The Derbi de la Comunitat was the first La Liga game of the past weekend, where Valencia hosted Villarreal at the Mestalla on Friday night. Despite playing in the UEFA Champions League last-16 in the 2019/20 season, the hosts have failed to reach those levels this season. However, they showed their fighting spirit in the derby to come back from behind and take all three points.

Villarreal had a nice start to the campaign, but the positives have faded as Unai Emery’s men have not won any league game since January. Even after Gerard Moreno scored a penalty in the first half to put them in the lead, they failed to gain any points after conceding two late goals.

Both teams played in a 4-4-2, and therefore it was interesting to see how their managers adapted their tactics to the quality of the players. In this tactical analysis, we will dissect their tactics, showing how they attacked in different ways while playing with the same formation.

Lineups

Former Watford manager Javi Gracia made a couple of changes to his Valencia side after the 3-0 loss to Getafe last time around. The centre-back partnership had to be changed since Mouctar Diakhaby was suspended, so Hugo Guillamón partnered Gabriel Paulista. Álex Blanco replaced Yunus Musah on the left flank, with the rest of the side unchanged from their last league game.

Villarreal’s starting lineup also saw just a couple of changes from their last league outing: Alfonso Pedraza was replaced by Pervis Estupiñán at left-back, while former Borussia Dortmund striker Paco Alcácer returned, with Manu Trigueros moving to the bench.

Parejo, Moreno & Villarreal’s attack

Villarreal had a higher xG than their opponents (2.47 – 2.33), but they struggled to convert their chances. Their attack lacked efficiency, and this is nothing new, with similar issues having been seen in their recent sluggish run of form.

This section will have an analysis of their offensive organization in the phases of possession. Their attack was heavily reliant on Dani Parejo’s ability to pass from deep and find the attackers in space if possible.

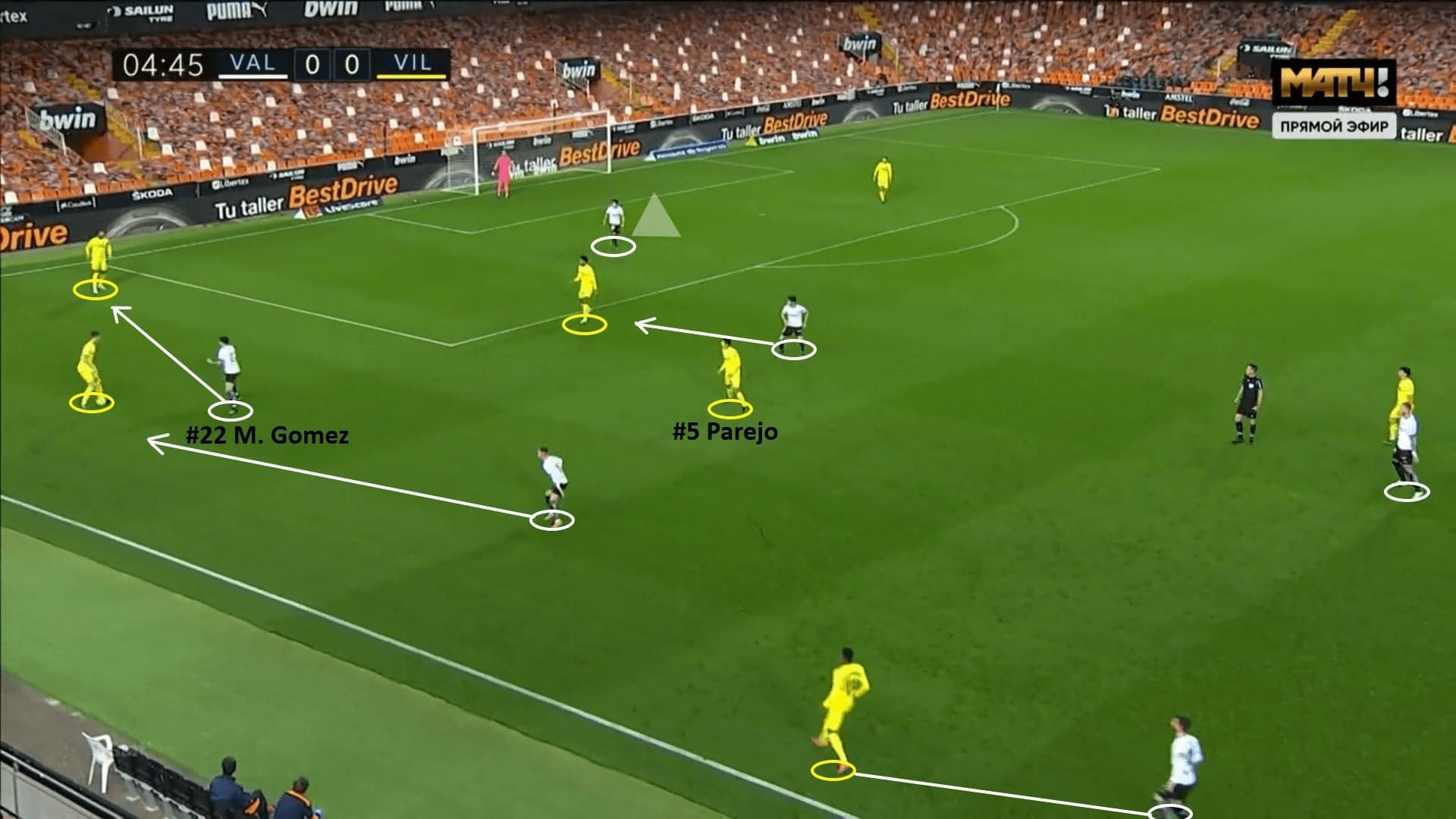

In the first phase, Villarreal’s main objective was to find Parejo as the free player to advance the ball. Comparatively, Étienne Capoue is less accomplished at passing and so he mainly focused on being a part of the rest defence.

When Valencia pressed high, they committed numbers to the ball side of the pitch. The first image shows this battle between the two teams. The hosts, in general, could have been more aggressive in attacking the ball and force it to be played where they wanted it. Maxi Gómez, in the image above, merely holds his position to wait for the right-back to pass to the centre-back, but that did not happen because Valencia were not applying sufficient pressure on the ball. Here, for example, the left-winger needed to push on to press the right-back in order to force the pass back to the centre-back.

Given that Kang-in Lee’s main job was to cut out the centre-backs as a passing option instead of defending the spaces, Capoue could absorb the pressure of the opposition midfield. The 2v1 overload at the centre resulted in freeing Parejo as the free player in the build-up. Valencia were unable to commit both midfielders to the press as Moreno dropped from the attacking line, so either Carlos Soler or Uroš Račić needed to stay deeper to mark him.

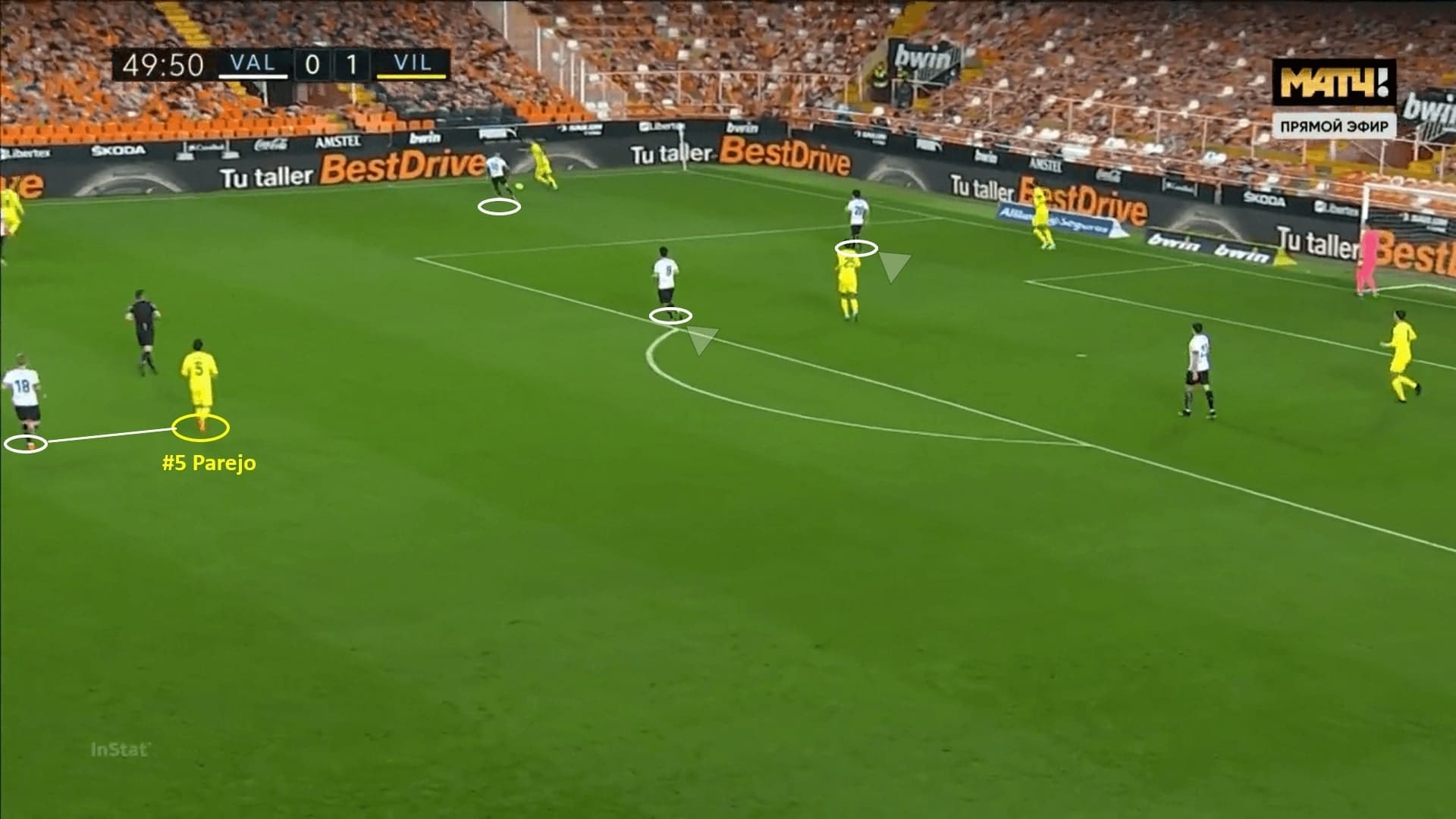

Valencia eventually tightened up their defence, trying to control both of the opposition pivots and preventing Parejo from receiving the ball. The second image was a case in which Villarreal failed to find the free player to play out from the back. The free player (Parejo) was difficult to find in this case – he was marked by Daniel Wass, while the other two players in front cut out a potential switch to the opposite flank. Their intensity was higher as they put more pressure on the ball, forcing the opposition to play quicker and thereby forcing more mistakes.

Valencia’s PPDA reached 2.6 in the second half, indicating the extremely intense press in this phase. Since they were able to win the ball back more often, they were also able to create more chances in the second half of the game.

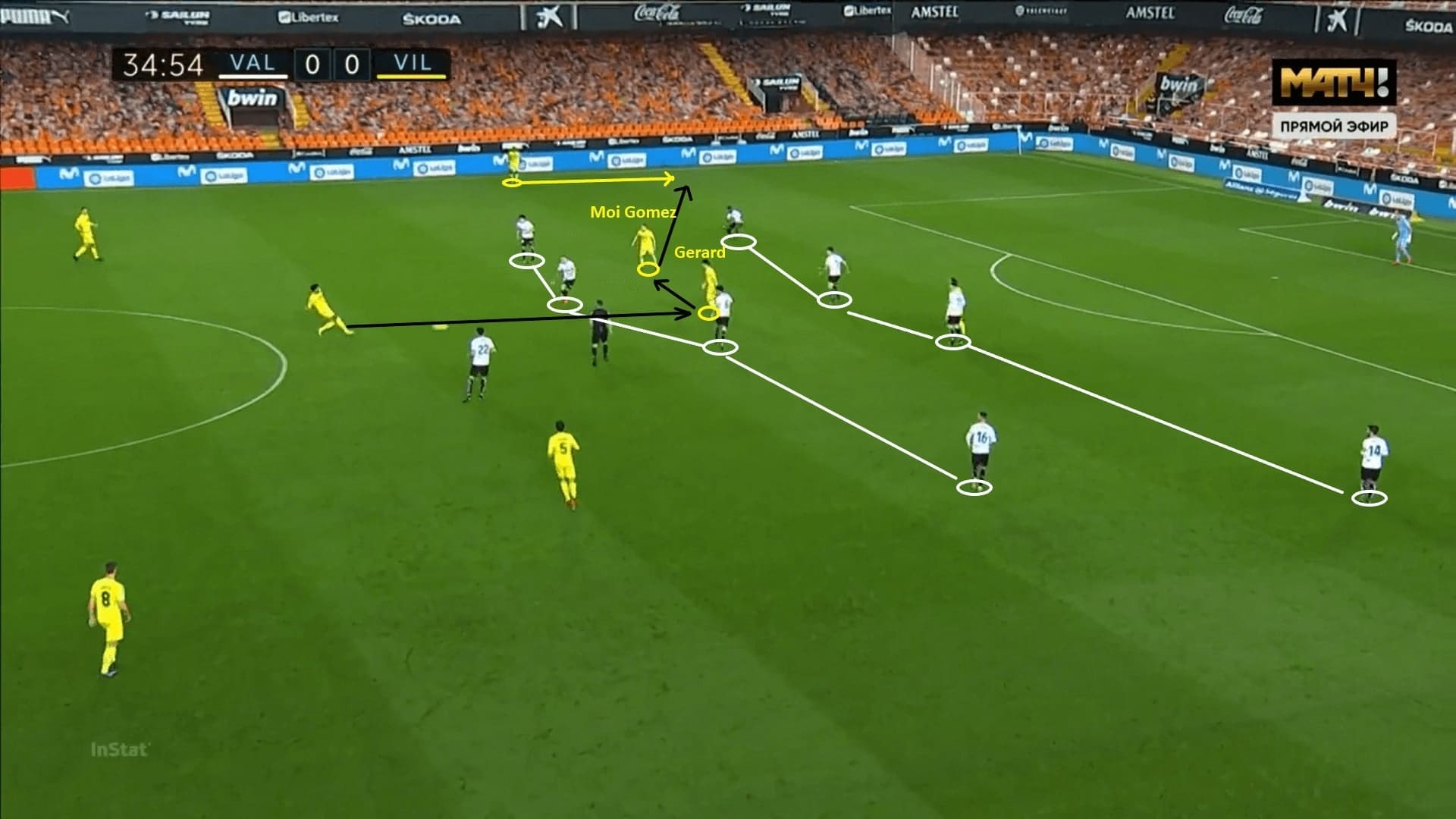

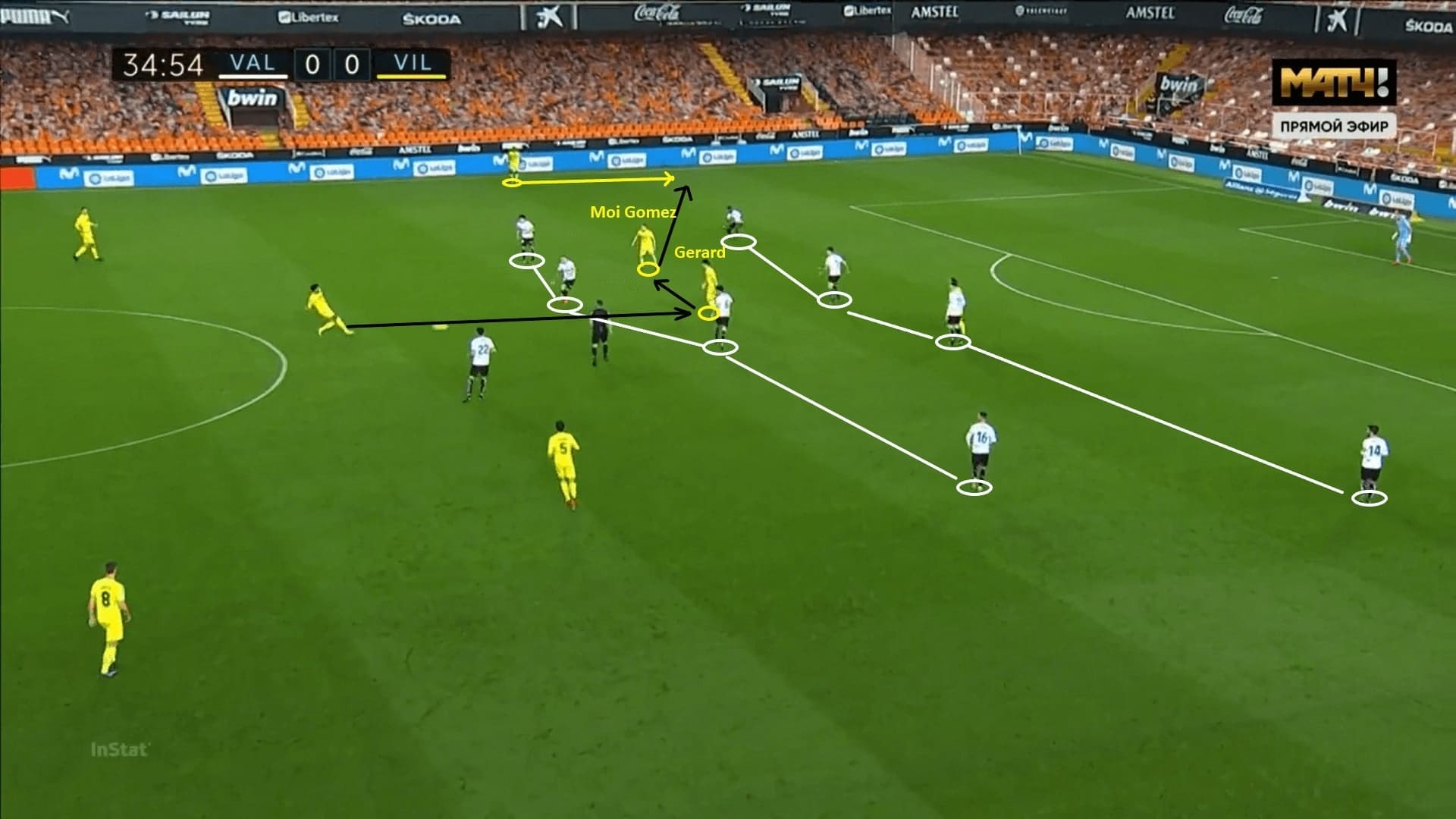

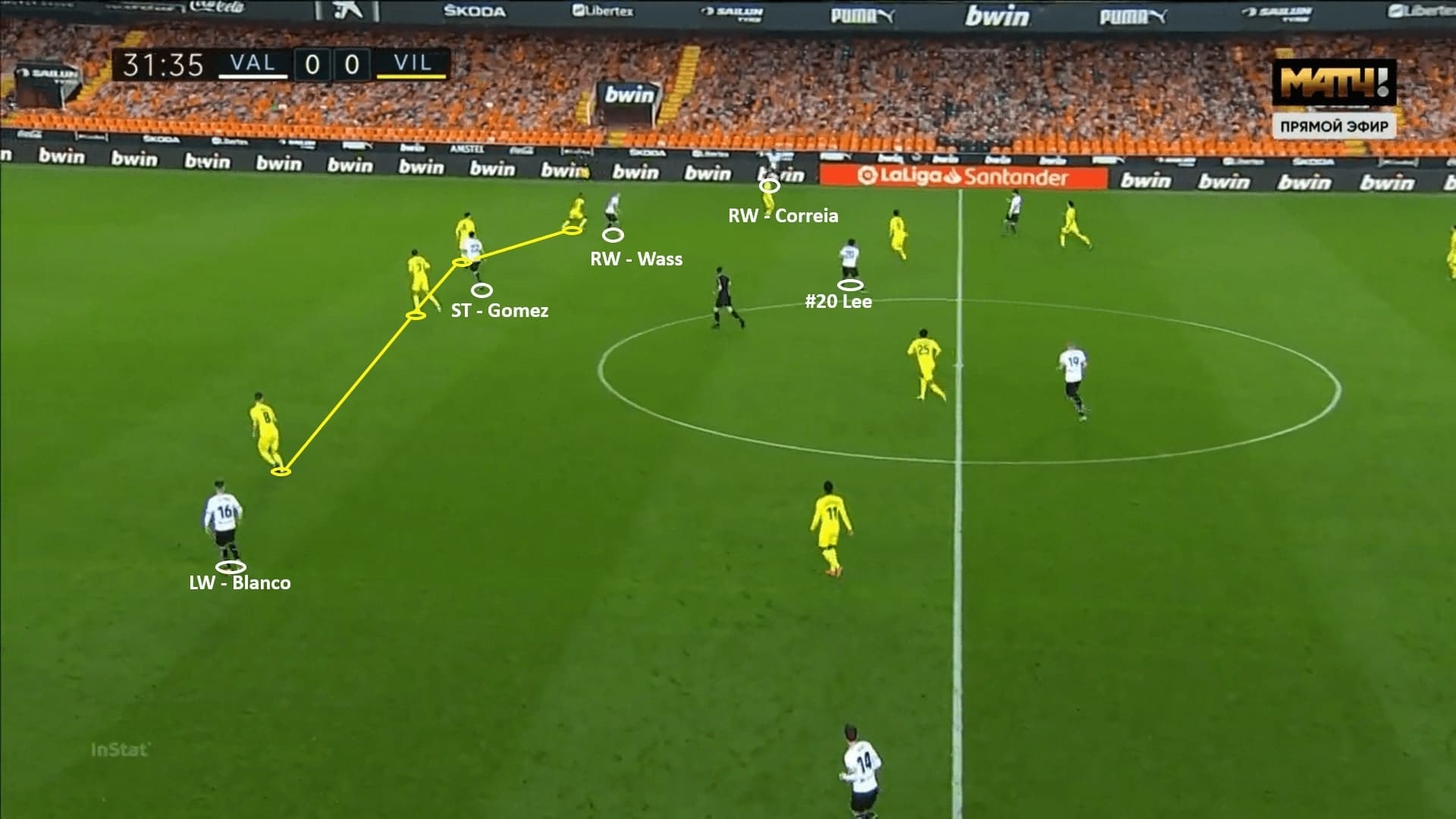

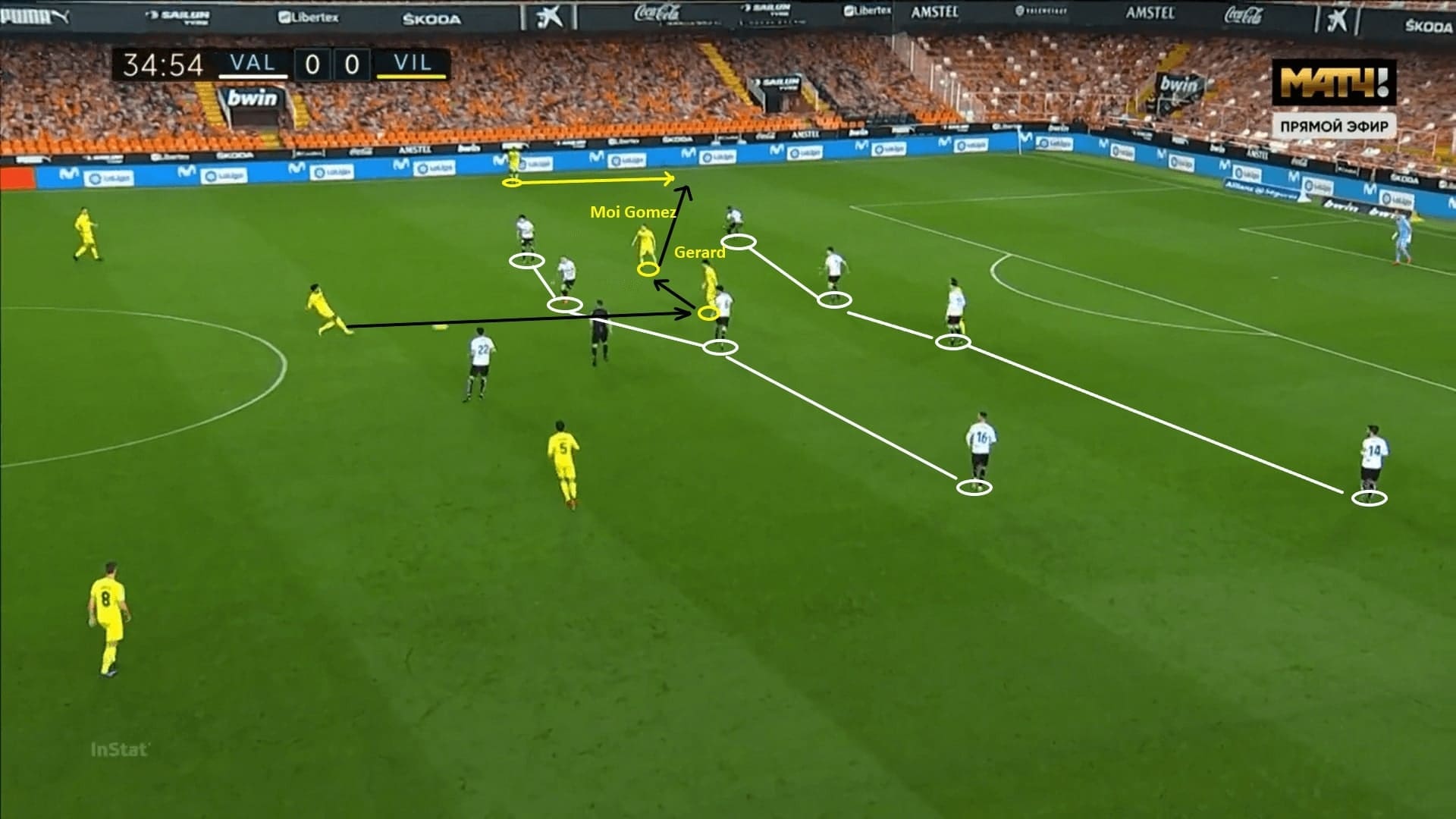

In their second phase of possession, they utilized the passing ability of Pau Torres and Parejo, and played more combinations on the left to advance the ball into the final third. They preferred to play with an outside-in pattern, first finding the left-back out wide, and then the narrow wingers making runs into the half-spaces to offer the next option ahead.

The above image shows how this tactic was performed. Since Valencia did not try limiting the angle of the pass, Torres easily found Estupiñán on the left. At the same time when the first pass was made, Moi Gómez made his run to get behind the defence. The Valencia right-back was forced to step up to Estupiñán, opening the space behind him.

However, this move did not have the same effect as Emery would have wanted. The left-back, Estupiñán did not play well enough when given space to attack out wide.

If Villarreal were playing through the centre, going into spaces between the lines, they would try finding Moreno. The Spanish international was good at roaming in the final third and moving into space to receive the ball. He was also good at making quick decisions to link the play.

The image above shows Parejo’s verticality, with the former Real Madrid player showing his ability to play progressive passes. Villarreal kept the wingers narrow at the centre to create an overload. Also, the tightened distancing of players was conducive to the interconnectedness, allowing quick combinations and the third-man plays as we indicated above. This usually drew the right-back narrow, opening the wide spaces for the left-back.

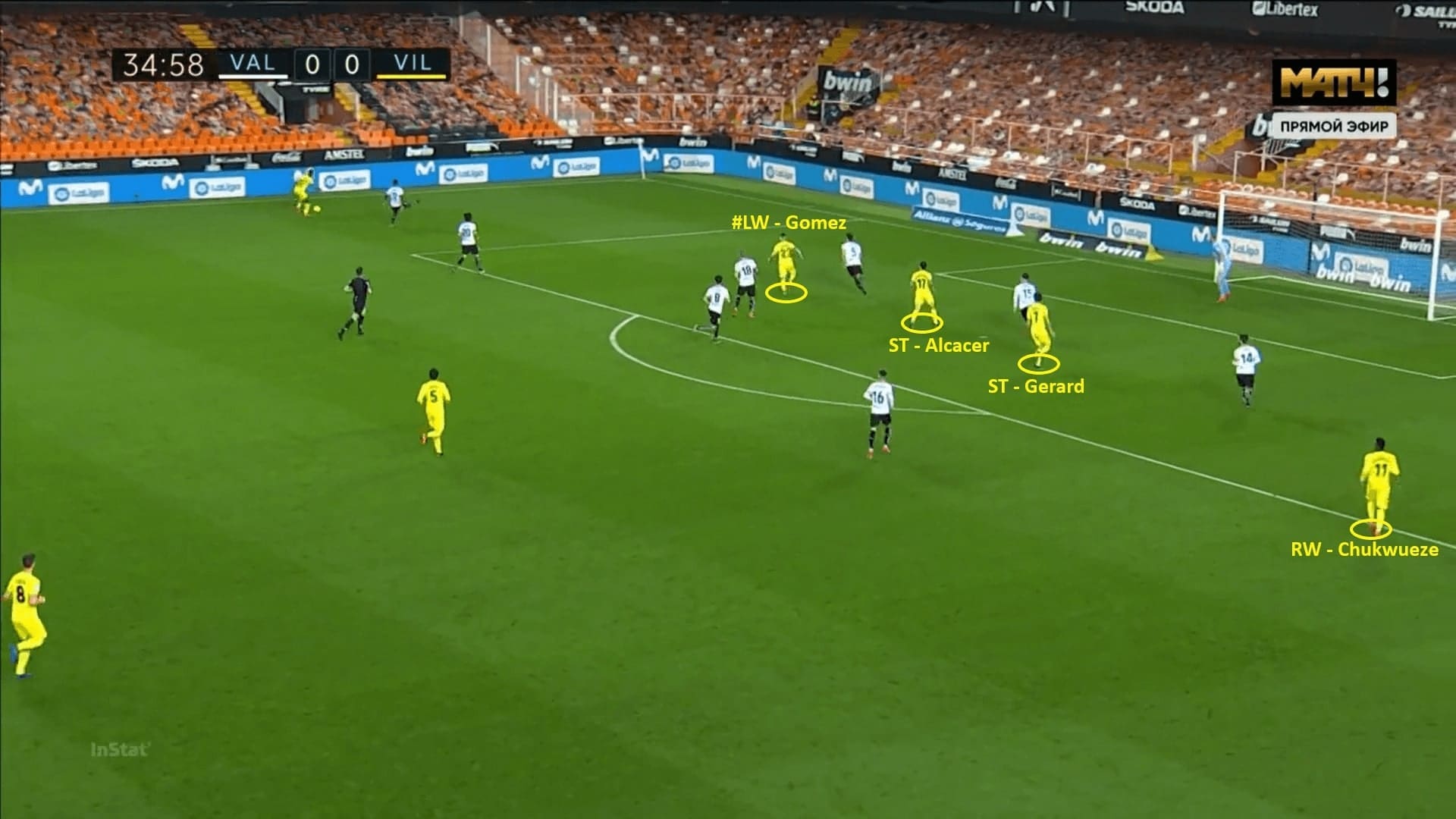

The last screenshot shows the way Villarreal attacked the box. Benefiting from the full-backs who attacked out wide, the wingers and strikers could enter the penalty area early. The idea was to evenly distribute to attack as many vertical channels as possible, for example, the front three spread evenly in the example. This would force the defence to split horizontally, creating numerous 1v1 situations, as well as enlarging the gap between each defender. The offensive side could attack the cross with flexibility, going for space or the weaker player.

This was the scenario before the penalty kick. Gerard did not have physical superiority in those situations. It would be difficult to head the ball if everyone crowded around the penalty spot. With this diverse distribution of offensive positionings, the chance for Gerard to contact the ball increased as he only dealt with one defender in large spaces.

Horizontal overload of Valencia & Gayà

Valencia were also attacking with a 4-4-2 but they played differently as Villarreal did. They did not have a player like Parejo at the midfield, who could play good passes to advance the ball. Their striker – Maxi Gómez was a more aggressive striker to get into duels and spaces behind, instead of roaming like Gerard.

Instead, the key player of Valencia’s offensive tactics has been the skipper – José Gayà. The left-back has been famous for his energetic and aggressive approach, ability to travel up and down at the wide zone. Also, he has a good sense to attack the goal and good at providing the crosses.

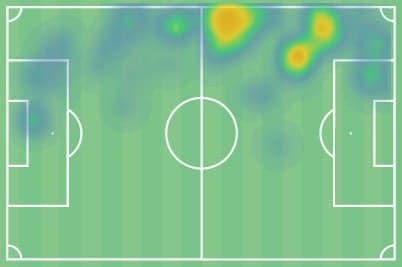

The above heat map shows Gayà’s involvement throughout the game. Unsurprisingly, he was more active in the opposition half than in his own half. It was clear that he was not a part in the build-up. Instead, Gracia wanted him to join participate in the second and third phase more, so he often made some early movements.

Apart from attacking from the touchline, Gayà also entered the penalty box, registering shots and crosses.

Combining with Gayà’s involvement in the attack, the offensive structure of Valencia was completed. Although playing as the striker of a 4-4-2 on paper, Lee was more like an offensive midfielder, dropping deep to connect plays in the game.

So, rarely did Lee stayed in the same horizontal zone as Maxi Gómez. Instead, the wingers were closer to the Uruguayan striker. They provided the offensive heights, more importantly, trying to stretch the defensive line. Therefore, usually, one winger (Wass above) would go narrowly at the relative half-spaces channel, while the other one (Blanco above) stayed outside of the line. With this structure, Valencia could always take the initiative according to the oppositions’ behaviours. If the defence stayed narrowly, then, spaces were available outside. On the contrary, if they split to gain access to each attacking player, Valencia could exploit the 1v1s or trying interfaces pass.

The centre-backs of Villarreal were not competent in defending spaces in front, hence, this has given the opponent some rooms to develop the attack. Los murciélagos had some efforts at the edge of the box because the defenders were slow to close them.

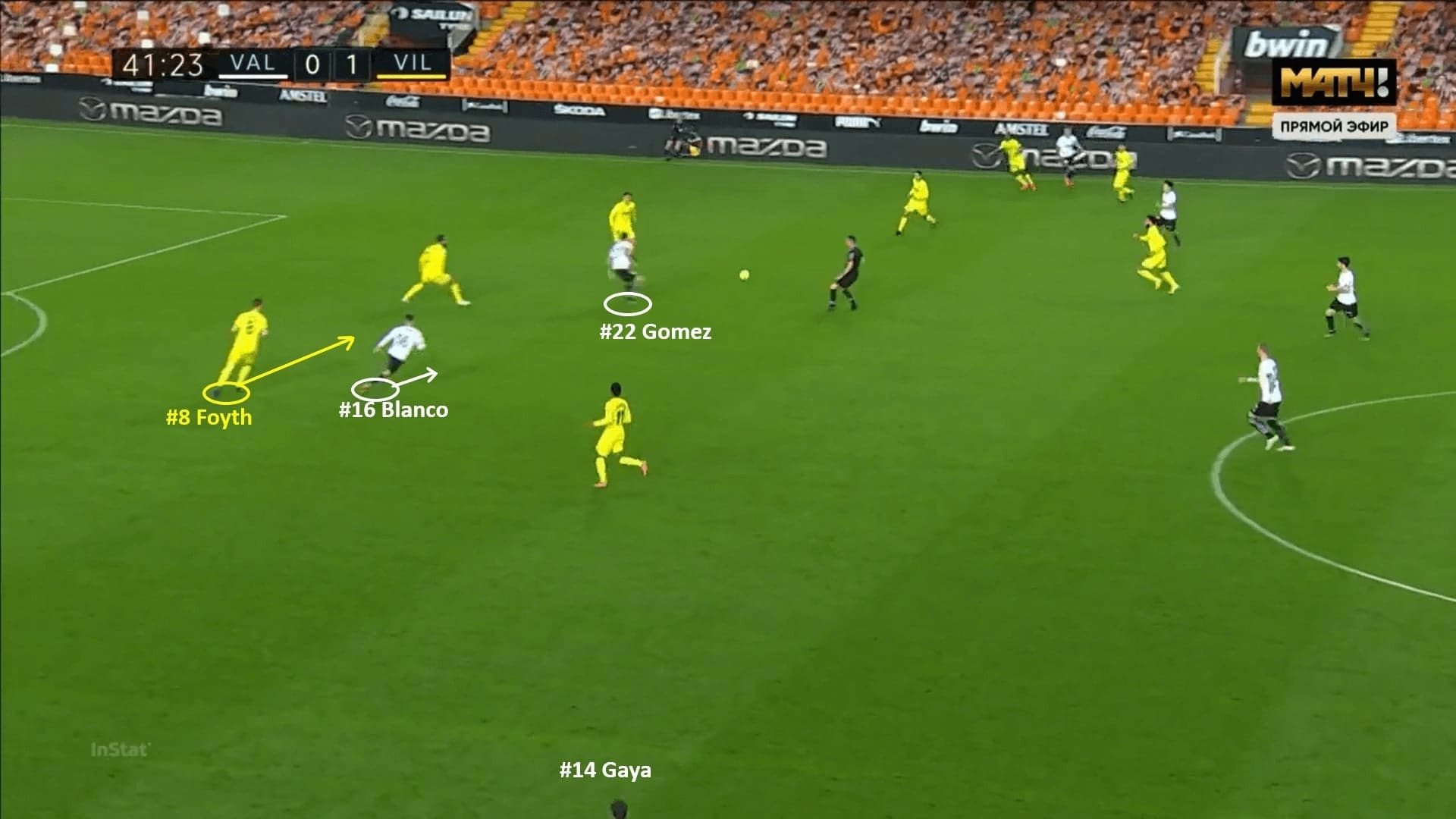

Also, they tried to manipulate the opposition full-back for Gayà or Thierry Corriea. When they made movements from outside to inside, the full-back often followed, leaving wide spaces free.

The above image included these two features of Valencia’s attack. Maxi Gómez was able to receive and turn as the Villarreal centre-backs were not good at defending spaces in front. Meanwhile, Blanco made an inside movement, followed by Juan Foyth. Then, look at the bottom of the picture, Gayà would arrive if the switch pass were made. Then, Valencia were simply in the final third.

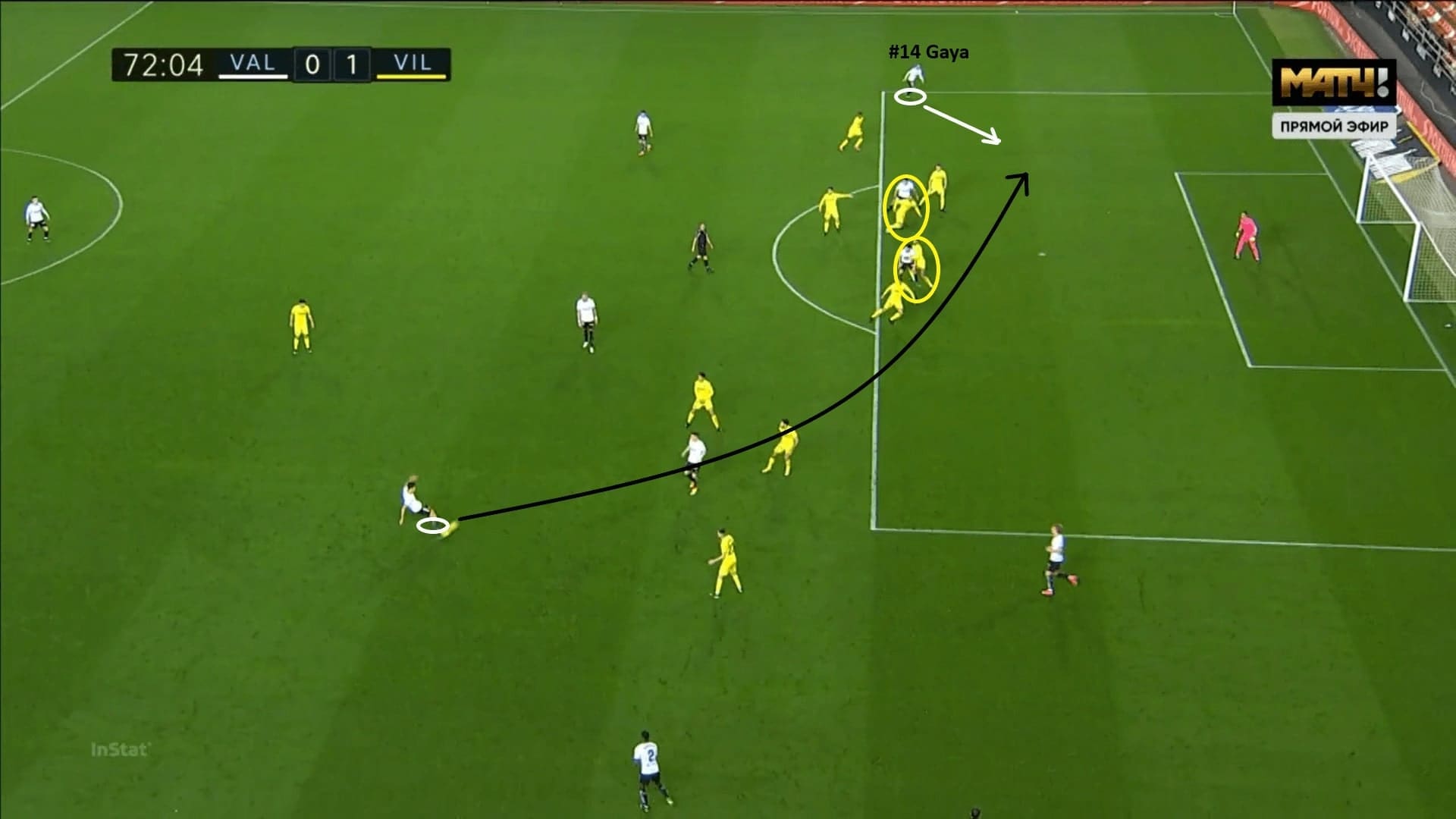

Valencia’s way to attack the penalty box might be a bit similar with Villarreal, but Gayà could be an “X-factor” given his attacking sense in the third phase. Gracia’s troops were not only committing physically strong strikers such as Maxi Gómez to contest with the centre-backs. Furthermore, their dynamism was the run behind the farthest defender – which Gayà was good at it.

The image shows the situation. Crossing early, the two targets of Valencia might not have reached the penalty spot yet, so do the defenders who attached themselves to the strikers. However, even the ball went past the entire backline, Valencia still had Gayà at the end to attack, who run from the blindside of the right-back. This opportunity almost went in.

Final remarks

There are many factors that contributed to the come back of Valencia. From the guests’ perspective, they continued the sluggish offensive performance since 2021. Emery’s team were not able to create a lot of clear-cut chances, but they also failed to kill the game when the chances came. They must need to produce a higher quality football to secure a Europa League position next season.

Valencia tried very hard to come back from behind. Although also using a 4-4-2, their offensive plays emphasized a lot on Gaya. The 25-year-old left-back was a huge impact, dominating the left flank, helped the hosts get into the final third and create.

Comments