Jorge Sampaoli is almost two months into his reign as manager of Olympique de Marseille and thus far, the 61-year-old Argentinian has been quite successful in a job that’s been described as carrying “suffocating pressure”. Sampaoli led Marseille to 16 points in his first seven games in charge at the Orange Vélodrome, which is the best start to life at the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur-based club since his compatriot and mentor Marcelo Bielsa, who’s currently in charge of EPL side Leeds United after winning the EFL Championship last season, was Marseille boss.

With the current top-four, Olympique Lyonnais, Monaco, PSG and Lille, far ahead of the chasing pack in Ligue 1 at present, the best that Sampaoli could realistically achieve on arrival at Les Olympiens is fifth place and thanks to his side’s positive start to life under his management, Sampaoli has got Marseille challenging for that fifth-place finish.

On arrival at Marseille, Sampaoli declared that his goal for this season was to transform the team from the André Villas-Boas version by putting “in place a playing philosophy” by returning “to the fundamentals, desire, rhythm” and while it’s still early days for the Argentinian in France, his Marseille side is already vastly different to that of his predecessor in several areas, which perhaps gives us an indication of the playing philosophy that Sampaoli intends to mould this team around.

This tactical analysis provides analysis of the tactics that Sampaoli has used in the early stages of his time in charge of Marseille. We’ll look at some key elements of the tactical philosophy he is bringing to Orange Vélodrome and how it has quickly brought some success to his new team.

Sampaoli’s Marseille in the build-up

Firstly, we’ll look at how Sampaoli’s new side have played in the build-up. One glaring change in Marseille’s tactics under their new manager is they’ve been playing with three centre-backs regularly, whereas before Sampaoli’s arrival, they typically played with two centre-back formations – usually either 4-3-3 or 4-2-3-1. Under Sampaoli, Marseille have primarily utilised either 3-4-1-2 or 3-4-2-1.

This is somewhat reminiscent of Marseille under Sampaoli’s friend and mentor Bielsa, as they also frequently played with three centre-backs. However, the similarities between Sampaoli and Bielsa don’t stop there, as like his compatriot Bielsa, Sampaoli also favours a heavily possession-based style of play, which has been evident in his time as Marseille manager thus far.

In their eight Ligue 1 games under Sampaoli, Marseille have kept an average of 58.4% possession per 90. Over the course of the 2020/21 season so far in its entirety, however, Les Olympiens have kept a lower average of 52.8% possession per 90.

This is a fairly significant difference that highlights a key element of the tactical philosophy that Sampaoli intends to bring to his new team. Marseille fans can expect to see their side attempt to dominate the ball more under their new, possession-focused manager. Had Marseille kept an average of 58.4% possession over the entire course of the Ligue 1 season, they’d be second only to PSG in this particular area.

Marseille would also be second only to PSG in the area of passes per 90 if their average under Sampaoli so far were their average for the entire season. Les Olympiens have played an average of 548.75 passes per 90 over their last eight league games, which is far more than the average of 445.62 passes per 90 that they’ve played over the entire season so far.

Sampaoli’s side hasn’t just shown that they intend to play a lot of passes, however, they’ve also shown that they intend to play a lot of progressive passes. Over the entirety of the 2020/21 Ligue 1 campaign, Marseille have played an average of 67.13 progressive passes per 90, which is fewer than as many as seven other Ligue 1 sides, however, in their eight league games under Sampaoli, Les Olympiens have played an average of 81 progressive passes per 90. If they’d managed to play that number of progressive passes per 90 over the course of the season, they’d have played the most progressive passes per 90 of any side in Ligue 1 by a notable margin.

So, Sampaoli’s football isn’t just heavy on possession and a large volume of passes, but he incorporates a lot of verticality into his football and he encourages his team to be constantly looking for line-breaking passes that get the ball upfield, into more dangerous positions from where his team can threaten the opposition goal. They are constantly looking to get forward with accurate passes, but at the same time, daring and threatening forward passes. This is something that distinguishes Sampaoli, which Marseille fans can expect to be a staple of their side’s football for the foreseeable future.

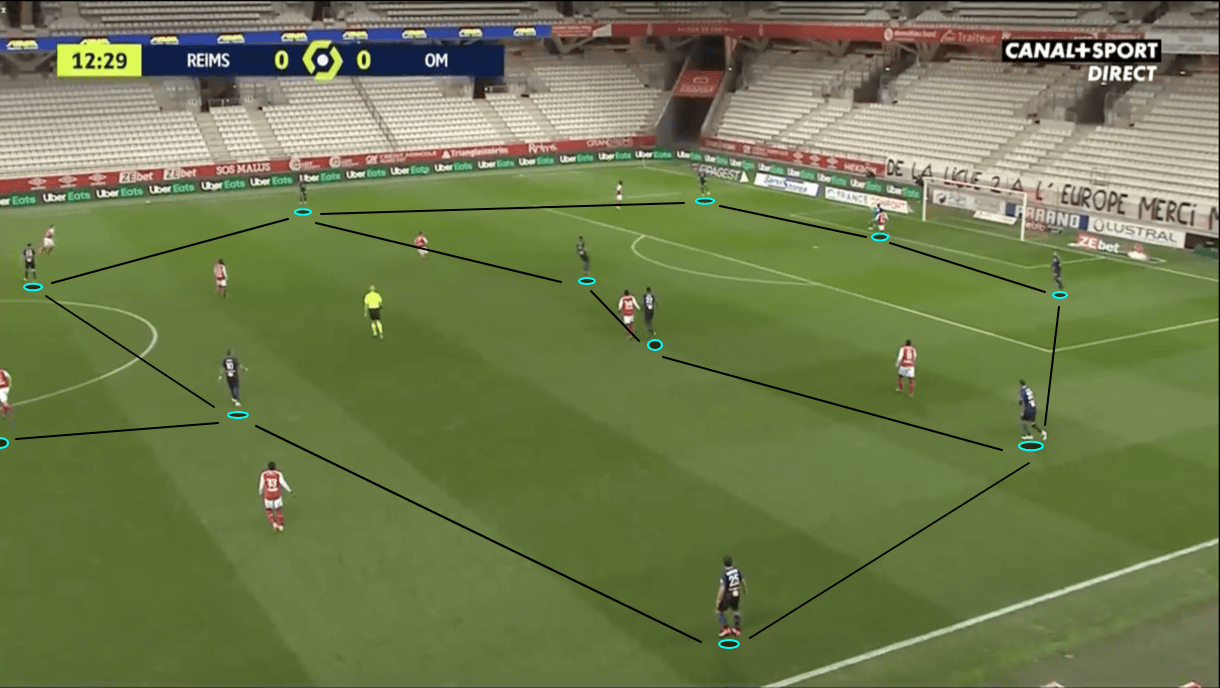

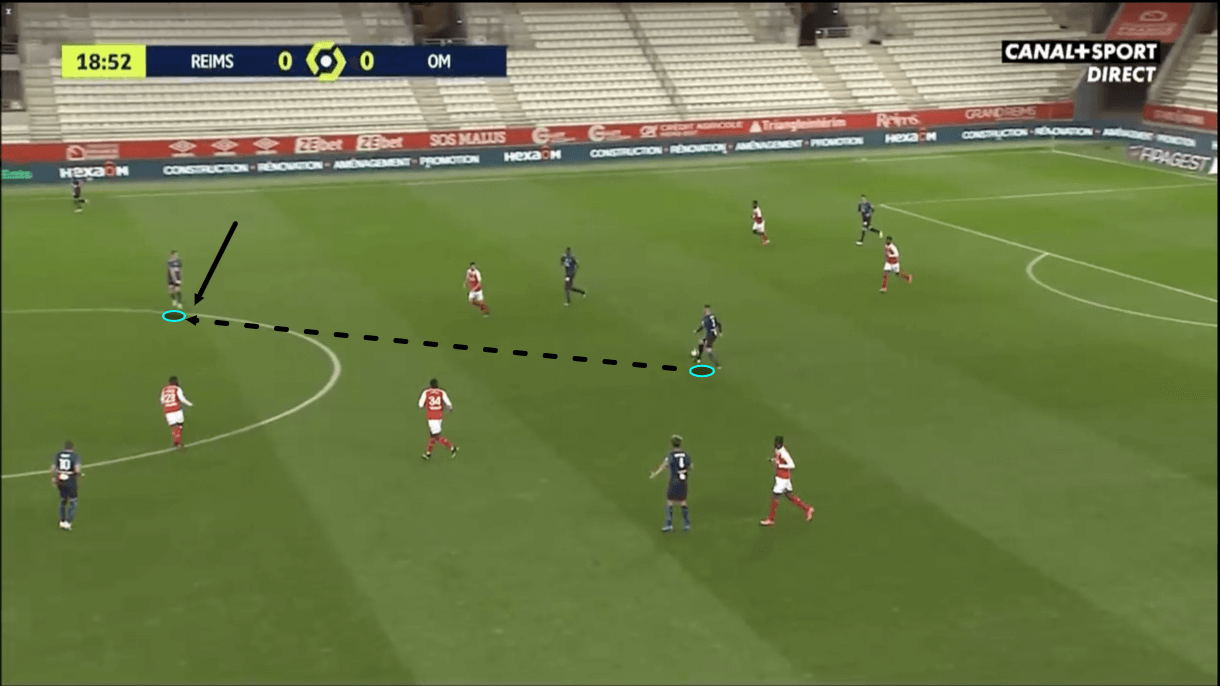

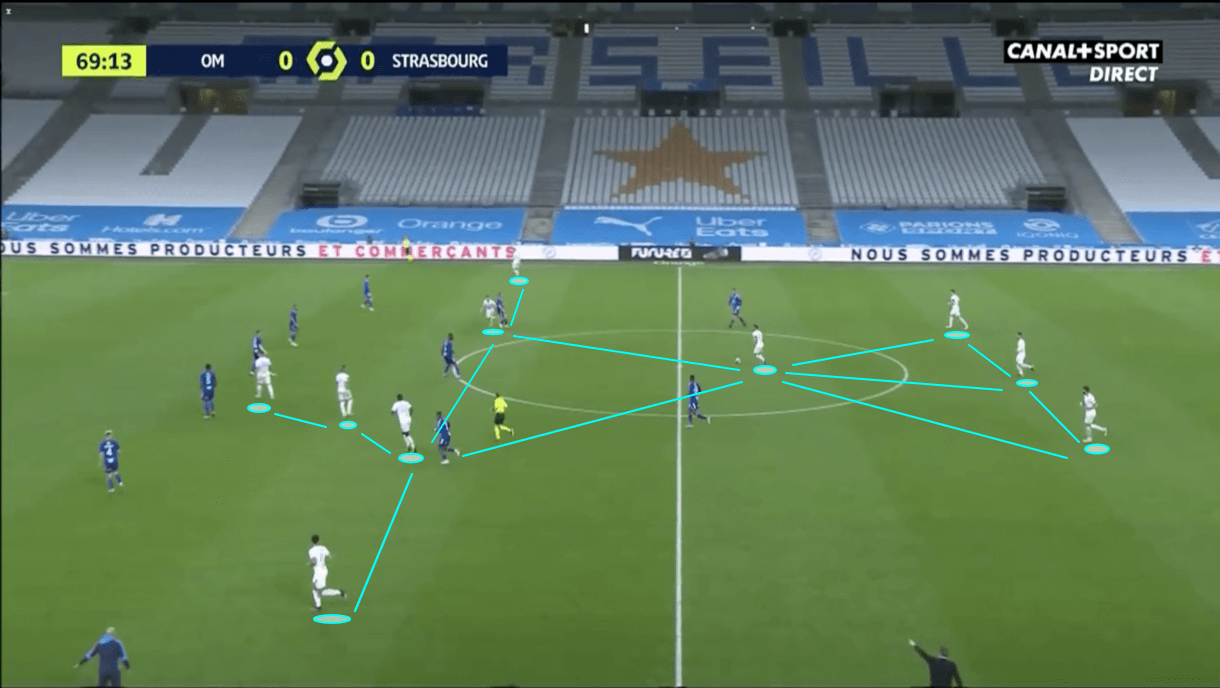

In figure 1, we see an example of how Sampaoli’s Marseille have typically shaped up from a goal-kick. At this very early stage of the build-up, two of the centre-backs – the central one and often the right-sided one, stay inside the box and sit either side of the goalkeeper. Meanwhile, the other centre-back, often the left-sided centre-back as was the case here in figure 1, pushes into more of a full-back position.

The right wing-back also drops into a full-back position on the opposite side and the two central midfielders stay in line with those full-backs, centrally. The left wing-back advances into the left-wing position at this stage, with either the ‘number 10’, one of the strikers or the right-winger – depending on the formation – taking up the right-wing position. Then, either the ‘number 10’ or one of the strikers takes up the ‘10’ position at this stage, leaving just one striker up top, to complete a 2-4-3-1 shape at this stage.

Sampaoli’s Marseille are constantly looking to play progressive passes but they’re not quick to jump to the option of playing a long ball. That’s not to say that they never play the ball long – they do – especially thanks to having the option of Arkadiusz Milik in the centre-forward position, as he offers great size, strength, aerial ability and ability to hold up the ball. As a result, it’s fairly common to see long balls played to Milik but Sampaoli’s side will only do this after searching for progressive passing options along the ground.

While this team isn’t opposed to playing long balls and have succeeded in doing so at times thanks to their centre-forward option, when playing out from the back, they’re always searching for progressive passing options that they can find along the ground – and preferably in central areas. If these options are blocked off in their natural position, as is often the case due to the opposition’s defensive tactics, then quick passing and off the ball movement is key to Marseille’s tactics at this stage, as they try to forge an opening for a progressive ground passing option in a central position.

This places importance on the ball-playing ability of their deep-lying players, such as the centre-backs, full-backs, goalkeeper and central midfielders, and a potential weakness for Marseille at this point is that with these men playing short passes amongst one another in search of progressive ground passing options, they can struggle under aggressive pressure from the opposition. They have already conceded as a result of aggressive pressure at this stage under Sampaoli and it is an area for their opponents to target.

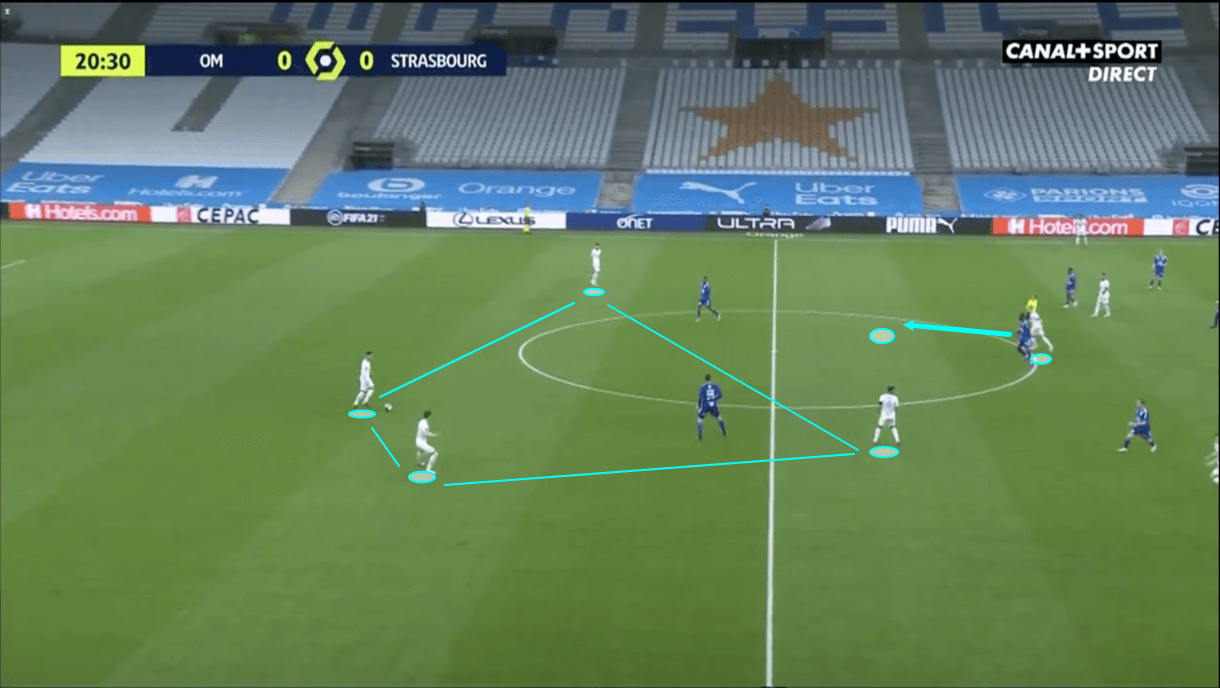

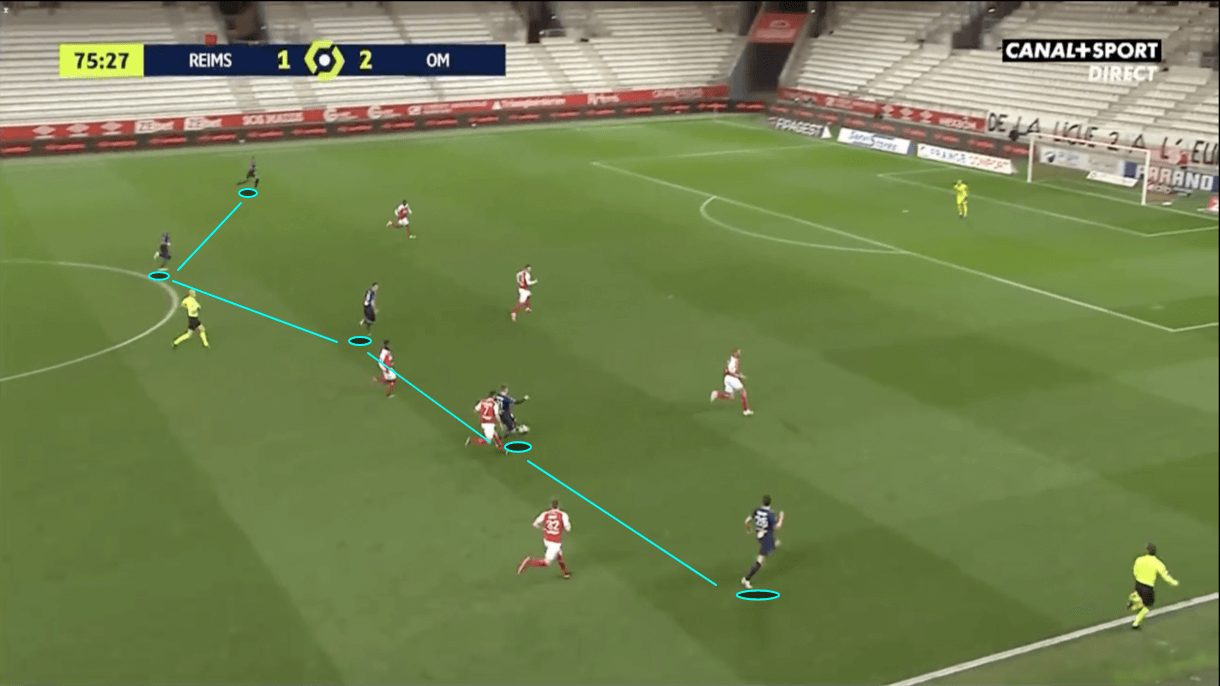

In figure 2, we see Sampaoli’s side in a 3-1-4-2 shape, which they often adopt in the build-up as they advance out of their own box and towards the central third of the pitch. Here, one of their central midfielders sits in front of the back three. These four players often form a central diamond shape at the base of Marseille’s offensive formation. This shape typically creates plenty of short passing options for whichever one of these four players is in possession at the time, helping them to move the opposition around via their passes and off-the-ball movement, to create progressive passing options in central areas.

With Sampaoli’s side looking to advance the ball through the thirds via the centre of the pitch, the holding midfielder who’s dropped in front of the back three generally plays an important role. It’s important for him to find space, and when he does receive the ball, it’s important for him to quickly turn, get his head up and look for progressive passing options.

Marseille’s wing-backs advance to provide the width in attack at this stage, with one central midfielder and the ‘10’, or one central midfielder and a winger, depending on the formation they’re playing, taking up the advanced ‘number 8’ positions. Meanwhile, one of the strikers – usually Dmitri Payet, will drop off to take up a ‘10’ position just behind his centre-forward partner – often Milik – and in front of the advanced central midfield duo. By doing so, he attempts to exploit space in between the opposition’s midfield and defensive lines, while he also attempts to help his side to overload the opposition in central midfield, creating an additional forward passing option in a central area for the holding midfielder to potentially use.

So, at this stage, Marseille typically try to play through the centre, from the centre-backs to the holding midfielder, to the 8s or 10. They achieve this via quick short passing and off-the-ball movement that drags opposition players out of position, to create space for teammates centrally.

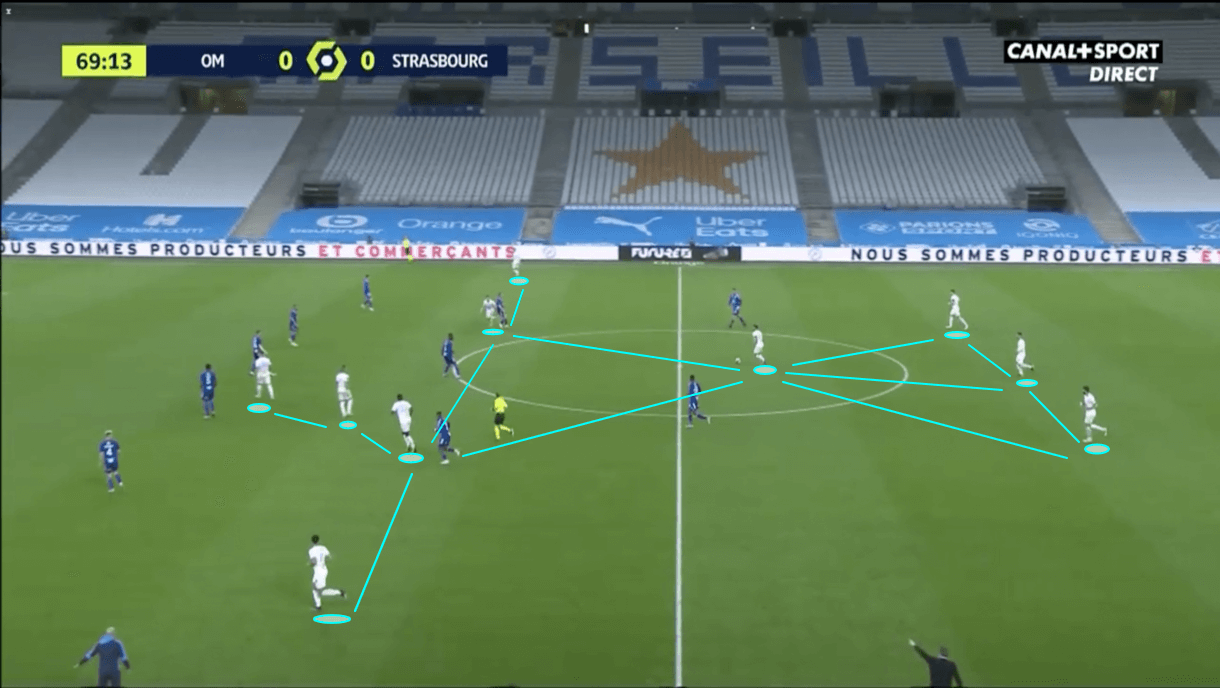

We see an example of how Sampaoli’s side uses off-the-ball movement, in particular, to create progressive ground passing options centrally in figure 3. Here, we can see that Marseille had formed their central diamond with the three centre-backs and the holding midfielder as we saw in figure 2. However, the opposition’s centre-forwards did well to block off the passing lane to the holding midfielder, with Marseille’s men passing the ball and moving around to try and make the pass possible.

Eventually, they ended up in this situation, where the pass into the holding midfielder at the tip of the diamond was blocked off, but the holding midfielder shifted over to one particular side of the pitch, creating room for one of the two 8s to drop, forming a double-pivot and turning Marseille’s central diamond into a pentagon. This player was quick to drop and exploit space in the left-sided holding midfield position which was not blocked off by the opposition’s forwards and his movement was quick enough that he managed to get in front of the opposition midfielder nearest to him in this image.

As a result, a central passing lane opened up between this centre-back and the new left-sided holding midfielder and despite the opposition’s attempts to block Marseille from playing through the centre, Les Olympiens managed to create a central passing option through their passing and movement.

It’s common to see Sampaoli’s side use tactics like this at this stage or in even more advanced stages, for example, with the holding midfielder on the ball and looking to progress play to the 8s or 10 through the centre. In that type of scenario too, we often see Marseille’s midfielders use off-the-ball movement to drag opposition markers away from a particular position and create space for another teammate to move into.

It’s also common to see Sampaoli’s side use the third man principle as they progress the ball upfield. Using the example of figure 3, the midfielder dropping on the left would receive the ball and play it in front of the right-sided midfielder. This helps Marseille to get around the opposition’s block and play into central midfield by use of the third man (the player dropping on the left). This is another key element of Sampaoli’s tactics in possession which comes as a result of their passing and off-the-ball movement.

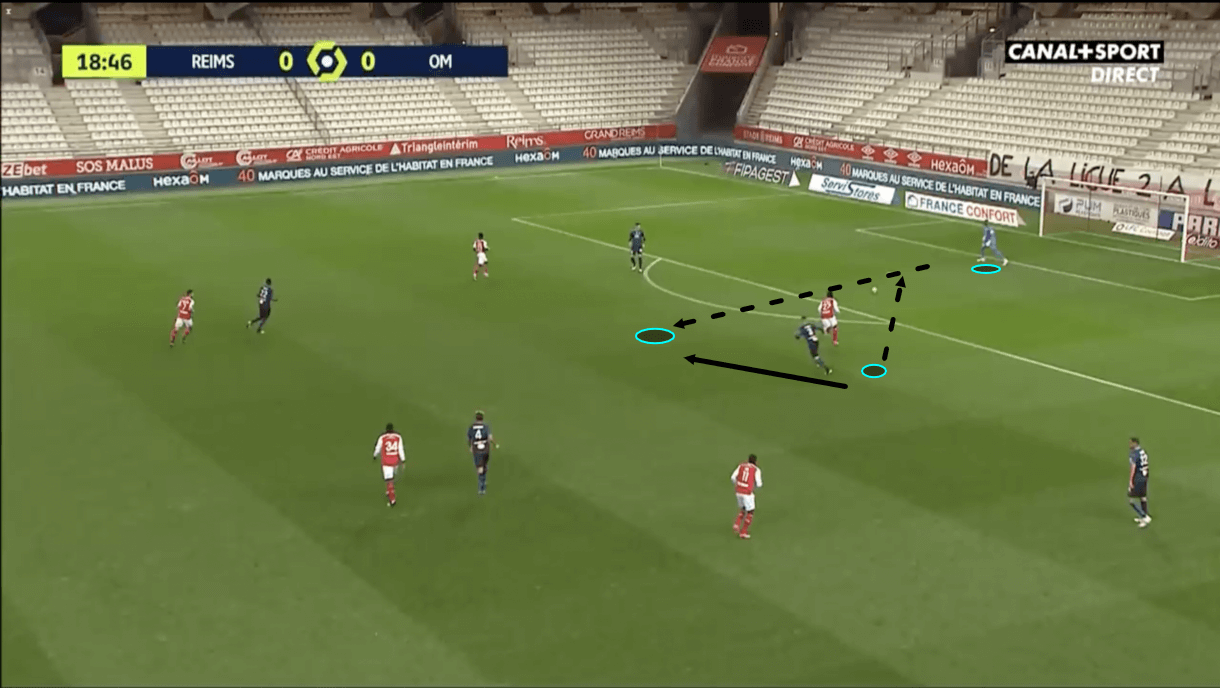

Sampaoli’s men also create additional space for themselves with their short passing and off-the-ball movement via quick one-twos played around opposition players. We see an example of this in figure 4. Just before this image, the central centre-back was in possession but due to the opposition’s aggressive pressure, both of the central midfield options were marked out of the game, while the man on the ball also came under plenty of pressure himself.

As a result of the central midfield options being blocked off, this player opted to try and get himself in a position to play the role of the holding midfielder, bypassing the need to use these players at all, by playing a one-two with the goalkeeper around the man pressing him. We can see that at this moment, he’s moving into a more central position while losing the opposition’s pressing forward by playing back to the goalkeeper.

As play moves on into figure 5, the centre-back moves into a viable position to receive a ground pass from the ‘keeper, just in front of the other two centre-backs and between the two central midfielders. As he receives the pass, his on-the-ball ability grows in importance, as he has to quickly turn and look for a progressive passing option, which he finds in the form of a wide man who’s moved into the right-sided central midfield position.

Both the centre-back and this new right-sided central midfielder represented the furthest forward progressive ground passing option for the man on the ball at the moment that the pass was played, and this is the pass that Sampaoli’s players are constantly looking to play. As they get the ball in central positions, the ball receiver generally has plenty of options all around him. This makes it more difficult for the opposition to press them effectively compared to if they received the ball out wide with less of the field to use.

Marseille have adapted quickly to Sampaoli’s tactics and this element of them has played a key role in the Argentinian’s positive start to life in Ligue 1.

Sampaoli’s Marseille in the final third

In their eight Ligue 1 games under Sampaoli, Marseille have scored an average of two goals per game. Over the entire league season, they’ve scored an average of just under 1.43 goals per game.

Les Olympiens’ increase in goals has also seen them increase their shots per 90. They’ve taken an average of 10.88 shots per 90 over the last eight games. If they managed to take that many over the course of the season, they’d have taken the seventh-highest number of shots per 90 of any Ligue 1 side, however, over the entire season, they’ve managed to take just 8.65 shots per 90, which is the second-lowest number of shots per 90 taken by any team in France’s top-flight this term.

The attacking prowess of Sampaoli’s teams is renowned and it’s clear that the Argentinian has already managed to improve Marseille in this aspect. Their tactics in the final third are a key element of this and in this section, we’ll take a look at a couple of key elements to the 61-year-old’s tactics that have contributed to their improved performance in front of goal.

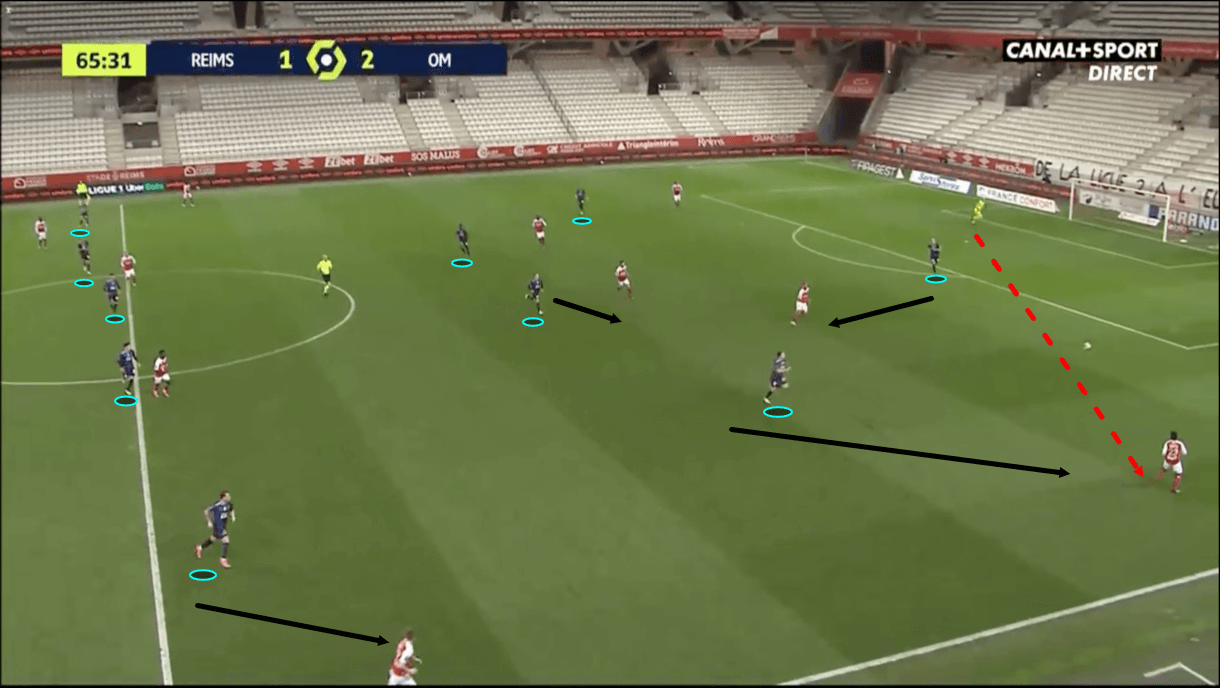

Firstly, in figure 6, we see an example of the five-man forward line that Sampaoli’s side forms inside the final third. Here, Thauvin, who typically plays in either the ‘number 10’ position or the right-wing position, is providing the width on the right, while left wing-back Yuto Nagatomo is providing the width on the opposite wing. Right central midfielder Valentin Rongier is in the right half-space, Payet is in the left half-space and Milik is in the centre-forward position.

While it’s common to see Marseille form a five-man forward line with a player on either touchline, a player in either half-space and a player in the very centre, the personnel occupying these positions varies – it isn’t very strict as to which player is occupying which position in attack, as long as all five of these channels are occupied. As a result, it’s common to see Thauvin in the half-space with the right wing-back overlapping or Payet out wide.

This helps Marseille to use the full width of the pitch in attack, as well as the central spaces in between those players that could open up as a result of the full width of the pitch being used.

The further Sampaoli’s side progress upfield, the more comfortable they become with playing the ball out wide. At the very beginning of the build-up, they try to avoid playing via the wings, doing what they can to focus their play through the centre, but at this stage, as they break into the final third, the players are given more creative freedom to use whatever areas of the pitch they want. Now, they focus more on finding players in space regardless of if they’re positioned centrally or out wide and if the man on the ball has space himself, then he’ll carry it forward.

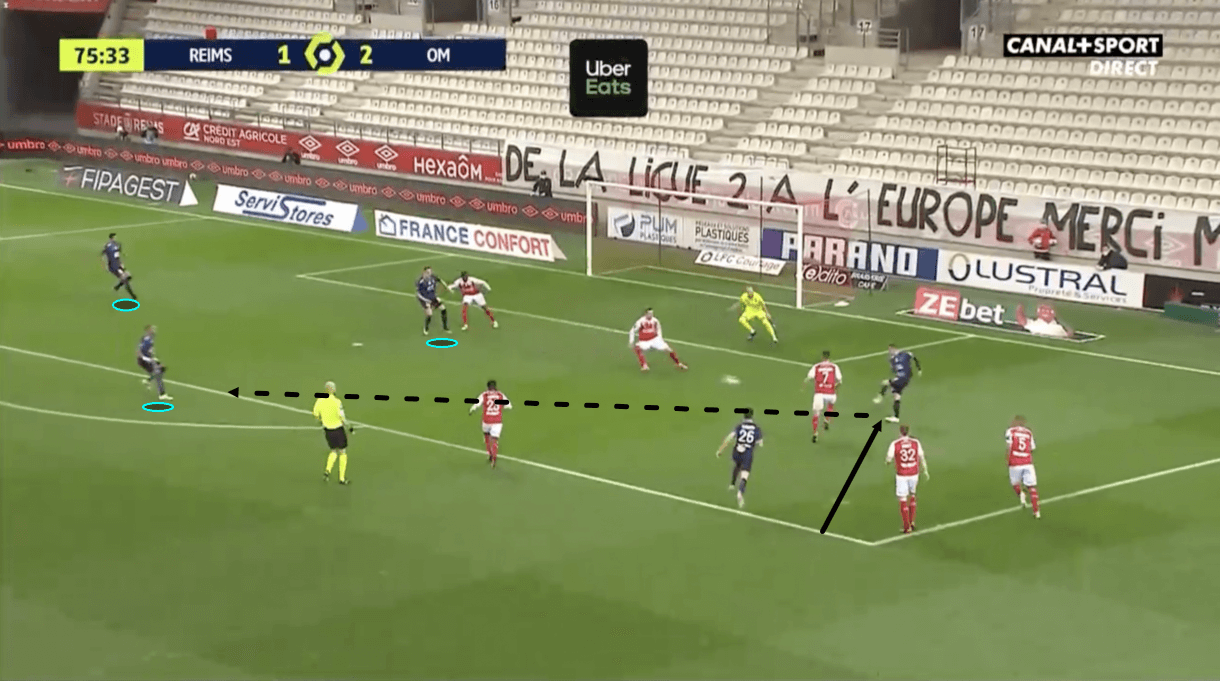

In this particular passage of play, Rongier picked up the ball deeper, carried it into this position and as play moves on, he plays the overlapping Thauvin throughout wide, with the winger then carrying the ball forward, attracting pressure from the nearest member of the opposition’s back three, creating room for Rongier in the half-space and ultimately playing a through ball to him in the box via this channel. The midfielder carries the ball towards the byline before turning and playing a cross.

Regardless of whether it’s the wide man or the man in the half-space who has the space to carry the ball into the box, it’s common to see Marseille try and get to the byline between the edge of the box and the edge of the six-yard box. They target this area and often attempt to play low cutback crosses towards a free man on the edge of the box if one is there, low drilled crosses to a forward in a more advanced position, or even lightly chipped crosses to either the centre-forward or a free man at the back post if one is there.

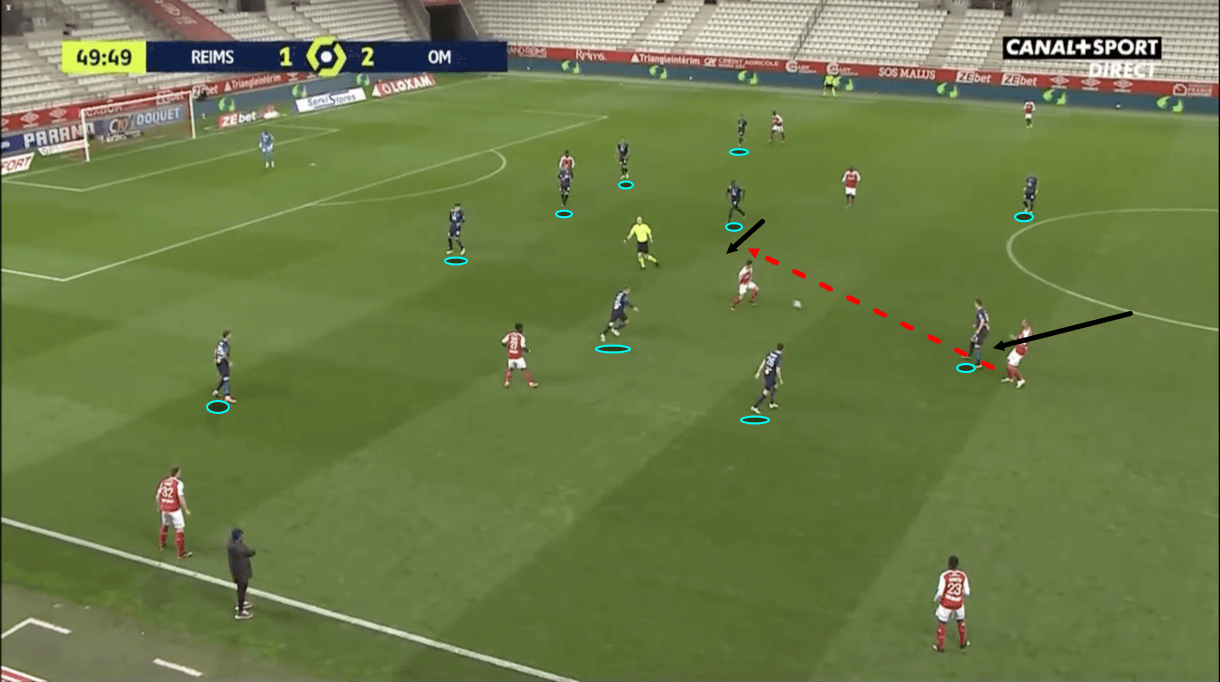

Marseille have scored several goals under Sampaoli resulting from crosses in this area, with figure 7 providing an example of one. Here, we see Rongier in the box after getting played through into the half-space and he manages to find Payet in space on the edge of the area. From there, the French attacker enjoys a free shot at goal from a good, central position, and manages to send the ball home into the bottom corner of the net.

Rongier also had a free man at the back post to aim for in this example, with his dribbling and the positioning of Milik occupying the rest of the opposition’s back three, so this attack provides a good example of several key elements of Sampaoli’s offensive tactics at Marseille, and why they’ve been so effective.

By occupying all five channels in attack, Marseille an overload the opposition’s backline and by playing the ball into space as they attack the box, they can drag opposition players out of position, creating more space for their attackers inside the box when they do get into their preferred crossing position. This is a typical Marseille attack under Sampaoli, and this is how they’re likely to continue trying to break down opposition defences as the season progresses.

However, this isn’t the only way Marseille have succeeded in front of goal under Sampaoli. As mentioned, they often play the ball straight to Milik, either aerially via a long ball or into his feet via a ground pass, with the goal of the Polish attacker playing a teammate, such as Payet, Thauvin or Rongier, into space thanks to his hold-up play.

Due to his size, strength and ability on the ball, Milik can often occupy more than one opposition defender, creating space for his teammates and Sampaoli has recognised this as a useful tool for his team in attack. When they do use this tool, it’s key that the likes of Payet and Thauvin find space within passing range of the attacker so he can create a goalscoring opportunity for them. These players often find space in between the opposition’s midfield line and backline or running in behind the opposition’s backline to exploit with Milik, so this has been another key area of Sampaoli’s Marseille in attack thus far.

Sampaoli’s Marseille in defence

It’s been said that one key difference between Marseille under Sampaoli and Marseille under Bielsa is their defensive intensity. It’s true that under Bielsa, Marseille pressed with more intensity than they’ve pressed under Sampaoli thus far. They don’t often try to win the ball with the forward line, however, that’s not to say that they defend deep and passively at all, they do defend quite high.

In this section of analysis, we’ll take a look at some key characteristics of Sampaoli’s Marseille in defence, based on their eight games so far. We’ll look at an example of the defensive shape they generally use, how they try to win back possession and a potential weakness in their defensive tactics.

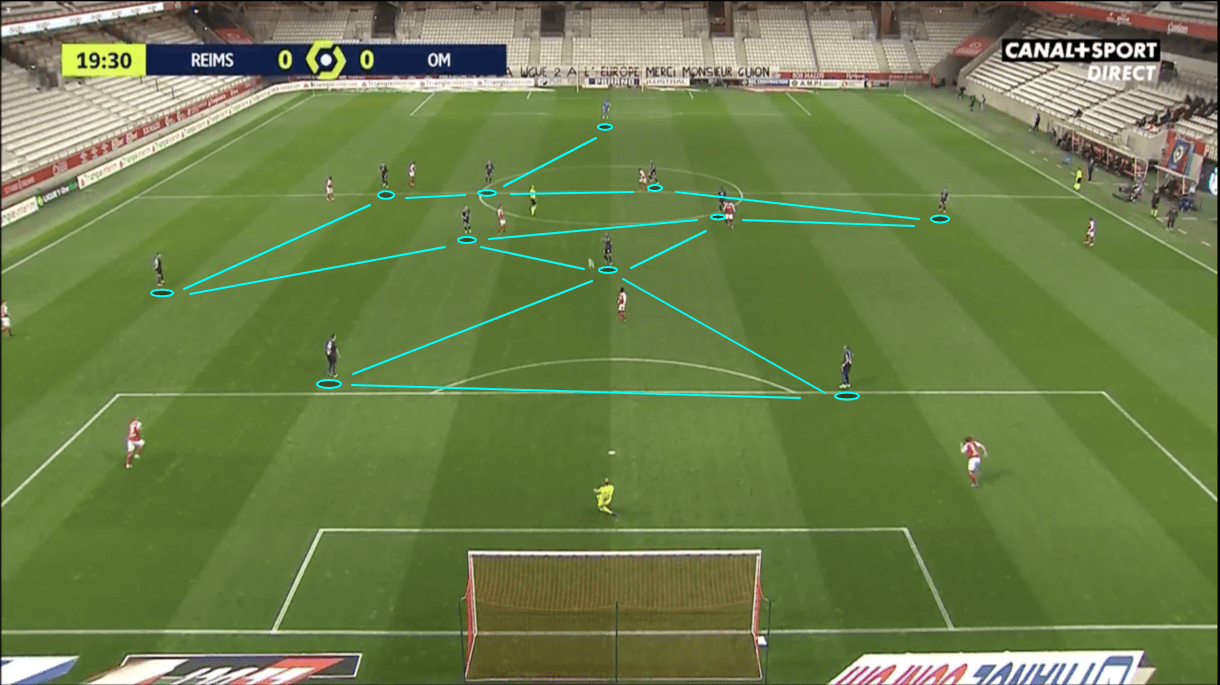

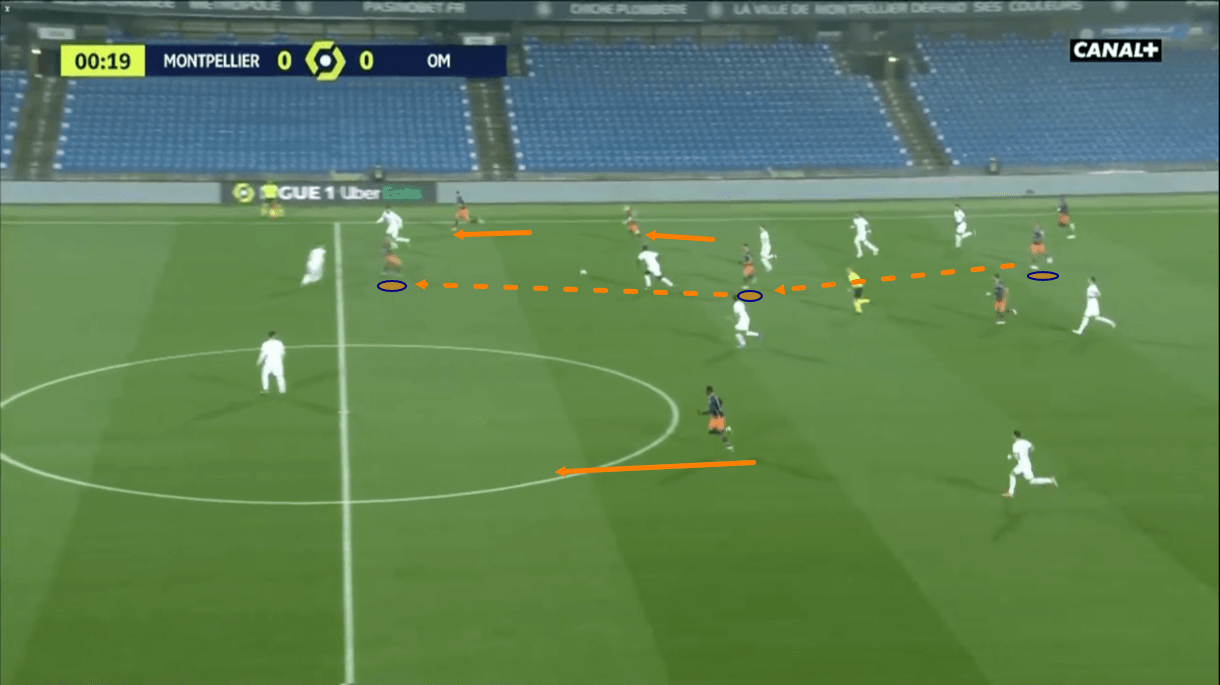

Under Sampaoli, Marseille have generally played with either a 3-4-2-1 or 3-4-1-2 shape and in figure 8, we see an example of their 3-4-1-2 shape. Their defensive tactics are mainly set up to prevent the opposition from playing through the centre of the pitch.

They don’t press from the front aggressively while the opposition build out from the back. Instead, their forwards focus more on blocking the passing lanes between the centre-backs and the opposition’s central midfielder, while the central midfielders will also be marked tightly by Marseille’s central midfielders, as was the case here in figure 8.

Meanwhile, Marseille’s wing-backs maintain access to the furthest forward opposition wide men, ensuring that they’re in position to press them should they receive the ball and ensuring that the centre-backs don’t get dragged out of position. This can leave Marseille in a 3-4-1-2, as was the case in the image above, if the opposition’s furthest forward wide men are closer to their own goal.

However, as we see in figure 9, this can also leave Marseille in more of a five-at-the-back shape if those players are further forward. This doesn’t have too much of an impact on Marseille’s pressing, however, as these players would be focused on the furthest forward wide men regardless of their exact position, with the more advanced players focusing on pressing the deeper opposition players during the build-up.

Under Sampaoli, organisation has been a key element of Marseille’s defensive tactics. Their players know where they have to be and they defend their zones diligently, ensuring that the opposition struggle to progress the ball easily, especially through the centre. Here in figure 9, Marseille’s defensive block succeeded in preventing the opposition from playing through the centre and forced them out wide.

As the full-back receives the ball, the near-sided central midfielder presses him, Marseille’s striker drops to pick up the near-sided centre-back, and the rest of Les Olympiens’ defensive block shifts over to cover the rest of the nearest passing options. This forces the full-back to either play the ball backwards or play a riskier pass to a man being marked tightly.

Marseille often press more aggressively as the opposition break into their half of the pitch, which was the case here in figure 10. As they played into Marseille’s half, the opposition’s left centre-back found himself in possession but this attracted pressure from behind courtesy of Marseille striker Milik.

As Milik dropped to apply pressure, he forced this player to pass the ball quickly, and with his nearest progressive passing options either cut off or being marked tightly, his options were very limited. As a result, the player ended up playing a misplaced pass into central midfield under pressure, which led to Marseille’s central midfielder pouncing and pulling off the interception, setting his side off on the counter. Marseille’s midfielders and full-backs are constantly looking for interception-making opportunities like this resulting from their pressure, so this is a good example of Les Olympiens’ pressing tactics.

Some space can open up between Marseille’s backline and midfield line as a result of their pressing tactics, however, and this space can be exploited by opposition movement and passes, as was the case in figure 11. Here, the opposition’s centre-forward dropped into this space that formed while Marseille pressed, giving himself an opportunity to drag a Marseille defender out of position and let his teammates run in behind Les Olympiens’ backline.

This is just one example of how Marseille’s defensive tactics can be exploited, but runs from attacking midfielders or inverted runs from wingers can also be effective at exploiting this space in front of Marseille’s backline, so this is one potential area of weakness in Les Olympiens’ defensive tactics.

Conclusion

To conclude our tactical analysis piece on Sampaoli’s first two months at Marseille, it’s clear that the Argentinian’s heavily possession-based tactics have gelled well with his new team and are already paying off in helping Marseille to create far more goalscoring opportunities than they had been earlier this term.

Sampaoli has inspired a significant improvement in his new side’s attack thanks to his offensive tactics, while he’s also got them playing with a lot of good organisation in defence. So, if he continues in this way as his tenure at Orange Vélodrome progresses, then Marseille can expect to see an exciting, attacking side develop.

Comments