FC Koln have become one of the stronger teams in the Bundesliga following the appointment of Steffen Baumgart in 2021. In his first season in charge of Koln, he helped them climb up to a seventh-place finish in the league, earning them a Europa Conference League spot. Halfway into the season now, Koln are sat in the middle of the league table, although they are in danger of potentially falling into the relegation zone.

Koln have both one of the leakiest defences, but also an effective attack, which has allowed them to score more goals than every team in the league, outside of the ones competing in the UEFA Champions League or UEFA Europa League.

Part of what makes their attack so strong is their use of corner kicks, where they have accumulated 5.57 xG, more than any other team in the Bundesliga. Koln have had 91 corners this season, and while it is a figure near the top end of the league, their xG total, which they have amassed from 40 attempts, means that they create a higher xG per shot value over any other team, meaning the quality of shots created is high, although their corners aren’t always the most accurate, with them only making the first contact 44% of the time.

In this tactical analysis, we will delve into the tactics used by FC Koln when they are attacking corners, with an analysis of how they have created so many high-quality chances from them. This set-piece analysis will look at the different methods they’ve used when attacking corners and how they have been effective for them.

Use of ‘Anchors’

The biggest reason why FC Koln have been able to create so many high xG opportunities is down to a method which can be called ‘Anchoring’. This is the result when an attacking player plants himself in between the goal and the defender, almost like a screen, but creating space for himself rather than a teammate. This action is usually done just as the kick is about to be taken so that there is no time for the defender to get back in the correct position.

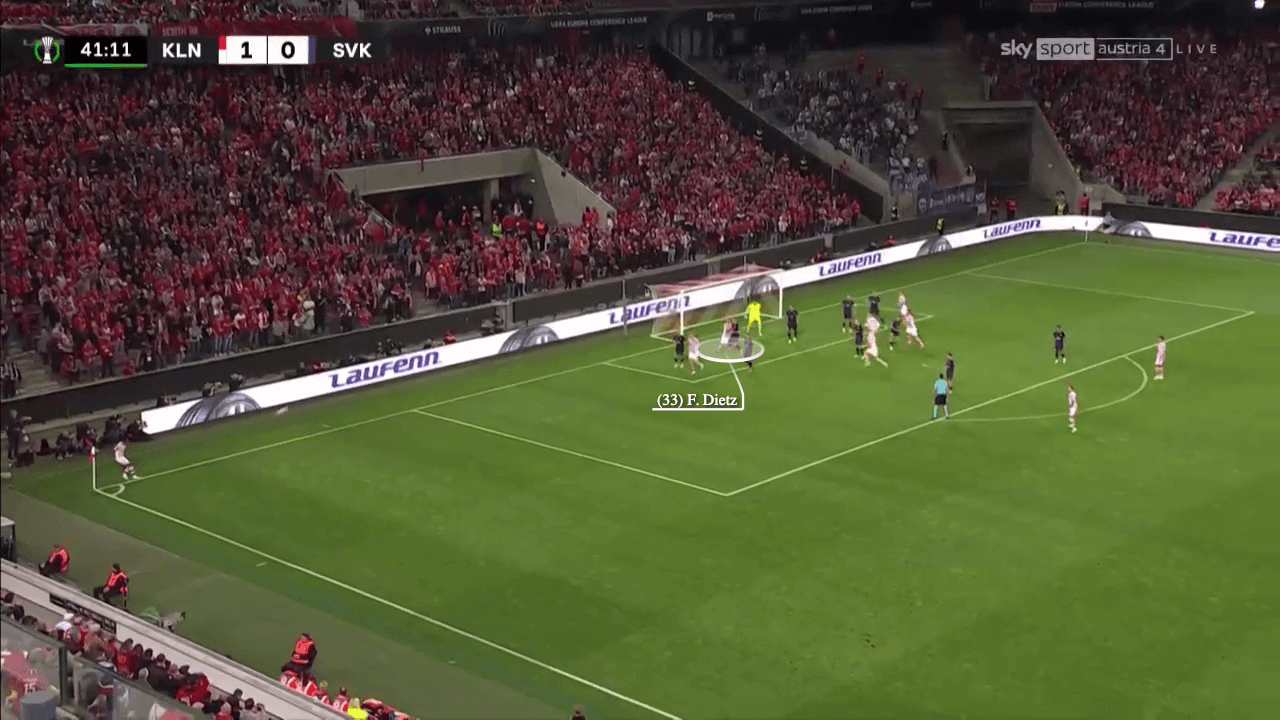

When a player ‘anchors’, they create a clear opening between themself and the goal, meaning that should a cross be played into them, the attacker will have a clear shot on goal from their position. This image below shows Dietz positioning himself between the goal and the defender, with him only having arrived there after the kick was taken.

It’s important to note that this sort of routine only works when the corner is delivered with precise accuracy. The corner must come over the zonal marker at the front of the six-yard box and instantly drop towards the player’s head. In addition, if the delivery is played too far from the goal, it may be cleared by a defender, whilst the corner can’t be played too close to the goal, as the attacker’s bodyweight is leaning away from the goal, blocking the defender.

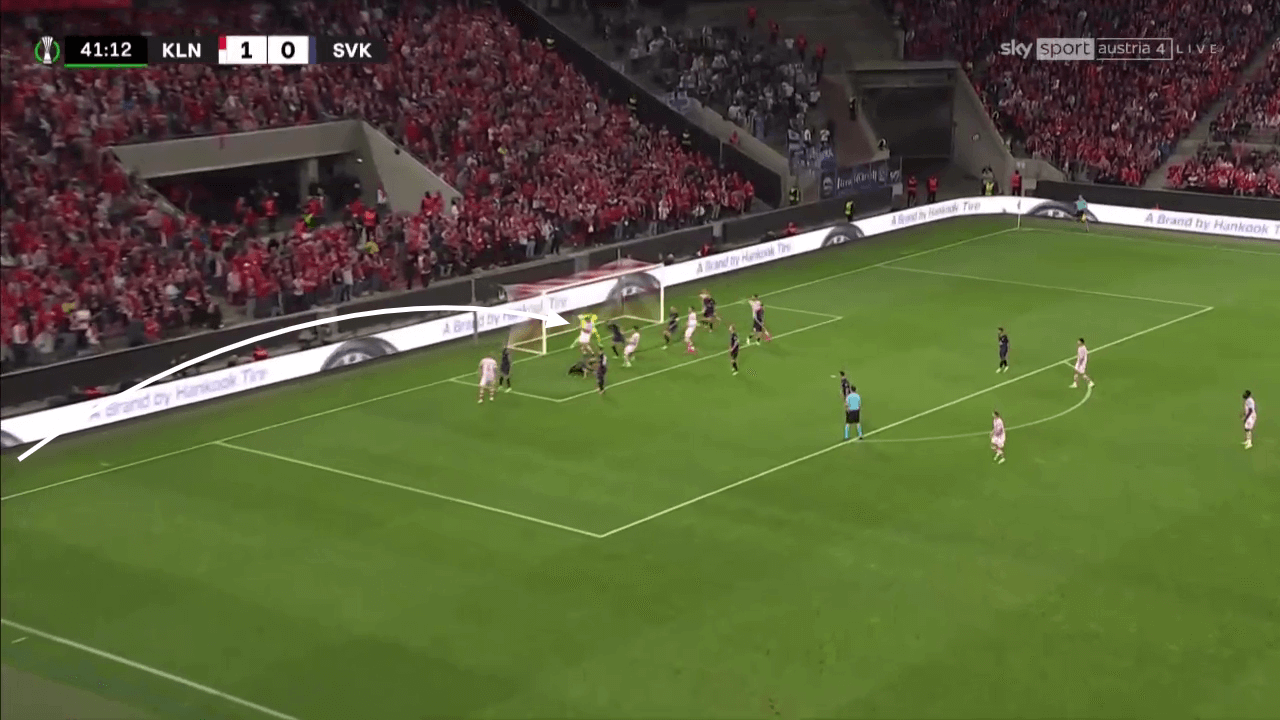

An attacker may not have the time to adjust his body to attack the ball should it be played away from him. The attacker is like a beacon, an immovable object which stands firm, and gives the player a strong body core, from where he can drive the header into the back of the net accurately, like in the instance below.

There is also a variation to the anchor where rather than positioning yourself between a defender and a goal, the player moves between the ball and the defender. Anchoring is marker-oriented, whilst having the option to be ball side or goal side of the defender. When a player anchors ball side, it makes for an easier option for the corner taker as the horizontal direction of the kick is less relevant.

Should the ball be played goal side of the attacker, he will have the option to shoot at goal. However, the corner has security in the sense that if the kick goes to the opposite side of the anchor, he can still connect with the ball ahead of his marker. From these positions, where a corner is less accurate, rather than going for goal, an anchor can flick the ball into a more dangerous area at the back post. This is only the backup option as the shot on goal will always be prioritised when the ball is inside the six-yard box with no one there to block it.

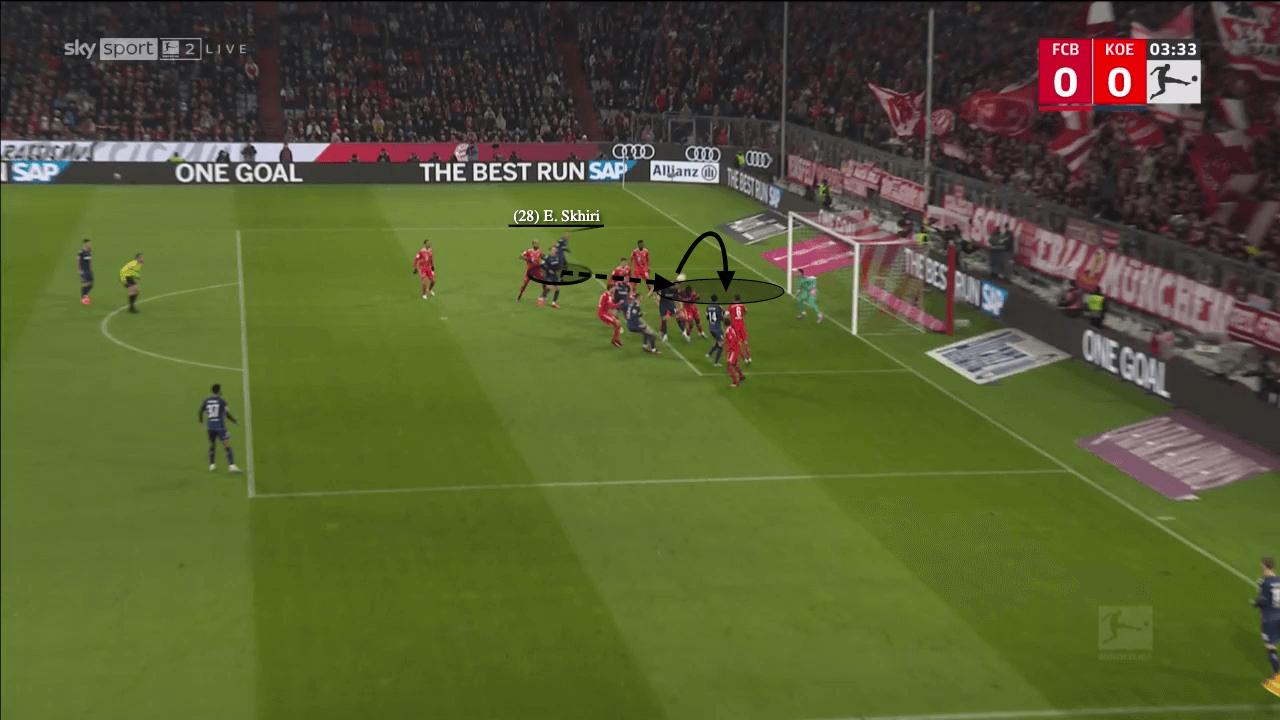

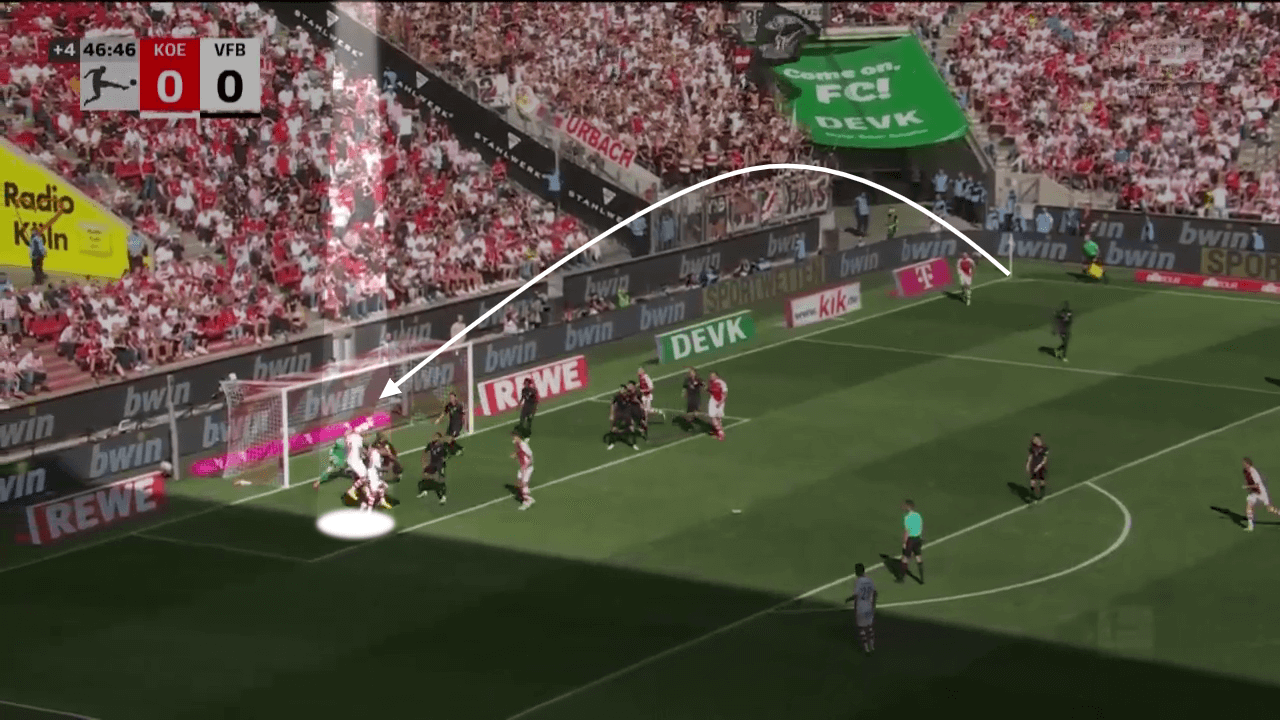

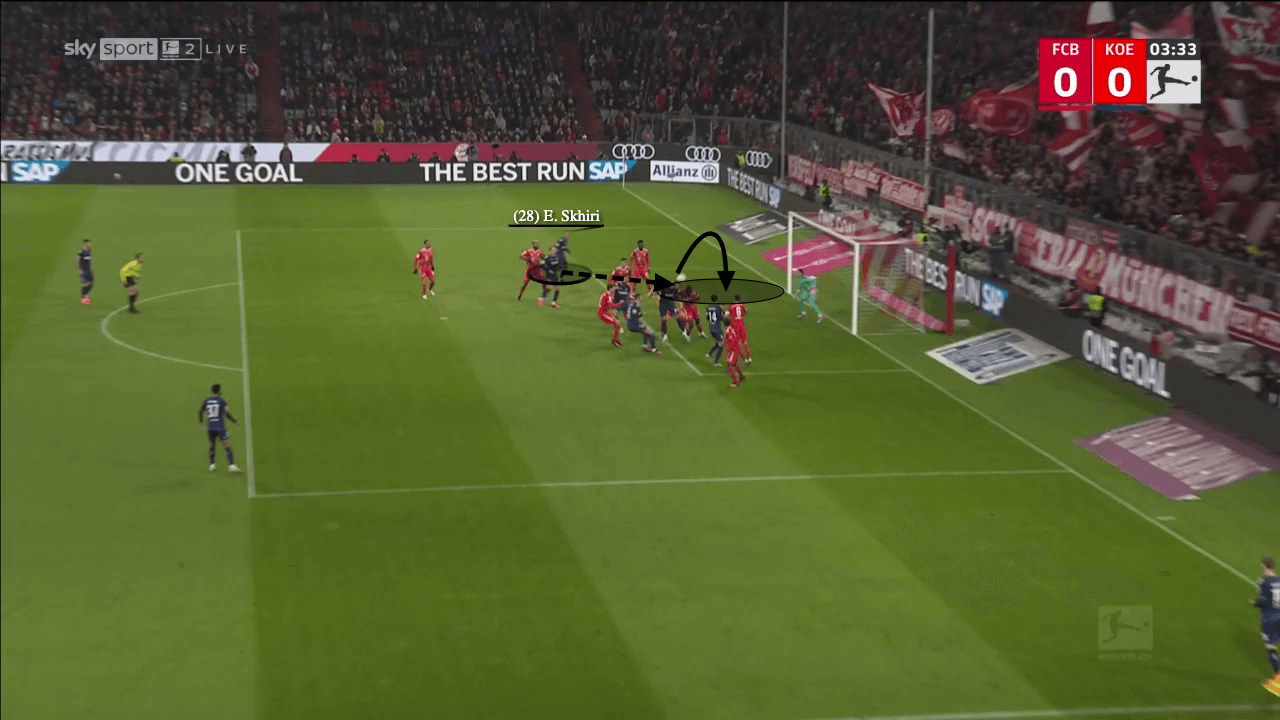

We can see from the image below, that once the flick-on occurs, a run has to be made towards the back post, to finish off the routine. A deep run from Skhiri is difficult to defend as he has the running momentum to get to the ball before a static defender. Furthermore, with the ball being flicked on, it arrives in an even easier position, with the ball closer to goal and the attacker unmarked, although running at speed can make it hard to perfectly time the action. However, when timed correctly, it results in a very easy situation for the runner from deep.

Alternative Routines

Whilst ‘Anchoring’ has given FC Koln the biggest share of their high-quality chances, Die Geißböcke have been able to come up with many alternate routines to make them unpredictable from such scenarios. One method which can be highly effective is the use of screens. Previously we have described how players have used screens for themselves, to create space closer to goal, however, the Koln players also utilise screens unselfishly to create space for teammates in areas which may be more accessible and easier to hit for the corner taker.

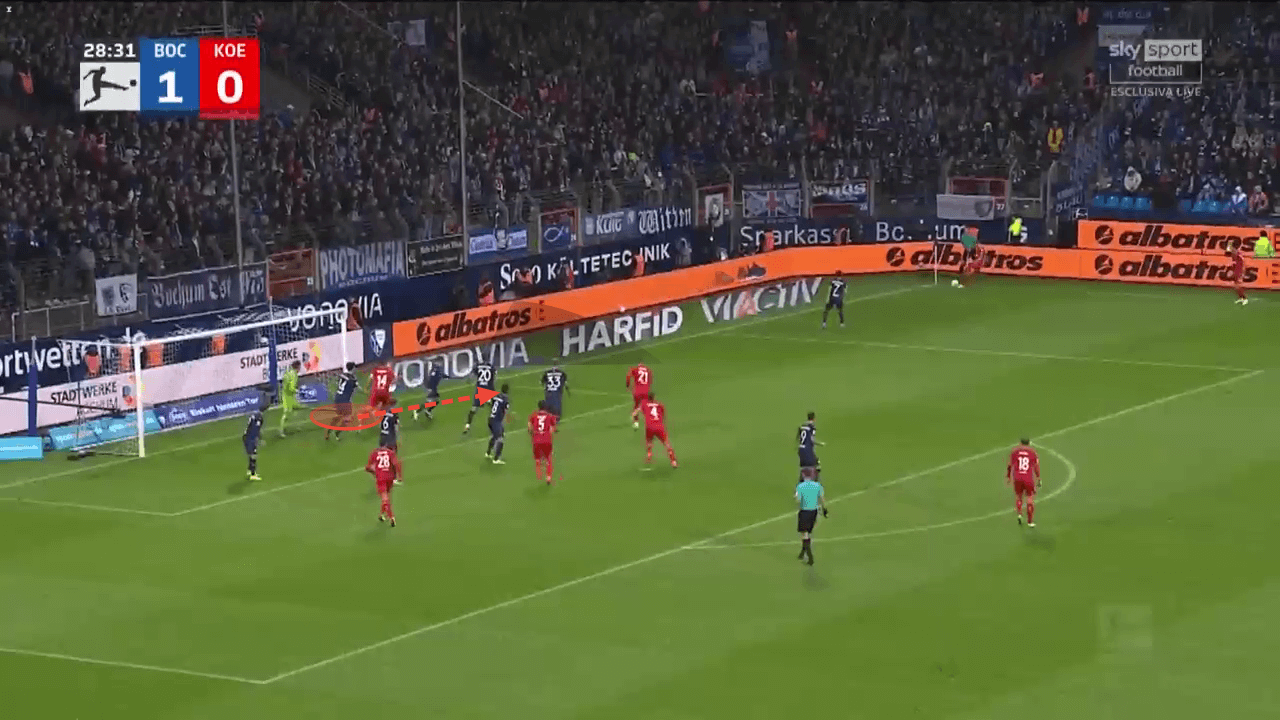

We can see in the still image below, a screen (white) being set up just in front of the six-yard box. The lane from the corner to the target area (black) is completely clear, meaning that the corner has a relatively high chance of making it to its target, as long as the horizontal placement of the cross is accurate.

Whilst the screen is vital in this scenario, another part which is needed to make this routine work, is the dynamic movements of each attacker around the penalty spot. All four players around the spot rotate and cross paths with each other, making it hard for man markers to stick close to their assigned attacker. This allows the target player to have the separation needed to sprint away from his marker into the target area where he can attack the ball without any opposition pressure.

If both components of this routine are successful, the attacker will have an unopposed header from six yards away, which just has to be kept on target in order to go in the back of the net, like in the instance below, to put Koln 2-1 up ahead against Borussia Dortmund.

Another routine utilised is the run from inside the goal to attack the ball. This run is difficult to be tracked, as no player will follow an attacker into the goal, and when the attacker makes his move, he is on the blind side of the defenders, who are completely unaware he is coming. As a corner comes into the front post, defenders are under the false impression that they have an easy ball to clear, which makes their movements more relaxed and slower than if there was a player present. However, in the last moment, the attacker comes in from the blindside and can attack the ball just in front of the defender, who may be on his back foot.

This method can lead to chances created in dangerous areas, however, a negative is that with the attacker moving away from the goal, it can be hard to redirect the headed effort back on goal. The angle of the run-up means that attackers can’t run onto the ball, and instead have to redirect it by angling their heads. This is difficult, and in a lot of cases like the one pictured below, the ball will usually be flicked on just past the back post. It is vital that during this routine, a player is always attacking the back post to get onto the end of any loose balls or flick-ons.

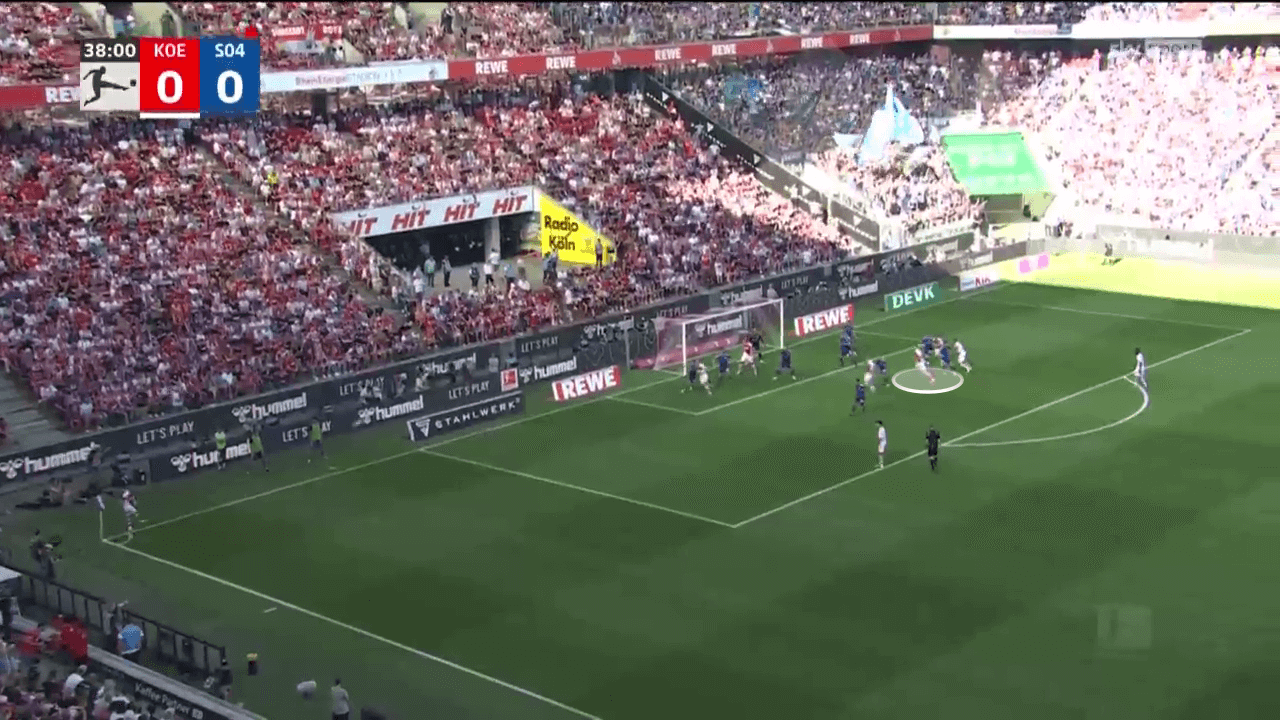

FC Koln have also been smart to identify any potential underloads in defence and target them. When teams have used smaller numbers of man markers, Koln have shown the adaptability to adjust their starting positions to make the most of those scenarios. We can see in the instance below, Schalke have three man-markers, so Koln make sure to have four runners from deep attacking the ball. This means that one player will be able to have an unmarked run at goal, which will allow them to use that momentum to out-jump any zonal markers.

We can see this in effect, as the Koln player attacks the corner delivered towards the middle of the six-yard line, from where they can use the sprint start to out-jump static defenders. This isn’t something that is always possible due to the fact most teams use as many man markers as needed, but the red card for Schalke made this a possibility.

One final method Koln have utilised is their focus on attacking the back post on different occasions. A deep cross to the back post is hard for defenders to deal with, due to the fact it is impossible for defenders to keep their eyes on both the attackers and the ball. When a cross is aimed towards the back post, a defender has a choice to make. Either they focus on tracking the defender, which can result in them losing the flight of the ball, or they can keep their eyes on the ball, but as a result, they can’t see where the attacker is. Losing track of the attacker means that they can adjust their run and jump earlier than usual, so that they jump over the defender, preventing them from being able to get up off the floor.

Defending back post crosses is extremely difficult for defenders, and when the delivery is perfect and an attacker has the jumping reach like in the image below, there is not much any defender can do apart from jumping early, which can be hard to time. Crosses like this can usually be claimed by the goalkeeper, but identifying a goalie who is hesitant with crosses and using this method can be extremely effective against them.

Summary

This tactical analysis has displayed how FC Koln have created more chances from corners than any other team in the league. From the use of anchors to the different directions corners have been aimed towards, Koln have shown that preparation for corners can be vital to winning crucial points, which this season could be important to avoid a scrap for relegation.

The recent point earned against Bayern Munich shows just how important corners are, with Koln scoring in the opening minutes through a corner kick, in a game where chances were rare against the German giants.

Comments