The highline in football is not a new concept but one that coaches still treat with some trepidation, mainly because it is rarely coached and often just told.

Many coaches don’t spend time on the skill of catching an opposition forward offside, but when teams employ a high press, coaching the high line is vital to ensuring defensive solidity.

At the elite level, the importance of an excellent offside line is increasing, with VAR now meaning that offside calls can no longer be affected by human error, and therefore, if your offside line is bullet-proof, you will be rewarded.

Liverpool began using a more aggressive offside trap this season because of this and have been rewarded as a result.

In this tactical analysis, we will

examine the stages of coaching the high line and the offside trap and providesome exercises that could be used within coaching sessions.

Step one – Vertical compactness

A high line is used to reduce the space the opposition has to play in within its own half.

Within football, a team has three options for moving up the pitch and closer to the goal: play through, play around, or play over.

Playing with a high press and a highline football aims to cut off the opposition’s ability to play through or around but increases the risk of the opposition playing over.

As a result, a disciplined, well-coached offside line is needed to minimise this risk and, therefore, simultaneously minimise the risk of all three of the opposition’s options.

Therefore, the first step is to coach the movement of the defensive line in accordance with the height of the rest of the side before coaching the offside part.

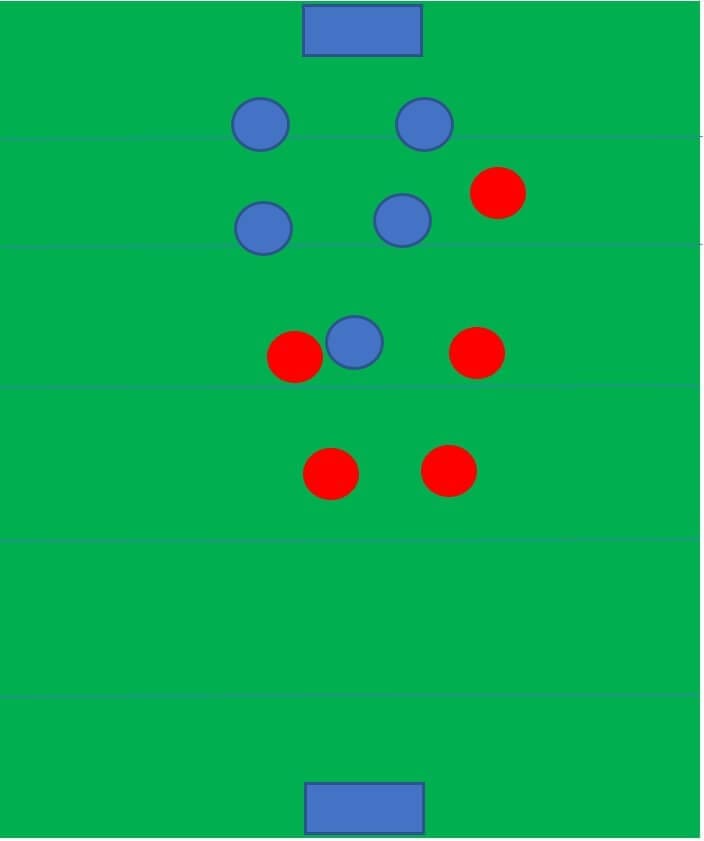

A relatively simple exercise that can be done to coach this vertical compactness is the one seen below.

Play a typical game with whatever other conditions you want, but add six zones across the pitch.

Goals scored only count if the team in possession occupies only three consecutive zones when the ball enters the goal.

Likewise, the team out of possession should only occupy three consecutive zones.

This makes the match very compact and looks to prevent large spaces that allow the opposition to play through.

If you make three zones around a 25-meter height, you would be following Arrigo Sacchi’s idea of vertical compactness.

In the situation below, if the red team loses the ball in the final zone, the forward player is likely to press with a forward movement, which forces the midfield zone to move up and, therefore, the defence to move up.

This prevents the forward player from pressing while the other two lines drop, allowing the opposition space to drive into.

Instead, they have pressure on them, which prevents passes from being played cleanly and also prevents a long pass from being played if done effectively.

How to catch players offside

I will cover four key technical points that are vital in coaching an effective offside trap/line.

The first is the positioning of the body and the feet, which Rafa Benítez recently briefly discussed.

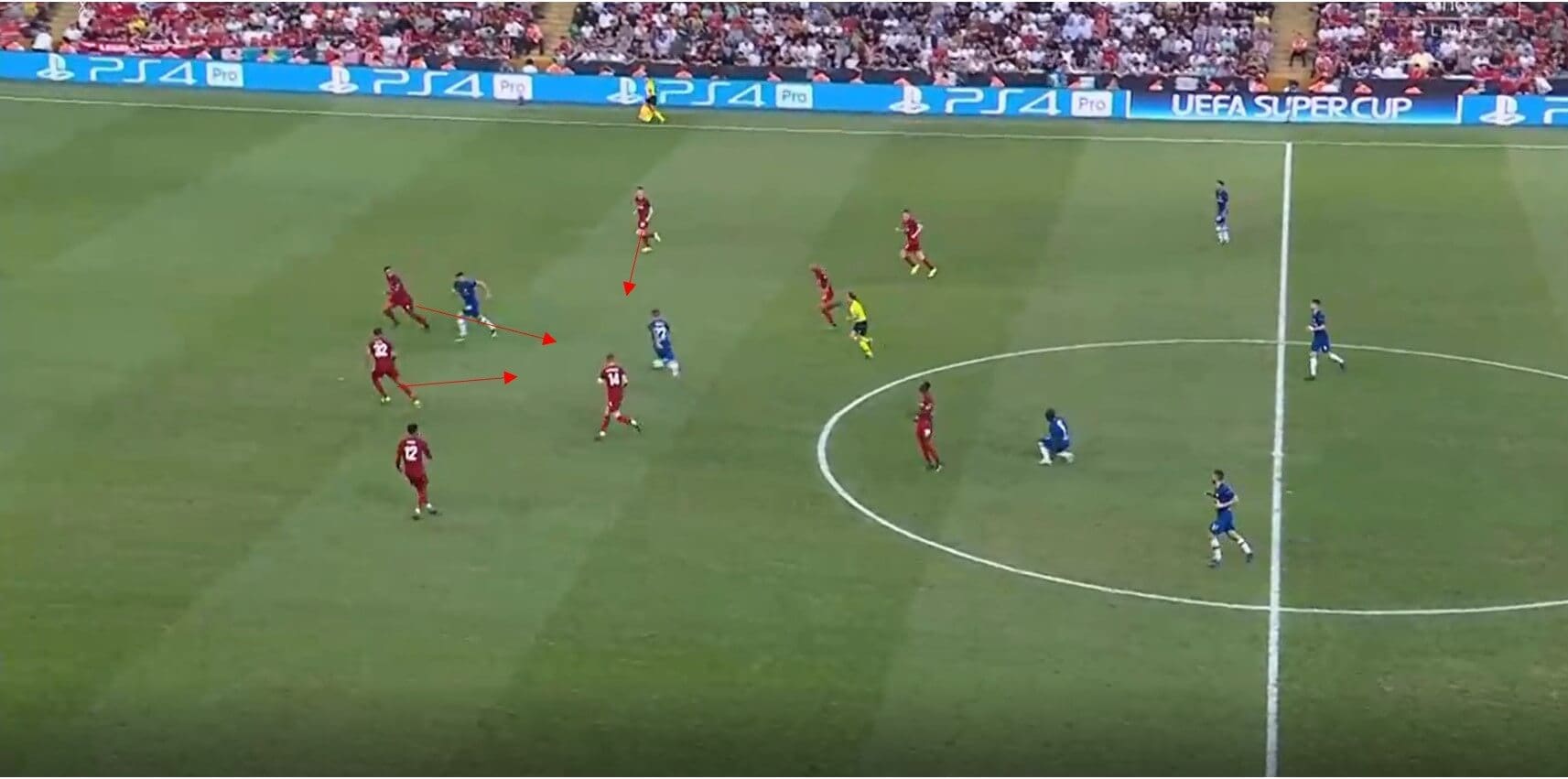

Below, Andy Robertson is a perfect example of good body positioning.

An easy habit to fall into when playing offside is to lean in the direction the ball is going, anticipating the ball going in behind and trying to catch up.

Of course, this is a bad habit, as you are increasing the area you cover and, therefore, are more likely to play a player onside.

Robertson here leans away and ensures the more central player is played offside.

Henderson and Robertson may be slightly too deep, but the body positioning is still correct, and the opposition can’t progress.

It is difficult to find footage that effectively shows foot positioning, but the details are pretty simple.

Players need to cover the least amount of space as possible while giving themselves the best positioning to recover from if necessary.

Therefore, standing flat facing the direction that the ball is coming from is not ideal, but likewise, standing so side on that you increase the depth of the offside line and play players onside is also not perfect.

Therefore, players have to find a middle ground dependent on the positioning of the ball.

If the ball is coming from the front in a central area, players have to get slightly side-on to be prepared to match the attacker’s run.

They should also have their knees at around a 45-degree angle to be able to get ready to sprint.

If the defender is standing side-on in this way, their feet are in the right position to immediately recover in the right direction if the offside flag does not go up.

The worst thing that could occur would be for the defender to be stood straight on facing the ball and to take steps backwards first before turning and going, as those few backwards steps effectively waste what little time the defender has to recover, which is covered in an analysis by me on Bournemouth on the website.

The quicker a defender is, the less they have to rely on their feet being positioned.

If the ball comes from a wide area into the centre, players have to be more careful not to lean in the direction of the ball but will more naturally stand side-on to match the attacker’s run.

In the example below, the defender nearest to Salah does a good job and moves forward with good feet and body positioning. However, his partner at the back makes the mistake of following the direction of the ball and, therefore, stands side-on and deeper.

Therefore, Mohamed Salah is played onside, and Liverpool scores.

When the ball is played in behind, it can often turn into a race between attackers and defenders, but it doesn’t have to.

The following coaching point is about almost tricking the attacker into thinking it is a race and then using the offside law to your advantage.

In situations like the one seen below, there is only one attacker running in behind and one on the ball.

With only one option, the attack becomes predictable.

So, rather than backing off and then pressing, why not press immediately higher in your own half?

If the centre-backs do press inwards, Giroud runs into an offside position as the line becomes much higher, and Liverpool should be able to dispossess the ball carrier.

Instead, Liverpool drop off and the ball is played through them.

If the timing of that initial press can be mastered so that the ball isn’t played through as they press, then the opposition loses any focal point to their attack.

The goal Manchester City conceded against Leicester was another example of a team not using this forward movement to prevent a race.

Here Otamendi stops his movement, expecting Fernandinho to do the same knowing that Vardy is much faster than him.

With a coordinated forward movement while the winger is occupied and not about to play the ball, City could eliminate Vardy’s run and isolate the Leicester attack.

Instead, Fernandinho drops, attempting to cut the passing lane or keep up with Vardy, which he can’t do.

As a result, Vardy gets through and scores.

playing over them.

This has involved setting one defender further back from the rest and then making a forward movement in order to catch the runner offside.

This was highly effective in their 0-0 draw against Gladbach, where they were exceptionally vertically compact as we can see below.

Again, this is a risky strategy and has to be timed well.

As highlighted below, if runs are made from deep, a staggered structure can be caught out.

As it happened, the target was often the wide player Marcus Thuram, and because of his higher positioning, it was easier to catch him offside.

Practice idea

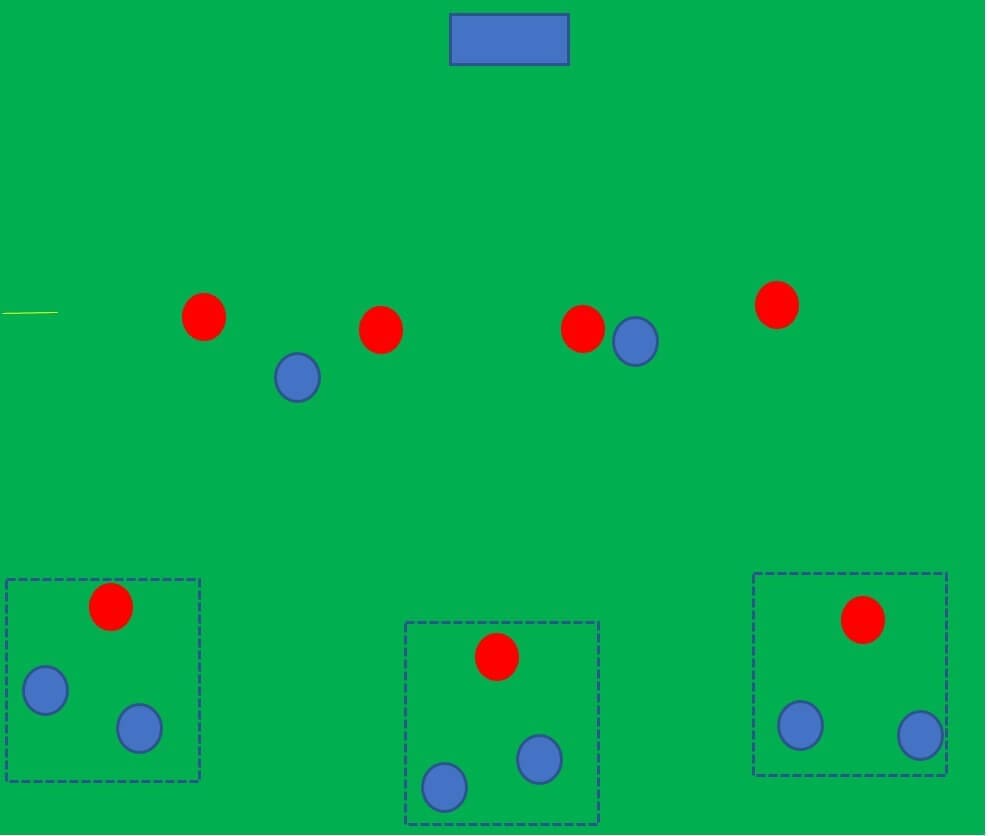

The practice outlined requires at least 16 players and seeks to replicate the situations the back line may face in a game.

The coach stands off the pitch with a bag of footballs and will choose one of the three squares to play into.

The attacking team (blue) have a 2v1 in the squares and should look to get the ball out of the square and in behind the defending team (red).

The red team are given a set starting point for their line and gain points for catching the opposition offside.

They are not penalised if they don’t catch players offside if they don’t concede.

The 3 squares look to give coaches an opportunity to coach the different positioning required for each part of the pitch, as demonstrated within the piece, and give some variance, although the attacking team can look to play out of their box and progress.

The size of the pitch, height of the line, etc.

can all be adjusted depending on how the practice goes, but there must be somebody to give reinforcement of what is offside and what isn’t so that the key points that have been covered can be communicated effectively.

If you coach alone, get a player to feed the ball in while you check for offside.

Conclusion

With the introduction of VAR, the offside trap is becoming increasingly vital at the elite level, and so the importance of marginal gains such as foot positioning will only increase.

Hopefully, this article has given some insight into this and on how to coach offsides.

Players need repetition to develop the required coordination and confidence, so criticising mistakes too harshly will not help matters much.

Comments