Julio Vaccari’s path to becoming Defensa y Justicia’s manager is a unique one. The 42-year-old began his career working for none other than Marcelo Bielsa. As a video analyst, helping Bielsa’s famously extensive and detailed methodology, Vaccari first joined the former Premier League manager at La Liga’s Athletic Bilbao. He then followed El Loco to Olympique Marseille in Ligue 1 before parting ways and becoming a part of Gabriel Heinze’s staff at Godoy Cruz, Argentinos Juniors, and Vélez Sarsfield.

Vaccari references Heinze and Bielsa as the biggest contributors to his football ideas and in his first job at Defensa y Justicia, these are definitely becoming clear. Julio claims his football to be one of position rather than possession. Like Heinze and Bielsa, he enjoys attacks with verticality and speed. In his first 18 matches, the Argentinian coach has only lost two of them. Early into the 2023 Liga Pro, Defensa y Justicia are already challenging at the top of the table.

This tactical analysis will provide an in-depth breakdown of Julio Vaccari’s tactics at Defensa y Justicia so far. With Bielsa and Heinze as references, this analysis will also examine how the 42-year-old’s tactics compare to his mentors.

Construction

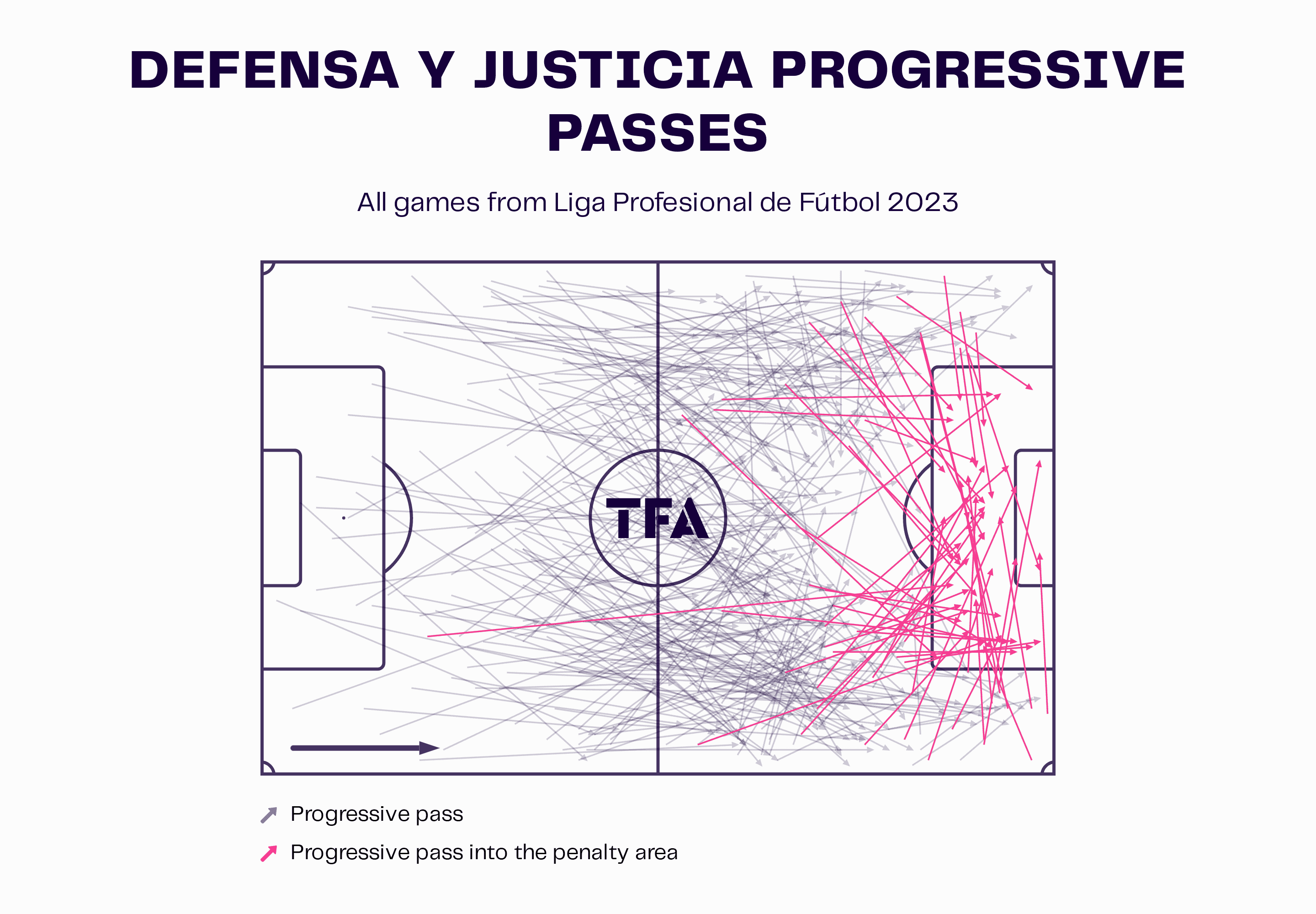

The Halcón are far from a possession-based side, with just 49.91% possession this season. Similarly, 16.51% of their 346.56 passes per 90 are long passes, already indicating a significant verticality with the ball. In fact, they average more forward passes per 90 (129.89) than lateral passes per 90 (117), a common trend in direct teams. Finally, Defensa also average 71.22 progressive passes per 90. Considering Vaccari’s men do not average many passes per 90, this figure is rather significant.

It is clear Vaccari wants his players to be direct with the ball, looking to break lines and progress forward quickly and with intensity. How is this carried out though? Let’s take a look.

Defensa mainly use a 4-3-3 in possession. Their structure tends to be quite expansive, with wingers initially remaining wide and high. Additionally, the fullbacks are instructed to maximise width and remain wide as well. While the two centre-backs split the goalkeeper, the midfield three become the heart of the structure.

This shape can be identified below. Although, as Vaccari claimed, his team is quite positional, there is a notable fluidity in this shape which enhances the effectiveness of their vertical approach.

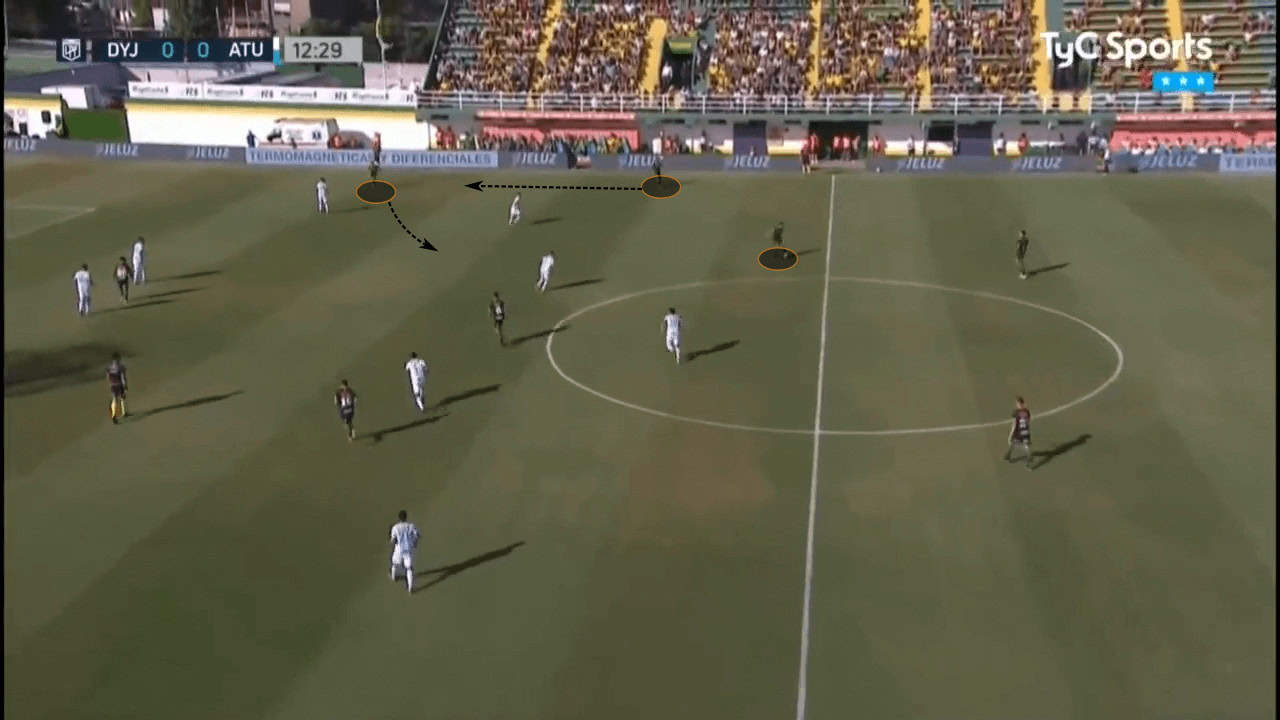

The single pivot plays a very significant role, especially in the earlier stages of possession. Usually 25-year-old Kevin Gutiérrez, the defensive midfielder will begin very close to the back four, providing immediate support in possession. He is in charge of providing outlets, like the scenario below, as well as directing the build-up.

Two central midfielders sit ahead of the single pivot, forming a midfield three. The structure of the midfield is very fluid and, at times, compact. In the first few phases of possession, the two begin higher and apart from each other in an effort to stretch the opposition’s press, support the wide areas, and provide options further up the pitch.

However, depending on the development of the build-up or stage of possession, the midfield three can remain extremely close to one another, floating in and out of spaces.

In the example below, this structure can be further illustrated. As Defensa build out of the left flanks, the three midfielders provide support. While the defensive midfielder and nearest midfielder provide immediate options, the far midfielder comes across to find space and create a more vertical option. The three work very well together to manipulate space and create options to progress up the pitch.

In another instance, the defensive midfielder and the nearest central midfielder work together to provide options to progress. With the opposite midfielder further away, the two do a great job of finding pockets of space between the defensive lines to receive the ball.

With this midfield trio being such a significant part of their structure, Defensa y Justicia often look to build and progress through the central areas.

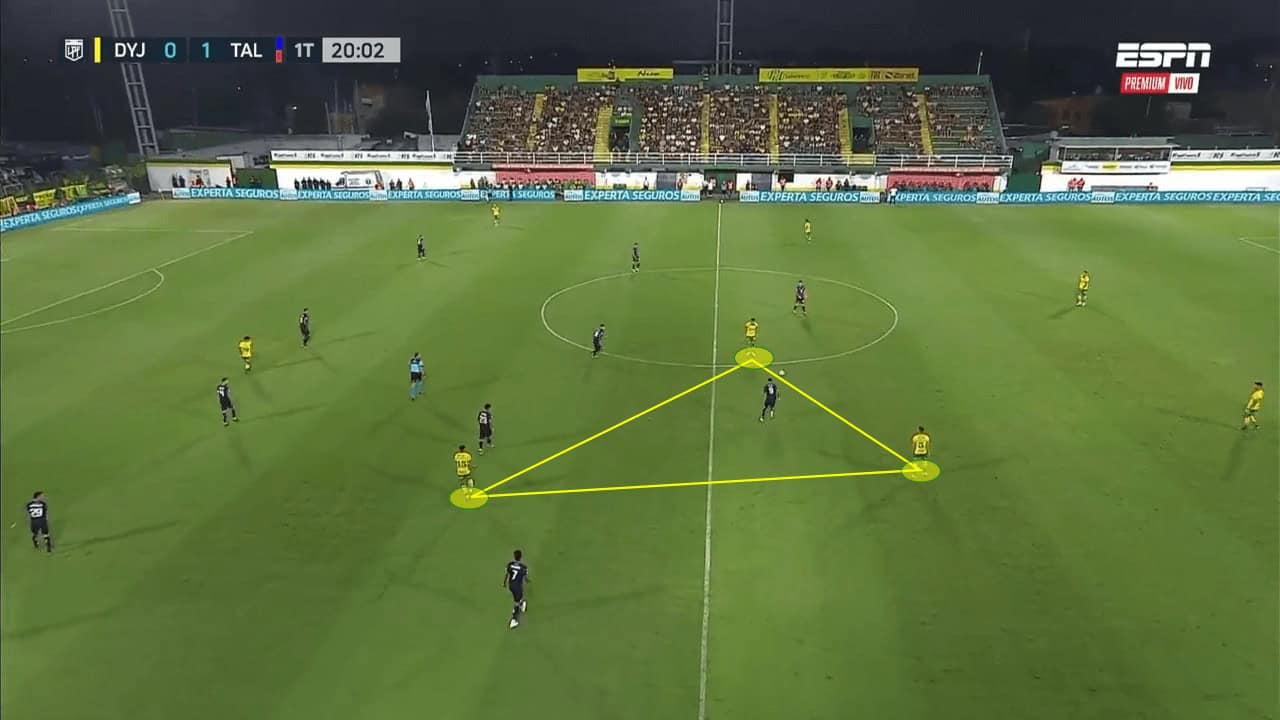

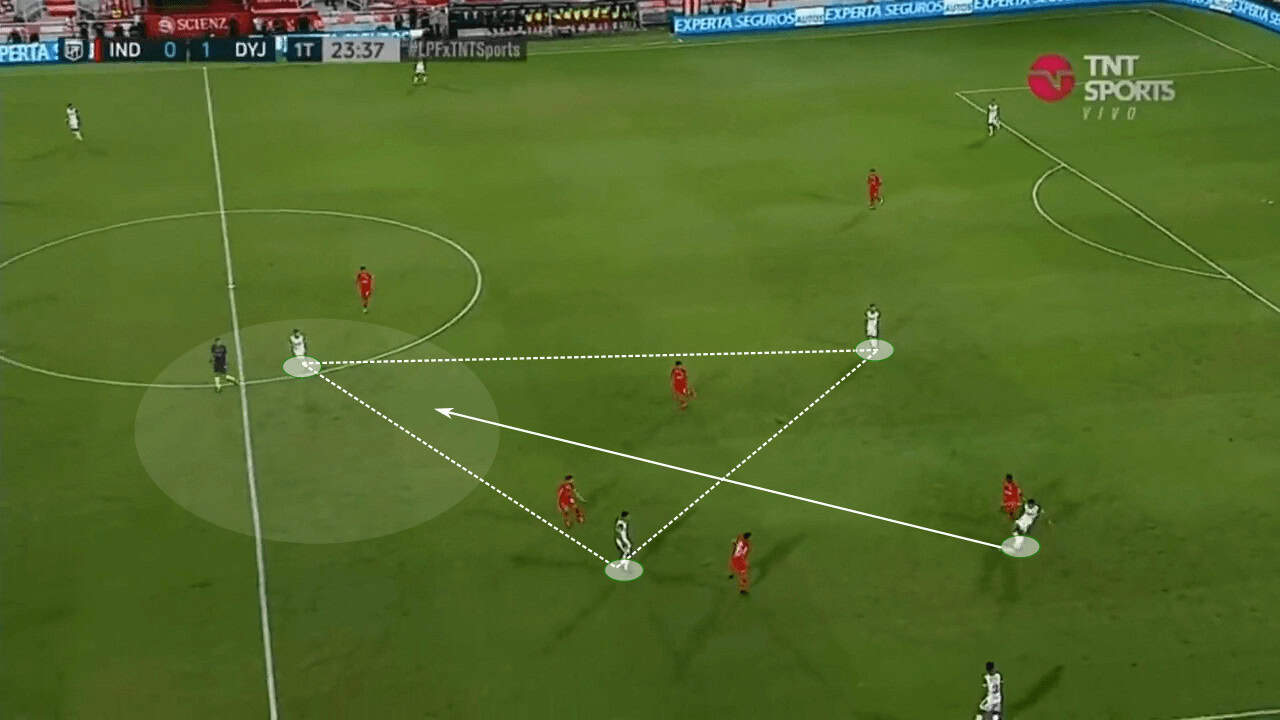

However, Vaccari’s structure also allows for effective ball progression in wide areas. Again, the single pivot plays an important role in providing angles from the central channels. Additionally, the nearest midfielder will provide support from further up the pitch. These movements tend to create two triangles, as identified below. These diagonal passing angles are extremely useful to progress through the defensive organisation.

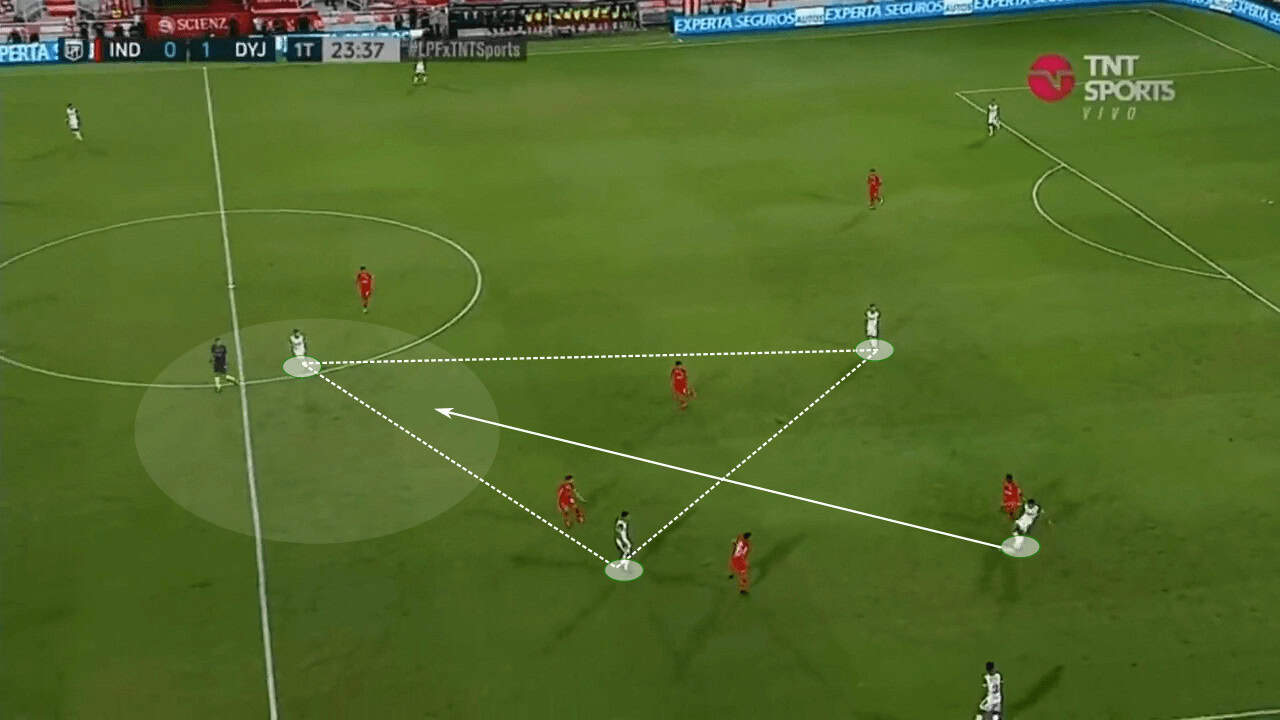

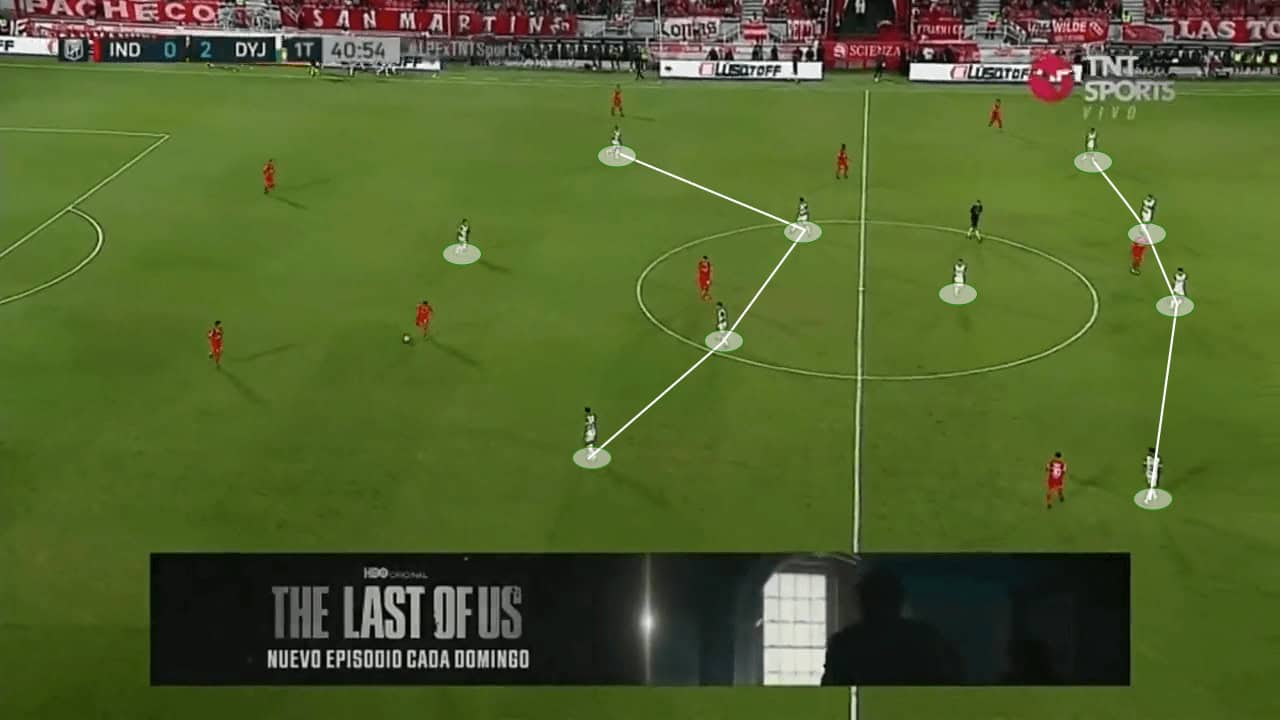

Finally, Vaccari’s men are frequently able to find the extra man and create advantageous scenarios. In the example below, against Independiente, Defensa’s build is very expansive. The front three do a good job of pinning the back four further up the pitch. This creates a +1 against Independiente’s press, essentially a 7v6 (8v6 if you include the goalkeeper).

A common strategy, Defensa tend to lure the opposition into one side before exploiting a 2v1 on the opposite side, usually through a quick long switch.

Vaccari’s build-up is carried out through a very balanced shape, usually in a more vertical manner. The 4-3-3’s midfield plays a significant role in progressing through the middle as well as providing support to either wide area. Additionally, with the front three pinning the opposition’s back four, they are often able to exploit the numerical superiority and create advantageous scenarios. With this structure, the players ensure a high-tempo possession looking to break lines and go forward as soon as possible.

Wide dynamics

The attack is not much involved in the first few stages of possession, and the wingers’ only role is to pin the opposition’s backline. However, as Defensa y Justicia progress forward, the wide players have an incredibly significant role in the structure. The fullbacks have the freedom to venture forward and support the attack, and this creates very dangerous dynamics in the wide areas.

First, their progressive pass map this season can provide an initial illustration. In the first two-thirds, the majority of their passes are delivered into the central channels. On the other hand, as they get into the final third, their progressive passes look to reach the wide areas, with almost no passes to the central channels outside the box.

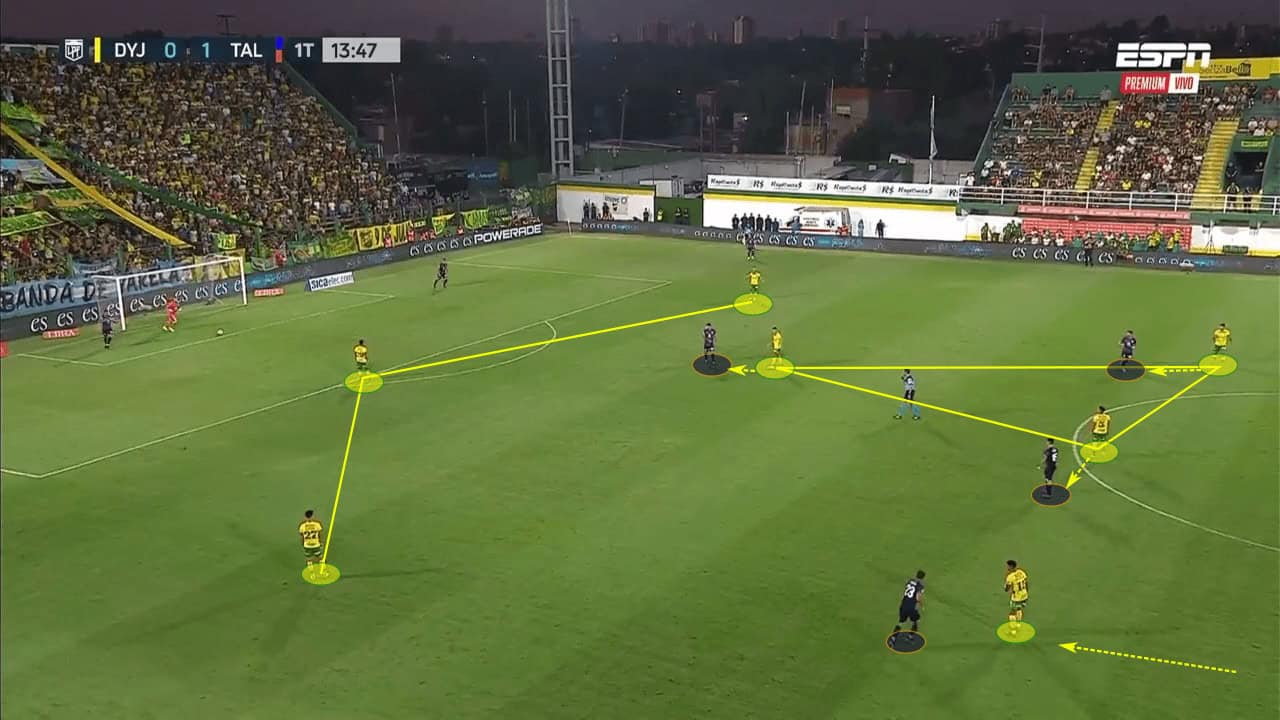

This change in focus is very notable, and Defensa do an extremely good job of effectively exploring the wide areas. Initially, in their 4-3-3, the fullback and the winger fill the wide channels. As identified in the example below, their movement tends to be very fluid and intelligent. Specifically, in the instance below, the midfielder is able to find the winger checking inside. After receiving, the winger plays wide to the overlapping fullback. This pattern is simple yet extremely effective, and Defensa look to explore it frequently.

Later in the same match, a different scenario can be identified in the wide area. In this instance, the fullback remains deeper, but Vaccari’s men are still able to explore the wide areas successfully. As the winger receives the ball, the centre-forward provides immediate support while the central midfielder makes an overlapping run out wide. The centre-forward plays the central midfielder through and they reach the final third in a dangerous manner.

The central midfielders play a key role in making the wide areas so dangerous. As identified in the build-up, the angles they can provide from the inside channels are extremely beneficial. Illustrated in the example below, the central midfielder provides a diagonal pass further up the pitch while the fullback shows wide. This creates a 2v1 against the defender and the central midfielder receives it with time.

After receiving, he plays another diagonal pass, this time to the winger who is hugging the touchline. Julio identifies his side as one of position, not possession. This example perfectly illustrates this. With just two passes, Vaccari’s men progress from their third into the final third, a direct result of the positioning of the players.

Earlier in the same match against Independiente, a very similar pattern can be identified. This time, the fullback plays it forward to the winger, who after receiving, plays it inside for the central midfielder. Again through intelligent positioning and movements, they are able to quickly break lines and progress forward. And again, the movement of the central midfielders is key.

Defensive system

Bielsa is known for his relentless man-marking defensive system. The intensity, especially defensively, was unquestionable. Similarly, Heinze’s teams are known for their intensity. Logic would indicate Julio Vaccari would have a similar approach. Although there are similar trends in the organisation, especially in the man-marking adaptive manner, the intensity is not quite the same, at least currently.

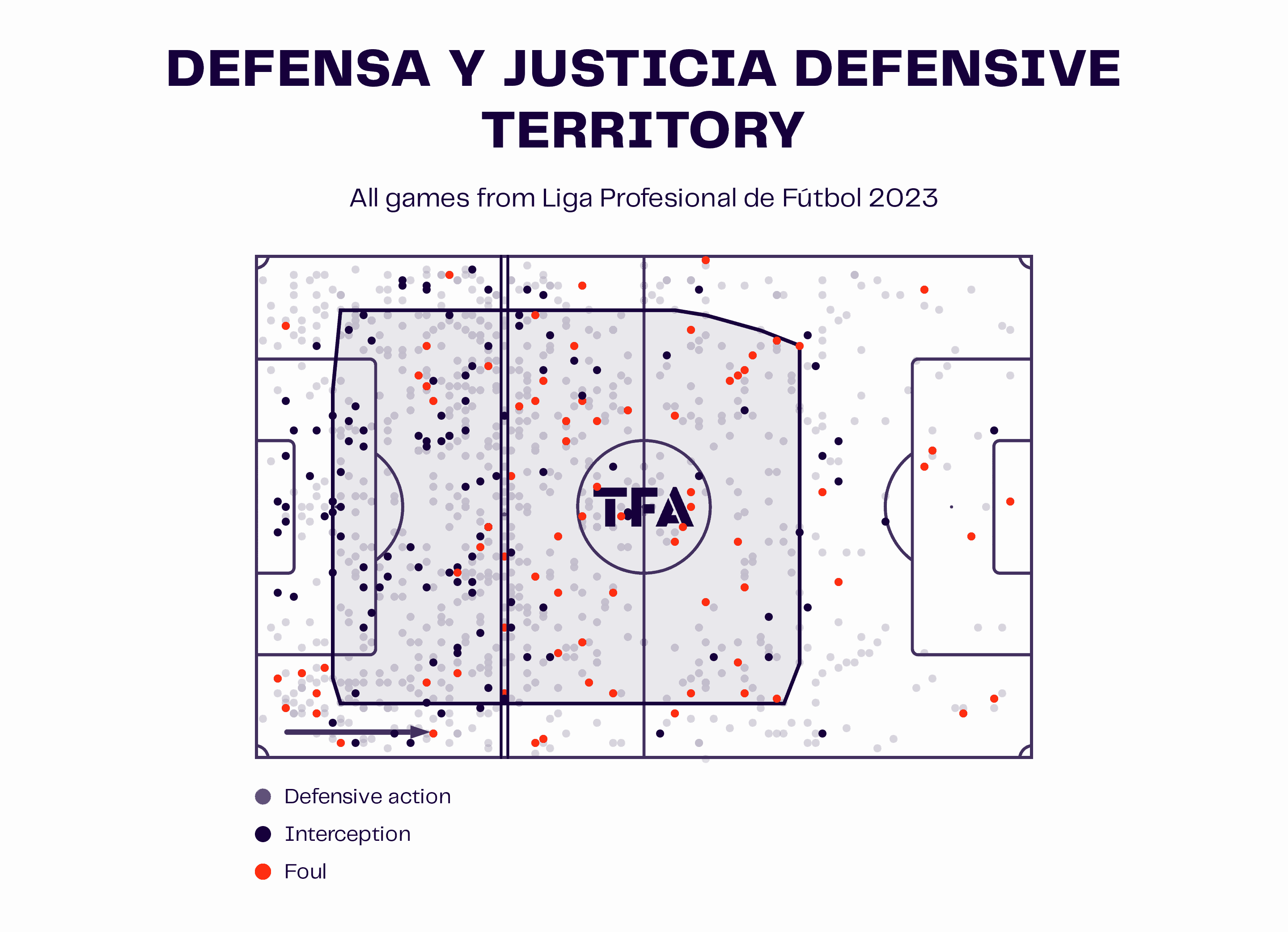

Defensa y Justicia’s PPDA this season currently stands at 10.1, far from a significant figure. As identified by their defensive territory map below, the Halcón tend to begin with a lower defensive block and a more passive approach. The majority of defensive actions are located in the middle third, without much activity in the final third.

The defensive block is initially organised in a 4-1-4-1/4-3-3 shape, with the defensive midfielder playing a crucial role between the defensive lines. However, depending on the opposition’s midfield structure, this can change into a 4-4-1-1 or a 4-2-3-1, depending on the height of the wingers.

The focus on numerical formations serves to illustrate the defensive organisation of Defensa y Justicia. Adapting to the opposition’s midfield structure, their defensive tasks become clearer, without much need to deviate from the organisation. They certainly look to maintain a zonal organisation with a set shape. However, this shape is already adapted to man-mark the opposition.

Against a double pivot, the organisation remains the same. Identified below, the two central midfielders pick up the opposition’s double pivot while the defensive midfielder provides cover behind. In the instance below, they are in a much higher block. Defensa certainly look to press high at times, but the consistency, especially in the intensity, is not significant.

Against a single pivot, on the other hand, Vaccari adapts to the opposition’s structure. They invert the midfield to form a 2-1 and man-mark the opposition’s midfielders. Below, we can also identify the fullback pushing high to track his man.

Adapting the structure, Vaccari looks to perfectly fit against the opposition and make it hard to find the free man. If attackers look to drop in from further up the pitch, the defenders are instructed to track these runners.

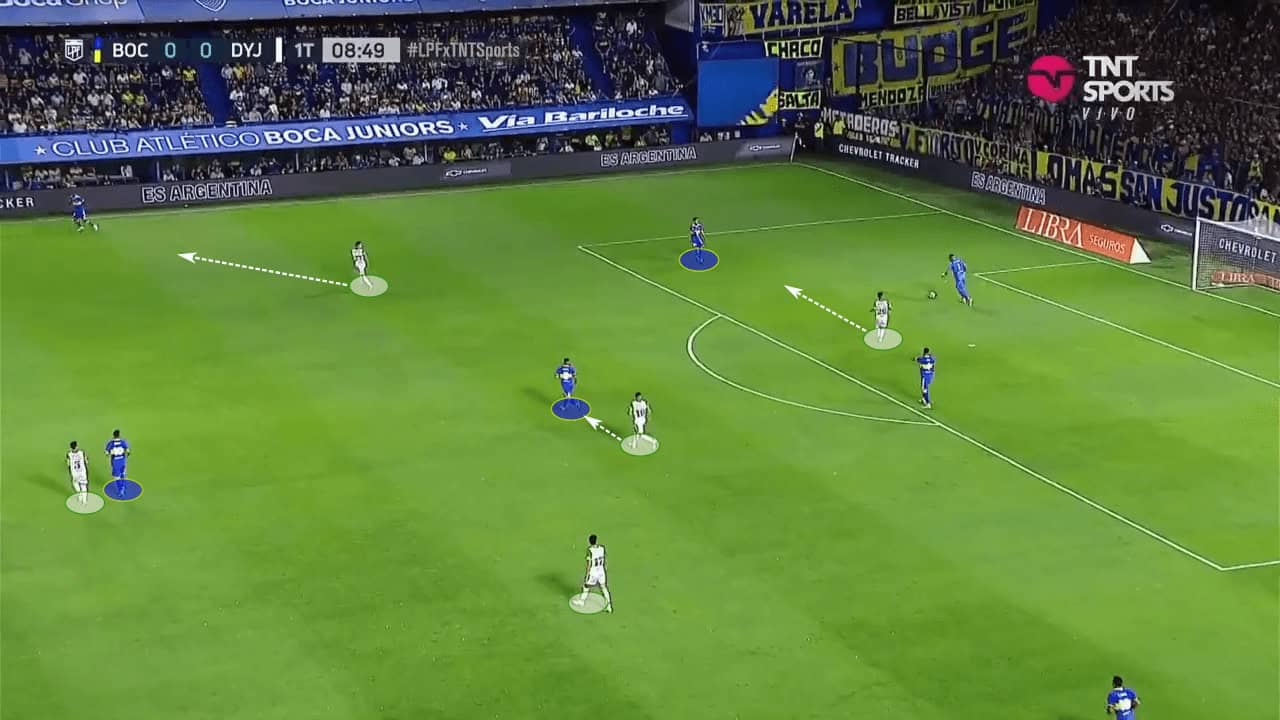

This mix between zonal and man-marking orientations can be further illustrated against Boca Juniors, in the segment below. Boca build up with a single pivot, so Defensa adapt their structure accordingly. Vaccari’s three midfielders man-mark Boca’s midfield trio.

However, as Boca play out wide, Defensa shift their assignments to keep the opposition from progressing further. The deepest midfielder jumps wide to press the ball receiver, and the second midfielder drops back to pick up the opposition player left behind. These quick rotations happen in the more vertical scenarios when they are required to quickly reorganise and immediately stop the progression.

Conclusion

After an interesting path to his first managerial job, Julio Vaccari’s life with Defensa y Justicia has gotten off to a fantastic start. With Bielsa and Heinze as his mentors, it is clear the Argentinian managers’ ideas have rubbed off on Vaccari.

The 42-year-old claims his football to be one of position rather than possession, and this is clear so far at Defensa y Justicia. The Argentinian side is extremely vertical, with very effective positional patterns. Defensively, Vaccari’s tactics resemble Bielsa’s style, with a clear adaptive man-marking approach. However, the traditional intensity is not quite there just yet.

In just his first managerial job, Julio’s future is extremely promising. It will be interesting to follow his path as well as the development of his ideas.

Comments