Marginal gains within any sport are vital for success and one of the most recent trends in football has been the increased emphasis placed on throw-ins. Once, if a team was said to emphasise throw ins you would expect long-throw routines into the box, but more and more in modern football you are seeing teams train, and then use throw-ins as a vital tool to regain and maintain possession. If a team can structure themselves correctly defensively from a throw, they can potentially regain possession and prevent a potentially dangerous attack, while on the flip side if you maintain possession correctly you can build a dangerous attack, or create a dangerous situation directly from a throw.

Set-pieces are usually trained in terms of routines, and throw-in routines are still used by teams, but not as prevalently as corners and free kicks. This is due to the sheer number of throw-ins and the therefore different variables such as pitch location and number of players that are possible, and so like anything in football, players need to be trained in the principles of a throw-in situation in order to be effective. This tactical analysis will outline four practices that can be done to coach these principles, and analyse some top teams offensive movement from throws.

Coaching points

All of the below practices should include each of these principles and coaching points, with some points more emphasised throughout the analysis than others depending on the session. Below is a list of these broad coaching points that can come about through the practices.

-Decoy runs

-Rotations

-Double movements

-Vacation and occupation of space

-Third man runs

-Arriving into space

Here we can see some examples of these points being put into practice.

In this example here, Wolves create a 5 v 4 around the ball. Jordan Henderson makes a decoy run in order to draw his marker out from a passing lane. Mohamed Salah also provides height which pins Wolves’ backline deeper.

Roberto Firmino moves from deep and behind a potential marker, obviously meaning he cannot be seen by this player, and then arrives into the space created by Henderson. Firmino arrives and receives the ball immediately, which doesn’t give the opposition an opportunity to react and also offers better body orientation. Liverpool then go on to score thanks to the combination play of Salah and Firmino.

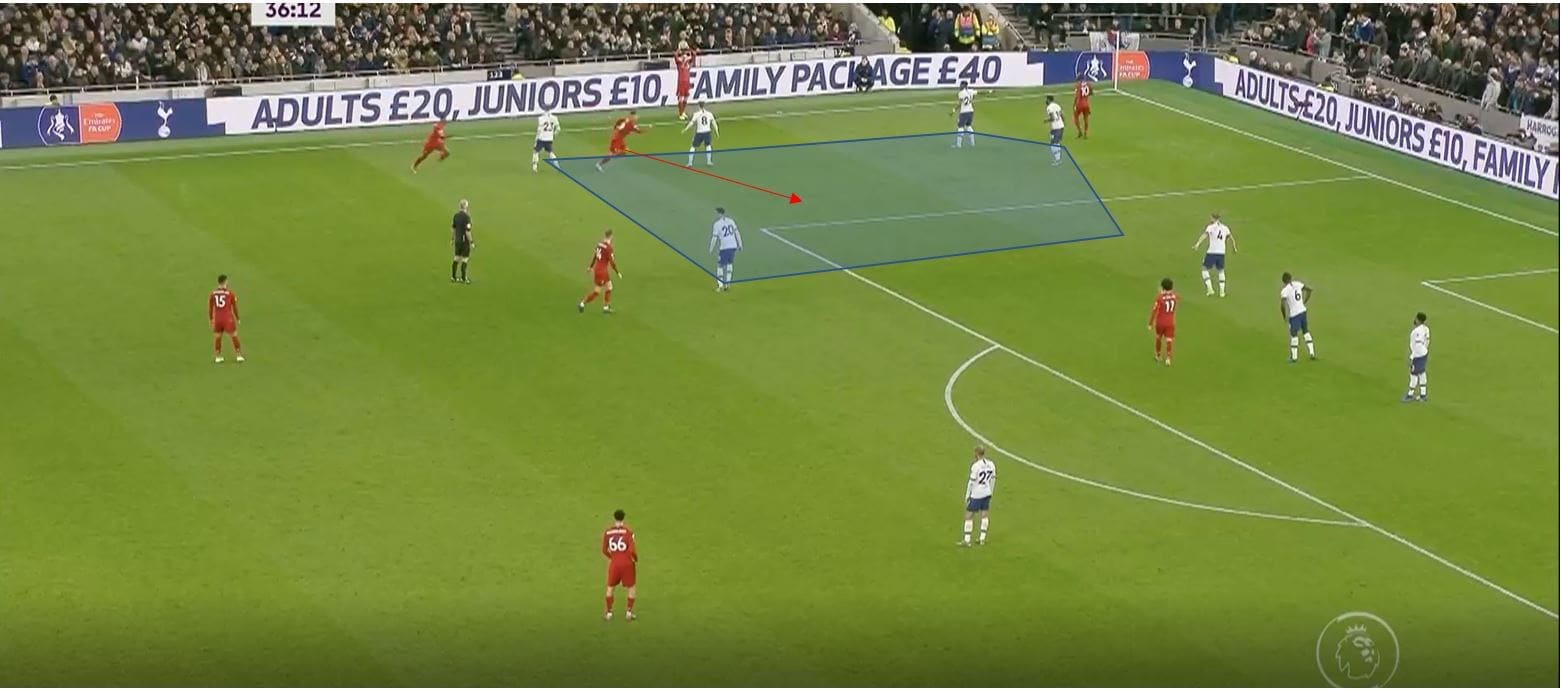

We can see another example from Liverpool here, with throw-ins being a clearly practised part of their tactics. Tottenham surround the ball-near area and make it a compact space. Roberto Firmino moves closer to the ball carrier and takes his marker with him. This movement of course leaves more space in behind his marker.

But the space still isn’t that large, and if the ball was to be thrown behind Firmino, the centre-back may be able to step out and clear. Therefore, Sadio Mané moves into a wide area and drags his marker with him.

Therefore, as we can see below, this space has now been increased drastically, and Firmino has a free run into the half-space, something we will touch on later. Firmino has vacated a space and with a double movement reoccupies it, with his body language key here also, in order to not look as though he may burst back into his space.

Practice one

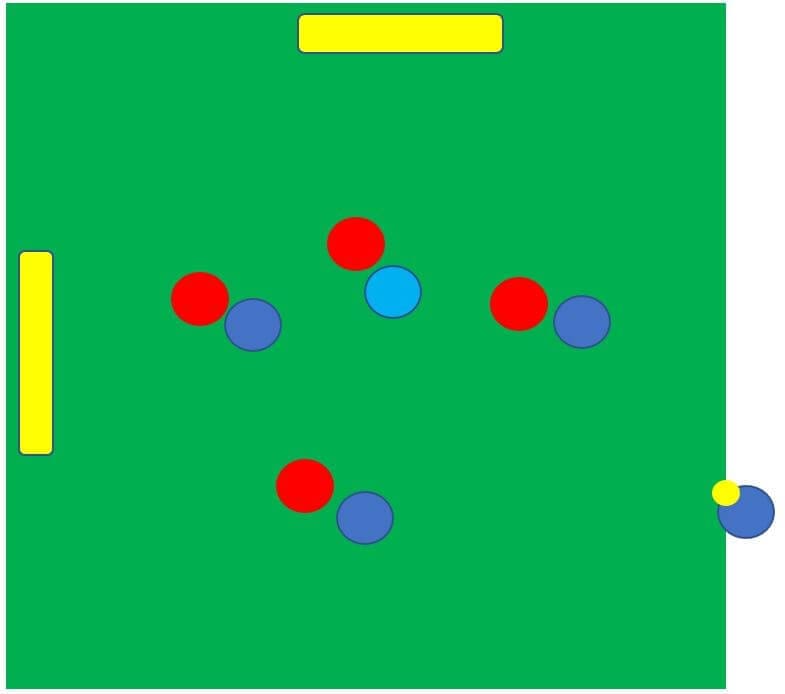

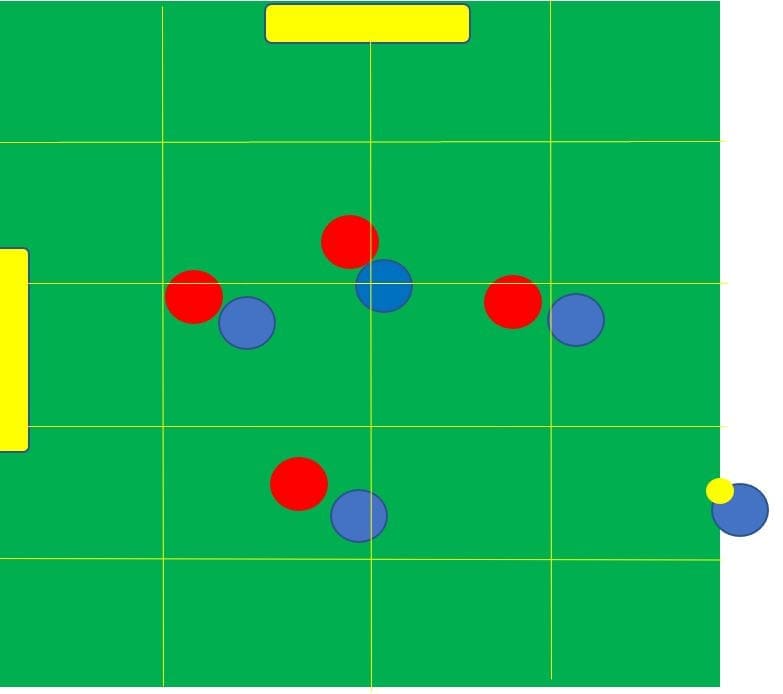

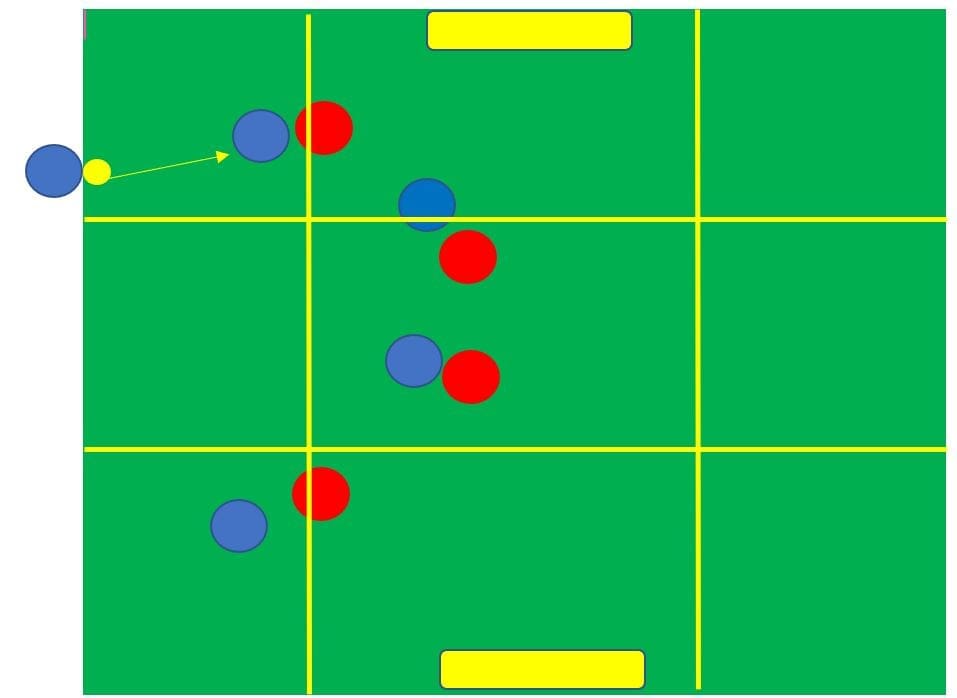

My first practice revolves around finding a target player. In the previous examples, we’ve seen the target player to be Roberto Firmino, and that the players around him make space for him to receive. In this practice, the attacking team is given a target player in private (away from defenders), and for a goal to count the ball has to be received by this player. Play starts from a throw and goals can be scored through either of the gates seen, vertical goals or horizontal goals.

In a match related environment, this horizontal goal represents a switch in play or a more central access, while the vertical goal represents penetration (particularly of the half-space) and movement towards goal. As a result, while the horizontal option is an option, we will prioritise penetration, and this is reflected within the scoring system. If the attackers get the ball through the horizontal option goal they get one goal, and if they get it through the vertical option goal they get three.

Within this coaching practice, all of the coaching points can be delivered but there is a particular emphasis on decoy runs to open space for the target player, and less of an emphasis on rotations which come in later.

Rotations and occupation of space

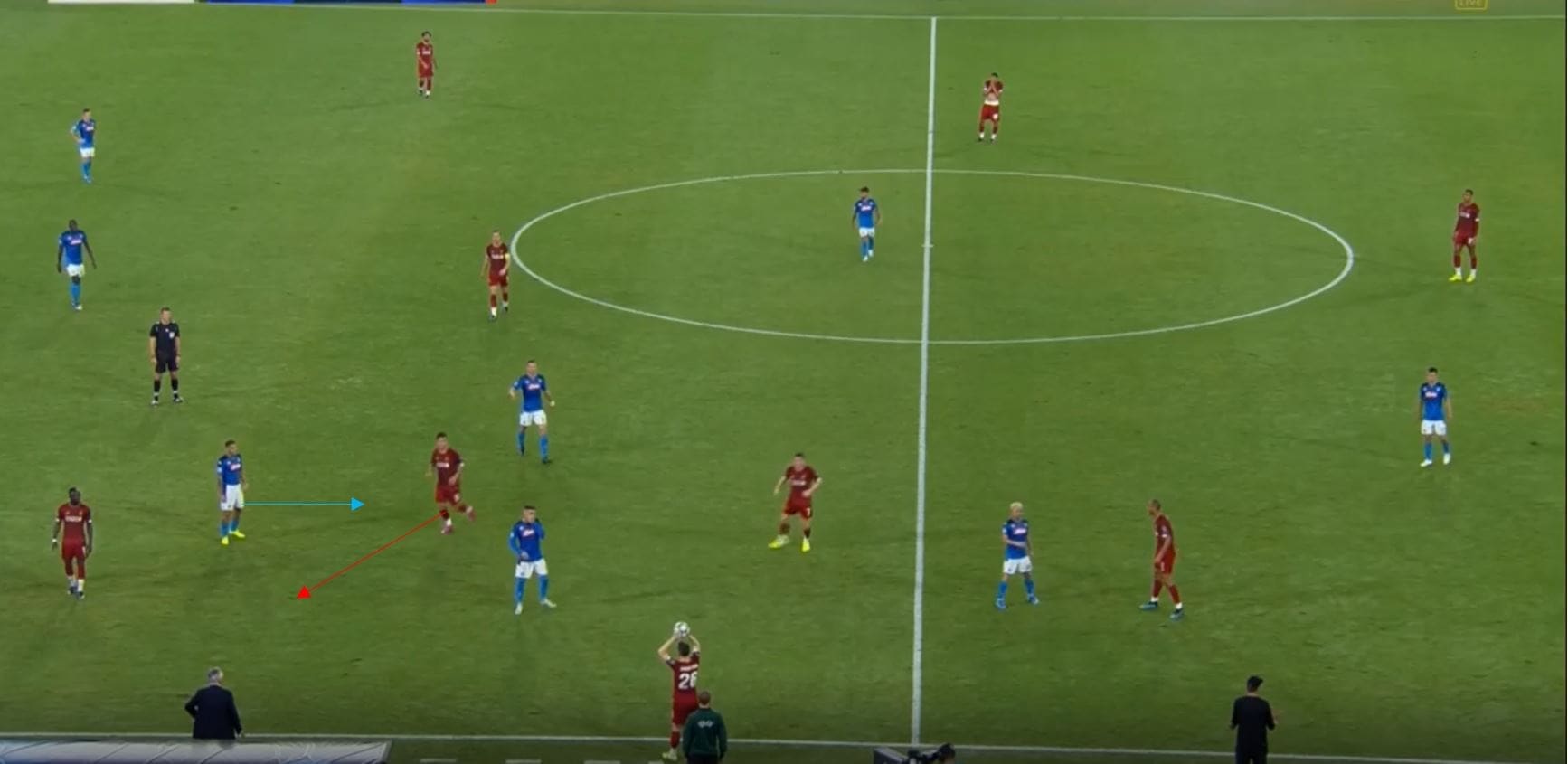

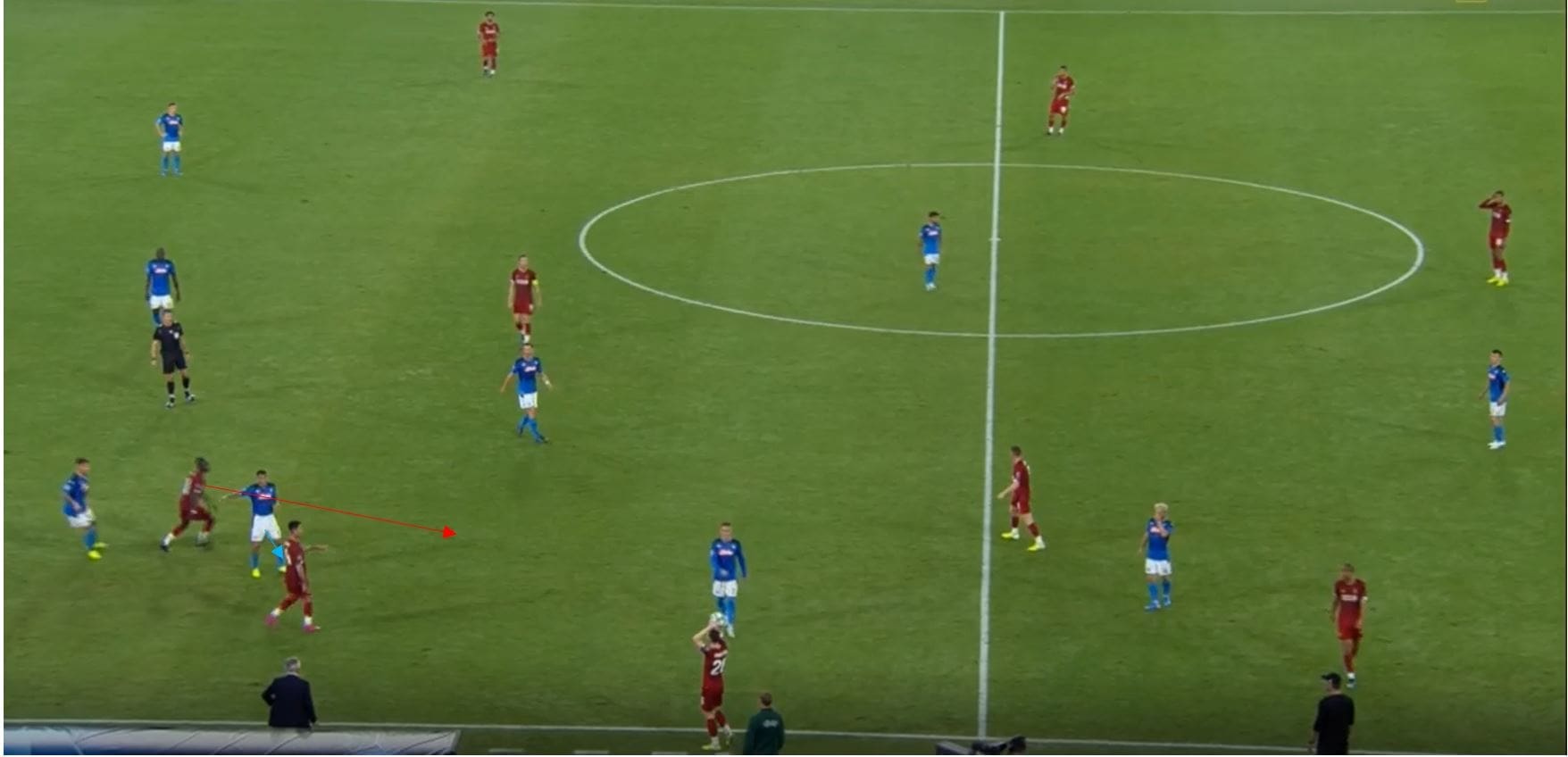

Rotations are a vital way in which we can create space from throw-ins. By rotations, I mean exchanging positions or spaces with another player. Here Firmino makes a movement from his more central position into the wide area and the space which is occupied by Mané.

Allan, Firmino’s marker follows him, and Mané rotates to then occupy the space previously held by Firmino. Mané’s marker won’t follow him to this deeper area and Allan can’t react to this movement made from behind him. The lanes to switch the play or play to the centre backs are then open and Liverpool can escape pressure and build an attack.

We can see an example here from Tottenham, where a movement is made by Dele Alli into the wide-area while another player occupies a more central space.

This central player then makes a movement into the wide areas as well, and Son then occupies the space left by this player, while Alli carries on his run to complete a third man run. Though this is more of an occupation of space rather than a rotation, as players don’t swap positions strictly, this is still a good useful example.

Practice two

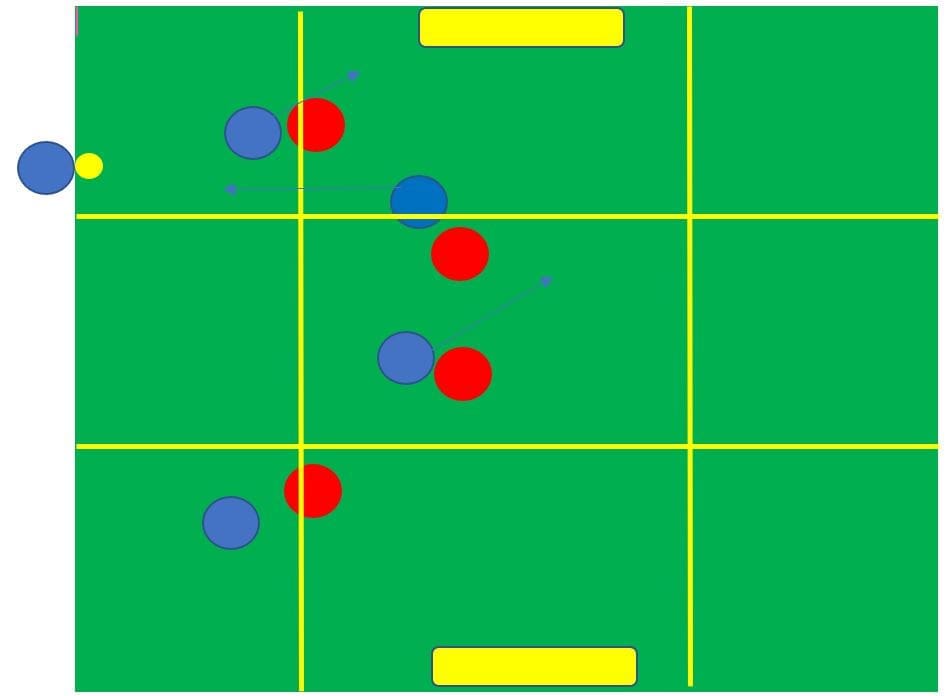

Our second practice involves an emphasis on rotations, while still covering the other points mentioned. The pitch is separated into grids and only one player from each grid can occupy one area at a time. To begin with, this can be unopposed with teams simply throwing the ball to amongst each other while following some simple guidance from the coach. Within these grids, you can set the rule of players can only receive in a square their teammates has just occupied, which forces players to rotate with their teammates, and use their awareness to find which teammate to rotate with.

You can introduce a rule which enhances spacing in that you cannot be within one square vertically of a teammate, and can also say that players cannot receive in the same zone that they are in when the pass is played, i.e. they must arrive into the space. All of these rules can be applied separately or at once in a handball type game to keep the practice more constant, or can be done where play starts from a throw-in and goes dead after a certain period of time, resetting play back to the thrower.

It is vital however in these quite fixed practices, that we change the situation slightly to make it more variable, and so play shouldn’t start from the same point all the time, otherwise, players get limited experiences. Numbers within all these practices can be adjusted also in order to under or overload the attacking side.

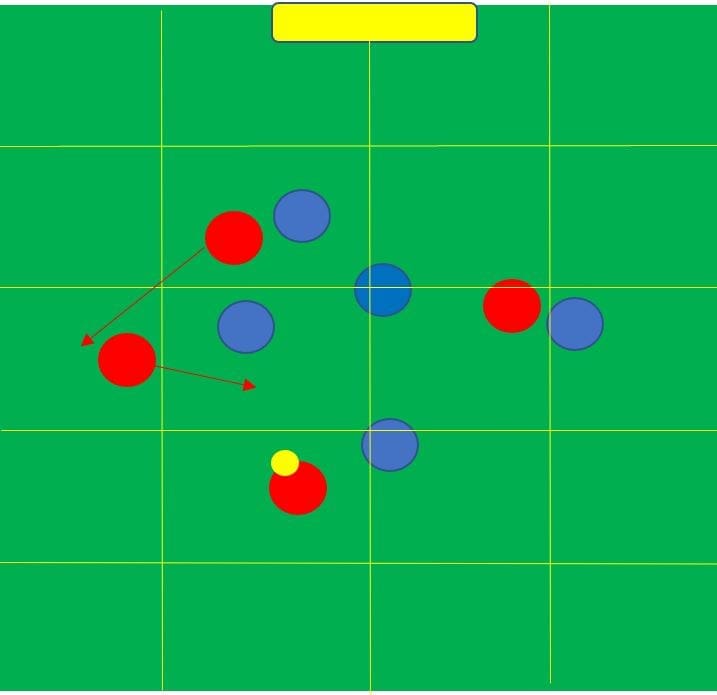

Below is an example of a situation which may occur, with only the vertical goal included in an open play game, with a red occupying a space and another player moving in to receive in this space. Another red player should then look to occupy this previous space. This then very much resembles Basketball if the hands are used, and there are several concepts in this area which link with Basketball well, and may be another idea for a piece for me.

Practice three

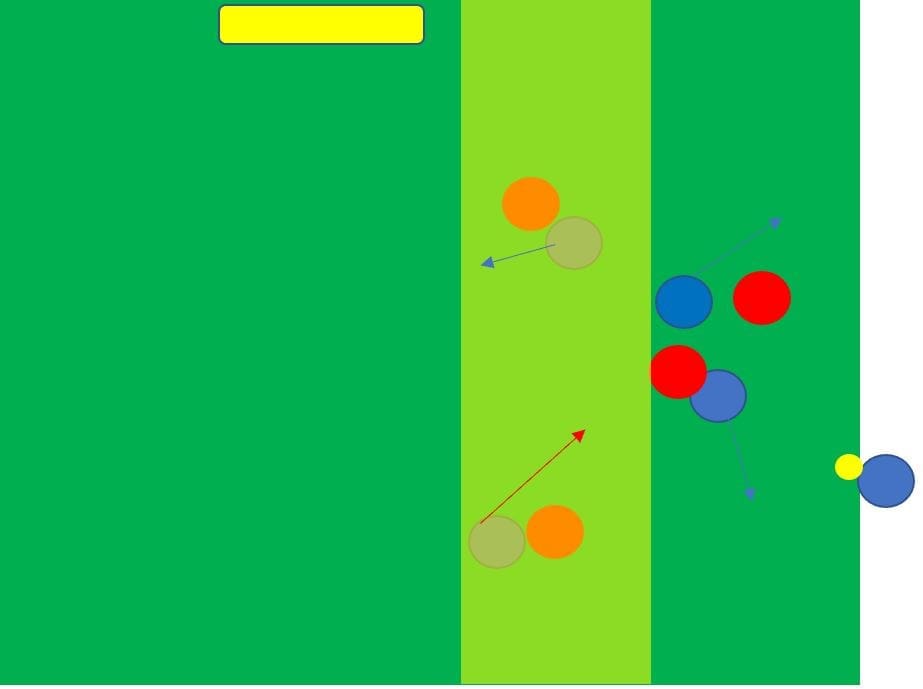

The aim of this practice is to look at how the team can penetrate the half-space quickly and therefore access the centre. The pitch design now replicates a throw-in situation well, and so players should be better able to apply the practice in a game. The rules are simple in terms of just attempting to score a goal, but the scoring system again gives affordances to the players and looks to shape players behaviour.

Teams are given three goals if they can score after their first pass is into the half-space and gain one goal for any other goal. If this proves too difficult, it can be adjusted so the half-space has to be accessed within 2 passes. The size of the pitch will mean that the half-space will need to be used and can’t be thrown over unless a very long throw takes place.

We can see an example here of a scenario which may unfold, with rotations and decoy movements used in order to create space for a player, all of which ties back into previous practices.

The splitting movement from the two ball-near players in the image above creates space through the middle, allowing direct access to the half-space where a player who arrives into this space on time can receive the ball. A double movement or other similar movements can be coached with this player to help them lose their marker if needed.

Ajax examples

Some examples from Ajax help to illustrate some of these coaching points well, and the common theme between themselves and Liverpool is the employment of throw-in coach Thomas Gronnemark. This example below is a good example of the double movements which we discussed.

The target player moves away from the thrower with his back to him, vacating the ball near space and using his body language to disengage his marker slightly.

He then quickly turns and moves back into the space he once vacated, and his marker is unable to follow. Simple, but effective.

We can see an example here of Ajax using the movement of players to open up passing lanes for teammates. Here, the opposition are in a decent shape to defend the throw-in with an overload in the ball-near area. One of the deeper Ajax players then makes a run towards the thrower, dragging his marker with him.

This opens the passing (or rather, throwing) lane into a centre-back in a deep area, and although Ajax don’t progress in a dangerous area, they retain possession.

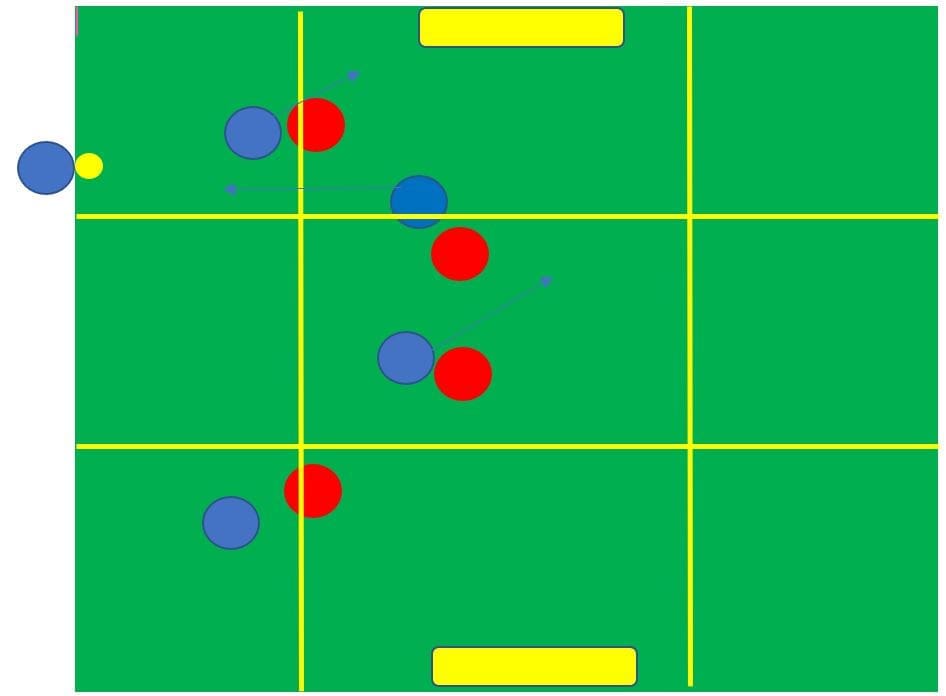

Practice four

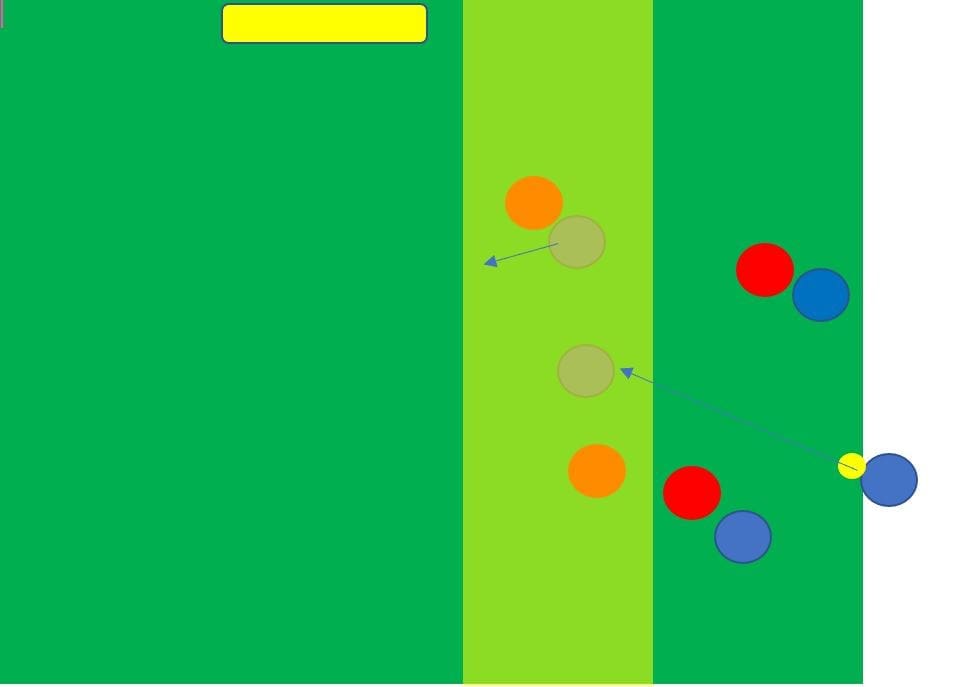

Practice four involves fewer boxes but a similar concept, with again constraints used to shape the behaviour of the players. In this practice, ‘golden boxes’ can be introduced, where one player must always occupy the area, but the same player cannot occupy this box for more than five seconds. This causes constant rotation similar to the post rule in Basketball, and therefore forces players to arrive into space and receive as well as rotate.

The touches each player has in each box can also be limited so that players are forced to move throughout the practice in order to gain more touches. Again, the location at which the throw-in is taken should be adjusted regularly in order to allow the player to gain as much variability from the practice as possible and to pick up attractors and relevant cues from lots of different situations.

Again here is an example of a simple rotation that allows the player to receive the ball in a golden zone. From there the structure of the team has to be considered in order to allow the team to progress with limited touches, and quickly to avoid the defence getting set. Regulating touches and time spent in boxes may become difficult but I suppose there is an element of trust with your players depending on their age, so it certainly isn’t impossible to police this.

Conclusion

Specialist coaches such as throw in coaches are something I feel we will see more of in the coming years, and set-pieces is certainly an area in which this has taken off, as this set-piece analysis has shown. A good/bad throw can be the difference between creating a game-winning moment and a game-losing moment, and as a result in an environment such as elite football where the difference between these moments costs jobs, money, and titles, it is vital they are not scrapped as “just a part of the game.”

Comments