Speaking in an interview back in the summer of 2019, legendary Portuguese manager José Mourinho cited the importance of adaptation in life by paraphrasing the founder of evolution, Charles Darwin:

“It’s not enough to be one of the strongest ones. It’s not enough to be one of the best ones. It’s not enough to be one of the most intelligent ones, it’s also very important, or even more important, to be able to understand and to adapt to certain things.”

This quote emerged prior to Mourinho’s appointment at Tottenham Hotspur. However, at Spurs, his willingness to adapt was not apparent. Mourinho’s Tottenham were dogmatic, conservative, and uninspiring, and this ultimately cost ‘the Special One’ his job.

For all his mentioning of adaptation, Darwin’s quote was seemingly lost on him, until this season when he took charge of AS Roma in Serie A. Beginning the campaign using his preferred 4-2-3-1/4-3-3 formations, the 59-year-old was forced to adapt his tactical approach quickly.

Despite starting life with I Giallorossi well, results nosedived off a cliff in October and November. Something needed to be done, or Mourinho risked losing his third job in three years.

The solution was something Mourinho had hardly ever done throughout his illustrious managerial career — a switch to a back three.

This article will be a tactical analysis of José Mourinho’s use of a three-man defensive line in the Italian capital and it will provide an analysis of the team’s tactics in their newfound 3-5-2.

Mourinho’s tactical evolution

During Mourinho’s rise to prominence which was spearheaded in the 2003/04 campaign when Porto lifted the UEFA Champions League under his guidance, the manager’s favoured formation was the 4-3-1-2.

However, on arrival in England for the first time, the 4-3-3 quickly became his go-to shape when Chelsea appointed him to replace Claudio Ranieri in the Stamford Bridge dugout in 2004/05. This 4-3-3 was highly successful as the Blues lifted back-to-back Premier League titles from 2004-2006.

Nevertheless, after Mourinho left Chelsea and took his first job in Italy with Internazionale, the renowned coach reverted to his prototypical 4-3-1-2, before switching to a 4-2-3-1 during the treble-winning season in 2009/10.

The 4-2-3-1 became his conventional system of choice for his proceeding jobs at both Real Madrid and his second stint at the Bridge with Chelsea, where Mourinho established himself as one of the greatest managers ever.

Interestingly, in his final two jobs before moving to Rome, there was a common trend and a dynamic shift never seen before from the perverse Portuguese. At both Manchester United and Spurs, Mourinho sifted between the 4-2-3-1 and the 4-3-3 for the most part. However, when his tenure at the two European giants drew to a tragic close, the manager attempted to integrate a back three system as somewhat of a final throw of the dice.

That being said, neither side ever looked overly comfortable in his back three variation. This is a stark contrast to AS Roma. I Giallorossi, after some torrid results, switched to a back three and have looked quite impressive in this shape.

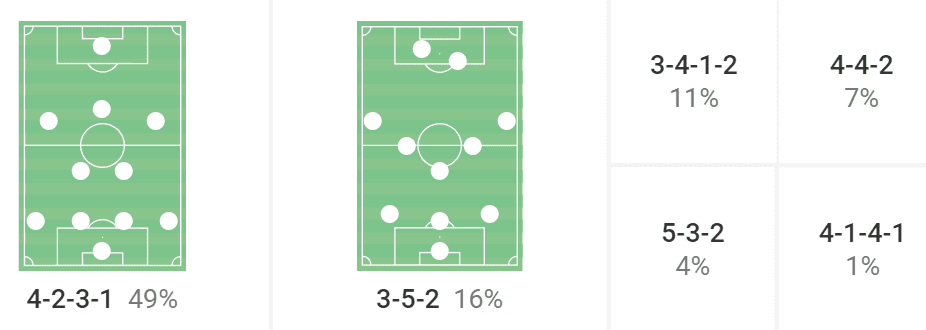

So far this season, Roma have deployed a variation of a back three formation in 31% of their matches in all competitions. This is the most Mourinho has used a back three system in one campaign throughout his lustrous managerial career.

Back three formations are becoming commonplace once more in Serie A, which has an almost comforting, nostalgic feeling. Roma have now joined the back three brigade and have looked rather comfortable in this shape.

Of course, this has been helped by the fact that Mourinho’s predecessor and compatriot Paulo Fonseca used the 3-4-2-1 for a lot of his two-year reign at the Stadio Olimpico so the transition has been smoother for the Roma players under Mourinho than it was at United or Spurs.

But Mourinho’s three-man backline is used differently from his precursor. So, how exactly has the Special One’s 3-5-2/5-3-2 worked in the capital?

High-pressing

While analysing a José Mourinho team, it would be exceptionally blasphemous not to start with the team’s tactics in the defensive phases.

Despite common belief, Mourinho’s teams do press, typically in a man-oriented fashion with each player being assigned a specific man to mark during this phase. While the man-marking scheme is rigid, the players are given different instructions from the manager in every game depending on the opponent on the day and their choice of formation.

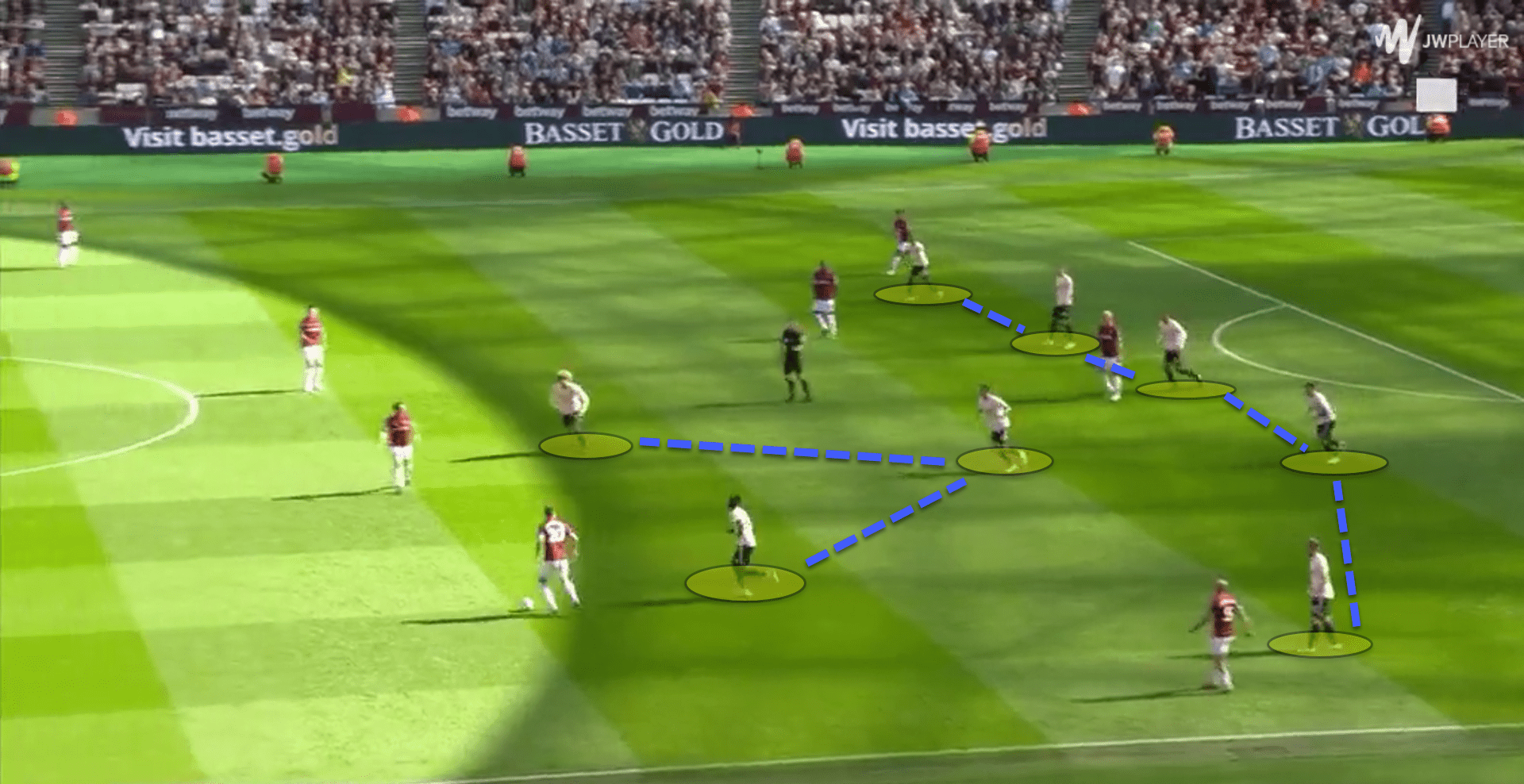

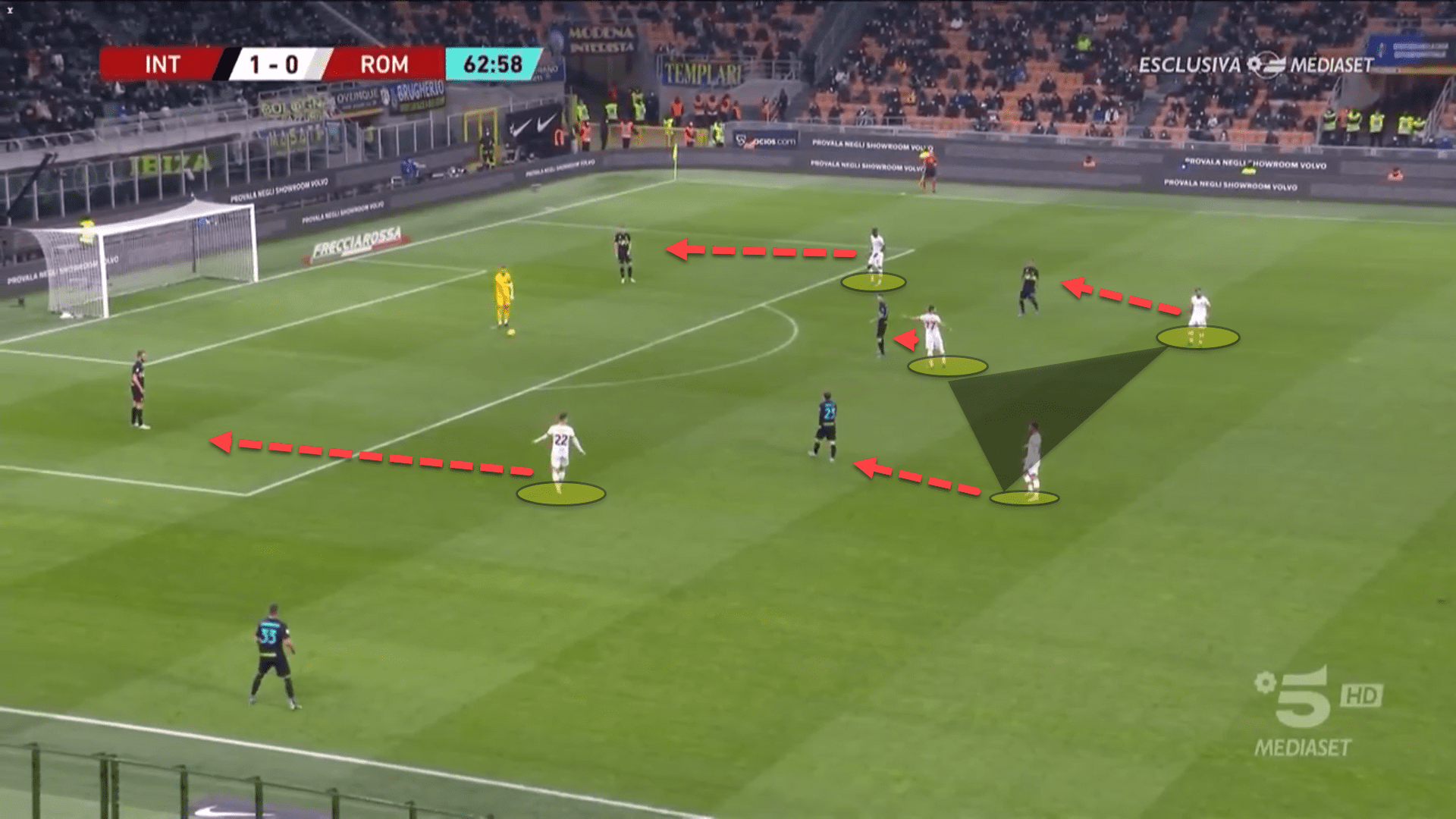

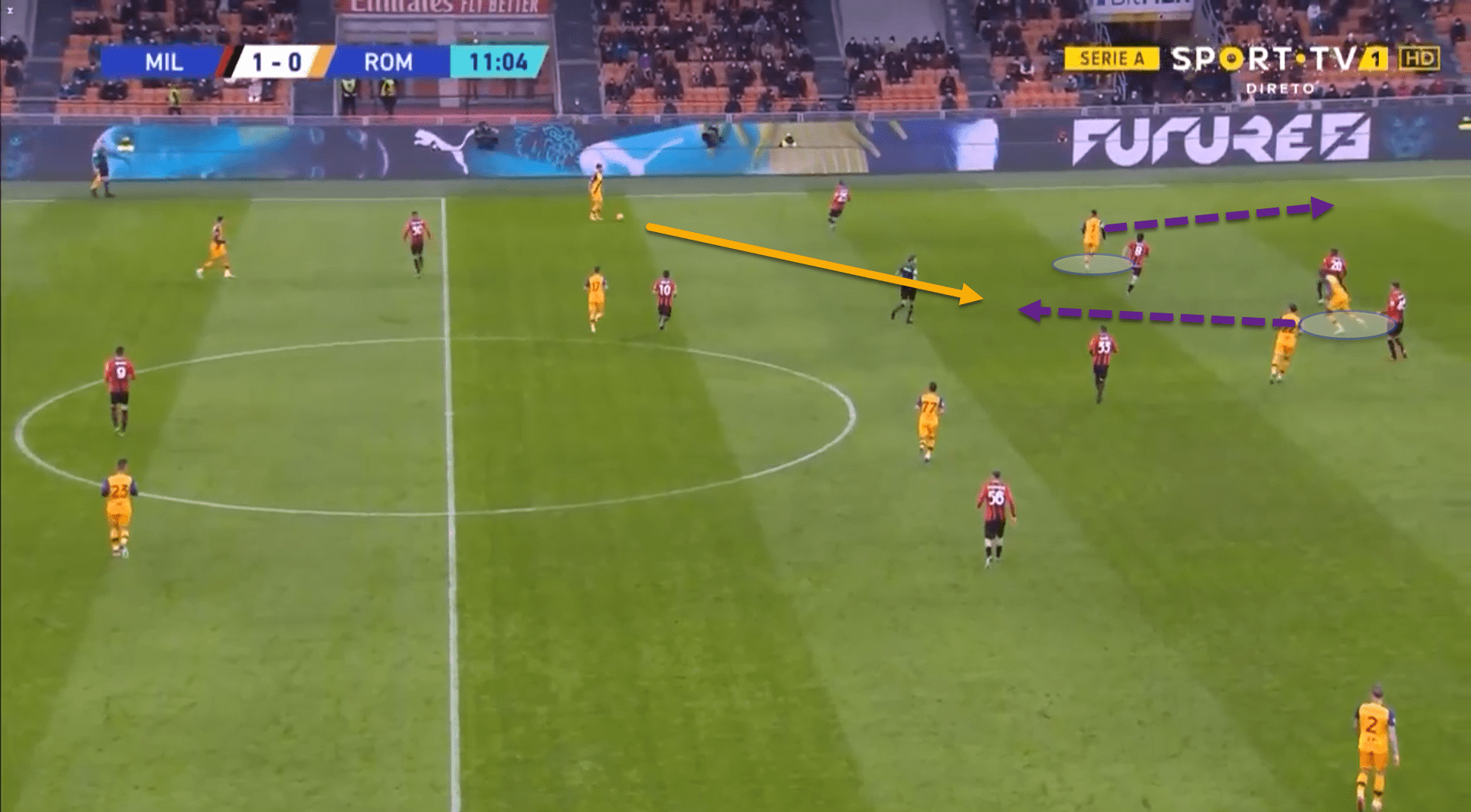

Here is an example of Roma’s dogged man-oriented pressing system composed by Mourinho. I Giallorossi’s pressing shape generally looks like a 5-3-2 or a 3-5-2 depending on how high up the pitch the wingbacks move to apply pressure.

As there is little to no width from the midfield or forward line in a 3-5-2, the wingbacks are tasked with pressing their opposite numbers in the high block phase, as displayed in the previous image. This involves quite a lot of hard work up and down the flanks from Mourinho’s wingbacks.

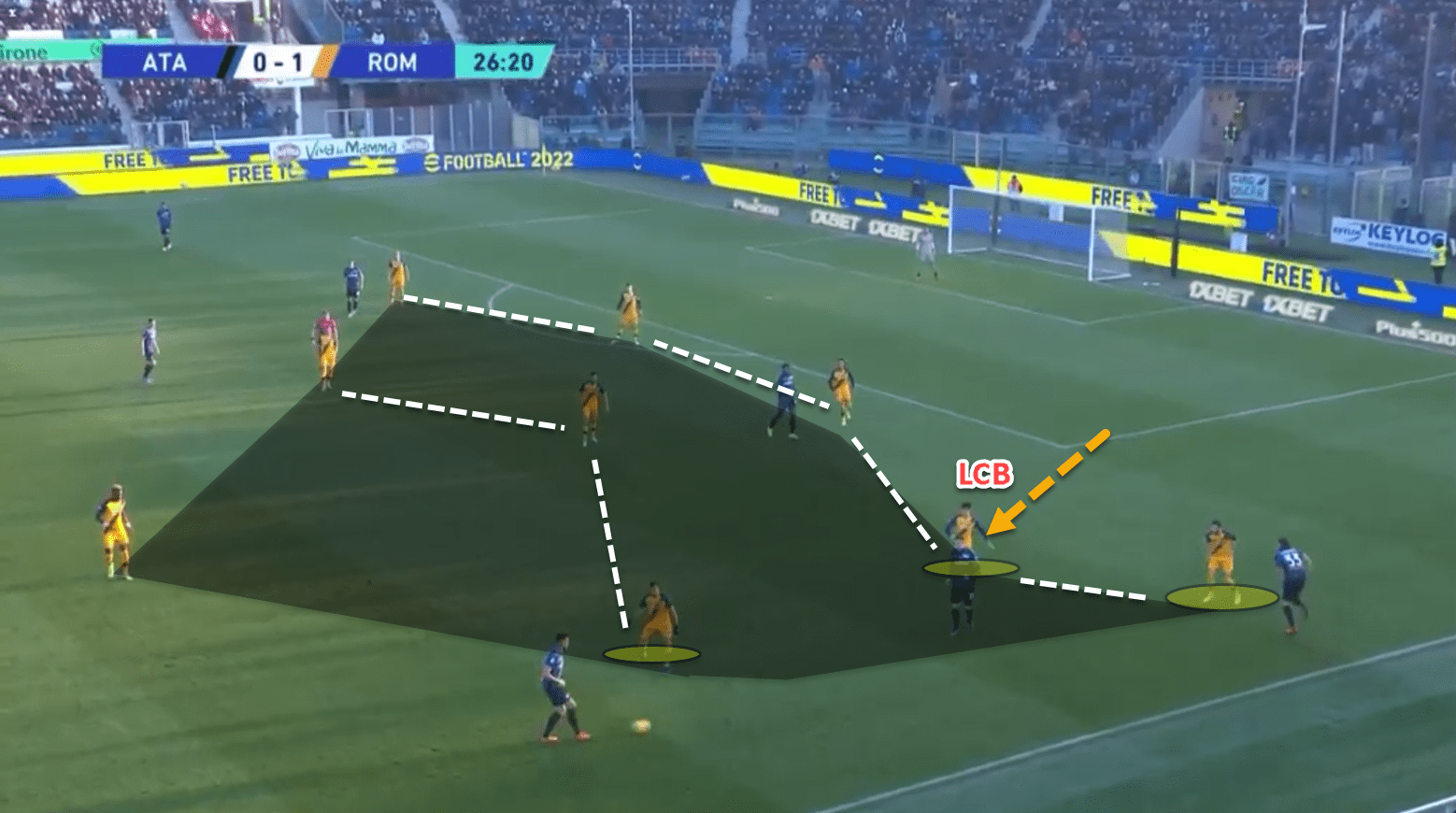

His centre-backs are also extremely important during this phase. While being the last line of defence, trying to ensure that everyone steps up to press together in unison, the centre-backs must also be quite aggressive in defending the space in front of the backline.

As Roma’s man-marking pressing style is strict, it can cause their midfielders to be dragged into deep areas of the pitch by the opposition, leaving a vast quantity of space between themselves and the three centre-backs.

The three central defenders must be ready to close down this gulf of space if the team in possession try to go direct and play over Roma’s press.

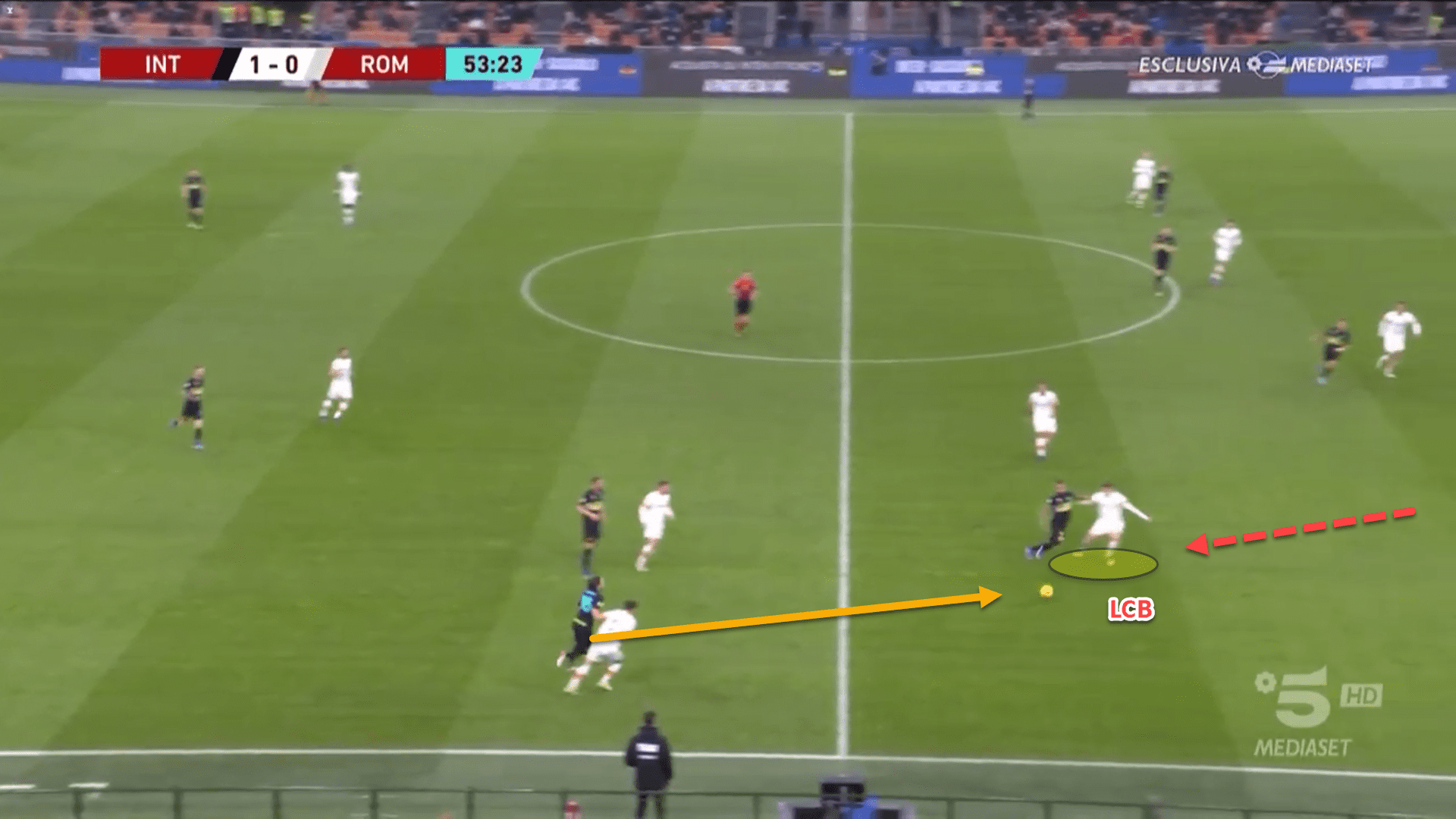

In this scenario, the ball has been played into the space behind Roma’s midfield line but the left centre-back has quickly stepped off his line to close down the receiver and regain possession for the Romans.

Mourinho’s teams are quite stereotypically known for their mid-to-low block defending and being rather passive in the defensive phases. However, in Roma’s 3-5-2 high block, I Giallorossi are very aggressive and coordinated, and there is a clear intent to win the ball back as early as possible, hence the pugnacious backline pressure.

Medium-to-low block defending

Now, let’s move on to how Roma defend in their 3-5-2 defensive shape in a medium-to-low level defensive block. This is the defensive phase that Mourinho has mastered throughout his career.

Think of Inter’s wall against Barcelona in the second leg of the UEFA Champions League semi-final in 2010 or the bus which was parked at Anfield when Chelsea put Liverpool’s title hopes to bed with a 2-0 victory in 2014; Mourinho knows how to structure a defensive block.

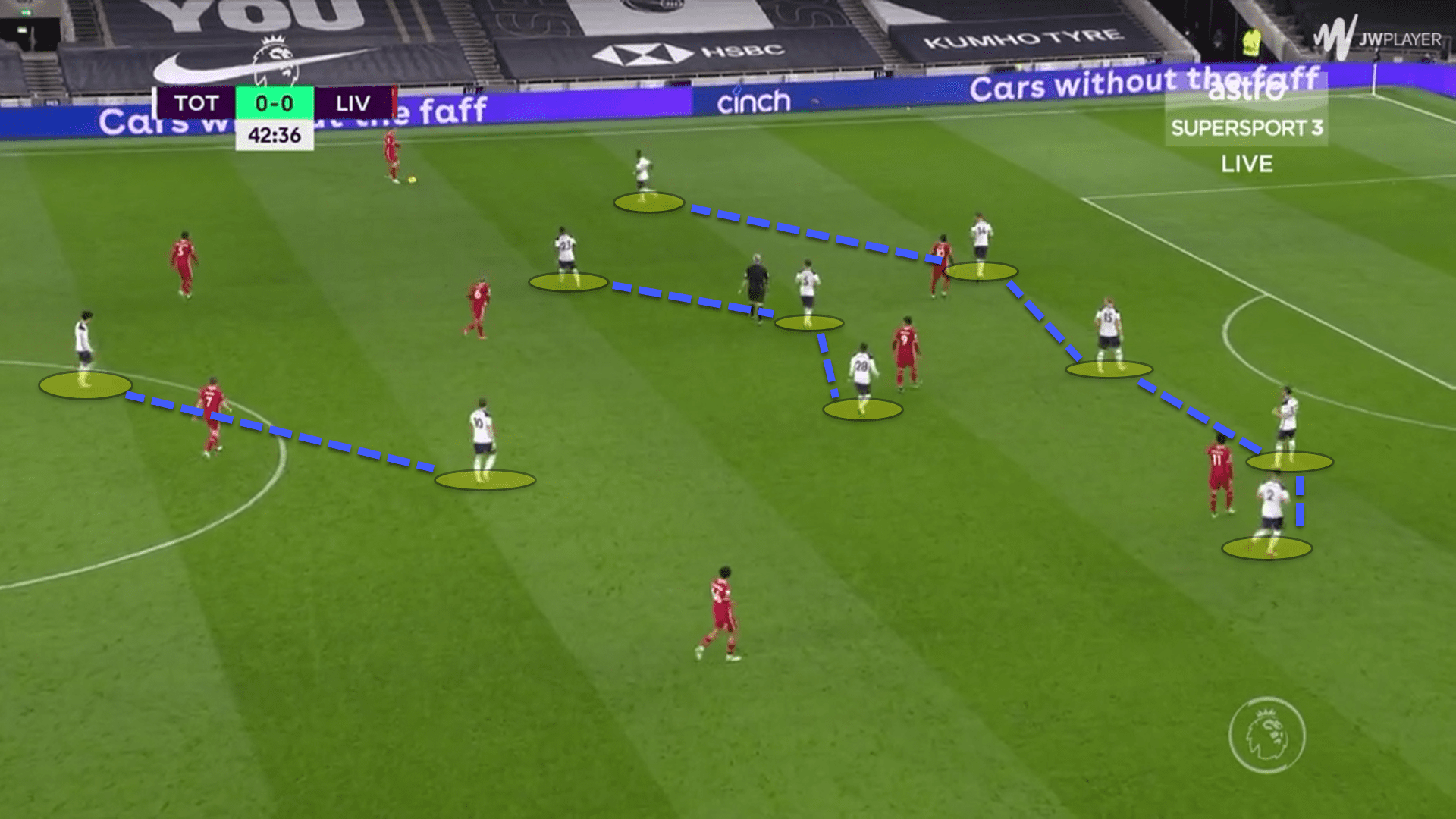

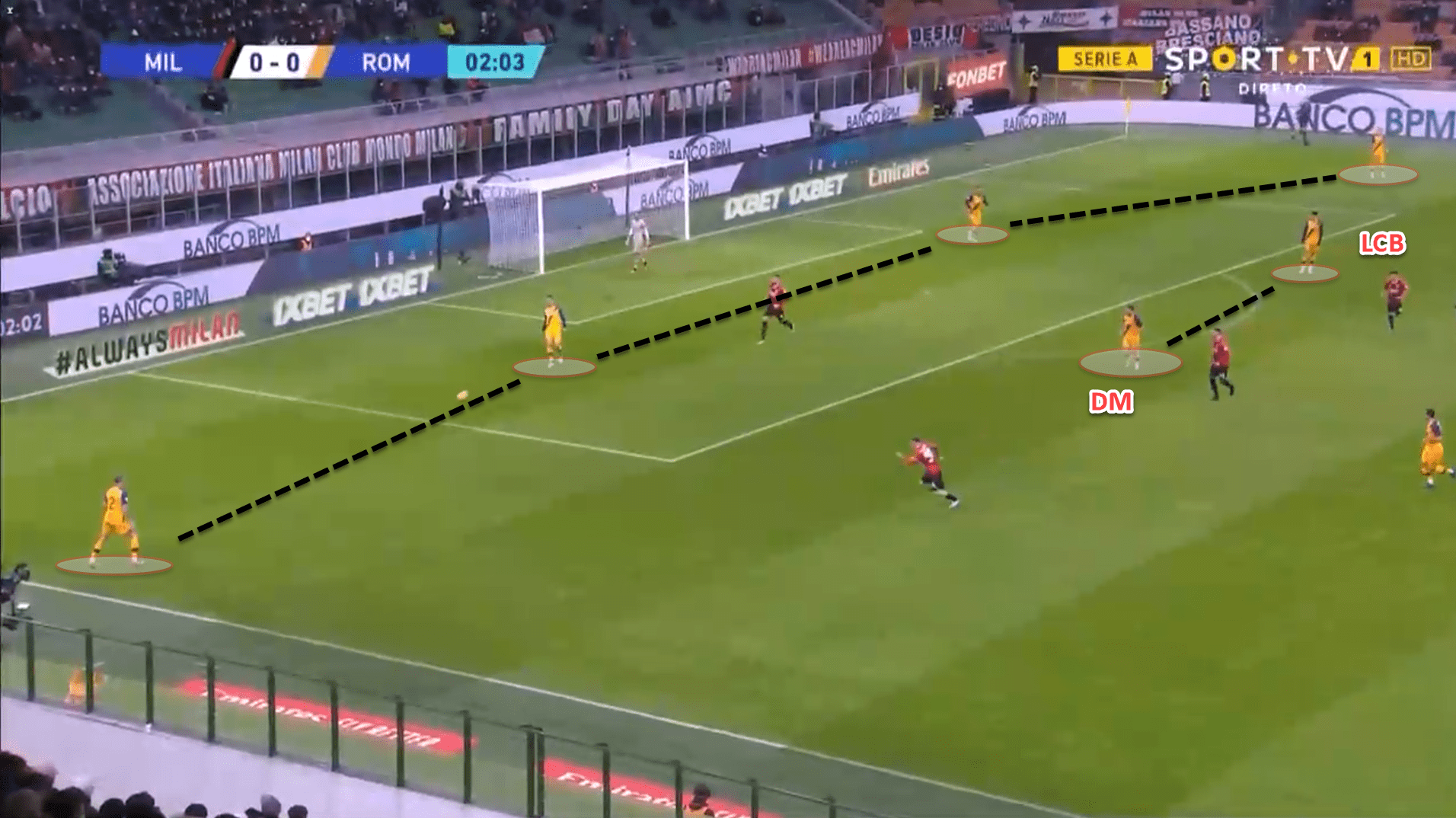

When Roma are sitting deeper on the field of play, their wingbacks drop back alongside the centre-backs and the shape falls into a compact, yet narrow 5-3-2.

The principles in Roma’s mid-to-low block under Mourinho are simple; deny space centrally, force the opposition wide, and win the ball on the flanks.

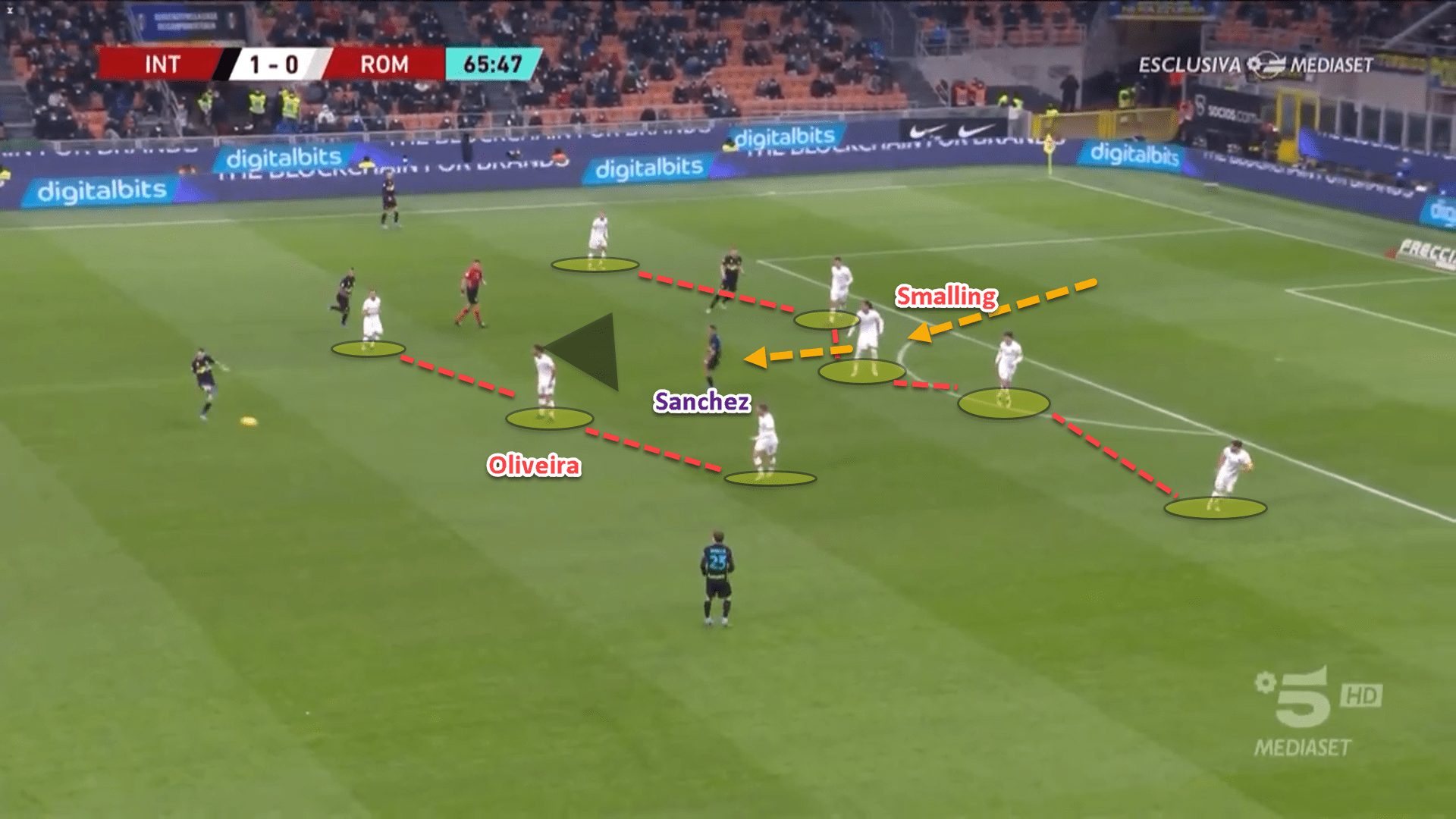

To deny the opponent space centrally, the players work together to ensure that the area between the lines is very compact. This entails cutting off any passing lanes, as well as marking any players who are looking to receive in the central corridors.

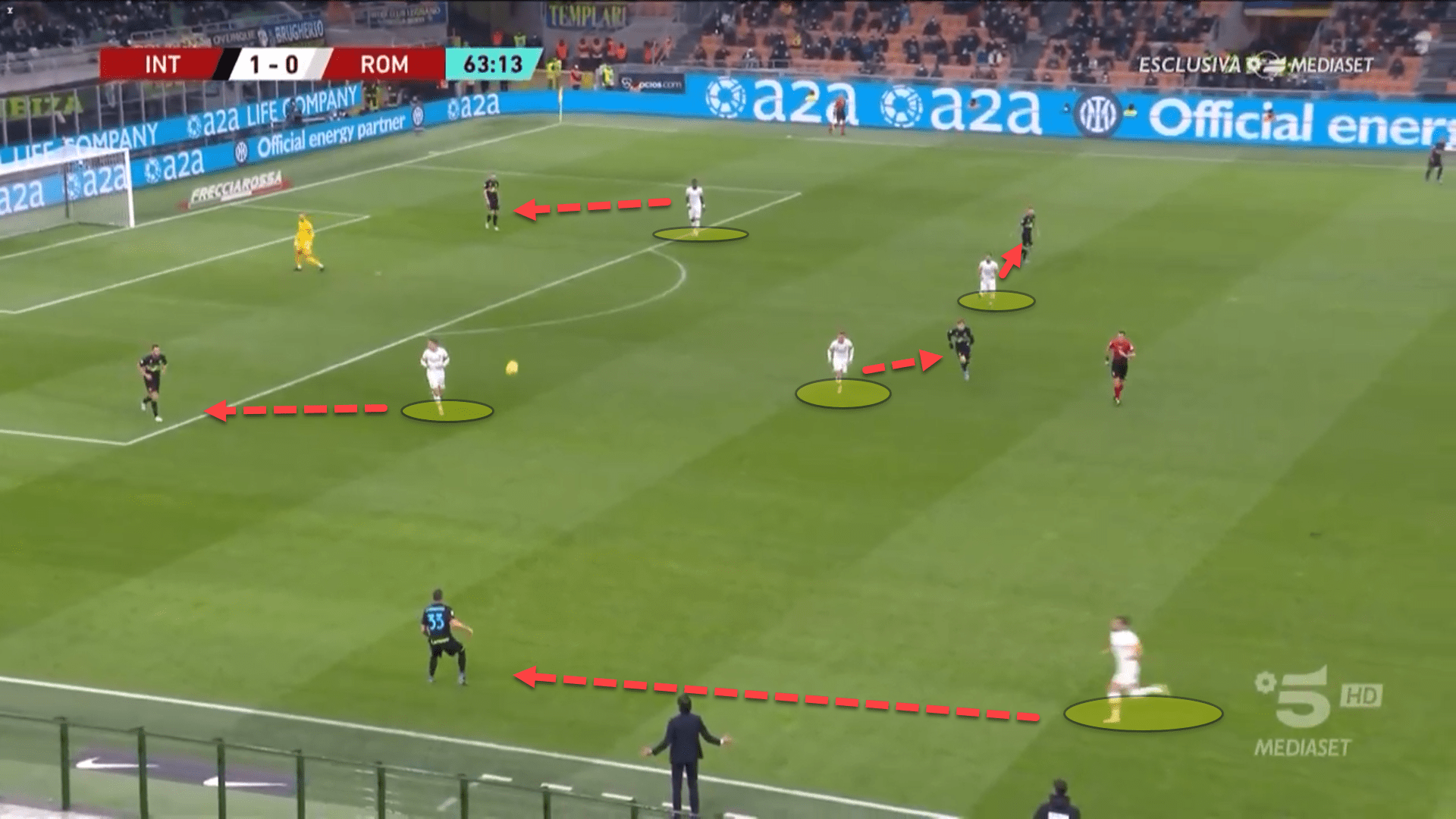

If the ball manages to break through Roma’s midfield line into the forbidden space in front of the backline, the centre-backs must be aggressive once more and close down the ball-receiver in order to prevent him from turning and driving goalward.

This image perfectly resembles Roma’s defensive set-up under José Mourinho. Inter are trying to play to the player positioned between the lines but the passing lane is being blocked off by the defensive midfielder, Sergio Oliveira. In case Oliveira’s cover shadow fails and the ball is played to the attacker, Chris Smalling — Roma’s central centre-back — is ready to push up and press him from behind.

Ultimately, the passing option was too risky and was essentially double-bolted. The player in possession was forced wide which is where Roma want them to play.

From this area, they can create a wide pressing trap to recover the ball and potentially hit the opponent on the break with precision and power.

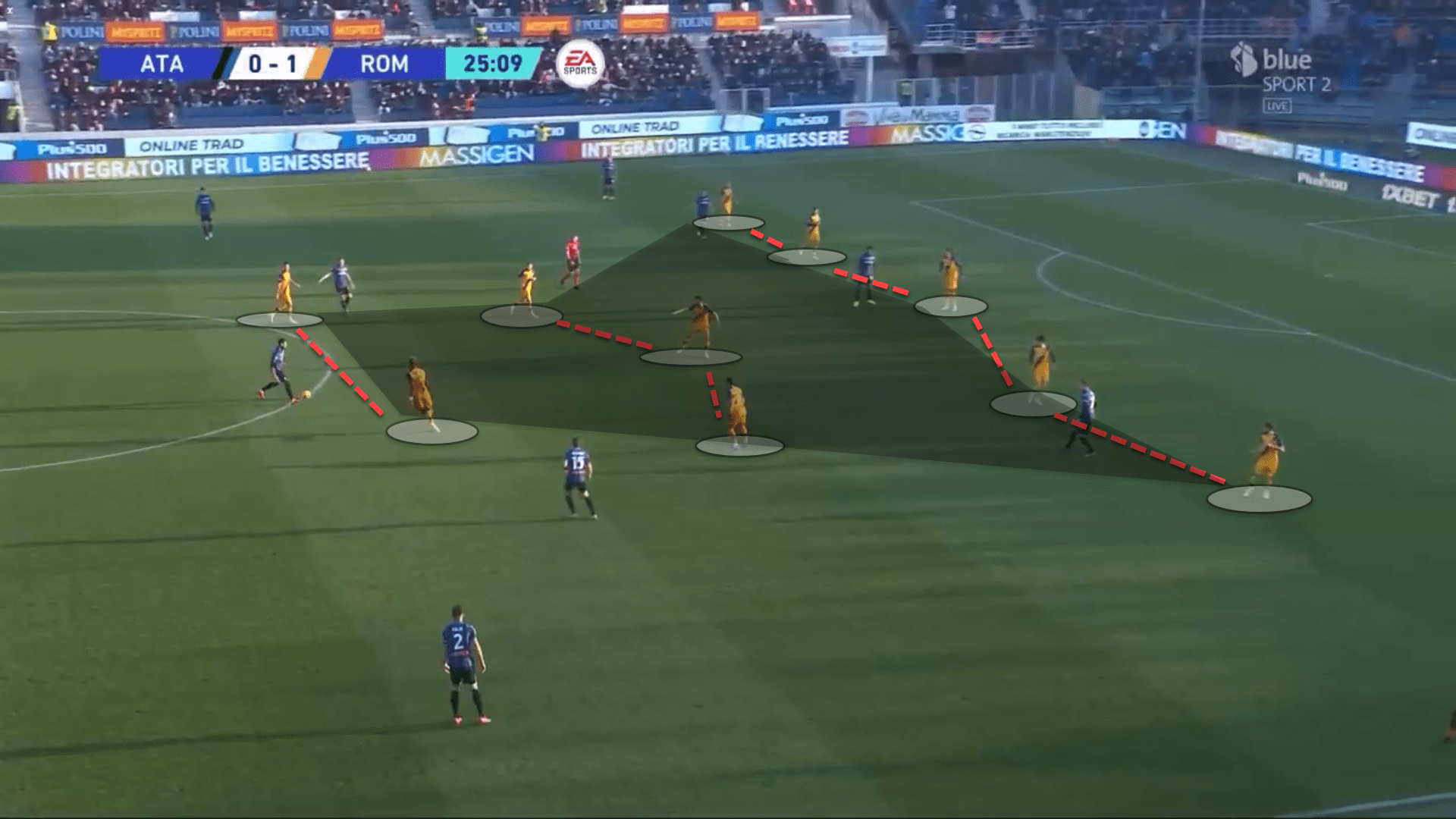

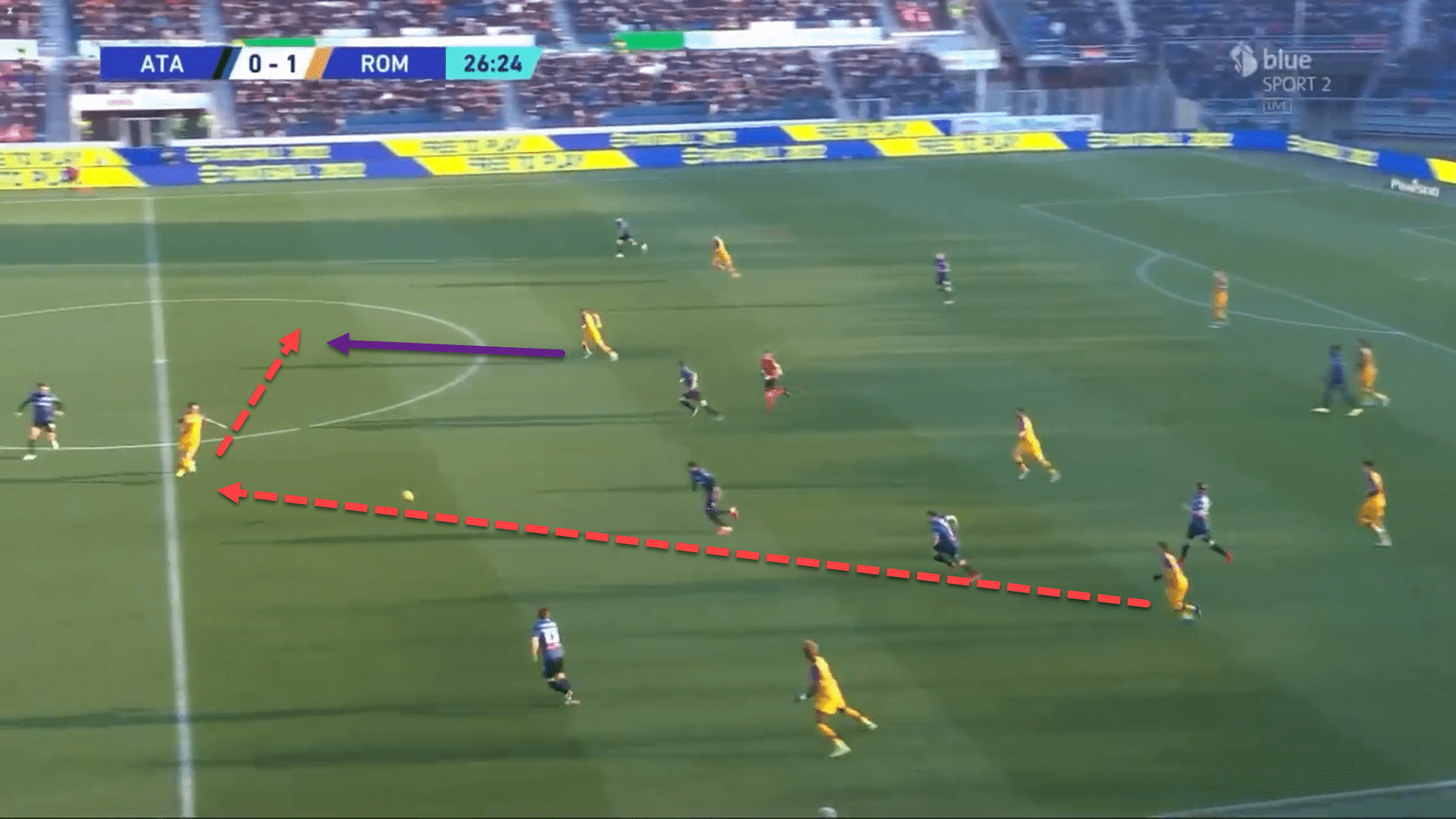

Here, Roma have directed Atalanta out wide and coerced them into a pressing trap. The left centre-back is aggressive in this trap and manages to win the ball, coming from behind the Atalanta attacker.

I Giallorossi quickly counterattack up the pitch using a direct ball to the frontline to hold up the play and link supporting runners. This rapid transition ends in Roma’s second goal of the game, and ultimately the match-winner in a 4-1 victory.

This excellent medium-to-low block defending is typically Mourinho. It is no shock to anyone that the Portuguese coach loves his side to sit deep and absorb pressure before taking advantage of the space behind the opposition’s high backline.

Central negation, wide pressing traps, aggressive centre-backs, and rapid attacking transitions are all a part of the side’s defensive play in their newfound 3-5-2 formation under the legendary manager.

Build-up and attacking play

Not predominantly known for giving license to his backline and goalkeeper to play out from the back, Mourinho has adapted slightly in the recent stages of his career. While the 59-year-old maintains a preference for his defenders to go long, Roma do pass it out from deeper areas too.

In the team’s 3-5-2, their build-up shape has been interesting, to say the least. When a team plays with three centre-backs, it’s pretty commonplace for one of the wide central defenders to push wide as an auxiliary fullback, creating a back four, while the wingback on that side pushes up high.

Mourinho doesn’t adhere to these rules. When has he ever gone with the grain? Instead, one of the centre-backs pushes up into the midfield behind the opposition’s first line of pressure while the wingbacks drop quite low. The shape resembles a 4-2-2-2 during this phase.

From this phase of play, there is a clear intent from Roma to invite the opponent to press them in deeper areas, hence why the wingbacks position themselves so low on the pitch. From here, Mourinho wants his side to go direct and to try and play over the defending team’s high pressure.

Having a very physical centre-forward to play directly to has always been a prominent feature of any José Mourinho side dating back to Didier Drogba at Chelsea or perhaps even Benni McCarthy at FC Porto at a stretch. Tammy Abraham, although arguably more mobile, is providing this for Mourinho now.

Abraham is a wonderful frontman and can provide aerial prowess, short link-up play, as well as runs in behind. An all-around handful for any centre-back.

The England international is quite often the centre of any attacks that Roma have, acting as the team’s focal point. During the attacking phases, Mourinho has coached his forwards to make a lot of countermovements in order to break down a defensive block and Abraham is key to this as well.

A countermovement is essentially when one player drops short to receive while the other runs in behind.

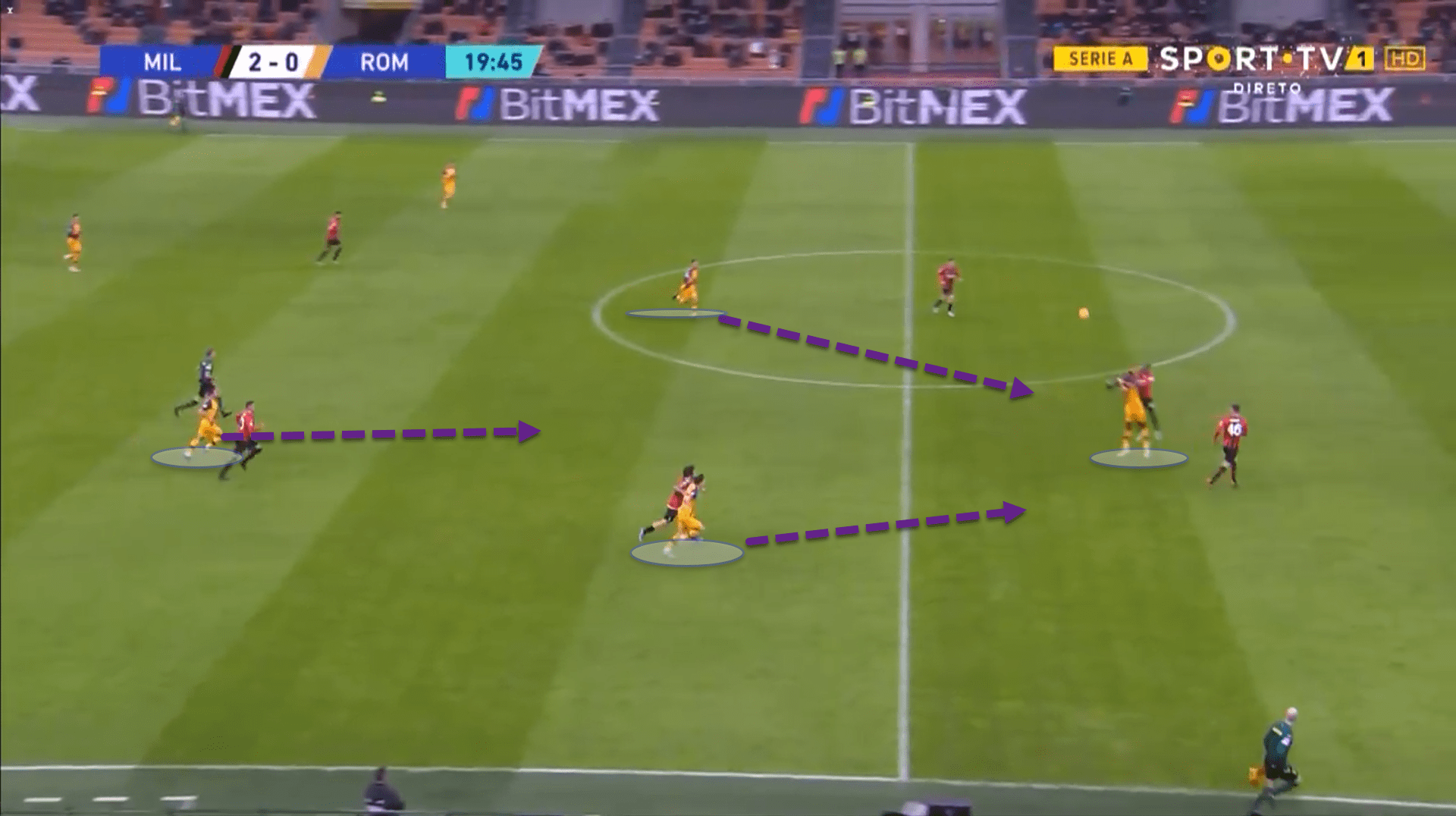

The wide central midfielders, or the number ‘8’s in the 3-5-2, are extremely important when Roma are using countermovements in an attempt to break through their opponent’s defensive block.

This is because they are tasked with positioning themselves in the halfspaces and making runs in behind the backline when the opponent’s wingback/fullback is dragged out, which can be seen in the previous image. Milan’s right-back is pushing across to close down the ball-carrier while the ball-near centre-back is dragged out by Abraham’s movement.

In turn, Jordan Veretout attacks the space behind, giving Roma an option to play around the defending team’s block.

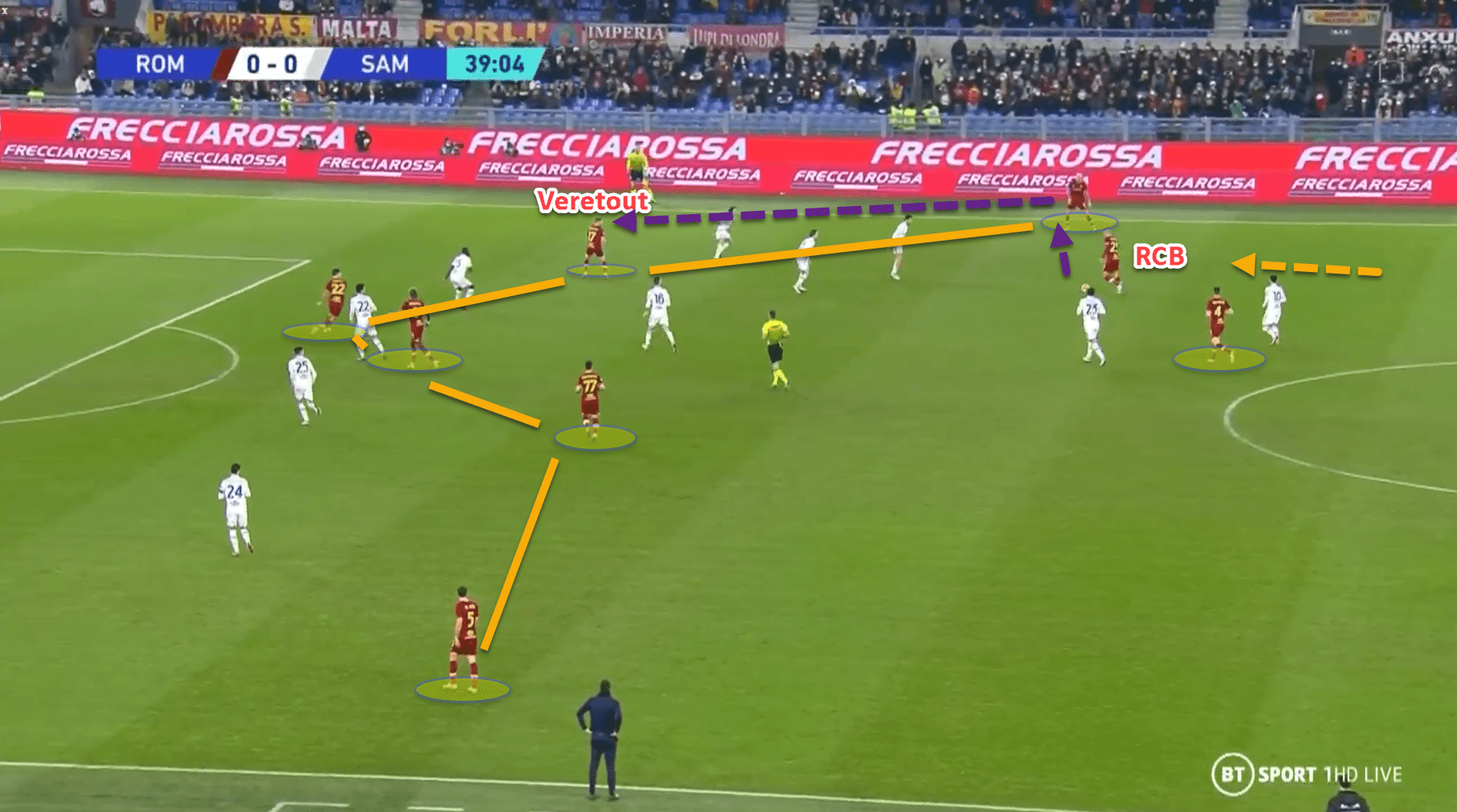

Veretout and Henrikh Mkhitaryan are very adept at fulfilling these tactical instructions from Mourinho, thus have mainly started as the ‘8’s in the 3-5-2. Often, Roma’s shape in a positional attack looks like a 3-1-6, resemblant to that of Ole Gunnar Solskjaer’s Manchester United in the 2020/21 campaign.

Look at this image for instance. Roma have structured themselves in a rather flexible 3-1-6. Veretout is positioned high in the right halfspace, anticipating that the right wingback will receive the ball, dragging Sampdoria’s fullback across which will give him room to receive in behind their backline.

The 3-5-2, with two rather attacking central midfielders, is a wonderful way for Mourinho to ensure that Roma are much more offensive than any of his previous sides.

Conclusion

Roma’s squad certainly aren’t world-beaters. Undoubtedly, trying to bring Roma back to their glory days is going to be arguably the toughest challenge of his career so far. However, the dogmatic Portuguese coach has proven himself to be more adaptable than ever before since his appointment to the dugout at the Stadio Olimpico.

One could even make the point that Roma are the team that have played the most expansive football under Mourinho since his days at the Santiago Bernabeu. In fact, I Giallorossi have accumulated the sixth-highest total expected goals in Europe’s top five leagues this season so far with an xG of 45.69.

Mourinho is proving himself to be adaptable, something which he has been heavily criticised for not being throughout the past six years and perhaps is beginning an entirely new chapter in his long managerial career.

Comments