In his inaugural match as the head coach of the German national team, Julian Nagelsmann led the squad to an impressive 3-1 victory against the USA.

This match showcased Nagelsmann’s vision for the team and the adaptability and potential of the German national side.

As one of the world’s most highly regarded young managers, Nagelsmann’s appointment brought high expectations for a national team seeking a resurgence after a few challenging years.

This Julian Nagelsmann tactical analysis will delve into the critical aspects of Julian Nagelsmann tactics and how they influenced the outcome against the USA.

This analysis, in the form of a team analysis, will shed light on the tactical nuances that marked the beginning of a new era for Germany.

Julian Nagelsmann Germany Lineup

Let’s begin by delving into the team’s tactical configuration, the fundamental structure, and the system Nagelsmann implemented within just a few training sessions.

The foundational formation resembled a 4-2-3-1 setup: Marc-Andre ter Stegen – Jonathan Tah, Mats Hummels, Antonio Rüdiger, Robin Gosens – Pascal Groß, Ilkay Gündogan, Jamal Musiala, Florian Wirtz – Leroy Sane, Niclas Füllkrug.

In the attacking phase, this lineup switched to a 3-2-5 formation.

In the frontline, Florian Wirtz played in a slightly tucked-in position, while Robin Gosens assumed the role of an advancing left-back.

Gosens provided the width that enabled Wirtz to position himself inside, effectively creating a box-like formation.

Jamal Musiala functioned as a shadow striker, while Leroy Sane took up a high and wide position, primarily due to Jonathan Tah typically operating slightly deeper on the right.

Build-Up Play

What immediately stood out was the vertical football style that Nagelsmann is renowned for.

He’s recognised for his offensive and vertically-oriented approach, especially in swiftly transitioning through the midfield.

In a positional play strategy, the build-up phase can be likened to the opening moves in a game of chess.

Its flexibility marked the build-up, involving variations like a back 2, back 3, or back 4.

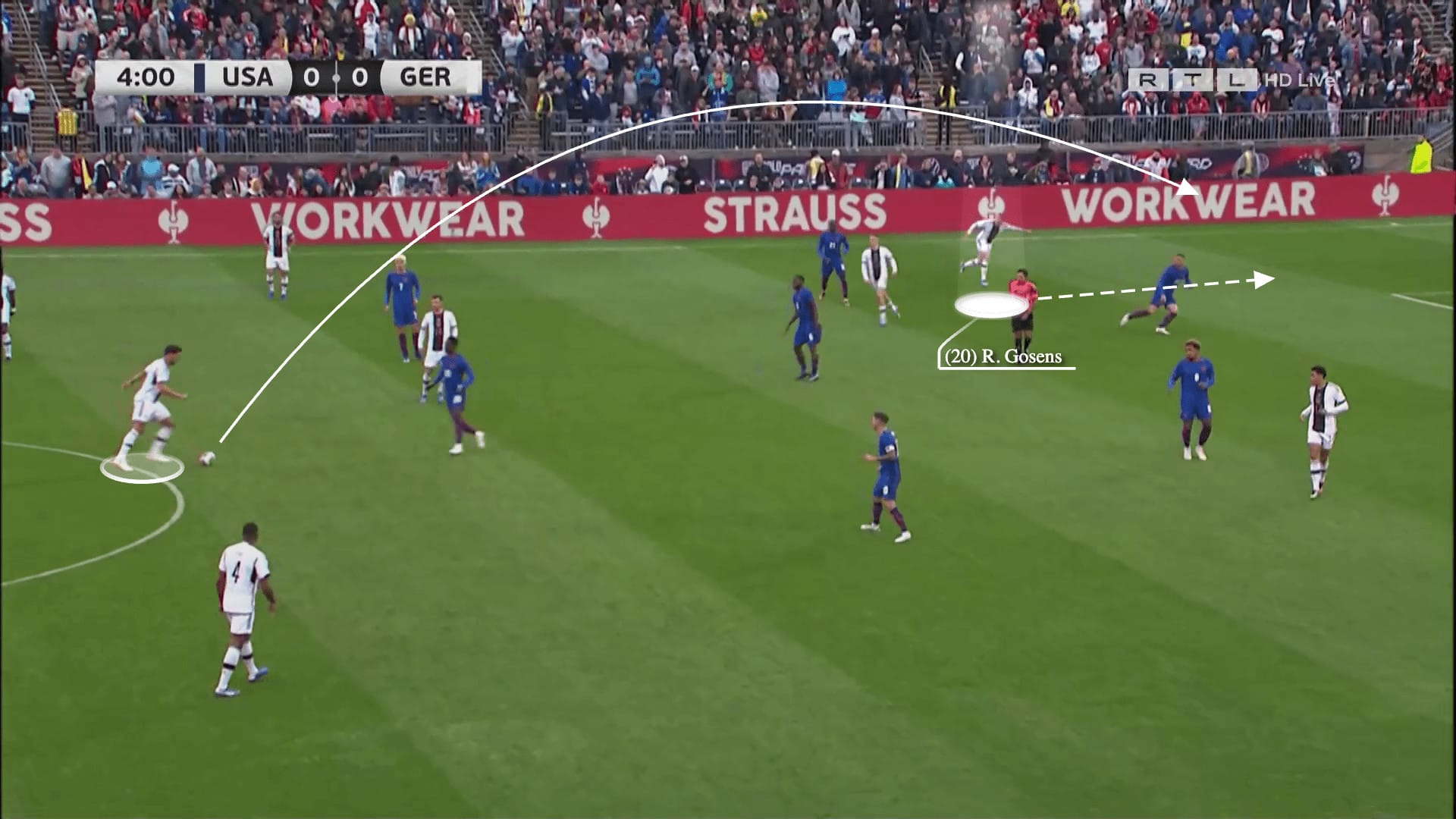

Regardless of the formation, certain elements remained consistent: Gosens played as a left wing-back (LWB), positioned wide and distanced from the centre-backs, avoiding tucking inside.

Gross occupied central positions, and Gündogan dropped deeper to provide support.

Tah’s role resembled that of a right centre-back or right-back, reminiscent of Nagelsmann’s approach with Pavard.

This configuration often created a lopsided structure, resembling a 3-2-4-1 or a 4-1-4-1.

The rapid transition through the midfield was a critical aspect for the German team.

Pascal Groß was included in the starting lineup instead of Joshua Kimmich.

He operated at a slightly higher position in the first half compared to the other defensive midfielder, Ilkay Gündogan.

This adjustment could potentially raise some issues, which we’ll discuss shortly.

Following the swift transition through the midfield, the players were tasked with combining in the final third, primarily involving Wirtz, Musiala, and Sane.

Musiala’s role was to deliver the final incisive pass.

The formation wasn’t particularly surprising, especially given the presence of a traditional centre forward in Niclas Füllkrug, who depends on the players around him to set up offensive actions.

Sane, operating as an isolated winger, and Pascal Groß, tasked with initiating counterattacks quickly, functioned effectively.

Also, the formation offers various attacking options.

Teams can play through the middle, exploit wide areas, or switch the play quickly to catch the opponent off guard.

This variety makes it harder for defenders to predict the attacking approach.

The setup often allows for a more fluid attacking structure, with forwards and midfielders interchanging positions.

This fluidity can create opportunities for deep runs from midfielders or forwards, making it harder for defenders to track runs and maintain a solid defensive shape.

Julian Nagelsmann adeptly utilised the available personnel.

He had the luxury of choosing between two attacking and offensively-minded left-backs in David Raum and Gosens.

However, in the right-back position, where Germany has limited options at the highest level, Nagelsmann deployed Tah, a versatile player who frequently shifted into a back three during offensive phases.

Tah also displayed a tendency to push forward relatively early during the build-up, creating space for the defensive midfielders, who were then seamlessly integrated into the team’s play.

The primary objective was to execute swift ball movement through the half-spaces and central passing lanes.

Nagelsmann’s approach clearly emphasised preventing play down the wings, aligning with his established tactical preferences.

Attacking phase

Although Germany had the lion’s share of possession at 60%, after scoring the opening goal, the USA opted for a more defensive approach by dropping deep to defend.

This defensive stance allowed Germany to circulate the ball from side to side, probing for openings in the American defence.

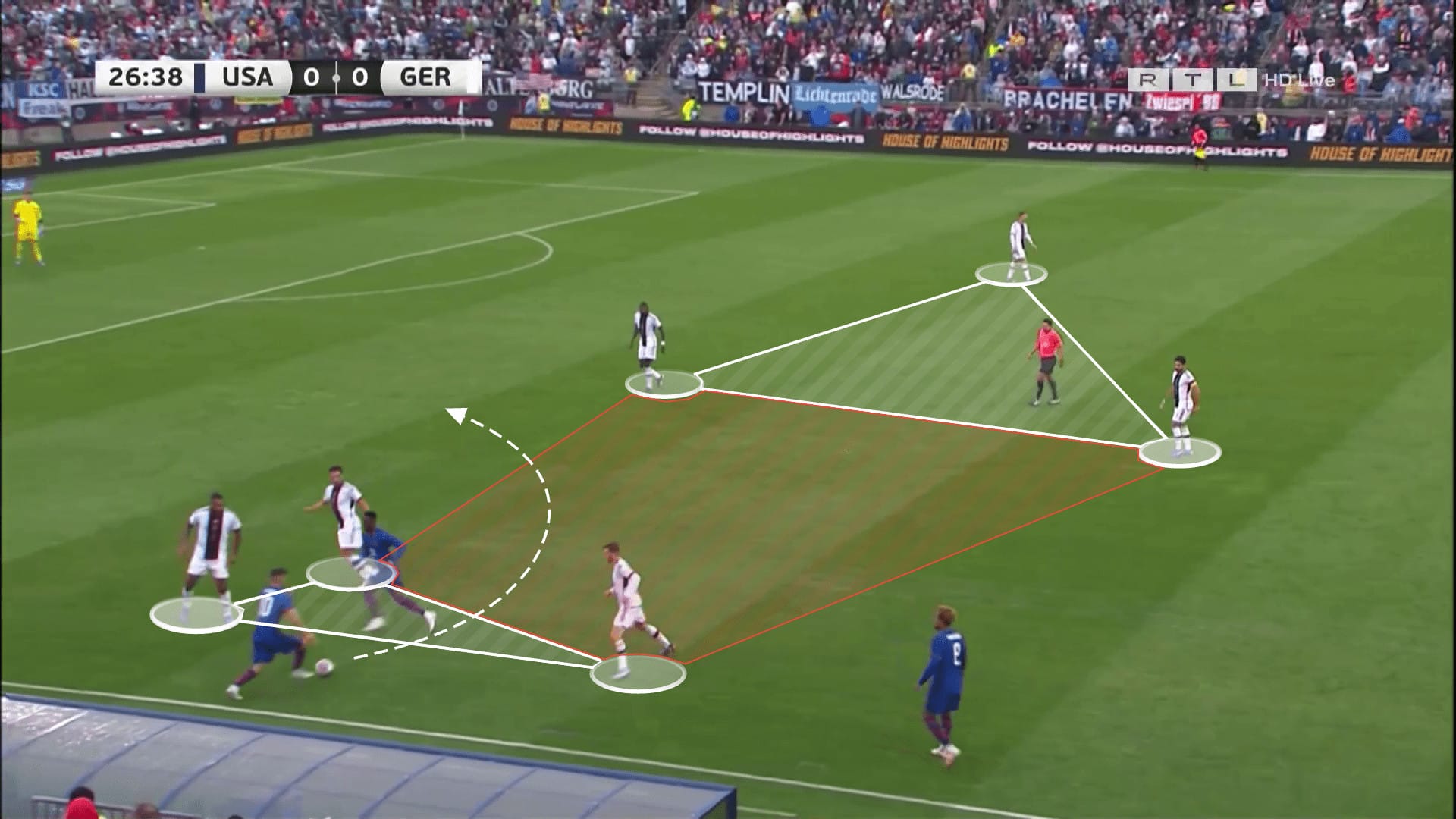

Similar to his tactics at Bayern Munich, Nagelsmann adopted a possession-based strategy, utilising formations like 2-3-5, 3-2-5, or even 3-1-6 to gain a numerical advantage over the USA’s compact defensive shape.

Notably, many coaches who emphasise positional play tend to employ a 2-3-5 or 3-2-5 formation during the attacking and possession phases.

Switching from a 4-2-3-1 formation to a 3-2-5 formation in attack offers several advantages that Nagelsmann already used in the past: The 3-2-5 formation provides more players in advanced positions.

This numerical superiority in the attacking third can overload the opponent’s defence, creating space and opportunities to break down their defensive lines.

With three defenders and two wing-backs, the 3-2-5 formation allows for greater width in the attack.

The wide players in Gosens and Sane can push high up the field, stretching the opponent’s defence both horizontally and vertically.

This width can create gaps in the opposing backline and enable the German national team to exploit the flanks effectively.

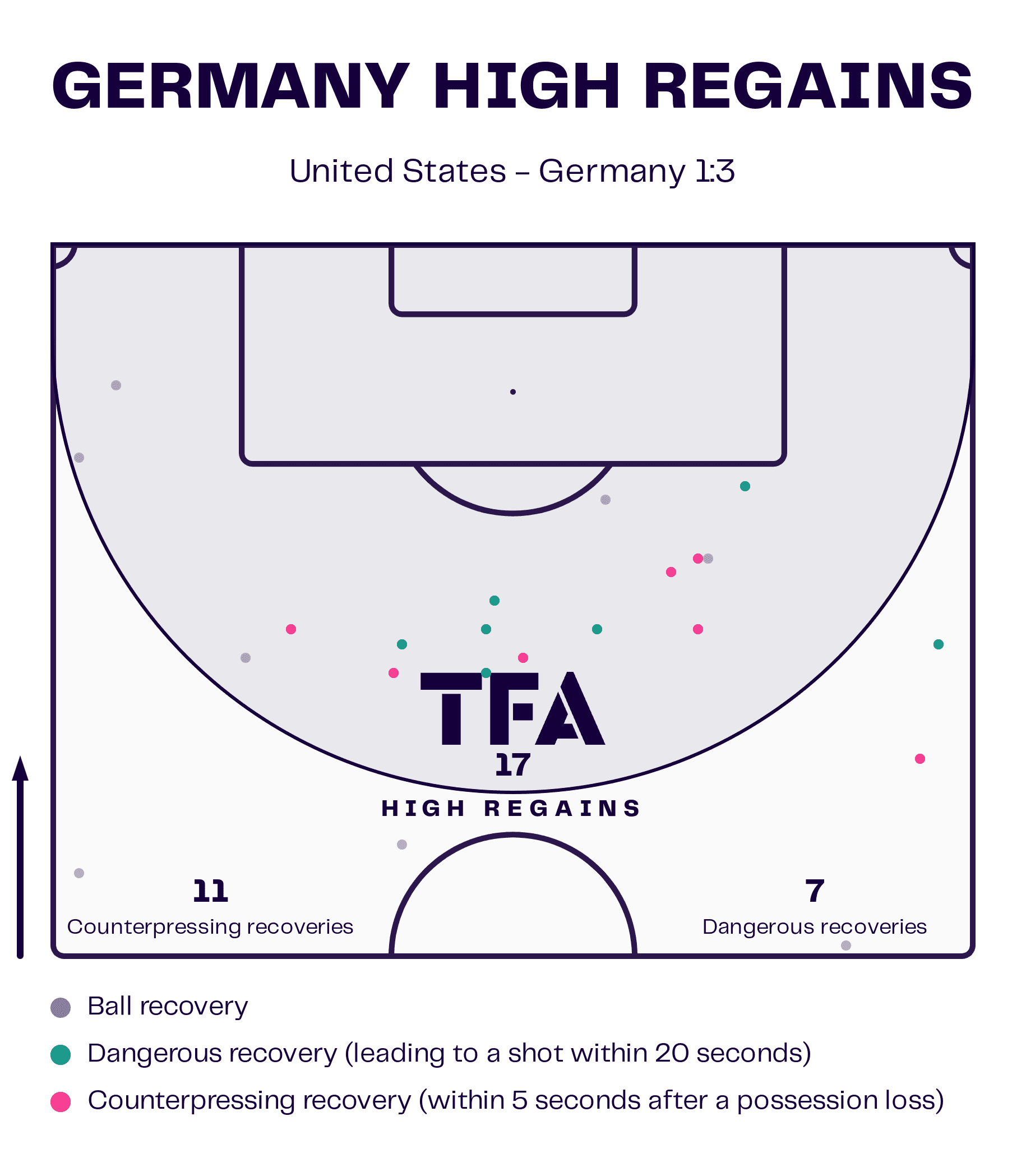

With more players positioned higher up the field, it’s easier to press the opponent closer to their goal, potentially leading to turnovers in dangerous areas.

Nagelsmann already implemented the high-press in Leipzig and Bayern, intending to have as many players as possible around the opponent’s box.

With five players positioned in advanced roles, the 3-2-5 formation can overload the opponent’s penalty area.

This can lead to more bodies in the box, increasing the probability of scoring.

The organisation of Germany’s possession play left room for improvement throughout the entire game.

In the first half, the team appeared somewhat disjointed.

The need for a rapid transition through the midfield meant that Gündogan initially struggled to get involved.

However, he gradually found his footing in certain phases.

During this period, the front four offensive players, supported by Gosens, seemed somewhat isolated from the rest of the team.

Groß could push forward but didn’t exert significant influence on the offensive.

This division became more apparent because Musiala positioned himself relatively high up the pitch.

The passing angles for crucial through balls to Füllkrug or Sane were so acute that these final passes were infrequent.

Additionally, the offensive players were positioned so closely together just outside the opponent’s sixteen-yard box that passes behind the defence appeared nearly impossible.

The shorter the distance to the goal, the less time Sane had to accelerate.

As time passed, Musiala dropped deeper, adopting a more conventional playmaker role.

This adjustment notably improved Germany’s overall performance.

Gündogan also became more actively involved in the build-up play.

Consequently, Germany managed to execute longer passing sequences, which allowed Sane and Wirtz to accelerate more effectively and take the spotlight.

Nagelsmann’s approach to positional play differs from that of coaches like Thomas Tuchel and Pep Guardiola in one key aspect: his forwards are in constant motion, with the exception of Füllkrug.

The width of the attacking shape can be absolute or relative, meaning it can stretch the opponent’s defence wide or stay as compact as the opponent’s defensive line.

Furthermore, his formation is characterised by frequent player rotations, occasionally even involving a player like Rüdiger as an additional midfielder.

This rotational style can lead to swift, intricate passing sequences that disrupt the opponent’s defensive structure.

However, as with the USA’s strategy, it can also leave Germany vulnerable to counterattacks.

This has always been a double-edged sword for Nagelsmann, as while it generates numerous attacks and pressure, it can also expose the team to counterattacks when the opponent’s wingers exploit the spaces left behind the centre-backs.

Defensive Phase

The most vulnerable aspect of the team’s performance lies in its defence.

The pressing generated at least three goal-scoring opportunities.

However, when the pressing wasn’t successful, it led to a familiar issue: the centre-backs were left exposed when the first line of pressing was bypassed.

This vulnerability is most evident when the team loses the ball in a 3-2-5 formation or, even more pronounced, in a 3-1-6 shape.

The team’s defensive shape tends to be relatively compact.

This compactness often encourages opponents to utilise the wings as an avenue of attack, a tactic that can create promising opportunities through pressing.

However, this approach also exposes the team to unwanted one-on-one situations, particularly between the opposition’s wingers and Germany’s full-backs or centre-backs.

The central midfielders, in these situations, aren’t solid defensively.

This, in turn, offers the opposition’s wingers a significant advantage, as they find ample space in the flanks to exploit.

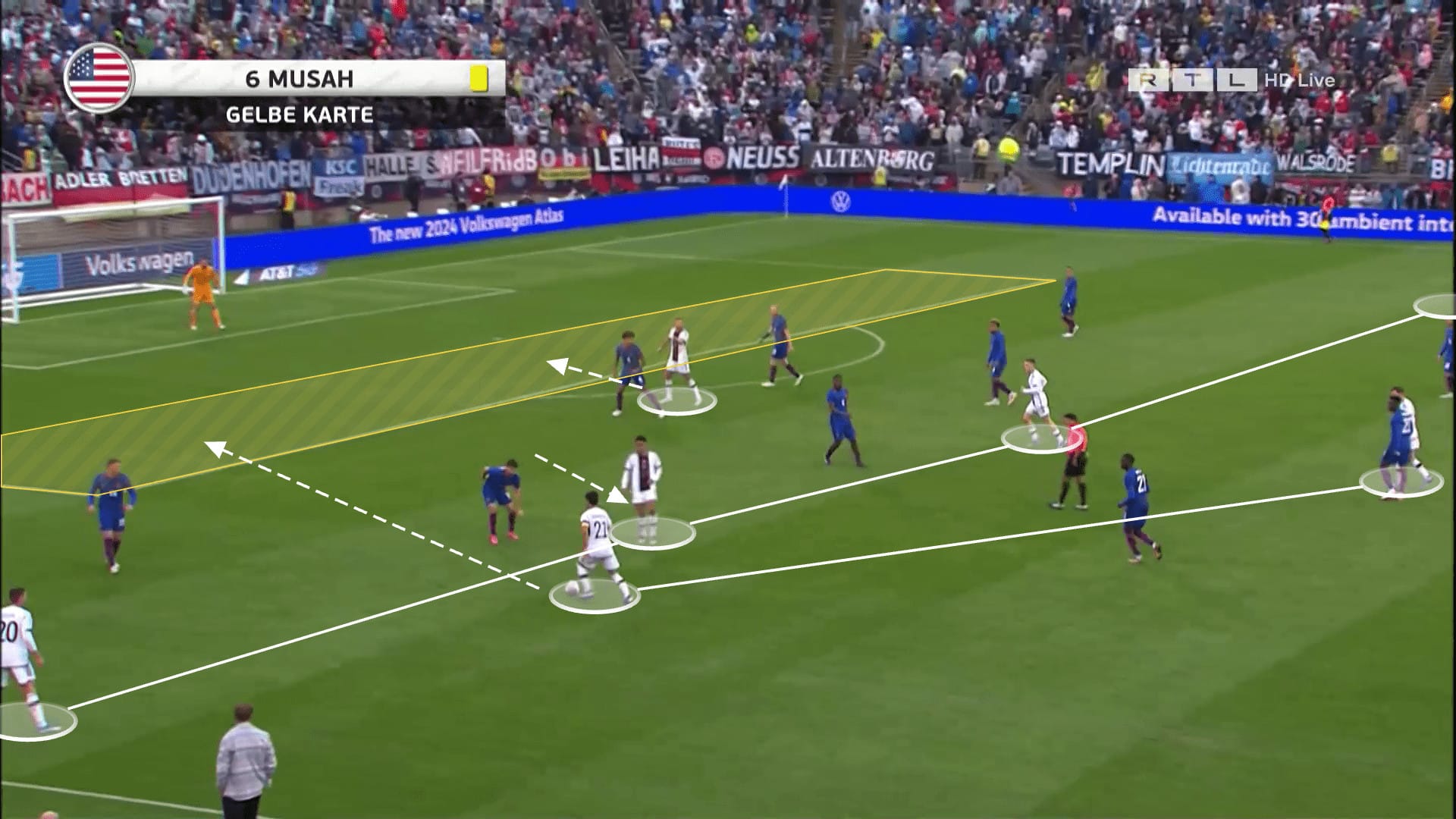

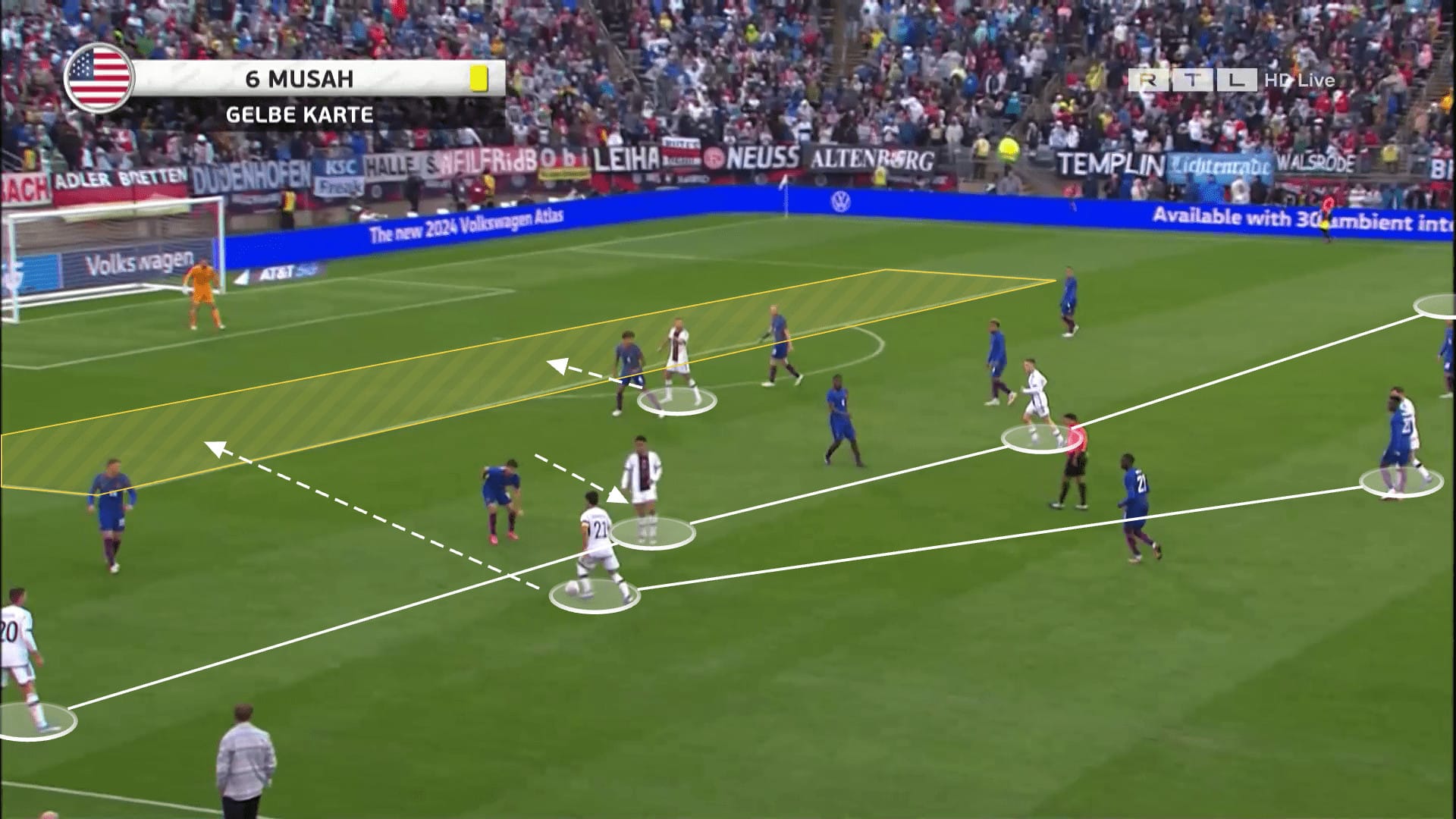

In the first half of the game against the USA, Germany faced a significant issue with their defensive coverage.

The USA managed to penetrate the attacking third frequently, partially through swift counterattacks led by the rapid wingers Weah and Pulisic.

Pulisic notably demonstrated his ability to drift from his typical position on the left wing into the central areas.

This was primarily due to Germany’s heavy reliance on man-to-man marking.

This was particularly evident during the USA’s opening goal.

In this scenario, Hummels was drawn out of the defensive line by the centre forward, while Groß allowed Musah to pull him toward the sideline.

Tah also found himself dragged toward the flank.

Consequently, Pulisic exploited the space left unattended, manoeuvring into the centre against two opponents who were essentially positioned in ineffective zones, ultimately scoring the goal.

The man-oriented approach occasionally proved excessive.

Pascal Groß, for instance, failed to cut off passing lanes or running paths effectively.

Overall, the central defensive coverage was lacking.

However, following the conceded goal, Germany showed improvement.

There was better support from the full-backs, and both Gündogan and Groß began to offer situational assistance to the wing-backs.

They covered the half-space and obstructed routes at the back to prevent the opposing wingers from easily moving into central positions and taking unchallenged shots in one-on-one situations.

This adjustment was particularly vital on the right side of the German defence, where Tah faced agility and pace disadvantages when up against Pulisic.

Germany had opportunities to score more goals, but the USA failed to fully exploit Germany’s defensive weakness, aside from one disallowed goal and the one they scored.

Against stronger opponents, these vulnerabilities could be more ruthlessly exploited.

However, these risks are deemed acceptable since both the team and its supporters prioritise attacking football over parking the bus.

Conclusion

Whether Nagelsmann will successfully transform the German national team into a competitive force for the EURO and potentially lead them to the semi-finals remains to be seen.

What’s evident is his strong inclination towards offensive play.

His philosophy revolves around swiftly advancing the ball and creating goal-scoring opportunities promptly.

With a complement of creative players and a potent striker, this approach can indeed yield results.

Traditionally, tournaments are often won by more defensively-focused, stability-oriented teams (such as Germany in 2014 or France in 2018).

Nagelsmann, however, is opting for a somewhat different path.

Yet, this alternative approach holds promise.

At the very least, Germany are offering a bit more excitement on the field than in recent times.

Comments