The well-travelled Jorge Sampaoli took charge of Olympique de Marseille back in March with a clear goal in mind, declaring that he would put “a playing philosophy” in place at Orange Vélodrome, with an immediate focus on “fundamentals, desire, [and] rhythm”. In his 11 games in charge last season, the Argentinian guided Les Olympiens to a fifth-placed finish, having taken over a side placed well behind the top four in March.

Back in May, I wrote a tactical analysis article looking into Sampaoli’s positive start to life in southern France after Marseille won five, drew two, and lost just one of their first eight games under the 61-year-old disciple of EPL side Leeds United boss Marcelo Bielsa. In that tactical analysis piece, I observed that Sampaoli followed in Bielsa’s footsteps not only by becoming Marseille manager — a role the Leeds United man held from July 2014 to August 2015 — but by deciding to line his Marseille team up in a formation with three centre-backs, similar to how Bielsa’s Marseille set up, as opposed to a two-centre-back shape like the one previous Marseille boss André Villas-Boas typically deployed.

As well as that, it was immediately apparent that Sampaoli’s vision for Marseille was that of a more possession-dominant, pass-heavy side than that of his predecessor, a set of tactics that would fit with the typical ‘aggressive, possession-based with incisive verticality’ playing philosophy the Bielsa-inspired coach has become well known for during his coaching career.

The intricacies of Sampaoli’s first two months in charge of Marseille, including explanations for why we arrived at the previously stated conclusions of his start at Orange Vélodrome, are analysed in far greater detail in our previous ‘Sampaoli at Marseille’ article from May (linked above). I’d recommend reading that piece before this one, almost as a ‘part one’ on Sampaoli’s time at Les Olympiens.

Since then, Sampaoli has had time to mould this Marseille side into his ideal image more and more. As a result, the 61-year-old manager has made some interesting tactical changes to his team. We’re coming off the back of a summer transfer window in which the Argentinian coach was backed heavily in the transfer market, with Marseille ending the window with the second-highest net transfer spend of any Ligue 1 side, per Transfermarkt.

Cengiz Ünder and Pau López (both on loan from Serie A side Roma), William Saliba and Mattéo Guendouzi (both on loan from EPL side Arsenal), Amine Harit (on loan from Schalke), Bamba Dieng (€400k), Gerson (€25m), Leonardo Balerdi (€11m), Pol Lirola (€6.5m), Luan Peres (€4.5m), and Konrad de la Fuente (€3m) are among those to have made the move to Marseille this summer and featured heavily so far in the 2021/22 campaign in what has been a major shakeup at Orange Vélodrome. However, Sampaoli’s new-look side have started the season well, winning four, drawing two, and losing just one of their first seven league games, leaving them sitting third in Ligue 1, one point behind second-placed Lens, who have played a game more than Marseille.

Along with new faces has come some new tactical ideas to fuel Les Olympiens’ positive start to the season and this tactical analysis piece highlights three key tactical changes Sampaoli has brought to Marseille this term. This tactical analysis looks to paint the picture of an evolved version of this Marseille side that Sampaoli has tweaked to fit his vision even more this season than during his start to life at the French club at the end of last season.

Build-up, central midfielders over wing-backs, and rotations

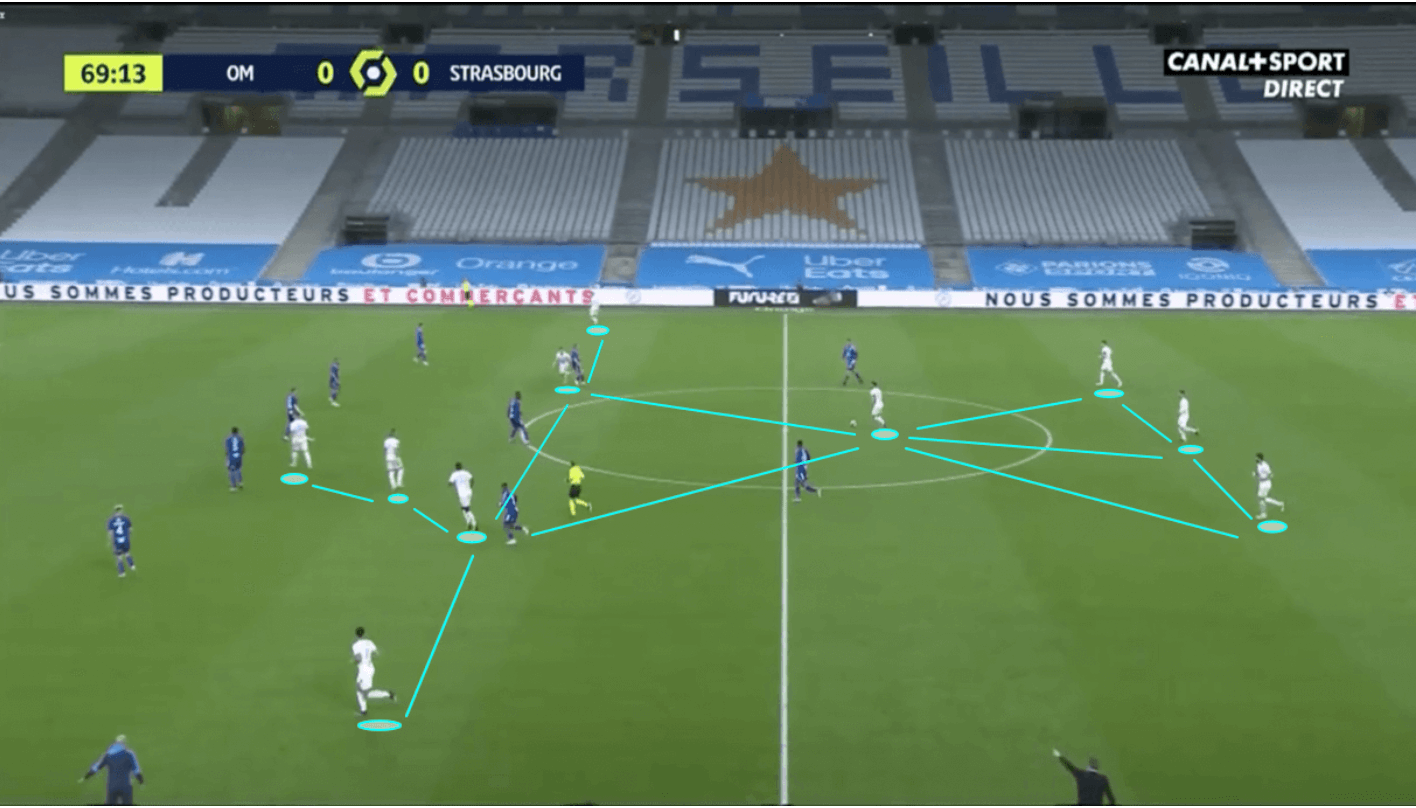

On arrival at Marseille, Sampaoli immediately switched from the typical 4-1-4-1/4-2-3-1 shape of Villas-Boas’ side to the 3-4-1-2/3-4-2-1 shape that his teams are known to play. Again, the intricacies of this immediate tactical decision are discussed in greater detail in our first piece on Sampaoli at Marseille. This switch in shape saw Marseille begin to use a 3-1 shape as a base for their build-up, with one of their two central midfielders dropping deeper to form a diamond with the back three, and his place in midfield being filled by either a winger or a striker — depending on whether Marseille were using a 3-4-1-2 or 3-4-2-1 base shape.

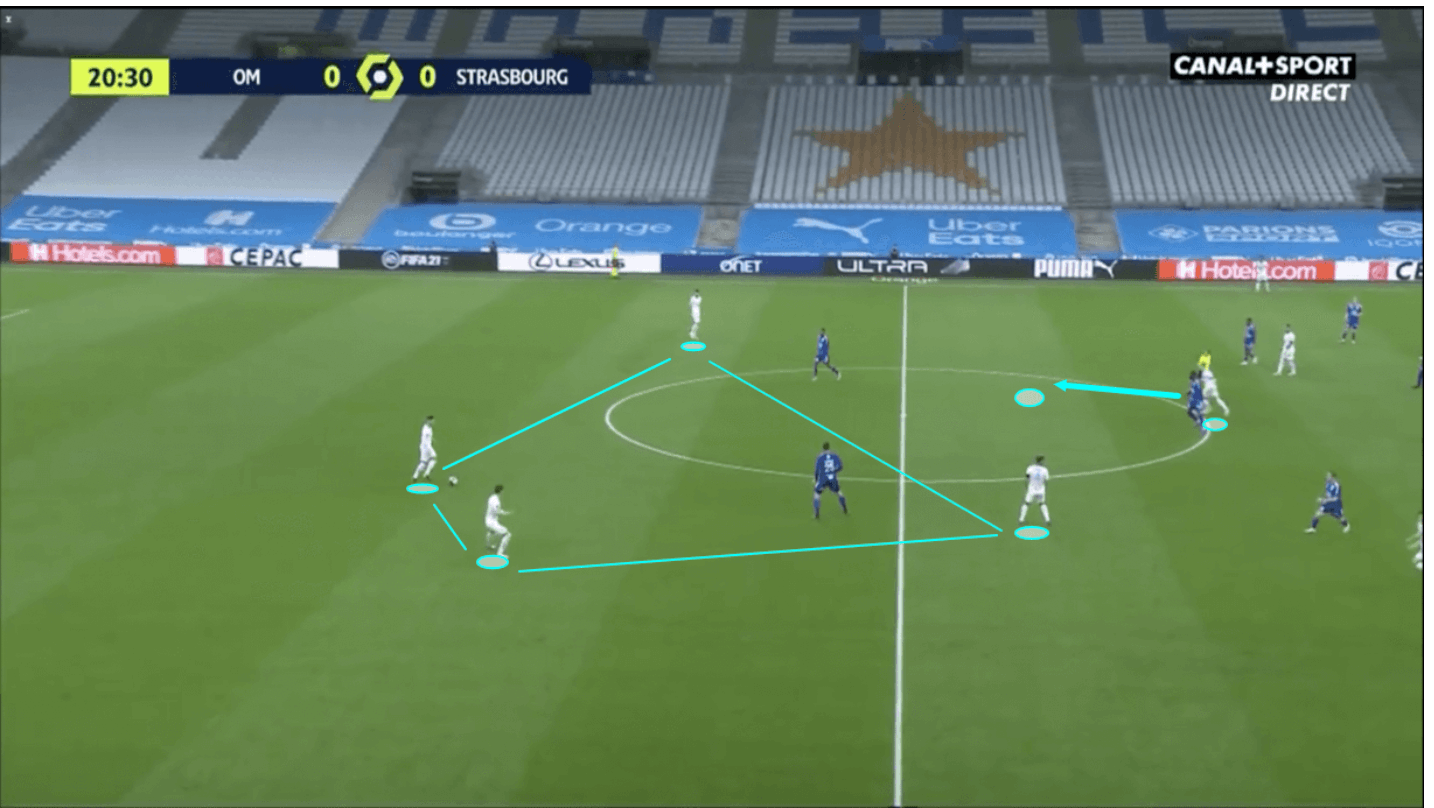

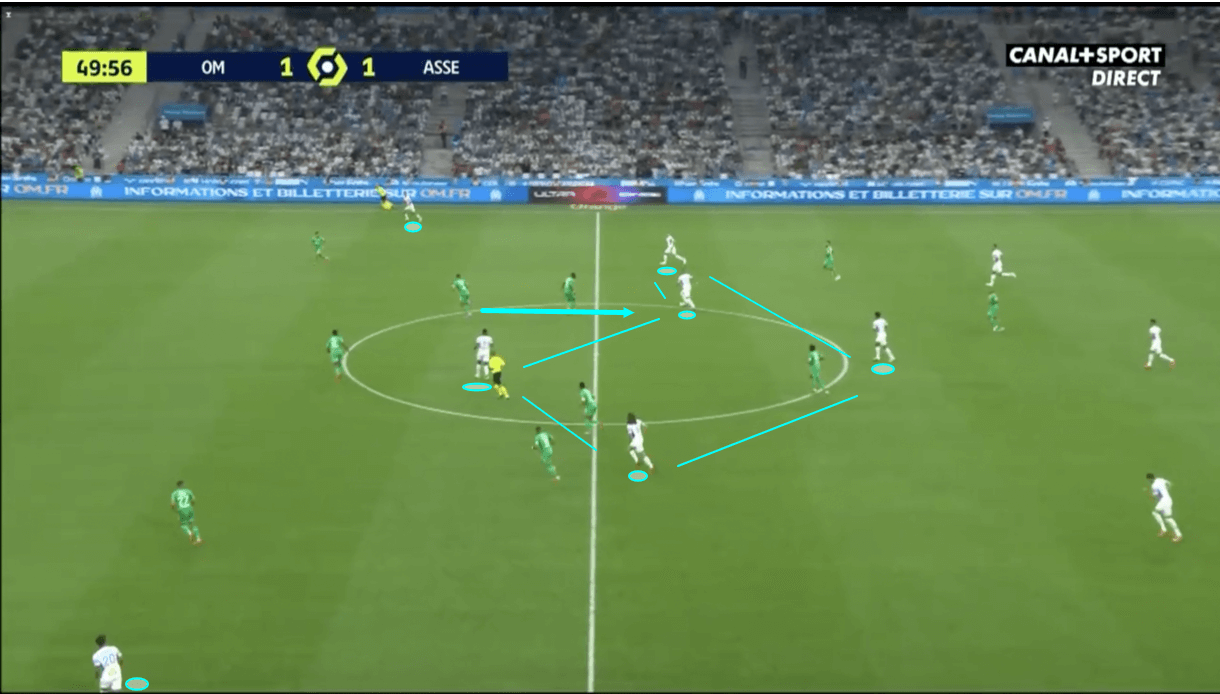

Figure 1 shows an example of Marseille’s general shape in possession under Sampaoli last season. This image highlights the 3-1 base and how the deep-lying midfielder’s place in central midfield was subsequently filled by a striker who also dropped deep, creating something of a 3-1-4-2 shape.

Marseille still use the 3-1 base in the build-up this season, that hasn’t changed. It’s a shape that creates good passing angles into midfield, and if those passing lanes into the deep-lying midfielder are blocked off for the centre-backs, then the opposition may leave passing lanes into the other central midfielders open, or at least the wide men, though Sampaoli likes his team to play through the centre if possible.

However, the rest of Marseille’s structure in possession has changed from last season.

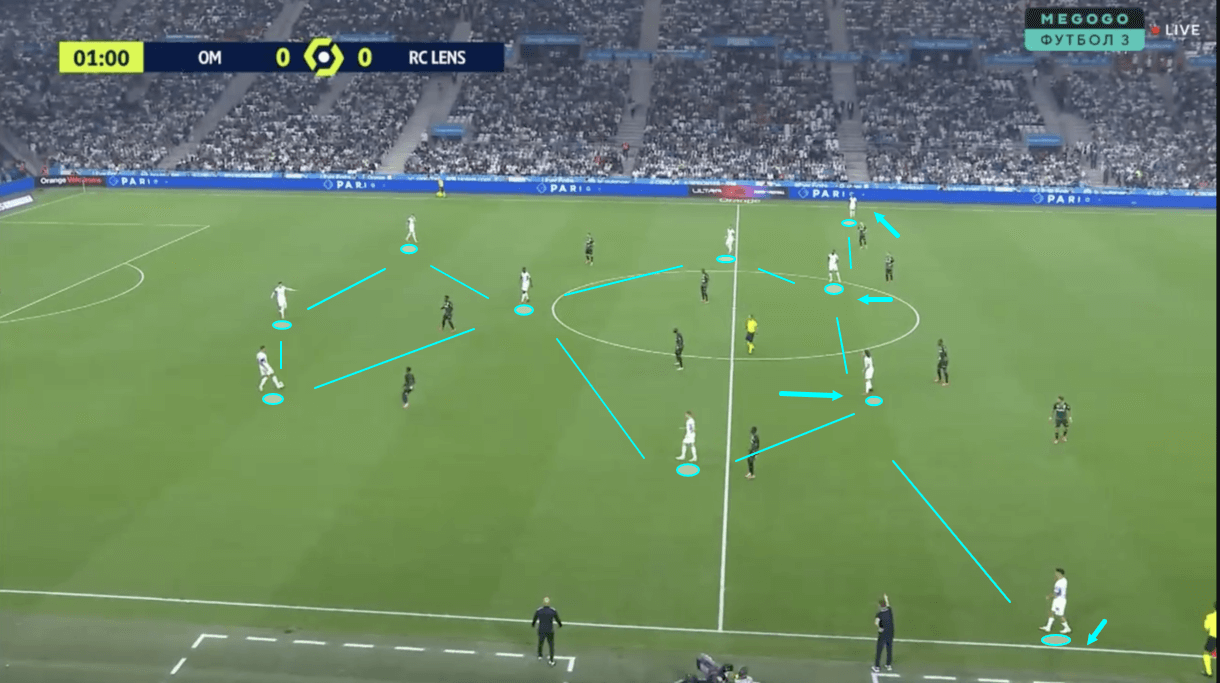

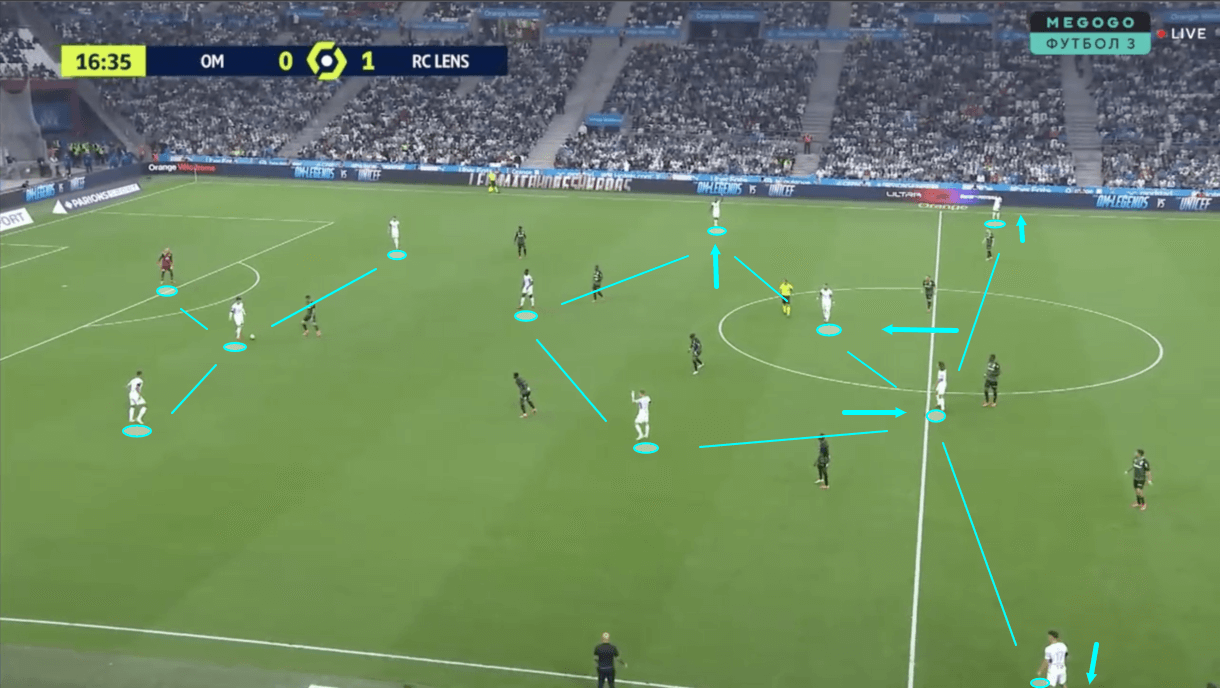

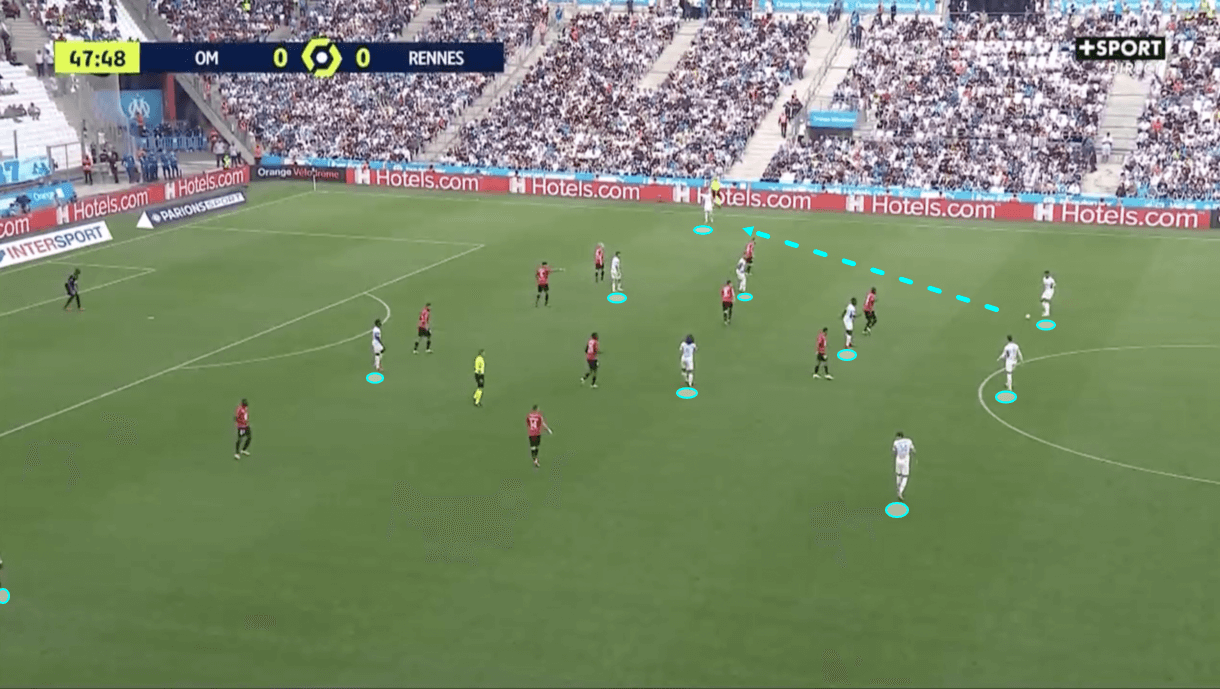

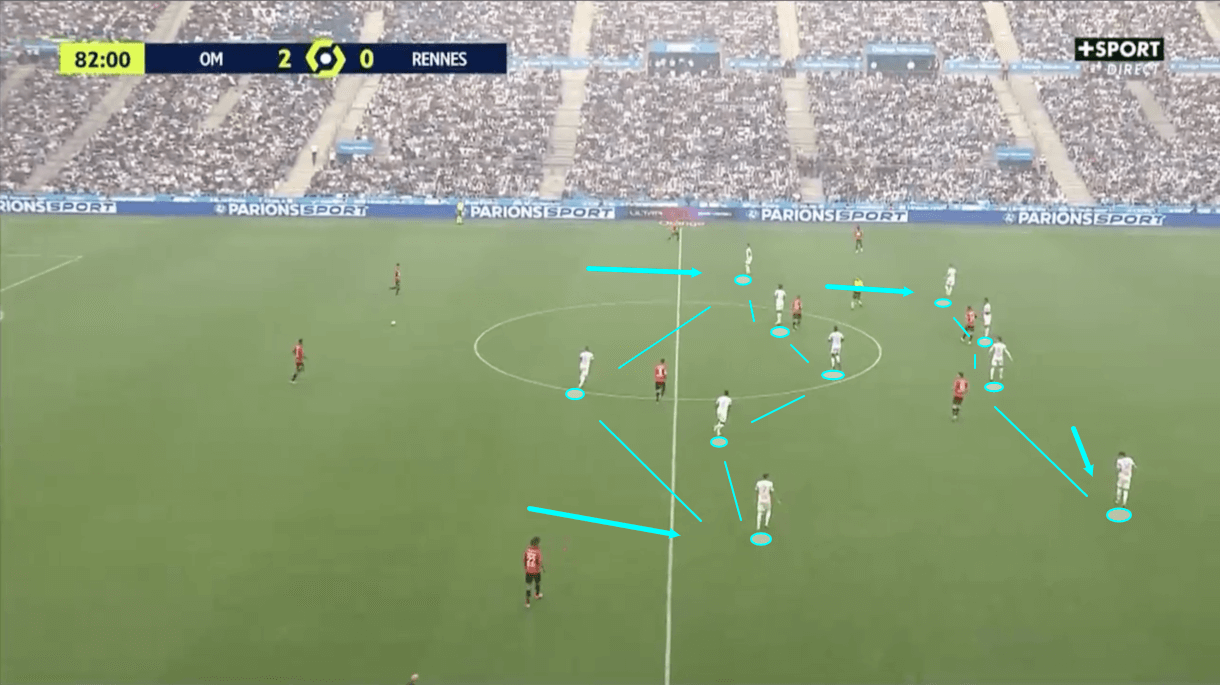

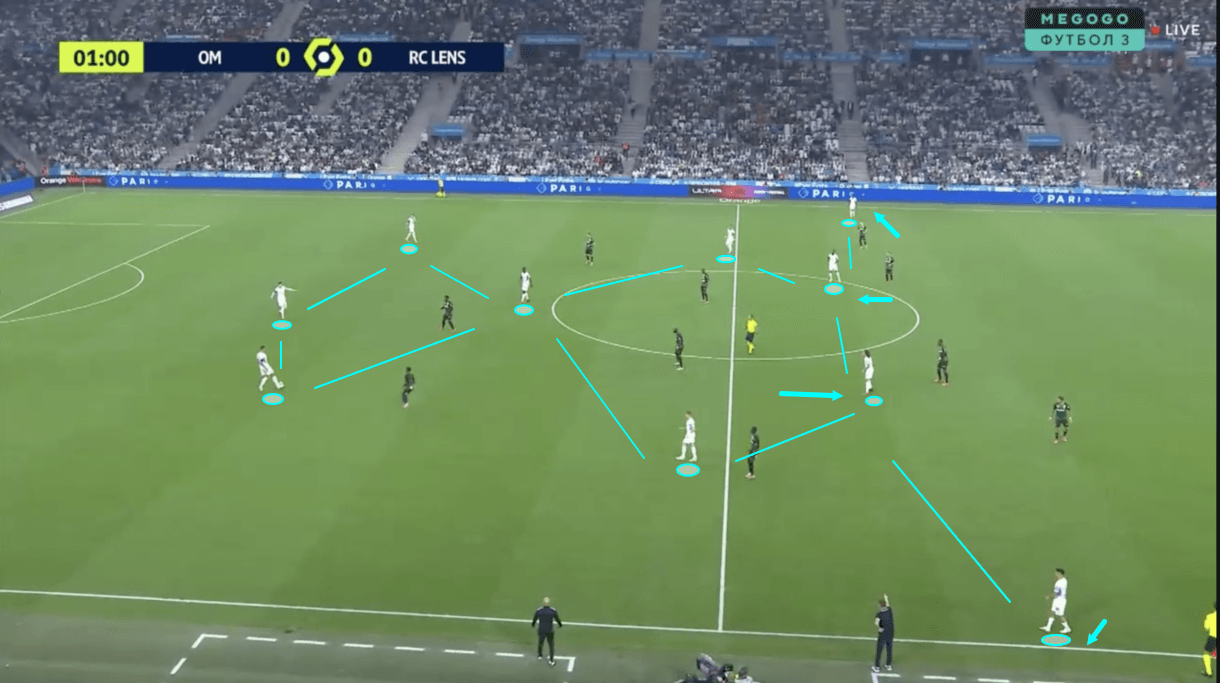

Figure 2 shows an example of the 3-3-1-3/3-1-4-2 shape that Les Olympiens have primarily utilised under Sampaoli this season. The 3-3-1-3 shape is synonymous with Sampaoli’s mentor, Bielsa, and he has used it in the past, so perhaps it’s not a major surprise to see him make this switch, but it is a pretty rare shape to see a team use and is part of what makes Marseille a unique and interesting team to watch right now.

Les Olympiens’ switch to the 3-3-1-3 from the 3-4-1-2/3-4-2-1 was facilitated by their summer transfer business. Natural full-backs/wing-backs: Hiroki Sakai, Christopher Rocchia, Yuto Nagatomo, and Mohamed Abdallah — the latter of whom was out on loan last season — all left the club. This leaves them with one recognised left-back (Jordan Amavi) and one recognised right-back (Pol Lirola), with the former having made just one 59-minute appearance so far this season and the latter having primarily played in midfield this term. Rather than signing full-backs to replace those who left, Marseille signed more central midfielders in the form of Guendouzi and Gerson, which could show a clear desire from Sampaoli to make this switch away from last season’s shape to the 3-3-1-3 of his mentor.

In figure 2, the 3-3-1-3 looks more like a 3-1-4-2 and this is something you’ll see from Marseille a lot. The centre-forward drops deep a lot, joining the ‘10’ in between the lines, which allows Marseille to form a pentagonal shape in midfield with which they can form lots of natural passing angles, overload the opposition centrally, and potentially play around the opposition with simple short passes. Additionally, the movement of the centre-forward, along with the positioning of the ‘10’ puts two players in between the opposition’s midfield and defensive lines, which essentially makes them very difficult to mark, as figure 2 might indicate.

These players are behind the midfielders and in front of the defenders, meaning either the opposition’s midfielders need to drop or the opposition’s centre-backs need to advance to cover them. If they do so, some of their teammates can exploit the space that this creates elsewhere and if they don’t, then they remain open to receive between the lines, occupying dangerous space from where they can create.

So, why the 3-3-1-3 shape? What are the advantages of this formation? In figure 3, we attempt to highlight one big benefit of this shape for Sampaoli’s side, as here we can see the whole shape at the very beginning of an attack, with the left and right-wingers standing right on the touchlines, leaving the right-winger just out of shot and the left-winger very difficult to see on the opposite side of the pitch.

During the build-up and ball progression phases, this shape helps Marseille to generally enjoy an overload in all areas except for the opposition’s last line. In this image, we see that including the goalkeeper, Marseille enjoy a 4v3 advantage in the first line, a 3v2 advantage in the next line, and a 2v1 advantage in the next line. The opposition does enjoy a 4v2 advantage at the back, but Marseille attempt to exploit this area in a different way — almost temporarily ignoring the centre, unlike with the rest of their lines, and focusing on exploiting the space the opposition leave unmarked out wide while protecting the centre — we’ll discuss this use of width in greater detail later on in this tactical analysis piece, however.

You could say: teams won’t always press like this, in this exact shape, so surely Marseille can’t always enjoy this kind of advantage? However, the simple answer for this is that they prioritise overloading the first line by one and then working their way up from their applying the same principle from a base 3-3-1-3 shape. As a result, you do see players move around at times — maybe a central defender will join the midfield line or a midfielder will push up to join the ‘10’ and centre-forward — but in general, Marseille will effectively resemble what we see in figure 3 and Sampaoli uses this shape to try and enjoy a numerical superiority as far as the opposition’s backline, which will hopefully (for him) help his side to progress to the final third, where they will try to exploit space out wide and give other players time to advance from deep and attack the backline.

This principle of having a one-man advantage in the first line is something that Bielsa and Sampaoli live by. Sampaoli began using this tactic on arrival at Marseille last season, with one of his three centre-backs opting to advance off the ball into a higher line if playing against a less aggressive press where the opposition have got just one man in the forward line, as opposed to two or three.

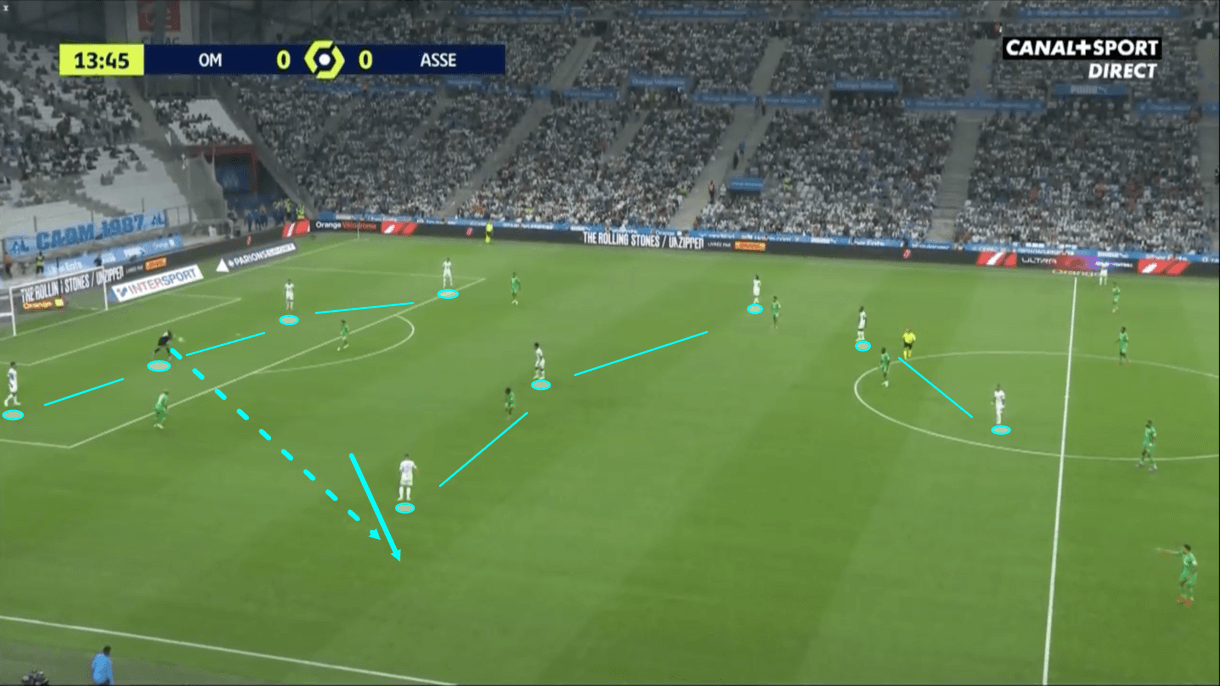

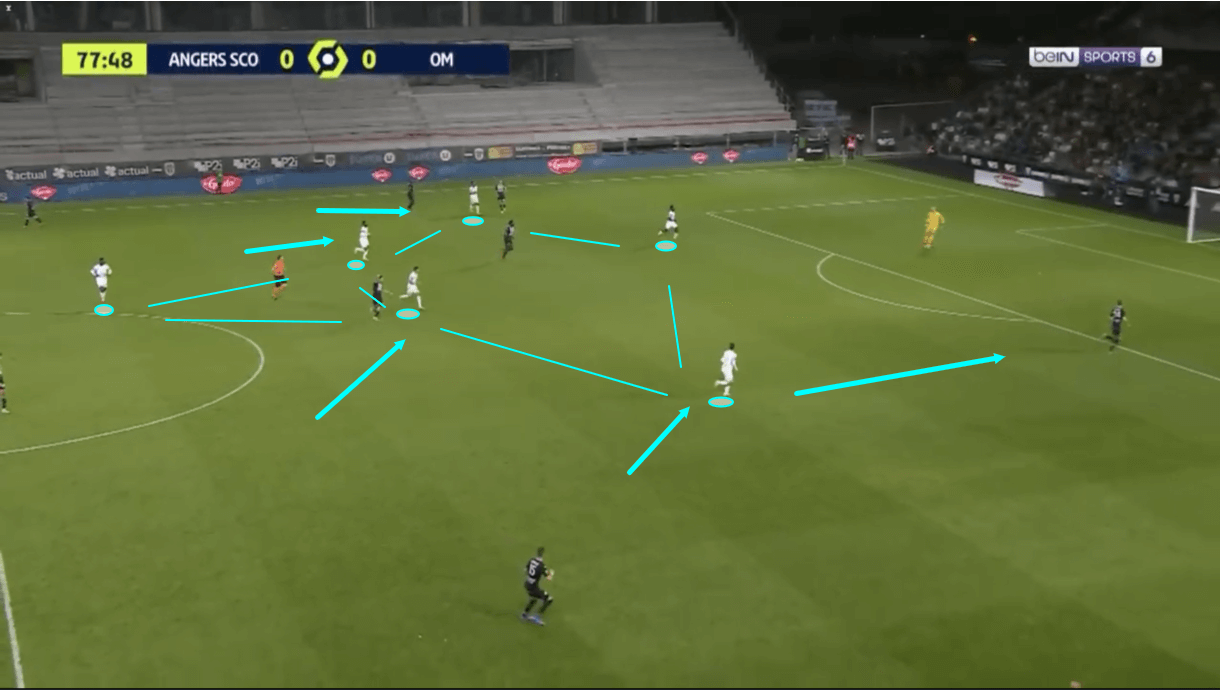

Figure 4 shows an example of Marseille continuing to utilise this tactic this season. Here, we see Angers pressing with one forward, while Marseille were initially building up with their regular three-man backline. Although this still leaves Sampaoli’s side with the numerical advantage, it’s too much. We know from our analysis of figure 3, explanation of the advantages of the 3-3-1-3 shape and Sampaoli’s application of it, that this would leave Marseille without their numerical advantage in perhaps the next line or the line after that.

As a result, Marseille’s central centre-back advanced beyond his central defensive partners and occupied the typical holding midfielder position, allowing Marseille’s other players to advance or push wider to exploit space there — the latter of which we see the left centre-back and right central midfielder doing in this image.

The left centre-back’s movement, in particular, is significant as it helped to open the passing lane into the now-advanced central centre-back. The left centre-back’s decision to drift wider made it impossible for the opposition’s striker to cut off the passing lane to him or the central centre-back while still posing a threat to the other one. It leaves him in this position where he’s effectively stranded, doing more to block the passing lane into the left centre-back than the central centre-back, allowing Marseille’s ‘keeper to send the ball into the advanced central centre-back’s feet. As play moves on, this player receives and turns before continuing to progress play through midfield, highlighting the benefit of his decision to move further upfield.

Marseille essentially always started with the 3-1 base under Sampaoli last season. However, at times, opposing teams did well to block off passing lanes into the holding midfielder who Sampaoli likes his team to build through when possible. In this case, one of Marseille’s more advanced midfielders sometimes dropped to form a temporary double-pivot that, again, was movement designed to help Les Olympiens play past the opposition’s first line of pressure. We see an example of Sampaoli’s side doing this in the 2020/21 campaign in figure 5.

While this was part of Les Olympiens’ game last term, Marseille haven’t really done this exact movement in the 2021/22 season, but their central midfielders do still move about off the ball in the build-up and ball progression phases when the initial shape doesn’t provide them with enough opportunities to progress play. However, now, instead of dropping centrally into a temporary double-pivot, it’s far more common to see Marseille’s central midfielders drop out into the wing-back positions which are now naturally vacated in this shape, with Sampaoli opting for more central midfielders over wing-backs this season.

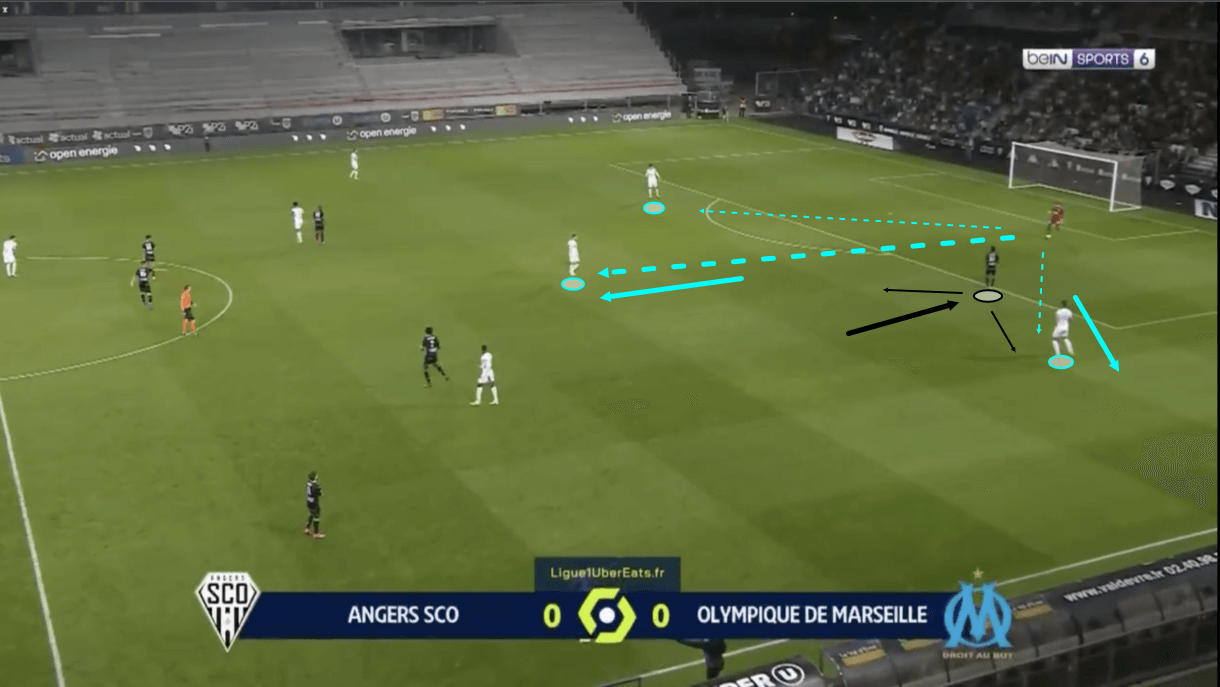

Figure 6 shows an example of Marseille’s left central midfielder in the 3-3-1-3 shape dropping out wide into more of a wing-back position during the build-up. Here, the opposition were set up in a very horizontally compact shape that protected the space in midfield well, which makes sense given that Marseille’s 3-3-1-3 is set up to overload the centre. However, this allowed space to open up on the wing for Sampaoli’s side to potentially exploit, which the left central midfielder opted to try and do by drifting out wide in this image.

It’s really common for Marseille’s opponents to get extremely horizontally compact to try and protect central midfield against Marseille’s 3-3-1-3 shape. This is especially made possible because, except for the wingers who are generally positioned quite high, Marseille’s shape doesn’t offer a lot of natural width so the opposition don’t have to worry about this space being exploited so much. However, as was the case in figure 6, it’s also very common to see Les Olympiens’ wide central midfielders drop out wide, into what would’ve been the wing-back position in Marseille’s 3-4-1-2/3-4-2-1 shape last season, to exploit this space.

Marseille’s centre-backs and holding midfielder will often look to get the ball out to this wide midfielder quickly when he makes this movement to make the most of the space he enjoys out wide while it lasts. This can help Les Olympiens to quickly progress through midfield and start attacking the opposition’s backline, which makes the midfielder’s movement very useful in the early possession phases.

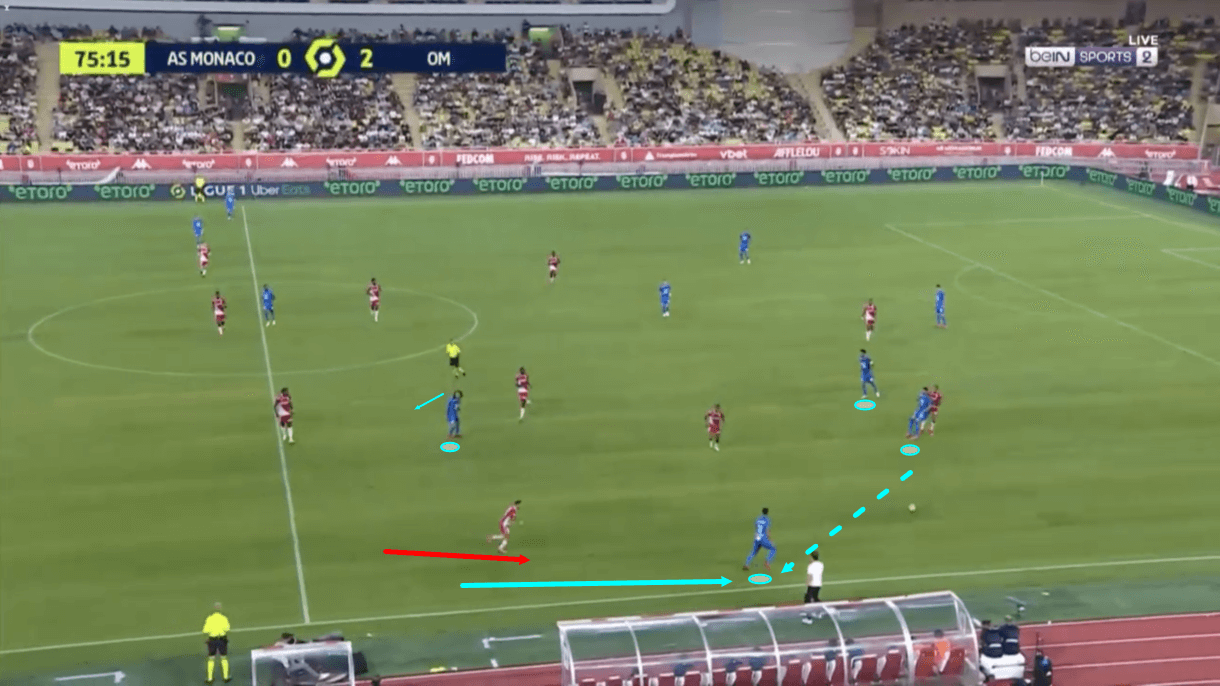

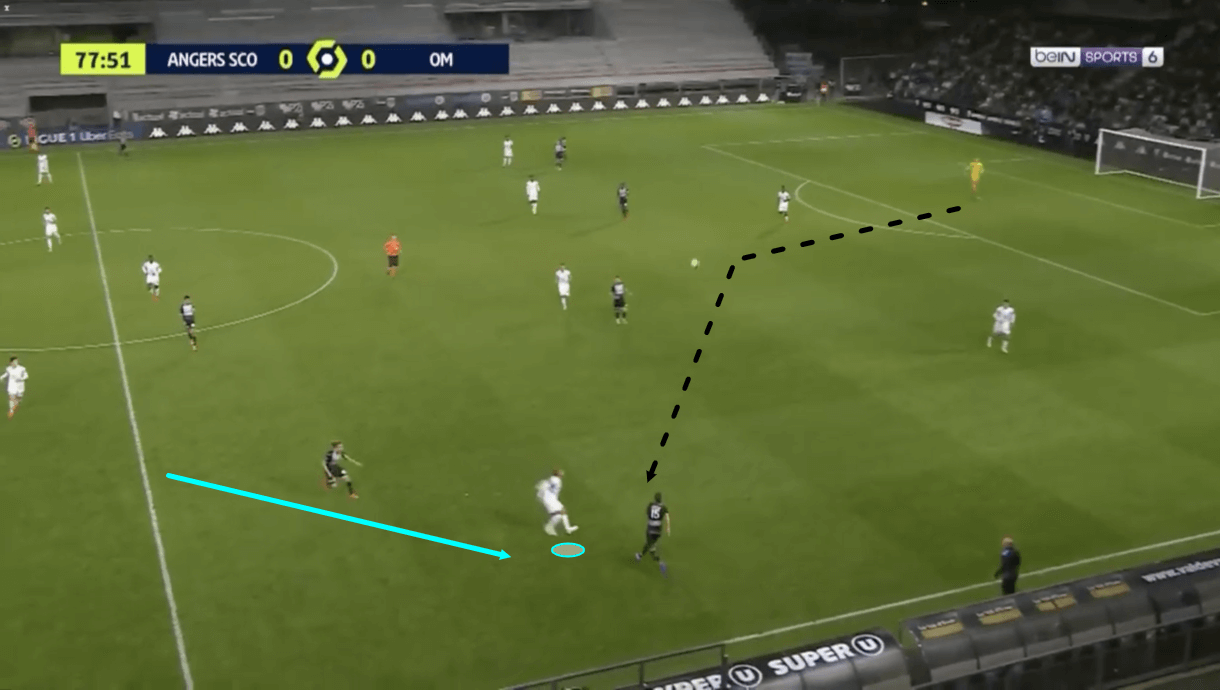

Marseille’s central midfielders also enjoy license to push out onto more advanced positions on the wings during the ball progression phase. Figures 7-9 will highlight a passage of play in which the central midfielder, Guendouzi, pushed out wide into a high position to exploit space behind the opposition’s full-back as he followed Les Olympiens’ winger deep. Firstly, figure 7 shows how this passage of play began, with Marseille’s left centre-back carrying the ball out of the backline, forming a wide triangle with the central midfielder and winger (wide rhombus if you want to include the holding midfielder, who doesn’t play a significant role in this particular passage of play). Marseille’s shape naturally forms lots of passing triangles like this one, which helps these three players to link up via quick passing sequences.

As the left centre-back carries the ball out from the back here, Marseille’s left-winger opts to drop deeper — a relatively uncommon, but not entirely extinct movement in Marseille’s system — to offer himself as a short passing option out wide for the centre-back.

In figure 8, we see that as the pass is played to the winger and Monaco’s right-back continues to advance out of his base position to press the receiver, Marseille’s left central midfielder, Guendouzi, intelligently scans over his right shoulder to observe the space opening up on the left-wing that he intends to exploit.

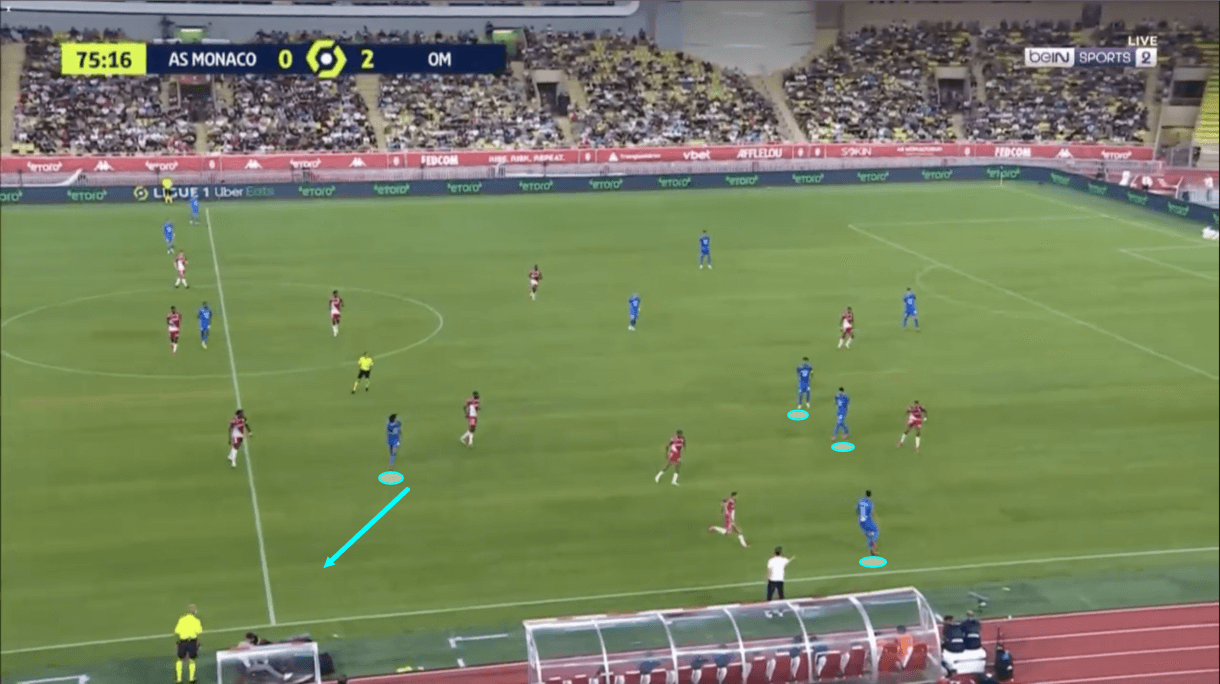

Then, in figure 9, we see that as the left-winger received the pass and Monaco’s right-back was pressing very high, Guendouzi was making his move out onto the left-wing, rotating with the winger to try and exploit the space behind the aggressive full-back. This opens up the possibility for Marseille’s winger to send the ball back to the centre-back, who could then find Guendouzi in space out on the wing behind the full-back. This is a less common movement to see the central midfielder make than the movement out into the wing-back position, which the winger occupies here. However, when the winger opts to drop deep on occasion, this is something to watch out for, as Sampaoli effectively always wants his side to have a player positioned very high and very wide, which we’ll analyse in greater detail in our next section. If that’s not the winger, then the central midfielder will look to become that man and exploit the space that opens up behind the full-back defending against the deeper winger, as figures 7-9 show.

Exploiting width versus the opposition’s backline

As mentioned in the previous section, Marseille’s wingers — two of the final three in that 3-3-1-3 shape — generally sit very high and very wide. Although they might drop off on occasion, opening up space for, perhaps, a midfielder to push out wide behind the opposition’s full-back if he follows them, they’re typically more stationery than most of the other players in this team off the ball.

Last season, it wasn’t always Marseille’s wingers who provided the width for this team in attack. Sometimes, one of the wingers did stay wider, but at least one of the wing-backs was also typically very active in attack, in which case they would provide the width for their side in attack. This season, with Sampaoli having had more time to work with his team on the training ground and mould them even more into his vision, Marseille’s attacking structure is more organised and the wingers are designated the task of providing width in attack. New signings Ünder — a left-footed winger who typically plays on the right — Dieng, and Konrad — two right-footed wingers who typically play on the left — normally perform these roles in Sampaoli’s system.

Regardless of where the ball is on the pitch at a given moment, you’ll generally see these wingers sitting right on the opposition’s last line of defence and right on the sideline.

We see an example of this in figure 10, which also provides another example of Marseille’s 3-pentagon-2 shape that often forms during periods of possession when the centre-forward, often Dimitri Payet, drops off to join the ‘10’ in between the lines. These five men in midfield, along with the three centre-backs behind them who provide support and are also positioned quite centrally, can completely overload the opposition in midfield, which was the case in this example. However, it’s worth noting the wingers’ positioning. As mentioned, both men typically stay very high and very wide regardless of whatever else is going on, and that was the case here.

Here, Marseille’s five-man midfield are seen linking up with one another via short passes, which is made easier thanks to their central overload. The centre-forward’s decision to drop in between the lines leaves the opposition’s centre-backs in a strange position, as they don’t have anyone to play against at this moment, which can be a very uncomfortable feeling for a centre-back. Meanwhile, the opposition’s full-backs are staying close to the centre-backs, preventing space from opening up in the channels between them which Marseille’s midfielders could exploit via a creative forward run or pass. This leaves space on the outside, which Les Olympiens’ wingers are there to exploit.

In the previous section of analysis, we saw how Marseille’s setup helps them to overload the opposition’s first line and then in midfield, but this ultimately means the opposition will have more men at the back versus Marseille’s forward line. Les Olympiens are happy to allow this and instead try to exploit the remaining space in this area — on the wing — prioritising numerical superiority at the beginning of their attacks, closer to their own goal.

This can, of course, result in some effective build-up play followed by attacks breaking down when they reach the final third, but Marseille’s 14 goals in seven league games is as many as all but three teams have managed to score in Ligue 1 this term, so in general, this is proving to be an effective strategy and it’s certainly a fun one to watch.

The positioning of Marseille’s wingers increases their availability for receiving longer passes from all positions, especially when the opposition’s defensive shape is pulled to the other wing. For example, should Les Olympiens overload one side of the pitch before looking to switch to the other, the wingers’ constant high and wide positioning means that they’re always an outlet for that switch of play and their teammates always know where they are, which helps to increase speed of play.

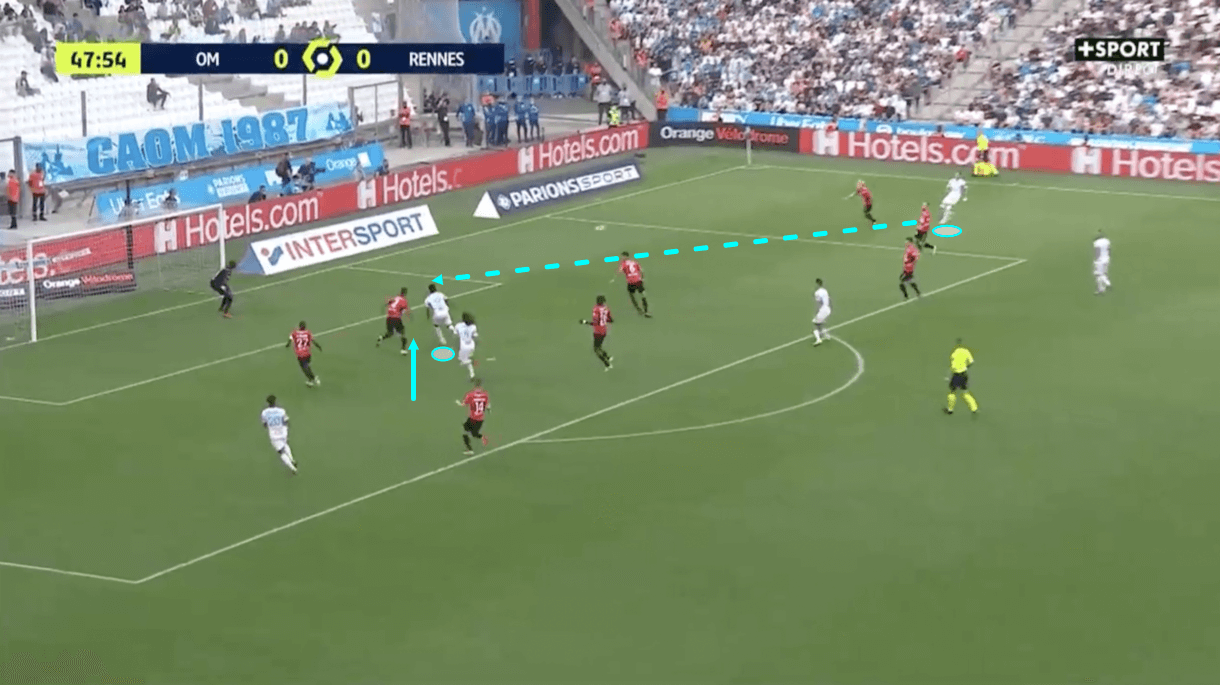

The wingers’ high and wide positioning can be especially valuable and effective inside the final third, when opposing teams will generally look to get very compact — both vertically and horizontally — to protect the central routes through to their goal. This will only increase the amount of space that Marseille’s wingers can enjoy on the wings, which figure 11 shows an example of.

Here, Marseille are operating in the chance creation phase, in possession of the ball inside the opposition’s half, with the opposition defending in a compact low-block. Under Sampaoli, Les Olympiens have become a very possession-dominant side. Last season, in their first eight games under Sampaoli, Les Olympiens kept an average of 58.4% possession. This was an increase on their average possession percentage under Villas-Boas, as they’d kept an average of 52.8% possession throughout the entire 2020/21 campaign by that point. This season, they’ve kept an average of 61.4% possession in Ligue 1 so far — the most of any side in France’s top-flight.

They tend to build attacks carefully, opting to try and ensure that they advance to the point we see them in figure 11 by taking their time on the ball a bit more. Their care in possession may be highlighted by the fact that they’ve had the second-fewest ball losses (75.78 per 90) of any Ligue 1 side this term. This sees them play — not slowly — but with a slower tempo than, say, Mauricio Pochettino’s PSG play with.

When they get to the point seen in figure 11, they will, of course, look to forge openings in the centre and take advantage of them if they can, but they’ll also look to squeeze the opposition into this central area, just like in figure 10, through the sheer threat they pose via their heavy central presence and impressive technical ability.

After manipulating the opposition to squeeze into the centre, if they fail to create an opening centrally, then they’ll pull the trigger on playing the ball to the free man out wide. In figure 11, for example, after squeezing the opposition centrally, Marseille’s right centre-back sent the ball out to the right-winger.

As play moves on into figure 12, then, the right-winger could attack the opposition’s box and send a cross in, finding Dieng who finished well at the near post.

So, from this example, we see how Marseille can use the high and wide wingers to exploit space out wide inside the final third, before then attacking the backline and potentially creating a good goalscoring chance, as was the case here. Overall, from this section, we see that the wingers’ constant high and wide positioning in this system present plenty of benefits to Marseille from an attacking perspective, in all possession phases.

Switching to a four-man backline off the ball

In our final section of analysis, we’ll take a look at how Sampaoli’s side has been playing without the ball, in defensive phases, this season. There’s been some notable differences in how Sampaoli’s side has been defending this season, compared to last season, which we’ll try to highlight in this section. The most notable difference is that Marseille have switched to playing with a back-four without the ball, the purpose of which we’ll discuss in this section of analysis.

Firstly, figure 13 shows an example of the 3-4-1-2 shape that Marseille used both in and out of possession during the early days of Sampaoli’s tenure at Orange Vélodrome last season. They attacked with the 3-4-1-2 (or 3-4-2-1) and defended with the same shape when operating in a high-block — later dropping into more of a 5-3-2 as they entered the mid-block and low-block phases.

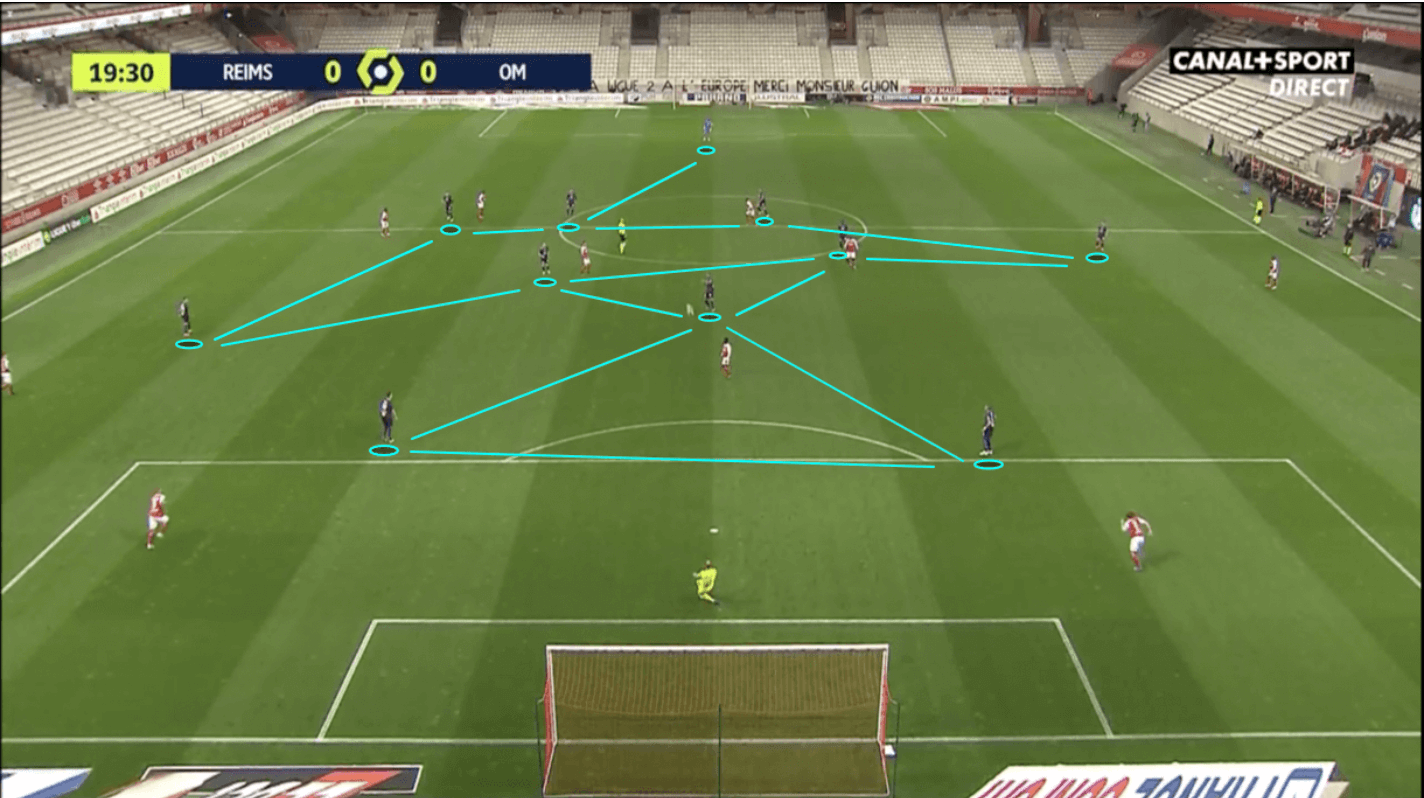

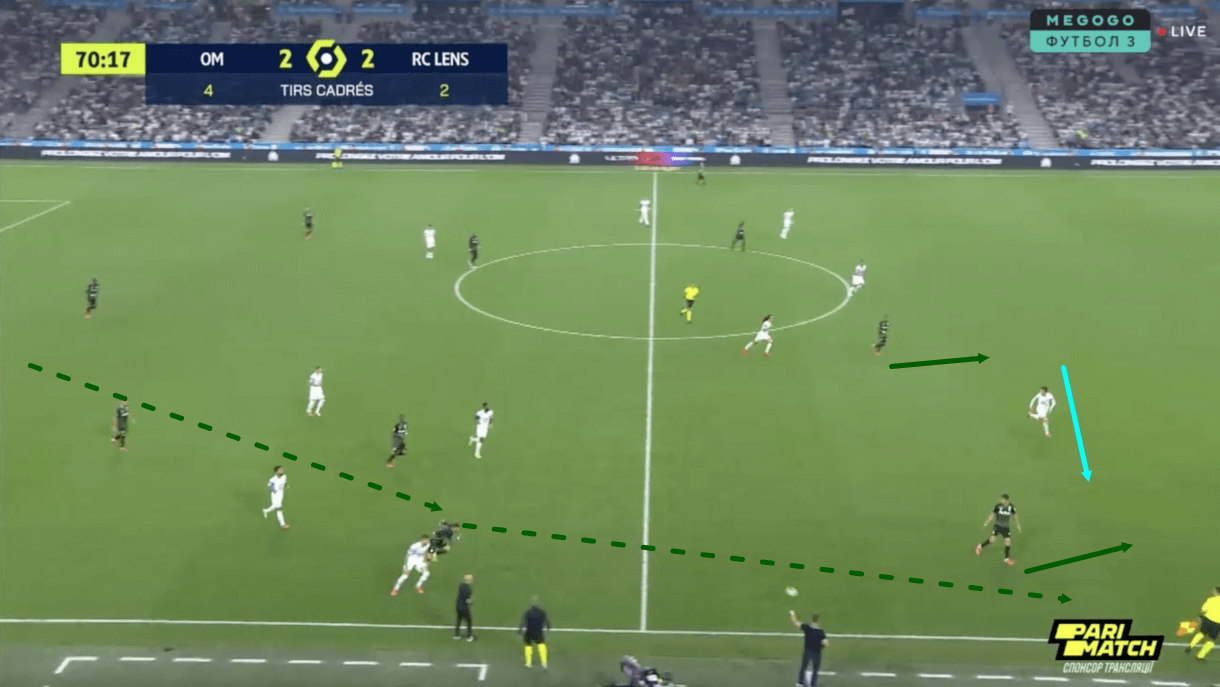

This season, however, Marseille have typically lined up in more of a 4-1-4-1 shape — like the one they used under Villas-Boas — without the ball, in the high-block, mid-block (pictured in figure 14), and low-block phases. So, how do Marseille form this defensive shape seen in figure 14 from the 3-3-1-3 that they utilise in attack? Although the formations are quite different to one another, Sampaoli has prepared his team well to make this switch when transitioning to playing without the ball.

Firstly, either the left or right central midfielder will drop into the backline, taking up what would be the full-back position in this shape, and the entire backline will shift over to the opposite side, with the far-sided centre-back taking up the other full-back position, allowing Marseille to form a typical back four. In figure 14, Marseille’s right central midfielder dropped deep, while the three-man backline then shifted over to the left.

Then, Marseille’s ‘10’ takes up the vacant position in central midfield, and the wingers drop deeper and come more narrow, leaving the high and wide positions that they always occupy in possession in favour of the wide midfielder positions that are typical of the 4-1-4-1. This results in the shape we see in figure 14.

The purpose of this switch is to provide Marseille with greater coverage across the width of the pitch. While the 3-3-1-3 is great at helping Marseille to create central overloads on the ball, one of its biggest weaknesses is the lack of width. We saw how movements into wide areas and positional rotations between players help Les Olympiens to get around this in possession to an extent, but without the ball, Marseille would simply not have enough coverage out wide, leaving the centre-backs with too much space to have to try and defend in the backline.

As a result, Sampaoli’s got his side transitioning into a 4-1-4-1 off the ball, as this shape provides much greater coverage across the width of the pitch and, as we’ve just explained, despite the two shapes being very different to one another, it doesn’t take a tonne of movement to transition between them and with the time he had on the training ground over the summer, the elite Argentinian coach has his side making these transitions quite naturally.

While figure 14 showed us an example of Marseille defending in the 4-1-4-1 during the mid-block phase, figure 15 shows an example of Les Olympiens pressing in this shape during the high-block phase.

Here, the opposition were trying to play out from the back but just before this image, Marseille did a good job of protecting the centre — preventing the opposition from playing through that more threatening area of the pitch — funnelling the opposition’s build-up play to one side of the pitch — in this case, it was the opposition’s right-wing — before their defensive shape then pushed up and got compact around that side of the pitch, with the near-sided winger pressing the man on the ball, the central midfielders staying close to the pressing man and continuing to protect the centre, the striker blocking off the passing lane across to the opposite centre-back and the far-sided winger retaining access to that opposite centre-back, just in case the opposition managed to play out of the press, which was, ultimately, the case in this example.

Here, the man on the ball was prevented from moving centrally due to Marseille’s compact shape and heavy protection of this area and was prevented from progressing upfield due to the aggressive pressing winger just in front of him. As a result, his options were limited but he managed to play the ball back to the goalkeeper, who could switch play across to the far-sided centre-back, who then attracted pressure from Marseille’s right-winger. We see Marseille’s winger springing into action as the ‘keeper sends the ball to the left centre-back in figure 15.

Before moving on, it’s worth recapping that Marseille’s press is designed to 1. Protect the centre and prevent the opposition from playing through them 2. Funnel play to one side 3. Attack the ball carrier aggressively while retaining a compact defensive structure which, as a result, continues to protect the centre and retains access to the backline in case the opposition play past the press. If one of Marseille’s central midfielders has two men to mark — one more central and one wider — he will always prioritise protecting the centre, allowing the opposition to play to the wider man. After funnelling the ball out wide, Marseille can press more aggressively, using the limitations imposed on the opposition by the sideline to their advantage when pressing the opposition out wide and cutting off their short passing options, as figure 15 shows.

As play moves on into figure 16, the opposition ended up sending the ball long, in search of the left-winger who was in some space behind Marseille’s aggressive midfield line. This seems a sensible decision, as Marseille had cut all of the short passing options out of play. However, in figure 16, we see that because the opposition were forced to go long, Marseille’s new make-shift ‘right-back’ in the defensive phase had time to get across and contest the aerial duel, resulting in this long ball creating a 50/50, with plenty of Marseille players just ahead to potentially win the second-ball.

From this passage of play, we see the benefits of Marseille’s aggressive 4-1-4-1 press, in that it prevented the opposition from playing out via short passes and forced them long, as well as the fact that Les Olympiens’ decision to switch to a four-man backline provided them with greater coverage in wide areas, so they had someone in position to contest this aerial duel, for example, when the ball was sent long.

One potential area of concern for Marseille without the ball is still their vulnerability on the wings before they switch to their four-man backline. This is something that opposing teams have exploited to some success this season, as seen in figure 17. While Sampaoli has got his side transitioning quite naturally, it does still take some time and in moments of transition, this means that Marseille’s weakness on the wings isn’t protected and can be exploited.

In figure 17, the left centre-back is forced to come across to defend the wing, as Marseille are caught in transition before they’ve had a chance to switch to the 4-1-4-1. This create a big gap between the left centre-back and the central centre-back, which one opposition attacker is attempting to exploit via his run, while another opposition attacker is threatening to directly exploit Marseille’s weakness on the wing via his run, which is met with a through ball.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis piece looking at Marseille’s evolution this season under Sampaoli, it’s clear that the Argentinian coach is implementing a lot of unique and exciting ideas at Orange Vélodrome, which is resulting in some really interesting football being played. So far this term, Sampaoli’s side has been very successful in the league, and long may it continue when the entertainment value is so good and Sampaoli’s ideas are so interesting.

While Marseille aren’t perfect and do still have some potential weaknesses, which we’ve discussed, it’s clear that the team has benefitted from more time under Sampaoli this season and do look to be a more complete version of his vision than they did when he first took over. That’s not to say this is the finished article just yet, but Marseille’s evolution is an interesting one to keep an eye on under this unique coach.

Comments