Tim Walter is a coach I have written about extensively already and is one of the most interesting, innovative, build-up specialists in world football. His ideas were so interesting to me that I wondered how I could coach his playing style or principles, and so I designed some sessions highlighting some key areas of his philosophy and wrote this tactical analysis. Within this analysis, you will find practice ideas based on Walter’s principles, and so although those principles are talked through within the article, if you are unfamiliar with Walter, feel free to also check out my piece on his tactics at VfB Stuttgart from the TFA 2020 magazine.

Decoy runs to create space

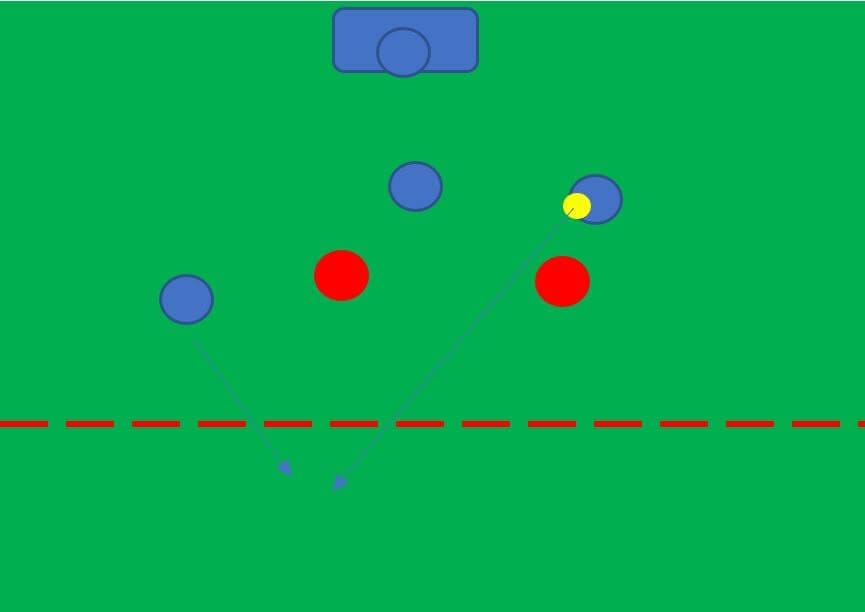

The first practice we’ll look at follows the key coaching point to deliver to players, which is that every run they make doesn’t have to be for them to receive the ball, and therefore that runs can open up space for other players. The first practice we have here can be adapted and changed in many ways, but the basic principles of decoy runs, as well as a few other principles that will be mentioned later, are present.

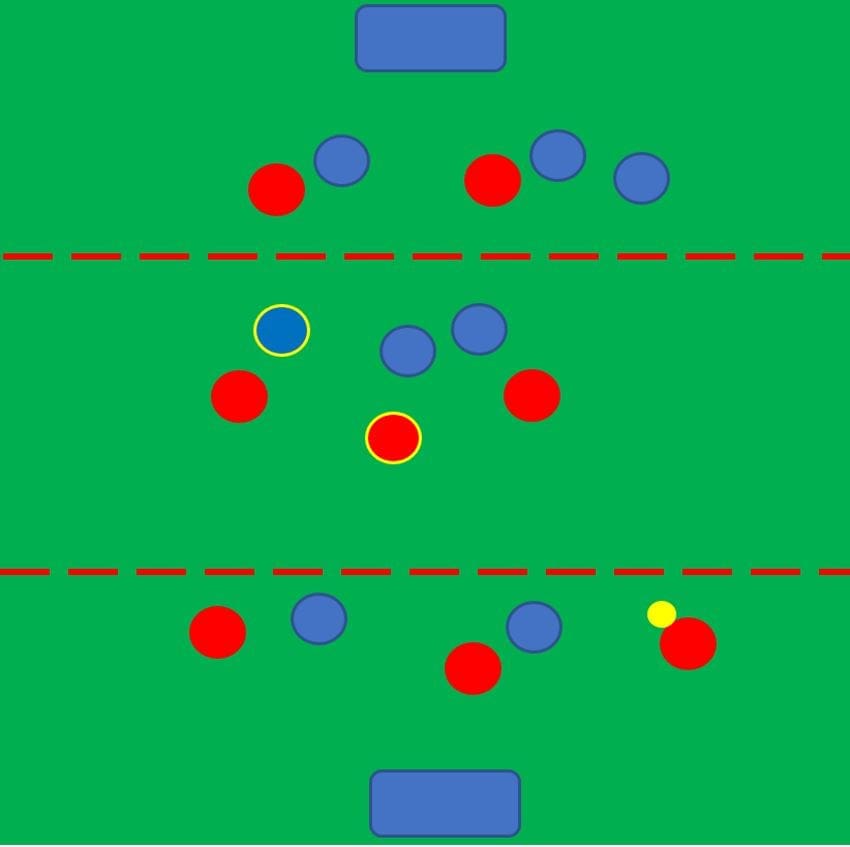

We can see an 8v8 practice here below, with players initially locked into their zones to make a deliberate point which I’ll address. Each team chooses a ‘target’ player in private (highlighted with yellow outline), who looks to be the recipient of the ball and the target of the player when the team makes decoy runs. Teams get one point for scoring a goal but get two points for the target player receiving the ball and playing forward. Therefore, they have both options and don’t have to simply rely on the target player constantly. Because the target player is chosen privately between the teams, decoy runs have to be disguised to a degree, and when the opposition figures who the target player is, it offers a new challenge for the team in possession. General coaching points within this practice which could be covered are rotations, creating overloads, decoy runs and movement, all of which are relevant and beneficial.

Teams are initially locked into zones to cause deliberate struggle, as there are no overloads in the middle or forward zones, and so this gives an opportunity for the coach to challenge players or ask questions such as “How can we get the ball through this zone?”. Players should then start to understand that players need to either drop or progress forward in order to create overloads. You can even limit which option the teams have, and so if you say players are only allowed to go into zones further forward, we start to get some overlaps in the principles of Tim Walter.

Rotations to create space and third man runs

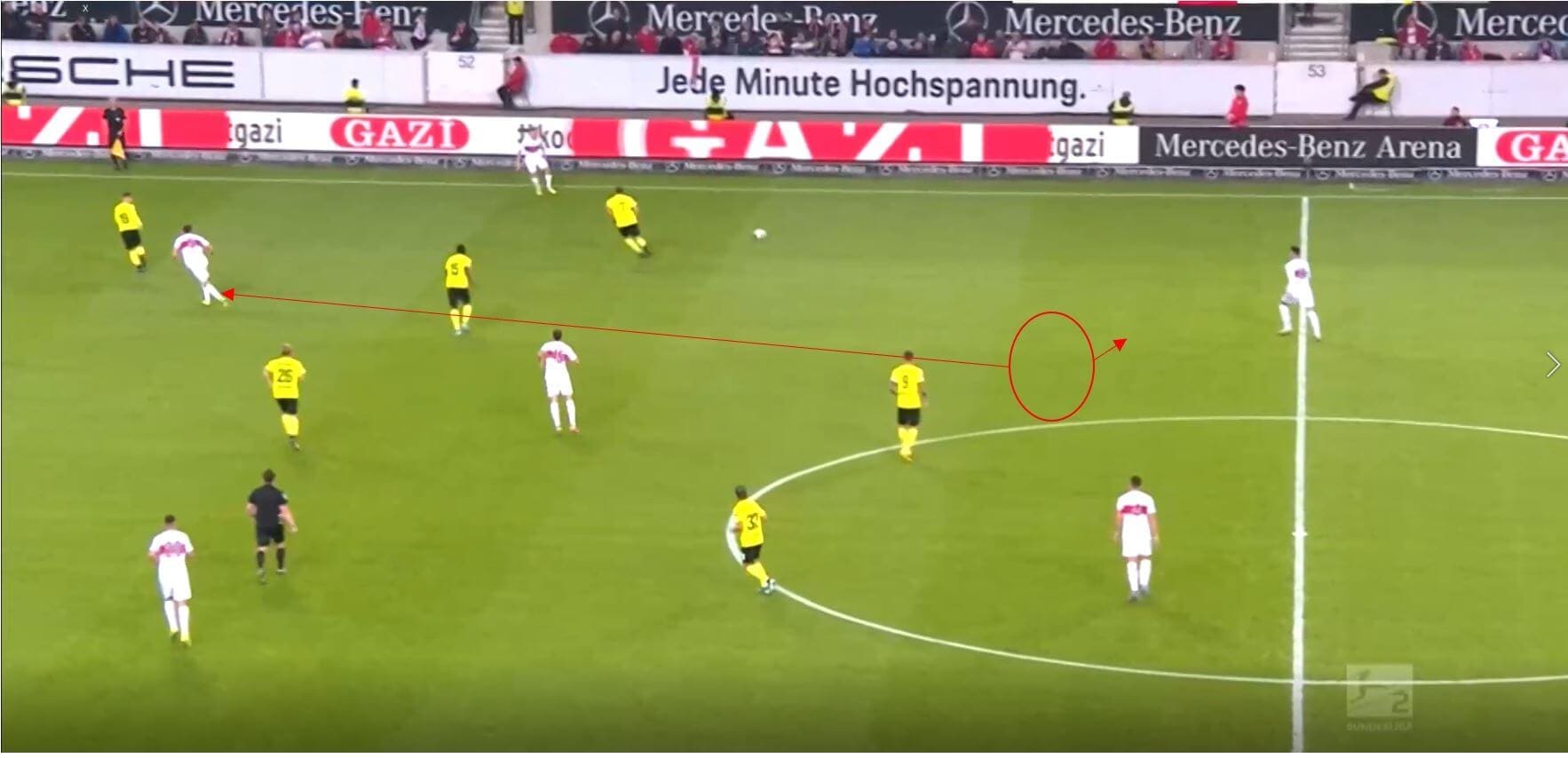

Rotations and third man runs are a big part of the way Walter’s sides progress up the pitch, and we can see this in these examples below and some later ones in the analysis. Below, the centre back, Nathaniel Phillips on loan from Liverpool, plays the ball laterally and then makes a forward movement to occupy the half-space, where he can then receive the ball and complete the third man sequence.

Here again, the half-space is used with the ball being played through it to reach the striker Mario Gómez, and an intelligent forward run inside is made from the wing into the half-space, and so the ball can be collected from Gómez. Below are some examples of practices that can help players to understand and utilise this concept.

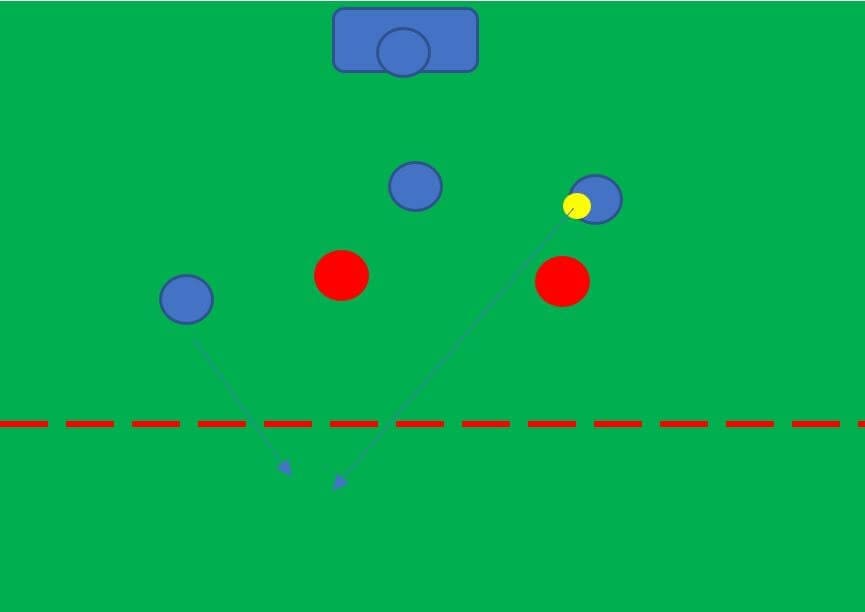

This next practice is unopposed which isn’t something I do too often but in this case I think is useful for developing what can be a complex topic in football. This practice aims to gain repetitions for players to rotate with their teammates and receive in a space previously occupied by a teammate, and then potentially pass to that teammate for a third man pass. We can see an example here with the teams of three shown, the passer has to play the ball into a square occupied by a teammate. That first teammate must then vacate the space, and another teammate should move in to receive. There is then a possibility for a third man pass.

Other uses of this particular set up could be to arrive into space to receive, so the player receiving has to receive the ball in a different zone ahead of them, or could be used to improve awareness of space by creating the rule of only allowing one player per square from either of the teams.

Opposition could also be added by adding a pressing player onto each team of three to try and disrupt the patterns slightly, or after this practice, players could go into a match with constraints which enable the movements practiced, for example, a point for a third man pass. Again, there are some obvious links between this practice and the first practice, so even these could perhaps be paired together in a session. Once players understand the concept, taking away the squares would also be beneficial, as you don’t get these in a real game.

Emptying and arriving into space & forward movements

“Many coaches tend to require central defenders to back off after playing the ball, before being playable again. I was wondering if it’s possible that they could make a run forward after the pass.”

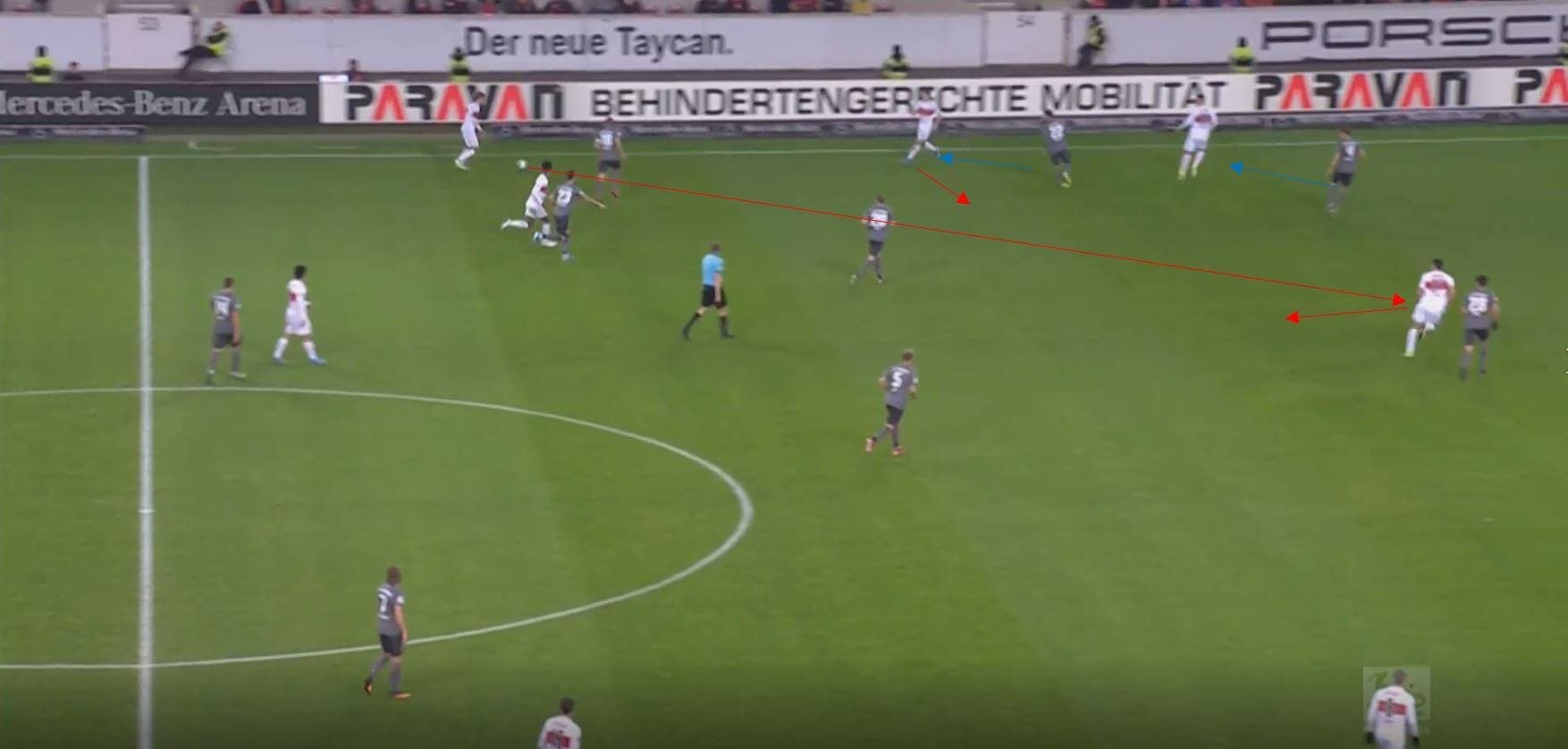

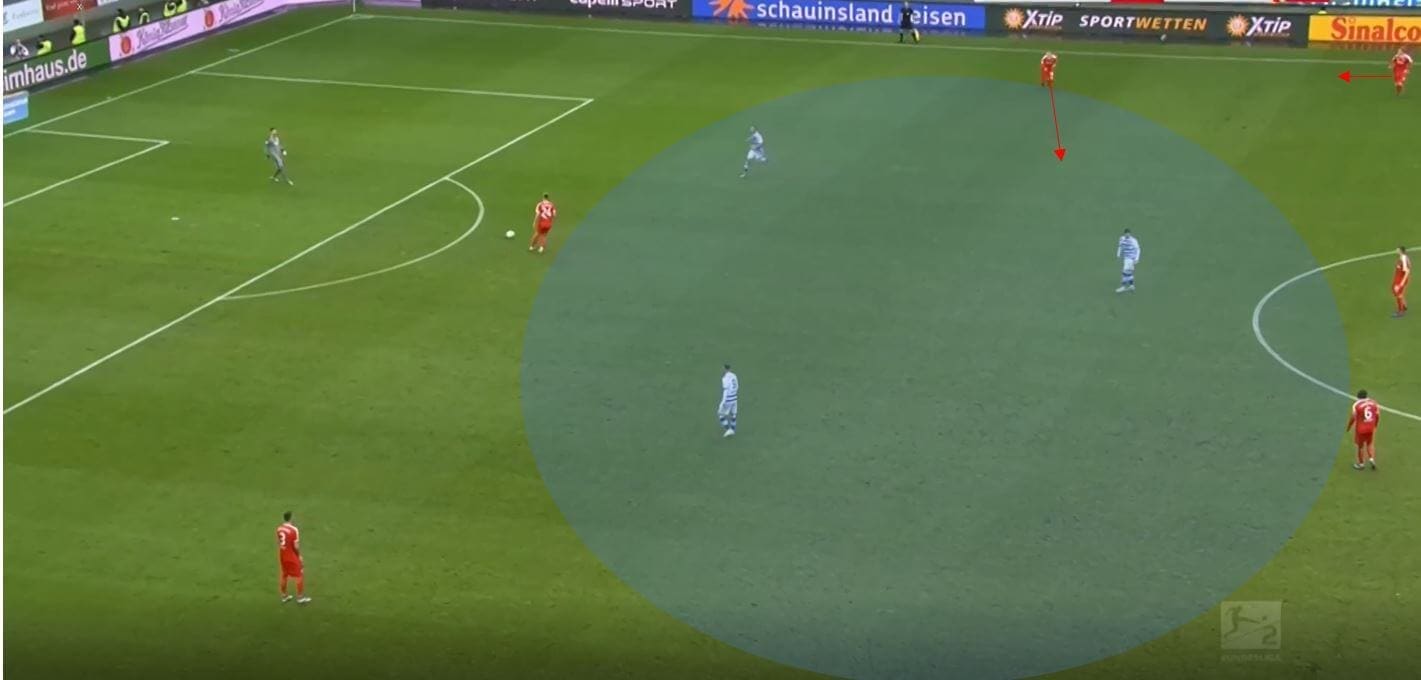

This quote above comes from Tim Walter himself and this concept is certainly one we have seen his teams use to good effect. This next sequence of play from Walter’s Holstein Kiel shows many of the principles we have touched on so far, and shows this key principle of emptying and arriving into space using the centre backs. We can see below the pivot space is emptied, with the midfield taking a higher position and looking to pin the opposition back. Once the player receives the ball, a run is made inside, which is made at this particular time to avoid waiting for the ball in a poor body orientation, which is a vital coaching point in this next section.

Kiel, however, can’t get the ball to the player, and so go back to the goalkeeper. With the wide player having made a run inside, a rotation occurs and width is now provided by a different player who drops. The centre back before the ball has been played wide has already made his forward run.

Therefore the centre back can receive and then combine with that first original wide player, so we have a rotation, a third man pass, and a forward movement from the centre backs all in one play. The massive advantage to building up in this way is the lack of bodies committed back by Kiel, which of course therefore means more bodies are higher up the pitch to create overloads.

Practice ideas

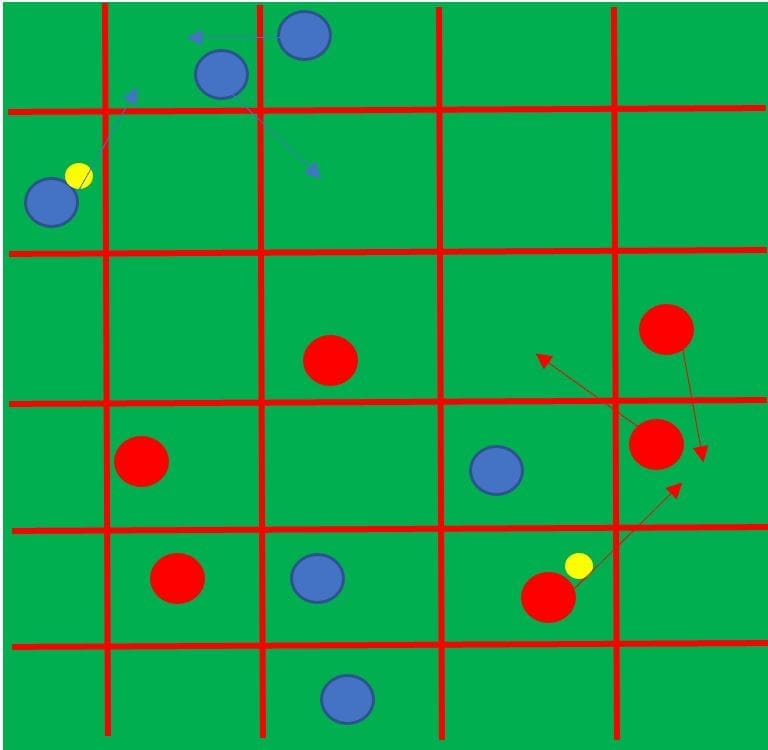

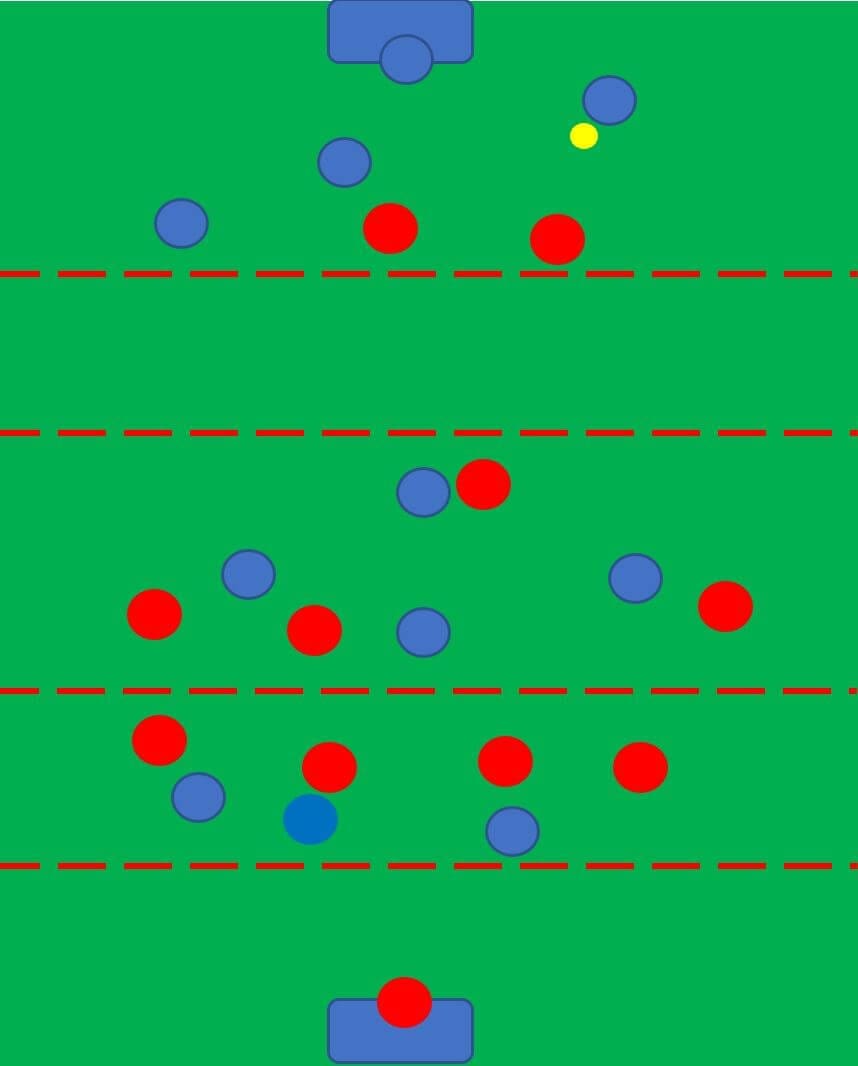

We can see below another practice, which is a phase of play practice involving a 4v2. This seeks to replicate beating the first line of pressure, and a point is scored by the attacking team by receiving the ball on the run into the endzone. The ball cannot be dribbled out into the endzone for a point, and also can’t be passed into a player who is waiting to receive, as this gives poor body orientation for that player in a game realistic situation and harms their ability to progress the ball. Again, decoy runs, rotations and all the previous points covered can be applied here.

Here’s a practice idea for how to coach this particular kind of play in a whole game setting. Numbers can go up to 11v11 but we have five zones, with an extra two zones if you like in the pivot area. Players in the deepest zone cannot dribble out of the area, they have to progress out by receiving the ball on the run into this area, the same as in the previous practice. Initially, the pivot space has to be left unoccupied by both teams, with the midfielders staying deeper and protecting the opposition midfield. Once a player from the deepest zone enters the pivot zone, he can then be pressed by the opposition. This then adds on how to make create passing options for this player and how to take advantage of overloads.

It can also be changed so that the pivot zone can be occupied by the opposition, and therefore the defenders can play the ball out with passes in behind the opposition. Other conditions such as if a defender passes the ball out of the zone and to a teammate, another player from within the deepest zone has to move up to support, which encourages third man runs. Again, after some time, the zones can be removed.

Conclusion

Many of these practices blend into each other and cover many of the same themes and coaching points, which is useful when coaching them to players. Tim Walter is an excellent coach with innovative tactics, and hopefully, these practices designed to coach some of his key philosophies are of use or give you some of your own practice ideas. As with any coaching piece, the context of the delivery of these practice ideas has to be considered, and the way in which it is coached may or probably will change, but as a coach who currently favours a lot of constraints based coaching, this is largely how the sessions have been presented.

Comments