The whistle blew at Goodison Park on Saturday afternoon to signal the end of a cagey 90 minutes of football.

A loud cheer erupted from the home fans as Everton were lifted out of the relegation zone. Relief oozed from the stands and onto the pitch. The job wasn’t complete, far from it. However, the Toffees are now in a great position to climb as far away from the deadly drop zone as possible.

Unfortunately, a different feeling spilled out of the Bullens Road Stand on the east side of the ground. Leeds United had made way for Sean Dyche’s men. A 1-0 defeat put the Lilywhites second from bottom, with only a point separating themselves and the foot of the table.

Something had to change and change fast. It was more than a week since Jesse Marsch had been relieved from his post. Michael Skubala took temporary charge of the team, and while Leeds made a great account of themselves in a double-header versus bitter rivals Manchester United, only a point from a possible nine was collected during the interim boss’ spell in charge.

Approaches for West Brom boss Carlos Corberán and Rayo Vallecano head coach Andoni Iraola were met with swift rejections. But Leeds’ divisive Sporting Director Victor Orta had one more trick up his sleeve.

An unlikely candidate emerged from the woods and three days after the defeat to Everton, the former Watford and Valencia manager Javi Gracia was appointed to the dugout at Elland Road.

This tactical analysis piece will analyse the tactics that Leeds supporters can expect from their side during the Spaniard’s reign.

Gracia’s favoured formation?

It was at Vicarage Road where Gracia made a name for himself in English football. He was largely an unheard-of coach in the United Kingdom, having managed clubs such as Rubin Kazan, Málaga and Osasuna before taking over from Marco Silva with the Hornets in January 2018.

His first half-season with Watford was adequate. The London club stayed in the Premier League and ended up in a respectable 14th place.

Nevertheless, it was Gracia’s first full season in charge which made him a memorable coach in the club’s history. The Hornets improved on the previous season by finishing three places higher in 11th, missing out on the top half by two points, rounding off the club’s best campaign in the Premier League era.

But it was the team’s run in the FA Cup which capped off a sumptuous season. Watford reached the final of the historic competition, and while the 6-0 hiding to champions Manchester City felt like someone had sprinkled salt on their cake, it was still a wonderful achievement.

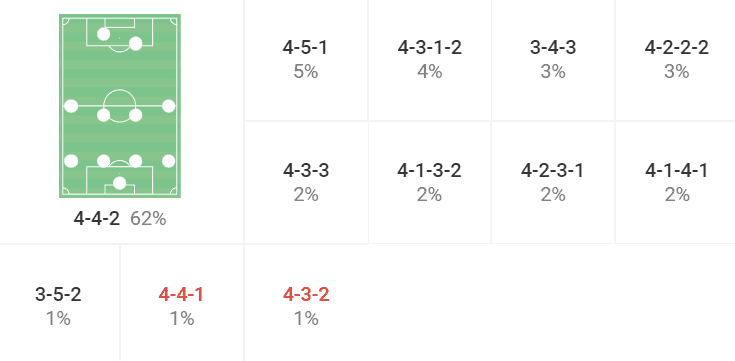

Under the Spanish coach’s tutelage, Watford set up in a relatively simplistic but effective 4-4-2 which merged into a 4-2-2-2 in possession, although we’ll discuss this in greater detail later.

While the 4-4-2 and variations of it were Gracia’s preferred shapes, other formations were utilised during his reign too. In fact, the now-52-year-old wasn’t afraid to make changes when necessary during a game.

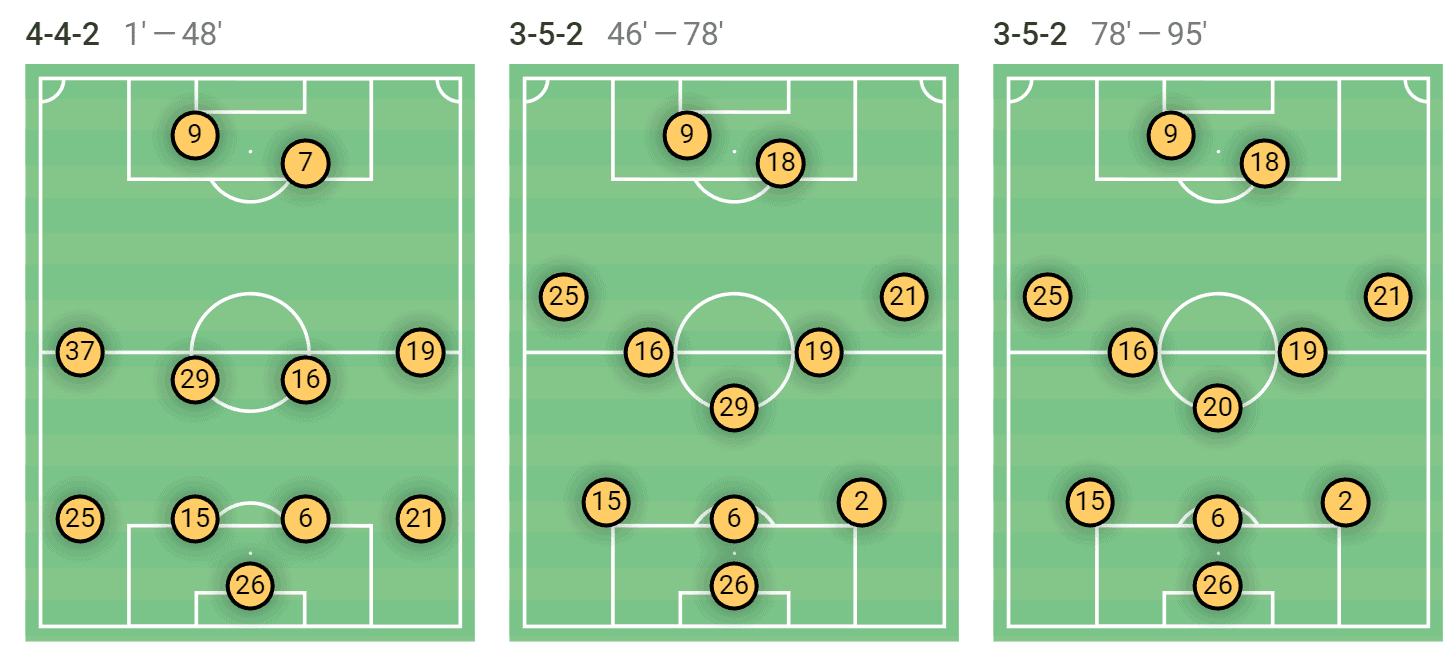

For instance, in a Premier League bout back in April 2019, Watford were level with Fulham at one goal apiece when the referee blew for half-time. The Hornets were struggling against Scott Parker’s 3-4-3 and so changes needed to be made.

Roberto Pereyra (no. 37) and Gerard Deulofeu (no. 7) were taken off by the manager and were replaced by Daryl Janmaat (no. 2) and Andre Gray (no. 18). They weren’t like-for-like replacements. Two attacking players came off and were swapped for a centre-forward and a defender.

Janmaat dropped in as a third centre-back with Gray becoming Troy Deeney’s partner up top. The shape switched from a conventional 4-4-2 to a 3-5-2 for the remainder of the match. Watford eventually won 4-1 and ran riot in the second half, relegating Fulham in the meantime.

Just four days into the 2019/20 season, having lost all four matches, Gracia was dismissed, although perhaps this decision was premature in hindsight considering what unfolded at the conclusion of that campaign.

Nonetheless, Gracia’s next job was back in his home country, taking over at Valencia. A similar path ensued from his time in England.

The Spanish giants underperformed quite a lot compared to their years under Marcelino, but the principles were pretty much the same from the coach as his time in Hertfordshire.

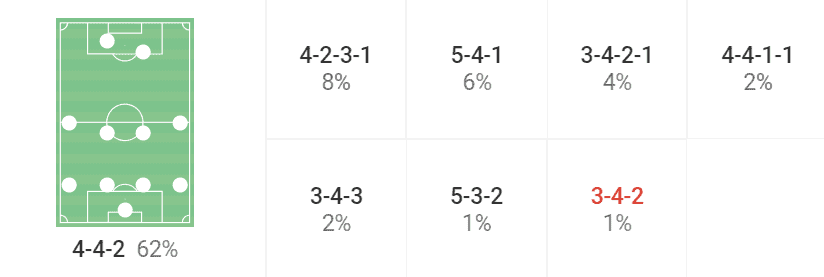

The 4-4-2 was still Gracia’s preferred formation, although there was also a lot of experimentation with other structures, namely the 5-4-1 which he used quite a lot towards the end of his tenure.

It was no surprise that Gracia was dismissed, joining Peter Lim’s long list of victims. But he fell into a nice cushty job, replacing impending Barcelona boss Xavi Hernández at Al-Sadd.

Al-Sadd were already mid-season and looked like favourites to win the title. They did, and so Gracia got to add a nice piece of silverware to his relatively barren trophy cabinet.

Regardless of whether the formations change from club to club, though, Gracia’s playing style has always remained air-tight and consistent.

At Elland Road, it certainly wouldn’t be a shock to see a very 2018/19 Watford-esque 4-4-2 system put in place. Although, the 4-2-3-1 and 4-4-2 have been Leeds’ primary formations this season and so the transition may be a lot smoother than people think.

Nevertheless, formations are a reference point for coaches to implement principles. They do not dictate the side’s principles nor are they fixed and so it’s far more important to analyse how we expect Leeds to play under Gracia rather than remaining fixated on a sequence of numbers which don’t really matter a whole lot anymore in tactical analysis.

Transitions

Upon sacking Marcelo Bielsa, a move which was highly unpopular among large parts of the Leeds United fanbase, it seemed as though appointing a like-for-like successor was impossible.

And so eyebrows were certainly raised when Jesse Marsch was handed the job, a manager programmed by the Red Bull machine, a step in the opposite direction that would rip up the blueprint created by Marcelo during his four years in West Yorkshire.

However, there were actually quite a few reasons why Marsch’s coronation made sense. The American is known for fast attacks and constant pressing.

When all the cogs were turning, Leeds were exceptional in transition under Marsch and had the ability to carve the best defences wide open. As soon as possession was recouped, the objective was to break forward into the channels to runners as fast and effectively as possible.

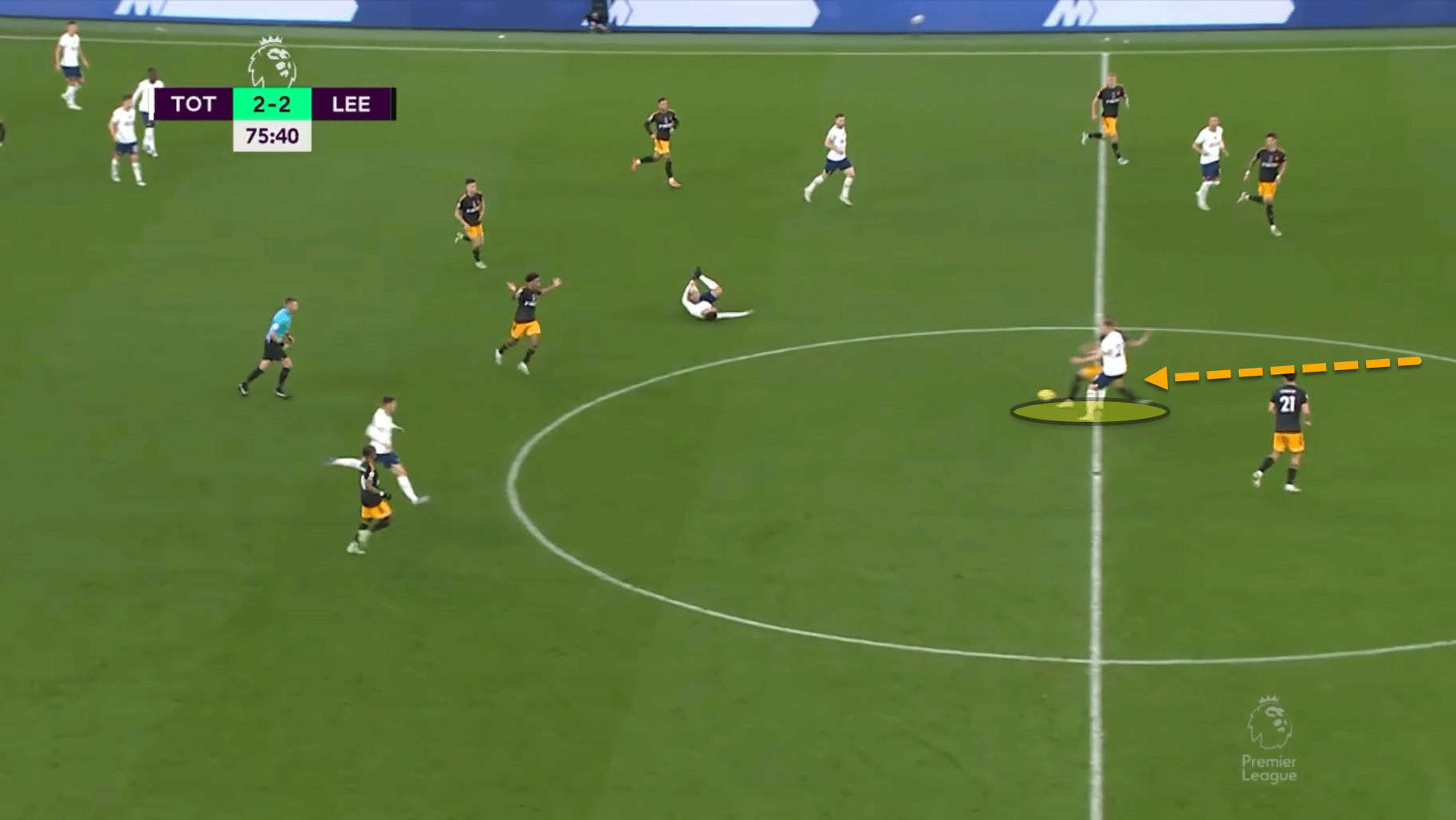

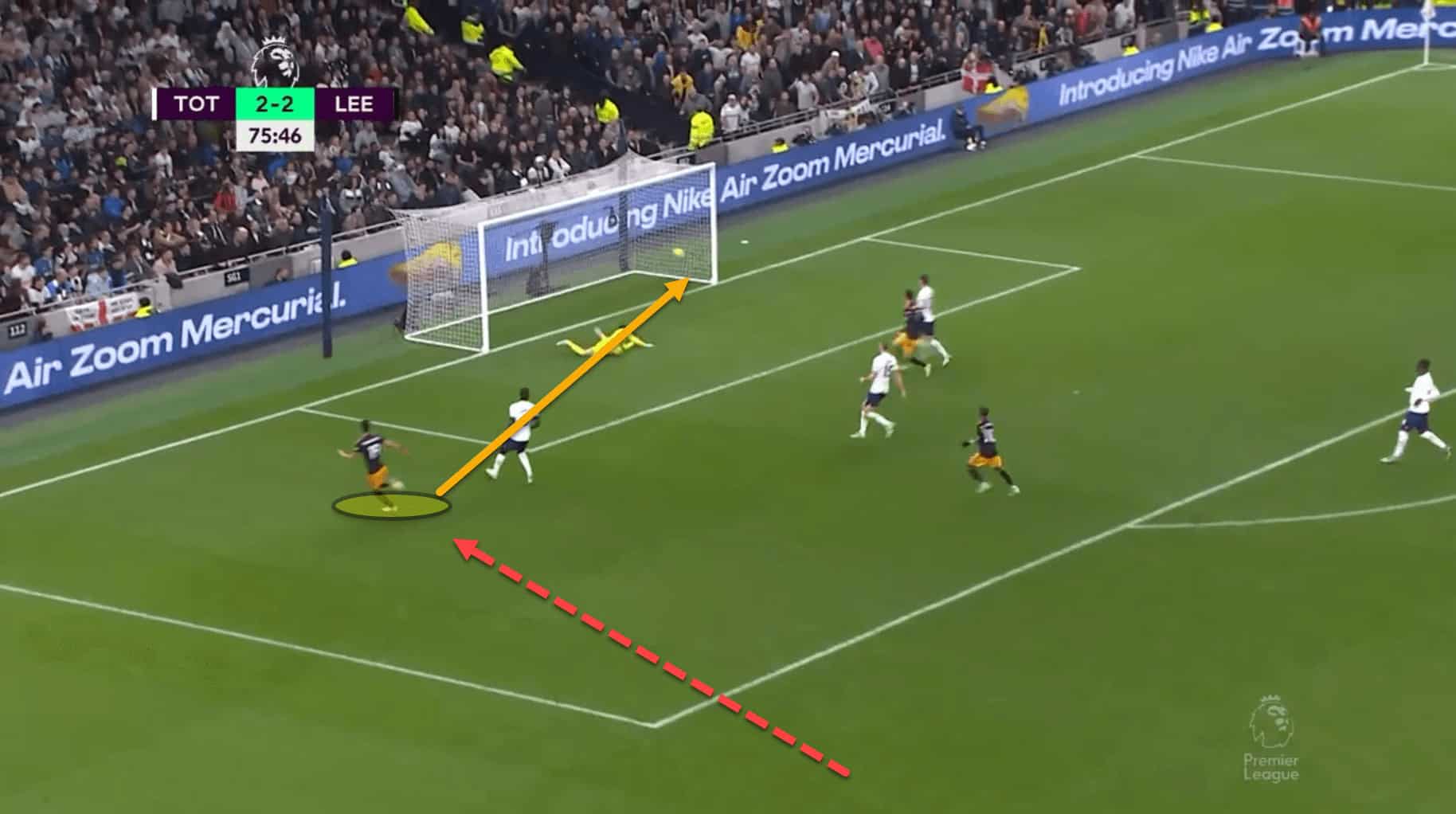

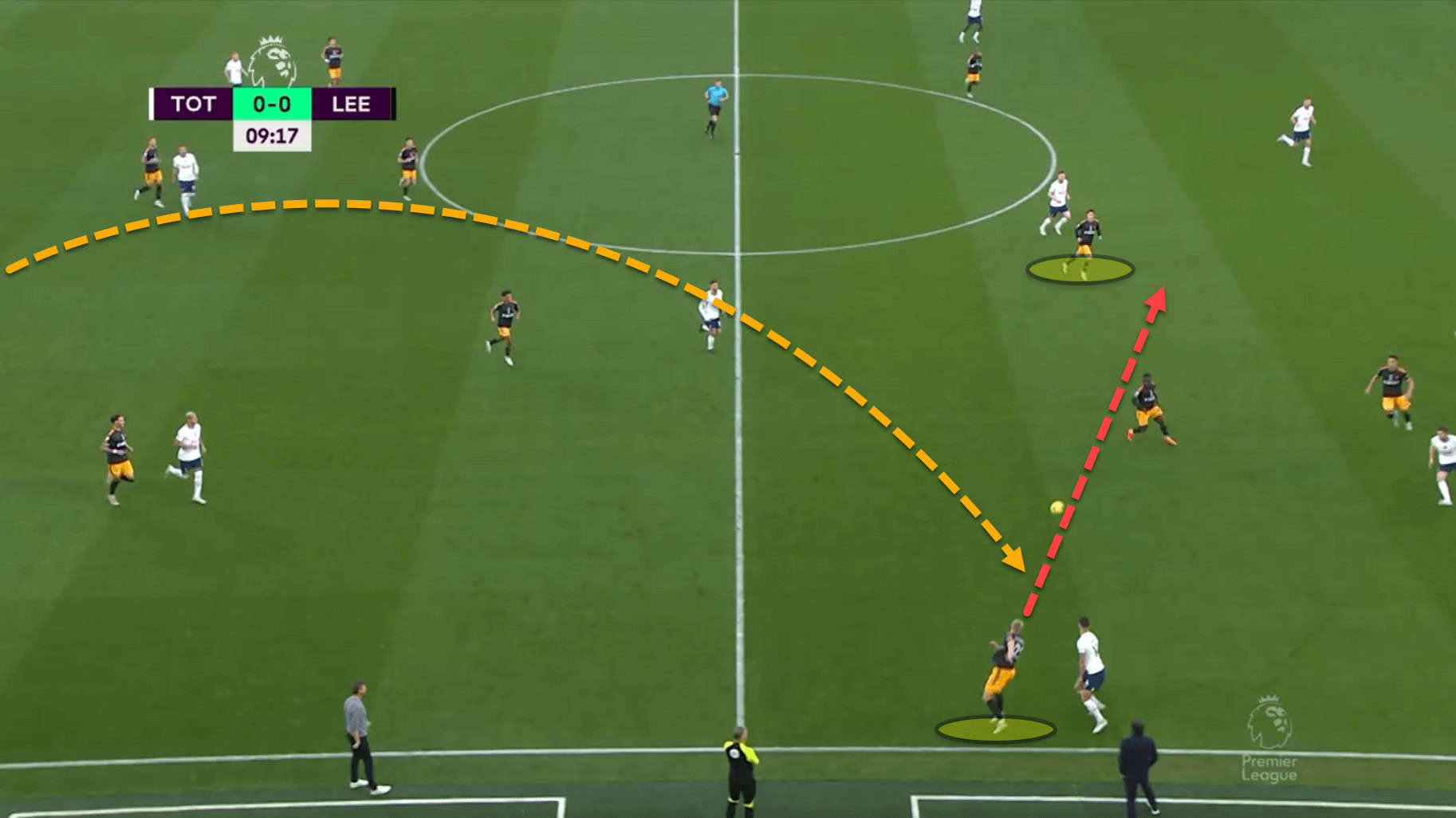

For this goal against Tottenham Hotspur back in November, six seconds had passed from the moment the ball was won at the halfway line to when Rodrigo rolled it past Hugo Lloris to take a 3-2 lead.

While many associate Bielsa’s football with sumptuous and scintillating rotations and possession-based play, fast attacks and intense pressing were already arrows in Leeds’ quiver. In fact, during the promotion campaign in 2019/20, no team scored more fast attacks in the Sky Bet Championship than Bielsa’s men.

Furthermore, during Leeds’ 2020/21 Premier League season, no team scored more counterattack goals than Bielsa’s boys.

Leeds averaged 3.25 counterattacks per game that season with 37.2 percent ending in a shot – more than one in three led to an opportunity at goal. During Leeds’ first season back in the top-flight, this increased to 54 percent which is ridiculously high.

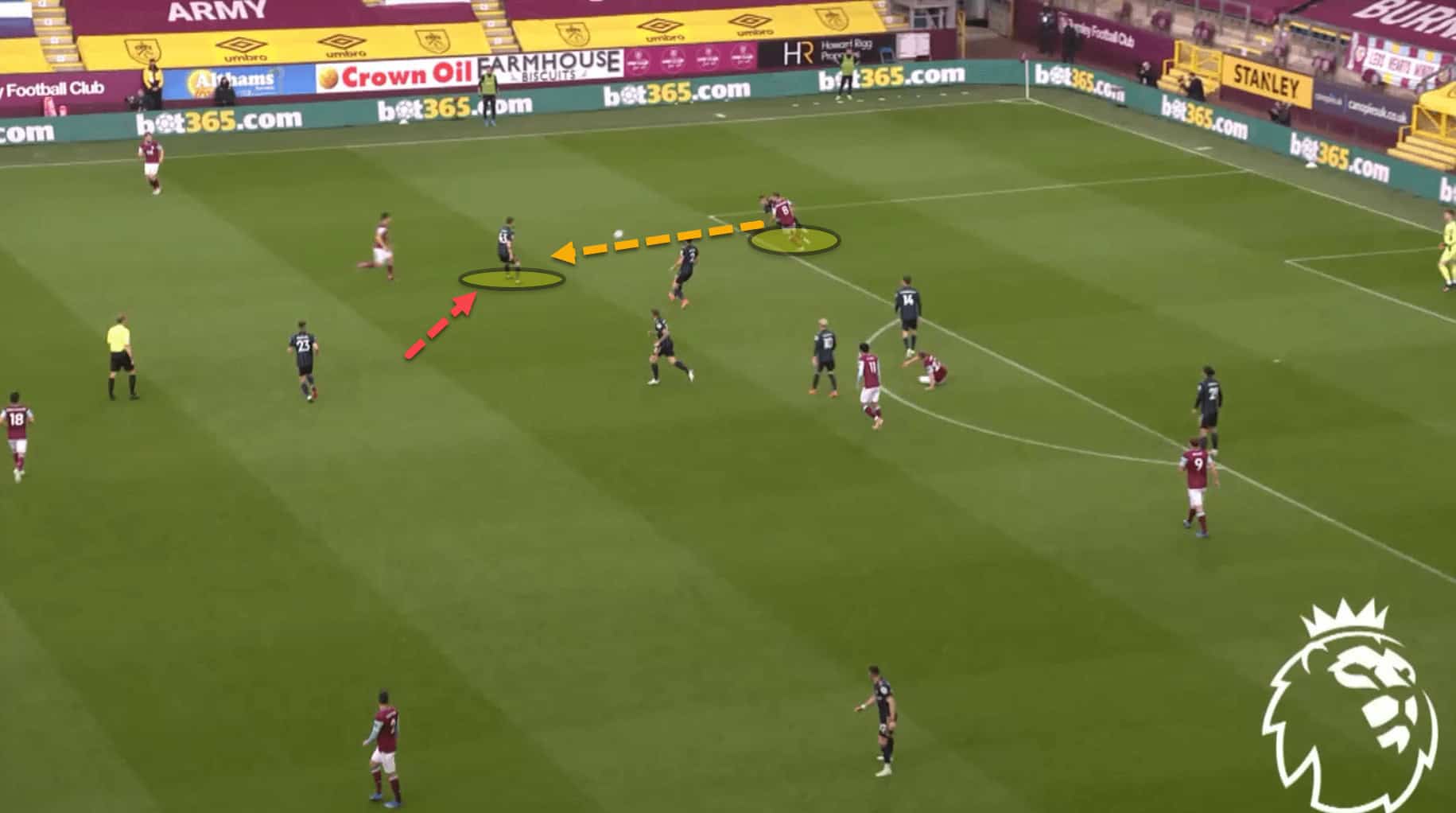

Here, having won the ball in the first third of the pitch, Mateusz Klich had placed it past Burnley’s Nick Pope within merely 14 seconds, while six players had advanced forward in and around the penalty area. The speed of the attack was truly frightening.

Interestingly, under Marsch and Skubala this season, the Lilywhites averaged just 1.83 counterattacks per game. Leeds have been counterattacking less than in any campaign since before the Bielsa era despite holding only 50 percent of the ball on average per game.

The speed of the attacks are still there, though. According to Opta, Leeds have had the quickest attacks in the Premier League this season with the fifth-fewest passes per sequence. The problem is, they have been far less effective than in recent seasons.

Transitions can still be an efficient method for Leeds to hurt teams, but the onus will be on Javi Gracia to reignite the spark in his new side, making them a force on the break again.

Thankfully, Gracia’s Watford were actually excellent on the break and boasted just under three counterattacks per game with 30.4 percent leading to a goal. With players such as Pereyra, Deulofeu, Gray, Deeney, and Étienne Capoue and Doucouré making runs from deep, quick transitions were a common method of hurting teams under the Spaniard.

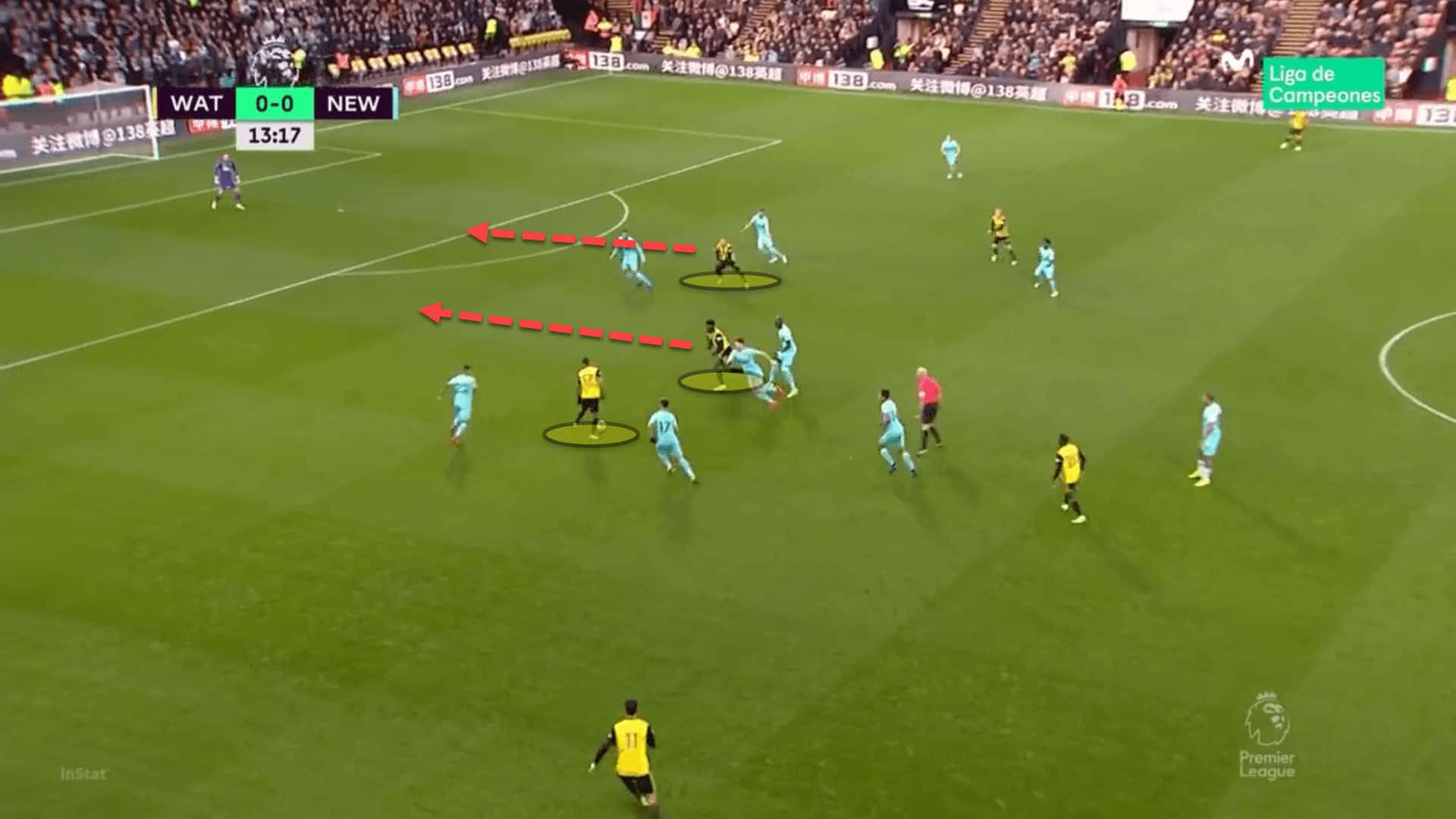

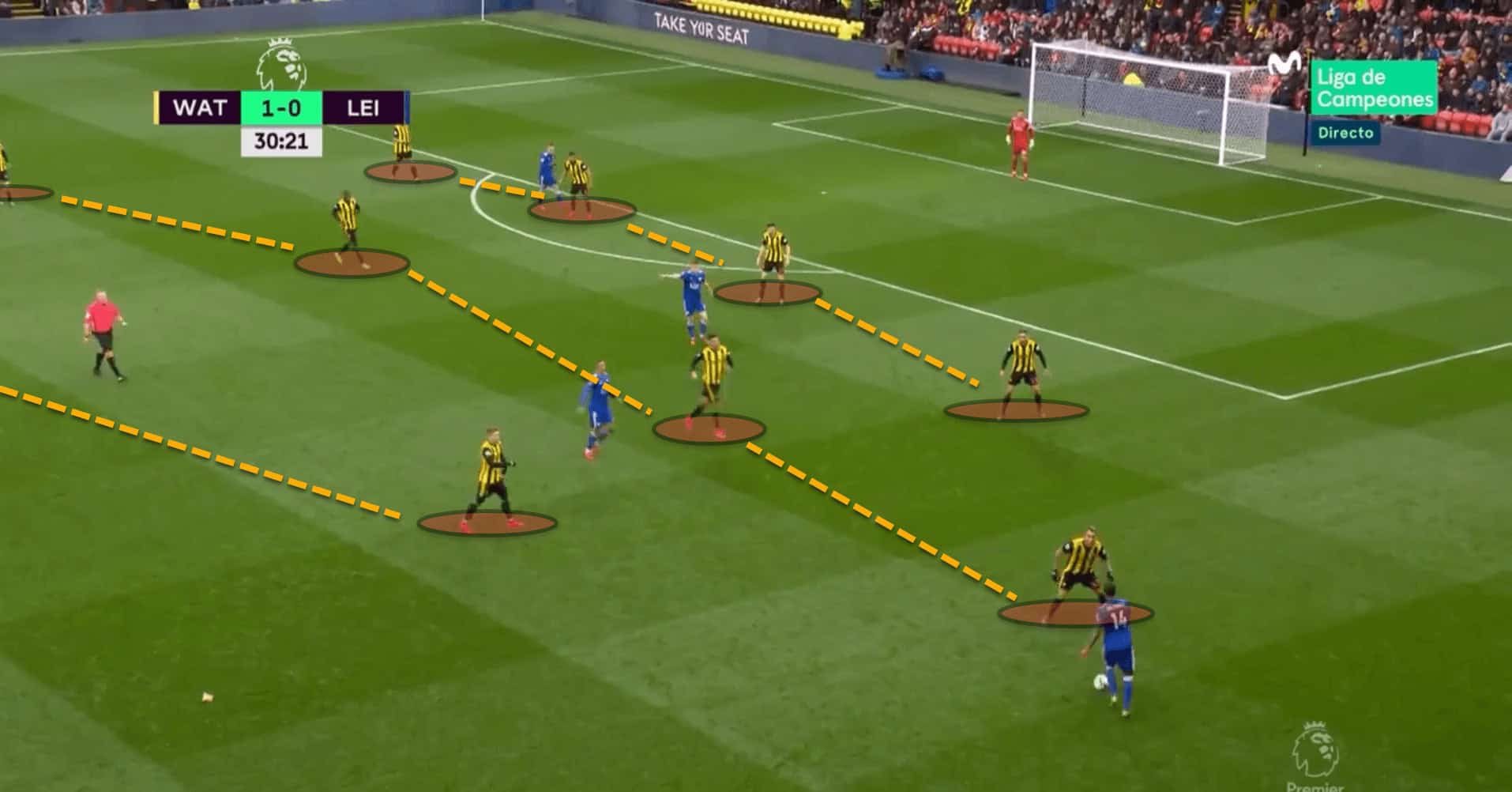

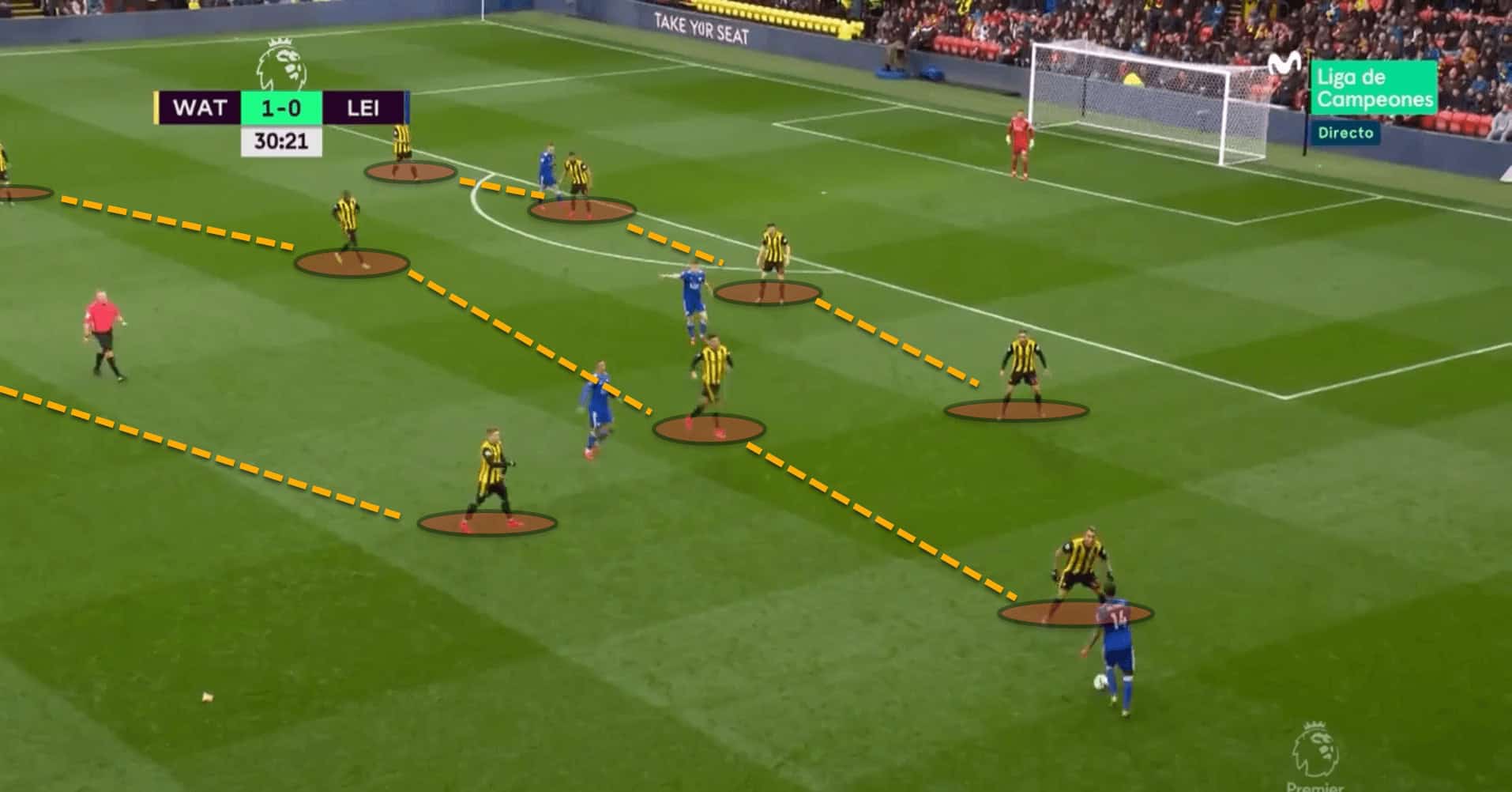

After the ball was won in the middle of the park, Watford piled men forward, using ball-carrying central midfielders and runners in all different directions to hit spaces behind Leicester City’s exposed backline.

There is a lot of quality in this Leeds team which has become better-placed for transitions than holding possession, moving away from Bielsa’s blueprint which many feared would be the case upon Marsch’s appointment.

Nevertheless, the signing of Gracia seems a lot closer in style to his predecessor this time around. In fact, Gracia’s Watford and Valencia averaged 3.66 and 3.84 passes per possession respectively which is fewer than Leeds this season at 3.93.

Counterattacks and transitions will likely stay as a very common method of hurting teams under the new coach. It will be Gracia’s job to make them more threatening in these situations.

More width

One of the most prevalent criticisms of Marsch’s football was the overarching lack of width. When Leeds had the ball on one side of the pitch, there was no player holding the width on the far side such as a fullback or a winger, as is common in a lot of teams nowadays.

Instead, the ball-far fullback or wingers would tuck inside into the halfspaces, meaning the team were highly compact in possession but the players were also in close proximity to counterpress and regain the ball if play was turned over.

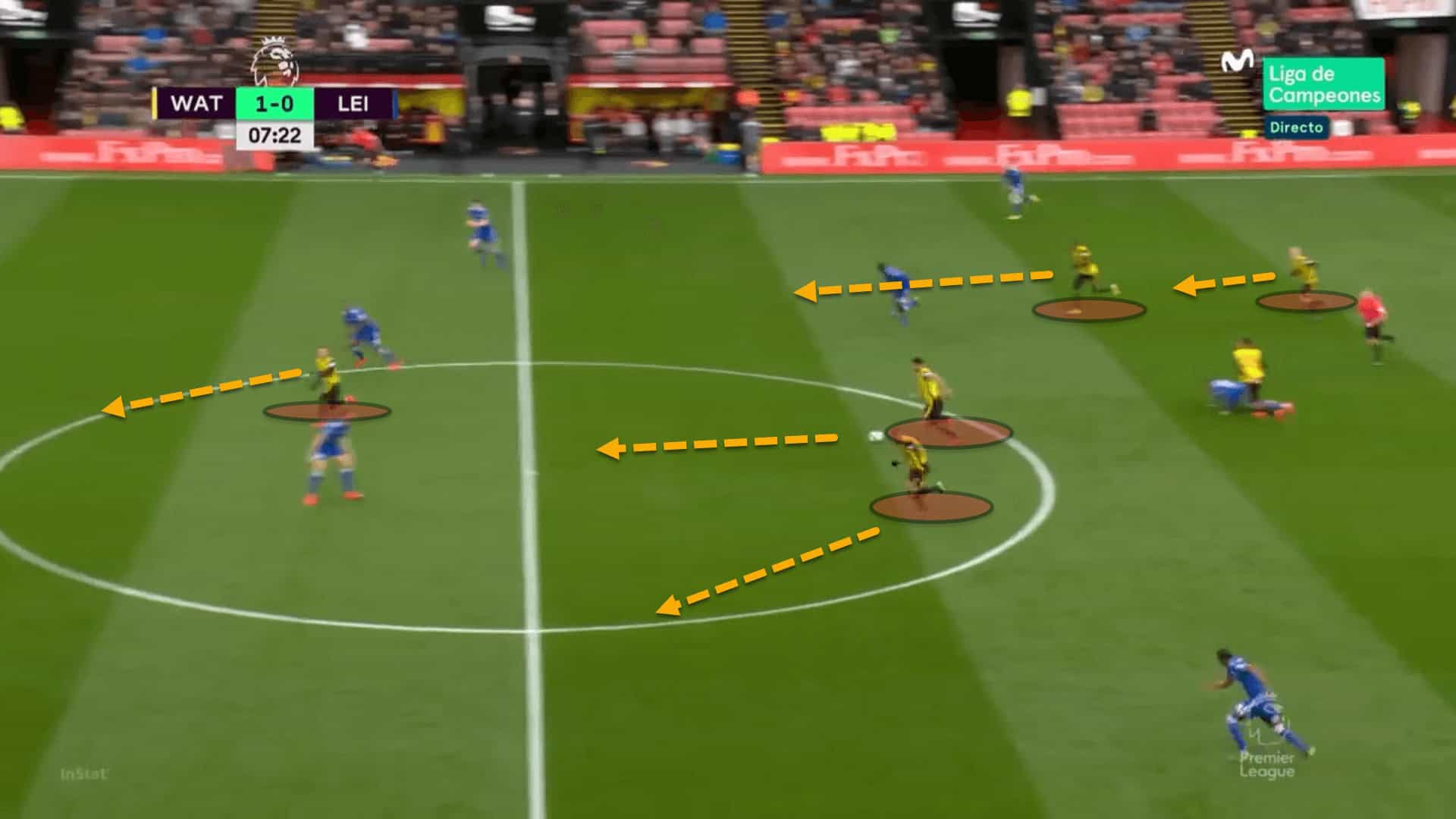

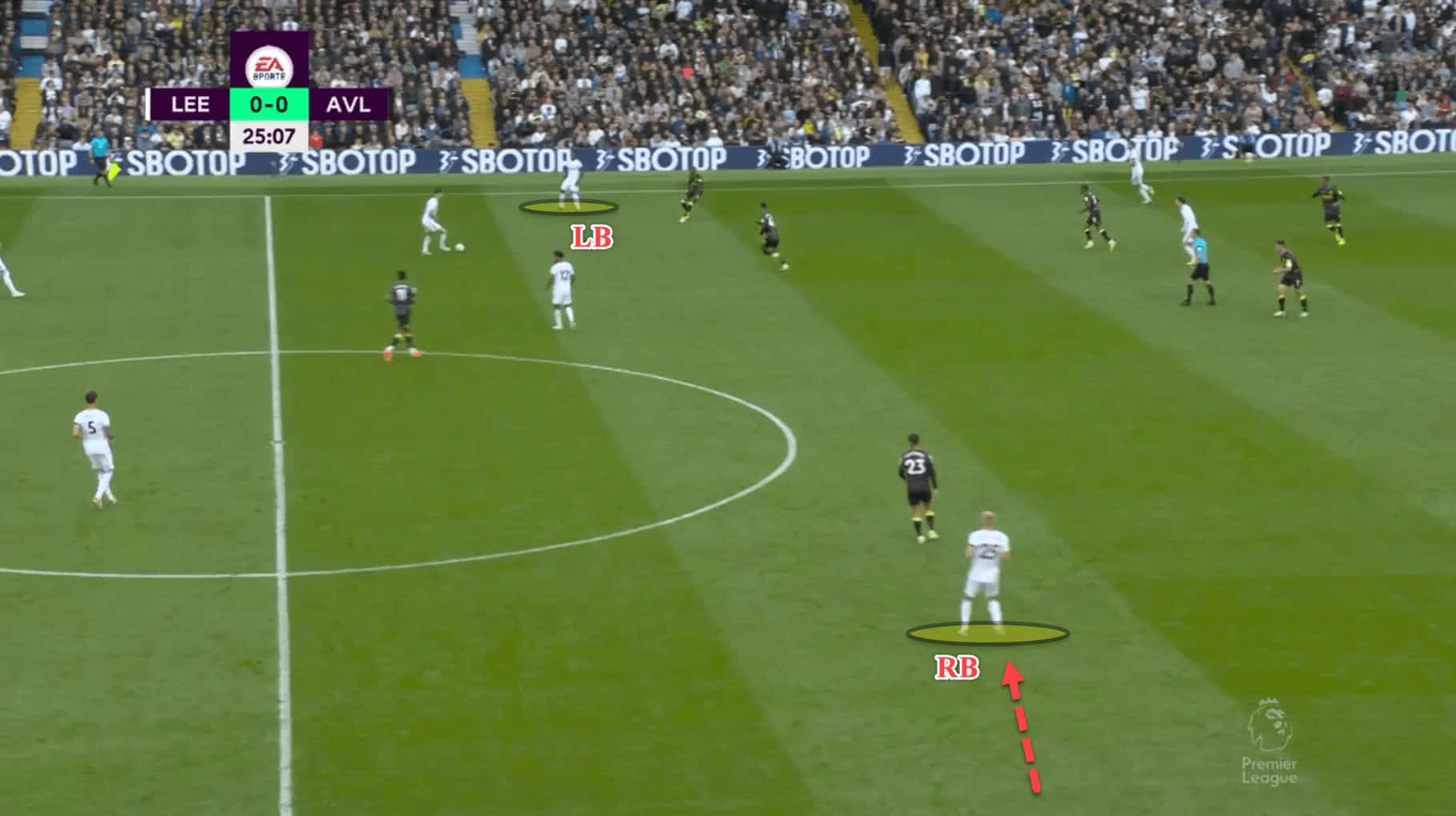

In this example, the right-back Rasmus Kristensen tucked into the halfspace when the ball was on the left. The right winger was also positioned inside and so there was no player holding the width on the left flank.

Most teams adhere to positional play methodology where width is of vital importance. There are always at least two players staying wide to stretch the opposition horizontally.

Marsch is quite the opposite. His idea is to have the ball as a reference point in possession as opposed to space. So, if the ball was on the left, Leeds would overload the left to get as many passing options around the ball as possible.

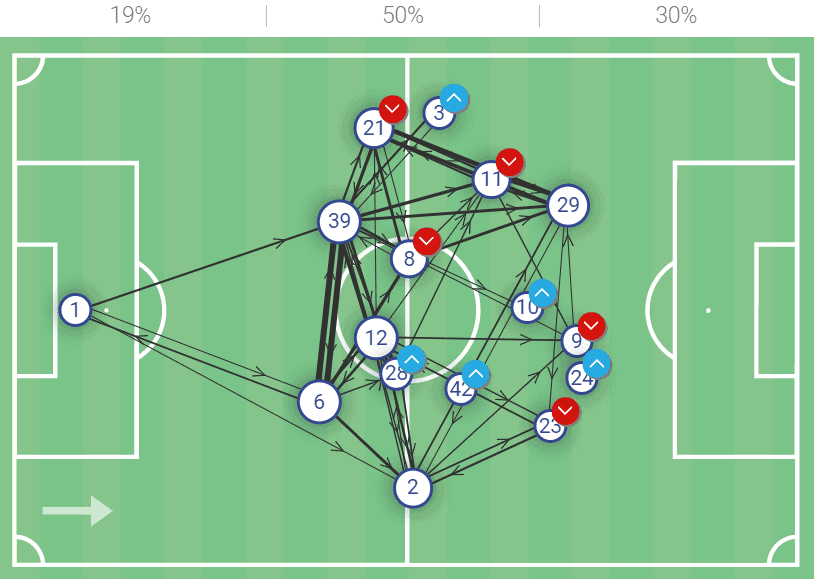

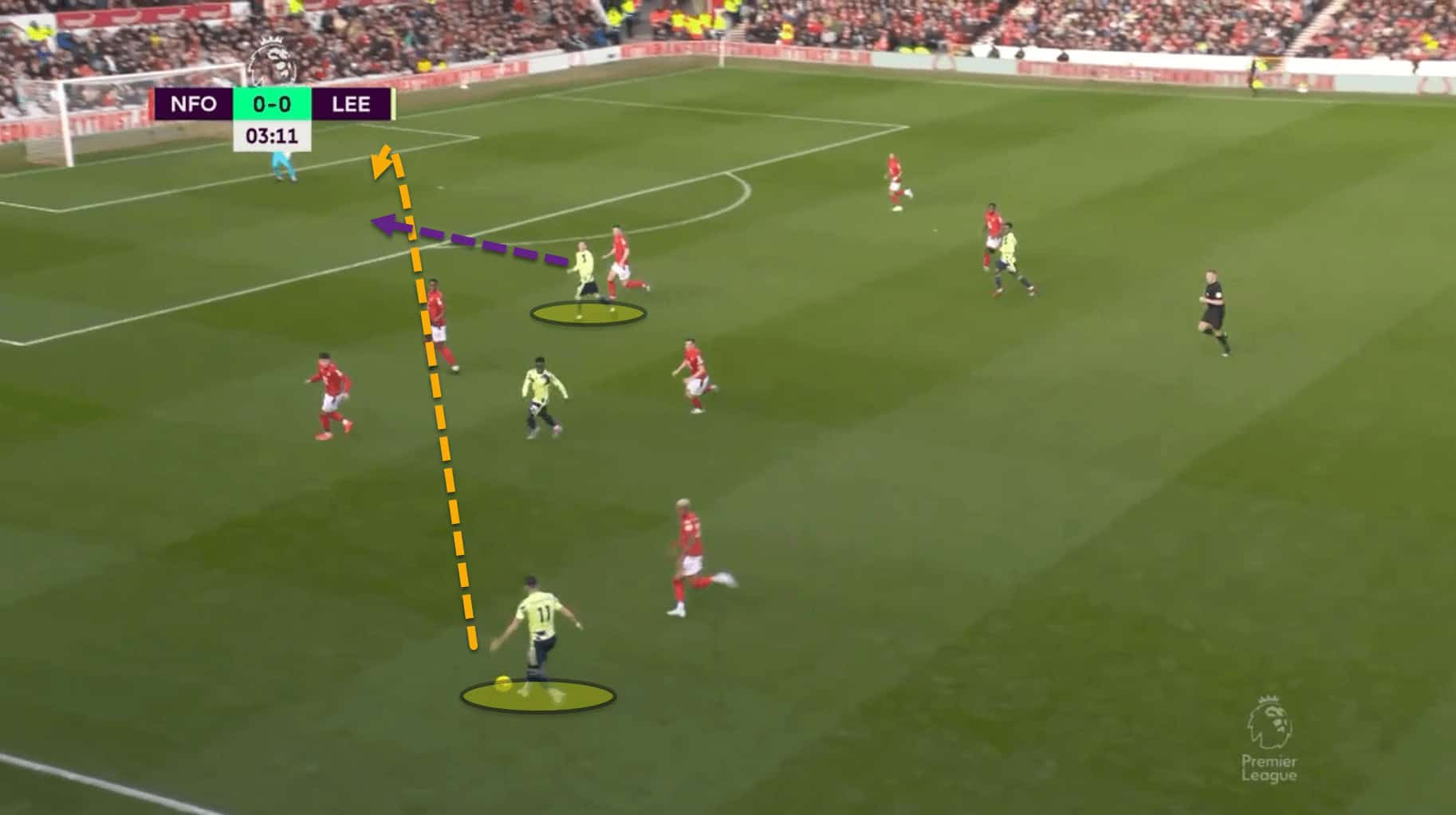

We can see how compact Leeds’ positional structure was under Marsch using this example from his final game in charge, away at Nottingham Forest. There is no real width and even the wingers, Jack Harrison (no. 11) and Luis Sinisterra (no. 23), were positioned extremely narrow.

The focus was not to stretch horizontally, but vertically. This meant that Leeds wanted to get the ball forward as quickly as possible using combination play with players in close proximity to break through the opponent’s defence or by simply going direct into space.

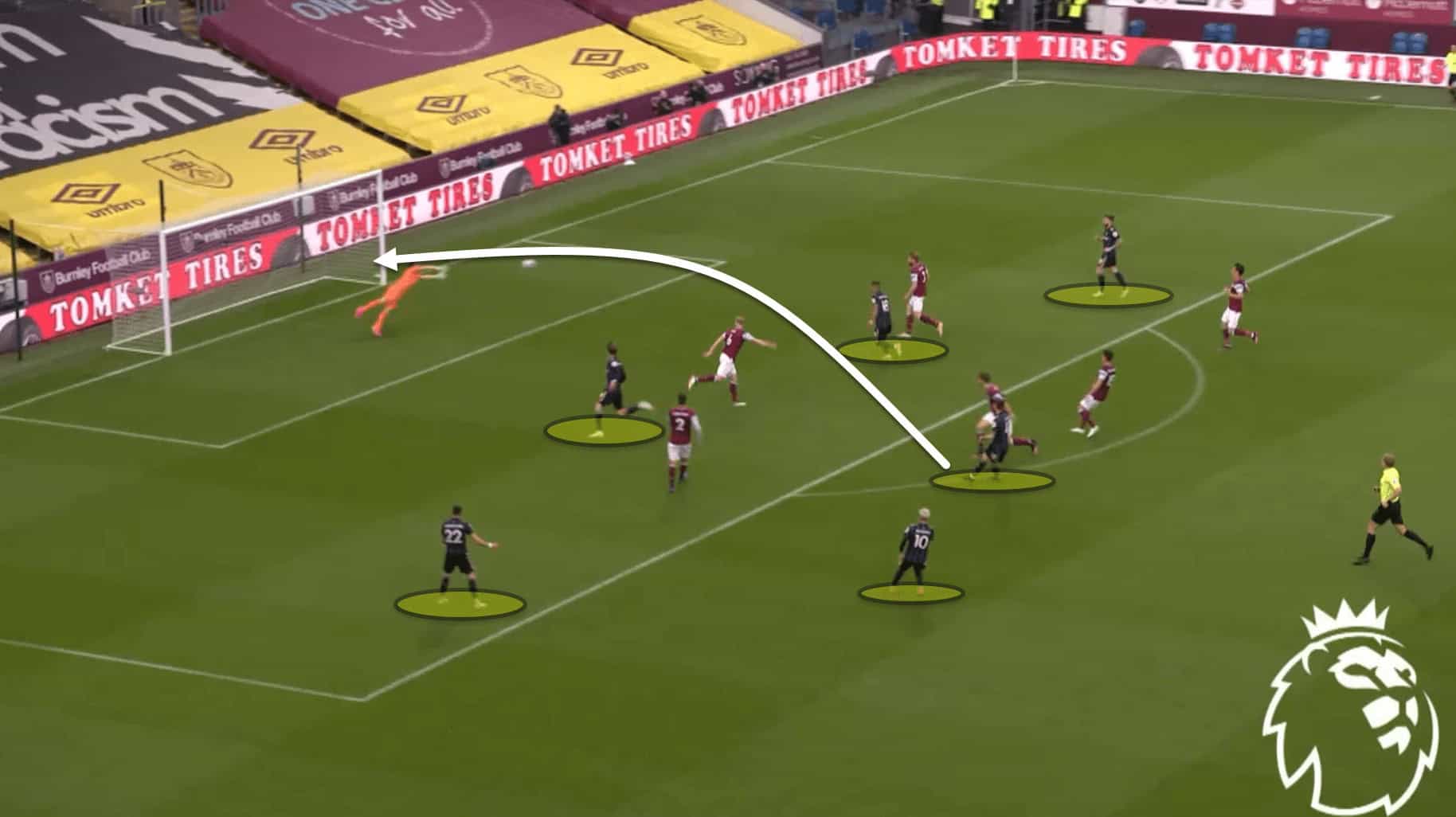

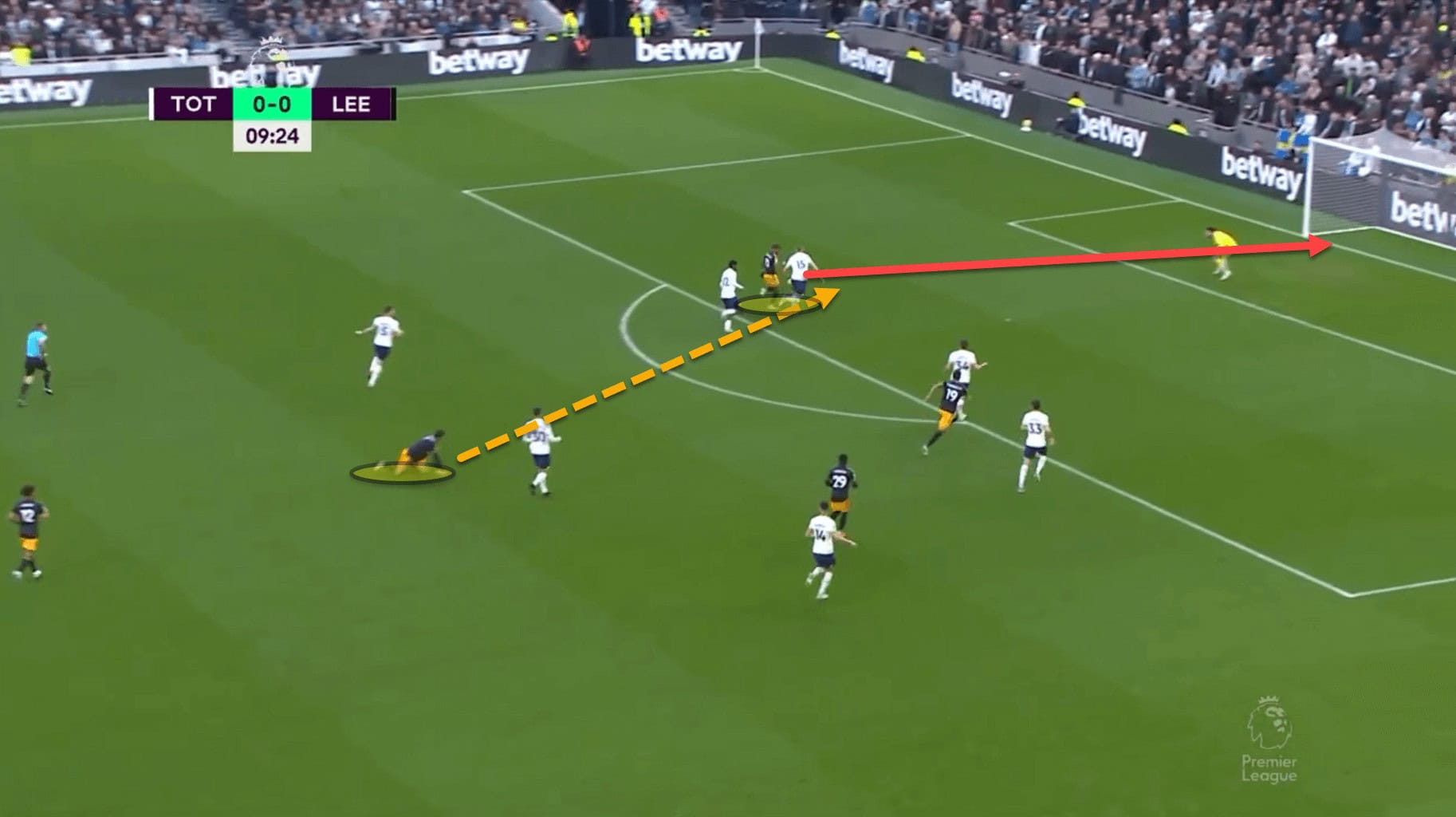

This was a typical goal under Marsch. The goalkeeper pumped it long to Kristensen at right-back. Meanwhile, the furthest players drifted inside to create a compact structure. The fullback won his header which landed in the path of Brenden Aaronson who poked it through to Crysencio Summerville. The Dutch winger slid the ball under Lloris to open the scoring.

Leeds moved from the goalkeeper to Spurs’ box in three passes and capped it off with a goal. However, these attacks became trickier and trickier to form the longer Marsch was in charge. But why?

Essentially, Marsch’s offensive tactics thrived when Leeds’ attackers had plenty of space to run into. Take away this space and the threat is severely limited. Teams did so by sitting deeper against the West Yorkshire club, meaning there was no real room to exploit behind the opposition’s backline.

Harrison wanted to play the ball in behind but there was little space behind Forest’s defensive line for the pass to find its intended man without reaching the goalkeeper first who was ready to rush out and collect it.

There will be a noticeable difference under Gracia when observing how Leeds play in possession. Where Marsch is an advocate of dynamic and situational width, Gracia very much comes from the Spanish school of coaching where width is indispensable.

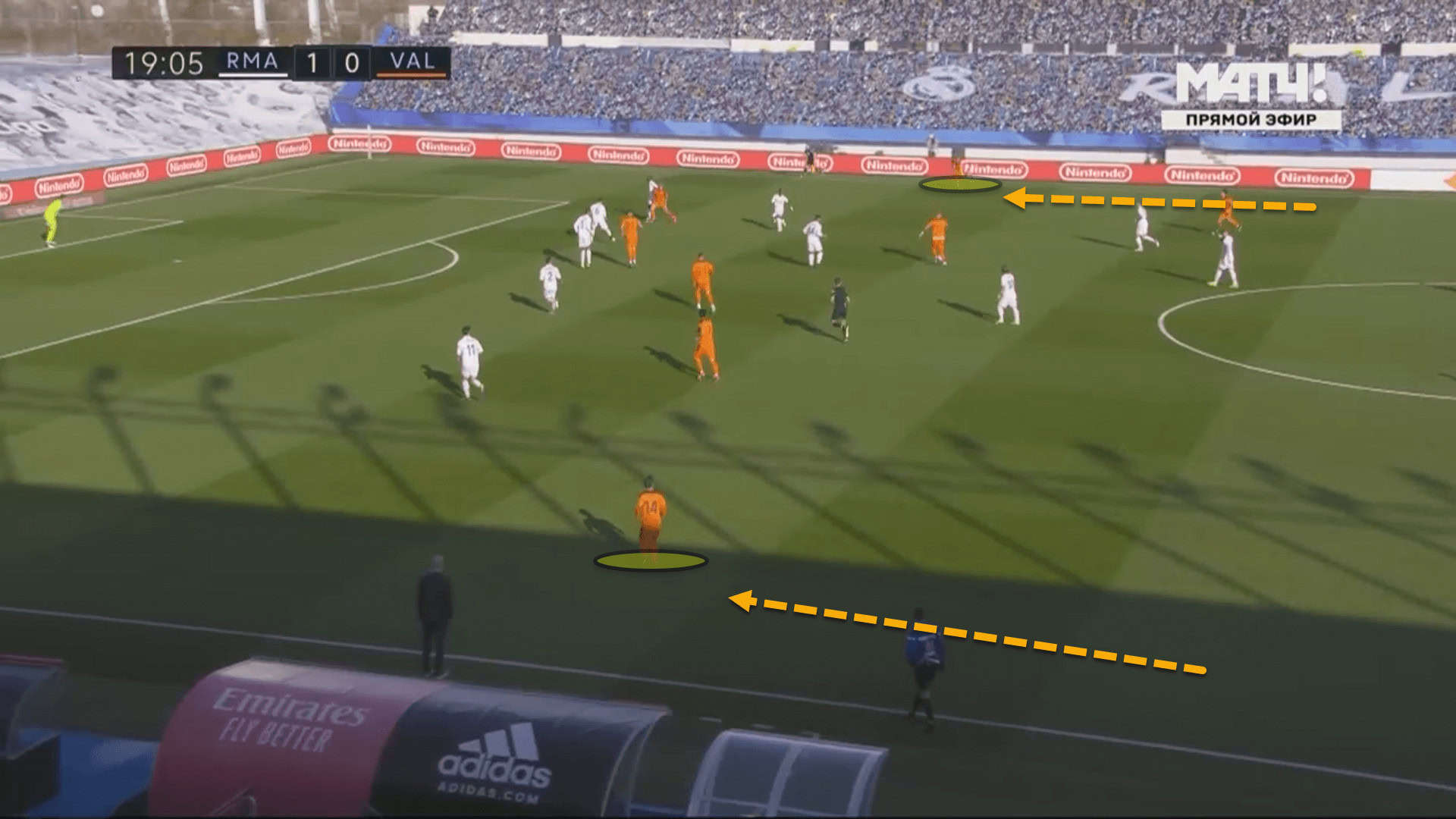

Leeds will likely set up in a 4-2-2-2 or 4-2-3-1 base but will get the fullbacks really high up the pitch to provide the width at Elland Road, just as Valencia did under Gracia here:

Fullbacks are really important to how Gracia’s teams attack, but the manager has a way to get them free in space while having time to pick out a cross aimed towards the middle.

At Watford and Valencia, Gracia would instruct his midfield and forward line to squeeze together and overload the centre of the pitch, putting multiple bodies between the lines to try and receive in dangerous positions.

What this does is force the opponent to narrow their defensive block. As there are so many bodies in the central spaces, the opponent’s players must squeeze together to ensure that they are not too stretched which would open the lanes to these attacking players.

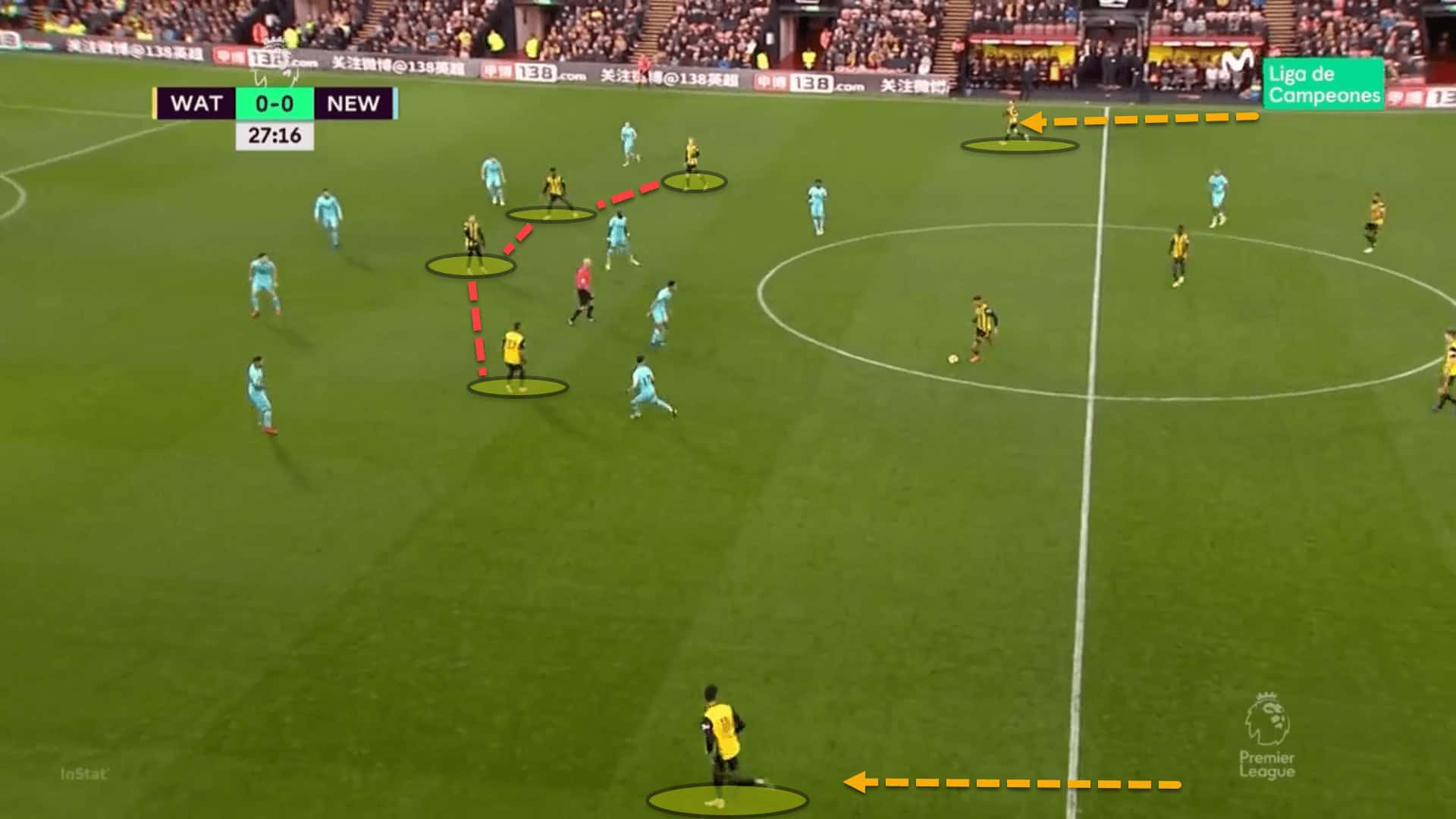

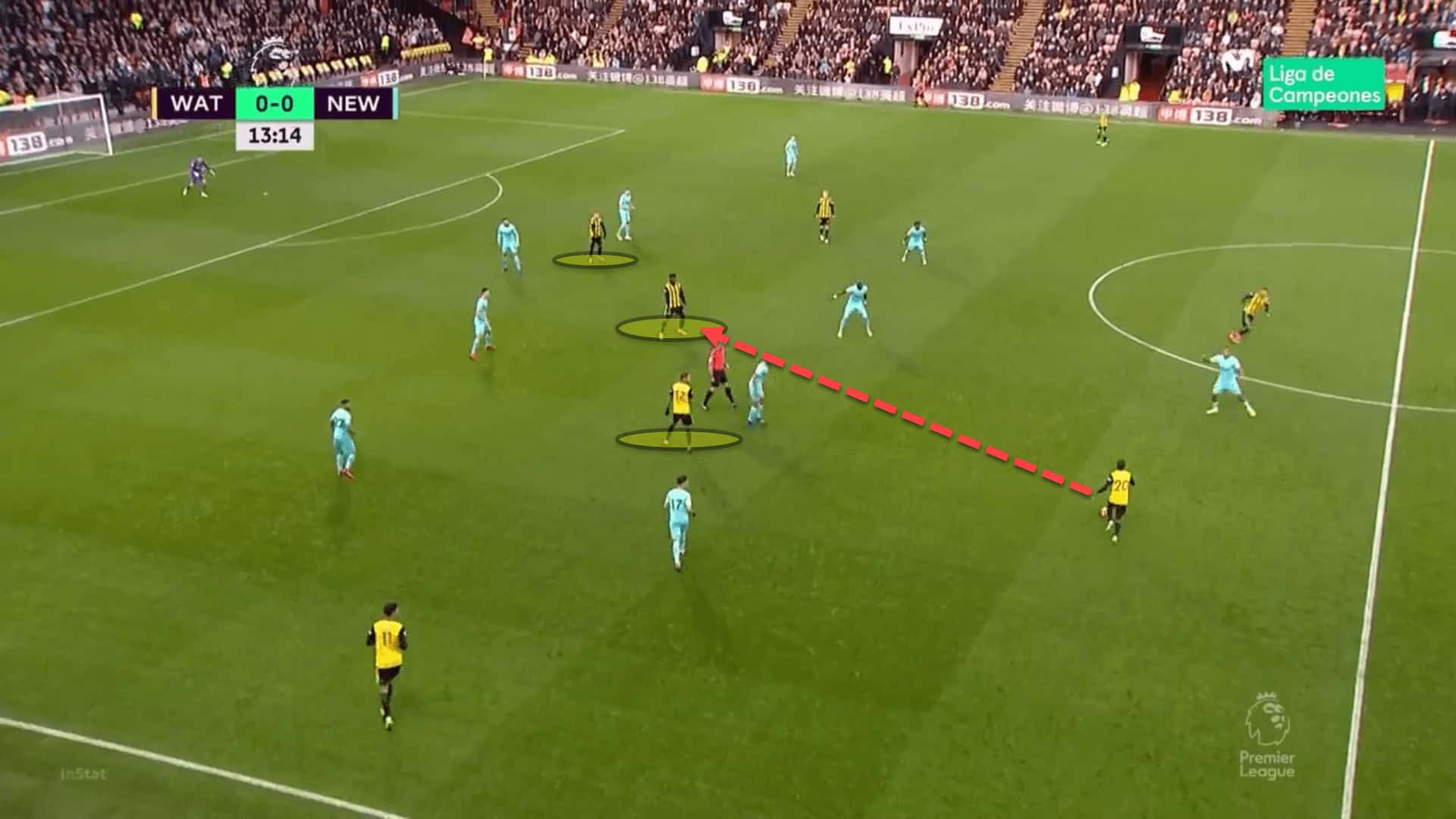

Here, Newcastle United are defending in a 4-4-2 shape. The sheer number of Watford bodies between the Magpies’ midfield and backline has caused them to become extremely compact, leaving space out wide for the fullbacks to receive from quick switches of play.

At Leeds, these switches will be a common method of progressing into the final third. Using players such as Harrison, Wilfried Gnonto, Sinisterra, Summerville and Aaronson among others between the lines to create spaces for the fullbacks and having actual width on both flanks could be a sight of beauty for many supporters at Elland Road.

But Gracia doesn’t instruct his attacking players to play so close to one another merely as a means to create space for the fullbacks. This is partially the reason, but it also allows for combination play in this area if the ball reaches these players.

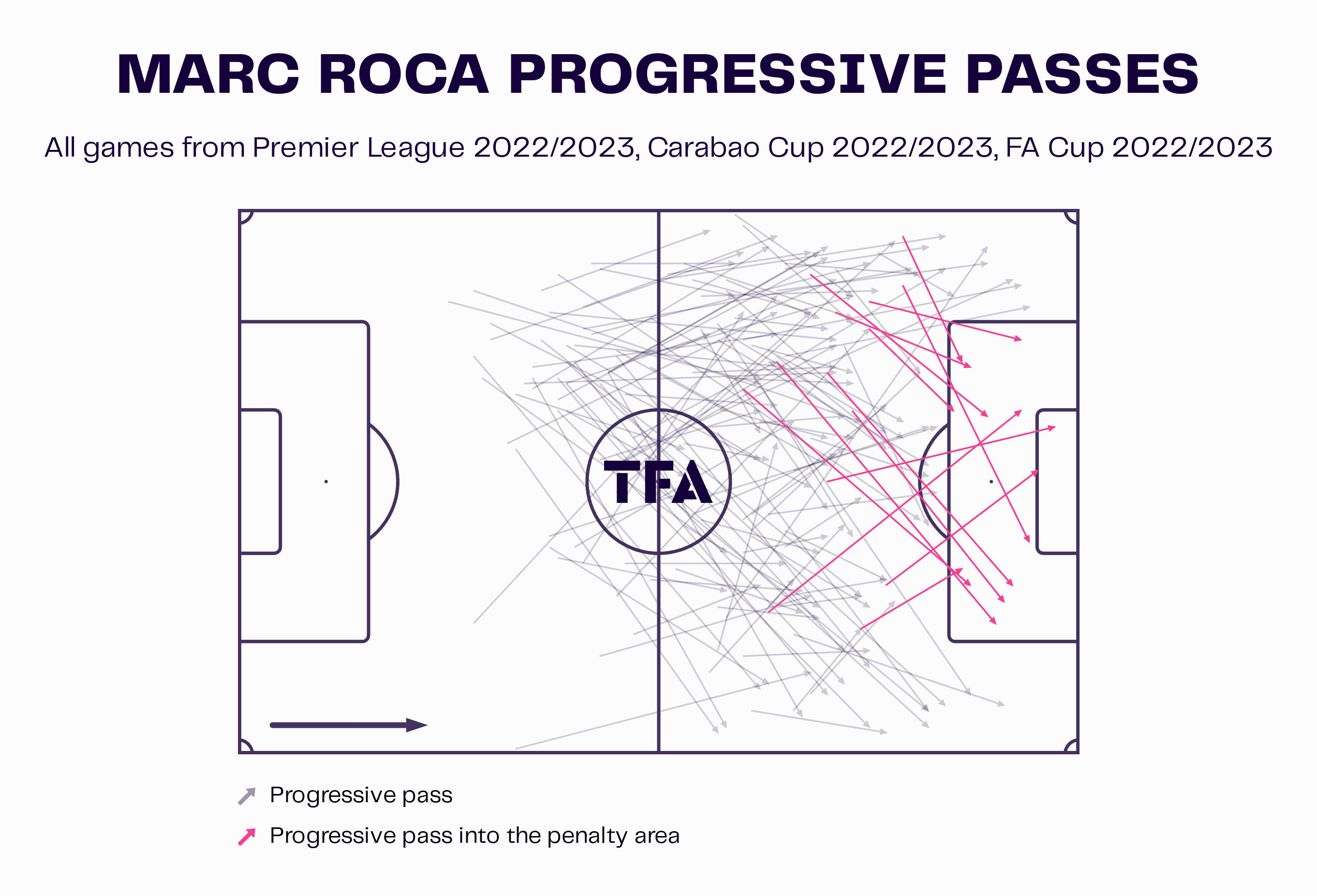

Marc Roca could be an important player in this regard. The summer signing has the capability to provide line-breaking passes from deep to players between the lines but can also reach the fullbacks with pinpoint switches of play.

Once the ball has reached the area between the lines, third-man runs and combinations are Gracia’s best friend and are a common method for his sides to break down a defensive block in the final third.

This is not overly dissimilar to Marsch’s tactics in possession. The American was keen for his Leeds team to create these combinations between the lines. However, the difference is that, under Gracia, they won’t be the only method of ball progression.

Same but different is perhaps the best phrase to use to conclude this section. A lot of similar principles will be prevalent but executed very differently and with greater variety.

Defending lower down the pitch

During his time at Vicarage Road, Gracia’s Watford were let down the most by their defensive contributions. Boasting one of the best attacking records in the Premier League in the 2018/19 campaign, the Hornets also had one of the worst defensively.

Watford scored 52 and conceded 59, holding a goals per 90 rate of 1.28 and 1.45 goals conceded per 90.

Gracia’s methods are not as intense as Leeds under Marsch. While the shape may be similar, the approach will be different.

This season, Leeds have pressed really high up the pitch, causing their average defensive line height to be close to the halfway line.

For better or for worse, Leeds press high and try to force turnovers as close to the opposition’s goal as possible, leaving a lot of space for the attacking side to exploit in behind with runners.

The Lilywhites were constantly being caught out on the break down the sides of the pitch as a result of having their fullbacks so high to press or counterpress.

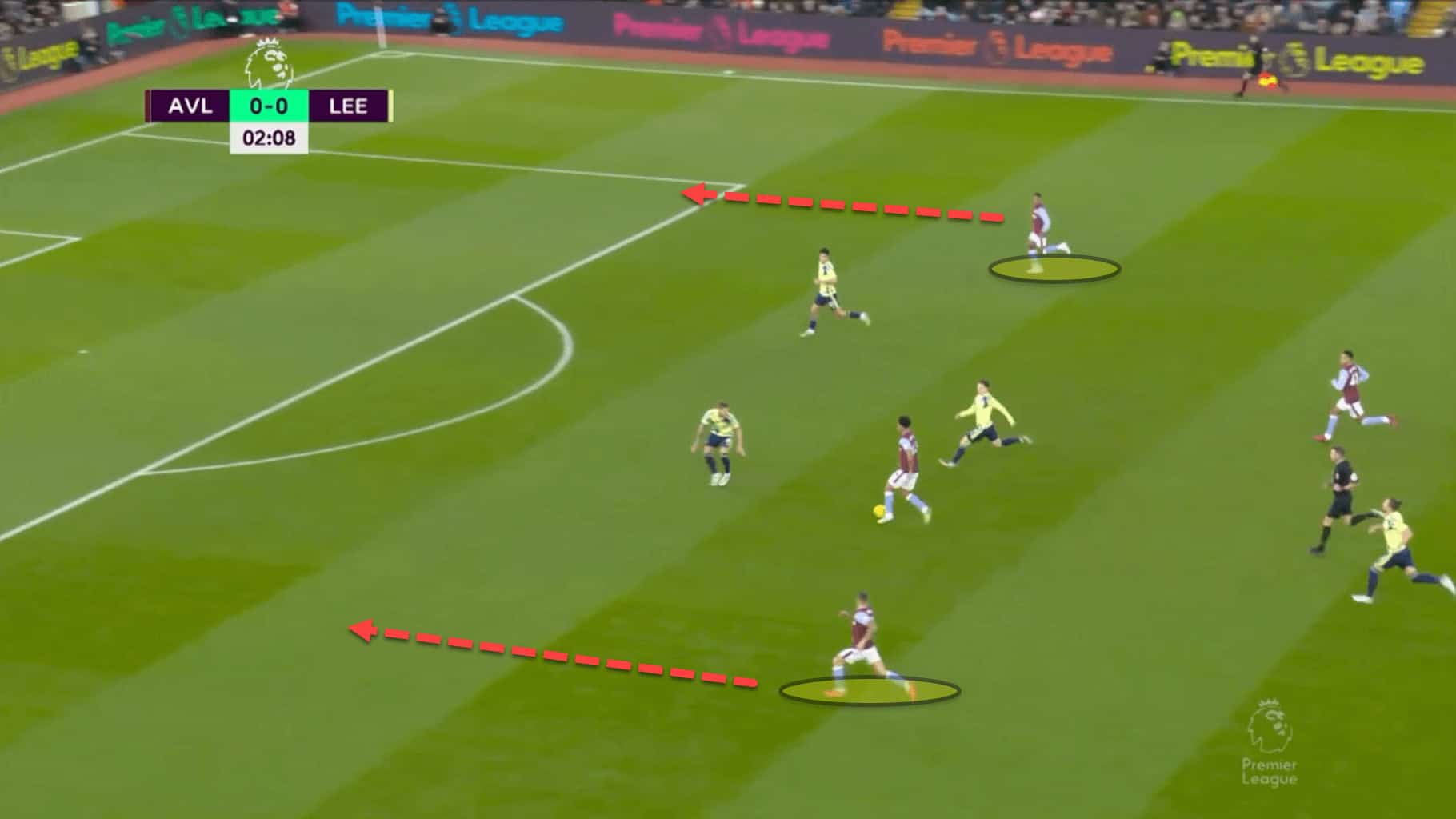

Aston Villa scored from this scenario over on the right side, but Unai Emery’s men could have easily attacked the left too.

Perhaps a switch to a slightly more pragmatic defensive block will be a welcome change by the Elland Road faithful. We can assure you that Leeds won’t be as willing to press as high up the pitch as they were during Marsch’s queasy tenure.

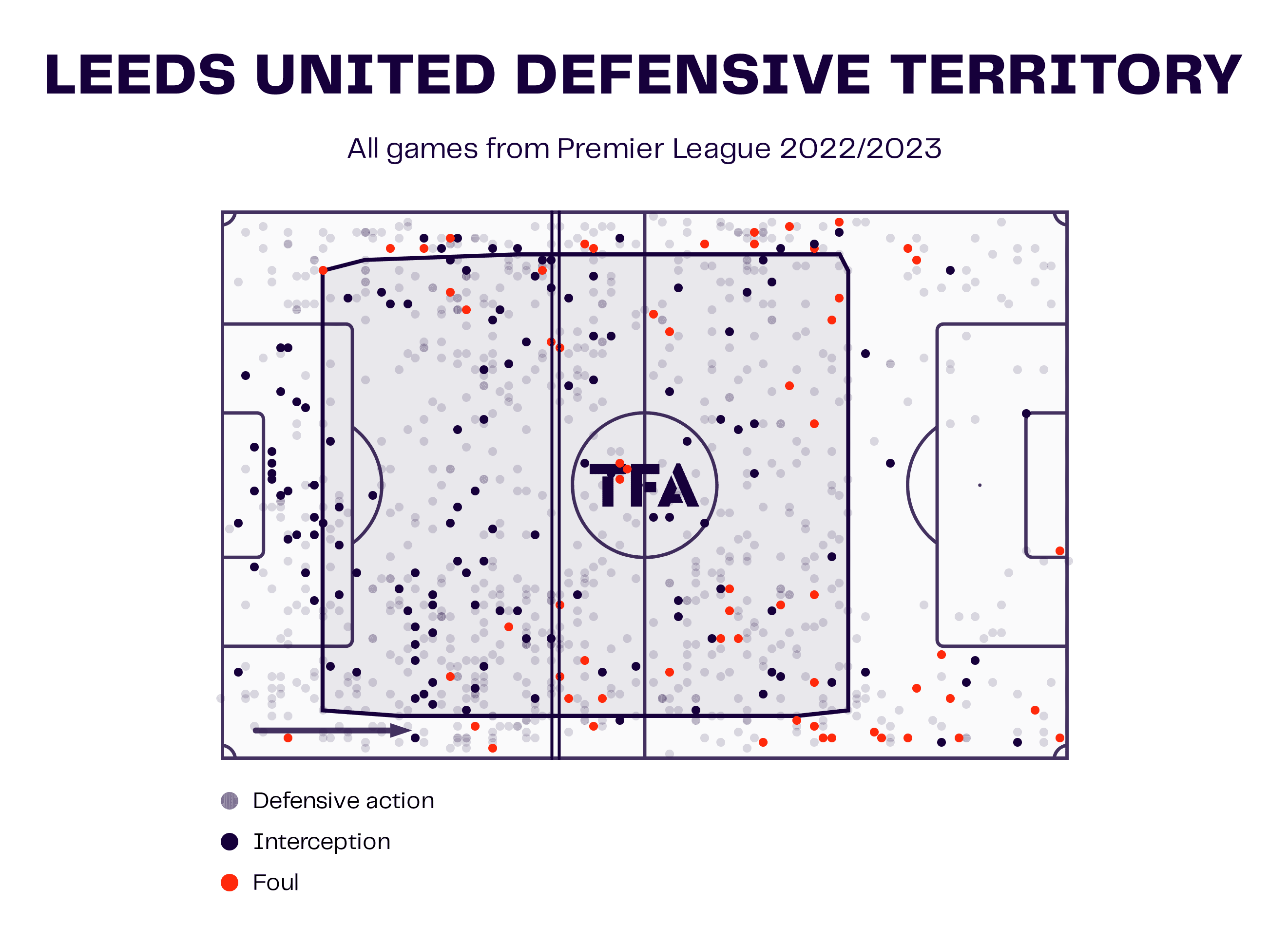

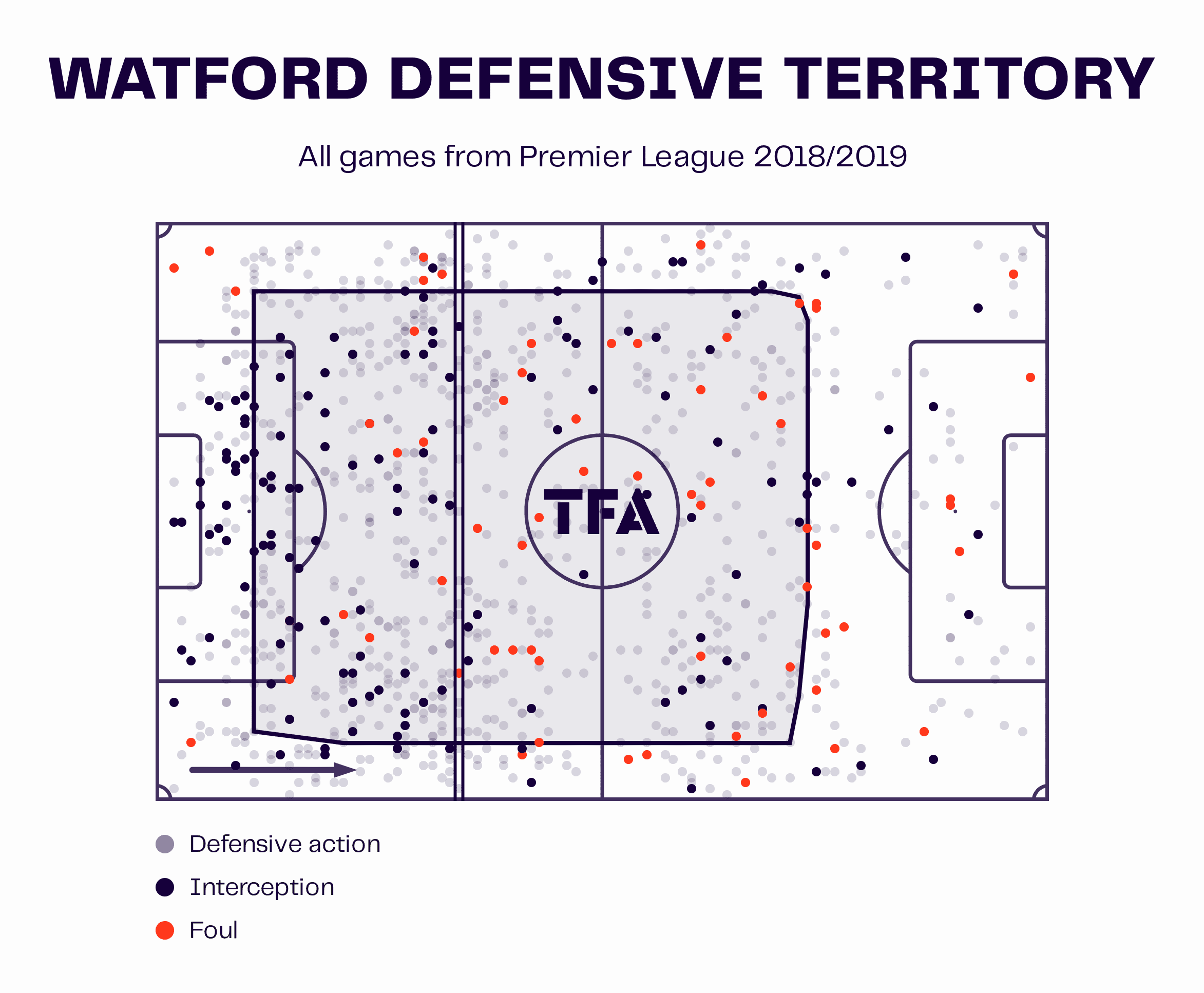

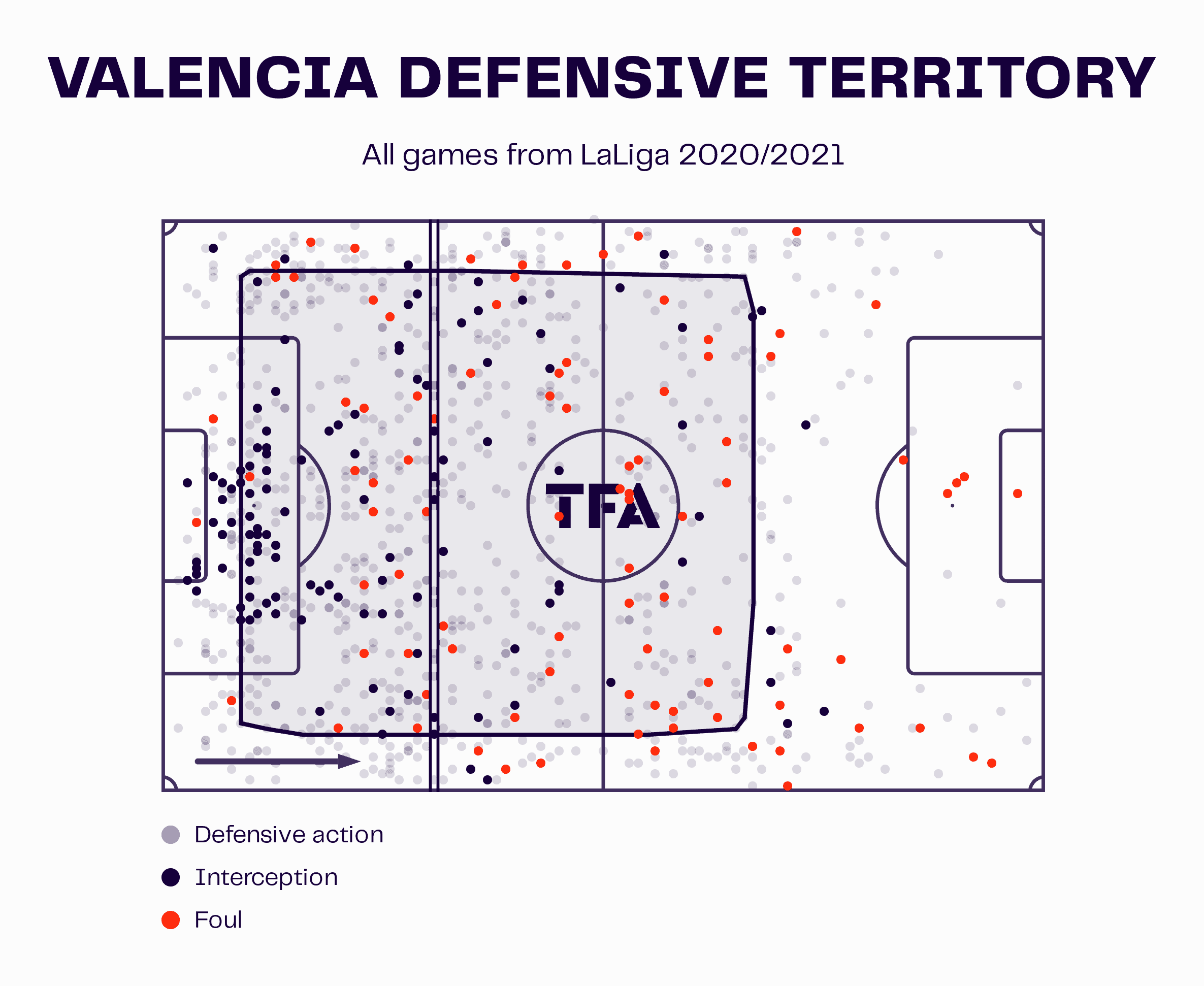

These two data vizzes highlight the average defensive line height of Watford and Valencia during Gracia’s tenure. As is evident, the lines are almost identical in height and are far lower than Leeds this season.

When defending deeper down the pitch, Gracia instructs his players to sit in a compact 4-4-2, trying to prevent the opposition from carving them open centrally. Gracia believes that the middle of the park must be closed off.

There is no real necessity to win the ball back quickly to create opportunities. Gracia is happy to allow the opposition to have the ball and for his players to contain them in less dangerous areas of the pitch such as the flanks.

If the opposition reaches the areas between the lines, then Leeds will aggressively close down the ball receiver, or if a poor touch is taken and the ball is there to be won, but the approach will be far less intense than under his predecessor.

The shape won’t be dissimilar to Marsch. Leeds will almost definitely defend in a 4-4-2 mid-to-low block, but the execution will be wholly different, and Leeds will be far more cautious out of possession.

Conclusion

Gracia’s appointment is almost a mix of Bielsa and Marsch. Whether that’s a good thing is yet to be seen.

However, the Spaniard should be an exciting arrival at Elland Road, a coach with a plethora of experience and with a history of relative success in English football, albeit brief.

There are areas where Leeds are struggling, and Gracia may be able to rectify these problems, creating a more balanced and unpredictable side capable of dyanamic variety as opposed to robotic, methodological, yet naïve repetition.

The appointment may not get bums of seats, but it doesn’t have to. Once those bums are on Premier League seats come next season, Gracia has done his job correctly.

Comments