Last season, Julian Nagelsmann and Bayern were able to retain the Bundesliga title by a huge margin, but their performance in the UEFA Champions League left a lot to be desired as they were knocked out by Villarreal in the quarter-final. This summer, there were big changes within the team as they welcomed the arrival of new players such as Ryan Gravenberch, Sadio Mané, Matthijs de Ligt and Noussair Mazaroui, but their goalscoring machine, Robert Lewandowski, departed for Barcelona.

Nagelsmann saw this as an opportunity to transform his side again. In a recent interview, he said less emphasis would be put on tactics and match preparations on the opponents because he realized it is vitally important to trust individual characters at Bayern. Meanwhile, on the pitch, Bayern also look different compared to the rather strict structure applied in 2021/22. This tactical analysis will discuss how Nagelsmann has created an environment for his players to thrive in possession.

More flexibility is added

Previously, as Nagelsmann himself also spoke about publicly, he was a big fan of the 3-2-5. Regardless of the formations submitted on paper, his sides have always shown some constant feature when it comes to the offensive organization.

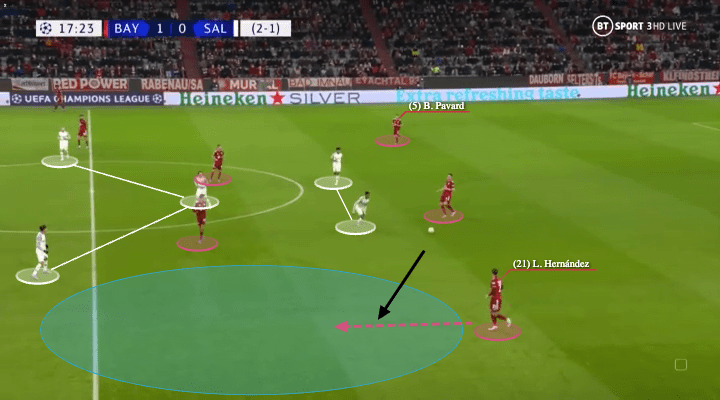

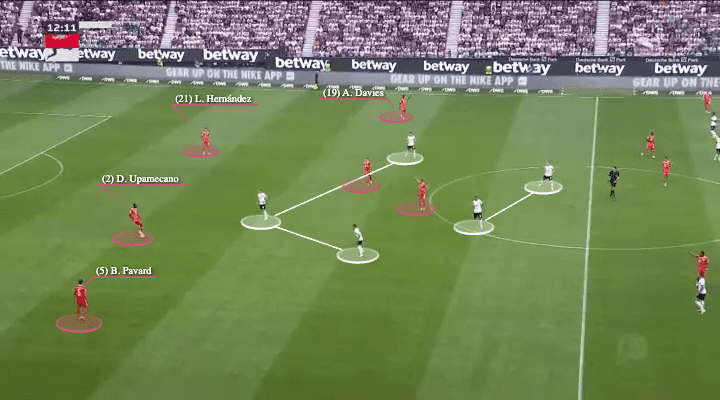

Firstly, Bayern played with a back three created by asymmetrical full-backs. Since Benjamin Pavard is always treated as a deep player and almost a wide centre-back in the construction, Bayern wanted to use the extra man in the first line to bring the ball forward in the outside space. For example, we saw the 3-2 of Bayern in the image vs RB Salzburg, they always put the first pass to the outside centre-back in space and want him to carry into space as Lucas Hernández did here.

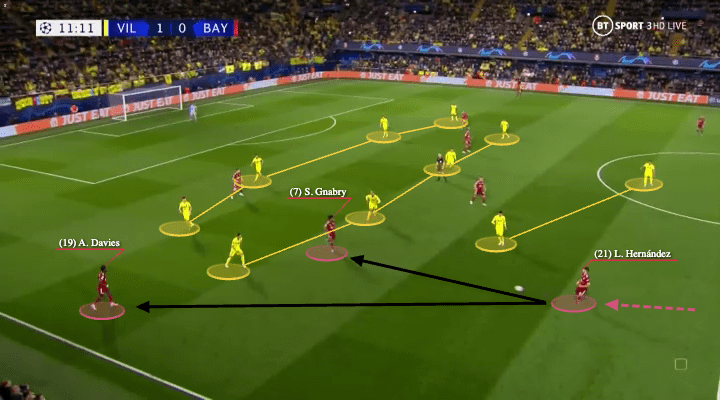

When it comes to advanced areas and the responsibilities of full-backs, Alphonso Davies has clearly been given an offensive role while always pushing high and wide to provide the width. Naglesmann would have wanted the young Canadian international injecting outside threat to free the winger in space — in our example vs Villarreal, this was Serge Gnabry, while in other cases we can remember Leroy Sané being given a freer role in space because of this idea.

Another feature in Bayern’s offensive construction previously was wide centre-back Hernandez, as we’ve already pointed out, was tasked with carrying the ball forward in the initial stage of the sequence.

Positionally, Davies and the winger shall be quite disciplined to maintain the structure and it might restrict the individual freedom at times. Now Nagelsmann wanted to jump away from these ideas and believe more in individual abilities to solve problems in the attack. That 3-2-5 was no longer being kept by all means as we also saw Bayern attacking in other ways.

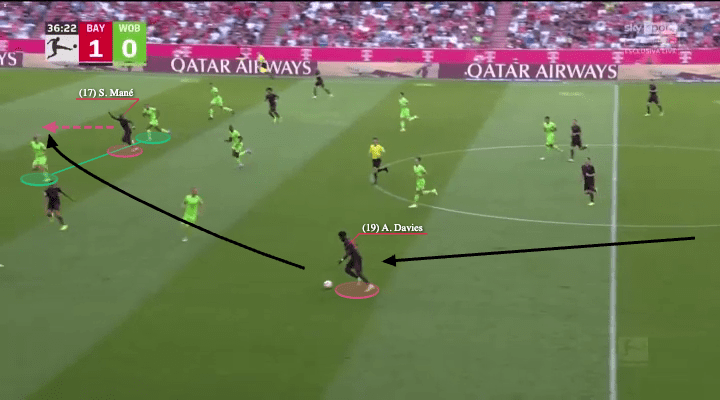

An obvious change was Davies’ position, he was not required to strictly hold the width on the touchline as he did last season. Instead, the 21-year-old player was permitted to play lower and sometimes more centrally, so Bayern did not rely on the wide centre-backs’ ball carrying to advance plays — passing can provide solutions.

In this example vs Wolfsburg, Davies received in the half-space from the defender, a position he rarely appeared in last season. Then, he already tried to play the ball to Mané who was ready to run behind.

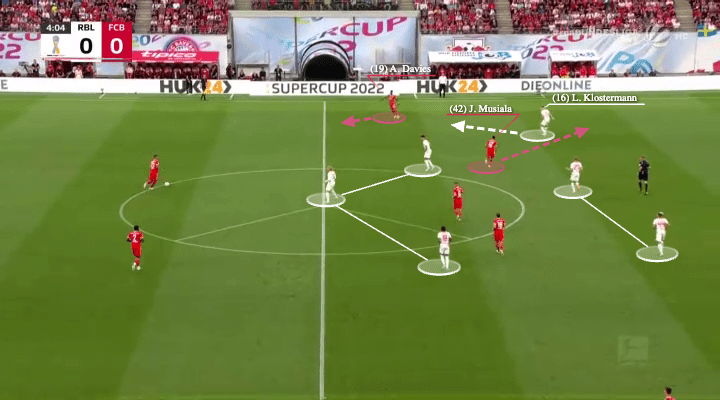

As early as the game in the DFL-Supercup, Bayern tried the new shape to counter RB Leipzig’s 5-2-3 defensive structure. Davies played noticeably deeper in the construction phase and Pavard did not always stay so deep to form that three at the back. Instead, only two centre-backs remained central.

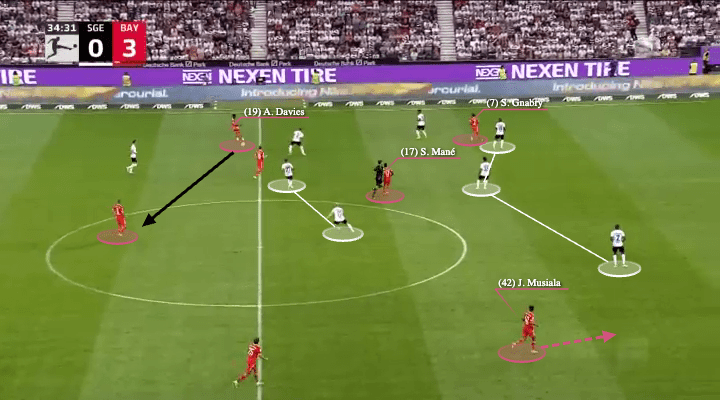

Bayern were more like a 4-2-2-2 with the ball, as their wingers would be given the freedom to roam in the centre — a role we could describe as “half-winger” or 10. In the image above, Davies was going to support Hernandez in deep and pulled Lukas Klostermann out, which vacated spaces behind the right wing-back for Jamal Musiala to exploit.

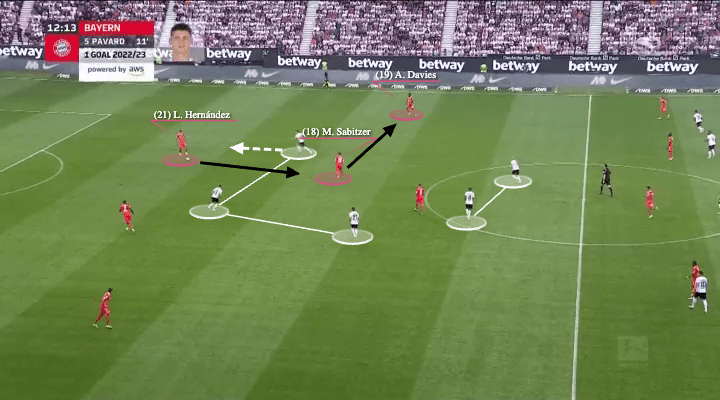

We see another example of Bayern’s offensive structure in this example versus Eintracht Frankfurt. On occasion, Pavard would still position himself deeper in the construction, but how Bayern used this shape was different as Davies did not go so high to the winger position. Instead, he was deep to maintain a closer connection with the ball and players around, alongside a pair of 6s sitting in the centre.

As Dayot Upamecano moved the ball to his partner, we saw Bayern using a passing sequence to beat the press as they used Marcel Sabitzer as a transit point to reach Davies deep, as we have shown in the analysis in this image.

If it was last season, Davies would probably have pushed higher to see if he could draw the Frankfurt winger down, to create space for Hernández to carry forward. But now, Bayern are more comfortable drawing the opposition out and beating them with passes as we have shown in this example.

Verticality in ball progression

After analysing the structure and shapes above, another important aspect is how Bayern actually progressed the ball. We hinted they were different from last season as the wide centre-backs were no longer required to carry the ball over huge distances, as passing is also a favourable option, but it is not about playing the ball laterally and backwards 100 times. Instead, it’s required to pass vertically to reach the opposition goal quickly.

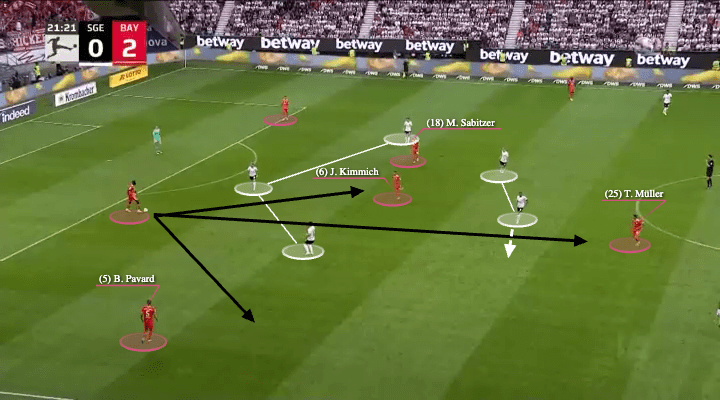

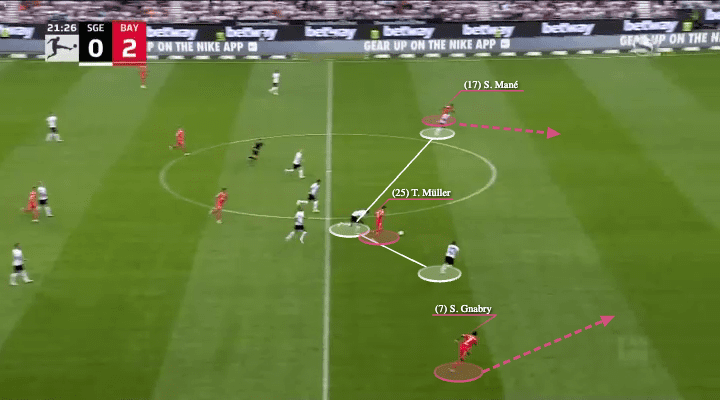

In Bayern’s midfield, they often play with two 6s, and an additional player showing up behind the second line. That player could be the half-winger like Musiala, false-9 such as Mané, or the Raumdeuter, Thomas Müller. Nagelsmann wanted to give Müller some freedom to roam so as not to restrict his natural sense of finding spaces unimaginably.

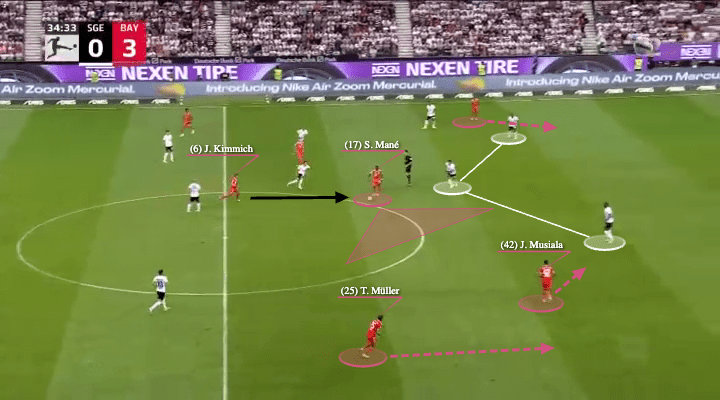

So this structure would also create favourable conditions for the defenders to find passing options. With Pavard deep, they stretched the three-man Frankfurt first line. Now the half-space and central corridor were opened for Upamecano to play the forward pass.

Müller’s presence behind the Frankfurt midfielders became a worry as we saw Djibril Sow moving outward to try closing that vertical channel. But that defensive intention was read by Upamecano, who counter-acted and sliced the ball to Kimmich, who had enough room to turn.

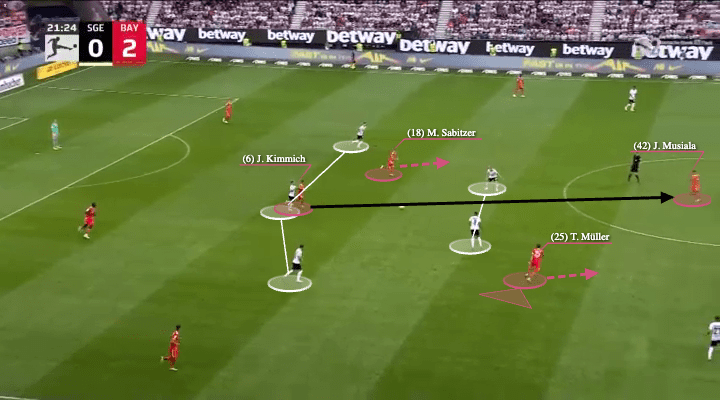

Kimmich is a quick thinker and mature player, and he was helped as Musiala the left-winger sat behind the second line as an option. Given that Bayern are focusing more on verticality to get the best out of the talented players at their disposal, they always prioritise this ball into whatever attacker is in space. Because of Musiala’s great ability to turn in pockets of space, Bayern found themselves effectively going forward when the ball arrived at the young German’s feet in the second phase.

In this case, Musiala didn’t get the turn but Bayern were so competent in combinations. The image shows both Sabitzer and Müller already turned and facing forward as long as the ball was travelling to Musiala’s feet, so there were two third-man options for the lay-off.

Dropping players into midfield does not dismantle the offensive structure, because Bayern’s attackers still maintain a level of discipline with two players in high positions to push the last line, but they were not fixed names as Nagelsmann allowed them to see each other and decide based on their interpretations of the game. Compared to Lewandowski as a relatively fixed point and a conventional striker, now Bayern enjoy higher fluidity and could pose more sets of questions to the defence.

In this case, it was Mané and Gnabry playing as the highest players on the pitch, and because they were already in a position to attack depth, instant passing options behind the line were generated for Müller, who was used by Musiala as the third-man. Now, Bayern have drawn the opposition high and unlocked the block with plenty of space to run into.

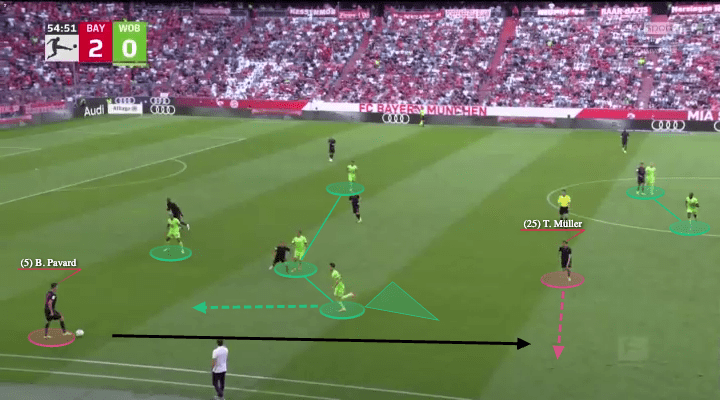

We have another example of Davies’ deeper position and link-up with teammates here, as he found Kimmich with a lateral pass in this image.

You could see Bayern transforming into another shape as Gnabry and Musiala were the highest players in this situation, while Mané dropped a bit to play in that space behind the opposition midfield — the same concept we have explained.

Mané was facing Davies’ side in the initial pass, but as we captured his body orientation in the next image, he quickly got the turn when the ball arrived and now faced the other side. This is a good example to outline how Bayern’s attackers can dictate that space as they’re so good at orienting themselves for the next action.

The pass from Kimmich was vertical as Bayern do not want to spread the ball wide in the early stages — it’s always preferable if they can hit that pass into the centre and to the player in the hole.

As Mané got the turn which helped him to use his body to resist the centre-back’s pressure, he also noticed there were other two advanced options (Musiala and Müller) running forward, so the attack progressed into the final third quickly.

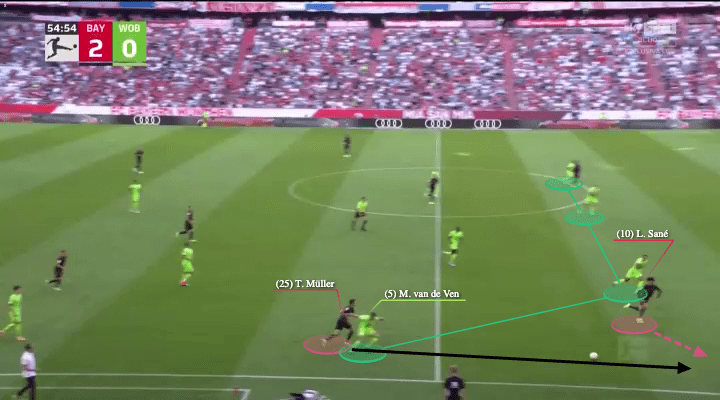

Although verticality is preferable in the centre, Bayern have also shown that they can play these type of passes in wider situations, with the use of a deep right-back. This example showed the Wolfsburg left-winger was attracted by Pavard, but usually, the opponent jumps from a diagonal angle, so it is perfectly fine if the pass goes forward vertically. And here came Müller, who read the left-winger’s press and counter-acted to receive behind the pressing line.

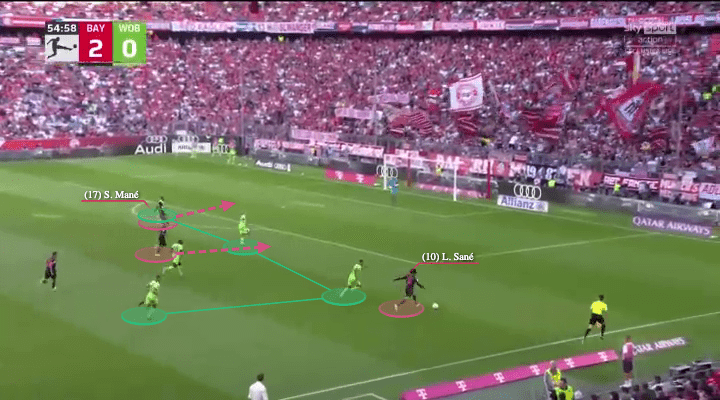

As Müller received suddenly, Wolfsburg were forced to react and their left-back jumped recklessly but was too late to close the angle and let Müller send the pass forward again. There are always runners looking to attack space in behind in Bayern’s system as we have explained; this time, they were Sané and Mané.

Then, it was about the attackers’ individual qualities to create their own angle. When the former Man City attacker was released down the side, he did not passively let the centre-back close him down. Instead, he took touches very quickly, adjusted the ball and his body to open up an angle to face the defender.

After that, Bayern arrived. As Sané dribbled, the others had to come and support in finishing positions, so Bayern kept a high-paced attack as soon as the last line was broken and didn’t have to spend extra time circulating, allowing the opposition to settle into an organised defensive block. Taking advantage of disorganisation and unpreparedness is key.

Conclusion

Nagelsmann said he had success through certain training philosophies and tactical behaviours to adapt to opponents, but Bayern’s players were not used to this. He believes that such a big club should not adapt to the opponents, so he deviated from these practices last season and gave us a Bayern with a whole new look.

Comments