Among the new managerial appointments in La Liga this season were Pablo Machín and Manuel Pellegrini, who joined Alavés and Real Betis respectively. They clashed on the opening day but it was the visiting coach, Pellegrini, who would come out on top in a hardfought tie which looked set to finish goalless for much of the tie until Cristian Tello converted deep into injury time.

The former Barcelona man scored from the edge of the box after a quick corner caught out Alavés, who defended well throughout and actually had greater xG, 1.15 compared to 0.92. However, it was Real Betis, who twice hit the woodwork before scoring, who would take home the three points.

This tactical analysis will provide an in-depth analysis of the tactics of both teams in this La Liga clash. Without Real Madrid or Barcelona in action, this clash of two newly-appointed coaches provided an intriguing opportunity to consider the tactics of two sides bound to have plenty to say in the outcome of La Liga this season.

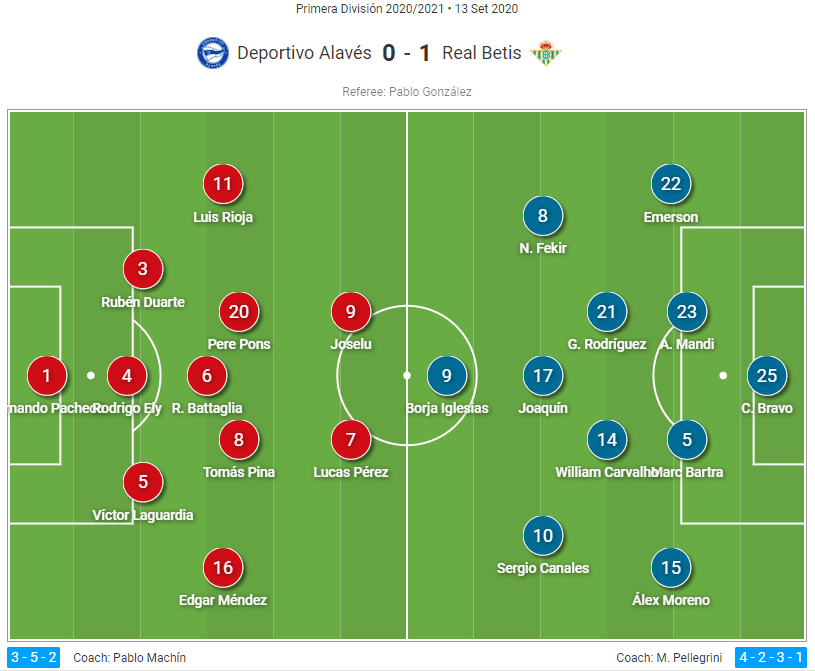

Line-ups

Alavés coach Machín stuck to his system of three central defenders. The only real changes from last season were the inclusion of debutant Rodrigo Battaglia in holding midfield and the return of Tomás Pina after injury.

Manuel Pellegrini took a similar approach, with the only change of personnel coming in the form of Claudio Bravo making his Betis debut in goal. Intriguingly, Joaquín was selected for the central attacking midfield role in a 4-2-3-1 shape.

Machín’s style with Alavés

At Girona, Sevilla and Espanyol, Machín has always stuck to his preferred tactical philosophy of a 3-5-2 shape and that has been deployed again at Alavés. There have been question marks over how effective it could be. Typically relying on marauding wide men, Alavés struggled defensively last season and did not possess great depth in central areas, but Machín has stuck to that approach throughout their pre-season campaign and it remained the same against Real Betis on the opening day of the season. The system was very similar to that which he used at all three of his previous clubs in Primera.

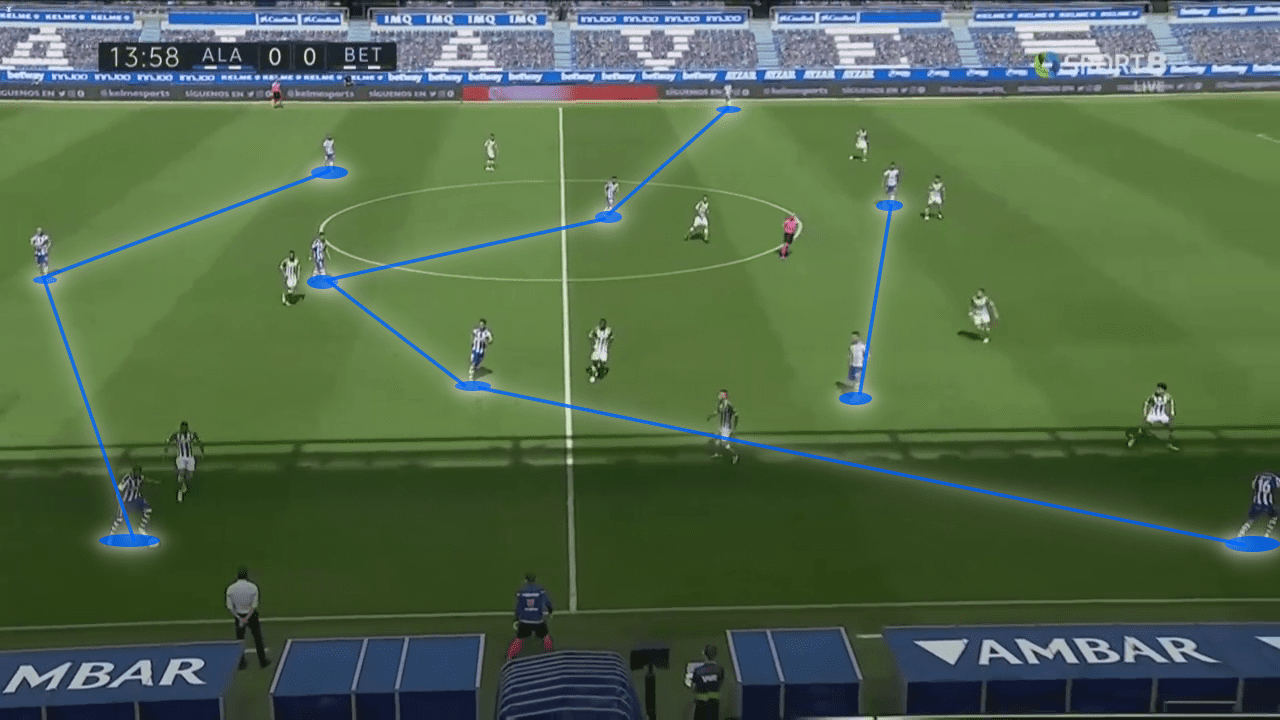

When in possession, Édgar Méndez on the right and Luis Rioja on the left both bombarded forward and would almost act more like forwards than wing-backs. Equally, the defensive three would spread very wide so as to stretch the game. Betis did not look to press particularly high, but by spreading so wide it was easy for Alavés to resist the press and progress play forward. With so much space on the flanks as the wing-backs pushed into attack, it created a well balanced threat which stretched the pitch against a Betis side full of centrally-focused attacking players.

With the Betis defence stretched, Lucas Pérez and Joselu took turns to drop deep, almost creating a diamond shape in the middle of the park with a three man attack ahead. This element proved crucial in order to provide a connection between the midfield and attack and to look to break up the midfield wall of William Carvalho.

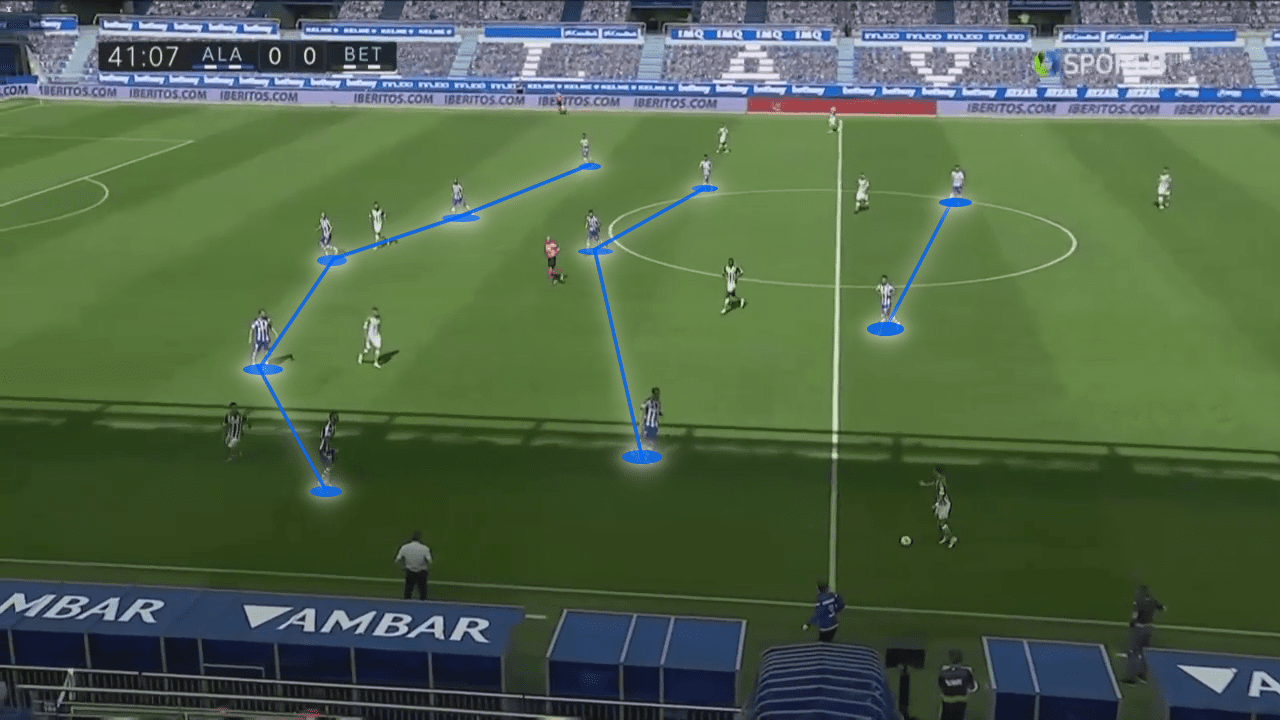

When out of possession, the system changed. Having such a wide central defensive three left Alavés very vulnerable on the counter attack and so they reacted quickly when possession was lost. Immediately, the back three become more narrow with the wing-backs dropping into deeper roles, more like full-backs. With both players substituted, the question will be asked of whether they will be able to sustain the fitness levels required to cover such distances.

Equally, the midfield did stretch out to cover. With one forward dropping off, the system would almost look more like a 5-4-1 shape. One midfielder could then drift wide to press the wide attack, which was the usual approach that Betis took. 21 of Betis’ 23 positional attacks, and all of their xG from such attacks, came from out wide as they simply failed to break down the congested central area.

How Betis looked to overload

Betis looked to the flanks, taking advantage of their inability to break down Alavés in central areas. Pellegrini selected wide players who were more centrally focused, such as Nabil Fekir and Sergio Canales, allowing them to drift into central areas. This left the flanks for Emerson and Álex Moreno to bomb forwards, with the Brazilian right-back the more effective option as he registered three crosses. The pace and direct style of these two full-backs looked to pin back the Alavés wing-backs by threatening them with a counter-attack as soon as possession was overturned by the Betis team, wherever it came on the pitch.

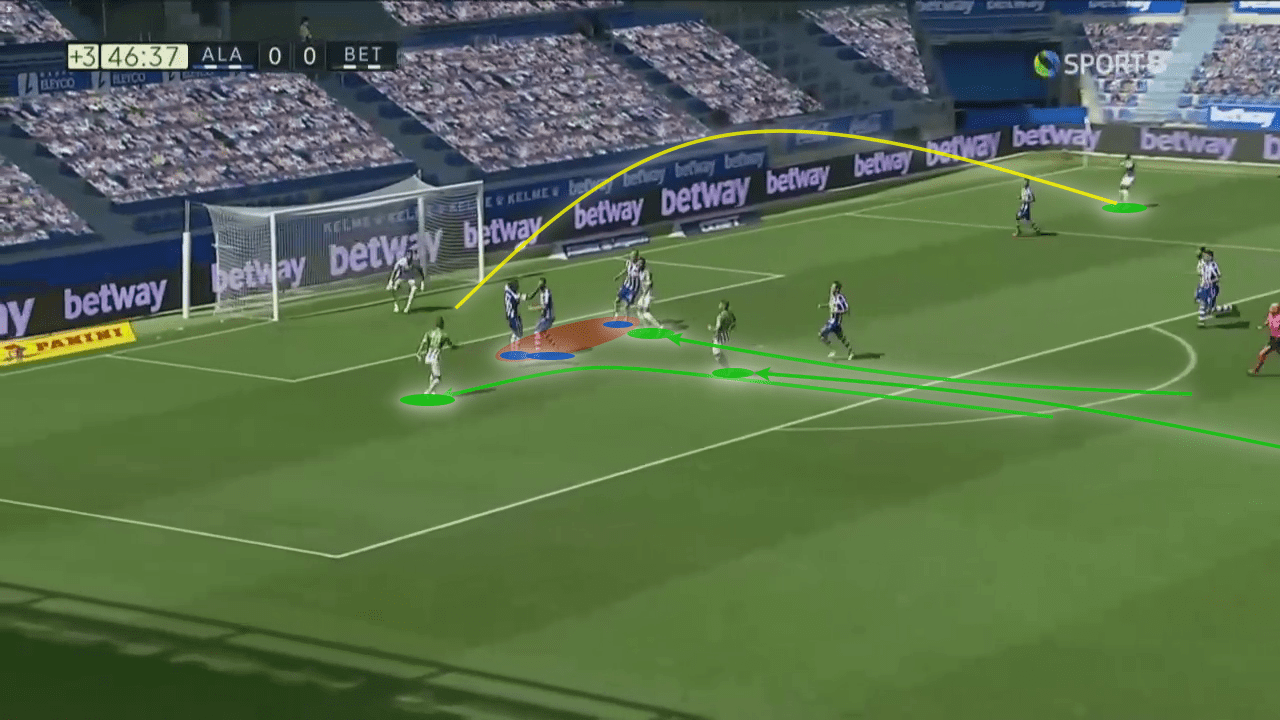

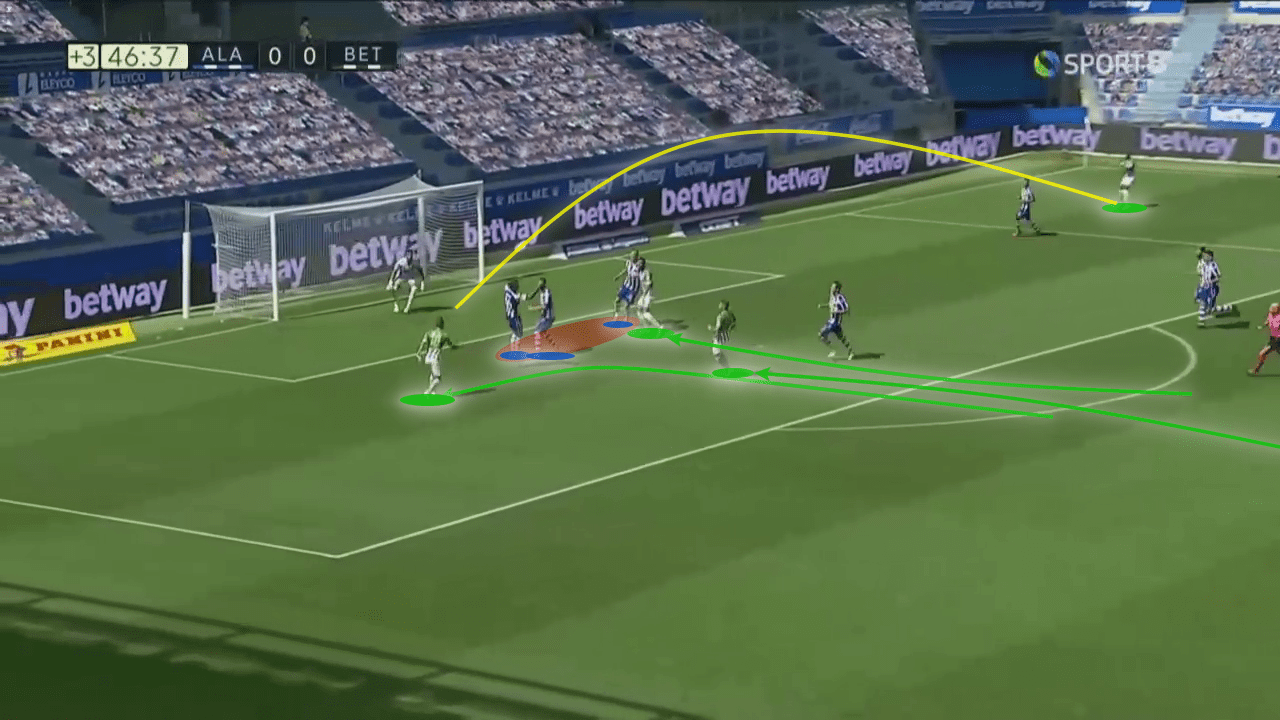

What was most intriguing here though was not the role of Emerson. Rather, it was the central runners. As can be seen here, the rapid counter-attack fuelled by Betis’ quickest players attacking from full-back areas, meant that the offensive players could look to overload the Alavés defence. With three against three, Betis could exploit Alavés faults with the system by focussing all on the surrounding Rodrigo Ely in the central defensive role. This created a panic which saw Alavés defenders failing to track their runners, instead being caught ball-watching by Emerson’s cross.

Betis exploited this well as one runner would then pull off at the far post. On several occasions, it appeared at first glance that Emerson’s cross was being overhit but the tactical approach was clear. Three runners into the box would attack the near post, distracting the three defenders, while one pulled off to the far post to find greater space. In this example, it was Canales who pulled off but could not convert from the cross. This threat was used throughout the tie and led to some of Betis’ greatest chances.

Finding space against a disciplined defence

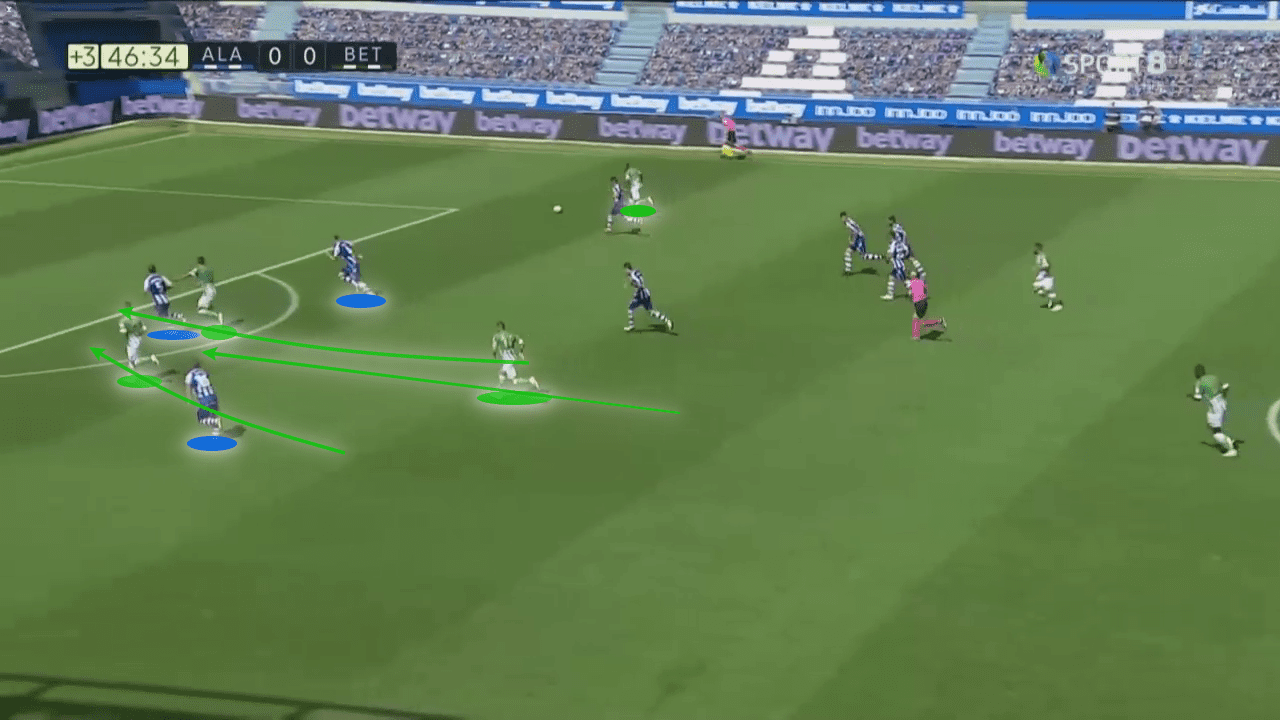

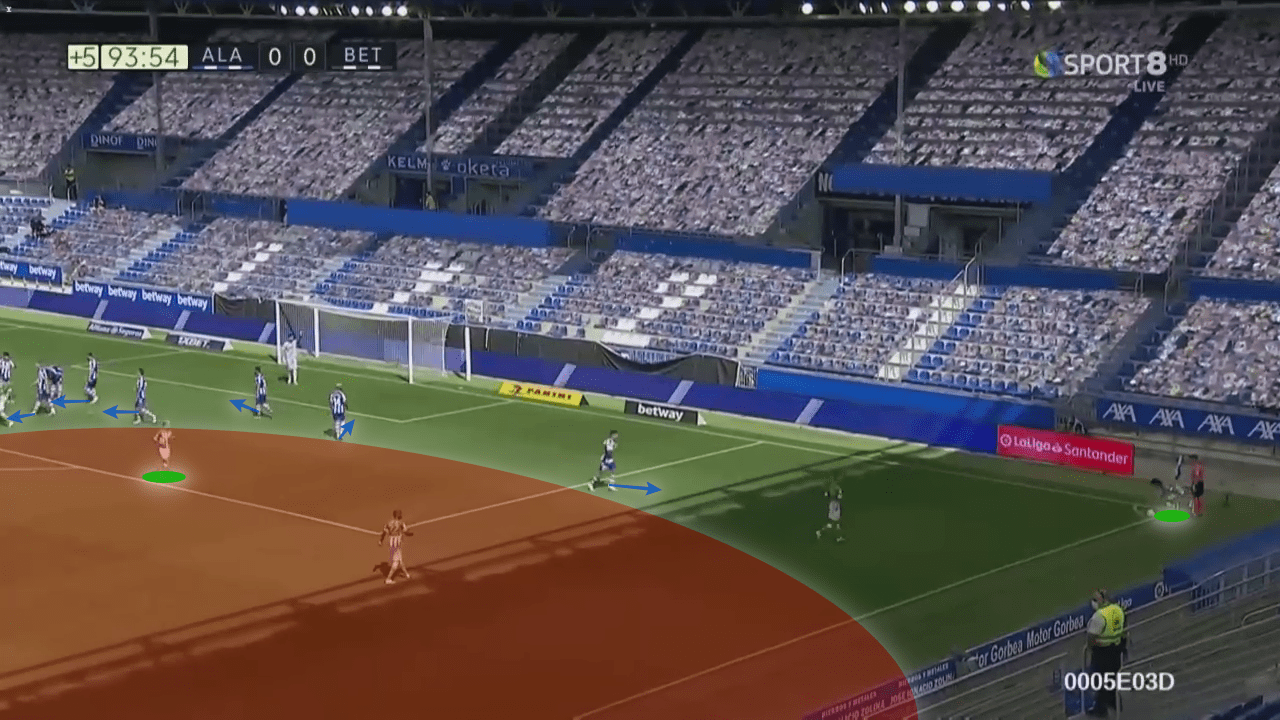

As has been addressed, Alavés did make life difficult for Betis. They struggled at times to find space and break them down, largely relying upon counter-attacks which allowed them to exploit spaces in their defence. However, the goal would come through a late slip in concentration in which Alavés let their guard down. Compared by Spanish commentators to the famous corner scored by Liverpool against Barcelona, Alavés’ defending was not quite as disastrous but was almost just as sloppy.

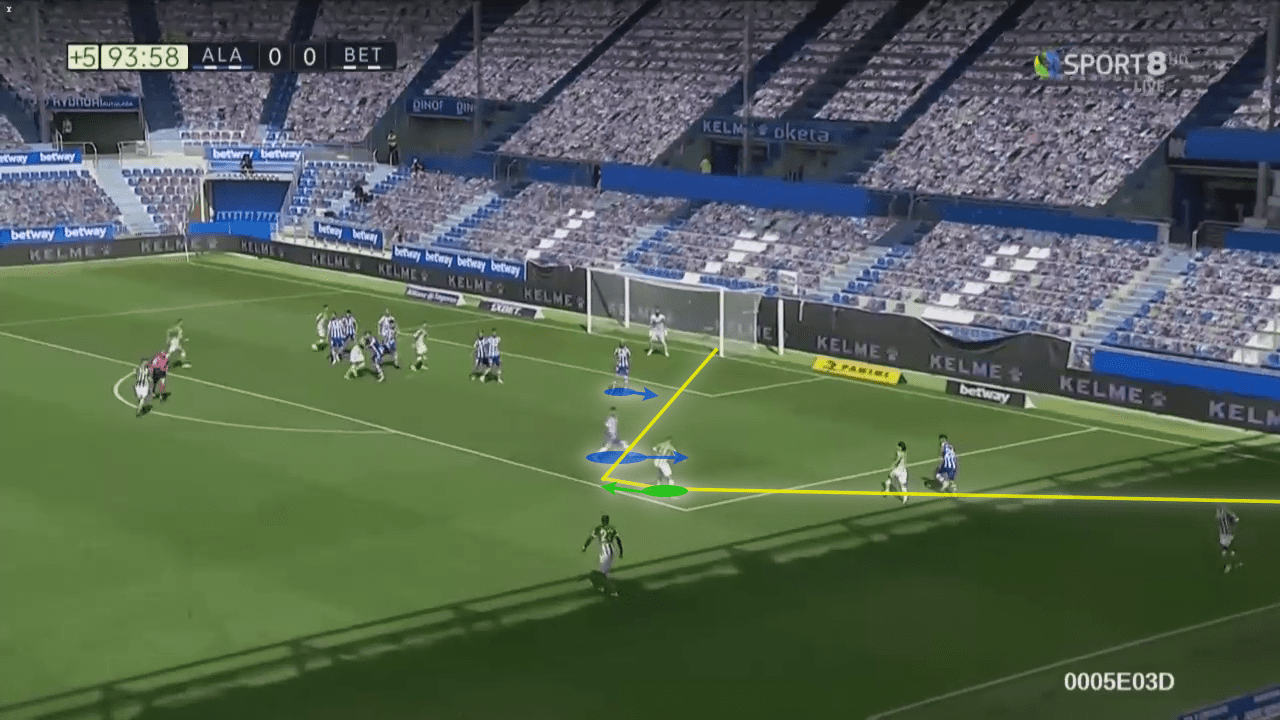

As the corner was prepared, Canales was smart to take the corner quickly with Tello dashing across into a wide-open area. Alavés defenders were not even looking at the ball, Fernando Pacheco being the only one paying attention. What was even more damaging was that Alavés defenders were almost all walking away from the ball, with their back to it. That meant that not only did Tello have the advantage of his pace in the run, but also gained a crucial few yards in reaction time once Alavés defenders were alerted to the threat.

This was quite so powerful as it meant that by the time Tello was on the ball, Alavés defenders were poorly positioned. They arrived steaming in, while Tello had the extra second to open his body up, take advantage of the gap and fire a pass into the bottom corner beyond Pacheco for a later winner.

Such an event will undoubtedly have infuriated Machín, who had drilled his team well up to that point. Such flaws were evident under the reign of Asier Garitano towards the second half of 2019/20 and Machín will be desperately hoping to stamp out such actions. Removing the experienced Méndez as a substitute for Martín Aguirregabiria only served to make the side more vulnerable, losing some of that defensive discipline in favour of a more offensive threat and fresh legs down the flanks to try to counter and threaten Betis. The gamble didn’t pay off, but Machín will know that such a lapse in focus cannot become a regular occurrence.

Conclusion

This tie will have shown promising signs for both coaches. While Betis were not spectacular, they were clinical in front of goal and despite having a low xG, threatened to score three or four goals. Improving on that, turning chances into goals and woodwork attempts into back of the net hits, will be the difference between mid-table mediocrity and European football for Pellegrini’s side. Their work rate and impressive focus late on showed just what an impact he has already had at the club.

For Machín and Alavés, the first 93 minutes proved a very impressive defensive outing. The concern for the coach, beyond lapses in concentration, will lie in that by bringing his forwards into a deeper role, limiting their freedom to spread out wide, he is limiting their potential. With a combined age of 62 in the front line of Pérez and Joselu, it is important that they get off to a strong start and are carefully managed to avoid burning them out with the work rate of dropping deep and leading the line.

Comments