Transitions are a massive part of football and have gained more popularity in recent years due to successful teams being focused on them. Transitions can be defined as the periods between possession, I.e the moments after the ball is lost and the moments when it is regained. This tactical analysis will focus on the moments when possession is regained, or offensive transitions, and will show the principles of offensive transitions and how to coach them, with influences from the tactics of top coaches such as Jürgen Klopp, Ralf Rangnick, Ralph Hasenhuttl and José Mourinho.

Beating the counter-press

Usually, when the ball is won back, the first step to a counter-attack is to overcome the pressure from the opposition to prevent the ball from being lost again straight away. To overcome the counter-press there are a number of components:

-Intelligent, anticipatory movement to support

-Quick decision making

-Creation of angles

-Awareness of passing lanes and pressure

Quick decision making is obviously a key principle of counter-attacking which will appear throughout this article, but here with usually immediate pressure from the front it is particularly important, and players have to quickly switch from out of possession decision making to in possession decision making- which is where anticipation plays a large role.

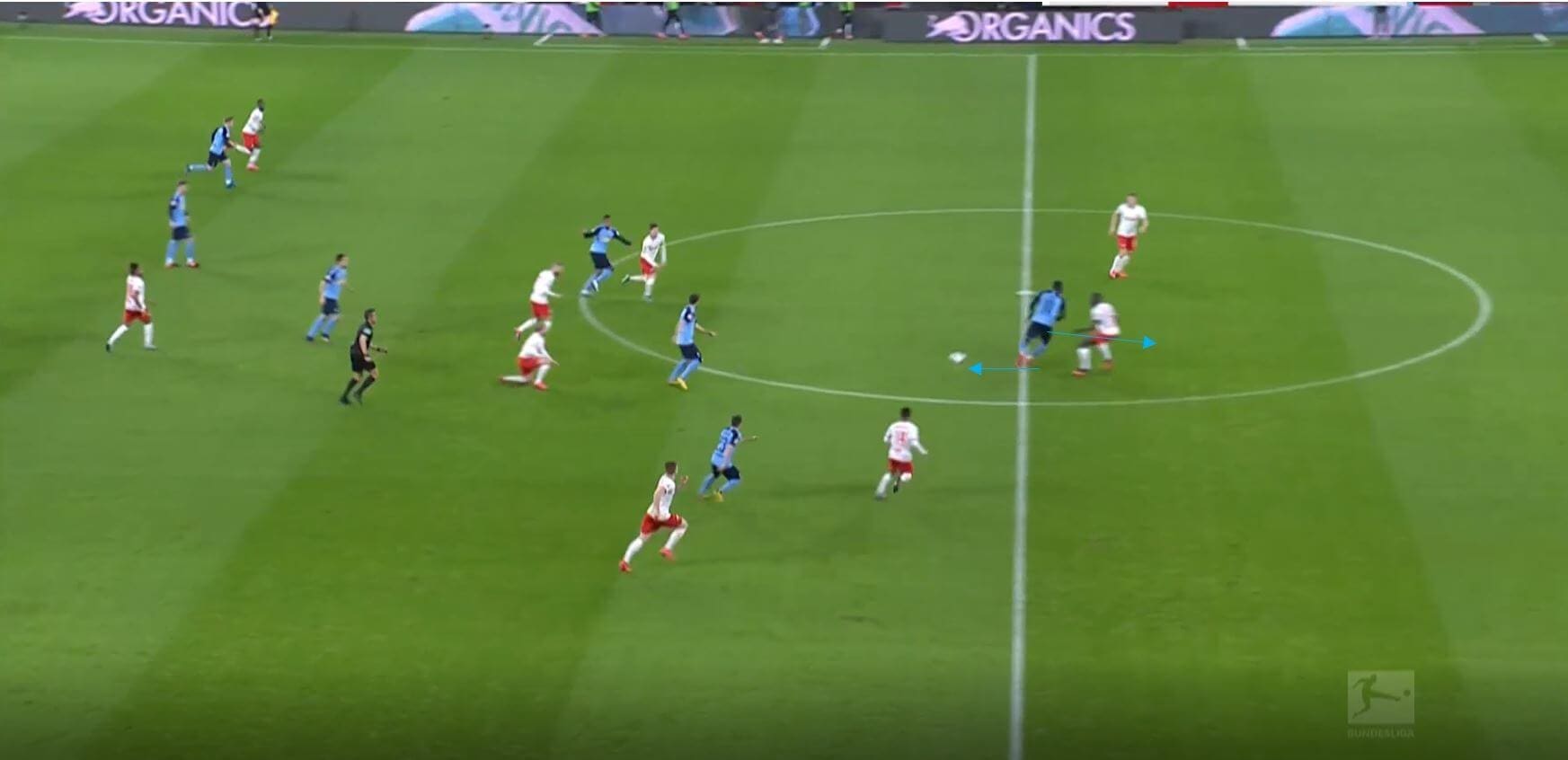

We can see here an example of these components in practice, with RB Leipzig recovering possession and looking to transition immediately. Recovering the second ball, one player moves to receive the ball. The other player beside him, Emil Forsberg, already makes a movement forward into space before the other player has even received the ball. This gives an angle to play the pass and beat the counter-press from the oncoming Leverkusen player.

We can see another example from RB Leipzig here under Hasenhüttl, where immediately a player moves to create an angle to receive and progress play forward. Having a structure which allows for players to stay ahead of the ball obviously helps this, but both the carrier and the receiver have to make decisions quickly in order to make the correct movement and find the correct movement with a pass, while under pressure.

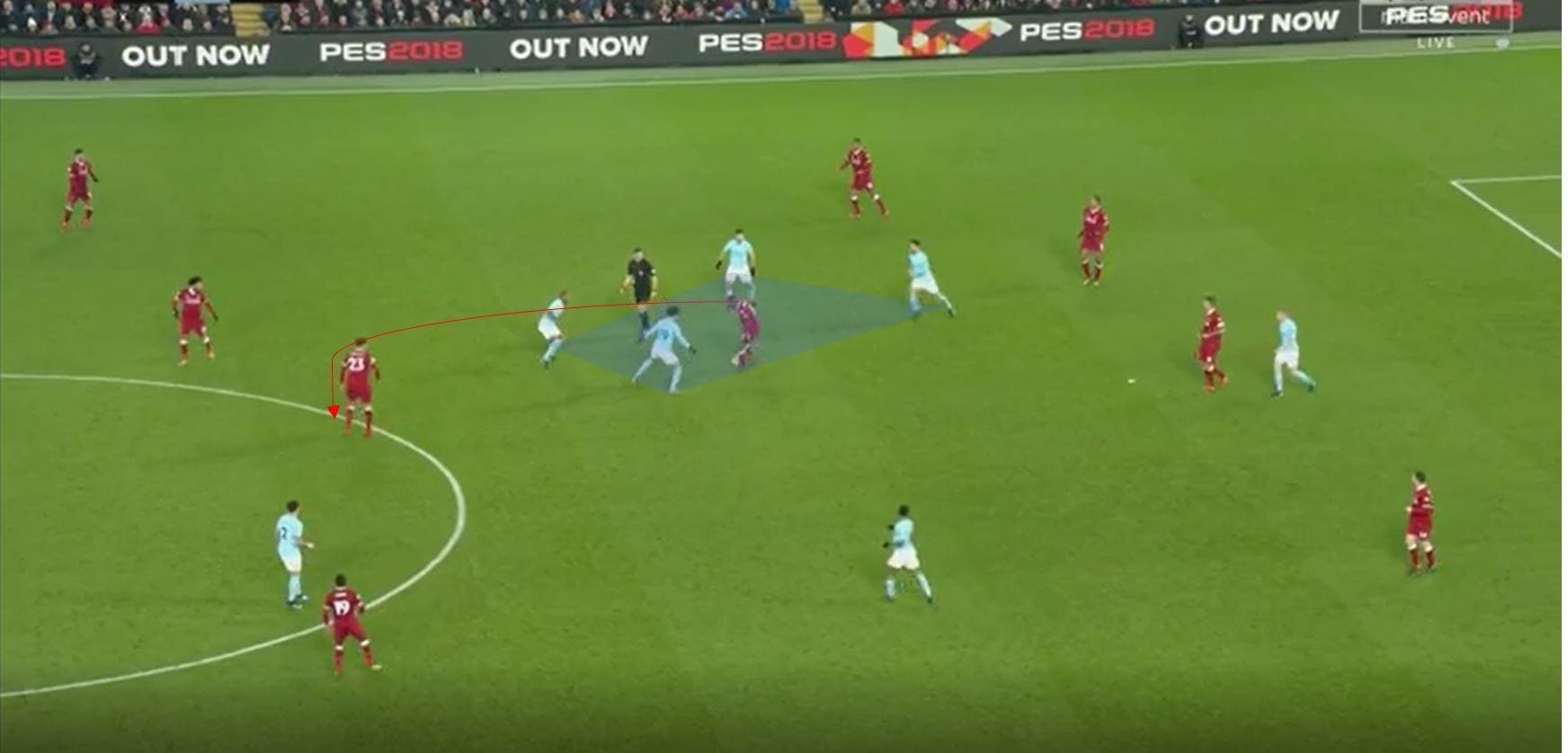

We can see one final creative example of beating the counter-press here from Gini Wijnaldum. Here, under intense pressure from Manchester City, Wijnaldum chips the ball over the pressure into the Liverpool players waiting behind the pressure. Oxlade Chamberlain on the right also creates an angle to receive, but Wijnaldum opts for this creative option. All of these examples lead to goals within 12 seconds of winning possession.

Practice idea

Any practice that involves beating the counter-press could also involve coaching the counter-press, and so it’s simply a case of choosing which side to coach. Each one of those four components mentioned should be involved within the practice for it to be effective, and if it can be made into a game realistic practice, this helps to process it and apply it within a game. It’s also important to note that we are also looking to coach some creativity and decision making, and so for me personally doing much command style work isn’t going to benefit the players.

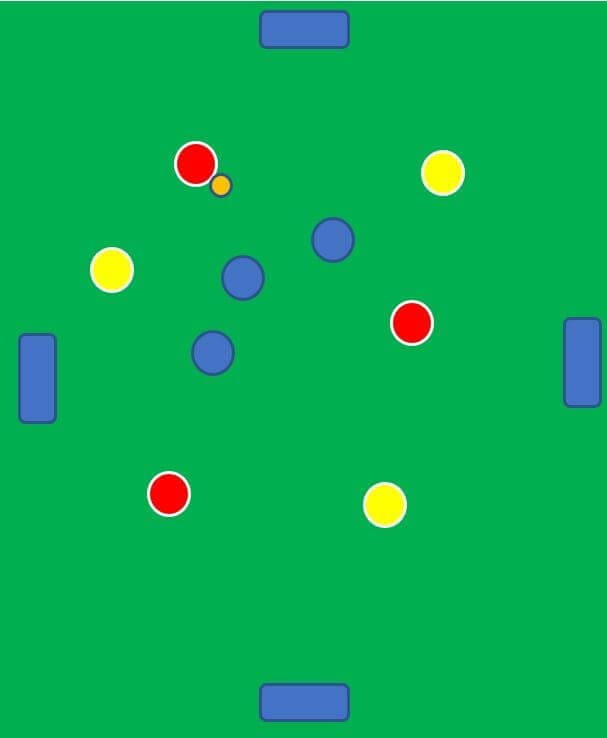

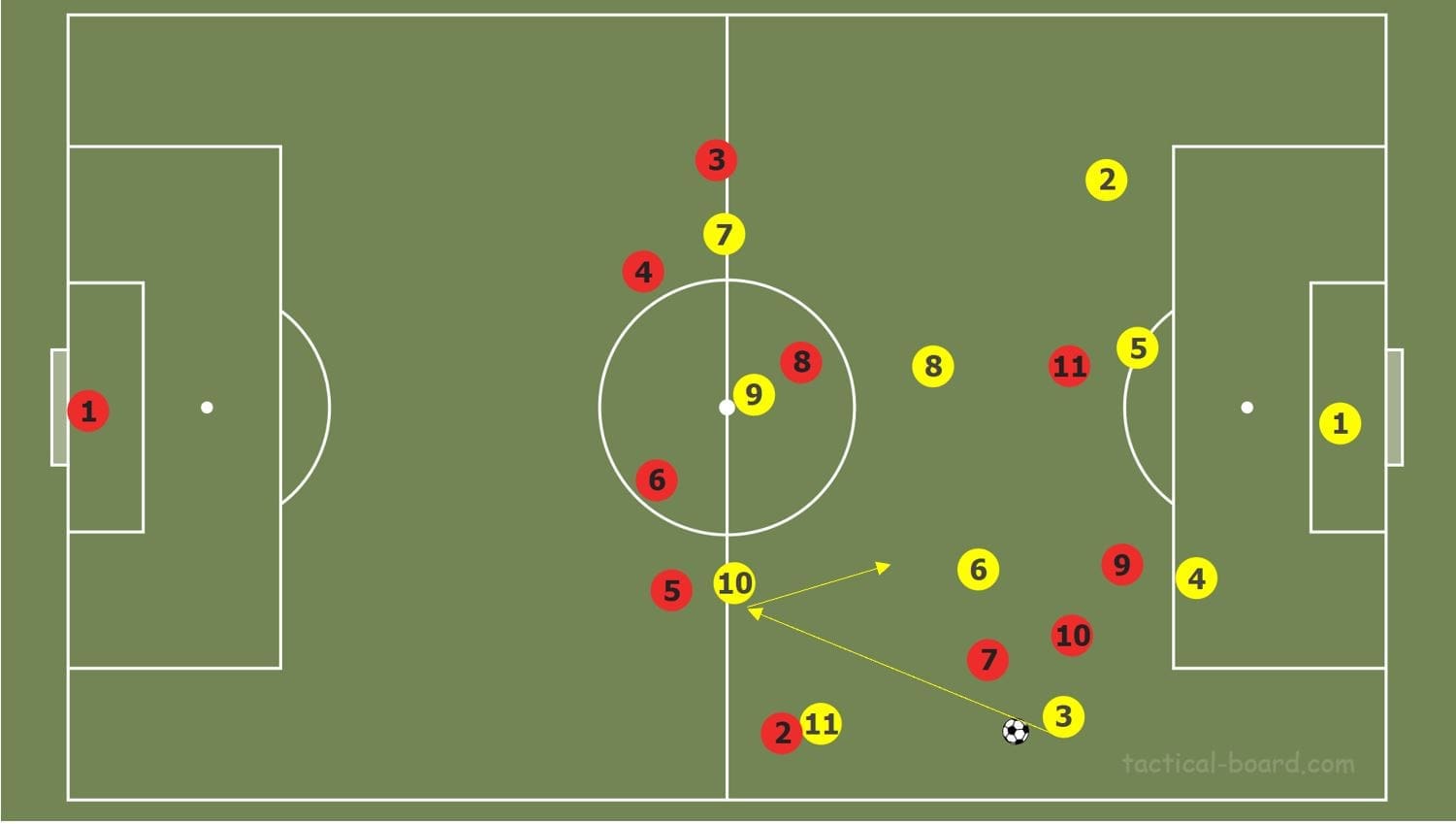

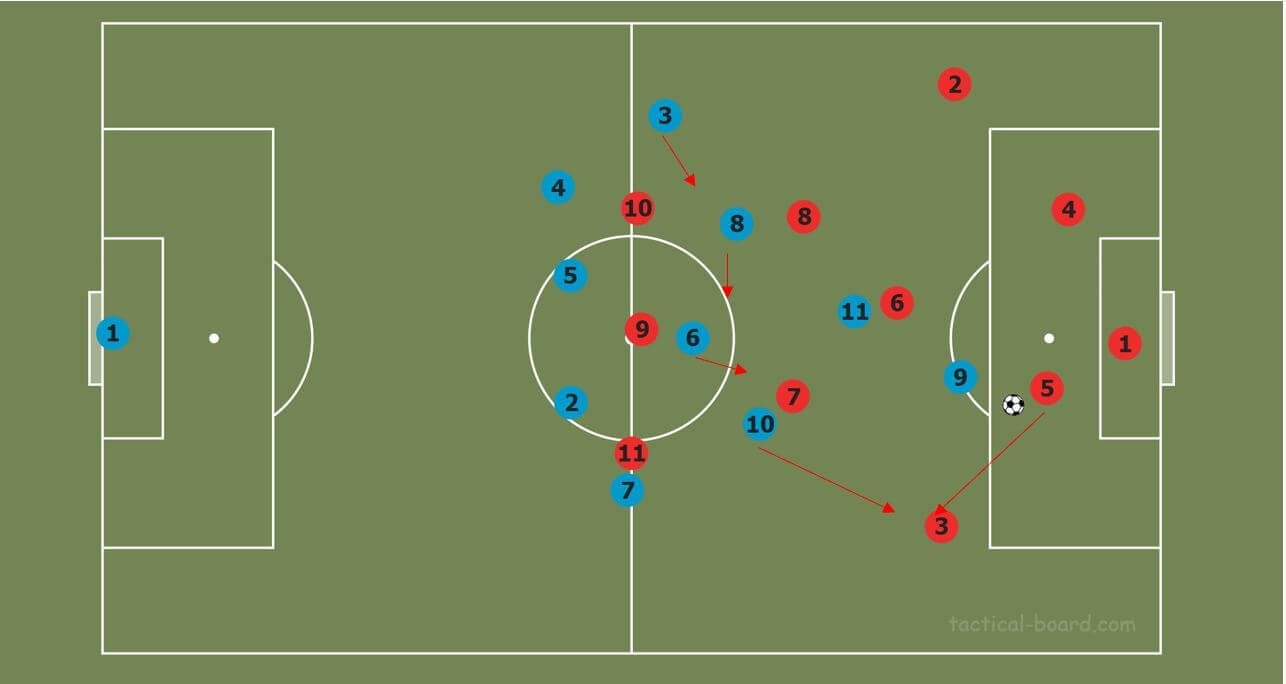

The practice involves a rondo of 6v3, with three teams altogether. Two teams work together to retain possession (red and yellow) while another team looks to win the ball back (blues). If the ball is won, the blues look to score in either of the four goals, which in a game represent passing lanes to start counter-attacks. The teams retaining possession should be reminded that counter-pressing is needed and therefore managed accordingly. The attacking team must press effectively and then transition to get the ball into a goal, all while under pressure from multiple angles, which makes the practice mostly game realistic.

There are multiple variations and constraints which could be placed on the practice, such as rewarding the players with 3 goals if they score in one of the goals in front/vertical to them, as this reinforces the idea that the main aim is to play forwards straight away. Numbers and pitch size can also be edited to make it easier/more difficult, with the tighter the pitch is the harder it is for the attacking side. Again, most counter-pressing practices, which I’ll be covering in another article, would work to train this quick, under pressure decision making to beat the counter-press.

Support

Once the counter-press is avoided, support around the ball is needed in order to progress up the pitch, which we also covered briefly above. Support can be provided in three different ways, height depth and width. This attacking principle decides which direction the ball is played in, in that during a counter the ball can be played forwards, laterally or backwards. In a counter-attack, the best pass to be played probably isn’t a backwards one unless to create a better angle, so this leaves playing sideways or forward, so in this section, we’ll assess these options and how the change the dynamic of a counter-attack.

Playing to the furthest man

Playing forwards can often involve passing to the player furthest player up the pitch, which has some benefits to it. One such benefit to playing forwards to the furthest player is that it allows players time to move forward and support the ball carrier, and the opposition cannot react to the forward runs from players effectively. Another obvious advantage is that it gets the team high up the pitch, but this is only an advantage if there is support around the furthest player. By playing to the furthest man and laying the ball off, this ensures the body orientation of the player receiving is good for quick forward play, as they receive the ball already running forward.

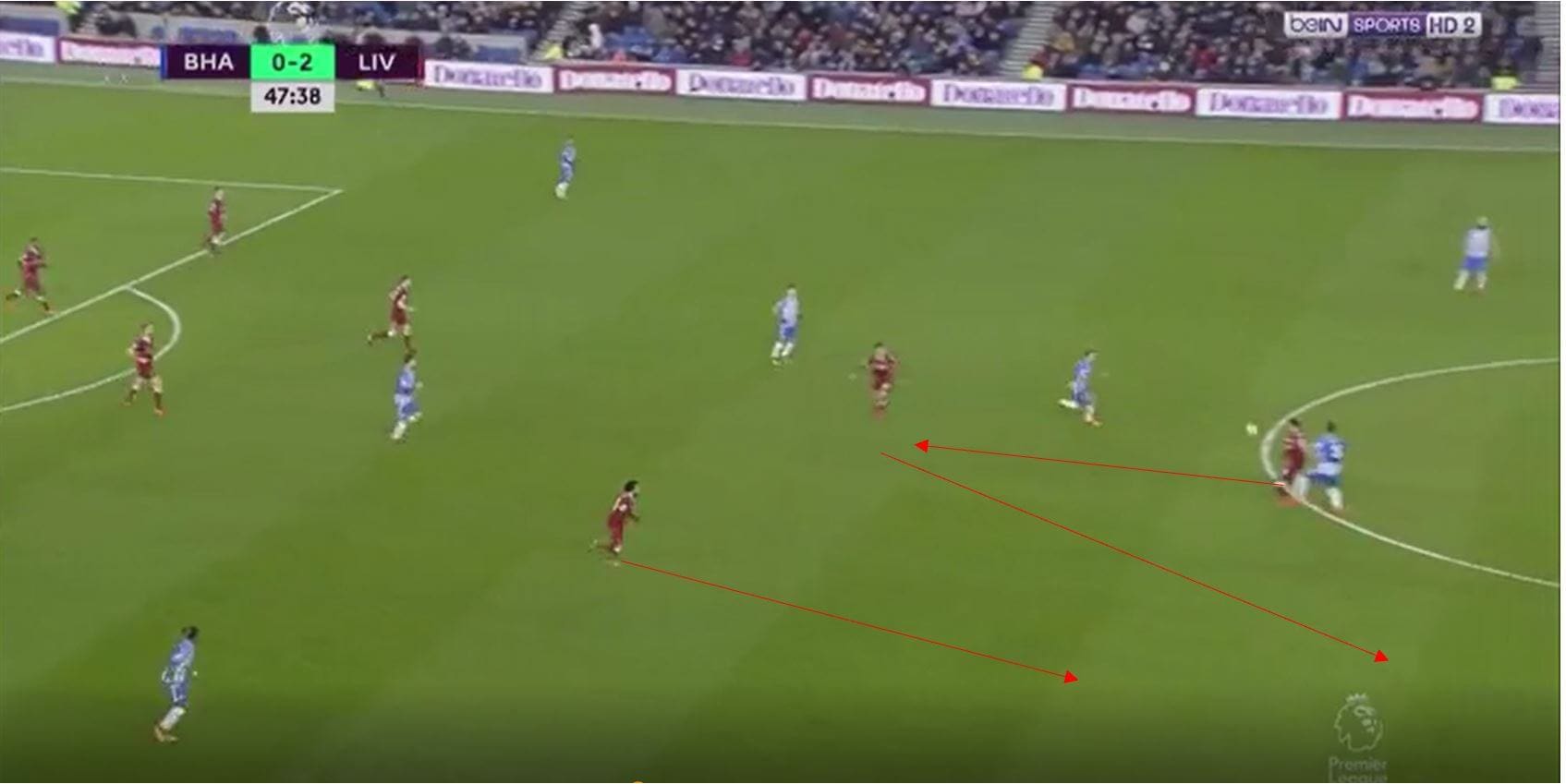

We can see an example of these principles here, with Liverpool combining using an up, back, through combination. The ball is played forward towards the furthest player Roberto Firmino, with supporting movements being made laterally and vertically. This offers Liverpool a quick way to progress the ball up the pitch, and while the ball travels towards the furthest man, supporting runs can be made. Within ten seconds Liverpool have scored, due to progressing play quickly and supporting players making quick, intelligent runs already facing the goal they are attacking.

After this game, Klopp said that this goal was: “One of nicest counter-attacks” he had ever seen.

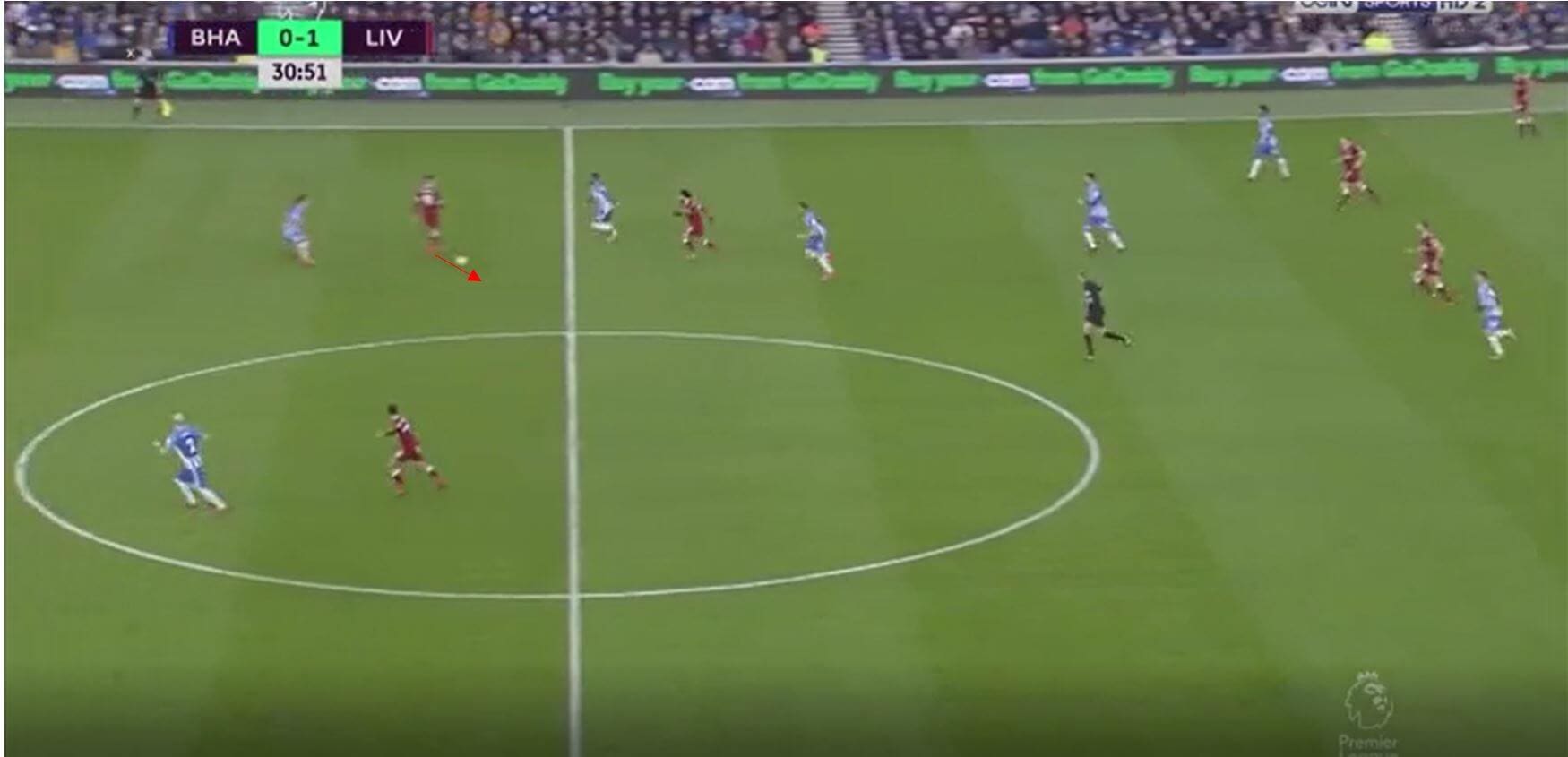

We can see this again here, with the ball being played up to Roberto Firmino and Mohamed Salah receiving the ball already running towards goal.

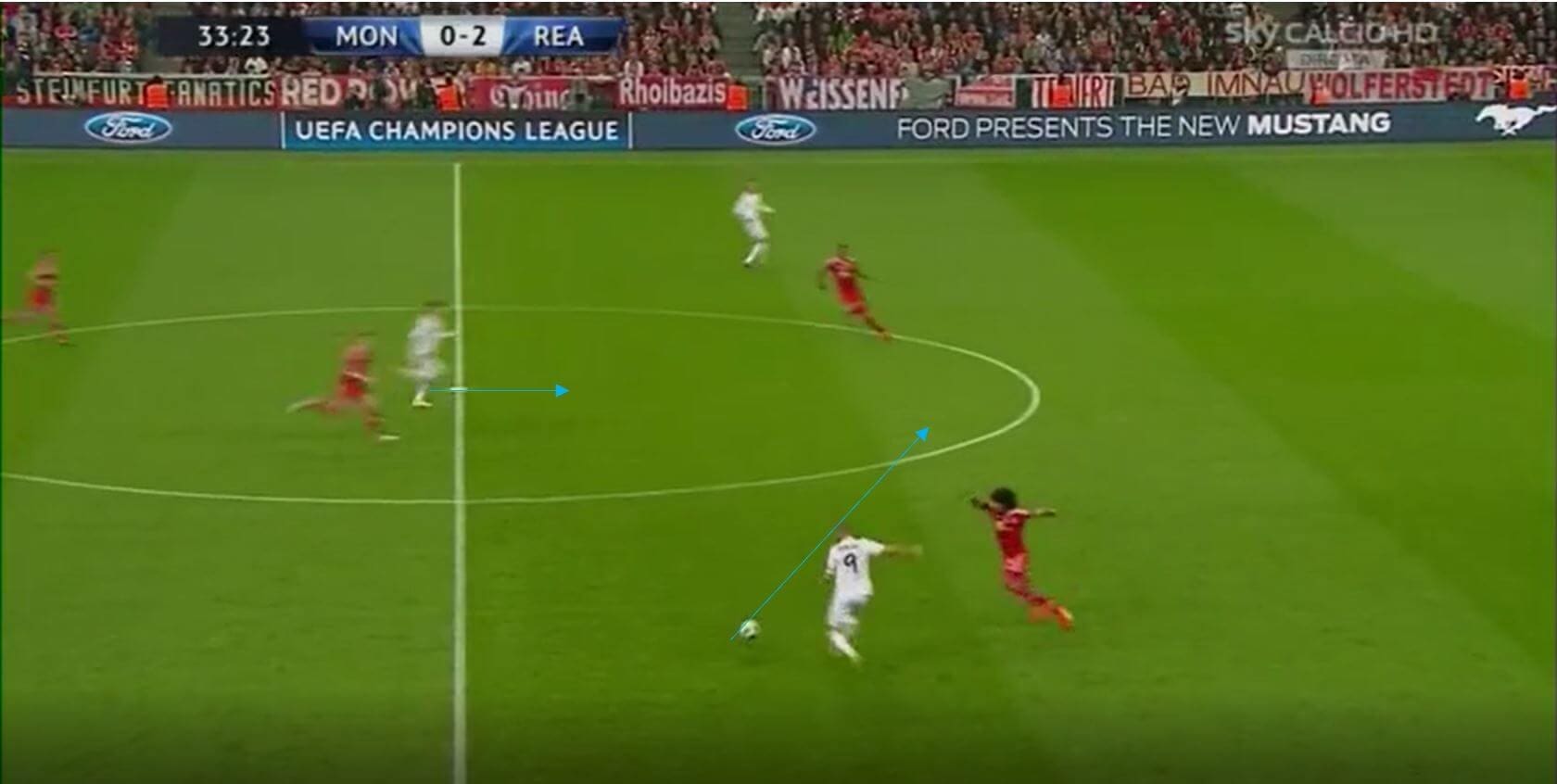

We can see an example here from an iconic counter-attack by Real Madrid against Bayern Munich here, where following the initial counter-press being beaten the ball is played to the furthest player. While the ball travels, Gareth Bale is able to sprint forward into a position, and cannot be picked up by a Bayern marker, and therefore Benzema can turn and lay it off to Bale who is in an ideal body shape to receive and go forward immediately at pace. Within seven seconds the ball is in the net.

Another benefit to playing this kind of combination is that it allows you to find players who were previously pressed out of the game, as we can see below. If players are in the cover shadows of pressing players they can’t be directly passed to, and so hitting the furthest player allows you to access these players in good, usually central areas, which allows for a range of passing options.

We can see an example of this here again with Liverpool, where the ball is played to the furthest player and the ball is laid off to a forward-facing player. This then allows the other players to start movements forward. Notice how the central player has already started to run before the furthest player has even laid the ball off yet.

In one astonishing goal by Borussia Dortmund under Klopp, we can see all of these benefits happen. Dortmund here show us the importance of passing forward, but also highlight the importance of that furthest player not being too high on the pitch.

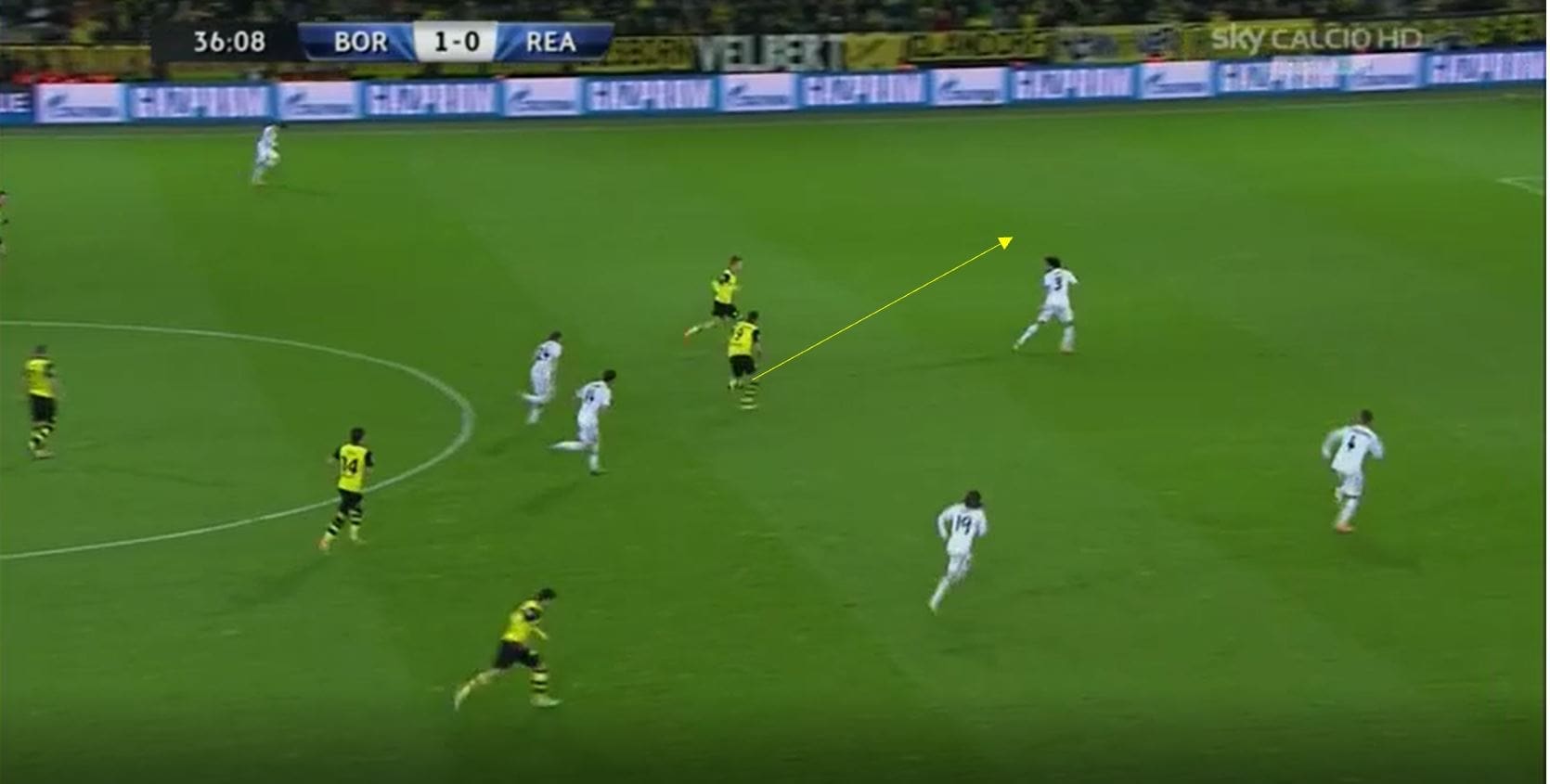

Here, we see Dortmund performing what we have seen so far, with an up, back, through combination in the middle of the pitch. Again, there is constant movement to support in order to replace the player who has laid the ball off, and because they are so deep, they have to rely on multiple combinations.

Dortmund continue to provide constant vertical support, with a player making the run forward and another player moving into the space left.

This means that when they get high enough the pitch to start trying that killer through pass, they have support from behind to do so as they do here, where Dortmund combine with six one-touch passes altogether to score. So how do you coach this?

Practice idea

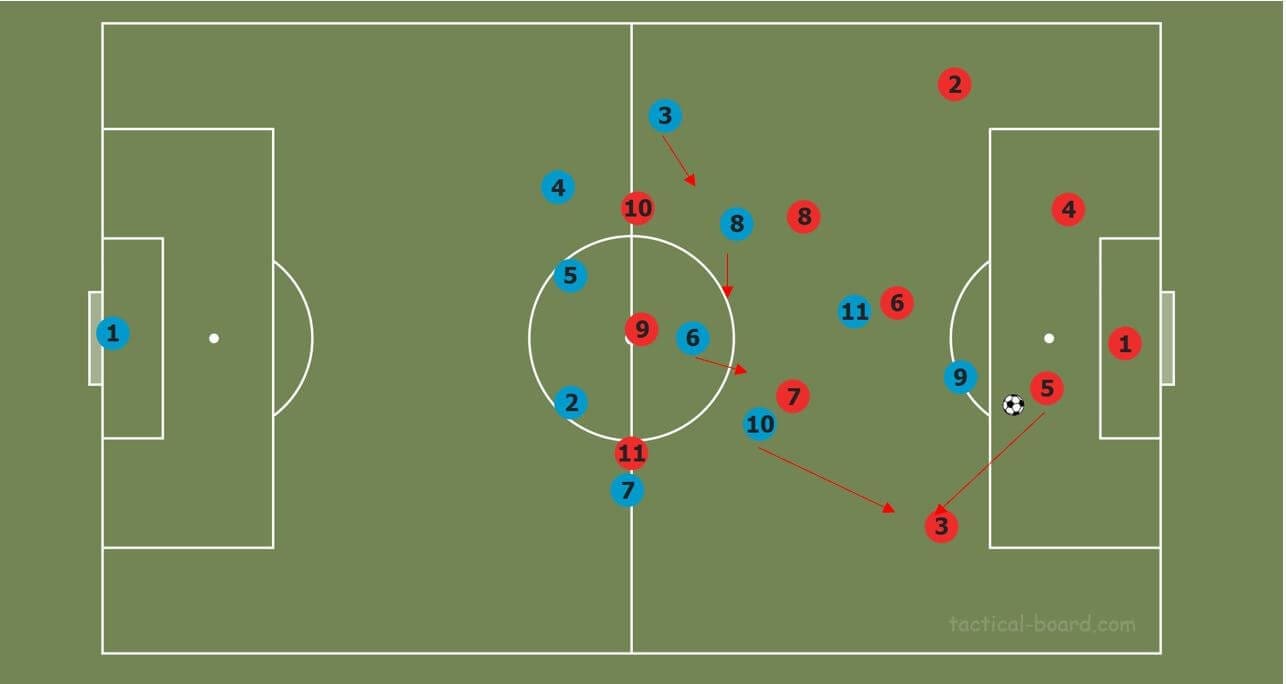

This practice aims to look at playing vertically and supporting the ball after a press and includes a number of the principles talked about so far. Play always starts with the blue team in midfield, who look to score past the reds defending. The reds are locked into their zones when out of possession, and look to press to win the ball back before countering. One of the strikers from the reds can drop into the other zone to receive, and if a goal is scored, the number of red players within the goal zone is the number of goals it is worth, so if four players get into the goal zone, it’s worth four goals.

Initially, the practice can be slightly less constrained, with both players being allowed to drop once the reds are in possession. What you may see is both players dropping and the team losing its height, which is a prime opportunity to ask the group what isn’t working and why. This practice can be adjusted numbers wise to replicate an opponent and your own press, and another key principle not yet mentioned is also touched upon.

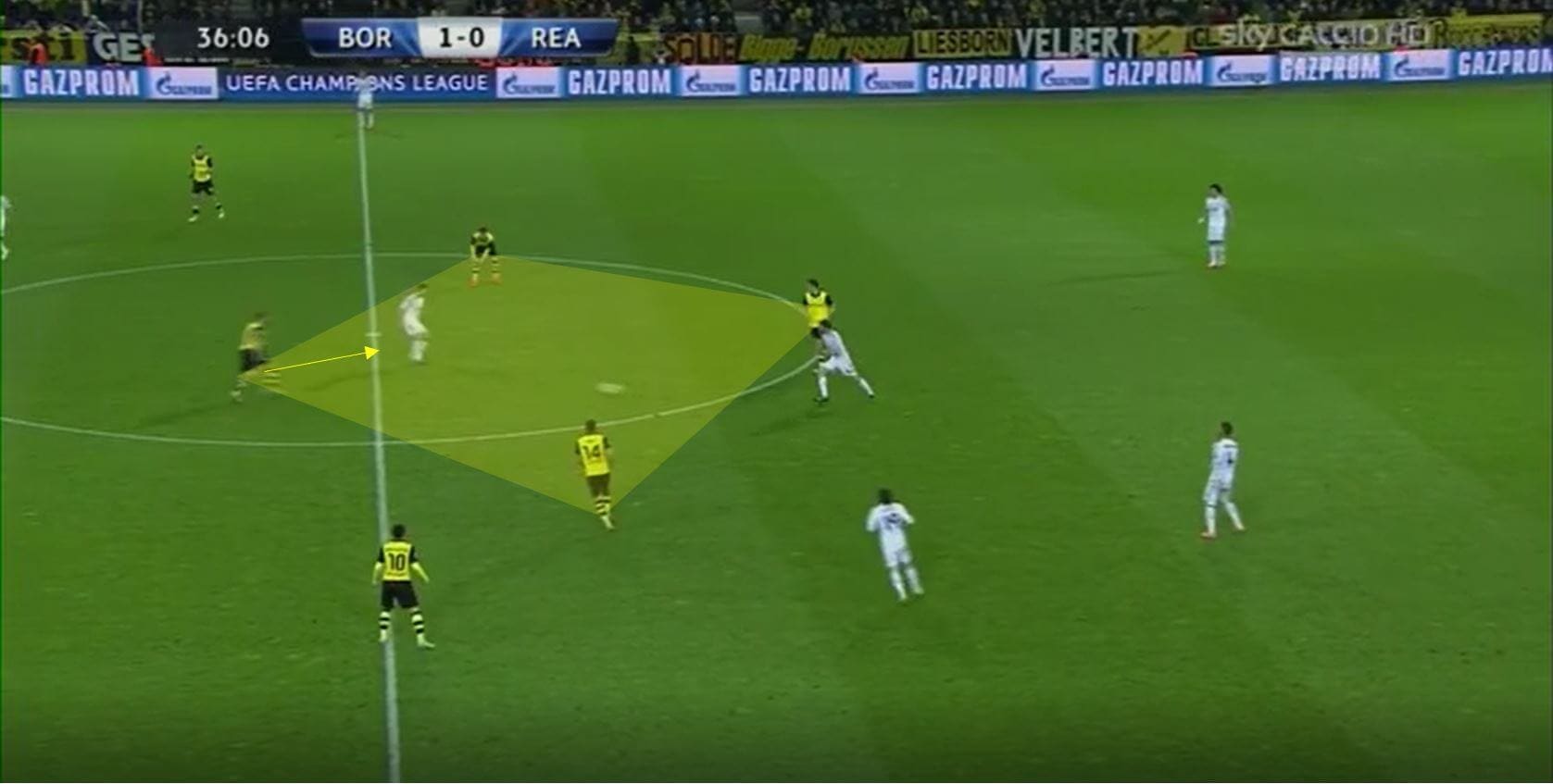

Quite simply, the higher a team presses when out of possession, the higher the team is if they win possession, therefore it is easier to create goal-scoring opportunities. We see Dortmund commit a lot of players forward in relation to Real Madrid’s structure and are able to win the ball.

Therefore when they win the ball, there is no immediate counter-press and they have a 2v2. Marco Reus makes an intelligent run into the space, forcing the defender to make a decision and Dortmund score eight seconds after they won the ball back.

Therefore, within that practice outlined, the higher the player’s press, the more players they can commit into the zone and the more points the goal is worth. Let them try and figure this out for themselves.

Is width good in counter-attacking?

You’ll notice that for the majority of these examples, play is built up through the centre, and while I have mentioned the principles of height, depth and width, width isn’t ideal in counter-attacking; at least not too much of it anyway. This is quite simply because the goal is in the centre of the pitch, and so the wider you go the further away you are from the goal, and therefore the longer it takes to get into a position to score. Counter-attacking down the centre is also much harder to defend against, as there are more passing options/angles for the ball to be played into, which of course aids the decision making of the ball carrier. Therefore just as a disclaimer, I wouldn’t use width as a coaching point greatly, and instead, just encourage lateral support and short passing.

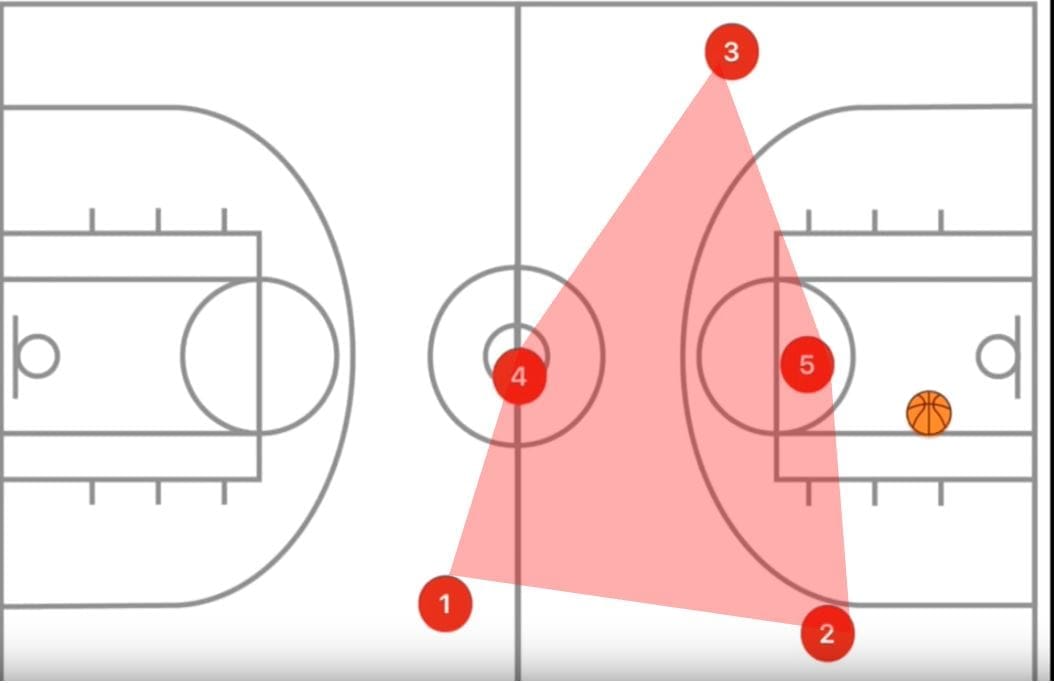

In basketball transition practices that I have seen, teams are coached to move wide in order to create space in the middle, but this can’t apply to football simply because of the differences in the size of the pitch/court. Certainly, if you stay slightly wider of the defenders then you can cause an issue, but if the player is positioned too wide then a defender will move towards the ball carrier and deal with the situation. In basketball if you move wide you still have an immediate chance of scoring, in football, you don’t.

How to replicate the speed of counter-attacks

Counter-attacks are a lot about speed of play and how quickly you can take advantage of the opposition being disorganised. Ralf Rangnick once stated:

“The conclusion is that the majority of goals are scored 12 seconds after winning the ball back. Ideally, you should win the ball back 8 seconds after losing it.”

Rangnick stated this a while back now, and this is something which has been validated recently, with the UEFA Champions League technical report stating that the average time taken to score a goal was 12.5 seconds. As a result, when coaching counter-attacks speed has to be a factor, otherwise you are simply coaching attacking. In truth, this average probably isn’t reflective of all other transition based sides, for example, Liverpool’s average time in possession before scoring was 7.81 seconds last season in the Champions League.

In order to maximise the speed of counter-attacks, there are some key components, some of which have already been discussed:

-Few touches

-Height

-Body orientation

-Playing into space or onto the front foot

And the most vital:

-Speed of thought

Playing on as few touches as possible is obviously important, as running with the ball is slower than running without the ball, therefore, as we saw in the support section, if you can play the ball and allow others off the ball to support you, you can counter quickly. Having height in the team means you do not need as many combinations as seen in the Dortmund goal highlighted, because even though Dortmund manage to score from this situation, the more touches you have the higher the probability of one of those touches being wayward. Liverpool in the Champions League last season averaged 2.51 passes before scoring, highlighting this principle.

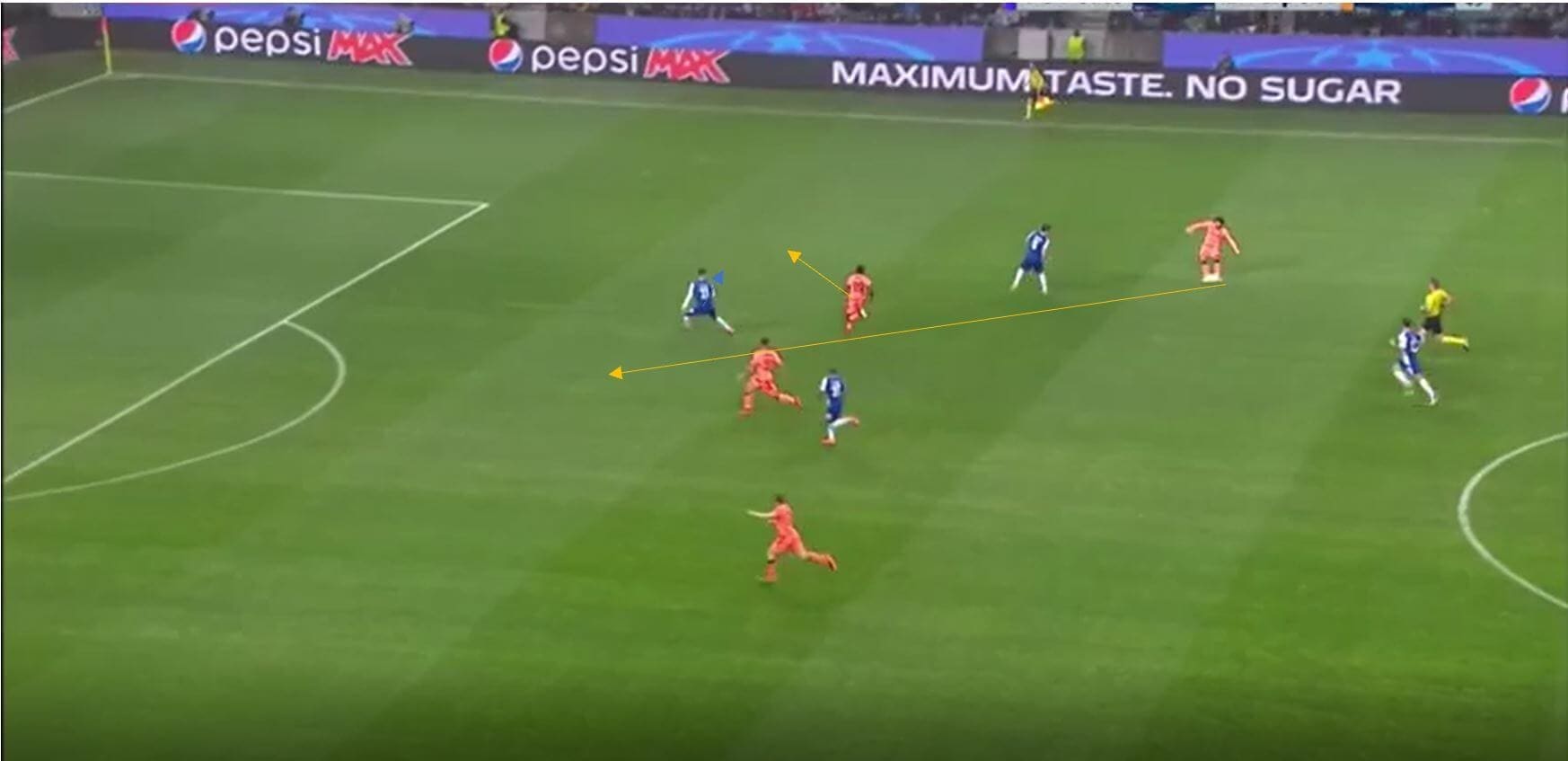

Body orientation and playing into space / on the front foot have also been covered in other sections, with one of the disadvantages of playing laterally being that it requires more touches and can adjust body position slightly, meaning that players don’t run as quickly as they do when playing behind the furthest player. Lateral support without height and quick passes can be useful when the opponent is underloaded, for example from a corner situation, but in general play, it usually takes too long without height and is more easily defended as the immediate threats are visible and running towards you explicitly.

We can see some examples of these points here, with intelligent movement from Sadio Mané to create space for Firmino, who is found by an excellent pass from Salah. The pass is played in front of Firmino to allow him to move onto it quickly and get a shot away.

In this example, we see Firmino playing the ball perfectly onto the front foot of Mané which allows him to run onto the ball in his stride and score.

The most vital part though is speed of thought, and this is developed through making decisions under pressure.

Practice idea

When a game of football is full of transitions and going end to end, people say it’s like a game of Basketball, so why not actually make training like a game of basketball? Basketball is so full of transitions because of its own element of timing thanks to the shot clock, which in the NBA is 24 seconds. Therefore, in this conditioned match, we will also have a shot clock, which in this practice is set at 12 seconds to replicate Ralf Rangnick’s views, but it can, of course, be changed based on the context. If you aren’t familiar with a shot clock – if a shot is not taken after 12 seconds, the ball is turned over to the opposing team.

In terms of pitch design, a long, narrow encourages forward passing the greatest, and so this is what I would use, but the main feature of this is the shot clock, which should make it a hectic, disorganised game, but that’s what transitions are. The more it is done the less hectic and more precise it should become, as players decision making will sharpen. As Ralf Rangnick says: “You have to be dynamic and precise”.

Conclusion

So much of what has been written is about developing players who can make decisions quickly under pressure, and therefore this has to be coached in a certain way. Outside of sport, you develop your decision making by interpreting stimuli and then making a decision and acting on the feedback from it. The more stimuli you are exposed to over time, the better your decision making becomes when it takes place within a varied environment like Football, therefore, players have to be given an environment to make decisions in a variety of game realistic settings, and these practices outlined should allow for this to happen, all while still coaching the coaching points mentioned.

This analysis article like my previous ones has followed my constraints based type philosophy, as this allows for encouragement of coaching points without simply solving the problem through command style. That being said, that’s just how I coach, and so feel free to interpret this article however you wish. As always, let me know if you found this article useful, as a defensive transition (my current favourite topic) piece may be next.

Comments