The majority of Europe’s leagues have come to a dramatic conclusion over the past week, with some even drawing to a close this very weekend.

One of those leagues wrapping up over the coming few days is the Danish Superliga.

Denmark’s top-flight has been a mass producer of some of the finest talents on the continent and a handful of superb coaches too such as Brentford’s Thomas Frank and even the Danish national team head coach Kasper Hjulmand.

It may seem like an elementary statement given their historical success in Denmark.

Still, FC Copenhagen are the best side in the Superliga right now, sitting top of the table and on course to retain their title.

The managerial change that occurred very soon into the season made this even more impressive.

Having been assistant manager to Jess Thorup in the previous campaign, 35-year-old Jacob Neestrup is the man leading the Danish giants to glory this time around after Thorup was dismissed following a rough start to the campaign.

But there is much more to The Lions’ success than having excellent players and a lovely blend of youth and experience.

Neestrup’s tactical flexibility this season has made for really fun viewing if you are a tactics nerd like us.

This tactical analysis piece will deconstruct the most intriguing elements of Neestrup’s game model with the fourteen-time champions to understand why they are on course for back-to-back titles.

As a disclaimer, it’s worth noting that Copenhagen have been massively successful from set-pieces this season but this was dissected in-depth in a recent set-piece analysis on the TFA site and so we will focus solely on their tactics in and out of possession for this one.

Jacob Neestrup pressing Tactics

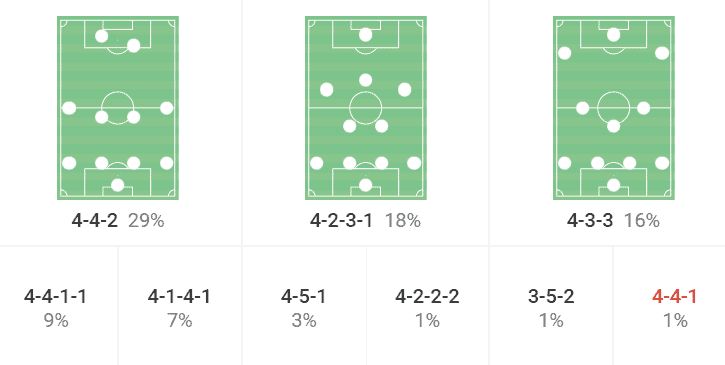

Before taking a look at Jacob Neestrup’s tactics this season, it’s important to note Neestrup’s formation choice in games.

During his stint as the number two to Thorup in the previous campaign, Copenhagen rotated through a plethora of formations.

The most prominent structure was the 4-4-2 and the 4-2-3-1 which are one and the same.

However, Thorup had no qualms about using a shape that the team weren’t overly familiar with in games, whether this be a 3-5-2 or even a 4-2-2-2.

Under Neestrup, there has been a little more consistency in the formation selection.

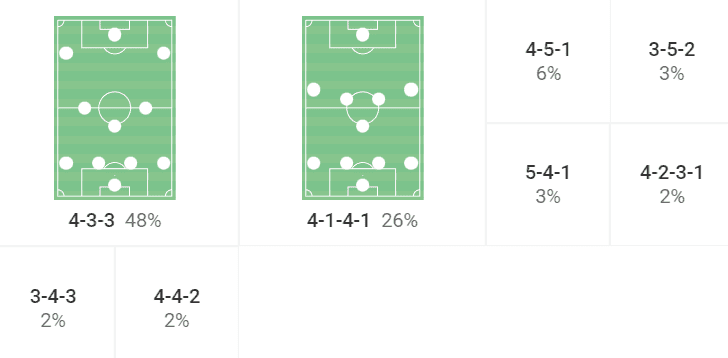

The 35-year-old has a preference for the 4-3-3 which has been deployed in 80 percent of the Danish giant’s games this season in all competitions – this number includes the 4-1-4-1 and 4-5-1.

Interestingly, back three formations are more prominent too under the latest head coach.

The signing of centre-back David Vavro from Lazio was perhaps the greatest reason behind this alongside having the versatility of Kevin Diks who can play as a fullback and a central defender, offering the boss flexibility to switch between a four and a three at the back.

Nevertheless, formations only give the coaches and players pages to work within, it doesn’t write the story for them.

One of the most interesting elements of Copenhagen’s tactical set-up under Neestrup is their pressing.

There isn’t anything unconventional about how Copenhagen press.

This isn’t Leeds United circa 2020, but their press is still highly effective and aggressive.

This season, Copenhagen boast the fourth-lowest PPDA in the Danish Superliga with 11.09 and the fourth-highest challenge intensity at 5.7.

These numbers may not seem amazing, but the metrics don’t tell the full story.

The Lions’ press is very aggressive, but the PPDA is relatively high compared to some of Europe’s most intense pressing teams like Bayern, Barcelona and Brighton.

Why?

Copenhagen are instructed to drop off initially.

The team defends in a mid-to-high block instead of a high block.

The difference between the two is that, with the former, the first line of pressure practically skips the opposition’s build-up phase, positioning themselves to start the press roughly around the very start of the final third.

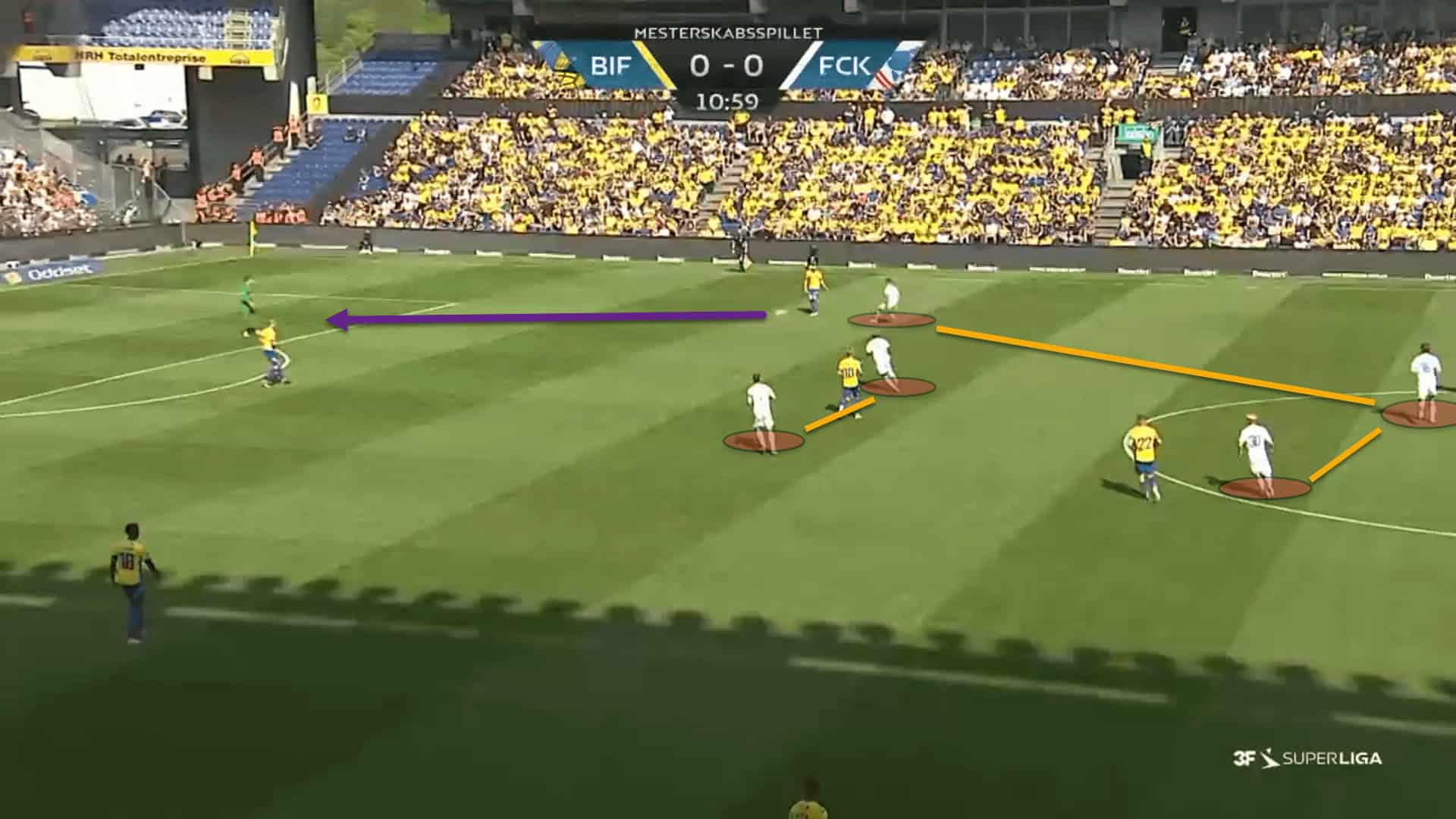

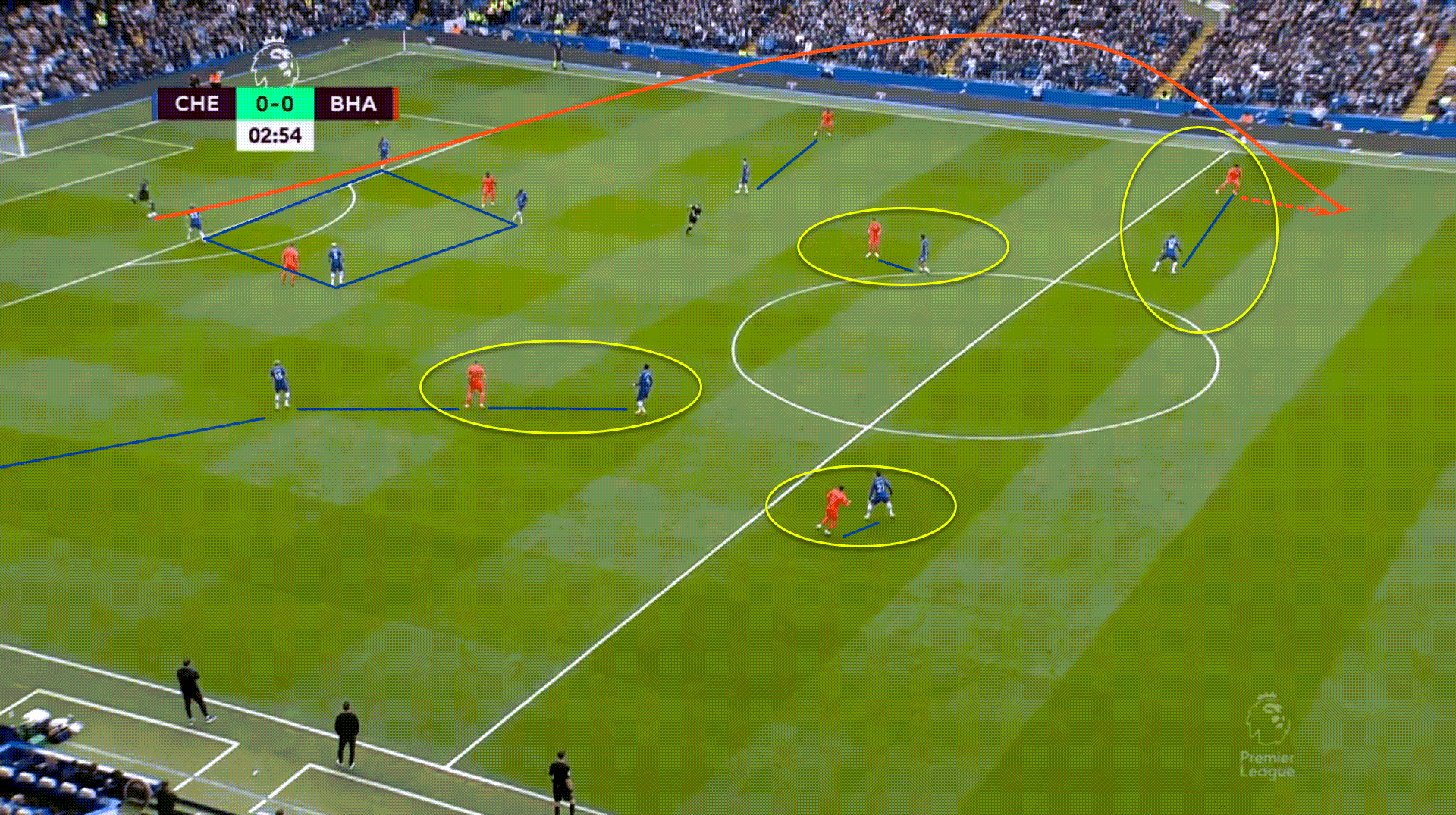

As can be seen from the previous example against Brøndby, Copenhagen’s first line of pressure was sitting off the backline instead of pressing them and was blocking the passing lane into the Brøndby double-pivot.

This allowed the attacking side’s goalkeeper to advance well up the pitch to create a 3v2 against Copenhagen’s front two.

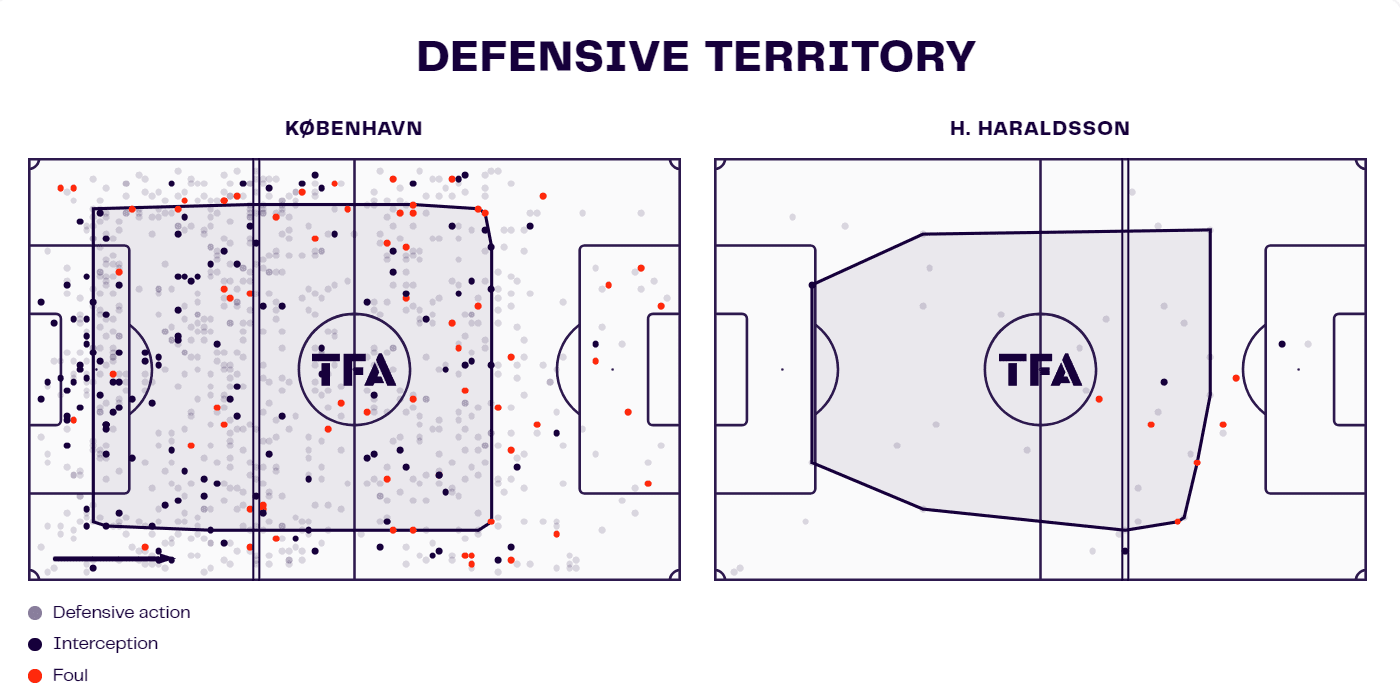

FC Copenhagen Defensive Territory

By comparing the average height of Copenhagen’s defensive line during Neestrup’s reign at Parken with the average line of engagement of Hákon Arnar Haraldsson – who has played as the frontman more than any other player over the last 10 games – we can get quite a clear picture of the compactness of the team’s block and roughly where the press begins.

The objective of the press is to force a backward pass.

This is a trigger for Copenhagen to bring the lines up and move into a full high press.

This backward pass is normally instigated by the first line of pressure or can also be forced by a player from the midfield.

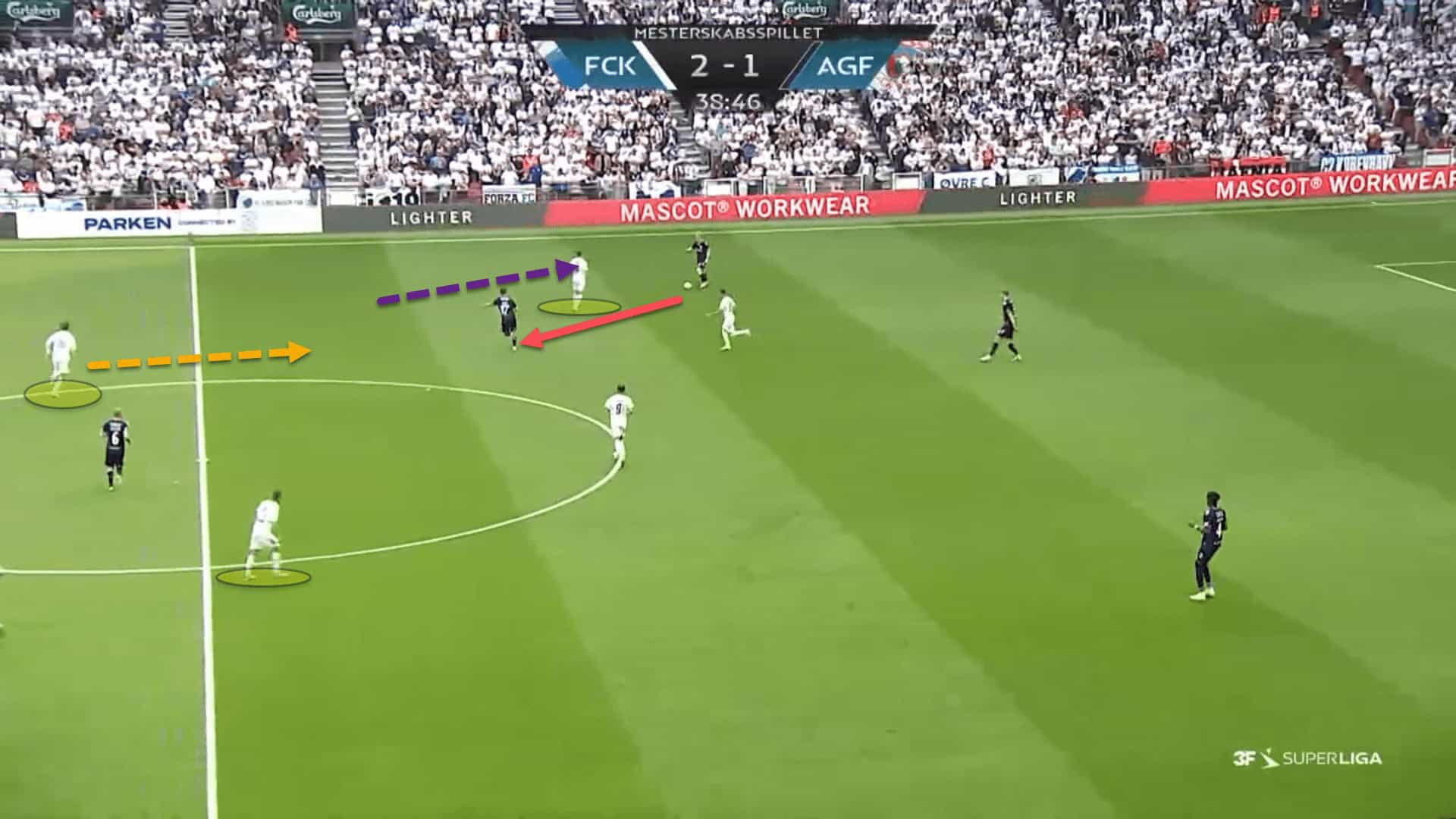

For instance, in this game against Brøndby, the Danish champions were defending in a 5-3-2 shape.

As the front two were closing the passing lanes to the opponent’s double-pivot, Copenhagen’s wide central midfielders would press the backline from out to in.

As the central passing lanes were cut off and the ball carrier couldn’t play wide because of the pressing player’s run, he had to move it back to the keeper.

Job done!

Using the wide central midfielder in a 5-3-2 to press the backline has sometimes caused problems for Copenhagen when Neestrup has deployed this structure, especially if the single pivot is unable to cover for them in time.

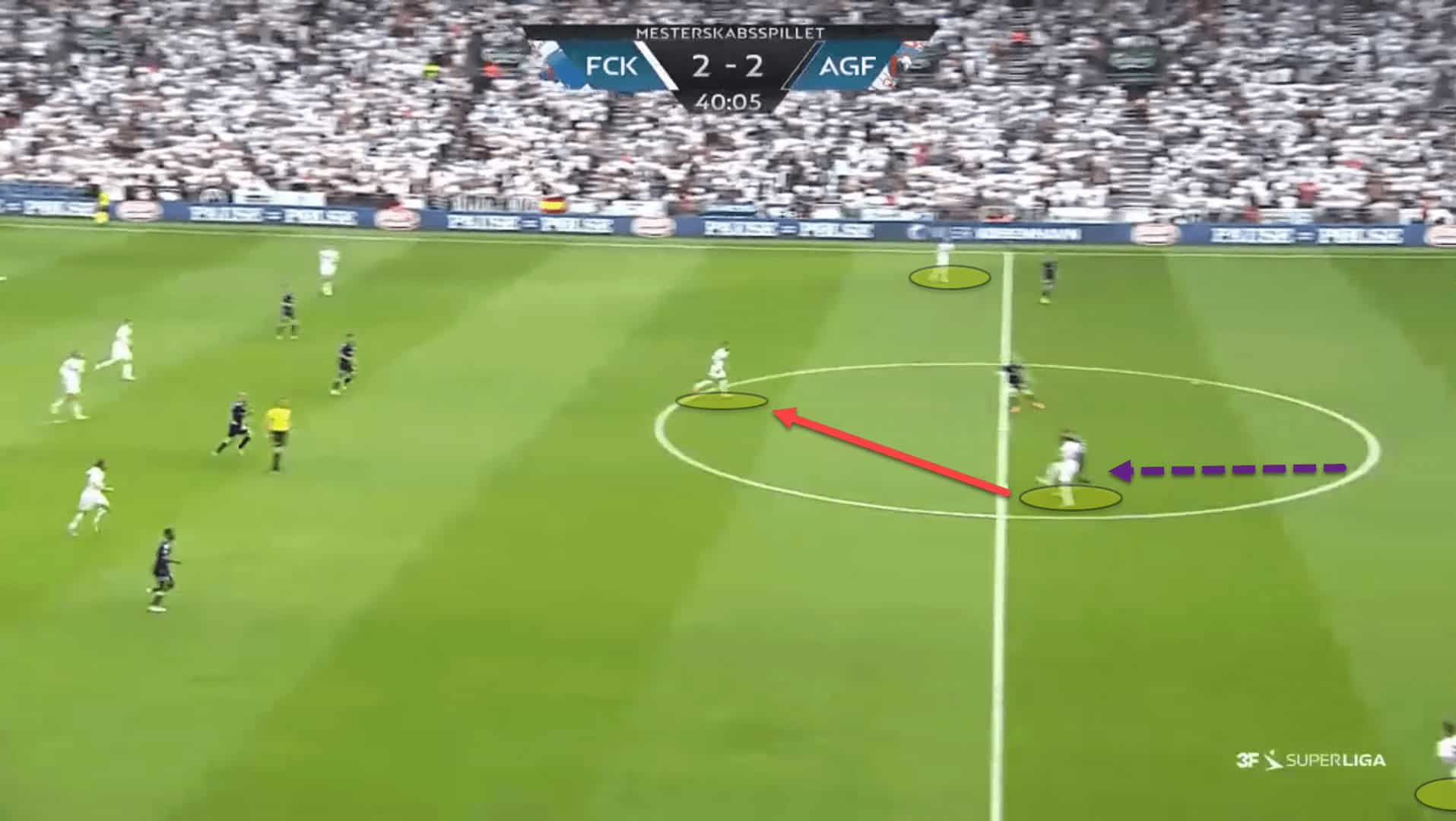

For instance, here, the left central midfielder, Ísak Bergmann Jóhannesson, had stepped up to press the opposition’s ball carrier in the backline.

The number ‘6’ tried to get across in time to cover for him but couldn’t which allowed easy progression for the attacking side.

Nonetheless, once the mid-to-high block is successful and the ball is played backwards, Copenhagen step up as a unit and begin to press intensely, looking to regain possession as high up the pitch as possible.

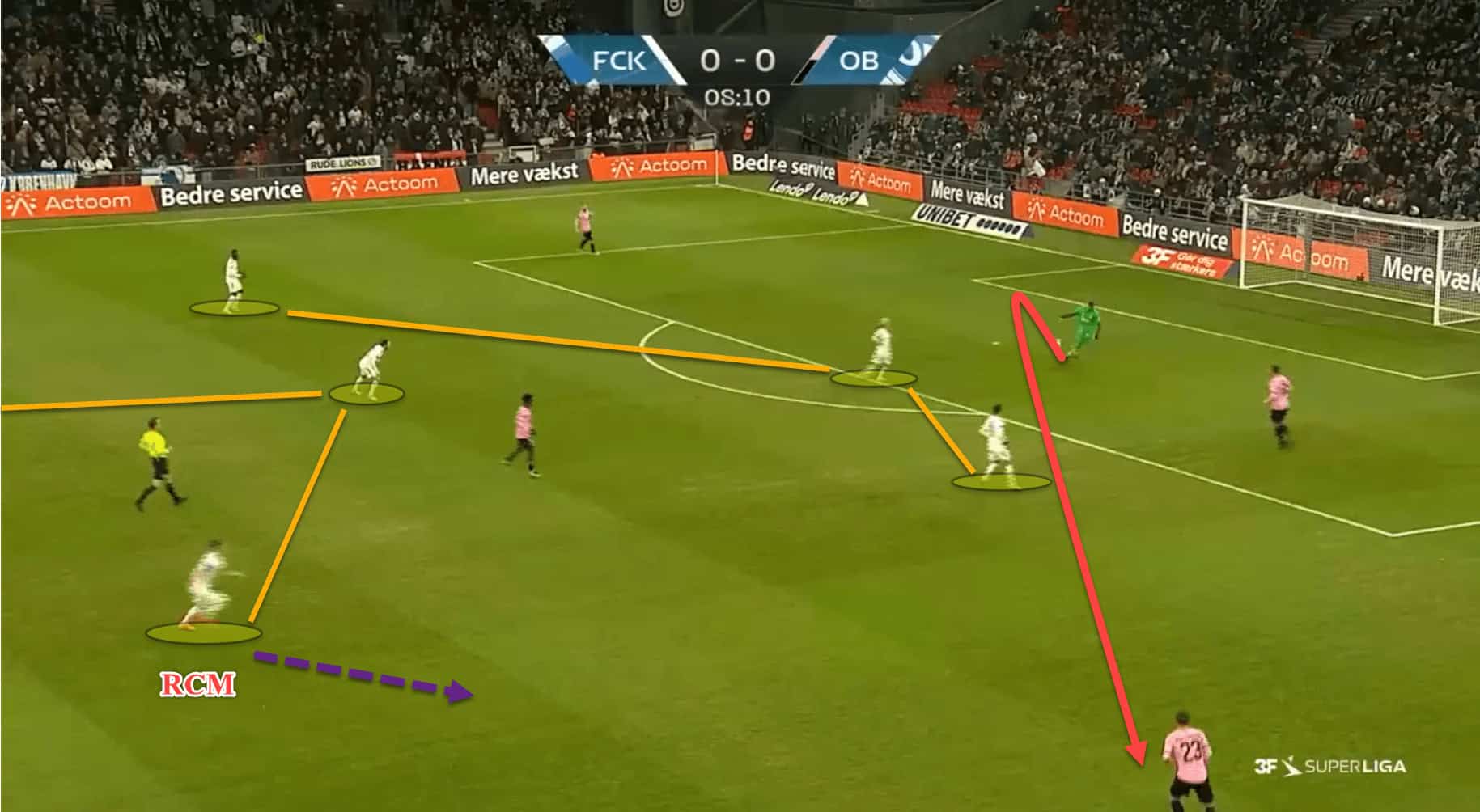

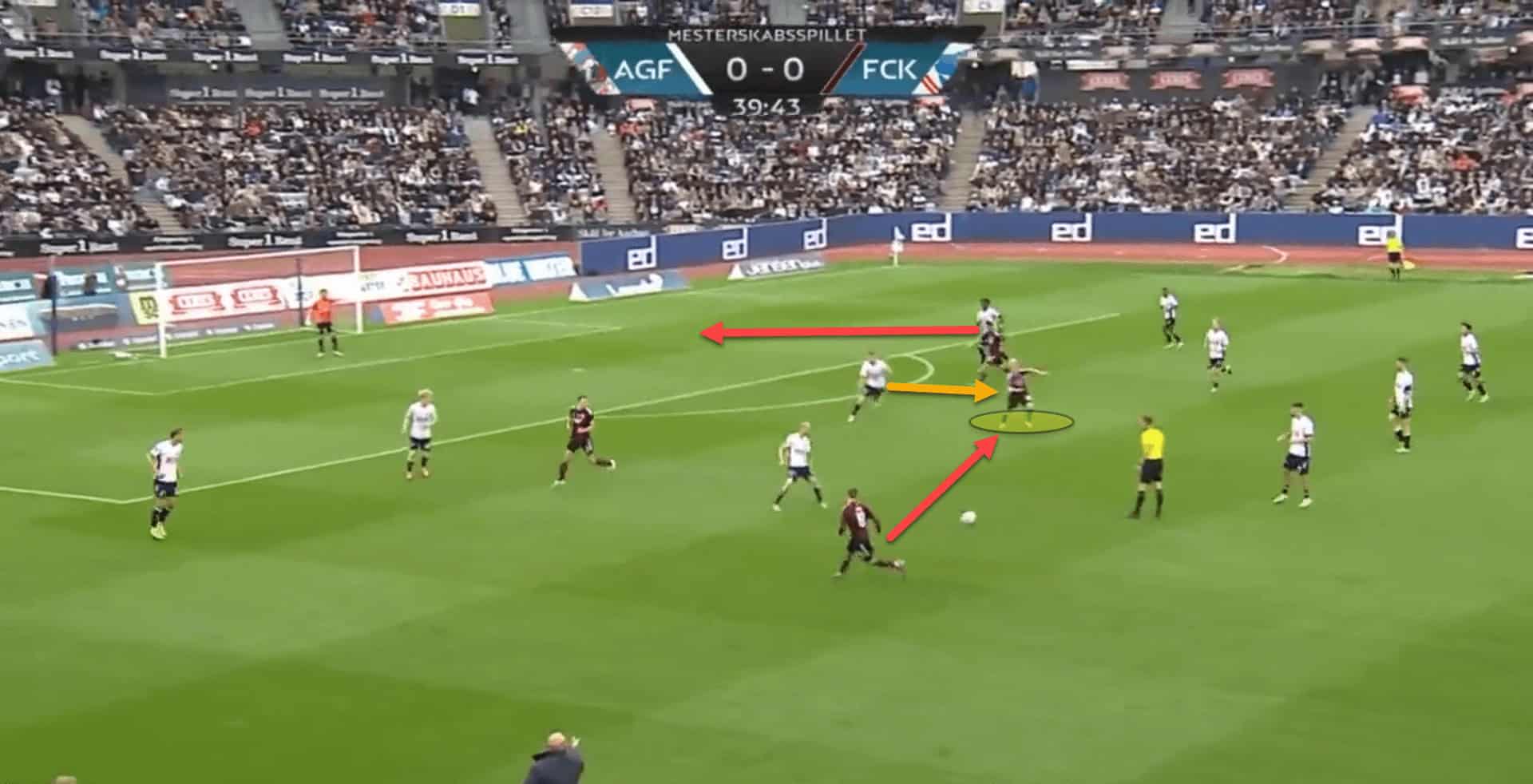

Neestrup instructs his players to cut off any access through the centre of the pitch for the opposition and force them to play wide into an uncomfortable area.

There is no sideways passing option for the OB goalkeeper who is under pressure from Copenhagen’s centre-forward.

The wingers are pushed up onto the centre-backs, while the three central midfielders are man-marking in the middle of the pitch, leaving only the fullbacks free.

But it’s important to highlight the positioning of Copenhagen’s right central midfielder.

He is preparing to run out to close down the fullback as he knew that this was the pass that the goalkeeper would choose.

This is all part of Neestrup’s trap.

Once the ball is moved to the flanks, Copenhagen go man-for-man and aggressively press the opposition in such a tight area to regain possession.

Going back to an point earlier in this section, Copenhagen’s PPDA is still relatively high because they allow the opposition to play numerous passes, circulating around the back, but once the backwards pass is made, The Lions hunt their prey.

This pressing has been the killer of many this season and is incredibly difficult to break out of given that it lures the attacking team into a false sense of security before causing panic in the blink of an eye.

This is a credit to the head coach, his staff and the players.

Playing direct through the press

Copenhagen’s build-up play is incredibly vertical.

This doesn’t mean that Neestrup instructs his backline and goalkeeper to kick it long.

In fact, Copenhagen have registered the second-lowest number of long balls per 90 in the Danish Superliga this season with 40.88, behind Silkeborg.

However, the champions are excellent at baiting the opposition to press them in the final third before playing through the pressure rather than around or over it.

Normally six outfield players will position themselves in the first third of the pitch.

In most cases, the opposition will match these, especially when using a 4-4-2 to press, as the previous screenshot displayed.

But by using the goalkeeper as an extra man in the build-up, Copenhagen have 7v6 in this phase, or numerical superiority as the cool kids call it.

This creates a 4v4 situation against the opposition’s defensive line.

This is quite similar to Brighton’s setup under Roberto De Zerbi.

There is no stalling on the ball, though.

In this sense, they differ from Roberto De Zerbi’s Brighton.

However, Copenhagen do wait until a passing lane opens up behind the opposition’s midfield line to try and reach the four players who are positioned the highest on the pitch.

This is where personnel comes into play.

Firstly, the goalkeeper needs to be comfortable in possession.

Kamil Grabara has been the man trusted with protecting the net and starting Copenhagen’s attacks under Jacob Neestrup’s coaching style.

The former Liverpool player boasts a passing accuracy of just under 85 percent this season and even makes 1.7 passes to the final third per 90.

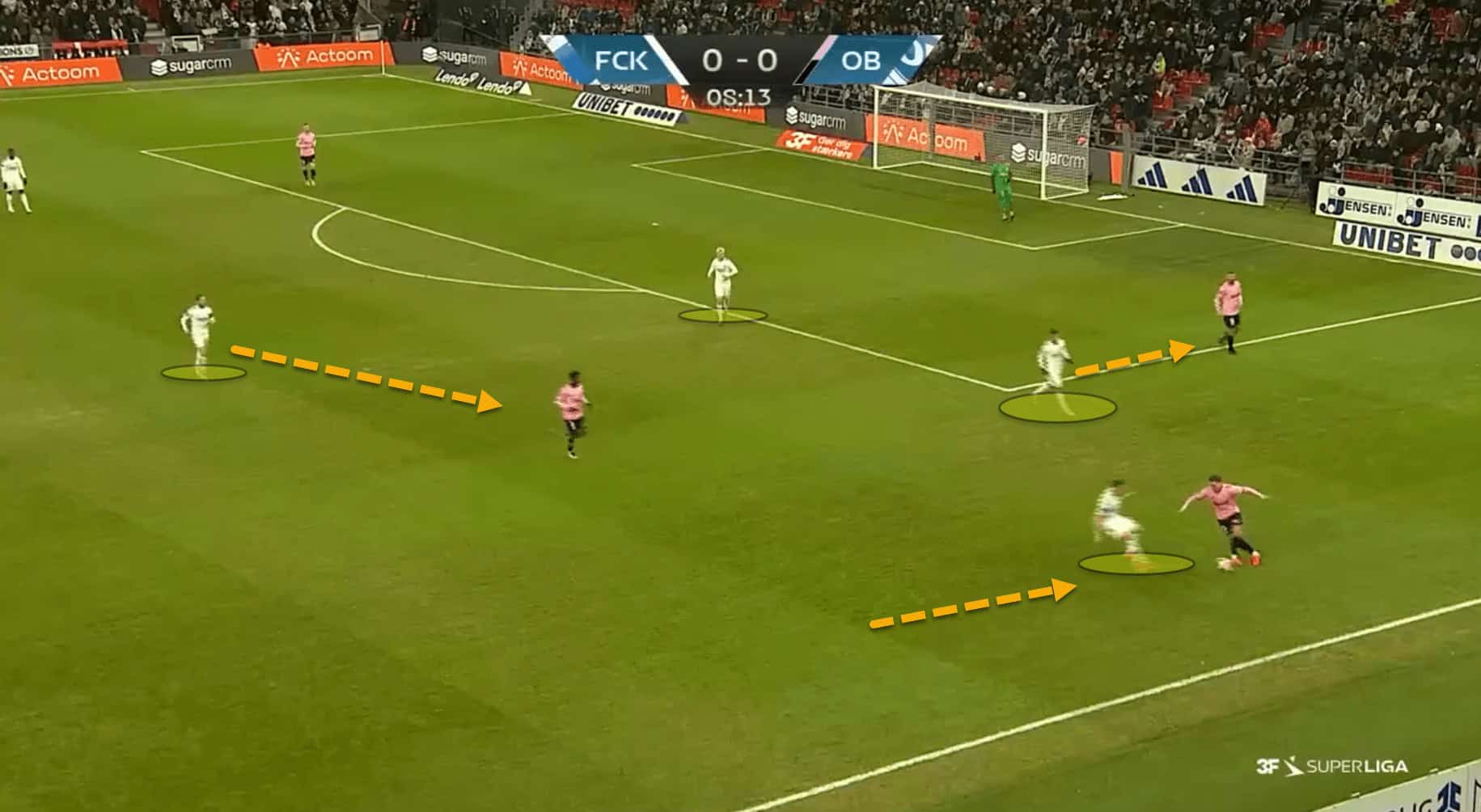

When the right time comes and the passing lane is open, Grabara’s job is to split the opposition’s midfield and frontline, playing directly to the feet of the front four.

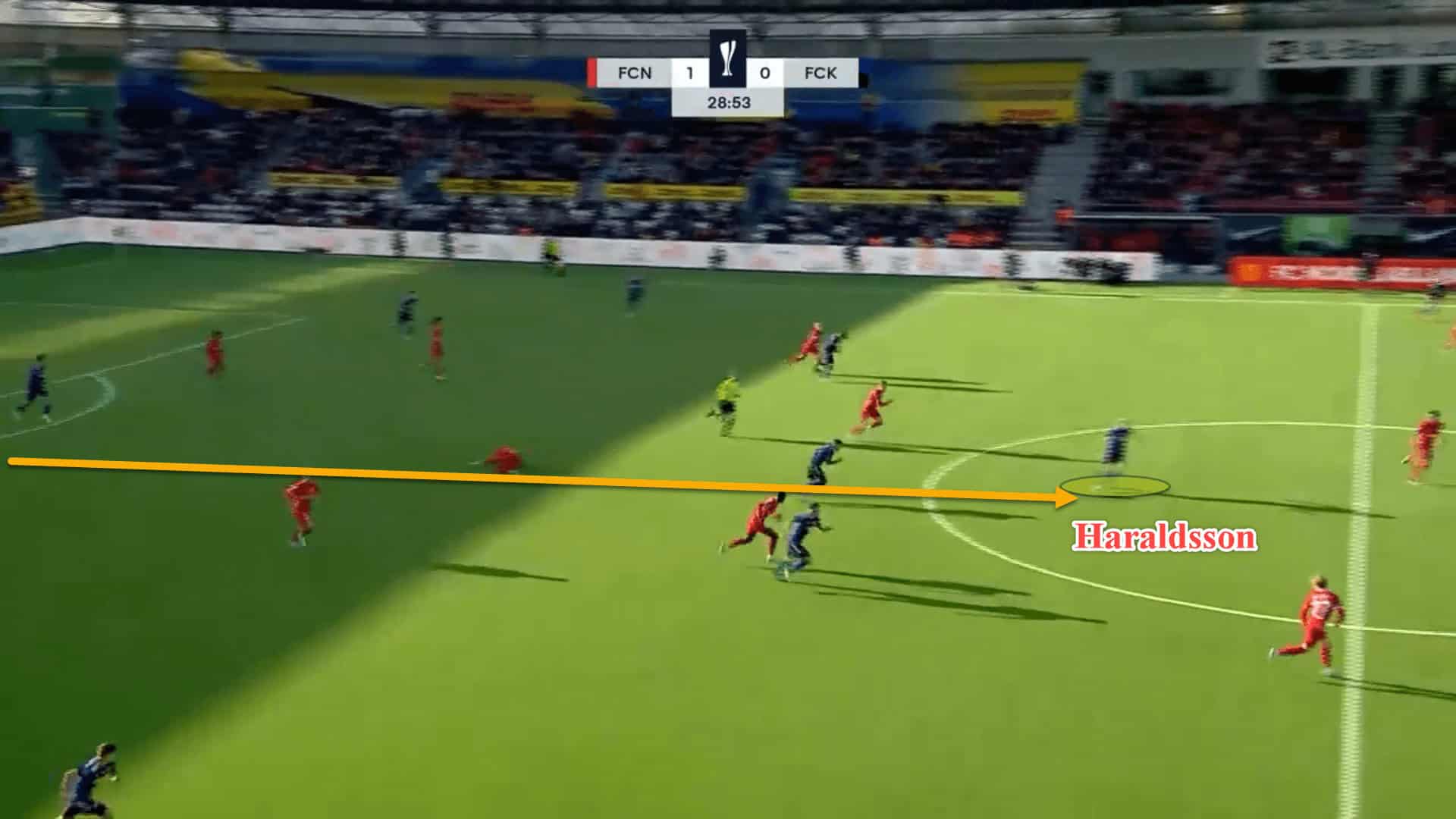

These two screenshots were perfect examples of times this has worked well for Copenhagen.

The ball was played directly to the foot of the receiver, bypassing six pressing players in the meantime.

This season, The Lions have boasted 70.73 progressive passes per 90 which is the fifth-most in Denmark’s top-flight division.

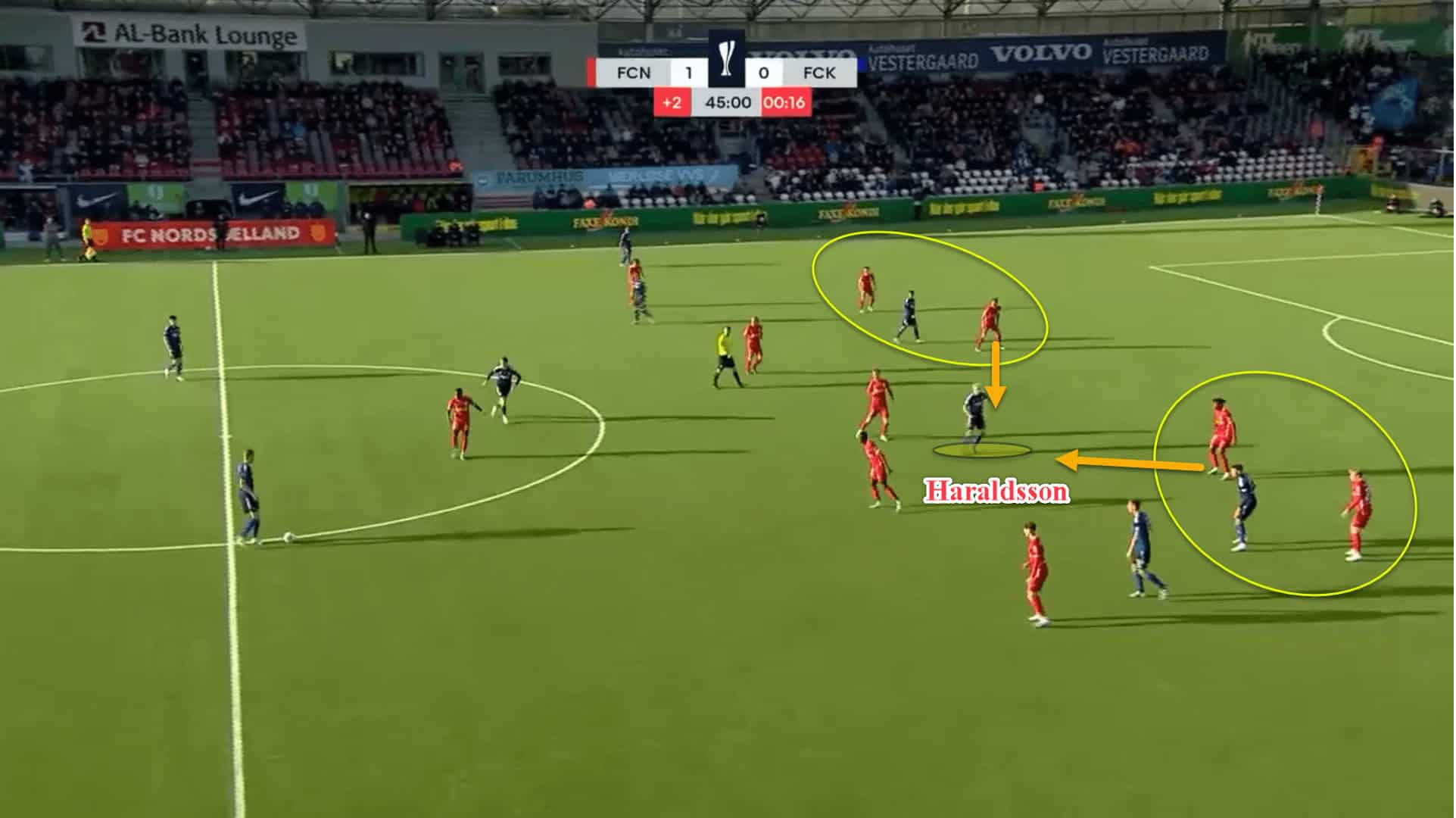

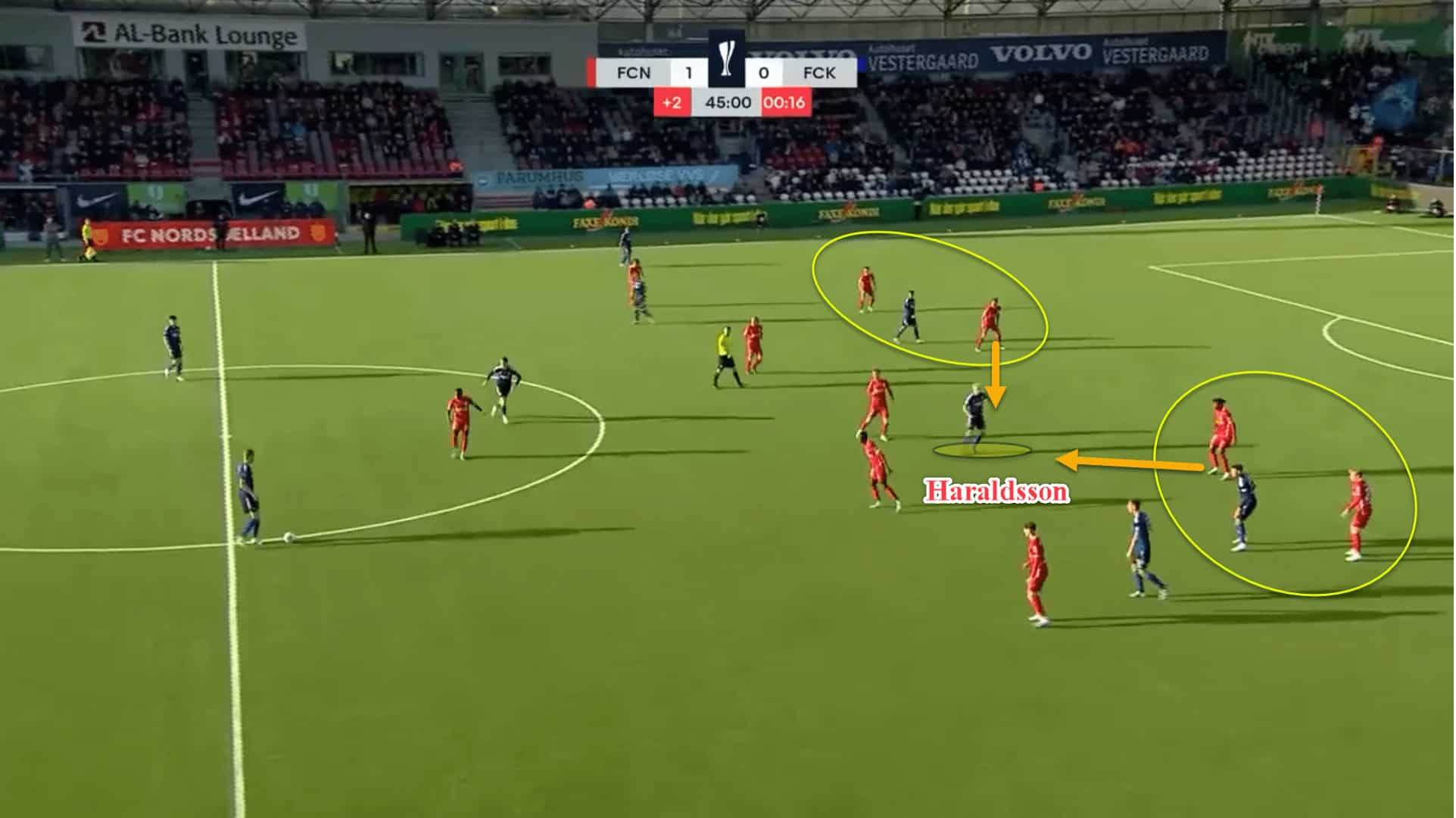

This can also be helped by having a false ‘9’ up front which is a choice that Neestrup has made quite regularly with Haraldsson.

The Iceland international is naturally a central midfielder but has been used at the tip of Copenhagen’s 4-3-3 a lot over the course of the 2022/23 campaign, rotating the position with the likes of Andreas Cornelius, Jordan Larsson, Diogo Gonçalves and even Viktor Claesson.

Having Haraldsson as a false ‘9’ dropping short allows the goalkeeper and the backline to know that he is comfortable receiving under pressure and will be able to use runners around him to take advantage of the 4v4 situation against the backline, or that he can even turn on the ball and drive forward.

In this instance, Haraldsson realised that there was nobody around him and simply turned and ran forward before eventually slipping in a faster, more clinical player to try and convert the opportunity.

But it’s not just from the build-up phase where Copenhagen look to create a numerical battle versus the opposition’s defence or even use a false ‘9’.

Plus one up top

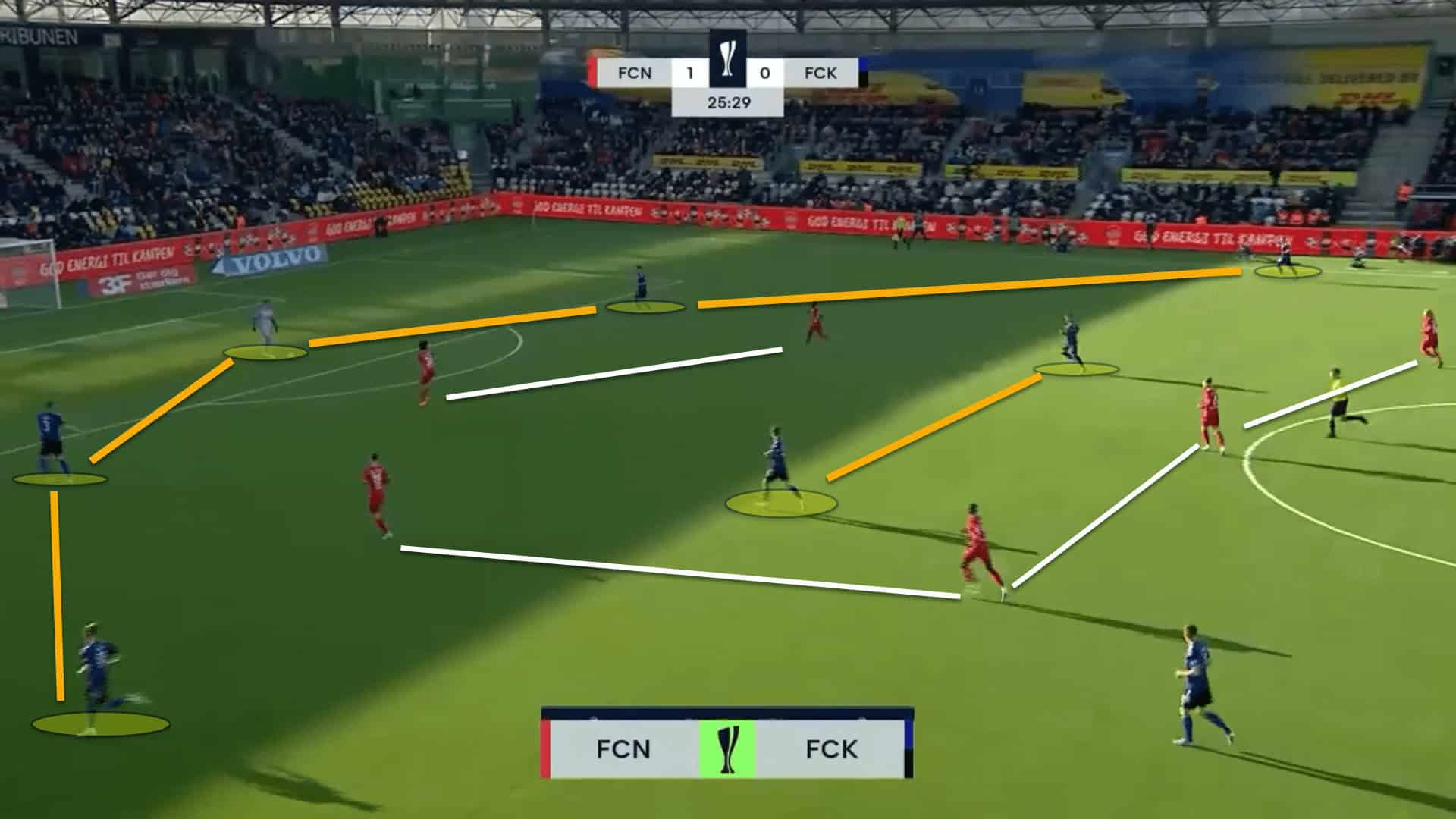

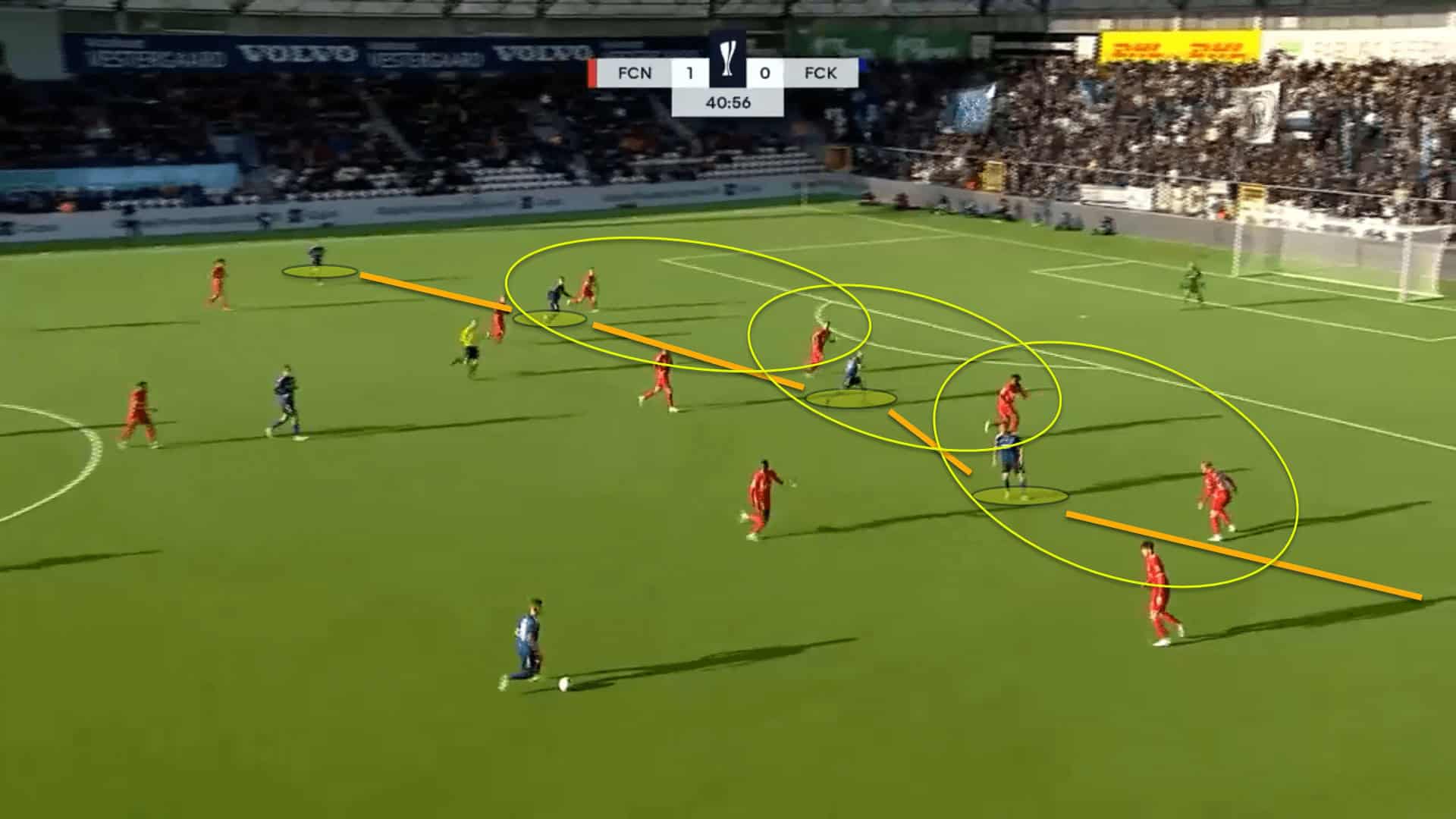

When looking to break down an opposition defensive block, Neestrup wants to have numerical superiority against the backline, while also having at least three players between the lines, occupying each channel of the opponent’s defence.

Typically, there are five players on the last line to generate a 5v4 numerical overload with three positioned centrally.

The other two are holding the width on the flanks to stretch the defence.

In this sense, Copenhagen adhere to the principles of positional play by having at least one player in the five horizontal channels across the pitch.

The composition of this line of five isn’t fixed.

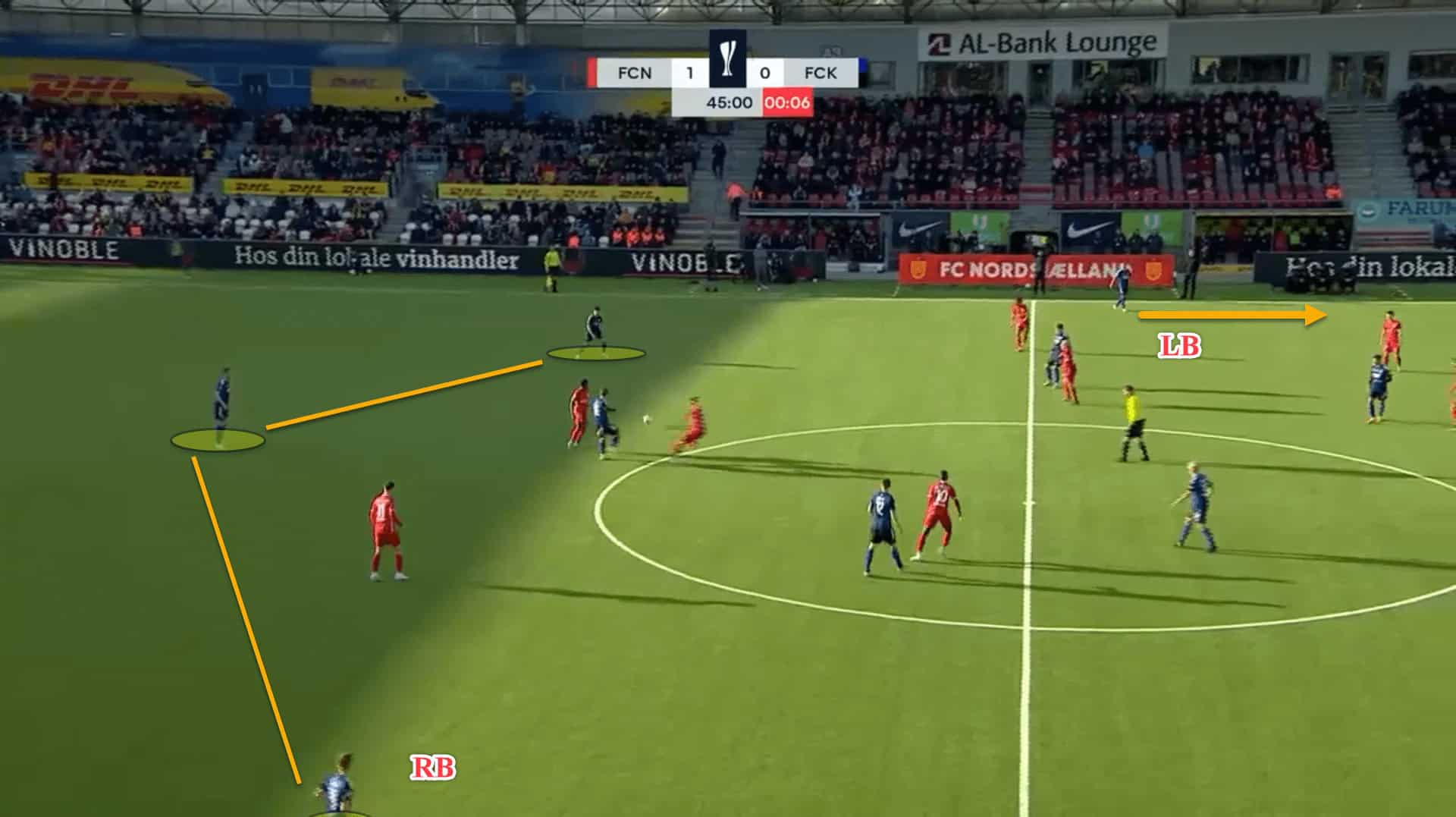

Sometimes both fullbacks will get forward, allowing the wingers to invert next to the centre-forward to create the frontline, but one of the central midfielders can also push into the halfspace too while a fullback stays back to create a back three with the other two central defenders.

Here, the right-back has tucked inside, forming a back three with the central defenders but the left-back has advanced forward on the far side.

As a result, the left-back and right winger are holding the width while the left winger, striker and central midfielder are positioned between the lines.

Copenhagen don’t really look to cross the ball all that much.

Despite averaging more possession than any other side in Denmark’s top-flight with 56.2 percent per game, the champions don’t cross the ball a whole lot.

This season, Copenhagen have averaged merely 13.66 crosses per 90 which is the fourth-lowest rate in the Superliga.

Crosses are still an option for Copenhagen to break down a defence but one that they don’t rely on as crosses, particularly high crosses, are normally low percentage chances.

Instead, Neestrup likes to play between the lines, using the overload of the backline to the team’s advantage.

More commonly, the use of Haraldsson as the false ‘9’ allows the team to pull defenders out of position.

Here, the centre-backs are in a tricky position, unsure of whether to step out to Haraldsson or stay in position and risk having the Icelandic attacker receive in space which could potentially have more dire repercussions.

This is called ‘gravity’ in basketball – when a lone player has the ability to attract two or more defenders through their sheer presence alone.

Haraldsson’s deeper positioning as the false ‘9’ asks a lot of questions for the opposition’s backline and can drag defenders out of position, allowing the wingers to make inverted runs in behind.

Copenhagen’s keenness to break down the opposition in the central areas, including from the esteemed Zone 14, is admirable and makes them incredibly fun to watch.

Conclusion

There are a lot of aspects to FC København’s game model which make the Danish giants so successful but this article would have gone on forever had we analysed every facet of their tactics.

However, we’ve picked out three aspects of Neestrup’s setup that are the most interesting – to us, at least.

Having a false ‘9’ in your team is, and always will be, one of the most fun components of any side, whether it be Roberto Firmino at Liverpool, Lionel Messi at Barcelona or Haraldsson at FCK, while the young head coach has also managed to take some inspiration from De Zerbi and Pep Guardiola along the way.

It will be very interesting to see how the 35-year-old evolves the team tactically next season too and during their potential European campaign.

Comments