There are four phases of play in football: attack, defence, attacking transition and defensive transition.

Carlos Corberan once stated that if a team executes all their actions well in these phases, then they are playing good football.

This statement, however, is slightly tongue-in-cheek as this is something that is easier said than done, which we’re sure Corberan is very much aware of.

These four phases are all related and influence one another.

When in possession, teams have to find the right balance between being enough of a threat in attack, without being too vulnerable in the defensive transition.

The term that is used to portray this balance is rest defence.

This tactical analysis piece will be an analysis of how positional attacking rotations affect the rest defence tactics of a team.

Rest defence and attacking football

By now, for most people who are engaged in the tactical aspect of the game, the term rest defence is well known.

Rest defence is a term that refers to a structure that a team holds when in possession, which allows them to immediately defend once possession has been lost.

As a result, this concept directly ties into counter-pressing.

The rest defence of a side usually consists of players in less advanced areas of the pitch and allows teams to cover spaces and players to have close proximity to opposition players in order to nullify counterattacks and sustain “pressure” in their own attacks.

As a result, when creating an attacking structure and formulating principles of play, coaches will often have to take into account whether or not the structure offers sufficient protection in the defensive transition phase.

As stated earlier, finding this balance is easier said than done, as player actions directly influence how effective a structure is in both phases.

For example, when attacking, a team will look to create space in a number of ways such as certain players providing width, players pinning the last defensive line of the opposition, runs from depth as well as positional rotations to name a few.

When deciding what actions to highlight and implement in a team, how these actions affect the defensive transition in the next phase needs to be factored in.

Positional rotations as well as flexible movement from players are particularly intriguing from a tactical theory point of view when it comes to analysing the balance sides need to find between attack and the defensive transition.

This is due to the fact that, on first thought, it would seem as if these actions can only negatively affect a side’s rest defence, but this all depends on which players are rotating and how a team compensates for these rotations.

Arsenal’s structure and rotations

Mikel Arteta’s Arsenal have made a surprising push for this year’s Premier League title, with one of the hallmarks of the side being their quality in the attacking phase of the game.

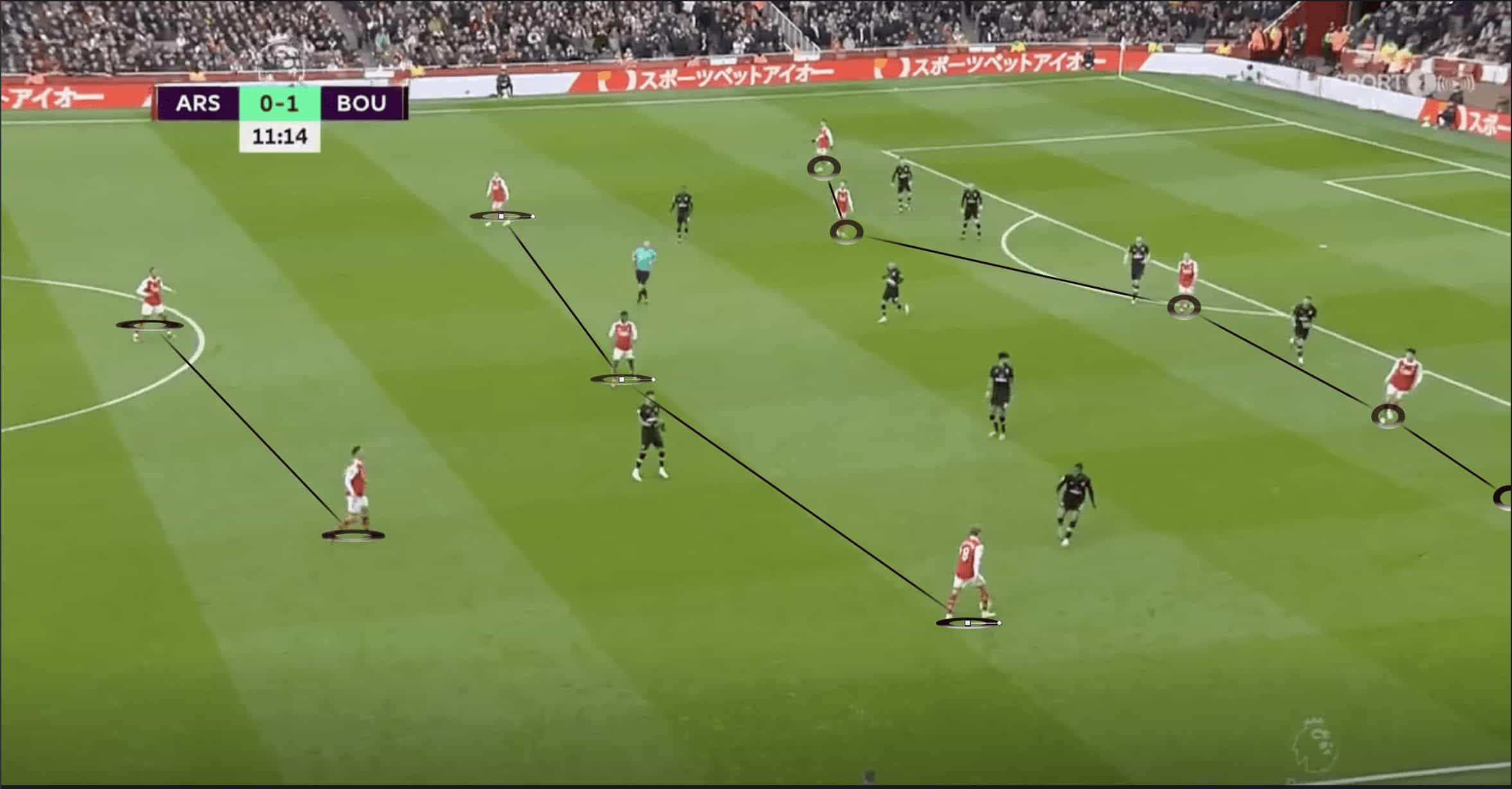

Arsenal on paper line up in a 4-3-3 but are often structured in a 2-3-5 shape when in possession in the opposition’s half, with their two full-backs inverting into the midfield, although the left-back has licence to determine when to push more into the centre, in order to create a double pivot.

Two of their three midfielders push further up the field between the opposition’s defensive and midfield line in the halfspace, with the wingers providing width, stationing themselves near or by the touchline.

Before delving into some of the roles and actions made by players in attack, it is important to understand how this structure looks to control defensive spaces.

It is also important to mention that, whenever a side is involved in the defensive side of the game, compactness between players as well as balanced player positioning across certain spaces is important.

This allows teams to be able to apply pressure and thus have control in the defensive phases.

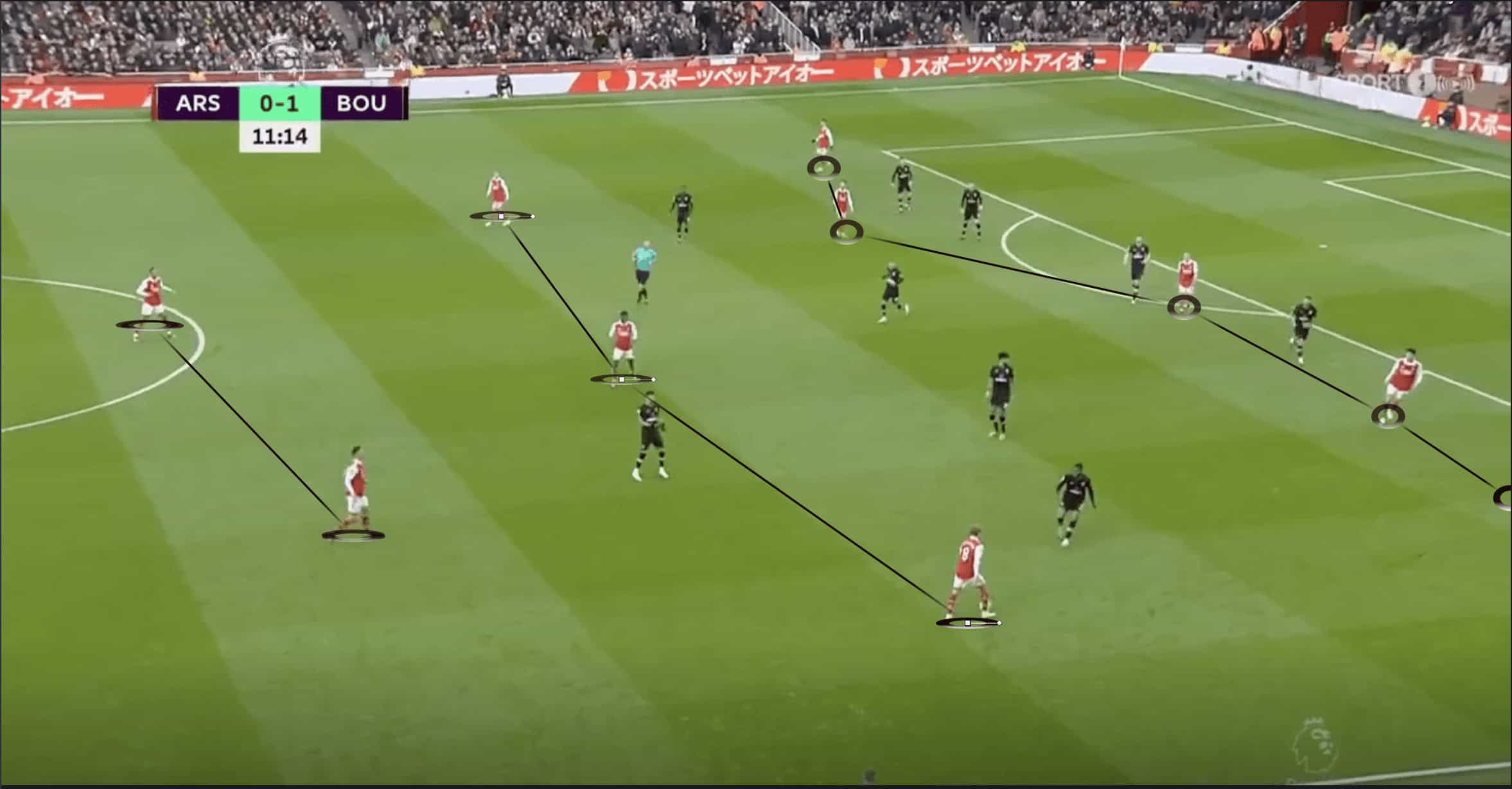

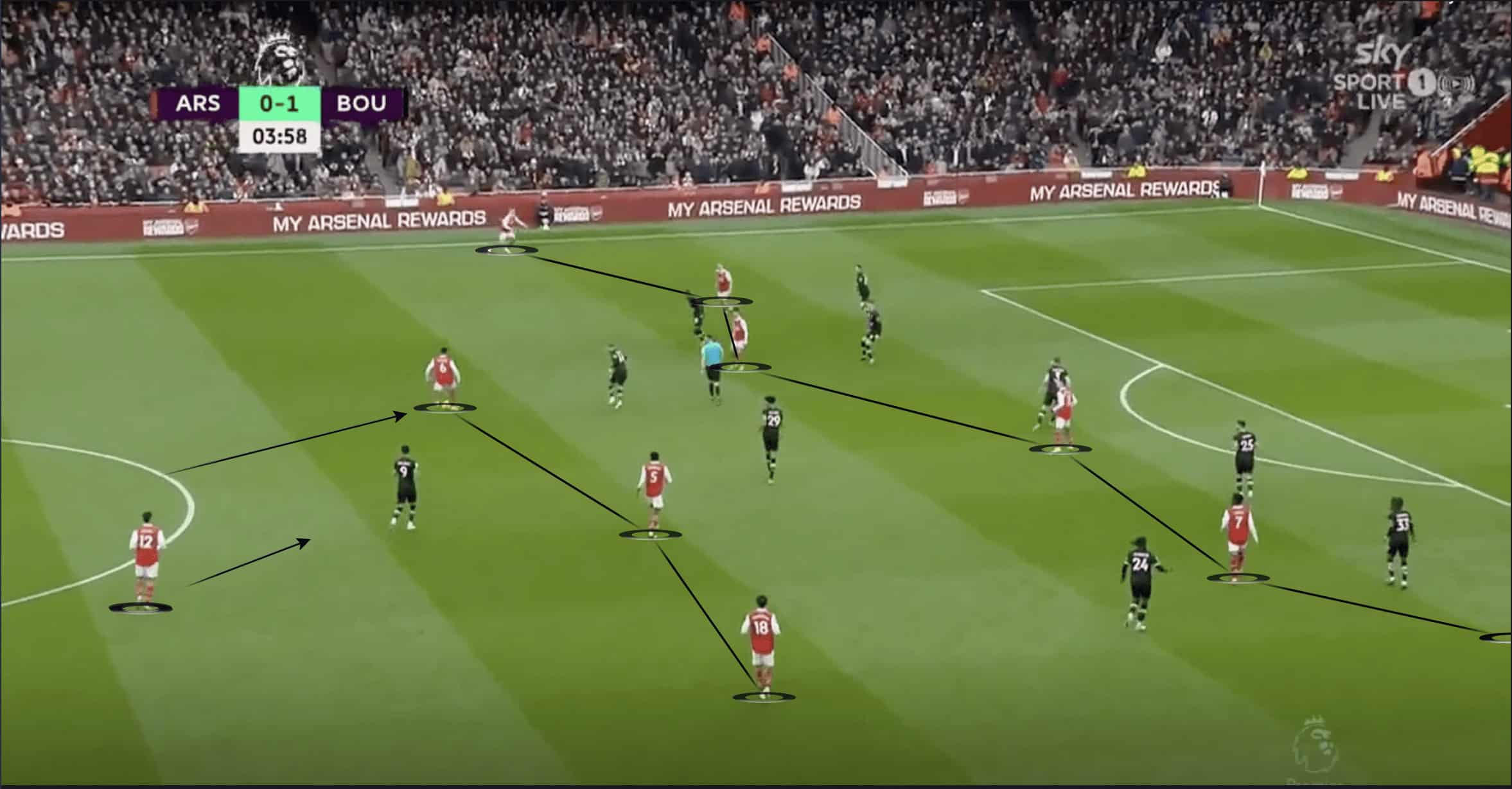

In the image above, Martin Ødegaard and Takehiro Tomiyasu have swapped positions situationally, but the approach stays the same.

The five players in the most advanced line of Arsenal’s structure are not necessarily a part of the rest defence but their role in the defensive transition is still of high significance.

If the ball is lost in advanced areas, the five attackers are the initial counter-pressors in the defensive transition phase, tasked with either winning the ball back outright or, if that does not occur, they aid in delaying an opposition break.

Behind the first line is the second and third line of the 2-3-5 rest defence structure.

The second and third line offer adequate central protection as well as protection of the half-space, with the centre as well as the half-spaces being the most efficient routes to goal for opposition teams when counter-attacking.

In the example below, Oleksandr Zinchenko, as well as Ødegaard’s positioning, would give them close enough access to cover the half-spaces, with both players also in a position to drop back to the full-back spaces if need be.

William Saliba and Gabriel Maghalães’ positioning is in relation to the spaces between the three players in front of them, with the pair still being in close proximity to each other, which allows them to provide cover for one another as well as support and adjust themselves to the actions of the second line.

If the opposition have evaded Arsenal’s first line of pressure, the second line are tasked with looking to press the ball carrier as well as preventing passing options.

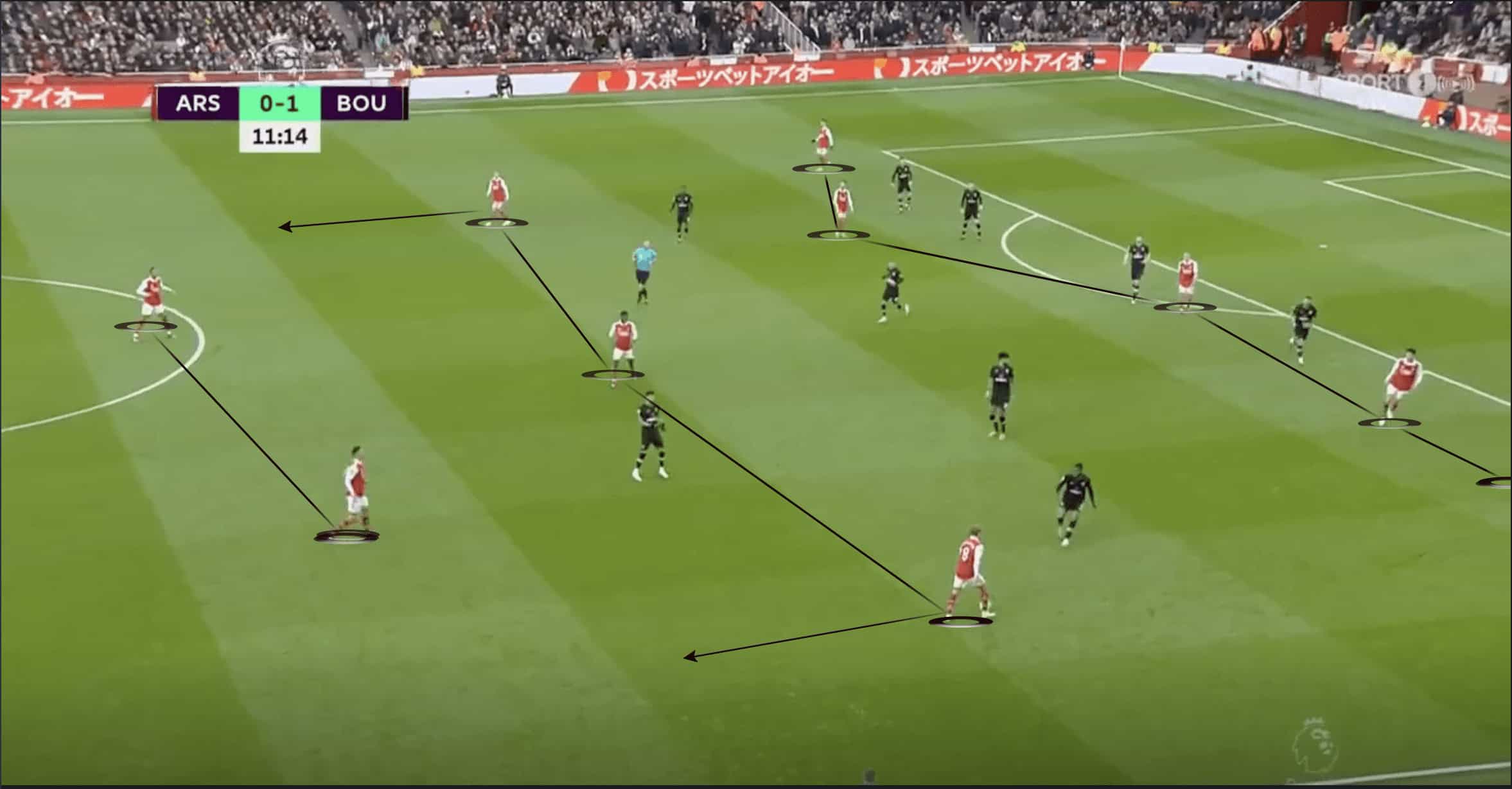

Due to the nature of Arsenal’s structure, it can be described as zonal, as it looks to adjust itself to cover certain spaces rather than adjusting itself mainly to the position of opposition players.

In this scenario below, we can see the rest defence in action as, when the ball is lost, Saliba is able to cover Dominik Solanke in the space between Ødegaard and Thomas Partey whilst Partey applies pressure to Phillip Billing, the ball carrier.

Ødegaard is in a position to cover the run of the player to his right but does struggle somewhat as he does not have the athleticism that the usual right-back options for Arsenal would have in this situation.

Seconds later, as aforementioned, the position of Zinchenko has allowed him to drop back into the defensive line, with Gabriel taking up a position where he can provide cover for the wide area or the centre.

Rotations in possession and their impact on the structure

A large amount of the rotations in possession for Arsenal occur between the five attackers in the team and the two full-backs in the ‘3’ of the 2-3-5 structure.

One of the principles of this Arsenal team is to have one player positioned near or by the touchline, which provides width and can potentially stretch the last line of the opposition.

This, as well as the positioning of a player in the half-space, creates a dilemma for the opposition full-back who has to choose which player to orient his position to, thus creating space for the other.

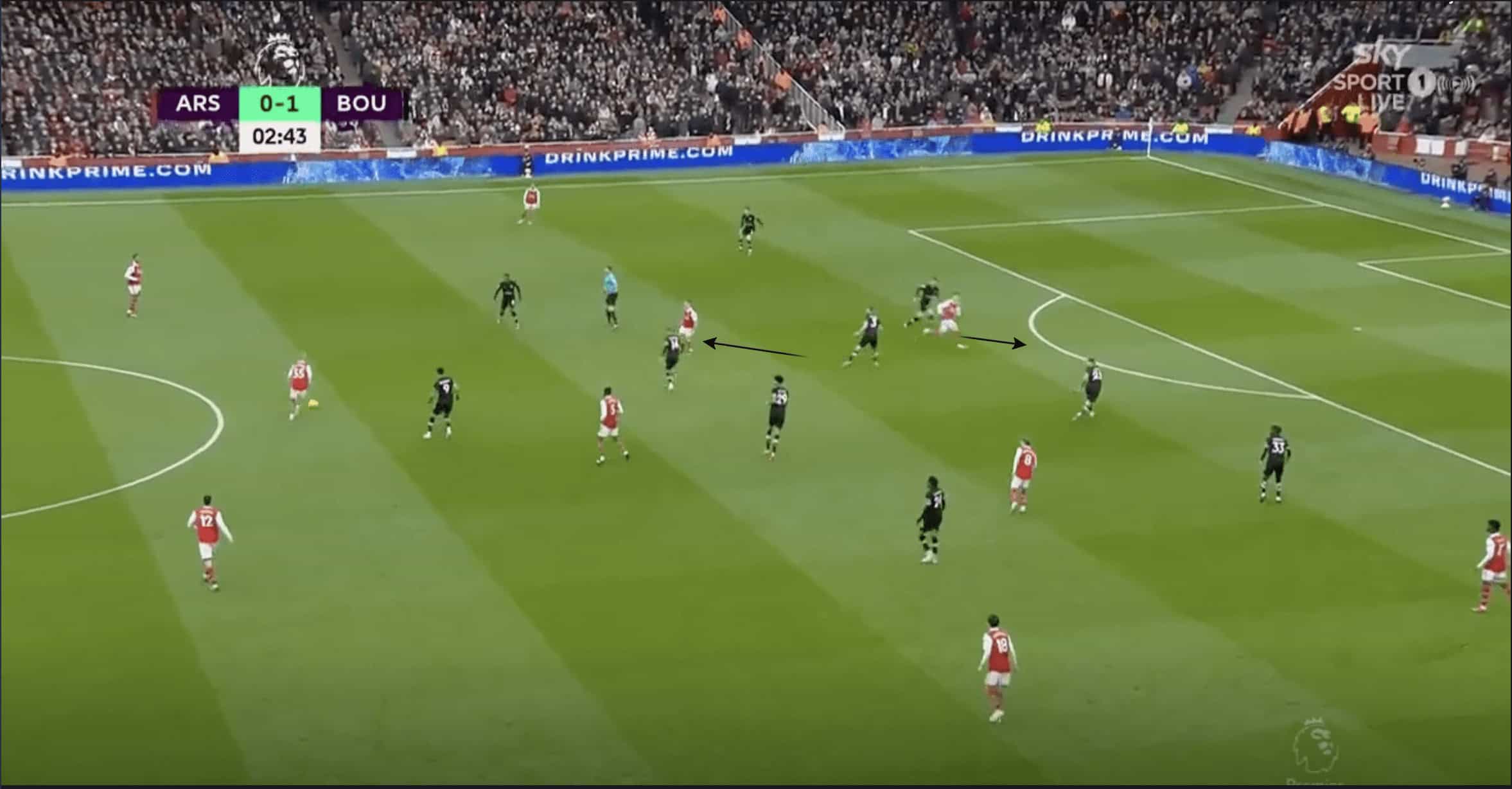

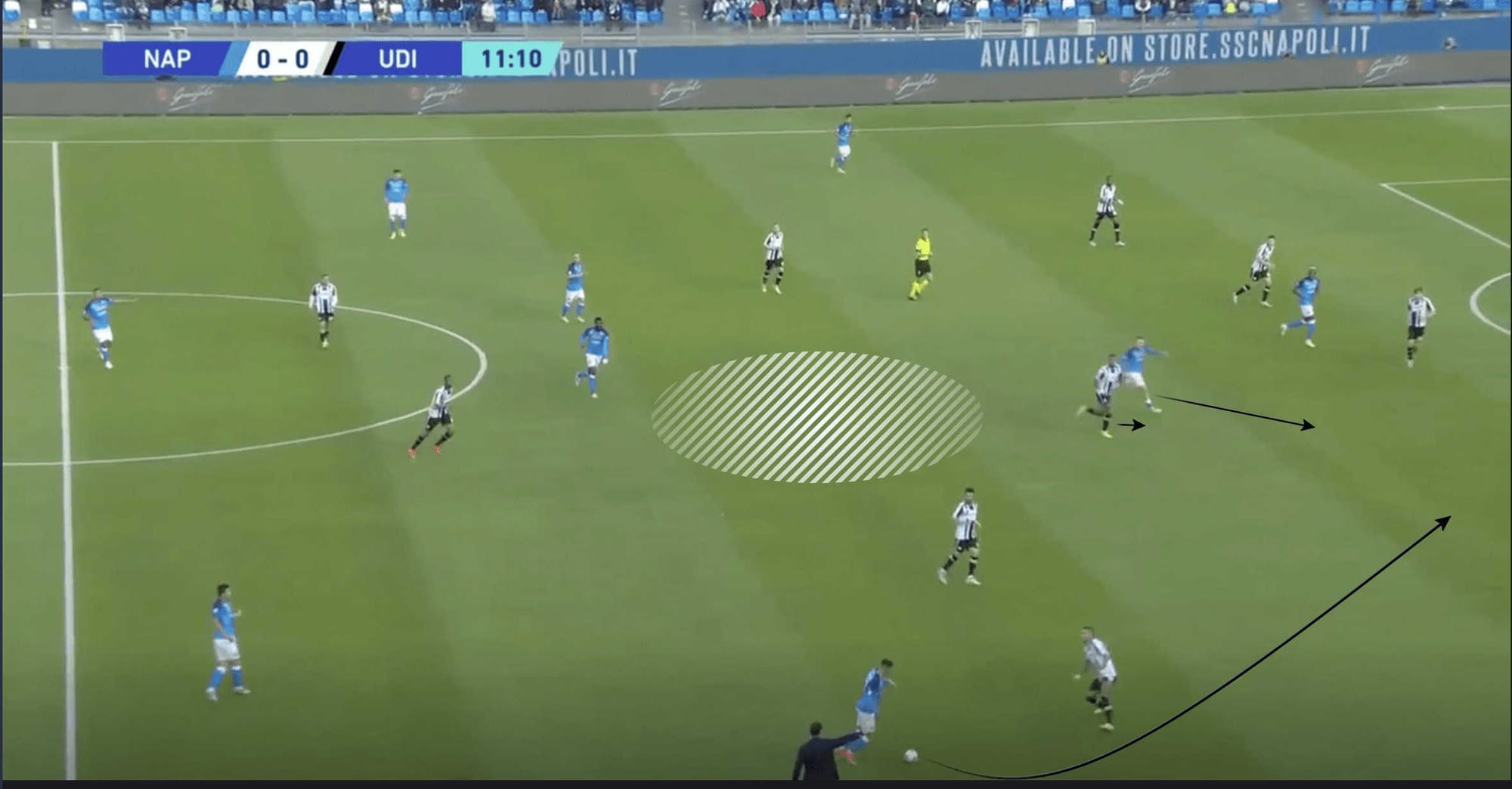

These wide and half-space rotations occur in this example below between Fábio Viera, Leandro Trossard and Gabriel Martinelli.

In the scenario, Trossard begins to drop slightly deeper and pulls the opposition centre back with him.

This acts as a trigger for Martinelli, who has already swapped positions with Vieira, to make a run into a central area.

Moments later, we see Trossard now in the half-space, with the opposition right back’s positioning influenced by Vieira’s positioning on the right-hand side, stretching the last line of the opposition.

Due to the positional rotations taking place between three players in the most advanced line, Arsenal’s 2-3-5 structure is largely preserved, meaning that their approach to controlling defensive spaces is largely the same.

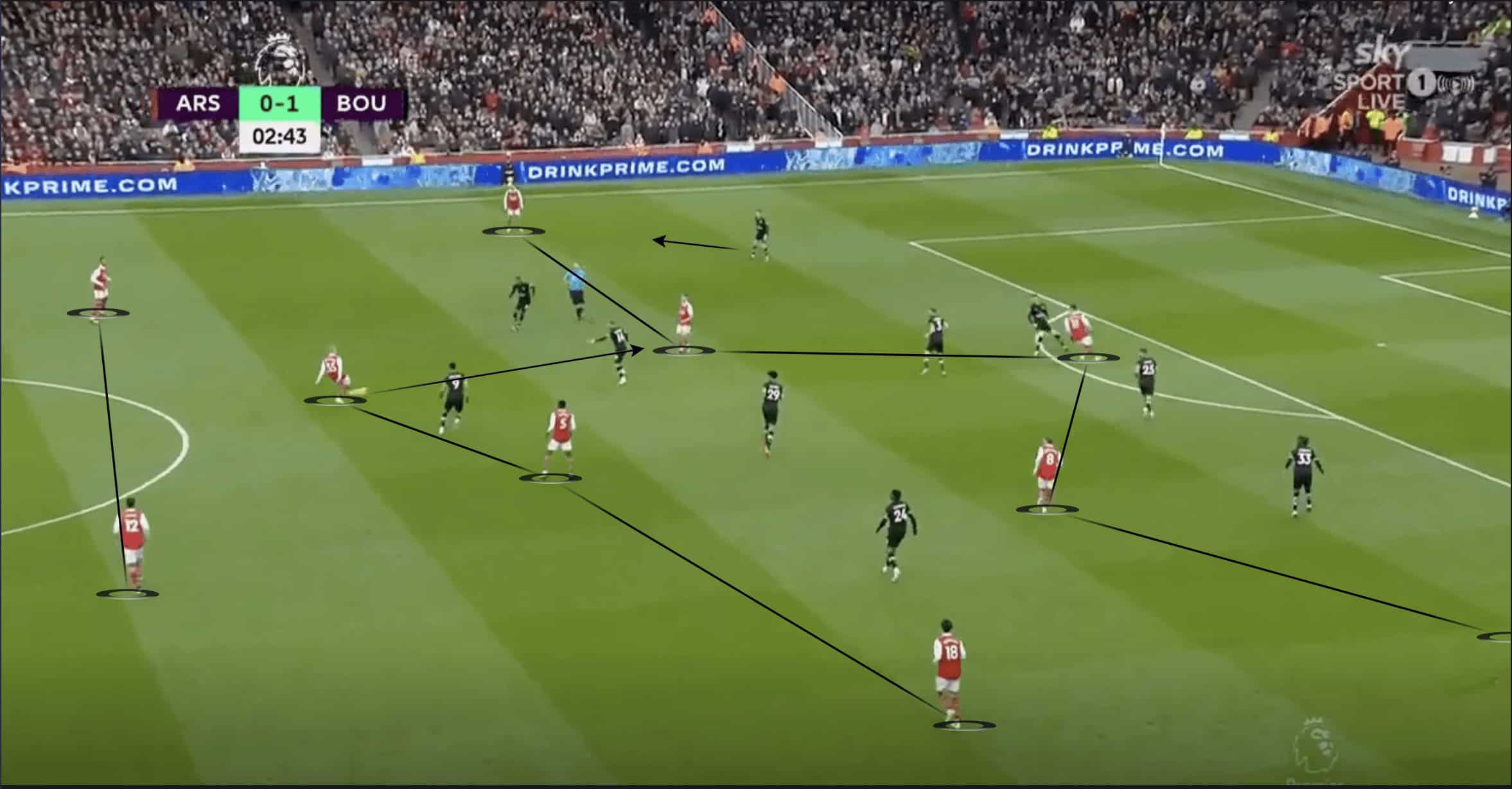

However, in cases where Zinchenko rotates to the touchline to occupy the wide zone, Gabriel advances, with the structure changing to a 1-3-6.

Arsenal still maintain protection of the centre as well as the half-spaces, with Saliba in a position where he can have quick access to the lone striker, Solanke.

Tomiyasu’s position allows him to cover the half space as well as to cover runs behind Saliba if he were to step up and mark Solanke.

The new structure due to the rotation still allows for players in the first two lines to counter-press and the close proximity between the lines indicates the aggression with which Arsenal would look to do so.

With only one player in the last line, the cover that Saliba can provide whilst still being able to pressure Solanke is limited, but due to Bournemouth committing so many players defensively because of their lead, the Arsenal players are in good enough positions to deal with the threat of a counter-attack.

As a result, we can see how the Arsenal structure changes in order to complement the movement of Zinchenko to the wide position, with the shape remaining compact as well as balanced.

Spaletti’s Napoli

Napoli in Serie A are also a team who have made a surprising push towards the title this season, playing scintillating attacking football.

However, where Arsenal rotate and operate leading to the preservation of clear structures, the flexibility to move into spaces that certain players have on the Napoli side leads to less clearly defined structures.

Near the start of the season, Luciano Spaletti was quoted stating that “systems no longer exist in football” and his side look to exploit space.

Although this was interpreted by many to mean that Napoli players did not have any set roles or repeated actions, this is not really the case.

The trend that can be identified in this Napoli side is that different players move into spaces that other players would normally occupy.

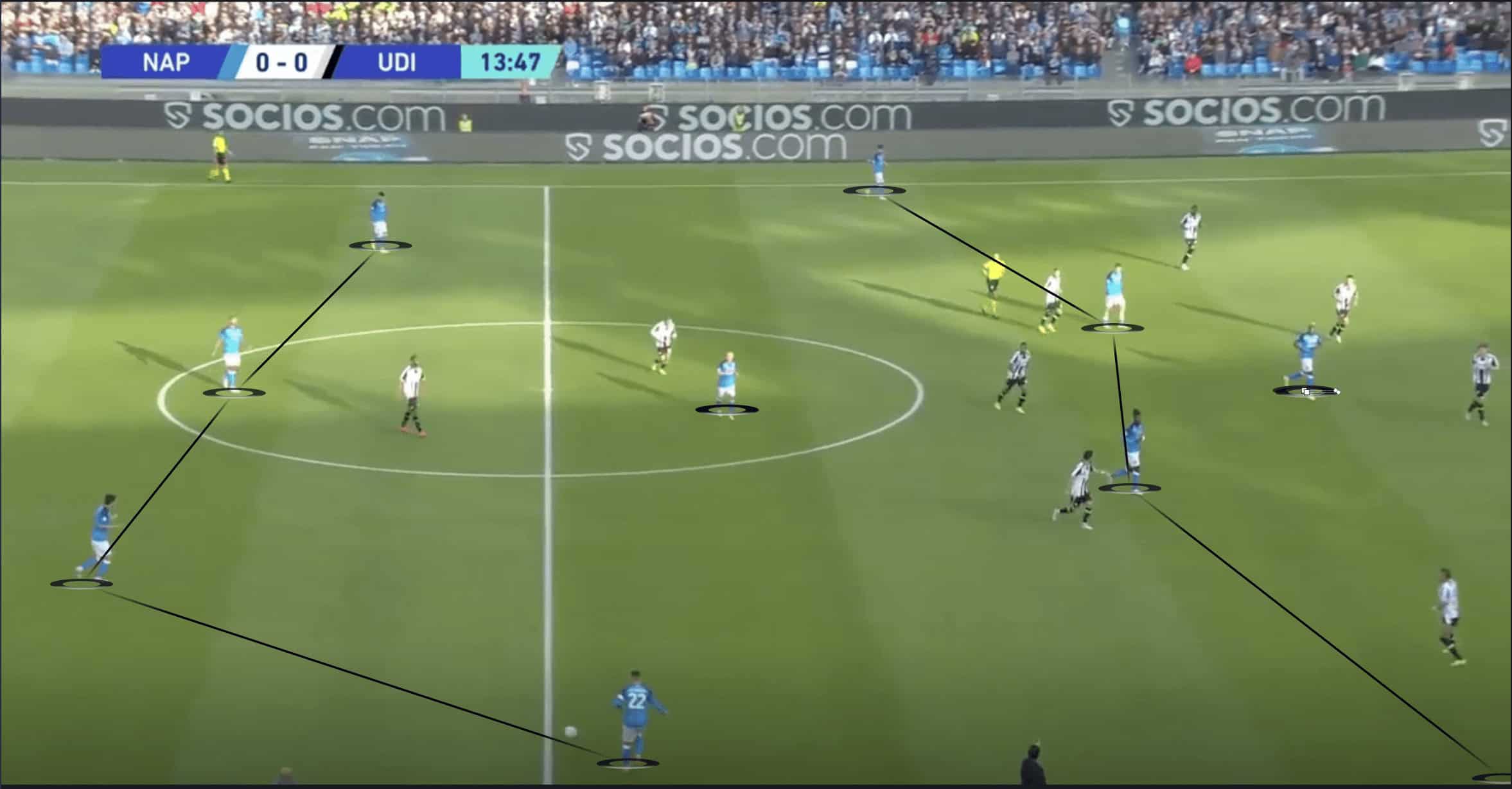

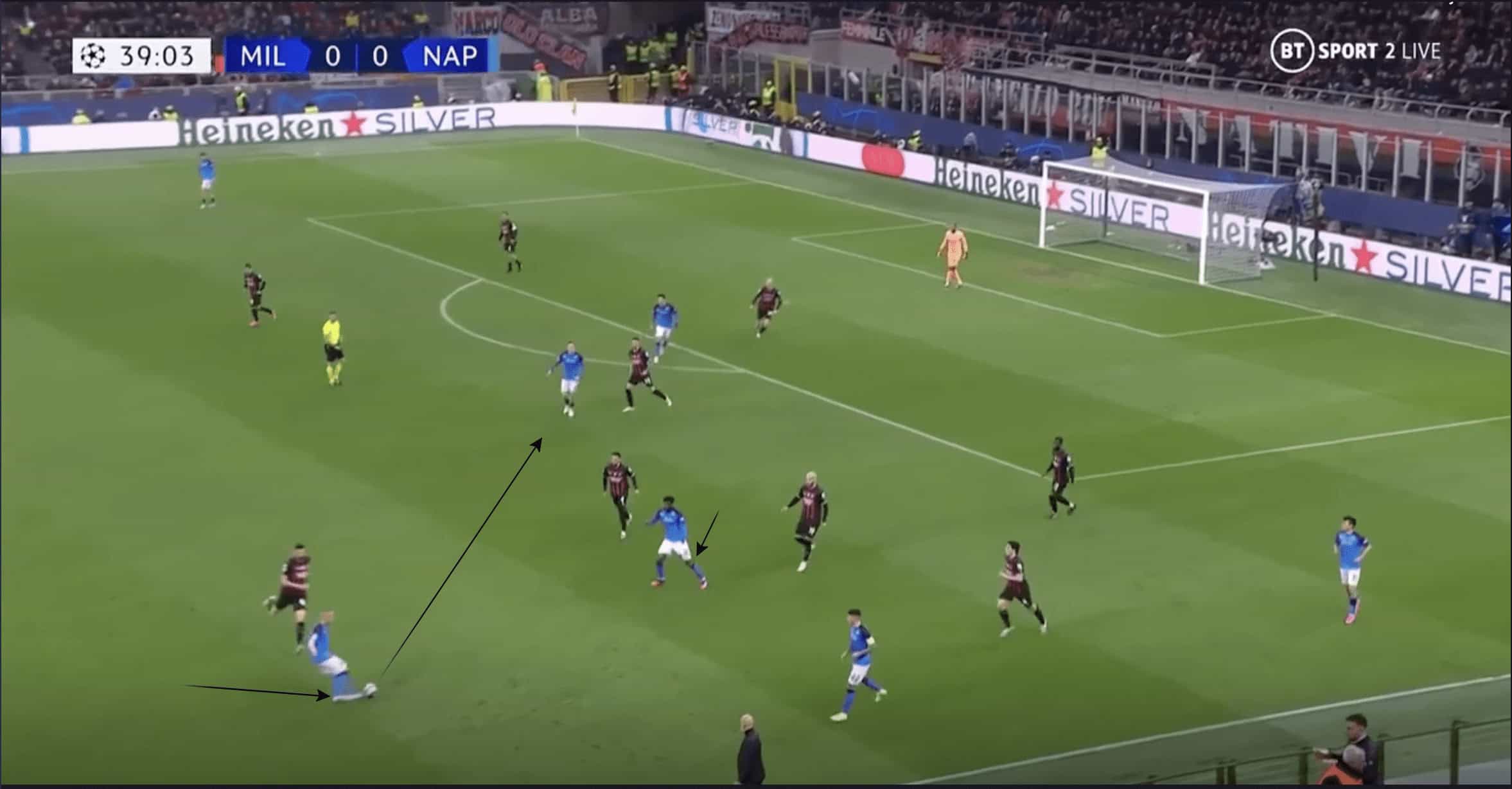

In the image below, Napoli can be seen in a 4-1-4-1 shape with their two midfielders playing as ‘8s’ in more advanced positions, usually occupying the half-space and Stanislav Lobotka as the anchor in midfield.

It must be stressed that Napoli are not wedded to this structure at all.

There are cases where one of the ‘8s’ forms a double pivot with Stanislav Lobotka, which results in the full-back pushing into midfield, occupying the space further up the field that the ‘8’ has moved away from.

What can also be seen in the example below is how André- Frank Zambo Anguissa, one of the ‘8s’, moves towards the ball-near side in order to offer support to the ball carriers.

There are spaces that Napoli try to occupy but, again, they are not wedded to which particular players occupy the space.

Seconds later after the last example, we can see how Anguissa has now dropped, creating a double pivot, but rather than Giovanni Di Lorenzo inverting and pushing into the space that Anguissa would occupy, Zieliński has moved from his previous position into the position that Anguissa vacated.

The understanding that players have for the space around them and their knowledge of the action to execute when in these spaces shows the talent of the players as well as the quality of Spaletti’s coaching.

Ultimately, the effect of the last two previous examples are similar in forcing opposition players into a dilemma over choosing which player to cover.

In the most recent example above, the movement of Zieliński creates space centrally for Anguissa.

But Di Lorenzo does not play this pass as, when players are in the position that Zieliński is currently in, they either look to drop and support the wide players on the ball or look to make runs from the depth and attack the last line of the opposition.

If a player attacks the last line, the player in possession in wide areas looks to directly play a pass to the runner.

It must also be mentioned that, when the ball is in wider areas, Lobotka, the number ‘6’ of the side, may also drift towards the wide areas in order to support play.

Napoli’s rest defence issues

The movement of Napoli’s midfield as well as having great players all capable of manipulating the ball in tight spaces has led to fantastic attacking football.

However, because of this.

Napoli are vulnerable in their defensive transition phase.

This was particularly the case in their Champions League clash against Milan.

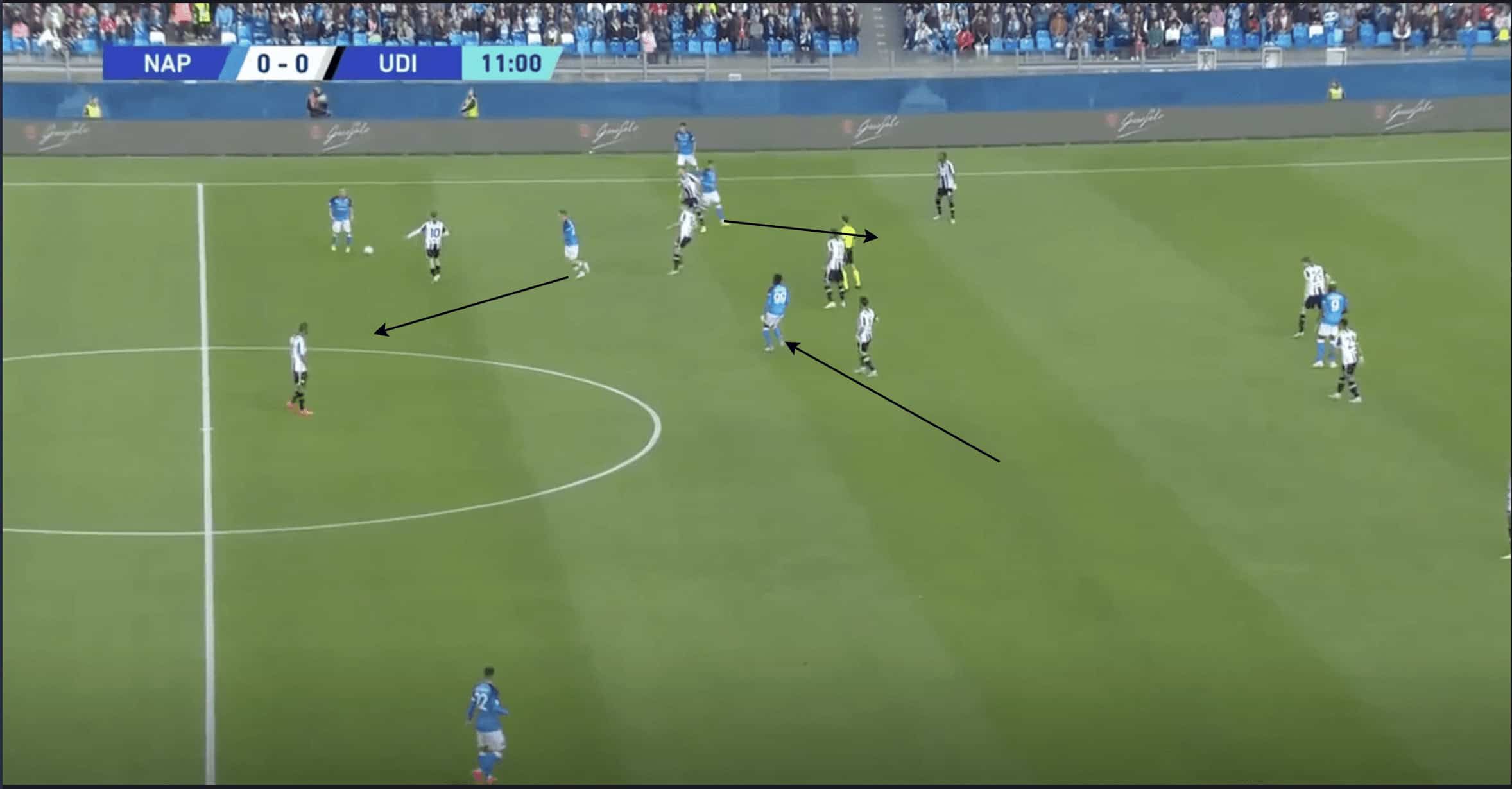

In the example below, Lobotka has pushed further up the field with Anguissa dropping down into the single pivot position and Zieliński shifting towards the right ‘8’ position.

Di Lorenzo inverted slightly and Mario Rui advanced on the touchline.

Lobotka would then play the ball out wide to Rui and move wide to support him.

However, seconds later, when Napoli lose the ball, due to the movements of Lobotka and Zieliński as well as Di Lorenzo, they are not in a compact structure to apply pressure on the ball, with players having to cover relatively larger distances in order to do so.

Because of this, the centre of the field is also rather exposed and Milan could find Rafael Leão, a player extremely difficult to stop when in full stride.

Milan’s first goal in the tie came from one of the patterns of movement aforementioned in this piece.

Anguissa, the right number ‘8’, as well as Lobotka, support play out wide, with Zieliñski, the left-sided ‘8’ also drifting towards the right-hand side similarly to the movements of Anguissa in the Udinese game earlier.

However, after the ball is played centrally and is then lost, Lobotka has to shuttle across in order to cover space in the centre, with Brahim Díaz free to receive a pass.

Mario Rui also shifts from the left-back position in order to apply pressure to Díaz but Spaniard is exceptional in tight spaces and the two Napoli players have had to cover a large distance in order to press him.

Milan would then have a 5v3 and score the first and only goal of the game.

The goal conceded in the second leg came as a result of Tanguy Ndombele dropping deeper, forming a double-pivot in midfield.

Di Lorenzo would then begin to advance into the right half-space.

But a mistake from Ndombele meant that Leão could take hold of the ball and once again stride forward.

The commitment of many players in advanced positions, as well as there being no noticeable adjustments to compensate for players moving into these advanced areas, results in Napoli having little control of key defensive spaces in transition.

The movements we have discussed are not every facet of Napoli’s attacking play but are merely some aspects that leave them vulnerable in transition.

When viewing these movements in the light of rest defence, Napoli at times are not in control of defensive spaces around them, with players having to cover large distances in order to pressure the ball.

With the centre, half-spaces and wings not being adequately occupied all the time, Napoli are particularly susceptible to conceding opportunities from counterattacks.

Conclusion

Player movement and rotations do not always have a negative effect on a side’s rest defence, with everything dependent on the balance teams look to have.

Teams may be slightly less potent in possession in order to preserve a compact structure that aids them in defensive transition.

However, football is not an exact science, and while the approach of Napoli has noticeable frailties, they find themselves clear at the top of Serie A, with their approach seeming to look to maximise their attack and accepting the consequences this might have on their ability to defend in transition.

In addition to this, it is not only enough to always look to maintain a certain structure that protects important defensive spaces like Arsenal.

Players need to be trained to be coordinated in their efforts in trying to win the ball and to know when they should counter-press, when it would be better to fall back and how to move in relation to the actions of their teammates.

Comments