s backline for his centre-forward to chase down.

These are the kinds of situations in which Paquetá thrives — chaotic moments in which the opposition are disrupted and quickness — mental and physical — are required to take advantage of the situation. This is the kind of attacking midfielder who thrives under Bosz, but it’s not exactly the kind of attacking midfielder that Aouar is.

What kind of attacking midfielder is Aouar?

So, with all of that said, after establishing one kind of attacking midfielder that Aouar (unfortunately, for Bosz) is not, what kind of attacking midfielder is he?

Firstly, Aouar thrives when required to be the man to flick the switch and turn a period of settled possession into a goalscoring chance in an instant. We’ll see some examples of this in the following images, beginning with the passage of play shown in figures 11-12.

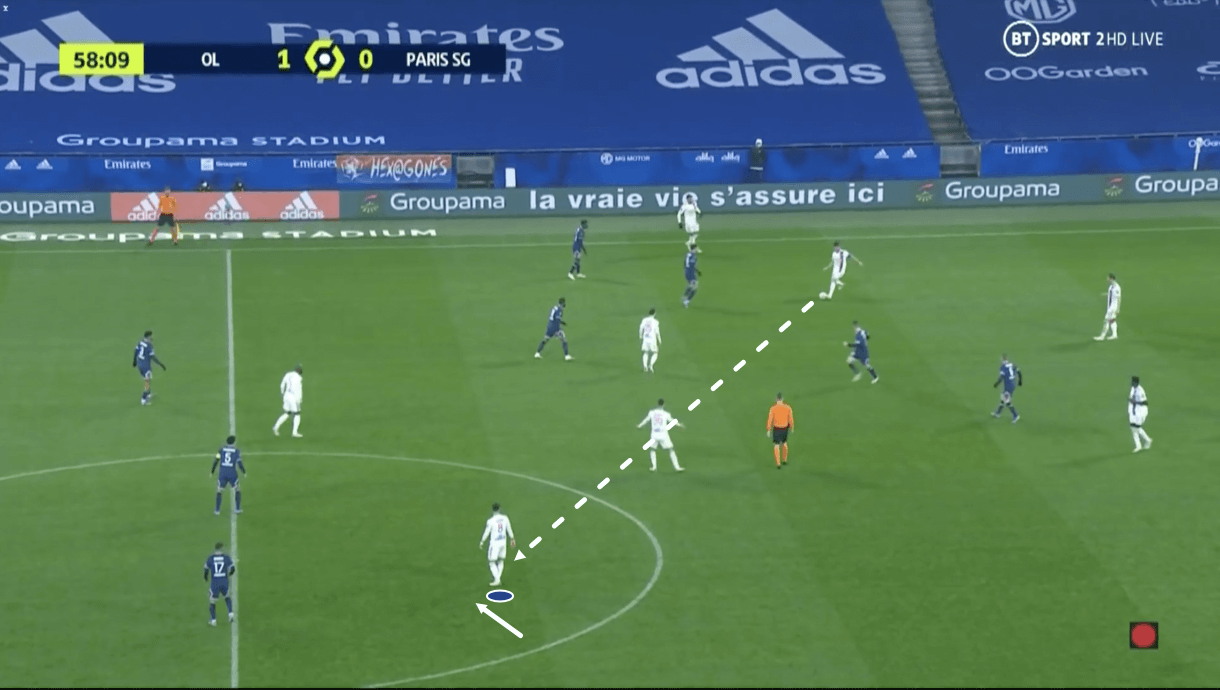

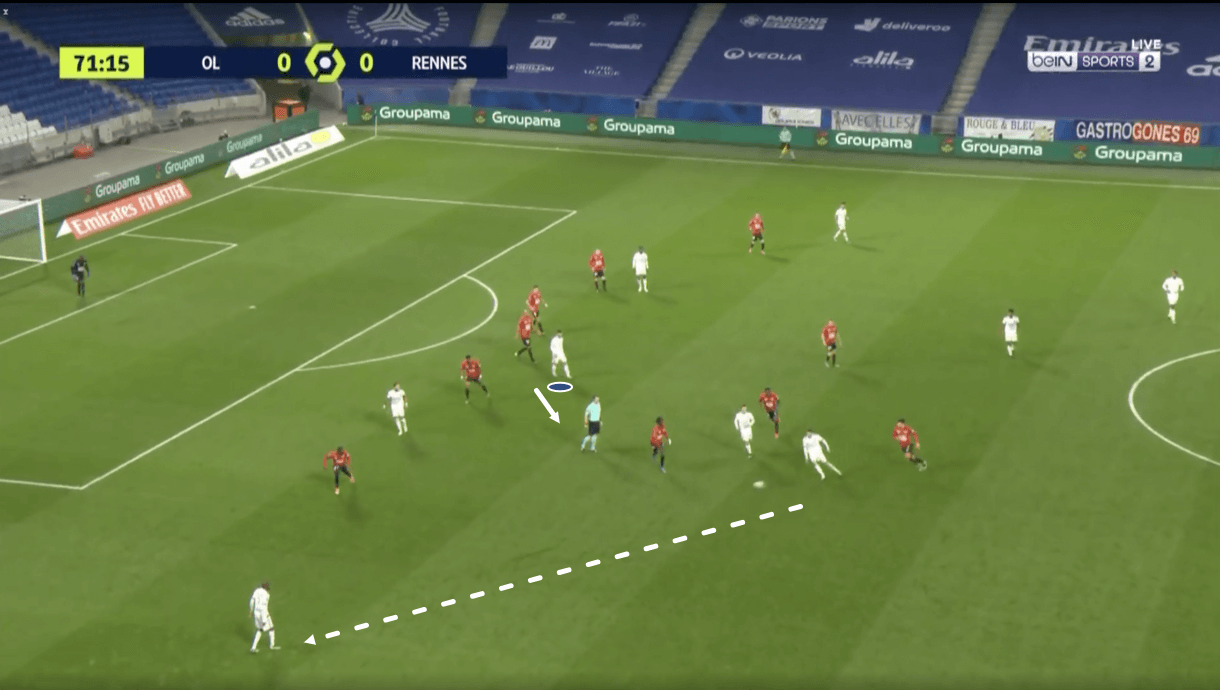

In figure 11, Aouar has just subtly moved from the left to the centre, putting himself in the passer’s line of sight just as this line-splitting progressive pass is set to be played.

This is textbook Aouar; he ghosts around sneakily and subtly without the ball, making seemingly innocuous movements with something of an air of disinterest about him, luring the opposition into a false sense of security as he nestles into a pocket of space waiting for a teammate to pick him out.

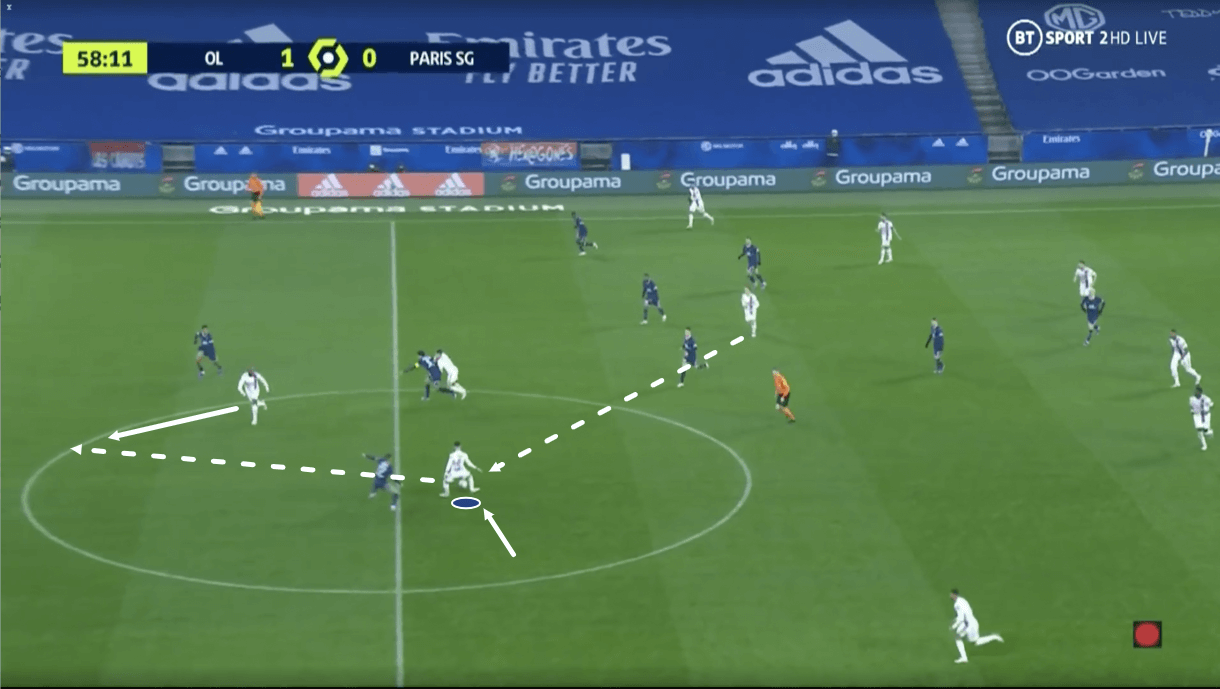

When the ball arrives at his feet, as occurred in figure 12 here, he comes alive — not rushing into things, as he doesn’t need to, he found the space he needed to buy himself all the time in the world to comfortably approach the ball and carefully carve the opposition open at his own speed.

It’s common to see Aouar get on the end of a progressive pass like this one and then, with one touch, slightly change the ball’s direction, put a little bit more pace on it and allow that ball to then split the defence apart and set a teammate up for success. We see one example of that in the images above and we can see another passage of play in which Aouar performed like this in figures 13-14.

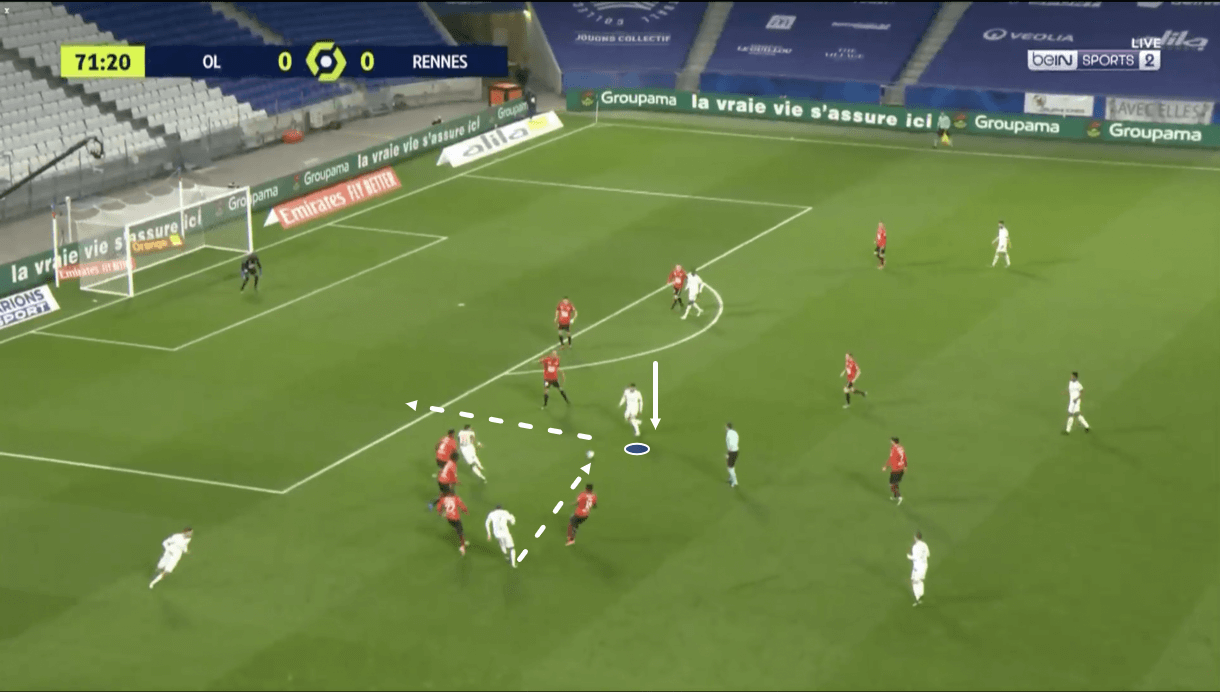

In figure 13, the ball has been played out to the left wing, with Aouar positioned centrally at this moment. As the ball moves out wide, attention goes to the winger, allowing Aouar to go into stealth mode. He slowly starts walking away from the opposition backline here, subtly creating just enough space to free himself up to make a move into even more space just a few seconds later, becoming a great passing option for the winger and setting his team up for success yet again.

As play moves on into figure 14, we see that Aouar ends up receiving the ball in tonnes of space just to the left of the ‘D’ on the edge of the box. As he moved into this area, he created a triangle with the ball carrier and his teammate on the nearest defender’s shoulder, looking to make a move in behind.

As the 24-year-old playmaker receives the pass with nobody around him thanks to his masterful movement preceding the ball reception, he approaches it casually with full confidence in his ability to perfectly pull off what he’s about to do.

He nonchalantly lifts back his weaker left foot and, again with one touch, slides the ball through the gap in the opposition’s defence into the inside lane for the runner in behind to chase the ball down, creating a 1v1 with the opposition goalkeeper.

Finding space during low-tempo periods of settled possession just outside the penalty area and then making the attack come alive as if it were putting him to sleep — being the man to flick that switch and turn up the tempo at just the right moment — is where Aouar thrives as an attacking midfielder.

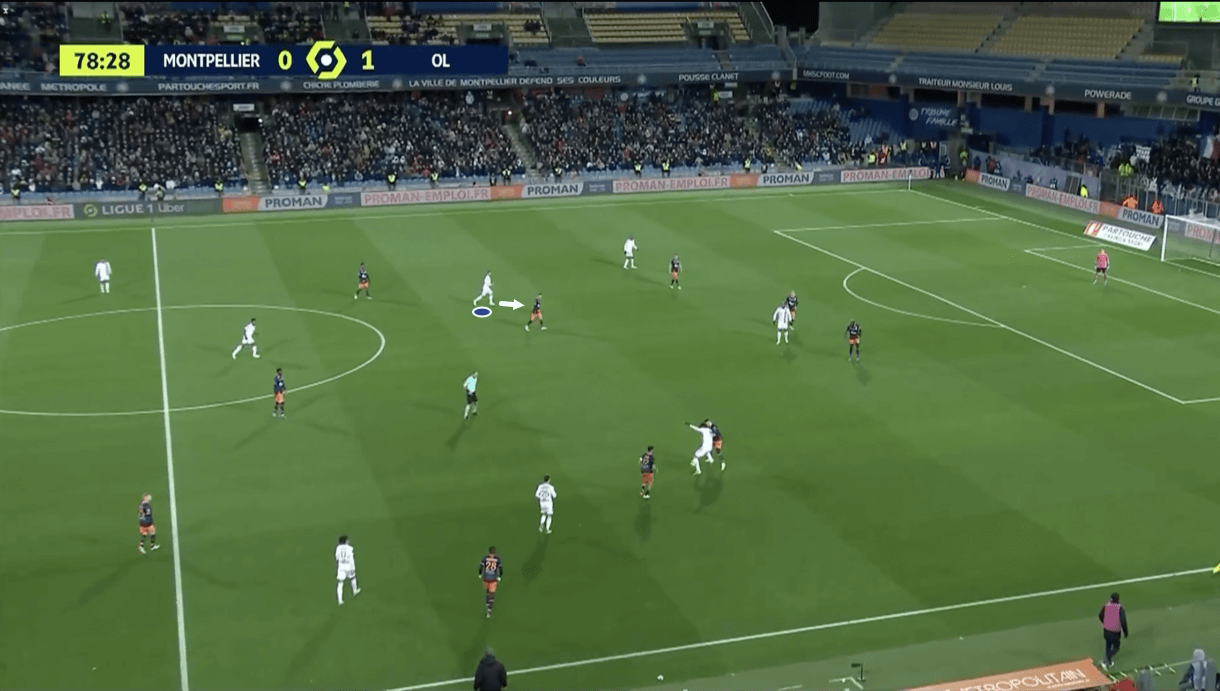

We see another example of the attacking midfielder subtly ghosting into a dangerous position with his off-the-ball movement while the opposition aren’t paying close enough attention to him in figures 15-16. Firstly, in figure 15, we see one of Aouar’s Lyon teammates fighting for the ball in a duel with an opposition defender on the right wing. As this occurs and attracts the opposition’s attention, Aouar sees an opportunity to move into zone 14 on the opposition holding midfielder’s blindside.

The playmaker pulls off this subtle movement with ease, anticipating that his team would come out of this duel in possession and take advantage of the midfielder’s intelligent off-the-ball movement just seconds later.

Of course, this was a gamble. If Lyon hadn’t come out of this duel with the ball, then Aouar would be poorly positioned to help counter-press. However, Aouar is the kind of player to think about where he needs to be to help his team when they leave a duel like this with the ball, not the kind of player to consider where he needs to be in case they lose the duel.

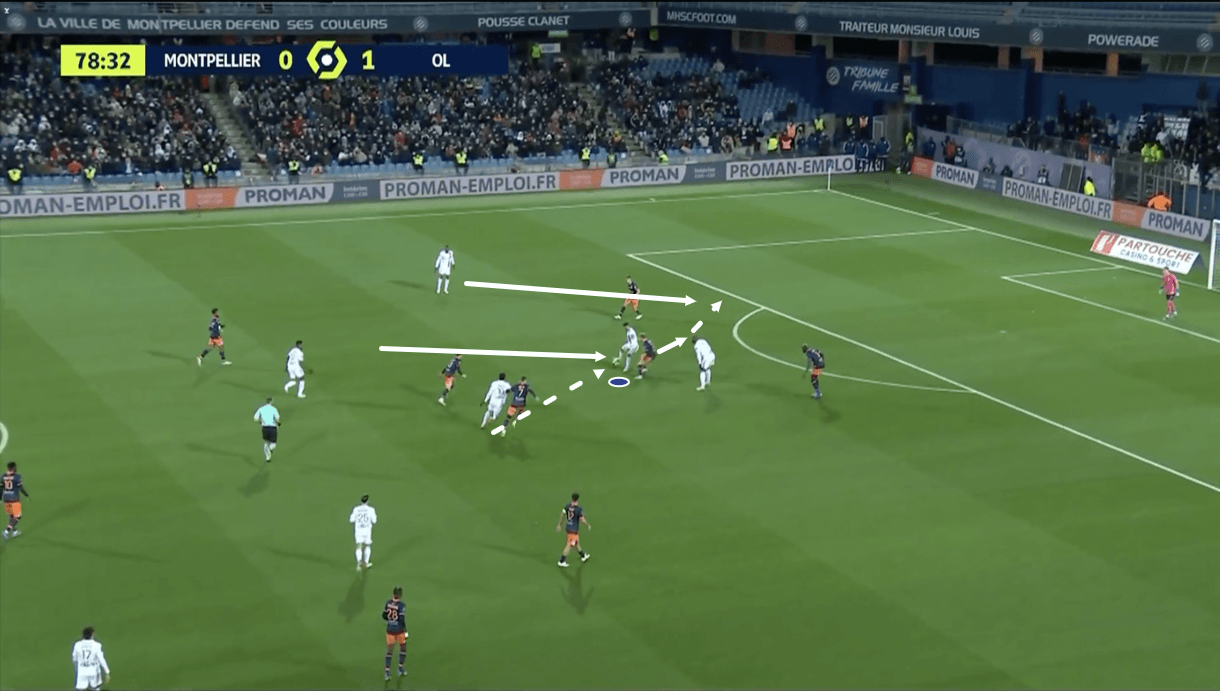

As his side approaches the centre of the pitch, Aouar ends up receiving the ball in zone 14, dragging an opposition centre-back out from the backline to deny him space between the lines, in the process. This is where Aouar’s dribbling quality comes into play.

The 24-year-old playmaker is very comfortable in tight spaces and loves drawing opposition players in on him when receiving in space in advanced positions, as we can see in figure 16. He backs himself to get out of trouble via his technical skill, quick-thinking, quick feet, agility and balance. These traits were all on display in this particular example to help Aouar evade the defender and get his team in on goal.

As the play moves on from figure 16, the playmaker receives the ball on his stronger right foot while turning. He leans his body into the defender rushing to take his back, using the momentum to swivel around the defender and place himself goal-side of him in one quick movement — demonstrating excellent decision-making, quick-thinking, as well as some brilliant agility and balance.

After swivelling around the defender, Aouar creates a great opportunity to slide the ball into the path of the out-to-in run from the left-winger, which he does, creating a 1v1 for that player with the opposition’s keeper.

As well as immense mental, technical and physical skill as far as dribbling is concerned, this demonstrates Aouar’s selflessness. He’s a playmaker through and through, always looking at how he can help his team progress into the best possible position at any given moment. If that means he goes it alone, he is happy to do so but he’s happy to set up a teammate if they’re in a better position too — that’s never an issue for Aouar.

Conclusion

So, to conclude this tactical analysis and scout report on Houssem Aouar, it’s clear that he isn’t the best-suited attacking midfielder for Peter Bosz’s Lyon, and this is one big reason why his stock has fallen of late. However, as is evident from his goal contribution numbers, he really hasn’t fallen off that much at all even if the hype has died down now that he’s playing alongside Paquetá in an environment that suits the Brazilian better. To ignore Aouar’s quality simply because he’s not in the best possible environment would be foolish.

He’s got less than a year remaining on his contract and if Lyon’s reported €15m asking price is true, then Aouar represents excellent value in the 2022 summer transfer market.

If put in the right role, system and environment, Aouar can be the star playmaker for a top-five league side, without a doubt. Don’t be surprised to see him rekindle the form he displayed in 2019/20 and 2020/21.

Aouar performs best when allowed to be the team’s main creator, turning settled periods of possession into goalscoring opportunities like the flick of a switch. He loves taking on defenders in 1v1 duels, playing teammates in for 1v1s with the keeper with one-touch passes when possible, and drifting around subtly without the ball to make himself a good passing option in the final third for ball progression.

Equally, if required, Aouar is versatile enough to play a deeper role and receive from the backline, which he displayed in his early years at Lyon under Génésio. With that said, from what we’ve seen of him over the last few seasons, we’d argue that his best role is in the final third, receiving passes from the deeper midfielders with the freedom to drift around, find space and play killer balls in behind the backline.

In this role, with the right system and team, Aouar is an exciting one to watch and it’ll be interesting to see where the Frenchman ends up if he does finally depart Lyon this summer.

Comments