This match could have been decisive for La Liga. Barcelona needed a win to keep fighting for the title and maintain the four-point distance with first-qualified Real Madrid, but they had to overcome the most inform team in the league, fifth-placed Villarreal.

The team led by Quique Setién had some very interesting surprises in their tactics, and we will look to understand them in this tactical analysis. Villarreal didn’t expect these changes and when they tried to adapt it was too late and Barcelona were already winning notably.

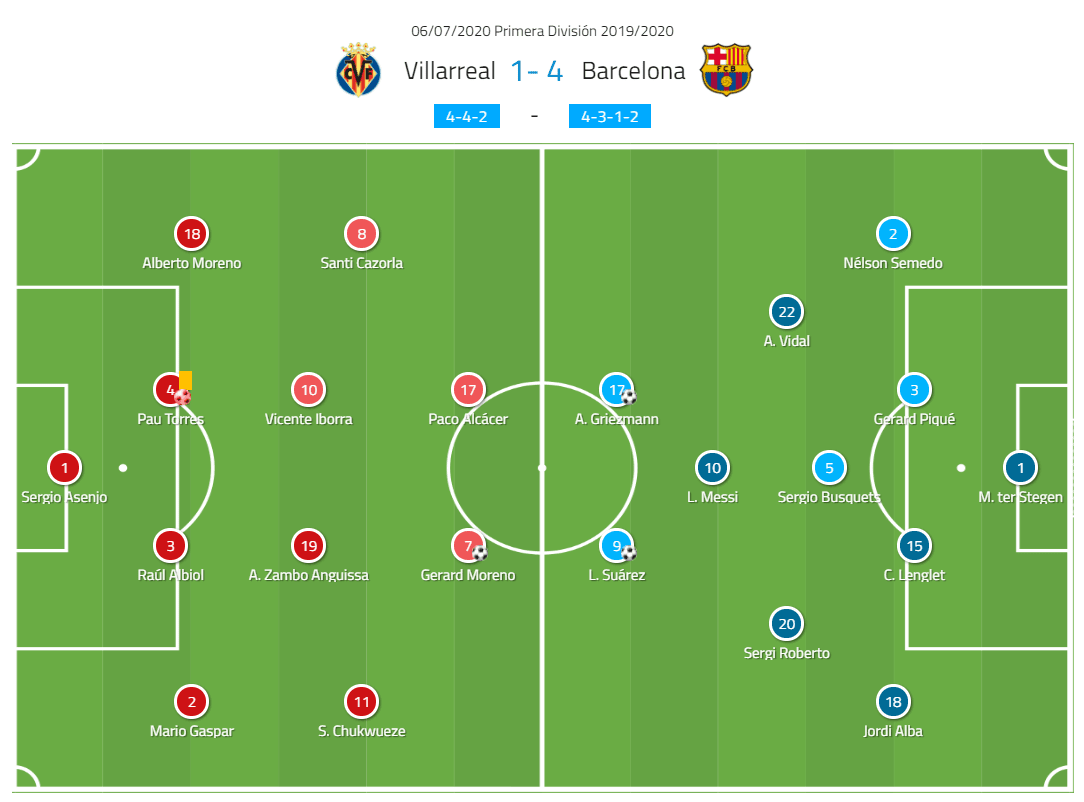

Lineups

Villarreal introduced five changes from their victory against Betis. Mario Gaspar substituted Rubén Peña on the right-back, providing a more defensive profile; in midfield, Iborra came in for Trigueros to add strength in defence and threat in set-pieces; and in attack Chukwueze and Cazorla acted on the wings instead of Ontiveros and Moi Gómez, while Paco Alcácer came in for Carlos Bacca up top. They used their typical 4-4-2 formation but chose more direct players to exploit Barcelona’s high defensive line.

Barcelona only made two changes to their starting lineup, with Antoine Griezmann coming in for Riqui Puig and Sergi Roberto playing in the place of Ivan Rakitic. However, the main change was in their tactics, as the front three acted very central, with Messi behind Griezmann and Suárez instead of using two wingers and a lone striker. In this analysis, we will see how this improved Barcelona’s attacks.

Barcelona’s new front three and Sergi Roberto’s position

Starting with the way Barcelona played out from the back, the main change was the position of Sergi Roberto in the build-up and how it affected the full-backs. During the build-up, both Roberto and Busquets came very deep, letting the full-backs act as wingers and provide width and depth. Busquets positioned himself right behind the first pressing line as usual, but Roberto took the left-back position, from where he could use his ability to run with the ball and free Alba.

Roberto’s new position allowed Barcelona to generate numerical advantages on the left side of their attack. If one of the Villarreal’s central midfielders followed him, a hole opened up in the central zone of the pitch and Barcelona could easily find their front three, especially Messi or Griezmann, when they stepped back. If it was Chukwueze who followed Roberto, then Barcelona looked to find Alba and drag Mario Gaspar out of position, creating a lot of space for the front three to play in. Let’s see three examples of how this worked.

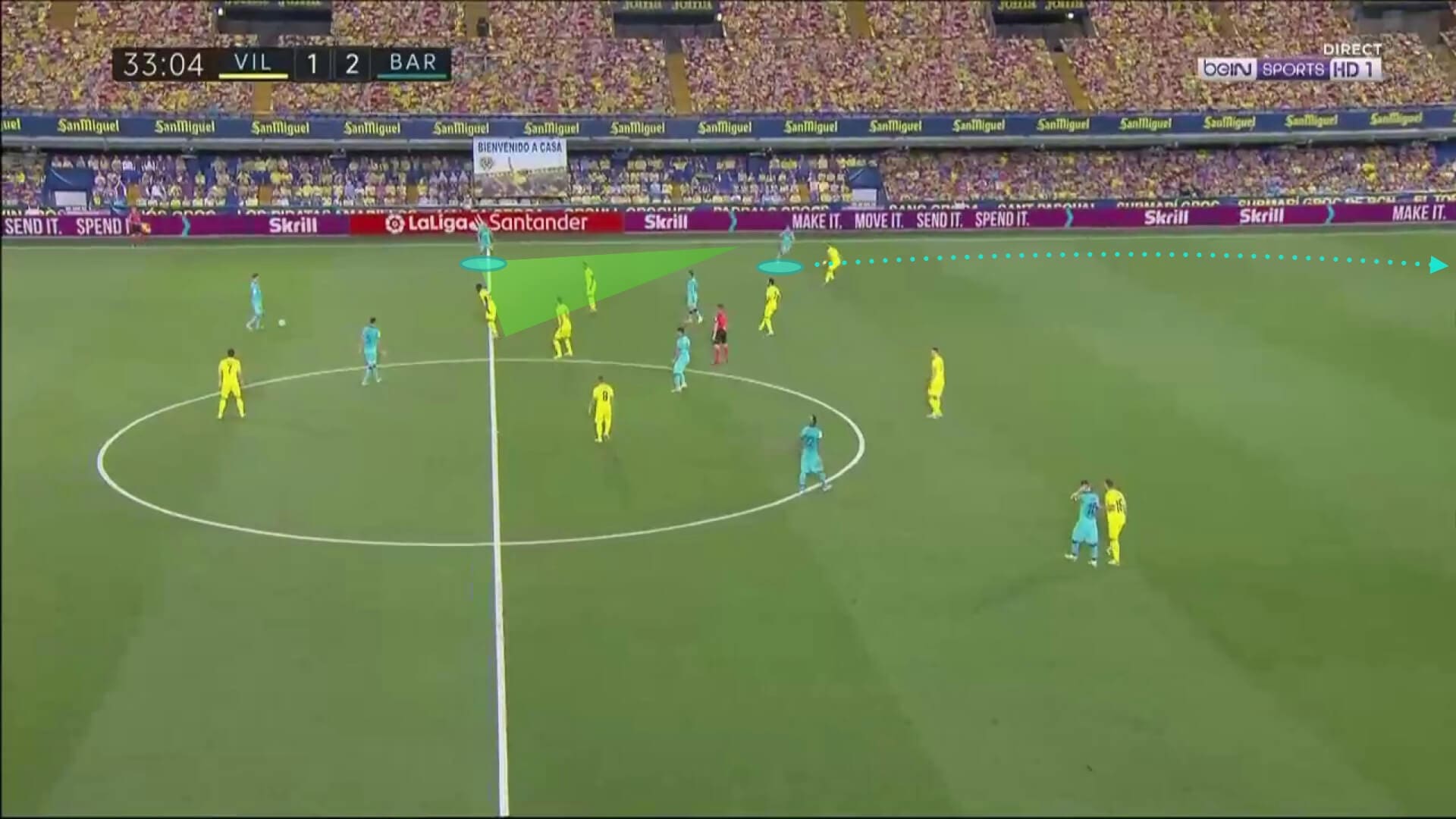

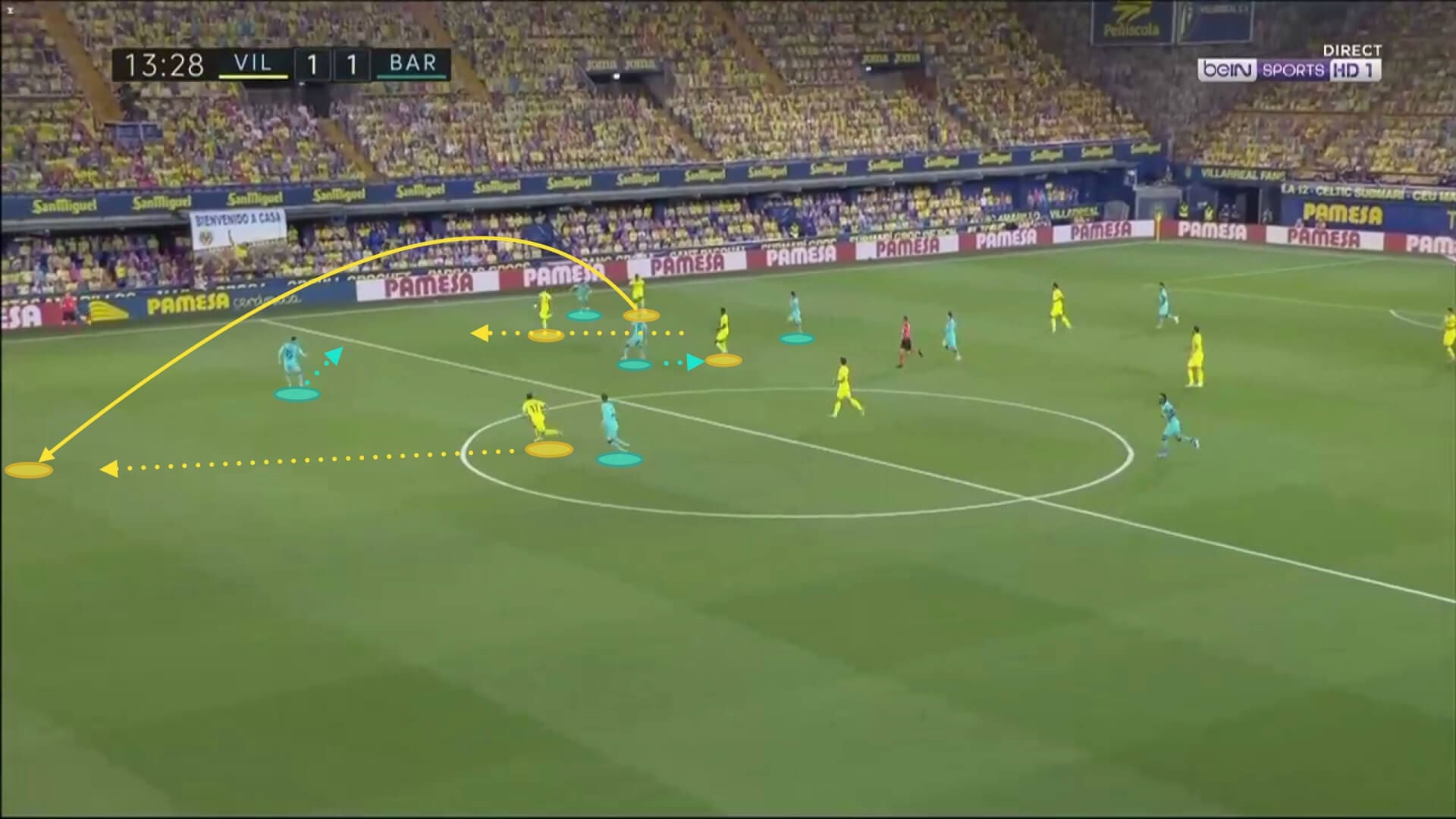

In the picture below we see the beginning of the play of the first goal. Sergi Roberto passes to Suárez and runs, receiving the ball back and forcing Villarreal’s right back to decide between pressing him or marking Alba. The right-back presses Roberto, who finds Alba’s run. Here, we can also see how Griezmann forces the left centre-back to stay with him, with Messi doing the same with the left central midfielder, so Roberto’s run forces Villarreal players out of position and leaves his teammates unmarked.

In the next example, Lenglet is on the ball and Alba provides width and depth with his run. Roberto occupies the left-back position and Alba’s run creates spaces for him to carry the ball forward. This positioning also helped Busquets get into higher positions and press when Barcelona lost the ball knowing Roberto was covering the defensive line.

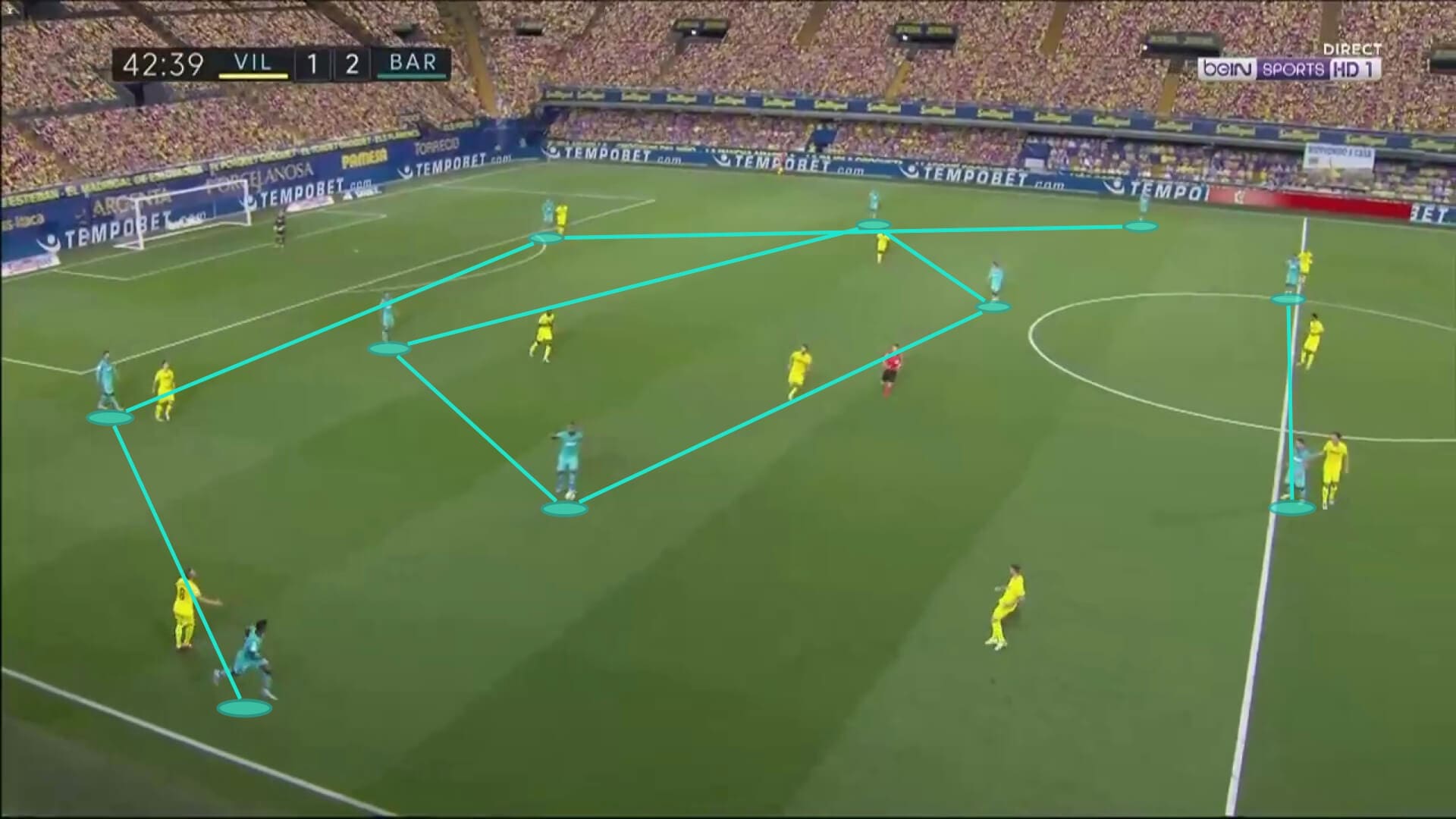

The last example of Barcelona’s setup when building from the back can be seen below. We see how Busquets approaches the centre-backs to offer a passing lane between the pressing strikers while Alba and Semedo push forward and are positioned higher up the pitch than the central midfielders, especially than Roberto who acts almost as the left-back. In this case, Griezmann occupies the attacking midfielder position behind Villarreal’s midfield with Messi and Suárez up top making sure the centre-backs can’t leave their position and press. We can also see how the team preferred to occupy the left flank, leaving more spaces on the right as Semedo and Vidal don’t have the ability to play in tighter spaces.

While the Messi-Suárez-Griezmann trio had been tried often before, Setién came up with a new way of using it, putting Messi in a more central, classical no.10 position with Suárez and Griezmann as the striker pairing. Suárez acted more as a target man with Griezmann as a second striker moving around him and participating a lot in the attacks.

The front three were very well coordinated. Every time one of them made a run in behind, another made a support run to receive between the lines while the one left made sure his marker couldn’t leave his position. This allowed the three of them to have a very good and comfortable match.

Below we see an example of this. Suárez comes deep to receive and hold the ball and Griezmann makes a run in behind to force the defensive line to move deep and create space for his teammates. Also, we see what we pointed out before as Roberto attracts players and creates the passing line and space for Suárez.

The new movements Barcelona made meant they didn’t need to rely on dribbling to advance. They had a lot of players in the central-left zone and Villarreal’s passiveness let them advance with quick combinations. Barcelona only attempted 18 dribbles, nine less than their last five matches average. Griezmann, who made 43 passes with a 100% accuracy and improving the attacks every time he touched the ball, was especially improved in his new role and was key when playing first-touch with Messi and Roberto, who were the ones who ran with the ball. The right side of Barcelona’s attack, Vidal and Semedo, had a grey match as they didn’t have to compensate Messi’s movements as much as in other matches and they lacked quality in their passing and dribbling so couldn’t create a lot and Barcelona didn’t look to find them in their attacks.

The new front three also helped Messi to be involved in the defensive phase. The Argentinian either marked one of the centre-backs, which didn’t require a lot of effort, or the defensive midfielder when he wasn’t moving. Griezmann was in charge of balancing Messi’s movements in defence, tracking back to follow the defensive midfielder when he moved forward or pressing the centre-back when Barcelona looked to press more aggressively. This resulted in Griezmann recovering six balls, only behind the centre-backs and Busquets in this aspect.

After scoring the 1-3, Barcelona chose to defend with the ball. This could be clearly seen in the reduction of their attacks per minute (see the chart below) without decreasing their possession, meaning they had longer attacks and didn’t let Villarreal react. Apart from the 67-33 possession, Barcelona had nine possessions of more than 45 seconds (Villarreal had two) and 22 between 20 and 45 seconds (Villarreal had nine). In total, Barcelona had 20 more minutes of pure possession time than Villarreal (38:39 vs 18:42) and more than doubled the average possession time (27 vs 13 seconds).

Villarreal’s lack of defensive intensity

Barcelona’s dominance was only interrupted when Villarreal could make direct and quick transitions. Their two strikers stayed up and they had a couple of two-against-two chances with Barcelona’s centre-backs. The attacking roles of the full-backs made it difficult for them to track back in time. Roberto offered cover when he stayed back, but his runs forward often left the defensive line too exposed.

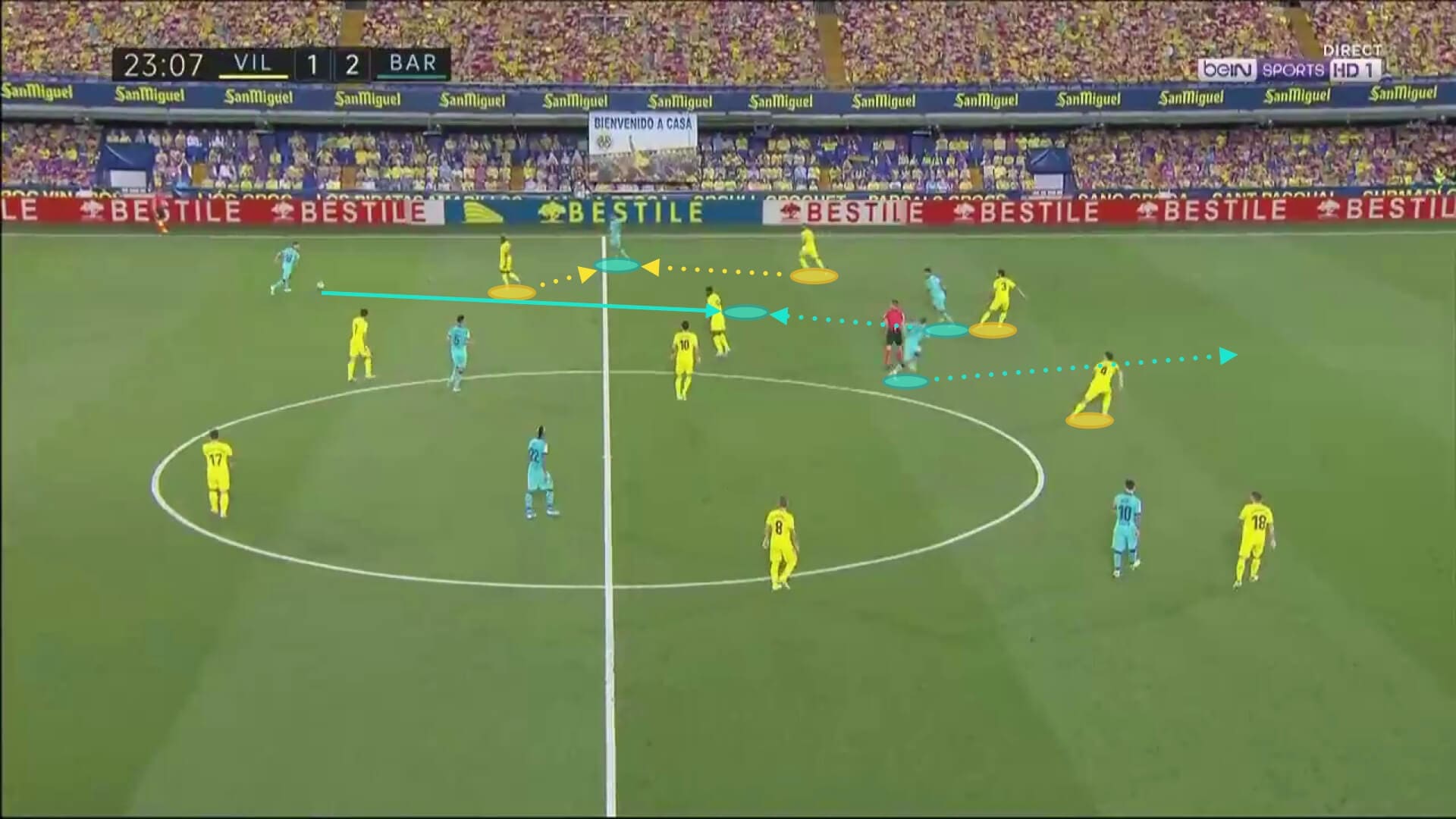

The next picture from the first goal’s play is a good example of this. We see how Villarreal recover the ball and quickly find Chukwueze on the right-wing. One of the central midfielders attacks the space behind Alba, forcing Lenglet to cover that side and opening the space for Alcácer’s run. Roberto is far from the defensive line and Busquets chooses to cover the easy pass, leaving the defensive line very exposed.

Apart from these quick transitions, which were limited in number, Villarreal struggled to create. They couldn’t recover the ball often enough and when they did they found themselves too far from the goal. Even when Villarreal covered well the spaces and were compact, they were very passive in defence and didn’t engage in duels, letting Barcelona play very comfortably and advance with quick combinations. Villarreals allowed 27.4 passes per defensive action showing how easy it was to play through their press, especially in the first half, when they allowed 50.2 passes per defensive action and didn’t oppose any resistance to Barcelona. As a comparison, Barcelona allowed 10.4 passes per defensive action and they didn’t even press hard.

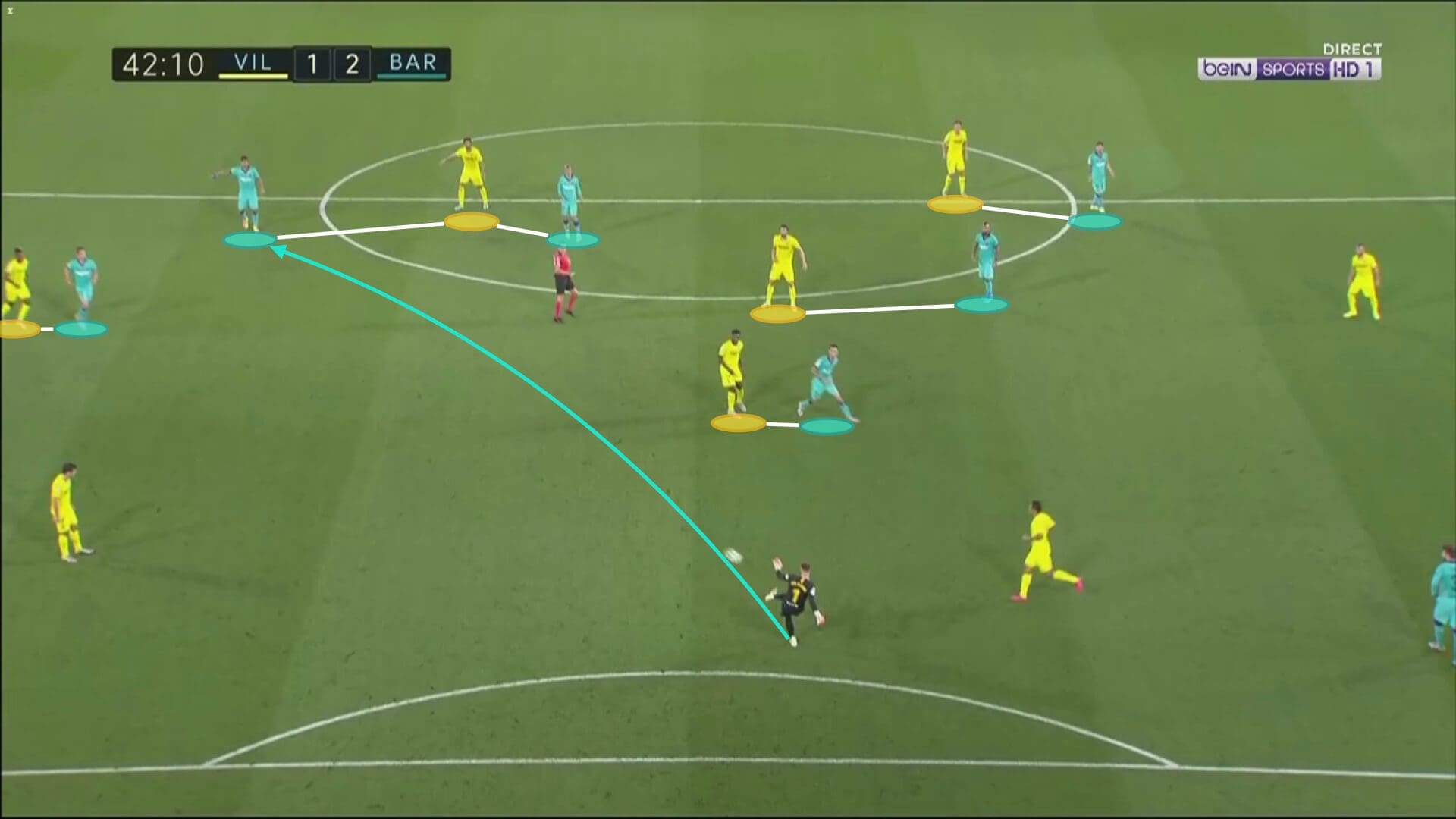

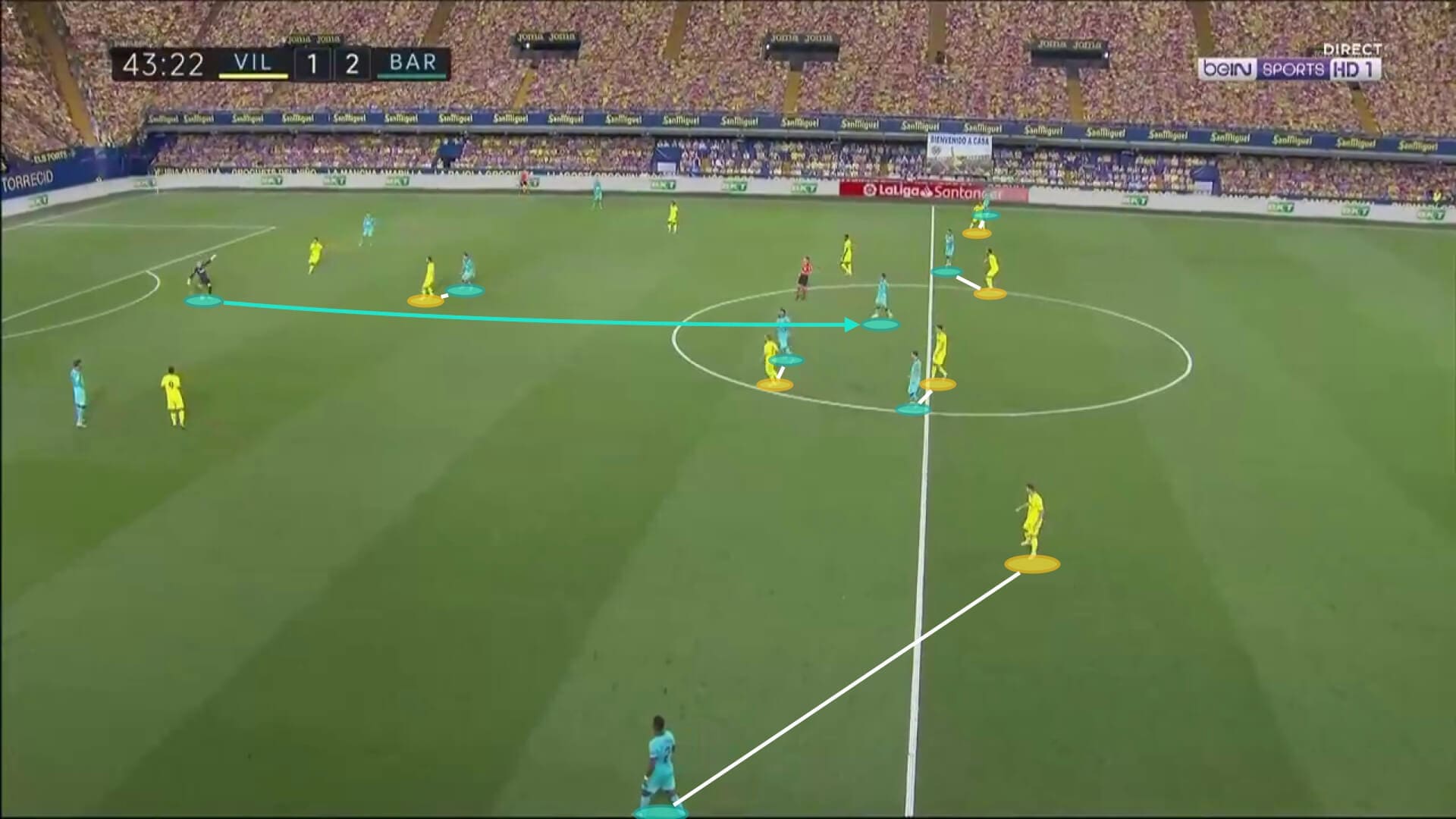

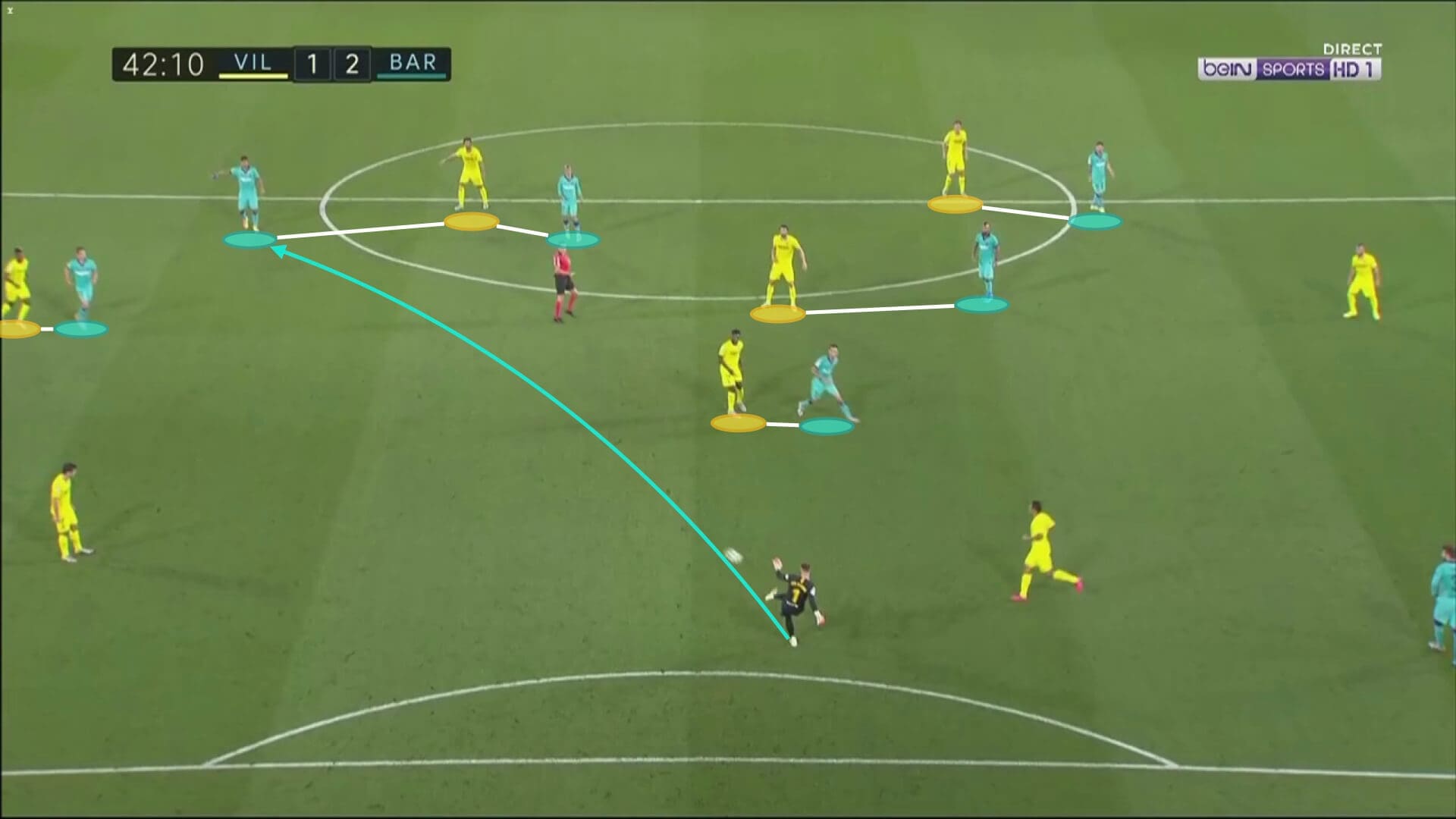

This lack of aggressivity when marking and pressing can be seen in the next two plays, both with Marc-André ter Stegen as the protagonist. Barcelona’s compact front three allowed one of them to be always free as the other two dragged the centre-backs, and Villarreal didn’t press intensely enough, allowing ter Stegen to break two lines with a relatively simple pass as we can see in the next two pictures.

Above, no one presses ter Stegen and Villarreal’s right centre-back, Albiol, can’t decide between marking Suárez or Griezmann, so the German goalkeeper can find Suárez, who turns and creates a dangerous attack. The rest of the Villarreal players are being dragged to create that advantage.

Again above, Suárez gets himself in the central position and no one follows him as Messi and Griezmann are pinning the centre-backs. Vidal pins the left central midfielder and ter Stegen takes advantage of Zambo Anguissa not marking the Uruguayan striker to play a good pass that breaks two lines again.

The role of the substitutes

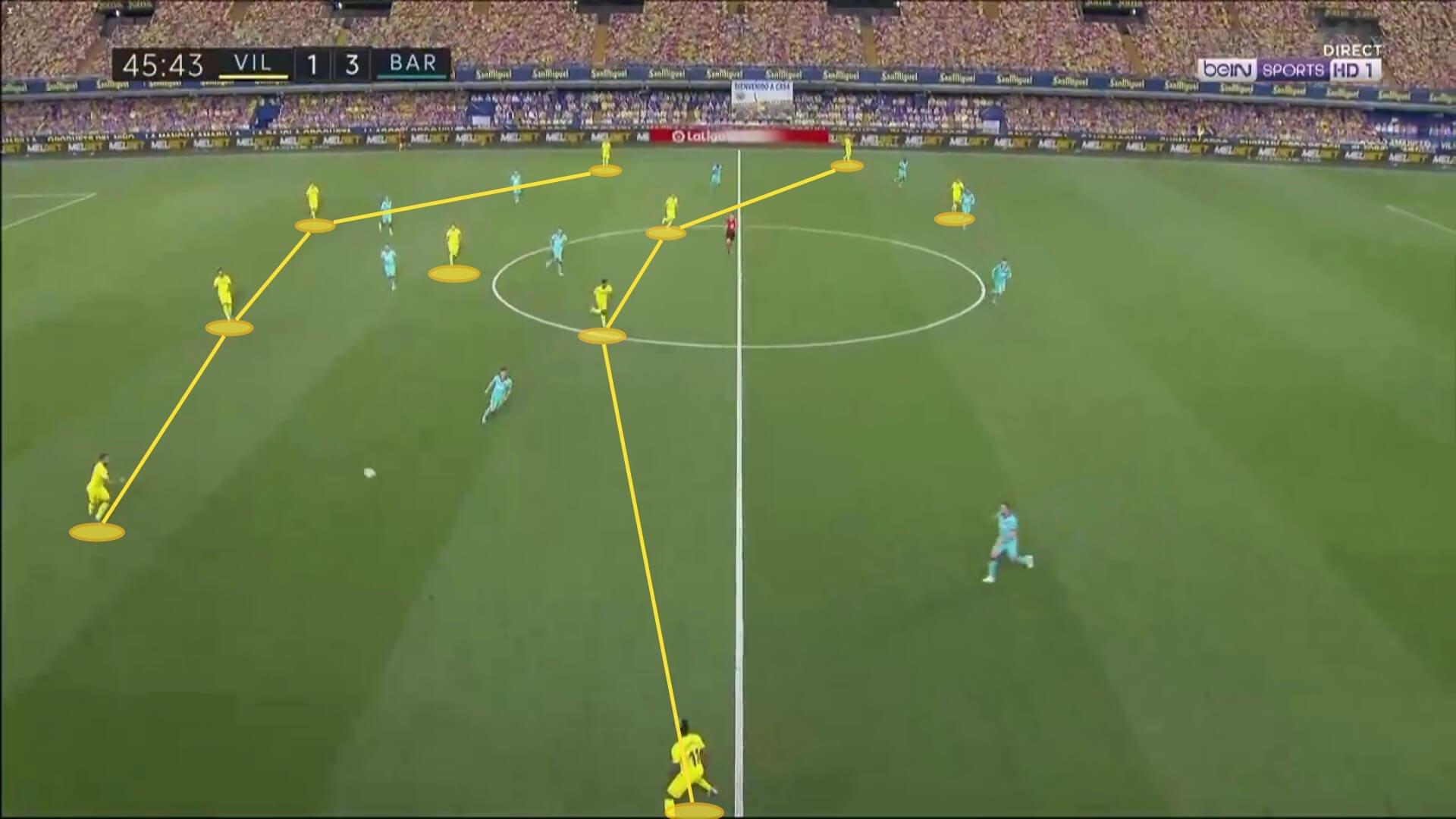

Seeing how they couldn’t grasp control of the game, Villarreal made a double change at halftime, with Iborra and Moreno leaving their places to Bruno Soriano and Moi Gómez. They changed their formation to a 4-1-4-1 with Soriano as the defensive midfielder and Gómez and Anguissa on his sides. They looked to control the ball and have more presence in midfield, and even if they improved their possession from the first half’s 29% to a 36%, they couldn’t control the game at all. We can see their new formation in the picture below.

These changes plus Trigueros coming in later made it more difficult for Barcelona to play between the lines, but they were still moving the ball from side to side comfortably as the didn’t need to risk the ball and used possession to defend.

On the other side, Barcelona’s first changes were Riqui Puig and Ivan Rakitic for Semedo and Suárez. This left Messi and Griezmann as the strikers, with Puig in the attacking midfielder role, Roberto as the right-back and Rakitic in Roberto’s position as the left central midfielder.

Barcelona improved their energy both with and without the ball. Puig isn’t a physical player, but he works hard when pressing and achieved four recoveries in half an hour. He also provided intensity in attack, making runs in behind and getting into the box, generating spaces for Messi to act as a playmaker. Rakitic, being less direct than Roberto, helped to control the ball, and Roberto as the right-back was a safer option when maintaining possession.

In the last 20 minutes, Barcelona returned to their normal 4-3-3 formation. Martin Braithwaite and Ansu Fati occupied the striker and left winger positions respectively, Rakitic moved to the defensive midfielder position with Puig and Vidal near him. This changes combined with some players being tired and the result being very good made Barcelona defend deeper. Messi isn’t as effective at pressing when playing from the right, and Fati and Braithwaite worked very hard to defend the wings but defended closer to the full-backs.

Zambo Anguissa often pressed Puig when he tried to receive long balls and he was physically dominant when there wasn’t space to turn and Puig had to shield the ball. Also, Barcelona looked to counterattack more and transition quickly, provoking more lost balls than before and balancing possession in the last 15 minutes (51-49 for Barcelona).

One of the most positive sides of the last 20 minutes were Fati’s movements. He was a constant threat with his runs in behind, showing an unmatched football IQ for his age. He knew how to drag the defenders out of position and then use his pace to attack the spaces he had generated, bringing lots of solutions to Barcelona in possession.

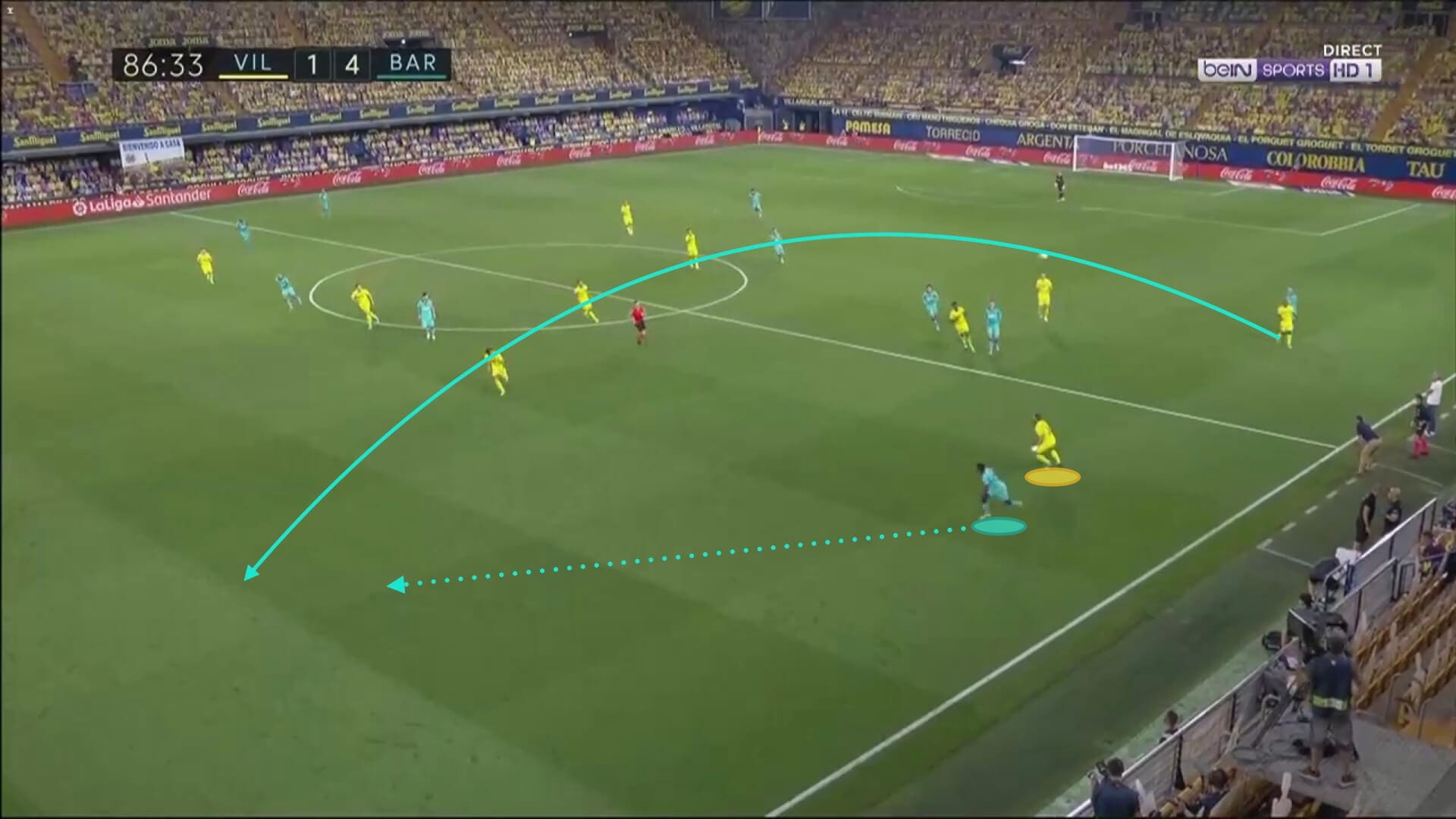

The run from his goal is a perfect example of how good his runs are. In the first picture below we see Fati running towards Alba, who is about to control the ball in the left-back position. Villarreal’s right-back, Mario Gaspar, runs with him thinking he may anticipate and cut the pass. But in the second picture, we see Fati’s real intentions. Once Gaspar is in front of him and ready to intercept a low pass, Fati starts a run in behind and receives a long ball over the defensive line, allowing him to run at Albiol and finish with a nice and unexpected shot.

Conclusion

It may be too late for Barcelona to win the league now, but their display against one of the most in-form teams in La Liga was enough to forget all the controversies that surrounded the club in the last few weeks. Griezmann performance was probably his best at Barcelona so far and Setién may have found the tactics to fight for the UEFA Champions League trophy in August.

Villarreal won’t be happy after the match. Their team was full of quality but never had controlled of the match and they lacked aggressiveness and intensity to stop Barcelona’s quick combinations. They still can reach Champions League positions, but being six points away from Sevilla with four matches left it seems like they will have to settle for Europa League and grow from there.

Comments