A question that plagued every South Korean football enthusiast was will Ki Sung-yueng be match-fit to play against Ulsan Hyundai Motors? The former Celtic and Swansea man did play the match but he had to start from the bench.

Apart from both the teams needing to earn all three points due to different reasons, the K-League 1 fixture between Ulsan Hyundai and FC Seoul had numerous mouth-watering aspects. It would be the comeback for one of South Korea’s most favourite sons. It would be the first-ever ‘Double-Dragon derby’ played in South Korea and would be Lee Chung-yong’s first match against his boyhood club.

This fixture was a cagey affair through and through, and few might claim the Double-Dragon derby did not live up to the hype and they won’t be completely wrong.

In this tactical analysis, we will discuss what made the match a cagey affair, and if Ulsan Hyundai were victorious in the true sense or did Kim Ho-young outclass his counterpart, Kim Do-hoon, despite eventually losing the match?

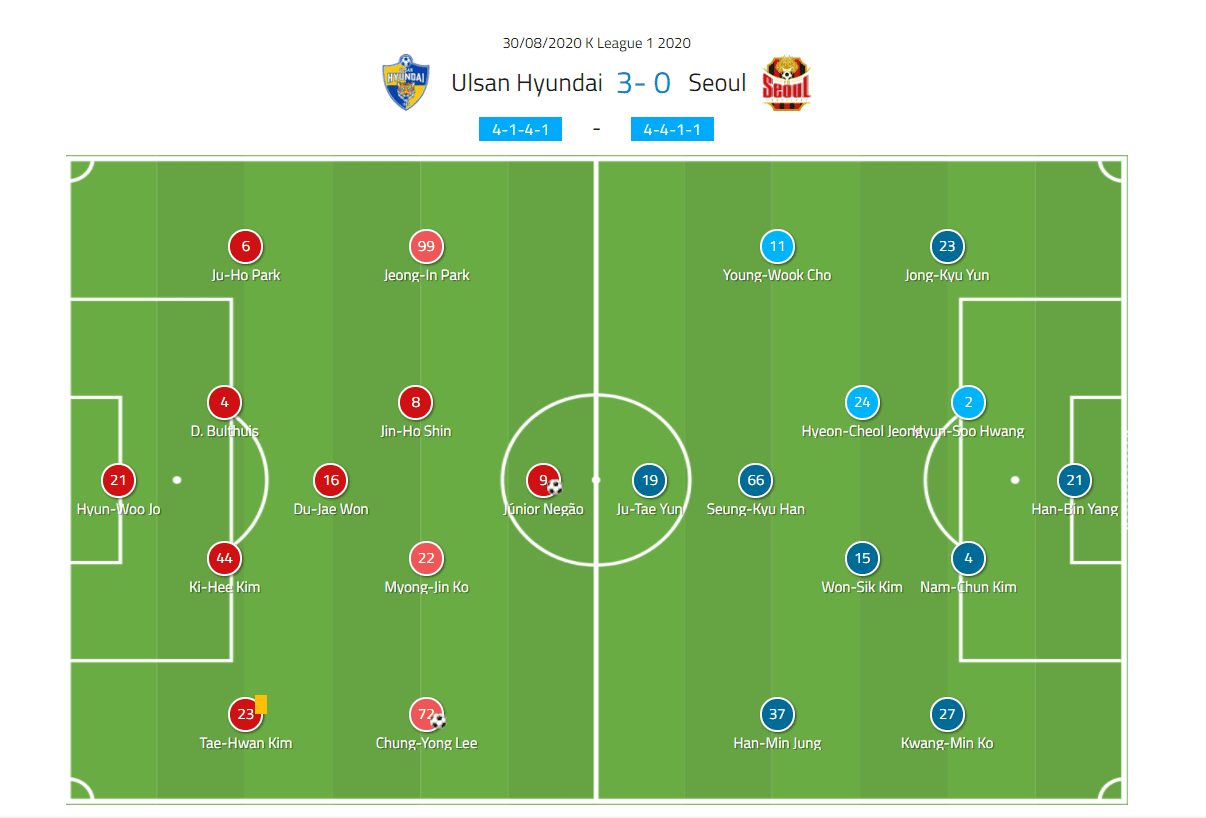

Line-up

Kim Do-hoon stuck to his preferred 4-1-4-1 but made some changes to his line-up from the previous fixture. Jung Seung-hyun missed out due to accumulating five yellow cards. He was replaced by Kim Ki-hee in the heart of the defence. Park Joo-ho, the former Borussia Dortmund left-back, replaced Hong Chul. The two other changes were Ko Myong-jin and Shin Jin-ho in places of Yoon Bit-garam and Kim Sung-joon in the midfield.

Kim Ho-young too stuck with his preferred 4-4-1-1 formation but made only one change to his line-up. Cho Young-wook replaced Yang Yu-min on the right-wing. Ki-Sung –yueng made his much-anticipated return in the 66th minute.

Seoul’s cage trapped the Ulsan Tigers

Seoul have improved massively out of possession under their caretaker manager, Kim Ho-young. Against Ulsan, Kim favoured a Liverpool alike 4-3-3 cage, when not in possession.

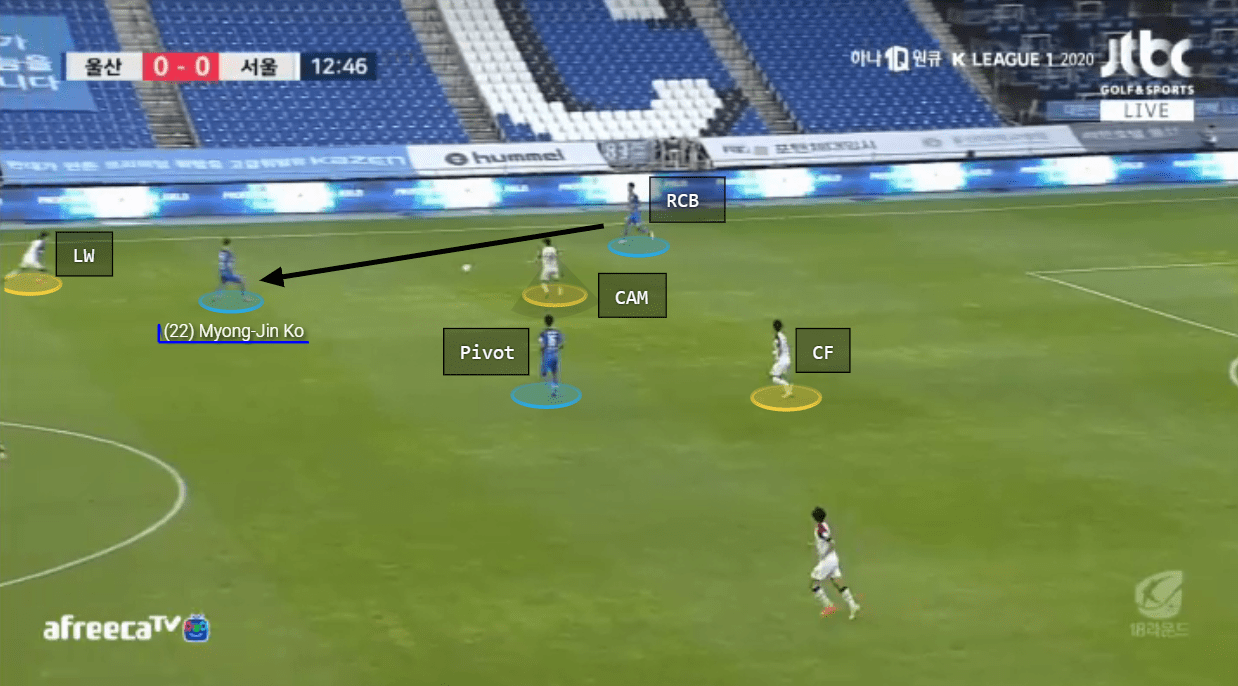

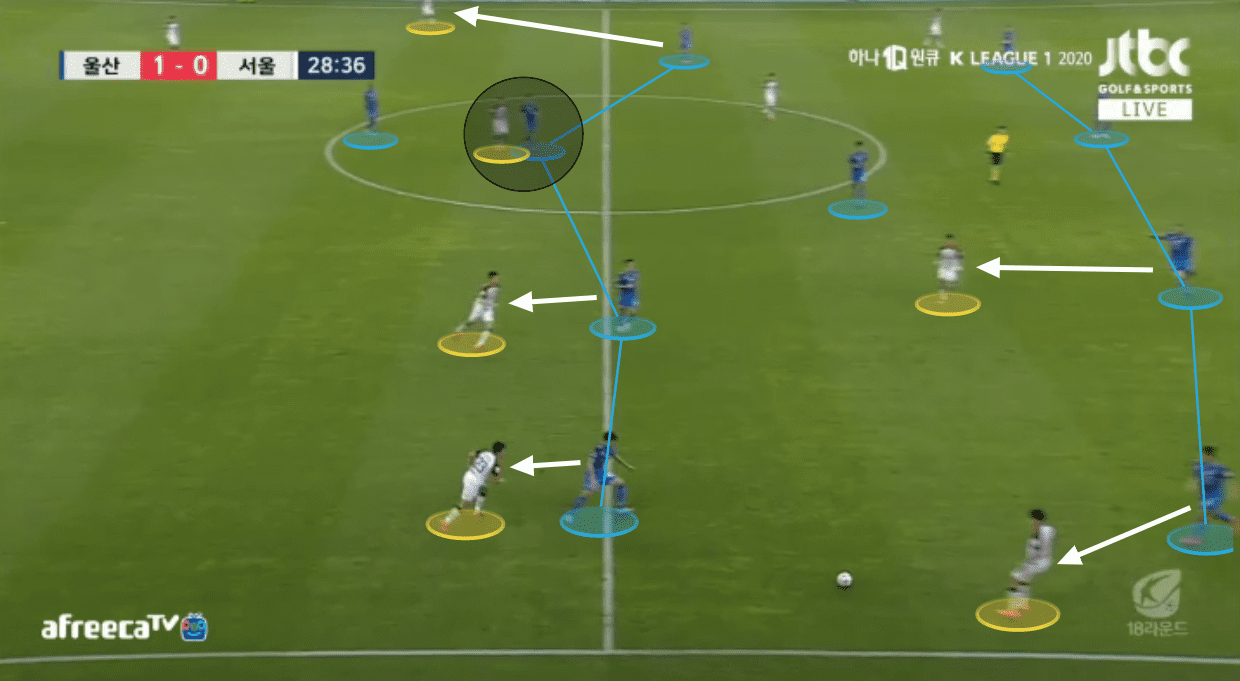

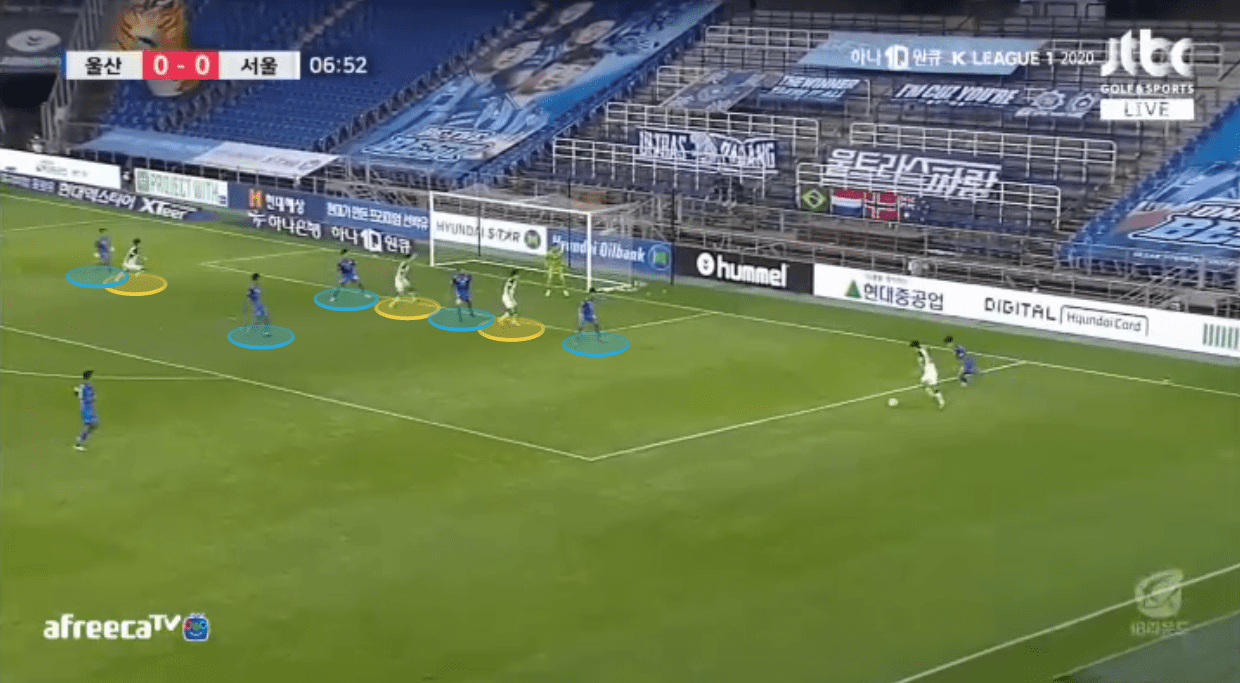

The first and the second line of defence adopted a high block to form the cage. The striker cover shadowed or followed the pivot when the ball is in the central channel. The central attacking midfielder (CAM) joined the striker and either of the wingers completed the first line of defence. When the ball is circulated on the left flank (from Seoul’s perspective), the left-winger joined the striker and the CAM in the first line of defence and when the ball is circulated on the right flank, the right-winger does the same. The major idea was to force Ulsan to play through the central corridors and create a pressing trap.

Initially, the ball was on the right flank (from Seoul’s perspective) and the first line of defence consisted of the right-winger, the CAM, and the striker covering the passing lane to pivot. Dave Bulthuis with no forward option passed the ball laterally to the other centre-back who was wide on the left-flank (from Seoul’s perspective). When that happened, the first line of defence shifted to the left-winger, the striker, and now the CAM is covering the passing lane to the pivot. With the left-winger covering the passing lane to the full-back wide on the flanks, the RCB has no forward passing option other than the dropping Ko (RCM).

As soon as the RCB passed the ball to Ko (RCM), immediately a cage was formed by the first and the second line of defence. Ko did find a passing option in the form of the inverted RW (Lee) but soon he too found himself in Seoul’s cage and instantly Seoul forced a turnover.

In the image below, you can see Yun Ju-tae (CF) cover shadowed Won (pivot), Cho (RW) prevented the passing lane to Ulsan’s LB, thus again forcing Bulthuis to opt for a lateral pass to the other centre-back.

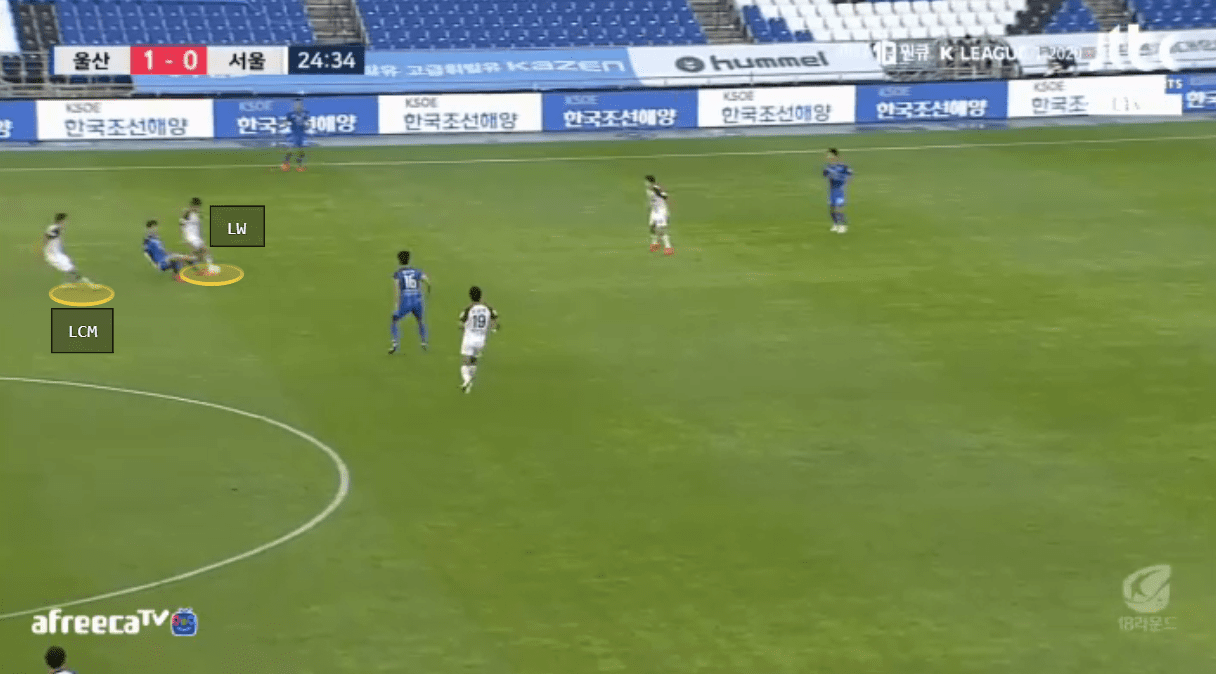

The RCB again unable to find a short forward passing option was forced to play in the central corridor to the dropping Ko (RCM). Here, the LW and LCM of Seoul both pounced on Ko and almost recovered the ball if not for the foul.

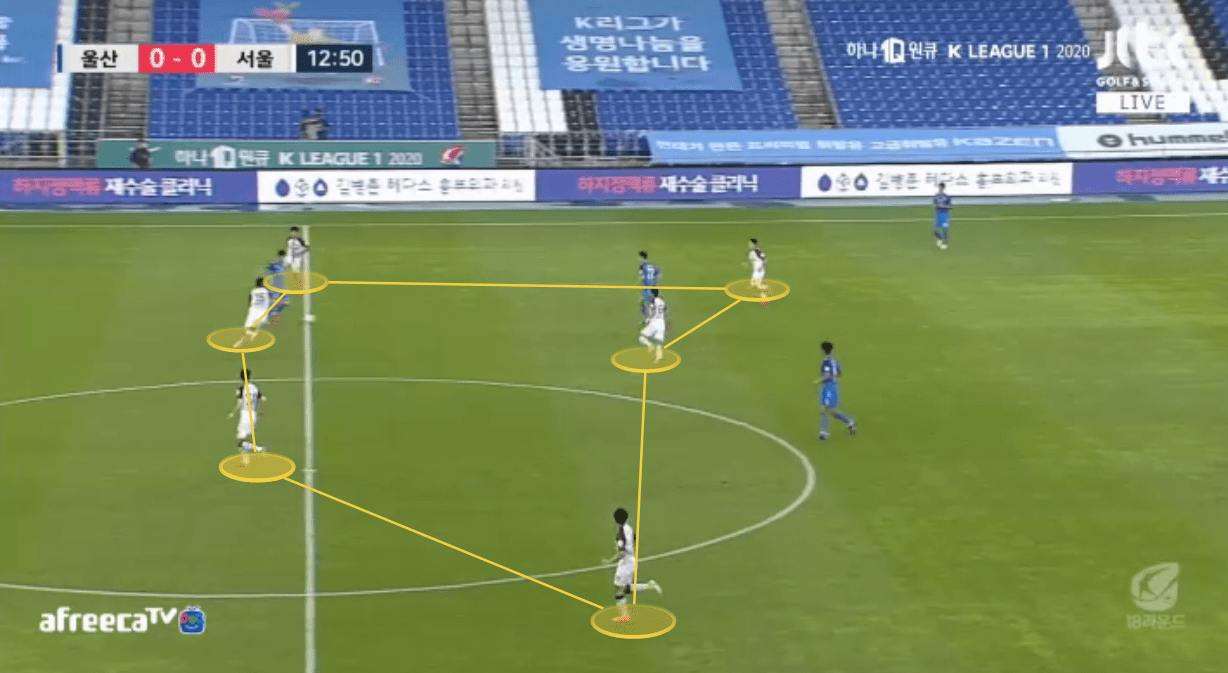

When an Ulsan midfielder drops to open up a passing lane for his defenders, a Seoul midfielder from the second line of defence presses him if no other Ulsan player overloads his area and thus forces the dropping Ulsan player to either create a turnover or play it back to his teammates. Due to this formation of the cage in the middle third Seoul recovered the maximum balls in the middle third, 24.

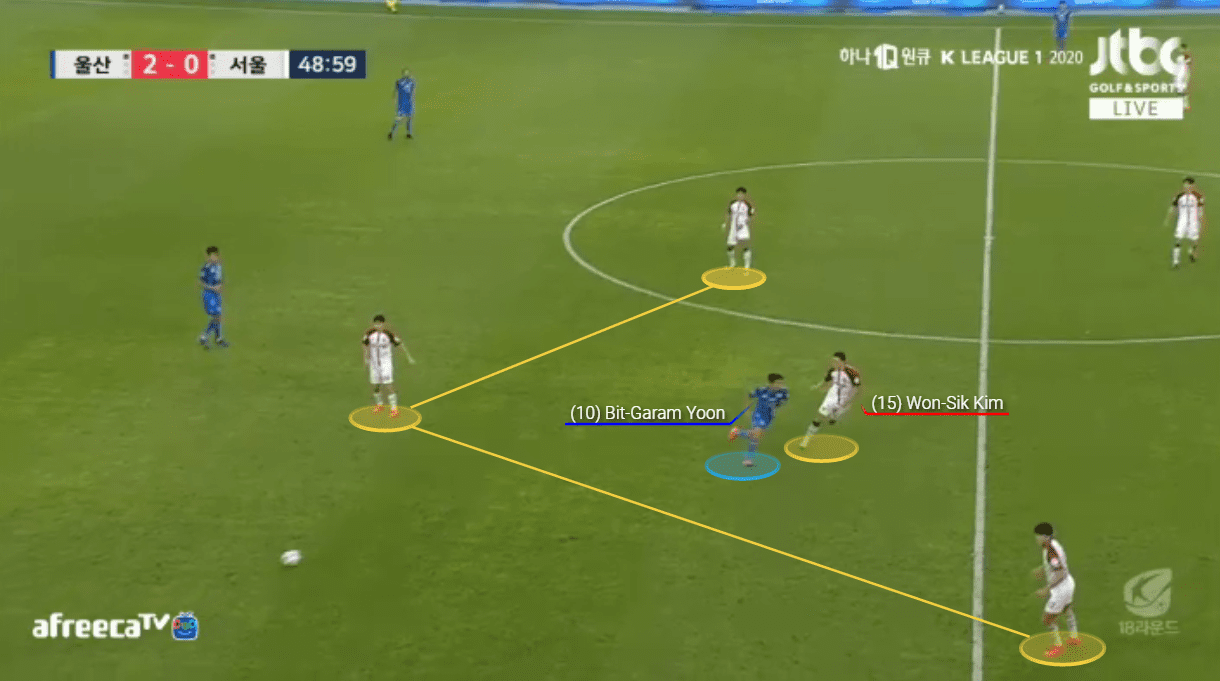

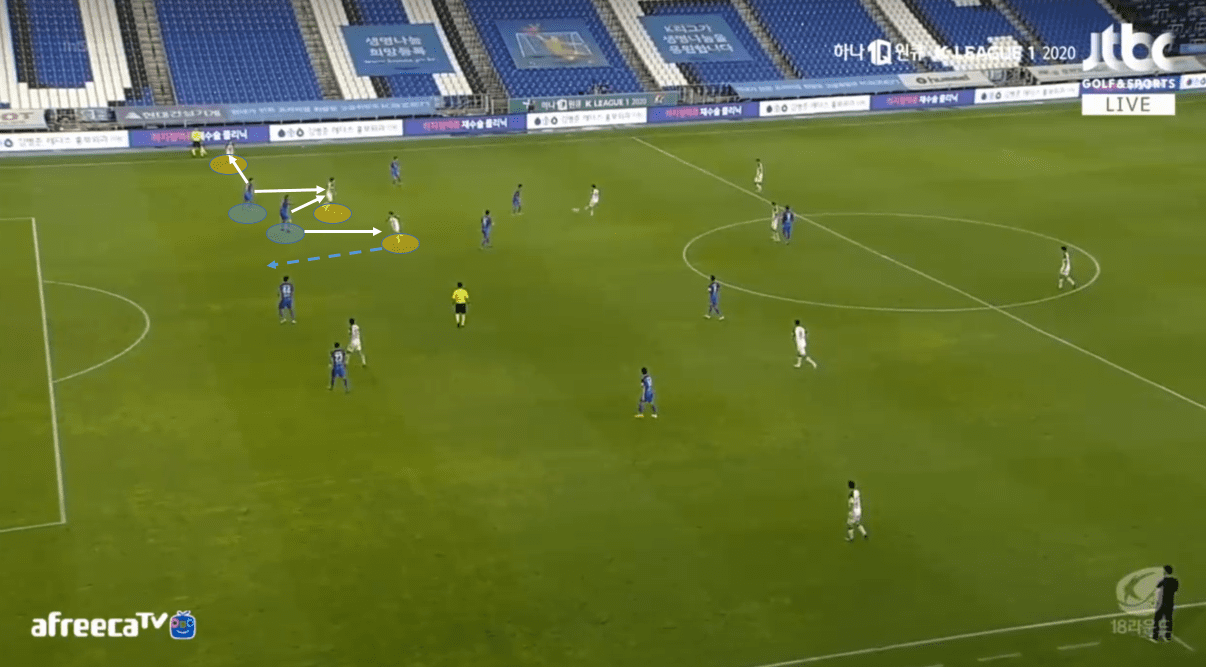

Here, Yoon Bit-garam drops to open up a passing lane and Kim Won-sik follows him.

To break out from the cage in the central corridor, Ulsan tried to devise a method by dropping one of the midfielders wide to the flanks and push the full-backs higher to disrupt the cage as well as play through the flanks and not entering the danger zone.

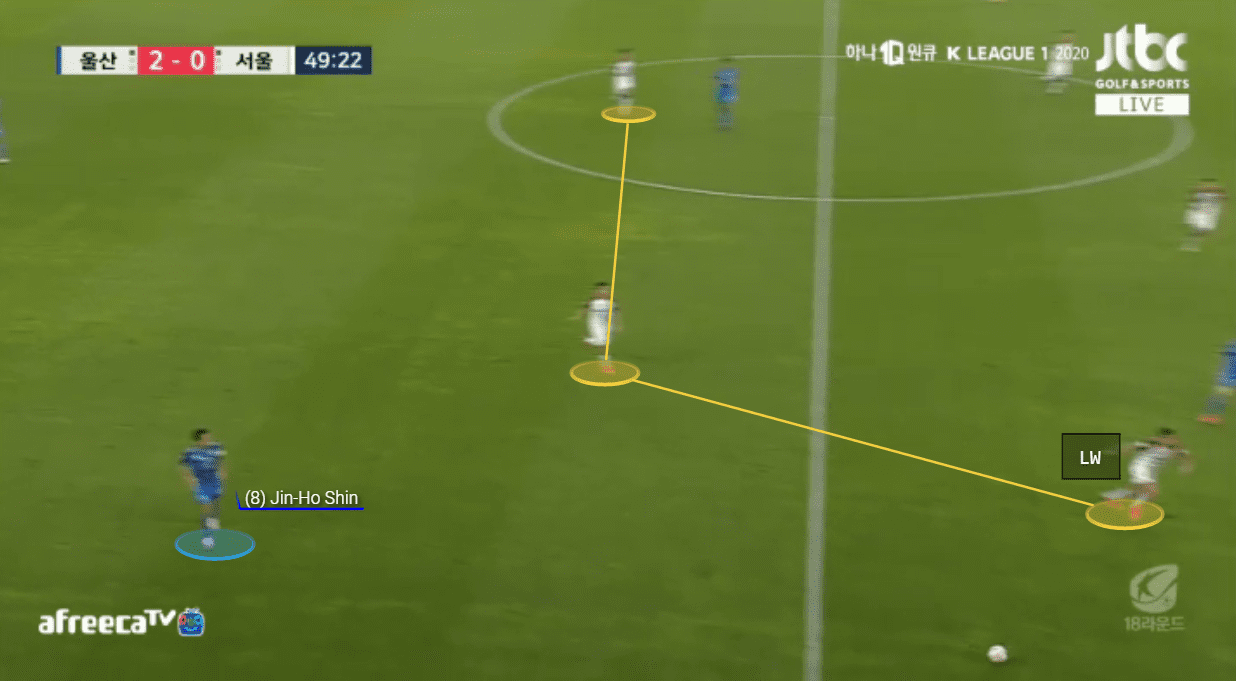

Here, as you can see, Shin drops to the position of the right-back and pushes the right-back higher. As the right-back is pushed higher, the left-winger of Seoul dropped deep to cover the right-back, thus leading to a bit of space for the RCM to operate.

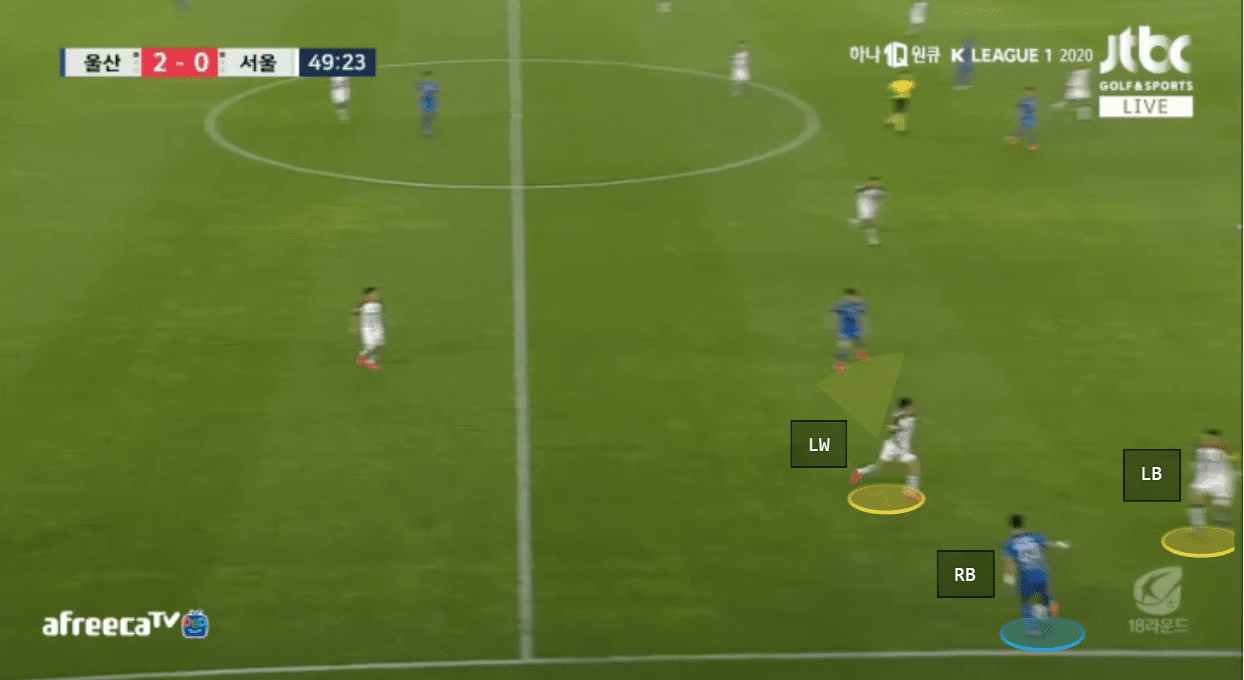

However, as soon as the RCM passed the ball to his right-back, the LB and LW of Seoul immediately pounced onto him.

Seoul’s cage trapped the Horangi in the middle third thus disrupting Ulsan’s build-up completely. Ulsan could register only 15 positional attacks, their lowest in the campaign. Even against Jeonbuk Motors (reigning champions), Ulsan registered 19 positional attacks with ten men for more than 60 minutes. This showcases the brilliant, out-of-possession tactics Kim Ho-young indulged in. Only in the last 13 minutes did Seoul’s pressing trap collapse, owing to their eagerness to force a comeback.

Horangi’s 29 PPDA

Ulsan adopted space-oriented coverage, out of possession. It means Ulsan neither went solely for zonal coverage nor man-oriented pressing rather preferred a mix of these two. The players maintained their positions rather than closely marking the opposition players and pressed relative to the opposition player’s proximity to their space.

Whether the Horangi opted for a midblock or a low block, the home team followed the space-oriented coverage all time.

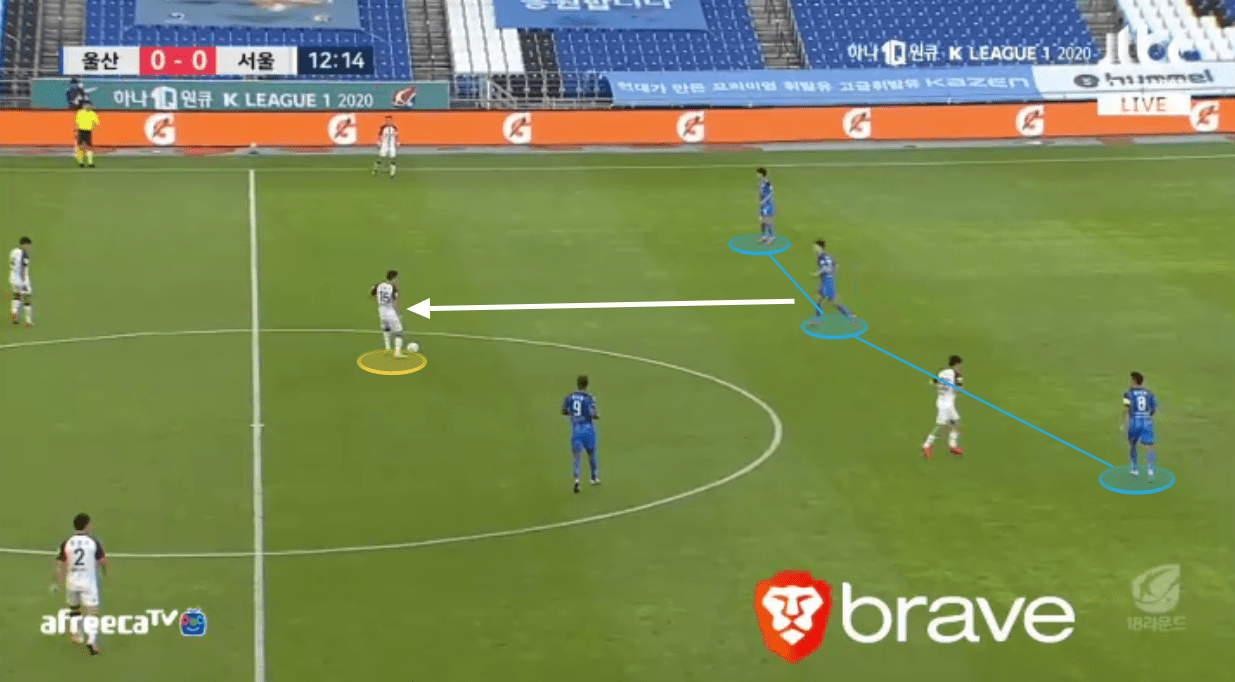

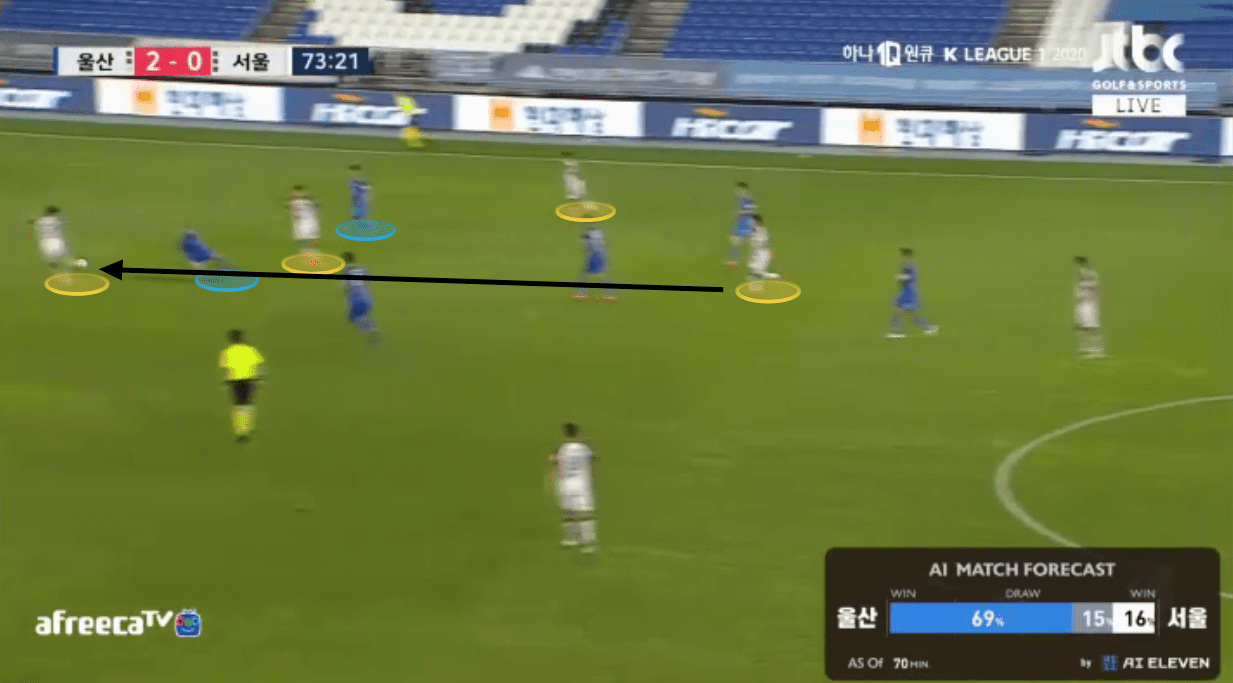

In the screenshot above, the Horangi sat in a 4-1-4-1 midblock, with each Ulsan midfielder covering the Seoul players in their proximity. The other aspect of the home team’s midblock or low block is that if the striker drops deep, the centre-back nearest to the striker follows him.

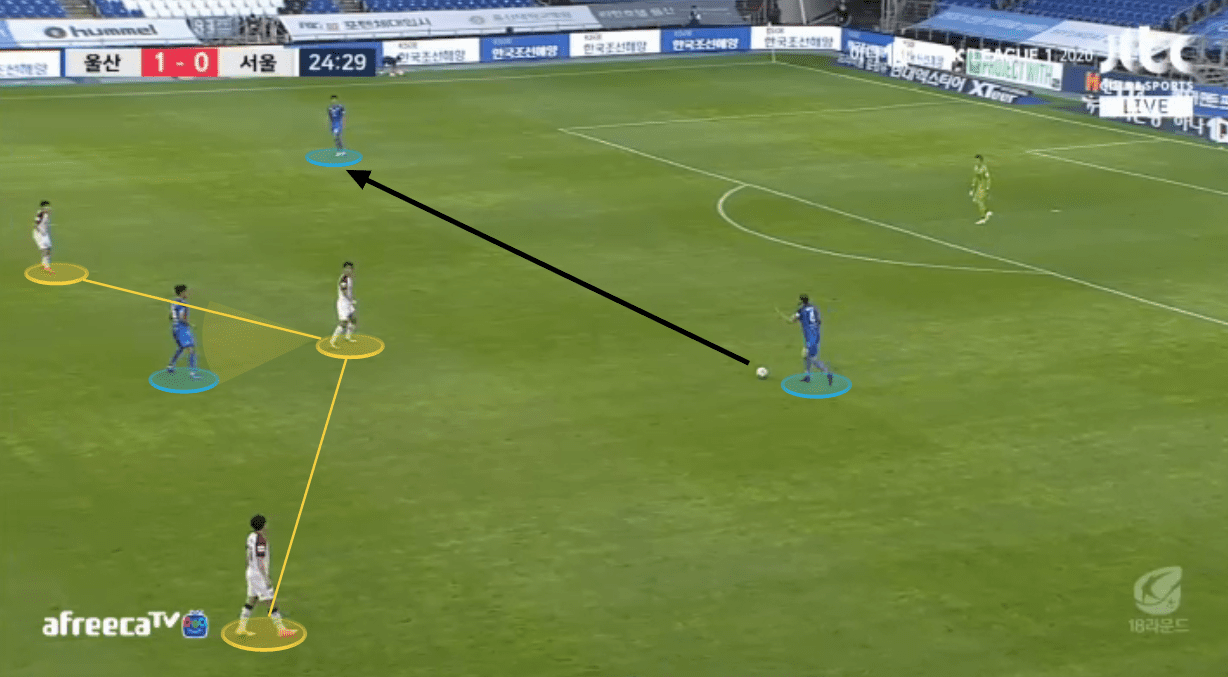

In the screenshot below, a low block by Ulsan is demonstrated. In a similar manner, Ulsan position themselves in a 4-1-4-1 and if the ball-carrier (mainly midfielders) takes too much time on the ball, the Ulsan midfielder close to his proximity moves up to press him.

As you can see, Kim Won-sik takes too much time on the ball, so the midfielder (Ko Myong-jin) close to Kim’s proximity moves up to press him.

Ulsan hardly pressed Seoul if not in their own half which clearly indicates the high PPDA of the Horangi.

The inverted wingers

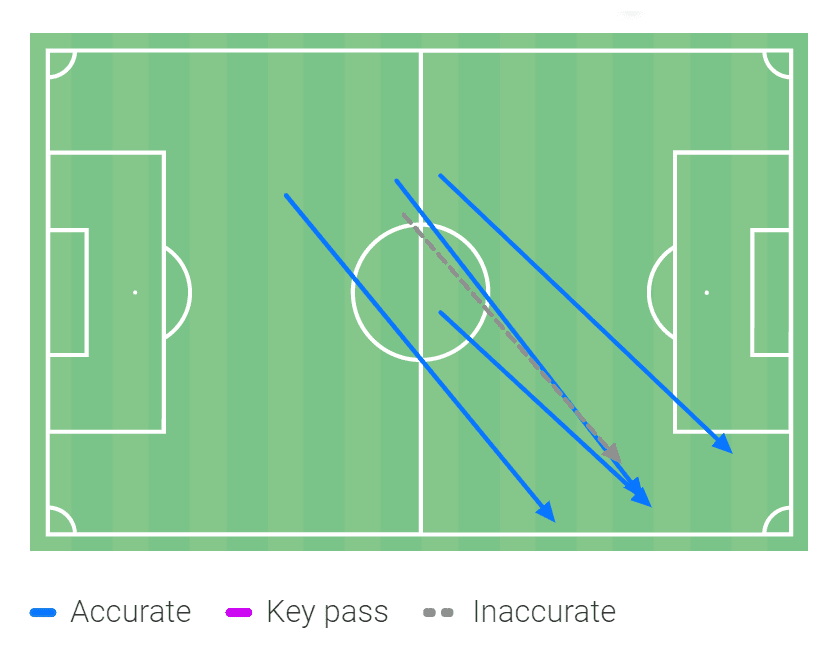

It was almost impossible to break Ulsan’s low block/mid block through the central channel or the half-spaces as the Horangi were too compact in the centre. So, the Seoul midfielders tried to play diagonal long balls from the centre to the full-backs who acted almost as a winger.

Above is the long pass map of one of Seoul midfielders, Kim Won-sik, who played five long balls in the match and all were diagonal from the central channel or the opposite half-space.

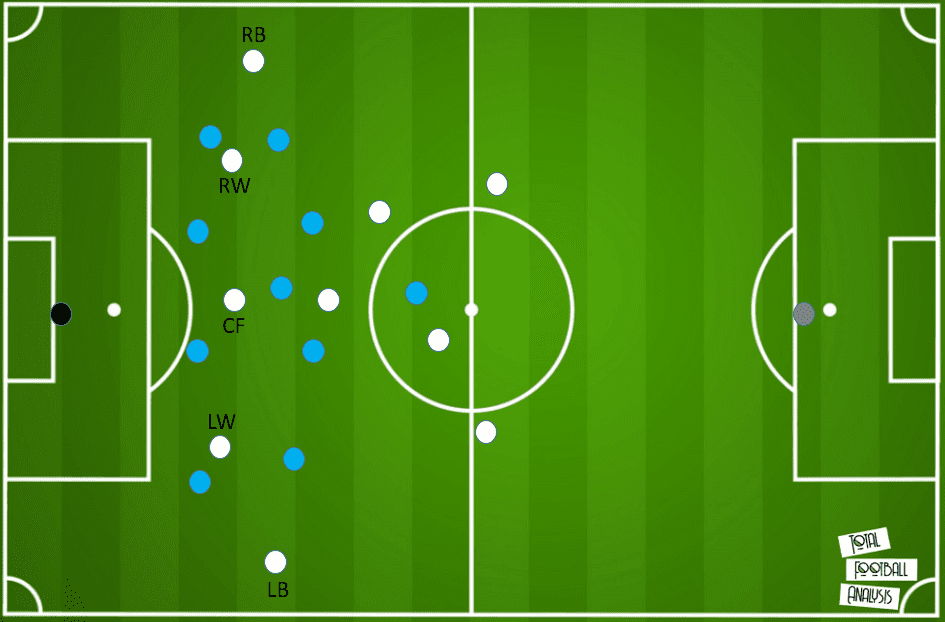

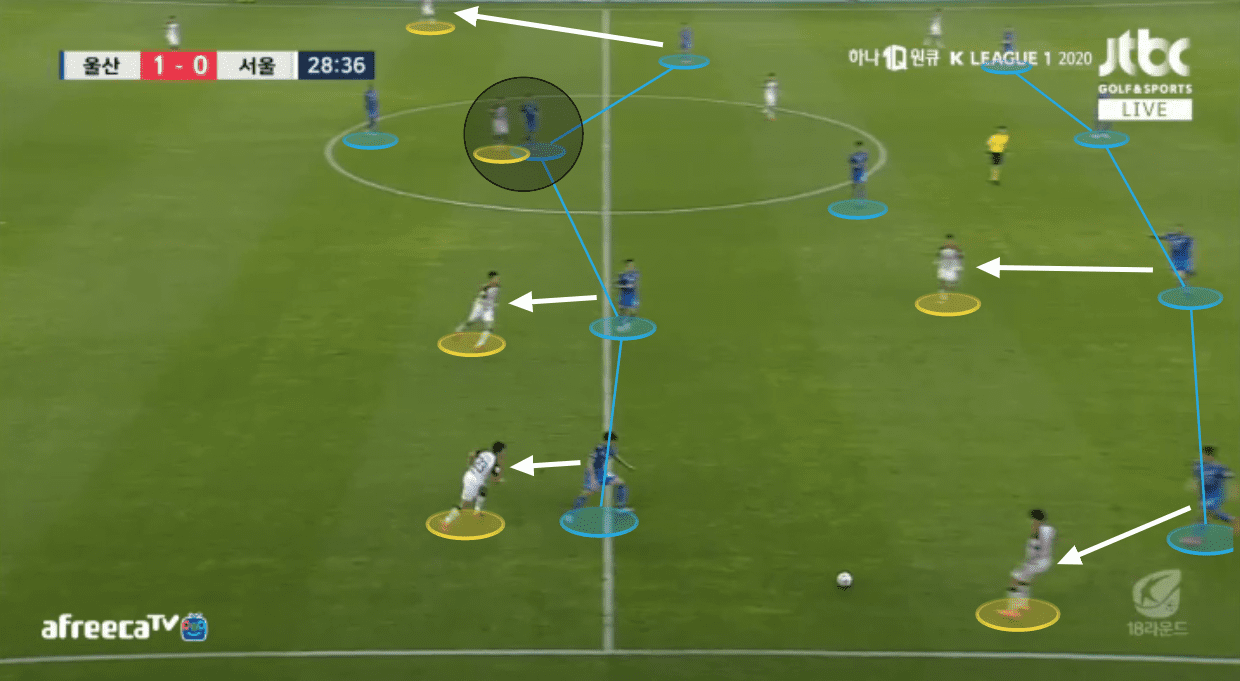

In these situations, the full-backs move up, the wingers invert themselves to the half-spaces. The approximate structure of both the teams during these situations is shown below.

However, Seoul could hardly create chances from these situations as they were always outnumbered inside the box. In this scenario, they were outnumbered five to three by the Ulsan Tigers.

This is the reason that the right-back and the left-back produced 12 crosses together and only three were accurate. Yun Jong-kyu (RB) attempted 9 crosses and three reached their target and Ko Kwang-Min (LB) did not find any success.

Seoul find a way

Especially after Ki Sung-yueng was brought on, Seoul started to create more chances. It was due to three reasons – Ki’s ability to play enormous diagonal balls, Seoul’s tweak in tactics, and Ulsan’s not-so-Ulsan way of defending in their own half.

The tweak in tactics that Kim Ho-young devised was overloading the right flank and creating a conundrum on the opposition’s mind.

As you can see in the above image, Han Seung-kyu (CAM) passes the ball to the dropping Yun Ju-tae (CF) and creates an overload on Bulthuis (LCB) as well as Park (LB). Park can’t move up and mark Yun Ju-tae because he has Yun Jong-kyu (RB) to cover. Bulthuis can’t move up to mark Yun Ju-tae as Go Yo-han has started his run past the defender. This situation could have easily led to an opener for Seoul if not for Kim’s (RCB) intervention at the crunch time.

Again, you see a similar situation in the image below.

Go has the ball and three forward players have created an overload on Bulthuis (LCB) and Park (LB). Bulthuis misjudges a pass and Go finds his teammate in a dangerous position.

Conclusion

The match was a cagey affair and the scoreline surely does not reflect the truth. Kim Ho-young clearly outplayed Kim Do-hoon with his tactics. The cage of Seoul did not let Ulsan build up at all and if Seoul had a bit of luck and proper touches inside the 18-yard-box, the result could have been different.

Even though Ulsan had 1.66 xG, it was mostly accumulated during the last 13 minutes of the match where Seoul went for all or nothing and the two set-piece goals. The set-piece goals were mainly down to Júnior Negrão’s ability to create space for himself. I will keep that analysis for another day. Without these incidents, the Horangi accumulated a mere 0.34 xG whereas Seoul accumulated 0.86 xG in this fixture.

The ‘Double-Dragon derby’ may not have lived up to its hype but Ulsan has plenty to celebrate and it looks like FC Seoul has a bright future under Kim Ho-young.

Comments